A. HANAYAMA ET AL. 663

which I will record here on a prepared form. Since your seat

order was determined by draw before entering the laboratory,

you will give your answer in the seat order, from 1 to 4”.

Then, the experimenter double-checked whether they all

knew their answering order by asking them to reply in that

order. Finally, the experimenter instructed them to pay special

attention to the following three points.

1) Please be accurate as possible. You don’t have to answer

quickly.

2) Please make the judgment all by yourself.

3) Please do not talk or react to the other participants and

stay quiet unless it is your turn to answer.

After all the instructions were given, the experimenter told

participants to put on the sunglasses to protect their eyes from

glare. Then the experimenter presented the line judgment trials

to the participants in the predetermined order. Each trial took

approximately 30 seconds.

In Mori and Arai (2010) the participants completed 18 trials,

the same nine-stimulus set twice, as those in Asch (1956).

However, we presented the nine-stimulus set only once because

the young child participants were expected to have much

shorter attention spans than adult participants. Of the nine-

stimulus set, three trials (1st, 2nd, and 5th) were neutral, with

all viewers seeing the same thing. In the remaining six trials

(3rd, 4th, 6th, 7th, 8th, and 9th), the minority and majority par-

ticipants saw the standard lines in different lengths. After the

line judgment tasks were completed, participants were indi-

vidually interviewed and debriefed.

Results and Discussion

Manipulation Check

The post-experimental interview revealed that no child no-

ticed any anomaly during the tasks, a finding that fits with Mori

and Arai (2010). The children who wore the different type of

sunglasses and responded third made more errors than the other

three participants who wore the same type of sunglasses. This

response pattern clearly showed that a minority of one per-

formed differently from the other three who formed a majority

group. Thus, the fMORI-Asch experimental paradigm success-

fully created majority and minority viewers among naïve child

participants without intro du c i n g confeder a t e s .

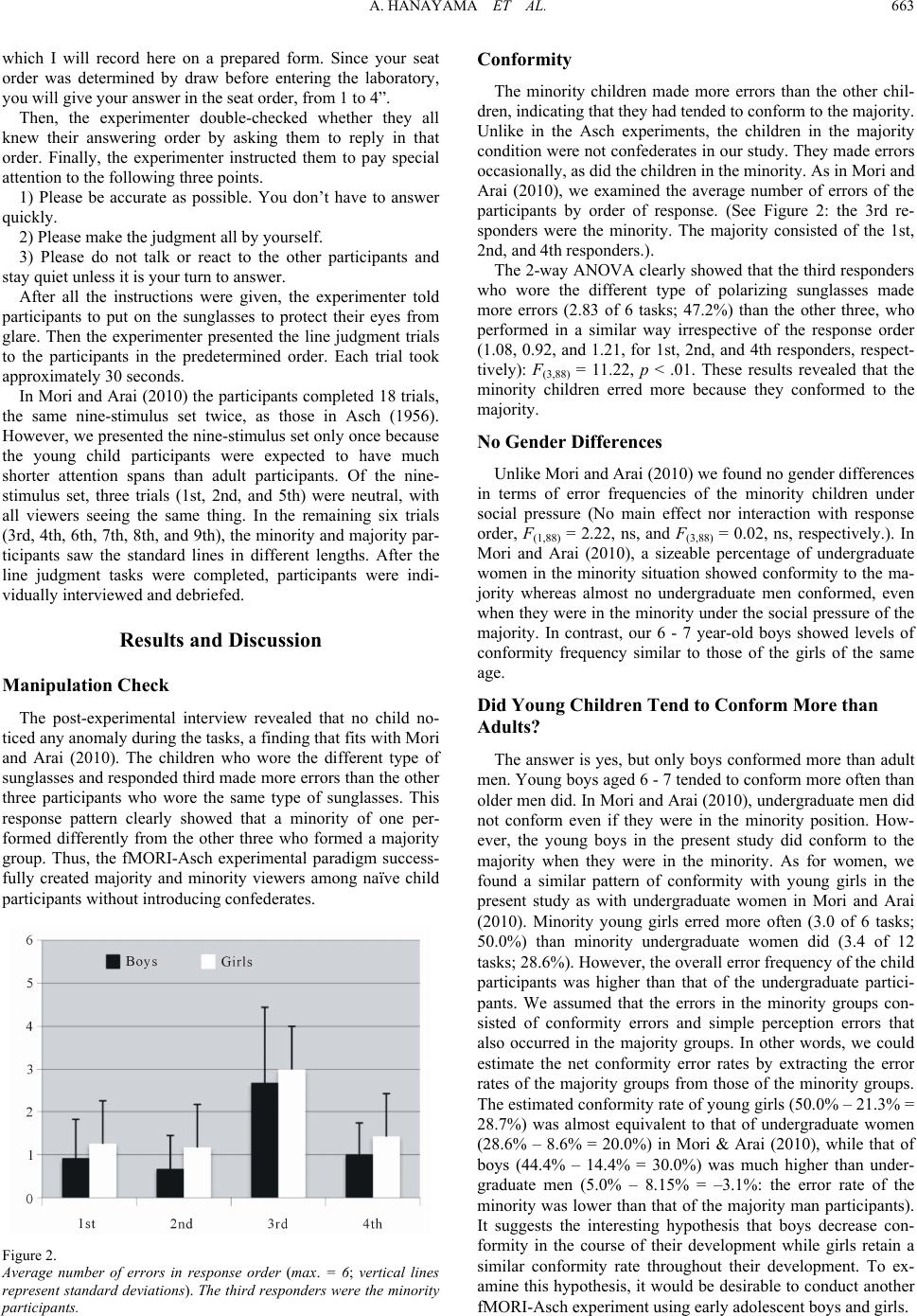

Figure 2.

Average number of errors in response order (max. = 6; vertical lines

represent standard deviations). The third responders were the minority

participants.

Conformity

The minority children made more errors than the other chil-

dren, indicating that they had tended to conform to the majority.

Unlike in the Asch experiments, the children in the majority

condition were not confederates in our study. They made errors

occasionally, as did the children in the minority. As in Mori and

Arai (2010), we examined the average number of errors of the

participants by order of response. (See Figure 2: the 3rd re-

sponders were the minority. The majority consisted of the 1st,

2nd, and 4th responders.).

The 2-way ANOVA clearly showed that the third responders

who wore the different type of polarizing sunglasses made

more errors (2.83 of 6 tasks; 47.2%) than the other three, who

performed in a similar way irrespective of the response order

(1.08, 0.92, and 1.21, for 1st, 2nd, and 4th responders, respect-

tively): F(3,88) = 11.22, p < .01. These results revealed that the

minority children erred more because they conformed to the

majority.

No Gender Differences

Unlike Mori and Arai (2010) we found no gender differences

in terms of error frequencies of the minority children under

social pressure (No main effect nor interaction with response

order, F(1,88) = 2.22, ns, and F(3,88) = 0.02, ns, respectively.). In

Mori and Arai (2010), a sizeable percentage of undergraduate

women in the minority situation showed conformity to the ma-

jority whereas almost no undergraduate men conformed, even

when they were in the minority under the social pressure of the

majority. In contrast, our 6 - 7 year-old boys showed levels of

conformity frequency similar to those of the girls of the same

age.

Did Young Children Tend to Conform More than

Adults?

The answer is yes, but only boys conformed more than adult

men. Young boys aged 6 - 7 tended to conform more often than

older men did. In Mori and Arai (2010), undergraduate men did

not conform even if they were in the minority position. How-

ever, the young boys in the present study did conform to the

majority when they were in the minority. As for women, we

found a similar pattern of conformity with young girls in the

present study as with undergraduate women in Mori and Arai

(2010). Minority young girls erred more often (3.0 of 6 tasks;

50.0%) than minority undergraduate women did (3.4 of 12

tasks; 28.6%). However, the overall error frequency of the child

participants was higher than that of the undergraduate partici-

pants. We assumed that the errors in the minority groups con-

sisted of conformity errors and simple perception errors that

also occurred in the majority groups. In other words, we could

estimate the net conformity error rates by extracting the error

rates of the majority groups from those of the minority groups.

The estimated conformity rate of young girls (50.0% – 21.3% =

28.7%) was almost equivalent to that of undergraduate women

(28.6% – 8.6% = 20.0%) in Mori & Arai (2010), while that of

boys (44.4% – 14.4% = 30.0%) was much higher than under-

graduate men (5.0% – 8.15% = –3.1%: the error rate of the

minority was lower than that of the majority man participants).

It suggests the interesting hypothesis that boys decrease con-

formity in the course of their development while girls retain a

similar conformity rate throughout their development. To ex-

amine this hypothesis, it would be desirable to conduct another

fMORI-Asch experiment using early adoles cent boys and girls.