Psychology 2011. Vol.2, No.7, 737-742 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. DOI:10.4236/psych.2011.27113 Do Deaf Children Delay in Their Executive Functioning Due to Their Delayed Language Abilities? Rafet Firat Sipal, Pinar Bayhan Department of Child Development, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey. Email: fsipal@hacettepe.edu.tr Received July 1st, 2011; revised August 6th, 2011; accepted September 16th, 2011. Language use during daily interactions plays a key role in executive functioning. Given that increasingly sophis- ticated language is required for effective executive functioning as an individual matures, it is likely that children with delayed language skills will have difficulties in performing tasks which are related to executive functioning. The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between language ability and executive functioning in a group of deaf students who communicate using spoken Turkish, as measured by their performance on WSCT (Wisconsin Card Sorting Test). For that purpose, 82 children who are deaf were tested by means of their lan- guage skills and executive functioning abilities. Results show that, language skills have significant impact on the executive functioning of the children. Gender was found to be another factor affecting the executive functions. Results were discussed with the relevant literature. Keywords: Hearing Impairment, Children Who Are Deaf, Executive Functions, Language Development Introduction Spoken language development in severely or profoundly deaf children is generally delayed compared with their hearing peers (Baker-Hawkins & Easterbrooks, 1994). Regarding to their delay in typical development, children who are deaf experience difficulties when communicating with their families, hearing peers, and the wider society (Meadow-Orlans & Erting, 2000; Hindley, 2000). As language is the main component of social communication, it also has key importance for cognitive proc- essing of individuals. The key component of how an individual processes social and cognitive input learning to solve problems and to behave intelligently is through the use of language (Ylvisaker & De Bonis, 2000). Language provides individuals with the capacity to think, learn, and behave through understanding and interact- ing through shared symbols. The process of recognition, coding, storing, and recalling of any social or cognitive information create links necessary for future processing. Language enables the storing and recalling of information that is already known and reasoning about what an individual does or does not know. While using language in that way, individuals are in fact com- municating with themselves about how to solve a problem and to learn (Barkley, 1997). From this point of view, how language skills are developed and used appropriately is a complex proc- ess requiring the correct functioning of many different cogni- tive processes. These processes, or executive functions, enable effortful and flexible organization of information and the in- corporation of strategic and goal-orientated behavior (Borkowski & Muthukrishna, 1992). Simply, such executive functions en- able intelligent thought, problem solving, and learning to take place. The construct of executive function (EF) encompasses the or- ganizational and self-regulatory skills required for goal-directed, non-automatic behavior. It has been variously described as including planning, initiating, monitoring, and flexibly correct- ing actions according to feedback; sustaining and shifting atten- tion; controlling impulses and inhibiting pre-potent but mal- adaptive responses; selecting goals and performing actions that may not lead to an immediate reward, with a view to reaching a longer term objective; holding information in mind whilst per- forming a task (working memory); and creatively reacting to novel situations with non-habitual responses (Hughes & Gra- ham, 2002; Shallice & Burgess, 1991; Welsh & Pennington, 1988). Recent theoretical conceptualizations of EF suggest that it is not a unitary function, but encompasses a range of dissoci- able skills, such that it is possible for an individual to fail on some executive tasks whilst succeeding on others (Baddeley, 1998; Garavan, Ross, Murphy, Roche, & Stein, 2002; Miyake et al., 2000). Different EF skills may follow independent de- velopmental pathways, some of which may be more strongly associated with language (and thus more affected by the con- sequences of deafness) than others. Language deficits in deaf children, which typically reflect delayed rather than disordered functioning, are potentially use- ful in clarifying the relationship between language and EF be- cause these children’s difficulties are secondary to a peripheral cause. Electroencephalogram evidence (Wolff, Kammerer, Gradner, & Thatcher, 1989; Wolff & Thatcher, 1990) has shown differences in the neural organization of the bilateral frontal cortex (closely linked to EF abilities) and the left tem- porofrontal area (involved in expressive language) of deaf and hearing children. A weaker development of these cortical areas might be reflected in both poorer language and poorer EF in deaf children. No studies have examined EF comprehensively in deaf children, although a number have included tests that assess some EF components as part of wider investigations. There is some evidence for impaired attention in deaf children compared to their hearing peers (Khan, Edwards, & Langdon, 2005; Mitchell & Quittner, 1996). Planning and problem solv- ing have also been found to be poorer in deaf children when compared with hearing children (Das & Ojile, 1995; Marschark & Everhart, 1999). Further, there are numerous studies report- ing on the intelligence and problem-solving abilities of deaf children, but there are relatively few that are specific to higher level cognitive processing and particularly to EF. In fact, since  R. F. SIPAL ET AL. 738 1994, only three studies have reported specifically on the EF abilities of school-aged deaf children (Luckner & McNeill, 1994; Marschark & Everhart, 1999; Surowiecki et al., 2002). Two of these studies have assessed EF using different versions of Tower tests (Luckner & McNeill, 1994; Surowiecki et al., 2002), whereas one has used 20 Questions (Marschark & Everhart, 1999). The development of language and that of EF is considered to closely linked. Given the wealth of research examining the impact of deafness on the language acquisition of deaf children, it is surprising that limited research has been carried out deaf children’s EF, and that there are such few studies explicitly examining the relationship between language skills and EF in deaf children. Many of the existing studies have examined deaf children’s performance on only a few of the EF subcomponents. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the relation- ship between language ability and executive functioning in a group of deaf students who communicated using spoken Turk- ish, as measured by their performance on a standardized test of executive function: WCST. It was hypothesized that, language ability would relate to performance on the measures of execu- tive functioning. For that purpose, we tested 82 children who are deaf in order to assess their EF and language abilities. We did not include a comparison sample in our study because it is already well documented in literature that normally developing children have better executive functioning than their hearing impaired counterparts. Thus, we compared hearing impaired children according to their language abilities and we grouped children into two groups as; with and without preschool special education experience. The rationale for this grouping is the well documented positive effect of early special education on the language skills of children who are deaf. As it is previously reported children with language impairments present lower EF compared to children with typical language development, comparing children who are deaf with different language abili- ties will provide precious/vital/ novel information on the rela- tionship between language skills and EF of children who are deaf. Method Participants The present study was conducted in the metropolitan area of Ankara, the capital city of Turkey. All segregated schools for the deaf in Ankara were contacted for participation. The pur- pose of the study was explained and discussed with the Princi- pals of these schools. However, one of the schools refused to participate in the study due to the busy schedule. In total 82 children between 10 - 14 ages were recruited into the study. Of these participants 42 children were boys and 40 were girls with a mean age of 11.91 (s = 1.44) All the children had bilateral, sensory-neural (S/N), severe hearing loss (71 - 95 dB) as they were all attending classes in segregated schools for the deaf. 39 of the children (47.6%) had early special education history whereas 43 of them (52.4%) not. Children with a secondary disability were excluded from this study. Instruments Demographic information form: A demographic information form was used to gather information about the family, child, child’s education and child’s communicative behaviors. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT): PPVT as devel- oped by Dunn in 1959 (as cited in American Guidance Services, AGS, 2005) was utilized to assess the vocabulary knowledge of children as well as their receptive language. The PPVT is an individual language performance test, orally administered in less than 20 minutes. No reading is required by the subject, and scoring is rapid and objective. Item responses are made by pointing or multiple choice selections, dependent upon the sub- ject’s age. Although desirable, no special training is required to properly administer and score the PPVT. The PPVT provides an estimate of the subject’s verbal performance and can be ad- ministered to groups with reading or speech problems, mental retardation, or if emotionally withdrawn. For its administra- tion, the examiner presents a series of pictures to each subject. There are four pictures to a page, and each is numbered. The examiner states a word describing one of the pictures and asks the client to point to or say the number of the picture that the word describes. PPVT was standardized for Turkish language by Katz and colleagues in 1974 (as cited in Oner, 1997). For Turkish standardization, 1440 children (2 - 12 years) living in urban, suburban and rural areas were tested and norm tables were listed according to the scores. Reliability of Turkish stan- dardization of PPVT was found to have range of .71 - .81. Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST): WCST is developed by Berg (1948), and revised by Heaton (1981) to assess execu- tive functions in terms of planning, organizing, abstract think- ing, conceptualization, maintaining and adapting cognitive constructs and inhibiting impulsive responses (Lezak, 1995; Spreen & Strauss, 1998). WCST measures 13 different execu- tive functioning abilities; number of total responses, number of total errors, number of total correct responses, number of cate- gories completed, number of perseverative responses, number of total perseverative errors, number of nonperseverative errors, percentage of perseverative errors, number of responses to complete the set, number of conceptual level of responses, per- centage of conceptual level of responses, failure to maintain a set and learning to learn. Turkish standardization and validation of WCST for adults was reported by Karakas, Eski and Basar (1996) and for children between 6 - 15 ages (75 - 182 months) by Erol et al. (2006). Procedure: The procedure was applied at the schools during day time under the supervision of the teachers. Children were informed about the purpose of the study and the voluntary nature of par- ticipation was explained. None of the children refused to par- ticipate in the study. School records were used for grouping children with and without special education background. Chil- dren with early special education background formed Group 1 and children without early special education background formed Group 2. Even though Group 1 was expected to have better language performance, both groups were tested with PPVT by authors in order to assess their language performance before the study procedure was applied. Thus, the data gathered from Group 1 also points the group with “better language perform- ance”. EF of the children were tested with WCST in the test rooms of the schools where are silent rooms with minimum materials which minimize the distraction of children. Children were given stickers of stars and smiley faces to reward their efforts and sustain motivation. The same numbers of stickers were offered to each child, across the two groups. Care was taken to give instructions with maximum clarity, making sure that children could see the tester’s lip movements, and that their attention was appropriately focused. The same instructions  R. F. SIPAL ET AL. 739 were given to all participants. Tests were always administered in the same order, to ensure that potential test-order effects would be constant across groups. Test materials were four stimulus cards (from left to right; a red triangle, two green stars, three yellow crosses and four blue circles) and the response cards. Response cards were placed in an order as described in the test manual. The researcher picked one of the response cards and gave it to the child in order to match the correct stimulus card. For each correct match, the child was prompted as “correct” and for each false match the child was prompted as “false”. First turn of matching was based on color, second turn was based on shape and third turn was based on quantity. As soon as the child successfully completed the first turn (match- ing 10 cards according to their colors), matching criterion was changed to “shape”. Similar to the first turn, for each correct match the child was prompted as “correct” and for each false match the child was prompted as “false”. Each session included six turns as; color, shape, quantity, color, shape, quantity. WCST sessions ended when the children successfully matched the cards (10 for every category) in six matching categories (color, shape, quantity, color, shape, quantity) or when the cards ran out. Sessions took around 20 - 25 minutes for the chil- dren participating in the study. Preliminary analyses of the participants are shown in Table 1. Table 2 provides the descriptive statistics for each group of Table 1. Preliminary analysis of the participants in the study. Variable N % S M Age 10 19 % 23.2 11 16 % 19.5 12 15 % 18.3 13 17 % 20.7 14 15 % 18.3 1.44 11.91 Gender Girl 40 % 48.8 Boy 42 % 51.2 Early special e ducation background Had early special ed. 39 % 47.6 Did not have early special ed. 43 % 52.4 Duration of early special education Never 43 % 52.4 Less than 1 year 10 % 12.2 1-2 years 5 % 6.2 2-3 years 2 % 2.4 More than 3 years 22 % 26.8 Communication choices with family Sign language 16 % 19.5 Oral language 16 % 19.5 Both 50 % 50 Reactions to communication barriers Repeatedly tries to express 63 % 76.8 Gets angry 10 % 12.2 Gives up 6 % 7.3 Other 3 % 3.7 Table 2. Children’s performance on peabody picture vocabulary test. PPVT raw scores PPVT standard scores Group n M SD M SD Group 1a 39 56.3 14.4 67.2 11.7 Group 2b 43 50.1 12.7 48.4 14.3 Note. Standard scores based on a population M = 100, SD = 13. a. with early special education background; b. without early special education background. children on the language test. As hypothesized, a significant effect of group emerged on children’s raw score on the PPVT (F[2, 65] = 29.89, p < .001) Follow-up ANOVA with Bon- ferroni corrections revealed that, as expected, Group 1 scored significantly higher than Group 2 (F[1, 41] = 50.93, p < .001) Correlations of WCST scores with language ability, gender and age are presented in Table 3. Pre-analyses of data distribu- tion showed that some of the WCST scores presented abnormal distribution. Therefore, WCST scores which showed abnormal distribution were analyzed with Mann-Whitney U and Wil- coxon W tests and normally distributing scores were analyzed with T test. Results showed that WCST scores 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 11, 13 are significantly effected by language ability (p < .05). Gender was found to have impact on all WCST scores but WCST 7 and 10. Besides, age showed difference for only WCST 7 (p = .005). Tukey’s post-hoc was applied for better understanding the difference between ages. Results showed that ages 10 and 14 differ for WCST 7 (mean scores difference = 7, 80, S = 2.84, p = .05). Distribution of the mean scores gathered from WCST was shown in Figure 1 for better understanding the WCST per- formances of children in the study. There is a decreasing trend in the mean scores which show that children in the study were facing difficulties in most of the main WCST tasks such as number of categories completed (WCST 4), number of nonper- severative errors (WCST 7), number of responses to complete the first set (WCST 9), learning to learn (WCST 13) and main- taining a set (WCST 12). Conceptual level of responses in both numbers and percentages were found relatively average (WCST 10 and 11). Discussion High level cognitive processing abilities, also known as key executive functions, include planning and organizational abili- Figure 1. istribution of mean scores for each WCST subtest. D  R. F. SIPAL ET AL. 740 Table 3. Analysis of language a b ility, age and gender compared t o WCST scores. Language abil ity Gender Age WCST Mann Whitney U Wilcoxon W F t p Mann Whitney UWilcoxon WF t p X2 F p WCST 1 566.0 1386.0 .002* 2.43 .657 WCST 2 23.52 –6.01 .003*486.5 1306.5 .001* 1.417.236 WCST 3 58.90 3.46 .001* 11.152.52 .014* 1.130.348 WCST 4 .005 946.0 .007* .12 4.15 .023* .244 .913 WCST 5 42.68 6.48 .009*469.0 1289.0 .001* 3.55 .469 WCST 6 42.63 –6.48 .001*460.0 1280.0 .004* 4.09 .393 WCST 7 4.69 .335 .738 2.73 –.77 .441 4.018.005* WCST 8 46.88 –6.06 .013*549.5 1369.5 .007* 4.72 .396 WCST 9 1.12 –1.23 .221 .67 –2.49 .015* 1.126.351 WCST 10 678.5 1458.5 .965 664.0 1259.0 .862 2.107.089 WCST 11 379.0 1009.0 .001*462.5 1057.5 .018* 2.399.058 WCST 12 513.5 1293.5 .853 299.5 734.5 .001* 4.97 .290 WCST 13 2.56 13.97 .037* .59 2.37 .021* 1.207.318 Note: *p < .05 significance level. ties. abstract thinking, formulation of effective strategies, estab- lishment and maintenance of cognitive sets, and refraining from impulsive trial-and error responses. Such executive functioning requires the ability to draw upon existing knowledge and strategies which are then applied to problem solving involving the flow of information back and forth between cognitive and metacognitive levels of processing (Butterfield et al., 1995). Some researchers have suggested that the observed EF Table 3. deficits of children with language delay or impairment imply that language ability may play a significant role in executive functioning (Singer & Bashir, 1999; Ylvisaker & De Bonis, 2000). The main hypothesis of this study was that language ability would relate to performance on measures of executive functioning differentially. The findings, in general, provide support for this hypothesis. Results of language ability were found to impact on execu- tive functions. The findings illustrate that WCST 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 11 and 13 were significantly affected by language ability and the group (1) with higher language skills was found to possess higher levels of executive functioning. This finding links/cor- relates with previous studies on executive functions and lan- guage problems (Marlowe, 2000; Singer & Bashir, 1999; Landa & Goldberg, 2005; Hooper et al., 2002). Hooper et al. (2002) studied language skills and reported that impairments in lan- guage results in impairments in executive functions. The paral- lel finding in our study echoes the early studies and reveals that children who are deaf have delays in executive functions and better language abilities have a boosting effect in developing executive functions. Besides, results show that WCST 7, 9, 10 and 12 had no significant affect on language abilities in our sample. This finding is quite surprising as WCST 9 and 12 points out working memory which is highly related to language skills. Such a result indicates that there may be some other fac- tors affecting working memory than the language. Surprisingly, the findings on WCST and gender presented were at odds to those already cited in the literature (Surowiecki et al., 2002; Miyake et al., 2000; Erol et al., 2006). All WCST scores with the exception of WCST 7 and 10 were found to be significantly affected by gender. Heaton (1993), Roselli and Ardilla (1993) and Shu, Tien, Lung et al. (2000) reported that gender has no significant affect on executive functioning. Moreover, Erol et al. (2006), in the standardization of WCST for Turkish children reported that gender has no effect on any WCST scores. In our study, boys were found to have higher executive skills compared to girls which show that girls have poor perseveration skills. Such a finding may be an artifact of the sampling process. In our study, we assessed a highly spe- cific sample which may lead to biased findings because of the characteristics of the participants. However, this result is strongly considered by the authors as necessary to be assessed in further studies. Frontal lobes are well-known to be the latest developing body structures both anatomically and in functionality and therefore, their activities increase with age and reach their Ze- nith during adolescence (Karakas, 2004; Kilic, 2002). Thus, adolescents are expected to have higher levels of executive functioning and positive WCST scores relative to school age children/pre adolescents. In this study, only WCST 7 (number of nonperseverative errors) was found to be affected by age which shows that nonperseverative errors of children who are deaf decrease with age and which is in keeping with previously published studies (Heaton, 1993; Roselli & Ardilla, 1993; Erol et al., 2006). This finding highlights the importance of devel- opmental features. During normal development children ach- ieve their highest level of executive functioning around 11 age, children who are deaf display delays in the development of this executive functioning and only possess the EF of a 10 years old child when they are between 12 - 14 ages. Such a difference  R. F. SIPAL ET AL. 741 highlights the importance of language skills on the develop- ment of EF. As children learn to control their behaviors and flexibly correct their actions with social feedbacks (Hughes & Graham, 2002), thus the lack of receiving insufficient feedback due to low language skills affects their ability to learn to control their responses. As a result one can say that “lack of practicing” self regulatory skills lead to delays in the development of EF. Conclusion Findings of our study presents that language ability has im- pact on executive functions of children who are deaf. From a theoretical perspective, the findings support the interdepend- ence of language and executive functions but also suggest that executive functions themselves may be dissociable. Therefore, one can say that early language skills have positive effects on cognitive development of children who are deaf. Besides, it is argued that the behavioral manifestations of executive function delays observable in deaf children are un- likely to be the consequences of deafness itself but rather result from the language delays that are the consequences of the deafness. The finding that deaf children experience deficits in executive functions has both clinical and educational implica- tions. Clinical assessment of deaf children should take into account their potential difficulties with executive functions and the ways in which this might interfere with their performance in other areas, including both the cognitive and social domains. Deficits in executive functions may manifest in difficulties in organizing thoughts for writing tasks, organizing materials for lessons or homework, organizing time, and implementing lengthy verbal instructions. Poor executive functioning may also show behaviorally through difficulties in social situations, such as expressing the self and peer interactions. Behavioral management and classroom teaching may be facilitated by us- ing learning strategies that emphasize visual cues and place minimal demands on language, so that deaf children’s execu- tive functioning can be maximized. In addition, enhancing par- ticular aspects of language use, such as teaching deaf children to practice and implement self talk strategies for planning and problem solving, may help them make better use of their exist- ing executive functioning and develop them more fully. Limitations and Implications for Further Studies This study was an attempt to assess the executive functions of children who are deaf and to clarify the linking to their lan- guage abilities. As some of the findings echo the earlier re- search, present study poses several questions which will require further research and evaluation. The limited number of participants in the study has the risk of presenting biased results as well as decreasing weighting of the findings. Of the small sample size (82 children) means that the findings may reflect the characteristics of the participants, their cultural background or the structure of their social envi- ronment. A further study with a larger sample may present more accurate results. Children with disabilities differ within their groups as they may have different levels of severity in their disability. Particu- larly for children who are deaf, there are numerous educational options according to their hearing and language abilities that support their development. As different educational back- grounds may cause differences in their developmental pace, including a particular group (only with severe hearing loss or only profound hearing loss) in a study may result in limited findings which are not comparable. Therefore, a future study including children who are deaf from different levels of hearing loss would provide deeper understanding of their executive functioning. Our study provides information on the development of ex- ecutive functioning of children who are deaf. However, our findings are limited to a small range of age group. A further study including a wide range of age group (i.e. 6 - 12 ages) may provide clearer results on the development of the executive functions of children who are deaf. Besides, a comparison group would provide precious information on their develop- mental pathways in terms of executive functioning. References American Guidance Services Publishing (2005). Peabody picture vo- cabulary test (3rd ed.). URL (last checked 11 September 2008) http://www.agsnet.com/group.asp?nGroupInfoID=a12010 Baddeley, A. (1998). The central executive: A concept and some mis- conceptions. Journal o f the International Neuropsychological Society, 4, 523-526. doi:10.1017/S135561779800513X Baker-Hawkins, S. & Easterbrooks, S. (1994). Deaf and hard of hear- ing students: Educational service delivery guidelines. Alexandria, VA: National Association of State Directors of Special Education. Barkley, R. A. (1997). Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: Constructing a unifying theory of ADHD. Psy- chological Bulletin, 1 2 1 , 65-94. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.65 Berg, E. A. (1948). A simple objective technique for measuring flexi- bility in thinking. Journ al o f G en er a l Psychology, 39, 15-22. doi:10.1080/00221309.1948.9918159 Borkowski, J. G., & Muthukrishna, N. (1992). Moving metacognition into the classroom: Working models and effective strategy teaching. In M. Pressley, K. R. Harris, & J. T. Guthrie (Eds.), Promoting aca- demic competency and literacy in schools (pp. 477-501). San Diego, CA: Academic Press, Inc. Das, J. P., & Ojile, E. (1995). Cognitive processing of students with and without hearing loss. Journal of Special Education, 29, 323-336. doi:10.1177/002246699502900305 Erol, N., Akcakın, M., Akozel-Sahin, A., Dikmeer-Altınoglu, I. & Irak, M. (2006). Standardization of neuropsychological tests used for as- sessing executive functions for Turkish school age children. Proje no: 20040809183. Ankara: Ankara Üniversitesi Bilimsel Araştırma Pro- jeleri. Garavan, H., Ross, T. J., Murphy, K., Roche, R. A. P., & Stein, E. A. (2002). Dissociable executive functions in the dynamic control of behavior: Inhibition, error detection and correction. Neuroimage, 17, 1820-1829. doi:10.1006/nimg.2002.1326 Heaton, R. K. (1981). Wisconsin card sorting test manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. Heaton, R. K. (1993). Wisconsin card sorting test computer version 2.0. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. Hooper, S. R., Swartz, C. W., Wakely, M. B., DeKruif, R. E. L., & Montgomery, J. W. (2002). Executive functions in elementary school children with and without problems in written expression. Journal of Learning Disabilities , 35, 57-68. doi:10.1177/002221940203500105 Hughes, C., & Graham, A. (2002). Measuring executive functions in childhood: Problems and solutions? Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 7, 131-142. doi:10.1111/1475-3588.00024 Karakas, S. (2004). Handbook of bilnot battery: Research and devel- opment studies of neuropsychological tests. Ankara: Dizayn Ofset. Karakas, S., Eski, R., & Basar, E. (1996). Bilnot battery: The group of neuropsychological tests which were standardized for Turkish culture. 32. Ufuk Matbaasi: Ulusal Nöroloji Kongresi Kitabi. Khan, S., Edwards, L., & Langdon, D. (2005). The cognition and be- havior of children with cochlear implants, children with hearing aids and their hearing peers: A comparison. Audiology and Neuro-Otol- ogy, 10, 117-126. doi:10.1159/000083367 Kilic, B. G. (2002). Theoretical models for executive functions and attention processes and neuroanatomy. Turkish Journal of Clinical  R. F. SIPAL ET AL. 742 Psychiatry, 5, 105-110. Landa, R. J., & Goldberg, M. C. (2005). Language, social and execu- tive functions in high functioning autism: A continuum of perform- ance. Journal of Autism and Developmental D isorders, 35, 557-573. doi:10.1007/s10803-005-0001-1 Lezak, M. D. (1995). Neuropsychological assessment (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. Luckner, J. L., & McNeill, J. H. (1994). Performance of a group of deaf and hard-of-hearing students and a comparison of hearing students on a series of problem solving tasks. American Annals of the Deaf, 139, 371-377. Marschark, M., & Everhart, V. S. (1999). Problem solving by hearing impaired and hearing children: Twenty questions. Hearing Impair- ment and Education International, 1, 63-79. Marlowe, W. B. (2000). An intervention for children with disorders of executive functions. Developmental Neuropsychology, 18, 445-454. doi:10.1207/S1532694209Marlowe Meadow-Orlans, K., & Erting, C. (2000). Mental health and deafness. London: Whurr Publishers. Mitchell, T. V., & Quittner, A. L. (1996). Multi method study of atten- tion and behavior problems in hearing impaired children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 25, 83-96. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp2501_10 Miyake, A., Friedman, N. P., Emerson, M. J., Witzki, A. H., Howerter, A., & Wager, T. D. (2000). The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contribution to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cognitive Psycholog y, 41, 49-100. doi:10.1006/cogp.1999.0734 Oner, N. (1997). Psychological tests used in Turkey: A source for re- searchers. Istanbul: Bogazici Üniversitesi Matbaası. Roselli, M., & Ardilla, A. (1993). Developmental norms for the Wis- consin Card Sorting Test in 5- to 12-year old children. Clinical Neu- ropsychology, 7, 145-154. doi:10.1080/13854049308401516 Shallice, T., & Burgess, P. W. (1991). Higher cognitive impairments and frontal lobe lesions in man. In H. S. Levin, H. M. Eisenberg, & A. Benton (Eds.), Frontal lobe function and dysfunction (pp. 125-138). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Shu, B.C., Tien, A.Y., Lung, F. W. et al. (2000). Norms for the Wis- consin Card Sorting Test in 6 - 11 year old children in Taiwan. Clini- cal Neuropsychology, 14, 275-286 Singer, B. D., & Bashir, A. S. (1999). What are executive functions and self-regulation and what do they have to do with language disorders? Language, Speech, and He a r ing Services in School s , 30, 265. Spielberger, C. D., Reheiser, E. C., & Sydeman, S. J. (1995). Measur- ing the experience, expression, and control of anger. In H. Kassinove (Ed.), Anger disorders: Definitions, diagnosis, and treatment (pp. 49-67). Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis. Spreen, O., & Strauss, E. (1998). A compendium of neuropsychological tests: Administration, norms and commentary (2nd ed.), New York: Oxford University Press. Surowiecki, V. N., Sarant, J., Maruff, P., Blamey, P. J., Busby, P. A., & Clark, G. M. (2002). Cognitive processing in children using cochlear implants: The relationship between visual memory, attention and ex- ecutive functions and developing language skills. The Annals of Otology, Rhinology and Laryngology, 111, 119-126. Taylor, S. E., Pham, L. B., Rivkin, I. D., & Armor, D. A. (1998). Har- nessing the imagination: Mental simulation, self regulation and cop- ing. American Psychologist, 53, 429-439. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.53.4.429 Taylor, S. E., Peplau, L. A., & Sears, O. D. (2000). Social psychology (10th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall Inc. Welsh, M. C., & Pennington, B. F. (1988). Assessing frontal lobe func- tioning in children: Views from developmental psychology. Devel- opmental Neuropsychology, 4, 199-230. doi:10.1080/87565648809540405 Wolff, A. B., Kammerer, B. L., Gradner, J. K., & Thatcher, R. W. (1989). Brain-behavior relationships in hearing impaired children: The Gallaudet Neurobehavioural Project. Journal of the American Hearing Impairment and Rehabilitat ion Association, 23, 19-33. Wolff, A. B., & Thatcher, R. W. (1990). Cortical reorganization in hearing impaired children. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 12, 209-221. doi:10.1080/01688639008400968 Ylvisaker, M., & De Bonis, D. (2000). Executive function impairment in adolescence: TBI and ADHD. Topics in Language Disorders, 20, 29-57. doi:10.1097/00011363-200020020-00005

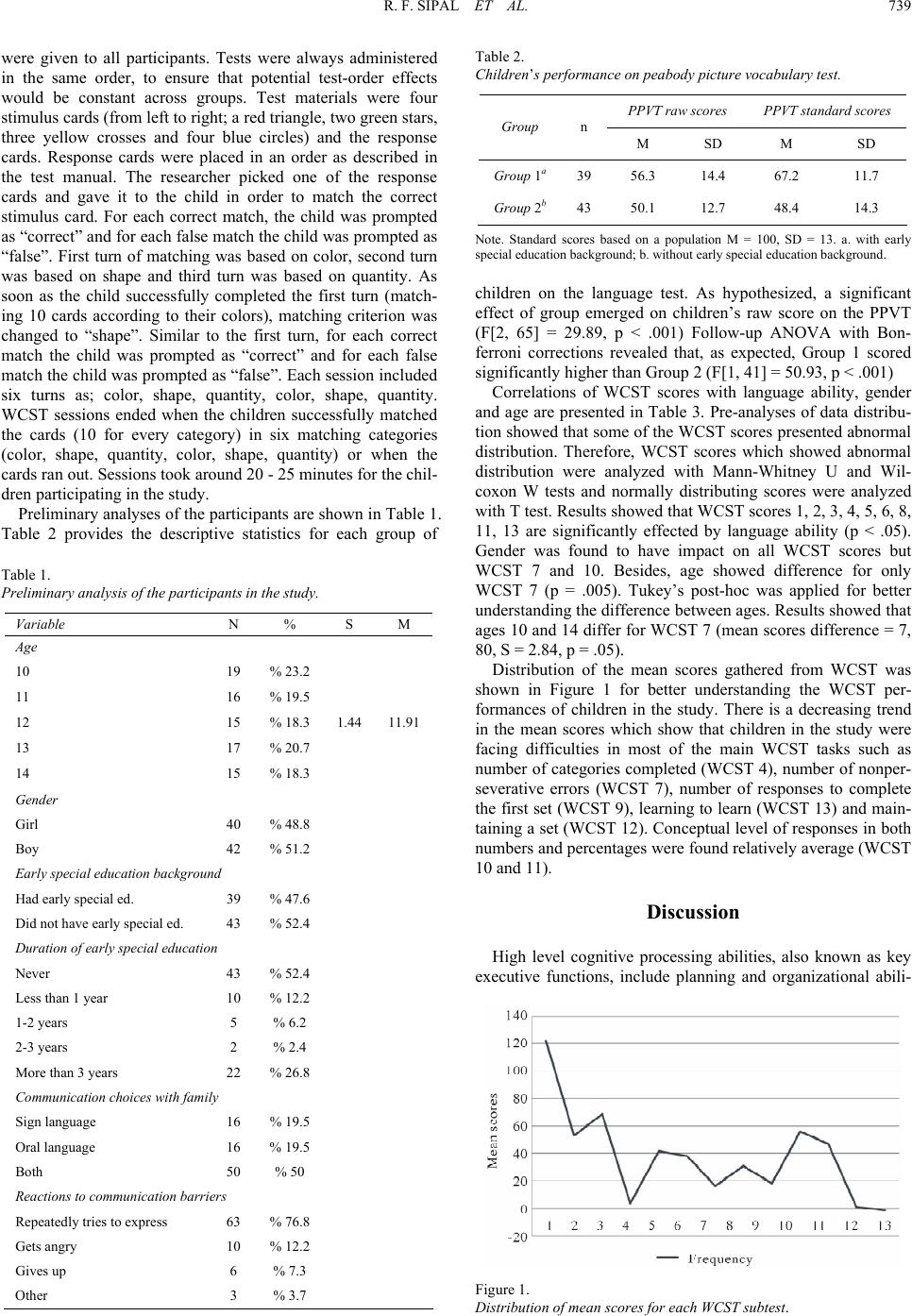

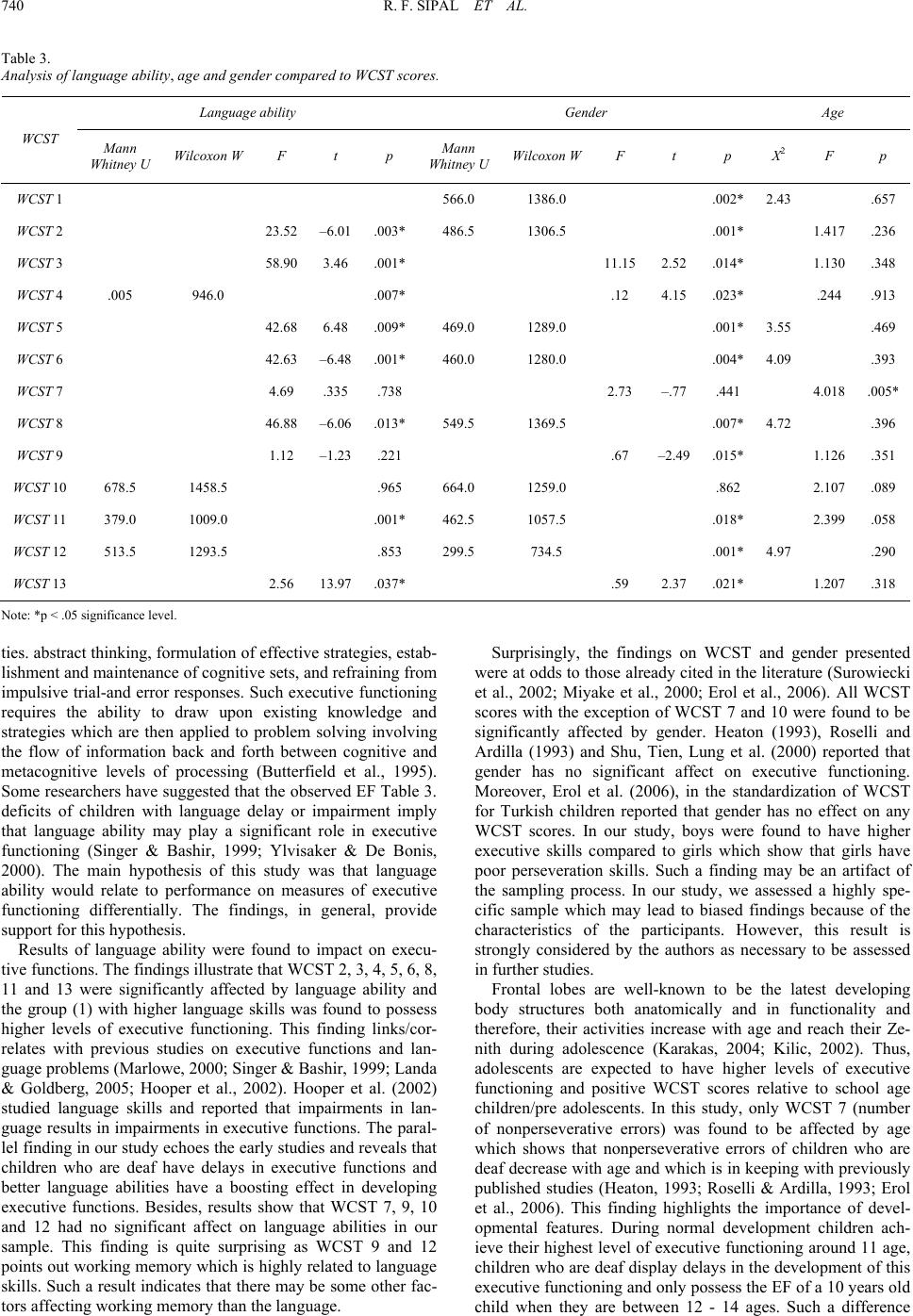

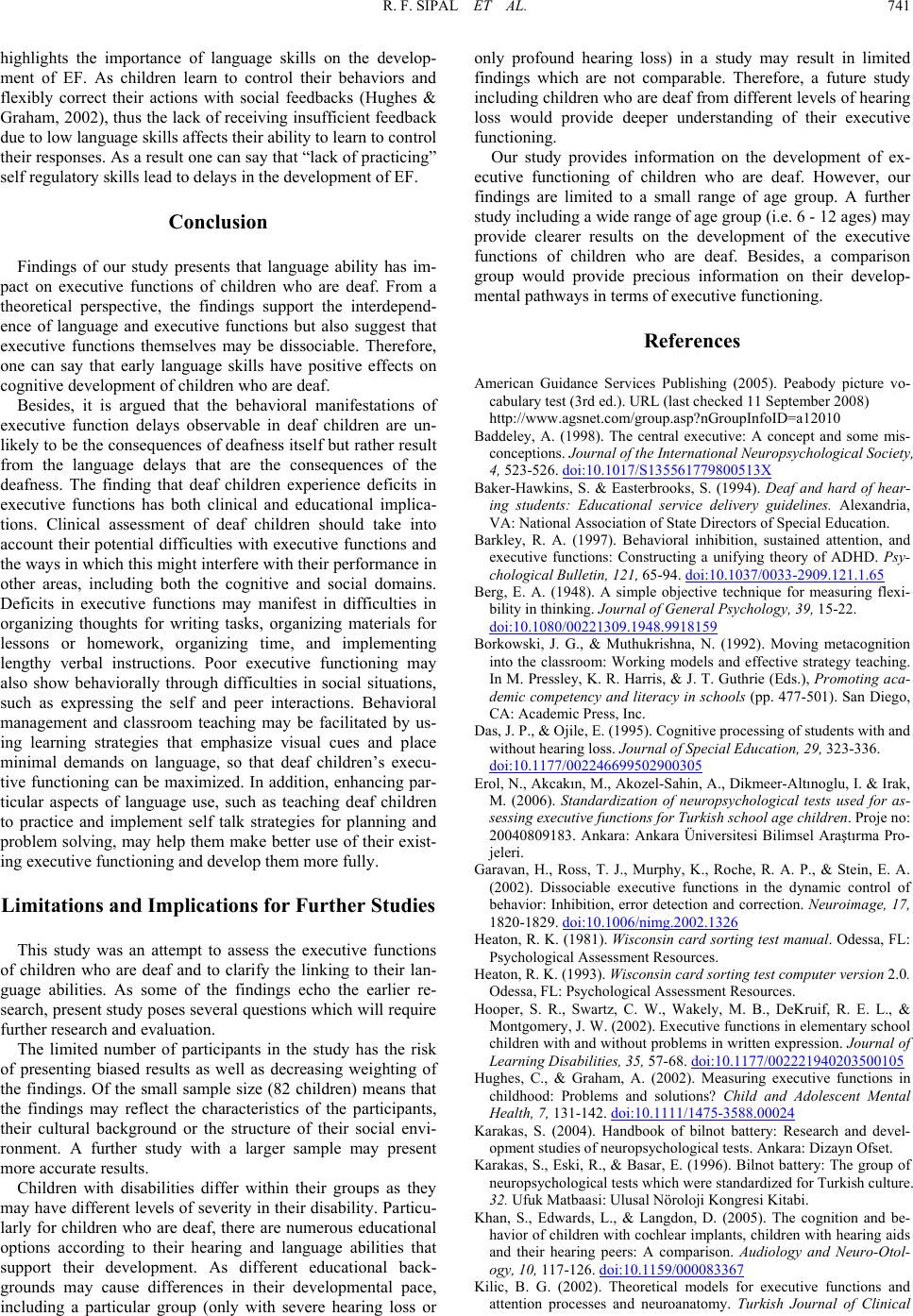

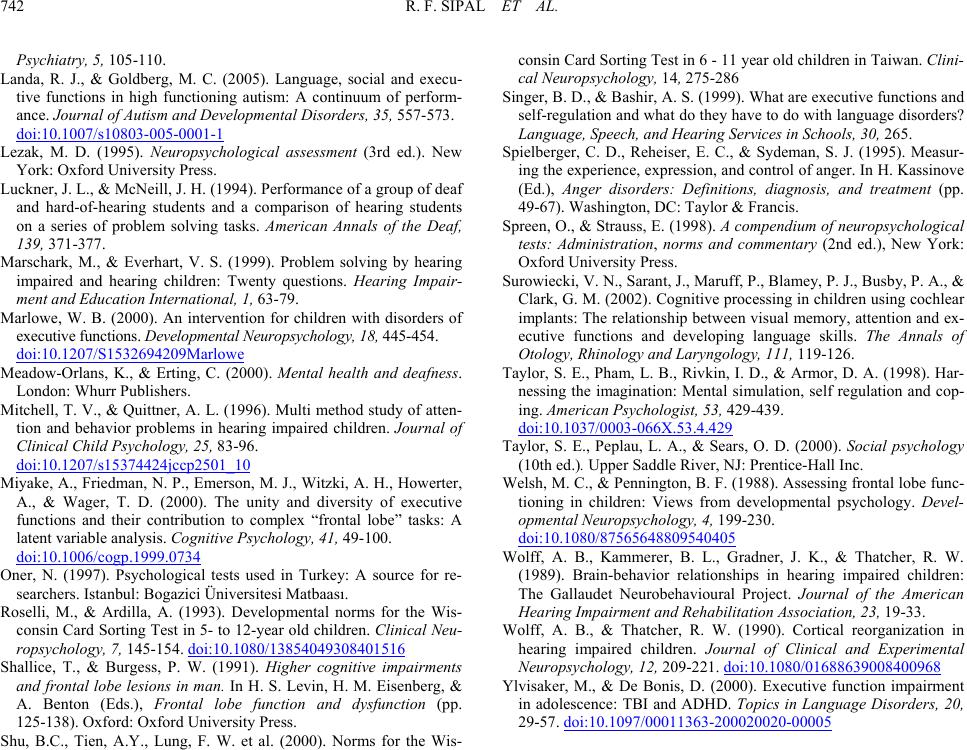

|