Open Journal of Nursing, 2011, 1, 15-25 doi:10.4236/ojn.2011.12003 Published Online September 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ojn/ OJN ). Published Online September 2011 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJN Men with prostate cancer and the accessibility to information —a literature review Charlotte Dorisdatter Bjørnes1,2,3, Christian Nøhr2, Charlotte Delmar1, Birgitte Schantz Laursen1 1Department of Development and Planning, Aalborg University, Aalborg, DK; 2Clinical Nursing Research Unit, Aalborg Hospital, Aarhus University Hospital, DK; 3Department of Urology, Aalborg Hospital, Aarhus University Hospital, DK. Email: bjoernes@plan.aau.dk Received 4 July 2011; revised 19 August 2011; accepted 4 September 2011. ABSTRACT Objective: To explore possible consequences of short stays in hospitals, as these short contacts reduce the patients’ time for information and support. Method: A literature survey was carried out to get an insight in possible consequences by summarizing the state of knowledge on how men with prostate cancer under- going prostatectomy surgery experience their con- tacts with the healthcare professionals. Results: A consequence is that often men with prostate cancer, treated with prostatectomy surgery, do not receive the individualized support, information, and dialogue they need, which leads to feelings of uncertainty, in- security, and loss of control. The men use the Internet in their search for information and support, which makes them able to stay in control and be active, re- sponsible partners in their own course of treatment. Conclusion: For men to feel secure and certain the accessibility of the healthcare professionals and the healthcare professionals’ ability to individualize in- formation and support are important aspects. Prac- tice Implications: It is relevant to provide male can- cer patients with tools that can underpin their con- tact to the healthcare professionals. Utilizing Web 2.0 technologies, Internet based tools can support ex- change-ability, towards dialogue-based contacts, be- tween men with prostate cancer and healthcare pro- fessionals. Keywords: Health Communication; Access to Informa- tion; Short Stay Patients; Prostate cancer; Prostatectomy; Uncertainty; Active Patients; Health informatics; Online Social Support 1. INTRODUCTION This paper documents the significance of patients’ receiv- ing individualized information through dialogue-based contacts with healthcare professionals. This is exemplified by summarizing the state of knowledge on how men with prostate cancer, undergoing prostatectomy surgery, experi- ence their conta cts wit h the healthca re profes sionals . Secondary the paper points to the re levance in designing new health informatics tools that can support these dia- logue-based contacts by utilizing Web 2.0 technologies. Web 2.0 websites differ from the static web pages estab- lished on Web 1.0 technolog ies where the user s are limited to passive viewing. Web 2.0 technologies establish dy- namic websites, as for example the users can interact and collaborate with each other in a dialogue. 2. BACKGROUND Today’s he althcar e syst ems are ch aracter ised by shor t stays in hospital with planned d ischarge within on e, two, or three days even after large operations. This decreases the time and opportunity for contact between the patients and the healthcare professionals. As contacts are situations or con- ditions where persons are able to exchange information, attitudes, feelings and so on [1], these short contacts reduce the patients’ time for information and support. Patient satisfaction surveys show that the patients are satisfied with short hospital stays [2-4]. However, qu ali- tative studies have demonstrated that patients lack contact with healthcare professionals, and therefore often lack information and support [5-6]. This contradiction is ex- plored in depth by focusing on the defined group of pa- tients: Men with prostate cancer treated with prostatec- tomy surgery. The number of men diagnosed with prostate cancer has increased with over 51 percent from 2000 to 2009. In 2009 prostate cancer ranked as the most frequent cancer among men [7]. A growing number of these men are treated with surgery; radical prostatectomy. Previously, these men were hospitalized up to 19 - 20 days in rela- tion to the surg ery [8]. Currently th e stays in hospital, in relation to the surgery, are less than five days, which still  C. D. Bjørnes et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 1 (2011) 1-11 16 decreases to planned discharge the day after surgery. 3. METHOD Systematic review is selected as the data-gathering method for the study. 3.1 Aim The aim of this literature survey is to su mmarize the s tat e of knowledge on how men with prostate cancer experi- ence their contacts with the healthcare professionals and what these men need and do to feel secure and certain. The specific research questions were: 1) How do men with prostate cancer, treated with prostatectomy surgery, experience their contacts with the healthcare professionals in clinical practice based on short stays? 2) What do patients need to feel secure and certain? 3) What is the role of the Internet? 3.2 Literature Search The PubMed and CINAHL databases were searched. The inclusion criteria were English-language research articles. The study population was men with prostate cancer treated with prostatectomy surgery. When articles were of particular relevance related articles were ex- plored by lower the demand in relation to the population. Therefore some articles relate to studies on men with prostate cancer in general, though still including men with prostate cancer treated with prostatectomy surgery. The exclusion criteria were publication age older than 1997, due to the focus on short stays in hospital, in to- day’s healthcare system. The PICO schema (Figure 1) reports the search his- tory. The first and second research questions generated the search terms in the primary part of the literature search (primary search). Early findings [9-14] indicated that the Internet played a significant role, as this media was often mentioned in relation to information and sup- port. To understand the role of the Internet the first two research questions were followed by the third research question: What is the role of the Internet? The third re- search question generated the secondary part of the lit- erature search (secondary search). The Figure 1 also includes the exclusions of articles, when reading the abstracts: Due to the frequency of side effects as incon- tinence and sexual dysfunction after prostatectomy, the- se topics are wide-ranging in the literatu re. Articles, with these terms as major concept, were excluded if the ab- stracts did not include content of data related to the top- ics in current study. Reading abstracts from the secon- dary search excluded: Duplicates from the primary search, however, still including repeaters in relation to authors or findings generated in different areas of the same project. Excluded were also articles focusing on health informatics as decision support systems, as the population in current study already were in a course of treatment. Articles related to intervention studies were excluded, as these represented health informatics sys- tems that the patients were invited or asked to use. Figure 1. PICO schemas report the search terms. C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJN  C. D. Bjørnes et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 1 (2011) 1-11 17 Searching PubMed and CINAHL February 2011 ac cording to the search terms in the primary search, the re- sults were 78 in PubMed and three in CINAHL (Figure 2). Due to the small number in the CINAHL databases, the area was search through, as illustrated in the Sup- plementation. These supplementing searches expanded the number in the CINAHL to 56 including duplicates. Then the abstracts were read through. The numbers of relevant and research-based articles in the two databases were 29: 16 articles has specific focus on men with pro- state cancer treated with prostatectomy surgery, whe- reas 13 articles also include other groups of men with prostate cancer. When categorizing the 29 articles accor- ding to the methods: 13 articles document survey studies and one article combines survey and interview. The rest; 15 articles report use of various forms of interview stud- ies. In the secondary search the focus was still on the same group of patients though expanded to men with prostate cancer in general. PubMed identified 141 titles. Search- ing CINAHL identified 56 titles whereas some were du- plicates. The abstracts were read, leaving 18 research- based articles, which contribute to understanding the role of the Internet in relation to the specified focus on in- formation and communication according to the research questions. Six papers document findings from text an- alysis based on diverse philosophies. These studies ana- lyse text that were generated on websites, which host different forms of online social support. Seven papers report survey studies and five describe findings gener- ated by interview studies. Findings generated from a total of 47 articles are provided in relation to each of the three research questions. 4. RESULTS 4.1. How Do the Men with Prostate Cancer Experience Their Contact with the Healthcare Professionals? The patient satisfaction surveys document that the men with prostate cancer in general are satisfied with short hospital stays in relation to their surgery [8,15,16]. However, interview based studies contributes to a di- verse picture to that [9,10,12-14,17 -29]. Milne et al. de- scribe how the men had mixed perceptions about the benefit of short stays. This is underpinned by patients who explain how they were grateful that they had been allowed to stay in the hospital for two or three additional days. Sinfield et al. [28] conclude that although there were no widespread dissatisfaction, patients reported- problems throughout their course of care. One of the problems was that information needs were often not id- entified or met. The lack in information is documented in several studies [12,18,20,23,24,27 ]. Phillips et al. [24] emphasize how the patients felt that they could have been better prepared by the healthcare professionals, even in cases in which no complications occurred. Moo- re and Estey [23] writes that the information deficits aff- ected the patients’ quality of life and healthy postopera- tive rehabilitation. The short contacts reduce the patients’ time for infor- mation and support. Though, it does not seem to be the amount of time, more likely how to get in contact and the quality of these contacts. In other words, contacts presuppose both accessibility and exchange-ability. As depicted in the following, accessibility means availabil- ity; it must be easy for the patients to g et in contact with the healthcare professionals. And exchange-ability means; the ability to exch ange information, as an essential b asis for individualizing information. Harden et al. [20] explain how the perception that all the healthcare professionals are extremely busy, for ex- ample at the hospital, deters many patients from asking the healthcare professionals, because they feel uncom- fortable and self-conscious doing it. Hedestig et al. [21] describe how men with prostate cancer, btween their check-ups, often had difficulties containg the health care professionals or getting answers out of them, even though the men had questions they wanted to ask. This Figure 2. Number of research articles. C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJN  C. D. Bjørnes et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 1 (2011) 1-11 18 illustrates why healthcare professionals must be easily accessible during the patients’ course of treatment and care. The importance of accessibility is further describe by Harden et al. [20]. In their study, the men explain, how they function well most of the time, however, there were still ten percent of the time that was difficult. The men describe how their difficult issues easily became serious concerns and got out of proportion, when no one was listening to them. The men state that it would have been beneficial for them to have the opportunity to voice their concerns by having a person to call and ask a spe- cific question [20]. The study by Milne et al. [13] illus- trates how the accessibility is important. Milne et al. conclude that being home without readily and available support and advice from healthcare professionals caused anxiety and uncertainty. This is further underpinned by their own study, providing that the participants in the study experienced the researcher as an invaluable re- source. The researcher collected the data by telephone and E-mails both pre and postoperative. The study itself became an information and support-intervention, which the participants benefit from, as it h elped them to talk to the researcher and have the opening to telephone or E- mail the researcher [13]. It is essential that the patients experience the healthcare professionals as easily accessi- ble both at the hospital and when the patients are home. The importance of the ex change-ability is fo r example shown in the study by Iyigun et al. [27], as the men ex- plained how the information should be individualized: The healthcare professionals must keep the patients’ cultural level and psychological state in mind when pro- viding the information. Harden et al. [20] describe how the participants in their study told that the need for in- formation was great, but they all needed different infor- mation or needed it in a different way than others. The men wanted someone to listen to their specific ne eds an d fears and to help them find answers or just review in- formation. When a healthcare professional aimed to in- dividualize the information the men felt supported [20]. Again, it does not seem to be the amount of time, more likely the quality of the information and support, mean- ing the healthcare professionals ability to exchange ex- periences, and so on, to generate individualized informa- tion upon that. The men need the healthcare profession- als to build the information and support on their indi- vidual questions, experiences, and resources. The men require a contact where the healthcare professionals en- ter into a dialogue with them, as the dialogues are pre- requisite in individualising the information and support. A survey study by Smith et al. [30] document how a little more than half of the men express some levels of unmet psychological needs. Uncertainty about the future was for example an important area of unmet need. The dialogues are prerequisite if the healthcare professionals shall be able to discover such uncertainty and meet the needs of the particular patient. Thus, the healthcare pro- fessionals’ accessibility and ability to individualize in- formation and support, based on exchange-ability, are important aspects for men with prostate cancer treated with prostatectomy surgery. In summary, this section illustrates that even though the short contacts reduce the patients’ time for informa- tion and support it does not seem to be the amount of time that is most important. Instead it is how to get in contact with the healthcare professionals and the quality of the contacts, meaning the contacts need to be dia- logue-based. 4.2. What Do Patients Need to Feel Secure and Certain? The consequences, when men with prostate cancer lack dialogue with, and therefore information and support from, healthcare professionals, are explored by searching across the papers [9,12-14,20,21,23,24,27,28]. The find- ings are illustrated in Figure 3. As depicted, lacking information can start a negative process in which feel- ings of uncertainty and insecurity can affect the men’s ability to cope. When lacking information there is a risk that the men experience disempowerment, which is feelings of powerlessness or helplessness that reduces the amount of control that someone, has over a situation [1]. In contradiction, obtaining contact, enter dialogues, and receiving individualized information and support are related to experiences and feelings, which support the positive process (Figure 3). Empowerment is the proc- ess of giving somebody power in a particular situation; to give someone more control over their own life or the situation they are in [1]. In the paper by Iyigun et al. [27] the negative process is illustrated, as lack of knowledge causes insecurity. The study documents how the men felt anxious going home because they were afraid of complications. It is emphasized how the anxiety about going home is due to lack of adequate information from the healthcare profes- sionals. This is underpinned by the few men, who ob- tained information from the healthcare professionals, as they were more comfortable afterwards [27]. Sinfield et al. [28] explain that information interventions improve the patients’ knowledge and understanding. Individual- ized, clearly information and communication influence the patients’ ability to make decisions and participate. Butler et al. [10] identify how male cancer patients’ coping was influenced by receiving individualized in- formation. Thus Maliski et al. [12] conclude that health- care professionals can hasten thepatients’ ability to re- gain a sense of mastery by providing information and being available. C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJN  C. D. Bjørnes et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 1 (2011) 1-11 19 Figure 3. The negative and positive process of coping. C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJN  C. D. Bjørnes et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 1 (2011) 1-11 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. 20 OJN In summary, this section gives a picture of the impor- tance of receiving information and support in a course of treatment and care. By providing information and sup- port healthcare professionals may be able to empower the patients. The empowered patient is also the active patient. The healthcare professionals’ accessibility and ability to individualize information and support are important aspects for men with prostate cancer treated with pro- statectomy surgery, to feel secure and certain. By pro- viding information and support healthcare professionals supports the pati e nt s’ process of copi n g. 4.3. What Is the Role of the Internet? The findings illustrate how men with prostate cancer use the Internet to cope with the lacking information and support. They use the online media to get information about the diagnosis prostate cancer, treatment options, and other topics related to a course of treatment [31-40]. Another purpose is to achieve social support ; online social support [41-46]. Huber et al. [42] describe online social support as social interactions and Dickerson et al. [32] explain it as online friendship. The study by Dickerson et al. [32] illustrate how the important elements of social support exist in the Internet based groups. In the online social support groups, the patients share their stories, which contribute to recogni- tion and reflections, which again generate other perspec- tives and new knowledge. A patient, in their study, tells how using the Internet and recognising other people with identical problems were reassuring and helped him much. Another patient showed how sharing experiences with other patients generated insight and developed selfma- nagement skills. Huber et al. [42] emphasize that the Internet based social interactions can be important for the individual in coping with and during his own course of treatment. In general Iyigun et al. [27] explain how some men learn to cope themselves, when they are not receiving information or when facing problems, and therefore for example use the Internet. Van de Poll-Franse et al. [38] describe how patients by themselves searched for infor- mation on the Internet about the cancer, treatment, and the consequences of treatment in general. Their study illustrates how the patients use the Internet in every step of their course of treatment, though varying in relation to topics and amount of time. Most of the patients, who used the Internet to find information, felt themselves be- tter informed. Buntrock et al. [40] characterize the Inter- net users as information seekers and point to how these patients become active participants in their course of tr- eatment and care. Milne et al. [13] explain how men with prostate cancer use the Internet to be in front. The men experience a sense of confidence and control for example by consulting a variety of websites on the Internet prior to meetings with th e healthcare profession als. Broom [47] explains how the Internet allows the patients to “do something”. The patients experience themselves as com- petent and feel as they do not only rely on the doctor. The patients become capable to take part in decision- making, which also increase their sense of control over their treatment process. As such the Internet usage redu- ces the patients’ uncertainties and supports the patients’ involvement in making decision along their course of treatment [47]. Dickerson et al. [32] found that the pa- tients themselves felt more comfortable and knowledge- able by utilizing the Internet as a too l during their course of treatment. The Internet is a tool that generated under- standings, for example about one’s own situation. Dic- kerson et al. describe that men with cancer incorporate Internet use into their cancer journey and become prob- lem solvers. The men use the Internet to enhance their sense of control. The men seek to be proactive, prepared, and responsible, and thereby trying to change the pro- vider-patient relationships towards collaboration and op- en communication. The men use the Internet information for verification and to clarify, compare, and validate the information obtained during their course of treatment and care. Dickerson et al. [32] point to how the men became experts at finding resources online to confirm their deci- sions, realizing the need to make choices, and to monitor their progress or possible reoccurrence. The men use the Internet to stay in control and engage in their own course of treatment as active and responsible partners. 5. DISCUSSION The aim of this literature survey was to summarize the state of knowledge on how men with prostate cancer, treated with prostatectomy surgery, experience their con- tact with the healthcare professionals. A relative small number of studies were found. None had a defined focus on these men and their experience of contacts with heal- thcare professionals. However, this article reviews the literature for men’s experience on themes relevant in the contact between men and healthcare professionals: In- formation; support; and dialogues. The literature survey identified that the patients often do not receive the individualized support, information, and dialogue that they need. As a result of the lack of contact, the men struggle with feelings of insecurity and uncertaint y, often fol l o wed by loss of contr ol. Even so the men had mixed feelings about the short stays at hospital. The contradiction based on different research methods, as illustrated in the introduction, is comparable with these findings. Though the interview  C. D. Bjørnes et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 1 (2011) 1-11 21 based studies that were reviewed specify the difficulties. This elaboration gives an understanding of the com- plexity of and cor relations in human m eaning. The s hort st ays in hospital limits and defines the time for contact between the patients and the healthcare professionals, as the contacts are both dated and categorized. However the patients’ need for contact cannot be define d in the sam e matter. The accessibility of the healthcare professionals and the healthcare professionals’ ability to individualize in- formation and support are important aspects for men with prostate cancer treated with prostatectomy surgery. The opportunity for male patients to get in contact with healthcare professionals, an d th e quality of these con tacts, is related to male patients’ chance to feel secure and to stay in control. The men require a contact where the heal- thcare professionals enter into a dialogue with them, as the dialogues are prerequisite for individualising the informa- tion and support. A literature survey by Shaha et al. [48] document that people with cancer in general often experience uncer- tainty due to lack of information. Shaha et al. [48] illus- trate how uncertainty is present in different, and often in all, phases of a cancer trajectory, although with varying intensity and based on diverse issues. Shaha et al. em- phasize the importance of information, support, and in- dividual approaches to care to minimize the negative aspects of uncertainty, especially in the light of the in- creasing ambulatory approaches to cancer care in general. A general conclusion, in the literature, is that there is still a need to develop new ways and too ls to provide the patients with information and support. Based on an in- tervention study using survey evaluation Berglund et al. [49] support this significant conclusion and describes that this is a crucial task for the healthcare sector. Heal- thcare professionals seem to recognize the importance of providing individual information and support, but need to determine the best manner in which to provide it and foremost important to incorporate it into practice [12, 18,20,23]. Sharpley et al. [50] stress that the ideal format for patient information still needs to be id entified, which require further research. For instance how to include the provision of information, assist with navigating through large amounts of information, dispelling misinformma- tion, encouraging acquisition of self-care skills, and pro- viding individual information and support to decrease insecurity. Especially, when having men as patients it can be relevant to develop new health informatics tools. The findings illustrate that men with prostate cancer use the Internet to get information and support. The men use the Internet to stay in control and engage in their own course of treatment as active and responsible partners. Though every single patient is an individual, there are indications of differences men versus women as patients. Dickerson et al. [32] describe how men focus on problem solving, determine effects, treatments, and symptom management in a functional way. Male cancer patients actively org an iz e information, monitor for reoccurrence, prepare, facilitate, and validate ahead of their contacts with healthcare pro- fessionals. Previous studies, with focus particularly on men as patients, state that male patients want to in stay control and remain autonomy. Men like to act. Therefore information, advice, and tools that support actions, are important in their course of treatment [50-57]. Hence, it is relevant to provide male cancer patien ts with tools th at can underpin their contact to and dialogues with the heal- thcare professionals. The short stays in hospital limits and defines the time for contact between the patients and the healthcare profession- als, as the contacts are both dated and categorized. However the patients’ need for contact cannot be defined in the same matter. The men require a contact where the healthcare pro- fessionals enter into a dialogue with them, as the dialogues are prerequisite for individualising the information and support. The relatively new Internet technologies Web 2.0 establish dynamic websites, which allow the users to do more than just retrieve information, as on Web 1.0 sites [1 ]. Thereby Web 2.0 websites differ from the static web pages established on Web 1.0 technolog ies where the users are li- mited to passiv e viewi ng. A We b 2.0 we bsite allo ws user s to interact and collaborate with each other in a dialogue. Users can provide and control the data on a Web 2.0 site. The contents are u ser-genera ted and th e us er s are intera c tiv e and able to communicate with each other. The asynchronous environments, which the Web 2.0 technologies prov ide, are a significan t way to expand the time for contacts besides the restricted formal face-to-face contacts at hospital. Utilizing this expansion in flexible time healthcare professionals have the opportunity to comply with the contradiction between the patients’ needs for contact and the intensifying of pa- tients’ short stays at hospital. The course of care can go be- yond the formal face-to-face contacts between the patients and the healthcare professionals, so that the patients have the opportunity to feel informed and supported, and the- reby empowered, even at home. As such the online asyn- chronous health informatics tools can be one of the com- ponents to accommodate these organisational changes. In general, it is suggested that healthcare professionals do have a responsibility in creating Internet based reli- able information and online social support groups for the patients. This is consistent with the findings, when fo- cusing on men with prostate cancer. Broom [47] exp- lains how the empowering of the patients changed the roles between the patients and the healthcare profession- C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJN  C. D. Bjørnes et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 1 (2011) 1-11 22 als, as the Internet allows the patients to act. The pa- tients’ activities are grounded on the information on the Internet, whether it is reliable or not. As illustrated Dic- kerson et al. [32] describe that the men use the online information to validate the information from the health- care professionals. However, the patients are also aware of the importance of checking the qu ality of the informa- tion available on the Internet. Therefore most of the men consider the information cautiously. Van de Poll-Franse et al. [38] emphasize the importance of healthcare pro- fessionals taking active part in the future use and devel- opment of Internet based tools. Pautler et al. [34] specify the importance in healthcare professionals participating in the development of information websites, as these may influence the patients’ decisions regarding treatment. Hence, the healthcare professionals may acknowledge the role of Internet in their contact with each patient. Fur- t he rm o re , the healthcare professionals may use their organi- sations websites to provide comprehensive and reliable in- formation. Healthcare professionals’ active involvement in devel- oping Internet based tools is consistent with the patients’ request, as Van de Poll-Franse et al. [38] document. The patients prefer to get reliable information from websites made, or recommend, by thei r healthcare professionals, for example the oncologist and the hospital. Hence, using the Internet actively, the healthcare professionals would have a tool to underpin their contact wit h the patient s. Many patients describe their wishes about future use of the Internet, for example access to medical files and test results [38]. Two survey based studies report men’s interest in [58] and satisfaction with [59] access to their own medical record. Cathala et al. supplemented the me- dical files by inviting the patients to fill out quality of life questionnaires to document treatment outcome. A contact page allows the patient and physician to exchange infor- mation by text. In both studies [58,59] the men appraised the access to the Internet medical record positively and the researchers emphasize the relevance in further de- veloping. Based on the surveys it is indicated that the contact to the doctor becomes closer and the patients are more capable to engage in shared medical decision mak- ing with their doctor. However, the questionnaire-based findings did not reveal whether the access to medical records or the exchanging of information actually seem- ed to be more individualized or managed to meet the pa- tients’ individual needs in support, information, and dia- logue [58,59]. Therefore, it seems relevant that both healthcare professionals and patients not only are involved when evaluating new health informatics tools, but also are engaged in future design and development of health informatics systems. Limitations The defined population and research questions generated a relative limited number of articles. Furthermore, sev- eral papers were excluded, because their focus was mainl y incontinence. Some of these papers could have been relevant in relation to the concrete population. However the overall focuses were contacts, dialogues, information, and support, in the light of short stay surgery, and not long term complications after surgery. The area of health informatics tools expands quickly. This can for example be illustrated by the increasing number of decision support systems to men with prostate cancer. According to the exclusion criteria, studies related to that topic were not a part of the current study. These arti- cles could have contributed to the third research question: What is the role of the Internet? However the answer to the third research question shall be seen in relation to the first and second research questions. The research questions are generated from a problem experienced in nursing care. Looking at the search terms it is clear that the study is born in nursing. Expanding the search terms to other professions for example doctors and to the health informatics field wou ld potentially give various perspectives. Though, the patients needs, will be identical. 6. CONCLUSIONS The literature survey identify that men with prostate cancer treated with prostatectomy surgery often do not receive the individualized support, information, and dia- logue they need. Because of that the men struggle with feelings of uncertainty, insecurity, and loss of control. However, contacts based on short stays at the hospital seem to be acceptable for men with prostate cancer, treated with prostatectomy surgery. The importance, in relation to the patients’ contact with healthcare professionals, is not the length and amount of time. Instead accessibility and exchange-ability are significant aspects. For men to feel secure and certain, the healthcare professionals must be easy to get in contact with during the whole course of treatment and care. Concurrently, the healthcare profes- sionals’ ability to exchange information, and thereby to individualize information and support based on dialogues with the particularly man, is essential. Providing infor- mation and support healthcare professionals may be able to empower the patients, and the empowered patient is also the active patient. The findings demonstrate that men with prostate cancer use the Internet in their search for information and sup- port. The Internet he lps the men to stay in control and to engage in their own course of treatment as active and responsible partners. 7. PRACICE IMPLICATIONS The results may be a starting point for the development C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJN  C. D. Bjørnes et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 1 (2011) 1-11 23 of new health informatics tools by combining Web 1.0 technologies with Web 2.0 technologies. Seeing that it is relevant to provide male cancer patients with tools that can underpin their contacts to and dialogues with the healthcare professionals and in combination, the Internet is already a common used media. It seems relevant that both healthcare professionals and patients are engaged in future development of health informatics systems, as a collaborative development and use of Internet based tools could underpin the exchange-ability, towards dialogue- based contacts between men with prostate cancer and healthcare professionals. 8. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors wish to acknowledge funding from: The Novo Nordisk Foundation, DOF Det Obelske Familiefond, Danish Nursing Research Society, Harboefonden. The funding source had no involvement in the study. There is no conflict of interest for the authors associated with this study. The manuscript is revised by: Lene Sømod Flou, BA in English Languages, Staff Member with University Degree, Aalborg University. REFERENCES [1] Ordbogen.com. Ordbogen.com. Danmarks største online ordbog (The large online dictionary in Denmark). (2011) Retrieved from http://www.ordbogen.com/. Ref Type: Computer Program [2] Marx, C.I., Rasmussen, T., Jakobsen, D.H., Ottosen, C., Lundvall, .L. and Ottesen, B.S. et al. (2006) Accelerated course after operation for ovarian cancer. Ugeskrift for Læger, 168, 1533-1536. [3] Husted, H., Hansen, H.C., Holm, G., Bach-Dal, C., Rud, K. and Anderse n, L.K. et al. (2006) Accelerated versus conven- tional hospital stay in total hip and knee arth- roplasty III: pa- tient satisfaction. Ugeskrift for Læger, 168, 2148-2151. [4] Kehlet, H. (2001) Accelererede operationsforløb. (Acce- lerated surgical stay programs—a professional and adm- inistrat ive c hal len ge). Ugeskrift for Læger, 163, 420-424. [5] Wagner, L., Carlslund, A.M., Moller, C. and Ottesen, B. (2004) Patient and staff (doctors and nurses) experiences of abdominal hysterectomy in accelerated recovery progr- amme. A qualitative study. Danish Medical Bulletin, 51, 418-421. [6] Norlyk, A. (2008) The experience of fast track posto- perative rehabilitation regimen: The patients’ perspective. Kli- nisk Sygepleje, 22, 53-63. [7] Cancerregisteret, (2009) Cancer Register 2009. Sundhe- dsstyrelsen, National Board of Health. [8] Litwin, M.S., Shpall, A.I. and Dorey, F. (1997) Patient sa- tisfaction with short stays for radical prostatectomy. Ur- ology,49, 898-905. doi:org/10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00103-9 [9] Burt, J., Caelli, K., Moore, K. and Anderson, M. (2005) Radical prostatectomy: men’s experiences and postopera- tive needs. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 14, 883-890. d oi: or g/ 10. 1111/j .1365-2702.2005.01123.x [10] Butler, L., Downe-Wamboldt, B., Marsh, S., Bell, D. and Jarvi, K. (2001) Quality of life post radical prostatectomy: a male perspective. Urology Nursing, 21, 283-288. [11] Coreil, J. and Behal, R. (1999) Man to Man prostate can- cer support groups. Cancer Practice, 7, 122-129. doi:org/10.1046/j.1523-5394.1999.07307.x [12] Maliski, S.L., Heilemann, M.V. and McCorkle, R. (2001) Mastery of postprostatectomy incontinence and impoten- ce: his work, her work, our work. Oncology Nursing Fo- rum, 28, 985-992. [13] Milne, J.L., Spiers, J.A. and Moore, K.N. (2007) Men’s experiences following laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: A qualitative descriptive study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 45, 765-774. [14] Powel, L.L. and Clark, J.A. (2005) The value of the mar- ginalia as an adjunct to structured questionnaires: experi- ences of men after prostate cancer surgery. Quality of life research: An International Journal of quality of life as- pects of treatment, care and rehabilitation, 14, 827- 835. [15] Kirsh EJ, Worwag EM, Sinner M, Chodak GW (2000) Using outcome data and patient satisfaction surveys to de- velop policies regarding minimum length of hospitalization after radical prostatectomy. Urology, 56, 101-106. doi:org/10.1016/S0090-4295(00)00594-X [16] Klein, E.A., Grass, J.A., Calabrese, D.A., Kay, R.A, Sargeant, W. and O'Hara, J.F. (1996) Maintaining quality of care and patient satisfaction with radical prostatectomy in the era of cost con tainm ent . Urology, 48, 269 -276. doi:org/10.1016/S0090-4295(96)00160-4 [17] Jakobsson, L. (2002) Indwelling catheter treatment and health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer in comparison with men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 16, 264-271. doi:org/10.1046/j.1471-6712.2002.00096.x [18] Davison, B.J., Moore, K.N., MacMillan, H., Bisaillon, A., Wiens, K. (2004) Patient evaluation of a discharge pro- gram following a radical prostatectomy. Urology Nursing, 24, 483- 489. [19] Gray, R.E., Fitch, M.I., Philli ps, C., Labrec que, M., Klotz, L. (1999) Presur ger y experien ces of pros tat e can cer pa tien ts a nd their spouses. Cancer Practice , 7, 130-135. doi:org/10.1046/j.1523-5394.1999.07308.x [20] Harden, J., Schafenacker, A., Northouse, L., Mood, D., Smi- th, D. and Pienta, K. et al. (2002) Couples’ experiences with prostate cancer: focus group research. Oncology Nursing Forum, 29, 701-709. doi:org/10.1188/02.ONF.701-709 [21] Hedestig, O., Sandman, P.O., Tomic, R. and Widmark, A. (2005) Living after radical prostatectomy for localized pros- tate cancer: a qualitative analysis of patient narratives. Acta Oncologica, 44, 679-686. doi:org/10.1080/02841860500326000 [22] Jakobsson, L., Hallberg, I.R. and Loven, L. (1997) Met and unmet nursing care needs in men with prostate cancer. An explora tive study. Part II. European Journal of C ancer Ca re, 6, 117-123. doi:org/10.1046/j.1365-2354.1997.00020.x [23] Moore, K.N. and Estey, A. (1999) The early post-operative concerns of men after radical prostatectomy. Journal of Ad- vanced N ursi ng, 29, 1121-112 9. doi:org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.00995.x [24] Phillips, C., Gray, R.E., Fitch, M.I., Labrecque, M., Fergus, K. and Klotz, L. (2000) Early postsurgery experience of prostate cancer patients and spouses. Cancer Practice, 8, 165-171. doi:org/10.1046/j.1523-5394.2000.84009.x C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJN  C. D. Bjørnes et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 1 (2011) 1-11 24 [25] Rondorf-Klym, L.M. and Colling, J. (2003) Quality of life after radical prostatectomy. Oncology Nursing Forum, 30, E24-E32. doi:org/10.1188/03.ONF.E24-E32 [26] Boberg, E.W., Gustafson, D.H., Ha wkins, R.P., Offord, K.P., Koch, C., Wen, K.Y. et al. (2003) Assessing the unmet in- formation, support and care delivery needs of men with prostate cancer. Patient Education and Counselling, 49, 233-242. doi:org/10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00183-0 [27] Iyigun, E., Ayhan, H. and Tastan, S. (2009) Perceptions and experiences after radical prostatectomy in Turkish men: A descriptive qualitative study. Applied Nursing Research, 24, 101-109. doi:org/10.1016/j.apnr.2009.04.002 [28] Sinfield, P., Baker, R., Agarwal, S. and Tarrant, C. (2008) Patient-centred care: What are the experiences of prostate cancer patients and their partners? Patient Education and Counselling, 73, 91-96 . doi:org/10.1016/j.pec.2008.05.001 [29] Hedestig, O. (2006) Att leva med lok aliserad prostatacancer. “Oss män emellan”. (Living with localised prostate cancer. between men). Department of Radiation Sciences, Oncol- ogy, and Department of Nursing, Medical Faculty, Umeaa University, Sweden. [30] Smith, D.P., Supramaniam, R., King, M.T., Ward, J., Be- rry, M. and Armstrong, B.K. (2007) Age, health, and edu- cation determine supportive care needs of men youn- ger than 70 years with prostate cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Cli- nical Oncology, 25, 2560-2566. [31] Davison, B.J., Keyes, M., Elliott, S., Berkowitz, J. and Goldenberg, S.L. (2004) Preferences for sexual infor- mation resources in patients treated for early-stage pros- tate cancer with either radical prostatectomy or brachythe- rapy. British Association of Urological Surgeons, 93, 965- 969. [32] Dickerson, S.S., Reinhart, A., Boemhke, M. and Akhu- Za- heya, L. (2010) Cancer as a problem to be solved: internet use and provider communication by men with cancer. Computers, Informatics, Nursing: CIN, Epub ahead of print Oct 21. [33] Nagler, R.H., Romantan, A., Kelly, B.J., Stevens, R.S. and Gray, S.W., et al. (2010) How Do Cancer Patients Navigate the Public Information Environment? Under- standing Patterns and Motivations for Movement Among Information Sources. Journal of Cancer Education: The Official Journal of the American Association for Cancer Education, 360-370. [34] Pautler, S.E., Tan, J.K., Dugas, G.R., Pus, N., Ferri, M. and Hardie, W.R. et al. (2001) Use of the internet for self- education by patients with prostate cancer. Urology, 57, 230-233. doi:org/10.1016/S0090-4295(00)01012-8 [35] Pinnock, C.B. and Jones, C. (2003) Meeting the infor- mation needs of Australian men with prostate cancer by way of the internet. Urology, 61, 1198-1203. doi:org/10.1016/S0090-4295(03)00016-5 [36] Ramsey, S.D., Zeliadt, S.B., Neeraj, K.A. and Arnold, L.P., et al. (2009) Access to information sources and treatment considerations among men with local stage prostate cancer. Urology, 74, 509-515. [37] Rozmovits, L. and Ziebland, S. (2004) What do patients with prostate or breast cancer want from an Internet site? A qualitative study of information needs. Patient Educa- tion and Counselling, 53, 57-64. doi:org/10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00116-2 [38] Poll-Franse, L.V.V.D. and Eenbergen, V.M.C.H.J. (2008) Internet use by cancer survivors: current use and future wishes. Support Care Cancer, 16, 1189-1195. doi:org/10.1007/s00520-008-0419-z [39] Ziebland, S. (2004) The importance of being expert: the quest for cancer information on the Internet. Social Scien- ce & Medicine, 59, 1783-1793. doi:org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.02.019 [40] Buntrock, S., Hopfgarten, T., Adolfsson, J., Onelo, E. and Steineck, G. (2007) The Internet and prostate cancer pa- tients. Searching for and finding information. Scandi- na- vian Journal of Urology and Nephrology, 41, 367-374. doi:org/10.1080/00365590701303827 [41] Gooden, R.J. and Winefield, H.R. (2007) Breast and pros- tate cancer online discussion boards: a thematic ana- lysis of gender differences and similarities. Journal of Health Psychology, 12, 103-114. doi:org/10.1177/1359105307071744 [42] Huber, J., Ihrig, A. and Peters, T., et al. (2010) Decision- making in localized prostate cancer: lessons learned from an online support group. BJU International, Epub ahead of print. [43] Klemm, P., Hurst, M., Dearholt, S.L. and Trone, S.R. (1999) Gender differences on Internet cancer support gr- oups. Computers in Nursing, 17, 65-72. [44] Owen, J.E., Klapow, J.C., Roth, D.L. and Tucker, D.C. (2004) Use of the internet for information and support: disclosure among persons with breast and prostate cancer. Journal of Behavioural Medicine, 27, 491-505. doi:org/10.1023/B:JOBM.0000047612.81370.f7 [45] Seale, C., Ziebland, S. and Charteris-Black, J. (2006) Gender, cancer experience and internet use: a comparative keyword analysis of interviews and online cancer support groups. Social Science & Medicine, 62, 2577-2590. doi:org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.016 [46] Sullivan, C.F. (2003) Gendered cybersupport: a thematic analysis of two online cancer support groups. Journal of Health Psychology, 8, 83-103. doi:org/10.1177/1359105303008001446 [47] Broom, A. (2005) The impact of internet use on disease experience and the doctor-patient relation ship. Qualitative Health Research, 15, 325-345. doi:org/10.1177/1049732304272916 [48] Shaha, M., Cox, C.L., Talman, K. and Kelly, D. (2008) Uncertainty in breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer: imp- lications for supportive care. Journal of Nursing Sch- olar- ship, 40, 60-67. d oi: or g/ 10. 1111/j .1547-5069.2007.00207.x [49] Berglund, G., Petersson, L.M., Eriksson, K.R. and Hagg- man, M. (2003) “Between men”: patient perceptions and priorities in a rehabilitation program for men with pros- tate cancer. Patient Education and Counselling, 49, 285- 292. doi:org/10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00186-6 [50] Sharpley, C.F. and Christie, D.R. (2007) Patient informa- tion preferences among breast and prostate cancer patients. Australasian Radiology, 51, 154-158 [51] Agger, N.P. and Ølgod, J. (2001) Mænd og kræft. An- befalinger og handlingskatalog til alle der arbejder med mandlige kræftpatienter. Men and Cancer. Recom- men- dations and Catalogue of Actions for Professionals Work- ing with Male Cancerpatients, Kræftens Bekæmpelse, the Danish cancer society. C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJN  C. D. Bjørnes et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 1 (2011) 1-11 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. 25 OJN [52] Agger, N.P. (2002) Mænd. (Men). Mennesker Med Kræft. (P e op le wi th Ca n ce r ), Copenh agen, Munksgaard. [53] Joergensen, S.E. (1999) Mænd med kræft-en intervie- wundersøgelse, Men with Cancer—A Interview Study, the Danish cancer society. [54] Johnsen, A.T. (2006) Kræftpatientens verden-en under- søgelse af, hvilke problemer danske kræft patienter opl eve r. Litteraturgennemgang og interviews. (The world of a can- cer patient—a survey on problems experienced by Da- nish cancer patients. A Survey of the Literature and Inte- rviews, bispebjerg hospital. [55] Olsen, H., Gram, J. and Madsen, S.A. (2007) Uddannelse i kommunikation og dialog med mænd. Kompendium med fokus på mænds sundhed og sygdomme. (Instruction in communication and dialogue with men. A Compen- dium with Focus on Men in Health and Illness, Men’s Health Week. [56] Ølgod, J. (1999) Breve fra mænd med kræft. Letters from Men with Cancer, the Danish cancer soci ety. [57] Simonsen, S.S. (2006) Mænd, sundhed og sygdom-Ron- kedorfænomenet. Men, Health and Illness. [58] Pai, H.H. and Lau, F. (2005) Web-based electronic health information systems for prostate cancer patients. The Canadian Journal of Urology, 12, 2700-2709 [59] Cathala, N., Brillat, F., Mombet, A., Lobel, E., Prapotnich, D. and Alexandre, L. et al. (2003) Patient followup after radical prostatectomy by Internet medical file. The Jour- nal of Urology, 170, 2284-2287. doi:org/10.1097/01.ju.0000095876.39932.4a

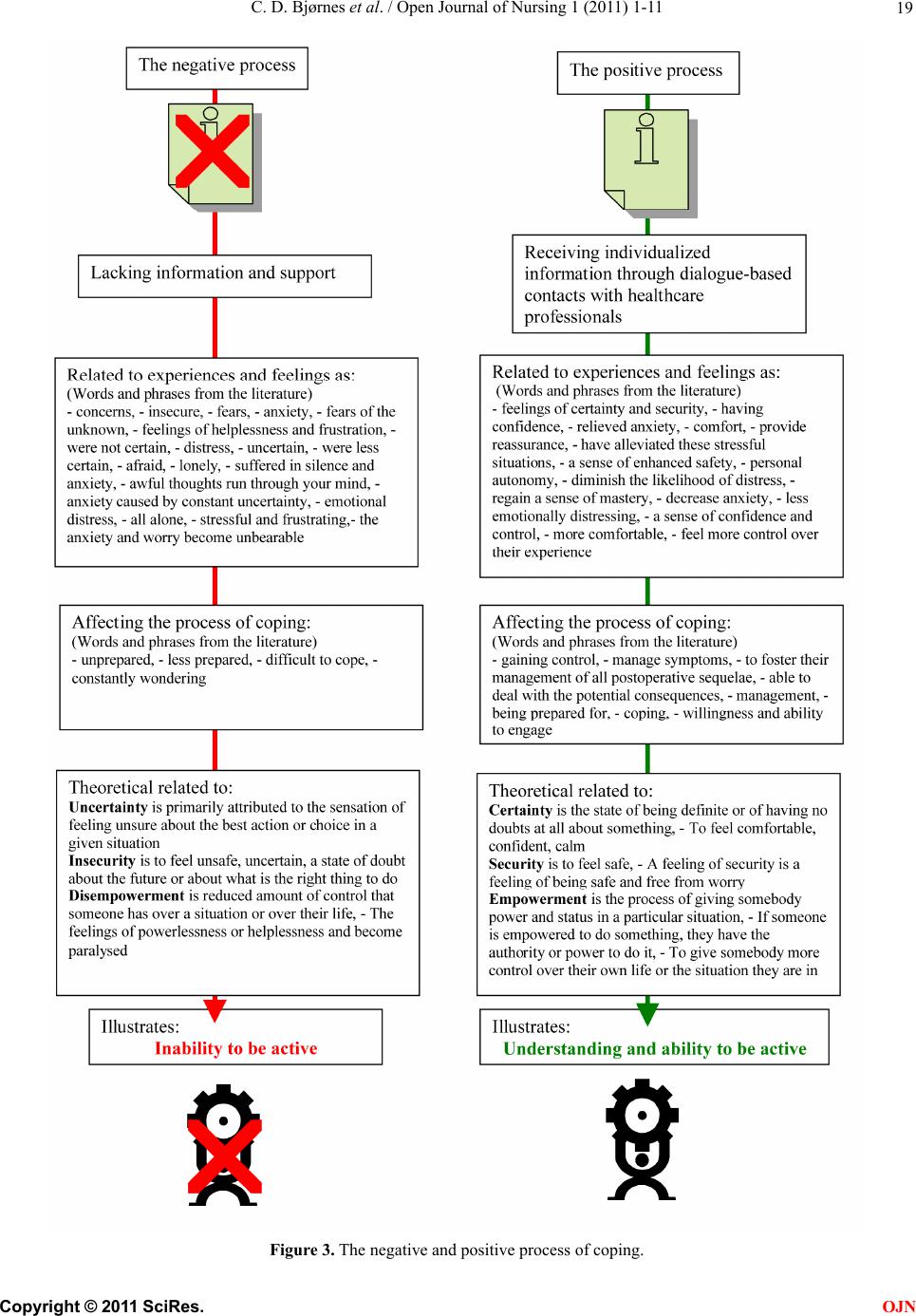

|