Open Journal of Stomatology, 2011, 1, 92-102 doi:10.4236/ojst.2011.13015 Published Online September 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/OJST/ OJST ). Published Online September 2011 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJST Non-odontogenic toothache revisited Ramesh Balasubramaniam1*, Lena N. Turner2, Dena Fischer3, Gary D. Klasser4, Jeffrey P. Okeson5 1School of Dentistry, University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia; 2Department of Oral Medicine, School of Dental Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, America; 3Department of Oral Medicine and Diagnostic Sciences, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, A merica; 4Division of Diagnostic Sciences, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Centre, School of Dentistry, New Orleans, America; 5Department of Oral Health Science, University of Kentuck y, Lexington, America. Email: *ramesh.balasubramaniam@uwa.edu.au Received 17 May 2011; revised 23 June 2011; accepted 5 July 2011. ABSTRACT Although pain of dental origin is the most common orofacial pain, other non-odontogenic pains can af- fect the orofacial region and occasionally mimic den- tal pain. These non-odontogenic pains may pose a diagnostic dilemma for the dental practitioner who routinely diagnoses and treats dental pain. Knowl- edge of the various non-odontogenic pains will ulti- mately prevent misdiagnosis and the delivery of in- correct and sometimes irreversible and invasive pro- cedures to patients. The purpose of this article is to review the clinical presentations of the various types of non-odontogenic pains which may be mistaken as dental pain: myofascial, cardiac, sinus, neurovascular, neuropathic, neoplastic and psychogenic pain. Keywords: Non-Odontogenic Toothache; Orofacial Pain 1. INTRODUCTION The orofacial region is the mo st frequent site for patients seeking medical attention for pain [1,2] with 12.2% of the population reporting dental p ain as th e most co mmon orofacial pain [3]. Consequently, it is common for pain in the orofacial region to be mistaken for a toothache, and similarly, other pains of the head and neck to mimic odontogenic pain. Therefore, orofacial pain may pose a diagnostic dilemma for the dental practitioner. Under- standing the complex mechanism of odontogenic pain and the manner in which other orofacial structures may simulate pain in the tooth is paramount in determining the correct diagnosis and appropriate treatment. The purpose of this article is to: a) provide the dental practitioner with an understanding of pain etiology to consider when developing differential diagnoses for orofacial pains, and b) review various types of non- odontogenic pains which may be mistaken for a tooth- ache. Ultimately, this article will aid the dental practi- tioner with preventing misdiagnosis and delivery of in- correct and sometimes irreversible procedures for non- odontogenic pains. 2. CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF ODONTOGENIC PAIN Odontogenic pain is generally derived from either one of two structures associated with the tooth: pulpal or pe- riodontal tissue. Although the mechanisms for both are of inflammatory origin, their distinct functionality and embryologic origin [4] results in each pain being per- ceived differently. Pulpitis is the most common cause of odontogenic pain [2] and can be divided into two cate- gories: reversible and irreversible. Reversible pulpitis indicates that pulpal tissues can repair with the removal of the local irritant and restoration of the tooth structure. It is often characterized by a fleeting pain up on provoca- tion and does not occur spontaneously. Irreversible pul- pitis has a prolonged duration of pain when stimulated but may also occur spontaneously. As a visceral organ, pain of the dental pulp is charac- terized by deep, dull, aching pain that may be difficult to localize [5]. It may present as intermittent or continuous, moderate or severe, sharp or dull, localized or diffuse and may be affected by the time of day or position of th e body [6]. After prolonged periods of intense pain, re- ferred pain may be produced due to central excitatory effects [7]. The quality of pain may vary based upon the vitality of the too th as well as the extent of inflammation. Following prolonged periods of inflammation, pulpal necrosis may occur. Also, there may be other causes of pulpal pain that may be difficult to identify such as “cracked tooth syndrome” whereby a crack or craze may develop within the tooth [6]. Periodontal pain is more readily localized and identi- fiable because of proprioceptors located within the pe-  R. Balasubramaniam et al. / Open Journal of Stomatology 1 (2011) 92-102 93 riodontal ligament. Therefore, periodontal pain will fol- low the characteristics of p ain of musculoskeletal origin. The periodontal receptors are able to accurately localize the pain whether they are lateral or apical to the tooth. Acute apical periodontitis may be the result of pulpal necrosis. Similarly, a lateral periodontal abscess may be a source of odontogenic pain and may be associated with clinical signs such as edema, erythema and swelling of the gingival [6]. The diagnosis of pulpal and periodon- tal pain is often easily established and once diagnosed, treatment is directed at alleviating the etiology. In rare cases, odontogenic pain can present as an enigma con- fusing the clinician. However, the clinician should be mindful that dental pain is the most common orofacial pain. 3. CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF NON-ODONTOGENIC PAIN The clinical presentation of non-odontogenic pain is varied and may mimic other pain disorders which may not originate in the orofacial region. The extent of pain may vary from very mild and intermittent pain to severe, sharp, and continuous. Furthermore, pains that are felt in the tooth do not always originate from dental structures, so it is important to distinguish between site and source of pain to provide correct diagnosis and appropriate treatments. The site of pain is where the pain is felt by the patient, whereas the source of pain is the structure from which the pain actually originates. In ‘primary’ pain, the site and source of pain are coincidental and in the same location. That is, pain occurs where damage to the structure has occurred. Therapy for primary pain is obvious and does not pose a diagnostic dilemma for the clinician. Pain with different sites and sources of pain, known as heterotopic pains, can be diagnostically challenging. Once diagnosed, treatment should be posed at the source of pain, rather than the site. Neurologic mechanisms of heterotopic pain is not well understood but it is thought to be related to central effects of constant nociceptive input from deep structures such as muscles, joints and ligament [8]. Although the terms heterotopic pain and referred pain are often used interchangeably, there are specific distinc- tions between these terms. Heterotopic pain can be di- vided more specifically into 3 general types: a) central pain, b) projected pain, and c) referred pain [4]. Central pain is simply pain derived from the central nervous system (CNS) resulting in pain perceived peripherally. An example of central pain is an intracranial tumor as this will not usually cause pain in the CNS because of the brain’s insensitivity to pain but rather it is felt pe- ri phe rally. Proj ected pain is pain felt in the peripheral dis- tribution of the same nerve that mediated the primary no- ciceptive input. An example of projected pain is pain felt in the dermatomal distribution in post-herpetic neuralgia. Referred pain is spontaneous heterotopic pain felt at a site of pain with separate innervation to the primary source of pain. It is thought to be mediated by sensitization of in- terneurons located with in the CNS. Pain referred from the sternocleidomastoid muscle to the temporomandibular joint is an example of referred pain [4]. The remainder of this article will focus on non-odontogenic pains of odontogenic origi n. 3.1. Myofascial Toothache Skeletal muscle triggers are well recognized in the lit- erature [9,10] and are illustrated by trigger point map- ping achieved through palpation of the muscles and de- scribing the locations of pain referral [11,12]. The trigger point, a localized hyperexcitable nodule within the mus- cle, is theorized to be a result of microscopic neuromus- cular dysfunction at the motor endplate [12]. As it cannot be identified histologically or by imaging, there is con- troversy as to the true existence of the trigger point [12,13]. Clinically, palpating a firm, tender nodule within a sufficiently irritable muscle may reproduce referred pain to distant regions upon sustained pressure [12,14]. Hong et al. were able to reproduce referred pain 80% of the time by palpation of the trigger point with sufficient pressure for up to 10 seconds [15]. An additional study was able to reproduce muscle pain with dry needling of the muscle in 62% of the cases [15]. The theory of convergence supports the mechanism that is thought to cause pain referral to the trigeminal sensory complex from other areas of nociceptive input although it is not well understood. It has been reported that at least half of the trigeminal nociceptive neurons are able to be activated by stimulation outside their nor- mal receptive field [16]. Studies on myofascial pain re- ferral to other regions of the orofacial region have found that pain from: a) temporalis muscles referred pain to the maxillary teeth, b) masseter muscles referred pain to the maxillary and mandibular posterior teeth, ear and temporomandibular joint (TMJ), c) lateral pterygoid muscles referred pain to the maxillary sinus region and TMJ, d) anterior digastric muscles referred pain to the mandibular incisors, and e) sternocleidomastoid mus- cles referred pain to oral structures and the forehead [11 ,12,17]. Additionally, palpation of the trapezius mus- cle often refers pain to the mandible or temporalis mus- cle regions [4,12]. The myofascial toothache is described as non-pulsatile and aching pain and occurs more continuously than pul- pal pain [6]. Patients are unable to accurately locate the source of the pain and often believe pain is originating C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJST  R. Balasubramaniam et al. / Open Journal of Stomatology 1 (2011) 92-102 94 from the tooth. Tooth sensitivity to temperature, percus- sion or occlusal pressure may be felt as a result of re- ferred pain from the offending muscle [12]. Pain tends to be associated with extended muscle use and exacerbated with emotional stressors, rather than direct provocation of the affected tooth [6]. Palpation of the trigger point is able to reproduce the toothache, even modulate the pain by increasing or eliminating it altogether [6]. In spite of this, it has been reported that 7% of cases were referred for endodontic treatment when the primary source of pain was the muscle of mastication [18]. Linn et al. reported that 37% of patients diagnosed with muscular orofacial pain had previously undergone endodontic or exodontic treatment in an attempt to alleviate their pain [19]. Alleviation of the toothache is often achieved when local anesthetic is administered to the strained muscle (source of pain) rather than the tooth (site of pain). Warm or cold compresses, muscle stretching, massage, and a restful sleep may alleviate both the muscle and tooth pain. Elimination of the trigger point and pain of the muscle should be the aim of the treatment rather than the tooth itself [1,6]. 3.2. Cardiac Toothache Cardiac pain is an additional source of referred pain to the jaw mainly due to cardiac ischemia. Angina pectoris is a symptomatic presentation of ischemic heart disease that is often used in congruence with cardiac ischemia. Cardiac ischemia more commonly presents with subster- nal pain and radiation to the left shoulder and arm [6]. When cardiac pain presents in the orofacial region com- monly affected areas include pain(s) in the neck, throat, ear, teeth, mandible and headache [20-24]. In some cases, orofacial pain is the only complaint in association with cardiac ischemia. In one study, 6% of patients presenting with coronary symptoms had pain solely in the orofacial region while 32% had pain referred elsewhere. Interest- ingly, bilateral referred craniofacial pain was noted more commonly than unilateral pain at a ratio of 6:1 [20]. The mechanism of cardiac pain likely involves multi- ple nociceptive mediators with bradykinin being the most important, evoking a sympathoexcitatory reflex [25] and inducing a sympathetic response of the heart [26-28]. Although widely accepted, there is controversy as to whether the sympathetic response is responsible for the transmission of pain. Studies on patients who underwent sympathectomies demonstrated a 50% - 60% complete relief of angina pectoris, while 40% obtained a partial relief, and 10% - 20% experienced no relief [29]. Vagal afferent response is thought to also play a role in the response to cardiac ischemia although its role is not clearly defined [30,31]. Based on the anatomic dis- tribution, vagal afferents could be activated when the infero-posterior surface of the heart is affected, while sympathetic response is due to stimulation of the anterior portion [29]. A recent case report suggests an association between vagal stimulation and toothache in a patient undergoing experimental treatment with a vagal nerve stimulator for the treatment of depression [32]. Episodes of tooth pain were coincidental to duration and fre- quency of nerve stimulation and once appropriate ad- justments to the stimulator parameters were made, the dental pain subsided. Vagal stimulation has been utilized in other treatments such as drug resistant epilepsy, and reports of similar painful side effects such as jaw and tooth pain as well as throat and neck pain have been noted [33-36]. Consequently, there may be a physiologic association between vagal stimulation initiated by car- diac ischemia and odontogenic pain. Mechanisms of convergence and central sensitization in the trigeminal nerve complex can also explain pain referred to orofacial structures [4]. Cardiac nociceptive input travels to the central nervous system and ascends to higher centers for processing in regions of conver- gence, where adjacent nociceptive neurons may become activated [37]. The stimulation of adjacent neurons that are not directly involved in the primary source of pain may be misinterpreted in the cortex, causing an uninten- tional pain input being referred to other regions and re- sulting in heterotop ic pain. Alternate sources of pain should be considered when local anesthetic and analgesics fail to alleviate dental symptoms. Appropriate questioning and thorough medi- cal history are essential in identifying the true source of pain, especially when a cardiac toothache is suspected. Clinical characteristics of pain may vary between pa- tients. Pain may be episodic, lasting from minutes to hours, and varies in intensity, although almost invariably is precipitated by exertional activ ities an d alleviated with rest [37]. Intriguingly, patients experiencing cardiac pain reported the descriptor of “pressure” more often when compared to any other disorder [38]. If the pain is associated with cardiac or chest pain, it is most often relieved by sublingual nitroglycerin and im- mediate referral to a medical practitioner is imperative. 3.3. Sinus Toothache Sinusitis is a common aliment in the US, resulting in about 16 million visits to the ph ysician annually [39,40]. Approximately, 15% of the population reports it as a chronic problem, [41] with about 10% of maxillary si- nusitis cases being diagnosed as having an odontogenic origin [42]. Since the roots of the maxillary dentition are in intimate contact with, and often protruding into, the sinus cavity, it is comprehensible that th e dentition cou ld be a potential source of sinus inflammation and infection. C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJST  R. Balasubramaniam et al. / Open Journal of Stomatology 1 (2011) 92-102 95 As the maxillary sinus grows, its final point o f growth is coincidental with the growth of the maxillary alveolar process and eruption of the permanent dentition. This may result in a protrusion of roots into the sinus cavity that, in some cases, may be separated only by the Schneiderian membrane (mucoperiosteum) [43]. Due to the close proximity between maxillary poste- rior roots and the maxillary sinus, an infectious process in the dentition or surrounding periodontal tissue may present as an acute or chronic sinusitis; conversely, in- flammation and infection originating in the maxillary sinus may be perceived as odontogenic pain. Patients may present with facial pain and pressure in the maxil- lary posterior region. Other symptoms such as headache, halitosis, fatigue, cough, nasal discharge/drainage or congestion and ear pain may be more identifiable as be- ing associated with sinus disease [44]. Sinus pain can also present as a continuous dull ache or diffuse linger- ing pain in the maxillary teeth [8,45] with sensitivity to percussion, mastication, and/or temperature. This hy- persensitivity is often felt in multiple teeth, making it more indicative of a pain of sinus origin rather than odontogenic pain [8,46]. Often a history of respiratory infection, nasal conges- tion, and sinus disease may precede the onset of the toothache [8]. Pain may be elicited by palpation of the infraorbital regions or maneuvering the head to below the levels of the knees, initiating gravitational shifting of fluid in the sinus [8,47]. The absence of an offending tooth or gingival inflammation upon intraoral examina- tion may further lead to the conclusion that there is sinus inflammation or infection. Although chronic sinusitis may erode the wall of the sinus, it is rarely associated with intraoral soft tissue swelling or pain [48]. Intraoral or panoramic radiographs may be useful to exclude the dentition as being the source of the problem. The sinu ses may appear cloudy, opacified, and congested on the panoramic radiograph. Increased fluid levels and thick- ening of the sinus mucosal membrane may be apparent on CT scan [8]. Once identified, treatment should be directed toward the maxillary sinus infection. Most cases of acute sinusitis are of viral origin and require nasal decongesttants, a therapy targeted at reducing the soft tissue edema to allow drainage of the sinus through the ostium into the middle meatus of the nasal cavity [46]. In the cases of bacte- ria-induced sinusitis, a regimen of antibiotics is addition- ally prescribed [46]. Management is beyond the scope of a dental professional and appropriate referral to an otorhi- nolaryngologist or the general medical practitioner is ap- propriate once there is a clear understanding that the source of the odontogenic pain is of sinus origin. 3.4. Neurovascular Toothache Neurovascular pains or headache is a common complaint. Typically “headache” is pain localized to the cranium. However, headache may also present as a variant involv- ing the orofacial region hence mimicking toothache. Two primary headache types that may present as toothache are migraine and trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia (Table 1). The 1-year period prevalence for migraine is 11.7% (17.1% in women and 5.6% in men) [49]. Migraines are typically unilateral, moderate to severe pains of pulsatile and throbbing quality that are often disabling. Pain usu- ally lasts between 4 and 72 hours and may b e aggr avated by routine physical activities. Migraine is often accom- panied by nausea, vomiting, phonophobia and/or photo- phobia and may present with (20%) or without aura (80%). An aura is a reversible focal neurological symp- tom (visual, sensory and motor phenomena) that devel- ops between 5 and 20 minutes, subsides within 60 min- utes and is immediately followed by a headache [50]. Although its prevalence is unknown, Migraine may present in the midface without involvement of the first division of the trigeminal nerve [51]. Also there are a few case reports of patients with oral and dental pain subsequently diagnosed as migraine [52,53]. Obermann et al. [54] in a case series involving 7 patients reported migraine presenting in the face occurred more often in the maxillary division than the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve. Apart from location, the migraine limited to the orofacial region is similar to “cranial” mi- graine. Penarrocha et al. [55] reviewed 11 patients with “lower-half facial migraine” and reported that 45% had endodontic treatment prior to initially developing pain. Four of these patients reported a history of migraine prior to the development of “lower-half facial migraine”. Of concern, the average time elapsed prior to proper diagnosis was 101 months (6 to 528 months). Also, 36% of cases had teeth extracted in an attempt to treat the pain. Benoliel et al. [56] diagnosed 23 of 328 patients with “neurovascular orofacial pain” over a 2-year period and proposed an expansion of the current International Headache Society classification to include orofacial pain syndromes. Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias (TACs) are a col- lective term that refers to a group of headaches charac- terized by unilateral head and/or face pain with accom- panying autonomic features [50,57]. The International Classification of Headache Disorders II (ICHD-II) clas- sifies TACs as: 1) episodic or chronic cluster headache (CH); 2) episodic or chronic paroxysmal hemicrania (PH) and 3) Short-lasting Unilateral Neuralgiform headache attacks with Conjunctiv al injection and Tearing (SUNCT) C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJST  R. Balasubramaniam et al. / Open Journal of Stomatology 1 (2011) 92-102 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. 96 OJST headache [50]. Although rare, TACs may present a challenge for the dentist due to its often overlapping and similar presenta- tions to true odontogenic pains (Table 1). Individuals often describe the location of pain due to CH emanating from the midface region which may be interpreted as pain originating from the teeth, jaws or the temporo- mandibular joints [58,59]. Bahra and Goadsby [60] re- ported that 45% of a group of CH patients were seen by a dentist prior to receiving the correct diagnosis. They also found that a misdiagnosis provided by a dentist of- ten led to unnecessary and inappropriate dental proce- dure(s). In another study, it was found that 42% of 33 CH patients received some form of invasive and irre- versible dental procedure as their treatment [61]. It has been postulated that dental extractions may be a precipi- tating factor for CH. Penarrocha et al., [62] in a study of 54 CH patients, found that prior tooth extraction or en- dodontics had been performed in the pain affected quad- rant in 31 (58%) of the subjects and in the contralateral quadrant in 18 (33%) subjects. Additionally, they found that in 24 (44%) cases, tooth extraction was performed after the onset of pain in an attempt to solve the problem with only 1 patient repo rting improveme nt. Due to the short duration of attacks, recurrences, ex- cruciating intensity and pulsatile pain quality found in PH, it is possible that this disorder may be mistaken for dental pulpitis [63]. It is also not uncommon for PH to manifest in the maxillary region thereby being mistaken for tooth pain [64]. Benoleil and Sharav [65] reported on 7 PH cases, 4 of which had been confused for pain of dental origin. Two of these patients received irreversible dental treatments. Other studies have reported similar occurrences whereby the spectrum of failed dental treatment ranged from pharmacological approaches to full mouth reconst ru ct ion [52,66-68]. Although rare, there are case reports in which SUNCT patients, in addition to facial pain, complain of pain ra- diating to adjacent teeth. This has resulted in dentists delivering therapeutic interventions for tooth pain such as extraction, occlusal splints and incorrect pharmacol- ogy [69-71]. In order for dentists to avoid the pitfalls of providing unnecessary interventions for misdiagnosed toothaches of neurovascular origin, they must perform a thorough history and comprehensive clinical examina- tion. If this process does not yield convincing evidence of pain from an odontogenic origin then referral to the appropriate practitioner sho uld be pursued. 3.5. Neuropathic Toothache Neuropathic pain refers to a pain that originates from abnormalities in the neural structures and not from the tissues that are innervated by those neural structures. These pains pose significant difficulty for the clinician since the structures the patient reports as painful appear clinically normal. There are two types of neuropathic pains that can be felt in teeth: episodic and continuous. Table 1. Differentiating features of neurovascular pain and dental pain [111,112]. Feature Migraine Cluster Paroxysmal hemicrania SUNCT Acute pulpal pain Chronic pulpal pain Periodontal pain Sex (male:fem ale) 1:3 5:1 1:2 2:1 1:1 1:1 1:1 Age (years) 10 - 50 20 - 40 30 40 - 70 any age any age any age Pain type pulsating boring boring electric-likethrobbing or aching tender or aching tender or aching Pain severity moderate to severe very severevery severe very severemild to severe mild mild Pain location frontotemporal orbital orbital orbital tooth tooth tooth/gingival /bone Pain duration 4 - 72 hours 15 - 180 minutes 2 - 30 minutes 15 - 240 seconds seconds to daily constant variable Pain frequency 1/month 1 - 8/day 2 - 40/day 3 - 200/dayvariable Daily Daily Autonomic features No; may have with aura Yes Yes Yes No No No Trigger stress, foods, vasodilators, sleep pattern changes, afferent stimulation, hormonal changes alcohol, nitrates mechanical cutaneous electric & thermal stimulation, tooth percussioninconsistent apical or lateral tooth pressure  R. Balasubramaniam et al. / Open Journal of Stomatology 1 (2011) 92-102 97 Episodic neuropathic pain is characterized by sudden volleys of electric-like pain referred to as neuralgia. The most typical example of this type of pain is trigeminal neuralgia. When this type of paroxysmal pain is felt in a tooth it can pose significant diagnostic challenges for the clinician. The clinical presentation of an episodic neuro- pathic toothache is a severe, shooting, electric-like pain that lasts only a few seconds [4,72,73]. The pain is not always restricted to a tooth but often a broader area. The pain is not altered by intraoral thermal stimuli [4,6,72]. It rarely awakes the patient from sleep unlike dental pain. The most common branch of the trigeminal nerve in- volved is the mandibular followed by the maxillary and least involved is the ophthalmic [4,72]. The pain is often severe with patients reporting the pain as being the most intense they have ever experienced. Often the patient is able to trace the pain radiating down the distribution of the nerve to the tooth [6]. With trigeminal neuralgia there is often a trigger zone that, when lightly stimulated, provokes the severe par- oxysmal pain. Anesthetic blocking of the trigger zone will completely eliminate the toothache and paroxysmal episodes during the period of anesthesia. On occasion a tooth can represent the trigger zone, and if this occurs, it can pose a great diagnostic challenge for the clinician. Patients with trigeminal neuralgia frequently receive endodontic treatment for their dental pain [74,75]. Addi- tional case repor ts also provide examples of the opposite diagnostic problem: patients with odontogenic dental pain being diagnosed as having trigeminal neuralgia [76]. In both types of misdiagnosis, the lack of response to treatment is a key factor in prompting reassessment of the differential diagnosis. Continuous neuropathic pains are pain disorders that have their origin in neural structures and are expressed as constant, ongoing and unremitting pain. They will often have high and low intensity but no periods of total remission. Continuous neuropathic pains that can be felt in teeth have been referred to as atypical odontalgia [77,78] or sometimes phantom toothache [79,80]. Con- tinuous neuropathic pain appears to have its origin asso- ciated with central plasticity in the trigeminal nuclear complex of the brain stem [81]. In some instances there may be a sympathetic component to the pain [82]. Pa- tients with continuous neuropathic toothache often report a history of trauma or ineffective dental treatment in the area [83]. In a study of 42 patients with atypical odon- talgia, 86% of the patient population was female and 78% reported maxillary pain. Of 119 reported areas of pain, the most common were the molar (59%), premolar (27%), and canine (4%) regions [84,85]. The pain may change in location over time; some studies have reported pain shifting location in up to 82% of the subjects [82,86]. It is not unusual for patients with continuous neuro- pathic toothache to have received multiple endodontic treatments or extractions for their dental pain [84,86-90]. In many cases, the lack of response to treatment is a key factor in prompting reassessment of the differential di- agnosis [91]. Ram et al. [92] in their retrospective study involving 64 patients reported that 71% had initially consulted a dentist for their pain complaint, and sub- sequently 79% of patients received dental treatment that did not resolve the pain. In one case report, the lack of an effect of a local anesthetic injection on reducing the intensity of pain was a significant finding that pro- mpted consideration of non-odontogenic tooth pain [90]. The following characteristics of continuous neuro- pathic toothache can be used to differentiate it from odontogenic pain: a) diffuse pain, b) pain not always restricted to a tooth (e.g., the area may be edentulous), c) pain that is almost always continuous, d) a pain quality often described as a dull, aching, throbbing, or burning, e) pain that may or may not be relieved by a diagnostic intraoral local anesthetic block, f) pain that often lasts more than 4 months, and g) pain not altered by intraoral thermal stimuli [4,6,82,85,88,93,94]. 3.6. Neoplastic Toothache Orofacial pain may be the initial symptom of oral cancer and can motivate patients to seek care from their dental practitioners. Primary squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the oral mucosa may present with pain and sensory disturbances that mimic toothache symptoms particu- larly when located on the gingiva, vestibule or floor of mouth. One retrospective case series found pain to be the first clinical sign of oral cancer in 19.2% of cases [95], while other literature has suggested that two-thirds of patients with oral cancer have reported localized dis- comfort within the 6 months preceding a cancer diagno- sis [96]. Primary intraosseous carcinoma is a SCC that occurs within the ja ws, has no initial con n ection with the oral mucosa, and arises from either a previous odonto- genic cyst or de novo [97]. These malignancies are ex- tremely rare, but when they do occur, they can be mis- taken for odontogenic origin since the clinical presenta- tion of localized bone loss may have the appearance of localized periodontal disease. Nasopharyngeal cancers may present with signs and symptoms that have been confused with, and treated as, temporomandibular disorders [98,99], parotid gland le- sions [100], and odontogenic infections with trismus [101]. While signs and symptoms of nasopharyngeal carcinomas may mimic temporomandibular disorders, such as facial pain, limited j aw opening, deviation of the C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJST  R. Balasubramaniam et al. / Open Journal of Stomatology 1 (2011) 92-102 98 jaw on opening, earache, and headache [98,99], some of these signs may also be found and confused with an odontogenic et i ology. Systemic cancers such as lymphoma and leukemia may have intraoral manifestations that mimic toothache- like symptoms. Such can cers can infiltrate pain-sensitive structures such as periosteum and gingiva, thereby caus- ing localized pain that may be confused with odonto- genic and/or periodontal conditions [102]. In rare cir- cumstances, the osseous osteolytic lesions of multiple myeloma may develop adjacent to teeth. When this oc- curs, odontogenic pain is common and presents a ra- diologic diagnostic challenge as the osteolytic lesions appear to be associated with teeth but are actually related to the systemic disease [103]. Orofacial pain has also been reported in patients with distant non-metastasized cancers, most commonly from the lungs [104-107]. In such circumstances, the facial pain is almost always unilateral affecting the ear, jaws and temporal region, frequently described as severe and aching, and usually continuous and progressive. Such a presentation may be confused with referred pain of odontogenic origin. Orofacial pain may be associated with metastatic ma- lignancies and when metastatic orofacial tumors occur, they affect the jaw bones more often than the oral soft tissues [108]. Metastases most often develop from the breast in women and the lung and prostate in males, with the most common sites of occurrence in the jaws being the posterior mandible, angle of the jaw, and ramus [108, 109]. Pain is a rare complaint in soft tissue metastases [11 0], whereas in metastatic disease of the jaw bones, pain has been reported in 39% and paresthesias in 23% of patients [111]. The pain and clinical presentation can be misinterpreted as that originating from an odonto- genic source. In a retrospective case series of metastatic disease in the jaws, 60% of 114 cases reported the me- tastatic lesion in th e oral region to be th e first indication of an undiscovered primary malignancy at a distant site [109]. Signs and symptoms of orofacial malignancies may mimic odontogenic etiology. It is important for dental practitioners to use appropriate judgment when clinical findings do not correlate with the results of odontogenic diagnostic testing. Neoplastic toothache must be consid- ered when localized soft or hard tissue changes develop in close proximity to odontogenic structures and diag- nostic findings are equivocal or negative. 3.7. Psychogenic Toothache Psychogenic pain is pain that is associated with psy- chologic factors in the absence of any physiologic cause. The American Psychiatric Association has classified this condition as a somatoform pain disorder [112], indicat- ing that clear evidence of a causal relationship between pain and psychologic factors is not required. While psy- chologic factors may be implicated, pain conditions clas- sified under this definition may occur without th e role of psychologic factors [113]. Pain descriptors are often diffuse, vague, and difficult to localize [113]. When the somatoform pain disorder is felt in the teeth, multiple teeth are often involved [6]. Pain may be sharp, stabbing, intense, and sensitive to temperature changes, all of which are similar to pain symptoms of odontogenic origin. However, the pain is inconsistent with normal patterns of physiologic pain and presents without any identifiable pathologic cause. When accompanied by other psychiatric features such as hallucinations or delusions, there is a greater possibility that the pain is of psychogenic origin [113]. Given that psychogenic toothache is a somatoform disorder, dental treatment will not resolve symptoms of pain and may poten tially elicit an unexpected or unusual response to therapy [6]. Patients should be referred to a psychiatrist or psychologist for further management. 4. CONCLUSIONS There are a multitude of non-odontogenic pains that can present at the site of a tooth and can mimic a toothache. Dental practitioners should also have an understanding of the complex mechanism of odontogenic pain and the manner in which other orofacial structures may simulate dental pain. In patients who present with toothache pain, dental practitioners should consider alternate etiologies of the pain when appropriate diagnostic tests do not lead to odontogenic etio logy. Failure to establish the etiology of the pain will result in incorrect diagnosis and inap- propriate treatment. REFERENCES [1] Sarlani, E., Balciunas, B.A., and Grace, E.G. (2005) Orofacial pain—Part II: Assessment and management of vascular, neurovascular, idiopathic, secondary, and psy- chogenic causes. AACN Clinical Issues, 16, 347-358. doi:10.1097/00044067-200507000-00008 [2] Annino, D.J. and Goguen, L.A. (2003) Pain from the oral cavity. Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America, 36, 1127-1135. doi:10.1016/S0030-6665(03)00132-4 [3] Lipton, J.A., Ship, J.A. and Larach-Robinson, D. (1993) Estimated prevalence and distribution of reported orofa- cial pain in the United States. The Journal of the Ameri- can Dental Association, 124, 115-121. [4] Okeson, J.P. (2005) Bell’s orofacial pains: The clinical management of orofacial pain. Quintessence, Chicago. [5] Ikeda, H. and Suda, H. (2003) Sensory experiences in relation to pulpal nerve activation of human teeth in dif- ferent age groups. Archives of Oral Biology, 48, 835-841. C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJST  R. Balasubramaniam et al. / Open Journal of Stomatology 1 (2011) 92-102 99 doi:10.1016/S0003-9969(03)00176-6 [6] Okeson, J.P. and Falace, D.A. (1997) Nonodontogenic toothache. Dental Clinics of North America, 41, 367-383. [7] Falace, D.A., Reid, K. and Rayens, M.K. (1996) The influence of deep (odontogenic) pain intensity, quality, and duration on the incidence and characteristics of re- ferred orofacial pain. Journal of Orofacial Pain, 10, 232-239. [8] Okeson, J.P. (2000) Non-odontogenic toothache. North- west Dent, 79, 37-44. [9] Davidoff, R.A. (1998) Trigger points and myofascial pain: Toward understanding how they affect headaches. Cephalalgia, 18, 436-448. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.1998.1807436.x [10] Mense, S. (2003) The pathogenesis of muscle pain. Cur- rent Pain and Headache Reports, 7, 419-425. doi:10.1007/s11916-003-0057-6 [11] Fricton, J.R., Kroening, R., Haley, D. and Siegert, R. (1985) Myofascial pain syndrome of the head and neck: A review of clinical characteristics of 164 patients. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, 60, 615-623. doi:10.1016/0030-4220(85)90364-0 [12] Simons, D.G., Travell, J.G. and Simons, L.S. (1999) Travell and Simons’ myofascial pain and dysfunction: The trigger point manual. 2nd Edition, Williams & Wil- kins. [13] Jerjes, W., Hopper, C., Kumar, M., Upile, T., Madland, G., Newman, S., et al. (2007) Psychological intervention in acute dental pain: Review. British Dental Journal, 202, 337-343. doi:10.1038/bdj.2007.227 [14] Fricton, J.R. (1995) Management of masticat ory myofas- cial pain. Seminars in Orthodontics, 1, 229-243. doi:10.1016/S1073-8746(95)80054-9 [15] Hong, C.Z., Kuan, T.S., Chen, J.T. and Chen, S.M. (1997) Referred pain elicited by palpation and by needling of myofascial trigger points: A comparison. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 78, 957-960. doi:10.1016/S0003-9993(97)90057-5 [16] Sessle, B.J., Hu, J.W., Amano, N. and Zhong, G. (1986) Convergence of cutaneous, tooth pulp, visceral, neck and muscle afferents onto nociceptive and non-nociceptive neurones in trigeminal subnucleus caudalis (medullary dorsal horn) and its implications for referred pain. Pain, 27, 219-235. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(86)90213-7 [17] Wright, E.F. (2000) Referred craniofacial pain patterns in patients with temporomandibular disorder. The Journal of the American Dental Association, 131, 1307-1315. [18] Ehrmann, E.H. (2002) The diagnosis of referred orofacial dental pain. Australian Endodontic Journal, 28, 75-81. doi:10.1111/j.1747-4477.2002.tb00388.x [19] Linn, J., Trantor, I., Teo, N., Thanigaivel, R. and Goss, A.N. (2007) The differential diagnosis of toothache from other orofacial pains in clinical practice. Australian Dental Journal, 52, 100-104. doi:10.1111/j.1834-7819.2007.tb00518.x [20] Kreiner, M., Okeson, J.P., Michelis, V., Lujambio, M. and Isberg, A. (2007) Craniofacial pain as the sole symptom of cardiac ischemia: A prospective multicenter study. The Journal of the American Dental Association, 138, 74-79. [21] Tzukert, A., Hasin, Y. and Sharav, Y. (1981) Orofacial pain of cardiac origin. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, 51, 484-486. doi:10.1016/0030-4220(81)90006-2 [22] Batchelder, B.J., Krutchkoff, D.J. and Amara, J. (1987) Mandibular pain as the initial and sole clinical manifesta- tion of coronary insufficiency: Report of case. The Jour- nal of the American Dental Association, 11 5, 710-712. [23] Takayanagi, K., Fujito, T., Morooka, S., Takabatake, Y. and Nakamura, Y. (1990) Headache angina with fatal outcome. Japanese Heart Journal, 31, 503-507. doi:10.1536/ihj.31.503 [24] Ishida, A., Sunagawa, O., Touma, T., Shinzato, Y., Ka- wazoe, N. and Fukiyama, K. (1996) Headache as a mani- festation of myocardial infarction. Japanese Heart Jour- nal, 37, 261-263. doi:10.1536/ihj.37.261 [25] Veelken, R., Glabasnia, A., Stetter, A., Hilgers, K.F., Mann, J.F. and Schmieder, R.E. (1996) Epicardial bra- dyki nin B 2 rec ep to rs el ic i t a sympathoexcitatory reflex in rats. Hypertension, 28, 615-621. [26] White, J.C. (1957) Cardiac pain: Anatomic pathways and physiologic mechanisms. Circulation, 16, 644-655. [27] Staszewska-Barczak, J. and Dusting, G.J. (1977) Sympa- thetic cardiovascular reflex initiated by bradykinin-in- duced stimulation of cardiac pain receptors in the dog. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiol- ogy, 4, 443-452. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1681.1977.tb02408.x [28] Pal, P., Koley, J., Bhattacharyya, S., Gupta, J.S. and Koley, B. (1989) Cardiac nociceptors and ischemia: Role of sympathetic afferents in cat. The Japanese Journal of Physiology, 39, 131-144. doi:10.2170/jjphysiol.39.131 [29] Meller, S.T. and Gebhart, G.F. (1992) A critical review of the afferent pathways and the potential chemical media- tors involved in cardiac pain. Neuroscience, 48, 501-524. doi:10.1016/0306-4522(92)90398-L [30] Meller, S.T., Lewis, S.J., Ness, T.J., Brody, M.J. and Gebhart, G.F. (1990) Vagal afferent-mediated inhibition of a nociceptive reflex by intravenous serotonin in the rat. I. characterization. Brain Research, 524, 90-100. [31] James, T.N. (1989) A cardiogenic hypertensive chemore- flex. Anesth Analg, 69, 633-646. doi:10.1213/00000539-198911000-00016 [32] Myers, D.E. (2008) Vagus nerve pain referred to the cra- niofacial region. A case report and literature review with implications for referred cardiac pain. British Dental Journal, 204, 187-189. doi:10.1038/bdj.2008.101 [33] Liporace, J., Hucko, D., Morrow, R., Barolat, G., Nei, M., Schnur, J., et al. (2001) Vagal nerve stimulation: Adjust- ments to reduce painful side effects. Neurology, 57, 885- 886. [34] Rush, A.J., Marangell, L.B., Sackeim, H.A., George, M.S., Brannan, S.K., Davis, S.M., et al. (2005) Vagus nerve stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: A randomized, controlled acute phase trial. Biological Psychiatry, 58, 347-354. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.05.025 [35] Carius, A. and Schulze-Bonhage, A. (2005) Trigeminal pain under vagus nerve stimulation. Pain, 118, 271-273. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2005.07.022 [36] Shih, J.J., Devier, D. and Behr, A. (2003) Late onset la- ryngeal and facial pain in previously asymptomatic vagus nerve stimulation patients. Neurology, 60, 1214. [37] Kreiner, M. and Okeson, J.P. (1999) Toothache of cardiac origin. Journal of Orofacial Pain, 13, 201-207. C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJST  R. Balasubramaniam et al. / Open Journal of Stomatology 1 (2011) 92-102 100 [38] Kreiner, M., Falace, D., Michelis, V., Okeson, J.P. and Isberg, A. (2010) Quality difference in craniofacial pain of cardiac vs. dental origin. Journal of Dental Research, 89, 965-969. doi:10.1177/0022034510370820 [39] Fagnan, L.J. (1998) Acute sinusitis: A cost-effective ap- proach to diagnosis and treatment. American Family Physician, 58, 1795-1802, 1805-1806. [40] (2000) Antimicrobial treatment guidelines for acute bac- terial rhinosinusitis. Sinus and Allergy Health Partnership. Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, 123, 5-31. [41] Piccirillo, J.F., Mager, D.E., Frisse, M.E., Brophy, R.H. and Goggin, A. (2001) Impact of first-line vs second-line antibiotics for the treatment of acute uncomplicated si- nusitis. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 286, 1849-1856. doi:10.1001/jama.286.15.1849 [42] Mehra, P. and Murad, H. (2004) Maxillary sinus disease of odontogenic origin. Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America, 37, 347-364. doi:10.1016/S0030-6665(03)00171-3 [43] Brook, I. (2006) Sinusitis of odontogenic origin. Otolar- yngology—Head and Neck Surgery, 135, 349-355. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2005.10.059 [44] Osguthorpe, J.D. and Hadley, J.A. (1999) Rhinosinusitis. Current concepts in evaluation and management. Medical Clinics of North America, 83, 27-41. doi:10.1016/S0025-7125(05)70085-7 [45] Falk, H., Ericson, S. and Hugoson, A. (1986) The effects of periodontal treatment on mucous membrane thicken- ing in the maxillary sinus. Journal of Clinical Periodon- tology, 13, 217-222. doi:10.1111/j.1600-051X.1986.tb01463.x [46] Kretzschmar, D.P. and Kretzschmar, J.L. (2003) Rhinos- inusitis: Review from a dental perspective. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and Endodontology, 96, 128-135. doi:10.1016/S1079-2104(03)00306-8 [47] Murphy, E. and Merrill, R.L. (2001) Non-odontogenic toothache. Journal of the Irish Dental Association, 47, 46-58. [48] Rafetto, L. (1999) Clinical examination of the maxillary sinus. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America, 11 , 35-44. [49] Lipton, R.B., Bigal, M.E., Diamond, M., Freitag, F., Reed, M.L. and Stewart, W.F. (2007) Migraine preva- lence, disease burden, and the need for preventive ther- apy. Neurology, 68, 343-349. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000252808.97649.21 [50] Olesen, J. (2004) The international classification of head- ache disorders. Cephalalgia, 24, 9-160. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2003.00824.x [51] Lovshin, L.L. (1977) Carotidynia. Headache, 17, 192- 195. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.1977.hed1705192.x [52] Alonso, A.A. and Nixdorf, D.R. (2006) Case series of four different headache types presenting as tooth pain. Journal of Endodontics, 32, 1110-1113. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2006.02.033 [53] Namazi, M.R. (2001) Presentation of migraine as odon- talgia. Headache, 41, 420-421. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4610.2001.111006420.x [54] Obermann, M., Mueller, D., Yoon, M.S., Pageler, L., Diener, H. and Katsarava, Z. (2007) Migraine with iso- lated facial pain: A diagnostic challenge. Cephalalgia, 27, 1278-1282. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01413.x [55] Penarrocha, M., Bandres, A. and Bagan, J.V. (2004) Lower-half facial migraine: A report of 11 cases. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 62, 1453-1456. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2004.01.027 [56] Benoliel, R. and Sharav, Y. (2008) Neurovascular orofa- cial pain. Cephalalgia, 28, 199-200. [57] Goadsby, P.J. and Lipton, R.B. (1997) A review of par- oxysmal hemicranias, SUNCT syndrome and other short-lasting headaches with autonomic feature, includ- ing new cases. Brain, 120, 193-209. doi:10.1093/brain/120.1.193 [58] Brooke, R.I. (1978) Periodic migrainous neuralgia: A cause of dental pain. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, 46, 511-516. doi:10.1016/0030-4220(78)90381-X [59] Gross, S.G. (2006) Dental presentations of cluster head- aches. Current Pain and Headache Reports, 10, 126-129. doi:10.1007/s11916-006-0023-1 [60] Bahra, A. and Goadsby, P.J. (2004) Diagnostic delays and mis-management in cluster headache. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica, 109, 175-179. doi:10.1046/j.1600-0404.2003.00237.x [61] Bittar, G. and Graff-Radford, S.B. (1992) A retrospective study of patients with cluster headaches. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, 73, 519-525. doi:10.1016/0030-4220(92)90088-8 [62] Penarrocha, M., Bandres, A., Penarrocha, M.A. and Ba- gan, J.V. (2001) Relationship between oral surgical and endodontic procedures and episodic cluster headache. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology Oral Ra- diol Endod, 92, 499-502. doi:10.1067/moe.2001.116153 [63] Sarlani, E., Schwartz, A.H., Greenspan, J.D. and Grace, E.G. (2003) Chronic paroxysmal hemicrania: A case re- port and review of the literature. Journal of Orofacial Pain, 17, 74-78. [64] Antonaci, F. and Sjaastad, O. (1989) Chronic paroxysmal hemicrania (CPH): A review of the clinical manifesta- tions. Headache, 29, 648-656. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.1989.hed2910648.x [65] Benoliel, R. and Sharav, Y. (1998) Paroxysmal hemicra- nia. Case studies and review of the literature. Oral Sur- gery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and Endodontology, 85, 285-292. doi:10.1016/S1079-2104(98)90010-5 [66] Benoliel, R., Elishoov, H. and Sharav, Y. (1997) Orofa- cial pain with vascular-type features. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and Endo- dontology, 84, 506-512. doi:10.1016/S1079-2104(97)90267-5 [67] Delcanho, R.E. and Graff-Radford, S.B. (1993) Chronic paroxysmal hemicrania presenting as toothache. Journal of Orofacial Pain, 7, 300-306. [68] Moncada, E. and Graff-Radford, S.B. (1995) Benign indomethacin-responsive headaches presenting in the orofacial region: Eight case reports. Journal of Orofacial Pain, 9, 276-284. [69] Benoliel, R. and Sharav, Y. (1998) SUNCT syndrome: Case report and literature review. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and Endo- dontology, 85, 158-161. doi:10.1016/S1079-2104(98)90419-X C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJST  R. Balasubramaniam et al. / Open Journal of Stomatology 1 (2011) 92-102 101 [70] Leone, M., Mea, E., Genco, S. and Bussone, G. (2006) Coexistence of TACS and trigeminal neuralgia: Patho- physiological conjectures. Headache, 46, 1565-1570. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00537.x [71] de Siqueira, S.R., Nobrega, J.C., Teixeira, M.J. and de Siqueira, J.T. (2006) SUNCT syndrome associated with temporomandibular disorders: A case report. Cranio, 24, 300-302. [72] Loeser, J.D. (2001) Bonica’s management of pain. Lip- pincott Williams &Wilkins, Philadelphia. [73] Merrill, R.L. and Graff-Radford, S.B. (1992) Trigeminal neuralgia: How to rule out the wrong treatment. The Journal of the American Dental Association, 123, 63-68. [74] Goddard, G. (1992) Case report of trigeminal neuralgia presenting as odontalgia. Cranio, 10, 245-247. [75] Law, A.S. and Lilly, J.P. (1995) Trigeminal neuralgia mimicking odontogenic pain. A report of two cases. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and Endodontology, 80, 96-100. doi:10.1016/S1079-2104(95)80024-7 [76] Donlon, W.C. (1989) Odontalgia mimicking trigeminal neuralgia. Anesthesia Progress, 36, 98-100. [77] Graff-Radford, S.B. and Solberg, W.K. (1993) Is atypical odontalgia a psychological problem? Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, 75, 579-582. doi:10.1016/0030-4220(93)90228-V [78] Clark, G.T. (2006) Persistent orodental pain, atypical odontalgia, and phantom tooth pain: When are they neu- ropathic disorders? Journal of the California Dental As- sociation, 34, 599-609. [79] Marbach, J.J. (1978) Phantom tooth pain. Journal of Endodontics, 4, 362-372. doi:10.1016/S0099-2399(78)80211-8 [80] Marbach, J.J. (1993) Phantom tooth pain: Differential diagnosis and treatment. The New York State Dental Journal, 59, 28-33. [81] Kwan, C.L., Hu, J.W. and Sessle, B.J. (1993) Effects of tooth pulp deafferentation on brainstem neurons of the rat trigeminal subnucleus oralis. Somatosensory and Motor Research, 10, 115-131. doi:10.3109/08990229309028828 [82] Vickers, E.R., Cousins, M.J., Walker, S. and Chisholm, K. (1998) Analysis of 50 patients with atypical odontalgia. A preliminary report on pharmacological procedures for diagnosis and treatment. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and Endodontology, 85, 24-32. doi:10.1016/S1079-2104(98)90393-6 [83] Marbach, J.J. (1996) Orofacial phantom pain: Theory and phenomenology. The Journal of the American Dental As- sociation, 127, 221-229. [84] Solberg, W.K. and Graff-Radford, S.B. (1988) Orodental considerations in facial pain. Seminars in Neurology, 8, 318-323. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1041396 [85] Graff-Radford, S.B. and Solberg, W.K. (1992) Atypical odontalgia. Journal of Craniomandibular Disorders, 6, 260-265. [86] Lilly, J.P. and Law, A.S. (1997) Atypical odontalgia mis- diagnosed as odontogenic pain: A case report and discus- sion of treatment. Journal of Endodontics, 23, 337-339. doi:10.1016/S0099-2399(97)80419-0 [87] Truelove, E. (2004) Management issues of neuropathic trigeminal pain from a dental perspective. Journal of Orofacial Pain, 18, 374-380. [88] Battrum, D.E. and Gutmann, J.L. (1996) Phantom tooth pain: A diagnosis of exclusion. International Endodontic Journal, 29, 190-194. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2591.1996.tb01368.x [89] Reik, L. et al. (1985) Atypical facial pain: A reappraisal. Headache, 25, 30-32. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.1985.hed2501030.x [90] Kreisberg, M.K. (1982) Atypical odontalgia: Differential diagnosis and treatment. The Journal of the American Dental Association, 104, 852-854. [91] Klausner, J.J. (1994) Epidemiology of chronic facial pain: Diagnostic usefulness in patient care. The Journal of the American Dental Association, 125, 1604-1611. [92] Ram, S., Teruel, A., Kumar, S.K. and Clark, G. (2009) Clinical characteristics and diagnosis of atypical odon- talgia: Implications for dentists. The Journal of the American Dental Association, 140, 223-228. [93] Pertes, R.A. and Heir, G.M. (1991) Chronic orofacial pain. A practical approach to differential diagnosis. Den- tal Clinics of North America, 35, 123-140. [94] Rees, R.T. and Harris, M. (1979) Atypical odontalgia. British Journal of Oral Surgery, 16, 212-218. doi:10.1016/0007-117X(79)90027-1 [95] Cuffari, L., Tesseroli de Siqueira, J.T., Nemr, K. and Rapaport, A. (2006) Pain complaint as the first symptom of oral cancer: A descriptive study. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and Endo- dontology, 102, 56-61. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.10.041 [96] Gorsky, M., Epstein, J.B., Oakley, C., Le, N.D., Hay, J. and Stevenson-Moore, P. (2004) Carcinoma of the tongue: A case series analysis of clinical presentation, risk factors, staging, and outcome. Oral Surgery, Ora l M e di ci ne , Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and Endodontology, 98, 546- 552. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2003.12.041 [97] Chaisuparat, R., Coletti, D., Kolokythas, A., Ord, R.A. and Nikitakis, N.G. (2006) Primary intraosseous odonto- genic carcinoma arising in an odontogenic cyst or de novo: A clinicopathologic study of six new cases. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and Endodontology, 101, 194-200. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.03.037 [98] Epstein, J.B. and Jones, C.K. (1993) Presenting signs and symptoms of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, 75, 32-36. doi:10.1016/0030-4220(93)90402-P [99] Reiter, S., Gavish, A., Winocur, E., Emodi-Perlman, A. and Eli, I. (2006) Nasopharyngeal carcinoma mimicking a temporomandibular disorder: A case report. Journal of Orofacial Pain, 20, 74-81. [100] Cohen, S.G. and Quinn, P.D. (1988) Facial trismus and myofascial pain associated with infections and malignant disease. Report of five cases. Oral Surgery, Oral Medi- cine, Oral Pathology, 65, 538-544. doi:10.1016/0030-4220(88)90136-3 [101] Hauser, M.S. and Boraski, J. (1986) Oropharyngeal car- cinoma presenting as an odontogenic infection with tris- mus. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, 61, 330-332. doi:10.1016/0030-4220(86)90411-1 [102] Barrett, A.P. (1984) Gingival lesions in leukemia. A clas- sification. Journal of Periodontology, 55, 585-588. [103] Epstein, J.B., Voss, N.J. and Stevenson-Moore, P. (1984) Maxillofacial manifestations of multiple myeloma. An C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJST  R. Balasubramaniam et al. / Open Journal of Stomatology 1 (2011) 92-102 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. 102 OJST unusual case and review of the literature. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, 57, 267-271. doi:10.1016/0030-4220(84)90182-8 [104] Abraham, P.J., Capobianco, D.J. and Cheshire, W.P. (2003) Facial pain as the presenting symptom of lung carcinoma with normal chest radiograph. Headache, 43, 499-504. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4610.2003.03097.x [105] Capobianco, D.J. (1995) Facial pain as a symptom of nonmetastatic lung cancer. Headache, 35, 581-585. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.1995.hed3510581.x [106] Eross, E.J., Dodick, D.W., Swanson, J.W. and Capobi- anco, D.J. (2003) A review of intractable facial pain sec- ondary to underlying lung neoplasms. Cephalalgia, 23, 2-5. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.2003.00478.x [107] Sarlani, E., Schwartz, A.H., Greenspan, J.D. and Grace, E.G. (2003) Facial pain as first manifestation of lung can- cer: A case of lung cancer-related cluster headache and a review of the literature. Journal of Orofacial Pain, 17, 262-267. [108] Hirshberg, A. and Buchner, A. (1995) Metastatic tumours to the oral region. An overview. European Journal of Cancer Part B Oral Oncology, 31, 355-360. doi:10.1016/0964-1955(95)00031-3 [109] D’Silva, N.J., Summerlin, D.J., Cordell, K.G., Abdelsayed, R.A., Tomich, C.E., Hanks, C.T., et al. (2006) Metastatic tumors in the jaws: A retrospective study of 114 cases. The Journal of the American Dental Association, 137, 1667-1672. [110] Hirshberg, A., Leibovich, P. and Buchner, A. (1993) Me- tastases to the oral mucosa: Analysis of 157 cases. Jour- nal of Oral Pathology and Medicine, 22, 385-390. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0714.1993.tb00128.x [111] Hirshberg, A., Leibovich, P. and Buchner, A. (1994) Me- tastatic tumors to the jawbones: Analysis of 390 cases. Journal of Oral Pathology and Medicine, 23, 337-341. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0714.1994.tb00072.x [112] American Psychiatric Association (1980) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-III). 3rd Edition, Washington DC. [113] Dworkin, S.F. and Burgess, J.A. (1987) Orofacial pain of psychogenic origin: Current concepts and classification. The Journal of the American Dental Association, 115, 565-571.

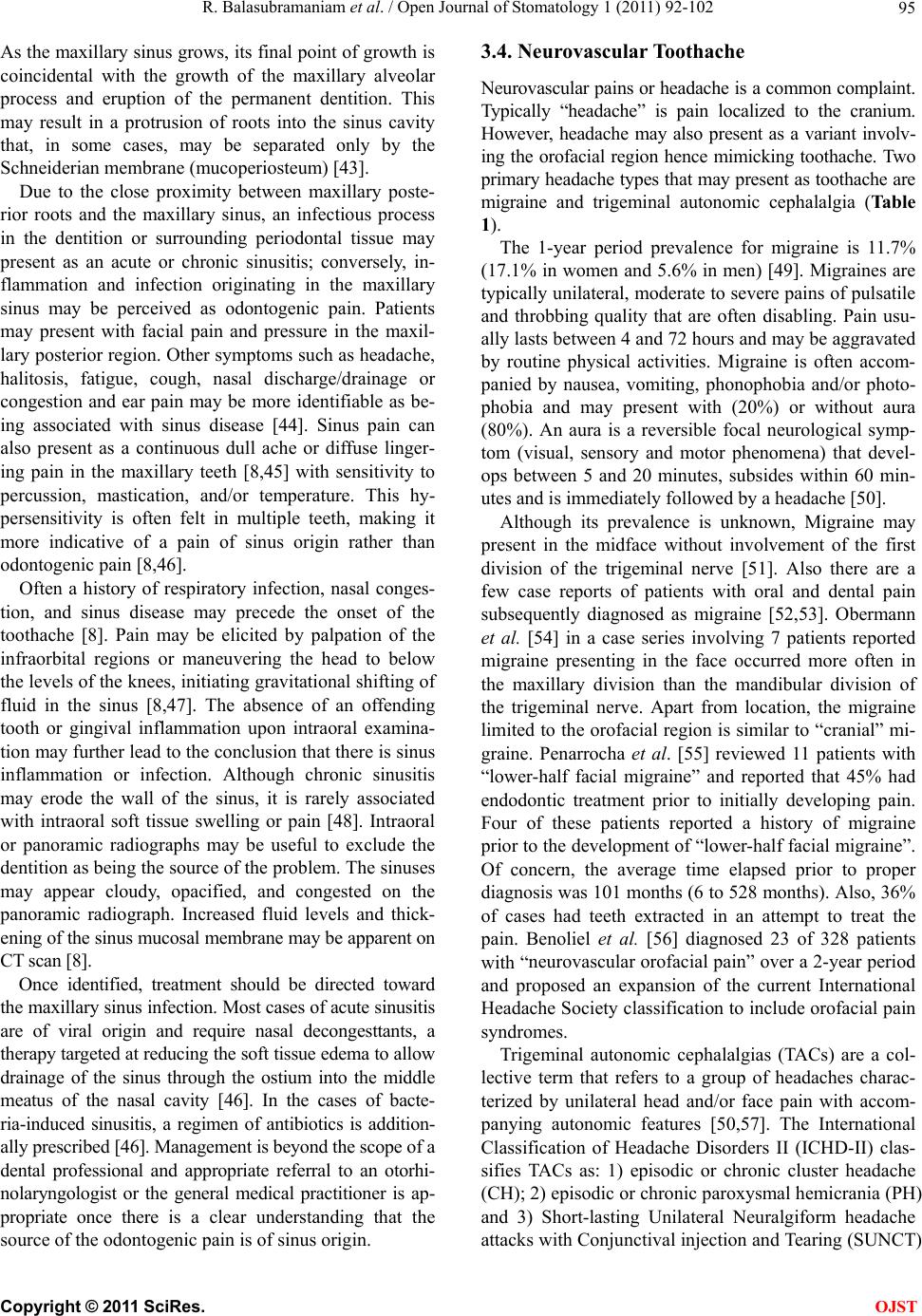

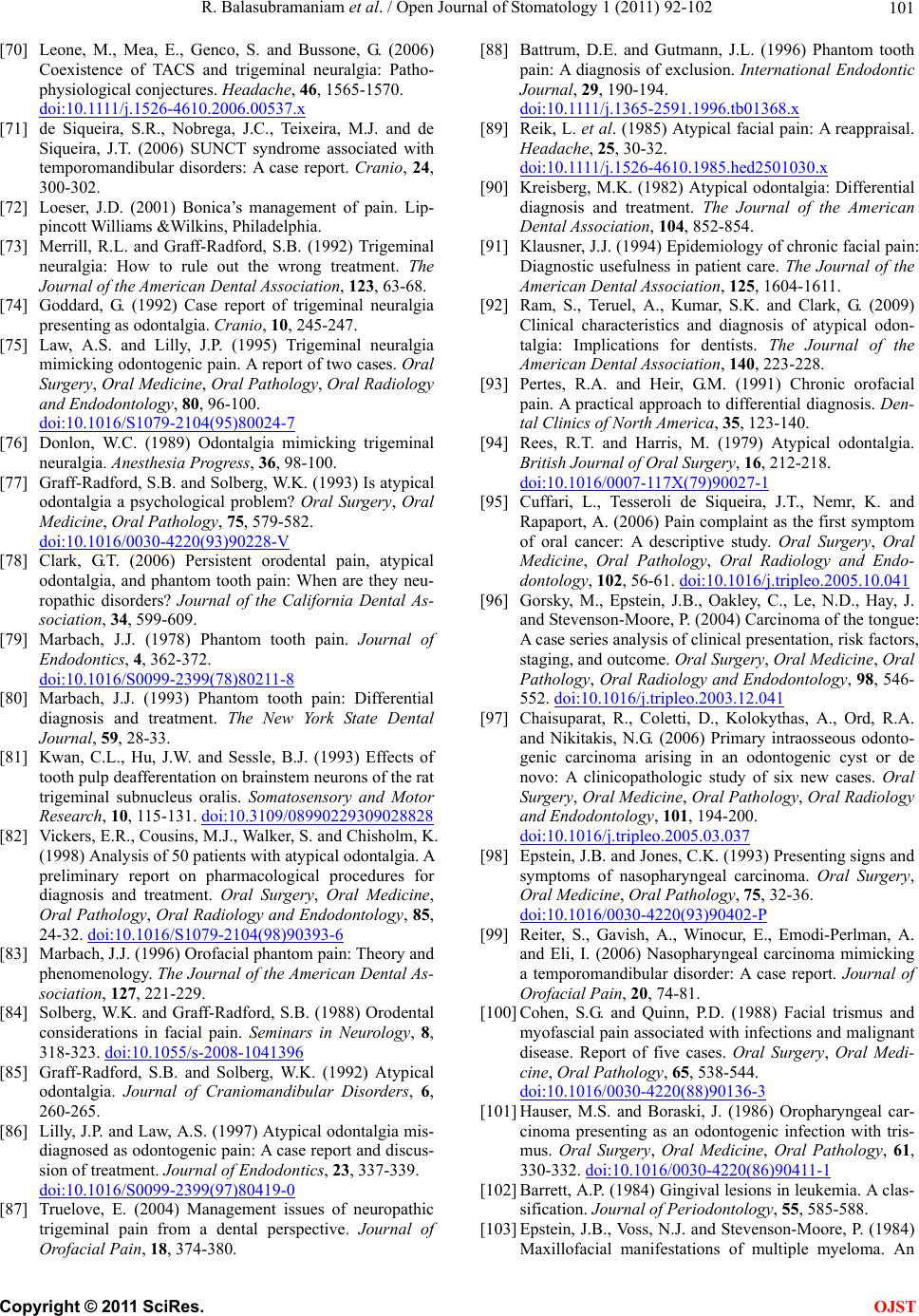

|