Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

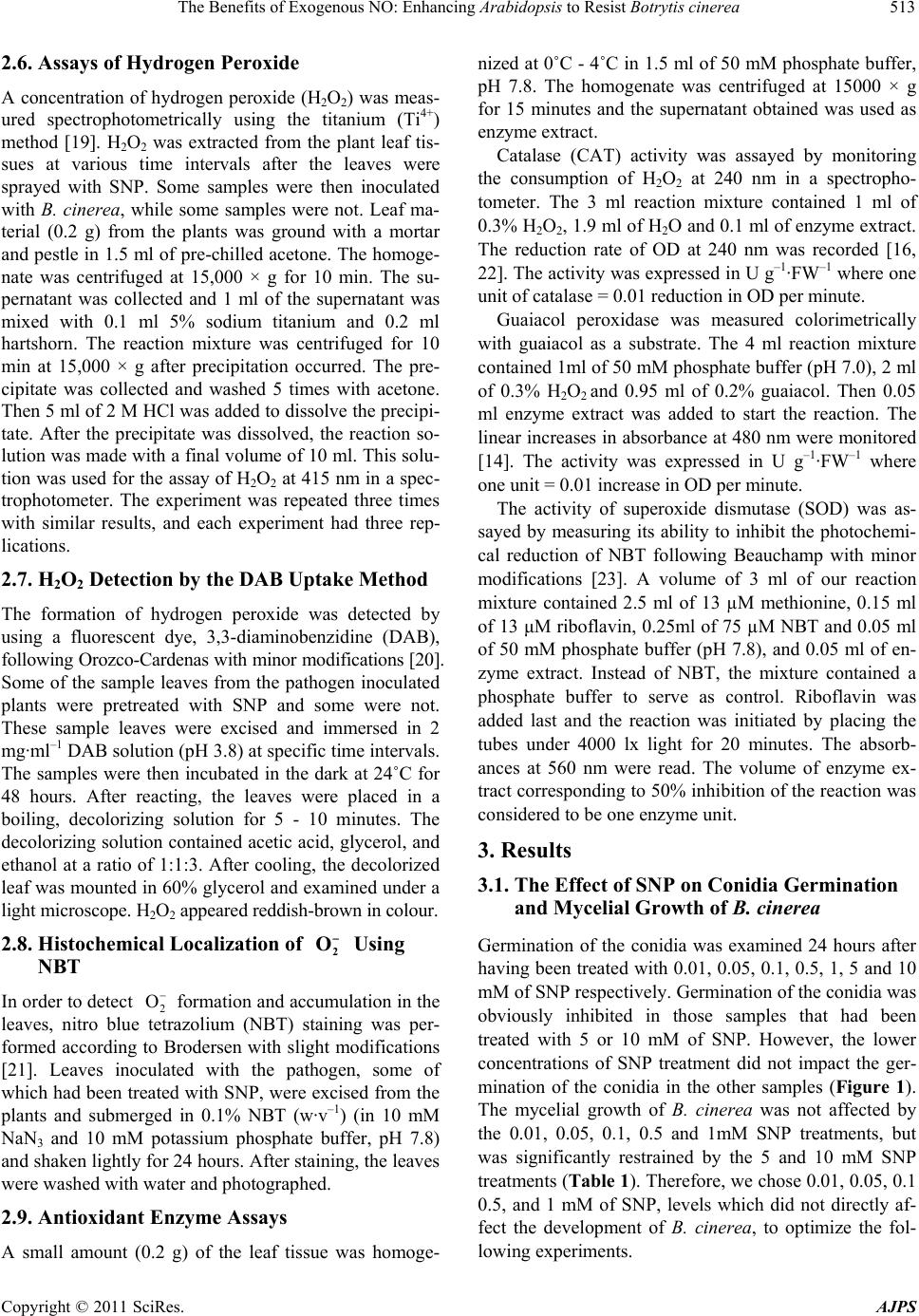

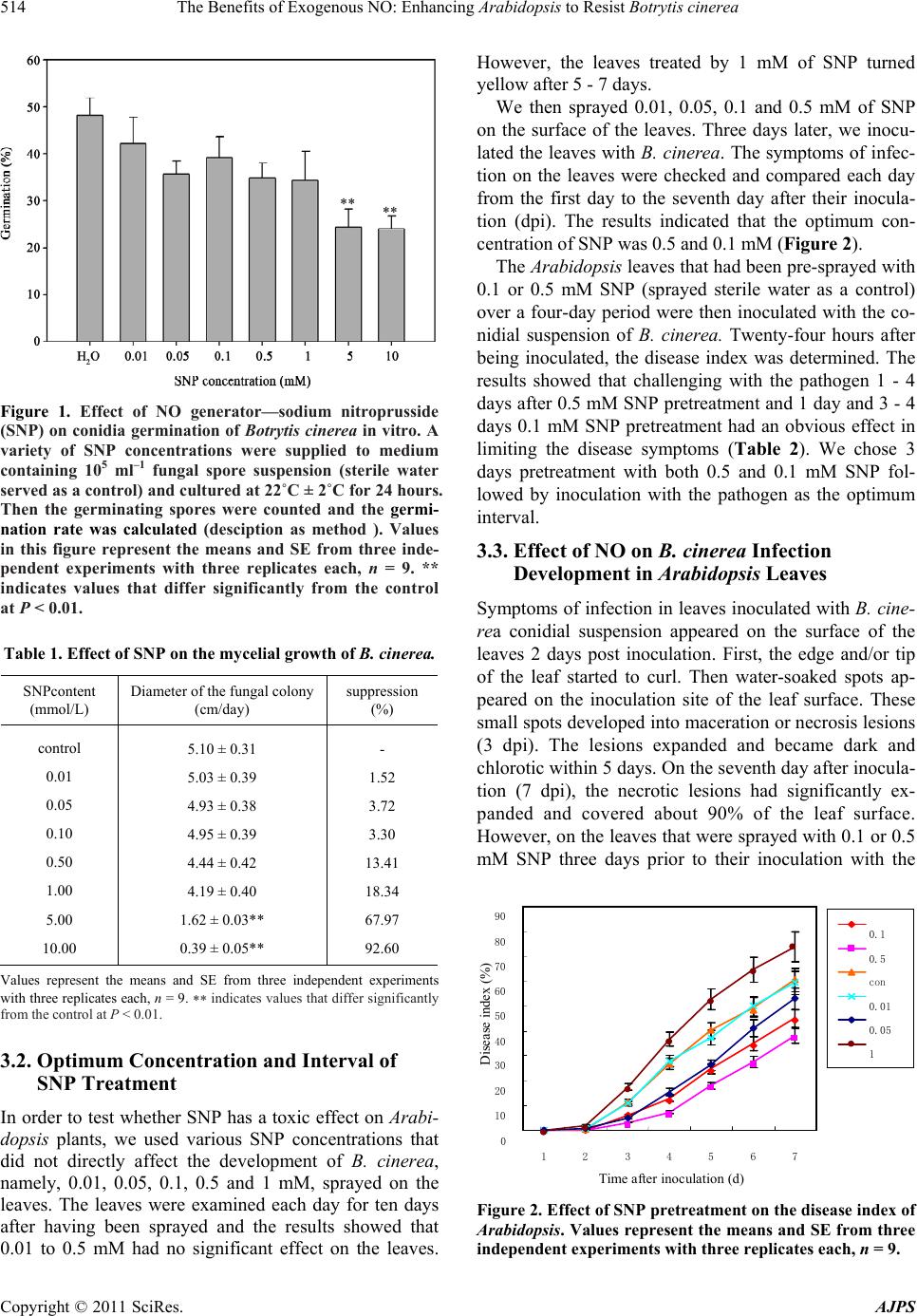

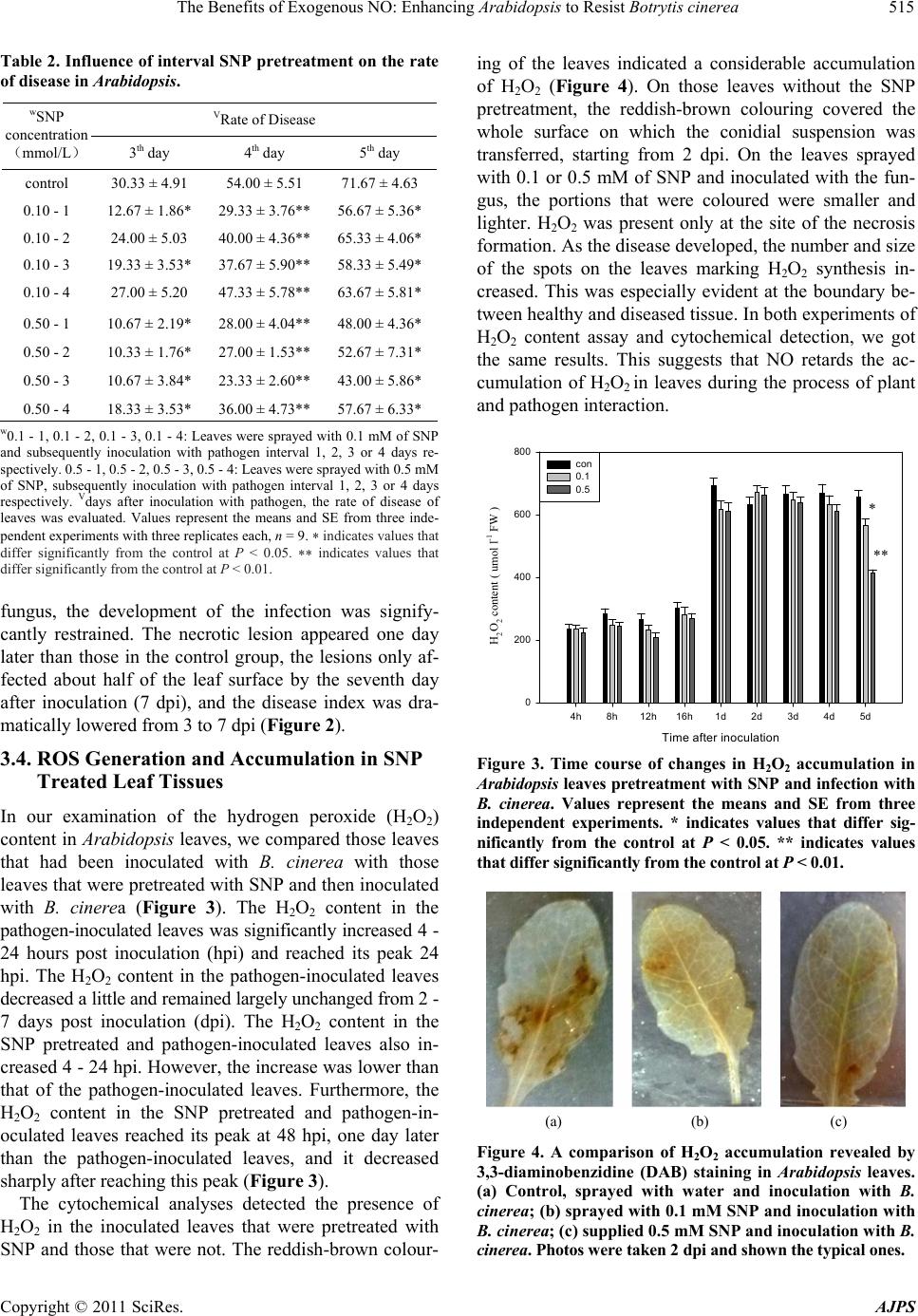

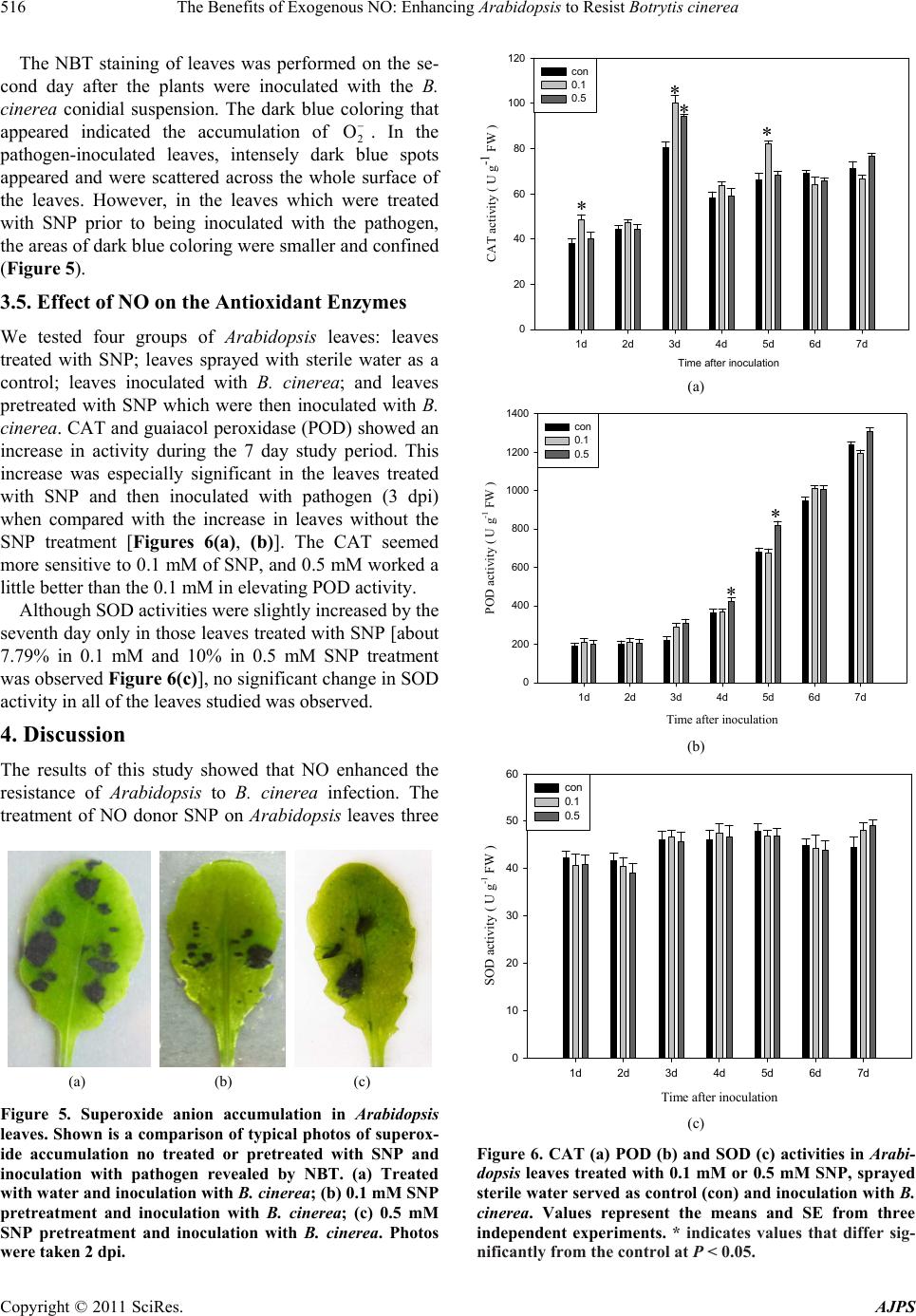

American Journal of Plant Sciences, 2011, 2, 511-519 doi:10.4236/ajps.2011.23060 Published Online September 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ajps) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. AJPS 511 The Benefits of Exogenous NO: Enhancing Arabidopsis to Resist Botrytis cinerea Hongyu Yang1*, Xiaodan Zhao2*, Jia Wu3, Min Hu1, Shaolei Xia2 1College of Life Sciences and Technology, Kunming University, Kunming, China; 2College of Life Sciences, Yunnan Normal University, Kunming, China; 3College of Basic Medical Sciences, Kunming Medical University, Kunming, China. Email: *yanghongyu@kmu.edu.cn Received June 23rd, 2011; revised July 26th, 2011; accepted August 17nd, 2011. ABSTRACT Botrytis cinerea is a necrotrophic fungal pathogen that impacts a wide range of hosts, including Arabidopsis. Pre- treatment with nitric oxide (NO) donor sodium nitroprusside (SNP) on Arabidopsis leaves suppressed Botrytis cinerea infection development. Additionally, in this study the dosage levels of SNP applied to the leaves had no direct, toxic impact on the development of the pathogen. The relationship between NO and reactive oxidant species (ROS) was stud- ied by using both spectrophotometrical methods and staining leaf material with fluorescent dyes, nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT), and with 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB). The results showed that exogenous NO restrained the generation of ROS, especially H2O2, as the pathogen interacted with the Arabidopsis plant. And this inhibition of reactive oxidant burst coincided with delay infection development in NO-supplied leaves. The influence of elevated level of NO on antioxidant enzymes was investigated in this study. The activities of catalase (CAT) and guaiacol peroxidase (POD) were increased to different degrees in both: 1) SNP treated only leaves, and 2) SNP pretreated leaves that were subsequently inoculateted with pathogens. However, the activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) was unchanged in the leaves studied. The decrease in H2O2 content probably resulted from the increase in activities of POD and CAT. Our study suggests that NO might trigger some metabolic reactions, i.e. enhanced enzyme activity that restrains H2O2 which ultimately results in resistance to B. cinerea infection. Keywords: Arabidopsis, Botrytis cinerea, Nitric Oxide, Antioxidant Enzyme, Disease Resistance 1. Introduction Nitric oxide (NO) has been involved in the responses of plants to abiotic and biotic stresses like drought, salt, heat stresses, disease resistance, and apoptosis [1-4]. Most studies that established the role of NO in the defense responses of plants to disease were obtained from ana- lyzing various plant-biotrophic pathogen systems [5]. The data obtained from these studies show that oxidative burst, a transient and rapid accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), is a widespread defense mecha- nism of plants against the attack of pathogens. ROS, in- cluding superoxide (2 O) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), was generated following the recognition of a variety of pathogens and has been identified as a threshold trigger for the hypersensitive response (HR) [6]. The death of plant cells surrounding the pathogenic penetration site caused by HR deprived the pathogen of a nutrient source. This has been considered a successful defense strategy of the plant against biotrophic pathogens [7]. In contrast to biotrophic pathogens, Botrytis cinerea, a necrotrophic pathogen, uses different strategies to avoid incompatibility. This kind of pathogen is able to colonize dead tissue. The pathogen induces the death of host cells in order to facilitate the infection. Thus HR is not an ef- ficient weapon against the infection of necrotrophic pathogens [8]. Although the death of host cells enables necrotrophic pathogens to spread and develop in the host, enhanced ROS generation in the plants was still observed [9,10]. According to Ediich, ROS contribute to over- coming the defense of a host plant against B. cinerea and facilitate infection [11]. This illustrates the different ways that biotrophic and necrotrophic phytopathogenic fungi deal with ROS as they interact with plants. Thus it can be concluded that an efficient response of a plant to necrotrophs like B. cinerea should include the suppres- sion of ROS and the stimulation of the antioxidant sys- tem responsible for the control of the redox state in the cell. This conclusion is supported by a study [12] that showed that radical scavengers were able to reduce the  The Benefits of Exogenous NO: Enhancing Arabidopsis to Resist Botrytis cinerea 512 severity of diseases induced by B. cinerea. Many studies indicate that NO is involved in modify- ing post-infection plant metabolism, often leading to a HR of infected cells. However, only a few of these stud- ies examined the role played by NO in the interaction between the plant and the necrotrophic pathogen [13-15]. Baarlen reported endogenous NO generation during the interaction between lilies and Botrytis elliptica [13]. Floryszak-Wieczorek also found that NO plays a crucial role in the initiation of a fast, defensive response of pe- largonium leaves to a necrotrophic pathogen [15]. The mechanisms of antioxidant action of NO in plant defense reactions were viewed differently. One reckoned that the decrease in H2O2 concentration in NO-supplied tomato leaves was probably due to a direct NO-H2O2 interaction [14]. Another study proposed that in the nonspecific re- sistance of pelargonium to B. cinerea, an early NO burst served as a signal to enhance the accumulation of ascorbic acid and the pool of other ‘fast antioxidants’, and second- dary NO emissions provoked a noncell-death-associated defense, following the rule that the concentration of NO is linked to its action [15]. This present study attempts to elucidate whether NO is involved in the resistance reac- tions of Arabidopsis to B. cinerea infection and to deter- mine how NO inactivates ROS in the defense responses of Arabidopsis plants. 2. Materials and Methods 2.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions The Arabidopsis thaliana plants used in this study were ecotype Columbia. The seeds were sterilized for 1 minute in 95% ethanol and for 5 minutes in 1% bleach, washed 5 times in sterile water, and then pre-germinated on MS salt agar plates at 22˚C ± 2˚C under a light cycle of 12-h light/12-h dark for 1 week. Then the plants were trans- planted into soil and grown at 22˚C ± 2˚C under the same light cycle. 2.2. Pathogen Culture Botrytis cinerea was isolated from infected tomato plants growing in a greenhouse and was maintained in stock culture on potato sucrose agar in the dark at 22˚C ± 2˚C. The B. cinerea spores were cultured in a potato sucrose agar medium without exposure to light at 22˚C ± 2˚C for 8 days. The spores were collected in sterile water and resuspended at 105 spore·ml–1. 2.3. Effect of NO on Conidial Germination and Mycelial Growth of B. cinerea 50 mM of NO donor (sodium nitroprusside, SNP) stock solution was added to the potato sucrose medium con- taining 105 ml–1 fungal spore suspension in order to pro- duce final concentrations of 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 5 and 10 mM [16,17]. The spores were further cultured at 22˚C ± 2˚C in the dark for 24 hours. The medium containing sterile water served as a control. Then the germinating spores were counted under a light microscope [15]. A spore was recognized as a germinating spore when a tube was longer than the spore diameter. Each experiment was replicated three times and the germination rate was cal- culated as follows: rate of spore germination = the num- ber of germinated spore/total number of spore × 100%. In order to study the effect of SNP on the mycelial growth of B. cinerea, we added 50 mM of the SNP stock solution to the potato sucrose agar medium which was cooling after having been sterilized. We added various amounts of the SNP stock to produce final concentrations of 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 5 and 10 mM. 10 ml of the me- dium was poured into a plate. We then placed 10 ml (105 spores/ml spore suspension) of B. cinerea into the center of the medium and the diameter (cm) of the area occu- pied by B. cinerea mycelium was measured after being cultured at 22˚C ± 2˚C in the dark for 3 days. 2.4. Inoculation 5 leaves were selected from one 5-week-old plant and marked. 10 µl drops of B. cinerea conidial suspension (105 ml–1) or sterile water were transferred onto the upper surface of each leaf blade using a 1 ml syringe without a needle. After inoculation, the plants were placed in a growth chamber in the dark at 22˚C ± 2˚C and 100% relative humidity for 24 hours. After 24 hours, the growth chamber conditions were changed to a light cycle of 12-h light/12-h dark and the humidity was maintained at 70%. 2.5. Assessment of Disease Development In order to quantify the severity of the symptoms, indi- vidual leaves were examined each day for ten days after inoculation with the pathogen and rated on a scale of 0 to 5 on the basis of the Murray method with modifications [18] where 0 = no visible symptoms; 1 = very few (less than 10% of leaf area) flecks on leaf area lamina; 2 = chlorotic flecks covered 10% - 25% of leaf area lamina; 3 = 26% - 50% of leaf area shows symptoms; 4 = disease spots covered 51% - 70% of leaf areas; and 5 = most of leaf lamina (71% - 100%) are covered with chlorotic flecks. Plants were assigned a disease index (DI) as fol- lows: DI 100%ijnk in which i = infection class, j = the number of plants scored for that infection class, n = the total number of plants in the replicate, and k = the highest infection class. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. AJPS  The Benefits of Exogenous NO: Enhancing Arabidopsis to Resist Botrytis cinerea513 2.6. Assays of Hydrogen Peroxide A concentration of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was meas- ured spectrophotometrically using the titanium (Ti4+) method [19]. H2O2 was extracted from the plant leaf tis- sues at various time intervals after the leaves were sprayed with SNP. Some samples were then inoculated with B. cinerea, while some samples were not. Leaf ma- terial (0.2 g) from the plants was ground with a mortar and pestle in 1.5 ml of pre-chilled acetone. The homoge- nate was centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 10 min. The su- pernatant was collected and 1 ml of the supernatant was mixed with 0.1 ml 5% sodium titanium and 0.2 ml hartshorn. The reaction mixture was centrifuged for 10 min at 15,000 × g after precipitation occurred. The pre- cipitate was collected and washed 5 times with acetone. Then 5 ml of 2 M HCl was added to dissolve the precipi- tate. After the precipitate was dissolved, the reaction so- lution was made with a final volume of 10 ml. This solu- tion was used for the assay of H2O2 at 415 nm in a spec- trophotometer. The experiment was repeated three times with similar results, and each experiment had three rep- lications. 2.7. H2O2 Detection by the DAB Uptake Method The formation of hydrogen peroxide was detected by using a fluorescent dye, 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB), following Orozco-Cardenas with minor modifications [20]. Some of the sample leaves from the pathogen inoculated plants were pretreated with SNP and some were not. These sample leaves were excised and immersed in 2 mg· ml –1 DAB solution (pH 3.8) at specific time intervals. The samples were then incubated in the dark at 24˚C for 48 hours. After reacting, the leaves were placed in a boiling, decolorizing solution for 5 - 10 minutes. The decolorizing solution contained acetic acid, glycerol, and ethanol at a ratio of 1:1:3. After cooling, the decolorized leaf was mounted in 60% glycerol and examined under a light microscope. H2O2 appeared reddish-brown in colour. 2.8. Histochemical Localization of Using NBT 2 O In order to detect 2 formation and accumulation in the leaves, nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) staining was per- formed according to Brodersen with slight modifications [21]. Leaves inoculated with the pathogen, some of which had been treated with SNP, were excised from the plants and submerged in 0.1% NBT (w·v–1) (in 10 mM NaN3 and 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.8) and shaken lightly for 24 hours. After staining, the leaves were washed with water and photographed. O 2.9. Antioxidant Enzyme Assays A small amount (0.2 g) of the leaf tissue was homoge- nized at 0˚C - 4˚C in 1.5 ml of 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.8. The homogenate was centrifuged at 15000 × g for 15 minutes and the supernatant obtained was used as enzyme extract. Catalase (CAT) activity was assayed by monitoring the consumption of H2O2 at 240 nm in a spectropho- tometer. The 3 ml reaction mixture contained 1 ml of 0.3% H2O2, 1.9 ml of H2O and 0.1 ml of enzyme extract. The reduction rate of OD at 240 nm was recorded [16, 22]. The activity was expressed in U g–1·FW–1 where one unit of catalase = 0.01 reduction in OD per minute. Guaiacol peroxidase was measured colorimetrically with guaiacol as a substrate. The 4 ml reaction mixture contained 1ml of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 2 ml of 0.3% H2O2 and 0.95 ml of 0.2% guaiacol. Then 0.05 ml enzyme extract was added to start the reaction. The linear increases in absorbance at 480 nm were monitored [14]. The activity was expressed in U g–1·FW–1 where one unit = 0.01 increase in OD per minute. The activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) was as- sayed by measuring its ability to inhibit the photochemi- cal reduction of NBT following Beauchamp with minor modifications [23]. A volume of 3 ml of our reaction mixture contained 2.5 ml of 13 µM methionine, 0.15 ml of 13 μM riboflavin, 0.25ml of 75 µM NBT and 0.05 ml of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.8), and 0.05 ml of en- zyme extract. Instead of NBT, the mixture contained a phosphate buffer to serve as control. Riboflavin was added last and the reaction was initiated by placing the tubes under 4000 lx light for 20 minutes. The absorb- ances at 560 nm were read. The volume of enzyme ex- tract corresponding to 50% inhibition of the reaction was considered to be one enzyme unit. 3. Results 3.1. The Effect of SNP on Conidia Germination and Mycelial Growth of B. cinerea Germination of the conidia was examined 24 hours after having been treated with 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 5 and 10 mM of SNP respectively. Germination of the conidia was obviously inhibited in those samples that had been treated with 5 or 10 mM of SNP. However, the lower concentrations of SNP treatment did not impact the ger- mination of the conidia in the other samples (Figure 1). The mycelial growth of B. cinerea was not affected by the 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5 and 1mM SNP treatments, but was significantly restrained by the 5 and 10 mM SNP treatments (Table 1). Therefore, we chose 0.01, 0.05, 0.1 0.5, and 1 mM of SNP, levels which did not directly af- fect the development of B. cinerea, to optimize the fol- lowing experiments. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. AJPS  The Benefits of Exogenous NO: Enhancing Arabidopsis to Resist Botrytis cinerea 514 ** ** Figure 1. Effect of NO generator—sodium nitroprusside (SNP) on conidia germination of Botrytis cinerea in vitro. A variety of SNP concentrations were supplied to medium containing 105 ml–1 fungal spore suspension (sterile water served as a control) and cultured at 22˚C ± 2˚C for 24 hours. Then the germinating spores were counted and the germi- nation rate was calculated (desciption as method ). Values in this figure represent the means and SE from three inde- pendent experiments with three replicates each, n = 9. ** indicates values that differ significantly from the control at P < 0.01. Table 1. Effect of SNP on the mycelial growth of B. cinerea. SNPcontent (mmol/L) Diameter of the fungal colony (cm/day) suppression (%) control 0.01 0.05 0.10 0.50 1.00 5.00 10.00 5.10 ± 0.31 5.03 ± 0.39 4.93 ± 0.38 4.95 ± 0.39 4.44 ± 0.42 4.19 ± 0.40 1.62 ± 0.03** 0.39 ± 0.05** - 1.52 3.72 3.30 13.41 18.34 67.97 92.60 Values represent the means and SE from three independent experiments with three replicates each, n = 9. indicates values that differ significantly from the control at P < 0.01. 3.2. Optimum Concentration and Interval of SNP Treatment In order to test whether SNP has a toxic effect on Arabi- dopsis plants, we used various SNP concentrations that did not directly affect the development of B. cinerea, namely, 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5 and 1 mM, sprayed on the leaves. The leaves were examined each day for ten days after having been sprayed and the results showed that 0.01 to 0.5 mM had no significant effect on the leaves. However, the leaves treated by 1 mM of SNP turned yellow after 5 - 7 days. We then sprayed 0.01, 0.05, 0.1 and 0.5 mM of SNP on the surface of the leaves. Three days later, we inocu- lated the leaves with B. cinerea. The symptoms of infec- tion on the leaves were checked and compared each day from the first day to the seventh day after their inocula- tion (dpi). The results indicated that the optimum con- centration of SNP was 0.5 and 0.1 mM (Figure 2). The Arab idopsis leaves that had been pre-sprayed with 0.1 or 0.5 mM SNP (sprayed sterile water as a control) over a four-day period were then inoculated with the co- nidial suspension of B. cinerea. Twenty-four hours after being inoculated, the disease index was determined. The results showed that challenging with the pathogen 1 - 4 days after 0.5 mM SNP pretreatment and 1 day and 3 - 4 days 0.1 mM SNP pretreatment had an obvious effect in limiting the disease symptoms (Table 2). We chose 3 days pretreatment with both 0.5 and 0.1 mM SNP fol- lowed by inoculation with the pathogen as the optimum interval. 3.3. Effect of NO on B. cinerea Infection Development in Arabidopsis Leaves Symptoms of infection in leaves inoculated with B. cine- rea conidial suspension appeared on the surface of the leaves 2 days post inoculation. First, the edge and/or tip of the leaf started to curl. Then water-soaked spots ap- peared on the inoculation site of the leaf surface. These small spots developed into maceration or necrosis lesions (3 dpi). The lesions expanded and became dark and chlorotic within 5 days. On the seventh day after inocula- tion (7 dpi), the necrotic lesions had significantly ex- panded and covered about 90% of the leaf surface. However, on the leaves that were sprayed with 0.1 or 0.5 mM SNP three days prior to their inoculation with the 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 1 23 4 5 6 7 Time after inoculation (d) Disease index (%) 0.1 0.5 con 0.01 0.05 1 Figure 2. Effect of SNP pretreatment on the disease index of Arabidopsis. Values represent the means and SE from three independ ent experiments with three replicate s each, n = 9. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. AJPS  The Benefits of Exogenous NO: Enhancing Arabidopsis to Resist Botrytis cinerea515 Table 2. Influence of interval SNP pretreatment on the rate of disease in Arabidopsis. VRate of Disease wSNP concentration (mmol/L) 3th day 4th day 5th day control 30.33 ± 4.91 54.00 ± 5.51 71.67 ± 4.63 0.10 - 1 12.67 ± 1.86* 29.33 ± 3.76** 56.67 ± 5.36* 0.10 - 2 24.00 ± 5.03 40.00 ± 4.36** 65.33 ± 4.06* 0.10 - 3 19.33 ± 3.53* 37.67 ± 5.90** 58.33 ± 5.49* 0.10 - 4 27.00 ± 5.20 47.33 ± 5.78** 63.67 ± 5.81* 0.50 - 1 0.50 - 2 0.50 - 3 0.50 - 4 10.67 ± 2.19* 10.33 ± 1.76* 10.67 ± 3.84* 18.33 ± 3.53* 28.00 ± 4.04** 27.00 ± 1.53** 23.33 ± 2.60** 36.00 ± 4.73** 48.00 ± 4.36* 52.67 ± 7.31* 43.00 ± 5.86* 57.67 ± 6.33* w0.1 - 1, 0.1 - 2, 0.1 - 3, 0.1 - 4: Leaves were sprayed with 0.1 mM of SNP and subsequently inoculation with pathogen interval 1, 2, 3 or 4 days re- spectively. 0.5 - 1, 0.5 - 2, 0.5 - 3, 0.5 - 4: Leaves were sprayed with 0.5 mM of SNP, subsequently inoculation with pathogen interval 1, 2, 3 or 4 days respectively. Vdays after inoculation with pathogen, the rate of disease of leaves was evaluated. Values represent the means and SE from three inde- pendent experiments with three replicates each, n = 9. indicates values that differ significantly from the control at P < 0.05. indicates values that differ significantly from the control at P < 0.01. fungus, the development of the infection was signify- cantly restrained. The necrotic lesion appeared one day later than those in the control group, the lesions only af- fected about half of the leaf surface by the seventh day after inoculation (7 dpi), and the disease index was dra- matically lowered from 3 to 7 dpi (Figure 2). 3.4. ROS Generation and Accumulation in SNP Treated Leaf Tissues In our examination of the hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) content in Arabidopsis leaves, we compared those leaves that had been inoculated with B. cinerea with those leaves that were pretreated with SNP and then inoculated with B. cinerea (Figure 3). The H2O2 content in the pathogen-inoculated leaves was significantly increased 4 - 24 hours post inoculation (hpi) and reached its peak 24 hpi. The H2O2 content in the pathogen-inoculated leaves decreased a little and remained largely unchanged from 2 - 7 days post inoculation (dpi). The H2O2 content in the SNP pretreated and pathogen-inoculated leaves also in- creased 4 - 24 hpi. However, the increase was lower than that of the pathogen-inoculated leaves. Furthermore, the H2O2 content in the SNP pretreated and pathogen-in- oculated leaves reached its peak at 48 hpi, one day later than the pathogen-inoculated leaves, and it decreased sharply after reaching this peak (Figure 3). The cytochemical analyses detected the presence of H2O2 in the inoculated leaves that were pretreated with SNP and those that were not. The reddish-brown colour- ing of the leaves indicated a considerable accumulation of H2O2 (Figure 4). On those leaves without the SNP pretreatment, the reddish-brown colouring covered the whole surface on which the conidial suspension was transferred, starting from 2 dpi. On the leaves sprayed with 0.1 or 0.5 mM of SNP and inoculated with the fun- gus, the portions that were coloured were smaller and lighter. H2O2 was present only at the site of the necrosis formation. As the disease developed, the number and size of the spots on the leaves marking H2O2 synthesis in- creased. This was especially evident at the boundary be- tween healthy and diseased tissue. In both experiments of H2O2 content assay and cytochemical detection, we got the same results. This suggests that NO retards the ac- cumulation of H2O2 in leaves during the process of plant and pathogen interaction. Time after inoculation 4h 8h12h16h1d 2d 3d 4d 5d H2O2 content ( umol l-1 FW ) 0 200 400 600 800 con 0.1 0.5 * ** Figure 3. Time course of changes in H2O2 accumulation in Arabidopsis leaves pretreatment with SNP and infection with B. cinerea. Values represent the means and SE from three independent experiments. * indicates values that differ sig- nificantly from the control at P < 0.05. ** indicates values that differ significantly from the control at P < 0.01. (a) (b) (c) Figure 4. A comparison of H2O2 accumulation revealed by 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining in Arabidopsis leaves. (a) Control, sprayed with water and inoculation with B. cinerea; (b) sprayed with 0.1 mM SNP and inoculation with B. cinerea; (c) supplied 0.5 mM SNP and inoculation with B. cinerea. Photos were taken 2 dpi and shown the typ ical on es. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. AJPS  The Benefits of Exogenous NO: Enhancing Arabidopsis to Resist Botrytis cinerea 516 The NBT staining of leaves was performed on the se- cond day after the plants were inoculated with the B. cinerea conidial suspension. The dark blue coloring that appeared indicated the accumulation of 2. In the pathogen-inoculated leaves, intensely dark blue spots appeared and were scattered across the whole surface of the leaves. However, in the leaves which were treated with SNP prior to being inoculated with the pathogen, the areas of dark blue coloring were smaller and confined (Figure 5). O 3.5. Effect of NO on the Antioxidant Enzymes We tested four groups of Arabidopsis leaves: leaves treated with SNP; leaves sprayed with sterile water as a control; leaves inoculated with B. cinerea; and leaves pretreated with SNP which were then inoculated with B. cinerea. CAT and guaiacol peroxidase (POD) showed an increase in activity during the 7 day study period. This increase was especially significant in the leaves treated with SNP and then inoculated with pathogen (3 dpi) when compared with the increase in leaves without the SNP treatment [Figures 6(a), (b)]. The CAT seemed more sensitive to 0.1 mM of SNP, and 0.5 mM worked a little better than the 0.1 mM in elevating POD activity. Although SOD activities were slightly increased by the seventh day only in those leaves treated with SNP [about 7.79% in 0.1 mM and 10% in 0.5 mM SNP treatment was observed Figure 6(c)], no significant change in SOD activity in all of the leaves studied was observed. 4. Discussion The results of this study showed that NO enhanced the resistance of Arabidopsis to B. cinerea infection. The treatment of NO donor SNP on Arabidopsis leaves three (a) (b) (c) Figure 5. Superoxide anion accumulation in Arabidopsis leaves. Shown is a comparison of typical photos of superox- ide accumulation no treated or pretreated with SNP and inoculation with pathogen revealed by NBT. (a) Treated with water and inoculation w ith B. cinerea; (b) 0.1 mM SNP pretreatment and inoculation with B. cinerea; (c) 0.5 mM SNP pretreatment and inoculation with B. cinerea. Photos were taken 2 dpi. 1d 2d 3d 4d 5d 6d 7d CAT activity ( U g- 1 FW ) 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 con 0.1 0.5 Time after inoculation (a) Time after inoculation 1d 2d 3d4d5d 6d7d POD activity ( U g-1 FW ) 0 200 400 600 800 1000 1200 1400 con 0.1 0.5 (b) Time after inoculation 1d 2d 3d 4d 5d 6d 7d SOD activity ( U g-1 FW ) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 con 0.1 0.5 (c) Figure 6. CAT (a) POD (b) and SOD (c) activities in Arabi- dopsis leaves treated with 0.1 mM or 0.5 mM SNP, sprayed sterile water served as control (con) and inoculation with B. cinerea. Values represent the means and SE from three independent experiments. * indicates values that differ sig- nificantly from the control at P < 0.05. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. AJPS  The Benefits of Exogenous NO: Enhancing Arabidopsis to Resist Botrytis cinerea517 days prior to inoculation with fungus significantly ham- pered the development of symptoms of disease. The ef- fective concentration (0.1 and 0.5 mM) of SNP did not have any direct role in reducing pathogen viability or inhibiting their development (Figure 1 and Table 1). This suggests that NO induces the intrinsic resistance of Arabidopsis plants to B. cinerea. Production of ROS during oxidative burst is one of the earliest and most effective defensive responses of plants [24-28]. The process of ROS generation in plant leaves during the interaction between Arabidopsis and B. cine- rea has been previously elucidated [8,9,11,12,29,30]. B. cinerea can induce an oxidative burst and hypersensitive cell death in Arabidopsis. Additionally, levels of ROS, especially H2O2 levels during hypersensitive response, correlate positively with B. cinerea growth in plant tis- sues [8,31]. In this study we have examined the genera- tion of ROS and the actions of antioxidant enzymes in an attempt to determine their roles in the NO treatment in- duced resistance reactions of Arabidopsis plants to B. cinerea infection. The results show that the concentration of H2O2 in- creased rapidly during the early stage of pathogen infec- tion both in plant leaves treated with SNP three days prior to inoculation with the pathogen and in those leaves not treated prior to inoculation. However, the time when the H2O2 concentration reached its peak was different between the two groups (those leaves treated with SNP and those not treated). The time of maximal H2O2 con- centration was delayed one day in the leaves that were treated with SNP (Figure 3). H2O2 production in the SNP pretreated and pathogen-inoculated plants was lower than in the pathogen inoculated and SNP non-treated plants during the entire study period. Similar results were ob- tained from the histochemical determination of H2O2 and superoxide, which showed less accumulation of H2O2 and superoxide in SNP pretreated and pathogen-inocu- lated leaves. In conclusion, it is evident that the lower levels of H2O2 concentration induced by NO treatment in Arabidopsis plants enhanced their resistance to infection caused by B. cinerea. Thus, there appears to be a correla- tion between the induction and accumulation of H2O2 in host plants during compatible interactions with B. cine- rea [8,9,11,12]. In many plant-pathogen systems, H2O2 also plays a prominent role in host cell death during in- fection by necrotrophic pathogens, and in oxidative burst [32]. But some studies noted that pretreatment with o- hydroxyethylorutin enhanced H2O2 generation in tomato leaves during the interaction of the tomato plants with B. cinerea. This higher level of H2O2 may act as a direct antimicrobial agent limiting the germination of pathogen spores, and enhancing the tomato plant’s resistance [17]. A dual role for H2O2 in the process of plant-pathogen interaction is either protective or toxic, probably depend- ing on its concentration and the plant species. Early studies revealed that secretion of alcohol oxi- dases by B. cinerea can release H2O2 into the extracellular medium [33]. Additionally, superoxide dismutase (SOD), which is an H2O2-generating enzyme of B. cinerea, con- tributed to pathogenesis during the interaction of the pathogen with beans [34]. H2O2 could be produced by the fungus in order to enable Botrytis to colonize plant tis- sues [35]. However, Rij indicated that toxic levels of extracellular H2O2 were likely to be more harmful to the fungus than the plant [36]. Thus, it would be much more advantageous for the fungus if the H2O2 generation were to take place inside the plant cell compartment and thus be separated from sensitive fungal hyphae. A recent study showed that diffuse H2O2 probe signals were not observed in lily cells in the presence of Botrytis elliptica (a necrotrophic pathogen) mycelium, demonstrating that intracellular H2O2 was exclusively produced by live plant cells [13]. Although the sources of H2O2 still need to be clarified during the process of plant-necrotrophic inter- action, the levels of ROS, mostly H2O2, in plants are in- creased and the accumulation of these compounds is concomitant with disease progression and Arabidopsis cell death. A significant reduction in H2O2 and superox- ide content and/or the delay of the advent of the highest H2O2 content in Arabidopsis leaves as a result of NO donor treatment may suggest that NO can act as an anti- oxidant that inhibits H2O2 from signaling pathways that lead to cell death. Data about the relationship between NO and antioxi- dant enzymes are also a source of controversy. SOD, CAT, ascorbate (APX) and guaiacol peroxidases (POD) have been shown to be inhibited by NO in tobacco and zinnia plants [16,37]. But different results also have been observed. The activities of SOD, CAT and APX in to- mato cells remain unchanged in NO donor SNP pre- treated plants [17]. Our results indicated that the active- ity of the enzyme (SOD) generating H2O2 in Arabidopsis plant cells remained unchanged in the plants studied. However, the activity of CAT and guaiacol peroxidase (POD), enzymes that reduce H2O2, was significantly in- creased in Arabidopsis leaves through the treatment of SNP prior to inoculation with the pathogen. This sug- gests that the decrease in H2O2 content is due to the work of the antioxidant enzyme system. It also indicates that NO may play a role through regulating metabolic activity in the protection of cells against the destructive action of ROS. In the present study, we found that in the leaves pretreated with SNP, POD activity rapidly and signify- cantly increased 24 hours after the leaves were inocu- lated with B. cinerea and this activity kept increasing during the entire study period (Figure 6(b)). Tiedemann Copyright © 2011 SciRes. AJPS  The Benefits of Exogenous NO: Enhancing Arabidopsis to Resist Botrytis cinerea 518 reported that B. cinerea suppressed the activity of plant peroxidase in bean leaf discs [9]. His findings suggested that peroxidases play a role as scavengers of harmful H2O2 in plant resistance. POD can not only scavenge H2O2 in the initial stage of infection, but can also be ac- tive in further resistance reactions (e.g., the cross-linking of cell wall proteins and the polymerization of lignin pre- cursors), thus providing protection from pathogen inva- sion. Our results offer evidence that NO might stimilate antioxidant enzymes which destroy ROS in plant cells. This triggers subsequent defense reactions in the plant and enhances the resistance of the Arabidopsis plant to infection by B. cinerea. 5. Conclusions 1) Low concentrations (0.1 and 0.5 mM) of nitric oxide donor sodium nitroprusside (SNP) had neither a direct, toxic effect on conidial germination and mycelial growth of B. cinerea, nor a toxic impact on development of Arabipdopsis. But high concentrations of SNP, such as 5 mM and 10 mM, were harmful to both pathogen and plant. 2) Applying 0.1 and 0.5 mM SNP to Arabidopaia leaves could induce disease resistance of Arabidopsis to B. cinerea. The exogenous NO could delay ROS burst and restrain the rapid accumlation of H2O2 and 2 O in plants thereby delaying progression of disease. 3) The biochemical mechanism of ROS reduction might be related to exogenous NO stimulation of the an- tioxidase POD and CAT activities. The changes of SOD (generating H2O2) activities were not obvious in plants which were pretreated with SNP and subsequently in- oculated with a pathogen. Therefore NO might play an important role in scavenging H2O2 and enhancing resis- tance of Arabidopsis to B cinerea. 6. Acknowledgements This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 30860121) and the Open Program of State Key Laboratory of Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, China Agriculture University (PP- B08010). REFERENCES [1] J. Durner and D. F. Klessig, “Nitric Oxide as a Signal in Plants,” Current Opinion in Plant Biology, Vol. 2, No. 5, 1999, pp. 369-374. [2] M. Delledonne, Y. Xia, R. A. Dixon and C. Lamb, “Nitric Oxide Functions as a Signal in Plant Disease Resistance,” Nature, Vol. 394, No. 6, 1998, pp. 585-588. [3] M. Arasimowicz and W. J. Floryszak, “Nitric Oxide as a Bioactive Signalling Molecule in Plant Stress Responses,” Plant Science, Vol. 172, No. 5, 2007, pp. 876-887. [4] M. G. Zhao, Q. Y. Tian and W. H. Zhang, “Nitric Oxide Synthase-Dependent Nitric Oxide Production Is Associ- ated with Salt Tolerance in Arabidopsis,” Plant Physiol- ogy, Vol. 144, No. 1, 2007, pp. 206-217. [5] M. Delledonne, “NO News Is Good News for Plants,” Current Option in Plant Biology, Vol. 8, No. 4, 2005, pp. 390-396. [6] P. Wojtaszek, “Oxidative Burst, an Early Plant Response to Pathogen Infection,” Biochemical Journal, Vol. 322, No. 3, 1997, pp. 681-692. [7] D. G. Gilchrist, “Programmed Cell Death in Plant Disease, the Purpose and Promise of Cellular Suicide,” Annual Review of Phytopathology, Vol. 36, 1998, pp. 393-414. [8] E. M. Govrin and A. Levine, “The Hypersensitive Re- sponse Facilitates Plant Infection by the Necrotrophic Pathogen Botrytis cinerea,” Current Biology, Vol. 10, No. 13, 2000, pp. 751-757. [9] A. V. Tiedemann, “Evidence for a Primary Role of Active Oxygen Species in Induction of Host Cell Death during Infection of Bean Leaves with Botrytis cinerea,” Physio- logical and Molecular Plant Pathology, Vol. 50, No. 3, 1997, pp. 151-166. [10] A. J. Able, “Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in the Re- sponse of Barley to Necrotrophic Pathogens,” Proto- plasma, Vol. 221, No. 1-2, 2003, pp. 137-143. [11] W. Edlich, G. Lorenz, H. Lyr, E. Nega and E. H. Pommer, “New Aspects on the Infection Mechanism of Botrytis cinerea Pers,” European Journal of Plant Pathology, Vol. 95, Supplement 1, 1989, pp. 53-62. [12] Y. Elad, “The Use of Antioxidants (Free Radical Scav- engers) to Control Grey Mold (Botrytis cinerea) and White Mold (Sclerotinia sclerotiorum) in Various Crops,” Plant Pathology, Vol. 41, No. 4, 1992, pp. 417-426. [13] P. V. Barrlen, M. Staats and J. A. L. V. Kan, “Induction of Programmed Cell Death in Lily by the Fungal Patho- gen Botrytis elliptica,” Molecular Plant Pathology, Vol. 5, No. 6, 2004, pp. 559-574. [14] U. Małolepsza and H. Urbanek, “The Oxidants and Anti- oxidant Enzymes in Tomato Leaves Treated with O-Hy- droxyethylorutin and Infected with Botrytis cinerea,” Euro- pean Journal of Plant Pathology, Vol. 106, No. 7, 2000, pp. 657-665. [15] J. Floryszak-Wieczorek, M. Arasimowicz, G. Milczarek, H. Jelen and H. Jackowiak, “Only an Early Nitric Oxide Burst and the Following Wave of Secondary Nitric Oxide Generation Enhanced Effective Defence Responses of Pelargonium to a Necrotrophic Pathogen,” New Phytolo- gist, Vol. 175, No. 4, 2007, pp. 718-730. [16] D. Clark, J. Durner, D. A. Navarre and D. F. Klessig, “Nitric Oxide Inhibition of Tobacco Catalase and Ascor- bate Peroxidase,” Molecular Plant Microbe Interaction, Vol. 13, No. 12, 2000, pp. 1380-1384. [17] U. Małolepsza and S. Rózalska, “Nitric Oxide and Hydro- gen Peroxide in Tomato Resistance, Nitric Oxide Modu- lates Hydrogen Peroxide Level in O-Hydroxyethylorutin- Induced Resistance to Botrytis cinerea in Tomato,” Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, Vol. 43, No. 6, 2005, pp. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. AJPS  The Benefits of Exogenous NO: Enhancing Arabidopsis to Resist Botrytis cinerea Copyright © 2011 SciRes. AJPS 519 623-635. [18] S. L. Murray, C. Thomson, A. Chini, N. D. Read and G. J. Loake, “Characterization of a Novel, Defense-Related Arabidopsis Mutant, cir1, Isolated by Luciferase Imagin,” Molecular Plant―Microbe Interactions, Vol. 15, No. 6, 2002, pp. 57-566. [19] M. Becana, P. Aparicio-Tejo, J. J. Irigoyen and D. M. Sanchez, “Some Enzymes of Hydrogen Peroxide Metabo- lism in Leaves and Root Nodules of Medicago sativa,” Plant Physiology, Vol. 82, No. 4, 1986, pp. 1169-1171. [20] M. L. Orozco-Cardenas and C. A. Ryan, “Hydrogen Pero- xide Is Generated Systemically in Plant Leaves by Wound- ing and Systemin via the Octadecanoid Pathway,” Pro- ceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in the USA, Vol. 96, No. 11, 1999, pp. 6553-6557. [21] P. Brodersen, M. Petersen, H. M. Pike, B. Olszak, S. Skov, N. dum, L. B. Jørgensen, R. E. Brown and J. Mundy, “Knockout of Arabidopsis ACCELERATED-CELL-DEA- TH11 Encoding a Sphingosine Transfer Protein Causes Activation of Programmed Cell Death and Defense,” Genes & Development, Vol. 16, No. 4, 2002, pp. 490- 502. [22] I. Cakmak and H. Marschner, “Magnesium Deficiency and High Light Intensity Enhance Activities of Superox- ide Dismutase, Ascorbate Peroxidase, and Glutathione Rreducatse in Bean Leaves,” Plant Physiology, Vol. 98, No. 4, 1992, pp. 1222-1227. [23] C. Beauchamp and I. Fridovich, “Superoxide Dismutase, Improved Assays and Assay Applicable to Acrylamide Gels,” Analytical Biochemistry, Vol. 44, No. 1, 1971, pp. 276-287. [24] N. Doke, “Involvement of Superoxide Generation in the Hypersensitive Response of Potato Tuber Tissues to In- fection with an Incompatible Race of Phytophthora in- festans and to Hyphal Wall Components,” Physiological Plant Pathology, Vol. 23, No. 3, 1983, pp. 345-357. [25] M. W. Sutherland, “The Generation of Oxygen Radicals during Host Plant Responses to Infection,” Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology, Vol. 39, No. 2, 1991, pp. 79-93. [26] M. C. Mehdy, “Active Oxygen Species in Plant Defense against Pathogens,” Plant Physiology, Vol. 105, No. 2, 1994, pp. 467-472. [27] M. C. Mehdy, Y. K. Sharma, K. Sathasivan and N. W. Bays, “The Role of Activated Oxygen Species in Plant Disease Resistance,” Physiology Plant, Vol. 98, 1996, pp. 365-374. [28] R. Tenhaken, A. Levine, L. F. Brisson, R. A. Dixon and C. Lamb, “Function of the Oxidative Burst in Hypersen- sitive Disease Resistance,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, Vol. 92, No. 10, 1995, pp. 4158-4163. [29] T. Mengiste, X. Chen, J. Salmeron and R. Dietrich, “The BOTRYTIS SUSCEPTIBLE1 Gene Encodes an R2R3MYB Transcription Factor Protein That Is Required for Biotic and Abiotic Stress Responses in Arabidopsis,” Plant Cell, Vol. 15, No. 11, 2003, pp. 2551-2565. [30] P. Veronese, X. Chen, B. Bluhm, J. Salmeron, R. Dietrich and T. Mengiste, “The BOS Loci of Arabidopsis Are Re- quired for Resistance to Botrytis cinerea Infection,” The Plant Journal, Vol. 40, No. 4, 2004, pp. 558-574. [31] C. H. Unger, S. Kleta, G. Janell and A. Tiedemann, “Sup- pression of the Defence-Related Oxidative Burst in Leaf Tissue and Bean Suspension Cells by the Necrotrophic Pathogen Botrytis cinerea,” Journal of Phytopathology, Vol. 153, No. 1, 2005, pp. 15-26. [32] Y. Tada, T. Mori, T. Shinogi, N. Yao, S. Takahashi, S. Betsuyaku, M. Sakamoto, P. Park, H. Nakayashiki, Y. Tosa and S. Mayama, “Nitric Oxide and Reactive Oxygen Species Do Not Elicit Hypersensitive Cell Death but In- duce Apoptosis in the Adjacent Cells during the Defense Response of Oats,” Molecular Plant―Microbe Interact, Vol. 17, No. 3, 2004, pp. 245-253. [33] R. P. Pratt, A. E. Brown and P. C. Mercer, “A Role for Hydrogen Peroxide in Degradation of Flax Fibre by Bo- trytis cinerea,” Transactions of the British Mycological Society, Vol. 91, No. 3, 1988, pp. 481-488. [34] Y. Rolke, S. liu, T. Quidde, B. Williamson, A. Schouten, K. M Weltring, V. Siewers, K. B. Tenberge, B. Tudzynski and P. Tudzydki, “Functional Analysis of H2O2-Generating Systems in Botrytis cinerea, the Major Cu-Zn-Superoxide Dismutase (BCSOD1) Contributes to Virulence on French bean, Whereas a Glucose Oxidase (BCGOD1) Is Dispen- sable,” Molecular Plant Pathology, Vol. 5, No. 1, 2004, pp. 17-27. [35] M. Weigend and H. Lyr, “The Involvement of Oxidative Stress in the Pathogenesis of Botrytis cinerea on Vicia faba Leaves,” Journal of Plant Diseases and Protection, Vol. 103, 1996, pp. 310-320. [36] R. E. Rij and C. F. Forney, “Phytotoxicity of Vapour Phase Hydrogen Peroxide to Thompson Seedless Grapes and Botrytis cinerea Spores,” Crop Protection, Vol. 14, No. 2, 1995, pp. 131-135. [37] M. A. Ferrer and A. R. Barcelo, “Differential Effects of Nitric Oxide on Peroxidase and H2O2 Production by the Xylem of Zinnia elegans,” Plant, Cell & Environment, Vol. 22, No. 7, 1999, pp. 891-897. |