American Journal of Plant Sciences, 2011, 2, 308-317 doi:10.4236/ajps.2011.23035 Published Online September 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ajps) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. AJPS MADS Box Transcript Amount Is Affected by Ethylene during Abscission Valeriano Dal Cin*, Angelo Ramina Department of Environmental Agronomy and Crop Science, University of Padua, Padua, Italy. Email: *Valeriano_dalcin@yahoo.com, angelo.ramina@unipd.it Received January 16th, 2011; revised March 23rd, 2011; accepted March 30th, 2011. ABSTRACT Thinning of young fruit is an important agronomical practice to ensure the maximum economic production. This prac- tice is based on the control of the natural self thinning process occurring during fruit development. At the early stages of fruit development (fruitlet), the vegetative part of the tree is competing with the reproductive part of the tree and within the fruit clusters the different fruitlets are competing with each other. As a result the least fit organ abscises, Ethylene and auxin play a central role in this event but the role of ethylene is not thoroughly understood because in other systems abscission occurs partly with ethylene independent processes. We have followed the early development of fruitlets and studied th e transcription patterns of MADS-bo x and ethylene related transcripts. Furthermor e, we verified that ethylene has an effect on the expression of some ethylene related and MADS box genes. We propose that the ethyl- ene burst during abscission induction is similar to a stage 2 ethylene system and it is related to fruitlet growth by af- fecting transcript amount of MADS-boxes which modulate seed development and cortex growth. Keywords: Apple, MADS-Box, Ethylene, Fr uit, Ripening 1. Introduction Despite technical advances, growing fruit trees is nowa- days still a very labour and time consuming activity [1]. The fact that these plants are grown over several years makes agronomic practices performed one year affecting both the same year production and the following year’s yield. The case of apple (Malus × domestica L. Borkh) is a typical example of this situation because the number of fruits in one year affects both quality and biennial bear- ing [2,3]. The fruit load is an issue which has been dealt with for countless years with several approaches. The most important approach has been the fruit thinning per- formed by hand throughout the first stages of young fruit development (fruitlet) [4]. Nevertheless, the use of bio- regulators to increase the natural tendency of the trees to shed surplus fruit has taken over by many growers [5]. In an attempt to further decrease the production costs for the growers, a genetic approach which would exploit natural variation of the germplasm is of primary importance [6]. In order to optimize the discovery of traits interesting for a specific fruit load, which would give the best economic value, the study of the abscission physiology in the dif- ferent cultivars is a must [7,8]. Abscission is a common self-mechanism the plant adopts to get rid of specific organs [9]. Fruitlet abscission in apple (Malus × domestica L. Borkh) occurs in a period of competition between reproductive and vegetative parts and among fruitlets [7]. This competition is due to sev- eral factors [8,10,11]. Hormones play a central role in modulating abscission as can be proven by the fact that bioregulators are widely used to thin excess fruitlet load [5]. The studies performed on this species pointed out that auxin, ethylene and their interaction are of primary im- portance [12,13]. Briefly, it was previously found that a massive increase in MdACO1 transcript amount was concomitant with an increase in elements involved in the signal transduction pathway. Furthermore, the variation in transcript amount followed the increase in ethylene evolution [12]. In Arabidopsis, tomato, rice and several other species these genes are present as multigene fami- lies whose members may have specific functions de- pending on the tissue and/or developmental stage [14]. The situation in apple ripening is similar to the other plants [15]. Nevertheless, neither the involvement of eth- ylene nor the function of the specific elements during abscission is completely understood. Ethylene is a hormone with a wide range of functions [16]. In apple abscission induction the increase in ethyl- ene evolution corresponded to a decrease in growth rate  MADS Box Transcript Amount Is Affected by Ethylene during Abscission309 [8]. During abscission induction (the first weeks after full bloom) the stage of cell division is progressively taken over by cell expansion [17-19]. The flower pollination and the subsequent ovule fertilization bring about deep modification of the ontogenetic program of the organ [20]. It has been found that MADS-box proteins play a crucial role in flower and fruit development [21-25]. Al- though the main studies on fruit have been performed on tomato, which is a berry, there are reports indicating that the mechanisms are conserved, at least partially, in other fruit such as banana [26], grape berry [27-29], peach [30] cucumber [31] and apple [17,32-35]. MADS-boxes have also been found involved in vegetative processes [36-39] with good conservation of activity [40,41]. In this manu- script the role of ethylene during abscission is further investigated. Furthermore, the relationship between eth- ylene and the level of the transcripts of some MADS box genes is assessed. 2. Materials and Methods 2.1. Plant Material Experiments were performed as previously reported on eight-year old apple trees (cv Golden Delicious/M9) Malus × domestica bearing two fruitlet populations character- ized by different abscission potential. These populations which were named abscising fruitlet (AF) and non ab- scising fruitlet (NAF) were obtained as previously descri- bed [42]. Apple trees display a natural tendency to shed lateral fruitlets while maintaining central ones. Never- theless, this phenomena is amply variable and in order to maximize and homogenize the starting material the ab- scising fruitlet population (AF) was obtained from lateral fruitlets born on trees sprayed with benzylaminopurine (BA). The product was applied at 200 ppm (commercial form “Brancher-Dirado”) when the average fruit diame- ter was 10 - 12 mm (17 d after petals fall, APF). In this period abscission induction of the shedding process oc- curs [43] It is in this time window that abscission which can be stimulated by thinners with the greatest efficiency [4,5]. A population with almost non abscission, named non-abscising fruitlets (NAF), was generated by remov- ing all the laterals from the cluster at petal fall and leav- ing, exclusively, the central flower freely pollinated at bloom with compatible pollen (cv. Stark Red). Seed, cortex, peduncle (the central 15 mm) and abscission zone (AZ) of each population were collected from fruitlets at 0, 3, 5, 7 days after BA was applied to the AF, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at –80˚C for molecular analy- sis. Fruitlet diameter was measured with a caliber and statistical analysis was performed with a 2 way ANOVA of the GRAPH PAD PRISM software. Parameters stud- ied were population, time and time/population interaction. Threshold was 5%. 2.2. Ethylene Experiment For the ethylene experiment, entire apple fruitlet clusters at 15 DAPF were treated with propylene (1000 μL· L–1) or 1-MCP (1 μL·L–1) or left untreated (control) as de- scribed in [44]. At the end of the treatment fruitlet clus- ters were retrieved and divided into central and lateral. Tissues (abscission zone, peduncle, cortex and seed) were collected at the beginning of the experiment (T0) and after 24 hours for molecular analysis. 2.3. Molecular Biology Studies RNA extraction and expression analyses were as previ- ously described [45,46]. Degenerative primers (Table 1) were designed as previously described [47]. The expres- sion analysis was repeated at different number of cycles but to make the results easily understandable and com- parable both between the two different populations: NAF and AF and among organs (seed, cortex, peduncle and AZ) only significant differences were presented and com- mented (Tables 2 and 3). Primers for expression analyses Table 1. Degenerate primer sequences. geneACCNDirseq T FCAAGARGTTGGGWTGATGAAG 50 ETR55 DQ 84545860 RACTKGCCATCATHGCATTCT FGGMATGGMWCWGAKGTTGCTGT 55 CTR2 DQ 845459 RCAAATCACGTGGAATCTCAAG FATCSCTKTGGKCYARRCARCC 55 EIN2 DQ 845461 RAYKCCCTGWAGRCGRTTGAGA EIN2 3p DQ 845461 FCTTTATGAAGCTGAAACTAGAGAGAT 68 The gene name, the accession number (ACCN), the sequences (seq) of the primer forward (F) and reverse (R) (dir) 5’s→3’ as well as the temperature in ˚C used in the annealing step of the amplification are presented. Table 2. Primer sequence s for ethylene specific genes. gene ACCN DirPrimer F F CGGCACCTTCCTTCCTCA ACO2DQ439790 RGATGACAATGGAGTGGTGCA F CTTGATGCCGTTCAGACAGA ACO4CN907149 R CCAAGATTCTCACACAACAAGC F GTTCTTCCGGTTGCAGAT ETR5 DQ845458 RAGCCAGTTTCTCCCTCATTA F GCTACAAGCGTAGATTATCC EIN2 DQ845461 RCAGAAGATGAGCTGTTTTCC F TACACGTCCTCCAAACCT CTR2 DQ845459 RACAATCGTCGGTGTACTG F CATCCCCCCAGACCAGCAGA UBIDQ438989 R ACCACGGAGACGCAACACCAA F GTTACTTTTAGGACTCCGCC rib 18s RTTCCTTTAAGTTTCAGCCTTG The gene name, the accession number (ACCN), the sequences (seq) of the primer forward (F) and reverse (R) (dir) 5’s→3’ used in the amplification are presented. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. AJPS  MADS Box Transcript Amount Is Affected by Ethylene during Abscission Copyright © 2011 SciRes. AJPS 310 Table 3. primer sequences for MADS box specific genes. GENE ACCN D seq F TTGAGTACGCCACAGATTCAT MADS5 ABG85297 R ATTCAAAGGTCCAGTTACCC F CCCTCATCTTTTTATCC MADS7 CAA04323 R GGTTAAGATCAGAGGTAGACA F TGGCAATATATAAACTGCATG MADS9 CAA04920 R AGCAAGAAATAAGTTCGCAA F GTACAAGGCATGTTCAGAT MADS10 CAA04324 R GCTTCTCCACCCTCGATCA F GGTATGAGCAAAACCCTTGA MADS11 CAA04325 R GATCTTCACCAAGCAAATGC F AGCAGTGGATGACAATGATTC MADS12 CAC86183 R TCAAATGGCGAAAGCATC F GCAGCAGCAAACACATATGAT MADS14 CAC80857 R ATTGGACTCCAAGATCACAG F CCACGATCAGATTTCTCTTCA MADS15 CAC80858 R GACAAGAAATCCCCTTCCAT F GGCACTGGAAGATGAGAATAA PIST AJ291491 R AAGGCAAAAGGTATCTGCTG The gene name, the accession number (ACCN), the sequence (seq) of the primers 5’→3’ and their direction D (F is forward and R is reverse) used in the amplification are presented. were designed with the Gene fisher program http://bibi- serv.techfak.uni-bielefeld.de/genefisher2/ [48] Similarity research was performed at the ncbi website http://blast. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi with the blastp algorithm [49]. Phylogenetic analysis was performed with th MEGA4 program [50]. 3. Results 3.1. Isolation of Ethylene Related Transcripts The fragments isolated in this study encode for an ETR5, a CTR2 and an EIN2. MdETR5 is 663bp (DQ845460) and encodes a fragment of 211aa. The blast analysis in- dicated a high level of similarity to proteins from several species, among which an ETR5 from Malus and Pyrus, and Neverripe and ETR4 from tomato (Table 4). Md- CTR2 (DQ845459) is 614bp and encodes a fragment of 193 aa. The bioinformatic analysis indicated close simi- larity to EDR1 of Arabidopsis thaliana and TCTR2 of tomato (Table 5). Md EIN2 (DQ845461) is 1158bp long and encodes for a partial protein of 302aa, which is highly similar to EIN2 of Arabidopsis and Petunia (Ta- ble 6). Table 4. Level of similarity be tween MdETR5 isolated in this study and other elements present in the database. Annotation ACCNN. identity E-value ethylene receptor 5 [Malus × domestica] ABI58287 99% 5e-101 putative ethylene receptor [Pyrus communis] AAL66193 98% 1e-99 unnamed protein product [Vitis vinifera] CAO65024 80% 6e-78 ethylene receptor [Persea americana] ABY76321 75% 9e-72 hypothetical protein [Vitis vinifera] CAN66907 77% 2e-71 ethylene receptor neverripe [Lycopersicon esculentum]. AAU34077 72% 4e-70 ethylene receptor homolog (ETR4) AAD31396 70% 3e-68 The annotation retrieved by similarity search, the accession number (ACCN), identity and E-values are reported. Table 5. Level of similarity be tween MdCTR2 isolated in this study and other elements present in the database. Annotation Acc. N identity E-value CTR2 protein kinase [Rosa hybrid cultivar] AAK30005 94% 3e-110 unnamed protein product [Vitis vinifera] CAO42985 93% 5e-109 mitogen-activated protein kinase [Medicago sativa] ABD76389 92% 3e-107 enhanced disease resistance 1 [Arabidopsis thaliana] ABR45968 88% 2e-103 enhanced disease resistance 1 [Arabidopsis lyrata] ABR45984 88% 2e-103 TCTR2 protein [Solanum lycopersicum] CAA06334 88% 2e-103 hypothetical protein OsJ_009144 [Oryza sativa (japonica cultivar-group)] EAZ25661 86% 6e-102 The annotation retrieved by similarity search, the accession number (ACCN), identity and E-values are reported.  MADS Box Transcript Amount Is Affected by Ethylene during Abscission311 Table 6. Level of similarity be tween MdEIN2 isolated in this study and other elements present in the database. Annotation Acc. N identity E-value ethylene signaling protein [Prunus persica] ABC94581 85% 2e-146 hypothetical protein [Vitis vinifera] CAN66374 72% 2e-121 EIN2 (ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE 2); transporter [Arabidopsis thaliana] NP_195948 69% 4e-117 EIN2 [Petunia × hybrida] AAR08678 71% 1e-114 sickle [Medicago truncatula] ACD84889 68% 4e-112 ethylene-insensitive 2 [Lycopersicon esculentum] AAZ95507 71% 3e-111 ethylene insensitive 2 [Zea mays] AAR25570 55% 4e-78 The annotation retrieved by similarity search, the accession number (ACCN), identity and E-values are reported. 3.2. Expression of Ethylene Related Genes during Abscission The overall results indicate the genes MdACO2, MdET R5 and MdCTR2 are expressed in all the tissues at similar level; whereas MdACO4 and MdEI N2 are mainly ex- pressed in peduncle and AZ (Figure 1). MdACO4 tran- scripts in seed decreased in both AF and NAF although in NAF the decline was less severe. In cortex the expres- sion was constant in AF whereas it peaked in NAF at day 3 then plunged. In peduncle expression was constant in AF whereas it declined in NAF. In AZ expression re- mained constant. MdETR5 expression in seed first in- creased in both AF and NAF then declined but in NAF the decline was less pronounced. In cortex expression was constant in AF whereas a decline was monitored in NAF. In peduncle transcripts increased in both popula- tions then decreased in NAF while remaining constant in AF. In AZ expression was high and constant in both AF and NAF. MdEIN2 transcript level in seed paralled the one of MdETR5. In cortex the expression was at its low- est and further declined in both AF and NAF. In pedun- cle and AZ expression did not vary. MdCTR2 transcript level was constant in AF whereas it decreased in NAF. In cortex expression slightly increased in AF whereas it steadily declined in NAF. In peduncle and AZ transcript level did not change. 3.3. Fruitlet Growth It was previously found that fruitlet diameter increased even in the days preceding abscission [8]. In this study we confirmed this discovery and found that fruitlet di- ameters significantly increased in both populations but in NAF the increase was more pronounced than in AF (Figure 2). 3.4. Bioinformatic Analysis of the MADS-Box in Malus × domestica The databases present in the world wide web were searched for MADS-box genes of different species: Arabidopsis thaliana, Solanum lycopersicum, Populus tremula and Malus domestica. The results obtained by the blast P algorithm (data not shown) and by the phylogenetic analysis were similar (Figure 3). The sequences of apple Expression analysis on the two populations studied: abscising fruitlets (AF) and non abscising fruitlets (NAF) at different days: 3, 5 and 7. T0 means the beginning of the experiment. Tissue Fruitlet parts are: seed (a), cortex (b), peduncle (c) and AZ (d) of different genes. The number of cycles (N cycles) is reported. Figure 1. Expression analysis of genes involved in ethylene. mm Fruitlet diameter of the cortex fruitlets expressed in mm. Cortex diameter of lateral fruitlets from AF is represented as square. Cortex diameter of fruitlets from NAF is presented as circles. Bars represent SE. Figure 2. Fruitlet diameter. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. AJPS  MADS Box Transcript Amount Is Affected by Ethylene during Abscission 312 MADS-box genes of different species: Arabidopsis thaliana (At), Solanum lycopersicum (Sl), Populus tremula (Pt) and Malus domestica (Md). Similar MADS box proteins are grouped together. The stars indicate the apple MADS box proteins. The accession number follows the name of the proteins. Figure 3. Phylogenetic study of the MADS box proteins known and previously studied in apple. already known are widespread among the several MA- DS-box clades [51,52]. The genes we found expressed clustered in the groups with previously identified genes with known phenotypes. Nevertheless, there was not clear horthologos. MADS5 resemble MC of tomato and CAL of Arabidopsis [53]. MADS7 resembles the tomato RIN and other Arabidopsis SEP genes [53]. MADS9 is in the SEP group and is similar to PHE of Arabidopsis. MADS10 is an AGL probably seedstick (STK) [54]. MADS11 is another AGL similar to TDR3 and 8 of tomato. MADS12 clusters with fruitful (FUL) [55]. MADS14 is an AGL similar to shatterproof (SHP1) [56]. MADS15 is an aga- mous in Arabidopsis (AG) and tomato (TAG1). PIST is a pistillata gene [57] and JNT is similar to tomato jointless [58] (Figure 3). 3.5. Expression of MADS Box Genes during Abscission The overall expression analysis indicated that the most expressed genes were MADS5 and MADS10 in terms of Copyright © 2011 SciRes. AJPS  MADS Box Transcript Amount Is Affected by Ethylene during Abscission313 number of cycles used during analysis and intensity of the signal. Furthermore, the tissues displaying the main changes along abscission were the seed and the cortex (Figure 4). MADS5 transcripts were at a steady state in peduncle and AZ whereas the amount increased in NAF seed and decreased in AF cortex. MADS7 expression was specific of seed where it declined along the experi- ment in both populations but an abrupt increased was detected at day 7 in AF. MADS9 expression in seed de- clined along the experiment but in NAF it was delayed. In cortex expression increased in NAF. In peduncle and AZ expression was at a higher level than seed and cortex and unchanged along the experiment. MADS10 tran- script level in seed decreased in AF while it remained unchanged in NAF. In cortex expression steadily declined in AF whereas it was a sudden in NAF. Similar situation was observed in peduncle. In AZ the expression was lim- ited to NAF at day 3. MADS11 expression in seed de- creased in AF whereas it remained constant in NAF. In cortex expression declined along the experiment in AF more gradually than in NAF. In peduncle transcript level remained at a steady level in AF whereas it declined in NAF. In AZ expression increased in both AF and NAF although earlier in the latter. MADS12 transcripts were detected only in seed at day 7. MADS14 expression was unchanged in seed and peduncle whereas in cortex a de- crease was observed along the experiment more suddenly in NAF. In the AZ of AF the level suddenly decreased at day 7. MADS15 expression in seed declined along ex- periment mainly in AF. In cortex expression declined along experiment, more abruptly in NAF. No variation was observed in peduncle and AZ. MdPIST was detected only in seed of the NAF at day 3 and 7 and in peduncle of the NAF at day 7. Transcripts of JMD were detected only in peduncle and AZ and no difference or variation was observed (data not shown). 3.6. Ethylene Effect on Transcripts The treatments with propylene and 1MCP indicated that MdACO2 is negatively affected by ethylene, whereas Md- ERS1, MdETR5, MdCTR2 and to some extent MdEIN2 expression is positively regulated by ethylene. Of all the MADS investigated, only MADS9 (in cortex) and MA- DS10 (in seed) showed to respond to the treatments, be- ing both negatively regulated by ethylene (Figure 5). 4. Discussion The genes isolated in this study encode for elements in- volved in ethylene perception and transduction [14]. Pre- vious research showed that in apple like in other plants ethylene receptors are encoded by a multigene family [12] and MdETR5 is likely to be the same gene previously isolated [15]. MdCTR2 represents a new element isolated in this species. It has been shown that CTR2 is similar to other CTR1 elements in both Arabidopsis [59] and to- mato [60]. It has also been proposed that the member present in Arabidopsis is likely to be involved in defense mechanisms [61]. The data here presented indicate that CTR2 in apple may have a general role in ethylene signal transduction during apple development. Likewise, it has been demonstrated in tomato that this element may have Expression analysis on the two populations studied: abscising fruitlets (AF) and non abscising fruitlets (NAF) at different days: 3, 5 and 7. T0 means the beginning of the experiment. Tissues Fruitlet parts are: seed (a), cortex (b), peduncle (c) and AZ (d) of different genes. The number of cycles (N cycles) is reported. Figure 4. Expression analysis of MADS box genes. Expression analysis of the genes affected by propylene (P) or 1-MCP (M). The control (C) and the samples at the beginning (T0) of the experiment are also presented. Apart from MADS box 10 (MADS10, studied in seed) all the other expression analysis are from the cortex tissue. Figure 5. Expression analysis of genes affected by ethylene. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. AJPS  MADS Box Transcript Amount Is Affected by Ethylene during Abscission 314 a wider involvement [62] (Lin et al., 2008). The EIN2 in this study is almost identical to the one previously iso- lated [15] and the expression pattern of this gene and of the others genes involved in ethylene biology indicate that the hormone may be involved in mechanisms of de- velopment [63], cell differentiation and programmed cell death like in maize kernel [64]. Nonetheless, these ele- ments have not been previously studied during abscission induction. As previously found [12] the organs in which the changes are most evident during abscission induction are the seed and the cortex. Analogously to previous find- ings, the peduncle also showed late variation in MdETR5 transcript amount. These results confirm that seed and cortex are likely to control the changes in ethylene bio- synthesis and transduction previously described [12]. The results throughout abscission and in the ethylene experi- ment suggest that MdACO2, MdETR5 and MdCTR2 are either directly or secondarily controlled by ethylene. It has been suggested that in apple, ethylene could affect fruit development in the late stages of fruit maturation [65]. Immature apple abscission occurs during the first stages of fruit development in which cell division leads the way to fruitlet growth by cell enlargement [17]. Eth- ylene is not to be considered related to the processes oc- curring immediately after ovule fertilization [20] because 2 weeks after pollination seeds are already in advanced development. It has been found that ethylene is present at basal level in NAF whereas an increase is present in AF [12]. Ethylene at this stage may have a broad importance in development of the different tissues [16]. The expres- sion pattern in seed of MdERS1, MdETR5 and MdEIN2; higher in NAF than AF followed by a sudden decrease may be seen as a delay in development and a total block by day 7. This hypothesis is supported by the drop in both MdAHS and MdPIN1 transcripts previously reported [10,13] and recently revisited in [66]. MdCTR2 transcript level on the other hand may be mainly related to the transduction of the high ethylene level during the first stages of abscission induction [12,8]. This situation may be compared to a system II-like ethylene production where increases in ethylene determine a positive feed- back as previously reported in citrus [67]. The effect of ethylene on fruitlet growth and development previously suggested [8] and here confirmed is likely connected to auxin [13]. The results of the MADSBOX transcripts in- dicate these genes are in general expressed in both re- productive and vegetative parts but could be recruited for different functions as previously found [36]. Neverthe- less, there are some specific domains for MdMADS7 and MdPIST in seed and MdMADS12 in peduncle and AZ. The results concerning MdMADS12 in seed were ob- tained by overexposure of the films and its physiological relevance outside the organs where the horthologs are generally expressed, cannot be inferred without excessive speculation. Our study was not meant to elucidate whe- ther the MADS box isolated in apple have exactly the same physiological function of the genes closely similar in other species. Indeed, as previously found in banana [26] the horthologous genes may not have completely conserved function across species. This statement is es- pecially valid for MADS box with a SEP motif [68]. On the other hand, the function of MADS box proteins with the AG and PIST motives are more conserved across species probably because they have undergone a limited number of duplication [69]. The fact that MdPIST tran- scripts were found only in seed at day 3, at day 7 tran- scripts were detected only by overexposure of the film, and the expression analysis in published literature [57] indicate a specific action of MdPIST during normal ovule development. MdPIST expression may be a result of a signal activating specific changes during ovule de- velopment. The results here presented also indicate that throughout abscission induction there are variations in the transcript amount of MADS-box genes: especially MdMADS5. MdMADS9, MdMADS10, MADS15 and MdPIST. The low transcript amount of MdMADS10 and MdPIST in AF seeds compared to NAF seeds are likely due to a total block or reduced development of the ovule and are the most interesting findings. The decrease or absence of these proteins may reduce development and make the fruitlet sensitive to competition with other fruitlets and with the vegetative part of the plant leading to abscission. Another possibility is that these genes are just related to senescence processes occurring during abscission. A further interesting possibility is that the downregulation of some MADS-box may actually lead to abscission as verified in tomato [70] and that ethylene affects seed development besides other processes such as auxin production and transport and senescence [10,13]. REFERENCES [1] L. Calvin and P. Martin, “The US Produce Industry and Labor: Facingthe Future in a Global Economy,” Eco- nomic Research Report No. (ERR-106), November 2010, p. 106. [2] H. Link, “Significance of Flower and Fruit Thinning on Fruit Quality,” Plant Growth Regulation, Vol. 31, No. 1-2, 2000, pp. 17-26. doi:10.1023/A:1006334110068 [3] V. Dal Cin, M. Danesin, A. Botton, A. Boschetti, A. Dorigoni and A. Ramina, “Fruit Load and Elevation Af- fect Ethylene Biosynthesis and Action in Apple Fruit (Malus domestica L. Borkh) during Development, Matu- ration and Ripening,” Plant Cell and Environment, Vol. 30, No. 11, 2007, pp. 1480-1485. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01723.x [4] K. M. Jones, S. A. Bound, M. J. Oakford and P. Gillard, “Modelling Thinning of Pome Fruits,” Plant Growth Copyright © 2011 SciRes. AJPS  MADS Box Transcript Amount Is Affected by Ethylene during Abscission315 Regulation, Vol. 31, No. 1-2, 2000, pp. 75-84. doi:10.1023/A:1006315000499 [5] S. J. Wertheim, “Developments in the Chemical Thinning of Apple and Pear,” Plant Growth Regulation, Vol. 31, No. 1-2, 2000, pp. 85-100. doi:10.1023/A:1006383504133 [6] L. Sun, M. John Bukovac, P. Forsline and S. van Nocker, “Natural Variation in Fruit Abscission-Related Traits in Apple (Malus domestica),” Euphytica, Vol. 165, No. 1, 2009, pp. 55-67. doi:10.1007/s10681-008-9754-x [7] F. Bangerth, “Abscission and Thinning of Young Fruit and Their Regulation by Plant Hormones and Bioregula- tors,” Plant Growth Regulation, Vol. 31, No. 1, 2000, pp. 43-59. [8] V. Dal Cin, A. Boschetti, A. Dorigoni and A. Ramina, “Benzylaminopurine Application on Two Different Apple Cultivars (Malus domestica L. Borkh) Displays New and Unexpected Fruitlet Abscission Features,” Annals of Bot- any, Vol. 99, No. 6, 2007, 1195-1202. doi:10.1093/aob/mcm062 [9] J. Taylor and C. Whitelaw, “Signals in Abscission,” New Phytologist, Vol. 151, No. 2, 2001, pp. 323-339. doi:10.1046/j.0028-646x.2001.00194.x [10] V. Dal Cin, E. Barbaro, M. Danesin, H. Murayama, R Velasco and A. Ramina, “Fruitlet Abscission: A cDNA AFLP Approach to Study Genes Differentially Expressed during Shedding of Immature Fruits Reveals the In- volvement of a Putative Auxin Hydrogen Symporter in Apple (Malus domestica L. Borkh),” Gene, Vol. 442, No. 1-2, 2009, pp. 26-36. [11] C. Zhou, A. Lakso, T. Robinson and S. Gan, “Isolation and Characterization of Genes Associated with Shade- Induced Apple Abscission,” Molecular Genetics and Ge- nomics, Vol. 280, No. 1, 2008, pp. 83-92. doi:10.1007/s00438-008-0348-z [12] V. Dal Cin, M. Danesin, A. Boschetti, A. Dorigoni and A. Ramina, “Ethylene Biosynthesis and Perception in Apple Fruitlet Abscission (Malus domestica L. Borkh),” Jour- nal of Experimental Botany, Vol. 56, 2005, No. 421, pp. 2995-3005. [13] V. Dal Cin, R. Velasco and A. Ramina, “Dominance In- duction of Fruitlet Shedding in Malus × domestica (L. Borkh): Molecular Changes Associated with Polar Auxin Transport,” BMC Plant Biology, Vol. 9, 2009, p. 139. doi:10.1186/1471-2229-9-139 [14] C. Chang, “Ethylene Biosynthesis, Perception, and Re- sponse,” Journal of Plant Growth Regulation, Vol. 26, No. 2, 2007, pp. 89-91. doi:10.1007/s00344-007-9003-x [15] P. A. Wiersma, H. Zhang, C. Lu, A. Quail and P. M. A. Toivonen, “Survey of the Expression of Genes for Ethyl- ene Synthesis and Perception during Maturation and Rip- ening of ‘Sunrise’ and ‘Golden Delicious’ Apple Fruit,” Postharvest Biology and Technology, Vol. 44, No. 3, 2007, pp. 204-211. doi:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2006.12.016 [16] F. B. Abeles, P. W. Morgan and M. E. Saltveit Jr., “Eth- ylene in Plant Biology,” Academic Press, Inc., Cambridge, 1992. [17] Y. H. Dong, B. J. Janssen, L. B. J. Bieleski, R. G. Atkin- son, B. A. M. Morris and R. C. Gardner, “Isolating and Characterizing Genes Differentially Expressed Early in Apple Fruit Development,” Journal of the American So- ciety for Horticultural Sciences, Vol. 122, No. 6, 1997, pp. 752-756. [18] C. Pratt, “Apple Flower and Fruit: Morphology and Anat- omy,” Horticultural Reviews, Vol. 10, 1988, pp. 273-280. doi:10.1002/9781118060834.ch8 [19] P. Boonkorkaew, S. Hikosaka and N. Sugiyama, “Effect of Pollination on Cell Division, Cell Enlargement, and Endogenous Hormones in Fruit Development in a Gy- noecious Cucumber,” Scientia Horticulturae, Vol. 116, No. 1, 2008, pp. 1-7. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2007.10.027 [20] Y. H. Dong, A. Kvarnheden, J.-L. Yao, P. W. Sutherland, R. G. Atkinson, B. A. Morris and R. C. Gardner, “Identi- fication of Pollination-Induced Genes from the Ovary of Apple (Malus domestica),” Sexual Plant Reproduction, Vol. 11, No. 5, 1998, pp. 277-283. doi:10.1007/s004970050154 [21] J. J. Giovannoni, “Molecular Biology of Fruit Maturation and Ripening,” Annual Review of Plant Physiology & Plant Molecular Biology, Vol. 52, 2001, pp. 725-749. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.52.1.725 [22] J. J. Giovannoni, “Genetic Regulation of Fruit Develop- ment and Ripening,” The Plant Cell, Vol. 16, 2004, pp. S170-S180. doi:10.1105/tpc.019158 [23] J. J. Giovannoni, “Fruit Ripening Mutants Yield Insights into Ripening Control,” Current Opinion in Plant Biology, Vol. 10, No. 3, 2007, pp. 283-289. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2007.04.008 [24] H. Sommer, J. Beltran, P. Huijser, H. Pape, W. Lonnig, H. Saedler and Z. Schwarz-Sommer, “Deficiens, a Homeotic Gene Involved in the Control of Flower Morphogenesis in Antirrhinum majus: The Protein Shows Homology to Transcription Factors,” The EMBO Journal, Vol. 9, No. 3, 1990, pp. 605-613. [25] E. Coen and E. Meyerowitz, “The War of the Whorls: Genetic Interactions Controlling Flower Development,” Nature, Vol. 353, 1991, pp. 31-37. [26] T. Elitzur, J. Vrebalov, J. J. Giovannoni, E. E. Goldsch- midt, and H. Friedman, “The Regulation of MADS-Box Gene Expression during Ripening of Banana and Their Regulatory Interaction with Ethylene,” Journal of Ex- perimental Botany, Vol. 61, No. 5, 2010, pp. 1523-1535. doi:10.1093/jxb/erq017 [27] L. Fernandez, L. Torregrosa, N. Terrier L. Sreekantan, J. Grimplet, D. Davies, M. R. Thomas, C. Romieu and A. Ageorges, “Identification of Genes Associated with Flesh Morphogenesis during Grapevine Fruit Development,” Plant Molecular Biology, Vol. 63, No. 3, 2007, pp. 307-323. doi:10.1007/s11103-006-9090-2 [28] J. Diaz-Riquelme, D. Lijavetzky, J. M. Martinez-Zapater and M. J. Carmona, “Genome-Wide Analysis of MIKCC- Type MADS Box Genes in Grapevine,” Plant Physiology, Vol. 149, No. 1, 2009, pp. 354-369. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. AJPS  MADS Box Transcript Amount Is Affected by Ethylene during Abscission 316 doi:10.1104/pp.108.131052 [29] M. J. Poupin, F. Federici, C. Medina, J. T. Matus, T. Timmermann and P. Arce-Johnson, “Isolation of the Three Grape Sub-Lineages of B-Class MADS-Box TM6, PISTILLATA and APETALA3 Genes Which Are Dif- ferentially Expressed during Flower and Fruit Develop- ment,” Gene, Vol. 404, No. 1-2, 2007, pp. 10-24. [30] Y. Xu, L. Zhang, H. Xie, Y.-Q. Zhang, M. Oliveira and R.-C. Ma, “Expression Analysis and Genetic Mapping of Three SEPALLATA-Like Genes from Peach (Prunus persica (L.) Batsch),” Tree Genetics & Genomes, Vol. 4, No. 4, 2008, pp. 693-703. doi:10.1007/s11295-008-0143-3 [31] M. K. Filipecki, H. Sommer and S. Malepszy, “The MADS-Box Gene CUS1 Is Expressed during Cucumber Somatic Embryogenesis,” Plant Science, Vol. 125, No. 1, 1997, pp. 63-74. doi:10.1016/S0168-9452(97)00056-3 [32] S.-K. Sung, G.-H. Yu, J. Nam, D.-H. Jeong and G. An, “Developmentally Regulated Expression of Two MADS- Box Genes, MdMADS3 and MdMADS4, in the Morpho- genesis of Flower Buds and Fruits in Apple,” Planta, Vol. 210, No. 4, 2000, pp. 519-528. [33] S.-K. Sung, G.-H. Yu and G. An, “Characterization of MdMADS2, a Member of the SQUAMOSA Subfamily of genes, in Apple,” Plant Physiology, Vol. 120, No. 4, 1999, pp. 969-978. doi:10.1104/pp.120.4.969 [34] T. Foster, R. Johnston and A. Seleznyova, “A Morpho- logical and Quantitative Characterization of Early Floral Development in Apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.),” Annals of Botany, Vol. 92, No. 2, 2003, pp. 199-206. [35] S.-K. Sung and G. An, “Molecular Cloning and Charac- terization of a MADS-Box cDNA Clone of the Fuji Ap- ple,” Plant Cell Physiology, Vol. 38, No. 4, 1997, pp. 484-489. [36] F. García-Maroto, M. J. Carmona, J. A. Garrido, M. Vil- ches-Ferrón, J. Rodríguez-Ruiz and D. López Alonso, “New Roles for MADS-Box Genes in Higher Plants,” Biologia Plantarum, Vol. 46, No. 3, 2003, pp. 321-330. [37] C. G. van der Linden, B. Vosman and M. J. M. Smulders, “Cell and Molecular Biology, Biochemistry and Molecu- lar Physiology. Cloning and Characterization of Four Ap- ple MADS Box Genes Isolated from Vegetative Tissue,” Journal of Experimental Botany, Vol. 53, No. 371, 2002, pp. 1025-1036. [38] T. Jack, “Plant Development Going MADS,” Plant Mo- lecular Biology, Vol. 46, No. 5, 2001, pp. 515-520. doi:10.1023/A:1010689126632 [39] S. Rounsley, G. Ditta and M. Yanofsky, “Diverse Roles for MADS Box Genes in Arabidopsis Development,” The Plant Cell, Vol. 7, No. 8, 1995, pp. 1259-1269. [40] H. Flachowsky, A. Peil, T. Sopanen, A. Elo and V. Hanke, “Overexpression of BpMADS4 from Silver Birch (Betula pendula Roth.) Induces Early-Flowering in Apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.),” Plant Breeding, Vol. 126, No. 2, 2007, pp. 137-145. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0523.2007.01344.x [41] N. Kotoda and M. Wada, “MdTFL1, a TFL1-LIke Gene of Apple, Retards the Transition from the Vegetative to Reproductive Phase in Transgenic Arabidopsis,” Plant Science, Vol. 168, No. 1, 2005, pp. 95-104. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2004.07.024 [42] V. Dal Cin, F. Rizzini, A. Botton and P. Tonutti, “The Ethylene Biosynthetic and Signal Transduction Pathways Are Differently Affected by 1-MCP in Apple and Peach Fruit,” Postharvest Biology and Technology, Vol. 42, No. 2, 2006, pp. 125-133. [43] H. Link, “Significance of Flower and Fruit Thinning on Fruit Quality,” Plant Growth Regulation, Vol. 31, No. 1-2, 2000, pp. 17-26. doi:10.1023/A:1006334110068 [44] V. Dal Cin, G. Galla, A. Boschetti, A. Dorigoni, R. Velasco and A. Ramina, “Ethylene Involvement in Auxin Transport during Apple Fruitlet Abscission. (Malus × domestica L. Borkh.),” Advances in Plant Ethylene Re- search, Vol. 2, 2007, pp. 89-93. [45] V. Dal Cin, G. Galla and A. Ramina, “MdACO Expres- sion during Abscission. The Use of 33P Labeled Primers in Transcript Quantitation,” Molecular Biotechnology, Vol. 36, No. 1, 2007, pp. 9-13. doi:10.1007/s12033-007-0004-6 [46] V. Dal Cin, M. Danesin, F. Rizzini and A. Ramina, “RNA Extraction from Plant Tissues: The Use of Calcium to Precipitate Contaminating Pectic Sugars,” Molecular Biotechnology, Vol. 31, No. 2, 2005 pp. 113-120. doi:10.1385/MB:31:2:113 [47] P. Nguyen and V. Dal Cin, “The Role of Light on Foliage Colour Development in Coleus (Solenostemon scutel- lariodes (L.) Codd),” Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, Vol. 47, No. 10, 2009, pp. 934-945. [48] C. Schleiermacher, “GeneFisher—Software Support for the Detection of Postulated Genes,” International Con- ference on Intelligent Systems for Molecular Biology, Vol. 4, 1996, pp. 68-77. [49] S. Altschul, T. Madden, A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller and D. Lipman, “Gapped BLAST and PSI- BLAST: A New Generation of Protein Database Search Programs,” Nucleic Acids Research, Vol. 25, No. 17, 1997, pp. 3389-3402. doi:10.1093/nar/25.17.3389 [50] K. Tamura, J. Dudley, M. Nei and S. Kumar, “MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) Soft- ware Version 4.0,” Molecular Biology and Evolution, Vol. 24, No. 8, 2007, pp. 1596-1599. doi:10.1093/molbev/msm092 [51] L. Parenicova, S. de Folter, M. Kieffer, D. S. Horner, C. Favalli, J. Busscher, H. E. Cook, R. M. Ingram, M. M. Kater, B. Davies, G. C. Angenent and L. Colombo, “Mo- lecular and Phylogenetic Analyses of the Complete MA- DS-Box Transcription Factor Family in Arabidopsis: New Openings to the MADS World,” The Plant Cell, Vol. 15, No. 7, 2003, pp. 1538-1551. doi:10.1105/tpc.011544 [52] L. C. Hileman, J. F. Sundstrom, A. Litt, M. Chen, T. Shumba and V. F. Irish, “Molecular and Phylogenetic Analyses of the MADS-Box Gene Family in Tomato,” Molecular Biology and Evolution, Vol. 23, No. 11, 2006, pp. 2245-2258. doi:10.1093/molbev/msl095 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. AJPS  MADS Box Transcript Amount Is Affected by Ethylene during Abscission Copyright © 2011 SciRes. AJPS 317 [53] J. Vrebalov, D. Ruezinsky, V. Padmanabhan, R. White, D. Medrano, R. Drake, W. Schuch and J. Giovannoni, “A MADS-Box Gene Necessary for Fruit Ripening at the Tomato Ripening-Inhibitor (Rin) Locus,” Science, Vol. 296, No. 5566, 2002, pp. 343-346. [54] E. Tani, A. N. Polidoros, E. Flemetakis, C. Stedel, C. Kalloniati, K. Demetriou, P. Katinakis and A. S. Tsaftaris, “Characterization and Expression Analysis of AGA- MOUS-Like, SEEDSTICK-Like, and SEPALLATA-Like MADS-Box Genes in Peach (Prunus persica) Fruit,” Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, Vol. 47, No. 8, 2009, pp. 690-700. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2009.03.013 [55] V. Cevik, C. Ryder, A. Popovich, K. Manning, G. King and G. Seymour, “A FRUITFULL-like Gene Is Associ- ated with Genetic Variation for Fruit Flesh Firmness in Apple (Malus domestica Borkh.),” Tree Genetics & Ge- nomes, Vol. 6, No. 2, 2010, pp. 271-279. doi:10.1007/s11295-009-0247-4 [56] J. Vrebalov, I. L. Pan, A. Javier, M. Arroyo, R. McQuinn, M. Y. Chung, M. Poole, J. Rose, G. Seymour, S. Gran- dillo, J. Giovannoni and V. F. Irish, “Fleshy Fruit Expan- sion and Ripening Are Regulated by the Tomato SHAT- TERPROOF Gene TAGL1,” The Plant Cell, Vol. 21, No. 10, 2009, pp. 3041-3062. doi:10.1105/tpc.109.066936 [57] J.-L. Yao, Y.-H Dong and B. A. M. Morris, “Partheno- carpic Apple Fruit Production Conferred by Transposon Insertion Mutations in a MADS-Box Transcription Fac- tor,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, Vol. 98, No. 3, 2001, pp. 1306-1311. doi:10.1073/pnas.031502498 [58] L. Mao, D. Begum, H.-W. Chuang, M. A. Budiman, E. J. Szymkowiak, E. E. Irish and R. A. Wing, “JOINTLESS Is a MADS-Box Gene Controlling Tomato Flower Ab- scission Zone Development,” Nature, Vol. 406, 2000, pp. 910-913. [59] Y. Huang, H. Li, C. E. Hutchison, J. Laskey and J. J. Kieber, “Biochemical and Functional Analysis of CTR1, a Protein Kinase That Negatively Regulates Ethylene Signaling in Arabidopsis,” The Plant Journal, Vol. 33, No. 2, 2003, pp. 221-233. doi:10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01620.x [60] L. Adams-Phillips, C. Barry, P. Kannan, J. Leclercq, M Bouzayen and J. Giovannoni, “Evidence That CTR1-Me- diated Ethylene Signal Transduction in Tomato Is En- coded by a Multigene Family Whose Members Display Distinct Regulatory Features,” Plant Molecular Biology, Vol. 54, No. 3, 2004, pp. 387-404. doi:10.1023/B:PLAN.0000036371.30528.26 [61] C. A. Frye, D. Z. Tang and R. W. Innes, “Negative Regu- lation of Defense Responses in Plants by a C. A. Con- served MAPKK Kinase,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, Vol. 98, No. 1, 2001, pp. 373-378. doi:10.1073/pnas.011405198 [62] Z. Lin, L. Alexander, R. Hackett and D. Grierson, “Le- CTR2, a CTR1-Like Protein Kinase from Tomato, Plays a Role in Ethylene Signalling, Development and De- fence,” The Plant Journal, Vol. 54, No. 6, 2008, pp. 1083-1093. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03481.x [63] H.-L. Zhu, B.-Z. Zhu, Y. Shao, X.-G. Wang, X.-J. Lin, Y.-H. Xie, Y.-C. Li, H.-Y. Gao and Y. B. Luo, “Tomato Fruit Development and Ripening Are Altered by the Si- lencing of LeEIN2 Gene,” Journal of Integrative Plant Biology, Vol. 48, No. 12, 2006, pp. 1478-1485. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7909.2006.00366.x [64] D. Gallie and T. Young, “The Ethylene Biosynthetic and Perception Machinery Is Differentially Expressed during Endosperm and Embryo Development in Maize,” Mo- lecular Genetics and Genomics, Vol. 271, No. 3, 2004, pp. 267-281. [65] V. Dal Cin, M. Danesin, A. Botton, A. Boschetti, A. Dorigoni and A. Ramina, “Ethylene and Preharvest Drop: The Effect of AVG and NAA on Fruit Abscission in Ap- ple (Malus domestica L. Borkh),” Plant Growth Regula- tion, Vol. 56, No. 3, 2008 pp. 317-325. doi:10.1007/s10725-008-9312-5 [66] A. Botton, G. Eccher, C. Forcato, A. Ferrarini, M. Beg- heldo, M. Zermiani, S. Moscatello, A. Battistelli, R. Vela- sco, B. Ruperti and A. Ramina, “Signalling Pathways Me- diating the Induction of Apple Fruitlet Abscission,” Plant Physiology, Vol. 155, No. 1, pp. 185-208. [67] E. Katz, P. Lagunes, J. Riov, D. Weiss and E. Goldschmidt, “Molecular and Physiological Evidence Suggests the Exis- tence of a System II-Like Pathway of Ethylene Production in Non-Climacteric Citrus Fruit,” Planta, Vol. 219, No. 2, 2004, pp. 243-252. [68] S. T. Malcomber and E. A. Kellogg, “SEPALLATA Gene Diversification: Brave New Whorls,” Trends in Plant Sci- ence, Vol. 10, No. 9, 2005, pp. 427-435. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2005.07.008 [69] A. Mazzucato, I. Olimpieri, F. Siligato, M. E. Picarella and G. P. Soressi, “Characterization of Genes Controlling Stamen Identity and Development in a Parthenocarpic Tomato Mutant Indicates a Role for the DEFICIENS Ortholog in the Control of Fruit Set,” Physiologia Plan- tarum, Vol. 132, No. 4, 2008, pp. 526-537. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3054.2007.01035.x [70] C. Ampomah-Dwamena, B. A. Morris, P. Sutherland, B. Veit and J.-L. Yao, “Down-Regulation of TM29, a Tomato SEPALLATA Homolog, Causes Parthenocarpic Fruit De- velopment and Floral Reversion,” Plant Physiology, Vol. 130, No. 2, 2002, pp. 605-617.

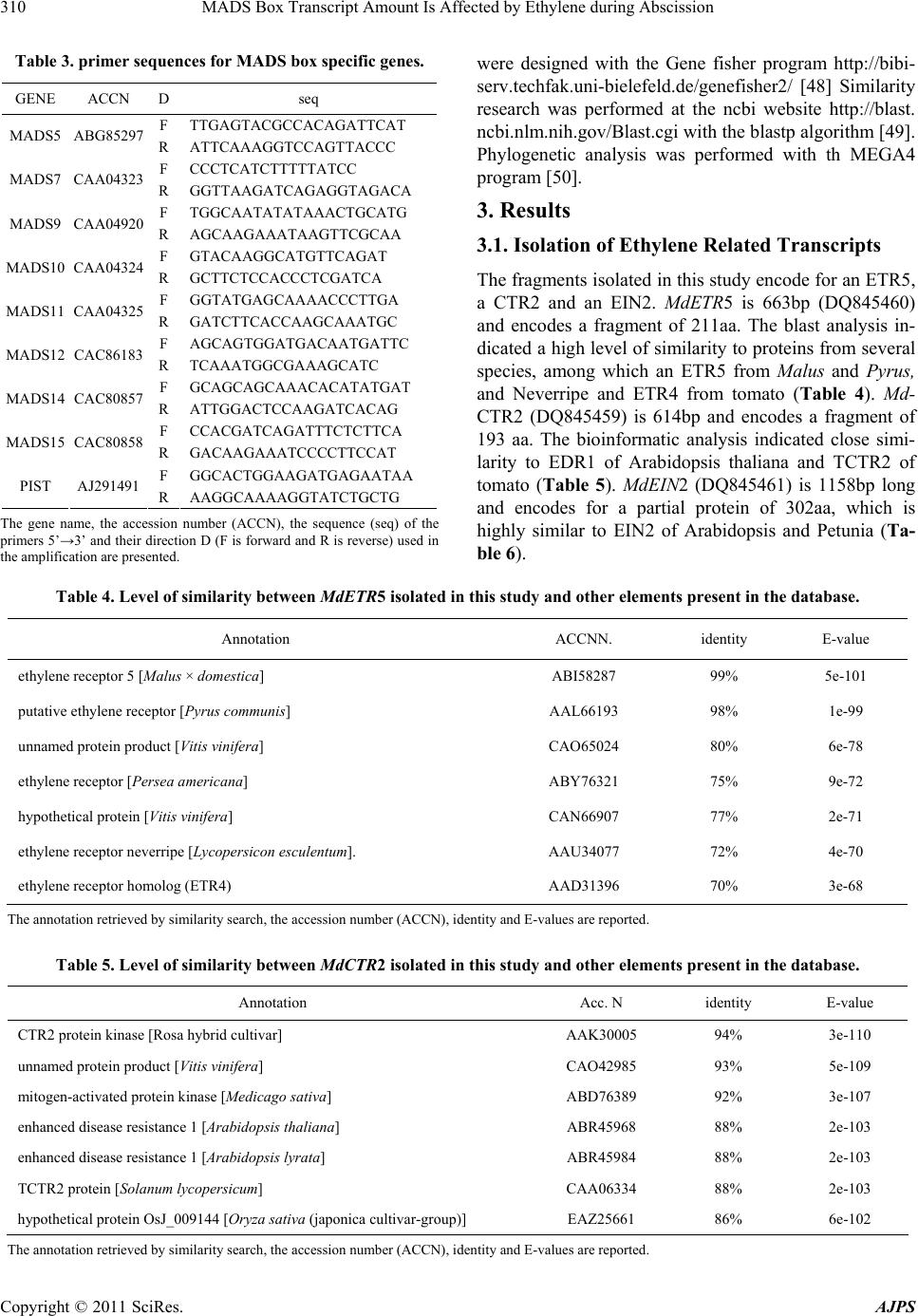

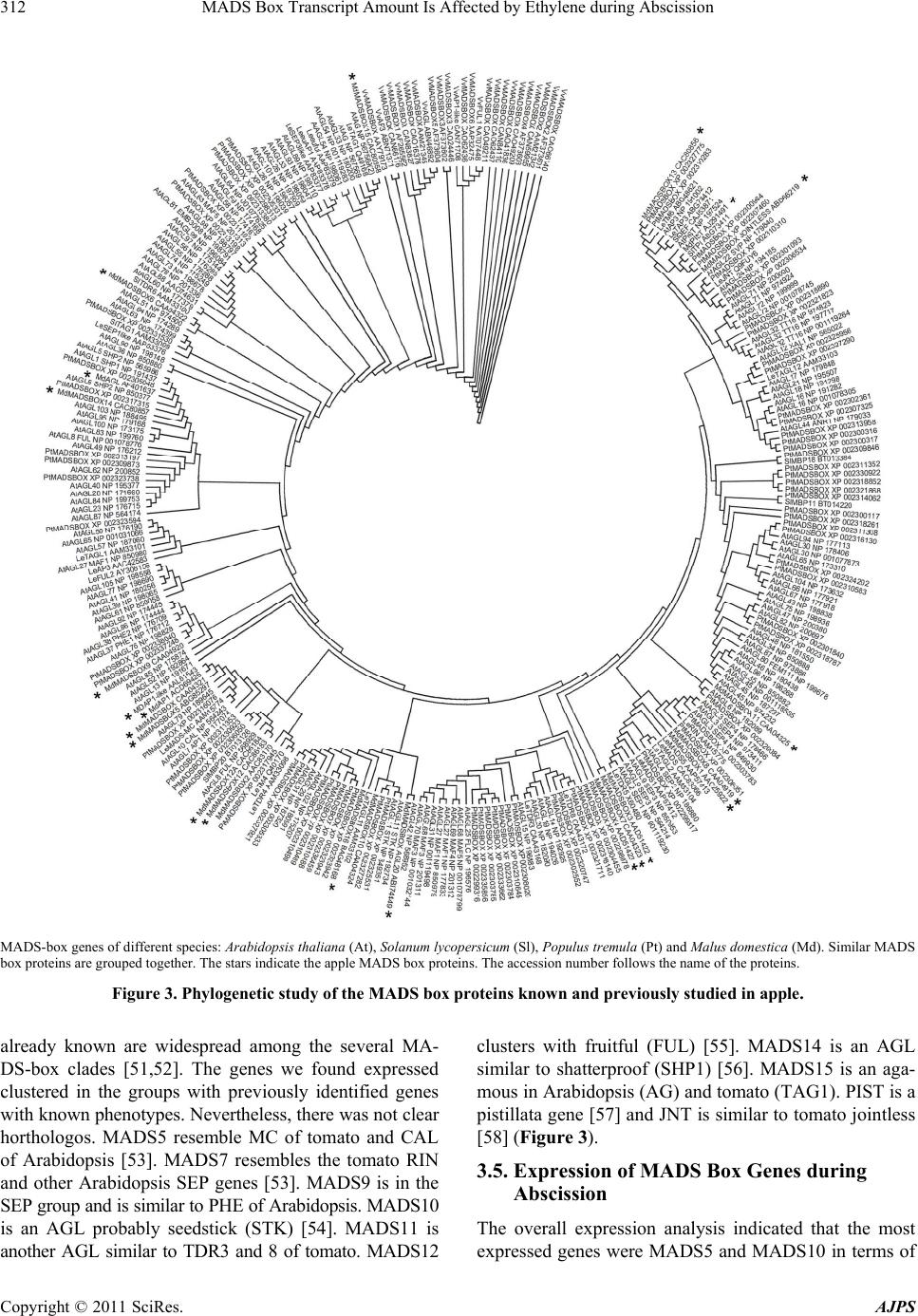

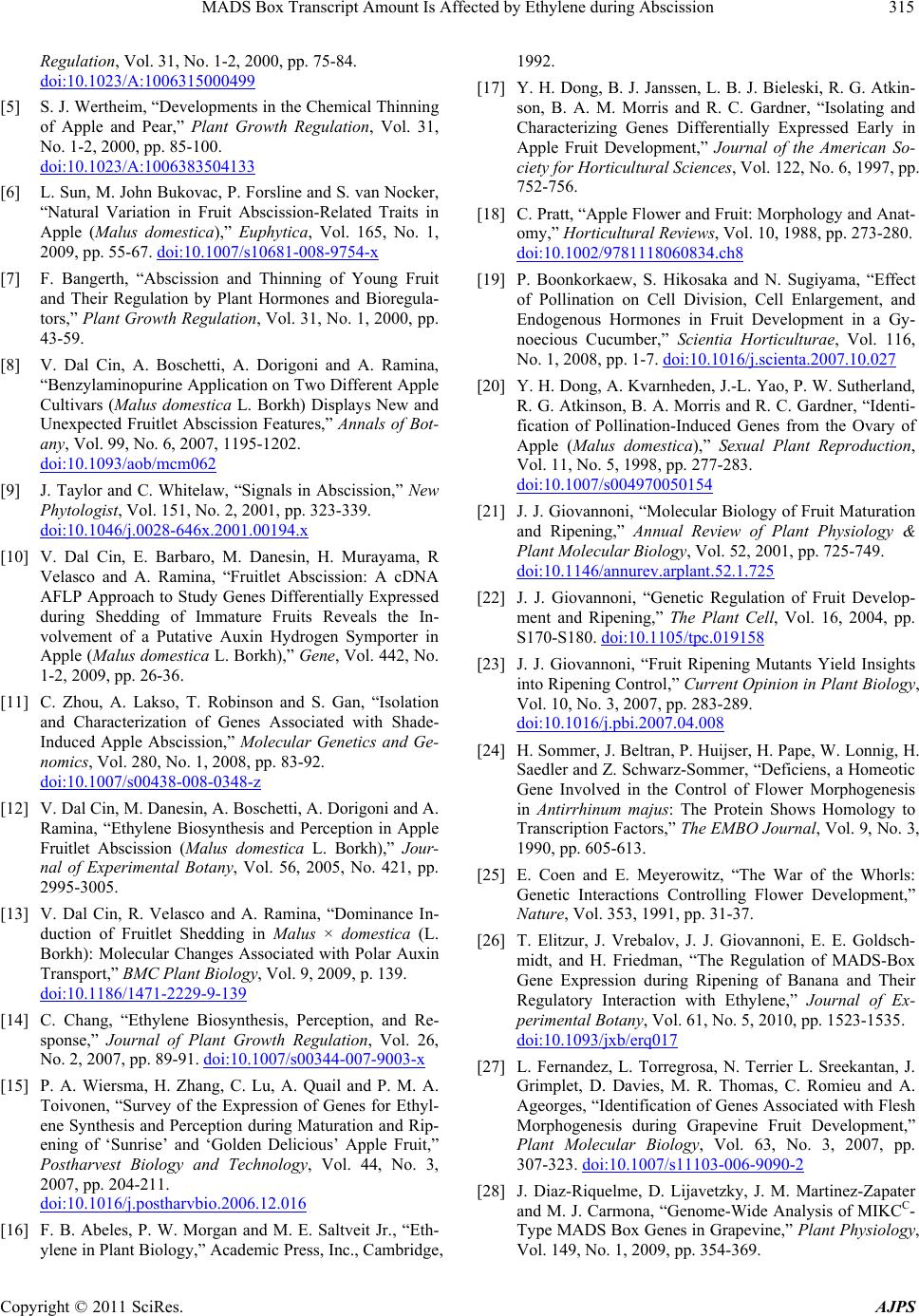

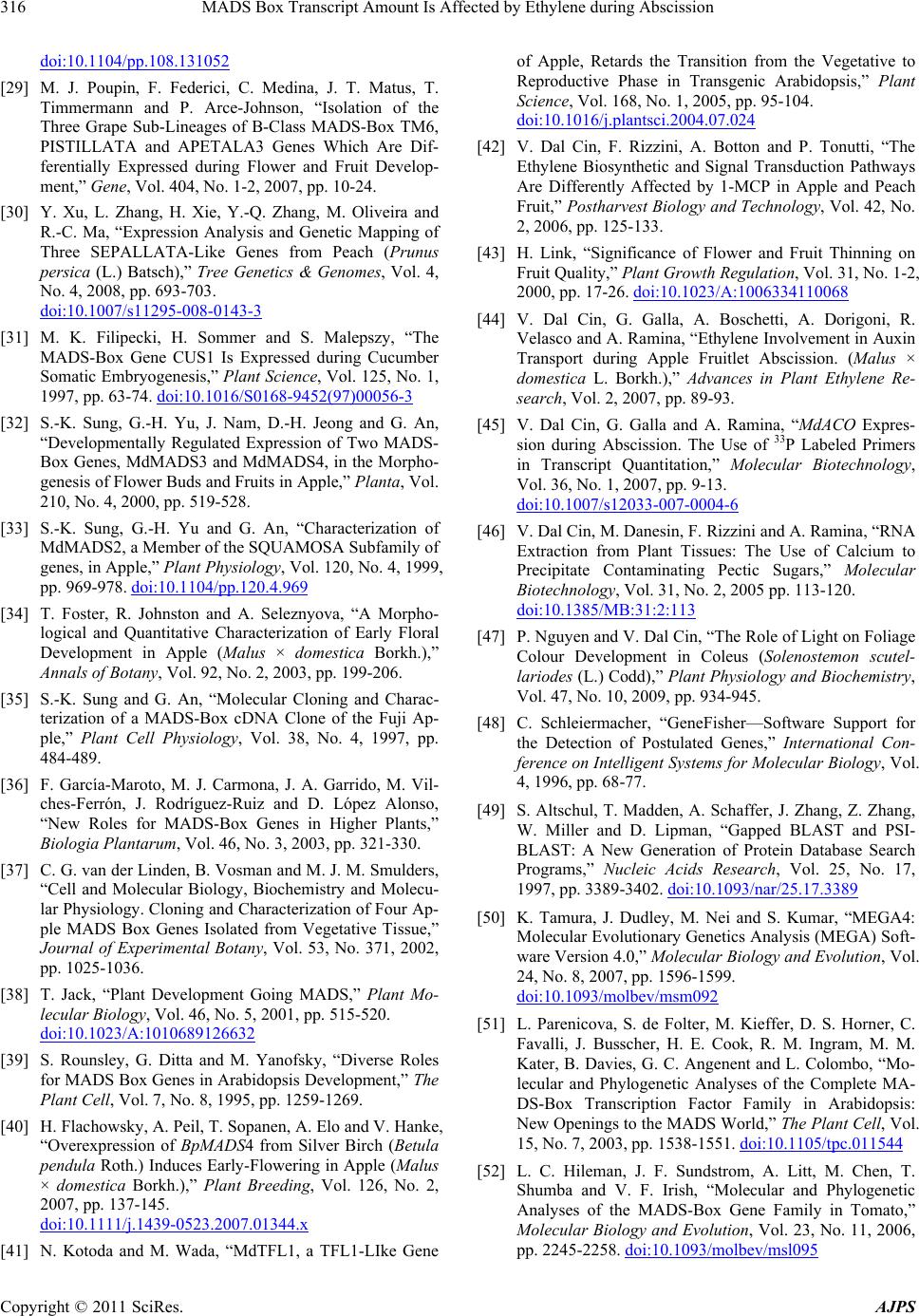

|