Journal of Service Science and Management, 2011, 4, 368-379 doi:10.4236/jssm.2011.43043 Published Online September 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jssm) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM Factors and Home- and Community-Based Services (HCBS) that Predict Older Adults’ Residential Transitions Ya-Mei Chen1, Elaine Adams Thompson2, Bobbie Berkowitz3, Heather M. Young4, Deborah Ward4 1National Taiwan University, Taipei, China; 2University of Washington, Seattle, USA; 3Columbia University, New York, USA; 4University of California, Oakland, USA. Email: yameic@u.washington.edu Received February 21st, 2011; revised April 25th, 2011’ accepted May 16th, 2011. ABSTRACT Objectives: This study identified specific personal factors and home- and community-based services (HCBS) that predict older adults’ residential transitions between community and institutional settings. Method: Logistic regres- sion of interview data fro m 5294 participants in the Second Longitudinal Study of Aging identified predictors of three residential transition patterns and of frequency and duration of institutional services use. Results: Different HCBS services differently affected residential transitions. Informal support and paid personal care services (PCS) were the main factors affecting older adults’ ability to reside in community settings or to remain in community longer. Fre- quency of HCBS use and quan tity of paid PCS used indicated direction of transitions: from communities into institu- tions or vice versa. Discussion: Integration of informal and formal care systems and attention to community-dwell- ing older adults’ HCBS use and paid PCS use, as a guide for possible future transitions, are tasks for community care professionals. Keywords: Long-term Care, Policy, Community-based Services, HCBS, Older Adult s, Residential Transitions 1. Introduction Research studies that investigate personal factors and home- and community-based services (HCBS) that pre- dict older adults’ use of nursing home services make a long list in the PUBMED library, but none takes older adults’ residential transitions into co nsideration. Personal factors and HCBS use patterns that predict older adults’ residential transitions could be different from the factors and service patterns that predict nursing home use. As HCBS become increasingly available, older adults transit through different residential statuses over a period of time. Different transition patterns have been noted. As various services meet their needs, older adults may move from communities to institutions or from institutions back to communities. Our aim was to explore which personal factors and which HCBS uses predict different residential transitions. With such knowledge, communities with spe- cific needs can better allocate resources for older adults. This knowledge will be valuable for developing an effec- tive community-based long-term care system. 2. Background Factors that predict older adults’ nursing home use have been investigated for decades [1,2]. Many personal fac- tors, such as age, education level, and social support, have been found to be significantly predict older adults’ subsequent nursing home use [3,4]. Ever since HCBS developed in the 1970s, research studies have further included HCBS to investigate its effect on older adults’ nursing home use [3,5-7]. However, findings have been inconsistent. Most studies in the literature reported a positive relationship between older adults’ use of HCBS and nursing-home admissions [6,8]. Some showed HCBS to reduce nursing-home admissions only for some groups [6,9,10]. Home and community-based settings refer to houses or units in facilities which provide residents with autonomy and control over living and service arrangements. Resi- dential settings in un its that are neith er self-con tained nor self-sufficient are considered institutions; total care, in- cluding skilled nursing care, personal care, and house- hold function s, is provided. Units in institu tions are often  Factors and Home- and Community-Based Services (HCBS) that Predict Older Adults’ Residential Transitions 369 shared by nonrelated residents. Because HCBS are in- creasingly available, older adults may transit through different residential statuses as the various services meet their needs. However, research studies have failed to acknowledge societal changes in HCBS availability and older adults’ residential transitions. This may contribute to the inconsistent and controversial findings in the lit- erature regarding the effect of HCBS on nursing-home use. Bishop (1999) has pointed out the need for better population-based studies to track these residential transi- tions and ascertain whether older adults with disabilities are receiving the care they need. Another issue contributing to inconsistent research findings is the cross-sectional design commonly used in previous research studies on aging and the effects older adults’ HCBS use, and it does not allow researchers to study the dynamic of older adults’ residential transitions and use of HCBS [11]. Investigating HCBS and residen- tial transitions from a longitudinal perspective may pro- vide a better picture of the effects of HCBS. This study used Andersen’s Health Behavioral Model to predict older adults’ residential transitions in a national longitu- dinal dataset that covered 6 years of study 3. Conceptual Framework—Health Behavioral Model (HBM) The conceptual framework was based upon Andersen’s HBM model, one of the most widely used behavioral models, to encompass older adults’ use of HCBS, as well as all the Health Behavioral Model factors, as influences on behavior in the form of residential transitions [12-16]. It posits that older adults’ use of HCBS and ability to remain in their communities through different residential transitions is a function of 1) their predisposition to use services; 2) factors that enable or impede their use of services; and 3) their perceived need for services and older adults ability to remain in community is the func- tion of the three factors mentioned above plus older adults’ use of HCBS. 3.1. Predisposing Factors The model’s predisposition component describes the ways in which some individuals have a greater propen- sity to use health services than do others. Such propensi- ties can be predicted based on certain characteristics of the individual, such as age and gender, prior to the onset of any specific illness episode [3,13,17]. These charac- teristics have been reported to affect older adults’ HCBS use [15,16] and olde r a dul t s’ nursing home use [18,19]. 3.2. Enabling Factors A condition that permits an individual to act on a value or to satisfy a need is defined as an enabling condition. Enabling conditio ns include the social environment, such as informal caregiving support and home environment, and financial resources, such as family income status [13]. Miller and Weissert’s review [18] showed receipt of informal caregiving associated with increased risk of institutionalization. 3.3. Perceived Need Factors and Disability Factors Finally, although predisposing and enabling factors are necessary conditions for the use of health services, they are not sufficient. To seek services, an individual must perceive some need to do so. Apart from age, need factors have the greatest impact on nursing home entry [20]. Per- ceived need may result from illness or from aging-related functional disabilities. Researchers have found perceived need for services to be important for HCBS use among families providing care to dependent older adults [16]. Awareness of needs allows appropriate matching of ser- vices HCBS to enable individuals to live independently for as long as possible [21]. Disability factors are also key factors for HCBS use and for older adults’ ability to live in communities [4,16,22,23]. 3.4. HCBS Use Since older adults are likely to use community-based services before turning to institutional services, we also expected older adults’ use of HCBS to be an important factor in their residential transitions. Our conceptual framework focuses on the relationship between older adults’ use of HCBS and their ability to remain in com- munities through different kinds of transitions. Discus- sions about this relationship vary. Some studies report that disabled older persons who received formal HCBS services entered nursing homes at a higher rate [8,24]; other studies report the opposite relationship and con- clude that, when targeted to an appropriate subgroup, use of nondiscretionary services is negatively associated with nursing home use [6,10]. However, it has been unclear whether different HCBS predicted different tran- sitions. The purpose of this study was: 1) To identify factors re- lated to older adults’ personal characteristics, such as age and gender, that predict older adults’ residential transitio ns, and 2) To identify uses of HCBS that predict older adults’ residential transitions, such as identifying what services might help older adul ts rem ain i n t hei r comm unit i es longer, and what services might help them move back to their communities after having been institutionalized. This study used the Health Behavioral Model as a framework and guide for selecting variables and for analyzing the relationships between older adults’ use of HCBS and their Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Factors and Home- and Community-Based Services (HCBS) that Predict Older Adults’ Residential Transitions 370 residential transitions with a longitudi nal perspective. 4. Methods 4.1. Data Source—The Second Longitudinal Study of Aging (LSOA II) The study used data from the Second Longitudinal Study of Aging (The Second Longitudinal Study of Aging, 2002). Using the LSOA II, this study analyzed nationally representative civilian noninstitutionalized persons aged 70 years or older. Sampling followed a stratified, multi- stage probability design that permitted continuous sam- pling of the target population. After baseline face-to face interviews in 1994 (Time 1 [T1]; N = 9447), two follow- up interviews occurred using Computer Assisted Tele- phone Interviews [25]: one between 1997 and 1998 (Time 2 [T2]; N = 7,060), and one between 1999 and 2000 (Time 3 [T3]; N = 5,294). Loss of respondents was due to attrition from death and loss of tracking. Our analysis included only those respondents who partici- pated in all three waves (N = 5,294). Three sample weights were employed to account for the LSOA II com- plex sampling survey design. Missing values in the study variables represented less than 5% of observations, with the exception of the com- munity service utilization variables (missing 8.8% to 15.6% of observations) and the income variable (missing 21% of observations). We replaced missing values from responses such as “not ascertained” and “don’t know or refused” using the Markov Chain Monte Carlo method through the multiple-imputation procedure in LISREL 8.53 [26]. 4.2. Sample A total of 5294 older adults, those who had completed all three LSOA II interviews, were included in the data analysis for this study. At baseline interview in 1994, respondents’ ages ranged from 70 to 99 years, with a mean of 75.52 5.26. About two thirds of the respon- dents (63.1%) were female. Participants’ average number of years of education was 11.46 3.40. Family income ranged fro m $1,000 to more than $50,000 a year, with an average range of $15,000 to $16,999. The participants were living alone (33.8%) or with a spouse or other fam- ily member (65.4%) (Please see Table 1). 4.3. Measures Variables for this study were selected based on the Health Behavioral Model described above. The dependent vari- ables were older adults’ residential transitions; the inde- pendent variables were older adults’ use of HCBS. Older adults’ personal factors, based on the Health Behavioral Model variables, were included as covariates. 4.3.1. Dependent Variables—Older Adults’ Residential Transitions At each interview (T1, T2, and T3), each older adult was either in a home- and community-based setting (C) or in an institution (I). Home- and community-based settings included 1) single-family homes; 2) regular apartments; 3) retirement homes; 4) assisted living facilities; 5) super- vised apartments; 6) group homes; 7) halfway houses; 8) board homes; and 9) developmental centers. Institutions included 1) nursing homes and 2) convalescent homes. All older adults included in LSAO II lived in communi- ties at T1 interview. The question asked at T2 and T3 interviews regarding older adults’ residential status was: “Is the place where you live a … (one of the 11 options described above)?” and “Since the last interview, have you been a resident in a nursing home/convalescent home?” (The Second Longitudinal Study of Aging—The Second Supplement on Aging, 1994). Each respondent who indicated living in a nursing home, in answers to either of these questions, was considered a transition to institution during that period of time. Respondents whose answers did not indicate nursing home use were consid- ered to be living in community. When respondents moved between living arrange ments, the transition s were noted. Data in LSOA II were collected three times: in 1994 (T1), 1997 (T2), and 2000 (T3). Using these three time points, we defined four types of residential transi- tions: 1) CCC: older adults who resided in community from T1 to T3 and did not use any nursing home service from 1994 to 2000; 2) CIC: older adults who resided in community at T1, had moved to an institution between T1 and T2, including T2, and had returned to community and had not used any nursing home services between T2 and T3; 3) CCI: older adults who resided in community between T1 and T2, including T2, and did not use any nursing home services during this period of time, but had used nursing home services between T2 and T3, includ- ing at T3; and 4) CII: older adults who resided in com- munity at T1 but resided in an institution between T1 and T2, including T2, and between T2 and T3, including at T3. 4.3.2. Independent Variables—Older Adults’ HCBS Use A total of 13 HCBS were available in the LSOA II be- tween T1 and T2 interviews, as well as the frequency of services use during the three months prior to the T2 in- terview. These services were 1) senior centers; 2) meals On Wheels; 3) meals at senior centers/facilities; 4) ho- memaker/companion services; 5) personal care services (PCS); 6) skilled nursing care; 7) physical therapy; 8) occupational therap y; 9) speech therap y; 10) dialysis; 11) tube feeding; 12) oxygen or respiratory therapy, and Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Factors and Home- and Community-Based Services (HCBS) that Predict Older Adults’ Residential Transitions Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM 371 Table 1. Definition and distribution of health behavioral model (HBM) covariates (data from T1 interview). HBM Variables Operational Definitions Mean (SD, Range) Predisposing Factors Age Years of age 75.52 (5.26, 69 - 97) Education Years of education 11.46 (3.41, 0 - 18) Household size No. living in the same household 1.85 (0.91, 1 - 11) Gender Female Male N = 3339 (63.07%) N = 1955 (36.93%) Marital status Married N = 2928 (55.42%) Enabling Factors Unpai d ADL help Types of Activities of Daily Living (e.g., bathing) assisted by up to four unpaid helpers (0 - 28) 0.24 (1.13, 0 -18) Unpaid IADL help Types of Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (e.g., preparing a meal) assisted by up to four unpaid helpers (0 - 32) 0.68 (1.91, 0 - 27) Unpaid help hour Hours of unpaid help received in the 2 weeks prior to T1 inter- view by up to four unpaid helpers (0 - 1334) 7.64 (40.57, 0 - 684) Medicare Covered by Medicare (yes/no) N = 5282 (99.8%) Medicaid Covered by Medicaid (yes/no) N = 418 (7.95%) Private insurance Covered by private insurance (yes/no) N = 4189 (79.13%) Family income Higher scores indicate higher income (0 = less than $1,000; 26 = $50,000+) 17.12 (6.58, 0 - 26) Disability Factors Functional limitations No. of functional activities (e.g., climbing stairs, bending, lift- ing) unable to performa (0 - 10) 1.95 (2.47, 0 - 10) ADL disabilities No. of ADLs unable to performb (0 - 7) 0.55 (1.31, 0 - 7) IADL disabilities No. of IADLs unable to performc (0 - 8) 0.62 (1.41, 0 - 8) Housing difficulties No. of difficulties entering or leaving home, opening or closing doors, reaching or opening cabinets, using bathroom (0 - 4) 0.21 (0.94, 0 - 4) Unmet need in ADL (0 - 7) Number of ADLs needed more assistance, regardless of whether received support for such activities 0.06 (0.431, 0 - 7) Unmet need in IADL (0 - 8) Number of IADLs needed more assistance in IADL, regardless of whether received support for such activities. 0.08 (0.452, 0 - 6) Note: all data from The Second Longitudinal Study of Aging—The Second Supplement on Aging: 1994 (Version 2, No. 1, September 1998) [Data file]. Hyatts- ville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/otheract/aging/lsoa2.htm. aFrom “An epidemiology of disability among adults in the United States,” by Nagi, 1976, Milbank Memoria l Fund Quarter ly, Vol. 54, No. 4, pp. 439-476. bFrom “Index of ADL,” by Katz and Ak- pom, 1976, Medical Care, pp. 116-118. cFrom “Assessment of older people; self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living,” by Lawton and Brody, 1969, The Gerontologist, Vol. 9, pp. 179-186. 13) Hospice care. HCBS include two types of services, based on service characteristics: nondiscretionary and discretionary. Discretionary services are health services used primarily by individual choice. Homemaker or per- sonal care services (PCS) are examples of discretionary HCBS. In contrast, nondiscretionary HCBS are health services such as skilled nursing care that are used pri- marily on health care providers’ orders or suggestions [14]. Failure to differentiate among services based upon the degree to which they were discretionary might be the reason researchers have generally found need for services to be the most significant predictor of service use [14]. For the purpose of this study, the first five services de- scribed in the paragraph above were considered discre- tionary services; all the other services were considered nondiscretionary services. Except for senior centers and meals at senior center/facility, all of these services were received in the home. Although paid PCS were initially considered discretionary services, older adults who re- ceived these services were less likely to use other types of discretionary services [16,22,27]. Therefore, it is rea- sonable to assume that paid PCS are qualitatively differ- ent from other discretionary services and should be ex- amined in different categories [28]. The question asked at T2 interview for the first 3 com- munity services was, “In the past 12 months, did you go to/use … (the services)?” [29] For the 10 in-home ser- vices, the questions asked were, “Since (month/year of  Factors and Home- and Community-Based Services (HCBS) that Predict Older Adults’ Residential Transitions 372 last interview) did you receive any health care services IN YOUR HOME? This would include skilled nursing care, physical or occupational therapy, assistance with medications or personal care needs, and any other ser- vices provided IN YOUR HOME by a visiting nurse, nursing assistant, home health aide, personal assistant, therapist, or homemaker” and “Which of the following services did you receive? Did you receive (01) Skilled nursing care (02) Physical therapy (03) Occupational therapy (04) Speech therapy (05) Dialysis (06) Tube feeding (07) Personal assistant services (08) Home- maker/companion services (09) Oxygen/respiratory the- rapy (10) Hospice care” [29]. The question asked at T2 interview regarding frequency of service use was, “What was the total number of times you received any of these services in the past 3 months?” [29]. Information about paid PCS services was obtained from respondents’ de- scriptions, at T2 interview, of their four main caregivers who provided ADL or IADL support. Where respondents indicated that caregivers were paid, data were included for analysis. In addition to paid PCS, information re- garding other services used data from the T2 interview data. All these service use between T1 and T2, including at T2. Figure 1 shows residence and service use from T1 interview to T3 interview. As a result, five variables were used to assess older adults’ use of HCBS between T1 and T2: (1) the number of types of discretionary services used between the T1 and T2 interviews, (2) the number of types of nondiscre- tionary services used between the T1 and T2 interviews, (3) the total number of times HCBS used in the three months prior to the T2 interview, (4) number of types of paid ADL PCS received, and (5) number of types of paid IADL PCS received. Table 1 provides detailed descrip- tions of the HCBS-use variables and their distribution in the sample population. About 40.4% of the sample re- ceived HCBS between T1 and T2 (Table 2). 4.3.3. Covariates—Health Behavioral Model Factors The covariates included in this study were based on Anderson’s Health Behavioral Model (HBM). HBM pos- its that people’s use of health services and residential transitions is a function of th eir predisposition to use ser- vices, such as age and gender; the factors that enable or impede their use of services, such as family income and the number of types of unpaid help from friends and fam- ily; and their personal need for care, such as number of difficulties with functional activities, Activities of Daily Living, and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (Please see Table 1 for detailed descriptions of variables included in these factors). 4.4. Analysis Multiple logistic regression procedures were used to iden- tify predictors for different residential transitions. The se- lected variables were consistent with literature findings. Predisposing factors, enabling factors, disability factors, and older adults’ use of HCBS as described in previous sections were used to predict four residential transitions: Figure 1. Older adults’ HCBS use and residential from time 1 to time 3. Table 2. Definition and distribution of home- and community-based ser vic es (HCBS) variables (data from T2 interview). HCBS Variables Operational Definitions Mean (SD, Range) Nondiscretionary services Number of types nondiscretionary services (0 - 8) 0.22 (0.62, 0 - 6) Discretionary services Number of types of discretionary services (0 - 4) 0.47 (0.77, 0 - 4) Personal care services (PCS) Paid ADL PCS Types of ADL assistance received from up to four paid personal care services (0 - 28) 0.24 (1.13, 0 - 18) Paid IADL PCS Types of IADL assistance received from up to four paid personal care services (0 - 32) 0.68 (1.91, 0 - 27) Paid PCS days Days of paid PCS received in the 2 weeks prior to T2 interview by up to four paid helpers () Frequency of HCBS use Total number of times HCBS used in the 3 months prior to T2 interview 2.02 (9.84, 0 - 99) Note: all data from The Second Longitudinal Study of Aging—Wave 2 Survivor Data File (Version SF1.2, June 2002) [Data file]. Hyattsville, MD: National enter for Health Statistics. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/otheract/aging/lsoa2.htm. C Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Factors and Home- and Community-Based Services (HCBS) that Predict Older Adults’ Residential Transitions 373 1) CCC; 2) CIC; 3) CCI; and 4) CII. Odds ratios and pseudo-R2 were reported. The level of significance was set at p 0.05. STATA 9.0 survey suite was used for statistical analysis to address the complex sample design used in LSOA II. 5. Results Among the 5294 older adults included in the current study, there were 4649 (87.8%), 92 (1.7%), 384 (7.3%), Table 3. Descriptive results of older adults in the four resi- dential transition groups. Residential Tr ansition Groups (Mean/Percentage) Predisposing Factors CCC CIC CCICII Age 75.07 77.86 78.2880.22 Education 11.55 11.22 11.0610.12 Size of family 1.87 1.89 1.701.63 Gender (Female %) 61.6% 71.7% 71.1%81.7% Marital status (Married %) 57.5% 45.7% 41.2%42.0% Enabling Factors (Data from T1 Interview) Unpaid ADL help (0 - 28) 0.19 0.72 0.331.27 Unpaid IADL help (0 - 32) 0.55 1.61 1.162.71 Unpaid help hour (0 - 708) 6.26 15.85 12.0834.88 House modification 1.03 1.40 1.421.88 Financial Enabling Factors (From T1 Interview) Medicaid (yes) 97.2% 98.9% 97.4%94.7% Medicaid (yes) 7.6% 6.7% 8.9%14.8% Private insurance (yes/no) 80.5% 81.8% 75%64.5% Family income 17.37 16.90 15.6213.54 Disability Factors (Data from T1 Interview) Nagi’s function limitation (0 - 10) 1.79 3.25 2.744.15 ADL disability (0 - 7)) 0.46 1.23 0.911.95 IADL disability (0 - 8) 0.51 1.29 1.082.26 Difficulty with elders’ house (0 - 4) 0.17 0.53 0.270.73 Unmet need in ADL (0 - 7) 0.04 0.02 0.130.29 Unmet need in IADL (0 - 8) 0.07 0.07 0.140.30 HCBS (Data From T2 Interview) Nondiscretionary services (0 - 8) 0.18 1.08 0.400.93 Discretionary services (0 - 4) 0.44 0.98 0.711.11 HCBS frequency 1.42 10.11 6.3512.08 Paid ADL PCS (0 - 28) 0.05 0.45 0.400.52 Paid IADL PCS (0 - 32) 0.16 0.59 0.470.47 Paid PCS days 0.11 0.33 0.310.30 Note 1: all data from The Second Longitudinal Study of Aging—The Second Supplement on Aging: 1994 (Version 2, No. 1, September 1998); Wave 2 Survivor Data File (Version SF1.2, June 2002); Wave 3 Survivor Data File (Version SF2.1, October 2002) [Data file]. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/other- act/aging/lsoa2.htm. Note 2: Community (C): Home- and community-based settings are settings either in a housing unit or in a facility which provides residents with autonomy and control over their living and service arrange- ments. Institution (I): Residential settings in units that are neither self-con- tained nor self-sufficient are considered institutions and units in such set- tings are often shared by nonrelated residents (including settings like nursing homes and convalescent or rest homes). and 169 (3.2%) in CCC, CIC, CCI, and CII groups re- spectively. Older adults in CCC group were generally younger, having higher education level, bigger family size, and better financial status than older adults in other groups. Older adults in this group also had less physical disabilities and used less HCBS than older adults in other groups. Table 3 provides detailed descriptive informa- tion about older adults in the four groups. 5.1. Factors Predicting Different Residential Transitions Odds ratios generated from a series of logistic regression analysis were reported. Please see Table 4 for details. 5.1.1. CCC Older adults’ probabilities of remaining in community residences from T1 to T3 declined with increases in age (p < 0.001), and number of types of nondiscretionary (p < 0.001) and discretionary services (p < 0.001) used. Older adults’ probabilities of remaining in the commu- nity from T1 to T3 increased with Medicaid coverage (p < 0.05) and private insurance coverage (p < 0.05). The pseudo-R2 was 0.15. 5.1.2. CIC The probabilities of older adults who had been living in communities at T1 returning to communities between T2 and T3 after being in an institution between T1 and T2 declined with Medicaid coverage (p < 0.01) and with increases in HCBS use frequency (p < 0.05) and hours of help from unpaid caregivers (p < 0.01). Older adults’ probabilities of this residential transition pattern in- creased with increase in age (p < 0.05), number of types of unpaid ADL help received (p < 0.05), number of types of nondiscretionary services (p < 0.001) and discretion- ary services used (p < 0.05), and number of paid IADL PCS used (p < 0.05) used. The pseudo-R2 was 0.09. 5.1.3. CCI Older adults’ probabilities of living in their communities between T1 and T2 but in an institution between T2 and T3 declined with increase in number of difficulty with the house that older adults were living (p < 0.01). Older adults’ probabilities of this residential transition in- creased with increase in age (p < 0.001), number of ADLs the sample person perceived needing more help(p < 0.01), number of types of discretionary services used (p < 0.05), and frequency of HCBS use (p < 0.01). The pseudo-R2 was 0.06. 5.1.4. CII Older adults’ probabilities of being in CII group, who lived in their communities at T1 but were admitted to a nursing home at least once between T1 to T2 as well as between T2 to T3, declined with private insurance cov- Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Factors and Home- and Community-Based Services (HCBS) that Predict Older Adults’ Residential Transitions 374 erage (p < 0.01). Older adults’ probabilities of this resi- dential transition increased with increases in age (p < 0.001), and number of types of nondiscretionary (p < 0.001) and discretionary services (p < 0.05) used. The pseudo-R2 was 0.12. 5.2. Summary Older adults who were younger, had Medicaid and pri- vate insurance coverage, and used less types of both dis- cretionary and nondiscretionary services were more likely to continue living in communities over the 6 years of the study period. Older adults who were older, had received more types of unpaid ADL help but less total unpaid hours from unpaid caregivers, and did not have Medicaid coverage were more likely to move into an institution at least temporarily, with the possibility of returning to the community increasing if they used more types of nondiscretionary and discretionary services, used these services infrequently, and purchased more paid IADL PCS. Older adults who were older, perceived less difficulty with the house they were liv ing in, and had more unmet ADL needs seemed to be able to stay in community longer if they used more types of discretion- ary services and purchased more days of PCS. However, these services did not necessarily prevent older adults with these factors from having to move into an institution eventually. Older adults who were older, did not have rivate insurance coverage, and used more types of dis- p Table 4. Odds ratios predicting older adults’ residential transitions. Resid e n ti a l Transi t io n s CCC CIC CCI CII Health Behavioral Model (HBM) Variables OR CI OR CI OR CI OR CI Predisposing Factors Age 0.92*** 0.90 - 0.941.07* 1.01 - 1.121.07*** 1.04 - 1.10 1.10*** 1.05 - 1.16 Education 1.02 0.97 - 1.071.02 0.92 - 1.130.98 0.93- 1.03 0.97 0.87 - 1.07 Family size 1.03 0.88 - 1.210.94 0.63 - 1.390.99 0.81- 1.22 0.92 0.66 - 1.29 Gender 0.83 0.64 - 1.071.42 0.71 - 2.841.06 0.78- 1.45 1.43 0.77 - 2.68 Marital status 0.89 0.65 - 1.231.03 0.91 - 1.161.03 0.91 - 1.16 1.12 0.91 - 1.38 Enabling Factors Unpai d ADL help 0.99 0.86 - 1.131.51* 1.06 - 2.140.85 0.72- 1.01 1.08 0.92 - 1.27 Unpaid IADL help 0.91 0.81 - 1.011.17 0.93 - 1.471.06 0.94- 1.19 1.12 0.98 - 1.29 Unpaid help hour 1.00 1.00- 1.010.98** 0.97 - 0.991.00 0.99- 1.00 1.00 0.99 - 1.00 Medicare 1.17 0.51 - 2.680.88 0.11 - 7.101.17 0.45- 3.03 0.46 0.19 - 1.12 Medicaid 2.07* 1.16 - 3.670.05** 0.01 - 0.310.56 0.31- 1.03 0.60 0.24 - 1.53 Private insurance 1.68** 1.20 - 2.350.52 0.22 - 1.210.81 0.54 - 1.22 0.46** 0.26 - 0.81 Family income 1.00 0.98 - 1.031.02 0.96 - 1.091.00 0.97 - 1.03 0.98 0.94 - 1.02 Disability Factors Functional limitations 1.02 0.95 - 1.101.07 0.91- 1.271.02 0.94 - 1.10 0.91 0.80 - 1.03 ADL disabilities 0.90 0.78 - 1.030.92 0.71- 1.201.12 0.93 - 1.34 1.11 0.89 - 1.39 IADL disabilities 0.95 0.81 - 1.120.79 0.49- 1.271.08 0.91 - 1.27 1.08 0.84 - 1.38 Housing difficulties 1.11 0.89 - 1.401.41 0.80 - 2.480.66** 0.49 - 0.89 1.21 0.86 - 1.71 Unmet ADL needs 0.86 0.65 - 1.120.51 0.18 - 1.431.42** 1.11 - 1.83 0.87 0.51 - 1.50 Unmet IADL needs 1.07 0.82 - 1.400.64 0.25 - 1.640.93 0.70 - 1.24 1.08 0.70 - 1.68 HCBS Variables Nondiscretionary services 0.62*** 0.53 - 0.722.75*** 2.12 - 3.550.95 0.72 - 1.27 1.82*** 1.44 - 2.30 Discretionary services 0.67*** 0.58 - 0.791.39* 1.03 - 1.881.23* 1.04 - 1.46 1.67* 1.12 - 2.48 Personal care services Paid ADL PCS 0.84 0.70 - 1.010.95 0.71 - 1.251.13 0.97 - 1.32 1.07 0.85 - 1.34 Paid IADL PCS 1.03 0.80 - 1.321.28* 1.01 - 2.060.84 0.66 - 1.06 1.00 0.75 - 1.33 Paid PCS days 0.70 0.46 - 1.060.87 0.38 - 2.012.15*** 1.53 - 3.03 0.66 0.33 - 1.31 Frequency of HCBS use 0.99 0.98 - 1.000.96* 0.92 - 0.991.02** 1.01 - 1.03 1.00 0.99 - 1.02 Pseudo-R2 0.15 0.09 0.06 0.12 Note: CCC: fro m communit y (1994) to co mmunity (199 8) to co mmunity (2000 ); CIC: fr om community t o institu tion and back to commun ity; CCI: from com- munity to community to institution; *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001; a. Paid ADL help was dropped from analysis in the CIC group due to too little cases and variation in older adults’ responses. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Factors and Home- and Community-Based Services (HCBS) that Predict Older Adults’ Residential Transitions 375 cretionary and nondiscretionary services were more likely to demonstrate a CII transition pattern, which indicated more frequent or even long term use of institutional ser- vices. Table 4 summarizes the predictors of older adults’ residential transitions. 6. Discussion This study contributes to health services research by examining which older adults’ personal factors and HCBS use predict their residential transitions. The CCC transition revealed factors supporting older adults to con- tinue staying in co mmunities. Th e CIC transitions gener- ated information about what factors contribute to older adults moving back to their communities after having been institutionalized. The CCI transitions provided in- formation about what factors contribute to older adults remaining in their communities longer before needing an institution. The fourth type of transition, CII, indicated factors that resulted in older adults’ frequent or long-term use of institutional services. Past research focused on knowing whether services predicted nursing-home ad- missions, yet understanding the various ways HCBS af- fect residential transitions for older adults with different characteristics will be even more important for policy makers. Our study findings pointed to predictors of different transitions, providing the first evidence showing differ- ential impacts of different older adults’ personal factors and different HCBS use on older adults’ residential tran- sitions. Different types and frequency of HCBS use pre- dicted different patterns of residential transitions. In ad- dition to validating Jette and colleagues’ suggestion that future research should examine the impact of specific types of community care and provide further information about the possible different effects of different HCBS [6], our findings, also pointed out the importance of consid- ering older adults’ residential transitions when studying the effects of HCBS. The following discussion integrates and compares the findings to provide a broader picture of the ways these factors influence older adults’ residential transitions. 6.1. Older Adults’ Personal Factors and Their Residential Transitions Findings regarding older adults’ personal factors echoes literature findings that being older is more likely to posi- tively predict their transition to nursing home [6,8,30]. However, several factors identified in the literature that predicted older adults’ nursing home admission did not significantly predict older adults’ different residential transitions, such as income and physical disabilities [3]. These findings showed that older adults’ personal factors predicting older adults’ residential transitions are differ- ent from the factors predicting nursing home use. The literature has reported having more informal sup- port to be both associated with and not associated with increased risk of nursing home admission [1,18,31]. Our study findings provided further explanation: that lack of informal support could predict older adults’ nursing- home admission, but not older adults’ residential transi- tions. It is possible that the effect of informal support was attenuated when all types of nursing-home use were combined. Our findings indicated that having such sup- port seemed to enable older adu lts to return to communi- ties after being institutionalized. In the current study, older adults who had more types of help for ADL dis- abilities from unpaid caregivers were more likely to re- turn to community, ev en after being admitted to an insti- tution, as did the older adults in the CIC group. Although having such informal support could be associated with the use of institutional services, older adults’ use of in- stitutional services could just be temporary. However, our study findings also indicated the impor- tance of not relying on the total amount of informal care, as even using different types of ADL informal support appeared to be a beneficial factor for older adults to re- turn to communities. It is possible that having informal support, but not becoming too dependent on the amount of informal support, is a key for older adults to return to communities after being institutionalized. Policy makers are seeking factors that will enable older adults to return to communities [2]. Our study findings provide informa- tion that will help community care professionals better identify the characteristics of older adults who have the potential to return to and remain in communities after being institution a lized. Our study findings regarding insurance coverage con- tradicted the literature findings that Medicaid coverage was associated with higher risk of nursing-home place- ment [18]. In the current study, our findings indicated that having Medicaid coverage seems to be a factor that supports older adults to remain in community settings. Older adults with Medicaid and private insurance cover- age were more likely to be in the CCC transition group, which continued living in communities over the 6 years of the study period. Older adults who did not have Medi- caid coverage had a higher probability of being in the CIC group, whose members were also admitted to a nursing home, at least temporarily. This finding may be attributable to the effort and ac- complishment of Medicaid HCBS waivers. Miller and colleagues’ study (2000) analyzed data collected between 1985 and 1998, when HCBS services were only starting to be developed . Our study used data from 1994 to 2000, which allowed time to see the effects of HCBS and espe- cially of Medicaid HCBS waivers, which passed in 1995. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Factors and Home- and Community-Based Services (HCBS) that Predict Older Adults’ Residential Transitions 376 A recent systematic review study also reported Medicaid coverage as a factor preventing older adults from nursing home admission [3]. Chen’s study (2004) revealed that being covered by Medicaid was significantly predictive of discretionary services use. This finding reflects the Medicaid HCBS waivers implemented in 1995 and shows that the HCBS waivers encouraged the use of dis- cretionary services use by elders and, therefore, provided older adults with Medicaid coverage with higher prob- abilities to be in communities [32]. In the current study, we further found that having Medicaid coverage plus private insurance seemed to provide older adults with extra support to stay in communities, as were CCC group. Older adults who did not have private insurance coverage were more likely to be in CII group. 6.2 HCBS and Older Adults’ Residential Transitions Findings from the four groups of older adults provided potential exp lanations for the inconsistent findings in the literature regarding the effect of HCBS use among older adults, and the types of HCBS that may assist older adults with different characteristics to achieve different residential transitions. Findings from the CCC and CII groups were consistent with literature findings in that HCBS use is likely to positively predict transition to a nursing home [8,24]. However, findings from the CIC and CCI groups showed different messages. Findings from these two groups may provide further information on how HCBS influences nursing-home use for particular groups and reveal information regarding which HCBS might support older adults with specific characteristics to return to communities after institutionalization or to stay in communities longer. (Eng, Pedulla, Eleazer, McCann, & Fox, 1997; Jette et al., 1995; G. Mitchell, 2nd, Salmon, Polivka, & Soberon-Ferrer, 2006). The key for older adults’ ability to return to commu- nity may be wide-ranging use of HCBS without reliance on the total amount of services. The older adults in the CIC group used HCBS infrequently, yet they used more types of discretionary and nondiscretionary services than did adults in the other groups, and purchased more paid IADL PCS. This pattern may indicate use of services as a functional bridge to support a transition back to living in community. The effect of using HCBS frequently together with using more types of discretionary services may be to en- able older adults to remain in communities lo nger before what seems to be inevitable nursing-home admission in the future. Older adults in the CCI group used more types of discretionary services, but needed to use HCBS fre- quently and to purchase more paid PCS days. This pat- tern of services use indicates greater dependence on the amount of these services, and therefore greater likelihood of moving into more-dependent housing, such as a skilled nursing home, at a later time. Paid PCS stands out as an important service for ena- bling older adults to move back into community from an institution, or to remain in community longer before be- ing admitted to an institution. The CII group of older adults, who became more frequent or long-term users of institutions, used HCBS but did not purchase paid PCS. Chen and colleagues (2010) used structural modeling to test a HCBS model and also reported that using paid IADL PCS significantly supported older adults to remain in communities. The current study further revealed that paid PCS helped older adults to remain in communities through two types of residential transitions, CIC and CCI. However, the effects of purchasing paid PCS are condi- tional to the presence of other key factors, such as infor- mal support. Older adults in the CIC group received in- formal support for ADL disabilities and formal support for IADL disabilities. This seemed an effective strategy for supporting older adults to return to communities. Without informal support, older adults might be more likely to transit from communities to institution, as did the CCI group discussed earlier. A policy research study reported that in the United States, HCBS effects were conditional on older adults having a child available to provide support [33]. This supports our study findings, which indicated that HCBS would generate greater ef- fects for older adults who had unpaid or informal helpers available. Older adults in th e CCI group, unlike those in the CIC group, did not have significant support from unpaid helpers. To meet their needs, they h ad to rely entirely on formal services, and they used these services in larger amounts. Yet using formal services, even in large amounts, seemed insufficient to older adults’ needs. Older adults in the CCI group perceived higher unmet need, which could result in subsequent nursing-home use after managing to remain in communities for a longer time. The amount of paid PCS used provided information for predicting older adults’ future transitions. Using more types of paid PCS, but in small amounts, would enable older adults to return to communities after being institu- tionalized (CIC). Increased need for q uantity of pa id PCS would indicate nursing-home services might be needed in the near future (CCI). Frequency of HCBS use is another key for predicting older adults’ transitions. Older adults in the CIC group used HCBS infrequently, while older adults in the CCI group used HCBS more frequently. In summary, HCBS may not be sufficient to keep older adults in communities, but could support older adults to return to communities or remain in communities longer. Infrequent use of HCBS tog ether with paid IADL Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Factors and Home- and Community-Based Services (HCBS) that Predict Older Adults’ Residential Transitions 377 PCS could be effective in supporting older adults to re- turn to communities, especially for those older adults with better informal support systems. Discretionary ser- vices and paid PCS could be more effective for support- ing older adults without informal support to remain in communities longer. These older adults may rely on a greater quantity of HCBS and paid PCS. When perceived unmet needs increase, institution admission seems inevi- table. Among older adults, higher frequency of HCBS use or greater amount of paid PCS used could be indica- tors of needing more intensive care. 6.3. Policy Implications The take-home message from these findings is to inte- grate informal and formal care systems and to pay atten- tion to the frequency of community-dwelling older adults’ HCBS use and the amount of their paid PCS use, as a guide for possible future transitions. Mor and col- leagues (2007) r eported that between 4% and 12% of the 1.4 million long-stay nursing-home residents, and similar proportions of new admissions, could live in communi- ties rather than in the nursing homes they live in now. However, transferring these older adults back to commu- nity will require well-developed community-based alter- native care systems. Findings from the current study pro- vide valuable insights for policy makers and suggest that if governments intend to help older adults transfer back to their commun ities, the priority services to develop and make available are HCBS services and paid IADL PCS. In the meantime, governments should train community care professionals to pay attention to older adults’ fre- quency of HCBS use and quantity of paid PCS use. Community care professionals could suggest that older adults known to use HCBS frequently or to use large amounts of paid PCS move to more-dependent housing, at least temporarily. On-time referrals could both help older adults and decrease potentially unnecessary use of HCBS in communities. However, the benchmarks of us- ing HCBS “frequently” and of using paid PCS in “large amounts” merit further investigation. 7. Limitations The sample included in this study was less disabled than the overall population included in LSOA II. LSOA II respondents who did not participate in T2 and T3 surveys due to death were not included in this analysis; these were the older adults likely to be more disabled. There- fore, the current study’s findings may be generalizable only to less disabled older adults, and promoting paid PCS may be a suitable strategy only when targeting the less disabled older adults in communities. Future studies should consider Heckman’s (1979) two-stage method to correct the potential sampling bias. Another limitation is that the data for the older adults in the CIC group could not specify whether their use of HCBS occurred before or after their use of nursing home services. With further analysis of a small subgroup (N = 20) of older adults who had used HCBS services before institutionalization and were later able to return to com- munity, we found factors similar to the factors found predicting th e CIC transition in the current stu dy, such as age, Medicaid coverage, unpaid IADL help, and less frequent use of HCBS. However, a further study to ex- amine the timeline of older adults’ HCBS use and insti- tutionalization, u sing a different database, is merited. 8. Conclusions Previous study findings regarding the effects of HCBS on institution use were unclear and inconsistent [5,6,34]. Our findings provide an explanation that addresses the way HCBS influences older adults’ residential tran sitions as well as the magnitude of the effect of appropriately targeted HCBS use. The findings from the current study also support Greene, Lovely, and Ondrich’s (1993) con- clusion that appropriate targeting of HCBS would to some degree reduce institution use and expenditures; the service important to target is PCS support. As baby boomers enter retirement, needs for long-term care for older adults will increase dramatically. It is clear that neither formal services nor informal care can meet the needs of this growing population. Long-term care financing and policy should reflect the capacity of the system to serve older adults in communities. It is there- fore pertinent to reconceptualize the linkages between HCBS and institutional services, and between formal service use and informal care, based upon older adults’ characteristics, and then to move toward an integrative model. The residential transition variables included in the current study allow us to describe not only factors that support older adults’ ability to remain in communities, but also factors that support older adults’ ability to return to communities from institutions, or to remain in com- munities longer before entering an institution. These findings could inform future policy making and devel- opment of better public and private financing strategies for HCBS. Studies have already shown that HCBS cost less than institutional care [35]. Knowing what services best support older adults in different circumstances might further our ability to control costs REFERENCES [1] R. J. Hanley, et al., “Predicting Elderly Nursing Home Admissions. Results from the 1982-1984 National Long- Term Care Survey,” Research on Aging, Vol. 12, No. 2, 1990, pp. 199-228. doi:10.1177/0164027590122004 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Factors and Home- and Community-Based Services (HCBS) that Predict Older Adults’ Residential Transitions 378 [2] V. Mor, et al., “Prospects for Transferring Nursing Home Residents to the Community,” Health Affairs, Vol. 26, No. 6, 2007, pp. 1762-1771. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.26.6.1762 [3] J. E. Gaugler, et al., Predicting Nursing Home Admission in the US: A Meta-Analysis,” BMC Geriatrics, Vol. 7, 2007, p. 13. doi:10.1186/1471-2318-7-13 [4] A. B. Akamigbo and F. D. Wolinsky, “Reported Expecta- tions for Nursing Home Placement among Older Adults and Their Role as Risk Factors for Nursing Home Ad- missions,” The Gerontologist, Vol. 46, No. 4, 2006, pp. 464- 473. doi:10.1093/geront/46.4.464 [5] V. L. Greene, et al., “Reducing Nursing Home Use through Community Long-Term Care: An Optimization Analysis,” The Journal of Gerontology: Series B, 1995, Vol. 50, No. 4, pp. S259-S268. doi:10.1093/geronb/50B.4.S259 [6] A. M. Jette, S. Tennstedt and S. Crawford, “How does Formal and Informal Community Care Affect Nursing Home Use?” The Journals of Gerontology: Seri es B, Vol. 50, No. 1, 1995, pp. S4-S12. doi:10.1093/geronb/50B.1.S4 [7] L. R. Fischer, et al., “Community-Based Care and Risk of Nursing Home Placement,” Medical Care, Vol. 41, No. 12, 2003, pp. 1407-1416. doi:10.1097/01.MLR.0000100587.51573.7A [8] S. McFall and B. H. Miller, “Caregiver Burden and Nurs- ing Home Admission of Frail Elderly Persons,” The Jour- nals of Gerontology, Vol. 47, No. 2, 1992, pp. S73-S79. [9] C. Eng, et al., “Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE): An Innovative Model of Integrated Geriatric Care and Financing,” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, Vol. 45, No. 2, 1997, pp. 223-232. [10] G. Mitchell 2nd, et al., “The Relative Benefits and Cost of Medicaid Home- and Community-Based Services in Florida,” The Gerontologist, Vol. 46, No. 4, 2006, pp. 483-494. doi:10.1093/geront/46.4.483 [11] K. F. Ferraro and J. A. Kelley-Moore, “A Half Century of longitudinal Methods in Social Gerontology: Evidence of Change in the Journal,” The Journals of Gerontology: Se- ries B, Vol. 58, No. 5, 2003, pp. S264-S270. doi:10.1093/geronb/58.5.S264 [12] R. Andersen and J. F. Newman, “Societal and Individual Determinants of Medical Care Utilization in the United States,” The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly, Health and Society, Vol. 51, No. 1, 1973, pp. 95-124. doi:10.2307/3349613 [13] R. M. Andersen, “A Behavioral Model of Families’ Use of Health Services,” Research Series, University of Chi- cago, Center for Health administration Studies, Chicago, 1968. [14] R. M. Andersen, “Revisiting the Behavioral Model and Access to Medical Care: Does It Matter?” Journal of Health and Social Behavior, Vol. 36, No. 1, 1995, pp. 1-10. doi:10.2307/2137284 [15] J. A. Krout, J. Oggins and H. H. Holmes, “Patterns of Service Use in a Continuing Care Retirement Commu- nity,” The Gerontologist, Vol. 40, No. 6, 2000, pp. 698-705. doi:10.1093/geront/40.6.698 [16] J. Mitchell and J. A. Krout, “Discretion and Service Use among Older Adults: The Behavioral Model Revisited,” The Gerontologist, Vol. 38, No. 2, 1998, pp. 159-168. doi:10.1093/geront/38.2.159 [17] R. Andersen, et al., “Application of the Behavioral Model to Health Studies of Asian and Pacific Islander Ameri- cans,” Asian American and Pacific Islander Journal of Health, Vol. 3, No. 2, 1995, pp. 128-141. [18] E. A. Miller and W. G. Weissert, “Predicting Elderly People’s Risk for Nursing Home Placement, Hospitaliza- tion, Functional Impairment, and Mortality: A Synthesis,” Medical Care Research and Review, Vol. 57, No. 3, 2000, pp. 259-297. doi:10.1177/107755870005700301 [19] C. Mustard, et al., “What Determines the Need for Nurs- ing Home Admission in a Universally Insured Popula- tion?” Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, Vol. 4, No. 4, 1999, pp. 197-203. [20] M. Tomiak, et al., “Factors Associated with Nurs- ing-Home Entry for Elders in Manitoba, Canada,” The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, Vol. 55, No. 5, 2000, pp. M279-M287. doi:10.1093/gerona/55.5.M279 [21] D. Lekan-Rutledge, “Functional Assessment,” In: M. A. Matteson, E. S. McConnel and A. D. Linton, Ed., Geron- tological Nursing: Concepts and Practice, Sounders Company, Philadelphia, 1998. [22] R. J. Johnson and F. D. Wolinsky, “Use of Community- Based Long-Term Care Services by Older Adults,” Jour- nal of Aging and Health, Vol. 8, No. 4, 1996, pp. 512-537. doi:10.1177/089826439600800403 [23] S. C. Miller, et al., “Time to Nursing Home Admi ssion for Persons with Alzheimer’s Disease: The Effect of Health Care System Characteristics,” The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Vol. 53, No. 6, 1998, pp. S341-S353. doi:10.1093/geronb/53B.6.S341 [24] S. J. Newman, et al., “Overwhelming Odds: Caregiving and the Risk of Institutionalization,” The Journals of Gerontology, Vol. 45, No. 5, 1990, pp. S173-S183. [25] The Second Longitudinal Study of Aging, The Second Supplement on Aging: 1994 (Version 2, No. 1, September 1998); Wave 2 Survivor Data File (Version SF1.2, June 2002); Wave 2 Decedent Data File (Version DF1.1, Au- gust 2002); Wave 3 Survivor Data File (Version SF2.1, October 2002); Wave 3 Decedent Data File (Version DF2.1, December 2002) 2002 [cited 2002; Data files]. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/otheract/ aging/lsoa2.htm. [26] K. G. Jöreskog and D. Sörbom, “LISREL8: Structural Equation Modeling with the SIMPLIS Cammand Lan- guage,” Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, 1993. [27] P. Kemper, “The Use of Formal and Informal Home Care by the Disabled Elderly,” Health Services Research, Vol. 27, No. 4, 1992, pp. 421-451. [28] V. L. Greene, M. E. Lovely and J. I. Ondrich, “The Cost-Effectiveness of Community Services in a Frail Elderly Population,” The Gerontologist, Vol. 33, No. 2, 1993, pp. 177-189. doi:10.1093/geront/33.2.177 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Factors and Home- and Community-Based Services (HCBS) that Predict Older Adults’ Residential Transitions Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM 379 [29] The Second Longitudinal Study of Aging, The Second Supplement on Aging: Wave 3 Survivor Questionnaire (Version SF2.1, October 2002) 2002 [cited 2002; Coding Book files]. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ about/otheract/aging/lsoa2.htm. [30] Q. Cai, J. W. Salmon and M. E. Rodgers, “Factors Asso- ciated with Long-Stay Nursing Home Admissions among the US Elderly Population: Comparison of Logistic Re- gression and the Cox Proportional Hazards Model with Policy Implications for Social Work,” Social Work in Health Care, Vol. 48, No. 2, 2009, pp. 154-168. doi:10.1080/00981380802580588 [31] R. F. Boaz and C. F. Muller, “Predicting the Risk of ‘Permanent’ Nursing Home Residence: The Role of Community Help as Indicated by Family Helpers and Prior Living Arrangements,” Health Services Research, Vol. 29, No. 4, 1994, pp. 391-414. [32] Y. M. Chen, “A Community-Based Long-Term Care Model for the US Elderly,” Doctoral Dissertation, Uni- versity of Washington, Seattle, 2004, p. 258. [33] N. Muramatsu, et al., “Risk of Nursing Home Admission among Older Americans: Does States’ Spending on Home- and Community-Based Services Matter?” The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Vol. 62, No. 3, 2007, pp. S169-S178. [34] D. J. Rabiner, S. C. Stearns and E. Mutran, “The Effect of Channeling on in-Home Utilization and Subsequent Nurs- ing Home Care: A Simultaneous Equation Perspective,” Health Services Research, Vol. 29, No. 5, 1994, pp. 605- 622. [35] M. Kitchener, et al., “Institutional and Community-Based Long-Term Care: A Comparative Estimate of Public Costs,” Journal of Health & Social Policy, Vol. 22, No. 2, 2006, pp. 31-50. doi:10.1300/J045v22n02_03

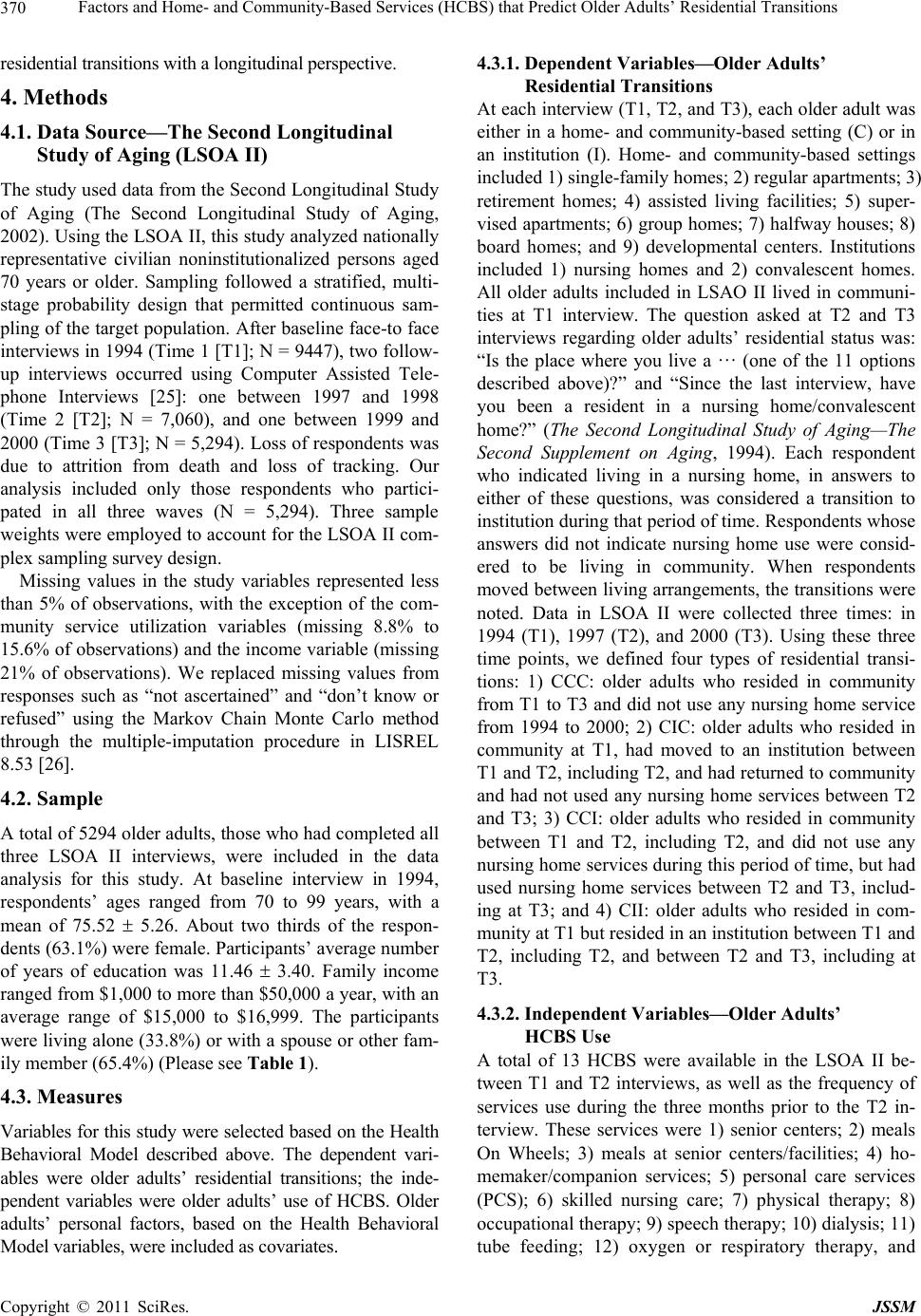

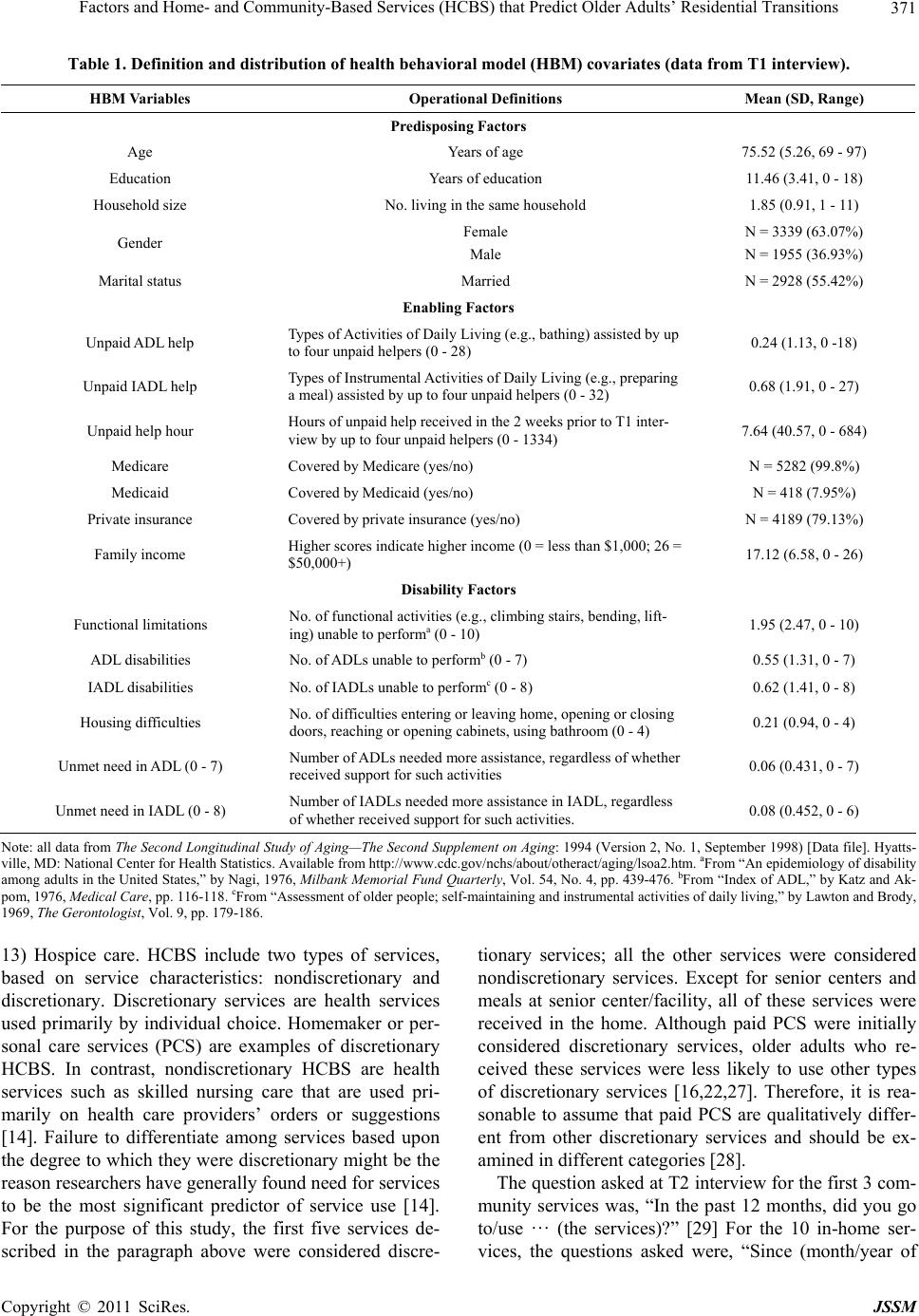

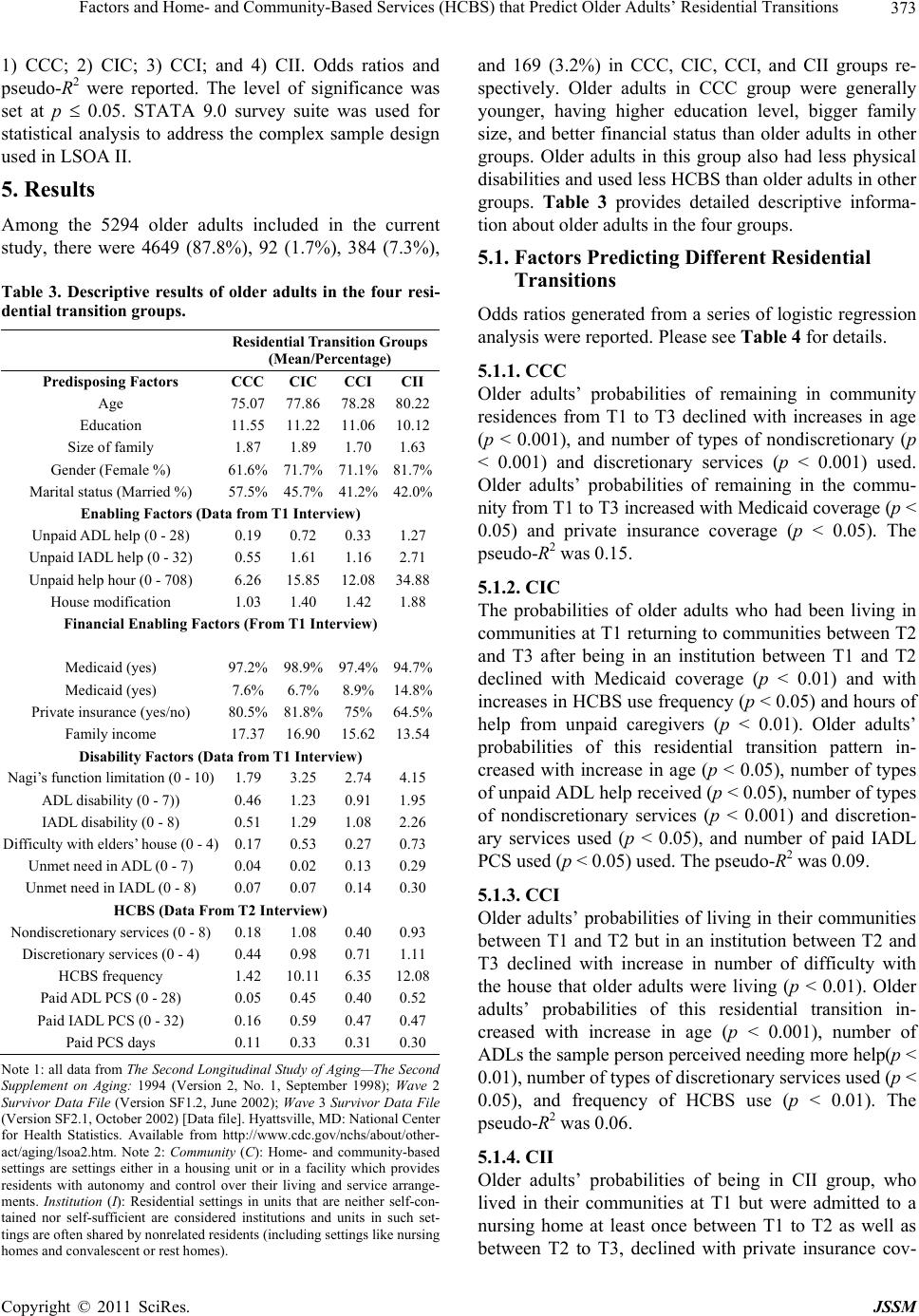

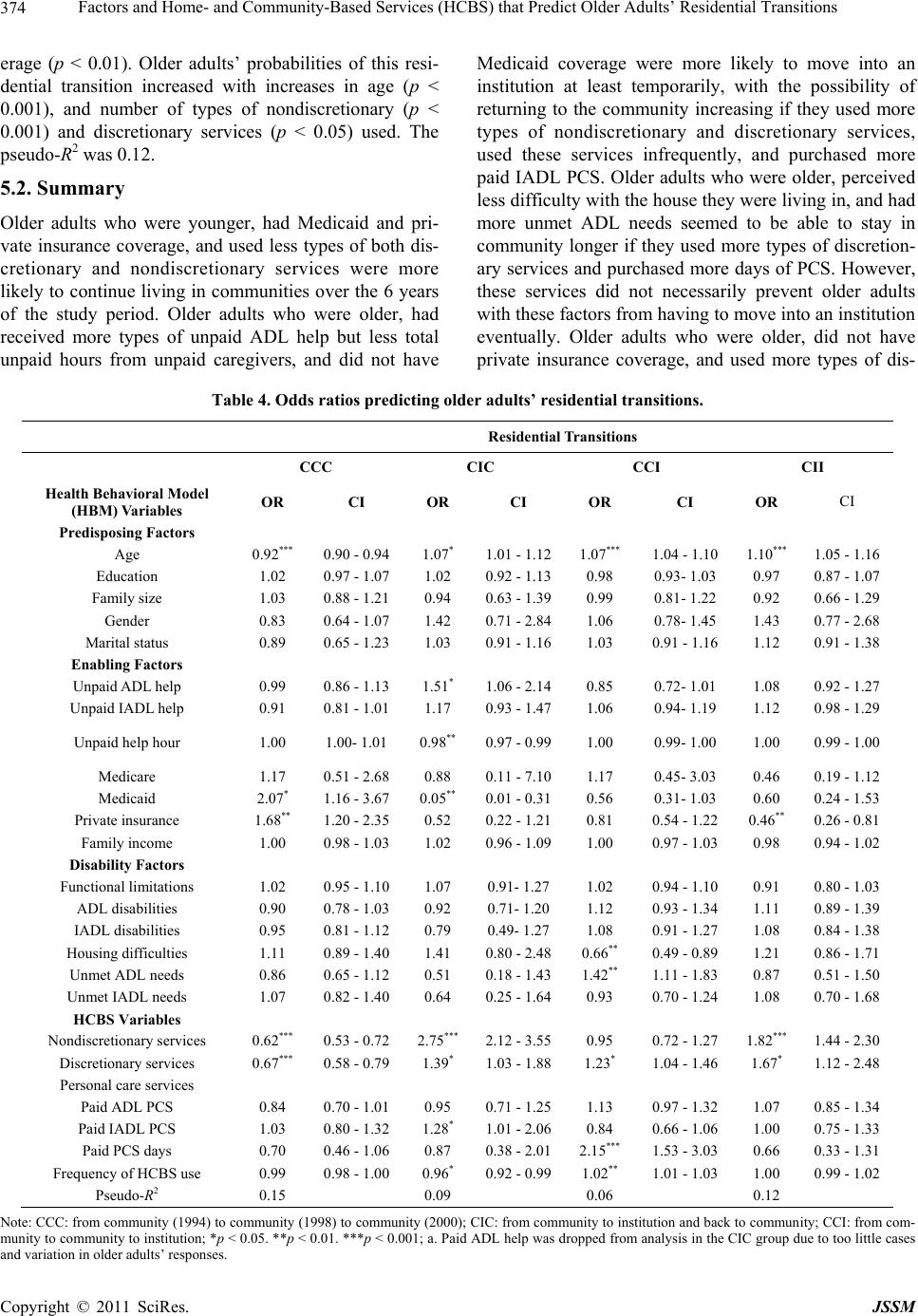

|