Journal of Service Science and Management, 2011, 4, 268-279 doi:10.4236/jssm.2011.43032 Published Online September 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jssm) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM Converting Traditional Production Systems to Focused Cells as a Requirement of Global Manufacturing Ibrahim H. Garbie Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering, Sultan Qaboos University, Muscat, Oman. Email: garbie@squ.edu.om Received January 30th, 2011; revised April 20th, 2011; accepted May 12th, 2011. ABSTRACT The converting process from trad itional production systems (e.g., Job Shops) to focu sed (cellular) systems is important as one requirement of global manufacturing to challenge the existing global financial crisis. This represents a big problem and a huge task for manufacturers and academicians which almost most of industrial enterprises around the world are still working as a job shop. This converting process means breaking or dividing the existing functional (process) layout into independently and distinctly focused manufacturing cells to gain on the conversion benefits. To consider this issue, a new methodology of converting job shops into cellular systems is introduced based on the re- quirements of global manufacturing regarding manufacturing systems design only. These requirements are: respon- siveness, reconfigurable machines, mass customization, innovative and manufacturing systems configuration. A com- plete industrial case study will be used to analyze and explain the proposed methodology in a small-sized job shop manufacturing firm. Keywords: Reconfigurable Manufacturing Systems, Cellular Manufacturing Systems, Cell Formation. 1. Introduction Due to an increasingly competitive global market, the need for shorter product life cycles and time to market, and diverse customers, changes in manufacturing sys- tems have been tried to improve the flexibility and pro- ductivity of manufacturing systems. There are three dif- ferent types of manufacturing systems: flow shop (mass production) system, batch production system, and job shop manufacturing system. The job shop manufacturing system is characterized by high flexibility and low pro- duction volume and uses general-purpose machines. The flow shop manufacturing system has less flexibility due to dedicated machine tools but more production volume is valuable. Due to the limitations of job shop and flow shop systems to accommodate fluctuations in product demand and production volume, manufacturing systems are often required to be reconfigured to respond to changes in product design, introduction of a new product, and change in product demand and volume. As a result, cellular manufacturing systems (CMS) have emerged as promising alternative manufacturing systems to deal with these issues especially for next period as a competence for the global manufacturing as one solution to solve this crisis in industrial enterprises [1]. CMS design is an important manufacturing concept involving the application of group technology and it can be used to divide a manufacturing facility into several groups of manufacturing cells. This approach means that similar parts are grouped into part families and associ- ated machines into machine cells, and that one or more part families can be processed within a single machine cell. The creation of manufacturing cells allows the de- composition of a large job shop manufacturing system into a set of smaller and more manageable subsystems. There are several reasons for converting traditional manufacturing system (e.g., Job Shop systems) into cel- lular systems. These reasons include reduced work-in- process (WIP) inventories, reduced lead times, reduced lot sizes, reduced inter-process handling costs, better overall control of operations, improved efficiency and flexibility, utilized space, reduced operation costs, im- proved product design and quality, and reduced setup times. General descriptions of group technology and cel- lular manufacturing systems, cell formation techniques,  Converting Traditional Production Systems to Focused Cells as a Requirement of Global Manufacturing269 and an extensive review of the various aspects adopted for cellular manufacturing systems are discussed care- fully in the literature review [2]. Always, a new product is requested and demanded at low price with high quality and highly customized (mass customization). For surviving in the globalization, a new configuration of the manufacturing systems lead to launch new products to market replacing old ones com- peting in low prices and high quality. So, the reconfigu- ration from Job shop system to cellular systems has be- come an issue of core competence. Reconfigurable Job Shop manufacturing systems must take into account the mass customization requirements which they can cope with unpredictable environment changes to adapt with productivity and flexibility issues to change their con- figuration and physical layout. Resources (e.g., machines, material handling equipments, etc.) should be adjusted and composed in a changeable structure. These resources should be modular machines such as: CNC machines and/or reconfigurable machine tools [3]. Usually, the Job shop manufacturing systems cannot be completely divided into focused cells. Reasonably, a portion of the Job shop facility remains as a large espe- cially in mid-sized and large-sized systems. Functional job shop system that has been termed the “functional or reminder cell” and the cellularization may be less than 100% [4,5] and around 60% [6]. The entire manufactur- ing system cannot be completely converted into cellular cells and typically around 40% - 50% of total production system can be transferred [7]. Hybrid organizations for next period which consist of functional departments and manufacturing cells were recommended [8]. The main objectives of reconfiguring existing Job shop manufac- turing systems into cellular systems are system perform- ance measures (productivity and flexibility) to satisfy market demand and management goals. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the research mainly related to conver- sion from job shop manufacturing systems to cellular systems and manufacturing cells formation. The global- ization issues will be discussed in Section 3. Section 4 presents the proposed conversion. A complete industrial case study will be explained with the results and discus- sion in Section 5. The conclusions and recommendations for further work are given in Section 6. 2. Literature Review There are significant amounts of literature review dedi- cated to the design of cellular manufacturing systems (CMS) over the last four decades since 1973. Conversion from an existing job shop manufacturing system to a cellular manufacturing system was presented through modeling and economic analysis by SIMAN software simulation package [9]. The production flow analysis was used to convert job shops to manufacturing cells [10]. Benefits and limitations due to conversion from a func- tional layout to a cellular layout were presented [11]. A bi-criterion technique based on the flexibility and effi- ciency in converting functional manufacturing systems into cellular manufacturing systems was presented [12]. Redesigning functional production systems into cellular systems was mentioned through similarity order cluster- ing between machines [13]. Improving productivity through converting job shops manufacturing systems to cellular systems using optimal layout configuration [14]. The reconfiguration costs and times were approximately estimated. A lot of cell formation techniques were rec- ommended to convert job shops manufacturing system to cell systems [15]. A pragmatic approach was proposed to grouping ma- chines and parts in CMS to achieve cell independence as a goal function [16]. A simulated annealing was pre- sented to minimize cell load imbalance and extra capac- ity required [17] while the simulating annealing was used to increase the productivity in CMS [18]. A clustering approach based on similarity coefficient which includes production sequence and product volumes to form a manufacturing cell [19,20]. Branching rules to group machines into machine cells and parts into part families was used [21]. A heuristic approach for cell formation was suggested to generate manufacturing cells [22]. Mathematical programming techniques were used to form cell formation incorporating machine capacity, al- ternative routing and identical machines to achieve cell independence [23,24]. A heuristic cell formation incor- porating alternative routing, operation sequence, proc- essing times, production volume, and machine capacity was presented [25]. New similarity coefficients were proposed to group parts into independent flow-line fami- lies considering machine capabilities and operations se- quences [26]. A mathematical programming technique was presented to form manufacturing cells by consider- ing alternative routing and identical machines [27]. A integer programming to minimize intercellular move- ments and machine costs considering multiple time peri- ods was developed [28,29]. A flexible cell formation approach was presented by considering routing and de- mand flexibility [30]. Operations sequence to minimize cost of materials flow and capital investment for design- ing CMS was used [31]. Average linkage clustering algorithm for grouping parts (products) into part (product) families was used [32, 33]. They considered effectiveness of a Reconfigurable Manufacturing System (RMS) depends on the formation of best set of product families. The reconfiguration issues in manufacturing systems were introduced mainly on Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Converting Traditional Production Systems to Focused Cells as a Requirement of Global Manufacturing 270 reconfiguring existing cellular system to another cells taking into consideration system utilization and through- put [34]. A reconfiguration link was suggested to inter- face between market requirements and manufacturing facilities to group products into families and select the appropriate family at each configuration stage [35]. A routing flexibility was used as a contingency process routings in formation of manufacturing cells versus addi- tional costs of duplicate machines [36,37]. Axiomatic design (AD) and experimental design (ED) are used as a framework to complete cellular manufacturing system design [38] to generate several feasible and potentially profitable designs. A new methodology was presented to optimize resource through balancing the workload in designing cellular manufacturing systems as a solution for flow shop environments [39]. The design of CMS based on tooling requirements of the parts and tooling available on the machines was proposed and presented [40]. A traditional clustering formula to evaluate the ef- fectiveness of cell formation as a performance measure was used [41]. Machine reliability through alternate routing process versus transporting, operating, and un- derutilized costs is suggested in design of CMS [42,43]. Although there are a myriad of optimal cell formation techniques proposed to cell design, they none seem to address the most of relevant globalization issues or on the other words, most of the research works done in this field has been focused on clustering or forming rather than converting from existing job shop manufacturing systems. In this paper, a comprehensive converting approach from functional and/or process layout to cellular layout will be introduced incorporating the most important glob- alization issues regarding manufacturing systems design. Also, practical performance measuring will be evaluated. 3. Globalization Issues Several relevant globalization issues should be taken into consideration when designing global manufacturing sys- tems and/or as a requirement of converting functional cells into focused cells. These issues are discussed as follows: 3.1. Responsiveness Responsiveness is the time required by a machine to perform an operation on a part type. Sometimes, respon- siveness is considered as a manufacturing lead time. Normally, set up time and processing times are included in manufacturing lead time. The processing time should be provided for every part (product) on corresponding machines in the operation sequence. Processing time is important because it is used to determine resource (ma- chine) capacity requirements [2]. Hence, ignoring the processing times may violate the capacity constraints and thus lead to an infeasible solution [44]. 3.2. Reconfigurable Machines Manufacturing systems use reconfigurable machines representing in components and architecture which can offer a much greater range of options to manufacturers. Reconfigurable machines are considered into two main issues: machine capacity and machine capability. 3.2.1. Machin e Capaci t y Machine capacity is the amount of time a machine of each type is available for production in each period. When dealing with maximum possible demand, we need to consider whether the resource capacity is violated or not. In the design of cellular systems for reconfiguration, available capacities of machines need to be sufficient to satisfy the production demand [2,43]. Machine capacity is more important and it should be ensured that is more adequate capacity (in machine hours) is available to process all the part families [45]. The importance of ma- chine capacity is being rapidly adjusted to fluctuations in changing product demand. 3.2.2. Machine Capability Machine capability refers to the functionality of ma- chines to perform varying operations without incurring excessive cost from one operation to another. The ma- chine level is fundamental to a manufacturing system, and machine flexibility is a prerequisite for most other flexibilities as mentioned by [1,30,45]. 3.3. Innovation Introducing a new product or product design and devel- opment (modification) represents a new concept when the CMS should be designed. Although they carry over- lapping definitions to design CMS, incorporating one of them will develop concepts of CMS from traditional ideologues to advanced ideologues (agile systems) [46, 47]. To achieve these new concepts, reconfiguring tradi- tional job shop systems into cellular systems with cus- tomized flexibilities is highly desired. As the reconfigu- ration manufacturing systems is one of most important strategies in achieving agility in the manufacturing sys- tems, reconfiguring or reorganizing not only the tradi- tional job shop systems but also the cellular system [43]. Introducing a new product or changing in existing prod- uct design (product development) will base on the ma- chine flexibility and machine reliability. 3.4. Mass Customization Demand is the quantity of each product in the product mix to be produced in each period. The product demand of each product is expected to vary across the planning Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Converting Traditional Production Systems to Focused Cells as a Requirement of Global Manufacturing271 horizon. Changing in product demand and the variability in parts demands lead the designers of manufacturing systems to convert the job shop systems to cellular sys- tems. Mass customization does not mean producing one of a kind product but to producing relatively large quan- tities of varieties of products from the same product fam- ily at mass production competitive of economics scale. The goal of mass customization is to increase customer's value of a product by adding a range of product varia- tions that fit specific customer's taste and needs while maintaining low prices [48]. Producing products for mass customization presents a challenge because of substantial changes in product flexibility and product volume (de- mand). 3.5. Manufacturing System Configuration The configuration of a manufacturing system can facili- tate the system's productivity and responsiveness. Facil- ity location and facility layout are the system configura- tion requirements for global manufacturing. In this paper, facility layout is considered. A designer of manufactur- ing systems should consider cell configurations and sys- tem configurations. Reconfigurable machines intra-cells and/or inter-cell are necessary especially during next period. 4. Converting Methodology The proposed methodology for converting Job Shop manufacturing systems to focused cells will be intro- duced into five phases. The objective of first phase is used to collect data of existing parts (products) and ma- chines from existing Job Shop manufacturing system. The second phase is to group parts into part families ac- cording to similarity in processing requirements. Distrib- uting part families to machines will be assigned in third phase according to part(s) specification. Formation of manufacturing cells, including part families with ma- chine cells will be introduced in fourth phase. In fifth phase, formed manufacturing cells will be evaluated and revised. 4.1. Phase 1: Collecting the Existing Data from Job Shop Manufacturing Systems It should analyze carefully existing Job shop manufac- turing systems into different perspectives such as existing parts and machines information analysis. For parts (products) information analysis, it should include number of jobs or products (sometimes called lot size), number of machines required for each part (product), processing or manufacturing time from each operation, demand (lot size) of each one. For machines information analysis, it also should include number of machines in a plant, how many manufacturing departments, and how many differ- ent types of machines in each department and the speci- fication of each machine. Also, it should exactly know a machine capacity and machine flexibility (capability). 4.2. Phase 2: Grouping Parts to Part Families Parts are assigned to part families according to the simi- larity in processing requirements between two parts (products). A procedure to group parts into part families will be explained in following steps: Step 1: Compute the similarity coefficient matrix be- tween all parts according to the following Equation (1): where: q = similarity coefficient between part type p and part type q, S p Dt = demand of part type p at time t, t q = demand of part type q at time t, k = subscript of parts (k = 1, …, n), c = total number of machines in the cth cell, m = number of machines in the job shops manufacturing system, Dm q m = number of machines that both part p and part q visit, c = total number of parts in the cth cell, lp t = processing time part p takes on machine , = processing time part q takes on ma- chine , n l llq t ql = 1, if part type p and part type q visit machine , l ql = 0, otherwise, ql Y = 1, if part type p or part type q visits machine , l ql Step 2: Determine the desired number of part families (NPE) by the following equation: Y = 0, otherwise min n NPF n (2) where: n = number of parts in existing Job shop manu- facturing systems, = minimum number of parts in a part family. min n Step 3: Select the largest similarity part p and part (q, …, n) to start grouping the first part family .Check for the minimum part family size (at least one part per fam- ily). Decrease the value of similarity index to group the second part family. Also, form a new part family ac- cording to the lower similarity. Check to determine if some parts have not been assigned to part families. 4.3. Phase 3: Assigning Machines to Machine Cells Machine cells involve assignment of machines into ma- 1 1 max , max ,, Xpql XX pql pql Xpql m lp Plq qpql l pq mmm lp Plq qpqllp Plq qpql llm tDt tD tX S tDt tDtXtDt ORtD tY (1) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Converting Traditional Production Systems to Focused Cells as a Requirement of Global Manufacturing 272 chine cells based on the new similarity coefficient be- tween two machines. A similarity coefficient between machines will base on processing time of all part type operations, number of operations performed, machine capability (flexibility) and machine capacity (reliability), and demand of each part (product). A procedure to group machines into machine cells will be explained in follow- ing steps: Step 4: Check the machine balancing at any time MB(t) of each machine type capacity 12 ,,, m CtCtC t to produce all parts (products) demands 12 ,Dt Dt manufactur- , ,n Dt by these machines in job shop s. The MB of machine i at any given time t is based on demand rates and processing times of all parts (products) assigned to machine i. The equation for com- puting MB for machine i is shown as a following Equa- tion (3) ing system 1 n ikik k Bt tDt (3) Step 5: Compute the similarity between all machines ac en machines i cording to the following Equation (4). where: ij S Similarity coefficient betwe and j, = capacity of machine i at time t, i Ct j Ct = capacity of machine j at time t, k Dt = dem part type k at time t, l = subscriachines (l = 1, …, m), i o n= numberf operations done on machine i, and of pt of m o o n = numr of operations done on machine j, max i O N aximum numbers of operations available on m i (machine capability) at time t, max j O N = maximum number of operations available on ne j (machine capability) at time t, ij X n = number of parts that can visit both machines i aj, ki t = processing time part k takes on machine i including stup time. ki t = processing time part k takes on be = machine machi nd e machine j in- cluding setup time, ijk X n = 1, if part type k visits both machines i and j, ijk = m 0, otherwise, ijk Y = 1, if part type k visits eitheachine i or machine j, ijk Y = 0, otherwise. Step 6: r Determine the desired number of machines cells ( NMC ) by the following Equation (5). max m NMC m (5) = maximum number of machines into machine max m cell. Step 7: Select a highest similarity index between ma- chine i and machine (j, …, m) to start forming the first machine cell. Check the minimum machine cell size con- straint (at least two machines per cell). Decrease a value of similarity index to form a new machine cell or add machines to the existing one. Check for a maximum number of machines in a machine cell. If number of ma- chines in this machine cell does not exceed the desired number of machines, then, add to this cell. Otherwise, stop adding to this cell and go back to select another similarity index. If number of machine cells formed ex- ceeds desired number of machine cells , join two machine cells into one machine cell. If all machines have not been assigned to machine cells, assign a functional cell(s). NMC 4.4. Phase 4: Formation of Manufacturing Cells Step 8: Manufacturing cells are formed by grouping parts into part families and machines to machine cells. The corresponding manufacturing cells based on results ob- tained from Phase 2 and Phase 3 was formed by distrib- uting part families to associated machine cells. 4.5. Phase 5: Performance Evaluation Step 9: Compute exceptional parts and bottleneck ma- chines. 4.5.1. Productivity Measures Step 10: Machine i utilization in cell c at time t, ic Ut, is evaluated as the following Equation (6). 1 c ic n kk k ic ic tDt MU tCt (6) where ic Ct capacity of machine i in cell c at time t, tt ic k = processing time part k takes on machine i in cell c, = number of parts produced in cell c. c Step 11: Cell utilization at time t, , is esti- mated as the following Equation (7). n ic CU t 1 1 1 c ic c m kk mk ci cic tDt CU tmCt (7) max max maxmaxmax 1 max , max , xij j i iMax i Xij j i i X iji j ij no o kiki ijk k kio jo ij nn o o o kj kjkj ki ki ijk kijk k kln io jojojo n n tt XDt Ct NtCt Nt Sn nn tt t tt DtORY Dt Ct NtCt NtCt NtNt Nt 1 Xij n k (4) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Converting Traditional Production Systems to Focused Cells as a Requirement of Global Manufacturing273 wStep on is calculated as the following Equation (8). here c m= number of machines inside cell c. 12: Cellular system utilization at any given time t, SU t, is calculated as an average cell utilization and depend number of manufacturing cells in system. s The SU t 1 11 11 c ic c m ct kk mk ic ci cic tDt SU tCtmC t (8) ufacturing cells at time t. [45] and it is expressed in the following Equa- tion (9). where: C(t) = number of man 4.5.2. Flexibility Measures Step 13: Machine flexibility (MFLX) inside a cell after forming the manufacturing cells will be assessed by the machine processing capability and capacity (reliability). This flexibility will be used to measure capability of a machine max 01 1ic ic O ic k oi nic ic ic SMCtSMF t MFLX tCtN t (9) ic FLXt = flexibility measure of machine i in m = slack in machine capac in manufac- anufacturing cell c at time t. ic SMC tity i turing cell, ic SMCt = ic ic Ct MBt m c 1ic ic k k k Bt tDt ic SMFt =ty slack in machine capabilii in manu- rations on machi ons on machine i in manu- fa [45] and it is expressed in the following Equation (10). facturing cell, max ic ic icO ico SMF tNtn. max ic Oic Nt = maximum number of ope ne i in manufacturing cell c. o n = number of operati ic cturing cell c. Step 14: Cell flexibility After forming the manufacturing cells, cell flexibility (CFLX) will be assessed by the number of machines in- side the cell. This flexibility is used to evaluate the manufacturing cell flexibility max 10 1 1 o ci ic n mic ic i cicOic 1 SMCtSMF t CFLX tmCtNt (10) the man cts) and it is expressed in the following Equation (11). k Step 15: Cellular System flexibility After forming ufacturing cells, new product (part) flexibility (CSFLX ) will be assessed by the flexi- bility of cells in the system. Cellular system flexibility [45] can be used to test the cellular formation after as- signing part families to machine cells for accepting one or more new parts (produ max 1101 1 11 o ci ic n Ct mic ic Ci cicOic t k SMCtSMFt CSFLXtCtmC tN (11) r Hours Report” for the set up time su 5. Case Study and Implementation XYZ Co., Inc., a manufacturing company for customer service, is located in Houston, Texas. XYZ Co. produces different types of parts (products) which are used in other manufacturing companies according to customer’s re- quests. These parts are requested by the customers by identifying the quantity of each part (job) accompanied by engineering drawing or prototype of the part. This company has several machine tools, from conventional machines to Computerized Numerical Control (CNC) machines, for general purpose. The main objective of this case study is to demonstrate the application and usefulness of the proposed manufac- turing cells design approach for conversion and/or recon- figure the traditional job shop manufacturing systems to cellular systems. In the XYZ Co., Inc. machines were analyzed to identify the manufacturing cells that were included in the plant by determining the number of them. The number of machines with the identifying number of identical machines will also be identified. The specifica- tion of machines regarding machine capacity and capa- bility will also be presented. Information with respect to parts produced in the XYZ Co., Inc., will be selected based on the number of parts (jobs) processed during the same time period. The processing times of these parts on machines with the sequence of operations were taken from the “Work Orde and processing time. 5.1. Machines Information Analysis To analyze the machines in the layout, the number of machines in the plant was divided into five manufactur- ing departments. Three departments were used conven- tional machines (Lathe or turning (1) department, Lathe (2) department, and milling machines department). There are other two departments including all the CNC ma- chines. It can be noticed in lathe department (1) that there are two different types of lathe machines with a total of 7 machines. Five similar machines are such as L (1)-A-A-L (2)-L (3), and two similar machines are such as L (4)-B. Also, in the lathe department (2), there are two different types of lathe machines with a total of 5 machines. Two similar machines are such as: L (5)-L (6) and three simi- lar machines are such as: C-C-L (7). For milling depart- ment, there are six identical universal milling machines ch as D-D-M1 (8)-D-D-M2 (9). Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Converting Traditional Production Systems to Focused Cells as a Requirement of Global Manufacturing Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM 274 s also three ssing times, sequence, and quantity of ne unit (part) on universal mill- To demonstrate the application of the proposed cell de- Table 1. Machines Information. Machine # Machine Code (Hours/week) Max. # of Operations There are two different CNC departments. One CNC lathe department includes five different CNC turning centers with a total of 6 machines such as: E-F-CNCL (10)-G-L-L. The other CNC milling department includes four different CNC vertical machining centers with a total of 6 machines such as H-I-CNCVMC (11)-J-K- CNCVMC (12). Machine specification data regarding the machines’ capacities and capabilities will be shown in Table 1. In this table, there are 12 machines that are used to process the 14 parts (products). These machines are L (1), L (2), L (3), L (4), L (5), L (6), L (7), M (8), M (9), CNCL (10), CNCVMC (11), and CNCVMC (12). The existing job shop manufacturing system plant layout is illustrated in Figure 1. It can be noticed from Figures 1 and 2 that part 6 proceeds through lathe (1) department and CNC lathe department. Part 7 proceeds through three departments: lathe (2), milling, and CNC milling. Also, part 8 needs three departments to be completed: lathe (1), lathe (2), and milling. Finally, part 9 need departments: lathe (1), lathe (2) and milling. 5.2. Products (Parts) Information Analysis To analyze jobs information, the number of parts in a plant was collected based on existing number of parts during the same period. There are 14 parts in processing during this period and 746 parts (products) on a waiting list. Table 2 presents the data of 14 parts on machines by identifying proce parts (products). 5.3. Machines-Parts Information Analysis To analyze machines-parts information, it is recom- mended to use the machine-part incidence matrix be- cause it is considered an easiest way to represent proc- essing requirements of the 14 parts on 12 used machines types (see Figure 3). It can be noticed that part 1 needs 57.2 minutes to process o ing machine [(M1 (8)]. 5.4. Application of the Conversion Methodology Machine Type Machine Capacit L (1) L (2) L (3) L (4) L (5) L (6) L (7) M (8) M (9) CNCL (10) C) Uni/C CNCnter NC VMC (11 CNC VMC (12) 02001 02004 02005 02022 02024 02051 02023 03004 03006 04001 05003 05007 Turning Lathe Turning Lathe Turning Lathe Turning Lathe Turning Lathe Turning Lathe Turning Lathe versal Milling M Universal Milling M/C CNC Turning Centre Vertical Machining Ce CNC Vertical Machining Center 80 80 80 80 80 80 80 80 80 80 80 80 20 20 20 9 8 20 9 13 13 14 16 30 P1 P2 P3 P4P5P6 P7P8 P9P10 P11 P12 P13 P14 L (1) 13.9 1.17 28.35 L (2) 1. 22.86 95 L (3) 1650.62 L (4) 0.27416. L (5) 1471. 11 L (6) 17.0 L (7) 95.9104. M1 (8) 547.2 7.44.48 M2 (9) 5.06 CNCL (10) 5.23. 28 12 C) 2123.9 NCVMC (11 4.8 CNCVMC (12) 129.7 Demand (Units) 3 26 120 1021203 328 176 7 4 60 8 Figu 1.chine-penix. re Maart incidce matr  Converting Traditional Production Systems to Focused Cells as a Requirement of Global Manufacturing275 Figure 2. Existing job shop manufacturing sy ste m layout. sign regarding the reconfiguration from job shop manu-forming manufacturing cells, and evaluating performance. facturing systems into cellular systems, it should follow the sequence of procedures. This sequence can be repre- sented in the similarity in processing requirements be- tween parts and between machines, clustering machines into machine cells, grouping parts into part families, The final machine cells and part families will be shown as follows: Machine cell # 1: {1, 2, 3, 10}, Machine cell # 2: {4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12}, Part family # 1: {3, 12}, Part family # 2: {4, 14}, Part family # 3: {5, 6, 10}, Part family # 4: {8, 9}, Part family # 5: {1, 7, 13}, Part family Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Converting Traditional Production Systems to Focused Cells as a Requirement of Global Manufacturing 276 Table 2. Produnformation. cts Part # Sequence (MachineDemand (Lot Size) i s) Processing Time (minutes) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 M1 (8) CNCVMC (12) L (2) L (1) L (3) L(1)-L( L(5) 1.17 - 5.28 147. 0.4 120 3)-CNCL (10) -M1 (8VMC (11) L(4)-L(6)-L(7)-M1 (8) )-CNC L(4)-L(7)-M2 (9) CNCL (10) CNCVMC (11) L (2) L (5) L (1) 57.2 129.7 1.86 13.9 165.0 0.62 - 0 24.8 1- 17.0 - 95.9 - 4.48 - 47.4 - 26.7 - 14.0 - 5.60 23.12 123.9 22.95 1.11 28.35 3 26 10 2 120 3 32 8 176 7 4 60 8 Table 3. Formedufacturing cells. Manufacturing cell Part Families man Machine cells (machines) 1 L (1) ), L (2), L (3), CNCL (10PF1, PF2, PF3 2 L (4), L (5), L (6), L (7(11), CNCVMC (12) ), M1 (8), M2 (9), CNCVMC PF4, PF5, PF6 PF1 PF2 PF3 PF4 PF5 PF6 P3 P12 P4 P14 P5P6 P10 P8 P9P7 P13 P11 P1 P2 13.9 28.35 L (1) 12.17 L (2) 1. 8622.9 L (3) 165 0.62 5.28CNCL (10) 23.12 L ) (4 0.41 26.7 L (5) 147 1. 11 L (6) 17.0 L (7) 95.9 14.0 M1 (8) 4.48 57.247.4 M2 (9) 5.60 CNCVMC11 24.8 123.9 CNCVMC12 129.7 D emand (Units)120 4 8 210 120 176 328 3 3 60 26 7 Fig3. Fl foatf macinglls. 6: {2, 11}, The Final manufacystem is expected not only to ac- garding why reconfiguration of ex- ure inarmion oanuftur ce #turing cells will be shop manufacturing s shown (see Figure 3), and then the manufacturing cells are two (see Table 3). Measuring performance evaluation of manufacturing cell design will depend on the productivity and flexibility issues in different levels (machine, cell, system). The results will be shown in Table 4. It can be noticed from then results that there are six part families and two ma- chine cells. Also, it can be noticed that there are three part families were assigned to each machine cell. This means that each machine cell can be process more than one part family. This will lead to say that reconfigure Job commodate for production of a variety of products which are grouped into part families, but also it must give a significant response to deal with introducing a new product within each family [45]. It can be noticed that there is no exceptional parts and bottleneck machines in this case. May be this application has a limited number of parts and machines. To compare the existing job shop manufacturing sys- tem and the new manufacturing cells design, the number of machines will be a major criterion. This represents the major contribution re Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Converting Traditional Production Systems to Focused Cells as a Requirement of Global Manufacturing277 e p Table 4. Performance measures of throposed manufacturing cells design. Machine Cell System Machine Type tion Flexibility Utilization Utilization System Machine Machine Cell Cell System Utiliza Flexibility Flexibility 1 L (1) CNCL (10) L (2) L (3) 0.1056 0.0656 0.0846 0.9797 0.7602 0.8408 0.8238 0.0173 0.3089 0.6105 2 CNCVMC (11) CNCVMC (12) 0.2416 0.6051 0.2753 0.6078 L (4) L (5) L (6) L (7) M1 (8) M2 (9) 0.0472 0.1058 0.1137 0.6626 0.0952 0.0093 0.1962 0.7028 0.7410 0.6705 0.8419 0.2621 0.6959 0.9144 0.7032 0.0120 isting Job shocells re im e time because there is a reduction in capital invest- adi- tio facturing systems into focused cells p to focused are moportant all th ment through minimizing the number of machines used in the plant. They can be used in other places in new plants. The new plant layout can be shown in Figure 4. It can be noticed from Figures 3 and 4 that there are a big difference in the number of machines in each plant layout. From this study, it can be noticed that there are reduction or improvement in plant layout, reduced in inter-process handling costing. The number of work-in-progress is also reduced by 80% than the Job shop systems. 6. Conclusions and Recommendation for Future Work This paper presented a new concept for converting tr nal Job shop manu Figure 4. The proposed manufacturing cells design layout. systems based on the globalization issues. Globalization issues were proposed in this paper, and they will lead to suggest a new reconfiguration process. The proposed methodology of converting was introduced sequentially beginning grouping parts (products) into part families and assigning machines to those part families. Hence, the manufacturing cells were formed. The proposed method- ology of conversion was examined with an industrial case study for its justification. The results show that there are main differences between the existing Job shop manufacturing system and focused cells which are con- sidered the core of the new innovative manufacturing systems which can are used easily to apply lean manu- facturing and agile manufacturing/management philoso- phies. The main contribution in this paper is how to convert conventional Job shop manufacturing systems to focused cells although most of plants (factories) in the world are still working as the job shop system (functional or proc- ess layout). The author intends to extend this research for more applications in real case studies in next period es- pecially under existing depression (global recession) in h elping in reducing capital investment or saving or install machines in other plants. 7. Acknowledgements The author would like to acknowledge the financial sup- port provided by the Sultan Qaboos University (Grant No. IG/ENG/MIED/10/01) to carry out this research work. REFERENCES [1] I. H. Garbie, “A Roadmap for Reconfiguring Industrial Enterprises as a Consequence of the Global Economic Crisis,” Journal of Service Science and Management, Vol. 3, No. 4, 2010, pp. 419-428. doi:10.4236/jssm.2010.34048 [2] I. H. Garbie, “Designing Cellular Manufacturing Systems Incorporating Production and Flexibility Issues,” PhD Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Converting Traditional Production Systems to Focused Cells as a Requirement of Global Manufacturing 278 Dissertation, The University of Houston, Houston, 2003. [3] I. H. Garbie, H. R. Parsaei and H. R. Leep, “Measurement of Needed Reconfiguration Level for Manufacturing Firms,” International Journal of Agile Systems and Ma- nagement, Vol. 3, No. 1-2, 2008, pp. 78-92. [4] U. Wemmerlov and D. J. Johnson, “Cellular Manufactu- ring at 46 User Plants: Implementation Experiences and Performance Improvements,” International Journal of Production Research, Vol. 35, No. 1, 2007, pp. 29-49. doi:10.1080/002075497195966 [5] U. Wemmerlov and D. J. Johnson, “Cellular Manufactu- ring in the US Industry: A Survey of Users,” Inter- ction Research, Vol. 37, 1999 doi:10.1080/00 , national Journal of Produ pp. 413-431. [6] R. F. Marsh, S. M. Shafer and J. R. Meredith, “A Com- parison of Cellular Manufacturing Research Presumptions with Practice,” International Journal of Production Research, Vol. 39-3138. 7, No. 14, 1999, pp. 311 2075499190202 [7] S. Venkataramanaiah and K. Krishnaiah, “Hybrid Heuristic for Design of Cellular Manufacturing Systems,” Production Planning and Control, Vol. 13, No. 3, 2002, pp. 274-283. doi:10.1080/09537280110073978 [8] O. Feyzioglu and H. Pierreval, “Hybrid Organization of Functional Departments and Manufacturing Cells in the Presence of Imprecise Data,” International Journal of Production Research, Vol. 47, No. 2, 2009, pp. 343-368. doi:10.1080/00207540802425898 [9] M. B. Durmusoglu, “Analysis of the Conversion from a Job Shop System to a Cellular Manufacturing System,” International Journal of Production Economics, Vol. 30-31, 1993, pp. 427-436. doi:10.1016/0925-5273(93)90110-7 [10] N. Gaither, G. V. Frazier and J. C. Wei, “From Job Shops to Manufacturing Cells,” Production and Inventory Management Journal, Vol. 31, No. 4, 1990, pp. 33-36. [11] G. A. Levasseur, M. M. Helms and A. A. Zink, “A Conversion from a Functional to a Cellular Manufacturing Layout at Steward, Inc.,” Production and Inventory Mana- gement Journal, Vol. 36, No. 3, 1995, pp. 37-42. [12] M. Liang and S. M. Taboun, “Converting Functional Manufacturing Systems into Focused Machine Cells―A Bicriterion Approach,” International Journal of Produc- tion Research , Vol. 33, No. 8, 1995, pp. 2147-2161. doi:10.1080/00207549508904808 [13] G. C. Onwubolu, “Redesigning Job Shops to cellular Manufacturing Systems,” Integrated Manufacturing Sys- tems, Vol. 9, No. 5, 1998, pp. 377-382. doi:10.1108/09576069810238763 [14] S. Collett and R. J. Spicer, “Improving Productivity through Cellular Manufacturing,” Production Inventory Management Journal, Vol. 36, No. 1, 1995, pp. 71-75. [15] F. O. Olorunniwo and G. J. Udo, “Cell Design Practices in US Manufacturing Firms,” Production and Inventory nal Journal of Production 031-1050. Management, Vol. 37, No. 3, 1996, pp. 27-33. [16] M. Cantamessa and A. Turroni, “A Pragmatic Approach to Machine and Part Grouping in Cellular Manufacturing System Design,” Internatio Research, Vol. 35, No. 4, 1997, pp. 1 doi:10.1080/002075497195524 [17] A. Baykasoglu, N. N. Z. Gindy and R. C. Cobb, “Capability Based Formulation and Solution of Multiple Objective Cell Formation Problems using Simulated Annealing,” Integrated Manufacturing Systems, Vol. 12, No. 4, 2001, pp. 258-274. doi:10.1108/09576060110392560 [18] A. I. Abdelmola and S. M.Taboun, “A Simulated Annea- ling Algorithm for Designing Cellular Manufacturing Systems with Productivity Consideration,” Production Planning and Control, Vol. 11, No. 6, 2000, pp. 589-597. doi:10.1080/095372800414151 [19] G. J. Nair and T. T. Narendran, “CASE: A Clustering Algorithm for Cell Formation with Sequence Data,” International Journal of Production Research No. 1, 1998, pp. 157-179. , Vol. 36, 80/002075498193985doi:10.10 e- [20] Y. Won and K. C. Lee, “Grouping Technology Cell Formation Considering Operation Sequences and Produc- tion Volumes,” International Journal of Production R search, Vol. 39, No. 13, 2001, pp. 2755-2768. doi:10.1080/00207540010005060 [21] C. H. Cheng, C. H. Goh and A. Lee, “Designing Group Technology Manufacturing Systems Using Heuristics Branching Rules,” Computers and Industrial Engineering, Vol. 40, No. 1-2, 2001, pp. 117-131. doi:10.1016/S0360-8352(00)00080-2 [22] A. M. Mukattash, M. B. Adil and K. K. Tahboub, “Heuristic Approaches for Part Assignment in Cell For- mation,” Computers and Industrial Engineering, Vol. 42, No. 2-4, 2002, pp. 329-431. doi:10.1016/S0360-8352(02)00020-7 [23] V. Ramabhatta and R. Nagi of Manufacturing Cell Formation w , “An Integrated Formulation ith Capacity Planning and Routing,” Annals of Operations Research, Vol. 77, 1998, pp. 79-95. doi:10.1023/A:1018933613215 [24] W. E. Wilhelm, C. C Chiou and D. B. Chang, “Inte- grating Design and Planning Considerations in Cellular Manufacturing,” Annals of Operations Research, Vol. 77, 1998, pp. 97-107. doi:10.1023/A:1018985630053 [25] Y. Yin and K. Yasuda, “Manufacturing Cells Design in Consideration of Various Production Factors,” Internatio- nal Journal of Production Research, Vol. 40, No. 4, 2002, pp. 885-906. doi:10.1080/00207540110101639 [26] R. G. Askin and M. Zhou, “Formation of Independent Flow-Line Cells based on Operation Requirements and Machine Capabilities,” IIE Transactions, Vol. 3 1998, pp. 319-329. 0, No. 4, 08179808966472doi:10.1080/074 002075499191742 [27] S. Sofianopoulou, “Manufacturing Cells Design with Alternative Process Plans and/or Replicates Machines,” International Journal of Production Research, Vol. 37, No. 3, 1999, pp. 707-720. doi:10.1080/ mming Model for Vol. 77, 1998, pp. 109-128. [28] M. Chen, “A Mathematical Progra System Reconfiguration in a Dynamic Cellular Manufac- turing Environment,” Annals of Operations Research, Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Converting Traditional Production Systems to Focused Cells as a Requirement of Global Manufacturing Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM 279 doi:10.1023/A:1018917109580 [29] F. F. Boctor, “The Minimum-Cost, Formation Problem,” International Jou Machine-Part Cell rnal of Production Research, Vol. 34, No. 4, 1996, pp. 1045-1063. doi:10.1080/00207549608904949 [30] R. G. Askin, H. M. Selim and A. J. Vakharia,”A Methodology for Designing Flexible Cellular Manu- facturing Systems,” IIE Transactions, Vol. 29, No. 7, 1997, pp. 599-610. doi:10.1080/07408179708966369 [31] B. R. Sarker and Y. Xu, “ Designing Multi-Product Lines: Job Routing in Cellular Manufacturing Systems,” IIE Transactions, Vol. 32, No. 3, 2000, pp. 219-235. doi:10.1080/07408170008963894 [32] R. Galan, J. Racero, I. Eguia and J. M. Garcia, “A Metho- dology for facilitating Reconfiguration in Mnaufacturing: the Move towards Reconfigurable Manufacturing Sys- tems,” International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, Vol. 33, No. 3-4, 2007, pp. 345-353. doi:10.1007/s00170-006-0461-2 [33] R. Galan, J. Racero, I. Eguia and J. M. Garcia, “A Systematic Approach for Product Families Formation in Reconfigurable Manufacturing Systems,” Robotics and Computer Integrated Manufacturing, Vol. 23, No. 5, 2007, pp. 489-502. doi:10.1016/j.rcim.2006.06.001 [34] S. M. Saad “The Reconfiguration Issues in Manufacturing Systems,” Journal of Processing Technology, Vol. 138, No. 1-3, 2003, pp. 277-283. [35] M. R. Abdi and A. W. Labab, “Grouping and Selectin 65 g Products: The Design Key of Reconfigurable Manufactu- ring Systems (RMSs),” International Journal of Produc- tion Research, Vol. 42, No. 3, 2004, pp. 521-546. doi:10.1080/002075403100016136 ro- [36] S. Ahkioon, A. A. Bulgak and T. Bektas, “Cellular Manufacturing Systems Design with Routing Flexibility, Machine Procurement, Production Planning and Dynamic System Reconfiguration,” International Journal of P duction Research, Vol. 47, No. 6, 2009, pp. 1573-1600. doi:10.1080/00207540701581809 [37] S. Ahkioon, A. A. Bulgak and T. Bektas, “Integrated Cellular Manufacturing Systems Design with Production Planning and Dynamic System Reconfiguration,” Euro- pean Journal of Operational Research, Vol. 192, No. 2, 2009, pp. 414-428. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2007.09.023 [38] W. Hachcha, F. Masmoudi and M. Haddar, “Combining Axiomatic Design and Designed Experiments for Cellular Manufacturing Systems Design Framework,” Internatio- nal Journal of Agile Systems and Management, Vol. 3, No. 3-4, 2008, pp. 306-319. [39] I. Alkattan, “Workload Balance of Cells in Designing of Multiple Cellular Manufacturing Systems,” Jour Manufacturing Technology Managemenal of nt, Vol. 16, No. 2, 2005, pp. 178-196. doi:10.1108/17410380510576822 [40] F. M. Defersha and M. Chen, “A Comprehensive Mathe- matical Model for the Design of Cellular Manufacturing Systems,” International Journal of Production Econo- mics, Vol. 103, No. 2, 2006, pp. 767-783. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2005.10.008 [41] H. A. Bashir and S. Karaa, “ Assessment of Clustering Tendency for The Design of Cellular Manufacturing Systems,” Journal of Manufacturing Technology Mana- gement, Vol. 19, No. 8, 2008, pp. 1004-1014. doi:10.1108/17410380810911754 [42] K. Das, R. S. Lashkari and S. Sengupta, “Reilability Considerations in the Design of Cellular Manufacturing Systems—A Simulated Annealing Based Approach,” International Journal of Quality and Reliability Mana- gement, Vol. 23, No. 7, 2006, pp. 880-904. doi:10.1108/02656710610679851 [43] K. Das, R. S. Lashkari and S. Sengupta, “Reilability Considerations in the Design of Cellular Manufacturing Systems,” International Journal of Production Econo- mics, Vol. 105, No. 1, 2007, pp. 247-262. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2006.04.015 [44] S. Zolfaghari and M. Liang, “Machine Cell/Part Family Formation Considering Processing Times Capacities: A Simulated Annea and Machine ling Approach,” Compu- ters and Industrial Engineering, Vol. 34, No. 4, 1998, pp. 813-823. doi:10.1016/S0360-8352(98)00112-0 [45] I. H. Garbie, H. R. Parsaei and H. R. Leep, “Introducing New parts into Existing Cellular Manufacturin based on a Novel Similarity Coeffi g Systems cient,” International Journal of Production Research, Vol. 43, No. 5, 2005, pp. 1007-1037. doi:10.1080/00207540412331270432 [46] S. S. Heragu, “Group Technology and Cellular Manufac- turing,” IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cyber- netics, Vol. 24, No. 2, 1994, pp. 223-230. doi:10.1109/21.281420 [47] I. H. Garbie, H. R. Parsaei and H. R. Leep, “A Novel Approach for Measuring Agility in Manufacturing Firms,” International Journal of Computer Applications in Technology, Vol. 32, No. 2, 2008, pp. 95-103. doi:10.1504/IJCAT.2008.020334 [48] Y. Koren, “The Global Manufacturing Revolution-Pro- duct-Process-business Integration and Reconfigurable Systems,” 1st Edition, John Wiley and Sons, Hoboken, 2010.

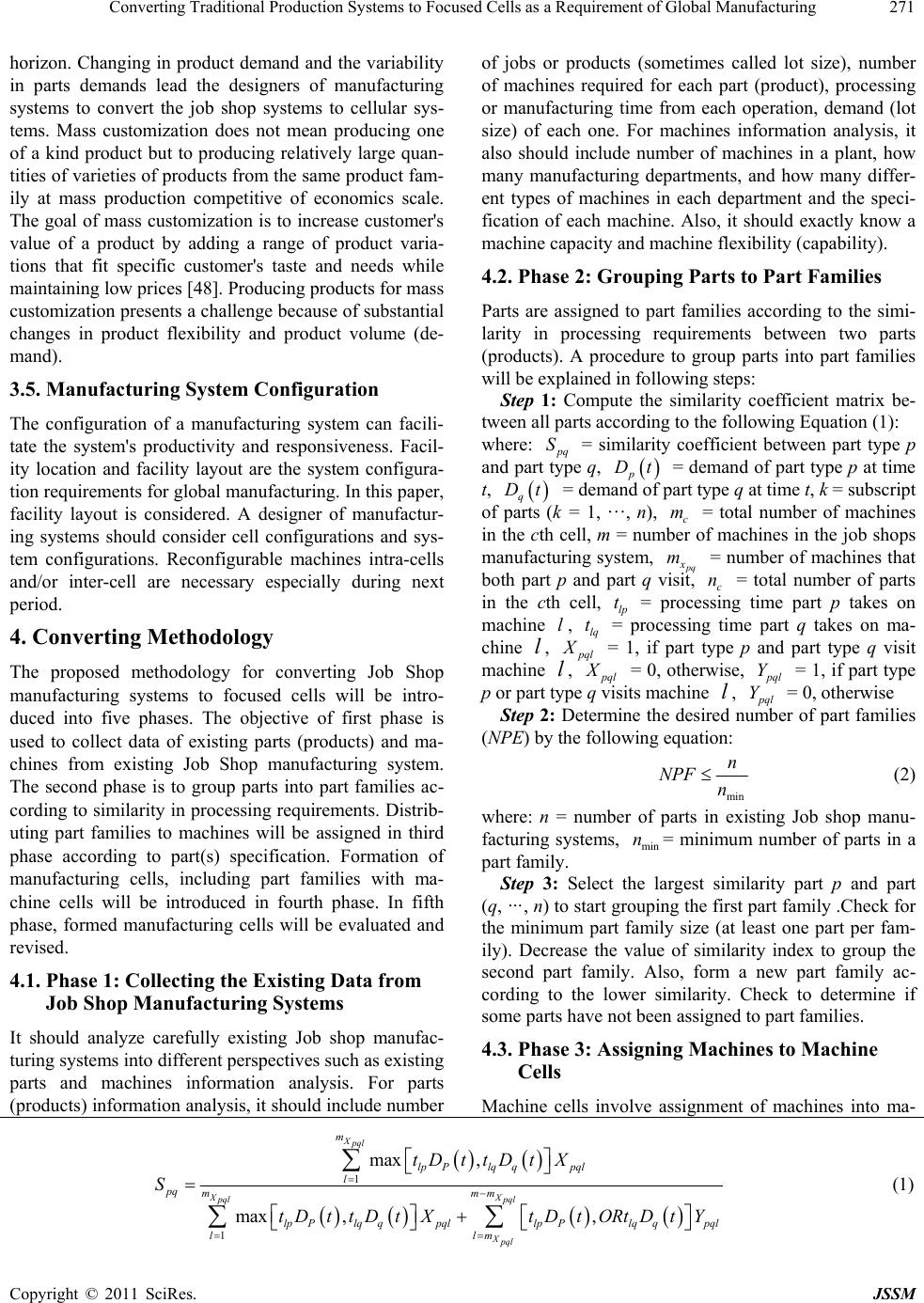

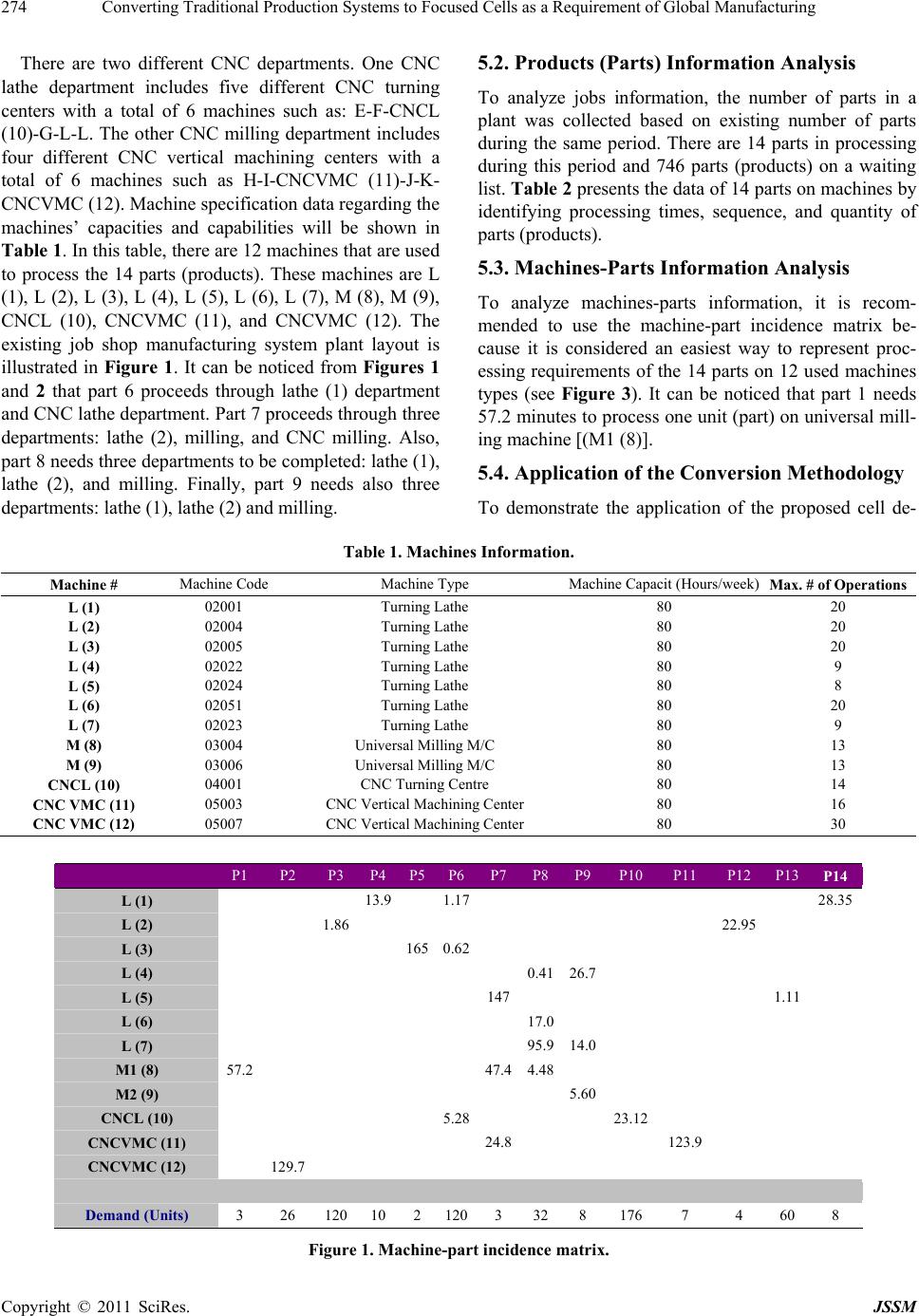

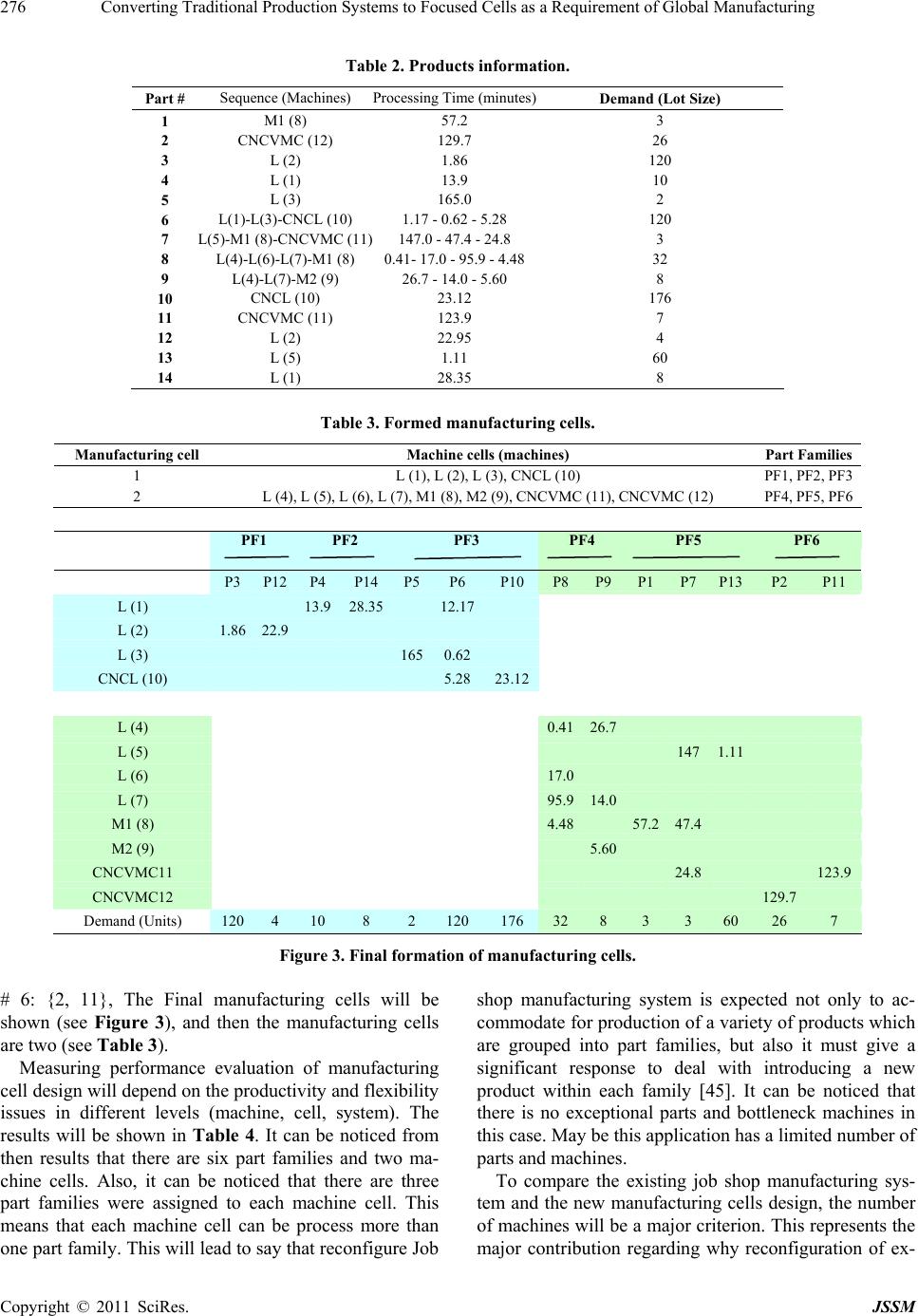

|