Psychology 2011. Vol.2, No.6, 615-623 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. DOI:10.4236/psych.2011.26094 Driving after Brain Injury: A Clinical Model Based on a Quality Improvement Project Anna Lundqvist1,2, Johan Alinder2, Ingalill Modig-Arding2, Kersti Samuelsson1,2 1Rehabilitation Medicine, Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden; 2Department of Clinical Rehabilitation Medicine, University Hospital, Linköping, Linköping, Sweden. Email: Anna.Lundqvist@lio.se Received May 24th, 2011; revised July 13th, 2011; accepted August 25th, 2011. The question of whether a person can resume driving after acquired cognitive dysfunction is raised in primary care services and in hospital departments where patients suffering from brain injury are treated. These organiza- tions rarely have a specialized program that evaluates driving fitness. This article describes a semi-structured and individualized model that serves as clinical guidelines for determining fitness to drive. The model is based on former research and clinical experience. It is exemplified by the procedure of forty-three individuals with congenital or acquired cognitive dysfunction due to head trauma or disease. A multidisciplinary team including medical, neuropsychological, occupational, and practical driving specialists optimised the clinical applicability of a driving assessment using quantitative and qualitative methods. The team discussions, including several pro- fessional evaluations and assessments, are considered very important for interpreting results, for understanding whether the cognitive impairments will have consequences on driving, and whether the individual can compen- sate for cognitive difficulties. The current way to determine a patient’s fitness to drive after cognitive dysfunc- tion is an individually adapted combination of assessment methods that are often performed stepwise. This well-practiced evaluation process reveals that in many cases neither off-road tests nor on-road tests alone are sufficient to ensure sound decisions. To improve on these evaluations, this study concludes that a team-based consensus approach consisting of specialized national teams should be established to support primary care ser- vices in assessing fitness to drive in more complicated cases. Keywords: Traffic Psychology, Cognitive Dysfunction, Driving Assessment, Teamwork, Clinical Model Introduction In 2007, Kofi Annan, former Secretary-General of the United Nations, called the high traffic accident rate in the world “the hidden epidemic” (Annan, 2007). Although alcohol is the pre- dominant factor that kills people in car accidents every year (Vägverket, 2008; National Institutes of Health Department of health and human services USA, 2009), illness and injury that affect the brain are also factors that cause traffic accidents (Boake, Macleod, High, & Lehmkuhl, 1998; Pietrapiana, Tami- etto, Torrini, Mezzanato, & Perino, 2005; Schanke, Rike, Møl- men, & Østen, 2008). Recently, traffic accident research has found that fatigue is a main risk factor (Anund, 2009). A person’s fitness to drive means the driver can manage traf- fic situations without being a traffic risk, anticipate demands in specific traffic situations, and prepare oneself for action. Driv- ing safely requires flexibility, fast information processing speeds, and insight that includes strategic planning and the ability to understand when not to drive (Brouwer & Ponds, 1994; Brouwer & Withaar,1997; Withaar, 2000). Thus a per- son’s fitness to drive after brain injury must be evaluated with a broad perspective that includes current and pre-morbid medical, psychological, and cognitive functions as well as driving skill (Brouwer & Ponds, 1994). Medical Reg ulations for Fitness to Drive Countries establish their own driving rules and regulations. Most national driving license agencies recognize that many diseases and other medical conditions may affect a person’s ability to drive a motor vehicle safely. The laws about when a license can be withdrawn from a driver vary between different countries. Some countries require physicians to report to the driving license authority if they have a patient whose driving abilities might be compromised. Other countries require the drivers themselves to report a medical change before they re- sume driving (Pellerito, 2006). In Sweden, basic requirements for a driving license after disease or head trauma are legally formulated in the Swedish Code of Statutes, the official publication of all Swedish laws (Swedish National Road Administration, 1998). Persons who want to start taking driving lessons must apply for driving per- mit. The Swedish Code of Statutes does not formulate concrete requirements for receiving a professional driving license. However, persons who have a license for heavy vehicles (e.g., buses and lorries), often professional drivers, are obliged to present to the driving license authorities a health declaration from a physician. Other drivers have a license for driving a private car. Physicians are legally obligated to report to the licensing authority if they find a patient unfit to hold a driving license due to medical conditions. Such reports often result in withdrawal of the driving license. The physician has the possi- bility to avoid this obligation on two conditions: if the patient is seriously impaired so the question of driving will not be raised or if the physician finds it obvious that the patient will obey a temporary verbal driving prohibition, which should be docu- mented in the medical casebook and followed up by the physic- cian. The requirements for a driving license are rather easy to interpret for conditions such as visual field deficiency and epi-  A. LUNDQVIST ET AL. 616 lepsy, but more problematic when it comes to cognitive im- pairments due to progressive diseases such as dementia and MS or after brain injury. Assessment of Driving Performance Different methods have been used to assess a person’s driv- ing performance. Statistical relationships between neuropsy- chological test results and on-road assessment outcomes have been evaluated in many studies (Lundqvist, Alinder, & Rönn- berg, 2008; Schanke & Sundet 2000; Akinwuntan, Feys, De Weerdt, Pauwels, Baten, & Strypstein, 2002; Akinvuntan, De Weerdt, Fey, Baten, Arno, & Kiekens, 2005; Akinwuntan, Feys, De Weerdt, Baten, Arno, Kiekens, 2006; Coleman, 2002; Lundqvist, Alinder, Alm, Gerdle, Le- vander, & Rönnber, 1997, Lundqvist, Gerdle, & Rönnberg, 2000; Mazer, Korner Bitensky, & Sofer, 1998; Nouri, Tinson, & Lincoln,1987; Nouri & Lin- coln,1992; Devos, Akinwuntan, Nieuwboer, Truijen, Tant, & De Weerdt, 2011), yet there is no accepted method that pro- duces sufficient and necessary infor- mation about relevant functions for driving performance on the individual level and there are no cut-off limits of test results that explicitly state the minimum test scores for driving fitness (Schanke & Sundet, 2000; Vrkljan, McGrath & Letts, 2011). Furthermore, because self-awareness, driving experience, and pre-morbid personality and attitudes are identified as im- portant factors for coping with cognitive impairments, these issues should be considered when deciding on a patient’s driv- ing fitness (Schanke, Rike, Mølmen, & Østen, 2008; Lundqvist, Alinder, & Rönnberg, 2008; Tate,1999). Although cognitive test results are the base for driving assessment, qualitative ob- servations are important for interpreting possible consequences of the quantitative information and for forming a final decision. There is a chance that patients at risk might not be identified when using either off-road tests or on-road tests alone. Cons- quently, quantitative as well as qualitative results from different assessments should be used to determine a person’s driving fitness after acquired brain injury. Injury and illness affect cognitive functions in different ways. Therefore, it is important to know which functions should es- pecially be assessed. Some patients, mostly suffering from frontal traumatic brain injury have a higher risk for accidents compared to people in general (Boake, Macleod, High, & Lehmkuhl, 1998; Schanke, Rike, Mølmen, & Østen, 2008). They can perform well on neuropsychological tests measuring cognitive speed, but might still have executive impairments, impaired insight and judgement. Therefore, it is important to scrutinize those functions. Concerning patients with right- hemisphere injuries, e.g. after stroke, it is especially important to assess their insight, attention, visual scanning and visuo- spatial functions, which are most important driving on-road in a multi-stimuli environment. Some of the geriatric patients with mild dementia might have attention impairments, cognitive slowness, orientation problems and difficulties understanding instructions. In primary care services and in many hospital departments such as neurological, geriatric, and rehabilitation clinics, the question of whether the patient can resume driving should be raised more often. The physician in primary care services has the responsibility to evaluate the patient’s medical condition, but a single medical examination is often insufficient to judge whether the patient is at risk from a medical point of view (Jo- hansson, Bronge, Lundberg, Persson, Seideman, & Viitanen, 1996). Occupational therapists in primary care services can screen for cognitive function that along with a medical exami- nation can be sufficient in finding those individuals who have comprehensive cognitive impairments or physical impairments that make them unfit to drive. In more complicated cases, a multidisciplinary approach is required; however, clinics rarely have a specialized program to assess driving fitness (Larsson, Lundberg, & Falkmer, 2007). A Clinical Driving Assessment Model There is a need for an organized, structured, and verified procedure to assess and recommend whether a person can re- sume driving after cognitive dysfunction. A team-based spe- cialized driving assessment program is part of our outpatient rehabilitation services. The multidisciplinary team consists of a MD, a neuropsychologist, and an occupational therapist (OT), all experienced in evaluating driving fitness. In addition, a speech therapist is consulted if required. The team collaborates with a driving instructor who is specialized in driving evalua- tions for persons with medical dysfunctions. The aim of this study is to describe a model and clinical guidelines for deter- mining driving fitness for patients with cognitive dysfunction in a rehabilitation setting. The guidelines are based on a clinical assessment procedure using quantitative as well as qualitative methods for data collection as well as for analysis. The assess- ment process includes medical and cognitive factors and an on-road driving assessment that all together serve as a basis for a final decision about a person’s driving fitness made by the driving assessment team through a team discussion. Methods Subjects The team-based clinical assessment procedure was used to evaluate 43 persons suffering from cognitive dysfunction due to congenital or acquired brain injury, mild dementia, or cognitive dysfunction related to other neurological disease and to heart disease. The 43 persons were the total number of patients who were referred to the driving assessment team in 2007 and 2008. Out of these, five young persons were assessed to determine their fitness for receiving driving permits (to start taking driv- ing lessons). All of these had a congenital brain injury: one Myelodysplastic Meningocele, three Cerebral Palsy, one Mild Mental Retardation. Thirty persons were evaluated for resuming driving a private car and eight persons were evaluated for a professional driving – seven for driving heavy vehicles and one for driving a taxi (Figure 1). These eight had already resumed driving a private car. Sixteen persons had a verbal driving prohibition from the physician and nine were still allowed to drive, although their physician had referred them to be evaluated for their driving fitness. Seven had a withdrawn driving license. Thirty-three were men and five were women. The group was heterogeneous according to age, time since injury onset, and diagnosis. Me- dian age was 63 years (SD 14.6). The individuals were assessed about 26 months (SD 33) after illness/injury onset. The large standard deviation was due to four persons who were referred many years after they were injured. As seen in Table 1, the most common diagnosis was stroke. Procedures The medical examination consisted of a detailed medical history, a neurological examination, and an examination of  A. LUNDQVIST ET AL. 617 Figure 1. Outcome for 38 people who were referred f or dr iv in g a ssessment. Table 1. Diagnoses for 38 people who were assessed for fitness to drive, 33 men (87%) and 5 women (13%). Diagnosis n % Stroke 18 47 Traumatic brain injury 6 16 Mild Dementia 7 18 Tumour 2 5 Heart disease 2 5 Other (anoxia, other neurological disease) 3 8 Total 38 99 static and dynamic visual acuity with a moving object as the target (Lundberg & Johansson, 2007. The neuropsychological assessment, testing cognitive functions, consisted of tests based on previous research (Lundqvist, Alinder, Alm, Gerdle, Le- vander, & Rönnberg 1997, Lundqvist, Gerdle, & Rönnberg, 2000; Lundqvist, 2001). The neuropsychological assessment used the Trail Making Test B (TMTB) and three computerized tests from the Automated Psychological Test Battery (APT) (Levander,1988): the Complex Reaction Time test including reaction inhibition (requiring executive function); the K test (a focused attention test); and the Simultaneous Capacity test (a divided attention test). Additional neuropsychological tests assessing visuo-constructive functions (Complex Figure Test, Block Design), executive functions (Wisconsin card Sorting Test), and working memory (Color Word Test) were applied when required. To address additional cognitive functions, the Nordic version of SDSA (NorSDSA) (Lundberg, Caneman, Samuelsson, Halamies-Blomqvist, & Almqvist 2003) was used for all subjects either by the neuropsychologist or by the OT. The SDSA is an adapted version of The British Stroke Driver Screening Assessment (SDSA) (Nouri & Lincoln,1992; Lundberg, Lundberg, Caneman, Samuelsson, Halamies-Blom- qvist, & Almqvist 2003). The neuropsychological assessment also included an interview containing questions for evaluating the patient’s self-awareness and pre-morbid and current per- sonality. The OT interviewed the subjects about their driving history and conducted a cognitive screening that included testing for visual neglect using the Behavioural Inattention Test (BIT) (Wilson,Cockburn, & Halligan,1987), testing for attentiveness using a simple driving simulator (SIM), and testing for reaction speed (Lundberg &Johansson, 2007; Brouwer, Ponds, & Van Wolffelaar,1989; Brouwer, & Waterink, 1991; Van Wolffelaar, van Zomeren, Brouwer, & Rothengatter, 1988). In collabora- tion with the driving instructor, the OT could also request a standardized on-road assessment for about 60 minutes with a variety of driving situations regarding action and environment. All individuals drove under similar circumstances during the on-road assessment. The driving instructor was responsible for instructions, the driving route, and safety, while the OT made the assessment after a discussion with the driving instructor. The subjects drove a car with manual or automatic gearshifts and a dual-brake system. The OT evaluated the subjects’ on- road driving skill using a modified version of the Performance Analysis of Driving Ability, the ‘P-Drive’ protocol (Patomella, Caneman, Kottorp, & Tham, 2004; Patomella,Tham, & Kottorp, 2006; Patomella, Tham, Johansson, & Kottorp, 2010). The original P-Drive on-road contains twenty-seven items, which form a unidimensional scale. According to Patomella et al. (2010) “it (P-Drive on-road) upholds aspects of internal scale validity and reliability for producing a linear measure of driving ability in people with stroke, dementia and mild cognitive im- pairment”. The on-road assessment is the last part of a total driving as- sessment and the OT had access to the medical as well as to the neuropsychological results before an on-road assessment. On- road driving was evaluated in relation to the patient’s medical and/or cognitive impairments to detect if impairments were verified in the driving assessment or if the patients compen- sated for impairments by self-awareness, driving experience, and pre-morbid driving behaviour. Thus this on-road assess- ment was more extensive than a traditional on-road assessment as it was the intent to evaluate the person’s self-awareness and driving experience as compensation strategies for an impaired medical condition. During the interviews, all team members focused on self-awareness and attitudes about driving from their professional perspectives.  A. LUNDQVIST ET AL. 618 The team assessed all subjects (in part or fully) using the de- scribed procedure (Table 2). Twenty patients completed the entire procedure with a full assessment containing medical examination, neuropsychological assessment, cognitive screen- ing, and on-road assessment. Four persons required using cars with automatic transmission; two of these required a special lever for the turn signals and the accelerator. The remaining used cars with manual transmission. The neuropsychological assessment was not included for eight patients. All of them had the diagnosis mild dementia and were already diagnosed at the geriatric clinic. The on-road assessment was not included for ten patients because the team could determine their driving fitness/unfitness without these examinations and/or because the patients’ driving license was temporarily withdrawn. Two had diagnosis stroke and anoxi. They had such great difficulties that they were con- sidered not capable of driving. Seven with diagnosis stroke, trauma, mild dementia, and cognitive dysfunction due to diabe- tes and hearth attack had their driving license withdrawn, and for one with diagnosis tumour, the medical assessment and the neuropsychological test results were convincing positive for driving. The decision whether the patient was fit for driving was made only after reviewing the quantitative and qualitative as- sessments. As the Swedish Code of Statutes does not formu- late concrete requirements for professional driving, the team members based their decisions on higher cognitive demands and responsibilities for professional drivers. Ethical Considerations The report is a clinical description to ensure the quality of clinical assessment (Hälsooch sjukvårdslagen, 1982). There- fore, it is not subject to evaluation by an ethics committee. Statistical Methods The Mann-Whitney U-test (p < 0.01) was used to compare the outcome measure, i.e. the cognitive assessment results for the group, which was determined by the assessment team to resume driving, with the group, which was determined by the assessment team not to resume driving. Outcome Every decision about a patient’s driving fitness was based on a team discussion considering quantitative as well as qualitative information. Thus, the outcome measure was the final decision determined by the assessing team. Driving Permit Group Four men and one woman with congenital brain injury were Table 2. Type of assessment fo r 38 persons. Type of assessment n % Medical examination, neuropsychological assessment, cognitive screening, and on-road assessment 20 53 Medical examination, neuropsychological assessment/ cognitive screening 10 26 Medical examination, cognitive screening, on-road assessment 8 21 Total 38 100 assessed for a medical declaration to be attached to the applica- tion for driving permit. All patients received a medical exami- nation, a neuropsychological assessment, and cognitive screen- ing. Mean age was 24.8 years (SD 5.4). All patients were approved to start taking driving lessons. Driving a Private Car and Professional Driving Group Thirty subjects were assessed for resuming driving a private car and eight persons were assessed for driving heavy vehicles, mostly professional driving. The outcome of the driving as- sessment according to the assessment team decision is shown in Figure 1. Of the 30 persons referred for private driving, 12 fulfilled the requirements, and 18 did not due to cognitive slowness, impaired divided attention, visuo-spatial impairments, or impaired insight. Two of these did not fulfil the basic medi- cal demands for driving due to impaired visual acuity and/or epilepsy. Eight had diagnosis stroke while six suffered from mild dementia. Four of the eight patients who were referred for driving a heavy vehicle fulfilled the requirements. Four were recom- mended not resuming professional driving: two due to cogni- tive slowness and decreased attention (although they could resume driving a private car) and two did not fulfil the basic medical demands and thus could not continue driving in any form. To summarize, four persons did not fulfil basic medical de- mands for driving and five persons had such great impairments (e.g., visual neglect, pronounced mental slowness, and/or im- pulsivity) that the referral physician or a local OT in primary care services should have been able to make the decision. The subjects who passed the assessment were heterogeneous ac- cording to diagnoses, question of referral, and comprehension of assessment. The findings reflect the assessments made in a clinical setting, which must offer individually adapted assess- ments for patients with a range of medical background condi- tions, combined with quantitative test results as well as qualita- tive observations. Assessment Tools The team made a decision for 38 persons. The decisions were based on both quantitative and qualitative information. Neuro- psychological assessment was made for 28 individuals. As mentioned before, eight patients with mild dementia were not assessed neuropsychologically. They were already diagnosed at the geriatric clinic. All of them were determined by the assess- ment team not to resume driving. In addition, several subjects in the not-resuming group did not complete the neuropsy- chological assessment either due to incapacity, tiredness, or difficulties understanding instructions, or the team could make a decision without the examination (Table 3). The qualitative aspect was considered most important in all assessments. That is, observations of the person in the assess- ment situation and his/her comments and reactions are valuable for understanding and interpreting the cognitive and executive test results. During the interview, the neuropsychologist evalu- ated the person’s self-awareness of impairment and insight. During the on-road driving assessment, the OT evaluated the person’s potential compensatory driving strategies. Twenty- eight individuals went through an on-road assessment; ten did not. Six of them were determined by the assessment team not to resume driving. To make an overall quantitative quality check of cognitive  A. LUNDQVIST ET AL. 619 Table 3. Assessment test data for 38 people. Means and standard deviations for the group of people resuming versus not resuming driving according to the assessment team decision, Mann-Whitney’s U- Test p-value 2-sided for independent samples. Statistical level p < 0.01. Test Resuming driving M (SD) n = 16 Not resuming driving M (SD) n = 22 Mann-Whitney U- Test p-value BIT (max 40) 38.8 (1.2) n = 12 34.6 (3.8) n = 17 p < 0.001 SIM (max 1.0) 0.88 (0.20) n = 12 0.55 (0.35) n = 21 p < 0.002 Trail Making Test B (sec) 121.3 (62.1) n=12 205 (83.9) n = 13 p < 0.002 Block Design (max 68) 34.4 (10.1) n = 12 27.2 (11.1) n = 12 n.s. Complex Figure Test (max 36) 34.5 (2.8) n = 12 30.9 (7.9) n = 12 n.s. Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (max 6) 3.7 (1.68) n = 12 2.3 (1.22) n = 9 n.s. Color Word Test (sec) 134.3 (36.9) n = 11 190.2 (72.5) n = 11 p < 0.05 APT k-test (T-value) 50.0 (5.7) n = 12 39.1 (10.0) n = 11 p < 0.001 APT Reaction Time (T-value) 41.3 (12.3) n = 12 25.2 (14.1) n = 12 p < 0.01 APT Simultaneous Capacity (T-value)48.3 (10.6) n = 12 37.9 (8.3) n = 9 p < 0.05 NorSDSA total 1.73 (1.20) n = 12 −0.63 (2.0) n = 20 p < 0.001 assessment tools, we made a group statistical analysis compare- ing the “resuming driving group” with the “not resuming driv- ing group” for all the 38 referred persons. The final decisions related to these tests are shown in Table 3. The two groups significantly differed with respect to the cognitive screening (SIM), the computerized focused attention test (APT k-test), TMTB, and the NorSDSA. On tests demanding attention and cognitive speed, the resuming driving subjects performed sig- nificantly better than the subjects who did not resume driving. Although several of the tests could separate the majority of cases between “resume driving” and “not resume driving” ac- cording to the assessment team decision, there was no single test that provided enough information alone to make a final decision. We propose a stepwise evaluation process where the final decision is based on a synthesis of the investigations and consensus from an experienced driving assessment team (Fig- ure 2; Hopewell, 2002). Discussion It takes time and it is a great challenge to develop a solid clinical procedure for driving assessment after injury or disease, but this work is crucial. The responsibility to determine a per- son’s fitness to drive after different medical conditions or inju- ries affecting the brain is a difficult and complex issue, espe- cially in cases of lack of insight and judgment. In many coun- tries fitness to drive is a medico-legal issue that is deferred to physicians, but in some countries determining one’s fitness to drive is left to the drivers themselves. Many physicians con- sider having insufficient competence and lack of tools to make such a judgment (Hakamies-Blomqvist , Henriksson, Falkmer, Lundberg, & Braekhus, 2002). Accordingly, it is important to have methods that can support a medical perspective where the issue is a matter of risk assessment. There is most likely a need for specialized assessment teams to support primary health care services to make more comprehensive assessments. A with- drawal of a driving license will lead to heavy consequences, especially for persons who rely on driving in their work. Such decisions should be based on proven procedures. Clinical guidelines based on research and many years of clinical experience must be considered as “good enough” in this description. Our clinical experience (more than ten years) can serve as a basis to describe a clinical model for a final decision about a person’s fitness to drive. We hope that our structured clinical procedure can be of use in other medical services deal- ing with individuals with cognitive dysfunction due to trauma or disease. Driving Permit All persons who were assessed for driving permit (n = 5) were evaluated with respect to medical requirements. They all had some cognitive impairment, but the examination could not tell whether the persons would be able to compensate for their impairment in a driving situation. Therefore, it was recom- mended that they take driving lessons before being evaluated. A follow-up by the team, however, showed that two did not man- age the driving lessons and one person never started the driving lessons. These findings agree with an unpublished follow-up study that addressed the outcome of driving permission among young people with ADHD or Asperger disease. More than 10% of the subjects never started their driving education, and more than half of the subjects never received their driving license (Johansson, 2009). One explanation of this might be that once they secured their permission, they were confirmed as compe- tent as anybody else, which was enough for them. Another explanation was that the subject was not motivated to drive, but other people in their lives were pushing them to apply for a driving license. Consequently, it is important to inquire about the applicant’s motivation and purpose for having a driving license especially considering the time and expense required for such testing. Driving a Private Car and Professional Driving Sixteen of the subjects had a verbal driving prohibition from the physician at the time when they were referred for assess- ment. Obviously, physicians use their possibility to give a temporary verbal driving prohibition. However, we have found that patients often interpret a veral prohibition as a temporary b  A. LUNDQVIST ET AL. 620 Figure 2. A multidisciplinary and multi stage decision model for a s sessing driving performance (modified after Ho pewell, 2002). condition (three to six months). Therefore, the physician has to explain explicitly the conditions of the prohibition and offer an appointment to the patient for a follow-up. At the follow-up, the physician reassess whether the patient can drive. One advantage of a verbal prohibition is that the person is allowed to do an on-road assessment. Seven persons had a withdrawn driving license; in some cases, this was due to poor medical conditions in the early rehabilitation phase. Once a driving license is with- drawn, it is not possible to conduct an on-road assessment, which could be a valuable complement in the total assessment in many cases. Remarkably, nine patients were driving while they were waiting for the assessment. Seven of them did not fulfil cogni- tive and/or medical requirements for holding a driving license. Consequently, it is strongly recommended that the doctors give a verbal prohibition when referring a patient for this kind of assessment. Four persons were referred despite the fact that they did not fulfil basic medical demands prescribed in the Swedish Code of Statutes (Swedish National Road Administration, 1998). It is strongly recommended that patients fulfil these demands before they are referred to a specialized assessment team. In addition, five persons had such great impairments that an OT in primary care services should have been able to make a basic screening of cognitive functions, which could reduce the need for referral. A doctor might refer a patient to avoid a negative influence on the doctor-patient relationship or to consult with other profess- sionals about the patient’s impairments and how they relate to driving fitness. When a doctor needs support, there should be a possibility to refer the patient for comprehensive assessment by another doctor or preferably by a team with special competence. The team then becomes the responsible entity for making re- commendations and the final decision regarding the patient’s driving fitness. There were two persons who were referred because they needed to drive heavy vehicles. After their assessment, it was decided that they were unable to operate even a private car. This is an important ethical complication. Therefore, a person who is referred for assessment of driving fitness must be accu- rately informed about the legal aspects and possible cones- quences of this investigation before accepting the procedure. Assessments Cognitive functions are assessed using cognitive screening  A. LUNDQVIST ET AL. 621 and neuropsychological tests, which we know from earlier studies, are relevant for driving assessments (Lundqvist, 2001). Statistical relationships between neuropsychological test results and on-road assessment outcomes have been found in several studies, e.g. in a recent review and meta-analysis by Devos, Akinwuntan, Nieuwboer, Truijen, Tant, & De Weerdt, 2011), which also support our former results that TMTB is a signifi- cant test to use. Still we believe that using cut-off scores are just a part of the total driving assessment. Although the clinical screening battery NorSDSA has shown to have varying sensi- tivity and specificity (Lincoln, & Fanthome, 994; Selander, Johansson, Lundberg, & Falkmer 2010), it can complement other tests and as such serve as a screening tool. We found, however, that the instructions were often difficult to understand for the elderly, leading to false negative results. Eight patients were not assessed neuropsychologically. They had such significant impairments that a cognitive screening was sufficient for making the decision. They went through a medi- cal examination and an on-road assessment. During the interviews, different team members focused on different qualitative characteristics. Insight and self-awareness are most significant predictors for driving (Lundqvist & Alin- der, 2007; Schanke & Sundet 2000; Patomella, Kottorp, & Tham, 2008). Pre-morbid factors, such as driving style, should be systematically evaluated during the interview, since traffic accidents are generally concentrated on a few drivers (Martin, & Estevez, 2005). Therefore, sensation seeking, risk proneness behaviour, and impulsivity should be investigated when evalu- ating a patient’s fitness to drive (Schanke, Rike, Mølmen, & Østen, 2008; Tate, 1999). The on-road assessment evaluates whether the medical and/or cognitive problems have consequences for driving. Therefore, the observations during driving are interpreted in relation to the patient’s current impairments and/or pre-morbid factors. The on-road driving assessment also gives information about the patient’s capacity to compensate for impairments in a real driving situation by being sufficiently aware of their im- pairments and safely adjusting their driving (Lundqvist & Alinder, 2007). One woman suffering from a left hemisphere injury had episodic memory impairments and cognitive infor- mation processing slowness. She had significant driving ex- perience and was well aware of her impairments and adjusted her driving to her current capacity. The team discussion is of utmost importance for understanding whether the impairments will have consequences on driving and whether the individual can compensate for the difficulties in the activity. If patients are unaware of their impairments, they might continue their pre- morbid driving style, a situation that could mean their reaction times are too slow for their post-morbid conditions. Some pa- tients might be aware of their impairments, but still be at risk due to cognitive slowness or motor impairments. All these cir- cumstances are important to discuss in the team. Subjects with aphasia are difficult to assess off-road due to their difficulties understanding instructions, a limitation that might significantly influence the test results. Therefore, it is even more important to make an on-road assessment for as- sessing whether he/she fulfils demands for attention, reaction speed, planning, and understanding and obeying traffic signs. A speech therapist is sometimes needed in the assessment to give the patient optimal conditions for a fair judgment. An on-road assessment is often seen as the “golden standard” and the best way to evaluate driving performance (Schanke & Sundet 2000; Hasselkorn, Mueller, & Rivara, 1998; Katz, Golden, Butter, Tepper, Rothke, Holmes, & Sahgal, 1990; Galski, Bruno, & Ehle, 1992; Sivak, Hill, Henson, Butler, Sil- ber, & Olson, 1984). Although the on-road assessment is done on a single occasion, it is an important part of the total assess- ment. It might be the most reasonable way to assess a patient in a way that is as similar to his/her ordinary driving capacity as possible. However, the driving must continue for at least 45 minutes or more to show potential difficulties. Issues for Developing the Model The purpose of this report is to describe a well-practiced model that stresses the use of quantitative and qualitative as- sessments that lead to a team consensus for a decision as solid as possible for each individual. One limitation is that we have not used protocols for the interviews. There are several tools to assess self-awareness (Anderson & Tranel,1989; Kottorp, 2006; Sherer, Bergloff, Boake, High, & Levin,1998) and self-reported on-road behaviour (Reason, Manstead, Stradling & Baxter, 1990), although with varying quality (Vrkljan, McGrath & Letts, 2011), that can be used in the future. In addition, another goal is to structure the interview for driving history and to de- velop protocols for pre-morbid factors. We also illustrate the constraints of clinical settings such as persons with a withdrawn driving license, persons who should not have been referred, and persons who lost their driving license after the assessment. Due to limited resources, we were unable able to assess persons suffering from Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis al- though there is a great need for driving assessments in these groups. Similarly, it is important to develop strategies and methods for basic training and compensation so as many brain-injured people as possible can resume driving (Leon- Carrion, Dominguez-Morales, Barroso, & Martin, 2005; Klon- off, 2010). Conclusions Driving performance is a multifactorial activity that depends on cognitive, executive, and affective factors as well as driving experience and pre-morbid factors. The current report clearly shows that some patients would not have been sufficiently as- sessed if off-road tests or on-road assessments alone had been used. Clearly, off-road tests or on-road tests alone are insuffi- cient for ensuring sound decisions. The assessment of a pa- tient’s fitness to drive is an individually adapted combination of assessments that can be efficient when applied in a stepwise manner. A multidisciplinary team including medical, neuro- psychological, occupational, and practical driving experts opti- mises the assessment quantitatively as well as qualitatively in a team-based consensus approach. Therefore, specialized national teams should be established to support primary care services in assessing driving fitness in more complicated cases. Declaration of Interest The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper. References Akinwuntan, A., Feys, H., De Weerdt, W., Pauwels, J., Baten, G., & Strypstein, E. (2002). Determinants of driving after stroke. A retro- spective study. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 83, 334-341. doi:10.1053/apmr.2002.29662 Akinvuntan, A., De Weerdt, W., Fey, H., Baten, G., Arno, P., &  A. LUNDQVIST ET AL. 622 Kiekens, C. (2005). The validity of a road test after stroke. Archives of Physical Medicine Reh abilitatio, 86, 421-426. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2004.04.047 Akinwuntan, A., Feys, H., De Weerdt, W., Baten, G., Arno, P., & Kiekens, C. (2006). Prediction of driving after stroke. Neuroreha bilitation & Neur al Repair , 20, 417-423. doi:10.1177/1545968306287157 Anderson, S., & Tranel, D. (1989). Awareness of Disease States Fol- lowing Cerebral Infarction, Dementia and Head Trauma: Standard- ized Assessment. The Clinical N europsychologist, 3, 327-339. doi:10.1080/13854048908401482 Anund, A. (2009). Sleepness at the wheel. Ph.D. Thesis, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden. Boake, C., Macleod, M., High, W., & Lehmkuhl, L. (1998). Increase of motor vehicle crashes among drivers with traumatic brain injury. Journal of the international Neuropsychological Socie ty, 7, 75. Brouwer, W., Ponds, R., & Van Wolffelaar, P. (1989). Divided atten- tion 5 to 10 years after severe closed head injury. Cortex, 25, 219- 230. Brouwer, W., & Ponds, R. (1994). Driving competence in older persons. Disabilitation and Reh ab i l it a t io n , 1 6 , 149-161. doi:10.3109/09638289409166291 Brouwer, W., & Waterink, W. (1991). Divided attention in experienced young and older drivers: lane tracking and visual analysis in a dy- namic driving simulator. Human Factors, 33, 573-582. Brouwer, W., & Withaar, F. (1997). Fitness to drive after traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychological rehabilitation, 7, 177-193. doi:10.1080/713755536 Coleman, R., Rapport, L., Ergh, T., Hanks, R., Ricker, J., & Millis, S. (2002). Predictors of driving outcome after traumatic brain injury. Archives of Physical M edicine Rehabilitation, 83, 1415-1422. doi:10.1053/apmr.2002.35111 Devos, H., Akinwuntan, A. E., Nieuwboer, A., Truijen, S., Tant, M., & De Weerdt, W. (2011). Screening for fitness to drive after stroke. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology, 76, 8747-8756. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e31820d6300 Galski, T., Bruno, L., & Ehle, H. (1992). Driving after cerebral damage: a model with implications for evaluation. American Journal of Oc- cupupational Therapy, 46, 324-332. Hakamies-Blomqvist, L., Henriksson, P., Falkmer, T., Lundberg, C., & Braekhus, A. (2002). Attitudes of primary care physicians towards older drivers: A Finnish-Swedish comparison. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 21, 58-69. Hasselkorn, J., Mueller, B., & Rivara, F. (1998). Characteristics of drivers and driving record after traumatic and nontraumatic brain in- jury. Archives of Physical Medicine Reha bilitation, 79, 738-742. doi:10.1016/S0003-9993(98)90349-5 Hopewell, C. (2002). Driving assessment issues for practicing clini- cians. Journal of Head Trau ma Rehabilitation, 17, 48-61. doi:10.1097/00001199-200202000-00007 Ministry of Health and Social Affairs (1982). Health and medical ser- vices act. 763. Johansson, K., Bronge, L., Lundberg, C., Persson, A., Seideman, M., & Viitanen, M. (1996). Can a physician recognize an older driver with increased crash risk potential? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 44, 1198-1204. Kurt, J. (2009). Personal communication. Katz, R., Golden, R., Butter, J., Tepper, D., Rothke, S., Holmes, J., & Sahgal, V. (1990). Driving safety after brain damage: follow-up of twenty-two patients with matched controls. Archives of Psychical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 71, 133-137. Klonoff, P., Olson, K., Talley, M., Husk, K., Myles, S., Gehrels, J., & Dawson, L. (2010). The relationship of cognitive retraining to neu- rological patients’ driving status: The role of process variables and compensation training. Brain Injury, 24, 63-73. doi:10.3109/02699050903512863 Kottorp, A. (2006). Assessment of awareness of disability: Develop- ment, administration and interpretation. Ph.D. Thesis, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden. Larsson, H., Lundberg, C., & Falkmer, T. (2007). A Swedish survey of occuptinal therapists’ involvement and performance in driving as- sessments. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 14, 215-220. doi:10.1080/11038120601110983 Leon-Carrion, J., Dominguez-Morales, M. R., Barroso, Y., & Martin, J. M. (2005). Driving with cognitive deficits: neurorehabilitation and legal measures are needed for driving again after severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury, 19, 213-219. doi:10.1080/02699050400017205 Levander, S. (1988). An automated psychological test battery. IBM-PC version (APT PC). Research Reports from the Department of Psy- chiatry & Behavioral Medicine, University of Trondheim, 11, No. 65, University of Trondheim, Norway. Lincoln, N., & Fanthome, Y. (1994). Reliability of the stroke drivers screening assessment. Clinical Rehabilitation, 8, 157-160. doi:10.1177/026921559400800208 Lundberg, C., Caneman, G., Samuelsson, S., Halamies-Blomqvist, L., & Almqvist, O. (2003). The assessment of fitness to drive after stroke: The nordic stroke driver screening assessment. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 44, 23-30. doi:10.1111/1467-9450.00317 Lundberg, C., & Johansson, K. (2007). Den enkla körsimulatorn, kliniska bedömningar och praktiskt körprov som komponenter vid körkortsmedicins bedömning (The simple driving simulator, clinical assessments and on-road driving as components of driving assess- men t) . TrMC Rapportserie, 6. Lundqvist, A. (2001). Cognitive functions in drivers with brain injury —anticipation and adaptation. Ph.D. Thesis. Linköping University, Sweden. Lundqvist, A., Alinder, J., Alm, H., Gerdle, B., Levander, S., & Rönn- berg, J. (1997). Neuropsychological aspects on driving after brain le- sion—simulator study and on road driving. Applied Neuropsychology, 4, 220-230. doi:10.1207/s15324826an0404_3 Lundqvist, A., Gerdle, B., & Rönnberg, J. (2000). Neuropsychological aspects on driving after stroke-in the simulator and on the road. Ap- plied cognitive psychology, 14, 135-150. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0720(200003/04)14:2<135::AID-ACP628> 3.0.CO;2-S Lundqvist, A., & Alinder, J. (2007). Driving after brain injury—self awareness, coping at the tactical level of control. Brain Injury, 21, 1109-1117. doi:10.1080/02699050701651660 Lundqvist, A., Alinder, J., & Rönnberg, J. (2008). Factors influencing driving after brain injury. Brain Injury, 22, 295-304. doi:10.1080/02699050801966133 Martin, F., & Estevez, A. (2005). Prevention of traffic accidents: The assessment of perceptual-motor alterations before obtaining a driving license. A longitudinal study of the first years of driving. Brain In- jury, 19, 189-196. doi:10.1080/02699050400017189 Member States to the Sixtieth World Health Assembly (May 2007). Road traffic injuries are a hidden global epidemic affecting millions of human. http://www.unece:trans/roadsafe/docs/CGRS Report Mazer, B. L., Korner-Bitensky, N. A., & Sofer, S. (1998). Predicting ability to drive after stroke. Archives of Physical Medicine Rehabili- tation, 79, 743-750. doi:10.1016/S0003-9993(98)90350-1 National Institutes of Health Department of health and human services USA. Fact sheet Alcohol—Related traffic Death. Nouri, F., Tinson, D., & Lincoln, N. (1987). The relationship between cognitive ability and driving after stroke. International Disability Studies, 9, 110-115. Nouri, F., & Lincoln, N. (1992). Validation of a cognitive assessment: Predicting driving performance after stroke. Clinical Rehabilitation, 6, 275-281. doi:10.1177/026921559200600402 Patomella, A.-H., Caneman, G., Kottorp, A., & Tham, K. (2004). Iden- tifying scale and person response validity of a new assessment of driving ability. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 11, 70-77. doi:10.1080/11038120410020520 Patomella, A.-H., Tham, K., & Kottorp, A. (2006). P-Drive: An As- sessment of Driving Performance after Stroke. Journal of Rehabilita- tion Medicine, 38, 273-279. doi:10.1080/16501970600632594 Patomella, A.-H., Kottorp, A., & Tham, K. (2008). Awareness of driv- ing disability in people with stroke tested in a simulator. Scandina- vian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 15, 184-192. doi:10.1080/11038120802087600 Patomella, A.-H., Tham, K., Johansson, K., & Kottorp, A. (2010). P-Drive on-road: Internal scale validity and reliability of an assess- ment of on-road driving performance in people with neurological disorders. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 17, 86-93. doi:10.3109/11038120903071776  A. LUNDQVIST ET AL. 623 Pellerito, J. M. (2006). Driver rehabilitation and community mobility. priciples and practice . St Louis, Missouri: Elsevier Mosby. Pietrapiana, P., Tamietto, M., Torrini, G., Mezzanato, R., & Perino, C. (2005). Role of premorbid factors in predicting safe return to driving after severe TBI. Brain Injury, 3, 197-211. doi:10.1080/02699050400017197 Reason, J. T., Manstead, A., Stradling, S., & Baxter, J. S. (1990). Errors and violations on the roads: A real distinction? Ergonomics, 33, 1315-1332. doi.org/10.1080/00140139008925335 Schanke, A., & Sundet, K. (2000). Comprehensive driving assessment: neuropsychological testing and on-road evaluation of brain injured patients. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 41, 113-121. doi.org/10.1111/1467-9450.00179 Schanke, A.-K., Rike, P.-O., Mølmen, A., & Østen, P. (2008). Driving behaviour after brain injury: a follow-up of accident rate and driving patterns 6-9 years post-injury. J Rehabil Med, 40, 733-736. Selander, H., Johansson, K., Lundberg, C., & Falkmer, T. (2010). The Nordic Stroke Driver Screening Assessment as predictor for the out- come of an on-road test. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 17, 10-17. doi.org/10.3109/11038120802714898 Sherer, M., Bergloff, P., Boake, C., High, W., & Levin, E. (1998). The Awareness Questionnaire: factor structure and internal consistency. Brain Injury, 12, 63-68. doi.org/10.1080/026990598122863 Sivak, M., Hill, C., Henson, D., Butler, B., Silber, S., & Olson, P. (1984). Improved driving performance following perceptual training in persons with brain damage. Archives of Physical Medicine Reha- bilitation, 65, 163-167. doi.org/10.1016/S0010-9452(08)70784-6 Swedish National Road Administration (1998). Code of statutes 1998:89. Swedish National Adminstration, Borlänge. Tate, R. (1999). Executive function and characterological changes after traumatic brain injury: two sides of the same coin? Cortex, 35, 39-55. Van Wolffelaar, P., van Zomeren, E., Brouwer, W., & Rothengatter, T. (1988). Assessment of fitness to drive of brain damaged persons. In T. Rothengatter and R. de Bruin (Eds.), Road used behavior: Theory and research (pp. 302-309). Assen: Van Gorcum. Wilson, B., Cockburn, J., & Halligan, P. (1987). Behavioral inattention test. Thamed Valley Company, Suffolk England. Withaar, F. (2000) Divided attention and driving: The Effects of Aging and Brain Injury. Ph.D. Thesis, Leeuwarden. Vrkljan, B., McGrath, C., & Letts, L. (2011). Assessment tools for evaluating fitness to drive: A critical appraisal of evidence. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 78, 80-96. doi.org/10.2182/cjot.2011.78.2.3 Vägverket (2008) The Swedish national road administration. Borlänge, Sweden

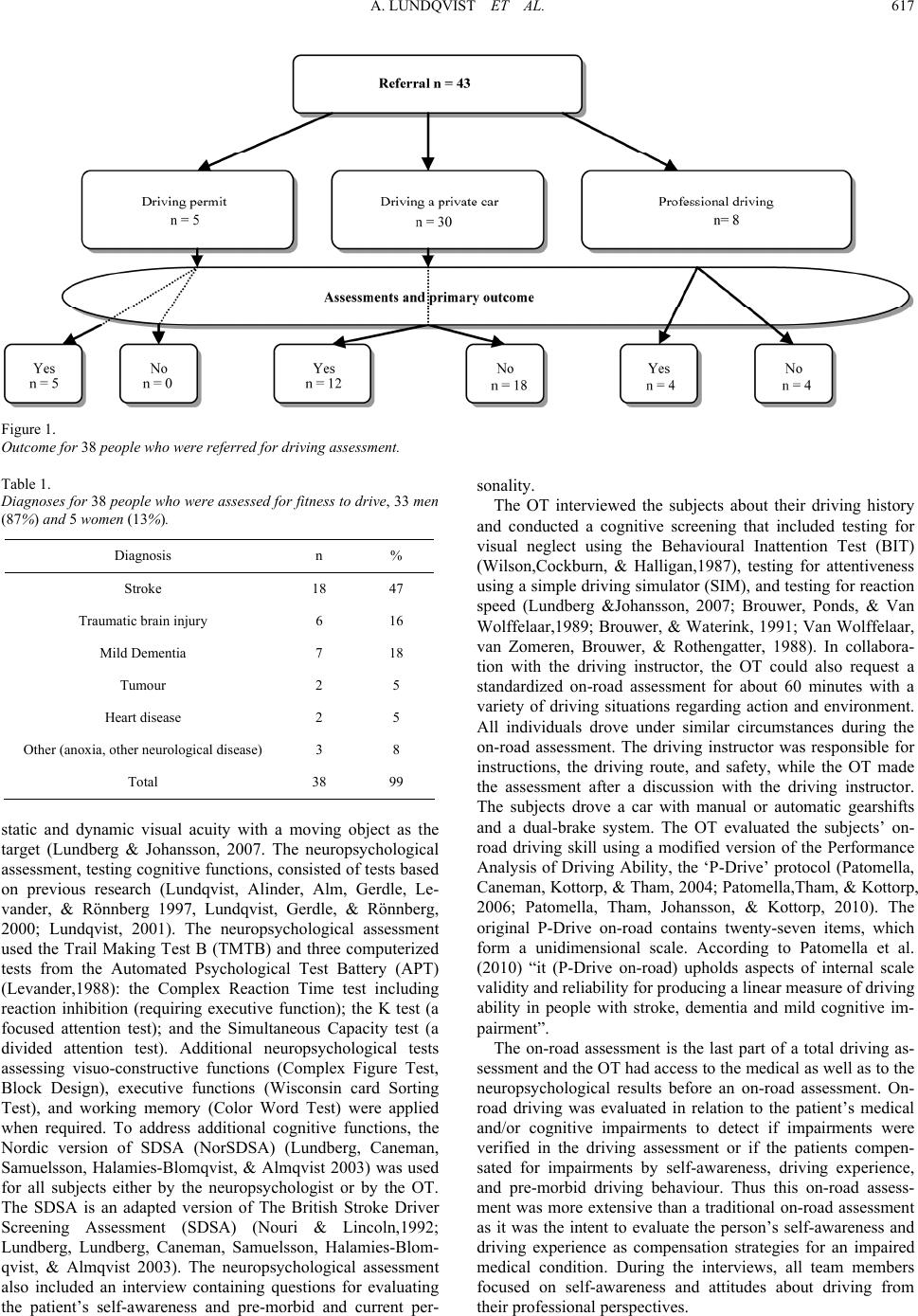

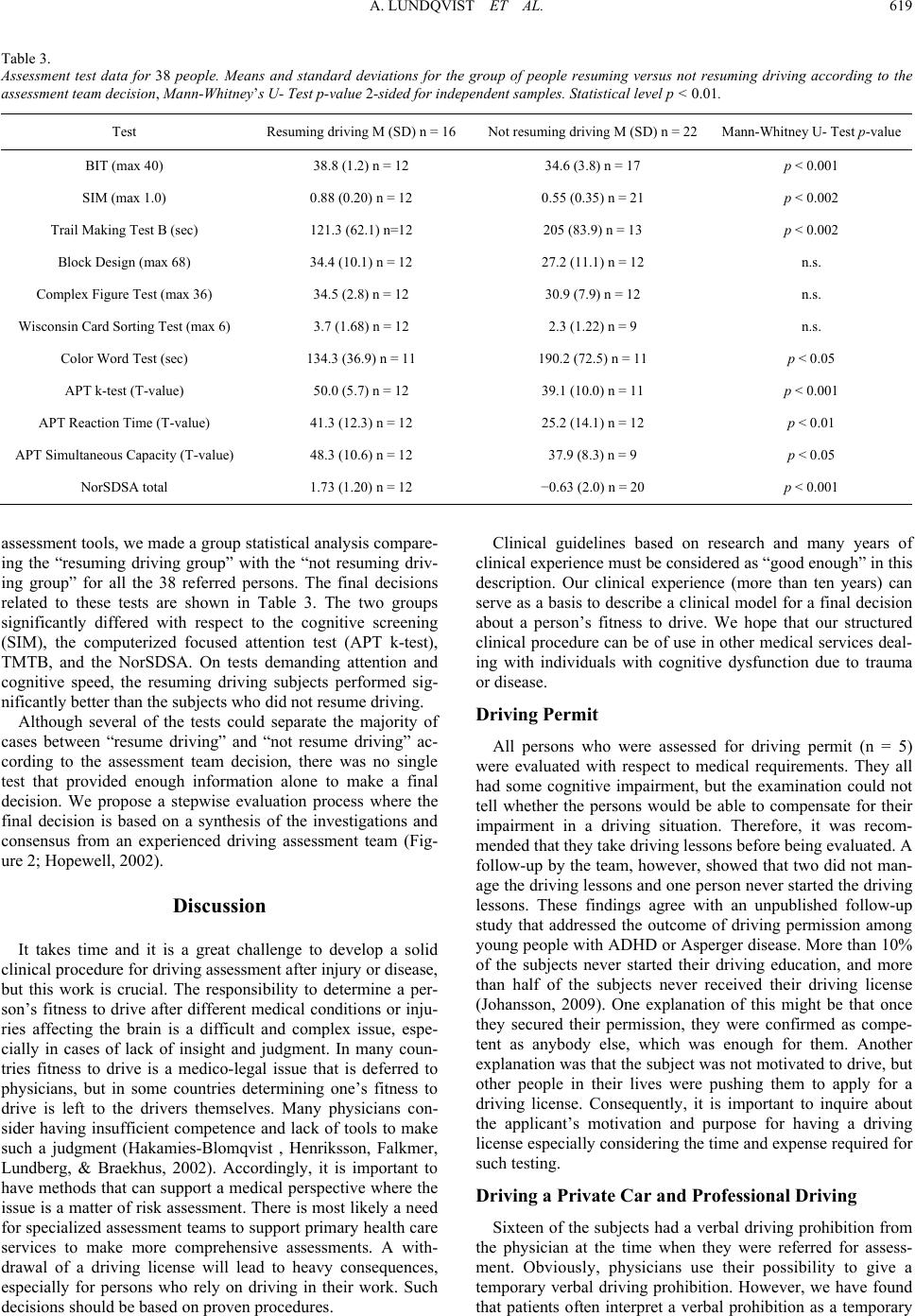

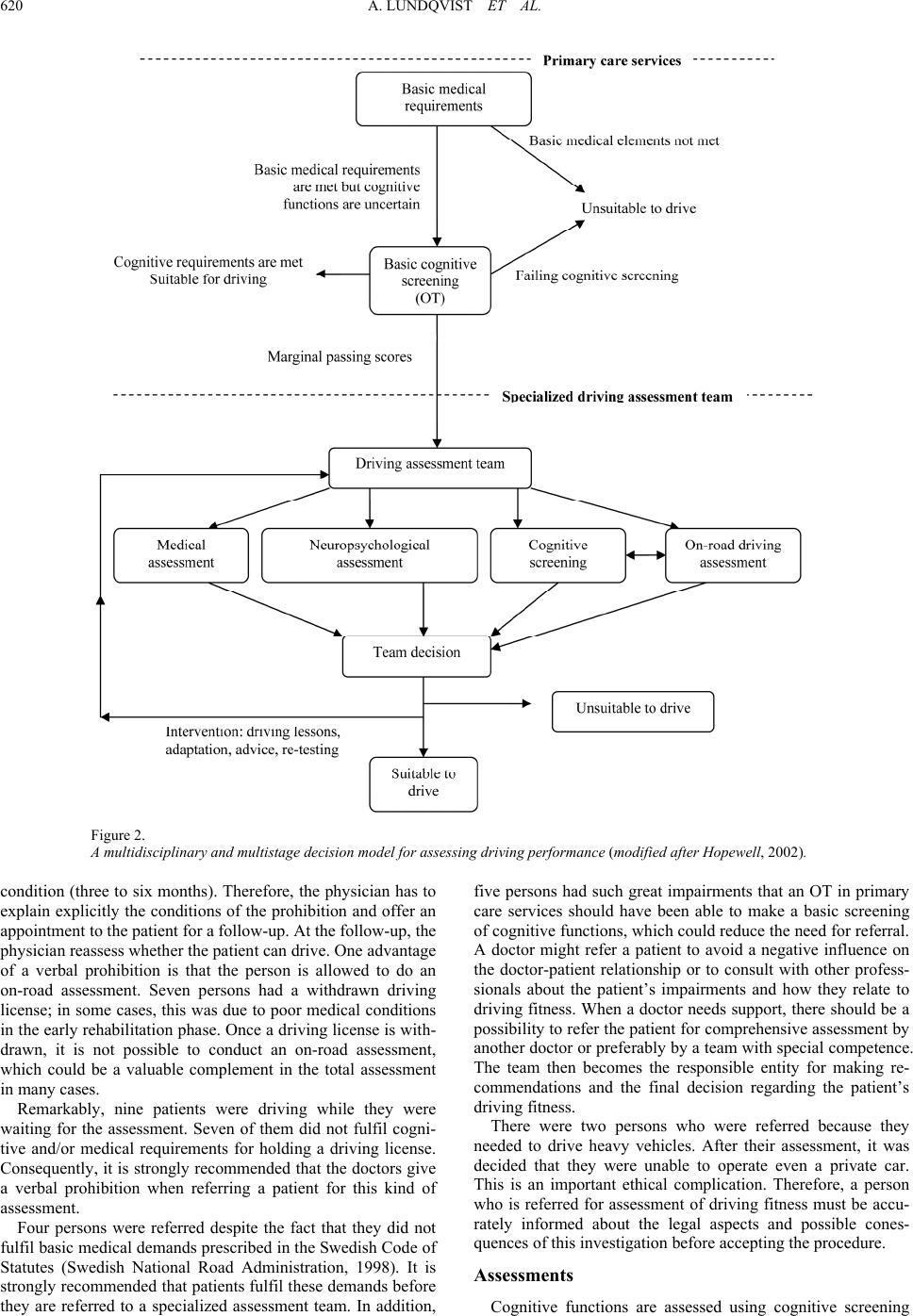

|