Psychology 2011. Vol.2, No.6, 605-614 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. DOI:10.4236/psych.2011.26093 Exposure Inhibition Therapy as a Treatment for Chronic Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Controlled Pilot Study* Nenad Paunović Department of Psychology, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden; Center for Andrology and Sexual Medicine, Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden. Email: kontakt@kbterapi.se Received May 11th, 2011; revised July 3rd, 2011; accepted August 5th, 2011. Exposure inhibition therapy as a treatment for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is evaluated in a randomized treatment outcome pilot study. The exposure inhibition therapy is based on crucial parts of the be- havioral-cognitive inhibition theory (Paunović, 2010). In this treatment primary incompatible respondent memo- ries are utilized in order to 1) directly counter numbing and depressive symptoms, 2) incorporate the primary trauma memory into primary incompatible memories, and 3) inhibit primary respondent trauma memories. Twenty-nine crime victims with chronic PTSD were randomized to a group that received exposure inhibition therapy immediately (N = 14), or a wait-list control group (N = 15) that waited for 2.5 months and then received the treatment. The group that first received treatment improved significantly on PTSD symptoms, (CAPS, IES-R, PCL) depression (BDI), anxiety (BAI), posttraumatic cognitions of self, others and guilt (PTCI), and coping self-efficacy (CES) compared to the wait-list control group. The treatment efficacy was high for PTSD symp- toms, depressive and anxiety symptoms, as well as on most cognitive measures. When the wait-list control group received treatment similar results were observed. Results were maintained at a 3-months follow-up in the treat- ment group, and on some measures improvement continued. Three empirically derived cut-off criteria (44, 39, 27) were used for the CAPS, and one cut-off level for the BDI (10), in order to assess the clinical significance of the results. The majority of clients no longer fulfilled PTSD as a result of the treatment except when the strictest level of cut-off criteria was used, and similar results were observed on the BDI. In conclusion, exposure inhibi- tion therapy was an effective treatment for chronic PTSD in this study. A proposal is made to compare exposure inhibition therapy with the state-of-the-art therapy for chronic PTSD, i.e. exposure therapy. Several hypotheses are presented; e.g. that exposure inhibition therapy may be more effective for some symptoms, and involves less emotional pain in the therapeutic process. Keywords: Exposure Inhibition Therapy, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Crime Victims, Randomized Treatment Outcome Pilot Study, Behavioral-Cognitive Inhibition Theory, Primary Respondent Memories Introduction Psychotherapies that have the strongest empirical support for the treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) focus on behavioral change (prolonged exposure to trauma triggers and the trauma memory) or the modification of mal- adaptive cognitions or appraisals (e.g., Cahill, Rothbaum, Re- sick, & Follette, 2009). Another promising treatment for chronic PTSD is exposure inhibition therapy (Paunović, 2002; 2003) that has been renamed from “prolonged exposure coun- terconditioning” due to the following reasons. First, although the primary focus is on respondent counterconditioning, other important inhibitory processes may be going on (e.g., appraisal processes and behavioral change). Second, the imaginal reliv- ing of primary incompatible respondent memories need no longer to be prolonged as in the original application of the me- thod. Third, redundant parts have been removed. Exposure inhibition therapy is based on the behavioral-cog- nitive inhibition (BCI) theory (Paunović, 2010). The parts that are directly relevant to the exposure inhibition therapy are pre- sented. Primary respondent memories of a traumatic event gen- erate the most distressing intrusion symptoms in PTSD and consist of the following encoded and stored elements: Central details of the traumatic event (primary respondent stimuli memories) Emotional, physiological and pain responses during the gist of the trauma (primary respondent response memories) Primary respondent trauma memories are closely associated with other primary trauma memory elements: 1) primary ap- praisal memories (appraisals during the trauma), 2) primary behavioral response memories (behaviors during the trauma), and 3) primary consequence memories (consequences that oc- curred during the trauma and the immediate trauma sequel). The continuous on-going threat experience in chronic PTSD is due to an on-going partial-full retrieval of primary respondent memo- ries that are associated with an array of secondary memories and triggers. The retrieval of primary respondent trauma memories lead to: 1) distressing emotional, physiological and pain re- spondent responses, 2) spontaneous trauma intrusions, 3) faulty appraisals of self, other people, harmless situations and dys- functional behavioral coping, 4) dysfunctional escape, avoid- ance and safety behaviours, and 5) inhibition of positive cur- rently encoded stimuli and responses and incompatible respon- dent-functional-appraisal memories (numbing symptoms). In exposure inhibition therapy, a new cognitive-behavioral treatment (CBT) for chronic PTSD, incompatible primary re- spondent memories are utilized in order to 1) counter numbing (and depressive) symptoms, 2) incorporate the primary respon- dent trauma memory into primary incompatible respondent memories, and 3) inhibit the primary respondent trauma mem- ory with primary incompatible respondent memories. Primary *Many thanks to the Swedish Crime Victims Foundation (Brottsoffer- fonden for s onsorin this stud .  N. PAUNOVIĆ 606 incompatible respondent memories are incompatible to primary respondent trauma memories in several ways: 1) they are asso- ciated with pleasurable emotions and often relaxation responses that are incompatible to anxiety and fear, 2) they may increase positive expectations about the future and motivations to en- gage in meaningful activities which is the opposite to the numbing symptoms in chronic PTSD, 3) they are associated with approach behaviors towards meaningful activities, people and events that are incompatible to trauma-related avoidance, 4) they are associated with incompatible appraisals, e.g. self is worthy and competent, others are trustworthy, and the world is safe. This is in stark contrast to trauma-related appraisals (e.g., self is worthless and incompetent, others are non-trustworthy and the world is very dangerous; Foa & Rothbaum, 1998; Eh- lers & Clark, 2000), and 5) they are probably associated with an attentional bias towards positive stimuli whereas PTSD is cha- racterized by an attentional bias towards trauma-related stimuli (e.g., Williams, Mathews, & MacLeod, 1996). Theoretically, it is postulated that what may be accomplished in exposure inhibition therapy has some important parallels with crucial postulated mechanisms in the emotional processing theory (e.g., Foa & Rothbaum, 1998), and Ehlers and Clarks (2000) cognitive theory of PTSD. In terms of the behav- ioral-cognitive inhibition theory the following is accomplished in exposure inhibition therapy: 1) primary incompatible re- spondent memories and their elements are retrieved which leads to an immediate countering of numbing symptoms, re-apprai- sals and a possible behavioral activation in valued directions, 2) primary respondent trauma memories and their elements are retrieved and immediately incorporated into the primary in- compatible respondent memories, and 3) when 2) is accom- plished the primary incompatible respondent memories and their elements are again retrieved and reinforced in order to inhibit the primary respondent trauma memory and its associ- ated elements. It may be postulated that exposure inhibition therapy is a form of exposure therapy, and that the only therapeutic ingre- dient is the exposure component. This is highly implausible for several reasons. First, very short trauma exposures are used. The purpose is only to retrieve the traumatic memory, not to focus on it for a prolonged time. Second, most of the time is devoted to the imaginal reliving of primary incompatible re- spondent memories. The first variant of exposure inhibition therapy was consid- ered to be the same type of treatment as systematic desensitiza- tion (SD) in a peer review process because they are both based on counterconditioning (Paunović, 1999). The following con- stitute evidence against that exposure inhibition therapy can be compared with SD. First, in SD physiological relaxation re- sponses are elicited and utilized as inhibitors to trauma-related memories and emotions. On the other hand, in exposure inhibi- tion therapy the quality and intensity of meaningful emotions that are elicited constitute much more than just relaxation re- sponses. Second, the appraisals that are associated with physio- logical relaxation responses cannot be compared to the person- ally meaningful appraisals that are associated with the imaginal reliving of personally meaningful experiences of safety, love, happiness, self-efficacy, intimacy etc. Third, the level of trau- ma memory retrieval is different. In SD mild trauma responses are elicited during a very short exposure (usually seconds). In exposure inhibition therapy the trauma exposure is directly focused on the retrieval of primary respondent trauma memo- ries that may continue for several minutes. The purpose is to fully retrieve primary respondent trauma memories that elicit very distressing emotional responses. According to the behavioral-cognitive inhibition theory pri- mary respondent trauma memories may be inhibited when 1) primary respondent trauma memories are retrieved and 2) pri- mary incompatible respondent memories that match central characteristics of 1) become retrieved in the same circum- stances. If the incompatible respondent memories are strong and compelling enough they may be able to inhibit the trauma memories. The exposure inhibition therapy utilizes an imaginal reliving of primary incompatible respondent memories in order to directly counter the numbing symptoms and inhibit primary respondent trauma memories. This is supposed to lead to a decline in PTSD psychopathology on several levels (dysfunc- tional respondent responses, appraisals and behaviors). Primary incompatible respondent memories consist of encoded and stored life events (unconditioned stimuli memories) that elicit incompatible emotional responses of happiness, joy, self-effi- cacy etc (unconditioned response memories) and that have very positive and valued meanings (Paunović, 1999, 2002, 2003). Respondent memories that are associated with a high degree of safety, trust, intimacy, control and self-worth are incompatible to the high degree of danger, lack of trust and intimacy, low control and low self-worth that are often found in clients with chronic PTSD (see Resick & Schnicke, 1992, for these problem areas). Also, pleasure and nurturing are incompatible to the numbing/depressive symptoms and a lack of self-worth. Fur- thermore, mastery (e.g., Benight & Bandura, 2004) is incom- patible to a lack of control and helplessness often found in cli- ents with chronic PTSD. The purpose of this study is to test whether exposure inhibi- tion therapy can be an effective treatment for chronic PTSD. One crucial part of the behavioral-cognitive inhibition theory will be tested. The hypothesis is that primary incompatible respondent memories can be utilized in order to effectively inhibit primary respondent trauma memories. The hypothesis will be confirmed if the following symptoms decrease signifi- cantly in the group that receives treatment immediately, but not in the wait-list control group: PTSD, depressive and anxiety symptoms, negative posttrauma cognitions (self, world, guilt), and an increased coping self-efficacy. Method Overview of the Exposure Inhibition Therapy The exposure inhibition therapy was individual. The sessions lasted 60 - 120 minutes (rarely more than 90 min) once a week up to 9 sessions. The treatment was conducted by the author who at the time of the study was a PhD in clinical psychology with a specialization in cognitive-behavioral therapy for PTSD. Session 1: 1) Establishing treatment goals on PTSD symp- toms and associated symptoms, 2) normalization of PTSD symptoms, 3) description of and discussion about exposure inhibition therapy (rationale and method), and 4) identification of primary incompatible and trauma respondent memories. Session 2 - 9: The following procedure was followed: 1) im- aginal reliving of primary incompatible respondent memories for 15 - 40 minutes (most usually for 15 - 20 minutes), 2) short exposure to primary respondent trauma memories (usually for 3 - 10 minutes), and 3) imaginal reliving of primary incompatible respondent memories for 15 - 40 minutes (most usually for 15 - 20 minutes).  N. PAUNOVIĆ 607 The Identification of Primary Incompatible Respondent Memories The identification of primary incompatible respondent me- mories was conducted with the following questions: Achi ev em en t s 1) What goals have you achieved in your life when you felt most (or very) happy, glad or a sense of well-being [ask for 1 - 3 achievements]? [IF NEEDED]: What are the most impor- tant/meaningful things that you have accomplished in your life? 2) Which one achievement made you feel most happy, glad or a sense of well-being? [IF NEEDED]: Which one of these accomplishments is most important/meaningful? 3) During which [EVENT] did you feel most happy, glad or a sense of well-being when you achieved this goal? [IF NEEDED]: Which [EVENT] was most important/meaningful when you achieved this goal? 4) Identify central details of the chosen incompatible mem- ory: a) Exactly what is happening during [EVENT] that makes you feel most happy, glad or a sense of well-being? Describe details of what is happening that makes you feel most happy, glad or a sense of well-being. [IF NEEDED]: Exactly what is happening during [EVENT] that is most important/meaningful? Describe details of what is happening that is most important/ meaningful. b) Exactly what do you see during [EVENT] that makes you feel most happy, glad or a sense of well-being? Describe details of what you see that makes you feel most happy, glad or a sense of well-being. [IF NEEDED]: Exactly what do you see during [EVENT] that is most important/meaningful? Describe details of what you see that is most important/meaningful. c) Exactly what do you hear during [EVENT] that makes you feel most happy, glad or a sense of well-being? Describe details of what you hear that makes you feel most happy, glad or a sense of well-being. [IF NEEDED]: Exactly what do you hear during [EVENT] that is most important/meaningful? De- scribe details of what you hear that is most important/meaning- ful. d) Exactly what are you doing during [EVENT] that makes you feel most happy, glad or a sense of well-being? Describe details of what you are doing that makes you feel most happy, glad or a sense of well-being. [IF NEEDED]: Exactly what are you doing during [EVENT] that is most important/meaningful? Describe details of what you are doing that is most important/ meaningful. e) Exactly what are other people doing during [EVENT] that makes you feel most happy, glad or a sense of well-being? De- scribe details of what other people are doing that makes you feel most happy, glad or a sense of well-being. [IF NEEDED]: Exactly what are other people doing during [EVENT] that is most important/meaningful? Describe details of what other people are doing that is most important/meaningful. f) How do you feel? Where do you feel [THE EMOTION]? Experience [THE EMOTION]. g) What are you thinking now? Experiences with Family Members or Friends 1) Which family members or friends have you felt most (or very) happy, glad or a sense of well-being with in your life [ask for 1 - 3 people]? [IF NEEDED]: Which persons have been most important to you in your life? 2) With which one of these persons did you feel most happy, glad or a sense of well-being with? [IF NEEDED]: Which one of these people is most important to you? 3) During which [EVENT] did you feel most happy, glad or a sense of well-being when you was with this person? [IF NEEDED]: Which [EVENT] was most important to you with this person? 4) Ask questions 4a-g presented in the paragraph “Achieve- ments”. Activities 1) What activities have made you feel most (or very) happy, glad or a sense of well-being in your life [ask for 1 - 3 activi- ties]? [IF NEEDED]: Which are the most important/meaningful activities that you have engaged in during your life? 2) Which one of these activities made you feel most happy, glad or a sense of well-being? [IF NEEDED]: Which one of these activities is most important/meaningful? 3) During which [EVENT] did you feel most happy, glad or a sense of well-being when you engaged in this activity? [IF NEEDED]: Which [EVENT] was most important/meaningful when you engaged in this activity? 4) Ask questions 4a-g presented in the paragraph “Achieve- ments”. Praise, Appreciation or Affection 1) Which praises, appreciations or affections have you re- ceived from other people that made you feel most (or very) happy, glad or a sense of well-being in your life [ask for 1 - 3 events]? [IF NEEDED]: Which praises, appreciations or affec- tions are the most important ones that you have experienced in your life? 2) Which one of these praises, appreciations or affections made you feel most happy, glad or a sense of well-being? [IF NEEDED]: Which one of these praises, appreciations or affec- tions is most important meaningful? 3) During which [SPECIFIC OCCASION] did you feel most happy, glad or a sense of well-being when you received this praise, appreciation or affection? [IF NEEDED]: During which [SPECIFIC OCCASION] did you receive this most important/ meaningful praise, appreciation or affection? 4) Ask questions 4a-g presented in the paragraph “Achieve- ments”. Other Life Event 1) During which other [EVENTS, SITUATIONS, EX- PERIENCES] did you feel most (or very) happy, glad or a sense of well-being in your life [ask for 1 - 3]? [IF NEEDED]: Which other [EVENTS, SITUATIONS, EXPERIENCES] are most important/meaningful that you have had in your life? 2) During which one of these [EVENTS, SITUATIONS, EXPERIENCES] did you feel most happy, glad or a sense of well-being? [IF NEEDED]: Which one of these [EVENTS, SITUATIONS, EXPERIENCES] is most important/meaning- ful? 3) During which [SPECIFIC OCCASION] did you feel most happy, glad or a sense of well-being in this [EVENT, SITUA- TION, EXPERIENCE]? [IF NEEDED]: Which [SPECIFIC OCCASION] was most important during the [EVENT, SITUA- TION, EXPERIENCE]? 4) Ask questions 4a-g presented in the paragraph “Achieve- ments”. Instructions for the Imaginal Reliving of Incompatible Memories Clients are instructed to close their eyes and to constantly focus on the retrieved primary incompatible respondent memo- ries during 15 - 45 min. (most usually for 15 - 20 min.). See xamples in Table 1. The therapit helps the client to constantly e s  N. PAUNOVIĆ 608 Table 1. Examples of primary inco m p atible respondent memo r i es in crime victims with chronic postt raumatic stress disorder. Type of life event Primary respondent memory elements (with some secondary memory elements) Events with friends Meeting a friend the first time Sees one’s friend, the eye-contact with him; hears oneself and him introducing one another to each other; sees his “shiny” smile; hears his laughter; feels “incredibly” glad On vacation with friends Sees a restaurant, a harbour, people passing buy, one’s friends; feels the taste of food; sees the sunset and feels the warmth of the sun; sees and hears oneself talking with friends, and their praising comments Invitation to live with friends Sees and hears one’s friend say “I would very much like you to come and live with me and my boy- friend”; sees the smile of one’s friend and her boyfriend; feels very good; thinks “it feels like home” Happy meeting with friends Sees several of one’s friends; hears questions from several of them; feels how one friend hugs oneself; sees and hears several happy moments with one’s friends; feels glad; thinks “they are wonderful” Intimate experiences with partner A wedding moment Sees parents sit beside one’s spouse; sees people dance and have fun; hears the music; feels how one’s spouse strokes one’s cheek, how oneself kisses one’s spouses forehead; sees the loving gaze; feels happy On a boat trip with partner Feels how oneself steers the boat in a circle; sees and hears the partner laugh at oneself; sees the sea water and the sunshine; hears the engine and the propeller thud on the water; feels great fun First announcement of love Sees and hears one’s spouse for the first time say “I love you”; feels how one’s spouse and oneself lie in bed, feels hugs and kisses; sees a warm and loving face on spouse; feels one’s smile; feels happy Sexual experience Sees one’s own body; hears one’s own pleasurable sound; feels the caressing from one’s partner, one’s own pleasure-inducing movements, a good feeling in the stomach and the lower part of the body Loving moments with one’s children a n d f am i l y At childbirth with one’s child Sees details of one’s child’s physical appearance; hears one’s child’s breathing; feels how oneself hugs the child; feels the child’s smell; feels an immense joy, warmth and pride; thinks loving thoughts Socializing with one’s children Sees the smiles of one’s children; hears their laughter, jokes about oneself, one’s own joking response; feels very glad; thinks “i have two happy and considerate children” On vacation with family Sees and feels the water waves at the beach; hears the waves; feels oneself jump when waves are ap- proaching; feels how oneself lies in the water; sees one’s child lying in the sun; feels “comforting” Barbecuing with family Sees family members preparing the barbecue; sees the fire and the pig being barbecued; sees everybody’s “hungry looks” on the pig; hears the fire sparkle; feels the taste of the meat Meaningful moments wi th family members or kin Affection from mother Feels a hug from one’s mother; hears her say she is proud of oneself; feels how oneself hugs and lifts one’s mother; feels happy in one’s “voice and heart” Re-union with relatives Sees one’s grandparents, aunts, uncles, their families, cousins; hears oneself and them talking loudly to each other; sees how they all sit together in a ring; feels happy, thinks “I love them” Family visit with partner Sees one’s partner overwhelmingly glad and one’s relatives showing the partner appreciation and giving her hugs; hears one’s aunt speak to partner; feels glad and happy; thinks “it’s immensely important” Personal moment with sibling Sees one’s sibling at dinner in one’s home; hears appreciating comments from one’s sibling; sees and feels how oneself cooks dinner and makes coffee for one’s sibling; feels “closeness” Activities, nature experiences and animals Skiing in nature and dinner Sees a mountain, snow, one’s company and friend skiing in front of oneself; hears the snow creak; feels the skiing movements; tastes a soup at dinner; sees one’s friends gaze at self; hears own and others laugh Experience in nature Sees a fog from the sea, broad-leaved trees turn white and fluffy, the sunrise and a rainbow, a perception of as if it is raining gold-dust; hears the quietness and stillness; feels harmonious First encounter with one’s dog Sees how one’s dog sits in one’s lap; sees the details of the dogs appearance; hears the dogs breathing; feels how the dog switches positions; feels very glad Mountain-biking with sibling Feels the movements while biking and the rain on the face; sees the beautiful mountain landscape; hears the rain falling and the wheels spinning; sees one’s sibling biking in front of oneself; feels “fun” Primary responde nt memories that also co nstitute primary reinforcement consequence memories Oral presentation at school Hears the applause; sees gazes of specific persons in the audience; hears the teachers appreciating com- ments; sees the excellent grade on paper, feels good in the stomach and chest; thinks “I enjoy this” Prepared a meal to friends Sees the meal, beverage and spices; hears one’s friend say very appreciating words about the meal; sees one’s friend being glad and pleased; hears the friend say “i am very glad to see you” Winning a soccer game Sees and hears when the whole team gathers and talks to each other in an encouraging fashion; sees the winning penalty; sees and hears the immense joy of the players and the supporters; feels happy First praise of singing ability Hears oneself sing; sees the enjoying faces of people in the audience; hears immediately afterwards a person extensively praising one’s singing; feels glad; thinks “I really have a talent for this”  N. PAUNOVIĆ 609 attend to the primary memory details by repeating them aloud. See the following example: “Your spouse is for the first time saying that she loves you, you see and hear her say “I love you”…(pause about 10 - 20 sec)…you feel how you lie in bed and you see her lie beside you...(pause about 5 - 15 sec)…you feel how you are hugging and kissing her and how she hugs and kisses you…(pause about 10 - 30 sec)…you see the warm and loving face of your spouse...(pause about 5 - 15 sec)…you feel your own smile stretching on your face while you are look- ing at her warm and loving face...(pause about 5 - 15 sec)…you feel happy…(pause about 5 - 15 sec)…[REPEAT INSTRUC- TIONS FOR 5 - 10 min]. Some Important Considerations During the imaginal reliving of incompatible memories that follows trauma exposure pauses between the therapist’s utter- ances of central details usually need to be shortened. Clients with PTSD often have concentration problems in this transition due to the distress that trauma exposure elicits. Some traumatized people may prefer to relive their pleasur- able memories without specific instructions from a therapist (e.g., intimate interpersonal experiences). In such cases one viable option is to provide more general instructions for the imaginal reliving, and let the person fill in the specific details. Sometimes it may be difficult for a client to come up with one specific occasion for events that have occurred repeatedly in the same or similar situations. In such cases a generic event may be relived that includes details from several events. The client should be instructed to disclose eventual new im- portant details that are remembered from an event. If these details are primary to the event they should be incorporated into the imaginal reliving (both incompatible and trauma-related). In addition, the therapist may occasionally ask clients for more central details. Some questions about central details of events may be ir- relevant. For instance, if an event doesn’t involve other people then question 4e is not relevant. In addition, an event is en- coded and stored in a certain way, and the retrieval of the cor- responding memory will contain the same features. Also, smell and taste are sensations that are not inquired about, but may be central components of some incompatible memories. It is usually easier to identify the most central details of in- compatible memories with one’s eyes closed. Some clients may not respond to questions about predeter- mined specific emotions (e.g., happy, glad or a sense of well-being). If so, the client may be asked to list his or her most important or meaningful emotions. These emotions can then be incorporated into the questions about incompatible memories. If any incompatible memories are associated with strong negative meanings or feelings, chose if possible other incom- patible memories that are only associated with incompatible meanings and feelings. If no such memories can be found, chose the ones that are possible to identify. Trauma Exposure During the first two sessions the therapist used only imaginal exposure to central trauma memories. The client’s were in- structed to retell the traumatic event one time which usually lasted 3 - 10 minutes. From session 3 and onwards the therapist used two retrieval tools in the following order: 1) exposure to video scenes from movies that match the cli- ent’s traumatic event (e.g., a rape victim was exposed to a rape scene), if it was accepted by the client. The client was in- structed to signal by raising a finger when the exposure led to a distress level of 7 - 8 on a 0 - 10 scale (0 = not at all distressing, 5 = moderately distressing, 10 = very distressing). The video exposure was then immediately ended (usually after 5 - 30 sec- onds). 2) The client was instructed to immediately close the eyes and retell the traumatic event one time (usually 3 - 10 minutes). If the client started to avoid the traumatic memory the therapist helped the client to focus on the memory until the most central details were retrieved and re-told. The client was also instructed that this procedure could be ended at any point if the client wished so. Homework Homework consisted of listening daily to an audiotaped re- cording of the last session. At the end of session 9 future appli- cations of the exposure inhibition therapy was discussed. Design The design consisted of randomization to either a group that received exposure inhibition therapy immediately, or a wait-list control group (WL) that waited 2.5 months before they received the same treatment if they still fulfilled the inclusion criteria or suffered from subthreshold PTSD symptoms. The measures were administered before and after treatment/the waiting period, and at a follow-up assessment 3 months after the end of the treatment in the treatment group. Inclusion Criteria The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) 18 - 60 yrs of age. 2) An interpersonal traumatic event according to the DSM- IV criteria for PTSD (APA, 1994). 3) The index trauma must have occurred 12 months or longer since the first screening interview. 4) Fulfilling the DSM-IV criteria for chronic PTSD. 5) The severity of PTSD must be at least 2 on the CAPS global severity rating scale (0 - 4). 6) Chronic PTSD must be the primary diagnosis. 7) If psychotropic medication is used a) the dosage must be constant during at least 2.5 months, and b) the same dosage must be kept during the study. 8) Accept randomization to either treatment immediately or to wait 2.5 months and then receive treatment if needed. 9) Accept to participate in all the assessments with the provi- sion that they can drop out at any time if they wish so. 10) No organic brain disorder. 11) No psychotic disorder. 12) No current drug or alcohol abuse. 13) No serious suicide risk. 14) No currently ongoing psychotherapy. Recruitment and Therapy Site Clients were recruited from 1) a data base of registered vio- lent crimes at the Police department in the Stockholm county of Sweden, and 2) psychiatric clinics in the same county. The following types of traumatic events were targeted for recruit- ment: manslaughter/murder attempt, physical assault, rape, sexual coercion and robbery. The study was conducted during August 2001-May 2004 at  N. PAUNOVIĆ 610 Danderyds hospital, Danderyd municipality of Stockholm in Sweden, and at the authors’ private clinic in Stockholm city. Assessments Clinical interviews. The clinician administered PTSD scale (CAPS; Blake et al., 1995; 1997; Paunović & Öst, 2005) was used to assess PTSD symptoms according to the DSM-IV (APA, 1994) criteria, and the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule-IV (ADIS-IV; Brown, DiNardo, & Barlow, 1994) to assess other anxiety disorders and other disorders with similar symptomatology. Self-report measures: 1) Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES- R; Weiss & Marmar, 1997) consist of intrusion, avoidance and arousal PTSD symptom subscales, 2) PTSD Checklist (PCL; Blanchard, Jones-Alexander, Buckley, & Forneris, 1996; Weathers, Litz, Herman, Huska, & Keane, 1992) measures PTSD according to the DSM-IV criteria for PTSD, 3) Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961; Beck, Steer, & Garbin, 1988) measures depres- sive symptoms, 4) Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck, Epstein, Brown, & Steer, 1988) measures anxiety symptoms, 5) The coping Self-Efficacy scale (CSE; Benight, Ironson, & Durham, 1999; Benight, Freyaldenhoven, Hughes, Ruiz, & Zoschke, 2000; Benight, Flores, & Tashiro, 2001) measures coping self-efficacy beliefs in traumatized crime victims, and 6) Post- traumatic Cognitions Inventory (PTCI; Foa, Ehlers, Clark, To- lin, & Orsillo, 1999) measures posttraumatic cognitions of the self (PTCI-self subscale), the world (PTCI-world subscale), and guilt (PTCI-guilt subscale). Results Demographics The demographics in the therapy vs. wait-list control group were: men 6 vs. 6, women 8 vs. 9, living with a partner 6 vs. 8, divorced 6 vs. 5, unmarried 2 vs. 1, widow 0 vs. 1, elementary school 4 vs. 5, high school 8 vs. 9, university 2 vs. 1, has a job/studies 9 vs. 11, part-time work/study 1 vs. 1, full-time work/study 4 vs. 3, age M (SD) = 37.1 (13.8) vs. 37.3 (10.2) yrs. Traumatic Events Duration of months (SD) since the index trauma in the ther- apy vs. wait-list group were 112.1 (83.4) vs. 119.8 (114.6). The index trauma that most of the clients relived as part of their PTSD symptoms was most often not the last traumatic event they had experienced. The Life Events Checklist from the CAPS was used in order to analyze how many clients had experienced, and/or witnessed each type of traumatic event. The results were as follows: se- vere assault 18, rape 11, childhood traumatic events 8, man- slaughter attempt 6, assault 5, sexual assault 4, witnessed as- sault 3, attempted rape 2, armed robbery 1, information about a friend’s death 1, rape by a group 1, witnessed attempted murder 1, witnessed suicide 1, witnessed murder 1, traffic accidents 1, serious accidents 1, other fatal accidents 1, war trauma 1. Drop-Outs One client in the treatment group and one in the WL-group didn’t conduct the assessments after the treatment vs. the wait-list period. Two clients in the WL-group didn’t conduct the assessments after treatment. Three clients in the treatment group didn’t conduct the assessments at the 3 month follow-up. There were no significant differences between the groups on the assessment measures mean values before the treatment/ wait-list period. Number of Sessions The number of sessions varied between 3 and 9 with a mean value of 7.2 (SD = 2.8) in the treatment group and 7.3 (SD = 2.0) in the wait-list group. Interview Measure Results on the CAPS are presented in Table 2. ANOVA computations before-after treatment showed significant group-, time- and interaction effects. It is evident from Table 2 that these differences are due to a significantly larger decline of PTSD symptoms in the group that received treatment immedi- ately than in the wait-list control group. These results were confirmed by indeptendent t-tests (p < .0001). CAPS scores decreased significantly in the wait-list group after the waiting period-after treatment (p < .0001). Self-Report Measures ANOVA before-after treatment showed significant group-, time- and interaction effects for the PCL, IES—R subscales, BAI and BDI. It is evident from table 2 that these differences are due to significantly larger improvements in the treatment group than in the wait-list group on all these measures. Inde- pendent t-tests confirmed that the treatment group was signifi- cantly more improved than the wait-list group on all self-report measures of PTSD, depression and anxiety (p < .0001). T-tests showed that whereas the treatment group significantly im- proved on these measures before-after treatment (p < .0001) the wait-list group did not significantly improve on any of these measures.The treatment resulted in a significant improvement on these measures in the wait-list group after the waiting pe- riod—after treatment (p < .0001). Results of the ANOVA before-after treatment on the CSE and the PTCI self and others subscales showed significant group-, time- and interaction effects. From Table 2 it is evident that these differences are due to an improvement in the treat- ment group on these measures whereas the wait-list group didn’t show significant improvements after the waiting period. Independent t-tests confirmed that the treatment group was significantly more improved than the wait-list group after the treatment on the CSE, PTCI-self and PTCI-others (p < .0001). T-tests with the treatment group showed significant improve- ments on the PTCI-guilt (p <.05) before-after the treatment. T-tests with the wait-list group showed no significant differ- ences before-after the wait- list period on any measures. Results after the waiting period-after treatment in the wait-list group showed that coping self-efficacy cognitions increased signifi- cantly (p < .0001) and dysfunctional posttrauma cognitions as measured by the PTCI subscales decreased significantly as a result of the treatment (PTCI-self and PTCI-others, p < .0001; PTCI-guilt, p < .05). Treatment Efficacy The efficacy of the treatment was very high for PTSD and associated psychopathology (see the last column in Table 2). The following results are noticeable: the average treatment efficacy for the PTSD symptoms was 3.28, for posttrauma cog-  N. PAUNOVIĆ 611 Table 2. Mean values (SD) on PTSD symptoms and associated psychopathology, ANOVA F-values and effect size of exposure inhibition therapy (EIT) as a treatment for chronic PTSD in crime victims. Assessment (SD) ANOVA F-values* Measure Time EIT (N = 14) WL (N = 15)Effect type Pre-post Pre-f-up Post- f-up ES CAPS Pre Post F-up 86.2 (13.8) 21.8 (14.1) 20.3 (16.8) 88.0 (16.9) 81.4 (14.4) 13.2 (8.0) G T I 29.3d 123.4d 81.5d 0.1 419.2d 1.8 0.3 13.8c 7.1 3.53 PCL Pre Post F-up 61.8 (11.8) 28.1 (6.0) 25.5 (7.1) 63.7 (10.6) 63.1 (13.0) 23.8 (6.8) G T I 31.7d 68.4d 64.0d 0.1 243.9d 0.5 0.5 4.1 0.0 3.30 IES-R intrusion Pre Post F-up 21.9 (5.0) 5.6 (4.7) 4.8 (4.4) 19.8 (5.0) 18.7 (6.4) 2.3 (1.5) G T I 8.3b 124.2d 95.5d 1.2 222.9d 0.8 0.9 7.4b 5.1a 2.62 IES-R avoidance Pre Post F-up 19.8 (5.5) 4.4 (3.1) 2.7 (2.4) 19.1 (3.8) 18.1 (7.1) 2.4 (2.1) G T I 17.3d 45.4d 35.1d 0.6 170.2d 0.7 0.0 8.8b 0.2 3.60 IES-R arousal Pre Post F-up 16.3 (3.9) 4.8 (2.8) 3.4 (2.6) 15.6 (3.2) 15.5 (5.1) 4.1 (4.1) G T I 13.6c 92.4d 87.9d 0.0 133.4d 0.2 0.2 3.7 0.0 3.34 BAI Pre Post F-up 22.9 (10.9) 8.2 (5.1) 7.4 (7.3) 25.8 (10.0) 26.4 (10.5) 5.5 (3.7) G T I 10.4b 25.8d 30.8d 0.0 68.7d 0.5 0.3 10.4b 0.4 1.82 BDI Pre Post F-up 30.6 (12.1) 9.1 (6.2) 7.7 (5.8) 30.4 (9.6) 28.9 (10.4) 7.5 (4.0) G T I 8.0b 50.9d 38.5d 0.0 140.2d 0.1 0.0 1.8 0.1 2.06 CSE Pre Post F-up 131.6 (33.9) 241.8 (45.2) 256.6 (51.0) 146.7 (29.2) 151.9 (49.3) 248.9 (27.6) G T I 7.2b 72.0d 59.7d 0.0 149.4d 0.9 0.2 4.5a 0.1 3.08 PTCI (self) Pre Post F-up 94.3 (29.8) 44.7 (13.3) 40.3 (11.8) 99.1 (21.2) 97.6 (28.9) 40.0 (10.7) G T I 11.9b 37.6d 33.3d 0.0 123.5d 0.3 0.2 6.4a 1.3 2.49 PTCI (others) Pre Post F-up 38.5 (7.0) 19.2 (5.0) 15.9 (4.4) 37.6 (7.3) 38.7 (8.9) 14.6 (4.3) G T I 13.2c 73.2d 91.5d 0.4 107.4d 0.1 0.1 12.7b 0.4 2.67 PTCI (guilt) Pre Post F-up 19.9 (8.4) 11.4 (4.9) 10.4 (4.3) 17.5 (6.3) 18.1 (7.7) 9.0 (2.4) G T I 0.7 15.3c 20.1d 1.1 42.6d 0.1 1.0 4.8a 0.0 1.06 *G = group effect, T = time effect, I = interaction effect in ANOVA. ap < .05, bp < .01, cp < .001, dp < 0.0001. nitions 2.07, and for all symptoms combined 2.69. Clinically Significant Improvement The CAPS and the BDI were used to compute number of cli- ents in each group that no longer met criteria for PTSD and depression before and after the treatment and at 3-months fol- low-up. Three empirically derived cut-off criteria with various degrees of strictness (44, 39 27) were used for the CAPS (see Blanchard et al., 1995; Weathers, Ruscio, & Keane, 1999). The cut-off score for the BDI was 10 (see Foa, Dancu et al., 1999). When the least strict cut-off criteria was used (44 on the CAPS), no client in the treatment group fulfilled a PTSD diag- nosis any more after the treatment and at 3 months follow-up. All clients in the wait-list group fulfilled a PTSD diagnosis after the wait-list period and before the treatment irrespective of which cut-off criteria was used. When the moderate cut-off criteria was used (39) the majority of the clients in the treat- ment group (85%) and the wait-list group (85%) no longer ful- filled a PTSD diagnosis after the treatment. At 3 months’ fol- low-up the majority of the clients in the treatment group (85%) no longer fulfilled a PTSD diagnosis. When the most strict cut-off criteria for a PTSD diagnosis (27) was used, the major- ity of the client’s in the treatment group (61%) and about half of the clients in the wait-list group (46%) no longer fulfilled a PTSD diagnosis after the treatment. At 3-month’s follow-up, the majority of the clients in the treatment group (73%) no longer fulfilled a PTSD diagnosis. The majority of the clients in the treatment group no longer fulfilled a depression diagnosis after the treatment (85%) and at the 3-months follow-up (73%). Only one client in the wait-list group no longer fulfilled a de- pression diagnosis after the wait-list period. The majority of the clients in the wait-list group no longer fulfilled a depression  N. PAUNOVIĆ 612 diagnosis after the treatment (69%). There were no significant differences between the groups regarding the proportion of clients that no longer fulfilled a PTSD and depression diagnosis after the treatment. Discussion The purpose of this study was to test exposure inhibition therapy as a psychological treatment for chronic PTSD in a randomized pilot study. Results showed that the group that received exposure inhibition therapy became significantly more improved than the wait-list group on PTSD, anxiety and de- pressive symptoms. The wait-list group didn’t show any sig- nificant improvement after the waiting period before they re- ceived the treatment. After the wait-list group received the treatment a significant improvement was evident on PTSD, anxiety and depressive symptoms. The results were maintained at a 3-months follow-up in the treatment group. The treatment group improved significantly more than the wait-list group on coping self-efficacy and posttraumatic cogni- tions (self, others and guilt). No significant improvements occurred in the wait-list group after the waiting period. When the wait-list group received treatment a significant improve- ment occurred on all cognitive measures. The efficacy of the treatment was large, especially with re- gard to PTSD symptoms. These results are closely followed by large improvements on most cognitive measures, except guilt that per definition also improved substantially. The treatment efficacies for anxiety and depressive symptoms were also large. These results indicate that exposure inhibition therapy may be a potentially effective treatment for chronic PTSD and associated psychopathology. On the other hand, this study must be repli- cated with a more rigorous design that fulfills all of the golden criteria for a randomized controlled study (Foa & Meadows, 1997). No client in the treatment group fulfilled a PTSD diagnosis after the treatment when the least strict cut-off criteria was used. All clients in the wait-list group fulfilled a PTSD diagnosis after the waiting period before the treatment. When the strictest cut-off criteria was used, the majority of the clients in the treatment group and about half of the clients in the wait-list group no longer fulfilled a PTSD diagnosis after treatment. At the 3-months follow-up the majority of all clients in the treat- ment group no longer fulfilled a PTSD diagnosis. The majority of clients in the treatment group no longer fulfilled a depression diagnosis after treatment whereas all but one client fulfilled a depression diagnosis in the wait-list group after the waiting period. The majority of clients in the wait-list group no longer fulfilled a depression diagnosis after treatment. The improve- ment on depressive symptoms was maintained at the 3 month follow-up in the treatment group. This study shows that exposure inhibition therapy can be an effective treatment for chronic PTSD, associated psychopa- thology and cognitive factors that are postulated to play a role in the development and maintenance of chronic PTSD. In exposure inhibition therapy the primary purpose is to iden- tify and utilize incompatible primary respondent memories in order to inhibit primary trauma-related memories. However, other primary memory elements are also associated with pri- mary respondent memories. Incompatible as well as trauma- related respondent memories are associated with appraisal, behavioral response and consequence memory elements (see Paunović, 2010). In some cases, respondent memories may also be characterized as consequence memories (see examples at the bottom of Table 1). Although the primary purpose of exposure inhibition therapy is to inhibit primary trauma-related respon- dent memories by primary incompatible respondent memories, other types of retrieved incompatible memory elements may play a crucial role in the amelioration of trauma-related psy- chopathology. The retrieval of incompatible primary appraisal memories may inhibit trauma-related appraisals if they match relevant themes of the trauma-related psychopathology. Also, incompatible primary consequence memories may inhibit trauma-related consequence memories if they match the rele- vant trauma psychopathology themes. A sense of “mental defeat” during a traumatic event is related to an inferior outcome in exposure therapy for chronic PTSD (Foa et al., 1998). Mental defeat may be effectively countered by imaginally reliving self-efficacy experiences that don’t need to be trauma-related. The retrieval and reliving of such memo- ries may be able to inhibit the sense of mental defeat that is experienced during the retrieval of primary trauma memories. Such imaginal reliving may also be able to inhibit emotions such as helplessness. A complement to exposure inhibition therapy may be to utilize imagery rescripting techniques during the trauma memory retrieval (e.g., Arntz, Tiesema, & Kindt, 2007). A few PTSD clients in the present study had difficulties in maximizing their emotional engagement in the reliving of in- compatible memories. There may be several reasons for this. First, strong incompatible emotional experiences may be lack- ing. Second, some clients may be so emotionally numb that it is difficult for them to engage emotionally in incompatible memo- ries. Third, some clients may have negative beliefs about what they are capable of. Such negative beliefs hinder them from engaging in the process fully. Fourth, some people may also be in an acute crisis or are too stressed by current life demands that they may chose not to engage in such a process fully. This study has several methodological limitations. First, an independent assessor was not used. The assessor was both the therapist and the author of the current study. One prevailing definition of what constitutes an independent assessor is that the assessor should not also be a therapist in the same study (Foa & Meadows, 1997). Second, only one therapist was used. The results of the exposure inhibition therapy for chronic PTSD need to be replicated by other therapists. Third, a quite small sample was used. Fourth, no long follow-up evaluations were conducted. Brewin (2006) compares the accommodation model with the activation-deactivation model. According to the accommoda- tion model therapy modifies structures in memory that give rise to negative beliefs (e.g., Beck, Emery, &Greenberg, 1985; Foa, Steketee, & Rothbaum, 1989). On the contrary, the activa- tion-deactivation model assumes that effective therapy is due to the deactivation or blocking of negative memories and the acti- vation and creation of positive memories. The key element of effective CBT is that positive memories should win the re- trieval competition over negative memories. Exposure inhibi- tion therapy is developed from the behavioral-cognitive inhibi- tion (BCI) theory (Paunović, 2010). According to the BCI the- ory trauma-related respondent memories are inhibited by in- compatible respondent memories when the latter are 1) strong enough, and 2) retrieved in the same circumstances as trauma- related memories. If positive memories are retrieved before trauma memories may not be an indication of effective CBT. The strength of the emotional responses to the two retrieved opposing memories is crucial in determining which types of  N. PAUNOVIĆ 613 memories may win the inhibition competition. If positive memories are retrieved first, but only function as retrieval trig- gers to very distressing trauma memories, then the retrieval competition is not the most useful indicator of treatment suc- cess. On the other hand, a retrieval of positive memories, suc- ceeded by an absence of emotional distress following trauma memory retrieval, is an indication of effective CBT. According to the BCI theory, the modifications of respondent-functional- appraisal memory structures only constitute indications of whether a successful inhibition has taken place. Functional inhibition is the therapeutic process that leads to various types of outcomes (i.e., memory structures and the emotional inten- sity associated with various types of memories). One important clinical observation is that trauma and in- compatible memory retrieval in exposure inhibition therapy may retrieve important trauma sequel memories that may indi- cate incompatible meanings to trauma-related appraisals. For example, a client had for the first time in 30 years remembered that an adult had expressed concern for her towards her father (the perpetrator) when she was a child. The retrieved memory of this event constituted evidence that there are caring people in the world and that somebody had noticed her suffering. This information stands in stark contrast to the belief nobody cares. The client’s re-appraisal that “somebody cares” as a response to this memory retrieval can be utilized in cognitive techniques with the goal of modifying the belief “nobody cares”. However, the client came to this conclusion herself without the use of any formal cognitive techniques. The imaginal reliving of primary incompatible respondent memories may lead to an increased behavioral activation in valued directions. For example, when a client remembered a specific event with a dear friend she immediately contacted him for the first time in several years. In a future study exposure inhibition therapy ought to be compared to exposure therapy in a randomized controlled trial. Exposure therapy is considered to be the state-of-the-art treat- ment for chronic PTSD (see Foa, Keane, Friedman & Cohen, 2009). It is hypothesized that exposure inhibition therapy 1) is equally effective as exposure therapy in the treatment of chronic PTSD in general, 2) is significantly more effective than exposure therapy in treating numbing symptoms, 3) is signifi- cantly more effective than exposure therapy in treating post- traumatic cognitions that are directly countered by the imaginal reliving of incompatible memories, 4) is significantly more preferable than exposure therapy by therapists and clients, and 5) is significantly less distressing than exposure therapy. Ex- posure therapy is a painful treatment. Clients are asked to ex- perience pain for a prolonged time over and over again, until the fear and anxiety eventually subsides. The emotional pain may not subside during the sessions. Habituation within the sessions has not been shown to be a necessary precondition for a successful outcome (Jaycox, Foa, & Morral, 1996). Exposure inhibition therapy, on the other hand, is a much less distressing treatment for chronic PTSD since the trauma exposure is mini- mal compared to exposure therapy. In addition, the client is emotionally engaged in meaningful and pleasurable memories for a prolonged time. Exposure inhibition therapy may be an effective treatment for chronic PTSD as a result of type-2 traumatic events (Terr, 1991). The imaginal reliving of primary incompatible memories may result in 1) a significantly higher emotional regulation capability that may be used for this purpose instead of or com- plementarily to other emotional regulation techniques, and 2) a countering of dysfunctional interpersonal schemas (Cloitre, Cohen, & Koenen, 2006). Acknowledgements Thanks to Professor Lars-Göran Öst, Department of Psy- chology, Stockholm University, Sweden for the help with the statistical computations by the statistical software analysis pro- gram SPSS. References American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. Arntz, A., Tiesema, M., & Kindt, M. (2007). Treatment of PTSD: A comparison of imaginal exposure with and without imagery rescript- ing. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 38, 345-370. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2007.10.006 Beck, A. T., Emery, G., & Greenberg, R. L. (1985). Anxiety disorders and phobias: A cognitive perspective. New York: Basic Book Beck, A. T., Epstein, N., Brown, G., & Steer, R. A. (1988). An inven- tory for measuring clinical anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clini- cal Psychology, 56, 893-897. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.56.6.893 Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Garbin, M. G. (1988). Psychometric prop- erties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of eva- luation. Clinical Ps y c hology Review, 8, 77-100. doi:10.1016/0272-7358(88)90050-5 Beck, A. T., Ward, C. H., Mendelson, M., Mock, J., & Erbaugh, J. (1961). An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 4, 561-571. Benight, C. & Bandura, A. (2004). Social cognitive theory of posttrau- matic recovery: The role of perceived self-efficacy. Behaviour Re- search and Therapy, 42, 1129-1148. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2003.08.008 Benight, C., Flores, J., & Tashiro, T. (2001). Bereavement coping self-efficacy in cancer widows. Death Studies, 25, 97-125. Benight, C., Freyaldenhoven, R. W., Hughes, J., Ruiz, J. M., & Zo- schke, T. A. (2000). Coping self-efficacy and psychological distress following the Oklahoma city bombing. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30, 1331-1344. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02523.x Benight, C. C., Ironson, G., & Durham, R. L. (1999). Psychometric properties of a hurricane coping self-efficacy measure. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 12, 379-386. doi:10.1023/A:1024792913301 Blake, D. D., Weathers, F. W., Nagy, L. M., Kaloupek, D. G., Charney, D. S., & Keane, T. M. (1997). Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-IV. Boston: National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Dis- order, Behavioral Science Division at Boston VA Medical Center and Neurosciences Division at West Haven VA Medical Center. Blake, D. D., Weathers, F. W., Nagy, L. M., Kaloupek, D. G., Gusman, F. D., Charney, D. S., & Keane, T. M. (1995). The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 8, 75-90. doi:10.1002/jts.2490080106 Blanchard, E. B., Hickling, E. J., Taylor, A. E., Forneris, C. A., Loos, W., & Jaccard, J. (1995). Effects of varying scoring rules of the cli- nician-administered PTSD scale (CAPS) for the diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder in motor vehicle accident victims. Be- haviour Research and Therapy, 33, 471-475. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(94)00064-Q Blanchard, E. B., Jones-Alexander, J., Buckley, T. C., & Forneris, C. A. (1996). Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL). Be- haviour Research and Therapy, 34, 669-673. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2 Brewin, C. (2006). Understanding cognitive behaviour therapy: A re- trieval competition account. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 765-784. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2006.02.005 Brown, T. A., DiNardo, P. A., & Barlow, D. H. (1994). Anxiety Disor- ders Interview for DSM-IV. Phobia and Anxiety Disorders Clinic Center for Stress and Anxiety Disorders University at Albany State University of New York.  N. PAUNOVIĆ 614 Cahill, S. P., Rothbaum, B. O., Resick, P., & Follette, V. M. (2009). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adults. In E. B. Foa, T. M. Keane, M. J. Friedman and J. A. Cohen (Eds.), Effective treatments for PTSD: Practice guidelines from the International Society for Trau- matic Stress Studies (pp. 139-222). New York: Guilford Press. Cloitre, M., Cohen, L. R. & Koenen, K. C. (2006). Treating survivors of childhood abuse: Psychotherapy for the interrupted life. New York: Guilford Press. Ehlers, A. & Clark, D. M. (2000). A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38, 319-345. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00123-0 Ehlers, A., Clark, D. M., Dunmore, E., Jaycox, L., Meadows, E., & Foa, E. B. (1998). Predicting response to exposure treatment in PTSD: The role of mental defeat and alienation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 11, 457-471. doi:10.1023/A:1024448511504 Foa, E. B., Dancu, C. V., Hembree, E. A., Jaycox, L. H., Meadows, E. A., & Street, G. P. (1999). A comparison of exposure therapy, stress inoculation training, and their combination for reducing posttrau- matic stress disorder in female assault victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67, 194-200. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.67.2.194 Foa, E. B., Ehlers, A., Clark, D. M., Tolin, D. F., & Orsillo, S. M. (1999). The posttraumatic cognitions inventory (PTCI): Develop- ment and validation. Psychological Assessment, 11, 303-314. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.11.3.303 Foa, E. B., Keane, T. M., Friedman, M. J., & Cohen, J. A. (2009). Ef- fective treatments for PTSD: Practice guidelines from the Interna- tional Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. New York: Guilford Press. Foa, E. B., & Meadows, E. A. (1997). Psychosocial treatments for post-traumatic stress disorder: A critical review. In J. Spence, J. M. Darley and D. J. Foss (Eds.), Annual Review of Psychology (Vol. 48, pp. 449-480). Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews. Foa, E. B., & Rothbaum, B. O. (1998). Treating the trauma of rape: Cognitive-behavioral therapy for PTSD. New York: The Guilford Press. Foa, E. B., Steketee, G., & Rothbaum, B. O. (1989). Behavioral/cognitive conceptualizations of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behavior Ther- apy, 20, 155-176. doi:10.1016/S0005-7894(89)80067-X Jaycox, L. H., Foa, E. B., & Morral, A. R. (1998). Influence of emo- tional engagement and habituation on exposure therapy for PTSD. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66, 185-192. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.66.1.185 Paunović, N. (1999). Exposure counterconditioning (EC) as a treatment for severe PTSD and depression with an illustrative case. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 30, 105-117. doi:10.1016/S0005-7916(99)00010-5 Paunović, N. (2002). Prolonged exposure counterconditioning (PEC) as a treatment for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder and major de- pression in an adult survivor of repeated child sexual and physical abuse. Clinical Case Studies, 1, 148-170. doi:10.1177/1534650102001002004 Paunović, N. (2003). Prolonged exposure counterconditioning as a treatment for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Anxi- ety Disorders, 17, 479-499. doi:10.1016/S0887-6185(02)00233-5 Paunović, N. (2010). Behavioral-cognitive inhibition theory: Conceptu- alization of posttraumatic stress disorder and other psychopathology disorders. Psychology, 1, 349-366. doi:10.4236/psych.2010.15044 Paunović, N. & Öst, L.-G. (2005). Psychometric properties of a Swed- ish translation of the clinician-administered PTSD scale-diagnostic version. Journal of Tr aum ati c S tre ss , 18, 161-164. doi:10.1002/jts.20013 Resick, P. A., & Schnicke, M. K. (1992). Cognitive processing therapy for sexual assault victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psy- chology, 60, 748-756. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.60.5.748 Terr, L. C. (1991). Childhood traumas: An outline and overview. American Journal of Psychiatry, 148, 10-20. Van der Kolk, B. A., & Fisler, R. (1995). Dissociation and the frag- mentary nature of traumatic memories: Overview and exploratory study. Journal of Traumatic St re s s, 8, 505-525. doi:10.1002/jts.2490080402 Weathers, F. W., Litz, B. T., Herman, D. S., Huska, J. A., & Keane, T. M. (1992). The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, validity, and di- agnostic utility. San Antonio, Texas: Paper Presented at the 9th An- nual Meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Stud- ies,. Weathers, F. W., Ruscio, A. M., & Keane, T. M. (1999). Psychometric properties of nine scoring rules for the clinician-administered post- traumatic stress disorder scale. Psychological Assessment, 11, 124- 133. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.11.2.124 Weiss, D. S., & Marmar, C. R. (1997). The Impact of Event Scale-Revised. In J. P. Wilson and T. M. Keane (Eds.), Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD (pp. 399-411). New York: The Guilford Press. Williams, J. M. G., Mathews, A., & MacLeod, C. (1996). The emo- tional stroop task and psychopathology. Psychological Bulletin, 120, 3-24. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.120.1.3

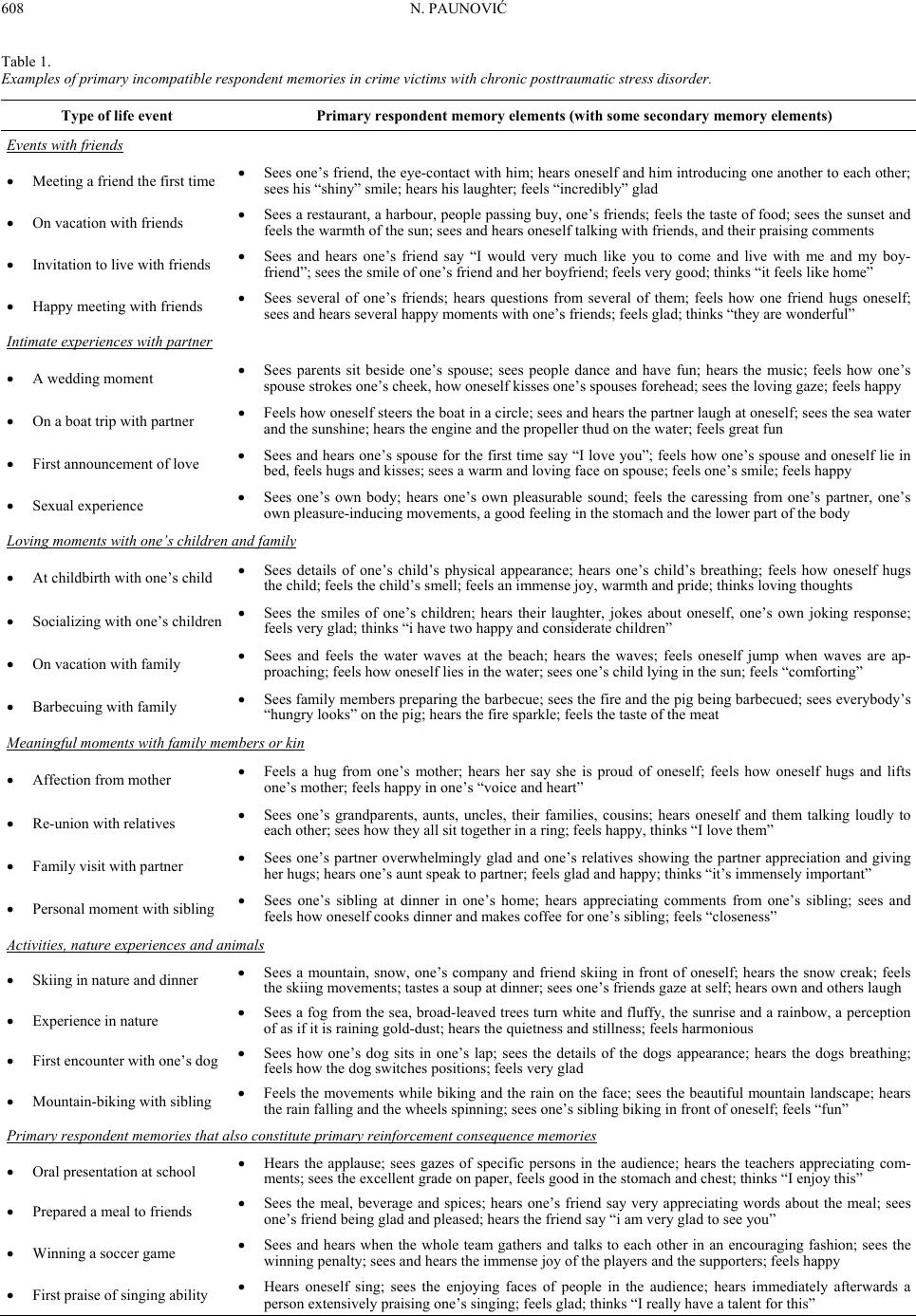

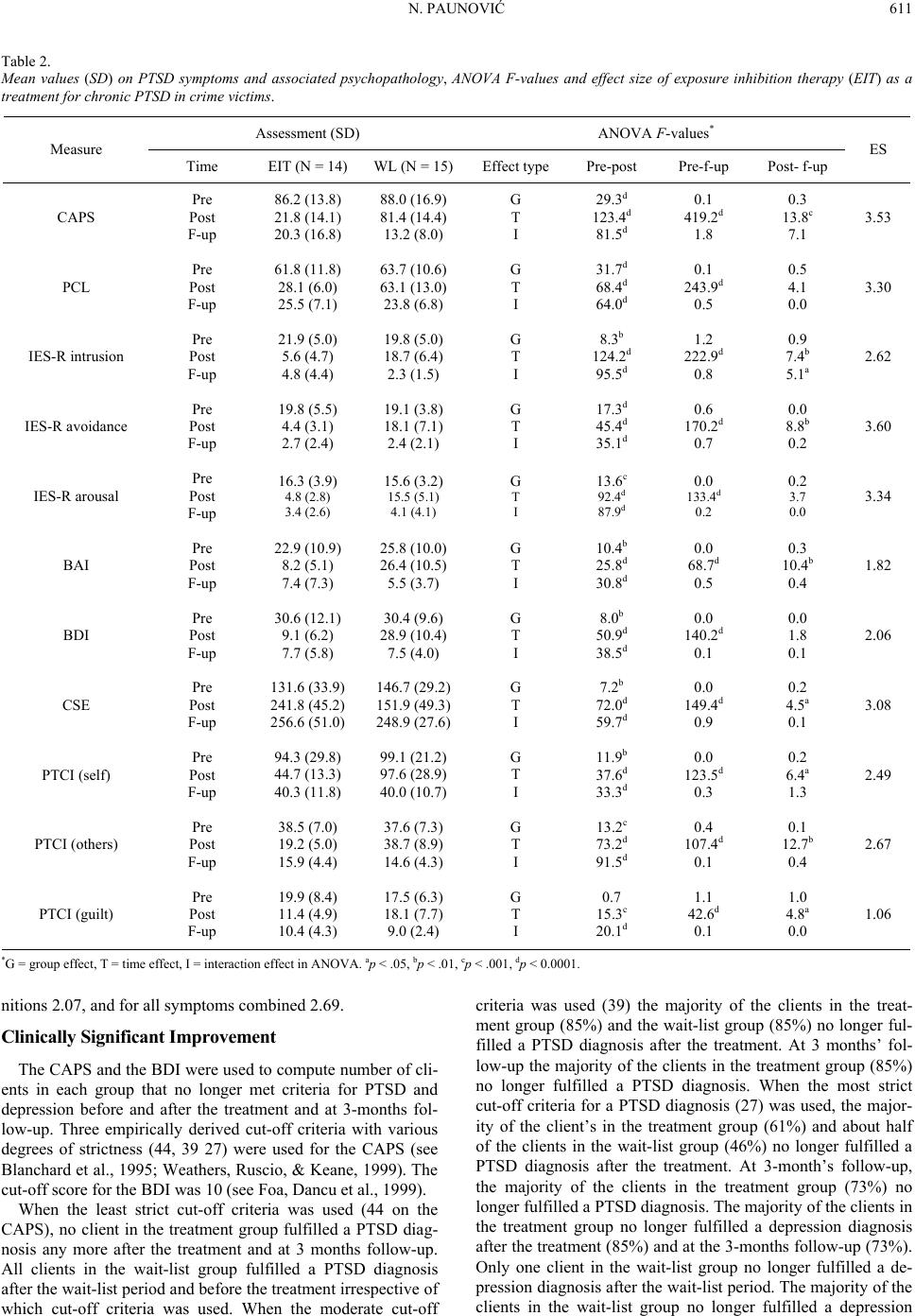

|