Psychology 2011. Vol.2, No.6, 560-567 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. DOI:10.4236/psych.2011.26086 The Processing of Dui-construction in Chinese* Yong Zhai Faculty of Humanities, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan. Email: zhaiyong@kyudai.jp Received May 23rd, 2011; revised June 28th, 2011; accepted August 7th, 2011. In the presen t study, I examined the Dui-construction fro m a psycholinguistic perspective. Two experiments on the processing of Dui-constructions h ave been carried out to reexamine the findings of previous ex periments on empty subjects in English and Japanese. There are two advantages of using the Chinese Dui-construction over English and Japanese. Firstly, Chinese is similar to English in tha t the verb is loca ted before the e mpty subject of an infinitival clause. It is therefore possible to verify whether the verb control information is delayed or not in this case. Secondly, Chinese is similar to Japanes e in that they both allow scrambl ing of arguments. As such, I can e xamine whether th e recency hypo thes is applies to Chines e or not. The resul ts indicated that 1) The control information of the verb is ac- cessed immediately; 2) The recency hypothesis is not supported in the processing of Dui-constructions. In other words, there exists a language-specific processing system independent of the general recency strategy. Keywords: Dui-construction, Recency Hypothesis, Control Information, Chinese Introduction A human parser processes a string of linguistic elements that are continuously given along the temporal sequence, and un- derstands the information transmitted by the given string. The parser identifies each component, establishes the relationship between components, and decides the meaning of the entire string. Various researches have been conducted to shed light on the process of the human parser (cf. Sakamoto 1998, Inoue & Fodor 1995, Aoshima et al. 2004). In the psycholinguistic lit- erature, the question of what types of information guide the initial parsing decision has been the focus. One of the factors is the effect of lexical information (Ford et al. 1982, MacDonald et al. 1994, Trueswell & Tanenhaus 1994, Miyamoto 2002). A lot of researches support the immediate use of such lexical in- formation (Inoue & Fodor 1995, Kamide & Mitchell 1999, Miyamoto 2002, Aoshima et al. 2004). There is one type of lexical information that is called ‘control information’, which determines how a particular verb influ- ences the interpretation of the subject of infinitival (and gerun- dive) complements. Consider the following examples adapted from Chomsky (1981). (1) a. Johni promised Bill [PROi to feed himself]. b. *Maryi promised Bill [PROi to feed himself]. (2) a. John persuaded Billi [PROi to feed himself]. b. *John persuaded Maryi [PROi to feed him s e lf]. In (1a) and (2a), the subject of the verb promise is assumed to be the understood subject of the infinitival clause, while the object of the verb persuade is considered to be the understood subject of the infinitival clause. At the subject position of the infinitival clause, Chomsky (1981) posits the empty category PRO, which is an abstract syntactic element with no phonetic content. PRO must establish a relationship with an antecedent in order to acquire its meaning. This coreference is determined by a relationship called ‘control’. When PRO appears in an infinitival complement clause, one of the arguments in the ma- trix clause must be understood as its antecedent (controller). Whether the controller is the subject or the object of the matrix clause depends on the intrinsic lexical properties of that verb. The ungrammatical versions (1b) and (2b) show clearly that promise is a subject control verb and persuade is an object control verb. The study of PRO is interesting for various reasons. Firstly, it lacks phonological realization, so that it escapes the physical perception. Secondly, it does not involve a moved element (NP- trace or wh-trace), so readers have no warning of the empty element downstream in the sentence. Finally, PRO, as an ana- phoric element, needs to be linked to an antecedent. These spe- cial features of PRO provide an attractive structure to test pre- dictions made by different syntactic processing models. None- theless, the empirical evidence on how readers resolve PRO on-line is far from conclusive (Betancort et al. 2005). Currently, related experiments have only been performed on a limited number of languages, such as English and Japanese, and the experimental methods and data are also inadequate. There is therefore room for more in-depth research. The findings of previous experiments on control structures in English differ from those of Japanese. The present study is concerned with the reexamination of the different results in English and Japanese by using the Dui-construction in Chinese. Dui-Construction in Chinese In Chinese linguistics, Dui-construction seems to be rela- tively disregarded, though the other prepositional constructions, such as ba-construction and bei-construction are widely dis- cussed. If we take a closer look, however, we will find that the Dui-construction actually has an interesting structure. Dui-con- struction is similar to the ba-construction and bei-construction in that the noun can be put ahead of the verb by using the words dui, ba, and bei. In addition, Dui-construction can also be put at the beginning of a sentence, whereas this is not possible with the ba- or bei-construction, as shown in the following exam- ples. (3) a. Weiyuanhui diaocha zhege wenti. NP1 V NP2 committee investigate this problem ‘The committee investigates thi s p ro bl em.’ (adapted from Wang 1998) *This work has received support from Japanese Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research C 17520269. b. Weiyuanhui dui zhege wenti  Y. ZHAI 561 committee PREP this problem zhengzai diaocha. PROGRES investigate ‘The committee is investigating this problem.’ (adapted from Wang 1998) Employing a speeded comprehension task, Frazier, Clifton and Randall (1983) examined English control structures to de- termine the strategy used by the parser to identify the antece- dent of the subordinate empty subject. Readers are provided with a word-by-word sentence presentation, and they need to make a sentence-final “got it” or “missed it” decision. The ex- perimental sentences such as (7) to (10) are manipulated ac- cording to the type of main verb (subject vs. object control) and the ambiguity of the sentences with respect to the verb control information (ambiguous control vs. unambiguous control). c. Dui zhege wenti weiyuanhui PREP this problem committee zhengzai diaocha. PROGRES investigate ‘To this problem, the committee is investigating.’ (4) a. Wo chi pingguo. NP1 V NP2 I eat apple ‘I eat apple.’ b. Wo ba pingguo chi le. I v apple eat PAST ‘I ate this apple.’ c. *Ba pingguo wo chi le. (5) a. Ta da wo. NP1 V NP2 he hit me ‘He hits me.’ b. Wo bei ta da le. I v him hit PAST ‘I was hit by him.’ c. *Bei ta wo da le. In (3a), (4a), and (5a), the structure of the sentences is [NP1 + V + NP2]. It is well known that Chinese is an SVO language. However, it also allows an SOV order by using words such as dui, ba, or bei (Okouchi 1992; Wang 1998). In (3b),(4b), (5b), using the words dui, ba, or bei, the structure of the sentences becomes [NP + NP +V]. In contrast, (3c) is grammatical, while (4c) and (5c) are ungrammatical. That is to say, the marker dui in the Dui-construction can be placed at the beginning of the sentence, but not so for the ba and bei markers in the ba- and bei-constructions. In previous studies, dui, ba, and bei have been treated as prepositions. From the difference highlighted above, we think that dui is a preposition, while ba and bei should be light verbs. In the following, we will focus on dui only. From (3b), the preposition dui is inserted to assign case to the NP2 that is moved to a preverbal position. The structure of (3b) is shown in (6) (cf. Wang 1998). As discussed above, Dui-construction has two characteristics. First of all, it allows the [NP1 NP2 V] structure. Secondly, the marker dui can be placed at the beginning of the Dui-construc- tion. These two points are very attractive, and they have not been studied at all in the psycholinguistics literature. In the following sections, we will investigate Dui-construction from a psycholinguistic perspective. (6) TP NP T’ PP T’ P’ Adv T’ T VP P NP j V NPj Weiyuanhui dui zhegewenti zhengzai INFL diaocha Processing of Empty Subject in English (7) Recent filler (subject control), unambiguous Everyone liked the woman who1 the little child2 started [PRO2 to sing those stupid French songs for trace1 last Christmas]. (8) Distant filler (object control), unambiguous Everyone liked the woman who1 the little child forced trace1 [PRO1 to sing those stupid French songs last Christmas]. (9) Recent filler (subject control), ambiguous Everyone liked the woman who1 the little child2 begged [PRO2 to sing those stupid French songs for trace1 last Christmas]. (10) Distant filler (object control), ambiguous Everyone liked the woman who1 the little child begged trace1 [PRO1 to sing those stupid French songs last Christmas]. The reaction times (RTs) were faster for (7) and (9) than for (8) and (10). In the recent filler unambiguous sentences (7), the verb start, a subject control verb, indicates that its subject the little child is the controller of PRO. Notice that among the two fillers, the woman and the little child, the latter is closer to the empty subject PRO. Hence, the actual filler is also the more recent filler. In the distant filler unambiguous sentences (8), the verb force, an object control verb, assigns its object the woman as the controller of PRO. Here, the correct filler is more distant among the two fillers. Frazier et al. hypothesize that recency is a factor for identifying the antecedent, so that a more recent filler is preferred over a more distant one. Hence, the sentences in which the recent filler is also the actual filler will produce faster RTs in a “got it” comprehension task than the sentences in which the recent filler is not the actual filler. Frazier et al. explain these findings with the application of the Most Recent Filler Strategy (MRFS), which is stated as follows (p. 196): (11) Most Recent Filler Strategy: During language comprehen- sion a detected gap is initially and quickly taken to be co-indexed with the most recent potential filler. Since the same result is found in both the ambiguous and un- ambiguous sentences, Frazier et al. imply that the MRFS ap- plies only when the parser does not have reliable information about the correct filler for PRO. In the absence of lexical verb control information, the MRFS is claimed to apply. This re- cency strategy assigns the nearest potential filler to PRO. This initial choice by the parser is later checked by the control in- formation. It is this error-correcting procedure that causes the longer processing time in the distant filler sentences. Further- more, if trace is a possible filler, it will not produce any RT difference between (7) and (8), because trace is the nearest filler for PRO in (8). Hence, Frazier et al. assume that the parser does not recognize trace as a possible filler for PRO. In other words, the parser does not recognize a gap as a filler for  Y. ZHAI 562 another gap1. Processing of Empty Subject in Japanese Sakamoto (1995, 1996, 2002), Oda et al. (1997), and Ninose et al. (1998) conducted a series of experiments on empty sub- jects in Japanese. Japa nese offers two advantages over English. Firstly, verb control information is not yet available at the PRO position, since Japanese is a verb-final language. So, it is not necessary to posit an untested hypothesis that the control in- formation of a verb is not used immediately. Secondly, Japa- nese allows scrambling of arguments, so that either noun (sub- ject and object) may be put in a recent filler or distant filler position. This means that the recency hypothesis (MRFS) can be tested. Sakamoto (1995) examined subject control (12a) and object control (12b) sentences in order to identify which of them was preferred. The experimental sentences were ‘read-out sen- tences’ that had normal sentential contours. Participants were given a ‘retrieval task’ in which they were instructed to listen to each sentence and respond by naming the person who was go- ing to be in Tokyo. (12) a. Subject control (SO order) Tosio1-ga kinoo Junko2-ni [PRO1 Tosio-NOM yesterday Junko-DAT Tookyoo iki]-o tegami-de hakuzyoosita. Tokyo going-ACC letter-by confessed ‘Yesterday, Tosio confessed to Junko by a letter that he would go to Tokyo.’ b. Object control (SO order) Tosio1-ga kinoo Junko2-ni [PRO 2 Tosio-NOM yesterday Junko-DAT Tookyoo iki]-o tegami-de meireisita. Tokyo going-ACC letter-by ordered ‘Yesterday, Tosio ordered Junko by a letter that she would go to Tokyo. c. Subject control (OS order) Junko2-ni kinoo Tosio1-ga trace2 Junko-DAT yesterday Tosio-NOM [PRO 1 Tookyoo iki]-o tegami-de hakuzyoosita. Tokyo going-ACC letter-by confessed d. Object control (OS order) Junko2-ni kinoo Tosio1-ga trace2 Junko-DAT yesterday Tosio-NOM [PRO 2 Tookyoo iki]-o tegami-de meireisita. Tokyo going-ACC letter-by ordered The findings show that the object control sentences have sig- nificantly faster RTs than the subject control sentences. The objects in this experiment were also the more recent fillers. Thus, the results of this experiment are compatible with the hypothesis that the MRFS applies to Ja panese control structures. However, another possible explanation is that the parser prefers to assign control to an object initially. A second experiment was designed to compare these two hypotheses. In Experiment 2, the order of the subject and object NPs was switched ((12c) and (12d)), so that in the object control sen- tences the object is the distant filler, and in the subject control sentences the subject is the recent filler. The result was the same as Experiment 1: the RTs of the object control sentences were significantly faster than the subject control sentences. The findings of Experiments 1 and 2 indicate that either 1) the MRFS affects the parsing process, if the parser recognizes the empty category as a possible filler for an another empty cate- gory (this is called ‘Empty Filler Also (EFA)’ hypothesis); or 2) the grammatical object is preferred as the candidate for the empty subject. Using the same material as Sakamoto (1995), Oda et al. (1997) and Ninose et al. (1998) found that the participants tend to prefer the main clause subject as a possible antecedent for the empty subject. That is, in contrary to Sakamoto (1995), which observed the ‘object preference’ effect (the grammatical object is preferred as the candidate for the empty subject), Oda et al. (1997), Ninose et al. (1998) reported the ‘subject prefer- ence’ effect (the grammatical subject is preferred as the candi- date for the empty subject). However, note that the task in Sa- kamoto’s experiments was a ‘retrieval task’, whereby the par- ticipants were required to reproduce the correct antecedent, by naming one of the two possible antecedents. On the other hand, in the experiments of Oda et al. and Ninose et al., the partici- pants were given a ‘recognition task’, where they were required to answer whether the given antecedent would really go to To- kyo or not, by pressing the “Yes” or “No” key as quickly as possible. Sakamoto (2002) tries to resolve the seemingly con- tradictory results by positing two distinct levels of sentence processing. One level involves a rather automatic and shallow mode of processing, in which the parser uses Case information to perform the recognition task. The other level involves a rather conscious and deep mode of processing, in which the parser relies on Theta-role information to perform the retrieval task. Problems of Previous Studies The claim by Frazier et al. (1983) consists of three assump- tions: 1) verb control information is delayed, 2) during this delay the MRFS applies, and 3) an empty category (trace) is not recognized as a possible filler in applying the MRFS (i.e., Lexical Filler Only (LFO) hypothesis). The schematic repre- sentation of (8) is shown in (13). (13) Frazier et al. (1983): English Movement [filler2]-[filler1]-[verb]-[trace]-[PRO] MRF+LFO The results of Sakamoto’s (1995) Experiment 1, in which experimental sentences take the “Subject-Object” order, show that object control sentences are easier to process than subject control sentences. The object NPs in this experiment are also the most recent fillers. Thus, the results of this experiment are compatible with the hypothesis that the MRFS applies to Japa- nese control structures. However, the results of Experiment 2, with the “Object-Subject” order, reveal that it is not the most recent lexical filler, but the object NP, that is preferred as a controller, even when it is more distant than another lexical filler. This is not compatible with the MRFS for Japanese unless the parser recognizes empty categories as possible fillers (i.e., Empty Filler Also (EFA) hypothesis). The schematic rep- resentation of (12c, d) is as illustrated in (14). (14) Sakamoto (1995), Oda et al. (1997) 1This is termed the “Lexical Filler Only” hypothesis in Sakamoto (1995, 1996 . and Ninose et al. (1998): Japanese  Y. ZHAI 563 Movement [filler2]-[filler1]-[trace]-[PRO]-[verb] MRF+EFA Subject Preference Object Preference Note that for English, application of the MRFS is dependent on the condition that delays access to the verb control informa- tion. For Japanese, there is no way to examine the delay of verb control information since the main verb is located at the end of a sentence. That is, control information is not delayed but sim- ply does not exist. In the present study, we will use the follow- ing schematic representation in the Dui-construction of Chinese to test the results of English and Japanese. (15) Dui-construction in Chinese Movement [filler2]-[filler1]-[trace]-[verb]-[PRO] MRF + EFA MRF + LFO Subject Preference Object Preference There are two advantages of using the Dui-construction over English and Japanese. Firstly, in (13) and (15), Chinese is similar to English in that the [verb] is located before [PRO]. It is therefore possible to verify whether the verb control informa- tion is delayed or not in this case. Delay of verb control infor- mation cannot be tested in Japanese, since the verb does not appear before the parser encounters PRO. Secondly, (14) and (15) indicate that Chinese is similar to Japanese in that they both allow scrambling of arguments. As such, we can examine whether the MRFS applies to Chinese or not. Moreover, the reading time of each word was not measured in the previous studies on English and Japanese. It is therefore not clear how the parser processes each word, which makes it difficult to verify whether verb control information is available immediately. The reading time of each word is observed in the present experi m e n t s. Experiments This section discusses two experiments that were conducted in order to find clues for answering the questions raised in Section 5. It has been argued in previous studies that the MRFS is ap- plied during empty subject processing in English, and that con- trol information is used after the MRFS is applied. On the other hand, there is an argument that the MRFS is not applied in Japanese. The results of empty subject sentence processing in English and Japanese are different, and a unanimous opinion has not been presented regarding the processing of the empty subject sentences stated above. Therefore, this study aims to clarify the following two points by using Dui-constructions in Chinese such as (15). 1) Is verb control information available immediately or delayed? 2) Is the MRFS applicable to the Dui-construction in Chi- nese? a) If the MRFS is applied to Chinese, is it accomplished by LFO (Lexical Filler Only) or EFA (Empty Filler Also)? b) If the MRFS is not applicable to Chinese, which of the two antecedents (subject or object) is preferred? Experiment 1 Materials Consider the following examples taken from the list of sen- tences tested in this experimen t. (16) a Subject control (SO order) p1 p2 p3 p4 Shangzhou Xiaodong1 zai xinzhong dui nüyou2 last week Xiaodong in letter to girlfriend p5 p6 p7 p8 zhencheng tanbai shuo [<PRO1>qu Beijing.] seriously confess that go Beijing “Last week Xiaodong confessed to (his) girlfriend seriously in (his/a) letter that he would go to Beijing.” b. Object control (SO order) Shangzhou Xiaodong1 zai xinzhong dui nüyou2 last week Xiaodong in letter to girlfriend zhencheng quangao shuo [<PRO2>qu Beijing.] seriously advise that go Beijing “Last week Xiaodong advised (his) girlfriend to go to Beijing seriously in (his/a) letter.” c. Subject control (OS order) Dui nüyou2 shangzhou Xiaodong1 zai xinzhong trace2 to girlfriend last week Xiaodong in letter zhencheng tanbai shuo [<PRO1>qu Beijing.] seriously confess that go Beijing d. Object control (OS order) Dui nüyou2 shangzhou Xiaodong1 zai xinzhong trace2 to girlfriend last week Xiaodong in letter zhencheng quangao shuo [<PRO2>qu Beijing.] seriously advise that go Beijing The main clause verb “tanbai (confess)” in (16a, c) is a subject control verb, whereas the main clause verb “quangao (advise)” in (16b, d) is an object control verb2. (16a, b) take the ‘subject – object’ word order, and (16c, d) the ‘object – subject’ word order. Thus, the experiment design is 2 (verb types) × 2 (word orders). The difference between the subject and object control verbs in p6 was controlled in terms of the number of characters, the number of syllables, and the word frequency. All the subject and object control verbs have two characters and two syllables. The difference in judged frequency between the subject control verbs (M = 3.96) and object control verbs (M = 3.91) is not significant (t1(29) = 1.217, p = .233, t2(13) = 1.176, p = .261). Therefore, the two types of control verbs have almost the same lexical characteristic, and it is possible to make a direct com- parison between them. Predictions There are two verbs in (16): one is the main clause verb (p6), the other is the complement clause verb (p7). If the control information of the verb (p6) is not used immediately, then the RTs of p6 should not be different among the four types of sen- tences. Thus, identification of the antecedent should be per- formed at the point p7, and a difference in the RTs of “qu Bei- jing” should be observed among the different types of sentences. 2It may be poss ible to claim that ‘s huo’ is also a verb. However , we follow Simpson and Wu (2002), which claim that “Frequently this occurs when a language has serial verb constructions which allow for a sequence of two verbs of communication to become reanalyzed as a sequence of verb + complementizer (p. 75)”. This is illustrated schematically i n (1): (1) Verb1 Verb2 → Verb1 Complementizer  Y. ZHAI 564 If the MRFS is applicable to Chinese, then “dui nüyou (p4 to girlfriend)” in (16b) is the nearest lexical filler, and the RT of p7 in (16b) will be shorter than that in (16a). In the scrambled sentences (16c) and (16d), the difference in the RTs of p7 depends on whether the trace is the filler or not. If the trace is taken as the filler (Empty Filler Also (EFA) hy- pothesis), the RT of p7 in (16d) will be shorter than that in (16c). On the other hand, if the trace is not taken as the filler (Lexical Filler Only (LFO) hypothesis), then “Xiaodong (p3)” in (16c) is the nearest filler, and the RT of p7 will be shorter than that in (16d). If the recency strategy (MRFS) does not work in these con- structions, and the subject is preferred by the parser, then the RTs of p7 in subject control sentences ((16a) and (16c)) will be shorter than those in the object control sentences ((16b) and (16d)). If the object is preferred by the parser, the RTs of p7 in object control sentences ((16b) and (16d)) will be shorter than those in the subject control sentences ((16a) and (16c)). The schematic representation of the prediction is as shown in (17). (17) Table 1. Predicted relation of reading t i m e s of p7 in Experiment 1 (Assumption: Control information of the verb (p6) is not used imm e d i a t e l y). 1) MRF + LFO (16a) > (16b) (16c ) < (16d) 2) MRF + EFA (16a) > (16b) (16c) > (16d) 3) Subject Preferenc e (16a, c) < (16b, d) 4) Object Pref erence (16a, c) > (16b , d) Methods and R e s ul t s Participants Twenty participants (9 males and 11 females) participated in this experiment. All participants are native speakers of Chinese with normal or corrected-to-normal vision, who are students at the Kyushu University in Japan. The average age is 28 years old. They were paid 500 yen for half an hour. Procedures The experiment was conducted with SuperLab 2.0 running on a CX/835LS dynabook notebook computer. Each sentence is presented word-by-word in Chinese script. Each phrase3 is dis- played using a moving window. Presentation of a sentence is initiated when the participant first presses the ‘Q’ key on a standard computer keyboard labeled ‘read’. A ‘’ first appears ★ in the script. It is a symbol that tells the participants that the experimental sentence will begin at this position. Pressing the key following the final display (period) displays the question: “Will this person go to Beijing?”. Participants are instructed to respond using either the YES or NO key. Thus, this is not a retrieval but recognition task. The time between the onset of presentation of any phrase and the key operation for initiating the next phrase is recorded by the computer’s internal clock and deemed as the reading time. Results Analysis of Variance was performed on the data of the RTs in each phrase to determine their statistical significance. Here, we report the results of the main clause verb p6 and the com- plement sentence verb p7. The RTs of p6 (verb + shuo (that)) for subject control sen- tences were shorter than those for the object control sentences, and the difference was significant in both the participant analy- sis and item analysis (F1(1.19) = 6.43, p < .05, F2(1.27) = 6.10, p < .05). The difference between SO-order sentences and OS-order sentences was not significant in both the participant analysis and item analysis (F1(1.19) = 1.59, p = .22, F2 < 1). There was no interaction (F1 < 1, F2 < 1). The RTs of p7 (go Beijing) for subject control sentences were shorter than those for the object control sentences, and the difference was significant only in the participant analysis (F1(1.19) = 4.66, p < .05, F2(1.27) = 1.01, p = 0.33). The dif- ference between SO-order sentences and OS-order sentences was significant in both the participant analysis and item analy- sis (F1(1.19) = 4.68, p < .05, F2(1.27) = 5.27, p < .05). In addi- tion, there was a marginal effect of interaction (F1(1.19) = 3.60, p = .07, F2(1.27) = 3.86, p = .06). The main effect of word or- der in object control sentences (F1(1.19) = 7.31, p < .05, F2(1.27) = 4.06, p < .05), and the main effect of sentence type in the SO word order (F1 (1.19) = 8.13, p < .01, F2 (1.27) = 8.91, p < .005) were observed in both the participant analysis and item analysis. However, the main effect of word order in sub- ject control sentences (F1< 1, F2 < 1), and the main effect of sentence type in the OS word order (F1 < 1, F2 < 1) were not observed. Discussion The RTs of p7 in (16a) is shorter than that in (16b) as shown in Figure 1 ((16a) < (16b)). As stated above, the main effect of sentence type in the SO word order was significant (F1(1.19) = 8.13, p < .01, F2(1.27) = 8.91, p < .005). This result disagrees with 1) and 2) in (17), which predict that the MRFS applies to Chinese. Since this strategy is not tenable, it is legitimate to claim that there is a language processing system independent of the MRFS (i.e., the nearest filler fills up the gap). Moreover, the RTs of p6 (verb + shuo (that)) for subject control sentences are significantly shorter than those for the object control sentences (F1(1.19) = 6.43, p < .05, F2(1.27) = 6.10, p < .05). The structure of (16a) is like (18a), and the struc- ture of (16b) is like (18b). The verb “tanbai (confess)” is a sub- ject control verb, and it does not allow an object before the infinitive clause. On the other hand, the verb “quangao (ad- vise)” is an object control verb, and it requires a direct object before an infinitive clause. It is the same in (16c) and (16d) that “tanbai (confess)” does not allow an object before the infinitive clause, “quangao (advise)” requires a direct object before an infinitive clause. It is thought that the difference between con- structions such as (18a) and (18b) causes the difference in the 3Here, because there are cases such as “word”, “preposition + noun”, “verb + complementizer”, we refer to them as “phrase” collectively. Figure 1. Reading times of each phrase in Ex periment 1.  Y. ZHAI 565 RTs of P6. In short, constructing a transitive structure might be more costly for an object control sentence than a subject control sentence. Note that this explanation becomes possible based on the condition that the control information of the verb (p6) is used immediately. (18) a. Simple Structure of (16a) b. Simple Structure of (16b) Moreover, the unique character of ‘subject’ in Chinese (i.e., there is no concept of so-called ‘subject’ in Chinese. Instead, it is suitable to be called ‘focus’) may be another reason for the difference in the RTs of p6. The above result may indicate that the parser expects the focus of the following clause to be the subject of the main clause before the verb p6 appears. This prediction is correct in the case of a subject control verb, but not the object control verb. This explains why the RTs of p6 in subject control sentences are shorter than those in object control sentences. Similarly , this explanation is valid based on the con- dition that the control information of the verb (p6) is used im- mediately. The RTs of p7 in the subject control sentences ((16b,c) are shorter than those in the object control sentences (16b,d) ((16a,c) < (16b,d)), although the difference is significant only in the participant analysis (F1(1.19) = 4.66, p < .05, F2(1.27) = 1.01, p = 0.33). This is in accordance with the prediction of the subject preference hypothesis in 3) of (17). These results there- fore suggest that ‘subject preference’ applies to the Dui-cons- truction. However, note that ‘subject preference’ is applicable only when the information of the verb (p6) is not used immedi- ately. From the results of Experiment 1, we have clarified that the MRFS does not apply to the Dui-construction. However, it is still not clear whether or not the verb control information is used immediately. In experimental sentences such as (16), note that the verb of the main clause (p6) and the verb of the complement clause (p7) are adjacent. Thus, it is difficult to judge whether the gap filling process begins at p6 or p7. Gap-filling may start immediately after the main verb appears, or it may start some time later. To resolve the adjacency issue, we conducted Experiment 2, whereby three adverbs a re placed between the verb of the main clause and the verb of the complement clause. These adverbs make it possible to observe the starting point of the gap-filling process. Experiment 2 In Experiment 2, we try to verify whether control informa- tion of the main clause verb is used immediately. Materials In Experiment 2, three adverbs are placed between the verbs of the main clause and the complement clause. Consider the following examples taken from the list of sentences tested in this experiment. (2) a. Subject control (SO order) p1 p2 p3 p4 Shangzhou Xiaodong1 zai xinzhong dui Xiaohong2 last week Xiaodong in letter to Xiaohong p5 p6 p7 p8 zhencheng tanbai shuo [biye hou cong Changchun seriously confess that graduate after from Changchun p9 p10 zhijie 〈PRO1〉qu Beijing4] immediately go Beijing “Last week Xiaodong confessed to Xiaohong seriously in a letter that he would go to Beijing from Changchun immediately after graduating.” b. Object control (SO order) Shangzhou Xiaodong1 zaixinzhong duiXiaohong2 last week Xiaodong in letter to Xiaohong zhencheng quangao shuo [biye hou cong Changchun seriously advise that graduate after from Changchun zhijie 〈PRO2〉qu Beijing.] immediately go Beijing “Last week Xiaodong (seriously) advised Xiaohong to go to Beijing from Changchun immediately after gradu- ating in a letter.” c. Subject control (OS order) DuiXiaohong2 shangzhou Xiaodong1 zaixinzhong to Xiaohong last week Xiaodong in letter trace2 zhencheng tanbai shuo [biye hou seriously confess that graduate after cong Changchun zhijie 〈PRO1〉qu Beijing.] from Changchun immediately go Beijing d. Object control (OS order) Dui Xiaohong2 shangzhou Xiaodong1 zaixinzhong to Xiaohong last week Xiaodong in letter trace2 zhencheng quangao shuo [biye hou seriously advise that graduate after cong Changchun zhijie 〈PRO2〉qu Beijing.] from Changchun immediately go Beijing Predictions Table 2 shows the predictions of the RTs of p10, if the main clause verb (p6) is not used immediately. (20) Table 2. Predicted relation of reading times of p10 in Experiment 2 (Assump- tion: Control informat io n o f th e v er b (p6) is not used immedia tely). 1) MRF + LFO (19a) > (19b) (19c ) < (19d) 2) MRF + EFA (19a) > (19b) (19c) > (19d) 3) Subject Preferenc e (19a, c) < (19b , d) 4) Object Pref erence (19a, c) > (19b , d) If the control information of the verb (p6) is not used imme- diately, and the MRFS is applicable to Chinese, then “dui Xiaohong (p4 to Xiaohong)” in (19b) is the nearest lexical filler, and the RTs of p10 in (19b) will be shorter than (19a). If the control information of the verb (p6) is not used imme- 4It was pointed out that there is a possibility that the parser uses some special s trategies for p rocessing if all th e experimental sen tences end with “qu Beijing” (Edson Miyamoto, personal communication).However, in Experiment 2, a significant difference in the RT of “qu Beijing (p10)” between each condition was not observed. Therefore, we claim that the empty subject has already been filled when the main clause verb is input. In other words, the result remains the same even if we change “qu Beijing” to another expression.  Y. ZHAI 566 diately, and ‘subject preference’ is applicable to Chinese, then the RTs of p10 in the subject control sentences ((19a) and (19c)) will be shorter than those in the object control sentences ((19b) and (19d)). If the object is preferred by the parser, the RTs of p10 in the object control sentences ((19b) and (19d)) will be shorter than the subject control sentences ((19a) and (19c)). If the results disagree with the predictions in (20), this leads to the possibility that the control information of the main clause verb (p6) is used immediately. Methods and R e s ul t s Participants Twenty-four participants (8 males and 16 females) different from those in Experiment 1 participated in this experiment. All participants are native speakers of Chinese with normal or cor- rected-to-normal vision, who are students at the Kyushu Uni- versity in Japan. The average age is 28 years old. They were paid 500 yen for forty minutes. Procedures Procedures are the same as those of Experiment 1. That is, we have used a self-paced moving window representation and a recognition task. Results Analysis of Variance was performed on the data of the RTs in each phrase to determine their statistical significance. Here, we report the results of the main clause verb p6 (verb + shuo (that)) and the complement sentence verb p10. The RTs of p6 for subject control sentences were shorter than those for the object control sentences, and the difference was significant in both the participant analysis and item analysis (F1 (1.23) = 5.43, p < .05, F2 (1.35) = 13.87, p < .001). The differ- ence between SO-order sentences and OS-order sentences was not significant in both the participant analysis and item analysis (F1 < 1, F2 < 1). There was no interaction (F1 (1.23) = 1.17, p =.29, F2 < 1). In p10 “qu Beijing”, neither the main effect of the word order (F1 < 1, F2 < 1), the main effect of the sentence type (F1 < 1, F2 < 1) nor interaction (F1 < 1, F2 < 1) was observed. Discussion As shown in Figure 2, no significant difference in the RTs of p10 was observed between each condition in this experiment. This result disagrees with the predictions in (20) that control information of the ma in clause verb is not used immedia tely, as discussed in predictions. The RTs of p6 is the same as Experiment 1, and is shorter for the subject control sentences than for the object control sen- tences. With regard to this finding, there are at least two inter- pretations as with the case of Experiment 1. Firstly, construct- ing a transitive structure might be more costly for an object control sentence than for a subject control sentence. Secondly, the special character of ‘subject’ in Chinese makes the RTs of subject control verbs shorter than object control verbs. These two interpretations both support the claim that control informa- tion of the main clause verb is used immediately. Since no significant difference in the RTs of p10 was ob- served, we consider that the empty subject has already been filled before the complement sentence verb (p10) appears. Thus, we suggest that the empty subject is filled by information from another verb (the main clause verb p6) that exists in the ex- perimental sentence. In short, control information of the main clause verb p6 is used immediately. Figure 2. Reading times of each phrase in Ex periment 2. Summary of Experiments 1 and 2 In Experiment 1, the mean RT of “qu Beijing (p7)” in the subject control sentences (SO order) was shorter than that in the object control sentences (SO order), and the difference was significant in both the participant analysis and item analysis. In Experiment 2, no significant difference in the RTs of “qu Bei- jing (p10)” between each condition was observed. These two experiments disagree with the claim that the MRFS applies to Chinese. There are two possible ways of interpreting the results of Experiment 1. 1) Control information of the main clause verb is used immediately; 2) ‘subject preference’ applies to the Dui-construction in Chinese when the information of the verb (p6) is not used immediately. In other words, it is not clear in Experiment 1 whether control information of the verb is used immediately. In the results of Experiment 2, no significant dif- ference in the RTs of p10 was observed. This clearly proves that the control information of the main clause verb is used immediately. Based on Experiments 1 and 2, we suggest that 1) the control information of the main clause verb is used immediately; 2) the MRFS does not apply to Chinese. Concluding Remarks In processing English empty subject sentences, Frazier et al. (1983) propose the MRFS. (21) (= (11)) Most Recent Filler Strategy: During language compre- hension a detected gap is initially and quickly taken to be co-indexed with the most recent potential filler. Application of the MRFS is dependent on two conditions, namely 1) LFO and 2) Verb Control Delay. 1) Lexical Filler Only: The parser does not recognize a gap as filler for another gap. 2) Verb Control Delay: Verb control information is not used immediately when the main clause verb appears. Experiments in Sakamoto (1995), Oda et al. (1997) and Ni- nose et al. (1998) on the processing of the control structures in Japanese have arrived at the following three findings. 1) The MRFS is not applicable to control structures in Japa- nese. 2) In the recognition task, participants tend to prefer the main clause subject as a possible antecedent for the empty sub- ject.  Y. ZHAI 567 3) In the retrieval task, participants tend to prefer the main clause object as a possible antecedent for the empty sub- ject. The findings of the present study regarding the processing of Dui-construction in Chinese are summarized as follows. 1) The MRFS is not applicable to control structures in Chi- nese. 2) Verb control information is used immediately when the verb appears. Since the MRFS is not applicable to the control structures in Japanese and Chinese, it is possible that the MRFS is a special strategy that is applied only to English. However, note that for English, application of the MRFS is dependent on the condition that delays access to the verb control information. If this condi- tion does not exist, the basis of the MRFS is lost. However, sentence processing is developed along the temporal sequence. That is, the information of each word is processed at a high speed without any delay. It is not natural to claim the delay in the verb control information from the viewpoint of a general processing system. Furthermore, we have also verified through our experiments that the control information of a verb is used immediately, hence indicating that there is a language process- ing system that is independent of the MRFS. From the above discussion, we therefore claim that 1) the control information of a verb is used immediately, and 2) there is a language-specific processing system that is independent of the general-purpose recency strategy. Acknowledgements This work has received support from the Center for the Study of Language Performance, Kyushu University. Especially, I wish to express my gratitude to my supervisor Professor Tsu- tomu Sakamoto. References Aoshima, Sachiko, Colin Phillips & Amy S. Weinberg (2004) Process- ing filler-gap dependencies in a head-final language. Journal of memory and language, 51, 23-54. doi:10.1016/j.jml.2004.03.001 Betancort, M., Enrique, M., & Carreiras, M. (2005) The empty PRO: Processing what cannot be seen. In: M. Carreiras and C. Clifton Jr. (Eds.) The on-line study of sentence comprehension: Eyetracking, ERPS and Beyond (pp. 95-118 ). New York, NY: Psychology Press. Chomsky, N. (1981) Lectures on Government and Binding. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Foris. Demestre, J., Meltzer, S., García, Albea, & A. Vigil (1999) Identifying the null subject: Evidence from event-related brain potential. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 28, 293-312. doi:10.1023/A:1023258215604 Ford, M., Bresnan, J., & Kaplan, R. (1982) A competence-based theory of syntactic closure. In J. Bresnan (Ed.), The mental representation of grammatical relations ( pp. 727-796). Cambrige, MA: MIT Press. Frazier, L., Clifton, C., & Randall, J. (1983). Filling gaps: Decision principles and structure in sentence comprehension. Cognition, 13, 187-222. doi:10.1016/0010-0277(83)90022-7 Hwang, J. L. (1998). A comparative study on the grammaticalization of saying verbs in Chinese. NACCL, 10, 585-597. Inoue, A., & Fodor, J. D. (1995) Information-paced parsing of Japanese. In: R. Mazuka and N. Nagai (Eds.), Japanese sentence processing, (pp. 9-63). Hillside, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Kamide, Y., & Mitchell, D. C. (1999) Incremental pre-head attachment in Japanese parsing. Lang uage and cognitive proc e ss e s , 1 4, 631-662. doi:10.1080/016909699386211 MacDonald, M. C., Pearlmutter, N. J., & Seidenberg, M. S. (1994) The lexical nature of syntactic ambiguity resolution. Psychological Re- view, 101, 676-703. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.101.4.676 Miyamoto, E. T. (2002) Case markers as clause boundary inducers in Japanese. Journal of ps yc h ol i n guistic research, 31, 307-347. doi:10.1023/A:1019540324040 Ninose, Y., Oda, J., Sakaki, Y., Sakamoto, T., & Gyoba, J. (1998) Ryooji-bunnri-choohoo niyoru kuushugo hantei purosesu-no bunseki (2): Gojun-No kooka (On the real-time processing of empty subjects in Japanese using a dichotic-listening method (2): The word order effect). Ninchi Kagaku (Cognitive Science), 5, 82- 88. Oda, J., Ninose, Y., Sakaki, Y., Gyoba, J., & Sakamoto, T. (1997) Ryooji-bunnri-choohoo niyoru kuushugo hantei purosesu-no bunseki (On the real-time processing of empty subjects in Japanese using a dichotic-listening method). Ninchi Kagaku (Cognitive Science), 4, 58-63. Okouchi, Y (1992) Nihonngo to tyuugokugo no taisyou kennkyuu ronnbunnsyuu (The collection of paper in contrast Japanese and Chinese). Kuroshio Press. Sakamoto, T. (1995) Koubunn kaiseki niokeru toumeisei-no kasetu: kuusyugo wo fukumu bunn-no syori-ni kannshite (Transparency hy- pothesis in parsing: On the processing of Empty Subjects in Japa- nese). Ninchi Kagaku (Cognitive Science), 2, 77-90. Sakamoto, T. (1996) Processing empty subjects in Japanese: Implica- tions for the transparency hypothesis. Fukuoka: Kyushu University Press. Sakamoto, T. (2002). Processing filler-gap constructions in Japanese: The case of empty subject sentence. Sentence Processing in East Asian languages, 189- 221. Sakamoto, T. & Walenski, M. (1998) The processing of empty subject in English and Japanese. Syntax and Semantics 31, Sentence Proc- essing: A Crosslinguistic Perspective. San Diego: Academic Press. 95-111. Simpson, A. and Z. Wu (2002). Ip-raising, tone sandhi and the creation of s-final particles: evidence for cyclic spell-out. Journal of East Asian Linguistics, 11, 67-99. doi:10.1023/A:1013710111615 Trueswell, J. C., & Tanenhaus, M. K. (1994) Toward a lexicalist framework of constraint-based ambiguity resolution. In C. Clifton, Jr., L. Frazier and K. Rayner (Eds), Perspectives on sentence proc- essing (pp. 155-179). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc. Wang, W. B. (1997) On the Dui-construction in Chinese. NACCL, 9, 298-314.

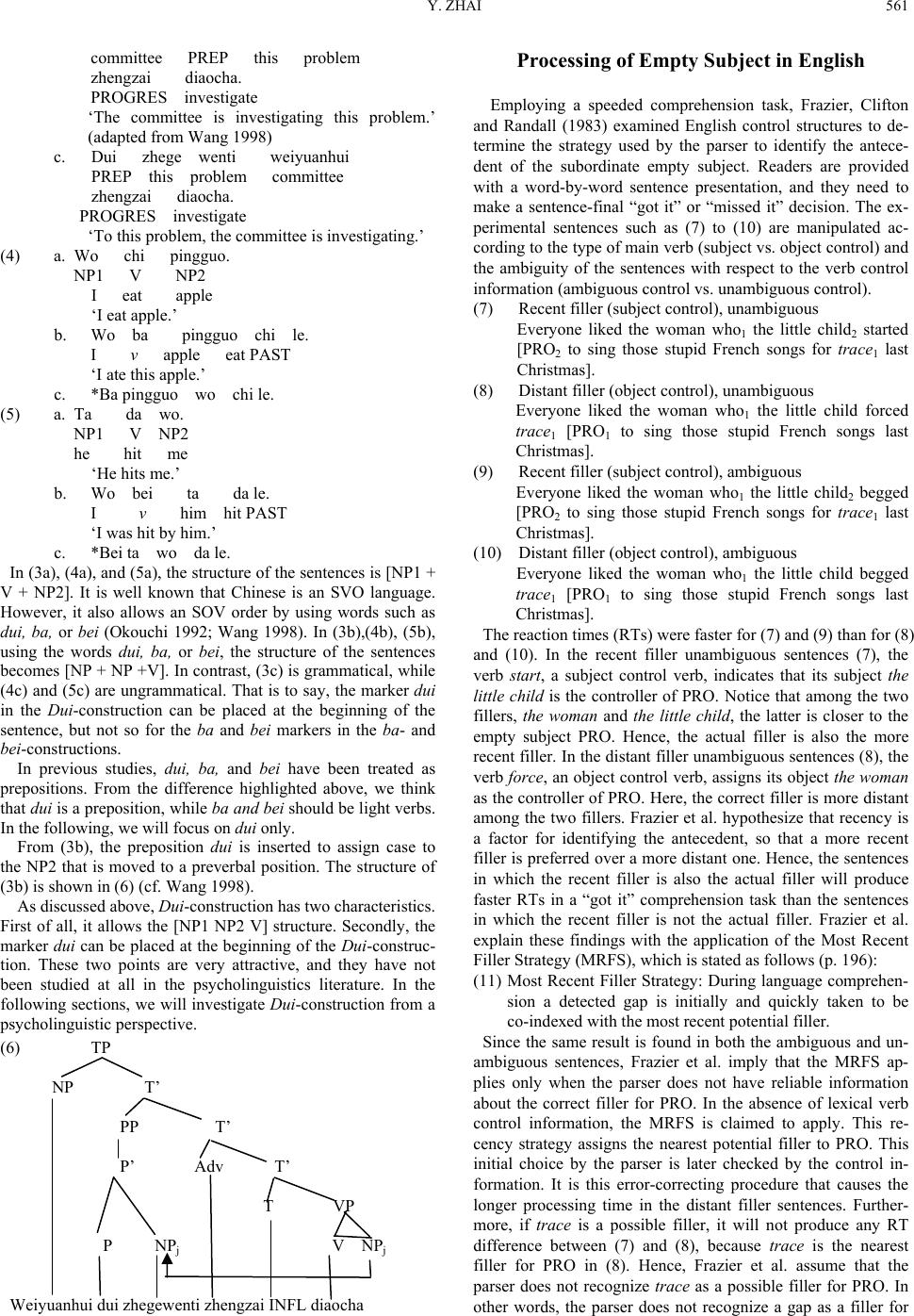

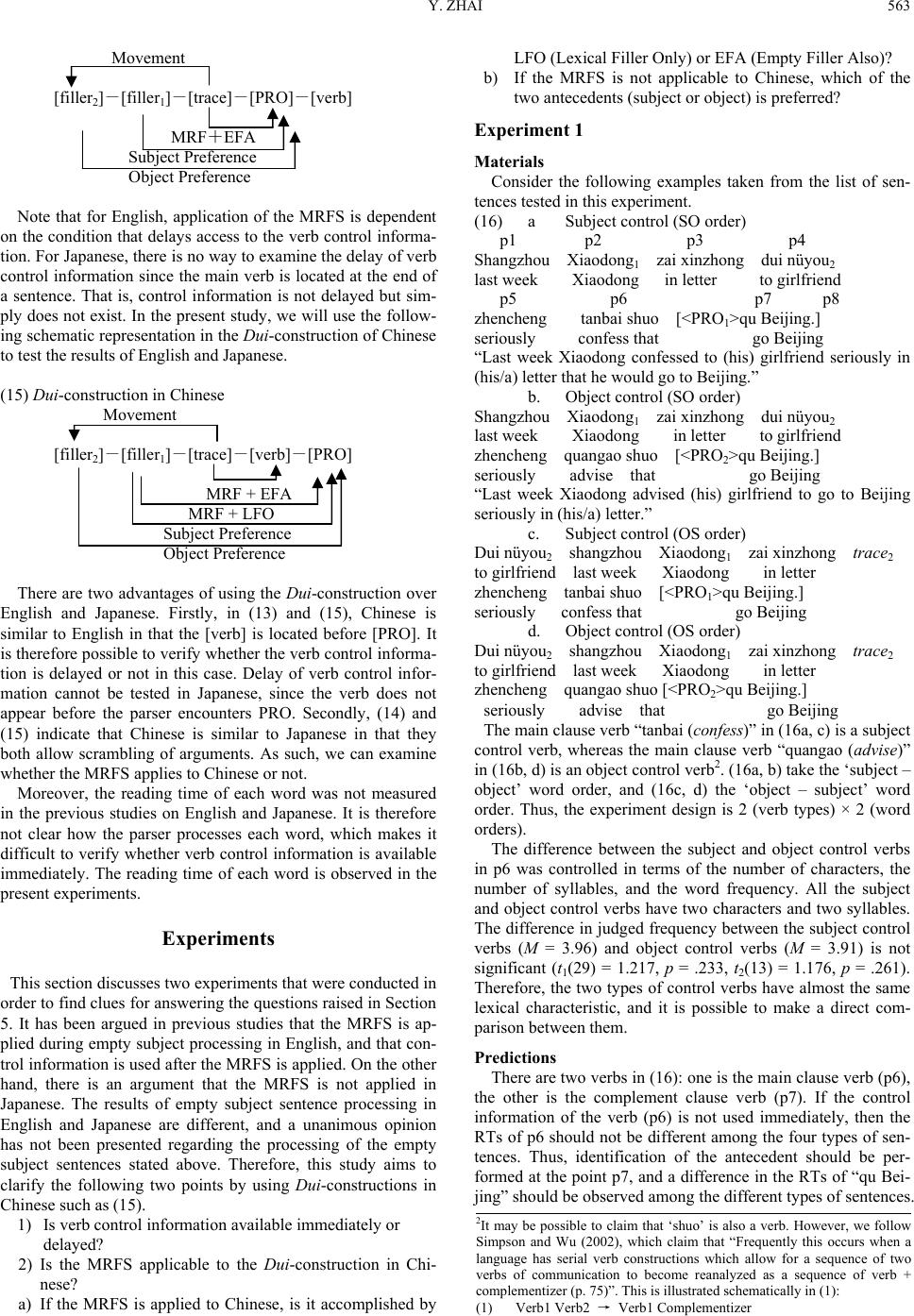

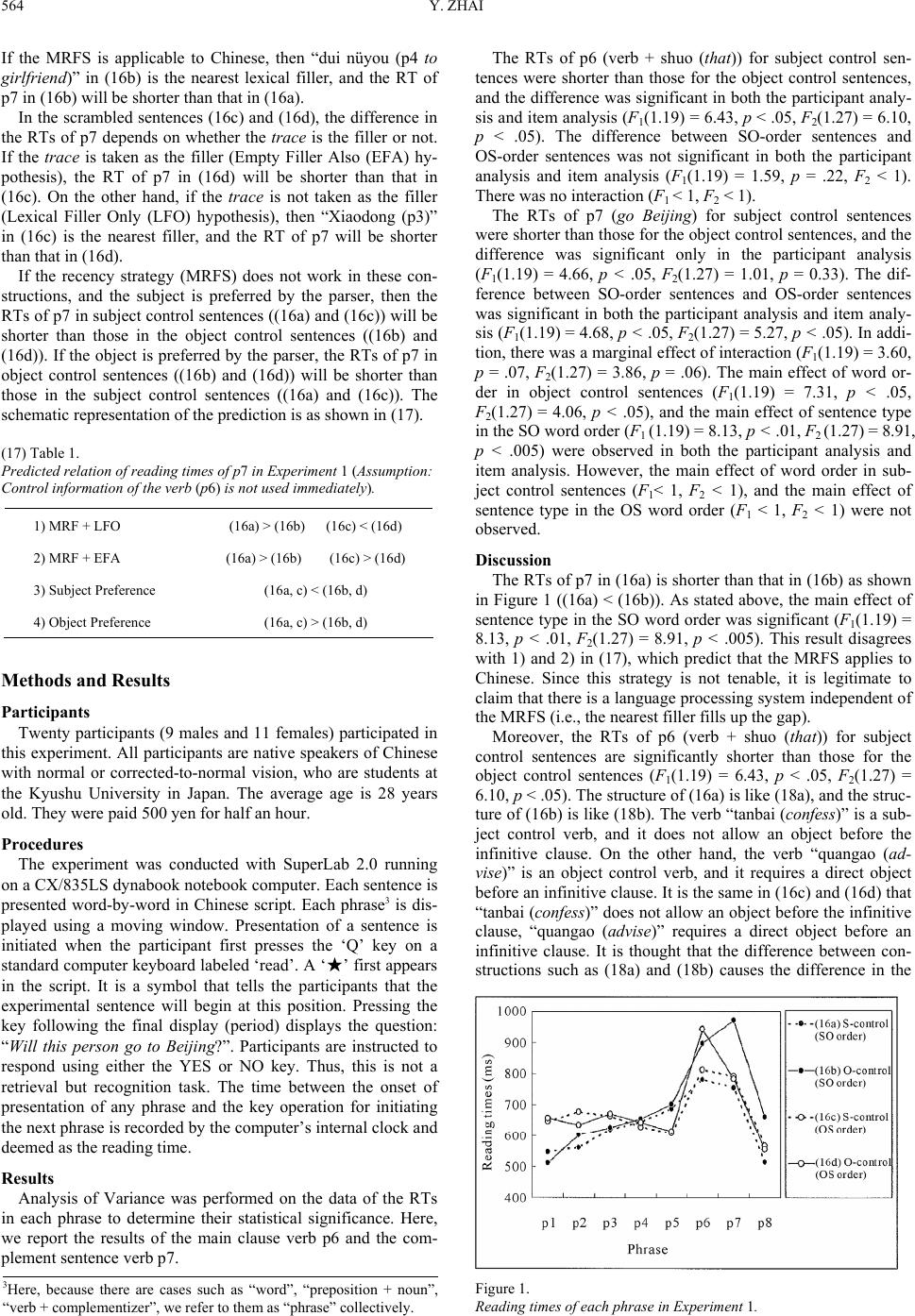

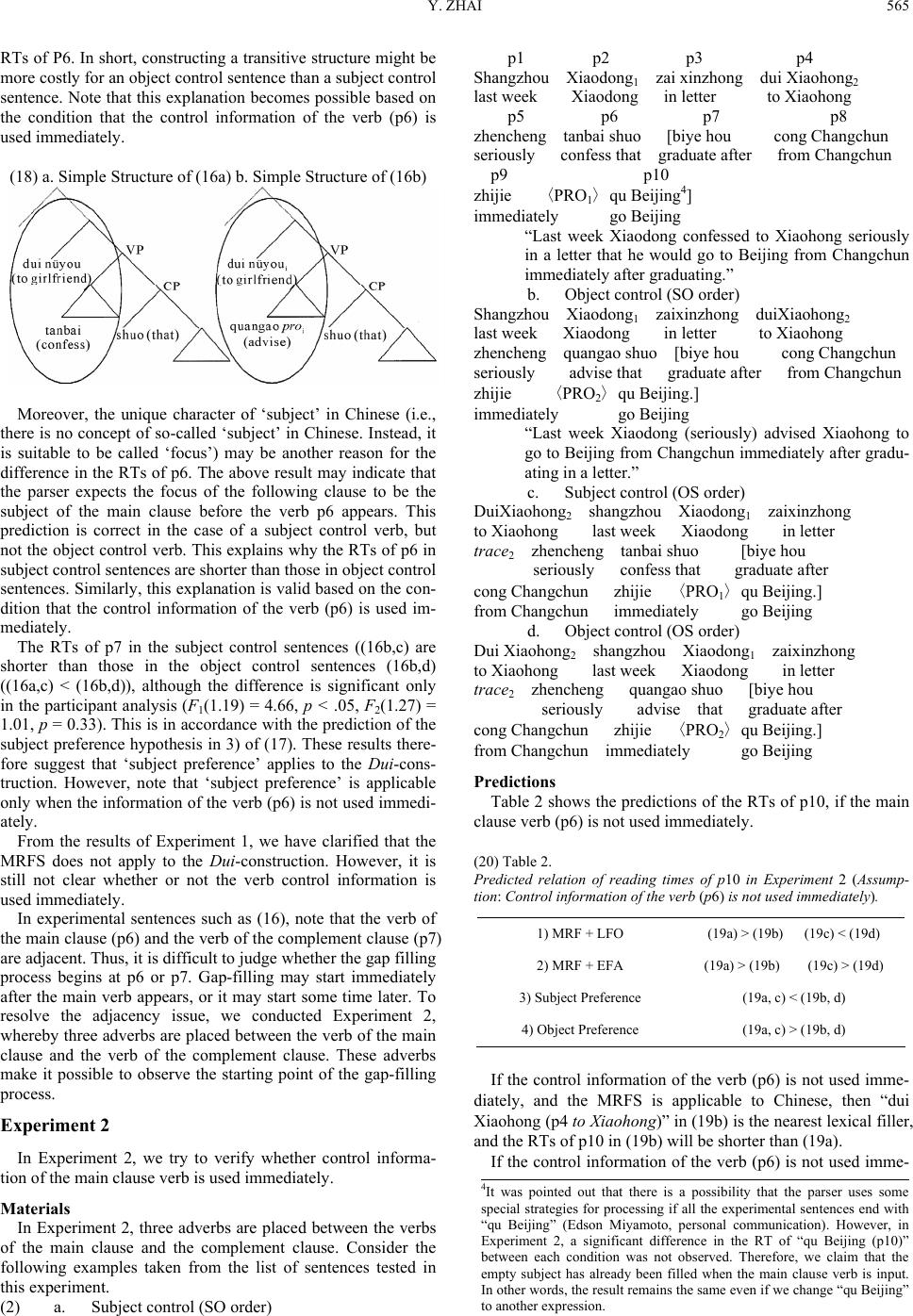

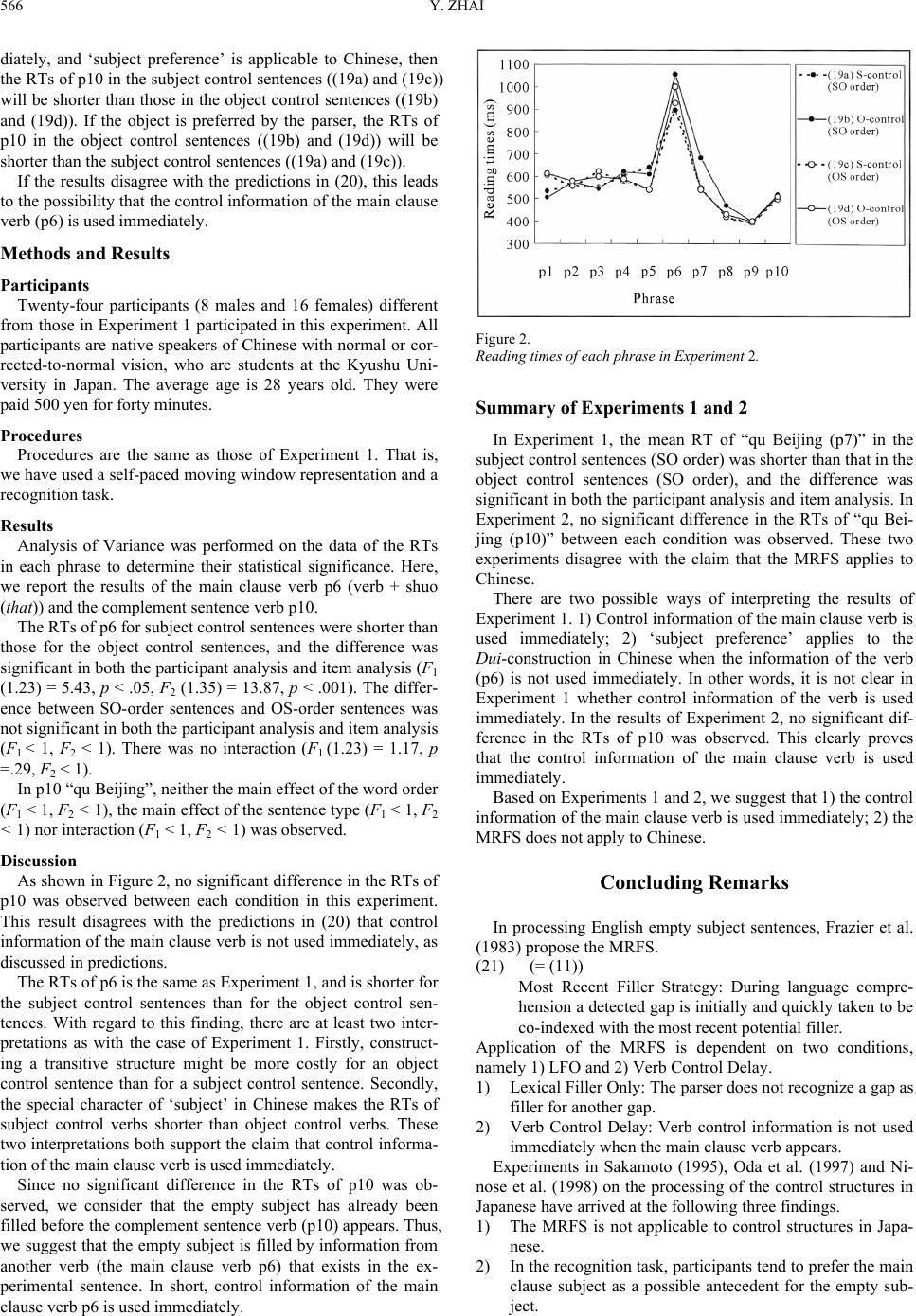

|