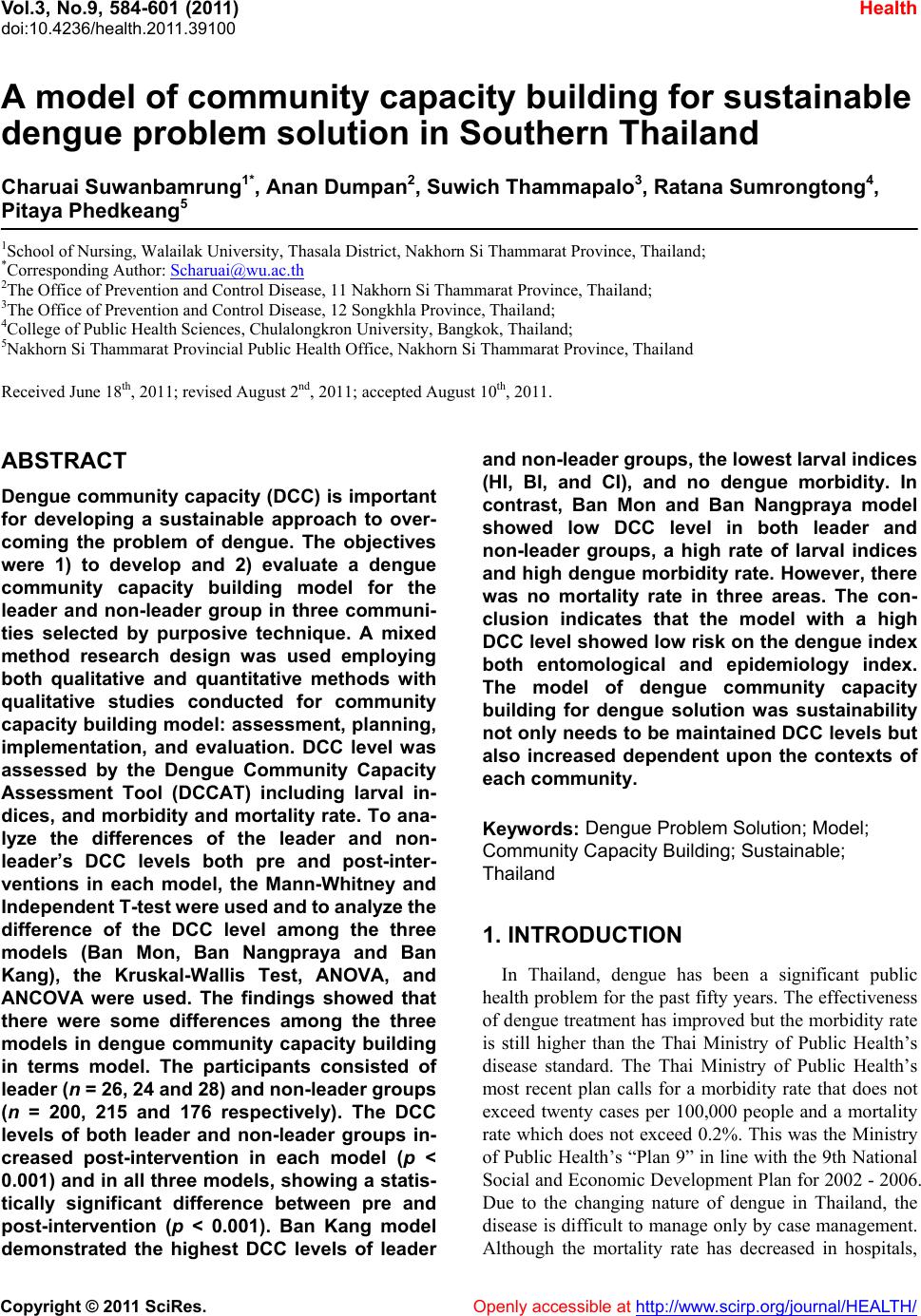

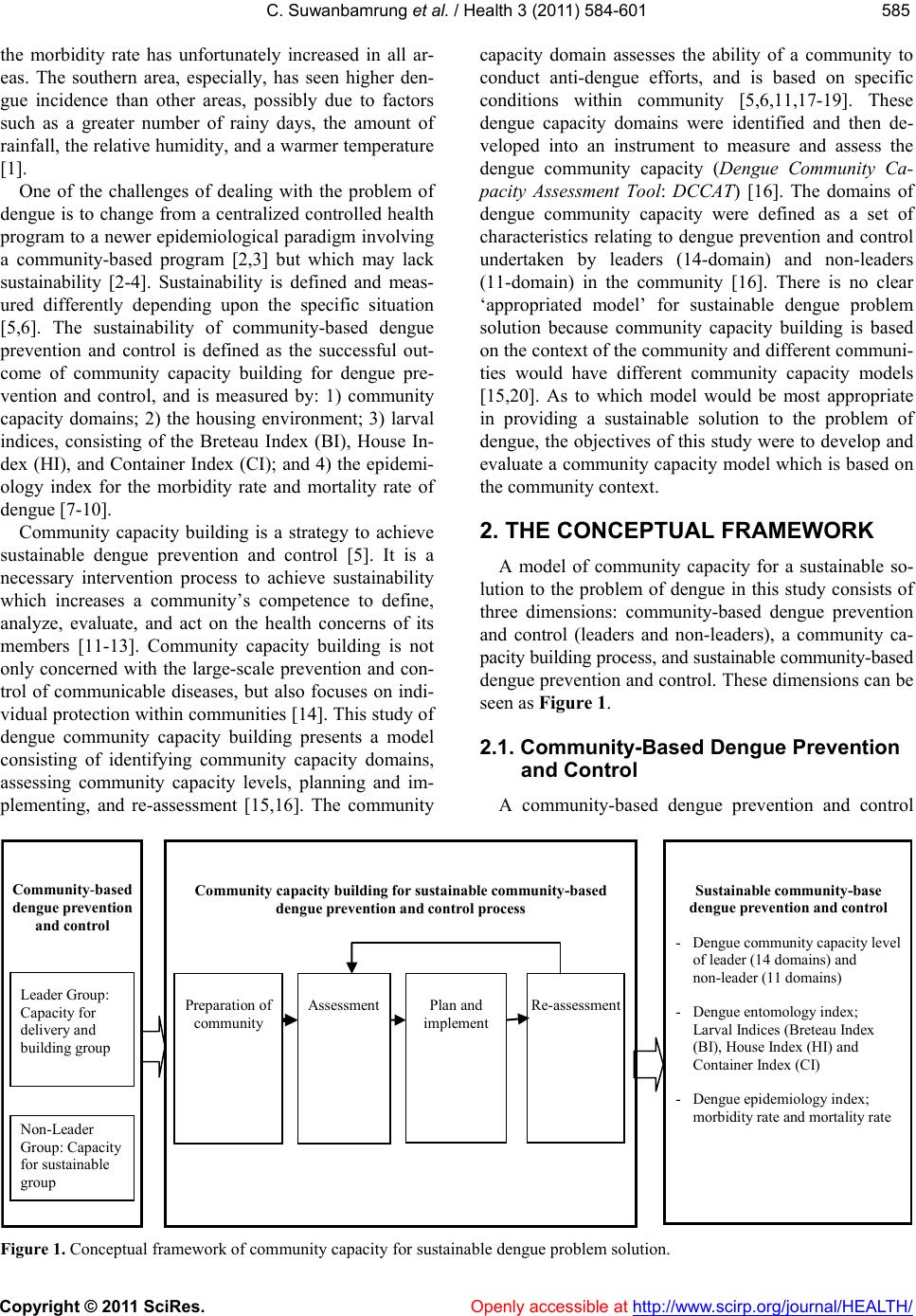

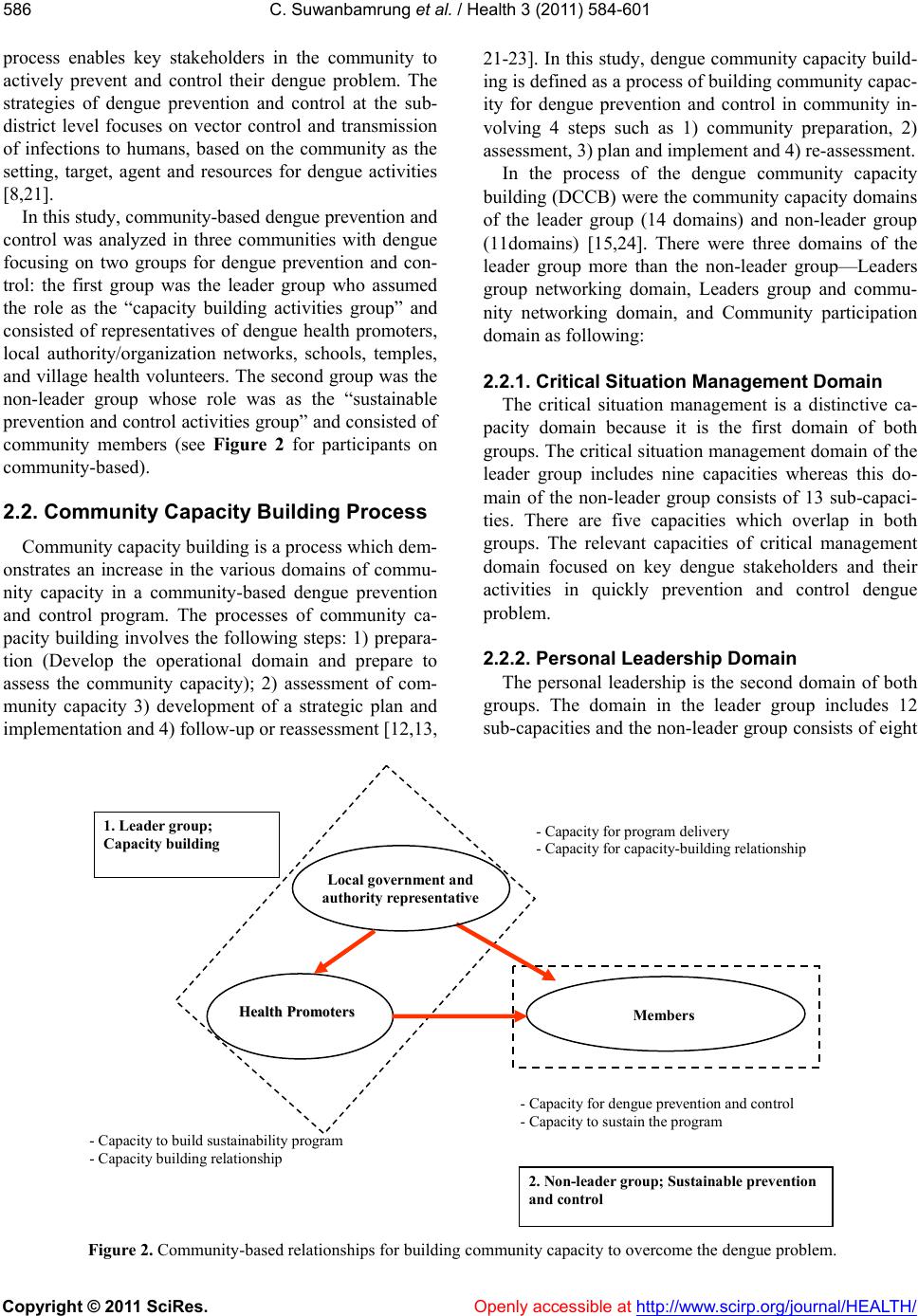

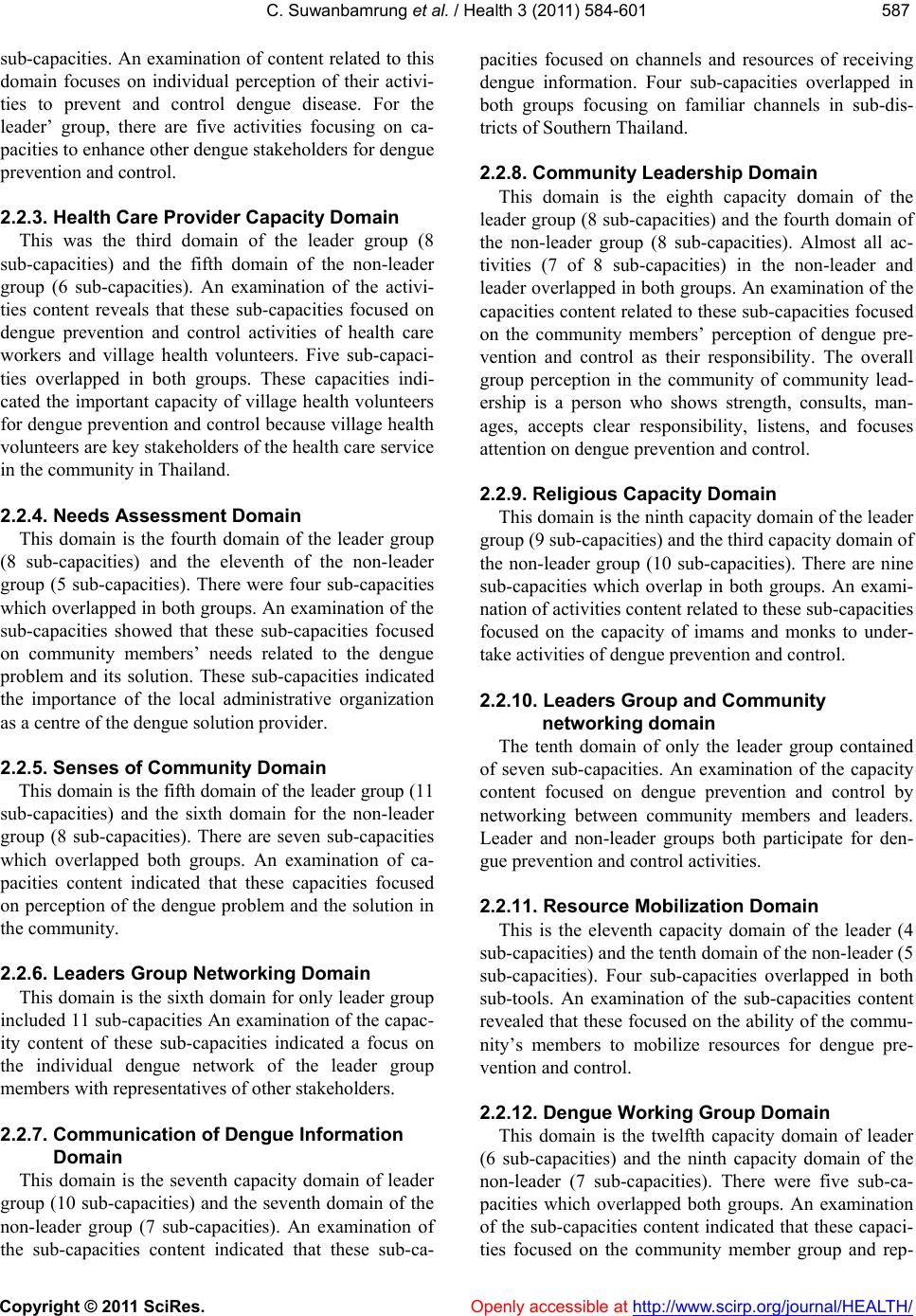

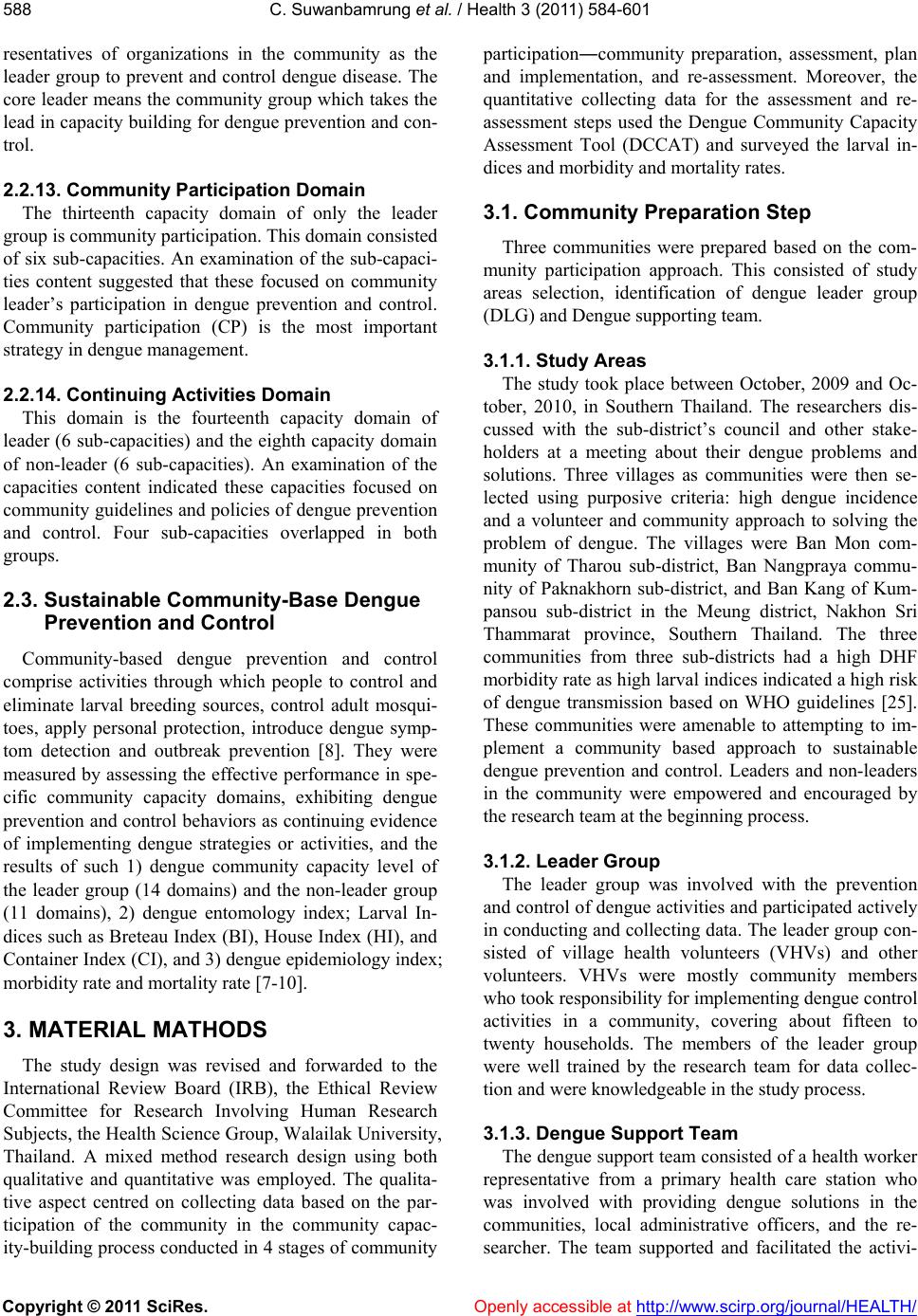

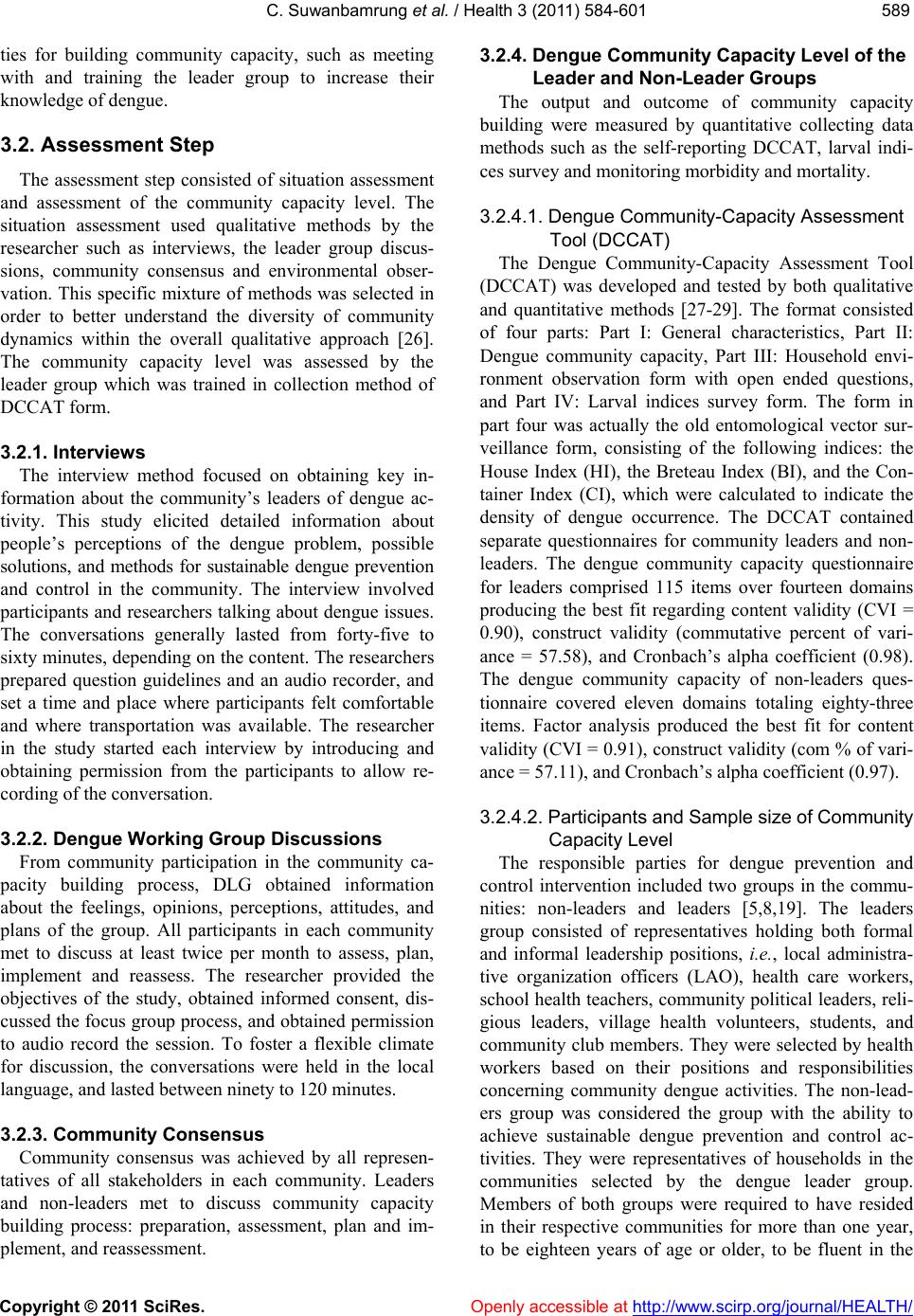

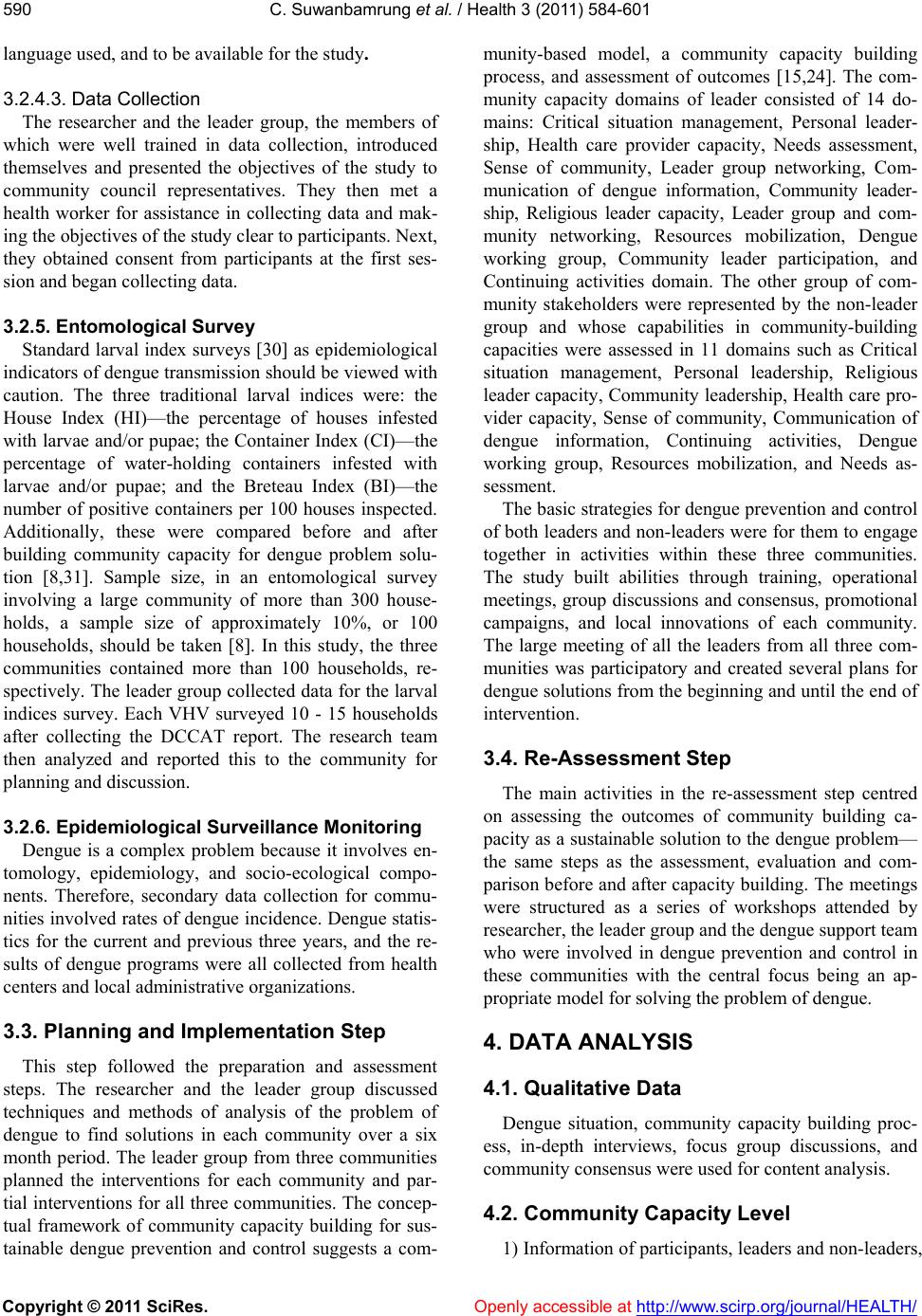

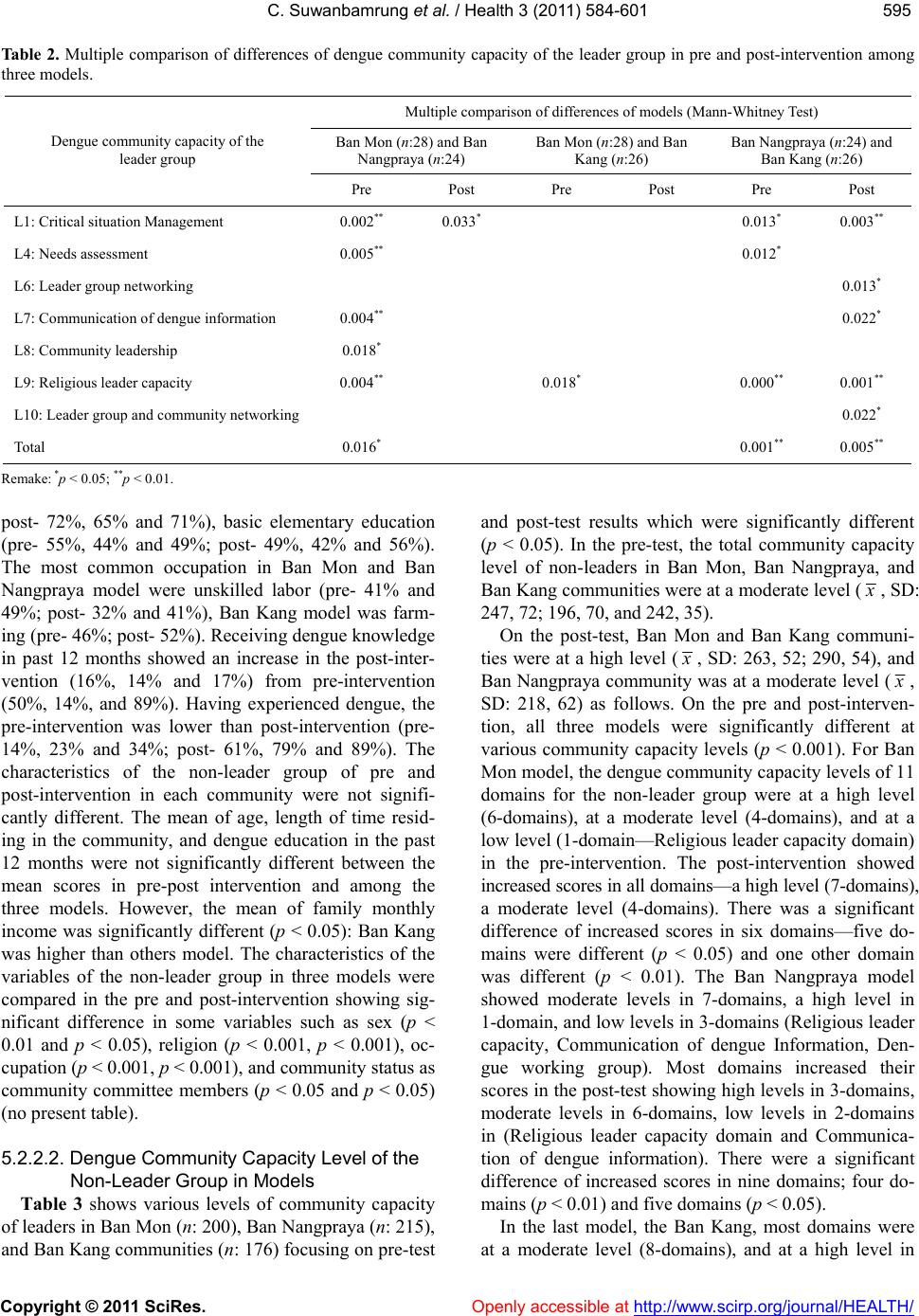

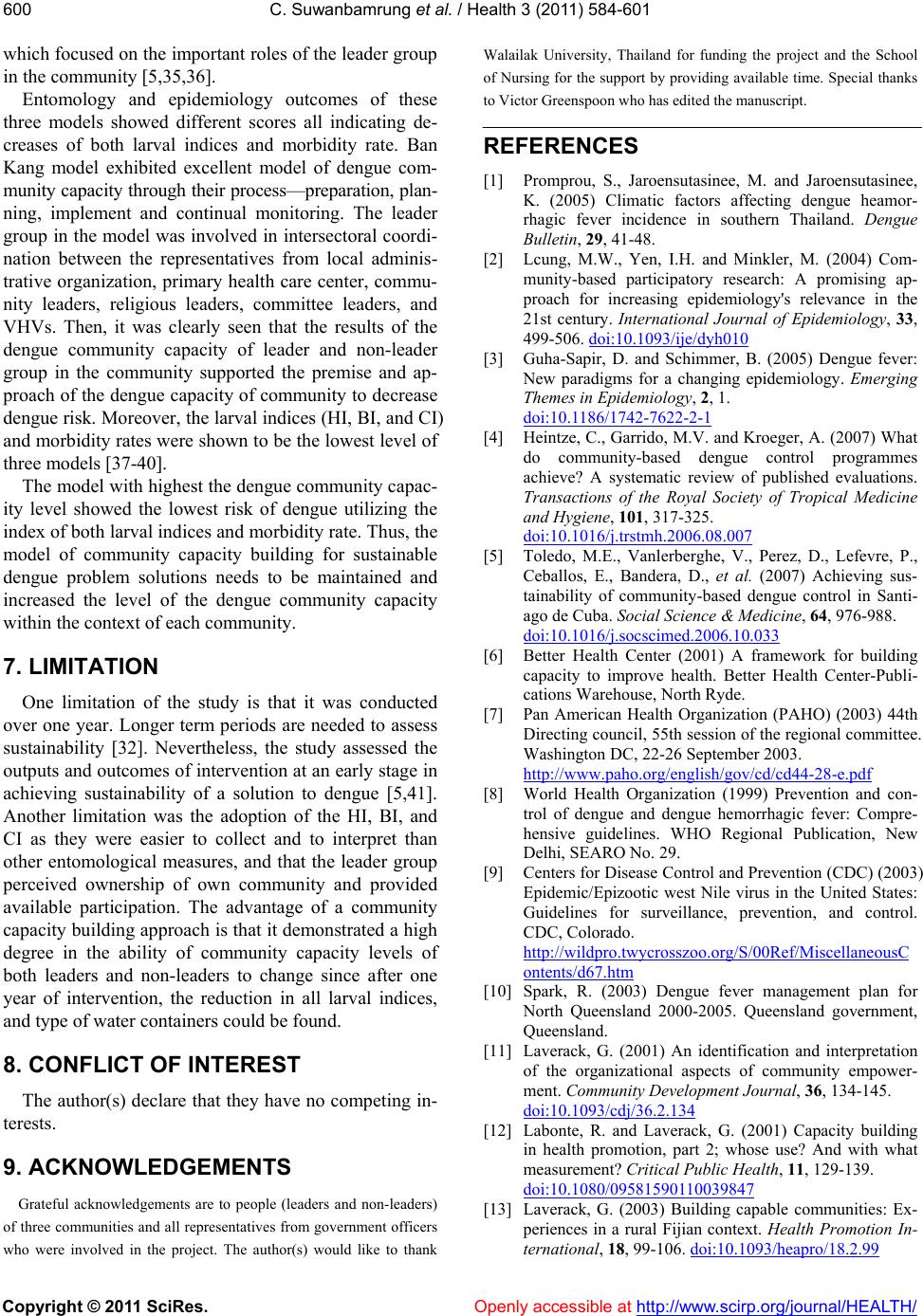

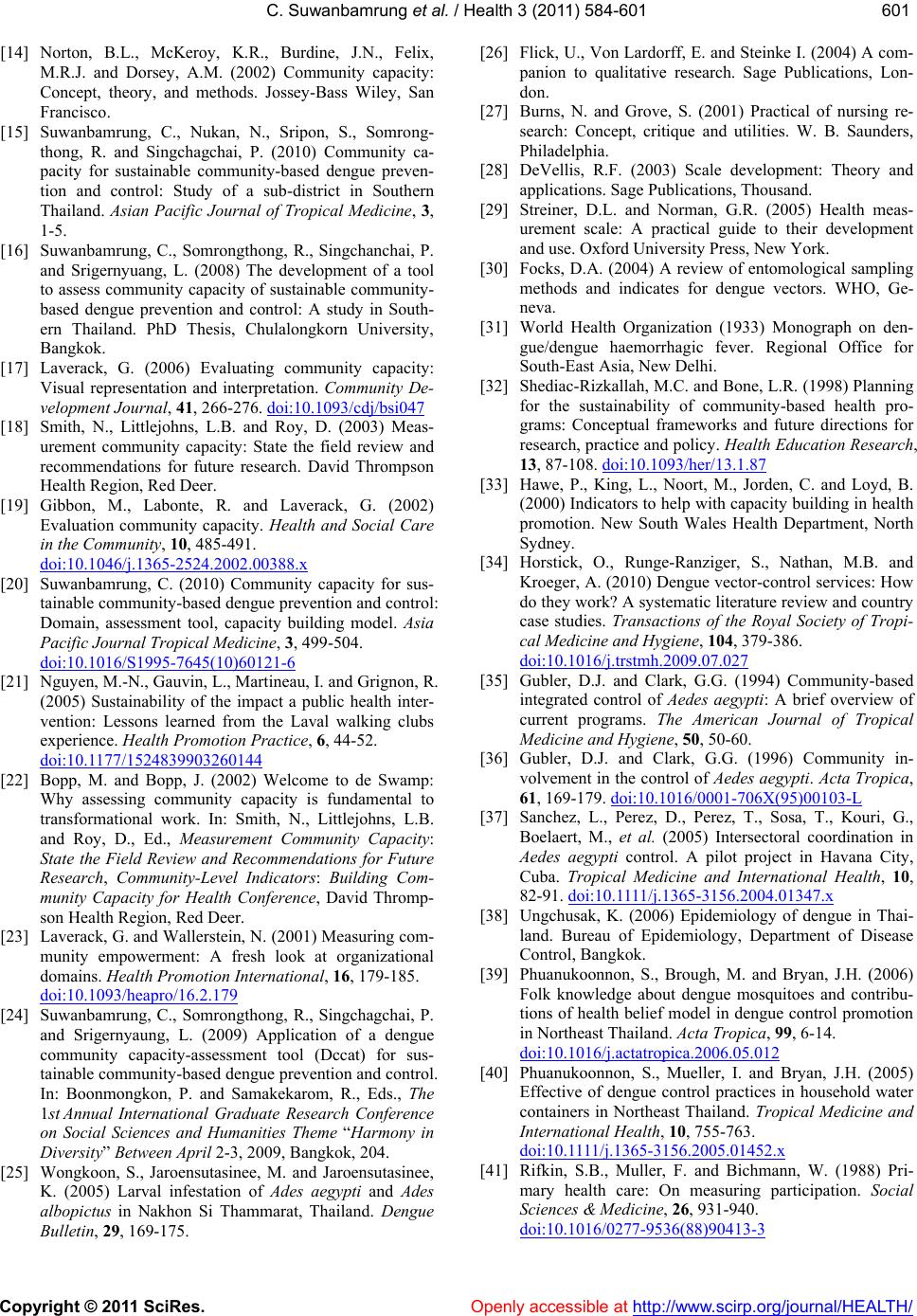

Vol.3, No.9, 584-601 (2011) doi:10.4236/health.2011.39100 C opyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ Health A model of community capacity building for sustainable dengue problem solution in Southern Thailand Charuai Suwanbamrung1*, Anan Dumpan2, Suw ich Thammapalo3, Ratana Sumrongtong4, Pitaya Phedkeang5 1School of Nursing, Walailak University, Thasala District, Nakhorn Si Thammarat Province, Thailand; *Corresponding Author: Scharuai@wu.ac.th 2The Office of Prevention and Control Disease, 11 Nakhorn Si Thammarat Province, Thailand; 3The Office of Prevention and Control Disease, 12 Songkhla Province, Thailand; 4College of Public Health Sciences, Chulalongkron University, Bangkok, Thailand; 5Nakhorn Si Thammarat Provincial Public Health Office, Nakhorn Si Thammarat Province, Thailand Received June 18th, 2011; revised August 2nd, 2011; accepted August 10th, 2011. ABSTRACT Dengue community capacity (DCC) is important for developing a sustainable approach to over- coming the problem of dengue. The objectives were 1) to develop and 2) evaluate a dengue community capacity building model for the leader and non-leader group in three communi- ties selected by purposive technique. A mixed method research design was used employing both qualitative and quantitative methods with qualitative studies conducted for community capacity building model: assessment, planning, implementation, and evaluation. DCC level was assessed by the Dengue Community Capacity Assessment Tool (DCCAT) including larval in- dices, and morbidity and mortality rate. To ana- lyze the differences of the leader and non- leader’s DCC levels both pre and post-inter- ventions in each model, the Mann-Whitney and Independent T-te st were used and to anal yze the difference of the DCC level among the three models (Ban Mon, Ban Nangpraya and Ban Kang), the Kruskal-Wallis Test, ANOVA, and ANCOVA were used. The findings showed that there were some differences among the three models in dengue community capacity building in terms model. The participants consisted of leader (n = 26, 24 and 2 8) and no n-lea der grou ps (n = 200, 215 and 176 respectively). The DCC levels of both leader and non-leader groups in- creased post-intervention in each model (p < 0.001) and in all three models, show ing a statis- tically significant difference between pre and post-intervention (p < 0.001). Ban Kang model demonstrated the highest DCC levels of leader and non-leader groups, the lowest larval indices (HI, BI, and CI), and no dengue morbidity. In contrast, Ban Mon and Ban Nangpraya model showed low DCC level in both leader and non-leader groups, a high rate of larval indices and high dengue morbidity rate. How ever, there was no mortality rate in three areas. The con- clusion indicates that the model with a high DCC level show ed low risk on the dengue index both entomological and epidemiology index. The model of dengue community capacity building for dengue solution was sustainability not only needs to be maintained DCC le vels but also increased dependent upon the contexts of each community. Keywords: Dengue Proble m Solution; Model; Community Capacity Building; Sustainable; Thailand 1. INTRODUCTION In Thailand, dengue has been a significant public health problem for the past fifty years. The effectiveness of dengue treatment has improved but the morbidity rate is still higher than the Thai Ministry of Public Health’s disease standard. The Thai Ministry of Public Health’s most recent plan calls for a morbidity rate that does not exceed twenty cases per 100,000 people and a mortality rate which does not exceed 0.2%. This was the Ministry of Public Health’s “Plan 9” in line with the 9th National Social and Economic Development Plan for 2002 - 2006. Due to the changing nature of dengue in Thailand, the disease is difficult to manage only by case management. Although the mortality rate has decreased in hospitals,  C. Suwanbamrung et al. / Health 3 (2011) 58 4-601 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 585585 the morbidity rate has unfortunately increased in all ar- eas. The southern area, especially, has seen higher den- gue incidence than other areas, possibly due to factors such as a greater number of rainy days, the amount of rainfall, the relative humidity, and a warmer temperature [1]. One of the challenges of dealing with the problem of dengue is to change from a centralized controlled health program to a newer epidemiological paradigm involving a community-based program [2,3] but which may lack sustainability [2-4]. Sustainability is defined and meas- ured differently depending upon the specific situation [5,6]. The sustainability of community-based dengue prevention and control is defined as the successful out- come of community capacity building for dengue pre- vention and control, and is measured by: 1) community capacity domains; 2) the housing environment; 3) larval indices, consisting of the Breteau Index (BI), House In- dex (HI), and Container Index (CI); and 4) the epidemi- ology index for the morbidity rate and mortality rate of dengue [7-10]. Community capacity building is a strategy to achieve sustainable dengue prevention and control [5]. It is a necessary intervention process to achieve sustainability which increases a community’s competence to define, analyze, evaluate, and act on the health concerns of its members [11-13]. Community capacity building is not only concerned with the large-scale prevention and con- trol of communicable diseases, but also focuses on indi- vidual protection within communities [14]. This study of dengue community capacity building presents a model consisting of identifying community capacity domains, assessing community capacity levels, planning and im- plementing, and re-assessment [15,16]. The community capacity domain assesses the ability of a community to conduct anti-dengue efforts, and is based on specific conditions within community [5,6,11,17-19]. These dengue capacity domains were identified and then de- veloped into an instrument to measure and assess the dengue community capacity (Dengue Community Ca- pacity Assessment Tool: DCCAT) [16]. The domains of dengue community capacity were defined as a set of characteristics relating to dengue prevention and control undertaken by leaders (14-domain) and non-leaders (11-domain) in the community [16]. There is no clear ‘appropriated model’ for sustainable dengue problem solution because community capacity building is based on the context of the community and different communi- ties would have different community capacity models [15,20]. As to which model would be most appropriate in providing a sustainable solution to the problem of dengue, the objectives of this study were to develop and evaluate a community capacity model which is based on the community context. 2. THE CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK A model of community capacity for a sustainable so- lution to the problem of dengue in this study consists of three dimensions: community-based dengue prevention and control (leaders and non-leaders), a community ca- pacity building process, and sustainable community-based dengue prevention and control. These dimensions can be seen as Figure 1. 2.1. Community-Based Dengue Prevention and Control A community-based dengue prevention and control Sustaina ble community -ba se dengue prevention and control - Dengue community capacity level of leader (14 domains) and non-leader (11 domains) - Dengue entomology index; Larval Indices (Breteau Index (BI), House Index (HI) and Container Index (CI) - Dengue epidemiology index; morbidity rate and mortality rate Community-based dengue prevention and control Non-Leader Group: Capacity for sustainable group Leader Group: Capacity for delivery and building group Community capac ity buildi ng for sustainable community-based dengue prevention and control process Assessment Plan and implement Re-assessment Preparation of community F igure 1. Conceptual framework of community capacity for sustainable dengue problem solution.  C. Suwanbamrung et al. / Health 3 (2011) 58 4-601 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 586 process enables key stakeholders in the community to actively prevent and control their dengue problem. The strategies of dengue prevention and control at the sub- district level focuses on vector control and transmission of infections to humans, based on the community as the setting, target, agent and resources for dengue activities [8,21]. In this study, community-based dengue prevention and control was analyzed in three communities with dengue focusing on two groups for dengue prevention and con- trol: the first group was the leader group who assumed the role as the “capacity building activities group” and consisted of representatives of dengue health promoters, local authority/organization networks, schools, temples, and village health volunteers. The second group was the non-leader group whose role was as the “sustainable prevention and control activities group” and consisted of community members (see Figure 2 for participants on community-based). 2.2. Community Capacity Building Process Community capacity building is a process which dem- onstrates an increase in the various domains of commu- nity capacity in a community-based dengue prevention and control program. The processes of community ca- pacity building involves the following steps: 1) prepara- tion (Develop the operational domain and prepare to assess the community capacity); 2) assessment of com- munity capacity 3) development of a strategic plan and implementation and 4) follow-up or reassessment [12,13, 21-23]. In this study, dengue community capacity build- ing is defined as a process of building community capac- ity for dengue prevention and control in community in- volving 4 steps such as 1) community preparation, 2) assessment, 3) plan and implement and 4) re-assessment. In the process of the dengue community capacity building (DCCB) were the community capacity domains of the leader group (14 domains) and non-leader group (11domains) [15,24]. There were three domains of the leader group more than the non-leader group—Leaders group networking domain, Leaders group and commu- nity networking domain, and Community participation domain as following: 2.2.1. Critical Situation Management Domain The critical situation management is a distinctive ca- pacity domain because it is the first domain of both groups. The critical situation management domain of the leader group includes nine capacities whereas this do- main of the non-leader group consists of 13 sub-capaci- ties. There are five capacities which overlap in both groups. The relevant capacities of critical management domain focused on key dengue stakeholders and their activities in quickly prevention and control dengue problem. 2.2.2. Personal Leadership Domain The personal leadership is the second domain of both groups. The domain in the leader group includes 12 sub-capacities and the non-leader group consists of eight - Capacity to build sustainability program - Capacity building relationship Local government and authority representative Members - Capacity for program delivery - Capacity for capacity-building relationship - Capacity for dengue prevention and control - Capacity to sustain the program H He ea al lt th h P Pr ro om mo ot te er rs s 1. Leader gr ou p; Capacity building 2. Non-lea d er group; Sustai nable preventio n and control Figure 2. Community-based relationships for building community capacity to overcome the dengue problem.  C. Suwanbamrung et al. / Health 3 (2011) 58 4-601 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 587587 sub-capacities. An examination of content related to this domain focuses on individual perception of their activi- ties to prevent and control dengue disease. For the leader’ group, there are five activities focusing on ca- pacities to enhance other dengue stakeholders for dengue prevention and control. 2.2.3. Health Care Provider Capacity Domain This was the third domain of the leader group (8 sub-capacities) and the fifth domain of the non-leader group (6 sub-capacities). An examination of the activi- ties content reveals that these sub-capacities focused on dengue prevention and control activities of health care workers and village health volunteers. Five sub-capaci- ties overlapped in both groups. These capacities indi- cated the important capacity of village health volunteers for dengue prevention and control because village health volunteers are key stakeholders of the health care service in the community in Thailand. 2.2.4. Needs Assessment Domain This domain is the fourth domain of the leader group (8 sub-capacities) and the eleventh of the non-leader group (5 sub-capacities). There were four sub-capacities which overlapped in both groups. An examination of the sub-capacities showed that these sub-capacities focused on community members’ needs related to the dengue problem and its solution. These sub-capacities indicated the importance of the local administrative organization as a centre of the dengue solution provider. 2.2.5. Senses of Community Domain This domain is the fifth domain of the leader group (11 sub-capacities) and the sixth domain for the non-leader group (8 sub-capacities). There are seven sub-capacities which overlapped both groups. An examination of ca- pacities content indicated that these capacities focused on perception of the dengue problem and the solution in the community. 2.2.6. Leaders Group Networking Domain This domain is the sixth domain for only leader group included 11 sub-capacities An examination of the capac- ity content of these sub-capacities indicated a focus on the individual dengue network of the leader group members with representatives of other stakeholders. 2.2.7. Communication of Dengue Information Domain This domain is the seventh capacity domain of leader group (10 sub-capacities) and the seventh domain of the non-leader group (7 sub-capacities). An examination of the sub-capacities content indicated that these sub-ca- pacities focused on channels and resources of receiving dengue information. Four sub-capacities overlapped in both groups focusing on familiar channels in sub-dis- tricts of Southern Thailand. 2.2.8. Community Leadership Domain This domain is the eighth capacity domain of the leader group (8 sub-capacities) and the fourth domain of the non-leader group (8 sub-capacities). Almost all ac- tivities (7 of 8 sub-capacities) in the non-leader and leader overlapped in both groups. An examination of the capacities content related to these sub-capacities focused on the community members’ perception of dengue pre- vention and control as their responsibility. The overall group perception in the community of community lead- ership is a person who shows strength, consults, man- ages, accepts clear responsibility, listens, and focuses attention on dengue prevention and control. 2.2.9. Religious Capacity Domain This domain is the ninth capacity domain of the leader group (9 sub-capacities) and the third capacity domain of the non-leader group (10 sub-capacities). There are nine sub-capacities which overlap in both groups. An exami- nation of activities content related to these sub-capacities focused on the capacity of imams and monks to under- take activities of dengue prevention and control. 2.2.10. Leaders Group and Communi ty networking domain The tenth domain of only the leader group contained of seven sub-capacities. An examination of the capacity content focused on dengue prevention and control by networking between community members and leaders. Leader and non-leader groups both participate for den- gue prevention and control activities. 2.2.11. Resource Mobilization Domain This is the eleventh capacity domain of the leader (4 sub-capacities) and the tenth domain of the non-leader (5 sub-capacities). Four sub-capacities overlapped in both sub-tools. An examination of the sub-capacities content revealed that these focused on the ability of the commu- nity’s members to mobilize resources for dengue pre- vention and control. 2.2.12. Dengue Working Group Domain This domain is the twelfth capacity domain of leader (6 sub-capacities) and the ninth capacity domain of the non-leader (7 sub-capacities). There were five sub-ca- pacities which overlapped both groups. An examination of the sub-capacities content indicated that these capaci- ties focused on the community member group and rep-  C. Suwanbamrung et al. / Health 3 (2011) 58 4-601 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 588 resentatives of organizations in the community as the leader group to prevent and control dengue disease. The core leader means the community group which takes the lead in capacity building for dengue prevention and con- trol. 2.2.13. Community Participation Domain The thirteenth capacity domain of only the leader group is community participation. This domain consisted of six sub-capacities. An examination of the sub-capaci- ties content suggested that these focused on community leader’s participation in dengue prevention and control. Community participation (CP) is the most important strategy in dengue management. 2.2.14. Continuing Activities Domain This domain is the fourteenth capacity domain of leader (6 sub-capacities) and the eighth capacity domain of non-leader (6 sub-capacities). An examination of the capacities content indicated these capacities focused on community guidelines and policies of dengue prevention and control. Four sub-capacities overlapped in both groups. 2.3. Sustainable Community-Base Dengue Prevention and Control Community-based dengue prevention and control comprise activities through which people to control and eliminate larval breeding sources, control adult mosqui- toes, apply personal protection, introduce dengue symp- tom detection and outbreak prevention [8]. They were measured by assessing the effective performance in spe- cific community capacity domains, exhibiting dengue prevention and control behaviors as continuing evidence of implementing dengue strategies or activities, and the results of such 1) dengue community capacity level of the leader group (14 domains) and the non-leader group (11 domains), 2) dengue entomology index; Larval In- dices such as Breteau Index (BI), House Index (HI), and Container Index (CI), and 3) dengue epidemiology index; morbidity rate and mortality rate [7-10]. 3. MATERIAL MATHODS The study design was revised and forwarded to the International Review Board (IRB), the Ethical Review Committee for Research Involving Human Research Subjects, the Health Science Group, Walailak University, Thailand. A mixed method research design using both qualitative and quantitative was employed. The qualita- tive aspect centred on collecting data based on the par- ticipation of the community in the community capac- ity-building process conducted in 4 stages of community participation―community preparation, assessment, plan and implementation, and re-assessment. Moreover, the quantitative collecting data for the assessment and re- assessment steps used the Dengue Community Capacity Assessment Tool (DCCAT) and surveyed the larval in- dices and morbidity and mortality rates. 3.1. Community Preparation Step Three communities were prepared based on the com- munity participation approach. This consisted of study areas selection, identification of dengue leader group (DLG) and Dengue supporting team. 3.1.1. Study Areas The study took place between October, 2009 and Oc- tober, 2010, in Southern Thailand. The researchers dis- cussed with the sub-district’s council and other stake- holders at a meeting about their dengue problems and solutions. Three villages as communities were then se- lected using purposive criteria: high dengue incidence and a volunteer and community approach to solving the problem of dengue. The villages were Ban Mon com- munity of Tharou sub-district, Ban Nangpraya commu- nity of Paknakhorn sub-district, and Ban Kang of Kum- pansou sub-district in the Meung district, Nakhon Sri Thammarat province, Southern Thailand. The three communities from three sub-districts had a high DHF morbidity rate as high larval indices indicated a high risk of dengue transmission based on WHO guidelines [25]. These communities were amenable to attempting to im- plement a community based approach to sustainable dengue prevention and control. Leaders and non-leaders in the community were empowered and encouraged by the research team at the beginning process. 3.1.2. Leader Group The leader group was involved with the prevention and control of dengue activities and participated actively in conducting and collecting data. The leader group con- sisted of village health volunteers (VHVs) and other volunteers. VHVs were mostly community members who took responsibility for implementing dengue control activities in a community, covering about fifteen to twenty households. The members of the leader group were well trained by the research team for data collec- tion and were knowledgeable in the study process. 3.1.3. Dengue Support Team The dengue support team consisted of a health worker representative from a primary health care station who was involved with providing dengue solutions in the communities, local administrative officers, and the re- searcher. The team supported and facilitated the activi-  C. Suwanbamrung et al. / Health 3 (2011) 58 4-601 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 589589 ties for building community capacity, such as meeting with and training the leader group to increase their knowledge of dengue. 3.2. Assessment Step The assessment step consisted of situation assessment and assessment of the community capacity level. The situation assessment used qualitative methods by the researcher such as interviews, the leader group discus- sions, community consensus and environmental obser- vation. This specific mixture of methods was selected in order to better understand the diversity of community dynamics within the overall qualitative approach [26]. The community capacity level was assessed by the leader group which was trained in collection method of DCCAT form. 3.2.1. Interviews The interview method focused on obtaining key in- formation about the community’s leaders of dengue ac- tivity. This study elicited detailed information about people’s perceptions of the dengue problem, possible solutions, and methods for sustainable dengue prevention and control in the community. The interview involved participants and researchers talking about dengue issues. The conversations generally lasted from forty-five to sixty minutes, depending on the content. The researchers prepared question guidelines and an audio recorder, and set a time and place where participants felt comfortable and where transportation was available. The researcher in the study started each interview by introducing and obtaining permission from the participants to allow re- cording of the conversation. 3.2.2. Dengue Working Group Discus sions From community participation in the community ca- pacity building process, DLG obtained information about the feelings, opinions, perceptions, attitudes, and plans of the group. All participants in each community met to discuss at least twice per month to assess, plan, implement and reassess. The researcher provided the objectives of the study, obtained informed consent, dis- cussed the focus group process, and obtained permission to audio record the session. To foster a flexible climate for discussion, the conversations were held in the local language, and lasted between ninety to 120 minutes. 3.2.3. Community Consensus Community consensus was achieved by all represen- tatives of all stakeholders in each community. Leaders and non-leaders met to discuss community capacity building process: preparation, assessment, plan and im- plement, and reassessment. 3.2.4. Dengue Community Capacity Level of the Leader and Non -Leader Groups The output and outcome of community capacity building were measured by quantitative collecting data methods such as the self-reporting DCCAT, larval indi- ces survey and monitoring morbidity and mortality. 3.2.4.1. Dengue Community-Capacity Assessment Tool (DCCAT) The Dengue Community-Capacity Assessment Tool (DCCAT) was developed and tested by both qualitative and quantitative methods [27-29]. The format consisted of four parts: Part I: General characteristics, Part II: Dengue community capacity, Part III: Household envi- ronment observation form with open ended questions, and Part IV: Larval indices survey form. The form in part four was actually the old entomological vector sur- veillance form, consisting of the following indices: the House Index (HI), the Breteau Index (BI), and the Con- tainer Index (CI), which were calculated to indicate the density of dengue occurrence. The DCCAT contained separate questionnaires for community leaders and non- leaders. The dengue community capacity questionnaire for leaders comprised 115 items over fourteen domains producing the best fit regarding content validity (CVI = 0.90), construct validity (commutative percent of vari- ance = 57.58), and Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (0.98). The dengue community capacity of non-leaders ques- tionnaire covered eleven domains totaling eighty-three items. Factor analysis produced the best fit for content validity (CVI = 0.91), construct validity (com % of vari- ance = 57.11), and Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (0.97). 3.2.4.2. Partic ipant s and S ampl e si ze of C omm unity Capacity Level The responsible parties for dengue prevention and control intervention included two groups in the commu- nities: non-leaders and leaders [5,8,19]. The leaders group consisted of representatives holding both formal and informal leadership positions, i.e., local administra- tive organization officers (LAO), health care workers, school health teachers, community political leaders, reli- gious leaders, village health volunteers, students, and community club members. They were selected by health workers based on their positions and responsibilities concerning community dengue activities. The non-lead- ers group was considered the group with the ability to achieve sustainable dengue prevention and control ac- tivities. They were representatives of households in the communities selected by the dengue leader group. Members of both groups were required to have resided in their respective communities for more than one year, to be eighteen years of age or older, to be fluent in the  C. Suwanbamrung et al. / Health 3 (2011) 58 4-601 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 590 language used, and to be available for the study. 3.2.4.3. Data Collection The researcher and the leader group, the members of which were well trained in data collection, introduced themselves and presented the objectives of the study to community council representatives. They then met a health worker for assistance in collecting data and mak- ing the objectives of the study clear to participants. Next, they obtained consent from participants at the first ses- sion and began collecting data. 3.2.5. Entomological Survey Standard larval index surveys [30] as epidemiological indicators of dengue transmission should be viewed with caution. The three traditional larval indices were: the House Index (HI)—the percentage of houses infested with larvae and/or pupae; the Container Index (CI)—the percentage of water-holding containers infested with larvae and/or pupae; and the Breteau Index (BI)—the number of positive containers per 100 houses inspected. Additionally, these were compared before and after building community capacity for dengue problem solu- tion [8,31]. Sample size, in an entomological survey involving a large community of more than 300 house- holds, a sample size of approximately 10%, or 100 households, should be taken [8]. In this study, the three communities contained more than 100 households, re- spectively. The leader group collected data for the larval indices survey. Each VHV surveyed 10 - 15 households after collecting the DCCAT report. The research team then analyzed and reported this to the community for planning and discussion. 3.2.6. Epidemiological Surveillance Monitoring Dengue is a complex problem because it involves en- tomology, epidemiology, and socio-ecological compo- nents. Therefore, secondary data collection for commu- nities involved rates of dengue incidence. Dengue statis- tics for the current and previous three years, and the re- sults of dengue programs were all collected from health centers and local administrative organizations. 3.3. Planning and Implementation Step This step followed the preparation and assessment steps. The researcher and the leader group discussed techniques and methods of analysis of the problem of dengue to find solutions in each community over a six month period. The leader group from three communities planned the interventions for each community and par- tial interventions for all three communities. The concep- tual framework of community capacity building for sus- tainable dengue prevention and control suggests a com- munity-based model, a community capacity building process, and assessment of outcomes [15,24]. The com- munity capacity domains of leader consisted of 14 do- mains: Critical situation management, Personal leader- ship, Health care provider capacity, Needs assessment, Sense of community, Leader group networking, Com- munication of dengue information, Community leader- ship, Religious leader capacity, Leader group and com- munity networking, Resources mobilization, Dengue working group, Community leader participation, and Continuing activities domain. The other group of com- munity stakeholders were represented by the non-leader group and whose capabilities in community-building capacities were assessed in 11 domains such as Critical situation management, Personal leadership, Religious leader capacity, Community leadership, Health care pro- vider capacity, Sense of community, Communication of dengue information, Continuing activities, Dengue working group, Resources mobilization, and Needs as- sessment. The basic strategies for dengue prevention and control of both leaders and non-leaders were for them to engage together in activities within these three communities. The study built abilities through training, operational meetings, group discussions and consensus, promotional campaigns, and local innovations of each community. The large meeting of all the leaders from all three com- munities was participatory and created several plans for dengue solutions from the beginning and until the end of intervention. 3.4. Re-Assessment Step The main activities in the re-assessment step centred on assessing the outcomes of community building ca- pacity as a sustainable solution to the dengue problem— the same steps as the assessment, evaluation and com- parison before and after capacity building. The meetings were structured as a series of workshops attended by researcher, the leader group and the dengue support team who were involved in dengue prevention and control in these communities with the central focus being an ap- propriate model for solving the problem of dengue. 4. DATA ANALYSIS 4.1. Qualitative Data Dengue situation, community capacity building proc- ess, in-depth interviews, focus group discussions, and community consensus were used for content analysis. 4.2. Community Capacity Level 1) Information of participants, leaders and non-leaders,  C. Suwanbamrung et al. / Health 3 (2011) 58 4-601 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 591591 were collated by descriptive statistics, percentage, mean, and standard deviation. 2) Dengue community capacity was analyzed with descriptive statistics and was divided into different do- mains for each group of participants. The dengue com- munity capacity questionnaire for leaders consisted of115 items covering fourteen domains. The range of mean scores was divided into five levels for ranking purposes: very low, low, moderate, high, and very high. The questionnaire for non-leaders consisted of eighty- three items divided among eleven domains. The mean score categories were divided into five levels such as very low, low, moderate, high, and very high. 3) The differences of the leader and non-leader group’s capacity levels used the Mann-Whitney and Independent T-test to compare these groups pre and post-intervention for building community capacity. The difference be- tween community capacities among three models used the Kruskal-Wallis Test, ANOVA, and ANCOVA. 4.3. Dengue Entomological Index and Data of Main Breeding Sites This study only used larval indices which were ana- lyzed as the House Index (HI)—the percentage of houses infested with larvae and/or pupae; the Container Index (CI)—the percentage of water-holding containers in- fested with larvae and/or pupae; and the Breteau Index (BI)—the number of positive containers per 100 houses inspected. 4.4. Dengue Epidemiological Index Morbidity and mortality rates of dengue were ana- lyzed based on information from health care centers in communities. 5. RESULTS The results of study showed 4 sections: 1) the model of community capacity building in three communities, and 2) Sustainable outcome of dengue problem solution model were consisted of dengue community capacity level (leader and non-leader group), 3) dengue entomol- ogy index, and 4) dengue epidemiology index. 5.1. The Model of Community Capacity Building in Three Communities Leader and non-leader group, Ban Mon, Ban Nanghraya, and Ban Kang model were the leader group (26, 24, and 28) and the non-leader group (200, 215, and 176). The research team, support team, and the leader group used discussion techniques and carried out analysis of the dengue problem in each model over a 13 months period (October, 2009-October, 2010). The leader group in the three models planned the interventions and partial inter- ventions for each model as well as joint interventions for all three models. Both groups volunteered to participate in the dengue capacity building process. The three models followed the concept of the dengue community capacity building process with its four steps: preparation, assessment, planning and implementation, and re-assessment. Meetings of the leader and non- leader groups for all four steps of activities were held at least once monthly throughout the study. Planning and implement activities were achieved through consensus of the community based on their particular context and the resources in their community. Each community devel- oped a complete action plan and implemented activities appropriate to the context of their communities. 1) Ban Mon model, it was a village at a crossroads community selected by representatives of the local ad- ministrative organization, health center, community leader, religion leader, and village health volunteers. The community consisted of 320 households, a health center, a utility building, a temple, and a community school. Most households were situated near a large road which was the crossroads of a semi-urban community and had 4 to 6 months with rainy day in a year in an area that was low with still water in several areas. The model imple- mented four activities based on the specific problems and available community resources such as conducting a dengue prevention and control campaign, communica- tion from their community leaders, obtaining community consensus for dengue prevention and control from local administrative organizations, and meeting of the dengue leaders group once mouth. The Ban Mon model had eight issues that showed up in the pre-test: 1) poor environment, 2) community needs more of everything, 3) lack of capacity of health center officer, 4) misconceptions in the of use of chemical in- secticides, 5) deficit of dengue knowledge, 6) commu- nity resources management, 7) low community partici- pation, and 8) lack of continuity. For example, some participants said that chemical fogging teams showed a lack of knowledge in using chemicals which were used in fogging by such statements as if there were an out- break of dengue illness, there “needs to be chemical fogging 2 - 3 times per month” and “needs fogging fre- quency”. After intervention, leaders and non-leaders’ suggestions in Ban Mon were fewer than pre and post- intervention: 1) poor environment, 2) capacity of health center official, 3) misconception in using chemical, 4) deficit of dengue knowledge, 5) community participation. For example, some participants said: “no clear dengue information provided” “should give information for every household in community and take real survey”.  C. Suwanbamrung et al. / Health 3 (2011) 58 4-601 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 592 2) Ban Nangpraya model, it was a seaside community in Pak Na Khorn sub-district selected by representatives of all stakeholders in the community. The community was semi-urban; with households situated closely and with more than 10 houses per group. It consisted of total of 344 households, an all-purpose building, a temple, a community school, a health center, a local district or- ganization, community leaders, and village health vol- unteers. Fishing and unskilled labor was the occupation of most of the community. The model was three special activities—community communication of dengue knowledge, employing red lime for use in water containers as in the community. There were many water containers per house, meeting of DLG once a month to monitor and evaluate the program. In Ban Nangpraya community, leader and non-leader groups pointed out six issues: 1) poor environment be- cause of low land and more water containers, 2) com- munity needs all stakeholders to solve the dengue prob- lem, 3) dengue information communication, 4) deficit of capacity of health center officials, 5) dengue knowledge of community, and 6) low community participation. For example, some participant said: “there should be meet- ing of dengue management among people, VHVs and health center official…”, “most people in community had little knowledge of dengue”, “breeding sites were many…”, “no clear dengue campaigns whereby people receive true information” “…no government officials who were really responsibility so people in community are not attentive for prevention and disease control” “No promotion of dengue campaign and dengue information transfer…needs VHVs help to inform about dengue prevention and control”. The intervention finished the post-intervention showed decreased suggestions of only four issues: 1) poor environment, 2) lack of knowledge of dengue prevention and control, 3) lack of capacity of health center officials, and 4) low community participa- tion. For example, some participant said: “community has more forests and canals...cannot cover the entire area…villagers help only their own households to cover water containers and cultivate citronella” “needs to broadcast dengue information...increased broadcasts are beneficial”. 3) Ban Kang model, it was a small village in a sub- district near Meung district consisting of 239 households, an all-purpose building, a temple, a mosque, a commu- nity school, a health center, a local district organization, community leaders, and village health volunteers. There were two religions; Buddhism (70%) and Muslim (30%). Most people in the community were rubber tappers and fruit farmers with the gardens of risk as mosquito breed- ing place. Ban Kang was the garden model carried out three ac- tivities—a mobile meeting of the DLG conducted in each area of the community, mass communication from leaders of religion and the community leaders, and door to door survey of larval index once a month by DLG. Moreover, there were the strongest of leader and non- leader participation in all activities such as environment in and out houses for elimination dengue sources. The initially identified issues of Ban Kang model were six such as 1) not clear who are the VHVs and health center official, 2) community participation needs to be strengthened, 3) lack of continuity of activities, 4) unclear dengue information, 5) misconceptions concern- ing chemical fogging, and 6) unclear community con- sensus. At the completion of the intervention process, the community had fewer suggestions from the leader and non-leader groups. The major issues were a partially poor environment, lack of community participation, and inadequate dengue information communication. Summary, the dengue community capacity building process of these three models carried out different ac- tivities based on the same four steps. The basic strategies and resulting activities for the prevention and control of dengue in these three communities evolved into the dengue community network. The dengue network car- ried out seven activities—meeting to prepare plan for intervention, chemical fogging training for control after dengue morbidity in community, herbal training to de- velop a citronellas bank, developing a Gambia fish bank, establishing community radio to share dengue knowl- edge, carrying out a larval index survey every month, developing leadership training, and evaluation meeting. Overall, the issues and suggestions of all three models decreased at the end of intervention process. Community consensus contributed towards the building of commu- nity capacity, activities for prevention and control were undertaken appropriate for the context of community, and there was commitment to continue activities as the model for overcoming the problem of dengue. For ex- ample, some participants said: “the community (all peo- ple in the community) needs to continue all activities to solve the problem of dengue solution...thank you for the project ” “...as the past one year of conducting the den- gue program...our community was attentive to dengue prevention and control...however, we will be continuing the program” 5.2. Sustainable Outcome of Dengue Problem Solution Sustainable outcome of dengue problem solution was the results of the study consisted of dengue community capacity level, dengue entomology index, and dengue epidemiology index.  C. Suwanbamrung et al. / Health 3 (2011) 58 4-601 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 593593 5.2.1. Dengue Community Capacity Level of the Leader Group 5.2.1.1. Charact eristics of the Leader Group The characteristics of the leader group pre and post building dengue community capacity in three models in Ban Mon, Ban Nangpraya, and Ban Kang models were 28, 24, and 26 respectively. The majority percentage (%) of participants in Ban Mon, Ban Nangpraya, and Ban Kang model were female (Pre- 75%, 83%, and 46%; Post- 86%, 83% and 58%), Buddhist (Pre- 100%, 100% and 69%: Post- 100%, 100% and 65%), married (Pre- 72%, 84% and 82%; Post- 72%, 84% and 82%), basic elementary (Pre- 39%, 38% and 23%; Post- 55%, 38% and 15%), most common occupation; Ban Mon (Un- skilled laborer; Pre- 27% and post- 25%), Ban Nang- praya (Homemaker; 59% and 49%), and Ban Kang (Farming; Pre 65% and post 62%). Highest positions in community were the village health volunteers (Pre- 72%, 79% and 62%: 72%, 67% and 85%). Receiving dengue knowledge in the past 12 months showed an increase in the post-intervention (61%, 79% and 89%) from pre- intervention (50%, 14%, and 89%). Having experienced dengue on the pre-intervention was lower than on post- intervention (50%, 14% and 89%: 61%, 79% and 89%) (no present table). The characteristics of the leader group of pre and post-intervention in each model were not significantly different. The mean age, the length of time residing in the community, and dengue education time in the past 12 months were not significantly different in their mean scores in the pre-post tests and among three different communities. However, the mean of family monthly income was significantly different (p < 0.05); Ban Kang was higher than the other model (no present table). The characteristics of the variables of the leaders in the three model were compared in the pre and post-intervention showing significantly different variables such as sex (p < 0.01 and p < 0.05), religion (p < 0.00, p < 0.00), occupa- tion (p < 0.00, p < 0.00), and community status as com- munity committee (p < 0.05 and p < 0.05) (no present table). 5.2.1.2. Dengue Community Capacity Level of the Leader Group in Three Models Table 1 shows various levels of dengue community capacity of leaders in Ban Mon (n:24), Ban Nangpraya (n:24), and Ban Kang communities (n:28) focusing on pre and post-intervention results which were signifi- cantly different (p < 0.05). In the pre-intervention, the total community capacity level of Ban Mon, Ban Nang- praya, and Ban Kang communities were high ( , SD: 351, 15), moderate ( , SD: 297,16), and high ( , SD: 352,15) respectively. The post-intervention results show that Ban Mon, Ban Nangpraya, and Ban Kang model were high ( , SD: 389, 11), high ( , SD: 357,10), and high ( , SD: 406,12) as follows. For the Ban Mon model, the dengue community ca- pacity level of 14 domains of leader the group were at the high level (5-domains), at the moderate level (8- domains), and low level (1-domain as Religious leader capacity domain) in the pre-intervention. Pos-interven- tion’s results showed increase scores of all domains with a high level (10-domains), and moderate level (4-do- mains). There were significant differences of increased scores in two domains, namely, in the Community lead- ership domain (p < 0.05) and in Dengue working group domain (p < 0.05). Most domains of Ban Nangpraya model in the pre-intervention were at moderate levels (9-domains), high level (3-domains), low level (1-domain—Dengue working group domain), and very low (1-domain—Re- ligious leader capacity domain). The increased scores on the post-intervention showed high level (8-domains), moderate level (5-domains), low level (1-domain—Reli- gious leader capacity domain). There were significant differences with increased scores in nine domains (p < 0.05) and continuing activities (p < 0.01). In the last community, Ban Kang model’s scored at mostly at moderate levels (10-domains), high level (4-domains) in the pre-test, but on the post-test, most domains were at the high level (13-domians) which showed significantly increased scores in seven domains (p < 0.01), and a moderate level in only one domain— Resource mobilization domain (p < 0.05). Among the three models, pre-intervention’s scores were signifi- cantly different in total (p < 0.01) and in five domains such as Critical situation management domain (p < 0.01), Needs assessment domain (p < 0.01), Communication of dengue information domain (p < 0.01), Community lead- ership domain (p < 0.05), and Religious leader capacity domain (p < 0.001). In the post-intervention, the Critical situation management domain and Religious leader ca- pacity domain were significantly different among the communities (p < 0.01), and three domains were sig- nificantly different (p < 0.05) such as Leader group net- working domain, Communication of dengue information domain, and Leader group and community network. See Table 1 for community capacity level of leaders in be- fore and after intervention. 5.2.1.3. Multiple Comparison of Dengue Commu nity Capacity of the Leader Group Pre and Post Intervention a mong Three Models The community capacity levels of the leaders in Ban Mon, Ban Nangpraya, and Ban Kang model were found  C. Suwanbamrung et al. / Health 3 (2011) 58 4-601 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 594 Table 1. Comparison dengue community capacity levels of leaders between pre and post intervention in Ban Mon, Ban Nangphaya, and Ban Kang model. Dengue community capacity level Ban Mon (n:26) Ban Nangpraya (n:24) Ban Kang (n:26) (Kruskal-Wallis Test, p) Dengue community capacity domains of the leaders group Pre Post ( SD)) Pre ( (SD)) Post Pre ( (SD)) Post ( (SD)) Pre (SD))(SD))( (Post 29(1)4 L1: Critical situation management 32(1)4 24(1)3 28(1)4* 28(1)4 34(1)4** 0.004** 0.009** L2: Personal leadership 39(1)4 43(1)4 38(1)4 40(1)4 40(1)4 44.624 0.496 0.111 L3: Health care provider capacity 28(1)4 30 (1)4 25(1)4 29(1)4 27(1)4 30(1)4* 0.279 0.201 L4: Needs assessment 24(1)3 26(1)4 17(2)3 24(0.9)323(1)3 27(1)4 0.009** 0.084 L5: Sense of community 42(1)4 41(1)4 39(2)4 43(1)4 38(1)4 43(0.9)4** 0.150 0.823 L6: Leader group networking 31(2)3 35(1)3 27(2)3 32(1)3* 33(2)3 37(1)4 0.051 0.049* L7: Communication of dengue information 28(1)3 32(1)3 21(1)3 26(1)3* 27(1)3 31(1)4 0.004** 0.019* L8: Community leadership 25(1)4 27(0.8)4* 21(1)3 26(1)4* 24(1)3 28(0.9)4** 0.038* 0.290 L9: Religious leader capacity 17(2)2 24(2)3 8(2)1 15(2)2* 24(1)3 28(1)4* 0.000***0.002** L10: Leader group and Community networking 20(1)3 23(1)4 18(1)3 22(0.9)421(1)3 25(1)4** 0.237 0.049* L11: Resource mobilization 10(0.7)311( 0 .6)310(0.7)312(0.5)3* 10(0.7)312(0.7)3* 0.910 0.816 L12: Dengue working group 15(1)3 20(0.7)4* 12(1)2 17(0.8)3* 15(0.9)319(0.8)4** 0.163 0.078 L13: Community leader participation 18(1)3 20(0.8)416(1)3 20(0.6)4* 18(1)3 19(0.7)4 0.481 0.825 L14: Continuing activities 18(1)3 20(0.7)416(0.9)319(0.6)4** 18(1)3 21(0.8)4** 0.066 0.129 Total 351(15)4389(11)4** 297(16)3357(10)4**352(15)4406(12)4** 0.005** 0.018* Remake: Level of community capacity as 1very low; 2low; 3moderate; 4 high; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. to be significantly different. The total of dengue com- munity capacity levels in the pre-intervention showed a significant difference between Ban Mon and Ban Nang- praya (p < 0.05) and Ban Nangpraya and Ban Kang (p < 0.01), and in the post-test there was a significant differ- ence between Ban Nangpraya, and Ban Kang (p < 0.05). In the multiple comparison test, Ban Mon and Ban Nangpraya showed significant differences in the com- munity capacity domain before the intervention in five domains—Critical situation management (p < 0.01), Needs assessment (p < 0.01), Communication of dengue information (p < 0.01), Community leadership (p < 0.01), and Religious leader capacity (p < 0.05), but after the post-test, the only significant difference was in Critical situation management domain (p < 0.01). Ban Mon and Ban Kang models showed significant difference in the community capacity domain during the pre-test only in Religious leader capacity domain (p < 0.05). Multiple comparisons between Ban Nangpraya and Ban Kang models showed significant differences in the community capacity domain in the pre-intervention in three domains, namely, Critical situation management domain (p < 0.01), Needs assessment domain (p < 0.01), Religious leader capacity domain (p < 0.01), but the post-intervention showed five domains with significant differences—Criti- cal situation management domain (p < 0.01), Leader group networking domain (p < 0.05), Communication of dengue information (p < 0.05), Religious leader capacity domain (p < 0.01), Leader group and community net- working domain (p < 0.05) (see Table 2). 5.2.2. Dengue Community Capacity Level of the Non-Leader Grou p 5.2.2.1. Characteristics of the Non-Leader Group Table 4 describes the characteristics of the non-leader group in the pre and post-intervention in the three com- munities, Ban Mon, Ban Nangpraya, and Ban Kang models were 200, 215, and 176 respectively. A large majority of participants in the Ban Mon, Ban Nangpraya, and Ban Kang model in the pre and post-intervention were female, (pre- 69%, 64%, and 50%: post- 73%, 64% and 58%), Buddhist (pre- 99%, 99% and 71%; post- 100%, 99% and 72%), married (pre- 76%, 66% and 70%; Openly accessible at  C. Suwanbamrung et al. / Health 3 (2011) 58 4-601 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 595595 Tab le 2 . Multiple comparison of differences of dengue community capacity of the leader group in pre and post-intervention among three models. Multiple comparison of differences of models (Mann-Whitney Test) Ban Mon (n:28) and Ban Nangpraya (n:24) Ban Mon (n:28) and Ban Kang (n:26) Ban Nangpraya (n:24) and Ban Kang (n:26) Dengue community capacity of the leader group Pre Post Pre Post Pre Post L1: Critical situation Management 0.002** 0.033* 0.013* 0.003** L4: Needs assessment 0.005** 0.012* L6: Leader group networking 0.013* L7: Communication of dengue information 0.004** 0.022* L8: Community leadership 0.018* L9: Religious leader capacity 0.004** 0.018* 0.000** 0.001** L10: Leader group and community networking 0.022* Total 0.016* 0.001** 0.005** Remake: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. post- 72%, 65% and 71%), basic elementary education (pre- 55%, 44% and 49%; post- 49%, 42% and 56%). The most common occupation in Ban Mon and Ban Nangpraya model were unskilled labor (pre- 41% and 49%; post- 32% and 41%), Ban Kang model was farm- ing (pre- 46%; post- 52%). Receiving dengue knowledge in past 12 months showed an increase in the post-inter- vention (16%, 14% and 17%) from pre-intervention (50%, 14%, and 89%). Having experienced dengue, the pre-intervention was lower than post-intervention (pre- 14%, 23% and 34%; post- 61%, 79% and 89%). The characteristics of the non-leader group of pre and post-intervention in each community were not signifi- cantly different. The mean of age, length of time resid- ing in the community, and dengue education in the past 12 months were not significantly different between the mean scores in pre-post intervention and among the three models. However, the mean of family monthly income was significantly different (p < 0.05): Ban Kang was higher than others model. The characteristics of the variables of the non-leader group in three models were compared in the pre and post-intervention showing sig- nificant difference in some variables such as sex (p < 0.01 and p < 0.05), religion (p < 0.001, p < 0.001), oc- cupation (p < 0.001, p < 0.001), and community status as community committee members (p < 0.05 and p < 0.05) (no present table). 5.2.2.2. Dengue Community Capacity Level of the Non-Leade r Group in Models Table 3 shows various levels of community capacity of leaders in Ban Mon (n: 200), Ban Nangpraya (n: 215), and Ban Kang communities (n: 176) focusing on pre-test and post-test results which were significantly different (p < 0.05). In the pre-test, the total community capacity level of non-leaders in Ban Mon, Ban Nangpraya, and Ban Kang communities were at a moderate level ( , SD: 247, 72; 196, 70, and 242, 35). On the post-test, Ban Mon and Ban Kang communi- ties were at a high level ( , SD: 263, 52; 290, 54), and Ban Nangpraya community was at a moderate level ( , SD: 218, 62) as follows. On the pre and post-interven- tion, all three models were significantly different at various community capacity levels (p < 0.001). For Ban Mon model, the dengue community capacity levels of 11 domains for the non-leader group were at a high level (6-domains), at a moderate level (4-domains), and at a low level (1-domain—Religious leader capacity domain) in the pre-intervention. The post-intervention showed increased scores in all domains—a high level (7-domains), a moderate level (4-domains). There was a significant difference of increased scores in six domains—five do- mains were different (p < 0.05) and one other domain was different (p < 0.01). The Ban Nangpraya model showed moderate levels in 7-domains, a high level in 1-domain, and low levels in 3-domains (Religious leader capacity, Communication of dengue Information, Den- gue working group). Most domains increased their scores in the post-test showing high levels in 3-domains, moderate levels in 6-domains, low levels in 2-domains in (Religious leader capacity domain and Communica- tion of dengue information). There were a significant difference of increased scores in nine domains; four do- mains (p < 0.01) and five domains (p < 0.05). In the last model, the Ban Kang, most domains were at a moderate level (8-domains), and at a high level in  C. Suwanbamrung et al. / Health 3 (2011) 58 4-601 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 596 Table 3. Comparison pre and post-intervention of community capacity levels of non-leader in Ban Mon, Ban Nangphaya, and Ban Kang. Model Ban Mon (n:200) Ban Nangpraya (n:215)Ban Kang (n:176) ANOVA Dengue community capacity domain of the non-leader group Pre ( (SD)) Post ( (SD)) Pre ( (SD)) Post ( (SD)) Pre ( (SD)) Post ( (SD)) Pre (p) Post (p) NL1: Critical situation management 38(13)3 42(8)4*** 32(12)3 35(11)3** 39(6)3 45(9)4*** 0.000*** 0.000*** NL2: Personal leadership 25(7)4 27(6)4* 19(8)3 22(6)3** 23(4)3 28(5)4*** 0.000*** 0.000*** NL3: Religious leader capacity 19(13)2 22(11)3* 11(12)2 14(13)2* 22(8)3 31(9)4*** 0.000*** 0.000*** NL4: Community leadership 25(8)4 26(5)4* 19(8)3 21(7)3 24(5)3 28(5)4*** 0.000*** 0.000*** NL5: Health care provider capacity 21(6)4 22(4)4* 18(6)3 19(5)5 21(4)4 23(4)4*** 0.000*** 0.000*** NL6: Sense of community 30(6)4 30(5)4 29(5)4 29(6)4* 27(5)4 31(4)4*** 0.000*** 0.000*** NL7: Communication of dengue Information 19(8)3 20(6)3 12(9)2 14(8)2* 16(5)3 21(7)3*** 0.000*** 0.000*** NL8: Continuing activities 18(6)3 19(4)4 15(6)3 17(5)3* 18(3)3 21(4)4*** 0.000*** 0.000*** NL9: Dengue working group 20(8)3 21(6)3 14(8)2 17(7)3** 19(4)3 24(6)4*** 0.000*** 0.000*** NL10: Resources mobilization 19(5)4 15(3)3* 13(4)3 14(4)3* 15(3)3 16(4)4** 0.000*** 0.000*** NL11: Needs assessment 14(6)4 15(4)4 11(6)3 13(5)4** 14(3)4 17(5)4*** 0.000*** 0.000*** Total 247(72)3 263(52)4** 196(70)3218(62)** 242(35)3290(54)4*** 0.000*** 0.000*** Remake: Level of community capacity as 1very low; 2low; 3moderate; 4high; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. 3-domains in pre-test, but almost all domains achieved a high level (10-domian) and 1 a moderate level (Resource mobilization domain) in the post-test. Between the pre- test and post-test, there were significant differences in all 11 domains with 10 domains showing significant differ- ences in increased scores in seven domains (p < 0.001) and a slight increase in only one domain (Resources mo- bilization domain) (p < 0.01). Among these three models, the pre-intervention’s scores were significantly different in total (p < 0.001) and all 11 domains as same as post- intervention (p < 0.001). 5.2.2.3. Multiple Comparisons for Significant Differences of the Dengue Community Capacity Level of the Non-Leader Grou p Multiple comparisons for significant differences of community capacity scores were testing the difference scores among three models when protested and post- tested for building community capacity. Ban Mon (n:200) and Ban Nangpraya (n:215) showed significantly differ- ent capacities in the various domains. In the pre- inter- vention, there were 8 domains (p < 0.001) and in the post-intervention, 10 domains (9 domains, p < 0.001; Resources mobilization domains, (p < 0.01). Ban Mon (n:200) and Ban Kang Model (n:176) also were signifi- cantly different in their stronger domains. In the pre- intervention, there were five domains (Religious leader capacity domain and Resources mobilization domain, p < 0.05; Personal leadership and Communication of dengue information domains, p < 0.01; Religious leader capacity domain, p < 0.001) and in the post-intervention, eight domains varied—(four domains, p < 0.01; four domains, p < 0.05). Ban Nangpraya (n:215) and Ban Kang (n:176) were not significantly different with scores only in the Personal leadership domain in the pre-test, but all do- mains in post-test were significantly different (p < 0.001). In summary, the community capacity of non-leader domains in the three model were significantly different when contrasting Ban Mon (n:200) and Ban Nangpraya (n:215), Ban Mon (n:200) and Ban Kang (n:176), and Ban Nangpraya (n:215) and Ban Kang (n:176) (see Ta- ble 4). 5.3. Dengue Entomological Index 5.3.1. Larval Index Larval surveys were conducted to determine types of containers and larval indices. The total households in pre-test (October, 2009) and post-test (October, 2010) of  C. Suwanbamrung et al. / Health 3 (2011) 58 4-601 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 597597 Ban Mon, Ban Nangpraya, and Ban Kang communities involved 230, 145, and 139 households as follows. Total number of water containers inspected in pre and post-intervention of Ban Mon model were 2597 and 1173, then BI, HI, and CI of post-intervention decreased from 303, 51, and 24 to 130, 45, and 22 respectively. Ban Nangpraya total number of water containers num- bered 2800 pieces in the pre-intervention and 1720 pieces in the post-intervention. The BI, HI, and CI in the pre-intervention were 350, 55, and 31 and decreased to 140, 44, and 12 in the post-intervention. The results (BI, HI, CI) in Ban Kang model showed 358, 63, and 25 in the pre-intervention and 65, 31, and 5 in the post-inter- vention. Of special interest, HI of the three models was an important index which aimed to reach less than 10%. The comparison between the pre and post intervention of Ban Mon model showed a decrease of HI 12%, at Ban Nangpraya model 17% and at Ban Kang model 51% (see Table 5). 5.3.2. Type of Water Container Inspected Total larval survey of seven types of water containers observed during the pre-test (October, 2009) and post- test (October, 2010) in Ban Mon, Ban Nangpraya, and Ban Kang were 2014, 2800, and 2014 pieces, and 1173, 1720, and 1822 pieces respectively. These three communities showed a very high percent- age of positive containers being discarded surrounding the houses in both the pre-test and post-test—37% ,82%; and 62% in the pre-test and 21%; and 48% and 14%. In the post-test However, the number of water containers inspected in the post-test decreased from the pre-test in each community: Ban Mon 12%, Ban Nangpraya 17%, and Ban Kang 80% (see Table 6). Table 4. Multiple comparisons among three models showing the dengue community capacity level of the non-leader group in pre and post-intervention. Multiple comparisons among communities Ban Mon (n:200) and Ban Nangpraya (n:215) Ban Mon (n:200) and Ban Kang (n:176) Ban Nangpraya (n:215) Ban Kang (n:176) Community capacity of non-leaders Pre Post Pre Post Pre Post NL1: Critical situation management 0.000*** 0.000*** 0.001** 0.000*** 0.000*** NL2: Personal leadership 0.000*** 0.000*** 0.008** 0.000*** NL3: Religious leader capacity 0.000*** 0.000*** 0.042* 0.000*** 0.000*** 0.000*** NL4: Community leadership 0.000*** 0.000*** 0.007** 0.000*** 0.000*** NL5: Health care provider Capacity 0.000*** 0.000*** 0.000*** 0.000*** NL6: Sense of community 0.000*** 0.002** 0.002** 0.000*** NL7: Communication of dengue Information 0.000*** 0.000*** 0.004** 0.000*** 0.000*** NL8: Continuing activities 0.000*** 0.000*** 0.001** 0.000*** 0.000*** NL9: Dengue working group 0.000*** 0.000*** 0.000*** 0.000*** 0.000*** NL10: Resources mobilization 0.006** 0.012* 0.000*** 0.000*** 0.000*** NL11: Needs assessment 0.000*** 0.000*** 0.000*** 0.000*** 0.000*** Total 0.000*** 0.000*** 0.000*** 0.000*** 0.000*** Remake: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Table 5. Comparison of larval index (BI, HI, CI) pre and post-intervention at Ban Mon, Ban Nongpraya, and Ban Kang model. Ban Mon model (Number of households: 230) Ban Nangpraya Model (Number of households: 145) Ban Kang Model (Number of households: 139) Larval Indices Pre Post Pre Post Pre Post BI (<50) 303 130 350 140 358 65 HI (<10) 51 45 55 44 63 31 CI (<1) 24 22 31 12 25 5 Percentage of decrease HI 12% 17% 51%  C. Suwanbamrung et al. / Health 3 (2011) 58 4-601 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 598 Table 6. Type of containers inspected, positive containers with larval and percentage. Ban Mon model Number of containers inspected: Positive larval (Percentage) (n:n,(%)) Ban Nangpraya model Number of containers inspected: Positive larval (Percentage) (n:n,(%)) Ban Kang model Number of containers inspected: Positive larval (Percentage) (n:n,(%)) Types of water containers Before (n:n,(%)) Before (n:n,(%))Before (n:n,(%))Before (n:n,(%))Before (n:n,(%)) Before (n:n,(%)) 1) Drinking water 513:103(19) 253:33(12) 860:192(22) 608:92(15) 282:13(5) 242:1(0) 2) Water containers in bathroom and toilet 378:94(25) 213:57(27) 241:74(31) 187:14(7) 239:5(2) 270:8(3) 3) Potable water containers 416:96(23) 199:41(21) 409:100(24) 323:24(7) 247:18(7) 313:10(3) 4) Vases 362:112(31) 264:56(21) 246:79(32) 142:9(6) 297:48(16) 321:12(4) 5) Cupboard saucers 147:23(16) 69:5(7) 145:64(44) 78:10(12) 110:30(27) 103:3(3) 6) Plants-related containers 318:57(18) 120:34(28) 475:95(20) 152:8(5) 338:142(42) 243:10(4) 7) Discarded containers surrounding household 345:129(37) 45:37(82) 424:264(62) 219:46(21) 501:241(48) 330:47(14) Total 2497:614(25) 1173:263(22) 2800:868(31) 1720:203(11) 2014:497(24) 1822:91(5) Percentage of containers inspected decreased 12% 17% 80% 5.4. Dengue Epidemiological Index The epidemiological index in this study consisted of the morbidity and mortality rates. The morbidity rate of dengue from 2007, 2008, 2009, and October, 2009 to October, 2010 in Ban Mon, Ban Nangpraya, and Ban Kang models showed alternative change from the stan- dard level (<50 cases/100,000 populations). For Ban Mon, the population in the middle of the year was 1485; one year before conducting intervention mor- bidity rate was 67 cases/100,000 populations. When the dengue program (November, 2010) was just concluded, the morbidity rate was 202 case/100,000 populations. In total, there were three cases of dengue illness; one stayed in the community and 2 cases of dengue illness stayed outside the community. Ban Nangpraya community, with a population of 1695 persons in middle year showed a morbidity rate of the community every year of one or two cases. When the program finished, the community showed 2 cases of dengue illness resulting in a morbidity rate of 118 case/ 100,000 populations. Ban Kang community’s population was 1650 persons in the middle of the year. In the past three years, the community had a high morbidity rate; 61, 182, 61 cases/ 100,000 population. At the time of conducting and fin- ishing the program, there was no morbidity rate. None of the models showed an increased mortality rate after conducting the program. Moreover, Ban Kang model had no incidence of dengue whereas other vil- lages in the sub-district had incidences of dengue illness (see Table 7). 6. DISCUSSION Efforts of control dengue prevention and control have been redirected from central Thai Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) to local administrative organization (LAO) using all the leader and non-leader group because the problem of dengue is a community problem needing to be solved by the community [15,20]. The community capacity building process was a different strategy ap- plied in these three communities. A principle researcher, the leader group, and the support team were discussion appropriate techniques and methods of analysis of the dengue problem and how to resolve it in each commu- nity for 13 months (October, 2009-October, 2010). However, the sustainability needs the long-term com- munity-based maintenance of the health program [32]. This study demonstrates positive results because it de- fined the sustainability of community-based dengue so- lution as the successful outcome of community capacity building for dengue prevention and control, and is measured by: 1) the increasing level of community ca- pacity domains; 2) the decreasing of entomology index as larval indices; the Breteau Index (BI), House Index (HI), and Container Index (CI); and 3) the decreasing epidemiological index for the morbidity rate and mortal- ity rate of dengue [7-10]. After one year of applying the dengue community ca- pacity building model in these three models, the com- munity capacity building process for a sustainable solu- tion to dengue has shown varying differences according to the context of that community. Results show an in- crease in the community capacity level, a decrease in the  C. Suwanbamrung et al. / Health 3 (2011) 58 4-601 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 599599 Table 7. Morbidity and mortality rate of dengue in three models among 3 years in pre and post-intervention of community capacity building. Number (case): Morbidity rate (case)/100,000 population): Morbidity rate (percentage) Pre-intervention of building community capacity Post-intervention building community capacity Model Year; 2007 Year; 2008 Year; 2009 Year; 2010 Ban Mon (n:1485) 0:0:0 0:0:0 1:67:0 3:202:0 Ban Nangpraya (n:1695) 2:118:0 1:59:0 0:0:0 2:118:0 Ban Kang (n:1650) 1:61:0 3:182:0 1:61:0 0:0:0 Resources: The primary health center in each model. entomological index, and a low morbidity rate has dem- onstrated to varying degrees, together with other sugges- tions from the communities that building capacity can influence community health, the sustainability of com- munity initiatives and community abilities to respond to emerging health issues [18,33]. The basic strategies for prevention and control of dengue of these three models have given rise to carrying out activities as a dengue community network. The den- gue network held seven activities, namely, 1) meeting to prepare plans of intervention, 2) chemical fogging train- ing to control dengue morbidity in community, 3) herb training to create a citronellas bank, 4) development of a Gambia fish bank, 5) communication through commu- nity radio disseminating dengue knowledge, 6) larval indices survey every month, and 7) leadership training and holding an evaluation meeting. Local or specific strategies of each model were planned in detail and im- plemented through activities according to the context of community. Ban Mon model showed the highlight of activity as Gambia fish bank at the temple in their com- munity because the religious leadership capacity level in the pre-intervention was low so the intervention of the community focused on built religious leadership capac- ity. Ban Nangpraya model, as seaside community, the highlight activities were red lime to use in water con- tainers because the community hade many water con- tainers per household. Ban Kang model, as a rubber and fruits garden community, strengthened mobile meeting of leader group in each area of the community, mass communication from religious leaders and community leaders, and door to door surveys of larval index once a month. The results of the study show activities following the concept of sustainable dengue solutions as a commu- nity-based process creates a new paradigm of dengue epidemiology, and vector-control services. This commu- nity-based approach underlines the need for operational standards for measurement, delivery of a combination of interventions as central and local strategies, and con- tinuing monitoring and evaluation process and outcome [34]. The outcomes of searching for a sustainable solu- tion to the problem of dengue generated increased the dengue community capacity levels of community leader group (14-domains) and non-leader group (11-domains), constant monitoring of larval indices, and improved morbidity and mortality rates. In each model, pre and post-interventions of dengue community building increased the dengue community’s capacity level of the leader group a seen in all domains and the total level likewise increased in the post-inter- vention evaluations of all three models. Nevertheless, significant differences showed in the increases in almost all domains in the Ban Nangpraya and the Ban Kang model. The relation of the comparisons when analyzed in the pre-intervention evaluations of the dengue com- munity capacity levels of the leaders group among the three models showed significantly different increases in five domains: Critical situation management, Needs as- sessment, Communication of dengue information, Com- munity leadership, and Religious leadership. Post the intervention, the leader group networking domain, and the leader group and community networking domain showed increases significantly different from the pre- intervention (p < 0.05), but Critical situation manage- ment, and Religious leader capacity were significantly different (p < 0.01). The community capacity levels of the non-leader groups in all domains and in total in the post intervention showed increased scores from pre- intervention. All domains of Ban Kang community and almost all domains of Ban Nangpraya community showed a significant difference in their increase, but the other community in only half of all domains. Among these three communities, all domains and totals indicated significantly different capacities. The difference of do- mains showed commitment of the leader group for building capacity within the leaders and supporting team in two strengthened communities, whereas the other community conducted activities only by their VHVs group. The results were indicated in a previous study  C. Suwanbamrung et al. / Health 3 (2011) 58 4-601 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 600 which focused on the important roles of the leader group in the community [5,35,36]. Entomology and epidemiology outcomes of these three models showed different scores all indicating de- creases of both larval indices and morbidity rate. Ban Kang model exhibited excellent model of dengue com- munity capacity through their process—preparation, plan- ning, implement and continual monitoring. The leader group in the model was involved in intersectoral coordi- nation between the representatives from local adminis- trative organization, primary health care center, commu- nity leaders, religious leaders, committee leaders, and VHVs. Then, it was clearly seen that the results of the dengue community capacity of leader and non-leader group in the community supported the premise and ap- proach of the dengue capacity of community to decrease dengue risk. Moreover, the larval indices (HI, BI, and CI) and morbidity rates were shown to be the lowest level of three models [37-40]. The model with highest the dengue community capac- ity level showed the lowest risk of dengue utilizing the index of both larval indices and morbidity rate. Thus, the model of community capacity building for sustainable dengue problem solutions needs to be maintained and increased the level of the dengue community capacity within the context of each community. 7. LIMITATION One limitation of the study is that it was conducted over one year. Longer term periods are needed to assess sustainability [32]. Nevertheless, the study assessed the outputs and outcomes of intervention at an early stage in achieving sustainability of a solution to dengue [5,41]. Another limitation was the adoption of the HI, BI, and CI as they were easier to collect and to interpret than other entomological measures, and that the leader group perceived ownership of own community and provided available participation. The advantage of a community capacity building approach is that it demonstrated a high degree in the ability of community capacity levels of both leaders and non-leaders to change since after one year of intervention, the reduction in all larval indices, and type of water containers could be found. 8. CONFLICT OF INTEREST The author(s) declare that they have no competing in- terests. 9. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Grateful acknowledgements are to people (leaders and non-leaders) of three communities and all representatives from government officers who were involved in the project. The author(s) would like to thank Walailak University, Thailand for funding the project and the School of Nursing for the support by providing available time. Special thanks to Victor Greenspoon who has edited the manuscript. REFERENCES [1] Promprou, S., Jaroensutasinee, M. and Jaroensutasinee, K. (2005) Climatic factors affecting dengue heamor- rhagic fever incidence in southern Thailand. Dengue Bulletin, 29, 41-48. [2] Lcung, M.W., Yen, I.H. and Minkler, M. (2004) Com- munity-based participatory research: A promising ap- proach for increasing epidemiology's relevance in the 21st century. International Journal of Epidemiology, 33, 499-506. doi:10.1093/ije/dyh010 [3] Guha-Sapir, D. and Schimmer, B. (2005) Dengue fever: New paradigms for a changing epidemiology. Emerging Themes in Epidemiology, 2, 1. doi:10.1186/1742-7622-2-1 [4] Heintze, C., Garrido, M.V. and Kroeger, A. (2007) What do community-based dengue control programmes achieve? A systematic review of published evaluations. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 101, 317-325. doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2006.08.007 [5] Toledo, M.E., Vanlerberghe, V., Perez, D., Lefevre, P., Ceballos, E., Bandera, D., et al. (2007) Achieving sus- tainability of community-based dengue control in Santi- ago de Cuba. Social Science & Medicine, 64, 976-988. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.10.033 [6] Better Health Center (2001) A framework for building capacity to improve health. Better Health Center-Publi- cations Warehouse, North Ryde. [7] Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) (2003) 44th Directing council, 55th session of the regional committee. Washington DC, 22-26 September 2003. http://www.paho.org/english/gov/cd/cd44-28-e.pdf [8] World Health Organization (1999) Prevention and con- trol of dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever: Compre- hensive guidelines. WHO Regional Publication, New Delhi, SEARO No. 29. [9] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2003) Epidemic/Epizootic west Nile virus in the United States: Guidelines for surveillance, prevention, and control. CDC, Colorado. http://wildpro.twycrosszoo.org/S/00Ref/MiscellaneousC ontents/d67.htm [10] Spark, R. (2003) Dengue fever management plan for North Queensland 2000-2005. Queensland government, Queensland. [11] Laverack, G. (2001) An identification and interpretation of the organizational aspects of community empower- ment. Community Development Journal, 36, 134-145. doi:10.1093/cdj/36.2.134 [12] Labonte, R. and Laverack, G. (2001) Capacity building in health promotion, part 2; whose use? And with what measurement? Critical Public Health, 11, 129-139. doi:10.1080/09581590110039847 [13] Laverack, G. (2003) Building capable communities: Ex- periences in a rural Fijian context. Health Promotion In- ternational, 18, 99-106. doi:10.1093/heapro/18.2.99  C. Suwanbamrung et al. / Health 3 (2011) 58 4-601 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 601601 [14] Norton, B.L., McKeroy, K.R., Burdine, J.N., Felix, M.R.J. and Dorsey, A.M. (2002) Community capacity: Concept, theory, and methods. Jossey-Bass Wiley, San Francisco. [15] Suwanbamrung, C., Nukan, N., Sripon, S., Somrong- thong, R. and Singchagchai, P. (2010) Community ca- pacity for sustainable community-based dengue preven- tion and control: Study of a sub-district in Southern Thailand. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine, 3, 1-5. [16] Suwanbamrung, C., Somrongthong, R., Singchanchai, P. and Srigernyuang, L. (2008) The development of a tool to assess community capacity of sustainable community- based dengue prevention and control: A study in South- ern Thailand. PhD Thesis, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok. [17] Laverack, G. (2006) Evaluating community capacity: Visual representation and interpretation. Community De- velopment Journal , 41, 266-276. doi:10.1093/cdj/bsi047 [18] Smith, N., Littlejohns, L.B. and Roy, D. (2003) Meas- urement community capacity: State the field review and recommendations for future research. David Thrompson Health Region, Red Deer. [19] Gibbon, M., Labonte, R. and Laverack, G. (2002) Evaluation community capacity. Health and Social Care in the Community, 10, 485-491. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2524.2002.00388.x [20] Suwanbamrung, C. (2010) Community capacity for sus- tainable community-based dengue prevention and control: Domain, assessment tool, capacity building model. Asia Pacific Journal Tropical Medicine, 3, 499-504. doi:10.1016/S1995-7645(10)60121-6 [21] Nguyen, M.-N., Gauvin, L., Martineau, I. and Grignon, R. (2005) Sustainability of the impact a public health inter- vention: Lessons learned from the Laval walking clubs experience. Health Promotion Practice, 6, 44-52. doi:10.1177/1524839903260144 [22] Bopp, M. and Bopp, J. (2002) Welcome to de Swamp: Why assessing community capacity is fundamental to transformational work. In: Smith, N., Littlejohns, L.B. and Roy, D., Ed., Measurement Community Capacity: State the Field Review and Recommendations for Future Research, Community-Level Indicators: Building Com- munity Capacity for Health Conference, David Thromp- son Health Region, Red Deer. [23] Laverack, G. and Wallerstein, N. (2001) Measuring com- munity empowerment: A fresh look at organizational domains. Health Promotion International, 16, 179-185. doi:10.1093/heapro/16.2.179 [24] Suwanbamrung, C., Somrongthong, R., Singchagchai, P. and Srigernyaung, L. (2009) Application of a dengue community capacity-assessment tool (Dccat) for sus- tainable community-based dengue prevention and control. In: Boonmongkon, P. and Samakekarom, R., Eds., The 1st Annual International Graduate Research Conference on Social Sciences and Humanities Theme “Harmony in Diversity” Between April 2-3, 2009, Bangkok, 204. [25] Wongkoon, S., Jaroensutasinee, M. and Jaroensutasinee, K. (2005) Larval infestation of Ades aegypti and Ades albopictus in Nakhon Si Thammarat, Thailand. Dengue Bulletin, 29, 169-175. [26] Flick, U., Von Lardorff, E. and Steinke I. (2004) A com- panion to qualitative research. Sage Publications, Lon- don. [27] Burns, N. and Grove, S. (2001) Practical of nursing re- search: Concept, critique and utilities. W. B. Saunders, Philadelphia. [28] DeVellis, R.F. (2003) Scale development: Theory and applications. Sage Publications, Thousand. [29] Streiner, D.L. and Norman, G.R. (2005) Health meas- urement scale: A practical guide to their development and use. Oxford University Press, New York. [30] Focks, D.A. (2004) A review of entomological sampling methods and indicates for dengue vectors. WHO, Ge- neva. [31] World Health Organization (1933) Monograph on den- gue/dengue haemorrhagic fever. Regional Office for South-East Asia, New Delhi. [32] Shediac-Rizkallah, M.C. and Bone, L.R. (1998) Planning for the sustainability of community-based health pro- grams: Conceptual frameworks and future directions for research, practice and policy. Health Education Research, 13, 87-108. doi:10.1093/her/13.1.87 [33] Hawe, P., King, L., Noort, M., Jorden, C. and Loyd, B. (2000) Indicators to help with capacity building in health promotion. New South Wales Health Department, North Sydney. [34] Horstick, O., Runge-Ranziger, S., Nathan, M.B. and Kroeger, A. (2010) Dengue vector-control services: How do they work? A systematic literature review and country case studies. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropi- cal Medicine and Hygiene, 104, 379-386. doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2009.07.027 [35] Gubler, D.J. and Clark, G.G. (1994) Community-based integrated control of Aedes aegypti: A brief overview of current programs. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 50, 50-60. [36] Gubler, D.J. and Clark, G.G. (1996) Community in- volvement in the control of Aedes aegypti. Acta Tropica, 61, 169-179. doi:10.1016/0001-706X(95)00103-L [37] Sanchez, L., Perez, D., Perez, T., Sosa, T., Kouri, G., Boelaert, M., et al. (2005) Intersectoral coordination in Aedes aegypti control. A pilot project in Havana City, Cuba. Tropical Medicine and International Health, 10, 82-91. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01347.x [38] Ungchusak, K. (2006) Epidemiology of dengue in Thai- land. Bureau of Epidemiology, Department of Disease Control, Bangkok. [39] Phuanukoonnon, S., Brough, M. and Bryan, J.H. (2006) Folk knowledge about dengue mosquitoes and contribu- tions of health belief model in dengue control promotion in Northeast Thailand. Acta Tropica, 99, 6-14. doi:10.1016/j.actatropica.2006.05.012 [40] Phuanukoonnon, S., Mueller, I. and Bryan, J.H. (2005) Effective of dengue control practices in household water containers in Northeast Thailand. Tropical Medicine and International Health, 10, 755-763. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01452.x [41] Rifkin, S.B., Muller, F. and Bichmann, W. (1988) Pri- mary health care: On measuring participation. Social Sciences & Medicine, 26, 931-940. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(88)90413-3