Paper Menu >>

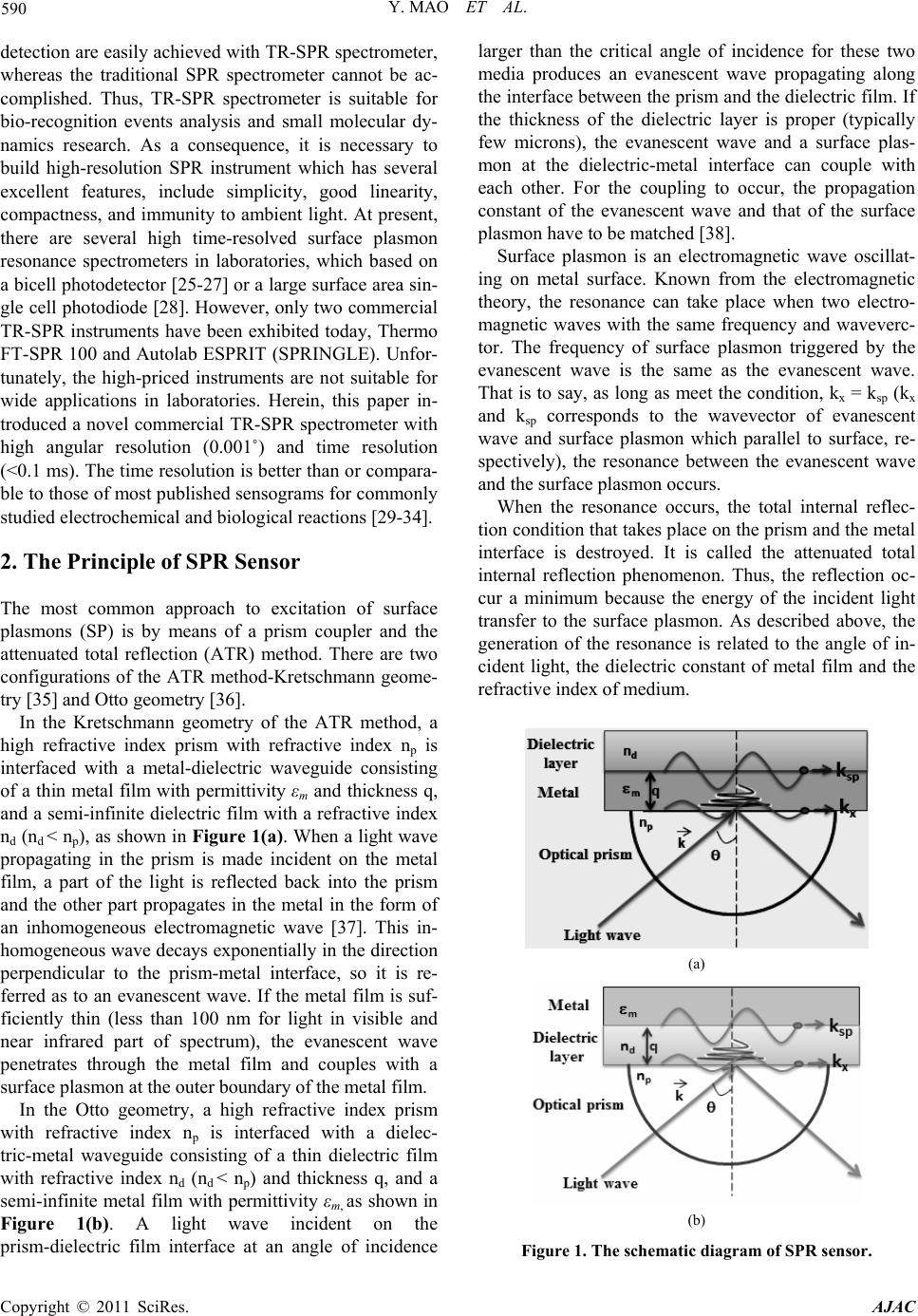

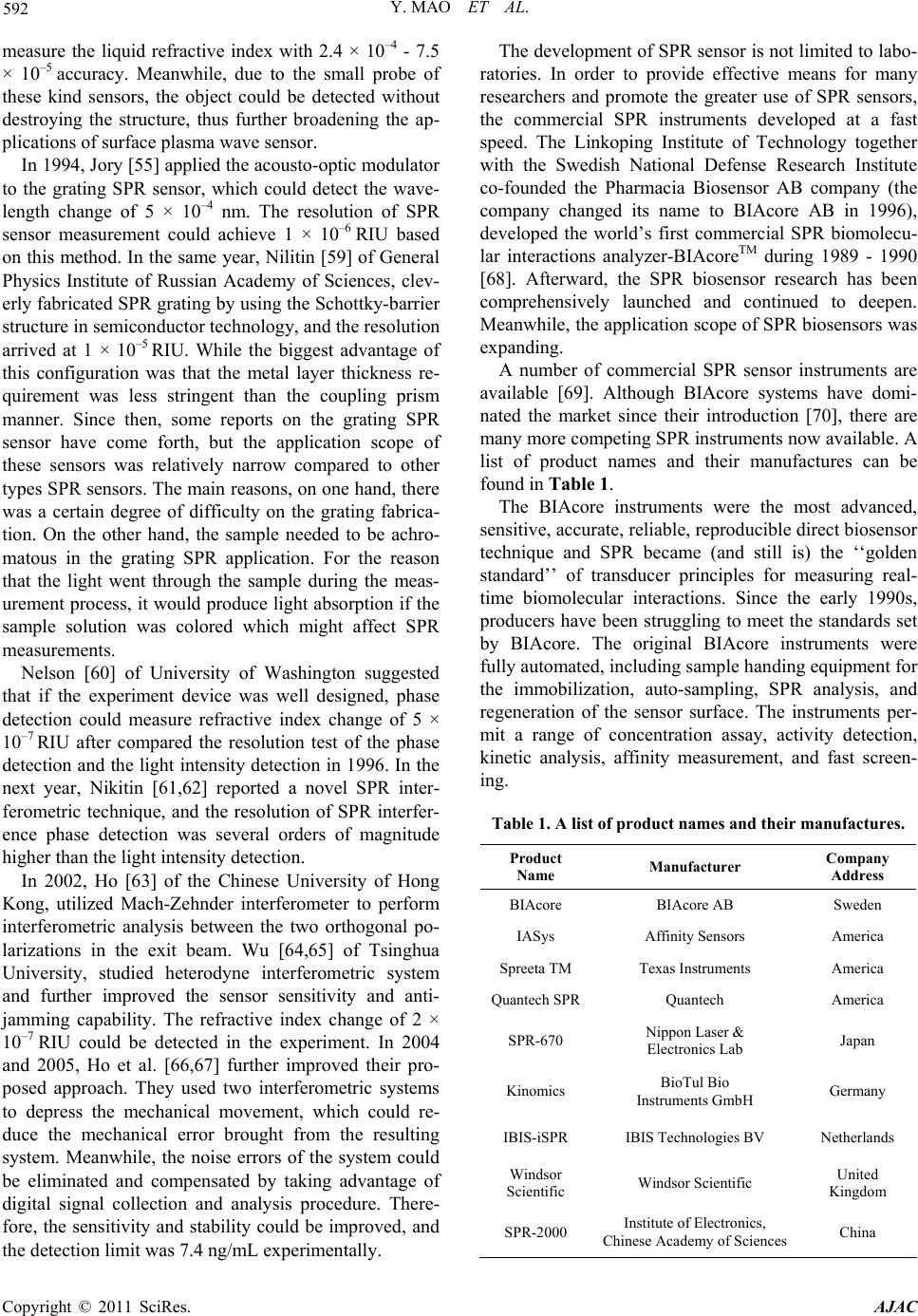

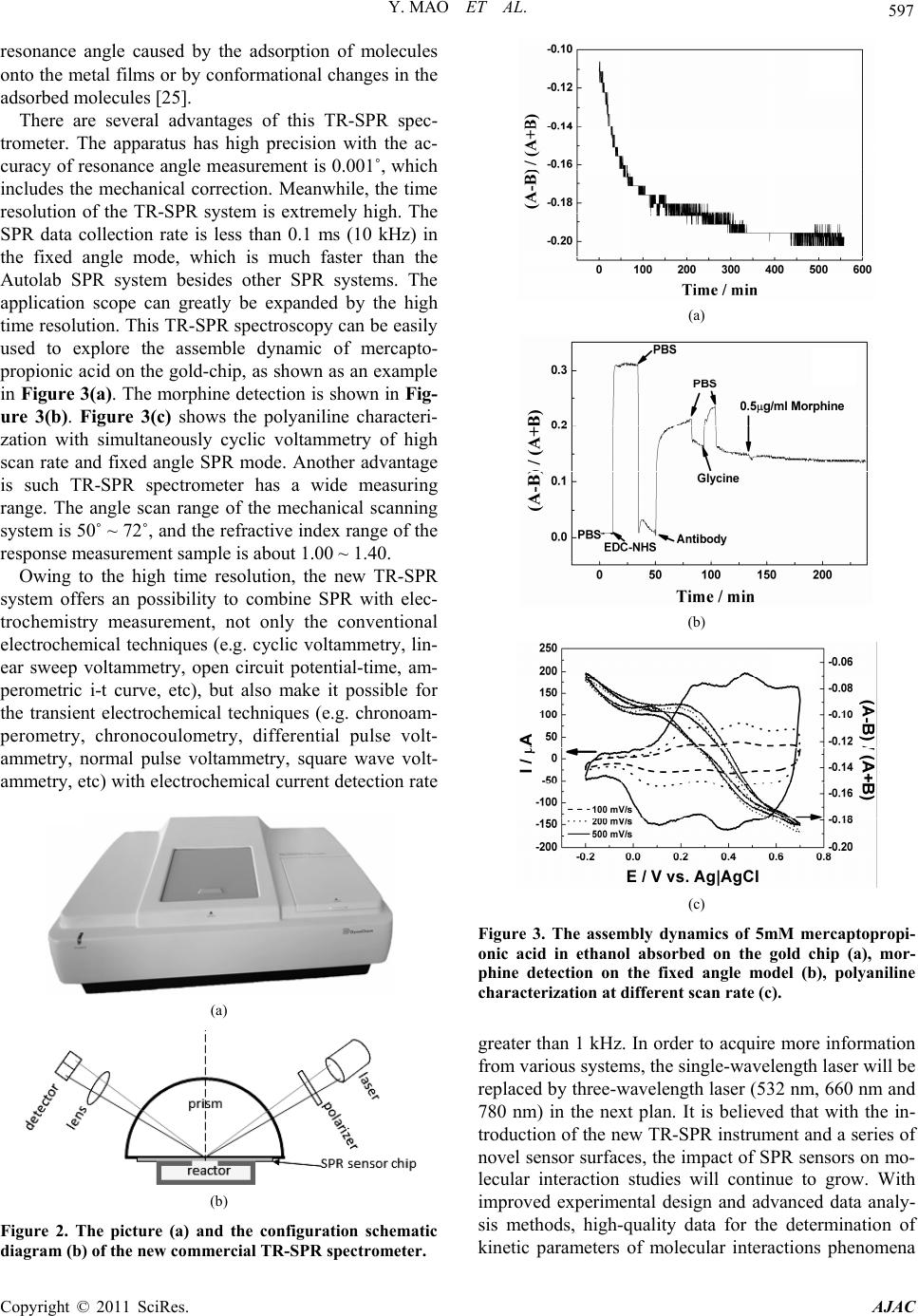

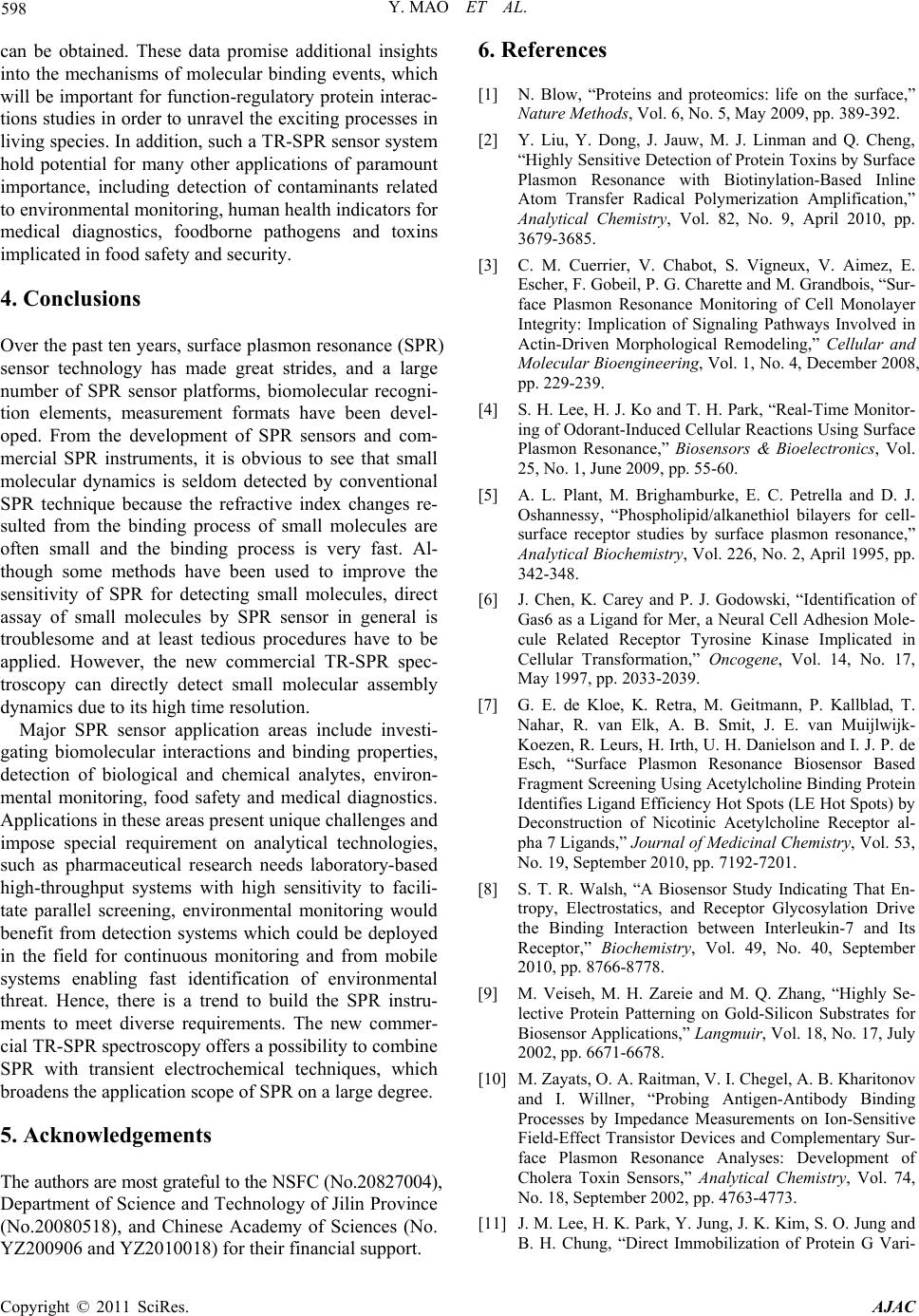

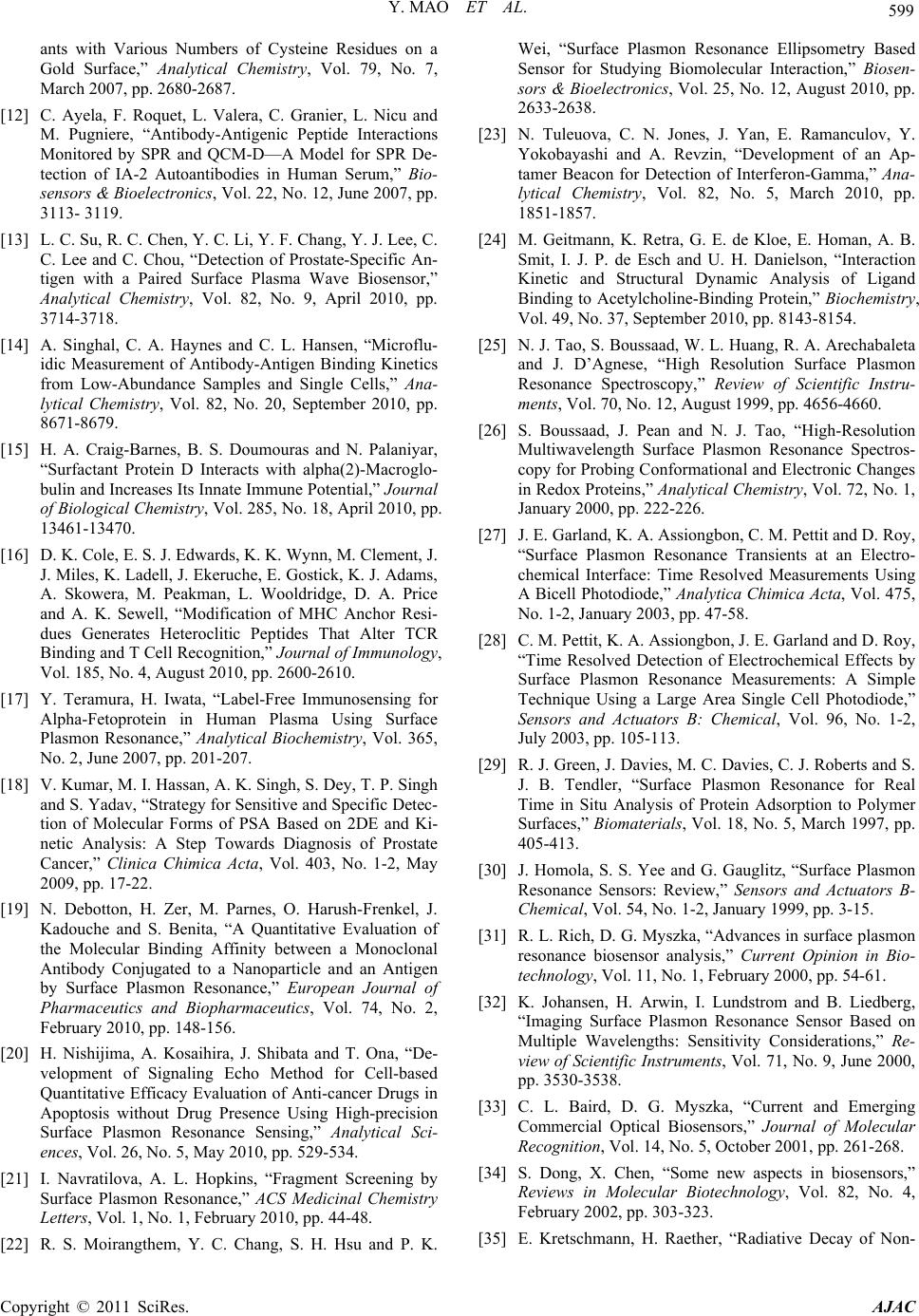

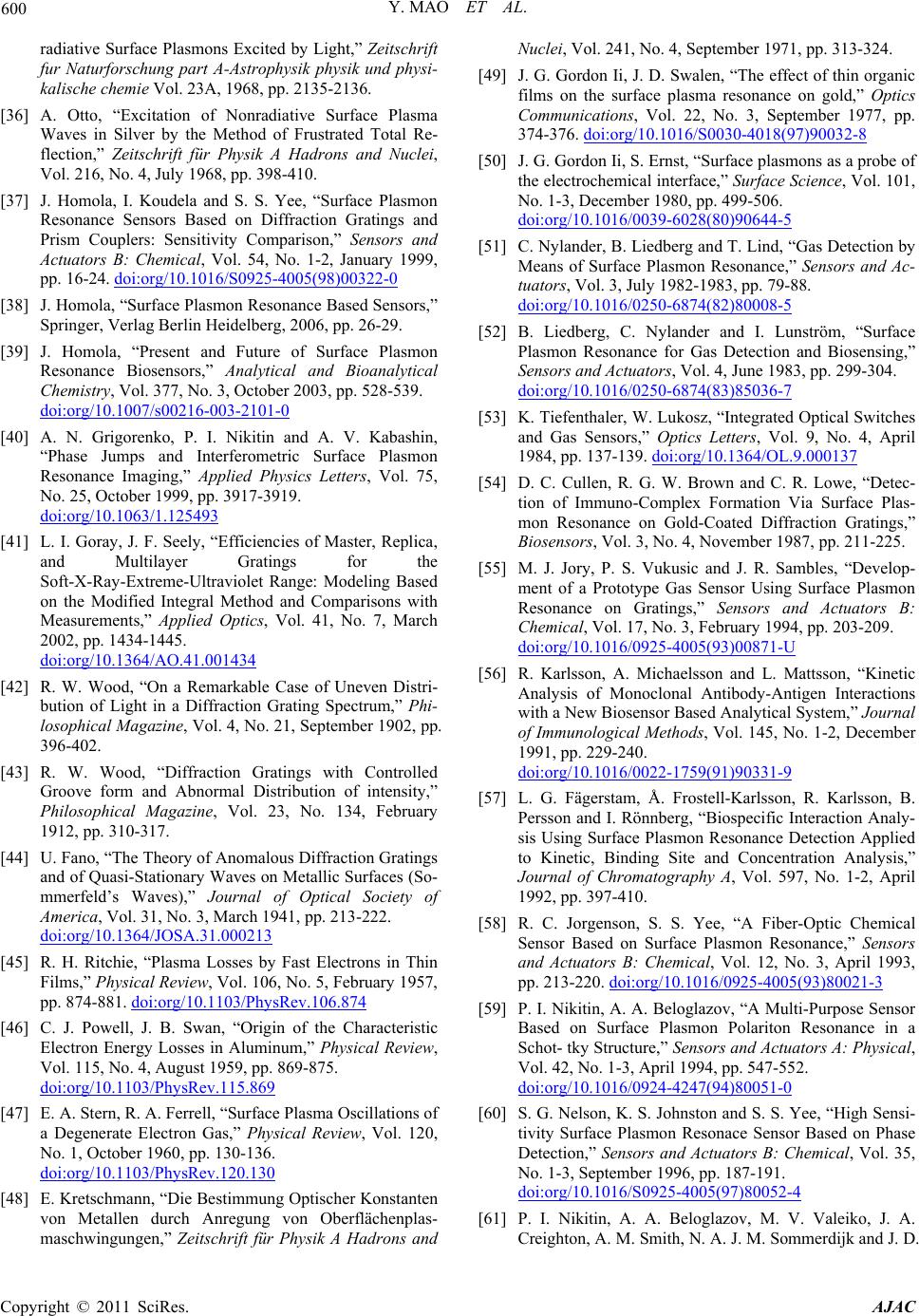

Journal Menu >>