Open Access Library Journal

Vol.03 No.12(2016), Article ID:72946,14 pages

10.4236/oalib.1103215

A Kind of Neither Keynesian Nor Neoclassical Model (2): The Business Cycle

Ming’an Zhan1, Zhan Zhan2

1Yunnan University, Kunming, China

2Westa College, Southwest University, Chongqing, China

Copyright © 2016 by authors and Open Access Library Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: November 9, 2016; Accepted: December 19, 2016; Published: December 23, 2016

ABSTRACT

The Cobb-Douglas function not only leads to a long-term relationship between the rate of output change and the interest rate, but also analyzes why they fluctuate in the short-term. This paper first divides the fluctuation cycle of the interest rate in the statistical data of the past 45 years by using the mathematical phase diagram method, and draws the phase diagram of the rate of output change on the interest rate according to the cycle equation of output. From this phase diagram, we explain the reason that the phase difference between the interest rate and the rate of output change in the fluctuation. Then, according to the optimal relation between L and K in the Cobb-Douglas function, we further derive the employment equation and its relation to the real interest rate and the rate of real output change, and verify the theoretical speculation with statistical data. Finally, it is concluded that the business cycle is a kind of endogenous production phenomenon.

Subject Areas:

Economics

Keywords:

Cobb-Douglas Function, Business Cycles, Phase Diagram, Unemployment Rate

1. Introduction

Neoclassic theories believe that the surplus of output and unemployment would be cleaned out during competition and equilibrium is the normality of the economic system, therefore the fluctuation of macroeconomic variables is generated by external factors. The “Real Business Cycle Model” (RBC) arisen during 1980s considers the total factor productivity or the random perturbations of technology determine fluctuation of other variables [1] [2] [3] . However, other economists [4] [5] gave this theory some questions: according to RBC, if the economic boom was generated by the technological progress, then the economic recession should blame on technological setbacks. Nevertheless, what are reasons of technological setbacks? Moreover, if we use other methods to measure the technological impact, it can be a factor that eliminates business cycles [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] .

Hayek said: “the incorporation of cyclical phenomena into the system of economic equilibrium theory, which they are on apparent contradiction.” [11] . Since the interaction of the total supply and total demand leads to convergence rather than divergence, the convergence would flatten the fluctuation ever if there were external impacts assumed by the RBC theory. Perhaps the biggest problem with macroeconomics is explaining business cycles.

2. The Business Cycle Equation and Divisions

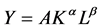

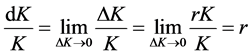

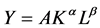

From the Cobb-Douglas function , we deduce the marginal revenue of the capital Kin the paper “A kind of neither Keynesian nor neoclassical model (1): fundamental equation” [12] :

, we deduce the marginal revenue of the capital Kin the paper “A kind of neither Keynesian nor neoclassical model (1): fundamental equation” [12] :

(1)

(1)

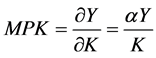

In a competitive market, assuming that the marginal cost of using K is determined by the market interest rate r, the optimal allocation condition for K in production is , then

, then

, (2)

, (2)

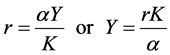

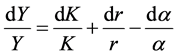

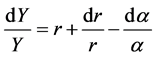

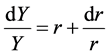

differential on both sides of the equation, so:

, (3)

, (3)

according to the basic equation,

, (4)

, (4)

so Equation (3) can be rewritten as:

(5)

(5)

When r and  are constant,

are constant,  ,

,  ,

, . This is the macroeconomic basic equation. Equation (5) contains more information than the fundamental equation

. This is the macroeconomic basic equation. Equation (5) contains more information than the fundamental equation . It can be used to analyze the relationship of short-term fluctuations between

. It can be used to analyze the relationship of short-term fluctuations between  and r.

and r.

In , the income distribution parameter

, the income distribution parameter  mainly affects the long-term growth (We will analyze this problem in another paper “The economic growth”), assuming

mainly affects the long-term growth (We will analyze this problem in another paper “The economic growth”), assuming , then Equation (5) can be simplified as:

, then Equation (5) can be simplified as:

(6)

(6)

This is the business cycle equation. The change of

By

As shown in Figure 1(a), since

At point B or D,

According to the phase diagram

Based on the phase diagram

Figure 2 is a phase diagram

This is caused by the collection of data has longer interval time than the real fluctuation. Take semi-annual data to redraw this diagram, it is the dotted curve rather than the solid curve during 1983-1985. Therefore, 1976-1983 and 1983-1986 are two different cycles. In the same way, 2003-2009 and 2009-2012 are also two cycles in 2003-2012.

According to annual statistical data and the dividing rule showed in Figure 1(a), there are 9 cycles of fluctuation of interest rate during 1970-2015 of the United States: 1972-1976, 1976-1983, 1983-1986, 1986-1993, 1993-1998, 1998-2003, 2003-2009, 2009- 2012, 2012-. According to the present statistical data (10/2016), r in 2016 may not be

Figure 1. Mathematical phase diagram about periodic fluctuation of r. (a) Phase diagram r~ dr/r. (b) Time path of r.

higher than 2015, so we guess 2016 is also in the cycle since 2012. Figure 3 shows the corresponding time path.

Figure 2. Phase diagram r~dr/r based on statistical data. Sources: 1)

Figure 3. Business cycles divided by the change of r. Sources: Light and dark areas show different cycles. Figure 2 shows base of the phase diagram

3. The Relationship between the Periodicity of dY/Y and r

According to Equation (6), the change rate of output

Figure 4. Phase diagram

Point a and c on

Figure 5 shows the time path of

As shown in Figure 5(c) and Figure 5(d), the time path of

Figure 5. Phase difference of time paths of

In Figure 6, statistical data during 1970-2015 verified the phase difference between time paths of

The foundation equation

4. Periodicity of the Unemployment Rate

Based on algebraic rules, no matter what are the original state of

Apparently, the condition of

Figure 6. Phase differences between statistical data

Equation (8)

since

among them,

In

The statistical data Y and r are the nominal values with money when calculate

When

Since

Since

As Figure 8 shows, the fluctuation of

Above statistical data show that the change rate of employment

According to Equation (6) assume

Figure 7. Relations between

Figure 8. Relations between

The structure of Equation (13) is similar to that of

into

As Figure 9 shows, the direction of rotation and shape of the phase diagram

According to Equation (13), the reason of short-term fluctuation of

The phase diagram

Figure 9. Relations between phase diagrams

Figure 10. Relations between

In order to discuss the relationship between the unemployment rate

Based on Equation (15) we can convert the phase diagram

The

While the above analysis explains the reasons for the cycle in the unemployment rate, there is one fundamental problem that remains unsolved: We cannot determine the value of

Friedman considered although the unemployment state would be affected by “market imperfections, stochastic variability in demands and supplies, the cost of gathering information about job vacancies and labor availabilities, the costs of mobility, and so

Figure 12. Relations between

on” [13] , the unemployment rate fluctuated around the natural rate of unemployment in short term. Factors that Friedman took as examples are also initial conditions that affect the differential equation

5. Conclusions

5.1. Hypothesis

² Production function in the market system:

² A marginal condition:

²

5.2. Results

² The cycle equation about the output:

² The cycle equation about the employment:

5.3. Discussion

² Traditional macroeconomics cannot logically explain contradictions of economic problems in long-term and short-term. Classical theory seems to be handy in explaining relationships between variables in long-term, but it is difficult to understand the phenomenon in short-term. Keynesian theory, while able to explain some phenomenon in short-term, but there will be ridiculous inference in long-term. From the model in this paper and “A kind of neither Keynesian nor neoclassical model (1): the fundamental equation” [12] , we can logically and consistently see relationships between the macroeconomic variables in the long-term and the short- term, and use statistical data to verify these relationships.

² The cycle is affected by many factors, but as long as the marginal product of the economic system is not zero, there is the business cycle even without these external stochastic factors. Since r and

² Due to the limited data sources and the heavy workload of processing data, this paper is limited to the verification of annual data. It is not known whether these periodic equations also apply to quarterly or monthly data.

Cite this paper

Zhan, M.A. and Zhan, Z. (2016) A Kind of Neither Keyne- sian Nor Neoclassical Model (2): The Busi- ness Cycle. Open Access Library Journal, 3: e3215. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/oalib.1103215

References

- 1. Kydland, F.E. and Prescott, E.C. (1988) The Workweek of Capital and Its Cyclical Implications. Journal of Monetary Economics, 21, 343-306.

https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3932(88)90035-9 - 2. Kydland, F.E. and Prescott, E.C. (1990) Business Cycle: Real Facts and a Monetary Myth. Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review, 14, 3-18.

- 3. Kydland, F.E. and Prescott, E.C. (1991) The Econometrics of the General Equilibrium Approach to Business Cycle. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 93, 161-178.

https://doi.org/10.2307/3440324 - 4. Summers, L.H. (1986) Some Skeptical Observations on Real Business Cycle Theory. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review, 10, 23-27.

- 5. Mankiw, N.G. (1989) Real Business Cycles: A New Keynesian Perspective. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 3, 79-90.

https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.3.3.79 - 6. Burside, C., Eichenbaum, M. and Rebelo, S. (1996) Sectoral Solow Residuals. European Economic Review, 40, 861-869.

https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-2921(95)00095-X - 7. Basu, S. and Kimball, M.S. (1997) Cyclical Productivity with Unobserved Input Variation. NBER Working Paper Series, number 5915.

- 8. Muellbauer, J. (1997) The Assessment: Business Cycles. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 13, 1-18.

https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/13.3.1 - 9. Gall, J. (1999) Technology, Employment and Business Cycles: Do Technology Shocks Explain Aggregate Fluctuation? American Economic Review, 89, 249-271.

https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.89.1.249 - 10. Ramey, V.A. and Neville, F. (2002) Is the Technology-Driven Real Business Cycle Hypothesis Dead? Shocks and Aggregate Fluctuations Revisited. University of California at San Diego, Economics Working Paper Series qt6x80k3nx.

- 11. Hayek, F.A. (1929) Monetary Theory and the Trade Cycle, New York: Augustus M. Kelley, 1966; reprint of 1933 English Edition, London: Jonathan Cape; originally published in German in 1929.

- 12. Zhan, M.A. and Zhan, Z. (2016) A Kind of Neither Keynesian Nor Neoclassical Model (1): The Fundamental Equation. Open Access Library Journal, 3, e3207.

https://doi.org/10.4236/oalib.1103207 - 13. Friedman, M. (1968) The Role of Monetary Policy. American Economic Review, 58, 1-17.

and

and  in 1970-2015. Sources: Date of

in 1970-2015. Sources: Date of  is same

is same  .

.