Open Access Library Journal

Vol.03 No.12(2016), Article ID:72788,10 pages

10.4236/oalib.1103264

A Theory of Weak Interaction Dynamics

Eliahu Comay

Charactell Ltd., Tel-Aviv, Israel

Copyright © 2016 by author and Open Access Library Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: November 29, 2016; Accepted: December 12, 2016; Published: December 15, 2016

ABSTRACT

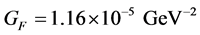

Problems with the electroweak theory indicate the need for a consistent weak inter- actions theory. The analysis presented in this work is restricted to the relatively simple case of elastic scattering of a neutrino on a Dirac particle. The theory pre- sented herein assumes that the neutrino is a massive particle. Furthermore, the di- mension  of the Fermi constant

of the Fermi constant  as well as its universal property are used as elements of the theory. On this basis, it is assumed that weak interactions are a dipole-dipole interaction mediated by a weak field. An interaction term that re- presents weak interactions is added to the Dirac Lagrangian density. The identity

as well as its universal property are used as elements of the theory. On this basis, it is assumed that weak interactions are a dipole-dipole interaction mediated by a weak field. An interaction term that re- presents weak interactions is added to the Dirac Lagrangian density. The identity  is used in an analysis which proves that the interaction violates parity because it consists of two terms-a vector and an axial vector. This outcome is in accordance with the experimentally confirmed V-A property of weak interactions.

is used in an analysis which proves that the interaction violates parity because it consists of two terms-a vector and an axial vector. This outcome is in accordance with the experimentally confirmed V-A property of weak interactions.

Subject Areas:

Theoretical Physics

Keywords:

Weak Interaction Dynamics, Lagrangian Density, Parity Nonconservation, V-A

1. Introduction

Weak interactions have some unique properties that cannot be found in other kinds of interactions. The following points illustrate this claim.

・ Weak interactions do not conserve parity.

・ Weak interactions do not conserve flavor.

・ The time duration of weak processes span many orders of magnitude. For example, the neutron’s mean life is 880 sec whereas that of the top quark is about 10−24 sec [1] . (Here examples of a very long mean life of about 109 years, like that of the 40K nucleus, are omitted because this effect is due to the difference in the quantum mechanical angular momentum of the nuclei involved in the process.)

・ The weak interactions coupling constant is written in units that have the dimension of energy−2,  (see [2] , pp. 19, 212).

(see [2] , pp. 19, 212).

These weak interactions properties indicate that its theory should have a specific structure. Another issue is the existence of unsettled problems with the electroweak theory. Some of these problems are mentioned in the second section. Considering this state of affairs, the present work describes elements of a consistent weak interactions theory. As a first step, the discussion is restricted to the simplest case of an elastic neutrino scattering (see [3] ).

A fundamental property of Quantum Field Theory (QFT) is the description of a par- ticle by means of a function the takes the form  (see e.g [4] , p. 299). Here

(see e.g [4] , p. 299). Here  denotes a single set of four space-time coordinates. It means that such a function des- cribes a pointlike particle. Indeed,

denotes a single set of four space-time coordinates. It means that such a function des- cribes a pointlike particle. Indeed,  can describe the position of a particle at a given time but not its distribution around this point. Experimental data support the pointlike property of elementary particles (see e.g. [5] ). Evidently, two points cannot collide. Therefore, a mediating field is required for a description of a scattering process of pointlike particles.

can describe the position of a particle at a given time but not its distribution around this point. Experimental data support the pointlike property of elementary particles (see e.g. [5] ). Evidently, two points cannot collide. Therefore, a mediating field is required for a description of a scattering process of pointlike particles.

The need for a mediating field in weak interactions is analogous to a corresponding property of quantum electrodynamics (QED), where Maxwellian fields interact with a pointlike charge of an elementary particle. Electrodynamics is certainly the best phy- sical theory because it has many experimental supports as well as a tremendous number of specific applications in contemporary technology. The present work aims to cons- truct a weak interaction theory that has a certain similarity with QED. In particular, it follows the structure of QED and uses a weak interaction term that is added to the Lagrangian density of the system. Specific aspects of this similarity are described below in appropriate places.

Units where  are used. Greek indices run from 0 to 3 and Latin indices run from 1 to 3. The metric is diag.

are used. Greek indices run from 0 to 3 and Latin indices run from 1 to 3. The metric is diag. . Square brackets [] denote the dimension of the enclosed expression. In a system of units where

. Square brackets [] denote the dimension of the enclosed expression. In a system of units where  there is just one di- mension, and the dimension of length, denoted by

there is just one di- mension, and the dimension of length, denoted by , is used. In particular, energy and momentum take the dimension

, is used. In particular, energy and momentum take the dimension  and the dimension of a dipole is

and the dimension of a dipole is .

.

2. Problems with the Electroweak Theory

Several theoretical problems of the electroweak theory are briefly presented in this section. A fundamental principle used herein is the correspondence between QFT and quantum mechanics. S. Weinberg has used the following words for describing this principle: “First, some good news: quantum field theory is based on the same quantum mechanics that was invented by Schroedinger, Heisenberg, Pauli, Born, and others in 1925-26, and has been used ever since in atomic, molecular, nuclear and condensed matter physics” (see [4] , p. 49). This principle can also be found in pp. 1-6 of [6] . Hereafter, this relationship is called “Weinberg correspondence principle”.

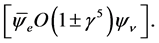

The following review article states that it is now recognized “that neutrinos can no longer be considered as massless particles” (see [3] , p. 1307). It means that the neutrino is an ordinary massive Dirac particle which is described by a 4-component spinor. (The argument also applies to a Majorana neutrino.) This experimental evidence does not fit the original structure of the Standard Model where the neutrino is treated as a 2-com- ponent massless particle [7] . In the following lines it is proved that this property of the neutrinos is inconsistent with expressions that have the factor . The factor

. The factor  has been proposed for a two-component massless Weil neutrino (see [2] , p. 219, 367). For example, it is used in a description of an electron-neutrino interaction (see [2] , pp. 219-220)

has been proposed for a two-component massless Weil neutrino (see [2] , p. 219, 367). For example, it is used in a description of an electron-neutrino interaction (see [2] , pp. 219-220)

(1)

(1)

Here  represents an appropriate operator which operates on

represents an appropriate operator which operates on . It turns out that this expression does not hold for a massive Dirac neutrino. Indeed, operating with

. It turns out that this expression does not hold for a massive Dirac neutrino. Indeed, operating with

Here the

The right hand side of (2) is a Dirac spinor that has an infinite energy-momentum (see [8] , p. 30). It means that the operator

The factor

Let us examine other electroweak contradictions. The

It turns out that these two different tasks cannot be accomplished simultaneously. For example, the electromagnetic interaction term is

The lack of a consistent expression for the 4-current of the

The origin of this contradiction can be briefly explained. Due to a widely acceptable rule, the following substitution is introduced in order to account for the electromag- netic interactions

The lack of a consistent expression for the W's conserved 4-current also violates the Weinberg correspondence principle, because the Schroedinger equation has a con- sistent expression for a conserved density and current (see [14] , pp. 53-55).

It can be shown that the electroweak

The contradictions of the electroweak theory indicate that a consistent theory of weak interactions is needed. Evidently, experimental data provide clues for a con- struction of such a theory. These issues are discussed in the rest of this work.

3. Fundamental Elements of a Theory of Weak Interaction Dynamics

The weak interaction theory constructed below aims to follow the theoretical structure of QED. Hence, the main problem is how to construct an expression that represents weak interactions in the form of a term of the Lagrangian density of a Dirac particle. In the case of electromagnetic interaction, the 4-current of a Dirac particle is

It means that the electromagnetic interaction term is the contraction of the 4-vector of the

This quantity is a dimensionless Lorentz scalar.

The weak interaction theory described herein abides by the experimental evidence where, in the units

Hence, the required weak interaction term differs from its electromagnetic counterpart (3), where the electric charge is a dimensionless Lorentz scalar.

Following (5) and the dipole’s dimension

1) What is the structure of the weak field that mediate the interaction between the weak dipoles?

2) What is the form of the weak interaction term of the system’s Lagrangian density?

A resolution of the first problem is quite simple. The weak field of a weak dipole takes the Maxwellian-like form of an axial dipole. This dipole is carried by every elementary spin-1/2 particle. Hereafter, the strength of this elementary weak dipole is denoted by d. This symbol differs from the mathematical symbol

The tensorial form of this field has magnetic-like components and electric-like com- ponents. Its explicit structure is (see [13] , p. 65)

The calligraphic letters

Let us turn to the second problem. Like all other terms of the Lagrangian density, the electromagnetic interaction term (3) is a dimensionless Lorentz scalar. It holds for the interactions of the Dirac particle’s electric charge, which is a dimensionless Lorentz scalar. Hence, the problem is to find the form of an analogous expression for the elementary weak dipole, which has the inherent dimension

This formula indicates how to construct the required expression. It must depend linearly on the Maxwellian-like weak field of a weak dipole. The very small limit of the neutrino mass [1] means that in actual experiments the neutrino is an ultrarelativistic particle where

In order to construct a Lorentz scalar term for the Lagrangian density of the weak interactions, one must contract the tensor (6) with another tensor which depends on the Dirac

Let us write down the explicit form of (9) as a

Here the anti-commutation of two different

The weak interaction term of the Lagrangian density is obtained from a contraction of (10) and (6), times the scalar factor d, which represents the weak dipole strength. Hence, the term which is analogous to the electromagnetic interaction term (3) is

Note that the pure imaginary factor

The structure of the primary weak interaction term (11) satisfies the Lagrangian density requirements. Due to fundamental laws of tensor algebra, the full contraction of the two tensors proves that this term is a Lorentz scalar. The dipole’s field decreases like

As stated in the introduction, the purpose of this work is to find a theory of weak interactions processes where flavor is conserved. It means, a description of an elastic neutrino scattering on a Dirac particle. This process is analogous to the elastic scattering of an electron. Thus, the problem is to find the form of the interaction of the weak dipole of a spin-

Here

The primary weak interaction term (11) is used for obtaining an expression for the integrand of the scattering formula (12). For this end, the identity

is used (see [8] , p. 24). The following calculation proves that

In the second line of (14) three terms are multiplied by

The three

Hence, the two terms of (14) are Hermitian operators which correspond to the vector V and the axial vector A parts of the weak interactions, respectively. Relation (8) means that these terms are contracted with 3-vectors that practically have the same absolute value. It means that the weak interaction theory which is derived above proves that weak processes do not conserve parity. This result is also consistent with the equal weight of V and A in the well known V-A form of weak interactions [18] [19] . It means that the dipole structure of the weak interaction theory developed herein proves that an interaction of a neutrino with a Dirac particle is in accordance with the parity violating V-A form of weak interactions.

4. Concluding Remarks

This work aims to make the first step towards the construction of a consistent weak interaction theory. As such, it examines the relatively simple process of an elastic neutrino scattering. Like the case of other theories, it must take some kinds of ex- perimentally related information that is used as a basis for the mathematical structure of the theory. This work uses just one specific kind of experimental information which is the Fermi constant. The theory uses the dimension of the Fermi constant

The general structure of the theory is similar to that of QED. It comprises two kinds of physical objects, a weak axial dipole which is associated with a massive Dirac particle and a weak field that mediates the interaction between two weak dipoles. The need for such a field is deduced from the pointlike attribute of an elementary quantum particle.

The mathematical structure of the theory is built on these issues and the result proves that weak interactions do not conserve parity. This theoretical result is in accordance with a well known property of weak interactions. This success encourages a further research in this direction.

The Lagrangian density obtained above describes weak interactions of two spin-1/2 Dirac particles which is mediated by a weak field. In actual cases of scattering ex- periments, one should remove other, much stronger interactions. Therefore, one of the interacting particles must be a neutrino (or an anti-neutrino).

Other aspects of weak interactions should be analyzed. Here are some points:

1) The weak dipole depends on spin orientation. Taking into account that in a neutrino scattering the target is a macroscopic body, one must calculate how a neu- trino interacts with an electron whose wave function is not an eigenfunction of

2) Flavor changing processes should be calculated.

3) The CKM matrix as well as the neutrino oscillation indicate that there are three kinds (called generations) of weak dipoles which interact with each other. In hadrons, weak interactions cause transition within generations and in hadrons and leptons they also cause transition between generations. This evidence certainly complicates the struc- ture of a comprehensive weak interaction theory.

Cite this paper

Comay, E. (2016) A Theory of Weak Interaction Dynamics. Open Access Library Journal, 3: e3264. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/oalib.1103264

References

- 1. Patrignani, C., et al. (Particle Data Group) (2016) Review of Particle Physics. Chinese Physics C, 40, Article ID: 100001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1674-1137/40/10/100001

- 2. Perkins, D.H. (1987) Introduction to High Energy Physics. Addison-Wesley, Menlo Park.

- 3. Formaggio, J.A. and Zeller, G.P. (2012) From eV to EeV: Neutrino Cross Sections across Energy Scales. Reviews of Modern Physics, 84, 1307. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.84.1307

- 4. Weinberg, S. (1995) The Quantum Theory of Fields. Vol. I, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- 5. Dehmelt, H. (1988) A Single Atomic Particle Forever Floating at Rest in Free Space: New Value for Electron Radius. Physica Scripta, 1988, T22. https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-8949/1988/T22/016

- 6. Rohrlich, F. (2007) Classical Charged Particle. World Scientific, New Jersey. https://doi.org/10.1142/6220

- 7. Bilenky, S.M. (2015) Neutrino in Standard Model and beyond. Physics of Particles and Nuclei, 46, 475-496. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1063779615040024

- 8. Bjorken, J.D. and Drell, S.D. (1964) Relativistic Quantum Mechanics. McGraw-Hill, New York.

- 9. Comay, E. (2013) Further Problems with Integral Spin Charged Particles. Progress in Physics, 3, 144.

- 10. Abazov, V.M., et al. (D0 Collaboration) (2012) Limits on Anomalous Trilinear Gauge Boson Couplings from WW, WZ and Wγ Production in collisions at . Physics Letters B, 718, 451-459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2012.10.062

- 11. Aad, G., et al. (2012) Measurement of the WW Cross Section in √s=7 TeV pp Collisions with the ATLAS Detector and Limits on Anomalous Gauge Couplings. Physics Letters B, 712, 289-308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2012.05.003

- 12. Bjorken, J.D. and Drell, S.D. (1965) Relativistic Quantum Fields. McGraw-Hill, New York.

- 13. Landau, L.D. and Lifshitz, E.M. (2005) The Classical Theory of Fields. Elsevier, Amsterdam.

- 14. Landau, L.D. and Lifshitz, E.M. (1959) Quantum Mechanics. Pergamon, London.

- 15. Weinberg, S. (1996) The Quantum Theory of Fields. Vol. 2, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139644174

- 16. Comay, E. (2016) Problems with Mathematically Real Quantum Wave Functions. Open Access Library Journal, 3, e2921. http://www.oalib.com/paper/5271393#.WCFay9R97xi https://doi.org/10.4236/oalib.1102921

- 17. Jackson, J.D. (1975) Classical Electrodynamics. John Wiley, New York.

- 18. Glashow, S. (2009) Message for Sudarshan Symposium. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 196, Article ID: 011003. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/196/1/011003

- 19. Feynman, R.P. and Gell-Mann, M. (1958) Theory of the Fermi Interaction. Physical Review, 109, 193-198. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.109.193