Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

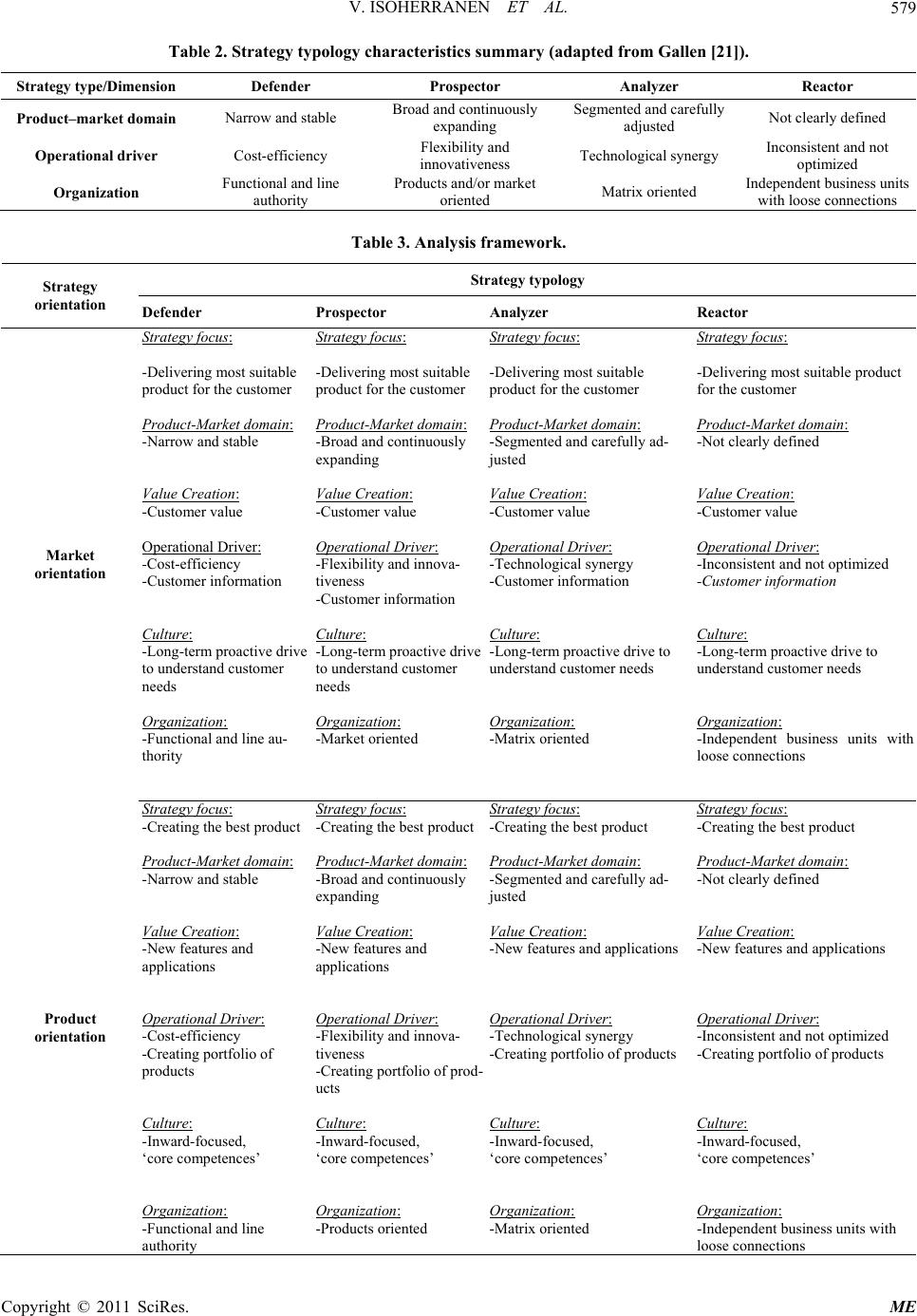

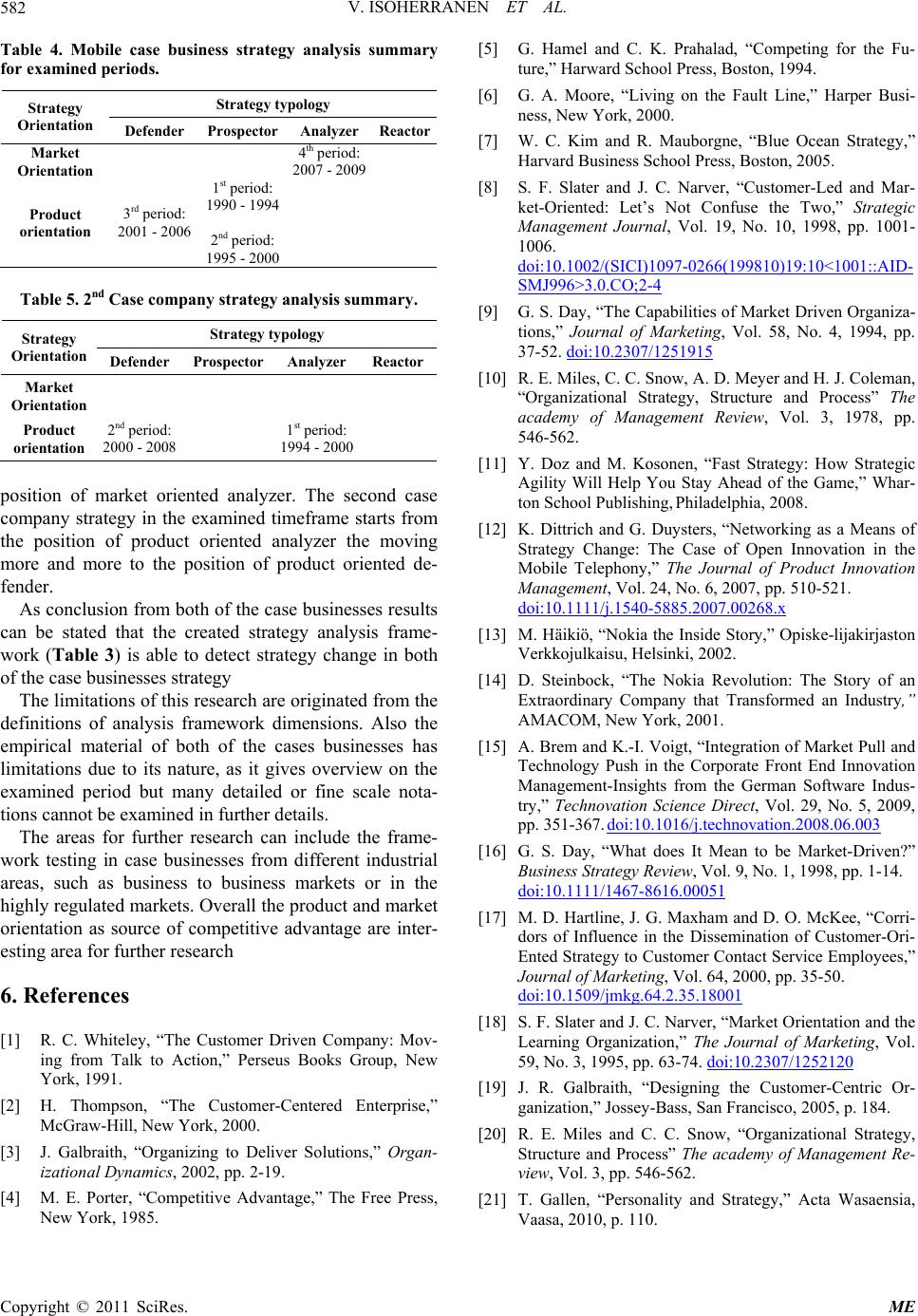

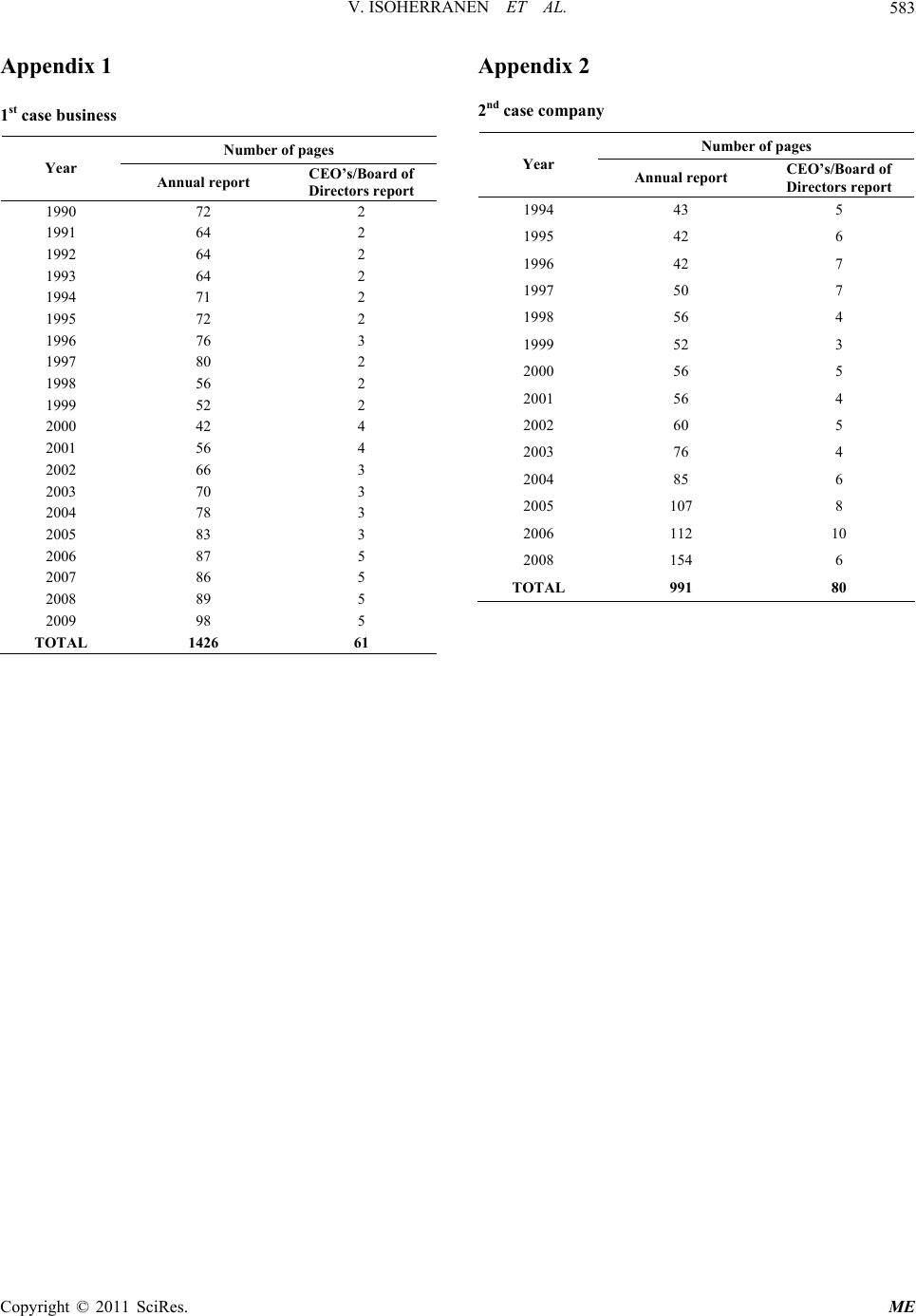

Modern Economy, 2011, 2, 575-583 doi:10.4236/me.2011.24064 Published Online September 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/me) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME Analysis of Strategy by Strategy Typology and Orientation Framework Ville Isoherranen, Pekka Kess Elektroniikkatie, Oulu, Finland Department of Industrial Engineering and Management Faculty of Engineering, University of Oulu, Finland E-mail: ville.isoherranen@nokia.com, pekka.kess@oulu.fi Received June 12, 2011; revised July 22, 2011; accepted July 31, 2011 Abstract This study analyses the two case businesses strategy by using the strategy orientation and typology frame- work. The framework is build as synthesis from market and product orientation characteristics found from literature as well as the Miles and Snow strategy typology. This framework is used to evaluate Nokia mobile phones and Amer strategy. Nokia’s and Amer’s successful business and business transformations contribute to the selection. The findings show that the created framework is able to find orientation and typology changes in both of the case businesses. Keywords: Strategy Analysis Framework, Strategy Typology, Market Orientation, Product Orientation 1. Introduction The increasing power of buyers in highly competitive markets forces companies to get closer to customers in order to maintain their business and to create value- adding solutions to capture more revenue from their cus- tomer base [1-3]. Strategy creation and its challenges in highly competitive market has been discussed e.g. by Porter [4], Hamel and Prahalad [5], Moore [6], and Kim and Mauborgne [7]. Market orientated companies, focused on market pull, build their strategy by having a long-term commitment to understand customer needs, and thus developing innova- tive solutions by discovering hidden customer needs and new markets ([8,9]). Product oriented, product focused, strategy can be seen as internally focused company’s strategy that pursuits competitive advantage by deliver- ing cutting-edge products with best features, based its core-competences. [3] Strategy typology as presented by Miles et al. [10] proposes a strategy classification of four distinct types: prospectors, defenders, analyzers and reactors. Any of the three first strategies can be successful in the market place. Reactor strategy can be considered as failure to execute one of these strategies. In this study, we examine the two above-mentioned approaches to strategy: the market oriented and product- oriented views in the context of Miles et al. [10] strategy typology by building synthesis framework of these theo- ries. Focus is also to do analysis of case businesses strategies by using this framework. The case business NOKIA is an old Finnish company. Company has been founded in 1865. In 1995, it focused on telecommunication businesses and in 2007 in mobile phone products and services, when the network systems business merged with Siemens and Nokia Siemens Net- works was established. Nokia is the global leader in mo- bile telecommunications and has dominated the telecom market for years. Nokia shipped 2009 over 430 million units of mobile devices, average of over 1.1 million units a day and thus reaching market share of estimated 35% of mobile devices market. The transformation of Nokia from a company constructed of several different business areas, such as car tyres, cables, TV’s and industry elec- tronics, to company that has focus on telecommunication has been remarkable. Nokia made strategic decision to focus on one of its business areas, and has been able to grow significantly due to this strategic choice. Especially, this choice has been followed by long growth in sales of Nokia’s mobile phones and thus Nokia has gained lead- ing market position in mobile phone market. This suc- cess and growth makes Nokia mobile phone business interesting case example to study strategy orientation due to its ability to maintain competitiveness. In addition, the ongoing transformation of Nokia from mo- bile phones focused company to also as a provider of internet-based  V. ISOHERRANEN ET AL. 576 services, also make Nokia’s mobile phone business rele- vant research case for strategy orientation. Nokia’s strategy has been especially discussed by Doz and Kos- onen [11], from the viewpoint of strategic agility. Other academic papers written about Nokia cover e.g. topics from open innovation and innovation networks [12], Nokia’s growth success factors [13], and the fun- da- mental change that Nokia brough to telecommuniation industry [14]. The second case company AMER operates interna- tionally, and focuses on marketing and manufacturing of branded sports equipment. The parent company Amer Group is a publicly listed company that was established on 1950. Amer has long history on multiple business areas, such as tobacco, sporting and leisure goods and car importing. Amer divested its entire Paper division on 1994, and sold the entire Publishing and Printing division. Later on same year, Amer acquired the Atomic sports equipment manufacturing company to strengthen its po- sition as manufacturer of sporting branded goods. Since then Amer has acquitted several sport equipment compa- nies. Amer’s most famous sporting brands are e.g. Wil- son, Atomic and Salomon. This study can be condensed to the following research questions: RQ1: What is the framework to analyze strategy ori- entation with strategy typology? RQ2: How does the case businesses strategy orienta- tion and typology change? 2. Strategy Orientations 2.1. Market Orientation in Strategy Brem and Voigt [15] summarize the market pull to be “characterized by unsatisfied customer that creates new demand, which requires problem solving”. The impulse comes from individuals or groups that state their demand; this impulse is then used for focusing company targets, resources and activities so that this demand can be satis- fied. Day [9] lists the market-driven company features to be a set of beliefs that puts customer’s interest first, abi- lity to generate and use information about customers and competitors, and the ability to coordinate resources for customer value creation. Day [9] also adds that market orientation represents superior skills in understanding and satisfying customers. According to Day [16] market- driven companies know their markets deeply so that they are able to identify valuable customers. Thus these com- panies are able to make strategic choices and implement those consistently. These choices can be e.g. prioritiza- tion of customer requirement in the favor of most valu- able customers or the service levels of which are offered. According to Day [16] the characteristics of market- driven organizations following market oriented strategy can be listed as following: offering superior solutions and experience, focus on customer value, ability to con- vert customer satisfaction into loyalty, drive to energize employees, anticipation of competitor moves by intimate market understanding, viewing marketing as investment and not as costs and leveraging brands assets. Customer value is something fundamental which the buyer, cus- tomer, recognizes to create benefit, so that is without any doubt something that the customer is willing to invest to get this service or product in to use. Slater and Narver [8] summarize market orientation to be continuous collec- tion of target customers’ needs and competitors’ capabi- lities. This means that market orientation strategy drives the operational mode and organization of the company to be able to collect and analyze customer’s needs. This is consistent with Hartline et al. [17] stating “market orien- tation to be organizational culture that creates effectively and efficiently superior value to buyers and thus excel- lent business performance”. Slater and Narver [18] de- scribe the market-oriented approach to be “long-term, proactive, commitment to understand customer needs, both expressed and latent, and develop innovate solu- tions for ensuring high customer value”. At the same time, market-oriented companies, understands, that dif- ferent types of customers provide different levels of in- formation and that customer voice is only one source of information for building strategies. This notion of bal- ance is important part of the market-oriented strategy execution, in order to prevent loose of company’s profi- tability, or that e.g. over executed customization efforts can lead loosing company’s identity, company’s branded assets. Sustainable competitive advantage achieved by the market-oriented strategy can be summarized to be based on the intimate knowledge of customers, ability to select the customers which to serve, and finally offering them unique product or service, which has been build based on the customer knowledge, and delivering it effi- ciently and effectively based on strategic focus. 2.2. Product Orientation in Strategy The biggest difference of view for product oriented and market oriented company is the approach of which com- pany following product oriented strategy drives to find as many uses and customers for its product as possible, in contrast to company focused to listening it customer, which tries to find the most suitable products as possible for its customers and then integrating these for value adding solutions [3]. Galbraith [3], [19] defines the cha- racteristics of product-centric company from 13 different viewpoints. We consider the most important views from Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  V. ISOHERRANEN ET AL.577 strategy point of view to be the goal, main offering, value creation route, customer definition, organizational setup, reward priorities, the priority setting basis and the pricing. According to Galbraith the goal of product product-cen- tric company is to create the best product for customer. The definition of best product is something that separates the product from the competitors and can be sold-in for the customer using these rationales. The value creation route is the cutting-edge products, useful features and new applications. The organizations are built around pro- duct creation, as there are e.g. product business units. The organizational setup focuses on product profit cen- ters and the reward focuses e.g. on the market share. Top managements focus on product reviews and the logic is that more features, capabilities of the products also create more value to product thus driving sales. The priority setting of strategic actions is thus based on portfolio of products, which is the product oriented strategy point of view the main offering. Highest customer priority is given to most advanced customers which take into use the new features and applications created by the product oriented company. This is important due to fact that pro- duct oriented strategy fundamentally focuses on creation of competitive advantage by ultimate product capabilities, thus the adaption of new features is essential. Customers want to be locked to the feature richness thus preventing them to consider competitive options with less features or lack of applications. Thompson [2] describes the transformation journey of inward-focused product driven company via market- focused company to customer-centric company. The cha- racteristics of company focused on the core competences, with certain inward-focus, also can be identified as part of the product oriented company’s strategy [5]. Also the aspects of organizational setup and reward priorities together with measurement principles of suc- cess are essential aspects to consider. Product oriented company measures its success by the market share posi- tion, number of new products created, and the capability to lead by latest product features and top end applica- tions. We define the product focused or product-centric strat- egy in this research to be referred and synonymous as the product oriented strategy. The characteristics of both market orientation (Market pull) and product orientation (Product push) are summa- rized in the Table 1. The summary has been built around four dimensions: strategy focus, value creation, opera- tional driver and culture. 2.3. Strategy Typology Miles et al. [10] and Miles and Snow [20] have proposed Table 1. Strategy orientation characteristics summary. Strategy orientation characteristics by drivers Market orientation, ‘Market pull’ Product orientation ‘Product push’ Strategy focus a) Delivering most suitable product for the customer a) Creating the best product Value creation b) Customer value b) New features and applications Operational driver c) Ability to generate information about customers, “portfolio of customer information” c) Creating portfolio of products Culture d) Long-term proactive drive to understand customer needs d) Inward-focused, ‘core competences’ a strategy classification of four distinct characters: de- fenders, prospectors, analyzers and reactors. The classi- fication is based on assessment of how the company re- sponds to the following three problems or challenges: entrepreneurial, which defines the organization’s pro- duct-market domain engineering, which focuses on the choice of tech- nologies and process for production and distribution administration, which involves the formalization, rationalization and innovation of an organization’s structure and policy processes. The defenders are companies which have a stable set of products or services and compete primarily on the basis of price, quality, and service. Defender organiza- tions face the entrepreneurial problem of how to main- tain a stable share of the market, and hence they function best in stable environments. A common solution to this problem is cost leadership, and so these organizations achieve success by specializing in particular areas and using established and standardized technical processes to maintain low costs. In addition, defender organizations tend to be vertically integrated in order to achieve cost efficiency. Defender organizations face the administra- tive problem of having to ensure efficiency, and thus they require centralization, formal procedures, and dis- crete functions. Because their environments change slowly, defender organizations can rely on long-term planning. The defender strategy entails a decision not to aggres- sively pursue new markets but rather drive to seal off portion of the total market to create stable, hard-to-enter domain for competitors. In this classification the prospectors are defined as companies which are first in the market and have a very broad product-market definition. Prospector organiza- tions face the entrepreneurial problem of locating and exploiting new product and market opportunities. These organizations thrive in changing business environments Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  V. ISOHERRANEN ET AL. 578 that have an element of unpredictability, and succeed by constantly examining the market in a quest for new op- portunities. Moreover, prospector organizations have broad product or service lines and often promote create- vity over efficiency. Prospector organizations face the operational problem of not being dependent on any one technology. Consequently, prospector companies priori- tize new product and service development and innova- tion to meet new and changing customer needs and de- mands and to create new demands. The administrative problem of these companies is how to coordinate diverse business activities and promote innovation. Prospector organizations solve this problem by being decentralized, employing generalists (not specialists), having few levels of management, and encouraging collaboration among different departments and units. The prospector strategy can be seen as the most aggressive on of all these four. For prospector it is important to have reputation as inno- vator both in product and market development. The analyzers have been defined as companies, which have characteristics from both of the prior strategies and they seek a balance between stable and changing do- mains. Analyzer organizations share characteristics with prospector and defender organizations; thus, they face the entrepreneurial problem of how to maintain their shares in existing markets and how to find and exploit new markets and product opportunities. These organiza- tions have the operational problem of maintaining the efficiency of established products or services, while re- maining flexible enough to pursue new business activi- ties. Consequently, they seek technical efficiency to maintain low costs, but they also emphasize new product and service development to remain competitive when the market changes. The administrative problem is how to manage both of these aspects. Like prospector organiza- tions, analyzer organizations cultivate collaboration among different departments and units. Analyzer orga- nizations are characterized by balance, a balance be- tween defender and prospector organizations, analyzer drivers for strategy are minimizing risk while maximiz- ing the opportunity for profit. The reactor organizations do not have a systematic strategy, operational driver, or structure, they exhibit actions both of inconsistent and unstable. They are not prepared for changes they face in their business envi- ronments. If a reactor organization has a defined strategy and structure, it is no longer appropriate for the organiza- tion’s environment. A reactor has no proactive strategy. They react to events as they occur and their response is inappropriate for the situation. Miles et al. (1978) have identified three reasons why organizations become rea- ctors: top management may not have clearly articulated the organization’s strategy, management does not fully shape the organization’s structure and processes to fit a chosen strategy and tendency for management to maintain the organiza- tion’s current strategy-structure relationship despite overwhelming changes in environmental conditions. Also the failure to execute defender, prospector or analyzer strategy can lead the organization actual strat- egy to be reactor approach.The strategy types of Miles and Snow [10] are presented in the Table 2. 2.4. Analysis Framework Based on the literature synthesis we have created strat- egy orientation framework that will use be used for the analysis (Table 3). In this framework the two different orientation characteristics, product and market orienta- tion, are fitted together with the Miles et al. [10] typol- ogy. The framework highlights the trade-off nature of the different orientations but orientations can also co-exist within strategy focus. The framework is build from six dimensions: strategy focus, product-marketing domain, value creation, operational driver, culture and organiza- tion. The characteristics are then combined under these dimensions. 3. Empirical Study 3.1. Research Process The research process is described in the Figure 1. The strategy orientations and strategy typology [10] were studied by using existing literature as a source. The out- put of the literature review was the synthesis in form of the analysis framework. This phase where followed by the case material empirical data collection. This empiri- cal data was collected from the annual reports of the two case businesses. For the first case empirical material was collected through the years 1990 - 2009. This empirical data consisted of 20 case business annual reports (Ap- pendix 1). Time span of nearly 20 years was considered to be sufficiently wide in the fast changing telecommu- nication markets and to bring extensive knowledge on the case business strategy development. These reports where available in printed format in Finnish and in elec- tronic format both in Finnish and English. Both the printed and electronic version where used to achieve rich insight on the case business strategy. For the second case company Amer empirical material was collected from years 1994 to 2008 (Appendix 2). The year 2007 annual report was missing from the records and could not be used for the research. However, the time span of almost 15 years was considered to give wide enough perspective Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  V. ISOHERRANEN ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 579 Table 2. Strategy typology characteristics summary (adapted from Gallen [21]). Strategy type/Dimension Defender Prospector Analyzer Reactor Product–market domain Narrow and stable Broad and continuously expanding Segmented and carefully adjusted Not clearly defined Operational driver Cost-efficiency Flexibility and innovativeness Technological synergy Inconsistent and not optimized Organization Functional and line authority Products and/or market oriented Matrix oriented Independent business units with loose connections Table 3. Analysis framework. Strategy typology Strategy orientation Defender Prospector Analyzer Reactor Market orientation Strategy focus: -Delivering most suitable product for the customer Product-Market domain: -Narrow and stable Value Creation: -Customer value Operational Driver: -Cost-efficiency -Customer information Culture: -Long-term proactive drive to understand customer needs Organization: -Functional and line au- thority Strategy focus: -Delivering most suitable product for the customer Product-Market domain: -Broad and continuously expanding Value Creation: -Customer value Operational Driver: -Flexibility and innova- tiveness -Customer information Culture: -Long-term proactive drive to understand customer needs Organization: -Market oriented Strategy focus: -Delivering most suitable product for the customer Product-Market domain: -Segmented and carefully ad- justed Value Creation: -Customer value Operational Driver: -Technological synergy -Customer information Culture: -Long-term proactive drive to understand customer needs Organization: -Matrix oriented Strategy focus: -Delivering most suitable product for the customer Product-Market domain: -Not clearly defined Value Creation: -Customer value Operational Driver: -Inconsistent and not optimized -Customer information Culture: -Long-term proactive drive to understand customer needs Organization: -Independent business units with loose connections Product orientation Strategy focus: -Creating the best product Product-Market domain: -Narrow and stable Value Creation: -New features and applications Operational Driver: -Cost-efficiency -Creating portfolio of products Culture: -Inward-focused, ‘core competences’ Organization: -Functional and line authority Strategy focus: -Creating the best product Product-Market domain: -Broad and continuously expanding Value Creation: -New features and applications Operational Driver: -Flexibility and innova- tiveness -Creating portfolio of prod- ucts Culture: -Inward-focused, ‘core competences’ Organization: -Products oriented Strategy focus: -Creating the best product Product-Market domain: -Segmented and carefully ad- justed Value Creation: -New features and applications Operational Driver: -Technological synergy -Creating portfolio of products Culture: -Inward-focused, ‘core competences’ Organization: -Matrix oriented Strategy focus: -Creating the best product Product-Market domain: -Not clearly defined Value Creation: -New features and applications Operational Driver: -Inconsistent and not optimized -Creating portfolio of products Culture: -Inward-focused, ‘core competences’ Organization: -Independent business units with loose connections  V. ISOHERRANEN ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 580 Figure 1. The research process. to the research. The annual reports were available in electronic format on English language. The created strategy orientation and typology frame- work was then used to analyze the empirical case data of both of the case businesses. The analysis was conducted in four parts for the first case business (mobile phones case business). The phase’s selection and timing was based on the analysis done in the previous research. For the second case company the analysis was conducted similarly using the framework but looking the data to find logical points when there was strategy focus change. 3.2. Results and Analysis The mobile phone case business strategy during the 1990 to 1994 can be categorized as product oriented prospe- ctor. The strategy focus during this period is to create best product for the new market. This new market is cre- ated by the Global system for Mobile Communications (GSM) standard, the new digital communications stan- dard. The case business is one of the first ones to pursuit this new product-market domain created by technology advancement in wireless communication, thus the value creation channel is to be able to create new applications to for this new technology. The operational driver is to invest on research and development activities, so that new market opportunities can be exploited on full scale. The product orientated strategy drives focus on internal capabilities development, together with securing enough productization capacity. This organization product ori- ented focus can be seen by establishment of new research and development sites. The period of 1995-2000 the mobile phone case busi- ness continues to have the characteristics of product ori- ented prospector in the strategy according to the analysis framework criteria. The case business strategy focus and operational driver is on creation of broad portfolio of products with the most advanced features. Focus is on creation of the best product with the latest industrial de- sign. The case business is involved in several technology areas, and drives to create efficient product creation ca- pabilities. The product market domain is being con- stantly expanded by finding new segments of customers to serve. Thus the drive from strategy point of view is to find as many customers as possible for the products the case business is creating. During the period of 2001 to 2006 the mobile phone case business strategy can be categorized as product oriented defender. The case business has established its position as market leader, and it is strategy has focused on to protect its position. Case business has established product business unit to achieve economies of scale to its product creation and delivery. During this examined pe- riod the case business launches on several consecutive years over 40 new mobile phone models, thus aiming to create widest portfolio of products in the industry. These new models contain the latest features, form factors, such as computer like keyboard for messaging and digital camera capabilities. The period of 2007 to 2009 the case business can be defined as market oriented analyzer. During this last analysis period there can be noted significant change in the case business strategy. The case business is searching for new market areas while maintaining its position on the current market it operates. The product-market do- main is carefully adjusted and case business operates in matrix mode organization. There are indications from the strategy point of view to get closer to customers, and establishing specific solutions unit to serve the needs of customers to get the most suitable product. Similarly, the strategic customization efforts are raising their priority as well has customer information collection. The second case company follows the strategy of pro- duct oriented analyzer during the years 1994 to 2000. The drive is within this period to go for the position of leading sports equipment manufacturer in the world. To achieve this target the case company consistently divests in the selected existing business areas, such as car and forklift importing. In the other hand, case company pur- suits new business area opportunities by organic growth and most importantly acquisitions of several companies. The existing business is kept in good condition, support- ing the financial operations needed for the new business domains search. In these existing business areas, focus is to maintain efficient production and operations. The new business domains acquired during this timeframe are e.g. Atomic, the ski equipment manufacturer, Suunto and DeMarini. All of the acquisitions broaden the product portfolio of the case business. The case business strategy shows during this timeframe considerable focus on the products. The innovation within research and develop- ment is focused on improving the existing capabilities of  V. ISOHERRANEN ET AL.581 the products and also to create new technological solu- tions to be able to broaden the product portfolio. Impro- vements to products characteristics are searched from new material compositions or design of the products. World know brands play essential role in the efforts to achieve broad and widely known product portfolio. During the period from 2000 to 2008 the case com- pany strategy can be categorized as product oriented defender. During this period the case company achieves the position of leading sports equipment manufacturer in world. This is supported by strong financial position. The position is defended by creation of wide product portfo- lio, which is build from summer and winter sports, and also from outdoor to indoor sports equipment products. This is aimed to protect the company against seasonality, and other sudden causes for volatility e.g. weather condi- tions. Case company focuses on building long term rela- tionships with retail and distribution, and making sure that the supply chain operations are efficient, thus sup- porting the leading position of the company. Integrated and transparent supply chain management aims to cost efficiency. The narrow definition of the target product- market domain also supports the thinking of the strong focus on the core competences and building unbeatable position within this segment/product domain. Case com- pany also continues acquisitions to further focus on the core business area of sports equipments and divest from the original business area of tobacco license manufac- turer. Case company does significant reorganizations and searches for efficient cost position to secure the competi- tiveness, and making the business domain hard to enter for any new competition. 4. Managerial Implications The strategy analysis framework (Table 3) build from literature references combines the two dominating di- mensions in the current strategy thinking: the market based (demand based) strategies and the product based strategies with the Miles et al. [10] presented strategy typology. Examples of the market based strategies can be found from the thinking of Porter [4] (differentiation or cost leadership) and the thinking of Hamel and Prahalad [5] (core competences) presents good example of the product-based strategies. It is evident that the first of all that companies are pursuing with their strategy work sustainable competitive advantage. The roadmap to this can be based on either on the competences which the company has or it can analyze the market to find such market segment or even single customer which the com- pany focuses, so that it will be the best company to serve that segment or customers needs, thus building special position for itself. The framework build in this study can help outsider observer to dissect the examined company’s strategy. This “dissection” can give the fundamental information to understand the strategy orientation within the exam- ined firm. Secondly the orientation knowledge together with the strategy typology can help to position the ex- amined company in the strategy continuum to defensive (Defender) or aggressive (Prospector) position. Also the potential failures in strategy execution can be acknow- ledged (Reactor). The strategy orientation analysis framework fitted to Miles et al. [10] strategy typology enables managers re- sponsible of strategy development to analyze their com- pany’s position in the demand-based or product-based domains and mirroring this positioning to the strategy typology types. Also important applications for the strategy analysis framework, used by the strategy managers are to under- stand the competitors’ strategy orientations together with their typology characteristics. If one company follows the product-oriented defender strategy in markets where the main competitor is pursuing market-oriented pro- spector strategy, first one can assume aggressive cus- tomer targeting and acquisition from the competitor side. It is however notable that defender, prospector and analyzer strategies can all be successful in the market place, however in markets which are constantly changing and e.g. new technologies cause interruptions, the lack of market understanding can lead the company to be slow on response to changing customer demand or to new customer requirements. 5. Conclusions The purpose of this study was to build analysis frame- work for two dimensional strategy orientation fitted to- gether with the strategy typology, both parts based on literature references, and then the framework was tested with two case businesses strategy evaluations. The research questions were stated to be following: RQ1: What is the framework to analyze strategy ori- entation with strategy typology? RQ2: How does the case businesses strategy orienta- tion and typology change? Answering to research questions: RQ1: The framework to analyze the strategy orienta- tion with the strategy typology is presented in the Table 3. RQ2: The case businesses strategy orientation and ty- pology change is summarized in the Table 4 and Table 5. The findings show the mobile phone case business mov- ing from product oriented prospector position to product oriented defender and then by the end of the period to the Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  V. ISOHERRANEN ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 582 Table 4. Mobile case business strategy analysis summary for examined periods. Strategy typology Strategy Orientation Defender Prospector Analyzer Reactor Market Orientation 4th period: 2007 - 2009 Product orientation 3rd period: 2001 - 2006 1st period: 1990 - 1994 2nd period: 1995 - 2000 Table 5. 2nd Case company strategy analysis summary. Strategy typology Strategy Orientation Defender Prospector Analyzer Reactor Market Orientation Product orientation 2nd period: 2000 - 2008 1st period: 1994 - 2000 position of market oriented analyzer. The second case company strategy in the examined timeframe starts from the position of product oriented analyzer the moving more and more to the position of product oriented de- fender. As conclusion from both of the case businesses results can be stated that the created strategy analysis frame- work (Table 3) is able to detect strategy change in both of the case businesses strategy The limitations of this research are originated from the definitions of analysis framework dimensions. Also the empirical material of both of the cases businesses has limitations due to its nature, as it gives overview on the examined period but many detailed or fine scale nota- tions cannot be examined in further details. The areas for further research can include the frame- work testing in case businesses from different industrial areas, such as business to business markets or in the highly regulated markets. Overall the product and market orientation as source of competitive advantage are inter- esting area for further research 6. References [1] R. C. Whiteley, “The Customer Driven Company: Mov- ing from Talk to Action,” Perseus Books Group, New York, 1991. [2] H. Thompson, “The Customer-Centered Enterprise,” McGraw-Hill, New York, 2000. [3] J. Galbraith, “Organizing to Deliver Solutions,” Organ- izational Dynamics, 2002, pp. 2-19. [4] M. E. Porter, “Competitive Advantage,” The Free Press, New York, 1985. [5] G. Hamel and C. K. Prahalad, “Competing for the Fu- ture,” Harward School Press, Boston, 1994. [6] G. A. Moore, “Living on the Fault Line,” Harper Busi- ness, New York, 2000. [7] W. C. Kim and R. Mauborgne, “Blue Ocean Strategy,” Harvard Business School Press, Boston, 2005. [8] S. F. Slater and J. C. Narver, “Customer-Led and Mar- ket-Oriented: Let’s Not Confuse the Two,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 19, No. 10, 1998, pp. 1001- 1006. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199810)19:10<1001::AID- SMJ996>3.0.CO;2-4 [9] G. S. Day, “The Capabilities of Market Driven Organiza- tions,” Journal of Marketing, Vol. 58, No. 4, 1994, pp. 37-52. doi:10.2307/1251915 [10] R. E. Miles, C. C. Snow, A. D. Meyer and H. J. Coleman, “Organizational Strategy, Structure and Process” The academy of Management Review, Vol. 3, 1978, pp. 546-562. [11] Y. Doz and M. Kosonen, “Fast Strategy: How Strategic Agility Will Help You Stay Ahead of the Game,” Whar- ton School Publishing, Philadelphia, 2008. [12] K. Dittrich and G. Duysters, “Networking as a Means of Strategy Change: The Case of Open Innovation in the Mobile Telephony,” The Journal of Product Innovation Management, Vol. 24, No. 6, 2007, pp. 510-521. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5885.2007.00268.x [13] M. Häikiö, “Nokia the Inside Story,” Opiske-lijakirjaston Verkkojulkaisu, Helsinki, 2002. [14] D. Steinbock, “The Nokia Revolution: The Story of an Extraordinary Company that Transformed an Industry,” AMACOM, New York, 2001. [15] A. Brem and K.-I. Voigt, “Integration of Market Pull and Technology Push in the Corporate Front End Innovation Management-Insights from the German Software Indus- try,” Technovation Science Direct, Vol. 29, No. 5, 2009, pp. 351-367. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2008.06.003 [16] G. S. Day, “What does It Mean to be Market-Driven?” Business Strategy Review, Vol. 9, No. 1, 1998, pp. 1-14. doi:10.1111/1467-8616.00051 [17] M. D. Hartline, J. G. Maxham and D. O. McKee, “Corri- dors of Influence in the Dissemination of Customer-Ori- Ented Strategy to Customer Contact Service Employees,” Journal of Marketing, Vol. 64, 2000, pp. 35-50. doi:10.1509/jmkg.64.2.35.18001 [18] S. F. Slater and J. C. Narver, “Market Orientation and the Learning Organization,” The Journal of Marketing, Vol. 59, No. 3, 1995, pp. 63-74. doi:10.2307/1252120 [19] J. R. Galbraith, “Designing the Customer-Centric Or- ganization,” Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, 2005, p. 184. [20] R. E. Miles and C. C. Snow, “Organizational Strategy, Structure and Process” The academy of Management Re- view, Vol. 3, pp. 546-562. [21] T. Gallen, “Personality and Strategy,” Acta Wasaensia, Vaasa, 2010, p. 110.  V. ISOHERRANEN ET AL.583 Appendix 1 1st case business Number of pages Year Annual report CEO’s/Board of Directors report 1990 72 2 1991 64 2 1992 64 2 1993 64 2 1994 71 2 1995 72 2 1996 76 3 1997 80 2 1998 56 2 1999 52 2 2000 42 4 2001 56 4 2002 66 3 2003 70 3 2004 78 3 2005 83 3 2006 87 5 2007 86 5 2008 89 5 2009 98 5 TOTAL 1426 61 Appendix 2 2nd case company Number of pages Year Annual report CEO’s/Board of Directors report 1994 43 5 1995 42 6 1996 42 7 1997 50 7 1998 56 4 1999 52 3 2000 56 5 2001 56 4 2002 60 5 2003 76 4 2004 85 6 2005 107 8 2006 112 10 2008 154 6 TOTAL 991 80 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME |