Modern Economy, 2011, 2, 498-513 doi:10.4236/me.2011.24055 Published Online September 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/me) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME The Effects of European Austerity Programmes on Social Security Systems Arne Heise, Hanna Lierse University of Hamburg, Hamburg, German E-mail: arne.heise@wiso.uni-hamburg.de Received March 14, 2011; revised May 5, 2011; accepted May 18, 2011 Abstract The recent financial and economic crisis is intensifying the pressure for budget consolidation,increasing the likelihood of cuts in social services throughout Europe. One government after another is bringing forward a budget consolidation programme. Cuts are envisaged above all in social services and so the question arises of what effects this will have on welfare states in EU member countries and on Social Europe in general. In this study cuts in social systems are analysed and compared, both planned and already undertaken. Regardless of the different magnitudes of the austerity efforts and the policy fields concerned there can be no doubt that all austerity programmes are regressive in nature and that the option of raising incomes is being exercised far less frequently than spending cuts and this applies especially in the social realm. Keywords: European Integration, Social Policy, Budget Consolidation 1. Introduction It is an open secret that the welfare state has become a basket case and must therefore be reformed or at least reconstructed and modernised. Globalisation and Euro- pean integration, demographic change and individualisa- tion processes in society have, slowly but surely, eroded the welfare state foundations of EU member states. If the renovation work does not start soon, according to the conventional wisdom, the welfare state will collapse un- der the weight of its costs and the burden of redistribu- tion. What has been the mainstream perspective on social policy in economics as well as in politics over the past two decades, may become another TINA (there is no alternative) imperative in the aftermath of the recent world financial crisis and the ensuing ‘absurd austerity policies’ [1] almost everywhere in Europe. Before we turn to the development trends of European welfare states the European Social Model in particular under conditions of the general need for consolidation in the face of soaring public debt due to the recent global financial crisis in six European countries (part 2), first a few taxonomical remarks (part 1) will be made. After a comparison of the austerity programmes (part 3) a short conclusion (part 4) tries to take up the lines of discussion addressed in the first part. 1.1. A Taxonomy In general usage, but also in the social science literature, the terms social state (Sozialstaat) and welfare state (Wohlfahrtsstaat) are virtually synonymous. By contrast, we shall use the term welfare state only when state in- tervention involves, not just social adjustment or social protection but broader social and economic policy change to increase societal welfare. Social policy in the strict sense is to be reserved for protection against the five basic life risks old age, illness, unemployment, ac- cident and poverty and social state refers to this core. Welfare state policy, by contrast, requires, besides the instruments of social policy in the strict sense, collec- tively determined and democratically legitimised objec- tives (for example, the degree of redistribution, possible limits to be imposed on the market or a willingness to pursue decommodification) and a broad-based embed- ding of social policy, ranging from macroeconomic con- trol through family policy to education policy as the ba- sis of participation and inclusion which is not exclusively market-oriented. Within the framework of this distinction we shall be concerned here only with the social state in the EU and the European Social Model will refer precisely to that not the welfare state in the broader sense. This is owing, on  A. HEISE ET AL.499 the one hand, to a necessary limitation of the object of investigation, while at the same time reflecting the abovementioned change of perspective with regard to the allocation of social policy tasks after the end of the Keynesian welfare state. Three objective processes globalisation/European integration individualisation population ageing have led, against the background of the neoliberalism which has dominated for the past three decades, to social policy being understood almost exclusively in supply- side terms as a distortion of allocation due to adverse incentives. In this view, the collective redistributive con- tent of social policy justifiable in demand-side terms needed to be scaled back in favour of greater individual equivalence and, where possible, provided privately so that both in supply-side terms and as regards competi- tiveness the greatest possible efficiency and financial sustainability (economisation) would be ensured. It will also be demonstrated by means of the distinc- tion between welfare state and social state that the out- come of the social policy modernisation efforts will not be the end of the social state, but does involve a clear-cut change in its substantive arrangements, the balance be- tween collective and individual contributions, funding and also benefit eligibility and legitimacy. In this sense the former contrast between Europe, with its developed welfare states, and the USA, with its limited social state, is brought out more clearly. And if one takes the devel- opment outlined above into account, it is obvious why [2] no longer recognises any systematic difference between Europe and the USA which would justify a special em- phasis on a European Social Model. 1.2. Different Models of the Social State in the EU European social states have not only developed fairly disparately in historical terms, but they also correspond to the variety of European economic models [3]. This relates to the extent of the provision of social security, the level of decommodification, the manner of funding, the structural allocation of social security needs in terms of the various exigencies and their institutionalisation. According to the well-known categorisation by [4] we can therefore distinguish between at least three types of social state in the EU: 1) the social democratic or Scandinavian type 2) the social conservative or continental type 3) the liberal or Anglo-Saxon type With eastern enlargement this variety is likely to have increased [5]: for the time being, therefore, one cannot talk of one or the European Social Model. To be sure, the abovementioned transformation and modernisation pro- cess of the various social states in the EU may converge into a common model; on the other hand, the European Social Model can also serve as an ideal model for a (new?) mode of integration capable of distinguishing itself more clearly again from the US model. 1.3. Related Work: European Integration as Engine of Convergence? The literature on the future development of the social state in the EU is voluminous and inconclusive [6-8]. Although the abovementioned objective factors and, in particular, the requirements of European integration af- fect all member states, national adaptation paths can vary considerably: on the one hand, one may agree with [9] who, against the background of neoliberal ideologising and the EU integration architecture, take the view that only the liberal model is capable of surviving and, there- fore, predict a corresponding convergence; on the other hand, however, one might share [3] assessment that not only is the social state model shaped by the underlying economic model, but also the relevant modernisation and adaptation paths are fitted to the economic model and, consequently, divergences will remain and, at best, over the long term various hybrid models will emerge. To some extent between these positions lies [5] and [10] who claims to recognise a convergence towards a hybrid model in the system of competitive market states which is the result of the EU’s neoliberal architecture (see also [11]) which takes account of the fact that social systems have become significant factors in competitiveness, in particular in the single currency area (that is, EMU). Within the framework of the method of open coordina- tion the soft form of governance which characterises EU social policy forms of recommodification, privatisation and cuts in social security may be discerned practically everywhere. There is no room here to go into detail concerning the individual structural features of the putative convergence process. Ultimately, however, economisation is tied up with a scaling back of the level of social security with a view to reducing alleged problems of allocation and competitiveness. If one looks at the relative social spend- ing of various countries representing different models (Figure 1), however, a general downward spiral of levels of social security is not apparent.1 Some member states, regardless of their social security model (France as an example of the continental model, Denmark as an example of the Scandinavian model and 1Certainly, it should not be overlooked that a constant rate of social spending does not necessarily mean a constant level of social security if the number of benefit recipients increases due to population ageing, risin overt or unem lo ment. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  A. HEISE ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 500 Figure 1. Social Spending as a Percentage of GDP (1980-2005). Source: OECD, Country statistical profiles 2009. Poland as representative of the CEE countries), even register increasing social spending rates and only in a few countries for example, Ireland as representative of the liberal model, Slovakia as representative of the CEE states and Sweden as representative of the Scandinavian model is there a falling trend with regard to social spending rates, and in all cases in terms of a more up- to-date time horizon stagnation can be discerned rather than a clear (downward) trend. If, therefore, convergence towards a generalisable European Social Model is to be linked to serious endan- germent of social achievements in the EU other evidence has to be produced. In Figures 2(a) and 2(b), therefore, not only the development of social spending rates is taken into account but also the state of development of the national economy (GDP per capita). Social security, after all, is a public good demand for which on the part of consumers (citizens) increases with rising incomes (positive income elasticity). It would be evidence of dumping not only if social benefit rates are falling in absolute terms but also if these rates do not correspond to economic development, as long as a positive correlation can be determined between the two. Figures 2(a) and 2(b) identify this correlation at various time points: with regard to 1980 and 1990 we can talk of a high and even increasing correlation coeffi- cient (R-square), regardless of variations in terms of so- cial state models. The level of the rate of social spending is explained, on this basis, by the state of economic de- velopment (57 per cent and 71 per cent, respectively): the increase in the correlation coefficient can be under- stood primarily as a result of the fact that Greece imple- mented an above-average increase in social spending after EU accession and sought to adapt to Europe’s (ma- terial) development path. The picture changes, however, when we look at 2000 and 2005: now the close correla- tion is largely dissolved only around 16 - 17 per cent of social spending can be explained on the basis of the state of development of member states’ economies. Responsi- ble for this is at least relative dumping in countries of the liberal (Ireland) and CEE (Slovakia) type which did not develop their social states in accordance with their grow- ing economies, but countries of the continental type (the Netherlands), too, contributed by scaling back their so- cial states to making social policy in the EU increas- ingly a location and competitiveness factor. 1.4. The European Social Model under Pressure The developments in social states depend on a variety of real political power constellations; they do not depend on economic-functional or ideological considerations alone. Despite numerous objective and subjective negative fac- tors the European modernisation process is not simply a matter of a race to the bottom with regard to social stan- dards. On the other hand, the data suggest that the mate- rial development path discernible in the 1980s and 1990s is being abandoned or at least will no longer shape the frame of reference. The bigger the objective negative factors and the change of perspective with regard to the welfare state in the direction of economisation the sooner a corresponding development is to be expected. To that extent it is important whether the European Social Model in particular after the sobering experiences of European political actors with the at least sceptical, if not hostile attitude of EU citizens, which also manifested itself in the failed attempt to obtain agreement on a European Constitution is developed as a positive vision of a social  A. HEISE ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 501 y=2,5486x‐ 2,8022 R²=0,5667 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 0246810 Soci al expenditureas%ofGDP GDPpercapitainppp 12 GR y=1,0574x+5,0211 R²=0,7155 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 0510 15 20 25 Socialexpendituresas%inGDP GDPper capitainppp SWE IRL GR (a) y=0,2581x+16,296 R²=0,1731 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 0510 15 20 25 30 35 Social e xpe ndi tureas%ofGDP GDPpercapitainppp IRL NL SLO  A. HEISE ET AL. 502 y=0,2405x+16,558 R²=0,157 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 0510 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 So ci alexpenditureas %ofGDP GDPpe r capitainppp IRL SL NL (b) Figure 2. (a): Correlation between Social Spending and Per Capita Income (1980 and 1990); (b): Correlation between Social Spending and Per Capita Income (2000 and 2005). Note: The following countries were selected: Germany, France, Netherlands, Denmark, Italy, Greece, Spain, Belgium, Sweden, Austria, Ireland, Slovakia, Czech Republic, Poland. Source: OECD, Country statistical profiles 2009. or welfare state which differs from the US model. The strategy of former Commission President Jacques Delors consisted precisely of this attempt to reduce the social deficit [12] by paying closer attention to the social component. Delors is associated not only with further economic integration within the framework of the single market and monetary union, but also with the shaping of the European Social Model. Delors was convinced that market creating integration measures alone would not be sufficient to overcome the Euro-scepticism of the 1980s (Eurosclerosis); in particular, the increasing incongru- ence of the reach of the market and market regulation threatened to put national social standards under pressure revealing the limits of semi-sovereign nation states [13]. For the socialist Delors, therefore, economic and social integration still presupposed one another and his vision of the European Social Model may still be regarded as a serious attempt to defend Europe’s welfare state tradi- tions and to understand it as a source of legitimation for European integration. Later European Commissions, therefore, must be regarded as important motors of the change of perspective (see, for example, [14-15]). In this way those forces in the European Commission have won through in the struggle over European integration [16] which in the Delors Commission were still kept in check by the white paper Growth, Competitiveness and Em- ployment [17], sometimes described as neo-Keynesian [18]. This occurred, astonishingly, at a time when a window of opportunity was opened up by the coming to power in many and indeed the most important EU mem- ber states of Social Democratic governments for estab- lishing or restoring a genuinely Euro-Keynesian deve- lopment path. The major discord which arose in the German SPD during the first Schröder government with Oskar Lafontaine’s resignation from all Party and gov- ernment posts and the ultimate victory of left-wing sup- ply side politician [19] exemplifies the uncertainty about the future economic and social policy course of Euro- pean social democracy (see [14]) and explains why this window of opportunity soon closed again. It also ex- plains why the European Commission found it easy to assert its ideas on the social investment state and the human capital-oriented and incentive-compatible notion of employability in place of the quantitative (level of) employment as the connotative basis of the European Social Model, as well as the employment policy incor- porated in the Amsterdam Treaty as further source of legitimation. For [15] the Commission has taken advan- tage of ideas which the general public view positively such as the European Social Model and employment policy to enhance the legitimacy and acceptance princi- pally of economic integration, hiding and reinterpreting the economisation of the social behind the apparently familiar. Whether the recent world financial crisis will lead once again to the kind of violent social conflicts through which emancipatory forces will set the agenda and the currently dominant projects will be rejected [20] remains to be seen. Besides the temporary loss of legitimacy of orthodox neoliberal economic and financial ideas at the ideological level [21], at the level of political practice the global financial crisis has, for the time being, imposed an Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  A. HEISE ET AL.503 enormous strain on public-sector budgets. Almost in parallel in 2009 the whole of Europe en- tered a deep depression of a magnitude and extent not seen since the world economic crisis at the beginning of the 1930s. Different from the 1930s, however, has been the level-headed reaction of governments and the posi- tive effects of social security: by means of discretionary economic stimulus packages, far-reaching financial mar- ket stabilisation programmes and socially responsive automatic stabilisers, further destabilisation of the real economy and the complete collapse of the international financial markets have been prevented although with significant consequences for state budgets. Structural new borrowing everywhere has exceeded the level of the balanced budget foreseen by the Stability and Growth Pact and the automatic stabilisers are everywhere adding several percentage points to this. Germany, although af- fected slightly more than average by the financial crisis, is experiencing only mild upheavals. This shows the two faces of Germany’s strong export orientation: the major economic downturn has been countered less by discre- tionary measures [22] than by trust in the competitive- ness of the German economy in the surprisingly strong upswing of, in particular, some emerging countries in 2010. Other countries especially Greece, Spain and the UK have relied more on their own economic stabilisation measures or need more financial resources to stabilise the banks. Everywhere, public debt is rising sharply, thereby can- celling out a decade of albeit modest consolidation. This demonstrates the level of consolidation needed if the debt limit of 60 per cent of GDP laid down in the Stabil- ity and Growth Pact is to be maintained as the measure of sustainable finance policy: only the new accession states, which started out from very low levels of debt in the wake of their social and economic transformations, will manage to keep below the threshold in 2010. But even on the basis of this fact it cannot be called into question that the structural deficits in relation to eco- nomic growth must be cut considerably if a permanent increase in public debt is to be prevented. The perenni- ally sensitive issue for finance policy is whether this is to be achieved through tax rises or tax cuts, or through cuts or increases in (social) consumption or investment. The conventional view that cuts in (in particular social) con- sumption are to be preferred to tax increases is contro- versial, to say the least [23]. 2. The Empirical Study Having concerned ourselves in the previous section with a theoretical reflection on the classification and deve- lopment of social security systems in European countries, in this section we shall take a detailed look at the effects and changes which accompanied the recent economic crisis. In 2009, the member states commenced a fiscal policy exit strategy in order to reduce the public borrowing which had increased enormously since the outbreak of the economic crisis. This exit strategy is supposed to continue beyond the scaling back of economic stimulus packages and to be supported by means of further sav- ings and structural reforms. While the European Com- mission suggests that consolidation measures be imple- mented at the latest in 2011 most states adopted far- reaching cuts and reforms in 2010 and some began the consolidation process as early as 2009. While no EU member state has been spared the need to take consolidation measures, the extent and nature of the measures involved and their effects on social security systems have not yet been examined systematically and comparatively. The analysis which follows constitutes a contribution to that and an attempt to discover whether and how member states’ social security systems have been affected by the cuts and the structural reforms. We shall also evaluate whether the crisis has functioned as a motor of social policy convergence among the member states. Building on the previous theoretical discussion of the development of social security systems in Europe we shall assume that there are both similarities between countries and types of system and specifically national, path-dependent developments with regard to social secu- rity systems. In particular, it is assumed that the crisis has triggered further convergence towards a social in- vestment system which is largely undoing the decom- modification of social policy. In what follows we shall examine in some detail the consolidation programmes of six European countries from 2008 to the end of 2010 as published by their re- spective governments and their effects on social security systems. By the choice of countries we attempted to re- flect the plurality of types of social state in Europe in order to render the results as general as possible: While Germany represents the continental type, the UK repre- sents the liberal model, Greece and Spain the Southern European type, Romania the Central and East European type and Iceland can be assigned, in the broadest sense, to the social democratic model. 2.1. Germany With its Financial Plan up to 2014 and the Federal Budget 2011 the Merkel government laid down the basic pillars of German consolidation policy: by 2014, 80 bil- lion euros are to be saved, representing an annual 0.8 per cent of GDP. In this way by 2013 the deficit limit of the Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  A. HEISE ET AL. 504 Stability and Growth Pact is to be maintained and by 2016 the structural deficit is to be brought down to 0.35 per cent of GDP, as prescribed by the new debt regula- tion in the Constitution. The focus of the German auste- rity package is spending, the idea being to make a start where savings and higher revenues are possible without endangering the growth potential of the economy and the social balance [24]. Nevertheless, the German govern- ment also plans substantial cuts in the social budget, making up more than 30 per cent of the whole consolida- tion programme. This is because sustainable budgetary restructuring can succeed only if this sector also makes a targeted and fair contribution [24]. The conservative-liberal government plans, besides cuts in parental benefits for recipients of so-called un- employment benefit II (which consists of the former unemployment benefit and transfers from the social wel- fare system), to transform statutory benefits into discre- tionary benefits and to abolish subsidies for heating and the state pension contribution for this group. At present, persons receiving unemployment benefit II for a year receive an additional pension entitlement of 2.2 euros a month. Since this sum is insufficient to obtain an ade- quate pension, according to the government, the coalition is now abolishing it completely. Besides these measures, which affect the most needy, the government plans cuts in parental benefits and structural changes in health care policy. Even in the latter two areas, in which it would be possible to incorporate an element of progressive redis- tribution, the government’s consolidation policy is af- fecting those on the lowest incomes. Unlike in most European countries the government in Germany does not adjust old age pensions. However, in previous years the pension level fell due to a number of reforms and the role of private and company pensions increased [25]. Furthermore, the consolidation measures also concerned the health care system [26]: besides drug companies, doctors and hospitals, in particular those with statutory health insurance have to bear the cost of rising health care spending. Under the health care reform of 2011 health insurance companies can levy an additional contribution from members with the professed aim of promoting transparency and competition [27]. However, the contribution is not income-related and can be re- garded as an increase in the flat-rate premium. Given the regressive effects of flat-rate premiums low incomes are comparatively harder hit despite the solidarity sur- charge [28]. The reform also abolishes parity of contri- butions between employers and employees, hitherto a basic principle of German health insurance. The German government’s budget consolidation pro- gramme and the social state reforms are relatively low in terms of GDP in comparison to those of other European countries (see also Table 1). This is certainly because of Germany’s favourable current economic and thus also budgetary development. Despite the relatively low level of restructuring the reforms are clearly directed towards social policy: the measures have affected the neediest in society—safeguarding or reinforcing social benefits for the unemployed and low earners does not come into it. On the contrary, all additional emoluments have been cut in order to boost incentives to get a job and personal re- sponsibility, according to the government. The basic idea of social balance, as advanced by the conservative-liberal coalition, can thus be understood not in terms of social inclusion and ensuring incomes, but rather as a turning away from high social benefits and towards indi- vidual responsibility and private provision. 2.2. Spain With the budget plan for 2010 the Spanish consolidation process commenced with the aim of reducing the deficit to three per cent of GDP by 2013 [29]. However, on top of this package the government ratcheted up its economy drive in the course of the year: besides the austerity plan (2011 - 2013) and the Action Plan (2010) considerable spending cuts were earmarked for the public sector, and the government passed laws on structural reform in the pension system and the labour market, as well as addi- tional economies totalling 15 billion euros [30]. These extensive reforms are supposed to tighten the Spanish budget while boosting economic growth and ensuring basic social care. The Spanish strategy is thus concen- trating on a mixture of spending cuts and revenue in- creases ([29], see also Table 1). With its first consolidation wave, the 2010 budget plan, the government decided to reduce the deficit by 2.1 per cent of GDP, whereby no significant cuts in social ser- vices were envisaged. The government increased VAT, tax on interest and some consumption taxes. In addition, incentives were laid down to stabilise jobs, within the framework of which corporate tax was to be reduced from 25 per cent to 20 per cent for SMEs which maintain or increase their employment rate. On the spending side, the government planned a public sector pay and pension freeze. Substantial reforms and cuts in the Spanish social state were not foreseen. However, the social democratic government implemented additional austerity measures which envisage cuts in the pension system and other ar- eas of social policy. Within the framework of the Strategy for a sustain- able economy and budget position the Spanish govern- ment implemented a number of structural reforms in re- lation to pension and labour market policy [29]. The lat- ter is supposed to introduce more flexibility into wage Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  A. HEISE ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 505 negotiations and employment protection, but at the same- time to reinforce the employment rights of those on tem- porary contracts [31]. The aim is to stabilise the em- ployment situation in Spain, where the main problem is the large proportion of temporary and provisional jobs, accounting for around 30 per cent of all employment contracts, well over the European average of 14 per cent [32]. The lack of employment policy stabilisers un- doubtedly also explains the sharp increase in the unem- ployment rate since the beginning of the economic crisis. The belief that more flexibilisation will contribute to stabilisation may be explained historically: since the end of Francoism neoliberal approaches have had consider- able weight in Spain [33]. The Toledo Pact of 2010, which envisages extensive pension reform and is supposed to achieve cuts to the value of four per cent of GDP by 2030 [34], is also part of the strategy for a sustainable economy and budget position. Pension reform includes measures in accor- dance with the OECD trend [35]: a uniform pension sys- tem has been established, individual equivalence has been reinforced, the retirement age has been raised and the minimum contribution period has been increased from 15 to 25 years. Furthermore, part-time work for those approaching retirement has been temporarily abo- lished and the 2011 pension increase suspended, al- though the social security pension is exempt from the latter two measures [30]. The aim of the reforms is to create incentives for regular and longer payment of pen- sion insurance contributions. However, in particular the strengthening of individual equivalence, which is sup- posed to connect pension levels more closely to contri- butions, leads to pension redistribution: those with low incomes and erratic employment will increasingly re- ceive lower benefits than those with stable and high in- comes. In Spain, where the unemployment rate is cur- rently 20 per cent and the number of temporary contracts is high, this reform can be expected to exacerbate income inequality in old age. The government also plans to abolish the so-called baby cheque and to reduce costs in the health care sector. The baby cheque was introduced by the social de- moc- ratic government in 2007 and entitles parents to a one-off payment of at least 2,500 euros on the birth of a child. From 2011 this non-income related support will be abol- ished. Health care reforms are aimed at reducing costs: the state system entitles every citizen to free health care. However, expenditure on drugs is high in Spain and in- frastructure is poor and out-of-date [36]. The current reforms are aimed in particular at lowering drug costs: savings of 1.5 billion euros a year are to be achieved by reducing the price of generic medicines and introducing price caps. Although the social democratic government is not levying copayments, the state health care system will cover only drug costs which are in line with the new price regulations. The social policy cuts implemented by the Spanish government within the framework of budget consolida- tion are relatively moderate (see also Table 1) since no specific cuts in basic provisions for social insurance re- cipients are envisaged. However, the reforms must be re- garded as predominantly liberal and regressive because the Table 1. Synopsis* of National Austerity Programmes. Austerity programme Germany Estonia Greece UK Romania Iceland % of GDP 3.3*** 8.5** 10.5** 7.2** 13.9* 12*** % of GDP per year 0.8 2 - 3 3 1.8 - 2 7 2.4 Billions, national currency 80€ 2010 - 14 85€ 2010 - 13 24 € 2010 - 13 No data 2010 - 12/13 74.6 Lei 2009 - 10 179 ISK 2009 - 13 1. Revenue increases 33 41.2** 42.9 31 15 36 - Corporate taxes - Income taxes 7.52 / –1.6 / 8.5 / –8.5 –11.563 / / 1.4 32.3 - VAT / 11.4 23.4 44.9 104 4.6 2. Spending cuts 52 58.8 57.1 69 85 64 - Social security5 34 5.4 No data 21.9 No data 15.6 Sources: * Authors’ own calculations, based on various IMF and EU sources, as well as national budget plans. ** EU Public Finances 2010, p. 66. *** Ger- many: Package for the Future 2010 (Zukunftspaket); UK: Budget Plan 2010; Iceland: Financial Plan 2009 - 13. 2Even though no increase in corporate tax was introduced, the German government plans to introduce a transaction tax with projected revenues o around six billion euros, corresponding to around 7.5 per cent of the austerity package. 3In Britain the personal income tax allowance was increased by £1,000 per annum, which is regressive, not progressive in effect. 4Estimates for Romania are particularly difficult because of the lack of public data and the multitude of revisions, since initial consolidation effects were not achieved. However, Romania decided, alongside an increase in VAT from 19 per cent to 24 per cent, only on an extension of personal in- come tax and consumption taxes to medical products. The former will, according to the finance minister, amount to around 3.5–4 billion lei, corre- sponding to around 0.65 per cent of GDP. Total consolidation measures for 2010 amount to 6.5 per cent of GDP, so that 90 per cent of the Romanian ackage consists of cuts and only 10 per cent can be attributed to additional revenues. European Commission estimates confirm this finding [49]. 5Without long-term structural reforms in the health care sector and pension system.  A. HEISE ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 506 abolition of the baby cheque has hit low income families hardest. Pension reform, too, adversely affects in par- ticular those with unstable and irregular work records. Taking into consideration the high unemployment and the instability on the Spanish labour market pension re- form will result in significantly lower earnings for many people. In addition, the Zapatero government is not plan- ning redistributive compensation by taxing higher in- comes or property, so that budget consolidation will predominantly affect families and future pensioners on low and irregular incomes. In order to be able to contex- tualise the reforms within the framework of the overall development of social policy in Spain, in what follows the basic features of the Spanish social state will be ex- amined in more detail. 2.3. Greece The social democratic government is banking on tough austerity measures which will not leave the Greek social security system unscathed. The 2010 Stability Program- me was aimed at reducing the budget deficit within the year by between four and 8.7 per cent [37]. When shortly afterwards at the beginning of 2010 the danger of state bankruptcy reared its head and Greece signed an interna- tional rescue package (see above) the Papandreou gov- ernment passed additional austerity measures in the amount of two per cent of GDP or 4.8 billion euros [38]. The government’s consolidation strategy is comprehen- sive and includes both tax increases and social security cuts (see also Table 1). Although the latter are not the focus of the consolidation measures essential areas such as pension provisions, labour market policy and health care have been substantially affected. Extensive pension reforms were presented to parlia- ment because thus ran the argument only in this way would Greece be able to make its public finances sus- tainable. The costs of pension provisions have risen in recent years from 4.5 per cent of GDP in 2005 to 6.6 per cent of GDP in 2009. According to various prognoses unless the pension system is restructured spending will even exceed 24 per cent of GDP by 2060 [37]. Spending is significantly above the average for European member states which could point to preferential treatment for pension recipients with regard to social spending. How- ever, the non-contribution related social pension, with a basic monthly benefit of 228 euros (2006), is very low and the system is strongly segmented, with major differ- ences between benefit levels, retirement ages and the contribution system. Since the mid-1990s pension reform has been high on the reform agenda, but until the out- break of the crisis there was little to show for it. In July 2010 Parliament assented to this extensive pension reform, which is designed to save three billion euros by 2012. A series of measures are supposed to help to rationalise pension spending and, at the same time, to provide employment incentives by boosting individual contribution equivalence. For example, the retirement age for women and men has been raised to 65 years of age, pension amounts have been adapted to GDP fluctua- tions, early retirement incentives have been abolished, the payment period for the minimum pension has been lengthened and the contribution assessment base has been increased, so that it no longer relates solely to the final years’ income. Privileges for particular groups have been abolished and the number of pension funds has been reduced. In addition, a wage freeze has been im- posed for 2010-2012, holiday bonuses have been reduced and those receiving pensions of over 1,400 euros a month will in future pay extra income tax of up to 10 per cent. The pension reforms are generally in line with those of other OECD states, putting more emphasis on individual contribution equivalence, the living income principle and raising the retirement age [35]. From these reforms it may be expected that state pension benefits will in future be lower and distributed much more un- equally, although the 10 per cent tax on higher pensions will compensate this effect to some extent. The Greek health care system has also been hit by the austerity measures. A reduction in state funded drugs and the introduction of price and cost caps for hospitals are intended to save at least 300 million euros. In contrast to pensions, however, even before the crisis public spend- ing on health care was below that of other EU member states [37]. In addition, the state system introduced in 1983, which is supposed to provide universal access and coverage with regard to health services, early on exhi- bited serious inefficiencies, funding deficits, corruption and discrimination [39]. To what extent the planned re- forms will rectify these problems remains unclear. In response to public budgetary difficulties the Greek government reformed the pension and health care sys- tems and stepped up its existing activating labour market policy. The pension and health care reforms are designed to boost the incentives with regard to normal employ- ment. Both the pension reform, which has reinforced individual contribution equivalence, and the employment policy orientation more strongly emphasise incentives, with not much of a role for redistribution and income stabilisation. However, the social democratic government shied away from explicit cuts in social benefits and im- posed extra taxes on higher pensions, as well as one-off payments on high profit rates and expensive real estate. The social policy reforms fit in the paradigm of the so- cial investment welfare state, which focuses less on re- distribution and income guarantees and more on incen-  A. HEISE ET AL.507 tives towards labour market participation. However, the Greek austerity programme and social policy cuts which have affected unemployment benefit recipients and low earners appear to be relatively moderate (see also Section 3, Table 1). 2.4. Iceland In July 2009 the Left-Green government presented its budget consolidation package, which amounts to 179 billion krona or 12 per cent of GDP, covering a period of five years. This represents a significant moderation of the programme of the preceding conservative government, which planned cuts amounting to 16 per cent of GDP [40]. In the period 2009 - 2013, 35 billion krona (around 1.17 billion euros) are to be saved annually, or 2.4 per cent of GDP. The measures are all-embracing and in- clude both spending cuts and tax increases, aimed at achieving a positive primary balance in 2011 and posi- tive net lending/borrowing in 2013 [41]. Although the government takes the view that, given the continuing recession, tax increases would do less damage to econo- mic growth, spending cuts account for the largest share of the consolidation package, at 64 percent [40]. On the revenue side, the Icelandic government has adopted extensive reforms. In July 2009, it increased so- cial insurance contributions from 5.34 per cent to seven percent, raised VAT by half a percentage point, in- creased a number of consumption taxes and the capital levy on yields of over 250,000 krona from 10 per cent to 15 per cent, and introduced a temporary supplementary tax on monthly incomes above 700,000 krona (around 4,600 euros) [42]. An increase in corporation tax is also planned, which at present stands at only 18 per cent. These tax policy measures are progressive since the go- vernment, besides tax rises across the board, is making those on higher incomes pay more. On the expenditure side, too, the Left-Green govern- ment has tried to avoid imposing a disproportionate bur- den and cuts in living standards on those on low incomes. Despite this approach, however, Iceland has not been spared social cuts: particularly hard hit have been old age and invalidity pensions, as well as health insurance and child benefit. Cuts in these areas are intended to reduce spending by around 10 billion krona before the end of 2010, although minimum payments are not affected but rather those benefitting from universal benefits despite higher incomes. The current policy approach, which leaves low in- comes untouched, represents a move away from previous social policy reforms in Iceland. In the 1990s, Iceland increased the proportion of individual user funding of public services, as well as the link between individual benefit payments and benefits. In the pension system, besides the state and company pensions, an additional private provision was introduced and tied to tax policy incentives. The basic pension, which originally was in- dependent of earnings, was adapted to individual pay- ments. The current pension reform partly severs the link between contributions and claims. Earnings in addition to the basic state pension have been cut: in future, earn- ings from employment and other pension funds that are above 10,000 krona will be credited against the basic pension. As income increases, therefore, benefits will be cut back and from an income of four million krona a year completely abolished. The Icelandic measures thereby represent a deviation from the OECD trend, which em- phasises the correlation between individual contributions and claims. The consolidation package also affects the national health care system which, as in most Nordic states, is largely organised by the state. Health care costs in Ice- land are traditionally significantly higher than the EU average, because the system is extensive. However, since the 1990s there has been a move away from universal and free services in this area. Access to free health care has been restricted, fees introduced for all services and co-payments for drugs increased [43]. The current health care reforms are in line with these developments: co- payments for medicines have been raised in order to boost demand for generic drugs, with a view to reducing costs by 10 per cent. Much like in the pension system, basic care is maintained by means of free generic drugs. However, this development could also lead to social di- vision in the sense that only a few will be able to afford some special drugs. Besides pensions and health care costs child benefits and parental benefits have also been affected by the aus- terity measures. While child benefit is at present paid to families with children below six years of age regardless of income, from now on benefits will be at least partly income-related, with the aim of saving one billion krona. In addition, the government is cutting parental benefit which has an income replacement rate of 80 per cent and at present may amount to a maximum 400,000 krona a month. Within the framework of the austerity package the highest payment is being reduced to 350,000 krona a month, so that in particular higher and medium incomes are affected by this measure. Parents who earn less than 437,500 krona (around 2,900 euros) will continue to re- ceive 80 per cent of their income. The government esti- mates that this measure will save 70 million krona and adversely affect 15 per cent of parents (30 per cent of men and 10 per cent of women). Much the same as with regard to pensions and health care these reforms repre- sent a move away from universal provisions and put the emphasis on means-tested payments. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  A. HEISE ET AL. 508 The austerity package of Iceland’s Left-Green coali- tion is predominantly progressive and aimed at prevent- ing growing income inequality. The government has re- duced benefits primarily for those on higher incomes, while low earners remain untouched. Benefits are there- fore reduced as income increases and pensions have been completely abolished for those with incomes above four million krona a year [41]. This means that, although there has been a move away from non-income related benefits, minimum benefits and the living standards of those on low incomes are ensured. 2.5. Romania The Romanian government started to implement its strict austerity plan in 2009. The budget envisaged an increase in social contributions of 3.3 per cent, as well as cuts in public sector wages and jobs. On the approval of the in- ternational loan in May 2009 Romania adopted the first consolidation programme. Since one year later it was evident that, despite the reforms, the agreed deficit target would not be reached the government passed another austerity package. This provides for deep cuts in the Romanian welfare state, with sweeping cuts of 15 per cent in all social transfers and of 25 per cent in public sector wages in order to bring about a structurally ba- lanced budget by 2014. The government’s approach is based mainly on cuts; with an increase in tax revenues not envisaged for the time being (see also Table 1). In order to reach its budget policy targets the Romanian government planned, in the first rounds of cuts, the introduction of a law on standard pensions, as well as a uniform payment sys- tem. While the latter relies on the standardisation and effi- ciency of public sector pay, the former concerns com- prehensive pension reform. Pension reform is to be im- plemented in 2011 and is intended to reduce the budget deficit by up to four per cent over the long term [44]. Pension reform encompasses a number of measures aimed at reducing costs over the long term. To this end the retirement age is being raised to 65 and standardised for men and women; the minimum contribution period is being increased; and the assessment base is being ex- tended among others to freelancers and the public sector. In addition, pensions are being tied to inflation, which over the long term will yield considerable savings be- cause adjustment will increasingly be oriented towards consumer prices and less to increases in income. In fu- ture, pension levels will be calculated also on the basis of total contributions and no longer on earnings in the final years of insurance. These measures are supposed to es- tablish an incentive to remain in employment longer and more constantly. However, they will also lead to lower pensions, especially for those with irregular contribution records. Besides re-orientating the state pension system the Romanian government is set on bringing the private pension system to the fore. Since 2007, people have in- creasingly been turning to private and capital funded provisions. On 6 May 2010 Finance Minister Basescu announced the consolidation measures, justifying them by saying that the payment of the next IMF loan depended on them. While it is true that the IMF demanded further budgetary consolidation to the value of 2.3 per cent of GDP in 2010 there were no specific guidelines concerning the shape restructuring was supposed to take. Within the frame- work of the second austerity package, however, drastic cuts in the social budget and in the public sector are to the fore. The government resolved on wage cuts of 25 per cent in the public sector and cuts in all social trans- fers of 15 per cent. While sweeping reductions in pen- sions were halted by the Constitutional Court, the other areas, such as unemployment benefits and parental bene- fits, are affected by these deep cuts. However, the mea- sures do not include minimum payments and thus do not protect those most in need. While the Romanian consolidation strategy is based on massive economies virtually no tax increases are planned. Although the government raised VAT from 19 per cent to 24 per cent in July 2010 it was an emergency measure after the planned pension cuts of 15 per cent had been declared unconstitutional. Apart from that no additional taxes are being levied and the government does not en- visage redistribution by means of property and inheri- tance taxes or the taxation of gains from foreign ex- change and speculation. The government’s strict auste- rity plan thus affects, besides the public sector, in par- ticular pensioners, families and social benefit recipients. However, there is no differentiation between income groups; the across-the-board cuts will leave those on low incomes comparatively worse off. The Romanian government’s reforms represent a re- gressive policy approach in which high and stable in- comes are spared. While the consolidation package af- fects all benefit recipients high-income and wealthy strata are exempted from collective responsibility for correcting the budget deficit. Naturally, they are affected by the VAT increase, but apart from that they do not really have to share the costs of the government’s mea- sures. Socially vulnerable groups therefore not just rela- tively but also nominally have to bear more of the burden of budget restructuring. The Romanian government’s austerity plan can therefore be considered a renunciation by the state of redistributive and social policy goals. 2.6. United Kingdom The guiding principles of the Conservative-Liberal coali- Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  A. HEISE ET AL.509 tion’s austerity programme are personal responsibility and freedom. The five-year plan is aimed at eliminating the structural deficit by 2014 - 2015 and reducing net bor- rowing from 11.4 per cent to 1.1 per cent in the fis- cal year 2015 - 2016. Besides introducing a banking tax and raising VAT and capital taxation, the government plans to reduce the debt primarily through cuts: by 2015, 77 per cent of the consolidation programme is to be achi- eved through spending cuts [45]. The budgets of almost every ministry are being cut, half a million public sector jobs are being eliminated, British people will have to work longer and social spending, as well as welfare fraud and misuse are to be reduced. The aim of the British welfare reforms is to heighten the responsibility of the individual and to reinforce the incentives to take up regular employment (subject to social insurance contributions, known as national in- surance) by way of sanctions and benefit reductions, so that work always pays [46]. The government measures are comprehensive and affect pensioners, single parents, welfare benefit recipients and families. A switch from the retail price index to the consumer price index is to be introduced for the calculation of all benefits. The extent to which benefit recipients will lose out as a result of this switch is disputed. Some studies show, however, that it corresponds to a reduction in benefits and will provide the state with savings of around 5.8 billion pounds in 2014 - 2015 [47]. Besides the reorientation of pension indexation the Conservative-Liberal coalition decided to raise the re- tirement age again and to eliminate tax relief on pensions over 130,000 pounds a year. While the limitation of tax relief affects only higher pensions the change in indexa- tion, which could be accompanied by a lowering of pen- sions in general, affects in particular the recipients of state pensions. A characteristic feature of the British pension system is the importance of private and company pensions, since the flat-rate state pension is not enough to cover basic needs [48]. Pensioners who have no other income are therefore dependent on other benefits. How- ever, within the framework of the consolidation strategy complementary benefits, such as housing benefit and child benefit, are being cut. Housing benefit, which currently stands at 50 per cent of the rent, is being reduced by the coalition to 30 per cent. That means that recipients of this benefit can only choose the cheapest housing in their area. In addition, a general maximum payment is being introduced inde- pendent of local rents, with a view to saving 4.2 billion pounds over the next five years. The government also plans to restructure child benefit, linking benefits more closely to need. While child benefit, which is not in- come-related, is being cut, the government is boosting child credits, which are means-tested. This means that over the next few years increases in child benefit will be postponed and abolished for families on higher incomes from 2013. This is in line with the key values of the British welfare state, which traditionally emphasises benefits for the poorest and for children. In addition, sin- gle parents with children over five years of age can no longer obtain income support but in future will have to register as unemployed: this measure is intended to in- crease employment incentives for this group. Besides the tax increases and welfare reforms the British government also plans to raise the personal tax allowance for all by 1,000 pounds. While the cuts affect benefit recipients most of all, those on higher incomes benefit most from this measure. The Institute for Finan- cial Studies [47] therefore describes the British austerity programme as regressive, the biggest losers from the Conservative-Liberal reforms being benefit recipients. In contrast, those without children and on higher incomes are the biggest winners since they are not affected by the reforms and benefit from the raising of the tax allowance. Although the austerity package is certainly comprehen- sive and means severe cuts for some groups the reforms do not represent a complete reorientation of the British welfare system, but in many respects rather the consoli- dation of the existing model. 3. A Comparison of the Austerity Programmes Table 1 summarises the findings of country studies and presents the sums involved in the various consolidation programmes in relation to GDP and in billions of the national currency. While Romania adopted a package worth almost 14 per cent of GDP, the German austerity programme amounts to a mere 3.3 per cent of GDP. In order to develop a solid basis for inter-state comparison it makes sense to compare the various austerity plans in relation to annual GDP. Romania with an annual con- solidation effect of seven per cent of GDP is at the top, followed by Greece with five per cent. In contrast, the package of the German conservative-liberal coalition, at 0.8 per cent, lies at the bottom end, and the Spanish and Icelandic programmes are also relatively low. The mag- nitudes of the consolidation programmes therefore vary considerably. The differences can be traced back to, among things, the various effects of the crisis in European countries. While Germany’s economic situation and the national debt appear to be recovering swiftly, other countries – such as Romania and Greece have taken up international loans linked to strict budget plans and extensive struc- tural reforms. In these states in particular the austerity Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  A. HEISE ET AL. 510 programmes are very harsh. However, there are also dif- ferences: Iceland also stood on the brink of state bank- ruptcy when the nationalisation of the three largest banks greatly exceeded the national finances. Although the Icelandic government applied for billions in international loans annual consolidation is quite low, at 2.4 per cent. The approach of Prime Minister Sigurðardóttir’s gov- ernment which envisages cuts worth 12 per cent of GDP is a long-term one, over a five year period, and thus low expressed as an annual average. Table 1 presents, besides the size of the consolidation package, the relationship between revenue increases and spending cuts as a percentage of the respective austerity package. According to our calculations all states focus predominantly on cuts in spending rather than on in- creasing or introducing taxes or social contributions. This can be explained by the fact that the economic lit- erature shows that consolidation is more effective and more sustained by means of spending cuts than consoli- dation through tax increases, as highlighted by the Euro- pean Commission [49]. However, given the extent of government debts one-sided consolidation is consi- dered insufficient. Although all states are relying largely on cuts consid- erable differences with regard to consolidation appro- aches can be observed. While almost half the Greek aus- terity programme is being achieved through tax revenues their proportion in the Romanian package is only one- sixth. These differences can be traced back, on the one hand, to variations in national circumstances and so to the existing scope for cuts and tax increases. On the other hand, there are also governments that subscribe to dif- ferent values and have different national traditions, which certainly favour different consolidation appro- aches. The crisis and the dire state of the public finances have served in all countries both to trigger and to justify cuts in the welfare state. In Germany, for example, about one- third of all consolidation measures involve social secu- rity reforms, while in Britain they make up one-fifth. In Spain, in contrast, the cuts represent only around five per cent and in Iceland about 15 per cent. In other words, while some countries have focused on welfare cuts, in others they have been far less significant. In addition, findings show that an automatic uncoordinated European convergence is improbable: even countries such as Brit- ain and Romania plan further reductions although social spending as a proportion of GDP is already below the EU average (see Section 1). The data show, therefore, that also in future there is no question of an automatic adjustment to a social security standard, but rather that European coordination is necessary. Not only the proportion of welfare cuts but also the ways in which they are made differ considerably. In ge- neral, either the pension or the health care system is af- fected in all countries, in many cases both. In these areas certain tendencies can be observed: in pensions, besides increases in the retirement age, calculation bases are be- ing extended and individual contribution equivalence is being strengthened. While most governments plan struc- tural reforms in pension schemes Romania originally decided to implement across-the-board cuts of 15 per cent and 10 per cent, respectively. Since these were struck down by the Constitutional Court similar effects are to be achieved by structural reforms. It is all the more astonishing that the Icelandic government passed a pen- sion reform which bucks this trend. Pensions in Iceland are to be cut back with increasing incomes and individual equivalence reduced. Besides health care systems other social spending has been affected in all countries. In health care, cuts have been made through price and cost caps, increasing resort to generic drugs, less inpatient treatment and individual co-payments. While the scope of these measures differs by country a move away from state benefits and towards individual co-payments and risk provision can be ob- served. Besides cuts in health care, benefits and services in other areas of social security have been scaled back. In Romania all benefits have been cut by 15 per cent; in Germany parental benefits for social security recipients have been abolished; in Britain housing benefit has been cut; in Spain baby cheques have been abolished. While most countries are making savings at the ex- pense of those on low incomes, only a few governments are pursuing a strategy which also involves higher ear- ners in debt consolidation. For example, Britain and Germany are making cuts which affect the neediest and social benefit recipients with the aim of reducing the wage gap and boosting employment incentives. This represents a regressive policy, with in effect redistri- bution from low to high earners. However, also those programmes which plan mainly across-the-board welfare cuts such as those of Spain and Romania can be catego- rised as regressive. In contrast, Iceland has passed wel- fare cuts which predominantly affect middle and higher incomes. In addition, only a few countries such as Ice- land and Greece plan to involve higher earners through taxation of property or wealth or through taxes on pro- fitable companies. Although some other countries, such as Britain, have introduced a banking levy they have at the same time reduced corporate taxes, thereby diluting the redistributive component. Basically, the international economic crisis and the re- sulting public debt situation have served in all six coun- tries as both trigger and justification of social spending cuts. Although their consolidation strategies share a Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  A. HEISE ET AL.511 number of similarities there are also considerable diffe- rences: on the one hand, there appear to be few countries whose approach includes a redistributive component and thus represents a progressive approach; on the other hand, most consolidation programmes – such as those of Brit- ain and Germany are in effect targeting those on lower incomes. 4. Conclusions Europe said goodbye long ago to defining social policy within the framework of a particular concept of society. Welfare states have given way to historically differing European social models in which social policy must fol- low economic and fiscal priorities. This implies both a declining solidarity component in social security and a financial commitment which declines for every succes- sive benefit claim in pursuit of alleged incentive and al- location effects. This general assessment applies not only to the developed EU states of “Old Europe”, but also to the convergence candidates in the south and east of the EU, which have deserted the former development path with its higher correlation between economic develop- ment and social provisions. The hope that the world financial crisis, with its social upheavals, could lead to a rethink and that the hotly con- tested—European Social Model could serve as the basis for an alternative approach to European integration seems vain, given the budgetary situations in almost every EU country. Almost everywhere, even in the wake of the global financial crisis, the orthodox truths of fi- nance policy balanced budget within the framework of the Stability and Growth Pact still apply or are formu- lated even more starkly. The belief that budget consoli- dation is more likely to succeed on the basis of spending cuts than revenue increases also seems unshakable6. In all the cases investigated – perhaps with the excep- tion of Iceland regressive spending cuts predominate, regardless of the composition of the government. Reve- nue increases by means of progressive tax rate rises at best play a subordinate role: occasionally, regressive VAT increases are partly offset by corporate tax in- creases, thereby heightening the regression. Even coun- tries such as Ireland, which have to apply to the Euro- pean aid programme, appear to have been able to avoid having to raise their competition-distorting low corporate taxes. Since almost everywhere in the EU regressive auster- ity measures of unprecedented magnitude have been im- plemented the consolidation effects are at the very least unclear: the still dominant fiscal orthodoxy is built on the notion of the crowding in of private investment as gov- ernment spending falls. Then the growth path can remain intact or even with corresponding expectation effects in- crease and consolidation succeed alongside a trimmed social state [51]. The alternative (Keynesian) view regards as naïve the hope of a compensating private crowding in the event of falling consumer spending power and fears negative effects with regard to growth which depending on the magnitude of the multiplier and accelerator effects will at the very least hinder consolidation, if not make it impossible [51]. The more widespread the cuts the less hope there is that deficient domestic demand can be com- pensated by external (export) demand. There is therefore a great deal of evidence of a stagnant growth scenario in the EU in which consolidation efforts will have little success and thus the pressure towards regressive mea- sures will even increase [1]. Considering, finally, that the EU and the European Monetary Union are characterised by increasing regional imbalances which cannot be sustained over the long term (see, for example, [52]) the danger cannot be ignored that the pessimistic convergence prognosis will become real- ity: if regulation at EU level does not prevent it cuts in social services as both a consolidation and a competi- tiveness strategy could become dominant. Given the di- verse social models in the EU member states a harmoni- sation of social policy as a counter-strategy is not only somewhat unconvincing but also impractical. A concept which maintained national autonomy over social policy, while preventing both absolute and relative forms of dumping, however, could be accepted: this is the so- called corridor model (see [10 and 53]). On this basis the connection between economic development and social security (see Figure 2(a)) which prevailed in the 1990s could be institutionally safeguarded by requiring each member state to guarantee a social spending rate in ac- cordance with its state of development within a defined corridor. Economic advancement of the kind achieved by, for example, Ireland would be linked to a corresponding expansion of the welfare state the priorities would re- main a national matter, but relative dumping would be halted. And absolute dumping in crisis periods would be prevented unless the Community, on the basis of shared responsibility, redefined the corridor. 6Which is peculiar as empirical evidence produced by a recent study o the IMF clearly shows no clear correlation between the type of con- solidation and the success of large fiscal adjustments: large fiscal ad- ustments can be almost entirely based on income increasing measures as in Greece between 1995 and 2001 or can be based almost entirely on expenditure reductions as in Belgium between 1998 and 2009. Or they can be based on a mixture of revenue increase and expenditure cuts as in Ireland (1989 – 2001), Sweden (1987 – 1994) or Denmark (1986 1991); [50]. After the billions spent on rescue packages for banks and whole countries such a European Social Model could be considered a necessary social shield which would restrict national autonomy no more than the single cur- rency and the European Stability and Growth Pact have Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  A. HEISE ET AL. 512 long done. The social protests all over Europe serve as a reminder that an EU without social foundations could, in the long term, be built on sand. 5. References [1] P. Arestis and T. Pelagidis, “Absurd Austerity Policies in Europe,” Challenge, No. 6, 2010, pp. 54-61. [2] J. Alber, “The European Social Model and the United States,” European Union Politics, Vol. 7, No. 3, 2006, pp. 393-419. doi:org/10.1177/1465116506066272 [3] Ch. Strünck, “Wahlverwandtschaften Oder Zufallsbekann- tschaften? Wie Wohlfahrtsstaat und Wirtschaftsmodell zusammenhängen,” R. Heinze, A. Evers, So-zialpolitik, VS Verlag, Wiesbaden, 2008, pp. 139-156. [4] G. Esping-Andersen, “The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism,” John Wiley and Sons, Cambridge, 1990. [5] K. Busch, “Die Perspektiven des Europäischen Sozial- modells,” Arbeitspapier Nr. 92, Hans-Böckler-Stiftung, Düsseldorf 2005. [6] F. W. Scharpf, “The European Social Model,” Journal of Common Market Studies, Vol. 40, No. 4, 2002, pp. 645- 670. doi:org/10.1111/1468-5965.00392 [7] W. Streeck, “Competitive Solidarity: Rethinking the‚ European Social Model,” KKontingenz und Krise, Cam- pus Publisher, Frankfurt, 2000, pp. 245-262. [8] M. Threfall, “European Social Integration: Harmoniza- tion, Convergence and Single Social Areas,” Journal of European Social Policy, Vol. 13, No.2, 2003, pp. 121-139. doi:org/10.1177/0958928703013002002 [9] A. Sapir, et al., “An Agenda for a Growing Europe. Making the EU System Deliver,” Report of an Independ- ent High Level Group Established on the Initiative of the President of the Commission, Brussels, 2003. [10] K. Busch, “Das Korridor-Modell ein Konzept zur Weite- rentwicklung der EU-Sozialpolitik,” Wohlfahrtsstaat. Krise und Reform im Vergleich, Metropolis Publisher, Marburg, 1998, pp. 273-295. [11] W. Streeck, “Gewerkschaften zwischen Nationalstaat und Europäischer Union,” Working Paper 96/1. Köln: Max- Planck-Institut für Gesellschaftsforschung, 1996. [12] Ch. Joerges and F. Rödl, “Social Market Economy as Europe’s Social Model?” A European Social Citizenship? Preconditions for Future Policies from a Historical Per- spective, Lang Publisher, Brüssel, 2004, pp. 125-157. [13] S. Leibfried and P. Pierson, “Semi-Sovereign Welfare States: Social Policy in a Multi-Tiered Europe,” Euro- pean Social Policy: Between Fragmentation and Integra- tion, Brookings Institutions Press, Washington, 1995, pp. 43-77 [14] A. Aust, “Umbau oder Abbruch des Europäischen Sozial- modells? Bemerkungen zu einer aktuellen europäischen Strategiedebatte,” Erweiterung und Integration der EU. Eine Rechnung mit vielen Unbekannten, VS Verlag, Wiesbaden 2004, pp. 147-174. [15] I. Hofbauer, “Das Europäische Sozialmodell als trans- nationales Modernisierungsund Legitimationskonzept,” Kurswechsel, No. 1, 2007, pp. 38-47. [16] L. Hooghe and G. Marks, “The Making of a Polity. The Struggle over European Integration,” Continuity and Change in Contemporary Capitalism, CUP, Cambridge 1999, pp. 70-100. [17] European Commission, “Growth, Competitiveness, and employment: The Challenges and Ways Forward into the 21st Century,” Com (93) 700 Final, Brussels, 1993. [18] G. Schmid, “Europas Arbeitsmärkte im Wandel. Institutionelle Integration oder Vielfalt?” Die Reformfä- higkeit von Industriegesellschaften: Fritz W. Scharpf Festschrift zu seinem 60. Geburtstag, Campus Publisher, Frankfurt/New York, 1995, pp. 250-276. [19] B. Priddat, “Linke Angebotspolitik?” Neue Balance zwis- chen Markt und Staat? Sozialdemokratische Reformstra- tegien in Deutschland, Frankreich und Großbritannien, Wochenschau Publisher, Schwalbach/Ts., 2001, pp. 99-116. [20] U. Brand, “Strategien progressiver Kräfte in Europa. Re- bellische Subjektivität und radikale Forderungen,” Widerspruch Beiträge zu sozialistischer Politik, No. 50, 2006, pp. 167-174. [21] A. Heise, “Toxische Wissenschaft? Zur Verantwortung der Ökonomen für die gegenwärtige Krise,” Wirtscha- ftsdienst, Vol. 89, No. 12, 2009, pp. 842-848. [22] A. Heise, “Finanz-und Steuerpolitik nach der Krise sind die Weichen Richtig Gestellt?” Perspektiven ds. Zei- tschrift für Gesellschaftsanalyse und Reformpolitik, Vol. 27, No. 1, 2010, pp. 53-63. [23] A. Heise, “Optimal Public Debts, Sustainable Deficits, and Budgetary Consolidation,” Empirica, Vol. 29, No. 4, 2002, pp. 319-337. [24] Federal Ministry of Finance, “Nachhaltig Sparen-Gerecht Sparen: Das Zukunftspaket der Bundesregierung BRD Presse, Wirtschaft und Verwaltung,” 9. 6. 2010. http://www.bundesfinanzministerium.de/DE/Wirtschaft_ _und__Verwaltung/Finanz__und__Wirtschaftspolitik/Bu ndeshaushalt/20100609-Sparen.html. [25] S. Hegelich, H. Meyer, Konflikt and Verhandlung, “Sozialer Friede: Das deutsche Wohlfahrtssystem, in: K. Schubert,” Europäische Wohl-fahrtssysteme: Ein Handbuch, VS Verlag, Wiesbaden, 2008, pp. 127-148. [26] Federal Ministry of Finance, “Germany Stability Pro- gramme 2010: January 2010 Update (Fiscal and Eco- nomic Policy)” 2010. http://www.bundesfinanzministerium.de/nn_1270/nsc_tru e/DE/Wirtschaft__und__Verwaltung/Finanz__und__Wirt schaftspolitik/Finanzpolitik/Deutsches__Stabilitaetsprogr amm/Kabinettvorlage__Germany__Stability__Programm e__Jan__2010__Update,templateId=raw,property=public ationFile.pdf . [27] Bundesregierung Online, “Für ein Gerechtes, Soziales, Stabiles, Wettbewerbliches und Transparentes Gesund- Heitssystem, Eckpunktepapier zum Gesundheitssystem vom” 6.7.2010. http://www.bundesregierung.de/Content/DE/__Anlagen/2 010/2010-07-06-eckpunkte-gesundheit,property=publicati Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  A. HEISE ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 513 onFile.pdf [28] F. Blank and S. Leiber, “Nachhaltige Finanzierung des Ge Sundheitssystems ohne Kopfpauschalen,” WSI-Mittei- lungen, Vol. 63, No. 10, 2010, pp. 542-543. [29] Stability Programme ES, “Stability Programme Update Spain,” 2009-2013. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/sgp/pdf/20_scps/20 09-10/01_programme/es_2010-02-01_sp_en.pdf [30] Ley Decreto Medidas Adicionales, “Ley decreto Medidas Adicionales,” Bultin Oficial del Estado, No. 126, 24 May 2010. [31] Labour Market Act Spain, “Líneas de Actuación En El Mercado De Trabajo Para Su Discusión Con Los Interlo- Cutores Sociales En El Marco Del Diálogo Social,” Presi- dencia del Gobierno de España 2010. http://www.la-moncloa.es/ActualidadHome/2009-2/0502 10EnlaceDocumento [32] Eurostat, “Website: Europäische Statistik der Europäi- schen Kommission: Länderprofile, Luxemburg,” 2010. http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/eurosta t/home/ [33] S. Lessenich, “Spanien: Arbeitsmarkt und Sozialpolitik im postautoritären Wohlfahrtsstaat,” Arbeitslosigkeit und Wohlfahrtsstaat in Westeuropa, Leske and Budrich Publisher, Wiesbaden, 1997, pp. 281-310. [34] El Mundo, “El Gobierno Da Marcha Atrás En Su Propuesta De Elevar a 25 Años La Base Para Calcular Las Pensiones,” El Mundo, 3.2.2010 [35] K. Hinrichs, “Rentenreformen in Europa: Konvergenz der Systeme?” Wandel der Wohl Fahrtsstaaten in Europa, Nomos Publisher, Baden-Baden, 2008, pp. 155-177. [36] P. de Villota Gil-Escoin and S. Vázquez, “Work in Progress: Das spanische Wohlfahrtssystem,” Europäische Wohlfa hrtssysteme: Ein Handbuch, VS Publisher, Wiesbaden, 2008, pp. 169-185. [37] Stability Programme GR, “Update of the Hellenic Stabil- ity and Growth Programme: Including an Updated Re- form Programme.”2011. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/sgp/pdf/20_scps/20 09-10/01_programme/el_2010-01-15_sp_en.pdf. [38] Stability Programme GR, “March 2010 Report to the Implementation of the Hellenic Stabilitiy and Growth Programme and Additional Measures.”2011. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/sgp/pdf/30_edps/ot her_documents/2010-03-08_el_progress_report_en.pdf [39] K. Davaki and F. Mossialos, “Financing and Delivering Health Care,” Social Policy Developments in Greece, Ashgate Publisher, Aldersot, 2006, pp. 55-72. [40] Iceland, “Report by the Minister of Finance to the 137th session of the Althingi. Measures to Achieve a Balance in fiscal Finances 2009-2013 Stability, Welfare and Work,” 2011. http://eng.fjarmalaraduneyti.is. [41] Iceland, “The Fiscal Budget Proposal for 2011,” October 1, 2011. http://eng.fjarmalaraduneyti.is/media/Fjarlog/Budget_Pro posal_2011_presentation.pdf [42] IMF, “IMF Country Report: Iceland. Selected Issues Paper No. 10/304, International Monetary Fund,” October 2011. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2010/cr10304.pdf [43] G. Jonsson, “The Icelandic Welfare State in the Twenti- eth Century,” Scandinavian Journal of History, Vol. 26, No. 3, 2001, pp. 177-196. doi:org/10.1080/034687501750303873 [44] Stability Programme RO, “Convergence Programme 2009-2012 (Government of Romenia, March 2010),” 2011. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/sgp/pdf/20_scps/20 09-10/01_programme/ro_2010-03-23_cp_en.pdf [45] HM Treasury, “Budget; HM Treasury; London: June 2010,” 2011. http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/2010_june_budget.htm [46] Financial Plan UK, “Spending Review 2010, HM Treas- ury (October 2010),” 2011. http://cdn.hm-treasury.gov.uk/sr2010_completereport.pdf [47] IFS, “The Distributional Effects of Tax and Benefit Re- forms to be Introduced between June 2010 and April 2014: a Revised Assessment,” IFS Brief Notes, London, 2010. [48] L. Mitton, “Vermarktlichung Zwischen Thatcher und New Labour: Das Britische Wohlfahrtssystem,” Europäi- sche Wohlfahrtssysteme: Ein Handbuch, VS Publisher, Wiesbaden, 2008, pp. 263-284. [49] EU Commission, “Public Finances in EMU,” European Economy, Brussel, No. 4, 2010. [50] IMF, “Strategies for Fiscal Consolidation in the Post- Crisis World. Prepared for the Fiscal Affairs Department, February 2, 2010,” 2011. http://www.imf.org/external/np/eng/2010/020410a.pdf. [51] A. Heise, “Einführung in die Wirtschaftspolitik,” Lit Publisher, Münster, 2010. [52] S. Dullien, “Ungleichgewichte im Euro-Raum. WISO Diskurs Expertisen und Dokumentationen zur Wirtschafts und Sozialpolitik,” Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Bonn, 2010. [53] A. Heise, “Grundlagen der Europäischen Währung—Sin Tegration,” Gabler Publisher, Wiesbaden, 1997.

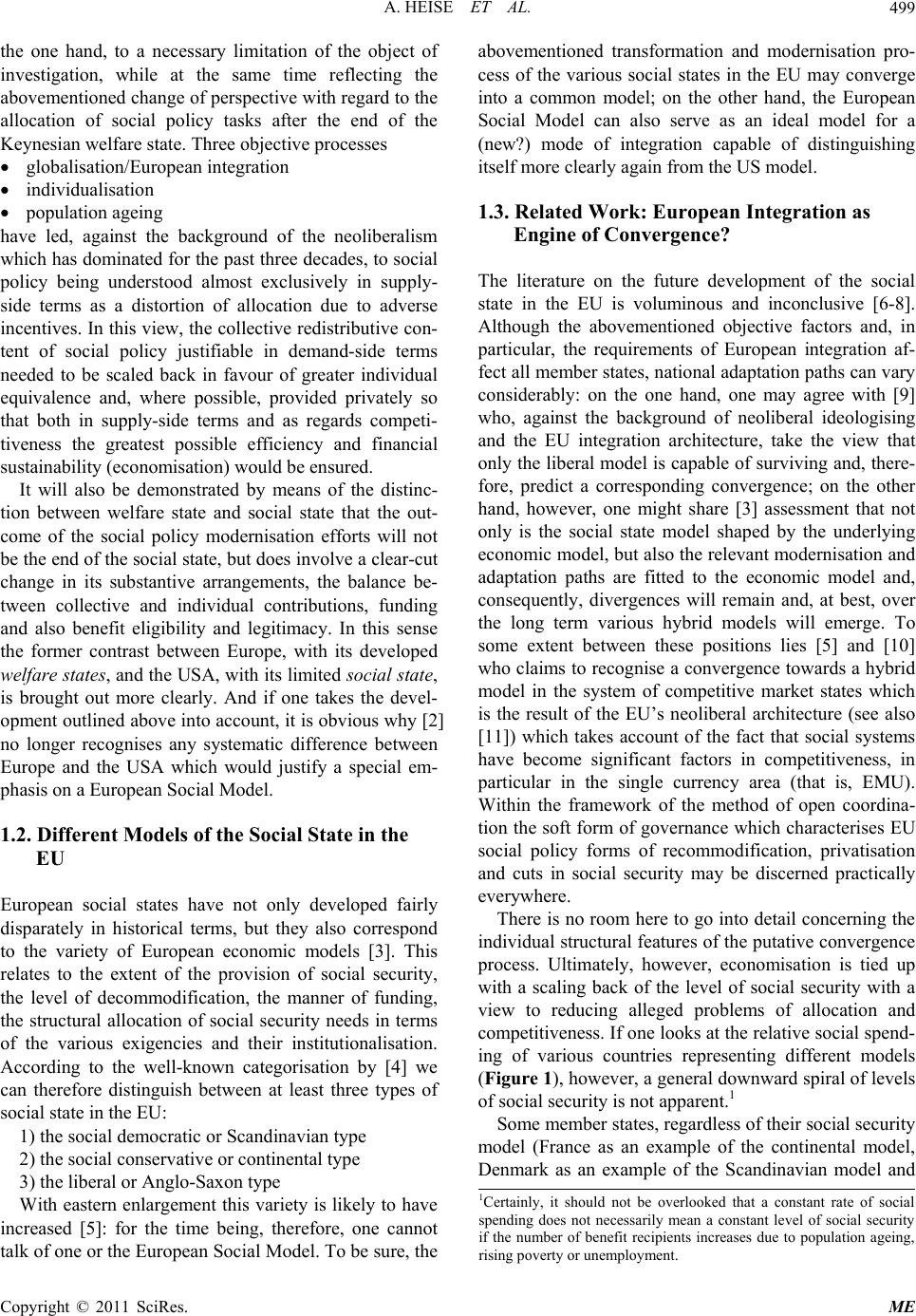

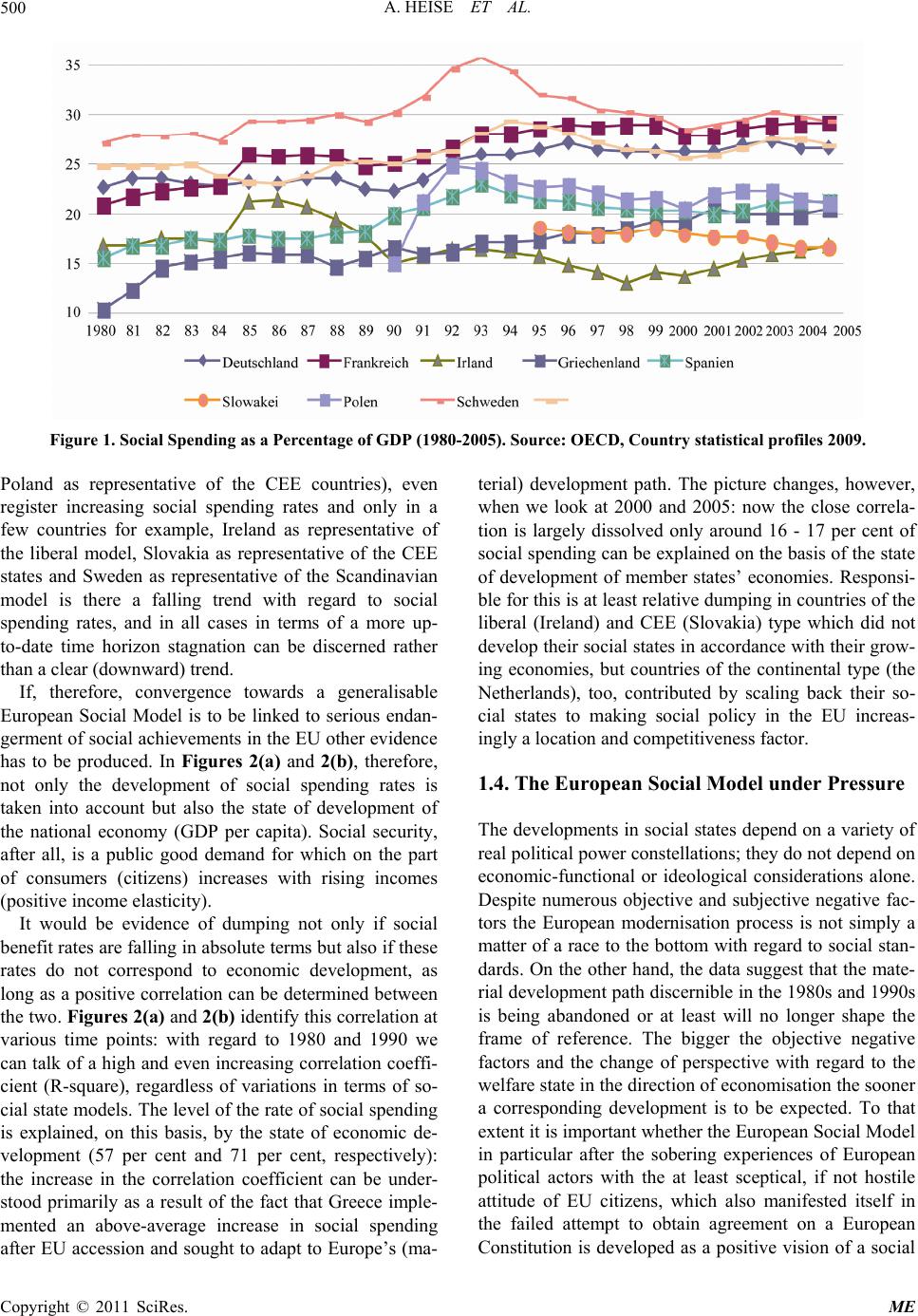

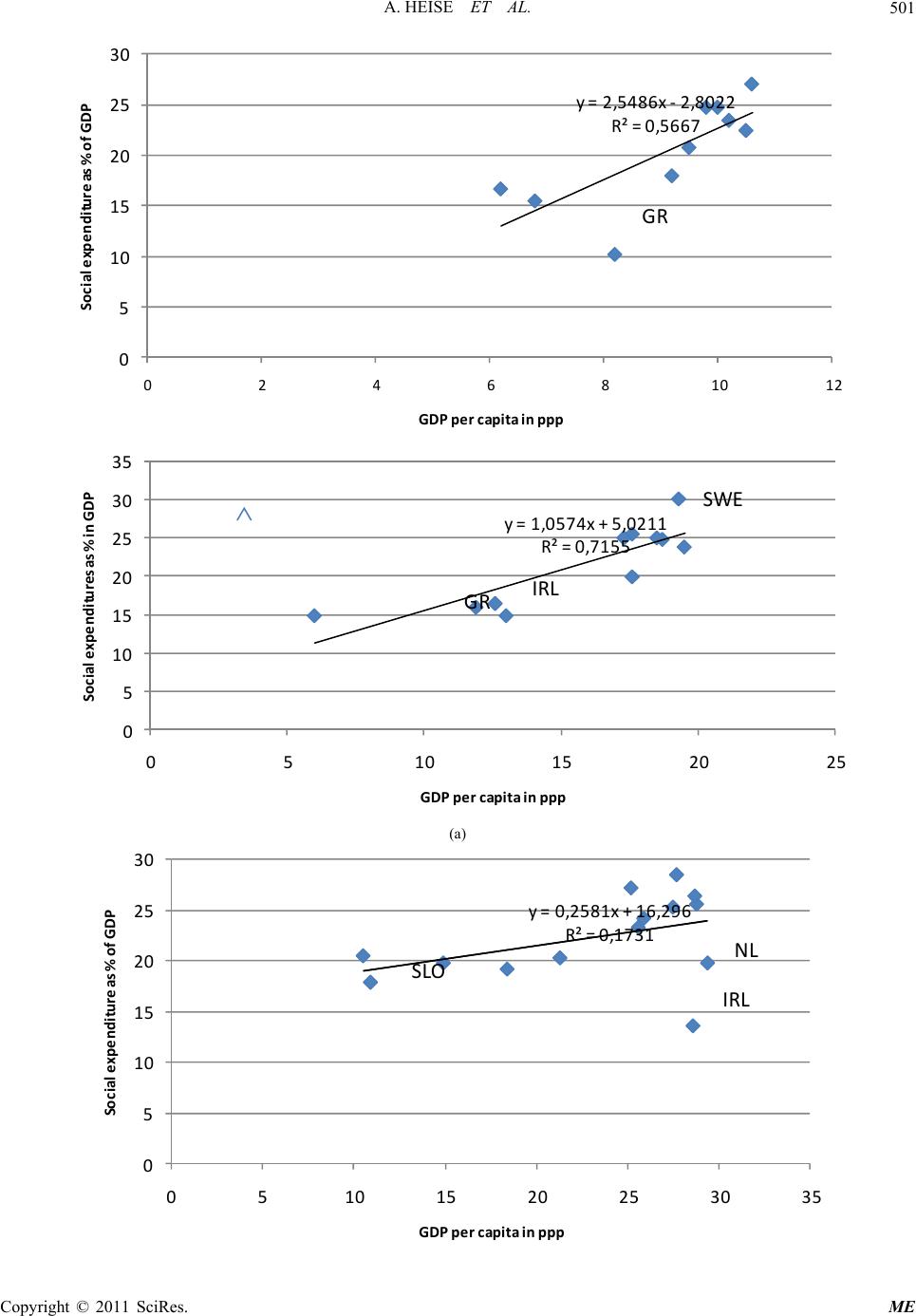

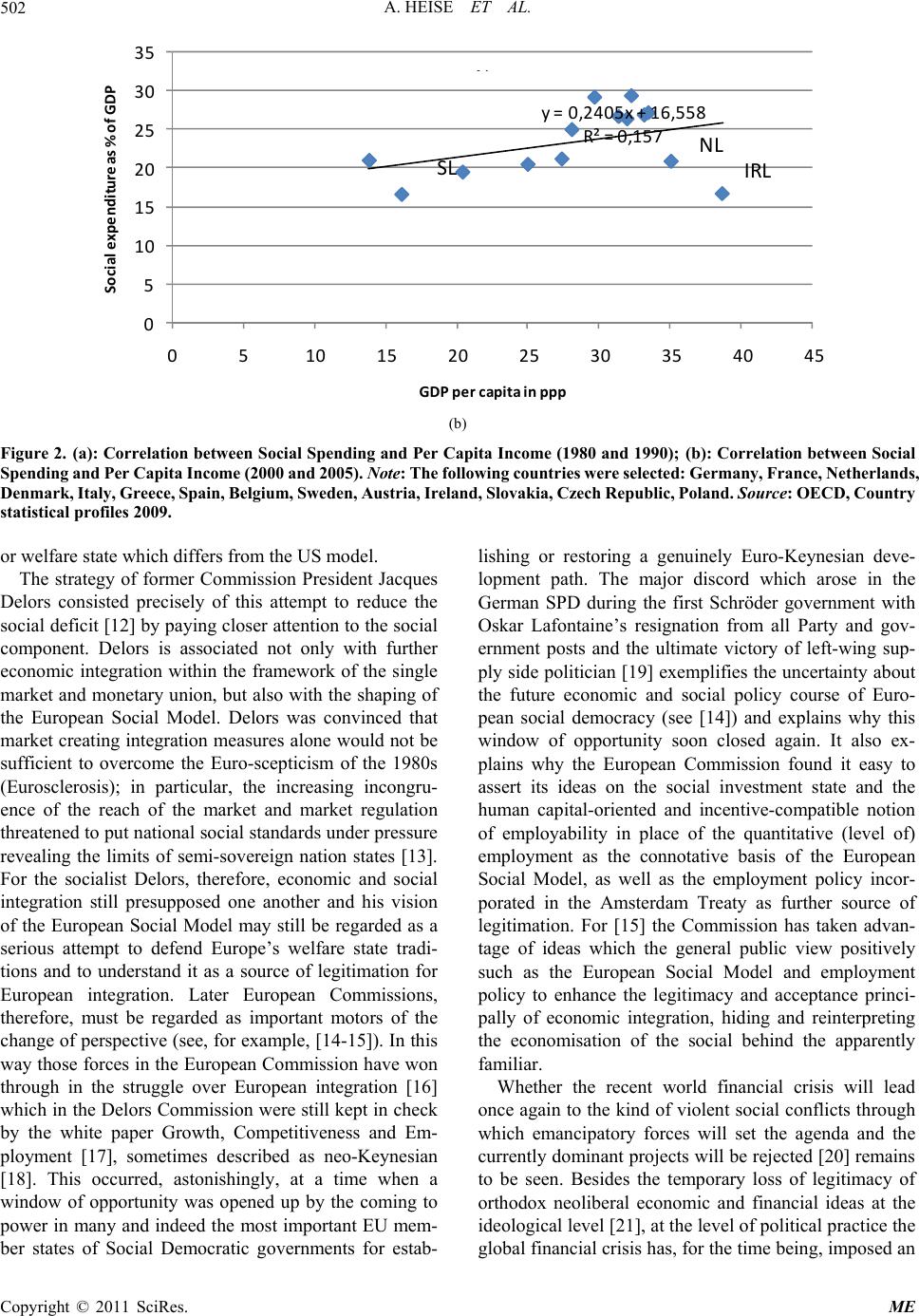

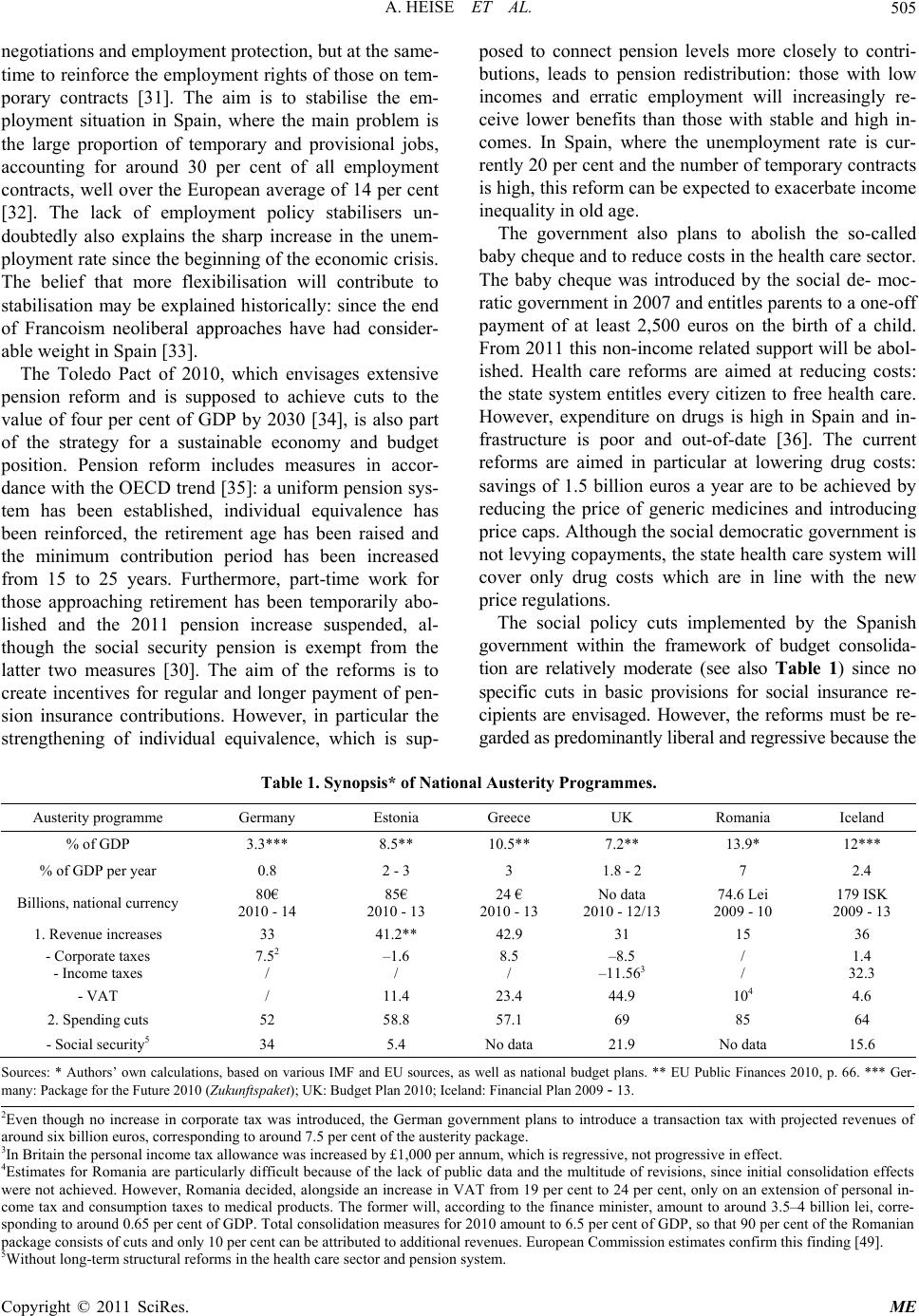

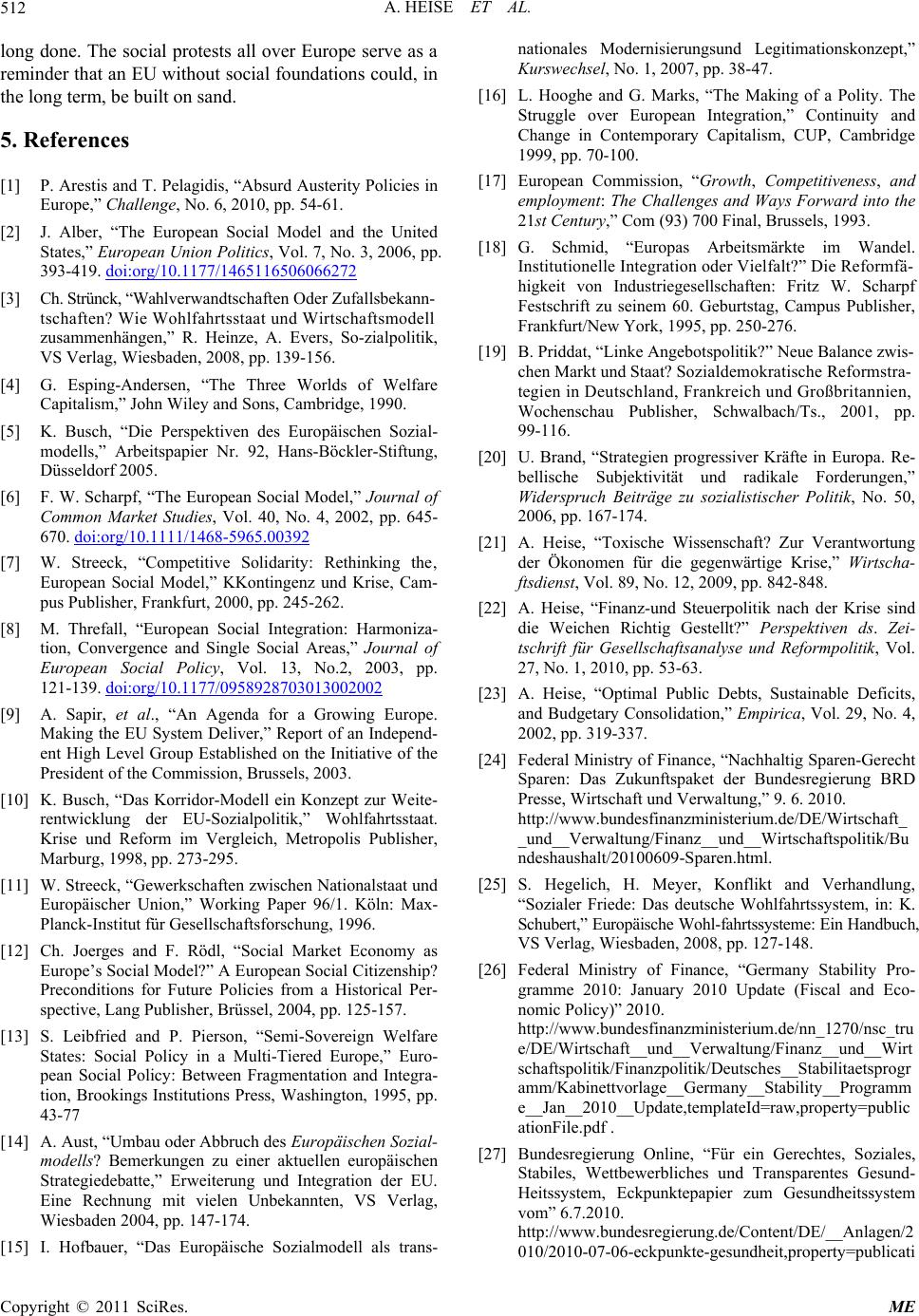

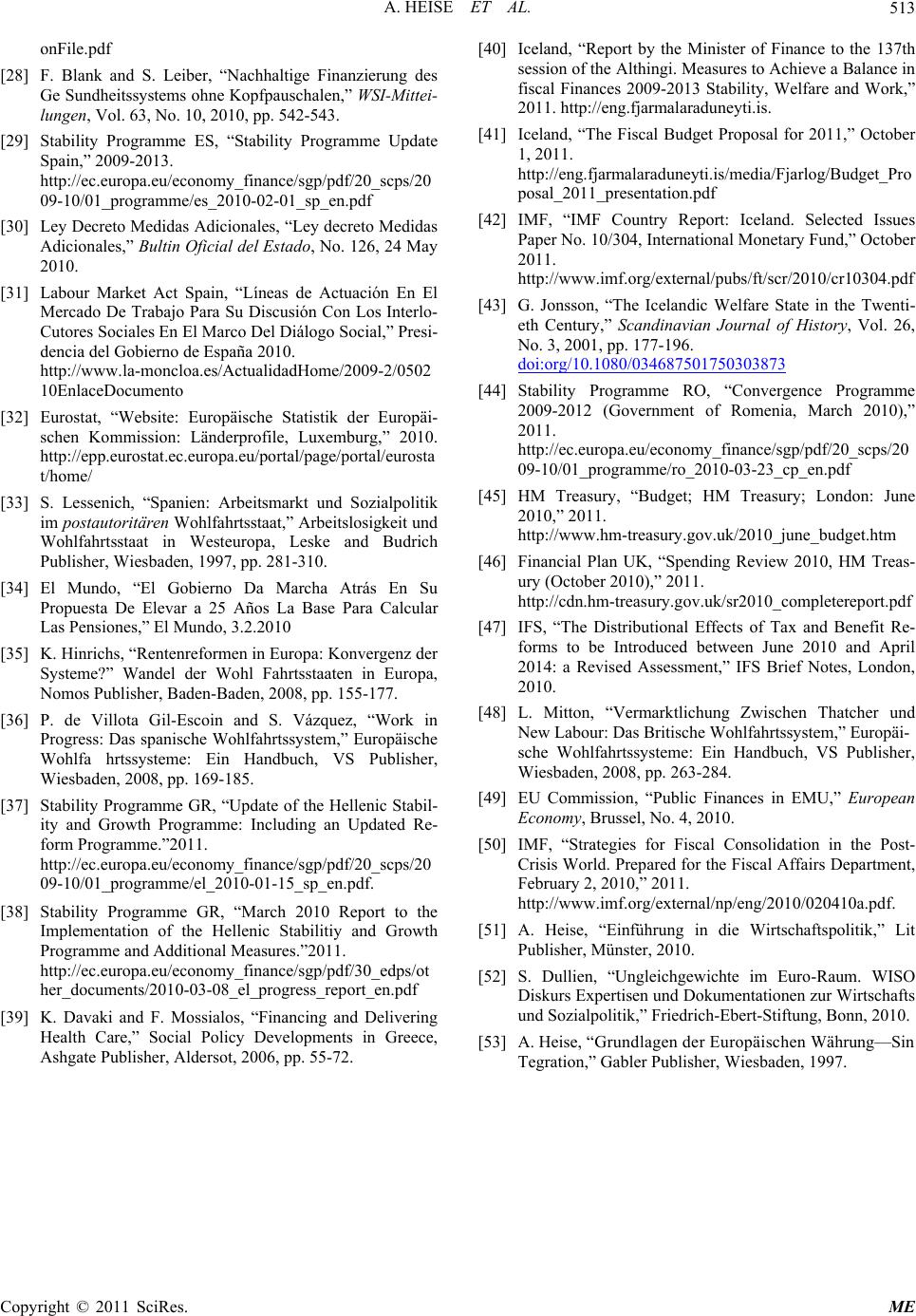

|