Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

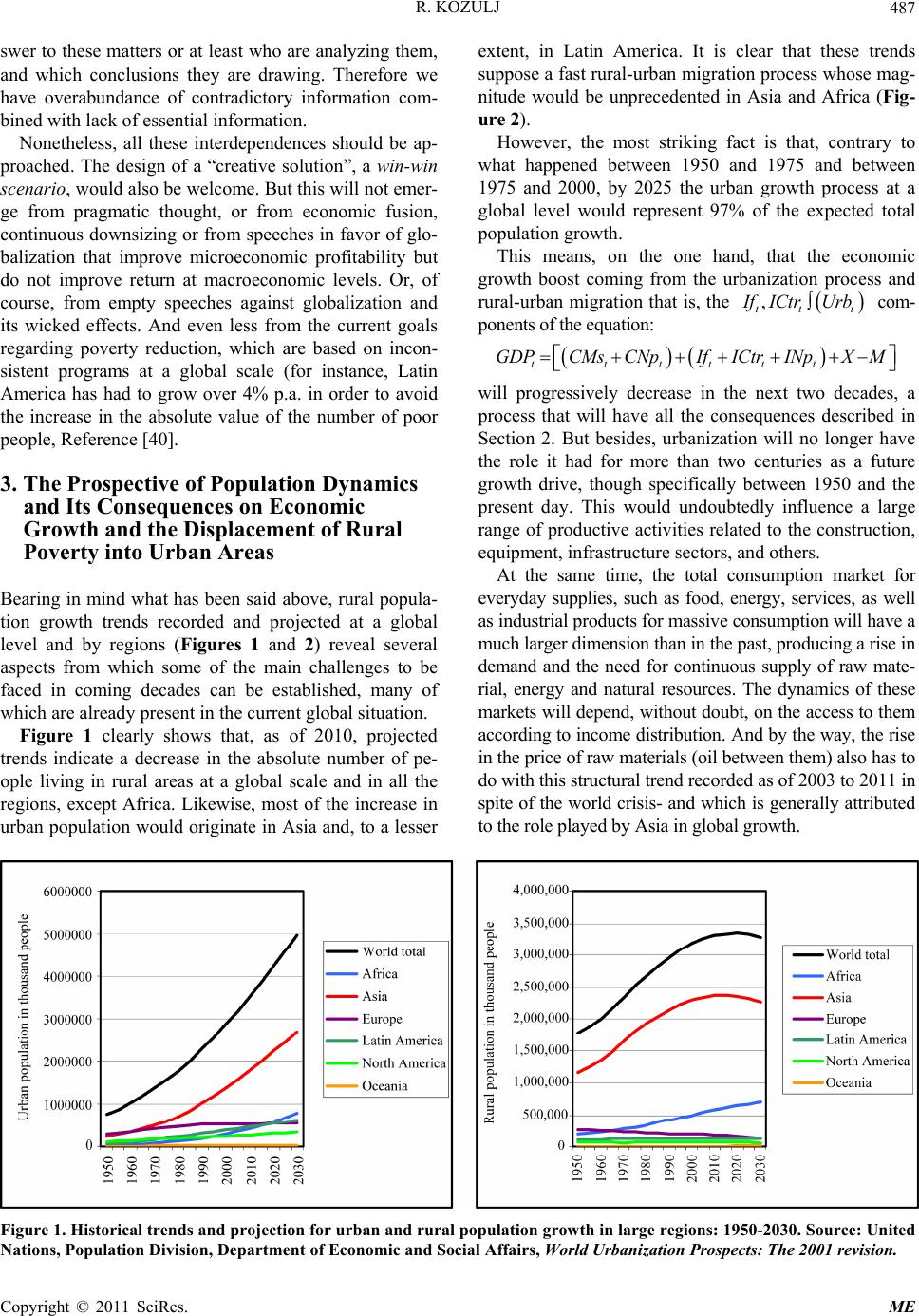

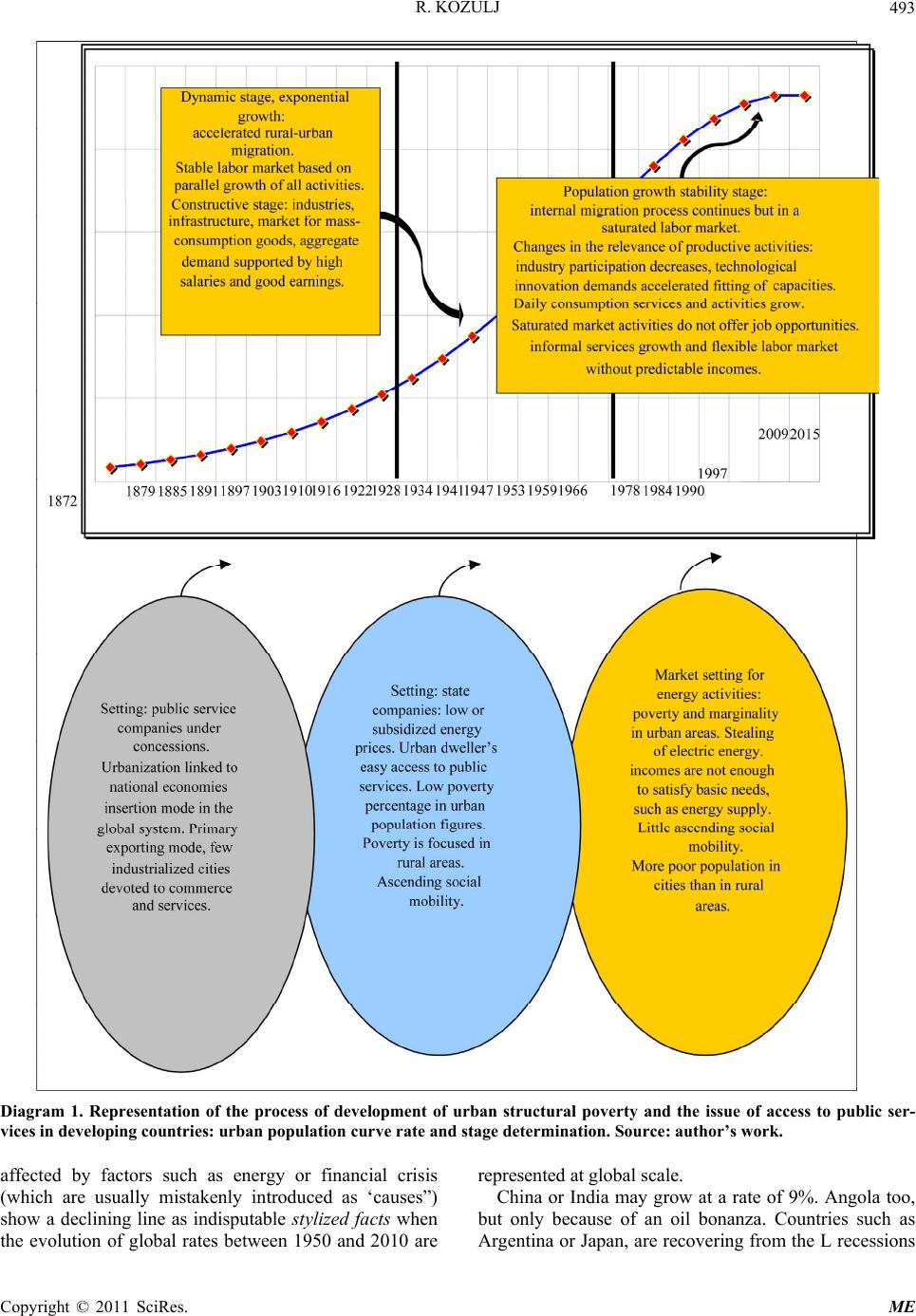

Modern Economy, 2011, 2, 483-497 doi:10.4236/me.2011.24054 Published Online September 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/me) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME Development, Poverty and Energy, in the 21st Century Roberto Kozulj Bariloche Foundation, Río Negro, Argentina E-mail: rkozulj@fundacionbariloche.org.ar Received January 31, 2011; revised April 2, 2011; accepted April 29, 201 1 Abstract This work explores the area of global interdependences and the global context. In particular it deals with in- terdependences that seem to be absent from current literature but could be of great significance to identify the biggest challenges that the economy and the energy sector will have to face in the next two or three de- cades. In that sense, several issues are addressed: the dynamics of economic growth and its future; the rela- tion between these dynamics and the foreseeable importance that urban poverty is to have at a global scale; the lack and inadequacy of information to approach crucial interdependences; and the need for a change in institutions and thinking habits to analyze the future. The approach focuses on the complex relationships that link urbanization, development phases, and technological changes dependent on products with shorter life cycles, discussing the impact of this kind of process over the genesis of urban poverty and over the structural modifications of economy. At the same time, a view on how these interdependences will become a serious and increasingly complex challenge for the energy sector and long term global sustainability is presented. The author also emphasizes the fact that these interdependences will become a serious and increasingly com- plex challenge that the energy sector will have to face if long term sustainability is to be attained. Keywords: Economic Growth, Poverty, Dual Society, Energy, Long-Term Economics Crises, Urban Poverty Dynamics 1. Introduction The main purpose of this research is to characterize the dynamics of economic growth from a long-term evolu- tionary approach linking urbanization processes and technological change. It aims to explore the problem of the growing interdependences affecting real processes of economic growth, their dynamics—which change over time and space, their links with other aspects such as the genesis of poverty and marginality in urban areas and the challenges derived from such dynamics into the future, also in relation to energy. The text has been dived into sections in order to provide a sequenced explanation of the complex nature of these links and because of the need for a comprehensive approach to explain as well as to understand th e problem. The main hypotheses, then, are formulated in Section 2. They are an attempt at describing, from a heterodox and evolutionary perspective, the genesis of the dual so- ciety or, in other word s, the genesis of poverty coex istin g with opulence in urban areas. What makes this approach original is the evolutionary perspective from which ur- banization and technological change processes are ana- lyzed as specific and structural factors explaining both the dynamics and changing nature of the economic acti- vity, as well as its impacts on economic growth and the factors that limit income distribution. These factors are accounted for as a consequence of supply price forma- tion and of large-scale rural-urban migration processes, which also include intergenerational factors when con- sidered in the long term. Alongside the hypotheses mentioned above, Section 3 explores foreseen trends for urban population growth at the regional and global levels. Two main aspects are considered: a) urban population growth in Asia and Af- rica will predominate in the urbanization process for the next two decades; b) that will imply that, out of the total increase foreseen for world population, 97% will corre- spond to urban population, which would indicate the proximity of a limit to the global urbanization process and a decrease in absolute terms in the number of total rural population. Such projections have several consequences, but the most important ones are related to the fact that urbanize- tion will no longer have a role as the drive for future growth, as was the case over more than two centuries,  R. KOZULJ 484 particularly between 1950 and the present day. This would deepen the gap within global product formation of activities characterized by shorter life cycles, indentified as the ones that limit the p ossib ility of impr oving inco me distribution and job creation. In turn, job opportunities for those migrating from rural to urban areas will con- tinue to decrease. Section 4 explores succinctly some of the foreseen consequences over the energy sector of the scenarios suggested above. Since the consequences related to ques- tions such as supply security, energy efficiency and car- bon emissions are, in general, discussed at length in pub- lic debate and in the academic field, they have not been dealt with here. On the contrary, the impacts of such scenario on the complex links between energy and po- verty have been approached from an inappropriate per- spective which does not permit the co mprehension of the nature of future challenges. This is why Section 5 specifically deals with the en- ergy-poverty question, remarking the fact that the dis- placement of poverty from rural to urban areas imposes a new scenario whose foreseen impact is not even present in the agenda on the topic. Emphasis is also laid on the fact that economic and social indicators are not suitable for a proper analysis of this scenario or for exploring solutions. The differences between poverty in urban and rural areas are specifically discussed here, as well as their consequences on the energy sector from the point of view of both the cost to be paid by consumers, the en- ergy access question, and the cross impact of the supply security issue, biofuel production and the cost of food and energy. Finally, and by way of conclusion, the need to readjust both institutions and thought habits is suggested. The new scenario emerging from the set of explanations pre- sented here requires that in order to set a new world agenda where topics such as context, interdependences and complexity can be approached, and public policies can thus be adapted to the emerging global situation. 2. The Current Growth Dynamics: Urbanization, Technological Change and the Genesis of t he Dual Society The urbanization process involves the use of capacities of very specific activities which are linked to technolo- gies. Therefore, a large corpus of research has suggested that this process should not be considered solely an effect of growth, but also one of its main driving forces, Ref- erences [1-17]. And, in terms of factor mobility and in- fluence in economic growth, these technologies imply a less flexible world than the one commonly assumed by the economic theory, References [18,19]. So the question is: What happens to economic growth when the urbani- zation process becomes saturated? The answer found is that some productive activities that are related mainly to capital goods, though not exclusively to them, also de- celerate. Markets become increasingly saturated and new products, either goods or services, must be created. The role played by innovation is crucial here, References [20-24]. This means that each phase in the transition process will lead to an adaptive change in productive structures, technologies, institutions and market opera- tion customs. This adaptive change has two main fea- tures: 1) The typical displacement from agricultural ac- tivities to industrial activities and from industrial activi- ties to services of previous development stages has to face the absence of a fourth sector capable of absorbing employment. This situation worsens when automatiza- tion in the other three sectors increases, Reference [25]; 2) accelerated technological change or “innovation”, that is the production of an equivalent or greater product quantum that replaces the decrease of saturated markets implies products with shorter life cycles almost inevi- tably when innovation refers to the same products and not to processes. But when it comes to supply price for- mation, shorter life cycles require that a greater propor- tion goes to recovering the capital, even wh en profit rates stay the same, References [9-10]. This leads to a struc- tural limitation of income distribution1, which literally means lower salaries and lower taxes, a factor that, in turn, appears in a context of reduced global dynamics as a determining element for job levels. Service sector ac- tivities to be created in urban areas in order to absorb labor are generally not enough and also limited by in- come distribution, References [25-26]. This is the world of flexible accumulatio n that has substituted old Fordism, References [27-29]. However, there are at least two factors that have pre- vented this phenomenon from reaching the proportions of a huge global economic catastrophe: 1) the accelerated modernization and urbanization processes experienced in Asia (China and India in particular); 2) the stabilizing role played by the United States as when they carry out Keynesian policies such as centralized expenditure and quick decision making (i.e.: the increase on the military budget and expenditure). This kind of expenditure cer- tainly spreads activity over every industry, References [30-31], though more on some than others; it would be naive to believe that the so called Military Industrial Complex consists only in bomb factories, or that its be- coming a civil industry is a simple process, References [32-33]. This last type of “neo-Keynesian” response has serious implications regarding domestic and foreign fi- 1Unless technological change entails a substantial increase in produc- tivity, which is not usually the case when already existent products are changed. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  R. KOZULJ485 nancial imbalance, the rate of currency issuance, the creation of highly volatile financial markets, and other questions that could not be dealt with here but that con- form, in turn, the context of growing interdependences and complexity approached in this paper, which focuses rather on the real, non-monetary aspects of the economy. The equations of definition and equivalence of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and Adde d Value (AV) help to clarify this point. As it is known: (1) , where GDPC IXM C = consumption; I = Investments; X = exports and M = imports, and (2) 0nn , which means that in- terannual variations, or longer period variations can be defined as the addition of the initial product of a given year and the variation produced during the following period, which can be either positive or negative GDPt GDPtGDPt At the same time, n can correspond to varia- tions of the components in GDPt ,,CIX n t (3) A VRCRRF where AV = Added Value, RC = Return on Capital y RRF = Return on the Rest of Factors, by definition being . GDP AV Now, if we disintegrate equation (1) in a way that we can distinguish investment linked to infrastructure (t I f), to the creation of pr odu ctive cap acity o f tr aditio n al goods (t I Ctr ) and to the creation of new products characterized by fast innovation and technological intensity (t I Np ), and we subdivide consumption into the most dependent on incomes related to wages sum (t) and into the sectors that are owners of production units or earn the highest incomes due to high specialization or to privi- leged participation in society (), Equation (1) be- comes: CMs t pCN (4) tttttt GDPCMsCNpIfICtrINpX M In turn, , tt t I fICtr Urb, t I f y t I Ctration will pend on all in investment rates, no matter th sides, as de t Urb bei at a specific momen time. If a ecline in the increase in the long term is foreseeable, a slow down in the process of invest- ments induced by the urbanization process is to be ex- pected. It must be remembered that initial infrastructure is always built with long term aims in mind and with the productive capacity thinking of products with longer life cycles, Reference [34]. As is well-known, a f ng t Urb th de urban popul t in e reason, causes recession and economic cycles. Tradi- tional anti-cyclical measures may not be effective when there is a context of overcapacity in a sector whose own intrinsic nature prevents it from liquidating stocks, as it is not serial massive production. Therefore, a recession caused by this kind of fall in the investment rate produces a decrease in the tot al leve l of ac tivity. In an L recess ion lik e this one, activity experiences a longer drop period and also generates a threshold that is even lower than that in U re- cession, where there is prompt recovery and the possibility of getting back to the growing path, References [35-38, 10]. Be t I f and t I Ctr e proproportions in the total in- vestment dimin and thportion of the t ish I Np type of investment increases, RRF will occupy a l propor- tion inside esser A V2. Thisaffect t CMs , aggravating the structural crhat gives birth to asociety. The pro- ductive sectors linked to t CMs , t will isis t dual I f and t I Ctr that used to support the Fordist mo longer observe old game rules. These rules included increased salaries and productivity, steady employment and basic needs granted by the Welfare State, and Keynesian anti-cyclical policies. In such a context, if investments are influenced by the odel can n ur ts and im- po banization process and their dynamics decline together with it, the GDP will only be able to grow if either total consumption or exports, or both, grow too. At a global scale, the combination of all expor rts are equivalent. Therefore, they could not contribute to the global economic dynamism if products were the same. As has already been said, consumption heavily depends on the remuneration of the other factors, or on the access ca- pacity that the financial system permits and can afford ac- cording to its own rules, which, however, cannot be com- pletely oblivious to the repayment capacity of debt holders without undergoing a crisis. If the decrease in the invest- ment associated to urbanization as an integral process (in- frastructure and productive capacity creation) was replaced by the creation of new goods, there would be an accele- rated technological change linked to shorter life cycles. As 2Distribution function of the social product corresponding to factors other than capital (basically salaries and taxes) is represented in a sim- p lified way, with a formula that considers simultaneously the prod- uct-capital relationsh ip and the factor return on capital: 11CCiin or, which is the same 11GDPC iin since C = GDP where is the social product that rewards factors other than capital. is the value of the product-capital relationship C is the value of capital GDP is the gross domestic product equal to added value and the ex- p ression [i/1-(1+i)^-n] is the factor of return on capital, being i the discount rate and n the period for capital return. value increases when the relation product-capital grows (capital intensity decreases), which is trivial; but it decreases with decreasing values of n in a non linear way. Indeed, obtaining from n we get the following: **ln11212 2nCiiini n which indicates the positive sign of the derivative ( grows when n grows, or decreases when n does), but according to a quasi hyperbolic function, thus showing the particular sensitivity of the function with respect to the range of n values, specially in the cases where n values are less than 15 years. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  R. KOZULJ 486 considerations have anything to do w more detail: To t horoughly explai n the phenomenon of rural-urban migration and mar- gi h have conceptual, empiri- ca a consequence, the proportion of the product that returns to the rest of the factors would decrease, posing an obstacle for consumption enhancement, at least for a major propor- tion of the population. This point will immediately be taken up again. Before that, it is important to highlight that an internal fracture of the productive apparatus is the matrix for generating a dual society. It leads to a wicked dynamics: for those who have access, the range of available goods and services widens and becomes more diversified while, for the rest, it beco mes h arder to s atisfy even their basic need s. Foreign trade may boost growth in some countries but, by definition, it is incapable of achieving it at a global scale even though it may be acting as an incentive for moderni- zation as the urbanization process has not yet been com- pleted a global scale. That is the case of Asia today, spe- cially that of China and India, maybe even Brazil in Latin America, but it will no longer work once they complete the process. Efforts to secure markets become a priority in each nation, but this cannot trigger a larger global dyna- mics if such growth does not imply involving the urbaniza- tion process, an important part of the commodities and capital goods market. Do these theoretical ith the character ization of the world economic cr isis a s of 2007 - 2008 to the present day? The answer can only come from the theoretical framework within which these crises have been interpreted. In general, they are analyzed ac- cording to their financial aspects, in turn considered the cause and not the consequence. Since the link between the financial sector and real economy are certainly interde- pendent, such explanations should at least be accounted for because of their conceptual soundness, as a necessary com- plement to formulate explanatory hypotheses of a wider scope. One urban marginality in the Third World and in some cases in the whole world—a hypothesis describing the different stages which are produced by this dynamic and interactive process is needed. This process includes urbanization, in- dustrialization, “de-industrialization”, “dematerialization of economy”, and technology and productive structure change (Diagram 1-Section 4). Indeed, the link between nality can be explained in the following way: During the upward phase, the urbanization process attracts human masses that come from rural areas. In general, these people, especially the less qualified, will work in the construction sector, in services that do not require high skills or will become industrial workers. As the urbanization process loses its initial dynamism, the number of workers offering their services exceeds the demand. As this process has lasted for a while, th e migrant generation has alread y have offspring born in the city. However, the cultural features of the family environment make it difficult for the offspring to develop the necessary skills and to acquire the necessary knowledge to perform successfully in the new urban sur- rounding at more m ature stages. These youngsters born in a totally urban culture hope to reach a standard of life that society introduces as attainable to all. Not only the media suggests this through advertising, these values are fostered in the educational system and in the modern political pro- ject, no matter how blurred it may seem today. But their realities at home prove the opposite. Their parents, who used to be workers—whether members of a union or not and were guaranteed a job, start facing a different labor reality. Job opportunities become more sporadic and the access to new goods more difficult, or even impossible. Female jobs for these social sectors tend to be related to domestic service and other badly paid sectors. The combi- nation of wages of both members of the couple cannot af- ford what only one of them could in the previous period. For the generation of those parents who lived an even harder reality in the rural zones, urban life still constitutes a better option. They are not likely to wish to go back t o thei r origins an d rural task s. They try that their children enjoy an improved standard of living. But which hope can those urban youngsters have when they sense the harsh reality surrounding them? Is it so strange then that many of them try to fulfill the promises that both society and their parents have made by other means? Can the traditional values of their parents survive this situation and perpetuate through generations? As from 2005 at least unemployment rate for youth double or more the same rate for the adults in most of the countries, but in Brazil, México and Perú, the rela- tionship can reach 250%-300% or more, despite lower unemployement rates in this kind of “new prosperity” era based on high prices for exported commodities (i.e. 2003-2008), Reference [39] If these hypotheses—whic l and theoretical support—are relatively right, then, what will happen with the world economy once the ur- banization processes are completed or saturated at a global scale? There are many answers because the world, as well as its future, is still open. What happens tomor- row will depend on what is decided today, even when there is an almost irreversible inertia and latency. There might be unexpected technological revolutions; there might be a program of systematic destruction to “rebuild the destroyed”; wealth might be redistributed; urban de- centralization might take place, constituting a new form “creative destruction” (as Schumpeter said); the catas- trophe might eventually break out which in musical terms, according to the Greek, was the return to a point of rest and axial equilibrium of th e lyre strings after they have ceased to vibrate. The serious problem is that it stays a mystery who is or are the ones who have the an- Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  R. KOZULJ Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 487 s should be ap- pr . The Prospective of Population Dynamics ral earing in mind wh at has been said ab ove, rural popula- tre exnt, in Latin America. It is clear that these trends ver, the most striking fact is that, contrary to w the one hand, that the economic gr te suppose a fast rural-urban migration process whose mag- nitude would be unprecedented in Asia and Africa (Fig- ure 2). Howe swer to these matters or at least who are analyzing them, and which conclusions they are drawing. Therefore we have overabundance of contradictory information com- bined with lack of essential info rmation. Nonetheless, all these interdependence hat happened between 1950 and 1975 and between 1975 and 2000, by 2025 the urban growth process at a global level would represent 97% of the expected total population growth. This means, on oached. The design of a “creative solution”, a win-win scenario, would also be welcome. But this will not emer- ge from pragmatic thought, or from economic fusion, continuous downsizing or from speeches in favor of glo- balization that improve microeconomic profitability but do not improve return at macroeconomic levels. Or, of course, from empty speeches against globalization and its wicked effects. And even less from the current goals regarding poverty reduction, which are based on incon- sistent programs at a global scale (for instance, Latin America has had to grow over 4% p.a. in order to avoid the increase in the absolute value of the number of poor people, Reference [40]. owth boost coming from the urbanization process and rural-urban migration that is, the , tt t I fICtr Urb com- ponents of the equation: tttttt IfICtrINpX MGDPCMsCNp will progressively decrease in the next two decades, a market for ev process that will have all the consequences described in Section 2. But besides, urbanization will no longer have the role it had for more than two centuries as a future growth drive, though specifically between 1950 and the present day. This would undoubtedly influence a large range of productive activities related to the construction, equipment, infrastructure sectors, and others. At the same time, the total consumption 3and Its Consequences on Economic Growth and the Displacement of Ru Poverty into Urban Areas eryday supplies, such as food, energy, services, as well as industrial products for massive consumption will have a much larger dimension than in the past, producing a rise in demand and the need for continuous supply of raw mate- rial, energy and natural resources. The dynamics of these markets will depend, without doubt, on the access to them according to income distribution. And by the way, the rise in the price of raw materials (oil between them) also has to do with this structural trend recorded as of 2003 to 2011 in spite of the world crisis- and which is generally attributed to the role played by Asia in global growth. B tion growth trends recorded and projected at a global level and by regions (Figures 1 and 2) reveal several aspects from which some of the main challenges to be faced in coming decades can be established, many of which are already present in the current global situation. Figure 1 clearly shows that, as of 2010, projected nds indicate a decrease in the absolute number of pe- ople living in rural areas at a global scale and in all the regions, except Africa. Likewise, most of the increase in urban population would orig inate in Asia and, to a lesser Figure 1. Historical trends and projection for urban and rural population growth in large regions: 1950-2030. Source: United Nations, Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, World Urbanization Prospects: The 2001 revision.  R. KOZULJ 488 -200000 0 200000 400000 600000 800000 1000000 1200000 Population vari ation (thousand) Africa Asia Europe Latin America North A merica Oceania Africa 87473133142 228288 196530 430898 166301 Asia 414005 675915 865711 4142031105926-66982 Europe 163764-4651853355-25688 5025 -55613 Latin America147967 22671 195870-121176731-10645 North America63356 4796 69173 399477283-9162 Oceania 7110 1350 8246 16957897 1403 Urban RuralUrban RuralUrban Rural 1955-1980 1980-2005 2005-2030 Rural population grows faster than urban in Asia y Africa betwee n 19 55 an d 198 0 and continues growing durning 1980-2005New trends: except in Africa, lmigratory pr oce sse s will b e so relevant than rural population will decrease Figure 2. Historical and projected demographic trends: rural and urban population increases in three periods 1955-2030. Source: United Nations, Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, World Urbanization Prospects: The 2001 revision. 51% 79% 97% 0 200000 400000 600000 800000 1000000 1200000 1400000 1600000 1800000 2000000 1950-1975 1975-2000 2000-2025 En miles de personas 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% % sobre el total del incremento de la poblaci髇 mundial Urban Population Increase Total Population Increase % of increase attributable to urban population Lineal (Urban Population Increase) Lineal (Total Population Increase) Figure 3. Increase in total world and urban population 1950-2025. Source: Source: United Nations, World Urbanization Prospects, The 2001 Revision, New York, 2002. Now, according to what has been said about the need to replace yearly product quantum of one sector with that of others (that is, the need to replace the decrease in product quantum of the sectors linked to infrastructure investment (t I f) and those closely related to the wage bill or to income from informal labor (t I Ctr CNp t), with the product quantum related to investment and consumption of new products and services with a shorter life cycle and accelerated obsolescence cycles t e t CMs I Np ), there would also be, at an unprecedented scale, a structural in- Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  R. KOZULJ489 crease in the restricti on on redistributi on improvements in a context, which, as has been said, would have a lesser global dynamics, greater physical productivity due to technologi- cal development and, consequently, fewer job opportuni- ties. The hypothesis to be analysed in this case is the following: If it is accepted that for each consumer good, market development in the long-term has the form of a logistical function, its first derivative will represent the projected demand in time for the capital goods industry for that good. The second derivative will be the projected de- mand for the capital goods industry for the production of capital goods for the first good, and so will happen indefinitely. This is so if it is accepted that the capital goods industry is not homogeneous with regard to its products, as generally assumed. It is almost evident that th e concrete process of econo- mic growth is, in fact, the overlapping of the “supply = demand in time” function for different goods. Conse- quently, the aggregate demand will decline at the same pace as the decline of the capital goods demand, if there is not a process of continuous technological change3. In simplified terms, each product will grow endlessly or in an exponential manner, provided there are no restrictions according to a function of the type et Pt Po where is growth (generally expressed in %), P(o) is the initial magnitude of the market for a certain product, i.e. the value of P in t = 0. But, actually, each product has an exponential growth phase and it then reaches saturation as a consequence of real demand. This saturation is equivalent to the number of people who can afford such product, which means that they do not have it, and that they have the want and the means to acquire it. Therefore, it has been usual to add corrective factors to equations of that type, i.e.: 1Pt k in a way that the growth of the referred variable (in this case a product) diminishes as the k variable is reached. This variable represents the asymptotic value towards which the function heads (in this case the maximum market size for a certain product, and also the maximum size of urban population during a certain period). In this way, the growth equation can be expressed as follows: 1 Pt Pt Pt dt k i.e., as a typical logistical function. The solution to equa tion (2) is 1e t k Pt Now, the first derivative of this function (in this case, the projected demand of capital goods for the product in question) will be: 2 1 PP PP dtk k P The main concern here is to find the maximum of this function, because from that point on, the capital goods industry in question will enter a phase of structural overcapacity due to saturation (and so will some other sectors as a result). The maximum and minimum of this derivative func- tion P t are obtained by identification of the t’s that result in 2 20 P t . 2 2 22 1 dP PP PP dt kttk t Two of the points at which this function becomes 0 are clearly trivial: (t = 0 and t = ), then 2 10PPtk k 2 , which is equivalent to * *1e 2 2 1e t t kk And hence, * e1* tt 0 Wit h which * o * 2 k tt It means that, in this case, the t* time searched for, in which the first derivative reaches its maximum (pro- jected maximum capacity in the capital goods industry corresponding to th e consumer good in question), will be the time needed for the market to reach half of its maximum magnitude. This reasoning is not altered if, instead of adopting this form, the logistical function was slightly different. In that case, P(t*) would not be 2 k, but something similar. The reasoning underlined here is that as long as the markets for the different goods behave in a way similar to a logistical function, the investments induced by these sectors will decline at a point in which signs of great dynamics in the industry in question can be observed, whether it is of consumer or investment goods. (2) 3But this “continuous technological change”, implies shorter lyfecycles and it is not help to improve income distribution as just said above (see footnote 2). Therefore, industries produ cing capital goods will ine- Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  R. KOZULJ 490 vitably reach a phase of structural overcapacity that will affect the dynamics of economy as a whole through the multiplying effects caused by the reduction in aggregate demand. The response to this will obviously be technological innovation, which will allow the industries to remain in the market, creating new sources of supply and demand. But this will not be possible in all sectors to the same extent, due to the heterogeneous and rigid nature of the production system. When, instead of considering one product, a group of products is considered, related to what could be called a paradigm of technological consumption (a cluster of goods which characterise a certain lifestyle, such as the modern urban style, for instance) and these products have developed practically along the same period, the described effect for one product, will affect economy as a whole. This could be virtually represented as the aggre- gation of varied logistics or similar functions, each corre- sponding to a good or service. Th erefor e, it is not eviden t that the process of technological change can per se main- tain the dynamics of economy at the same level as during the initial phase of development (for example, the first two decades after the Second World War). This gave a reason for the rupture point associated with the decline in urban pop ul a t i on growth. Though none of this is totally predictable or impossible to change, these co mplex interdependences do not seem to be part of present-day agendas on growth, financial crises, poverty and the challenge all this poses also for the energy sector, particularly in the link between urban poverty and energy access. Nor is it frequent to assume that the dyna- mics described here be the main cause of change in the productive structure, with a greater impact on service acti- vities once urbanization reaches its saturation in each n a- tion and region and, finally, at a world scale and that consequently—there is no other activity sector capable of absorbing the labor that is progressively displaced, nor a universal extension of services compatible with a dual so- cial structure. Can “the sixth Kondratieff long waves of prosperity” based on Environment technology, Nano-Biote- chnology, Health care an new goods and services, Refer- ence [41] change the structural world crisis? The previous rationale about the complexietes and interdependences of the global context bring out a lot of questions and weak responses from theoretical side of the question, because there are not a single quantitative analysis to prove how these “new wawes” will replace the slowdown in the whole of another “current” activities. 4. Impacts on the Energy Sector The growth dynamics described above have many dif- ferent impacts. Most of the ones considered in th e litera- ture have to do with issues such as security supply, envi- ronment and energy efficiency, concerns mainly related to the impact of energy demand growth at a global level which has been boosted ever since the beginning of the past decade by China, India, Brazil and other countries on available global resources and on carbon emissions at a world level. The current way of keeping up this growth implies a great energy expense, but also growing access demands by the sectors with little payment capacity. That is, the progressive setting of new and larger thresholds of stable demand, where this last factor—energy access by the “urban poor” is just one of the multip le factors he lping to conform such threshold. In spite of the great effort to diversify energy supply sources, a major part of them will continue to depend on non-renewable ones. Likewise, the trend towards a major use of biofuels in order to improve supply security, may have—together with other factors related to urbanization and implying a larger demand of agricultural and forest products—an impact on the price of food. This may be good if the goal is to sell more. It may be bad if the aim is to keep the economy and the standard of living in a state of increasing satisfaction, or at least to keep it stable for many coming generations. But there is another more evident aspect, and the seri- ousness of it will become clearer the next years. The axis of poverty is moving by leaps and bounds towards urban poverty, Reference [42]. Even when the explana- tions of its genesis may differ from the ones presented here, it is acknowledged that the fact is real. Urban poverty is different in character from that pov- erty entailed in the traditional ways of living of the “backward” areas of the planet, of the “rural areas”. To satisfy the energy needs of the urban poor, non-conven- tional sources are of limited help. Electricity, Kerosene and LPG are basic for the urban poor. Will they be capa- ble of affording the cost? Will the companies be capable of satisfying this demand and recovering all their ex- penditure without subsidies or of giving an integral re- sponse to the phenomenon of urban poverty? Even more, will they be able to do it if it is also necessary to reduce carbon emissions, which implies larger generation costs or more capital-intensive uses to capture emissions or more costly ways of generating and supplying electricity? This issue is partially dealt in the following section. Meanwhile, it is important to note that we are confront- ing a major information deficiency problem in relation to all these matters. Many countries do no publish their statistics about poverty when it increases because that would be “politically in correct”. Oth ers, developed coun - tries for example, do not consider it necessary because it Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  R. KOZULJ491 is assumed that they lack of poor people, which is of course erroneous. Product statistics are a disaster, they mix too heterogeneous numbers with prices not well- corrected. There are not enough statistics about salaries according to activity sectors for every country in the world, which could be used for comparison. There are no sufficiently detailed data on capital stocks or production capacity according to activity sectors, and even less by key products. There is scarce and inaccurate information about poor people regarding their knowledge, education, skills, and many other areas. Economy growth projec- tions are of a voluntary nature, and never clearly ex- plained. It seems that we are entering a new era with practices, tools, thought habits and action corresponding to a world in progressive extinction. All of this does not help much to think and act correctly in the face of the major chal- lenges of the XXI century, or even to contrast complex hypotheses in a complex world , full of interdependences. 5. Urban Poverty and Energy: Why Has So Little Attention Been Paid to It When It Is Going to be One of the Greatest Challenges of 21st Century? As in almost every field, there may be many hypotheses or an exaggerated claim. An attempt to explain both po- ssibilities will be exposed here. To find out why the rela- tionship between urban poverty and energy has not been dealt with the deepness it deserves. The explanation will be once again linked to the evolutionary perspective of the economy described in the previous section and also to what has been claimed about the indicators and their more notorious deficiencies to face new situations. Ordinary indicators used to determine poverty levels have been too vague. They have been more useful to determine the number of people who have no access to modern lifestyles than to identify specific poverty situa- tions. The use of a global threshold (i.e. population that lives with less than us$ 1 or 2 per day) has given place to a distortion which could also be found in the dominating approach used to deal with the energy-poverty link. Such distortion occurred because in most cases the indicators identified the number of poor living in rural areas (popu- lations with insufficient monetary income, but which do not reflect the incidence of non monetary economy ef- fects on family economy). Therefore, they tend to create a distorted image of the spatial location of the poverty map. In that sense, regions such as Asia and Africa call the attention not only as regards the issue of poverty as such, but also as regards the links between energy and poverty, at the core of which there was access to energy by a rural population lacking electricity and other mod- ern sources of energy (LPG, Kerosene, efficient use of biomass, among others). In a leading work carried out for the World Energy Council, Reference [43] about this issue (focused in the Latin America context), after reviewing over 150 docu- ments, it was found that the greater number of works were focused on rural poverty. Even when the relevance of the problem of urban poverty was acknowledged, in most cases the works contained only scarce references to the topic and a few suggested solutions. Diagnosis was limited, in most cases, to point o ut the different nature of the problem: “while urban poor are at risk of having energy services interrupted for nonpayment, rural poor lack such services”. In that way the dominating appro ach was basing the solution on the promotion of new sources of renewable energy, with the acceptance that such ac- tion requires an active government policy. The argument was, then, about type and form of subsidies (their aim, duration and features), and not about their need and the benefits they would provide; these elements were just taken for granted. On the other hand, there was no equivalent in subsidy proposals or active policies for urban marginal sectors. The only exception were some references to the advantage of canning LPG in smaller containers or installing “pre paid meters” for electricity. As it was said, this “would enable the poor living in ur- ban and periurban areas to obtain energy according to their eventual and fluctuating incomes”. But the new productive modality observed at the mature state of ur- banization is precisely characterized by unstable incomes. The difficulty to create stable jobs that are linked to a high productivity results in these unstable, insufficient and fluctuating incomes. In such a context, the above measures are an adaptation of the market to the incomes of the poor, but not a contribu tion that will help alleviate energy poverty. It is widely known that of the main obstacles for the access to electricity services is a high cost of connection, especially due to the meter’s cost and users payment ca- pacity. However, the predominant issue was downsized to how to avoid “energy non technical losses or robbery” that is, the problem of users illegally connected to elec- trical wiring. In the case of LPG, it refers to problems caused by subsidized prices. Nevertheless, there are no other thorough studies about the energy needs of the urban poor on a global scale, or the complex relation among the different stages of the urbanization process, or the nature of urban pov- erty and marginality. There is also a lack of studies de- voted to the identification of that sector consumption patterns or to determine their real possibility to get regu- lar energy access that permanently satisfies their needs. But as the urbanization process in Asia grows, the ap- Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  R. KOZULJ 492 proach on the problem of poverty in urban and periurban areas and on access to energy will become increasingly relevant as a consequence of reality dynamics at a global scale (See previous Figures 1 and 2). This will be par- ticularly the case in developing countries (Diagram 1). This obviously fosters rural-urban migration, which in time contributes to increase the rate of activity: migrated people adopt modern patterns of consumption. Never- theless, as cities (or the urbanization process) lose dyna- mism, the decrease of stable employment opportunities and the increase of required qualifications gradually lead to the phenomenon of structural poverty. Its significance will also depend on the nature of “adjustments” in eco- nomic policies, but that process factors are always un- derlying. The first migrant’s offspring will then grow in an alien surrounding, considerably different from their cultural background and will often be involved in a con- text of scantier employment possibilities (in developed countries this may happ en with the immigrants from less developed countries). Besides, in many cases they will be poorly prepared to attain the job positions that the new urban context offers. In this new setting, the struc- ture of activities shifts from building and industries to services. Moreover, there is a trend to increase produc- tivity not only in agriculture and industry but also in the area of services. Total employment supply decreases and the emergency of structural poverty takes place as “a natural consequence of the economic growth modality” As example more than 20 million jobs have been de- stroyed in the recent world crisis. Only in the United States about five milion jobs, 66 percent of them from the construction and manufacturating sectors, Data from Reference [39]. What will then happen with access to energy and possibly more expensive food? How will investors or social security systems, among other stake- holders, deal with this? This seems to be a worldwide process even though there are differences depending on different factors: each country’s previous stage of development and technology, the quality of its institutions, the educational level of the population, its particular insertion in the world’s trade and the specific features of its culture (which highlights or mitigates the phenomenon of urban structural poverty). This is intensified by the fact that mature economies have products with shorter lifecycles, which is in itself a constraint to improve income distribution. Even though the situation is more serious in developing co untries, this whole process is affecting the developed world as well (poverty in the EUA has increased constantly since 1980 and in Europe the phenomenon of unemployment and its relation with immigration are clear signs of this), Refer- ences [44-46]. There is constant debate on public budget adjustments and the collapse of the “Welfare State” in Europe, as well as on the role played by immigration barriers in periods of crisis in developed countries now facing problems that no one thought of a few decades ago. The 2008 financial crisis does not reveal so much and only the second ary financial market pr oblems, as the limits imposed on consumption and access to essential goods and services by the lack of payment capacity. This, in turn, depends undoubtedly on structural problems with interdependences that become gradually more complex. A simplified representation of the phenomenon was shown in Diagram 1, which presents the different stages of the urbanization process through time. The links for each stage are described according to facts that took place in a large sector of Latin America in relation to energy services and the nature of the poverty issue. As regards changes in the structure of activities, trends be- tween 1975 and 1995 should be noted for both developed and developing countries. Therefore, it is highly pred ictable that one of the main problems in the future concerning energy and poverty will be how the urban poor will be able to become con- sumers of the modern sources of commercial energy in a manner that is sustainable in economic, social, political and environmental terms. Since the dominating trend is to consider the “Welfare State” as an obstacle to a more competitive economy in a globally integrated world, this problem becomes even more serious –or almost insoluble if the productive approach is not modified. Although Diagram 1 refers mainly to Latin America within the developing world, the dynamics shown in its upper part are not a mere particular regional phenome- non. They have a universal character and could be ap- plied to almost every LDC, even to developed countries, due to the increasing interdependences. These dynamics are the consequence of the parallel evolution of interrela- tional processes like urbanization, growth, and techno- logical change that characterize modernity and are even independent from the “socialist or capitalist” economies References, [9,10]. The demographic predictions shown in Figures 1 and 2 anticipate that it is very likely that growth will slow down in a decade’s time or even before, because the installed capacity increases to respond to markets which are considered dynamic when decisions are taken. But little after this, these markets may get saturated, creating a huge gap between the financial cu- mulative capacity and the possibilities of carrying out that accumulation through investments where capital can be recovered as predicted . The likelihood of L recessions (those that produce permanent destruction of the installed capacity and di- minish the depth and duration of the threshold from which economy recovers) rather than U recessions (short cycles) will increase. In fact, growing tendencies, when Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  R. KOZULJ Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 493 Diagram 1. Representation of the process of development of urban structural poverty and the issue of access to public ser- vices in developing countries: urban population curve rate and stage determination. Source: author’s work. affected by factors such as energy or financial crisis (which are usually mistakenly introduced as ‘causes”) show a declining line as indisputable stylized facts when the evolution of global rates between 1950 and 2010 are represented at global scale. China or India may grow at a rate of 9%. Angola too, but only because of an oil bonanza. Countries such as Argentina or Japan, are recovering from the L recessions  R. KOZULJ 494 that they have experienced after each of the changes of the macroeconomic model that took place in the last 20 years, in the first case, or as of 1990 as a structural phe- nomenon in the second. As for the United States, rates of about 3 or 4% were acceptably optimistic until 2007; nowadays, 2% - 3% rates are welcome after the 2008 - 2009 crisis. For many countries in Europe and also in Japan, rates have been low or even negative in the last years. Global economy grew at 3% before the crisis, but, which will be the rate in the year 2015, not to think of 2020 or 2030? Which additional product will help to reach those percentages, figures? Which are the sectors and technologies capable of giving them support basis? With which lifecycles? How will an opulent society be- sieged by the poor around them react? We have already seen walls falling and being erected in very few years. By the way, Rome is a good place to think this over: The way from Porta Pinciana to Porta Nomentana reminds of the place where “I Galli di Brenno” came in 390 BC.; “I Visigoti di Alarico” in 410 AD.; “I bersaglieri di La Marmora” in1870. Walls always mean “leaving the other outside” and “protect the ones inside”. But they are not impassable. If violence is not the strategy underlying some minds or the natural outcome of a situation flooded with threatening elements, another scenario will require lots of wisdom and joint efforts. In his last years, Peter Drucker predicted the arrival of a society with a new gravity center: “the greatest changes are almost certainly still ahead of us. We can also be sure that the society of 2030 will be very different from that of today, and that it will bear little resemblance to that predicted by today’s top-selling futurists. It will not be dominated or even shaped by information technology. IT will of course be important, but it will be only one of the several important new technologies. The central fea- ture of the new society, as of its predecessors, will be new institutions and new theories, ideologies and prob- lems” Reference, [47]. It would be interesting to note that in such context the “prophet of management” predicted the question of ageing in Europe and the economic prob- lems that would afflict Japan, even when nobody talked about that. So his comment may b e taken as the warning from somebody who deserves special respect and should be listened to. 6. The Inadequacy of Institutions and Thinking Habits: Towards a World Agenda For the past years, a lot has been said about promoting education and impr oving the qua lity of institution s as the proper means to contribute to the endogenous develop- ment in each nation Reference,[48]. But what remains a bit unclear is if this statement is adequately considering the implicit complexity of the current world, whether the opinions on this subject are based on a right diagnosis of reality. To educate for what? What knowledge is to be transmitted? To whom? In which context? There is still debate around issues like “market solu- tions”, the need for more State intervention. Should sub- sidies be granted or not? In the final analysis, these are discussions between neoliberalism and Keynesianism. Are these discussions useful or do they just get in the way? The need of new indicators is also mentioned, but do we know which? To what purpose? There is a lot of talk going on and not much is said. And then we are sur- prised that th is world is go ing throug h an era in which , in Bauman words, Reference [49], “lack of protection, un- certainty and insecurity are the key features of the pe- riod”. However, this is not surprising at all if we think that the global productive system increasingly resembles a drifting ship: its direction depends on the Captain of the moment, let it be planned movements or hazardous alternations. But the overall perception is that the boat is or will be sinking at any moment. And perception pre- cedes action because it shapes thought. Clearly, eradicating extreme poverty will become a complex issue and it will challenge the simplicity of those that think a redistribution of income is enough, bu t also those that think there is not such need. Many other modifications will be required: 1- a reorientation of the supply and its structure; 2- changes in the investment process and the rules of return; 3- changes in production and consumption guidelines; 4- changes in the attitude towards work. Apart from this, new capacities and agile and operative institution s, based on more accurate know- ledge, will be certainly needed. New institutions also means a new way of thinking business organizations and the logics that rule production, its ethics, its purpose. This may sound utopian, but the subtlety may be that an excess of optimism is in fact identical to the crudest skepticism. But if we do not start to feel concerned about all this, what is the business atmosphere going to be like in a couple of decades? For how many people will what be produced? W ill it b e n ice to liv e in th at world? Maybe it will, the lucky survivors will think. But maybe they will be dreadfully mistaken. It is evident that the problems entailed in the future supply of energy does not solely depend on how demand is to be satisfied, but also on how should it be modelled according to sustainable guidelines, which means recon- sidering growth, social organizations, and their rules. A known link. But feared. Thus, absent from acceptable dis- courses. Again, the issue of information becomes crucial. In the first place, conscious intellectual efforts should be made to reinterpret the need of creating more detailed and accurate indicators, based on the generation of pri- mary information systems. These systems should, in turn, Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  R. KOZULJ495 be capable of assessing the running of economy by com- bining the evolution of specific products, consumption, real poverty and its economic and cultural causes instead of relying -as it is usual today on generic, inaccurate and vague data, with all that misleading aggregates, full of omissions and with no methodological unity. Is this too exaggerated? Anyone who thinks so should check the quantity of … or NA in data cells according to countries in databases like the online WDI of the World Bank or try to search long term series. Besides, these data do not reveal too much about the reality that should be neces- sary to comprehend. It would be constructive if the spe- cialists of each small area of knowledge that makes up the previously identified interdependences provided a synthetic view of the situation for their area. Then, the information on interdependences should be compared to another piece of information. The interaction of both data will determine which new interdependences must be studied to eventually produce a spectrum of views about a possible and desired future –which means creating a more precise image of an inclusive instead of exclusive society. And so new institutions, behavior and thinking habits are essential. As well as a reorientation in research and in the way research resources are spent. For example, it is usual that institutions hire studies expecting results in three or six months. Many times, these studies are repeated more than once, leading to many versions of the same question. The results entail thousand s of superficial pages on the same subject, with not very reliable conclu- sions. Why not replacing that with long term research programs to orientate decision making for ticklish issues on the basis of a more detailed knowledge? Is it not bet- ter to spend more time in what is crucial and deserves attention instead of making urgent decisions based on reliable knowledge? Of course it is. Unless the point is to support a decision that has already been made. In that case, the other option seems logical. But dangerous. Appreciations on delicate subjects cannot be ideology- cal, or at least not too ideological. They require aware- ness, which is not the same as overabundance of infor- mation or quick access to it. The object should be a stable economy that satisfies different needs, that reconciles social differences without aiming at an “ideal” equality that is unattainable in the same way as it is impossible to think of high quality of life in a context of extreme inequality. Automatization is within our reach, concerning know- ledge and possibilities, but how to use it in a reasonable way to produce a better world is not. An economy with product life cycles that become shorter and shorter uses up human and natural energies and resources. Thus, we should analyze how we can go back to longer lifecycles with high technological content, without stopping innovation, or worsening anybody’s position or enjoyment, but channeling it under Global and Contextual Rationality. This involves responding in an operative manner to the question of how production should be reoriented in order to satisfy everyone’s basic needs, while keeping those who already enjoy a wealth of goods and services happy. This is not incompatible with freedom and does not necessarily lead to a collec- tivist society. The idea is trying to discover under which conditions that kind of society would be possible, under which motivation and profitability ru les. To outline a ge- neral view, shared by nearly all, and then refine it and eventually implement it. Only under this set of guidelines the discussion about improving education and institu- tions makes sense. If not, we are to expect more of the same. And it can already be seen that “the same” poses a serious problem to all of us. To those who are suppo- sedly in a privileged situation and to those who do not have and will not access to basic goods and services unless the basis from which the productive service has evolved until now (bringing us to a non very promising present) is reconsid ered. So there is urgent need of a World Agenda. This may sound utopic, but an agenda of this kind, though imper- fect and weak as it may be, already works for issues like global warming, product quality norms, etc. So why should we think that it is not feasible to prepare a future on non catastrophic basis? Is it due to a mind habit or an unmodifiable humane nature? In any case, doubts add some color to the discussion, and anything that brings color gets closer to creation, which is not either black or white, or grey. And whether we like it or not, we are part of it. And as part of it, we are partners, co-creators. The ones building our reality day by day. And just as the less aware of himself the less free and happy an individual is, at a global scale the situation remains the same. If a bet- ter future is possible, it will not appear from a magician’s top hat, neither from the current approach on economic growth or the speeches and programs to fight poverty. The entire international community should be interested, investors from every area, in particular the ones in the energy sector, whose position is priv ileged at the time of leading changes. 7. References [1] K. Davis, “The Origin and Growth of Urbanization in the World,” The American Journal of Sociology, March 1955. [2] L. Mumford, “The City in History,” Harper & Row, New York, 1961. [3] R. Y. Herman and J. Ausubel, “Cities and Infrastructure in Cities and Their Vital Systems: Infrastructure, Past, Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  R. KOZULJ 496 Present and Future,” The National Academy of Sciences, New York, 1988. [4] G. Mensch, “Stalemate in Technology,” Ballinger Pub- lisher, Cambridge, 1978. [5] R. Kozulj, “La Crisis de las Teorías del Desarrollo Frente a la Crisis Global (Crisis of Development Theories in the Face of the Global Crisis),” AEDH-UNU Project, Internal Project Paper, 1986. [6] Kozulj, R. “Analizando el Motor del Crecimiento Econ- ómico Pasado en Función del Desarrollo Sustentable in Barbeito et al. comp. Globalización y Políticas de Desarrollo Territorial,” Universidad de Rio Cuarto, Córdoba, 1997. [7] R. Kozulj, D. Marco, E. Luis, Comp and CIEC, et al., “Megalópolis, Cambio Tecnológico y Crec- imiento Económico: Desde los Años Dorados a la Crisis Actual, in Humanismo Económico y Tecnología Cien- tífica: Bases para la Reformulación del Análisis Econó- mico,” De Marco Comp, CIEC, Córdoba, Vol. I, 1999. [8] Kozulj, R. “Urbanización y Crecimiento: Resultados de las Correla- ciones entre Población Total, Población Urbana y en Grandes Ciudades con el Nivel del PBI para Series de Corte Transversal a Nivel Mundial en el Período 1950- 1990,” Working Papers 03/01, Bariloche, Argentina: FB. Marzo de 2000. [9] Kozulj, R. “People, Cities, Growth and Technological Change: from the golden age to globalization, in Tech- nological Forecasting and Social Change,” Elsevier Sci- ence, NL. 70, 2003, pp. 199-230. [10] R. Kozulj and M. Y. Dávila, “Choque de Civilizaciones o Crisis de la Sociedad Global? Problemática, ” Desafíos y Escenarios Futuros, Editor: Madrid, 2005. [11] Okita et al., “Okita, S., T. Kuroda, M. Yasukawa, Y. Okazaki and K. Iio. Population and Development: The Japanese Experience,” Syracuse University Press, New York, 1979, pp. 327-338. [12] E. B. Masini, “Impacts of Mega-City Growth on Families and Households, Mega-City Growth and the Future,” United Nations University Press, Tokyo, 1994, pp. 215-230. [13] A. V. der Woude, A. Hayami and J. de Vries, “Urban- ization in History: A Process of Dynamic Interactions,” Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1990. [14] Black, Duncan; Henderson and Vernon, “Urban Growth,” NBER Working Paper 6008, MA, Cambridge, April 1997. [15] V. Henderson, “Urbanization in Developing Countries,” The World Bank Research Observer, Vol. 17, No. 1, Spring 2002. doi:org/10.1093/wbro/17.1.89 [16] J. Gugler, “The Urban-Rural Interface and Migration. Gilbert, A. & Gugler, J. Cities, Poverty and Development, Urbanization in the Third World,” Oxford University Press, London, 1993. [17] P. M. Hauser, “World Population and Development: Cha- llenges and Prospects,” Syracuse University Press, New York, 1979. [18] O. Coutard, “The Governance of Large Technical Sys- tems,” Routledge, London, 1999. [19] J. Summerton, “Changing Large Technical Systems,” Westview Press, Boulder/San Francisco/Oxford. [20] C. Marchetti, “Society as a Learning System: Discovery, Invention, and Innovation Cycles Revisited,” Technology Forecasting and Social Change, Vol. 18, 1980, pp. 267- 282. [21] A. Davis, “Product Complexity, Innovation and Industrial, Organization,” SPRU Masters, Sussex, 2003. [22] G. Dosi and R. Nelson, “An Introduction to Evolutionary Theories in Economics,” Economics Journal of Evolu- tionary Economics, Vol. 4, Springer, Berlin, 1994, pp. 153-172. [23] Ch. Freeman, C. Pérez, “Structural Crises of Adjustment, Business Cycles and Investment Behavior. Dossier et al.,” Technical Change and Economic Theory, London, 1988. [24] G. M. Grossman and E. Helpman, “Innovation and Gr ow th in the Global Economy,” London: The MIT Press; 1993. [25] R. Rowthorn, R. Ramaswa my, “Deindu strialization: Ca uses and Implications. In World Economic and Financial Sur- veys,” Staff Studies for the World Economic Outlook, Washington DC: IMF, December 1997. [26] W. J. Baumol, “Macroeconomics of Unbalanced Growth: the Anatomy of Urban Crisis,” The American Economic Review, 1967, pp. 415-426. [27] D. Harvey, “The Condition of Posmodernity. An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change,” (Spanish Transla- tion, Buenos Aires: Amorrortu, 1998), Basil Blackwell, Oxford, 1990. [28] A. Liepitz, “New Tendencies in the International Division of Labor: Regimes of Accumulation and Modes of Regu- lation. Scott, A.; Storper, M. Production, Work, and Ter- ritory: the Geographical Anatomy of Industrial Capital- ism,” Allen and Unwin, Boston, 1986. [29] S. Marglin, A. Glyn, A. Hughes, A. Liepitz and A. Singh, “The Rise and Fall of the Golden Age,” Helsinki, WIDER, UNU, 1988. [30] P. Dunne, “The Political Economy of Military Expendi- ture: an Introduction,” Cambridge Journal of Economics, Vol. 14, 1990, London, pp. 395-404. [31] D. E. Kaun, “War and Wall Street,” Cambridge Journal of Economics, Vol. 14, 1990, London, pp. 439-452. [32] Shenhar et al. “Shenhar , A.J. Hougui, Z., Dvir, D., Tis- chler A. Y. Sharan, Y., Understanding the defense con- version dilemma,” Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Vol. 59, No. 3, North Holland, Elsevier, No- vember 1998. [33] J. E. Ullmann, “The Military Industrial Firm, Private Enterprise Revised,” Cato Policy Analysis, No. 29, No- vember 9, 1983. [34] R. Y. Herman and J. Ausubel, “Cities and Infrastructure in Cities and Their Vital Systems: Infrastructure, Past, Present and Future,” The National Academy of Sciences, New York, 1988. [35] NBER, “US Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions, Home Page,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  R. KOZULJ Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 497 2009. [36] N. Roubini, “Please Consider Double-Dip Days by Nouriel Roubini,” En MISH'S Global Economic Trend Analysis. [37] “The US Recession: V or U or W or L-Shaped?” En RGE Monitor, 2008. http://www.rgemonitor.com/blog/roubini/252460/. [38] Romer and D. Christina, “Change in Business Cycles: Evidence and Explanations. NBER Working Paper 6948,” Cambridge, MA, February 1999. [39] ILO, “Global Statistics on the Labour Market page,” By_Country_FULL_EN.xls. [40] R. Kozulj, “Contribution of Energy Services to the Mil- lennium Development Goals and to Poverty Alleviation in Latin America and the Caribbean,” ECLAC, Club de Madrid, GTZ and UNDP Document Project, 2009. [41] Allianz Global Investors, Analysis & Trends, The sixth Kondratieff long waves of prosperity, January 2010. [42] E. L. Moreno and R. Warah, “21st Century Cities: Home to New Riches and Great Misery,” UN-HABITAT, State of the World’s Cities Report 2006/7. [43] C. E. Suárez, V. Bravo and R. Kozulj, “Revisión Bibli- ográfica sobre: Energía y Pobreza en América Latina y el Caribe, (Literary Revision on: Energy and Poverty in Latin America and the Caribbean) Work Record FB 5/01,” Fundación Bariloche, Bariloche, October 2001. [44] G. Duncan and S. Paugam, “Welfare Regimes and the Experience of Unemployment in Europe,” Oxford Uni- versity Press, Oxford, 2000. [45] R. Rorty, “Cuidar la Libertad,” Trotta, Madrid, 2005. [46] The Economist, “Inequality and The American Dream”, june 17 th-23 RD 2006. [47] P. Drucker, “The Next Society: a Survey of the Near Future,” Insert-Section in the Economist, Vol. 361, No. 8246, 3-9 November 2005. [48] P. Aghion and P.Howitt, “Endogenous Growth Theory,” MA: The MIT Press, Cambridge, 1998. [49] Z. Bauman, “En Busca de la Política,” In Search for Poli- tics FCE, Buenos Aires, 2001. |