Psychology 2011. Vol.2, No.5, 509-516 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. DOI:10.4236/psych.2011.25079 The Sexual Division of Household Labor Thomas V. Frederick1, Jack O. Balswick2 1Marriage and Family Therapy Program, College of Psychology & Counseling, Hope International University, Fullerton, USA; 2Fuller Theological Seminary, Pasadena, USA. Email: tvfrederick@hiu.edu Received April 27th, 2011; revised May 17th, 2011; accepted June 25th , 2011. Mounting evidence from both historical and social-psychological perspectives is pointing to the conclusion that evangelicals are relying upon patriarchal gender ideologies, specifically the male breadwinner and female do- mestic family roles, as identity markers to distinguish themselves from others in mainstream America. One would expect that gender ideology as an identity boundary marker would have little to no effect on the actual gendered behavior of evangelicals. The evidence from this study supports this notion in that three gender ideol- ogy scales constructed of attitudinal items were utilized, with limited success, to understand their impact on the actual performance of household labors. Keywords: Sexual Division of Household Labor, Social Group Identity, Subcultural Identity Theory Introduction Evangelicals have been known for their conservative reli- gious beliefs, especially regarding their views of Scripture (Bartkowski, 2004; Ellison & Bartkowski, 2002; Gallagher, 2003; Hunter, 1983, 1987; Smith, 2000; Smith et al., 1998). These religious beliefs have been used specifically as identity markers for evangelicals in both ethnographic and survey re- search. It is widely thought that these beliefs regarding Scrip- ture are the central domain for evangelical religious identity. Most types of research into evangelicalism logically begin with definitions. . For example, there are two basic theological tenets that Hunter (1983, 1987) has identified in theevangelical culture—Biblical inerrancy (The Bible is exclusively and ex- haustively true) and concomitant methods of Biblical interpret- tation. These tenets have been developed and adopted by other researchers from history (Collins, 2005; Sweeney, 2005) and sociology of religion (Hunter, 1983, 1987; Webber, 1978). However, both inside evangelical circles (Clapp, 1993; Lee, 1998; Van Leeuwen et al., 1993) and outside evangelical cir- cles (Gallagher, 2003; Smith, 2000; Stacey, 1990), there is a growing consensus that the family is becoming a core identity issue for evangelicals. Evangelicals are becoming concerned over the “decline of the family” and the “crises of the family” (Smith, 2000) by which they mean a concern that divorce and postmodern family values are assaulting “the traditional fam- ily.” Most evangelicals view this traditional family as the Bib- lical family; thereby, remaking the family values debate into a religiously charged discussion. Another central tenet of evangelicalism is a critical en- gagement with American culture at large (Collins, 2005; Gal- lagher, 2003; Hunter, 1983, 1987; Smith, 2000; Smith et al., 1998; Sweeney, 2005). No place demonstrates this engagement more clearly than familial roles and ideologies. By maintaining a clear affirmation of male headship and female submission, evangelicals distinguish themselves from gains made by femi- nism and its elucidation of patriarchy (contra Stacey, 1990, who discusses the positive relationship between feminism and evangelicalism). An important aspect of male headship and female submission concerns the actual performance of house- hold tasks. Of course, one should not assume a one-to-one cor- respondence between gender ideology and specific household tasks based on large, quantitative samples (Denton, 2004). By analyzing how evangelicals perform their household tasks, one may develop insight into how evangelicals may have modified their patriarchal views because of evangelicals’ active engage- ment with feminism and family values in a negative sense, i.e., defining themselves against them. Secularization Theory and Its D isc ontents To begin with, Hunter (1983, 1987) has demonstrated that there has been a noticeable shift in views on Biblical inerrancy (The Bible is exclusively and exhaustively true) and concomi- tant methods of Biblical interpretation. The Bible is viewed as the true Word of God, but there are limits around the type or kind of truth contained in it. Along with a “high” view of Bib- lical inerrancy comes a literalistic hermeneutic. There has been a shift from a preference to always interpret the Bible literally to a preference to sometimes interpret the Bible figuratively. The second theological shift Hunter (1987) identifies con- cerns doctrine. Doctrinally, evangelicals have shifted their per- spectives on: 1) the devil—a personal being that directs evil forces, 2) anthropology—Adam and Eve were created by God for good, 3) cosmology—God created the earth, 4) soteriol- ogy—Christ is the only way for salvation, and 5) social jus- tice—taking less precedence than evangelism. These views on scripture and doctrine demonstrate for Hunter a shift in the belief structure for evangelicals. Specifically, these shifts are evidence that views of scripture and doctrine have become modernized or secularized. Hunter, therefore, argues for the increasing secularization of evangelicalism as it continues to interact with modern culture. Based on Berger (1967), Hunter views modernity as essentially subversive to all religious perspectives, especially Christianity.  T. V. FREDERICK ET AL. 510 That is, modernity replaces the ‘sacred canopy’ of a religious worldview with a scientific, non-religious one. One of the cen- tral emphases in evangelicalism is lending to its own demise from a secularization perspective. A core issue about evangelicalism from a secularization per- spective is the robust nature of its existence. That is, evangeli- calism is a growing, vibrant, worldwide religion that defies the expectations of secularization theory. Secularization posits that exposure to modernity erodes religious worldviews, in this case Evangelicalism. A contemporary theory used to explain evan- gelicalism’s continued existence is Subculture Identity Theory (SIT) developed by Smith and colleagues (Smith, 2000, Smith et al., 1998). From a SIT perspective, three fundamental as- sumptions (Smith et al.) are: 1) everyone has a moral world- view, 2) worldviews are supported and maintained in actual social groups, and 3) religion naturally allows everyone to live by a worldview. These worldviews create symbolically defined boundaries, and they provide a way for determining who is and is not a member of the group, specifically who is and is not evangelical. For evangelicals, boundaries allow them to be embattled yet thriving (Smith et al., p. 121): The evangelical tradition’s entire history, theology, and self-identity presup- poses and reflects strong cultural boundaries with non- evan- gelicals; a zealous burden to convert and transform the world outside of itself; and a keen perception external threats and crises seen as menacing what it views to be true, good, and valuable. Purpose of the Present Study Focusing on evangelicalism’s strong social dimensions natu- rally leads one away from theological discourse to social issues. One primary component of evangelicalism is the nature and role of the family in Christian life (Gallagher, 2003; Gallagher & Smith, 1999; Lee, 1998). Therefore, this study utilizes Sub- cultural Identity Theory to understand changes in gender ide- ology over the course of two samples of Christianity Today (CT) readers, one in 1990 and one in 2001 and its role in actual family practices for evangelicals. CT markets itself to evan- gelicals of all denominational affiliations (CT website). We would argue that in addition to things like church attendance and holding to the infallibility of Scripture, subscribing to an evangelical periodical such as Christianity Today indicates a deeper level of participation and adherence to the evangelical worldview much like self-identification as a way of identifying Evangelicals (Smith et al., 1998). Several hypotheses may be developed based on SIT. First, gender ideology is only minimally related to evangelical family practice. Gender ideology functions in evangelical circles as an identity marker, therefore, its purpose is to define and different- tiate insiders from outsiders. Household and parenting labors may have as their sources more pragmatic and task specific negotiations among relational partners as opposed to aspects of gendered identity or ideology. As a result of this sociological function, gender ideology may only be a minimally significant source for the domestic division of labor. Second, education does not subvert or “secularize” evangeli- cal gender ideology or its role in defining household and par- enting tasks. From a SIT perspective, education may provide a proximal measure of evangelical’s engagement with the culture, i.e., participation in social institutions. However, this participa tion in social institutions may actually strengthen, not weaken, the veracity of conservative evangelical gender ideology and the sexual division of household labors. Finally, more pragmatic aspects of family life may be a more specific source for the domestic division of household and par- enting labors for evangelicals. SIT would expect the actual negotiation of domestic tasks to be based on factors other than gender ideology. One would expect time demands placed by children, participation in the local congregation and education to be a more significant source for the division of household and parenting labors than gender ideology. Methods This study is based on secondary analysis of responses to gender ideology questions given by a randomly selected sample of Christianity Today readers in 1990 (N = 739) and 2001 (N = 750). A secondary analysis is research conducted on a data set provided from another source. In the present study, Christianity Today surveyed its readership two different times. Each sample was obtained by randomly selecting on an “n th” name based 1250 names from a list of all CT subscribers. One week before the mailing of the questionnaire, and three weeks following, postcards were mailed to encourage participation. The response rate was 59% and 60% for the 1990 and 2001 samples respec- tively. The unique advantages of this study is that it provides an understanding of evangelical gender ideology and domestic relationships based on a large sample of self-identified evan- gelicals from a major evangelical monthly periodical. Participants Women comprised most of the respondents of the 1990 co- hort (51.6%) compared with men (48.1%) while almost half of the 2001 respondents were women (43%) with a little over half being men (53%). The average church size for respondents was 201 - 500 people for the 1990 cohort. Nearly one-third of the 2001 respondents attend a church with a size between 201 - 500 members. For the 1990 cohort, 71.18% of women reported being a member of the laity, while 59.3% of men reported be- ing a member of the laity. 95% of women and 71% of men serve in their local churches as members of the laity in the 2001 cohort: due to the large discrepancy between the 1990 and 2001 cohorts for this variable, clergy status will be used as a control variable. Wives in the 1990 cohort tend to be either unem- ployed temporarily (14.5%) or not employed (25.9%). Only. 2% of 1990 wives are employed full time, and .4% of wives are employed part time; compared to 51% of all wives in 2001 cohort being employed: full time (34%) or part time (17%). 49% of 2001 wives are unemployed. 50.1% of husbands in the 1990 cohort are employed full time. Less than 20% of husbands in the 1990 cohort are not employed. 62% of 2001 husbands are employed full time. The average age of 1990 respondents was 41 - 50 years. The average age of 2001 respondents is 51 - 60 years. 34.2% of 1990 men have a seminary or other higher education, and 16.7% of them have a college degree. 18.9% of 1990 men have no college degree. For 1990 women, 37.9% have no college education, while 25.1% have a college educa- tion. 11.6% of 1990 women have seminary or other higher education. 58.3% of 2001 husbands have a seminary or other higher education, while 28.4% of 2001 wives have seminary or  T. V. FREDERICK ET AL. 511 college education. 28.9% of 2001 husbands and 40% of 2001 wives have a college education, and only 12.8% of 2001 hus- bands and 31.6% of 2001 wives have no college. The discrep- ancies for education and women’s employment should have a predictable impact on gender ideology based on secularization theory (see below). The average 1990 cohort family income reported wasin the rage $40,000 - $49,000, and the 2001 cohort reported being more wealthy (range $60,000 - $74,999). The demographics for the two samples were in general quite similar, except in regards to income, clergy status, and gender. The higher average income for the 2001 sample is to be ex- pected as a reflection of the higher income for persons in the United States in general in 2001 than in 1990. However, since a greater percentage of the 2001 subjects were male (53% to 48% in 1990) and laity rather than clergy (73% in 2001 to 60% in 1990), data analysis will control for gender and clergy/laity status. Measures Gender Ide olo gy Scales: Ge n de r R o le A tt itudes Regarding Church, Theology, and Work Gender role attitude items were submitted to a Principal Components Factor Analysis (PCA) to explore their construct validity for the proposed gender ideology scales. In addition to Principal Components Factor Analysis, varimax rotation was utilized so that each factor is clearly separated and differenti- ated from the others (Kim & Mueller, 1978). All data analysis utilized the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) ver- sion 15.0. The Gender Ideology Scale—Patriarchal Theology (GISPT) consists of the following four items: 1) God made men and women to be equal in personhood and value, but different in roles; 2) Both Adam and Eve were created in God’s image, equal before God as persons and distinct in their manhood and womanhood, 3) The Bible affirms the principle of male head- ship in the family; and (21) Adam’s headship in marriage was established by God before the Fall, and was not a result of sin. The Theology of Gender scale demonstrates adequate a reli- ability (α = 0.72). The Gender Ideology Scale—Women’s Role in the Church (GISWC) scale consists of the following four items: 1) only men should be ordained, 2) women may teach adult men and women in the church, 3) the position of deacon in the church should be held only by men, and 4) women should be silent in the church and not speak. The Women’s Role in the Church scale demonstrates adequate a reliability (α = 0.78). GIS-WC total score will be created by averaging responses to the 4 GIS-WC items. The Gender Ideology Scale—Women’s Involvement in Work (GISWW) scale consists of the following four items: 1) Promotion of women of child-bearing age should be limited because they may get pregnant, 2) Employers should provide women with maternity leave of at least three months with guarantees of the same or equal job upon return, 3) Women should receive equal pay for work that is equal to that of men, and 4) Working women with young children are less effective as employees. The Women’s Involvement in Work scale dem- onstrates an adequate a reliability (α = 0.81). Scaling for the gender ideology scales used a 1 - 5 point Likert-type scale. Participants were asked to respond to each question by checking either strongly agree (5), agree (4), unde- cided (3), disagree (2), or strongly disagree (1). As the main measure is a social survey, the threat of test length on the con- sistency of findings is limited. As respondents are asked a vari- ety of questions regarding both their beliefs about gender as well as their gender practices, consistency is measured statistic- cally using internal consistency measures and scaling is based on factor analysis. Domestic Task Scale and the Parenting Task Scale: The Traditional Division of Domestic Labors Because the central concerns of this research concern the adoption of patriarchal gender role attitudes and the correspond- ing perceptions regarding the traditional division of household labor by CT readers, item scoring corresponds to the “tradi- tional” (see Smith & Reid, 1986); see also the “complementary approach” explicated by Piper and Grudem (1991) for a similar division of household labors) sexual division of household la- bor. That is, wives tend to do and take responsibility for daily, routine domestic tasks (Coltrane, 1997, 2000; Reid & Smith, 1986), while husbands tend to do and take responsibility for less frequently performed domestic labors. That is, each household task will be scored as to who “should” do this task. This usually means that females are responsible for daily tasks (cooking, cleaning, dish washing) while males are responsible for less frequent outdoors types of tasks (automobile mainte- nance, yard work, house repairs). Domestic task items were submitted to PCA factor analysis with varimax rotation to determine the existence of any under- lying dimensions for the household labor items. Of the 12 household task items, 10 loaded very highly on 2 factors. The first factor will be identified as the Traditionally Women’s Domestic Tasks Scale (TWDTS). The 6 items on this factor are: (1) Arranges and plans social activities, (2) Balances the check- book, (3) Cooks meals, (5) Does the housework, (8) Goes gro- cery shopping, and (12) Takes out the garbage. These six items demonstrate adequate a reliability (α = 0.74). The TWDTS will be averaged to create a total scale. The second factor identified by the PCA will be identified as Traditional Men’s Domestic Tasks Scale (TMDTS). The 4 items on this factor are: (7) Does the yard work, (9) Leads/ initiates devotions/Bible study, (10) Looks after and maintains the automobile(s), and (11) Makes major family/home deci- sions. These four items demonstrate adequate a reliability (α = 0.66). These four items will be averaged to create the TMDTS total scale. The items used to construct the parenting task scale (PTS) are: (1) Administers discipline, (2) Cares for the children (dresses, feeds, bathes, etc.), (3) Changes diapers, (4) Coordinates chil- dren’s schedule (music lessons, sports, visiting friends, etc.), (5) Gives attention to their spiritual growth and development, (6) Listens to their problems when they are hurting, (7) Manages the children’s needs (buys clothes, handles doctor’s visits, etc.), and (8) Plays with the children. Item scoring will reflect a tradi- tional division of parenting tasks so that items (1) and (5) will be scored: 3 = mainly husband, 2 = shared equally, and 1 = mainly wife. Items (2), (3), (4), (6), and (7) will be scored: 3 = mainly wife, 2 = shared equally, and 1 = mainly husband. The first factor will be identified as the Traditionally  T. V. FREDERICK ET AL. 512 Women’s Parenting Tasks Scale (TWPTS). The 5 items on this factor are: (1) Administers discipline, (2) Cares for the children (dresses, feeds, bathes, etc.), (3) Changes diapers, (4) Coordi- nates children’s schedule (music lessons, sports, visiting friends, etc.), and (7) Manages the children’s needs (buys clothes, han- dles doctor’s visits, etc.). These five items demonstrate ade- quate a reliability (α = 0.76). The TWPTS will be averaged to create a total scale. The second factor identified by the PCA will be identified as Traditionally Men’s Parenting Tasks Scale (TMPTS). The 3 items on this factor are: (5) Gives attention to their spiritual growth and development, (6) Listens to their problems when they are hurting, and (8) Plays with the children. These three items demonstrate adequate a reliability (α = 0.66). These three items will be averaged to create the TMPTS total scale. Results Hierarchical regression analysis is used to model gender ide- ology’s predictive ability on the traditional division of house- hold and parenting labor. In addition to gender ideology, demo- graphic variables—age, income, and years married—are also included to ascertain the single best predictor for the traditional division of labor. Sampling year and gender were also included in the regression analysis. 1990 (Cohort year) is coded so that larger numbers indicate 2001 and smaller numbers indicate 1990. Female (Gender) is coded so that larger numbers indicate males while smaller numbers indicate females. To index the time demands placed by children, the total score for each item “Number in Household for each age group (5 possible an- swers)” except for ages 18 years and over will be summed to create a time demand by children score (see Coltrane, 1997, Cowan & Cowan, 1992; and Reid & Smith, 1986 for the de- manding role children place on families, even egalitarian ones). Table 1 demonstrates the inter-relationships between gender ideology and education, church involvement, time demands, years married and income. It is important to note, that, there are Table 1. Correlations between Gender Ideology, Education, Time Demands from Children, Church Involvement, Years Married and Income. a Variables 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1 - 0.32** 0.50** –0.04 0.04 –0.41** –0.03–0.04 2 - 0.09* –006 0.03 –0.19** –0.02 –0.02 3 - 0.01 –0.09* –0.16** 0.080.03 4 - –0.06 0.08 –0.05 –0.04 5 - –0.09 –0.07 0.25* 6 - –0.07–0.05 7 - 0.04 8 - a. Note: * = p ≤ 0.05. ** = p ≤ 0.01. N = 489. b 1= GIS - WC, 2 = GIS - PT, 3 = GIS-WW, 4 = Education, 5 = Time Demands, 6 = Church Involvement, 7 = Years Married, and 8 = Income. two sets of significant correlations. First, all gender ideology scales are significantly correlated. Second, church involvement accounts for 17% of the variance associated with GIS-WC, 4% of the variance associated with GIS-PT, and 3% of the variance associated with GIS-WW. As can be seen in Table 2, demographic variables account for 17% of the variance associated with traditionally defined women’s household tasks. In combining demographic variables with sampling year and gender, a total of 31% of variance asso- ciated with traditionally defined women’s household tasks is accounted for. The predominant amount of variance associated with traditionally defined women’s tasks is accounted for by demographic variables and sampling year and gender. Educa- tion, time demands from children, and church involvement account for no additional unique variance associated with tradi- tionally defined women’s household tasks when combined with demographic variables and sample year and gender. Gender ideology combined with all other variables accounts for 32% of the variance associated with traditionally defined women’s household tasks indicating that gender ideology accounts for a significant amount of unique variance compared to education, time demands from children, and church involvement. However, gender ideology only contributes 1% of the unique variance accounted for in the regression models. Table 2. Hierarchical Regression Analyses for Variables Predicting Tradition- ally Defined Women’s Household Tasks. Regression Modela VariablesModel 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Block 1 B SE BB SE B B SE B B SE B Age –0.010.01–0.030.01 –0.03 0.01 –0.03 0.01 Income –0.010.000.000.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Years Married 0.010.000.010.00 0.01 0.00 0.06 0.00 Block 2 Sampling Year - - –0.310.02 –0.32 0.02 –0.26 0.02 Gender - - 0.150.02 0.15 0.02 0.16 0.02 Block 3 Education- - - - –0.001 0.01 -0.0010.01 Time Demands - - - - 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 Church involvement - - - - 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Block 4 GISWC- - - - - - –0.0030.01 GISPT - - - - - - 0.030.01 GISWW- - - - - - –0.050.01 Constant2.00 2.16 2.12 2.06 Adjusted R20.17 0.31 0.31 0.32 F change145.76** 207.80** 2.42 9.45** a. * = p ≤ 0.05; ** = p ≤ 0.001.  T. V. FREDERICK ET AL. 513 Demographic variables account for 22% of the variance as- sociated with traditionally defined men’s household tasks (see Table 3). A total of 32% of the variance associated with tradi- tionally defined men’s household tasks is accounted for when combining demographic variables with sampling year and gen- der. The predominant amount of variance associated with tradi- tionally defined men’s tasks is accounted for by demographic variables, sampling year and gender. Predicting the Traditional Division of Parenting Labor None of the gender ideology scales are significant predictors of traditionally defined women’s parenting tasks (see Table 4). Demographic variables account for 5% of the amount of vari- ance associated with traditionally defined women’s parenting tasks. An additional 32% of the variance associated with tradi- tionally defined women’s parenting tasks is accounted for by sampling year and gender. Education, time demands, and church involvement account for only an additional 2% of the variance associated with traditionally defined women’s parent- ing tasks. Gender ideology scales account for no additional Table 3. Hierarchical Regression Analyses for Variables Predicting Tradition- ally Defined Men’s Household Tasks. Regression Modelaa Variables Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Block 1 B SE B B SE B B SE B B SE B Age 0.07 0.01 0.04 0.010.04 0.01 0.04 0.01 Income 0.02 0.00 0.00 0.000.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Years Married 0.08 0.00 –0.06 0.00–0.06 0.00 –0.060.00 Block 2 Sampling Year - - 0.23 0.010.24 0.01 0.21 0.02 Gender - - –0.04 0.02–0.02 0.01 –0.040.02 Block 3 Education - - - - –0.02 0.01 –0.020.01 Time Demands - - - - –0.01 0.01 –0.010.01 Church involvement - - - - –0.00 0.00 –0.0020.00 Block 4 GISWC - - - - - - –0.020.01 GISPT - - - - - - –0.030.01 GISWW - - - - - - 0.04 0.01 Constant 1.78 1.57 1.63 1.76 Adjusted R2 0.22 0.32 0.32 0.33 F change 196.77** 150.70** 3.54* 8.41** a* = p ≤ 0.05; ** = p ≤ 0.001. Table 4. Hierarchical Regression Analyses for Variables Predicting Tradition- ally Defined Women’s Parenting Tasks. Regression Modela VariablesModel 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Block 1 B SE BB SE B B SE B B SE B Age –0.010.01–0.02 0.01 –0.02 0.01 –0.020.01 Income 0.000.00–0.002 0.00 –0.003 0.00 –0.003 0.00 Years Married 0.050.010.04 0.00 0.04 0.00 0.04 0.00 Block 2 Sampling Year - - –0.05 0.02 –0.06 0.02 –0.05 0.02 Gender - - 0.58 0.02 0.56 0.02 0.560.02 Block 3 Education- - - - 0.07 0.01 0.070.01 Time Demands - - - - –0.003 0.01 –0.010.01 Church involvement - - - - –0.002 0.00 –0.0020.01 Block 4 GISWC - - - - - - –0.010.01 GISPT - - - - - - 0.010.00 GISWW - - - - - - –0.0010.01 Constant 1.67 0.99 0.91 0.91 Adjusted R20.05 0.37 0.39 0.39 F change33.59** 544.14** 17.66* 0.94 a. p ≤ 0.05; ** = p ≤ 0.001. variance associated with traditionally defined women’s parent- ing tasks. Demographic variables account for 14% of the variance as- sociated with traditionally defined women’s household tasks. In combining demographic variables with sampling year and gen- der, a total of 21% of variance associated with traditionally defined women’s household tasks is accounted for. The pre- dominant amount of variance associated with traditionally de- fined women’s tasks is accounted for by demographic variables and sampling year and gender (see Table 5). Education, time demands from children, and church in- volvement account for .3% additional unique variance associ- ated with traditionally defined women’s household tasks when combined with demographic variables and sample year and gender. Gender ideology combined with all other variables accounts for 22% of the variance associated with traditionally defined men’s parenting tasks. However, gender ideology only contributes 1% of the unique variance accounted for in the re- gression models. To summarize the regression analyses, the evidence indicates that the gender ideology scales account for 1% of the unique  T. V. FREDERICK ET AL. 514 Table 5. Hierarchical Regression Analyses for Variables Predicting Tradition- ally Defined Men’s Parenting Tasks. a Regression Models Variables Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Block 1 B SE B B SE B B SE B B SE B Age 0.04 0.01 0.03 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.02 0.01 Income 0.00 0.00 –0.01 0.00 –0.01 0.00 –0.01 0.00 Years Married –0.08 0.00 –0.06 0.00 –0.06 0.00 –0.06 0.00 Block 2 Sampling Year - - 0.19 0.02 0.20 0.02 0.12 0.02 Gender - - –0.18 0.02 –0.18 0.02 –0.19 0.02 Block 3 Education - - - - 0.02 0.01 0.030.01 Time Demands - - - - –0.02 0.01 –0.010.01 Church involvement - - - - 0.00 0.00 0.010.00 Block 4 GISWC - - - - - - 0.000.01 GISPT - - - - - - –0.010.01 GISWW - - - - - - 0.070.01 Constant 2.26 2.28 2.24 2.17 Adjusted R2 0.14 0.206 0.209 0.22 F change 111.79** 91.92** 3.95* 12.48** a. p ≤ 0.05; ** = p ≤ 0.001. variance associated with traditionally defined women’s and men’s household tasks. Gender ideology also accounts for 1% of the unique variance associated with traditionally defined men’s parenting tasks. Gender ideology does not contribute any unique variance to traditionally defined women’s parenting tasks. Demographic variables account for the predominant amount of variance associated with domestic labor. Discussion One of the questions this study attempted to answer centered on the relationship between gender ideology and gendered divi- sion of household and parenting tasks. Our strategy was to con- sider the ability of each of the 3 aspects of gender ideology to predict each of the 4 types of family tasks, relative to other potential explanatory variables. Subcultural Identity theory provides an excellent description of how a social group develops its identity as compared with a larger cultural identity. In the present study, SIT has provided specific hypotheses as to the role gender and religion play in aiding Evangelical Christians to develop and maintain a distinct identity from the larger culture in the United States. Gender Ideology as Related to Evangelical Family Practice From the above findings it can be concluded that gender ide- ology is very minimally related to patterns of gender divisions of household and parenting labor. It should be noted, however, that there is a definite high, positive correlation between church involvement and gender ideology as measured by the proposed scales. This may indicate that church involvement and gender ideology may in fact be measuring a similar construct. There- fore, it may be concluded that gender ideology may play a lar- ger role in explaining the variance associated with household and parenting tasks as measured by the CT survey. Combining the total amount of variance of all regression models accounts for only 32% of the variance associated with traditionally de- fined women’s household tasks; this is an important finding because of the strong conventional wisdom within evangelical- ism that behavior follows from attitudes (Balswick, 1987). In- deed, the major division between more conservative and more liberal Christians during the civil rights movement was that the former believes that the heart must be changed before dis- criminatory behavior will change, while liberals put their ener- gies into attempts to change discriminatory practices (Balswick, 1987) Secularization as Potential Explanation for Gender Ideology: Education and the Prediction of Household Labor Based on secularization theory, one would expect level of education to be inversely related to traditional gender ideology and familism (Berger, 1967; Coltrane, 1997; Hunter, 1983, 1987). Since the 2001 cohort of CT readers had higher levels of education, especially differences among 1990 and 2001 women, than the 1990 cohort, it would be expected that this alone might result in gender ideology for the 2001 cohort being less tradi- tional than the 1990 cohort. The fact that this is not the case seems to rule out the usefulness of secularization theory in in- terpreting our results. Increases in evangelical women’s educa- tion and employment are related to decreased tolerance for women’s participation in the church and the workplace. It is noteworthy that of the 3 arenas of gender ideology identified in this study—gender and the church, gender and work outside of the home, and gender and theology—the latter is the least re- lated to gendered divisions of household and parenting tasks. This is an irony, since, due to their high view of Scriptural au- thority, evangelicals seek to support and justify their behavior on the basis of the teachings of scripture. Yet, when it comes to gender participation in housework and parenting, ecclesiastical and work world ideologies are better predictors than theological ideology. But even more of an irony is that certain structural variables—such as years married and education—appear to be better predictors of traditional division of household and par- enting tasks than is gender ideology. These findings indicate that gender ideology defined in terms of attitudinal statements is only minimally related to the actual practices of evangelicals. Pragmatic Aspects of Family Life as a Source for the Domestic Division of Househol d an d P are nti ng Labors These findings are consistent with those reported by Galla- gher (2003) regarding the relationship between views of Scrip  T. V. FREDERICK ET AL. 515 ture and holding to male headship or mutual submission in marriage. Using the Religious Identity and Influence Survey (Smith et al., 1998), Gallagher (2003) operationalized view of Scripture as an aspect of gender ideology. The evidence sug- gests that both gender essentialist (strong male headship lan- guage) and biblical feminists (mutual submission language) equally share very high views of Scripture and its authority for individual believers as a rule in faith and practice (Gallagher). Further, evangelicals do not tend to solely appeal to hermeneu- tics in arguing either for or against their gender ideology and concomitant domestic labors (Bartkowski, 1996, 2001; Galla- gher, 2003; Gallagher & Smith, 1999). In daily life of actually performing domestic labors, evangelicals in Gallagher’s study rely upon other ways to negotiate who does what. Gallagher confirms for this study that theologically informed gender ide- ology is not the most significant source for the domestic divi- sion of traditional labors for evangelicals. Gallagher (2003) suggests three options for how evangelicals distribute household and parenting labor. First, the traditionalist approach is to maintain the male breadwinner and female do- mestic division of household and parenting labor where females take primary responsibility for all domestic tasks and males “help” with the housework. This could also characterize the complementary approach (Piper, 1991). Second, domestic tasks are more pragmatically divided based on male headship which emphasizes servant leadership thereby encouraging males to participate in all household and parenting tasks. Finally, egali- tarians also encourage the equal division of domestic labors; however, they do not adopt male headship language in the dis- cussion of negotiating domestic tasks. However, it does seem that CT readers are following Gallagher’s second approach in apportioning domestic labor because all relevant variables only account for 32% of the variance associated with household and parenting tasks at best. Due to the reification of patriarchal gender ideologies (Frederick & Balswick, 2006) and gender ideology’s minimal ability to significantly predict the tradi- tional division of domestic labor, it would seem that CT readers, along with most other evangelicals, utilize a more pragmatic approach to negotiating the domestic division of labor along- side the continued affirmation of the traditional family model. The evidence from CT readers does support gender ideology as being a significant source in how evangelicals perceive the traditional division of household and parenting tasks. The evi- dence, however, also suggests that education, time demands, and church involvement may play a more significant role in the distribution of domestic labor than does gender ideology. In considering the efficacy of the proposed gender ideology scales for predicting the traditional division of household and parent- ing labors, one should consider the unique variance that GIS variables contribute to the total amount of variance accounted for in the regression models. The GIS scales contribute 1% of unique variance for traditionally defined women’s and men’s household tasks and traditionally defined men’s parenting tasks. The 1% unique variance contributed by the GIS indicates that it is of slight importance as a predictor of household and parent- ing tasks. It could be the case that education, time demands, and church involvement may measure similar constructs to the GIS. The evidence also indicates that gender ideology is highly re- lated to church involvement. Taken together, gender ideology, education, church involvement, time demands account for a significant amount of variance associated with domestic labors. Conclusions and Limitations There are three major conclusions based upon the findings from this study. To begin with, there is evidence for the multi- dimensional nature of gender ideology. There is mixed evi- dence in general regarding the efficacy of gender ideology pre- dicting the sexual division of domestic labor in contrast to rela- tive resources and time demands (Bianchi et al., 2000; Coltrane, 1997, 2000; Kroska, 2000, 2002; Pleck, 1981). Gender ideol- ogy, it is assumed, assesses the extent to which an individual agrees or disagrees with statements regarding male and female roles which indicates one’s gender ideology. At one time, gen- der ideologies were assumed to constitute one’s gender identity; however, gender identity measures do not necessarily measure one’s maleness or femaleness (Pleck, 1981). Gender ideology measures, however, do “tend to capture the extent to which people express agreement or disagreement with conventional gender stereotypes” (Coltrane, 1996/1997, p.158). There is actually little to no evidence for gender ideology scales and indices of actually measuring an aspect of identity which may explain the lack of relatedness between gender ideology and identity to actual gender behavior. For evangelicals, gender ideology may consist of attitudes and preferences regarding the nature of manhood and womanhood as well as church and workforce participation. In addition, the behaviors associated with one’s gender role forms an experiential dimension to gen- der ideology that must be taken into account. Evangelical’s gender ideology necessarily extends to both household and parenting tasks. In operationalizing gender ideology, one would do well to have a multidimensional construct taking into ac- count as many facets of gender ideology as possible. Second, the major findings from this study may indicate the adoption of the family as a central aspect of evangelical gender ideology—especially as an identity boundary maintenance strategy (SIT). Gender ideology and behavior within the evan- gelical subculture is not uniform; however, and there is evi- dence that differences between the 1990 and 2001 cohorts are not uniform either. It is significant, for example, that the 1990 sample of women are most traditional in defining men’s household tasks, while in the 2001 sample it is the men them- selves who hold to the most traditional view on household tasks. This may indicate that evangelicals affirm a traditional family and gender ideology while they perceive domestic labor along different lines (Pragmatic Egalitarianism—Gallagher). Finally, this study demonstrates the effectiveness of SIT for understanding Christianity Today readers’ gender ideology and domestic division of labor. By 1) having a multidimensional construct for gender ideology, 2) accounting for education and the potential for testing a secularization theory hypothesis against a SIT one, and 3) the result in line with theoretical pre- dictions that gender ideology is minimally related to the actual performance of household tasks, all point to the efficacy of SIT for this sample of evangelical Christians. Evangelicals are a heterogeneous group. This study has found that at least some evangelicals adopt patriarchal language to discuss their preferred family model and its concomitant gender ideologies; however, this model is applied in individual relationships in a myriad of ways (Bartkowski, 2001). As with  T. V. FREDERICK ET AL. 516 non-evangelical, non-religious samples, relative resources, gender ideology and time availability play a complex role in explaining the sexual division of household labor (Coltrane, 1997). There is no clear-cut single best explanation for the ways in which evangelicals negotiate the tasks that form the most intimate gendered relationship (Bartkowski, 2001). References Balswick, J. O. (1987). The psychological captivity of Evangelicalism. In W. H. Swatos, Jr. (Ed.), Religious Sociology: Interfaces and Boundaries (pp. 141-152). West Port, CT: Greenwood Press. Bartkowski, J. P. (1996). Beyond Biblical literalism and inerrancy: Conservative Protestants and the interpretation of Scripture. Sociol- ogy of Religion, 57, 259-272. doi:10.2307/3712156 Bartkowski, J. P. (2001). Remaking the Godly marriage: Gender nego- tiation in Evangelical families. Rutgers, NJ: Rutgers University Press. Bartkowski, J. P. (2004). The Promise Keepers: Servants, soldiers, and Godly men. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. Berger, P. L. (1967). The sacred canopy: Elements of a sociological theory of religion. New York, NY: Anchor Books. Bianchi, S. M., Milkie, M. A., Sayer, L. C., & Robinson, J. P. (2000). Is anyone doing the housework? Trends in the gender division of household labor. Social Forces, 79, 191-228. doi:10.2307/2675569 Christianity Today. (2004). “Christianity Today- Informing. Inspiring. Connecting. Equipping.” Accessed March 10, 2004 [http://www.christianitytoday.com/]. Clapp, R. (1993). Families at the crossroads: Beyond traditional and modern options. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press. Collins, K. J. (2005). The Evangelical moment: The promise of an American religion. Grand Rapids, MI: BakerAcademic. Coltrane, S. (1997). Family man: Fatherhood, housework, and gender equity. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Coltrane, S. (2000). Research on household labor: Modeling and meas- uring the social embeddedness of routine family work. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 1208-1233. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01208.x Cowan, C. P., & Cowan, P. A. (1992). When partners become parents: The big life change for couples. New York: Basic Books. Denton, M. (2004). Gender and marital decision making: Negotiating religious ideology and practice. Social Forces, 82, 1151-1180. doi:10.1353/sof.2004.0034 Ellison, C. G., & Bartkowski, J. P. (2002) Conservative Protestantism and the division of household labor among married couples. Journal of Family Issues, 23, 950-985. doi:10.1177/019251302237299 Frederick, T. V., & Balswick, J. O. (2006). Evangelical gender ideol- ogy: A view from Christianity Today readers. Journal of Religion and Society, 8, 1-12. Gallagher, S. K. (2003). Evangelical identity and gendered family life. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. Gallagher, S. K., & Smith, C. (1999). Symbolic traditionalism and pragmatic egalitarianism: Contemporary evangelicals, families, and gender. Gender & Society, 13, 211-233. doi:10.1177/089124399013002004 Hunter, J. D. (1983). American Evangelicalism: Conservative religion and the quandary of modernity. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers Uni- versity Press. Hunter, J. D. (1987). Evangelicalism: The coming generation. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Kim, J. O., & Mueller, C. W. (1978). Factor analysis: Statistical meth- ods and practical issues (Vol. 07014). Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. Kroska, A. (2000). Conceptualizing and measuring gender ideology as an identity. Gender & Society, 14, 368-394. doi:10.1177/089124300014003002 Kroska, A. (2002). Does gender ideology matter? Examining the rela- tionship between gender ideology and self- and partner- meanings. Social Psychology Quarterly, 65, 248-265. doi:10.2307/3090122 Lee, C. (1998). Beyond family values. Grand Rapids, MI: InterVarsity Press. Piper, J. (1991). A vision of Biblical complementarity: Manhood and womanhood defined according to the Bible. In J. Piper & W. Grudem (Eds.). Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood: A Response to Evangelical Feminism (pp. 31-59). Wheaton, IL: Crossway. Pleck, J. H. (1981). The myth of masculinity. Cambridge, MA: Massa- chusetts Institute of Technology Press. Robinson, J. R. (1985). The validity and reliability of diaries versus alternative time use measures. In F. Thomas and F. P. Sanford (Eds.), Time, Goods, and Well-Being (pp. 33-62). Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. Smith, C. (2000). Christian America? What Evangelicals really want. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. Smith, C., with Emerson, M., Gallagher, S. K., Kennedy, P., and Sik- kink, D. (1998). American Evangelicalism: Embattled and thriving. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Smith, A. D., & Reid, W. J. (1986). Role-Sharing marriage. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. Stacey, J. (1990). Brave new families: Stories of domestic upheaval in late twentieth-century America. New York, NY: BasicBooks. Sweeney, D. A. (2005). The American Evangelical story: A history of the movement. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic. Van Leeuwen, M. S., Knoppers, A., Koch, M. L., Schuurman, D. J., & Sterk, H. M. (1993). After Eden: Facing the challenge of gender reconciliation. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. Webber, R. E. (1978). Common roots: A call to Evangelical maturity. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan. Wilcox, W. B. (2004). Soft patriarchs, new men: How Christianity shapes fathers and husbands. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

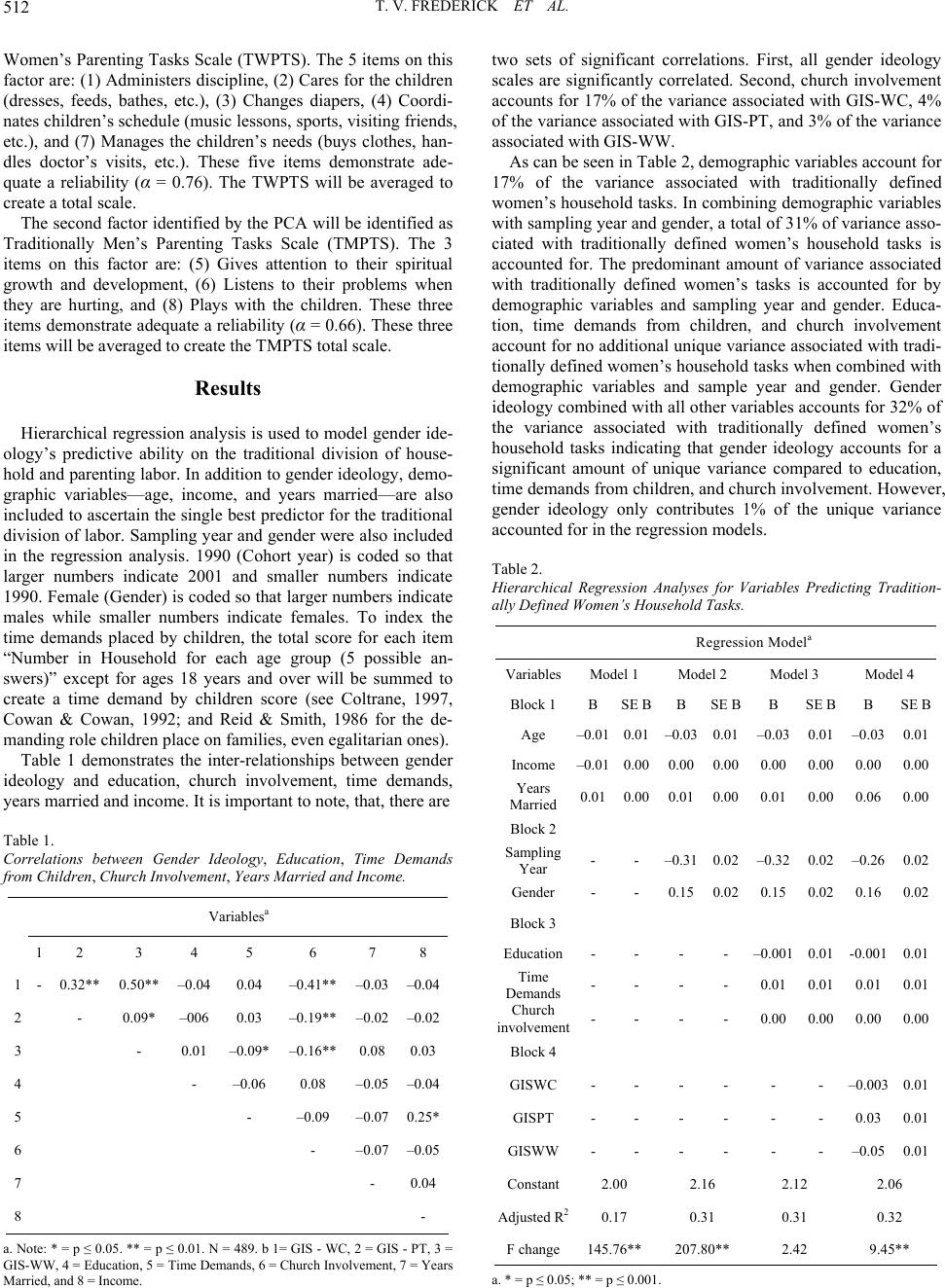

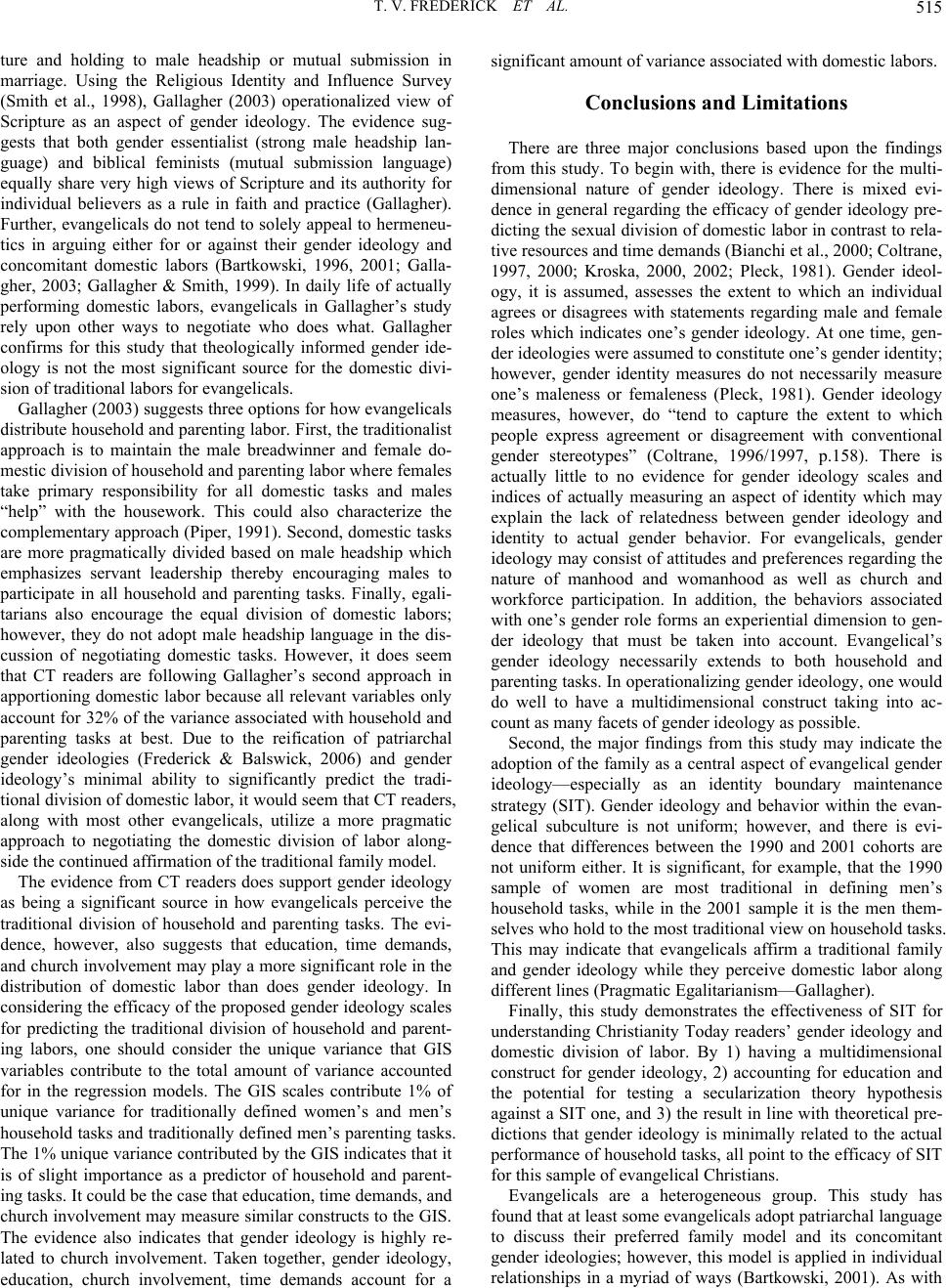

|