Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

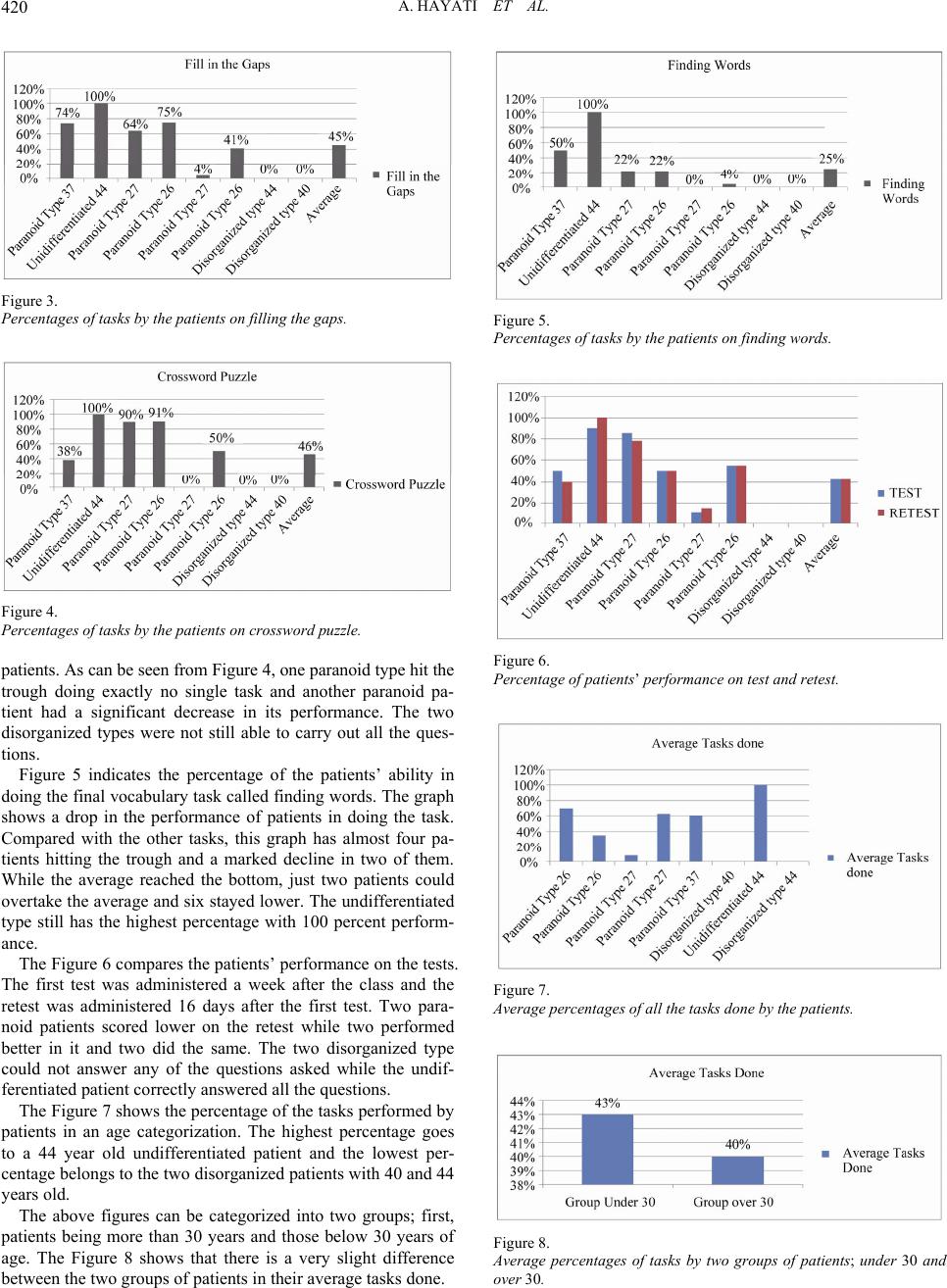

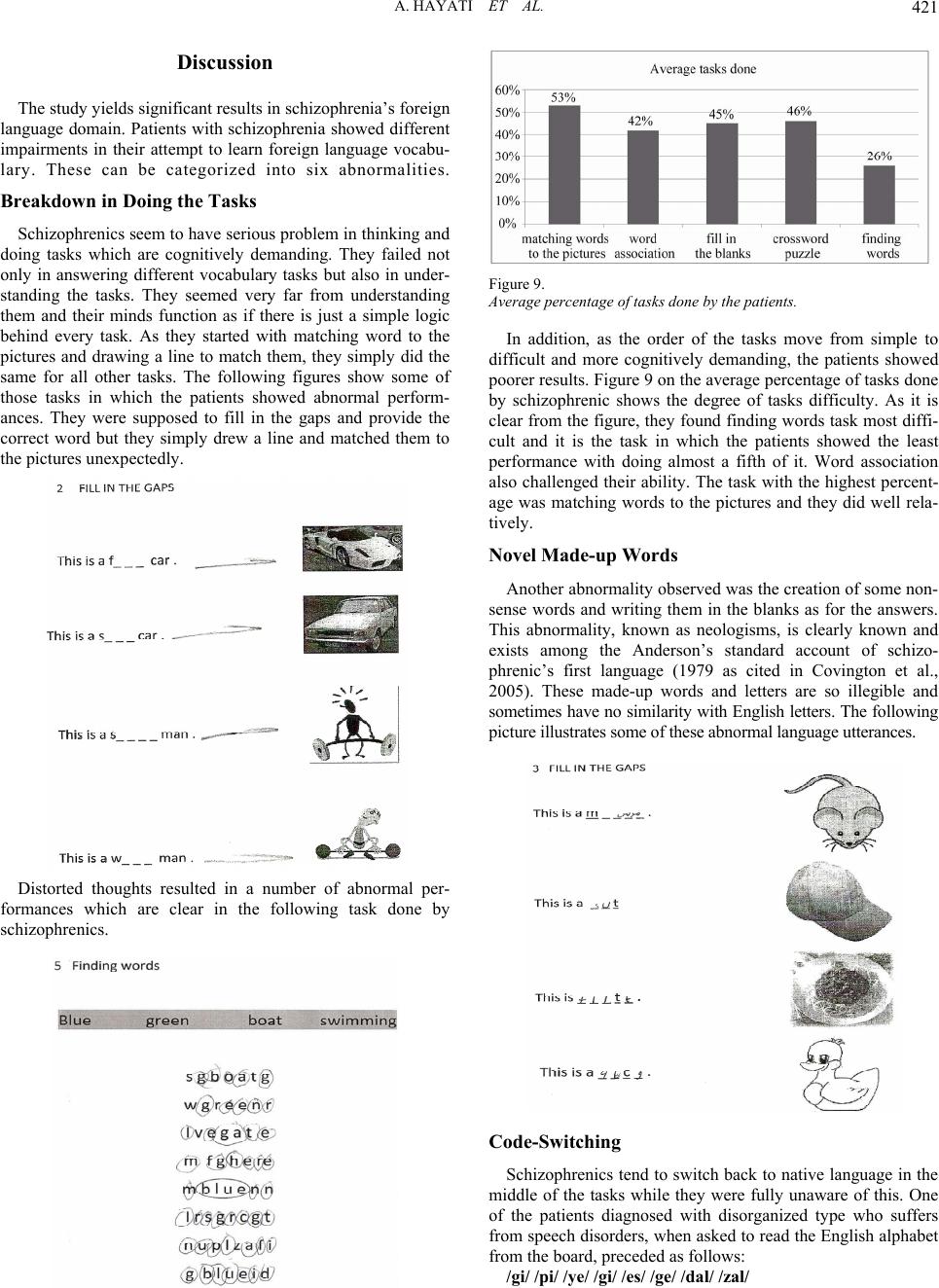

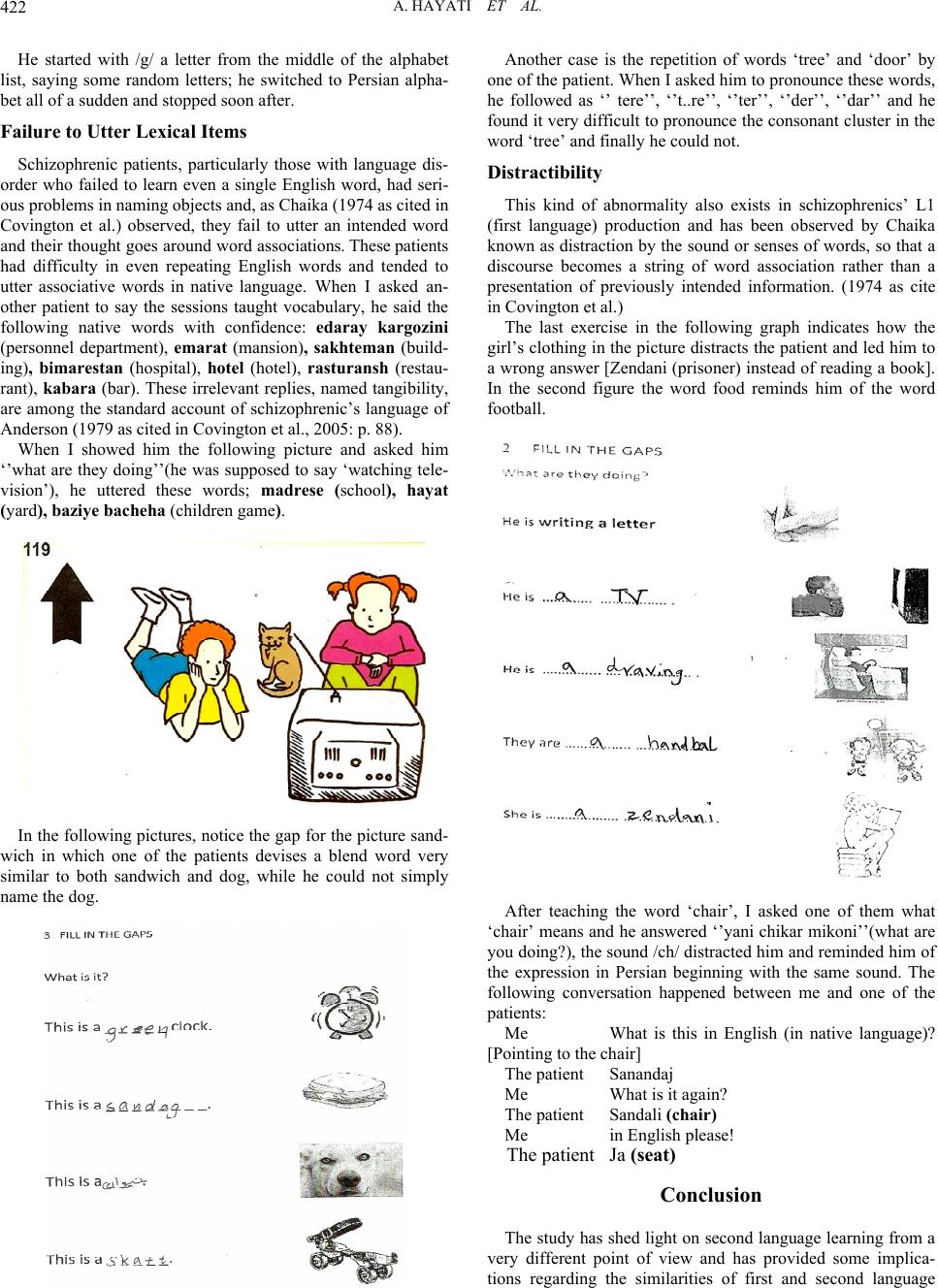

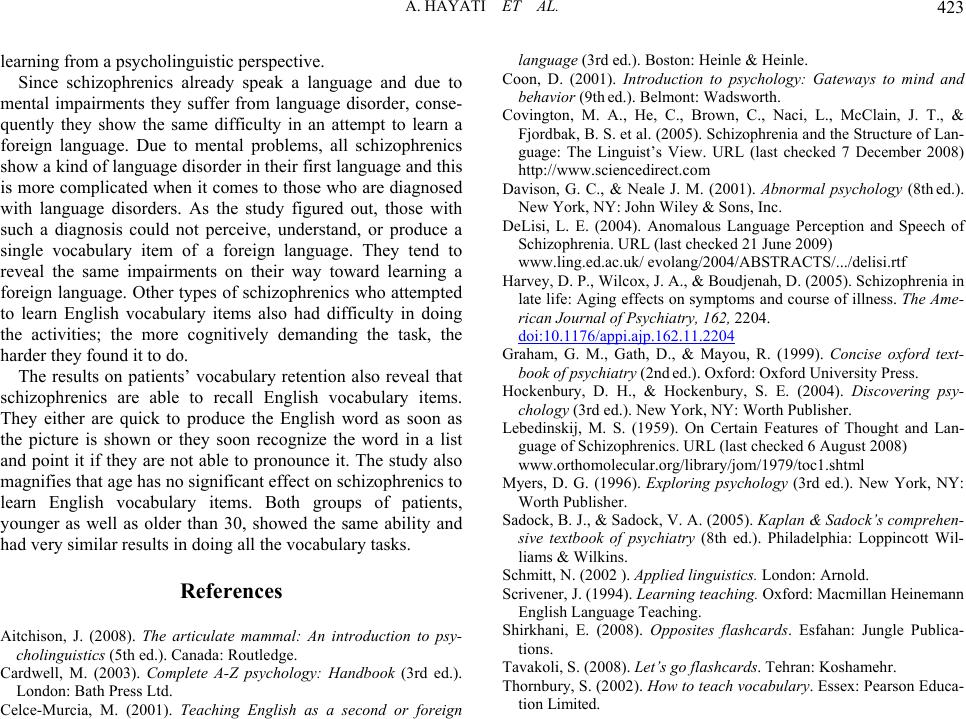

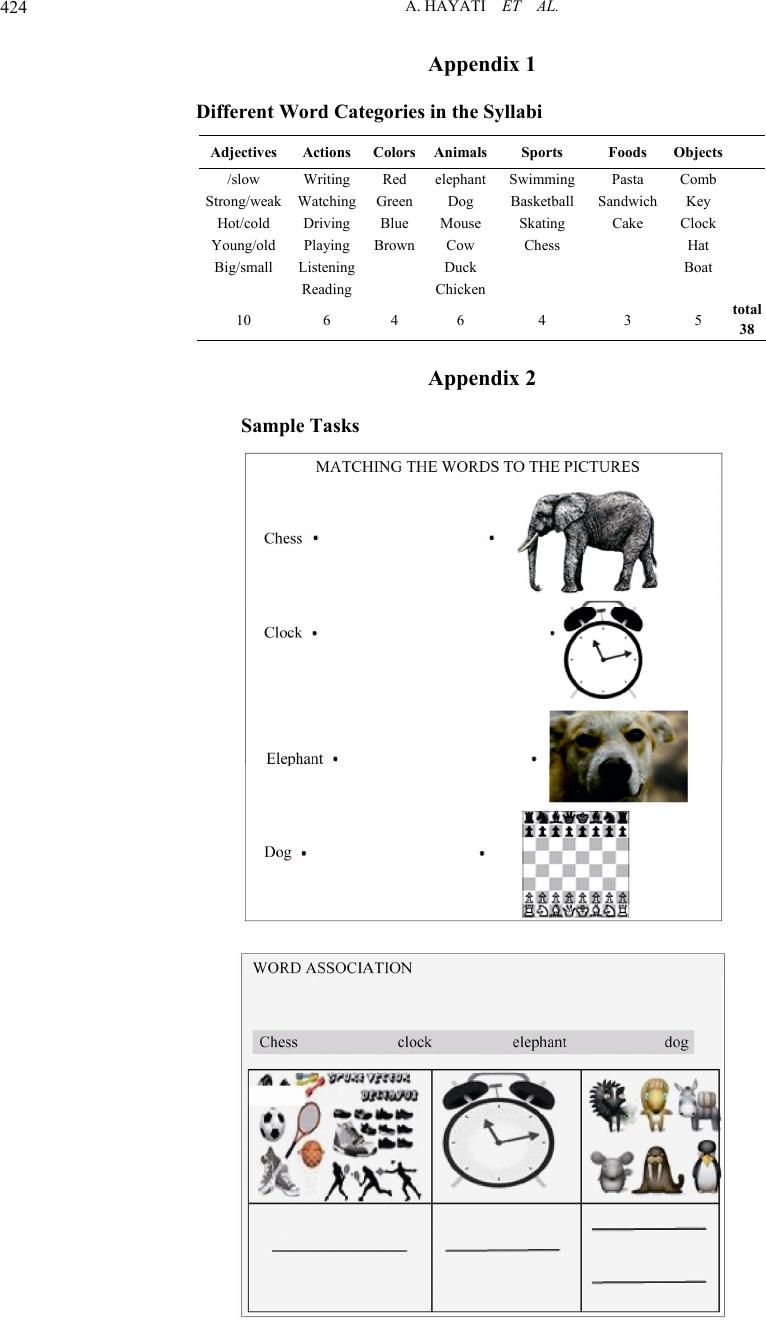

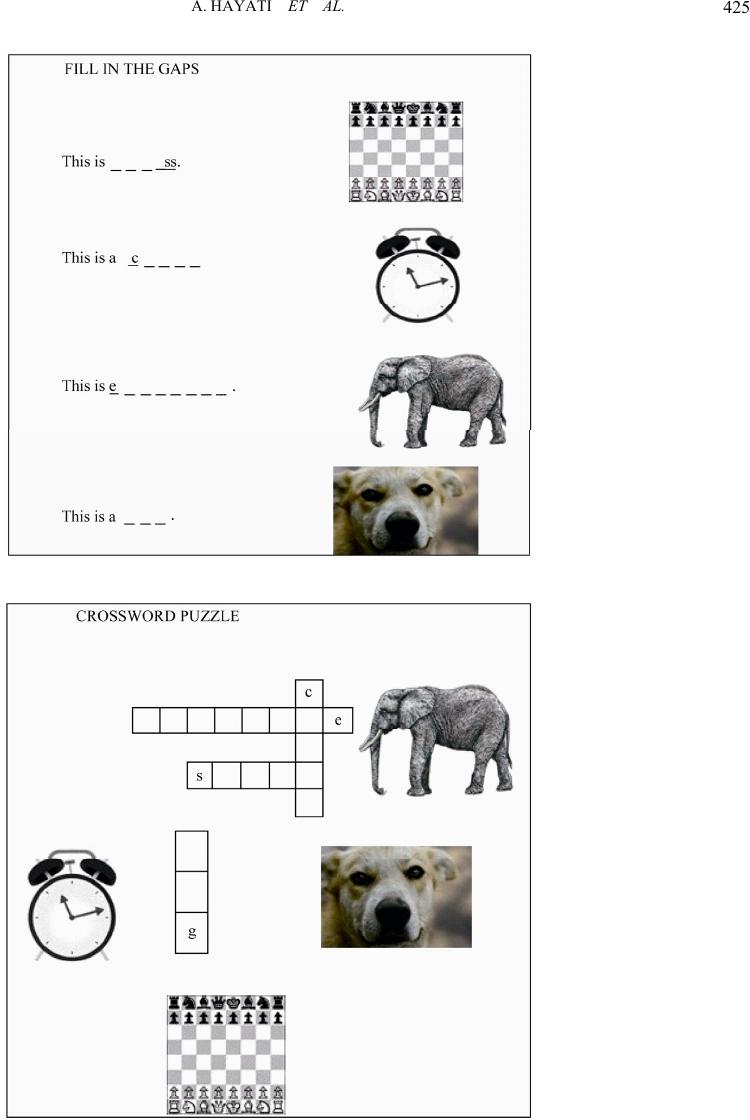

Psychology 2011. Vol.2, No.5, 416-425 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. DOI:10.4236/psych.2011.25065 On the Relationship between Mind and Language: Teaching English Vocabulary to Schizophrenics Abdolmajid Hayati1, Khaled Shahlaee2 1Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz, Ahvaz, Iran; 2University of Science and Research, Ahvaz Branch, Ahvaz, Iran. Email: majid_hayati@yahoo.com Received March 25th, 2011; revised May 12th, 2011; accepted June 23rd, 2011. Undoubtedly mind is the most complicated member of human being and respectively a small breakdown in whatever processes undergone will cause great difficulties for the beholder. One of the most serious psycho- logical impairments is known as schizophrenia which severely distorts thought and action (Hockenbury & Hockenbury, 2004). The present study is set out to investigate the capability of patients with schizophrenia in doing different vocabulary tasks on second language and retaining them for a period of time. Eight male patients diagnosed with schizophrenia of different types were selected from two mental centers to participate in the study. They were invited to attend a class for 16 sessions in 8 weeks and do vocabulary ta s ks i ncl udin g matching words to the pictures, filling the blanks, word association, crossword puzzle, and word finding. A test was administered right after the period and the retest was administered 16 days later. The study illustrated that there is no signifi- cant relationship between age and learning vocabulary items by patients suffering from schizophrenia. More, schizophrenics showed different capabilities in doing vocabulary tasks, and they also showed different impair- ments in their attempt to learn foreign language words. They also found some of the tasks demanding as they become more cognitively difficult. Keywords: Psychological Im pairment, Schizophre nia , Vocabulary Task Introduction One of the main branches of linguistics known as psycho- linguistics has long been an area attracting researchers and linguists to investigate and find any trace of language in human mind. In this respect, this study seeks to shed light on a new dimension of psycholinguistic viewpoint regarding second lan- guage learning to those who suffer from schizophrenia, which Hockenbury and Hockenbury (2004) refer to as one of the most serious psychological disorders involving severely distorted beliefs, perceptions, and thought processes (p. 525). Myers (1996) defines psychological disorders a condition in which behavior is judged atypical, disturbing, maladaptive, and unjus- tifiable (p. 415). Due to the mental impairment, schizophrenics produce a kind of language which might be senseless or irrele- vant and, to some extent, all aspects of language will be dis- turbed. Teaching a language other than their mother tongue to schizophrenics will magnify the possibilities of opening a new horizon to second language learning approaches. The acquisi- tion of first language takes place spontaneously under an in- herent ability given to human beings (Chomsky, 1972 as cited in Aitchison, 2008), while learning a second language requires awareness of the stages and processes during the course. Therefore, the aim of this study is to investigate the relati onship between mind and learning second language vocabulary items in patients suffering from schizophrenia. Review of Literature Schizophrenia Schizophrenia literally means split mind. It refers to both a multiple personality split and a split from reality that shows itself in disorganized thinking, disturbed perceptions, and inap- propriate emotions and actions (Myers, 1996). Elsewhere, Hockenbury and Hockenbury (2004) define schizophrenia as one of the most serious psychological disorders which involves severely distorted beliefs, perceptions, and thought processes (p. 525). Generally, schizophrenia is defined as a psychotic disor- der marked by delusion, hallucination, apathy, thinking abnor- malities, and a split between thought and emotion. One person in 100 will become schizophrenics, and roughly half of all the people admitted to mental hospitals are schizophrenics. Most are young adults, but schizophrenia can occur at any age (Coon, 2001: p. 575). Cardwell (2003) defines schizophrenia as a seri- ous mental disorder characterized by severe disruption in psy- chological functioning. Hockenbury and Hockenbury (2004) define four types of schizophrenia. Paranoid type shows such characteristics as well-organized delusional beliefs reflecting persecutory or grandiose ideas, f requent auditory hallucinations, usually voices, and little or no disorganized behavior, speech or flat effect. Catatonic type having characteristics like highly disturbed movements or actions, such as extreme excitement, bizarre postures or grimaces, being completely immobile, and echoing of words spoken by others or imitations of movements of others. Undifferentiated type displays characteristic symptoms of schizophrenia but not in a way that fits the pattern for paranoid, catatonic, or disorganized type. Patients with disorganized type show flat or inappropriate emotional expressions, severely dis- organized speech and behavior, and fragmented delusional ideas and hallu c i n a t io n s .  A. HAYATI ET AL. 417 Schizophrenia and the Brain The search for a brain abnormality that causes schizophrenia began as early as the syndrome was identified. In the last two decades, however, stimulated by a number of technological advances, the field has reawakened and yielded some promising evidence. Some patients with schizophrenia have been found to have observable brain pathology. Postmortem analyses of the patients with schizophrenia are one source of evidence. Such studies constantly reveal abnormalities in some areas of the brains of patients with schizophrenia, although the specific problems reported vary from study to study and there are many contradictory findings. The most consistent finding is of enlarged ventricles, which implies a loss of subcortical brain cells. Moderately consistent finding indicated structural prob- lems in subcortical temporal-limbic areas, such as hippocampus and the basal ganglia, in the prefrontal and temporal cortex (Dwork, 1997; Heckers, 1997 as cited in Davison & Neale, 2001). Even more impressive and surprising are the images obtained in Computed Tomography (CT) scan and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) studies. Researchers were quick to apply these new tools to brains of living patients with schizophrenia. Thus far these images of living brain tissue have most consistently revealed that some patients, especially males have enlarged ventricles (Nopoulos, Flaum, & Andreasen, 1997 as cited in Davison & Neale, 2001). Research also shows a reduction in cortical gray matter in both the temporal and frontal regions (Goldstein et al., 1999 as cited in Davison & Neale, 2001) and reduced volume in basal ganglia (e.g., the caudate nuleus) and limbic structures (Chua & McKenna, 1995; Gur & Pearlson, 1993; Keshavan et al., 1998; Lim et al., 1998; Velakoulis et al., 1999 as cited in Davison & Neale, 2001), suggesting deteriora- tion or atrophy of brain tissue. Further evidence concerning large ventricles comes from an MRI study of fifteen pairs of Monozygotic (MZ) twins who were discordant for schizophrenia (Suddath et al., 1990 as cited in Davison & Neale, 2001). For twelve of the fifteen pairs, the twin with schizophrenia could be identified by simple visual inspection of the scan. Because the twins were genetically iden- tical, these data also suggest that the origin of these brain ab- normalities may not be genetic. There are two distinct forms of impairment (Sadock & Sa- dock, 2005). One, deficits that arise early in development and the other is deficits that arise in the context of clinical illness. These two types of deficits are conceptually, as well as tempo- rally, distinct: developmentally based deficit limit the normal acquisition of cognitive skills, as seen on measures of intelli- gence and academic ability. This developmental comprise is relatively subtle, requiring sensitive formal testing and com- parison to well-matched control population. In contrast, ill- ness-onset-related deficits appear to present an actual decline in function: they reflect a compromise in the ability to access, to deploy efficiently, and to coordinate the cognitive skills that were successfully acquired during the developmental period. Illness-onset deficits tend to be far more severe than develop- mentally based deficits and are obvious in the context of clini- cal interaction. As far as the relationship between age and schizophrenia is concerned, an attempt has been carried out to magnify the ef- fects of aging in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. Older people with schizophrenia are an often neglected group. Since there has been no retirements and barely government support, they shuffle into poor houses, county farms, and nursing homes. Cognitive decline is often seen in schizophrenia. This is a common diagnostic problem once the person has become eld- erly. Many older people have dementia. This can be very diffi- cult to sort out in the elderly person with schizophrenia if the history is unavailable. The cohabitatio n of dement ed elders and cognitively impaired elders with psychosis is commonly seen in nursing homes. In this setting, misdiagnosis and the subsequent incorrect treatment of elderly patients causes a multitude of problems. Even before coming to old age, the elderly person with schizophrenia has had a number of treatments not shared by elderly people without chronic mental illness. Neuroleptic use is common, and Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT) and even psychosurgery occur often in the histories of elderly patients with schizophrenia. Many former treatments lead to complica- tions in the assessment of cognitive fall. As these people come into treatment settings, triage and care must be provided. (Har- vey, Wilcox, & Boudjenah, 2005). Teaching Vocabulary Almost all EFL courses apply vocabulary teaching as a step toward learning a foreign language and this is executed by us- ing a number of techniques and tasks which best facilitate this process. As Scrivener (1994) stated, activities on vocabulary should contain tasks such as matching pictures to words, matching parts of the words to other parts, matching words to other words like collocation, synonyms, opposites, using prefixes and suffixes to build new ones, classifying items into lists, using given words to complete specific task, filling in crosswords, filling in gaps in sentences, memory games (p. 83). Elsewhere, Celce-Murcia (2001: p. 288 ) proposes that, es- pecially at the beginning levels, teaching word lists through word association techniques has proven to be a successful way to learn a large number of vocabulary items in a short period of time and also helps to retain them. Celce-Murcia (2001) also suggests a number of strategies such as collocations, semantic associations, syntactic collocation types, teaching activities and idioms (pp. 292-294). To Schmitt (2002), deliberate vocabulary teaching may take a variety of forms including pre-teaching of vocabulary before a language use activity, exercises that follow a listening or reading text like matching words and definition, and creating word families using word parts or semantic mapping, self con- tained vocabulary activities, word detectives where learners report on words they have found, collocation activities, quickly dealing with words as they occur in a lesson (p. 43). Studies on Language, and Schizophrenia Much has been done to investigate schizophrenia as well as the features and properties of the schizophrenic's language (Covington, Brown, Chaika, Congzhou, Lebedinskij, Semple, & Sirmon, 2005). The study of schizophrenic language disorder by linguists began with Chaika (1974, as cited in Covington et al. 2005: p. 86), who studied a single patient who spoke nor- mally for weeks at a time, her deviant language coinciding with what her psychiatrists term psychotic episodes. The abnormali-  A. HAYATI ET AL. 418 ties that Chaika (1974, as cited in Covington et al, 2005) ob- served were: 1) Failure to utter the intended lexical item, 2) Distraction by the sounds or senses of words, so that a dis- course becomes a string of word associations rather than a presentation of previously intended information, 3) Breakdown of syntax and/or discourse, 4) Lack of awareness that the utter- ances are abnormal. Of these, number two is the most charac- teristic of schizophrenia; one and three resemble ordinary speech errors, and number four resembles some forms of apha- sia. The bizarre language of schizophrenics is nowadays gener- ally believed to be a meaningless breakdown product of a neurobiological disorder. As Graham, Gath, and Mayou (1999) point out, in the early stages of schizophrenia, speech is vague and incomprehensive and later on we see more formal disorders. More, some have problems in thinking of concretes while oth- ers are involved in semi-scientific or codified beliefs. In addi- tion, there is no connection in their belief (loosing association). Also, in some cases, the connection in their thought is illogical and diverts from one subject to another, and in its most severe case, loosing of association leads to complete unorganized speech (word salad), and there might be thought impairments such as hard speech, poverty of thought, and thought blocking (p. 97). Lebedinskij (1959) argues that the interrelationships between ideation and language are, to a large extent, distinc- tively structured in schizophrenia. Even those schizophrenics who are apparently not suffering from speech disturbances exhibit a series of distinctive ways of expressing themselves with different speech production and vocabulary, all of which are connected with disturbances in thought. Structural imaging studies taken together show that brain cortical regions specifi- cally known to be responsible for components of language are reduced in size and reduced in the normal left greater than right asymmetries (i.e. prefrontal cortex, superior temporal gyrus, planumtemorale). It is proposed that the underlying cerebral basis for schizophrenia comes from anomalies in the neuronal connections between these crucial structures for normal human language functioning and that these anomalies are genetically controlled and develop slowly over time. From late adolescence to early adulthood as these connections reach maturity and a peak level of myelination, a threshold is reached whereby nor- mal language pathways are disrupted (DeLisi, 2004). The standard account of schizophrenic language today is that of Anderson (1979 as cited in Covington et al., 2005: p. 88). This is a scale which comprises 16 symptoms: poverty of speech, poverty of content (wordy vagueness), pressure of speech (excessive speech or emphasis), distractibility (by stim- uli in the environment), tangibility (partly irrelevant replies), loss of goal, derailment (loss of goal in gradual steps), circum- stanciality (numerous digressions on the way to the goal), il- logicality, incoherence (word salad), neologisms (novel made-up words), word approximations (coined substitutes for existing words, stilted speech (pompous or overly formal style), clanging perseveration, echolalia, blocking (sudden stoppage), and self-reference (talking about oneself excessively). Method Participants A community sample including 10 males ranging from 25 to 44 years old was selected from a mental hospital and a charity center in which mental patients were kept. Two participants who had a good command of English were ignored after the interview, and only eight could attend the class and fulfill the tasks. They all were educated and had passed high school courses. The method of selection was purposive sampling (ob- taining certain participants with pre-determined characteris- tics), due to the limitation we had in accessing schizophrenics. Besides, schizophrenia is an impairment that causes the same impairments in all sufferers worldwide and might not make much difference in different settings, ethnic groups, or races (Graham, Gath, & Mayou, 1999). All of the participants were recognized as schizophrenics by the psychiatrists and had re- cords in the hospital and had been hospitalized there for at least five months at the time of the study. Based on the ar- chived records, which were attested later during the class, two of them were recognized as disorganized type with flat emo- tional expression and severely disorganized speech, five para- noid types and one undifferentiated type. Kurdish was their native and Persian their second language and, based on the interview administered to homogenize the samples, their Eng- lish proficiency level was limited to just familiarity with Eng- lish alpha bet. Materials The background information of the patients was the first to be provided in order to select proper samples for the research since patients with schizophrenia are the goal. This information was provided in the archive room of both mental hospital and the mental center with the permission of their managers. An interview then was designed to check the patients’ vocabulary knowledge making sure that they had no prior word power. This interview took about 15 minutes for each as they were asked to say English alphabet, then naming objects around and recognizing some words chosen from those in the syllabi. Since this study aims to investigate the ability if schizophrenics to recall the thought vocabulary in a kind of achievement course, those samples with no prior word power would best work. Each syllabus contained three to four words. In this regard, Thorn- bury (2002) suggested that the vocabulary presentation should not extend at most about a dozen items which is based on a number of considerations such as the level of the learners, the difficulty of the items, teachability of them and even whether the items are being learnt for production or recognition only. Since more time will be needed for the former, the number of items is likely to be fewer than when the aim is only recogni- tion (pp. 75-76). Since nouns are more teachable, that is, they can be ex- plained or demonstrated (Thornbury, 2002: p. 76), 18 of the 38 items chosen in the syllabi were nouns. These 38 items were of seven categories as objects, foods, sports, animal, colors, ac- tions, and adjectives (see Appendix 1). Each syllabus was de- signed to help the patients practice and memorize the items every session with a memory game in the end. The words in the syllabi were presented through five tasks: matching words to the pictures, word association, filling the gaps, crossword puzzle, and finding words.(see Appendix 2) Two sets of cards were selected: let’s go flash cards by Tavak- koli (2008) and the other opposite’s flashcards by Shirkhani (2008).  A. HAYATI ET AL. 419 Procedure Since schizophrenics are not generally found in every hospi- tal, and are only hospitalized in mental hospitals or centers where they are taken care of, two of these centers out of three located in Sanandaj were selected. Qods Mental Hospital lo- cated in a remote part of the city was the first to visit and, with the permission of the manager, it was possible to reach the ar- chive, library, as well as the patients and a room in which the classes could be held two sessions a week. Each session lasted around 40 minutes in an eight week period. The above coordi- nation was made in the other center which was a charity one responsible for the chronic schizophrenics under the supervi- sion of welfare organization. Based on the list provided, an oral interview was designed and administered in order to select the samples that were both schizophrenics and had very limited number of English words. The first session was spent on practicing the English alphabet making sure that all participants were familiar with English sounds and letters. Two methods were used to present the meaning of the vocabulary presented. Three new words were presented each session first through showing pictures on flash cards as they were read aloud in the class. As Thornbury (2002) points out, this method is meaning-first since the sequence of presenting might be effective. There is an argument that pre- senting the meaning first creates a need for the form, opening the appropriate mental files and making the presentation both more efficient and more memorable. On the other hand, form-first presentation works best when the words are pre- sented in some kind of context, so that the learners can work out the meaning for themselves. Second, Since translation has been the most widely used means of presenting the meaning of a word in monolingual classes it was provided then because it has the advantage of being the most direct way to a word’s meaning assuming that there is a close match between the target word and its L1 equivalent (Thornbury, 2002: pp. 76-77). After the students did all the tasks, a memory game was set out. Four pictures were shown to a patient letting him watch for a while, and then one picture was removed asking the individual par- ticipant to name the removed picture. The final task was to ask them to draw the learnt words on the board. These two final tasks, however; is not included for the evaluation of the patients and were administered for the sake of practicing the taught vocabulary. The class lasted for 16 sessions and the first test was admin- istered two weeks later to find out how many of the vocabulary items were retained. The retest, exactly the same test as the first, was administered 16 days later. Twenty words were randomly chosen from the syllabi and one picture was shown at a time to the patient to elicit the English word. Since the aim was to find out if they could remember or even recognize the words, a list was shown in case they could not remember. The result is based on data provided from three assessment devices: tasks which have been done during the sessions, test, and retest. Papers given from the sessions told us about pa- tients’ capability in fulfilling different kinds of tasks such as matching words to the pictures, word association, filling the gaps, crossword puzzle, and finding words out of which the final two require more mental ability on the part of the learners. The effect of age on patients’ achievement is determined by putting them into two groups; first, patients being more than 30 years and second, those with below 30 years of age. On two different diagrams, the groups’ average percentages of task done is shown and compared. Results The data on matching words to the pictures shows a fluctua- tion with the undifferentiated type patient doing all the tasks correctly and two disorganized types scoring the worst with lack of ability in doing any of the tasks in the syllabi. More, only three out of eight patients showed a figure below average whereas most of them could reach out to above average point of 53 percent (Figure 1). The Figure 2 on word association task shows a marked de- crease in the patients’ attendant to the tasks with the two disor- ganized type with no correct answers and undifferentiated scoring well. The average in this task is 42 percent meaning that they have done 11 percent less compared with that of matching words to picture. Filling the gap tasks which required the patients to provide written answers to the blank spaces based on the pictures show almost similar results to the Figure 3 which was on word asso- ciation. One paranoid type patient seemed to show poorer abil- ity compared to the previous tasks and its performance is going downward while others are relatively doing well. One cognitive demanding task is crossword puzzle in which patients are required to fill in the blank boxes based on small clues available. The diagram below shows the percentage of correctly responded items in the crossword puzzle tasks by the Figure 1. Percentage of tasks by the patie nt s on m at c hi n g w o r ds to pictures. Figure 2. Percentages of tasks by the patients on word associ ation.  A. HAYATI ET AL. 420 Figure 3. Percentages of tasks by the p atients on filling the gaps. Figure 4. Percentages of tasks by the pati en t s o n cr o ss w o rd puzzle. patients. As can be seen from Figure 4, one paranoid ty pe hit the trough doing exactly no single task and another paranoid pa- tient had a significant decrease in its performance. The two disorganized types were not still able to carry out all the ques- tions. Figure 5 indicates the percentage of the patients’ ability in doing the final vocabulary task called finding words. The graph shows a drop in the performance of patients in doing the task. Compared with the other tasks, this graph has almost four pa- tients hitting the trough and a marked decline in two of them. While the average reached the bottom, just two patients could overtake the average and six stayed lower. The undifferentiated type still has the highest percentage with 100 percent perform- ance. The Figure 6 compares the patients’ performance on the tests. The first test was administered a week after the class and the retest was administered 16 days after the first test. Two para- noid patients scored lower on the retest while two performed better in it and two did the same. The two disorganized type could not answer any of the questions asked while the undif- ferentiated patient correctly answered all the questions. The Figure 7 shows the percentage of the tasks performed by patients in an age categorization. The highest percentage goes to a 44 year old undifferentiated patient and the lowest per- centage belongs to the two disorganized patients with 40 and 44 years old. The above figures can be categorized into two groups; first, patients being more than 30 years and those below 30 years of age. The Figure 8 shows that there is a very slight difference between the two groups of patients in their average tasks done. Figure 5. Percentages of tasks by the patients on fin di ng w ords. Figure 6. Percentage of patients’ perf o r m a nc e o n t e s t a n d r e t e st . Figure 7. Average percentages of all the tasks done by the patients. Figure 8. Average percentages of tasks by two groups of patients; under 30 and over 30.  A. HAYATI ET AL. 421 Discussion The study yields significant results in schizophrenia’s foreign language domain. Patients with schizophrenia showed different impairments in their attempt to learn foreign language vocabu- lary. These can be categorized into six abnormalities. Breakdown in Doing the Tasks Schizophrenics seem to have serious problem in thinking and doing tasks which are cognitively demanding. They failed not only in answering different vocabulary tasks but also in under- standing the tasks. They seemed very far from understanding them and their minds function as if there is just a simple logic behind every task. As they started with matching word to the pictures and drawing a line to match them, they simply did the same for all other tasks. The following figures show some of those tasks in which the patients showed abnormal perform- ances. They were supposed to fill in the gaps and provide the correct word but they simply drew a line and matched them to the pictures unexpectedly. Distorted thoughts resulted in a number of abnormal per- formances which are clear in the following task done by schizophrenics. Figure 9. Average percentage of tasks d o ne by the patients. In addition, as the order of the tasks move from simple to difficult and more cognitively demanding, the patients showed poorer results. Figure 9 on the average percentage of tasks done by schizophrenic shows the degree of tasks difficulty. As it is clear from the figure, they found finding words task most diffi- cult and it is the task in which the patients showed the least performance with doing almost a fifth of it. Word association also challenged their ability. The task with the highest percent- age was matching words to the pictures and they did well rela- tively. Novel Made-up Words Another abnormality observed was the creation of some non- sense words and writing them in the blanks as for the answers. This abnormality, known as neologisms, is clearly known and exists among the Anderson’s standard account of schizo- phrenic’s first language (1979 as cited in Covington et al., 2005). These made-up words and letters are so illegible and sometimes have no similarity with English letters. The following picture illustrates some of these abnormal language utterances. Code-Switching Schizophrenics tend to switch back to native language in the middle of the tasks while they were fully unaware of this. One of the patients diagnosed with disorganized type who suffers from speech disorders, when asked to read the English alphabet from the board, preceded as follows: /gi/ /pi/ /ye/ /gi/ /es/ /ge/ /dal/ /zal/  A. HAYATI ET AL. 422 He started with /g/ a letter from the middle of the alphabet list, saying some random letters; he switched to Persian alpha- bet all of a sudden and stopped soon after. Failure to Utter Lexical Items Schizophrenic patients, particularly those with language dis- order who failed to learn even a single English word, had seri- ous problems in naming objects and, as Chaika (1974 as cited in Covington et al.) observed, they fail to utter an intended word and their thought goes around word associations. These patien t s had difficulty in even repeating English words and tended to utter associative words in native language. When I asked an- other patient to say the sessions taught vocabulary, he said the following native words with confidence: edaray kargozini (personnel department), emarat (mansion), sakhteman (build- ing), bimarestan (hospital), hotel (hotel), rasturansh (restau- rant), kabara (bar). These irrelevant replies, named tangibility, are among the standard account of schizophrenic’s language of Anderson (1979 as cited in Covington et al., 2005: p. 88). When I showed him the following picture and asked him ‘’what are they doing’’(he was supposed to say ‘watching tele- vision’), he uttered these words; madrese (school), hayat (yard), baziye bacheha (children game). In the following pictures, notice the gap for the picture sand- wich in which one of the patients devises a blend word very similar to both sandwich and dog, while he could not simply name the dog. Another case is the repetition of words ‘tree’ and ‘door’ by one of the patient. When I asked him to pronounce these words, he followed as ‘’ tere’’, ‘’t..re’’, ‘’ter’’, ‘’der’’, ‘’dar’’ and he found it very difficult to pronounce the consonant cluster in the word ‘tree’ and finally he could not. Distractibility This kind of abnormality also exists in schizophrenics’ L1 (first language) production and has been observed by Chaika known as distraction by the sound or senses of words, so that a discourse becomes a string of word association rather than a presentation of previously intended information. (1974 as cite in Covington et al.) The last exercise in the following graph indicates how the girl’s clothing in the picture distracts the patient and led him to a wrong answer [Zendani (prisoner) instead of reading a book]. In the second figure the word food reminds him of the word football. After teaching the word ‘chair’, I asked one of them what ‘chair’ means and he answered ‘’yani chikar mikoni’’(what are you doing?), the sound /ch/ distracted him and reminded him of the expression in Persian beginning with the same sound. The following conversation happened between me and one of the patients: Me What is this in English (in native language)? [Pointing to the chair] The patient Sanandaj Me What is it again? The patient Sandali (chair) Me in English please! The patient Ja (seat) Conclusion The study has shed light on second language learning from a very different point of view and has provided some implica- tions regarding the similarities of first and second language  A. HAYATI ET AL. 423 learning from a psycholinguistic perspective. Since schizophrenics already speak a language and due to mental impairments they suffer from language disorder, conse- quently they show the same difficulty in an attempt to learn a foreign language. Due to mental problems, all schizophrenics show a kind of language disorder in their first language and this is more complicated when it comes to those who are diagnosed with language disorders. As the study figured out, those with such a diagnosis could not perceive, understand, or produce a single vocabulary item of a foreign language. They tend to reveal the same impairments on their way toward learning a foreign language. Other types of schizophrenics who attempted to learn English vocabulary items also had difficulty in doing the activities; the more cognitively demanding the task, the harder they found it to do. The results on patients’ vocabulary retention also reveal that schizophrenics are able to recall English vocabulary items. They either are quick to produce the English word as soon as the picture is shown or they soon recognize the word in a list and point it if they are not able to pronounce it. The study also magnifies that age has no significant effect on schizophrenics to learn English vocabulary items. Both groups of patients, younger as well as older than 30, showed the same ability and had very similar results in doing all the vocabulary tasks. References Aitchison, J. (2008). The articulate mammal: An introduction to psy- cholinguistics (5th ed.). Canada: Routledge. Cardwell, M. (2003). Complete A-Z psychology: Handbook (3rd ed.). London: Bath Press Ltd. Celce-Murcia, M. (2001). Teaching English as a second or foreign language (3rd ed.). Boston: Heinle & Heinle. Coon, D. (2001). Introduction to psychology: Gateways to mind and behavior (9th ed.). Belmont: Wadswor t h. Covington, M. A., He, C., Brown, C., Naci, L., McClain, J. T., & Fjordbak, B. S. et al. (2005). Schizophrenia and the Structure of Lan- guage: The Linguist’s View. URL (last checked 7 December 2008) http://www.sciencedirect.com Davison, G. C., & Neale J. M. (2001). Abnormal psychology (8th ed.). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. DeLisi, L. E. (2004). Anomalous Language Perception and Speech of Schizophrenia. URL (last checked 21 June 200 9) www.ling.ed.ac.uk/ evolang/2004/ABSTRACTS/.../delisi.rtf Harvey, D. P., Wilcox, J. A., & Boudjenah, D. (2005). Schizophrenia in late life: Aging effects on symptoms and course of illness. The Ame- rican Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 2204. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.2204 Graham, G. M., Gath, D., & Mayou, R. (1999). Concise oxford text- book of psychiatry (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Hockenbury, D. H., & Hockenbury, S. E. (2004). Discovering psy- chology (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Worth Publisher. Lebedinskij, M. S. (1959). On Certain Features of Thought and Lan- guage of Schizophrenic s. URL (last checked 6 August 2008) www.orthomolecular.org/library/jom/1979/toc1.shtml Myers, D. G. (1996). Exploring psychology (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Worth Publisher. Sadock, B. J., & Sadock, V. A. (2005). Kaplan & Sadock’s comprehen- sive textbook of psychiatry (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Loppincott Wil- liams & Wilkins. Schmitt, N. (2002 ). Applied lin g ui st ics. London: Arnold. Scrivener, J. (1994). Learning teaching. Oxford: Macmillan Heinemann English Language Teaching. Shirkhani, E. (2008). Opposites flashcards. Esfahan: Jungle Publica- tions. Tavakoli, S. (2008). Let’s go flashcards. Tehran: Koshamehr. Thornbury, S. (2002). How to teach vocabulary. Essex: Pearson Educa- tion Limited.  A. HAYATI ET AL. 424 Appendix 1 Different Word Categories in the Syllabi Adjectives Actions ColorsAnimalsSports Foods Objects /slow Writing Red elephantSwimmingPasta Comb Strong/weak Watching GreenDog BasketballSandwichKey Hot/cold Driving Blue Mouse Skating Cake Clock Young/old Playing BrownCow Chess Hat Big/small Listening Duck Boat Reading Chicken 10 6 4 6 4 3 5 total 38 Appendix 2 Sample Tasks  A. HAYATI ET AL. 425 |