Journal of Service Science and Management

Vol.5 No.2(2012), Article ID:19210,11 pages DOI:10.4236/jssm.2012.52020

The Social Dimension of Service Workers’ Job Satisfaction: The Perspective of Flight Attendants

![]()

1Korean Air, Seoul, South Korea; 2Department of Management, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, USA; 3Department of Management, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, USA.

Email: *acipco@hanmail.net

Received April 18th, 2012; revised April 28th, 2012; accepted May 20th, 2012

Keywords: Job Satisfaction; Social Dimension; Service Workers; Job Performance; Flight Attendants

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study is to investigate the social dimension as a factor which affects service workers’ job satisfaction and the relationship between their job satisfaction and positive affectivity. This study surveyed 450 flight attendants of a major global airline. The results suggest that job satisfaction of flight attendants consists of four main factors: job itself (job motivation, job characteristic, authority, and responsibility), job environment (working condition, supervision, and coworkers), organizational characteristics (wage and employment stability, promotion, and organizational policy), and social dimension (occupational prestige, organizational reputation, and corporate social responsibility). The results also show that flight attendants’ job satisfaction significantly affects their positive affectivity. These results imply that the service organizations such as airline companies need to pay close attention to the social dimension as a factor of job satisfaction to improve service performance.

1. Introduction

Since the deregulation, the airline industry has become one of the most fiercely competitive industries [1]. To develop competitive advantage, airline companies have tried to improve their service performance by increasing service quality to customers. In the service organizations such as airline companies, the role of service workers is critical because the quality of service depends on the performance of service workers [2]. For airline companies, in-flight service by flight attendants is the key factor which determines passengers’ satisfaction and thereby loyalty [3]. Because the service quality can be influenced by the service workers’ attitude and affectivity which are outcomes of their job satisfaction, it is important to investigate workers’ job satisfaction to improve service performance.

Job satisfaction of service workers has been one of the central topics in organization research due to its impact on the organizational productivity and effectiveness. Much research has been done to evaluate the importance of job satisfaction [4-13]. However, much of this research has used a limited number of variables that are subjective and cognitive. Thus, these studies have some limitations in reflecting what service workers really consider important in doing their job. Previous studies which deal with job satisfaction have generally employed three dimensions: job itself, job environment, and organizational characteristics, focusing on the internal part of the organization.

To adequately evaluate the value and attitude of service workers, job satisfaction should be considered from the perspective of not only internal characteristics of the organization where service workers work, but also factors related to the job external of the organization such as evaluation of the job by other people. The idea that all occupations are equally valuable is a nice cliche, but the reality seems to be quite different. People tend to evaluate a person by the organization where he or she works at, rather than the person per se. People are curious about a person’s occupation and estimate the influence, income, and social status based on the occupation. That is, the occupation provides not only the information about what kind of work the person does, but entails an implicit evaluation of a person’s social status and capability. Therefore, the occupation that people especially consider to provide a higher income and better working conditions would provide a better reputation for the person than other jobs. A service worker who has an occupation with a good reputation would be proud of the job and may have a higher level of job satisfaction. Thus, in evaluating job satisfaction, the social dimension such as organizational reputation might be a critical factor which affects service workers’ job satisfaction.

There is a paucity of research on the social dimension of service workers’ job satisfaction. Airline companies are one of the representative service organizations which have relatively high organizational reputations. The flight attendant job is a popular occupation for college graduates in many Asian countries, especially in South Korea. Thus, this paper investigates the social dimension of job satisfaction by surveying flight attendants of the biggest airline company in South Korea, along the other traditional job satisfaction factors (job itself, job environment, and organizational characteristics).

The paper is organized as follows: In the next section, a brief literature review is presented on job satisfaction, the social dimension as a factor affecting job satisfaction, and the relationship between job satisfaction and work performance. Then, a theoretical model is developed based on the previous research to examine the social dimension as a job satisfaction factor and the impact of job satisfaction on job affectivity. The data collection process from flight attendants of one of the major international airline firms is presented. Data analysis results are presented and finally, we conclude the paper with a discussion of implications of the results, limitations of the study, and future research needs.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Job Satisfaction

Job satisfaction generally refers to the affectivity of employees who work to produce products or services regarding their job. Many scholars have presented a variety of definitions for job satisfaction. Hoppock [7] stated that job satisfaction is the synthesis of mental, psychological, and environmental situations which affect employees’ satisfaction from their work. According to Quinn and Magine [10], job satisfaction is the quantified degree of improvement based on the employees’ satisfaction with compensation, safety, and control regarding a particular work. Smith [12] referred job satisfaction as a series of attitudes emerging from the emotional status regarding job experiences. Locke [9] stated that job satisfaction is the employees’ positive or negative affectivity from the evaluation of job experiences.

From these previous studies, common characteristics about job satisfaction can be derived. First, job satisfaction is the emotional response to job experiences. Therefore, it can be understood only from the self-observation. Job satisfaction cannot be observed in the flesh, but can be felt from employees’ activity and linguistic expression. Second, job satisfaction can be seen as a gap between expectation and reality regarding job experiences, as done by previous research. Overall, job satisfaction is somewhat a subjective concept. In this light, Salancik and Pfeffer [11] emphasized that job satisfaction should be estimated through observing other employees working in a similar job rather than only the information about the job per se.

Herzberg et al. [6] stated, in his dual factor theory, that a factor affecting employees’ satisfaction is different from a factor for dissatisfaction. He focused on the fact that employees’ dissatisfaction is related to job environment, while satisfaction is related to job contents. The factor of dissatisfaction, called the hygiene factor, includes the firm’s policy, control and monitoring, work condition, relationship with peer workers, wage and compensation, etc. On the other hand, the factors of satisfaction, called a motivation factor, includes achievement, recognition, job itself, obligation, improvement, self-realization and so on.

Weiss et al. [13] classified job satisfaction factors as intrinsic, extrinsic and overall factors by using such concepts as achievement, job activity, authority, creativity, independence, moral value, obligation, stability, social responsibility, social status, diversity, control, peer workers, firms’ policy, wage, promotion, work condition, work environment, and so on. Locke [9] suggested that the job satisfaction factor consists of job factors and human factors. Job factors include job itself, wage, promotion, recognition, and work condition, while human factors include such personal factors as a set of value and ability, an external human factor related to senior workers and peer workers inside the organization, and an external human factor related to customers and stakeholders outside the organization. Jurgenson [8] proposed ten factors affecting job satisfaction such as wage, additional compensation, promotion opportunity, work time, peer workers, control, stability and safety, work condition, and organization. Porter et al. [14] classified job satisfaction factors as organization (wage, promotion opportunity, and policy and process), work environment (control, participation, and peer relationship), work contents (span of work, role ambiguity, and role conflict), and personal characteristics.

The previous research has generally dealt with job satisfaction as a combination of job contents, job environment, and organizational characteristics without careful attention to the social dimension such as organizational reputation and social recognition about the occupation. Only a limited number of studies, such as Weiss et al. [13], partly dealt with the social dimension by using variables such as moral value and corporate social responsibility. However, the social dimension outside the organization actually plays an important role in job selection as much as internal factors of the organization.

2.2. Social Dimension as a Factor of Job Satisfaction

Sociologists have investigated social assets that most people generally hope to attain such as occupational prestige [15,16] and social status [17]. Weber [18] provided the insight that occupations can be evaluated in terms of their associated social status. Social status is determined by reputation, authority, importance, and value given in the society [18]. From then on, scholars have further elaborated the concepts of social prestige and status, developing occupational prestige scores and socio-economic index, and concluded that good occupations could be determined by social status [16,19-22]. Yoo [23] stated that the occupational prestige is a subjective criterion compared to income, but there exists a considerable degree of consensus about the relative status of different type of occupations.

Festinger [24], in his social comparison theory, stated that a person selects a similar other person to evaluate himself when there is no objective criterion for evaluation. By comparing oneself with others, a person may feel satisfaction and self-confidence or experience disappointment and frustration. Social comparison consists of upward comparison which is the comparison with people in better conditions, and downward comparison which is the comparison with people in worse situations. People develop the self-enhancement desire as well as selfevaluation desire, and then use both upward and downward comparisons [25-27]. Maslow [28], in his theory of needs hierarchy, also articulated about esteem needs to expect respect from others. When this need is satisfied, people can feel self-respect, value, and the feeling that he or she is a necessary person in society. Weber [18] focused on the process where social reputation and prestige are distributed through other criteria rather than economic reasons. In this light, Honneth [29] stated that social recognition plays a more important role in social conflict than economic distribution in the modern society.

2.3. Job Satisfaction and Performance

Employee job satisfaction is important in terms of organizational performance because employees’ positive or negative affectivity directly affects organizational effectiveness and performance. Using dual factor theory, Herzberg et al. [6] stated that once a motivation factor is satisfied, then it positively affects organizational performance. Schneider [30] and Locke and Latham [31] also found a significant positive relationship between job satisfaction and job performance. However, there are studies which showed different results such as Laffaldano and Muchinsky’s [32] study that showed a weak relationship between job satisfaction and performance. Brayfield and Crockett [33] found no relationship between job satisfaction and performance, while Babin and Boles [4] found diverse relationships depending on the situation.

Fishbein and Ajzen [34], in theory of reasoned action, stated that the factors affecting personal behaviors can be classified as attitude about behavior and subjective norm. In this theory, attitude is personal affectivity about performing a certain behavior and subjective norm is personal recognition about the environmental pressure given by society where a person is in. Fishbein and Ajzen [34] stated that the better result a person expects from a certain behavior and the more other people support the behavior, the more it is probable that the person performs the behavior. Eagly and Chaiken [35] suggested that people who are positive about a certain behavior tend to promote and support the behavior, and people negatively estimating the outcome of a behavior tend to oppose and interrupt the behavior. Barnard [36], in social exchange theory, elaborated that the willingness of employees to spontaneously contribute to the organization is different according to individuals and the degree of willingness reflects satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the organization. That is, if employees are satisfied with their job, they tend to positively act for the organization and improve performance.

In the service industry, Hartline and Ferrell [5] found that service workers’ job satisfaction is related with the customers’ perception of service quality in the hotel industry. Previous studies found that satisfied service workers with their job tend to voluntarily help their customers and improve service quality [31,37]. Schneider [30] found that job satisfaction is the main factor for delivering quality service. Based on the previous research, it is expected that job satisfaction affects job performance as job satisfaction influences service workers’ attitudes and efforts for their job.

Service workers do emotional labor which is their efforts to control their emotions and behave in the expected way even when what they actually feel is different on the job [38]. In the service organization where service workers provide services to customers in person, the emotion and affectivity of service workers can be very important factors affecting job performance [39]. The service workers’ affectivity not only influences personal performance but also organizational performance [40]. Thus, service organizations enact display rules which regulate particular expressions of emotions in a particular situation [41]. In most service organizations, the display rules generally emphasize the expression of positive affectivity such as happiness, warmth, and passion [42-44]. The display rules are the tools to achieve organizational goals [42]. Thus, the service workers’ expression of positive affectivity can be a positive factor of job performance.

3. Research Model

3.1. Hypotheses Development

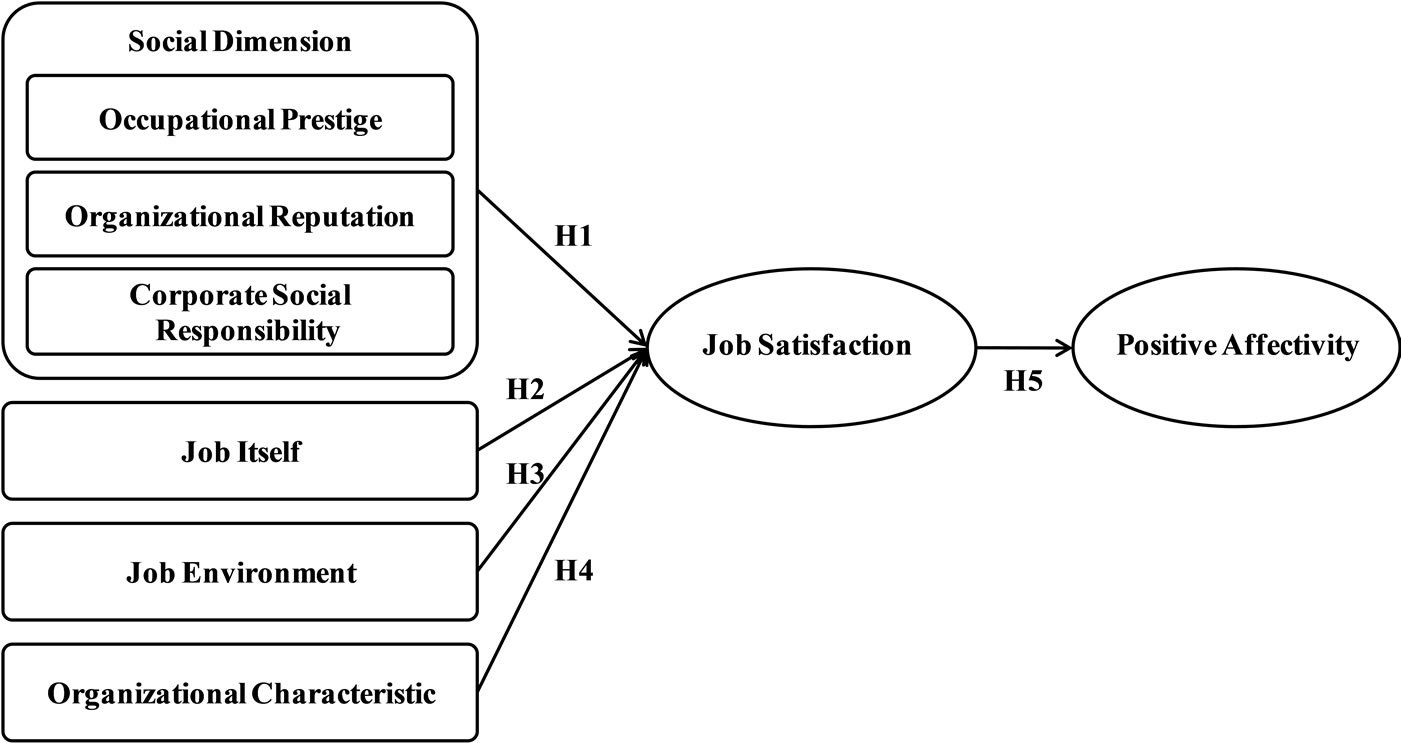

Based on previous studies, the social dimension might be one of the critical factors of job satisfaction. One of the purposes of this study is to investigate the social dimension as a factor of job satisfaction among service workers. This study investigated an international airline firm in South Korea, because flight attendants enjoy a relatively high social status compared to other occupations and one of service-oriented occupations where service workers’ job satisfaction is critical for organizational performance. This study examines the occupational prestige, organizational reputation, and corporate social responsibility as three factors of the social dimension of the occupation.

The occupational prestige is about the status of an occupation in the occupational structure [22]. That is, the occupational prestige is the status based on the subjective reputation or recognition about the occupation. In general, employees working in high-ranked occupations in terms of occupational prestige show a higher level of job satisfaction and lower turnover rate [45]. In South Korea, the flight attendant job has been considered a good job among college graduates in terms of wage and additional benefits such as discount flight tickets and traveling opportunities. In addition, the flight attendant is generally expected to be a beautiful lady or a handsome gentleman with self-confidence about her/his appearance. Thus, as an occupation, the flight attendant has been a popular and preferred job among young Koreans. Flight attendants in general might have self-respect and confidence about their occupation and this feeling might affect their job satisfaction. In this light, this study investigates the occupational prestige as one factor of social dimension.

Organizational reputation can be another factor of the social dimension. Organizational reputation is the overall long-term evaluation about the organization by its stakeholders [46]. Organizational reputation is different from organizational image in that the reputation is the stakeholders’ recognition over a long time period, while the image is the short-term recognition at a given time [46]. Dowling [47] stated that organizational reputation is the comprehensive evaluation reflecting the degree to which people consider if a certain organization is good or bad. The good reputation may create esteem, respect, trust, and confidence about the organization, but the bad reputation cannot create them. Organizational reputation may work as a non-monetary compensation for employees and increase employee engagement, thereby improving organizational performance.

Recently, corporate social responsibility has been paid attention because it affects a firm’s profitability and competence. Corporate social performance can increase the firm’s profitability through forming a positive company image to customers [48]. Barnett and Salomon [49] state that corporate social efforts can improve corporate impression perceived by society, thereby attracting valuable resources for improving organizational performance such as attracting better qualified workers and opportunities to expand the market base. Corporate social performance can be a standard by which future employees select their jobs [50]. Weiss et al. [13] also employed the items dealing with corporate social responsibility, even though their model did not include other social factors such as occupational prestige and organizational reputation. In this light, corporate social responsibility may increase job satisfaction and employee engagement.

Based on the literature reviewed above, the social dimension such as occupational prestige, organizational reputation, and corporate social responsibility may be the factors that affect flight attendants’ job satisfaction. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H1: The social dimension, including occupational prestige, organizational reputation, and corporate social responsibility, is one of the factors which affect job satisfaction of flight attendants.

Traditional studies about job satisfaction have generally dealt with job satisfaction as a combination of job content, job environment, and organizational characteristics as presented in the literature review. This study also investigates these factors of job satisfaction by using the sample of flight attendants. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed.

H2: Job itself positively affects job satisfaction of flight attendants.

H3: Job environment positively affects job satisfaction of flight attendants.

H4: Organizational characteristics positively affects job satisfaction of flight attendants.

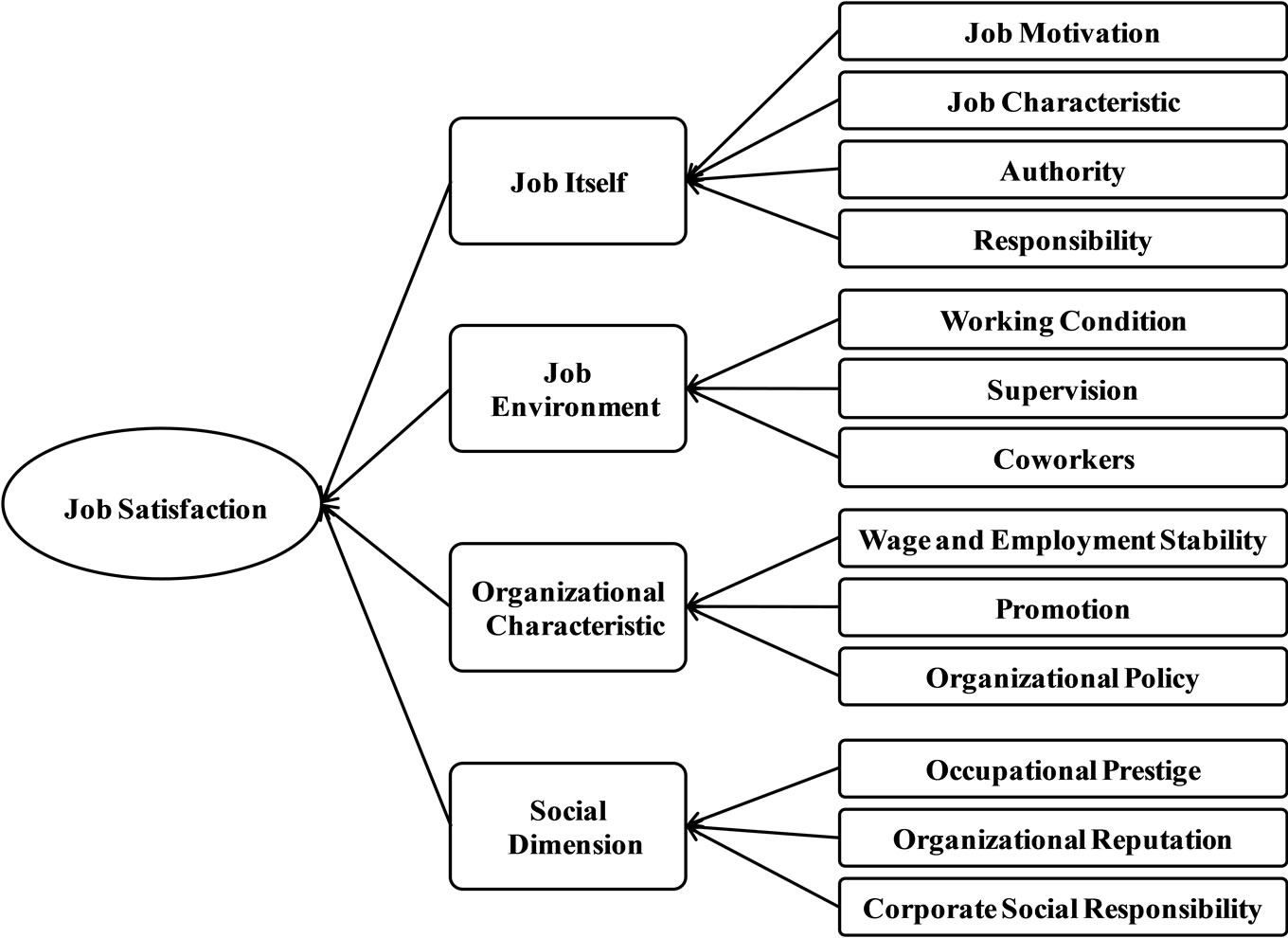

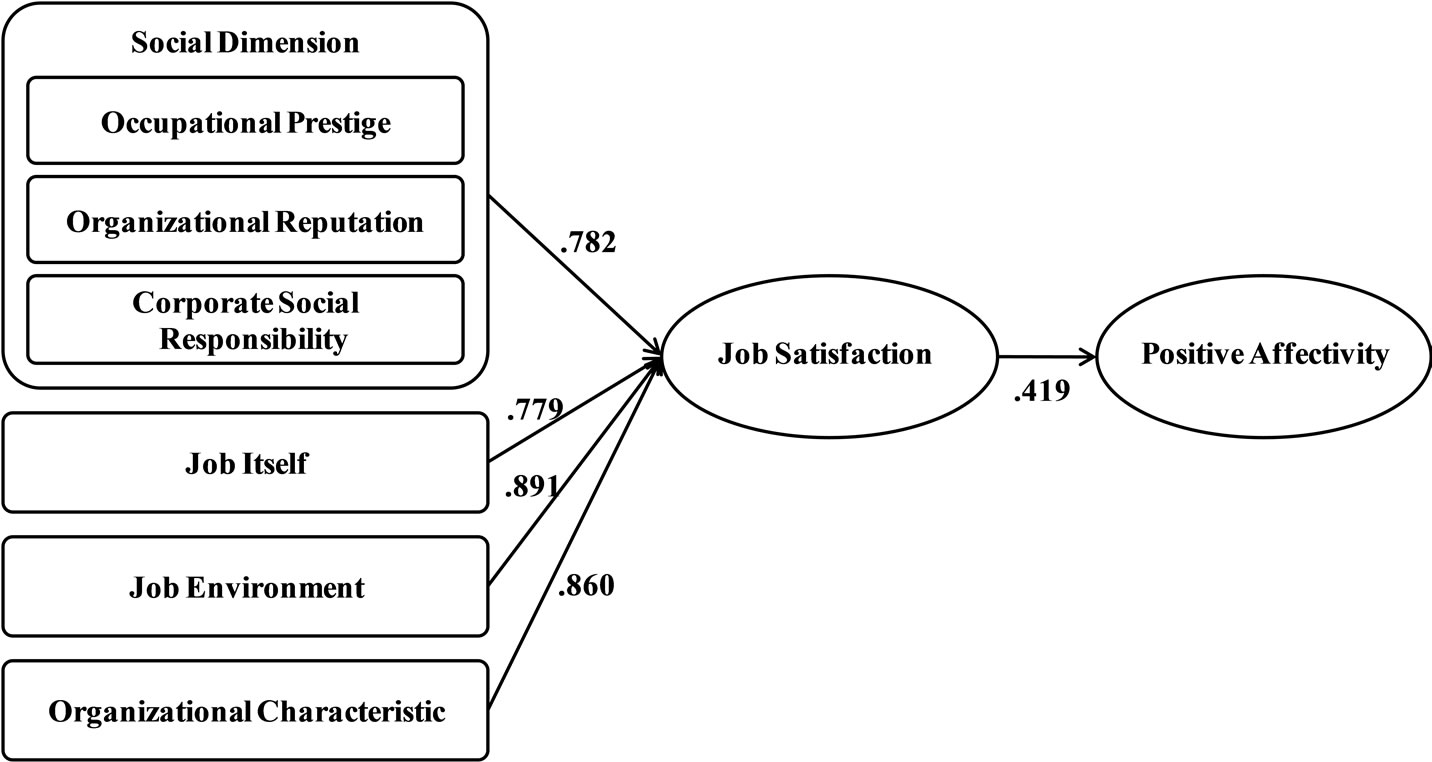

From the literature, job satisfaction is expected to affect service workers’ positive affectivity, which in turn contributes to improving job performance. Aselage and Eisenberger [51] stated that employees’ behaviors and attitudes toward the organization might be different depending on the material and social compensation given by the organization. The following hypothesis is suggested. Overall, Figure 1 shows the research model.

H5: Job satisfaction positively affects positive affectivity of flight attendants.

3.2. Sample and Data Collection

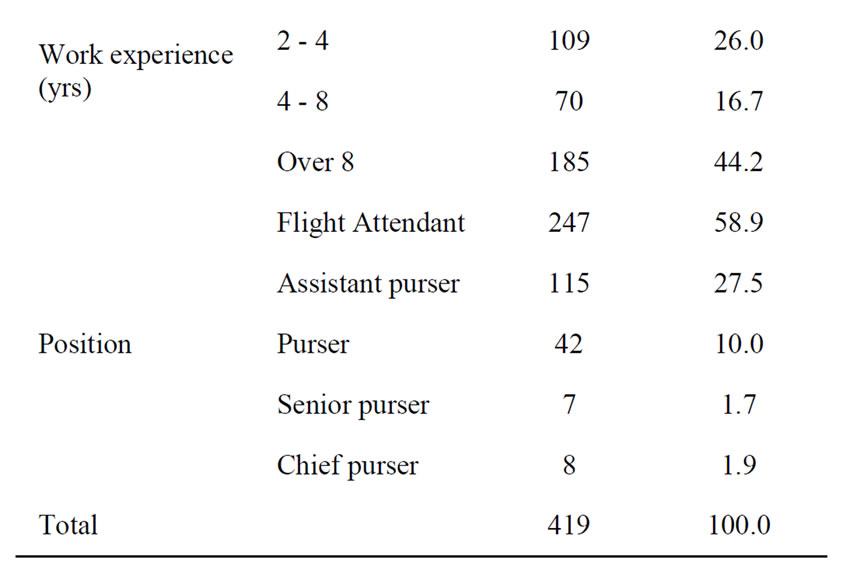

This study surveyed 45 teams (one team consists of 10 flight attendants) in the biggest airline company in South Korea. The pilot test was conducted by surveying 80 flight attendants and then the defects of questionnaire were supplemented. Then, this study surveyed 450 flight attendants and used 419 usable questionnaires for the analysis removing 31 questionnaires which were incompletely answered. The questions in the questionnaire used to measure variables were based on the seven point Likert scale. Table 1 shows the demographics of the sample.

Figure 1. Research model.

Table 1. Sample demographics of flight attendants.

3.3. Definition of Variables

As for the critical variables which constitute job satisfaction, this study adopted the variables in the previous studies on job satisfaction such as job itself, job environment, and organizational characteristic [6,8,9,13,14]. In addition, considering the lack of the previous research, this study developed the social dimension as one of the variables of job satisfaction. The social dimension consists of three factors such as occupational prestige, organizational reputation, and corporate social responsibility.

In order to evaluate social dimension as a critical factor of job satisfaction, this model is compared to that of MSQ (Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire) model [13] which has the items measuring factors of job satisfaction. This study used the same variables as MSQ model for traditional factors of job satisfaction such as job itself, job environment, and organizational characteristics. MSQ model also has the items dealing with the social dimension including moral value, corporate social responsibility and social status, even though it does not include other social factors such as occupational prestige and organizational reputation. By comparing to MSQ model, this study better shows the clear role of social dimension as a factor of job satisfaction in the service industry. The variables in this study are defined as below:

3.3.1. Job Itself

Job itself consists of authority and responsibility, creativity, recognition, ability utilization, sense of achievement, autonomy, and diversity.

1) Authority and responsibility: Chances to influence, instruct or order other people and obligations following a certain role in the organization.

2) Creativity: A characteristic of job creates new products, design, processes, and ideas which are valuable and creative.

3) Recognition: The degree to which service workers are recognized as good performers by their supervisors.

4) Ability utilization: The degree to which service workers can utilize their abilities and skills to conduct various duties.

5) Sense of achievement: The feeling of accomplishment when fulfilling job responsibilities successfully.

6) Autonomy: The degree of discretion in planning and conducting work.

7) Diversity: Opportunities to conduct a variety of works.

3.3.2. Job Environment

The job environment consists of working conditions, supervision, and coworkers.

1) Working conditions: Situational variables in conducting work such as temperature, humidity, illumination, on-duty hours, break time, etc.

2) Supervision: The relationship with service workers’ supervisors.

3) Coworkers: The relationship with peer workers.

3.3.3. Organizational Characteristics

Organizational characteristics consist of employment stability, wage, promotion, and organizational policy.

1) Employment stability: The degree to which service workers’ employment is guaranteed.

2) Wage: Economical compensation and payment.

3) Promotion: Vertical upward movement in the organizational hierarchy.

4) Organizational policy: Management policy and working procedures.

3.3.4. Social dimension

The social dimension is composed of occupational prestige, organizational reputation, and corporate social responsibility.

1) Occupational prestige: Evaluation of a certain occupation in terms of its status in the occupational structure.

2) Organizational reputation: The comprehensive longterm evaluation about the organization by its stakeholders.

3) Corporate social responsibility: Organizational activities to improve societal welfare without expecting reciprocal compensation.

3.4. Analysis of Data

A variety of statistical tools were employed to investigate the social dimension as a factor of flight attendants’ job satisfaction. First, frequency analysis was used to get demographic information of the sample. Second, reliability analysis and exploratory factor analysis were used to assess the data reliability and the factors affecting variables. Third, with the result of the exploratory factor analysis, confirmatory factor analysis was employed to investigate the appropriateness of factors. Finally, path analysis was used to verify relationships in the research model. SPSS WIN 16.0 and AMOS 7.0 were used for statistical analysis.

4. Results

4.1. Reliability and Exploratory Factor Analysis

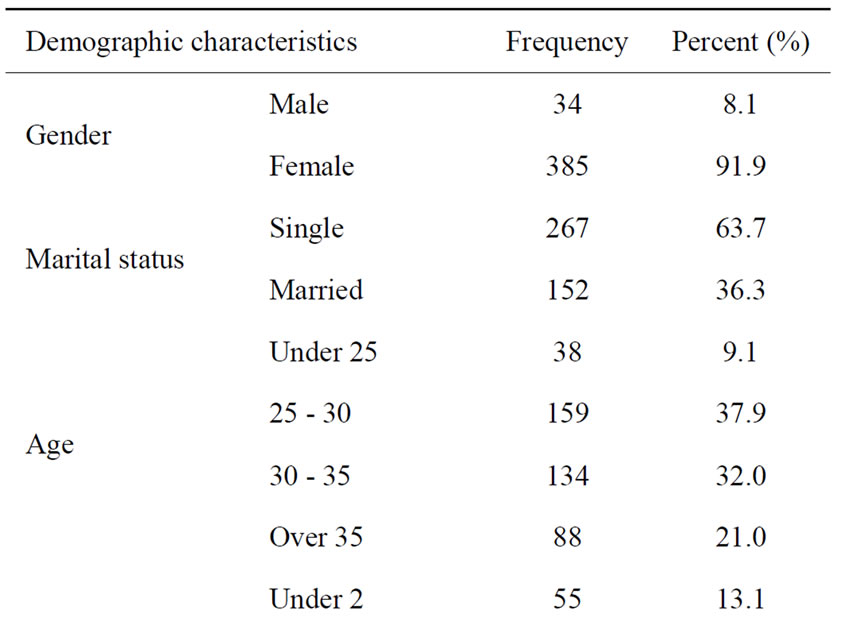

As a result of the exploratory factor analysis for the variable of job itself, four factors (job motivation, job characteristic, authority, and responsibility) were extracted after removing items loaded on more than two factors. Three variables of recognition, ability utilization, and sense of achievement in the research model were grouped into the factor of job motivation, and other three variables of creativity, autonomy, and diversity were resulted in the factor of job characteristic. The variables of authority and responsibility were resulted in two factors of authority and responsibility. The total accountability of these four factors was 60.05%, and the KMO (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy) value was 0.93. The result of Bartlett test of sphericity resulted in the p-value of 0.000. Table 2 shows the result of exploratory factor analysis for the variable of job itself.

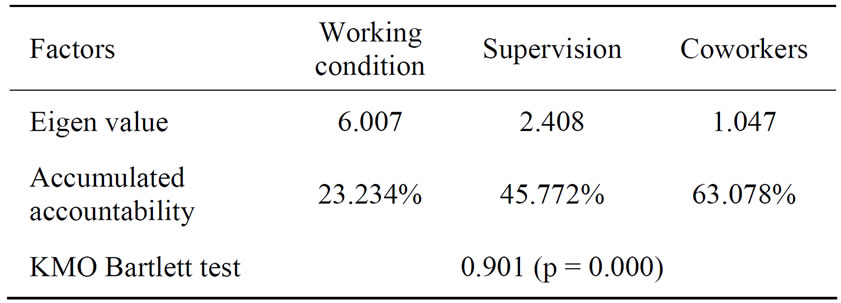

As a result of the exploratory factor analysis for the variable of job environment, three factors (working condition, supervision, and coworkers) were derived. The total accountability of these three factors was 63.08%, and the result of Bartlett test of sphericity showed the p-value of 0.000 with the KMO value of 0.90. Table 3 shows the result of the exploratory factor analysis for the variable of job environment.

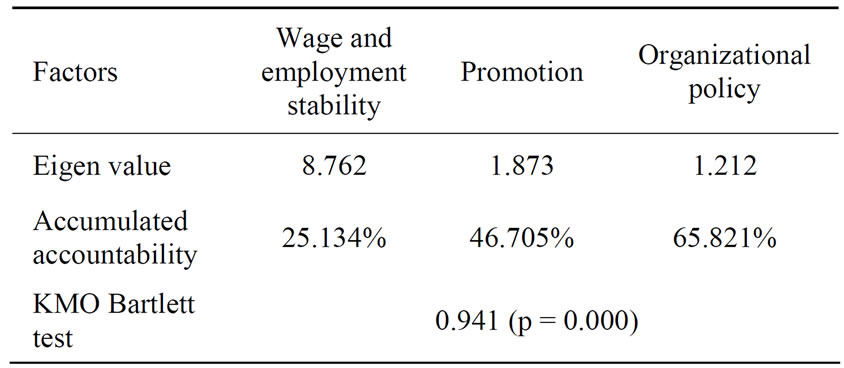

The result of the exploratory factor analysis for the variable of organizational characteristic is shown in Table 4. Three factors (wage and employment stability,

Table 2. Result of exploratory factor analysis for job itself.

Table 3. Result of exploratory factor analysis for job environment.

promotion, and organizational policy) were found and the total accountability of these three factors was 65.82%. The result of Bartlett test of sphericity showed the pvalue of 0.000 with the KMO value of 0.94.

In order to evaluate the social dimension in this study’s research model as a critical factor of service workers’ job satisfaction, the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ) model [13] was used together. This study made two alternatives for the MSQ model for the purpose of comparison. The first is the research model of this study suggested above where the social dimension consists of three factors of occupational prestige, organizational reputation, and corporate social responsibility. The second alternative is the mixed model where the factors of occupational prestige and organizational reputation are added to the MSQ model in which moral value, corporate social responsibility, and social status are considered as factors of social dimension.

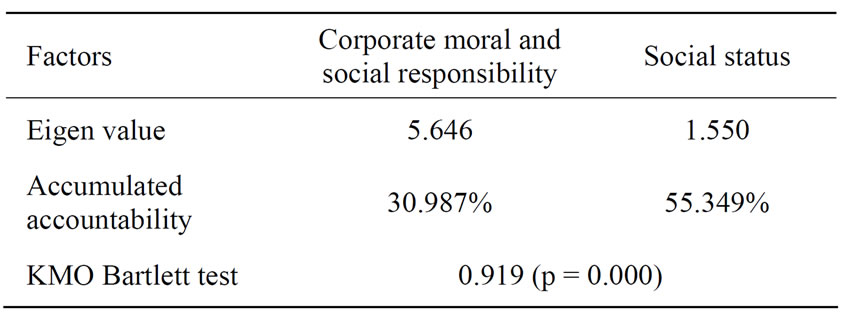

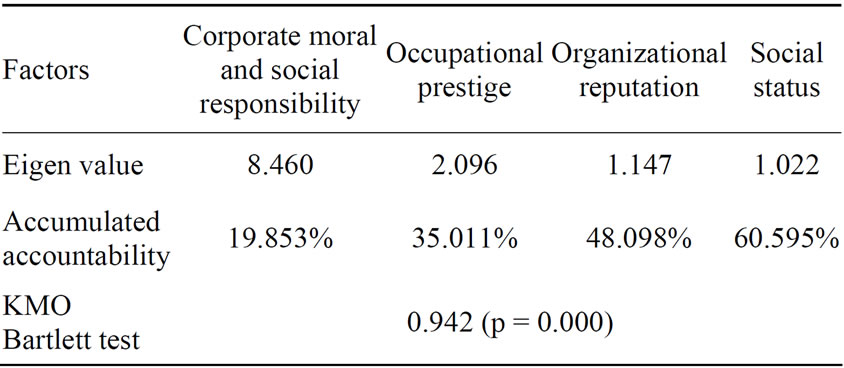

First, the exploratory factor analysis was conducted using the MSQ model, as shown in Table 5. As a result, moral value and corporate social responsibility resulted in one factor of corporate moral and social responsibility. Thus, two factors (corporate moral and social responsibility, and social status) were extracted and the total accountability was 55.35%. Because the accountability was under 60%, this study concluded that the MSQ model is not appropriate to evaluate the social dimension of flight attendants.

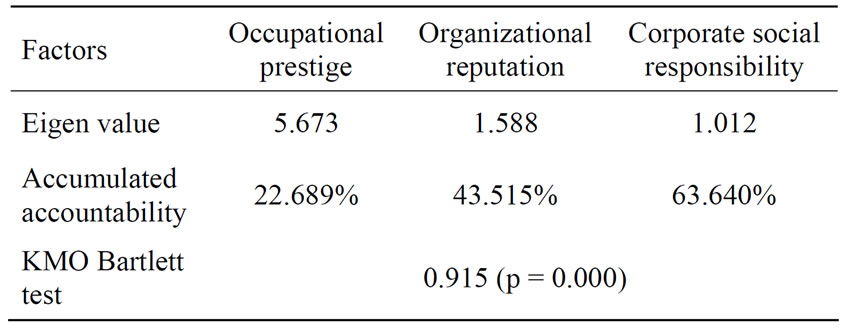

Second, the exploratory factor analysis for the first alternative was conducted as presented in Table 6. Three factors (occupational prestige, organizational reputation, and corporate social responsibility) were derived and the total accountability was 63.64%. The value of KMO was

Table 4. Result of exploratory factor analysis for organizational characteristic.

Table 5. Result of exploratory factor analysis for social dimension of the MSQ model.

0.915 and the result of Bartlett test of sphericity showed the p-value of 0.000.

Third, the exploratory factor analysis for the second alternative was conducted as presented in Table 7. Like the factor analysis on the MSQ model, moral value and corporate social responsibility resulted in one factor of corporate moral and social responsibility. As a result, four factors (corporate moral and social responsibility, occupational status, organizational reputation, and social status) were derived. The total accountability was 60.60% and the values of KMO and Bartlett test were 0.942 and the p-value of 0.000 respectively.

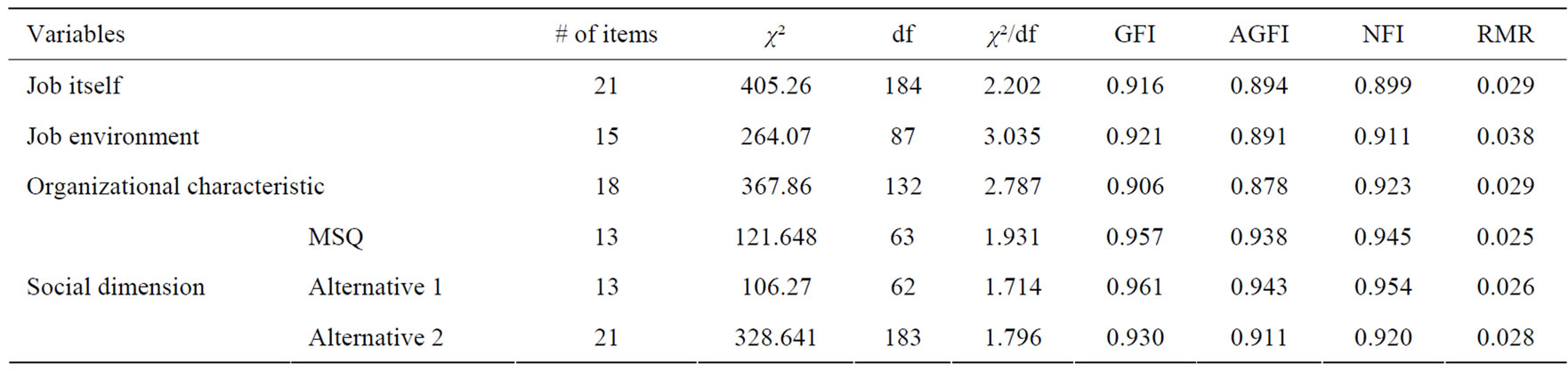

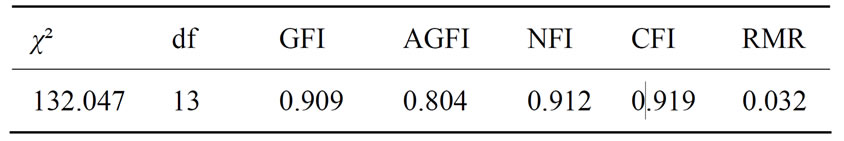

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

In order to confirm the structure of factors, this study employed the value of χ² (Chi-square), χ²/df, GFI (Goodness-of-fit index), AGFI (Adjusted goodness-of-fit index), NFI (non-normed fit index), RMR (Root mean square residual). Table 8 presents the results of confirmatory factor analysis on the variables of job itself, job environment, organizational characteristic, and social dimension of three research models. The values of GFI, AGFI, and NFI were mostly over 0.9 and the values of RMR were under 0.05. As for the social dimension, the first alternative showed better values of GFI, AGFI, NFI, and RMR compared to the MSQ model and the second alternative. Therefore, the first alternative is the most appropriate as it has the best goodness of fit among the three models.

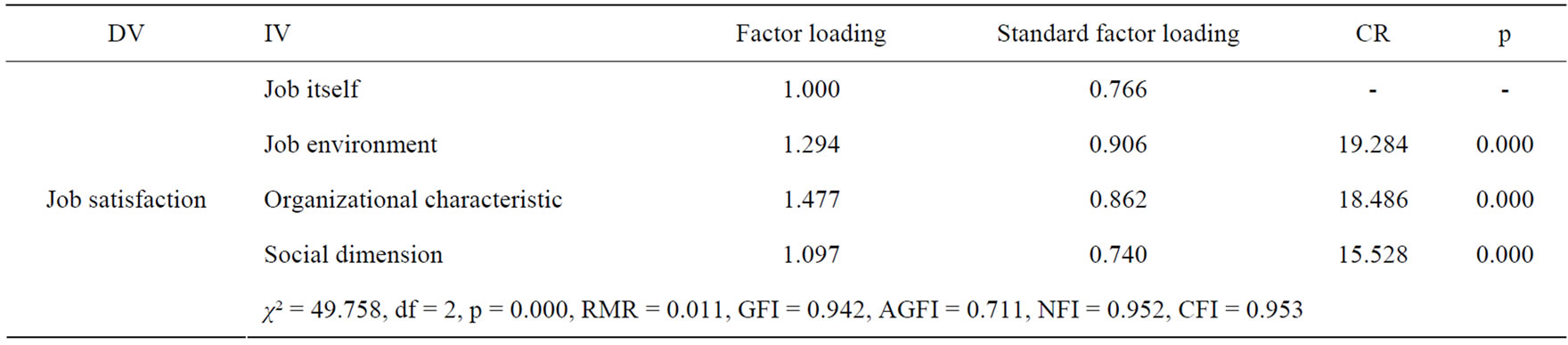

The goodness of fit test for the first alternative was conducted as shown in Figure 2 and Table 9. The values of CR, RMR, GFI, NFI, and CFI satisfied the criteria for

Table 6. Result of exploratory factor analysis for social dimension of the first alternative.

Table 7. Result of exploratory factor analysis for social dimension of the second alternative.

the goodness of fit. But, the value of AGFI was under 0.9.

Even if the AGFI value of the first alternative was under the criteria, it is close to the criteria. In addition, all other indexes satisfied the criteria. Thus, we can conclude that the first alternative is acceptable. Therefore, the first hypothesis that the social dimension such as occupational prestige, organizational reputation, and corporate social responsibility is one of the factors which constitute job satisfaction of flight attendants was supported. Also, traditional factors of job satisfaction such as job itself, job environment, and organizational characteristics are the factors of flight attendants’ job satisfaction.

4.3. Path Analysis

Figure 3 and Table 10 show the result of path analysis to examine the relationship among job satisfaction factors, job satisfaction and positive affectivity of flight attendants. Social dimension, job itself, job environment, and organizational characteristics positively affect job satisfaction of flight attendants with the impacts of 0.782, 0.779, 0.891, and 0.860, respectively. Thus, second, third, and fourth hypothesis that traditional factors of job satisfaction (job itself, job environment, organizational characteristics) positively affect job satisfaction of flight attendants were supported. The regression coefficient indicating the influence of job satisfaction on positive affectivity was 0.419 with the p-value under 0.01. Therefore, the fifth hypothesis that job satisfaction positively affects positive affectivity of flight attendants was supported.

5. Conclusions

The success of the airline company depends on attracting

Table 8. Result of confirmatory factor analysis on the variables constituting job satisfaction.

Figure 2. The first alternative.

Table 9. Result of goodness of fit test for the first alternative.

Figure 3. Relationship among job satisfaction factors, job satisfaction and positive affectivity.

Table 10. Result of path analysis.

new customers as well as retaining existing customers [52]. Therefore, the airline companies have tried to improve their service quality through purchasing new airplanes, upgrading in-flight facilities, cost reduction, and improving service quality [53]. In service organizations such as airlines, the quality of services delivered by service workers directly affects customers’ satisfaction and service workers’ affectivity significantly affects their job performance [2,54]. In-flight service delivered by flight attendants plays an important role in passengers’ satisfaction and loyalty. Due to the fact that in-flight service quality can be influenced by the flight attendants’ affectivity, it is important to investigate the factors affecting their job satisfaction and the relationship between job satisfaction and their positive affectivity.

The result of this study shows that job satisfaction consists of four factors of job itself (job motivation, job characteristic, authority, and responsibility), job environment (working condition, supervision, and coworkers), organizational characteristic (wage and employment stability, promotion, and organizational policy), and the social dimension (occupational prestige, organizational reputation, and corporate social responsibility). Whereas the previous research focused on the traditional factors of job satisfaction such as job itself, job environment, and organizational characteristic, this study found that the social dimension is also one of the critical factors constituting job satisfaction. Further research on the social dimension as a factor of job satisfaction would contribute to the development of job satisfaction research in the service industry.

This study also presents that service workers’ job satisfaction significantly influences the positive affectivity. This result is consistent with the previous research of Barnard (1938) that the willingness of employees to spontaneously contribute to the organization is different according to individuals and the degree of willingness reflects satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the organization. Aselage and Eisenberger (2003) also pointed out that the employees’ behaviors and attitudes toward the organization become different depending on the material and social compensation given by the organization. That is, the satisfied service workers with their job would have the positive affectivity and willingness to voluntarily contribute to their organization, and these efforts would lead to improved job performance.

This study has limitations of external validity because the data were collected from only one airline company in South Korea. In addition, some of flight attendants might not have honestly answered the survey, since the questionnaire dealt with some sensitive issues involving the company or their managers. However, this study tried to minimize the halo effects by ensuring confidentiality of individual identity. Second, this study confines the factors of the social dimension into occupational prestige, organizational reputation, and corporate social responsibility. However, there might exist other variables which can better explain the social dimension of flight attendants. Further research on the social dimension as a factor of job satisfaction would provide better insights for the understanding of employee affectivity.

REFERENCES

- M. Mazzeo, “Competition and Service Quality in the U.S. Airline Industry,” Review of Industrial Organisation, Vol. 22, No. 4, 2003, pp. 275-296. doi:10.1023/A:1025565122721

- S. L. Wilk and L. M. Moynihan, “Display Rule Regulators: The Relationship between supervisors and Worker Emotional Exhaustion,” Journal of Applied Psychology, vol. 90, no. 5, 2005, pp. 918-927. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.90.5.917

- M. An and Y. Noh, “Airline Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty: Impact of In-Flight Service Quality,” Service Business: An International Journal, Vol. 3, No. 3, 2009, pp. 293-307. doi:10.1007/s11628-009-0068-4

- B. J. Babin and J. S. Boles, “The effects of Perceived Co-Worker Involvement and Supervisor Support on Service Provider Role Stress, Performance and Job Satisfaction,” Journal of Retailing, Vol. 72, No. 1, 1996, pp. 57- 75. doi:10.1016/S0022-4359(96)90005-6

- M. D. Hartline and O. C. Ferrell, “The management of Customer Contact Service Employees: An Empirical Investigation,” Journal of Marketing, Vol. 60, No. 4, 1996 pp. 52-70. doi:10.2307/1251901

- F. Herzberg, B. Mausner and B. Snyderman, “The motivation to work,” John Wiley and Sons, New York, 1959.

- R. Hoppock, “Job satisfaction,” Harper and Row, New York, 1935.

- C. E. Jurgenson, “Job preferences: What makes a job good or bad?” Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 63, No. 3, 1978, pp. 267-276. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.63.3.267

- E. A. Locke, “The nature and causes of job satisfaction, Handbook of Industrial and Organization Psychology,” Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto, 1976.

- R. P. Quinn and T. W. Magine, “Evaluation weighted of model of Measuring Job Satisfaction: A Cinderella story,” Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, Vol. 10, No. 1, 1973, pp. 1-23. doi:10.1016/0030-5073(73)90002-0

- G. R. Salancik and J. Pfeffer, “An examination of Need Satisfaction Models of Job Satisfaction,” Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 22, No. 3, 1977, pp. 427-456. doi:10.2307/2392182

- H. C. Smith, “Psychology of Industrial Behavior,” McgrawHill, New York, 1975.

- D. J. Weiss, R. V. Davis, G. W. England and L. H. Lofquist, “Manual for the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire,” University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, 1967.

- L. W. Porter, R. M. Steers, R. T. Mowday and P. V. Boulian, “Organizational Commitment, Job Satisfaction and turnover among Psychiatric Technicians,” Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 59, No. 5, 1974, pp. 603-609. doi:10.1037/h0037335

- K. A. Bollen, “Structural equations with Latent Variables,” Wiley, New York, 1989.

- D. J. Treiman, “Occupational prestige in Comparative Perspective,” Academic Press, New York, 1977.

- A.L. Kalleberg and S. Vaisey, “Pathways to a Good Job: Perceived Work Quality among the machinists in North America,” British Journal of Industrial Relations, Vol. 43, No. 3, 2005, pp. 431-454. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8543.2005.00363.x

- M. Weber, “Economy and society,” Bedminster Press, New York, 1968.

- P. M. Blau and O. D. Duncan, “The American occupational structure,” Wiley, New York, 1967.

- L. Broom and P. Selznick, “Sociology: A text with Adapted Readings,” Harper and Row, New York, 1973.

- H. B. Ganzeboom, P. M. De Graaf and D. J. Treiman, “An International Scale of Occupational Status,” Social Science Research, vol. 21, 1992, pp. 1-56. doi:10.1016/0049-089X(92)90017-B

- M. G. Powers, “Measures of Socioeconomic Status: Current Issue,” Westview Press, Boulder, 1982.

- H. Yoo, “Occupational sociology,” Kyungmoon Press, Seoul, 2000.

- L. Festinger, “A theory of Social Comparison Processes,” Human Relations, Vol. 7, 1954, pp. 117-140. doi:10.1177/001872675400700202

- G. R. Goethals and J. Darley, “Social Comparison Theory: An Attributional Approach,” Hemisphere, Washington DC, 1977.

- K. L. Hakmiller, “Threat as a determinant of Downward Comparison,” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 1, No. 1, 1966, pp. 32-39. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(66)90063-1

- D. A. Thornton and A. J. Arrowood, “Self-Evaluation, Self-Enhancement, and the locus of Social Comparison,” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 1, No. 1, 1966, pp. 40-48. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(66)90064-3

- A. Maslow, “Motivation and personality,” Harper, New York, 1954.

- A. Honneth, “The struggle for recognition: The moral grammar of Social Conflicts,” MIT Press, Cambridge, 1995.

- B. Schneider, “The Service Organization: Climate Is Crucial,” Organizational Dynamics, Vol. 9, No. 2, 1980, pp. 52-65. doi:10.1016/0090-2616(80)90040-6

- E. A. Locke and G. P. Latham, “A theory of Goal Setting and Task Performance,” Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, 1990.

- M. T. Laffaldano and P. M. Muchinsky, “Job satisfaction and Job Performance: A Meta-Analysis,” Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 92, No. 2, 1985, pp. 251-273. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.97.2.251

- A. H. Brayfield and W. H. Crockett, “Employee attitude and Employee Performance,” Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 52, No. 5, 1955, pp. 396-424. doi:10.1037/h0045899

- M. Fishbein and I. Ajzen, “Belief, Attitude, Intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research,” Addison-Wesley, Reading, 1975.

- A. H. Eagly and S. Chaiken, “The psychology of attitudes,” Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Fort Worth, 1993.

- C. I. Barnard, “The functions of the executive,” Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1938.

- K. A. Weatherly and D. A. Tansik, “Managing Multiple Demands: A Role-Theory Examination of the behaviors of Customer Contact Service Workers,” Service Marketing and Management, Vol. 2, 1993, pp. 279-300.

- A. R. Hochschild, “The Managed Heart,” University of California Press, Los Angeles, 1983.

- S. L. Wilk and L. M. Moynihan, “Display Rule Regulators: The Relationship between supervisors and Worker Emotional Exhaustion,” Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 90, No. 5, 2005, pp. 918-927. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.90.5.917

- R. J. Steinberg and D. M. Figart, “Emotional Labor Since the Managed Heart,” In: R. J. Steinberg and D. M. Figart, Eds., The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Sage, Thousand Oaks, 1999.

- B. E. Ashforth and R. H. Humphrey, “Emotional labor in Service Roles: The influence of identity,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 18, No. 1, 1993, pp. 88-115.

- R. Cropanzano, H. M. Weiss and S. M. Elias, “The impact of Display Rules and Emotional Labor on Psychological Well-Being at work,” In: P. L. Perrewe and D. C. Ganster, Eds., Research in Occupational Stress and Wellbeing, Emerald Group Publishing, Bradford, 2004, pp. 45-89.

- S. D. Pugh, “Service with a smile: Emotional contagion in the Service Encounter,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 44, No. 5, 2001, pp. 1018-1027. doi:10.2307/3069445

- A. S. Wharton and R. J. Erickson, “Managing emotions on the job and at home: Understanding the consequences of Multiple Emotional Roles,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 18, No. 3, 1993, pp. 457-486.

- D. B. McFarlin and P. D. Sweeney, “Distributive and Procedural Justice as predictors of satisfaction with personal and Organizational Outcomes,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 35, No. 3, 1992, pp. 626-637. doi:10.2307/256489

- J. M. T. Balmer and S. A. Greyser, “Managing the multiple identities of the corporation,” California Management Review, Vol. 44, No. 3, 2002, pp. 82-86.

- G. R. Dowling, “Corporate Reputations—Should You Compete on Yours,” California Management Review, Vol. 46, No. 3, 2004, pp. 19-36.

- S. A. Waddock and S. B. Graves, “The Corporate Social Performance—Financial Performance Link,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 18, No. 4, 1997, pp. 303-319. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199704)18:4<303::AID-SMJ869>3.0.CO;2-G

- M. L. Barnett and R. M. Salomon, “Beyond Dichotomy: The Curvilinear Relationship between Social Responsibility and Financial Performance,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 27, No. 11, 2006, pp. 1101-1122. doi:10.1002/smj.557

- D. B. Turban and D. W. Greening, “Corporate Social Performance and Organizational Attractiveness to Prospective Employees,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 40, No. 3, 1996, pp. 658-672. doi:10.2307/257057

- J. Aselage and R. Eigenberger, “Perceived Organizational Support and Psychological Contracts: A Theoretical Integration,” Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 24, No. 5, 2003, pp.491-509. doi:10.1002/job.211

- P. Jiang and B. Rosenbloom, “Customer intention to return online,” European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 39, No. 1, 2005, pp. 150-174. doi:10.1108/03090560510572061

- H. Landrum, V. R. Prybutok and X. Zhang, “A comparison of Magal’s Service Instrument with SERVPERF,” Information and Management, Vol. 44, No. 1, 2007, pp. 104-113. doi:10.1016/j.im.2006.11.002

- M. An and Y. Noh, “Service-orientation of Airlines: Its Impact on Service-Oriented Behavior of Flight Attendants and Customer Loyalty,” International Journal of Services Sciences, vol. 4, no. 2, 2011, pp. 174-190. doi:10.1504/IJSSCI.2011.045579

NOTES

*Corresponding author.