Journal of Cancer Therapy

Vol.4 No.3(2013), Article ID:31608,8 pages DOI:10.4236/jct.2013.43090

Heat Shock Protein 40 (Hsp40) and Hsp70 Protein Expression in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OSCC)

![]()

1Department of Dental and Oral Disease, Faculty of Medicine, University of Sebelas Maret, Surakarta, Indonesia; 2Departement of Pathobiology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia; 3Department of Biology, Faculty of Science and Mathematica, University of Sebelas Maret, Surakarta, Indonesia; 4Department of Ear-Nose-Throat, Faculty of Medicine, University of Sebelas Maret, Surakarta, Indonesia.

Email: drgadiprayitno@yahoo.com

Copyright © 2013 Adi Prayitno et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received March 17th, 2013; revised April 16th, 2013; accepted April 23rd, 2013

Keywords: Chaperone; Hsp40; Hsp70; Misfolding; OSCC

ABSTRACT

Introduction: As a chaperone, heat shock protein acts as central integrators of protein homeostasis in cell. The form of these functions is to help setting up a complex protein molecular fold (folded protein) in many important settings, such as growth, differentiation, and the ability to live. It has become clear that the control system plays an important role if the folding process fails or an error occurs, causing folding abnormalities and targeted functionality to accumulate. The accumulation of faulty protein folding would harm cells and can result in death. Apparently, there is a correlation between protein folding error with various diseases, such as diabetes mellitus and cancer. Method: We examined protein levels in all samples using Dotblott with monoclonal antibody anti-Hsp40 and anti-Hsp70. Levels of the protein content was read using a densitometer. Modification of Dot Blot was as follows: treatment was conducted with 3 × SSC, added with 20 mL blocking solution, add with total protein samples of 10 mg/ml on nitrocellulose paper, prehybridized, incubated at 70˚ for 30 seconds, incubated at 70˚ for 30 seconds with primary antibody anti-Hsp40 or Hsp70 protein and then added with second antibody HRP anti-Hsp40 or Hsp70 protein, treated with 3 × SSC and visualized with TSA HRP, and then administered with streptavidin, biothynil tyramide, and, finally, added with chromogen (DAB) in a confined space. Result: From the analysis of the data using Manova test with Wilk’s Lambda, there were significant differences in the levels of Hsp40 between Benign Oral Lesion (mean 688.31 area) and OSCC (mean 1354.59 area) patients (p < 0.070), there was also a highly significant difference in Hsp70 levels between patients who experienced Benign Oral Lesion (mean 529.82 area) and OSCC (mean 1346.32 area) patients (p < 0.006). Conclusion: OSCC patients have increased Hsp70 levels, so it is possible that something is going wrong in protein folding. Errors in protein folding result in a new homeostasis or inhibition of apoptosis and increasing cell proliferation that triggers carcinogenesis. Hsp40 acts as co-chaperones.

1. Introduction

Heat shock proteins (Hsp), as molecular chaperones, act as central integrators of protein homeostasis in cell. Their function is to help setting up a complex protein molecule fold (folded protein), placing the protein in the cell and making proteolysis in many important settings, such as growth, differentiation, and the ability of cell life. Many data have shown basic plot, how chaperones facilitate transformation towards cancer at molecular level, and supports the concept that there are events of protein functional changes in carcinogenesis, which needs serious attention in the development of human cancers [1]. Most of the Hsp are molecular chaperones. Molecular chaperones bind to and stabilize proteins at intermediate state folding, assembly, translocation across membranes and degradation. Heat shock proteins are classified by molecular weight, for example, Hsp70 to BM 70kDa heat shock protein [2].

Several Hsps are molecular complex shaped and acts as a protein chaperone that binds linearly. Molecular chaperones act as a regulator of protein fate linearly through various ways, such as the folding of the protein in the cytoplasm, endoplasmic reticulum or mitochondria, which will also act as intracellular protein transport, repair or degrade, control the regulatory proteins and refold proteins fold incorrectly. Heat shock proteins are distinguished according to its location and function. Mammalian heat shock proteins can be classified into several families according to the size of molecules, which are: Hsp90, Hsp70, Hsp60 and Hsp40, and the small Hsp (sHsp) such as Hsp27 [3,4].

In some organisms, certain Hsp70 binds to newly transted proteins in the ribosome [5]. Some reports suggest that complex high-molecular-weight protein consisting of various chaperones are associated with the newly translated protein chains during extension of the polypeptide chain, both in-vitro and in-vivo. The bond between Hsp70 with newly translated renaturation protein is observed in animal firefly (luciferase), which is in the cellree translation systems [6-8]. Several studies support the existence of co-translational interactions between molecular chaperones with newly translated proteins, particularly Hsp70 and, possibly, Hsp40. Interaction of Hsp40 (DnaJ) with newly translated protein is very short, in which 55 residues have been reported in animals fireflies, the luciferase and chloramphenicol acetyltransferase [9].

When studying such events, very simple protein, the DNA, will be transcribed into mRNA and we will get some protein. However, we often forget that the following process is a continuation of the third step, which involves folding a chain of amino acids into the 3-dimenonal structure of a functional form of the protein. The process turned out to be complex cellular processes. Although it has long been known that the amino acid chain has several ways to make adjustments that lead to active proteins, there are several other mechanisms that assist the folding process. The wizard will guide the start of amino acids born to achieve a form/structure right with infinite possibilities. It has become clear that the control system plays an important role if the folding process fails or an error occurs, causing folding abnormalities and targeted functionality to accumulate. The accumulation of faulty protein folding would harm cells and can result in death. Apparently, at the end of the decade the last mechanism was understood. Apparently, there is correlation between protein folding error and various diseases, such as Prione disease, diabetes mellitus and cancer, namely the existence of various forms of structural proteins accumulation and one folded. These circumstances lead to its use as the principle target of treatment [10].

Further developments on the definition of cancer have suggested that the incidence of cancer begins in the disorder at epigenetic level (Altered DNA methylation, chromatin alterations, loss of imprinting) and continues to change at the genetic level (mutations) [11]. Research in the last decade reported that allegedly increased expression of Hsp plays a role in fault denatured protein folding of newly translated protein and, as a result stressor, so the protein does not function normally [12- 16]. Confirming the previous statement, Hsp molecules are called molecular chaperones and play a role in homeostasis, allegedly facilitating the flow of apoptosis and cell proliferation and contribute to the principal flow direction changes cancer at the molecular level [1]. For example, heat shock protein, known to continuously and comprehensively express in most normal tissues and cancer [16], has implications for many protein interactions such as folding, translocation and prevent improper aggregation and degradation. Many proteins folding errors are implicated in functions that lead and contribute to the pathogenesis of pain, including cancer incidence [17,18].

2. Method

Protein isolation methods of Henk Schmits were done with some modifications [19]. Frozen tissue sections of 1 mm diameter was ground to separate the cells from one another and break up the cell walls are considered smooth the ice. Then, 10 ml lysosim solution (10 mg /ml) was added and allowed to stand at room temperature for 10 minutes, then placed in boiling water for 1 minute temperature and stored in refrigerator for 5 minutes. It was centrifuge at 3000 RPM for 20 minutes at 4˚C. Then the supernatant was removed and transferred to an ependorf tube.

Electrophoresis 12% SDS-PAGE was carried out to determine the expressed of the protein bands. The working of protein electrophoresis is as follows: Take 2 µL protein samples (total protein) and insert into microtube, then take and put into the wells of 12% SDS PAGE gels were prepared. Finally, carry on electrophoresis for 6 hours.

Protein levels in all samples were examined using Dot Blot with monoclonal antibody anti-Hsp40 (Bioreaction Stressgen SPA-400) and anti-Hsp70 (Stressgen Bioreaction C92F3A-5), Size of the protein content was read using a densitometer (Shimadzu CS 930, Dual Wave Length Cromato Scanner) [20]. Modifications of Dot Blot [21] are as follows: Treatment with 3 × SSC, blocking solution Squirt, Squirt (1drop), the yield of total protein samples 10 mg/ml on nitrocellulose paper, prehybridization, incubation at 70 for 30 seconds, and incubation at 70˚ for 30 seconds with primary antibody anti-Hsp40 or Hsp70 protein and secondary antibody HRP anti-Hsp40 or Hsp70 protein, treatments with 3 × SSC, added primary antibody anti-Hsp40 or Hsp70 protein and secondary antibody HRP anti-Hsp40 or Hsp70 protein sequence, visualization (with TSA HRP) was performed, and then administered with streptavidin, biothynil tyramide, streptavidin, biothynil tyramide, streptavidin, and chromogen (DAB) was given in a confined space. Protein is available, then dot blott test was done using monoclonal antibodies anti-Hsp40 (Stressgen Bioreaction SPA-400) and Hsp70 (Stressgen Bioreaction C92F3A-5). Positivity expression indicated by brown dots and power of expression is indicated by the thickness of the brown color.

3. Result

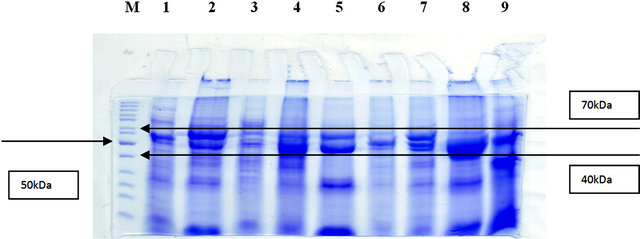

From 12% SDS-PAGE electrophoresis of protein the bands were expressed as can be seen in Figure 1.

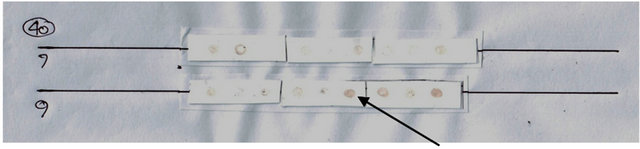

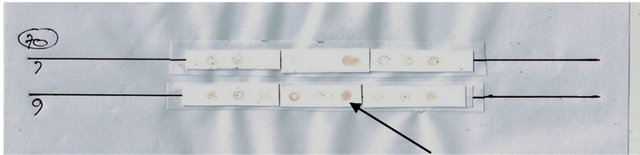

The power of protein expression results using Dotblott was then read using a densitometer (Shimadzu CS 930 Dual Wave Length Cromato Scanner), as found in Figures 2 and 3.

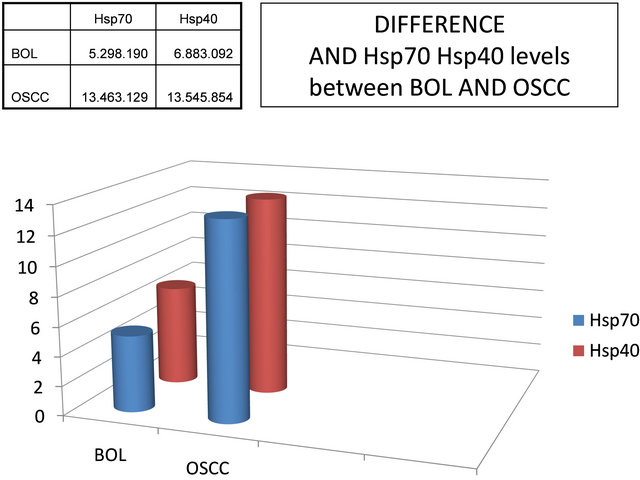

The results obtained in the mean levels of Hsp40 OSCC (Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma) patients by 13545.854 area, which was higher compared to that in patients with BOL (Benign Oral Lesion) of 6883.092 area, as did the average levels of Hsp70 for OSCC in patients by 13463.129 area, which was higher compared to that in patients with BOL of 5298.190 area (Figure 3).

(a)

(a) (b)

(b)

Figure 1. (a) SDS-PAGE electrophoresis using 12% total protein BOL; (b) SDS-PAGE electrophoresis using 12% total protein OSCC. M: Marker.

(a)

(a) (b)

(b)

Figure 2. (a) Results Dot blott Hsp40 expression among BOl and OSCC (top); (b) Results Dot blott Hsp70 expression among BOL and OSCC (bottom). Negatives: white; Positives: brown (arrows).

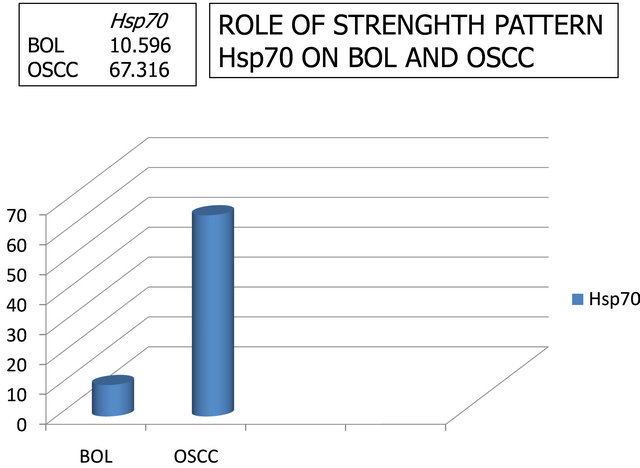

From data analysis in Figure 3 using Manova test with Wilk’s Lambda, there were significant differences in the levels of Hsp40 between BOL and OSCC patients (p < 0.070), and there was also highly significant difference in Hsp70 levels between patients who experienced BOL and OSCC (p < 0.006) (Figure 3).

From Wilk’s Lambda test it was found that only the existence of different Hsp70 was highly significant (p < 0.006), only the presence of Hsp70 will be analyzed using discriminant analysis.

The results of the discriminant analysis of the data in Figure 4 as function coefficients are presented in Figure 4. Anova test was done to differentiate between the levels of Hsp70 between BOL and OSCC patients, revealing high significant difference (p ≤ 0.0001). From data we can search the pattern of Hsp70 role in the pathogenesis of OSCC by doubling all BOL data (n = 9, Figure 1) to 0.002 (Function Classification Coefficients) and tuck all data on malignant lesions (n = 9, Figure 1) to 0.005 (Classification Function Coefficients), producing the mean of each group (benign and malignant), BOL patients for 10.596 area and OSCC patients for 67.316 area (or BOL: OSCC = 1: 6.7). That pattern of Hsp70’s role in the pathogenesis of OSCC was 6.7 times greater than the incidence in the pathogenesis of BOL (Figure 4).

4. Discussion

A chaperone is not acting alone, but acting as a group of various molecules, i.e. chaperones and cochaperones. Cochaperones are associated with chaperones, such as Hsp70 and Hsp40, and assist in a variety of roles. Another

Figure 3. Differences in the mean levels of Hsp40 and Hsp70 between BOL (Benign Oral Lesion) and OSCC (Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma) patients.

Figure 4. Patterns role of Hsp70 in the pathogenesis events Benign Oral Lesion (BOL) patients (benign) and Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OSCC), namely BOL:OSCC = 1:6.7.

example is: cochaperone nucleotide-exchange factor BCell lymphoma athanogene 2-associated 1 (BAG-1) facilitates ATP-ADP cycle and assists with Hsp70 protein folding. Chaperone-cochaperone complex helps newly translated protein folding and fold to make a return to the denatured protein, or protein molecules to steer proteases to degrade if the protein cannot be saved [22-24]. Distinguishing functional domains of molecular chaperones can recognize a polypeptide chain that need help, interconnected and form a complex folding chaperone and perform again, or associated with another chaperone complex, by a machine degradating protein, such as ubiquitin-proteasome system to degrade. Some chaperones bind ATP and master ATPase activity [24-29].

Team chaperones are major cell chaperone machinery that consist of: Hsp70, Hsp40, and the nucleotide-exchange factor, complex chaperonin-containing tailless complex polypeptide 1 (TCP-1) consisting of eight subunits (also called CCT; chaperonin is a subtype chaperones), prefolding chaperones consists of five subunits, which form a small Hsp chaperones multimers of various sizes, and Cpn60-Cpn10 complex (which CPN is also known as chaperonin Hsp60 Hsp10). Cpn60-Cpn10 complex is located in the mitochondria, while the other is in the cytosol, nucleus, or other compartments in the cell [23,26,30-33].

Several studies support the existence of a cotranslational interaction between molecular chaperones with newly translated proteins, particularly Hsp70 and Hsp40 possible. Interaction of Hsp40 (DnaJ) with newly translated protein is very short of 55 residues have been reported in animals fireflies, the luciferase and chloramphenicol acetyltransferase [9]. The study also showed that protein folding and translocation to the mitochondria continue to require Hsp70 (DnaK), Hsp40 (DnaJ), and Hsp20-30 (GrpE), and leads to a hypothesis, that the Hsp40 (DnaJ) proteins protect the newly translated from aggregation. Heat shock protein 70 function controls the folding of the polypeptide chains or domains that have been synthesized polypeptide intact. Heat shock protein 70 and Hsp40 proteins associated with newly translated in the ribosome show as a translator, while Hsp20-30, albeit temporarily associated with proteins that have been translated are not found in the ribosome. Confirmed that Hsp70 and Hsp40 act at step folding of a protein, whereas Hsp20-30 act at later steps [6,34,35].

Stressor is a general term that may result as a positive modulator (stimulator) and negative (suppressor). The state called the negative consequences of stressors and distress proved a role in the events pain [17,36-38]. The situation could lead to a state of distress and continues patobiologis event of an illness, such as protein conformational disorders (PCDs) including cancer [15,39]. Biological stressors associated with cancer include the human papilloma virus (HPV) [12,40-42]. In the state of distress caused by HPV, then the cells will express the heat shock protein (Hsp) for the purpose of homeostasis, which makes equilibrium, the process of apoptosis and cell proliferation, but a lot of the fact that the balance between apoptosis and cell proliferation are not always successful, continues even develop into cancer [12,43].

Stress causes cells to denature the protein so the protein was lost native functional conformation, which becomes folded (unfolded). Chaperones assist protein folding repair and restore the original function. If the stressor can’t be controlled by anti-stress protein, the mechanism of protein folding back by chaperones, the intracellular protein folding and it became one of the insoluble and tend to do the wrong couple, so it continues to form inclusion bodies. The development led to the inclusion bodies pathobiologis as shown in Parkinson’s diseases, Alzheimer's and Huntington’s diseases. The formation of these bodies inclusion can still continue even if the stressor is gone [44-49]. Denaturation and aggregation must be prevented with the help of molecular chaperones [17].

Pain triggered by distress is recorded in 70% - 80% of all patients visiting doctors [12,17]. Biological stressors likely have a major role in the pathogenesis of cancer incidence, such as carcinoma. However, results of studies on carcinoma are varied, from no relationship to very strongly related [41,38]. Human papilloma virus is a biological stressor known as risk factors closely associated with cancers of the oral cavity [42,50]. Cancer begins with a scene of expression imbalance, which has specific role in apoptosis and cell proliferation, and DNA repair [51]. Apoptosis and cell proliferation is a common phenomenon that usually occurs to help reconstruction in multicellular organisms [52]. Failure of apoptosis regulation is the key principle for the success of carcinogenesis, i.e. inhibition of apoptosis events [1,53]. Increased cell proliferation is also a key to the success of carcinogenesis [54]. Research in the last decade reported that allegedly increased expression of Hsp role in fault denatured protein folding of newly translated protein and, as a result of HPV stressor, the protein does not function normally [12-16]. Note that support the opinion expressed above, that Hsp molecules are called molecular chaperones and play a role in homeostasis, allegedly facilitating the flow of apoptosis and cell proliferation and contribute to the principal flow direction changes cancer at the molecular level [1]. Heat shock protein is known to continuously and comprehensively express in most normal tissues and cancer [16] and has implications for many protein interactions, such as folding, translocation and prevent improper aggregation and degradation. Many errors of proteins folding are implicated in functions that lead and contribute to the pathogenesis of pain, including cancer incidence [17,18]. All were expected to explain the role of Hsp40 and Hsp70 in the pathogenesis events of OSCC patients with stressor like HPV through inhibition of apoptosis and increased cell proliferation

5. Conclusion

This study confirms that OSCC patients have increased Hsp70 levels, so it is possible that something is going wrong in protein folding. Error leads the protein folding not to function normally and results in a new homeostasis event or inhibition of apoptosis and increased cell proliferation that triggers carcinogenesis. Hsp40 acts as cochaperones.

6. Acknowledgments

We thank to Inter University Center (IUC) of Biotechnology, Gadjah Mada University Yogyakarta, Airlangga University Surabaya and Dr. Muwardi Hospital Surakarta for their laboratory facilities. We also thank to Ambar Mudigdo, JB Dalono, Retno Puji Rahayu, Joko Agus Purwanto, Ni Nyoman Tri Puspaningsih, Kuntoro, Harjanto JM

REFERENCES

- M. P. Mayer and B. Bukau, “Hsp70 Chaperones: Cellular Functions and Molecular Mechanism,” Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, Vol. 62, No. 6, 2005, pp. 670-684. doi:10.1007/s00018-004-4464-6

- J. P. Hendrick and F. U. Hartl, “The Role of Molecular Chaperones in Protein Folding,” FASEB Journal, Vol. 9, No. 15, 1995, pp. 1559-1569.

- M. P. Goetz, D. O. Toft, M. M. Ames and C. Erlichman, “The Hsp90 Chaperone Complex as a Novel Target for Cancer Therapy,” Annals of Oncology, Vol. 14, No. 8, 2003, pp. 1169-1176. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdg316

- C. Spiess, A. S. Meyer, S. Reissmann and J. Frydman, “Mechanism of the Eukaryotic Chaperonin: Protein Folding in the Chamber of Secrets,” Trends in Cell Biology, Vol. 14, No. 11, 2004, pp. 598-604. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2004.09.015

- R. J. Nelson, T. Ziegelhoffer, C. Nicolet, M. WernerWashburne and E. A. Craig, “The Translation Machinery and 70 kd Heat Shock Protein Cooperate in Protein Synthesis,” Cell, Vol. 71, No. 1, 1992, pp. 97-105. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(92)90269-I

- J. Frydman, E. Nimmesgern, K. Ohtsuka and F. U. Hartl, “Folding of Nascent Polypeptide Chains in a High Molecular Mass Assembly with Molecular Chaperones,” Nature, Vol. 370, 1994, pp. 111-117. doi:10.1038/370111a0

- R. J. Schumacher, R. Hurst, W. P. Sullivan, N. J. Mc Mahon, D. O. Toft and R. L. Matts, “ATP-Dependent Chaperoning Activity of Reticulocyte Lysate,” The Journal of Biological Chemistry, Vol. 269, No. 13, 1994, pp. 9493-9499.

- J. P. Hendrick and F. U. Hartl, “The Role of Molecular Chaperones in Protein Folding,” FASEB Journal, Vol. 9, No. 15, 1995, pp. 1559-1569.

- J. P. Hendrick, T. Langer, T. A. Davis, F. U. Hartl and M. Wiedmann, “Control of Folding and Membrane Translocation by Binding of the Chaperone DnaJ to Nascent Polypeptides,” Proceedings of the Natinal Academy of Sciences of the USA, Vol. 90, No. 21, pp. 10216-10220. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.21.10216

- A. Smith, “Protein Misfolding,” Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, Vol. 426, No. 6968, 2003, pp. 883-909.

- A. H. Lund and M. van Lohuizen, “Epigenetics and Cancer,” Genes & Development, Vol. 18, No. 19, 2004, p. 231535.

- T. J. Hubbard and C. Sander, “The Role of Heat-Shock and Chaperone Proteins in Protein Folding: Possible Molecular Mechanisms,” Protein Engineering, Vol. 4, No. 7, 1991, pp. 711-717.

- H. M. Beere, B. B. Wolf, K. Cain, D. D. Mosser, A. Mahboubi, T. Kuwana, P. Tailor, R. I. Morimoto, G. M. Cohen and D. R. Green, “Heat-Shock Protein 70 Inhibits Apoptosis by Preventing Recruitment of Procaspase-9 to the Apaf1apoptosome,” Nature Cell Biology, Vol. 2, 2000, pp. 469-475. doi:10.1038/35019501

- H. M. Beere, “The Stress of Dying: The Role of Heat Shock Proteins in the Regulation of Apoptosis,” Journal of Cell Science, Vol. 117, No. 13, 2004, pp. 2641-2651. doi:10.1242/jcs.01284

- S. Arawaka, Y. Machiya and T. Kato, “Heat Shock Proteins as Suppressors of Accumulation of Toxic Prefibrillar Intermediates and Misfolded Proteins in Neurodegenerative Diseases,” Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, Vol. 11, No. 2, 2010, pp. 158-166.

- S. A. Houck, S. Singh and D. M. Cyr, “Cellular Responses to Misfolded Proteins and Protein Aggregates,” Methods in Molecular Biology, Vol. 832, 2012, pp. 455-461. doi:10.1007/978-1-61779-474-2_32

- J. L. Alberto, M. D. Macario and E. C. de Macario, “Sick Chaperones, Cellular Stress, and Disease,” The New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 353, No. 14, 2005, pp. 1489-1501.

- M. M. M. Wilhelmus, R. M. W. de Waal and M. M. Verbeek, “Heat Shock Proteins and Amateur Chaperones in Amyloid-Beta Accumulation and Clearance in Alzheimer’s Disease,” Molecular Neurobiology, Vol. 35, No. 3, 2007, pp. 203-216.

- H. L. Schmits, “Species Diagnostics Protocols: PCR and Other Nucleic Acid Methods,” In: J. P. C. Humana, Methods in Molecular Biology, Press Inc., Totowa, 1994.

- T. Hessel, S. P. Dhital, R. Plank and D. Dean, “Immune Response to Chlamydial 60-Kilodalton Heat Shock Protein in Tears from Nepali Trachoma Patients,” Infection and Immunity, Vol. 69, No. 8, 2001, pp. 4996-5000.

- M. F. Prummel, Y. Van Pareren, O. Barker and W. M. Wiersinga, “Anti-Heat Shock Protein (hsp)72 Antibodies Are Present in Patients with Graves’ Disease (GD) and in Smoking Control Subjects,” Clinical and Experimental Immunology, Vol. 110, No. 2, 1997, pp. 292-295.

- C. Georgopoulos and W. J. Welch, “Role of the Major Heat Shock Proteins as Molecular Chaperones,” Annual Review of Cell Biology, Vol. 9, 1993, pp. 601-634. doi:10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.003125

- K. N. Truscott, K. Brandner and N. Pfanner, “Mechanism of Protein Import into Mitochondria,” Current Biology, Vol. 13, No. 8, 2003, pp. R326-R337. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00239-2

- S. Alberti, C. Esser and J. Hohfeld, “BAG-1—A Nucleotide Exchange factor Of Hsc70 with Multiple Cellular Functions,” Cell Stress and Chaperones, Vol. 8, No. 3, 2003, pp. 225-231. doi:10.1379/1466-1268(2003)008<0225:BNEFOH>2.0.CO;2

- A. J. Caplan, “What is a Co-Chaperone?” Cell Stress and Chaperones, Vol. 8, No. 2, 2003, pp. 105-107. doi:10.1379/1466-1268(2003)008<0105:WIAC>2.0.CO;2

- J. C. Young, J. M. Barral and F. U. Hartl, “More than Folding: Localized Functions of Cytosolic Chaperones,” Trends in Biochemical Sciences, Vol. 28, No. 10, 2003, pp. 541-547. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2003.08.009

- J. C. Young, V. R. Agashe, K. Siegers and F. U. Hartl, “Pathways of Chaperone-Mediated Protein Folding in the Cytosol,” Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, Vol. 5, No. 10, 2004, pp. 781-791. doi:10.1038/nrm1492

- J. Martin, “Chaperonin Function—Effects of Crowding and Confinement,” Journal of Molecular Recognition, Vol. 17, No. 5, 2004, pp. 465-472. doi:10.1002/jmr.707

- O. O. Odunuga, V. M. Longshaw and G. L. Blatch, “Hop: More than an HSP70/Hsp90 Adaptor Protein,” BioEssays, Vol. 26, No. 10, 2004, pp. 1058-1068. doi:10.1002/bies.20107

- A. L. Fink, “Chaperone-Mediated Protein Folding,” Physiological Reviews, Vol. 79, No. 2, 1999, pp. 425-449.

- B. Kleizen and I. Braakman, “Protein Folding and Quality Control in the Endoplasmic Reticulum,” Current Opinion in Cell Biology, Vol. 16, No. 4, 2004, pp. 343-349. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2004.06.012

- A. J. L. Macario and E. C. de Macario, “The Pathology of Cellular Anti-Stress Mechanisms: A New Frontier,” Stress, Vol. 7, No. 4, 2004, pp. 243-249. doi:10.1080/10253890400019706

- A. J. L. Macario and E. C. de Macario, “Molecular Chaperones and Age-Related Degenerative Disorders,” Advances in Cell Aging and Gerontology, Vol. 7, 2001, pp. 131-162. doi:10.1016/S1566-3124(01)07018-3

- G. A. Gaitanaris, A. Vysokanov, S. C. Hung, M. E. Gottesman and A. Gragerov, “Successive Action of Escherichia coli Chaperones in Vivo,” Molecular Microbiology, Vol. 14, No. 5, 1994, pp. 861-869. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01322.x

- M. A. Petit, W. Bedale, J. Osipiuk, C. Lu, M. Rajagopalan, P. Mc Inerney, M. F. Goodman and H. Echols, Sequential Folding of UmuC by the Hsp70 and Hsp60 Chaperone Complexes of Escherichia coli,” The Journal of Biological Chemistry, Vol. 269, No. 38, 1994, pp. 23824-23829.

- A. A. Morino and D. H. Moris, “Chronic Electromagnetic Stressors in the Enviroment: A Risk Factor in Human Cancer,” Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Vol. 3, No. 2, 1985, pp. 189-219.

- P. L. Ooi and K. T. Goh, “Sick Building Syndrome: An Emerging Stress-Related Disorders,” International Journal of Epidemiology, Vol. 26, No. 6, 1997, pp. 1243- 1249.

- K. Sjövall, B. Attner, T. Lithman, D. Noreen, B. Gunnars, B. Thomé, L. Lidgren, H. Olsson and M. Englund, “Sick Leave of Spouses to Cancer Patients before and after Diagnosis,” Acta Oncologica, Vol. 49, No. 4, 2010, pp. 467-473.

- P. Leandro and C. M. Gomes, “Protein Misfolding in Conformational Disorders: Rescue of Folding Defects and Chemical Chaperoning,” Mini-Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry, Vol. 8, No. 9, 2008, pp. 901-911.

- A. Prayitno, “Cervical Cancer with Human Papilloma virus and Epstein Barr virus Positif,” Journal of Carcinogenesis, Vol. 5, 2006, p.13.

- A. K. Chaturvedi, “Beyond Cervical Cancer: Burden of Other HPV-Related Cancers among Men and Women,” The Journal of Adolescent Health, Vol. 46, No. 4S, 2010, pp. S20-S26. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.016

- A. Prayitno, “Incidence of HPV Infection in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Its Associated with the Presence of p53 and C-Myc Mutation : A Case Control Study in Muwardi Hospital Surakarta,” Indian Journal of Dental Research, Vol. 17, No. 2, 2010, pp. 48-52.

- D. R. Ciocca and S. K. Calderwood, “Heat Shock Proteins in Cancer: Diagnostic, Prognostic, Predictive, and Treatment Implications,” Cell Stress Chaperones, Vol. 10, No. 2, 2005, pp. 86-103.

- J. Klucken, Y. Shin, E. Masliah, B. T. Hyman and P. J. McLean, “HSP70 Reduces Alphasynuclein Aggregation and Toxicity,” The Journal of Biological Chemistry, Vol. 279, 2004, pp. 25497-25502. doi:10.1074/jbc.M400255200

- J. Magrane, R. C. Smith, K. Walsh and H. W. Querfurth, “Heat Shock Protein 70 Participates in the Neuroprotective Response to Intracellularly Expressed Beta-Amyloid in Neurons,” The Journal of Neuroscience, Vol. 24, No. 7, 2004, pp. 1700-1706. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4330-03.2004

- C. A. Ross and M. A. Poirier, “Protein Aggregation and Neurodegenerative Disease,” Nature Medicine, Vol. 10, 2004, pp. S10-S17. doi:10.1038/nm1066

- M. Arrasate, S. Mitra, E. S. Schweitzer, M. R. Segal and S. Finkbeiner, “Inclusion Body Formation Reduces Levels of Mutant Huntingtin and the Risk of Neuronal Death,” Nature, Vol. 431, 2004, pp. 805-810. doi:10.1038/nature02998

- M. A. Poirier, H. Jiang and C. A. Ross, “A StructureBased Analysis of Huntingtin Mutant Polyglutamine Aggregation and Toxicity: Evidence for a Compact BetaSheet Structure,” Human Molecular Genetics, Vol. 14, No. 6, 2005, pp. 765-774. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddi071

- A. J. L. Macario and E. C. de Macario, “Genetic Disorders Involving Molecularchaperone Genes: A Perspective,” Genetics in Medicine, Vol. 7, 2005, pp. 3-12. doi:10.1097/01.GIM.0000151351.11876.C3

- I. A. Ruz, D. A. Ossa, W. K. Torres, U. Kemmerling, B. A. Rojas and C. A. Martínez, “Nucleolar Organizer Regions in a Chronic Stress and Oral Cancer Model,” Oncology Letters, Vol. 3, No. 3, 2012, pp. 541-544.

- C. Bernstein, H. Bernstein, C. M. Payne and H. Garewal, “DNA Repair/Pro-Apoptotic Dual-Role Proteins in Five Major DNA Repair Pathways: Fail-Safe Protection against Carcinogenesis,” Mutation Research, Vol. 511, No. 2, 2002, pp. 145-178.

- F. Lang, M. Ritter, N. Gamper, S. Huber, S. Fillon, V. Tanneur, A. Lepple-Wienhues, I. Szabo and E. Gulbins, Cell Volume in the Regulation of Cell Proliferation and Apoptotic Cell Death,” Cell Physiology Biochemistry, Vol. 10, No. 5-6, 2000, pp. 417-428. doi:10.1159/000016367

- R. S. Fife, B. T. Rougraff, C. Proctor and G. W. Sledge Jr., “Inhibition of Proliferation and Induction of Apoptosis by Doxycycline in Cultured Human Osteosarcoma Cells,” The Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine, Vol. 130, No. 5, 1997, 530-534.

- A. P. Feinberg, R. Ohlsson and S. Henikoff, “The Epigenetic Progenitor Origin of Human Cancer,” Nature Reviews Genetics, Vol. 7, 2006, pp. 21-33.