Natural Science

Vol.6 No.5(2014), Article ID:43728,13 pages DOI:10.4236/ns.2014.65035

Epidemiological Studies on the Relationship between PTSD Symptoms and Circadian Typology and Mental/Sleep Health of Young People Who Suffered a Natural Disaster, Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake

Kai Wada1, Hiroko Kuroda1, Miyo Nakade2, Hitomi Takeuchi1, Tetsuo Harada1*

1Laboratory of Environmental Physiology, Graduate School of Integrated Arts and Sciences, Kochi University, Kochi, Japan

2Department of Nutritional Management, Faculty of Health and Nutrition, Tokai-Gakuen University, Miyoshi, Japan

Email: *haratets@kochi-u.ac.jp

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 27 December 2013; revised 27 January 2014; accepted 4 February 2014

ABSTRACT

This study aims, first, to determine the relationship between Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and current circadian typology and sleep habits of adults who experienced the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake in their childhood in January 1995. An integrated questionnaire was administered to 275 university students (females: 173, males: 93, unknown: 9) aged 19 - 37 (mean age: 21.9 years) in Hyogo Prefecture, Japan. The questionnaire consisted of basic questions about attributes, questions on sleep habits and sleep quality (Monroe’s sleep quality index), the Torsvall-Åkerstedt Diurnal Type Scale and the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) to obtain PTSD scores. Participants who scored 25 or more in the IES-R were placed in a high-traumatic group (HTG) and those who scored less than 25 were placed in a low-traumatic group (LTG). HTG participants exhibited significantly worse sleep quality than LTG participants (p < 0.001). Although there was no significant difference in sleep latency (p > 0.05), HTG participants woke more frequently during sleep (p < 0.001) and had more difficulty falling asleep (p = 0.001) than LHG participants. Significantly more LTG participants fell asleep easily and slept deeply than HTG participants (p = 0.005, p = 0.011). Only among females, HTG participants were more evening-typed than LTG participants (p = 0.035). These results suggest that people who suffered a disaster in childhood and currently have PTSD have difficulty achieving high sleep quality. Evening-type lifestyles may reinforce the symptoms of PTSD. The study aims, second, to examine the effects of intervention for one month using a leaflet to promote the morning-typed life for persons who suffered natural disaster entitled “Go to bed early, Get up early and Do not forget to have a breakfast for getting three benefits!”. Only one person was over the cutoff point (between 24 and 25) before intervention. This high-traumatic person’s comprehensive sleep health tended to be improved through the intervention (p = 0.052). Such intervention to improve their quality of sleep and promote a morning-typed lifestyle may be an effective way to reduce PTSD symptoms.

Keywords:Natural Disasters; Victims; PTSD; Sleep Quality; Circadian Typology

1. Introduction

1.1. Disasters and PTSD

On 17th January 1995, the Great Hanshin-Awaji earthquake with a magnitude of 7.2 as the Richter scale attacked Hanshin-Awaji area in Japan. The earthquake killed 6434 people [1] . Many studies investigating the psychological states of natural disaster victims, especially earthquakes such as in Italy [2] , Armenia [3] , and China [4] , have been demonstrated. Kato et al. [5] assessed the frequency of short-term, post-traumatic symptoms among survivors of the Hanshin-Awaji earthquake using the Post-Traumatic Symptom Scale. This paper reported that subjects experienced sleep disturbances, depression, hypersensitivity, and irritability during the third week after the earthquake.

Three and half years after a severe earthquake (7.3 on the Richter scale) in Taiwan, the estimated rate of survivors with posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) was 23.8% and 4.4%, respectively, and PTSS scores were highly correlated with QOL scores (less severe symptoms with higher QOL) [6] . Even 4 years after the Parnitha earthquake in Greece, 22% of survivors reported subjective distress and intense fear during the earthquake, and participation in rescue operations positively correlated with greater post-earthquake psychological stress [7] . The psychological consequence of earthquakes may be serious and long-lasting even when the magnitude of the earthquake is moderate [7] .

1.2. Circadian Typology and Sleep Habits

The ongoing 24-hour commercialization society accelerated shifting to evening-typed life for many people [8] . As a result, 24-hour commercialization society may reduce the amplitudes of environmental daily cycles of light, social activities, and food intake. Persistent lower amplitudes of several zeitgebers may induce an inner-desynchronized protocol between the main clock, which drives the autonomous nervous system, and the slave clock, which controls the sleep-wake cycle (Double-oscillations theory [9] ). So, evening-typed diurnal rhythms, which are linked to the shortage of sleep due to late bedtimes and also poor quality of sleep [10] -[15] , may lead to lower moods and higher levels of irritation than morning-typed ones [16] .

1.3. PTSD, Sleep Disturbance and Circadian Typology

A previous study to assess the quality of sleep and its architecture in injured victims of traffic accidents one year after the accident found that the problem in PTSD is mainly sleep misperception rather than actual sleep alteration [17] . On the other hand, Wang et al. [18] reported that sleep disturbance is one of 4 factors indicating PTSD symptoms as assessed by the Impact Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) and the main symptom exhibited in PTSD. Some studies were consistent [19] [20] .

Another previous study aimed to determine the relationship between Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and current circadian typology and sleep habits of adults who experienced the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake after becoming adults [21] . Kuroda et al. [21] found that people who damaged strongly from a disaster and who currently show severe PTSD symptoms are more evening-typed and have a lower quality of sleep. However, whether PTSD symptoms of young people who suffered the Hanshin-Awaji earthquake in childhood can be reduced by the morning-typed life was remained to be studied.

This study aims, first, to determine the relationship between Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and current circadian typology and sleep habits of people who experienced the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake in their childhood in January 1995. The second aim is to evaluate the effects of an intervention on sleep and mental health including PTSD symptoms of such young participants using a leaflet on “Go to bed early, Get up early and Do not forget to have a breakfast” and a sleep diary.

2. Participants and Methods

2.1. Questionnaire Study

An integrated questionnaire was administered to 275 people aged 19 - 37 years old (mean age: 21.9 years) in Hyogo Prefecture (35˚N), Japan in March 2012, with responses received from 275 people (females: 173, males: 93, unknown: 9) which were all available for analysis. The questionnaire consisted of basic questions about attributes such as age and sex, questions on sleep habits and sleep quality, the Torsvall-Åkerstedt Diurnal Type Scale [22] and a Japanese version [23] of the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) which has been usually used as PTSD scores [24] composed of 22 questions, 8 questions related to “intrusion”, 6 on “hyper-arousal” and 8 on “avoidance-numbing”. The original questions on sleep habits which Harada et al. [25] originally constructed have been used in several papers [26] -[31] .

2.1.1. Statistical Analysis

The data was statistically analyzed using Mann-Whitney U-tests and Pearson’s correlation analysis with SPSS 20.0 statistical software. Diurnal Type scale scores were expressed as means plus or minus the standard deviation (Mean ± SD).

2.1.2. Criterion for High and Low Damage Groups

Participants were divided into a High Damage Group (HDG) and a Low Damage Group (LDG) based on the IES-R scores. Participants who scored 25 or more in the IES-R were placed in HDG and those who scored less than 25 were placed in LDG.

2.2. Intervention Study

An intervention program using a leaflet to promote the morning-typed life for persons who suffered natural disaster, entitled “Go to bed early, Get up early and Do not forget to have a breakfast, for getting three benefits!”. Participants were asked to follow the 5 contents of intervention, included in the leaflet.

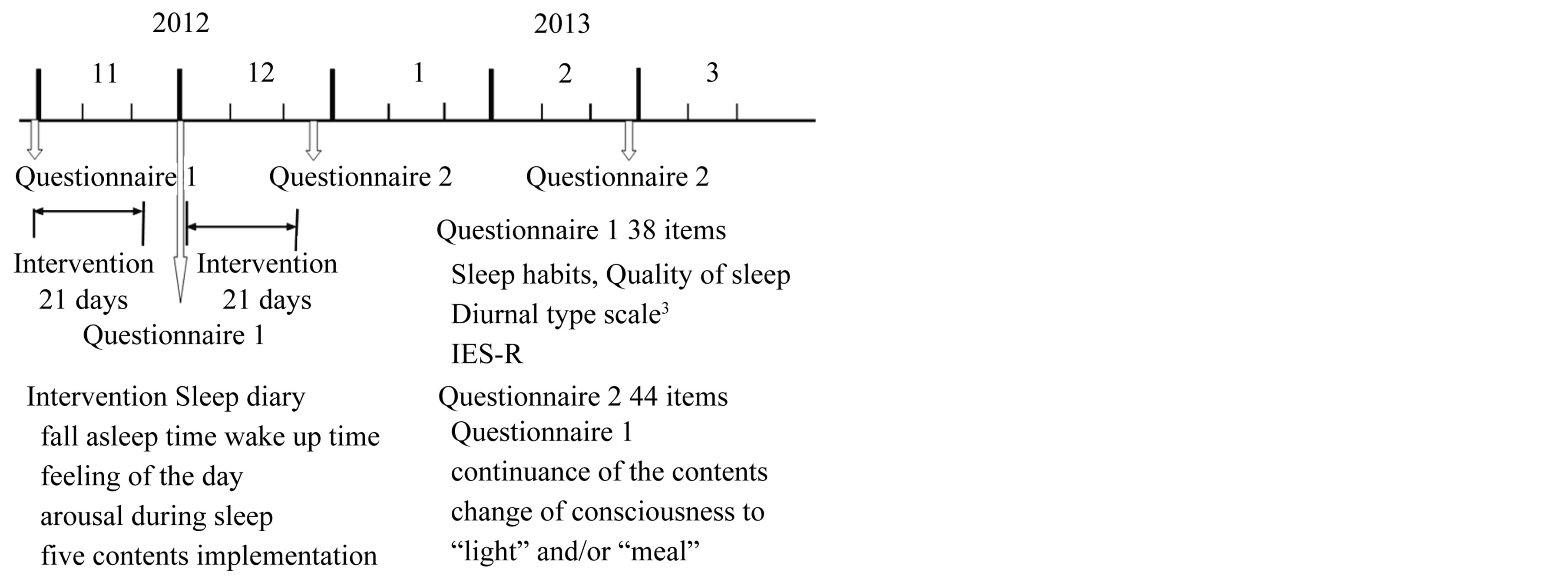

The intervention program was administered to 96 participants belonging to school of nursing. To estimate the effects of the one month intervention, integrated questionnaires were administered to all participants two times: before the start of the intervention period and one or two months after the end of the intervention period (See legend of Figure 1). Ninety-four of 96 (98%) participants answered the first questionnaire and 72 of 94 (77%) kept sleep diaries for 21 days and answered the second questionnaire. Participants aged 38 or more were eliminated. Finally 66 participants (male: 7, female: 57, unclear: 2, 19 - 37 years old, average age: 22.73) were used for analysis.

All participants were asked to keep a sleep diary throughout the 21 days of the intervention period, which was in November or December of 2012. To counterbalance the effect of the day length, two intervention periods were set across the winter solstice. Twenty-three subjects participated in the intervention in November and 43 participants did in December. The sleep diary consisted of questions on sleep habits (including falling asleep time and awakening time), physical condition, mood on awakening, awakening frequency during night sleep, and the implementation status of 5 contents of intervention (Table 1).

Participants marked their implementation status every day. For the 1st and 3rd contents, they marked circle or × for “Yes” or “No” and answered how many minutes they had been exposed to sunlight. For the 2nd content, they chose one from four choices for breakfast contents (a double circles: they had nutritionally well balanced breakfast; a circle: they had breakfast including staple diet; a triangle: they had something; a ×-marking: they had nothing). For the 4th content, they marked a circle when they had not watched the TV program. If they had watched it on TV, they did a ×-marking and filled how many minutes they had watched. For the 5th content, they filled how many hours they had stayed under fluorescent light.

For the statistical analysis, the “implementation score” was calculated. A circle of the 1st, 3rd, and 4th contents

Figure 1. Schedule of the intervention study.

Table 1. 5 contents of intervention in the leaflet.

meant 1 point and a ×-mark was 0 point. A double circle of the 2nd content was 1 point, a circle was 0.67 points, a triangle was 0.33 points, and a ×-mark did 0 points. On the 5th content, “0 hour” converted to 1 point and “the maximum hours” among all participants each day converted to 0 point. The other hours were rationally converted to the mark distributed from 0 and 1 points, in each day.

The 21-day-long intervention period was divided into 3 parts (FWP: First week period, MWP: Middle week period, LWP: Last week period). The “high implementation group (HIG)” was defined as 50% participants who marked higher implementation scores in each or all of 5 contents. The other 50% participants group was defined as “the low implementation group (LIG)”.

The questionnaire administered before the intervention consisted of basic questions about attributes such as age and sex, the diurnal-type scale constructed by Torsvall and Åkerstedt [22] , questions on sleep habits, quality of sleep, and a Japanese version [23] of the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) which had been usually used as PTSD scores [24] composed of 22 questions, 8 questions related to “intrusion”, 6 on “hyper-arousal” and 8 on “avoidance-numbing”. One or two months after the intervention period, the second questionnaire was administered once which consisted of questions on continuous implementation of the 5 intervention-contents and questions on the change in the consciousness to “light” and “meal” in addition to all contents of the first questionnaire. The original questions on sleep habits which Harada et al. [25] originally constructed have been used in several papers [26] -[31] .

The software used for statistical analysis was SPSS 20.0 J for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). χ2-test was used for categorized variables and Mann-Whitney U-tests was used for ranked variables. Pearson’s correlation analysis was performed to test the relationship between two numerical variables.

2.3. Ethic Issue

The study followed the guidelines established by the Chronobiology International Journal for the conduct of research on human subjects [32] . Before administrating the questionnaires, each participant was given a written explanation that detailed the concepts and purposes of the study and stated that their answers would be used only for academic purposes. After the above explanation, all participants agreed completely with the proposal. The study was also permitted by the ethic committee in the Laboratory of Environmental Physiology, Graduate School of Integrated Arts and Sciences, Kochi University which carried out an ethical inspection of the contents of the questionnaire.

3. Results

3.1. Questionnaire Study

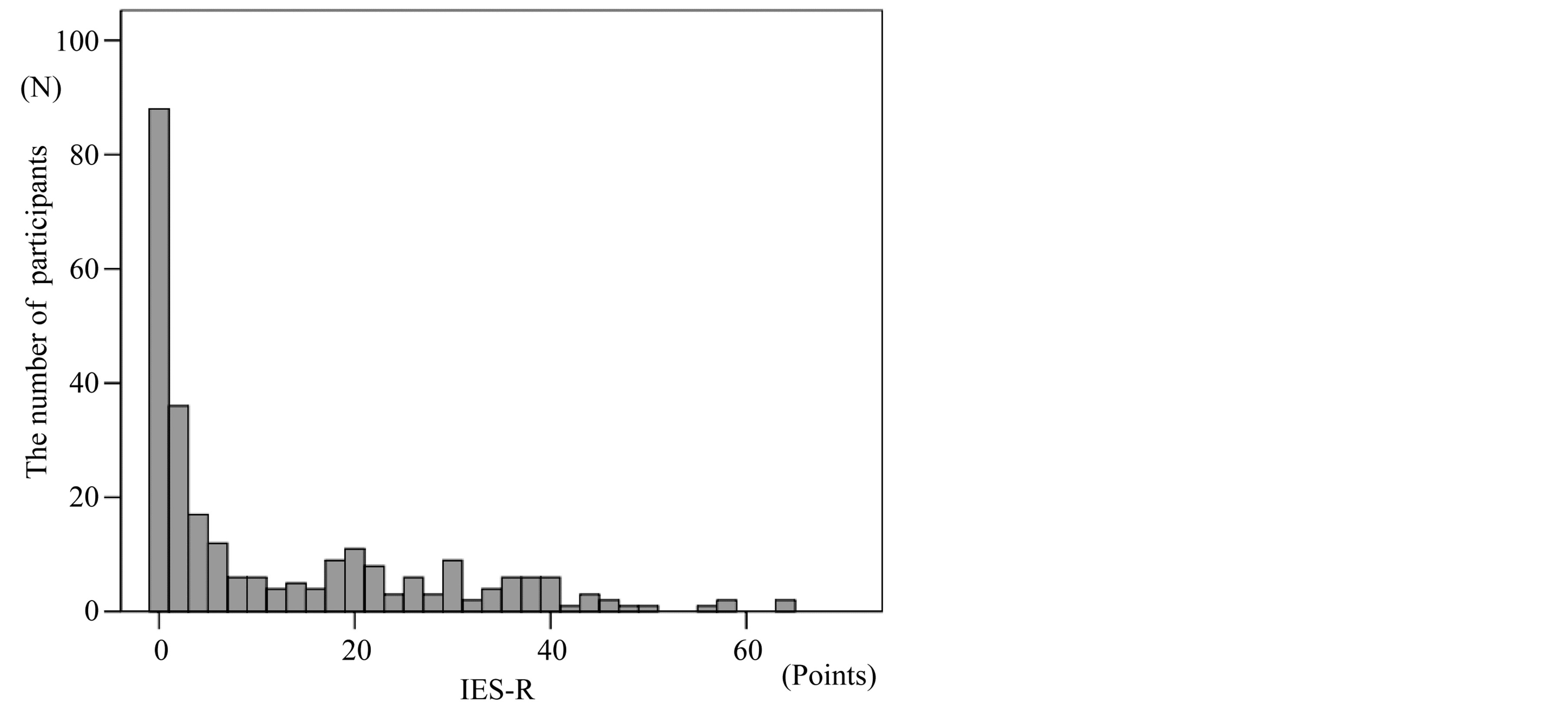

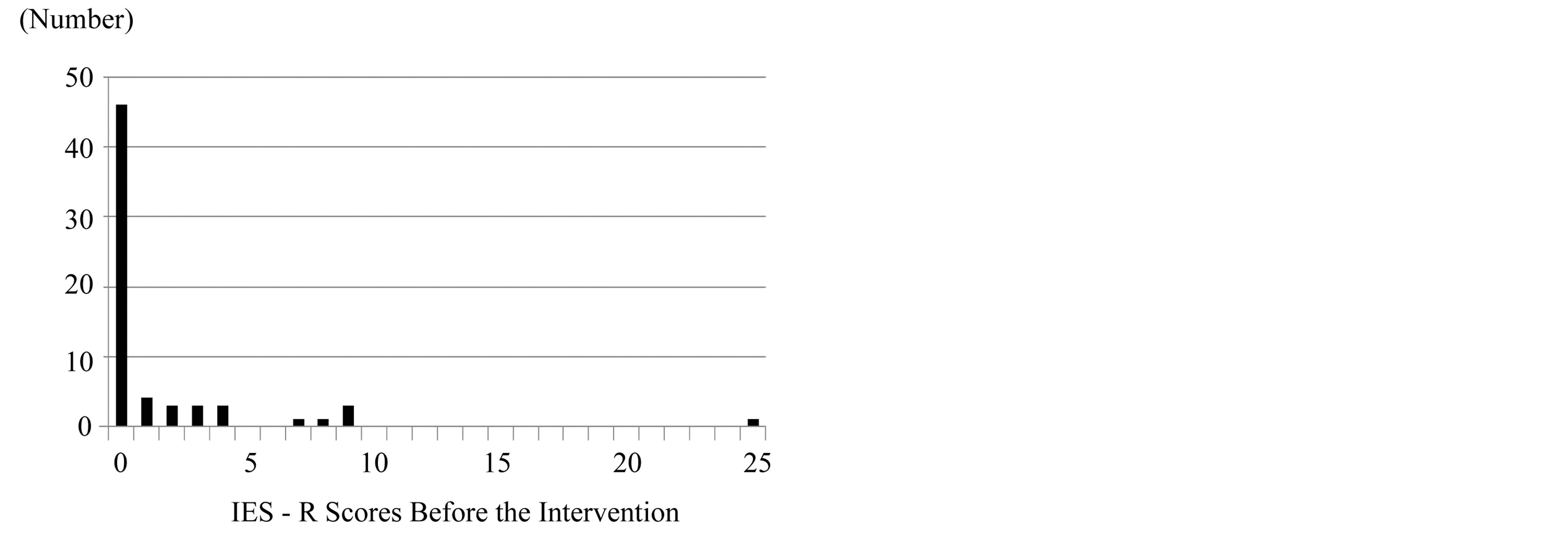

55 participants (20.8%) scored 25 or more can be decided to be the persons who have PTSD symptoms (Figure 2). There is no significant difference of bedtime, wake-up time, and sleep duration in weekday between HDG (High Damage Group) and LDG (Low Damage Group).

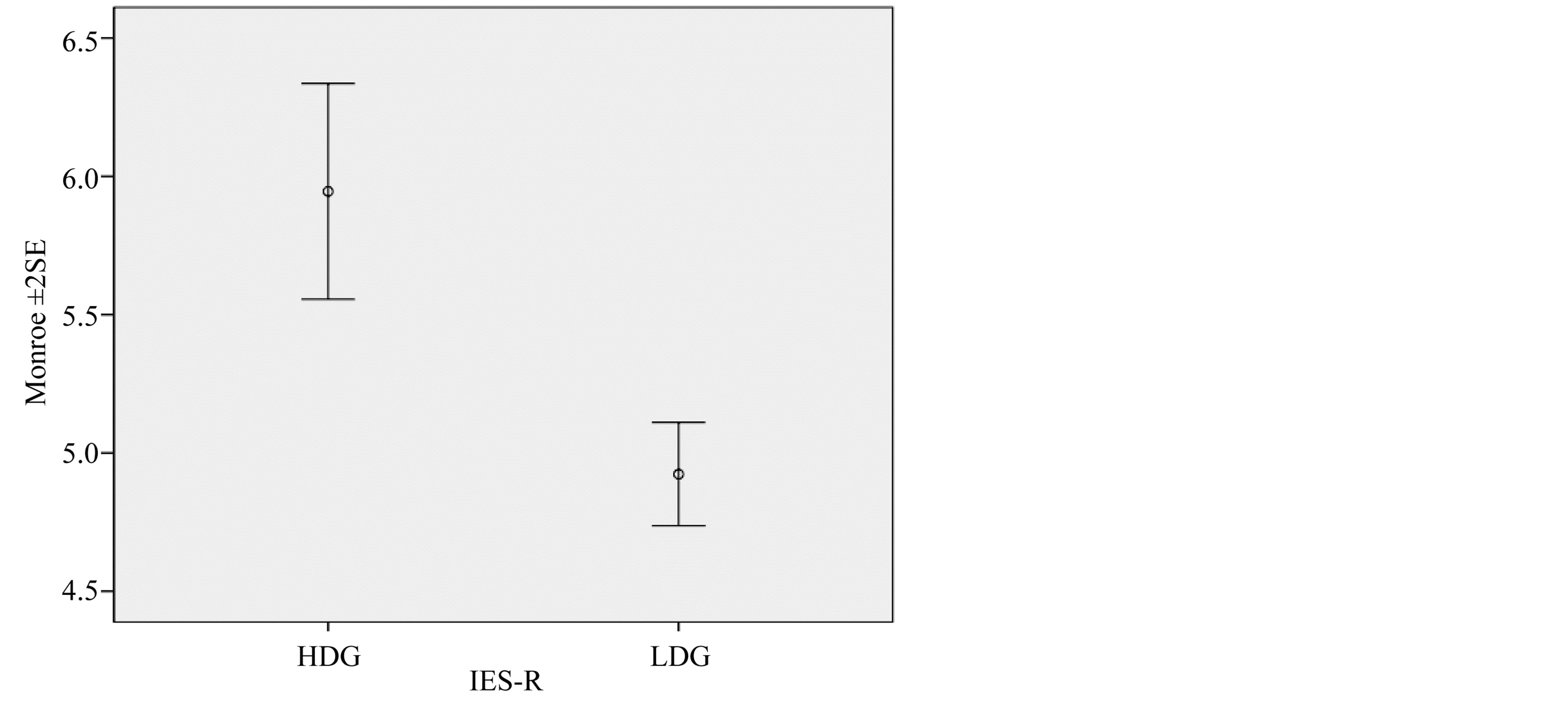

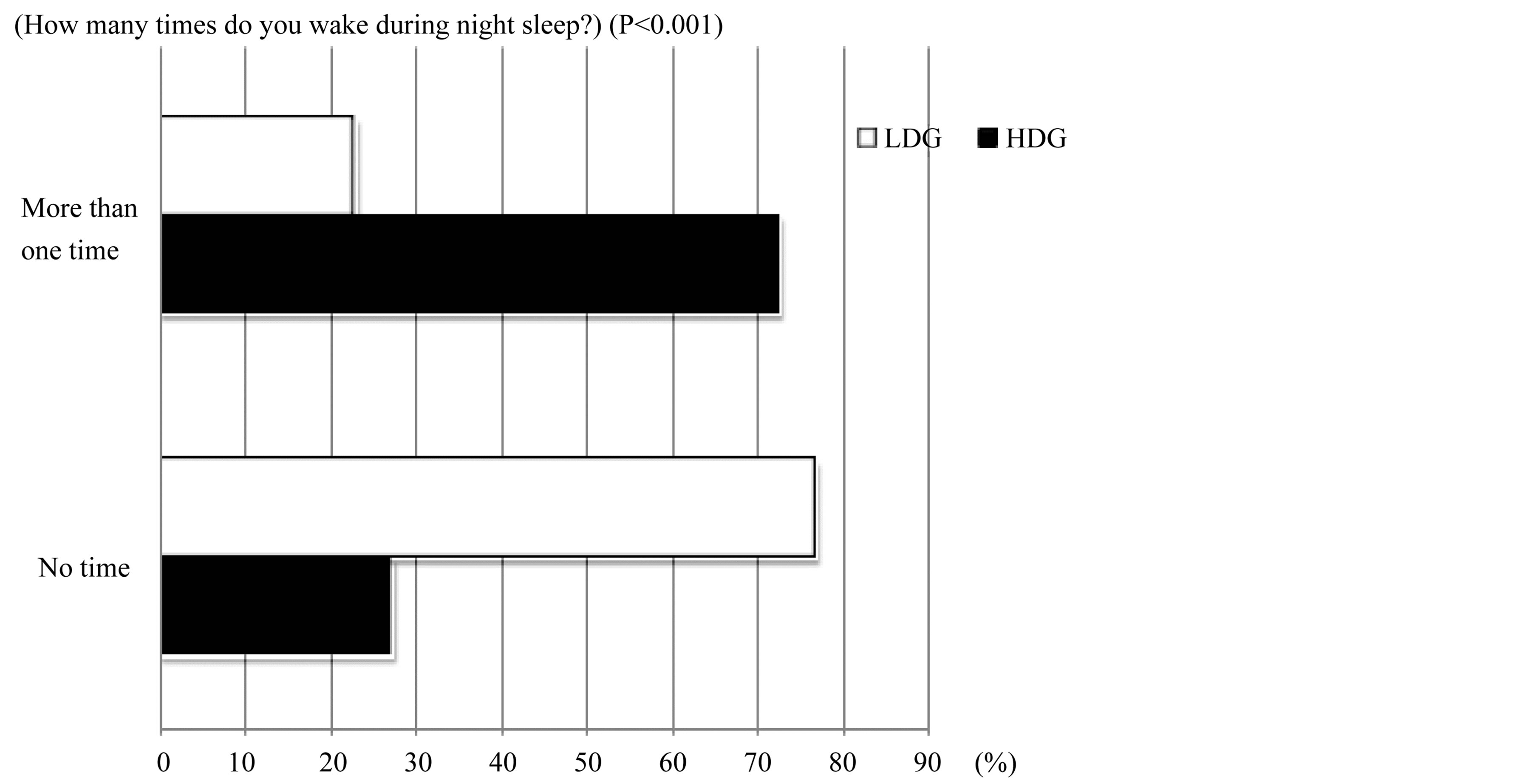

HDG participants exhibited significantly worse sleep quality than LDG participants (Mann-Whitney U-test: Z = −4.637, p < 0.001) (Figure 3). There was no significant difference in sleep latency (p > 0.05) (χ2 test: χ2-value = 0.481, df = 2, p = 0.786). HDG participants woke more frequently during sleep (Figure 4) and had more difficulty in falling asleep than LDG participants (woken during sleep: χ2-value = 48.517, df = 1, p < 0.001, difficulty in falling asleep: χ2-value = 13.378, df = 2, p = 0.001).

Figure 2. 55 participants (20.8%) scored 25 or more on IES-R. It can be decided to be the persons who have PTSD symptoms.

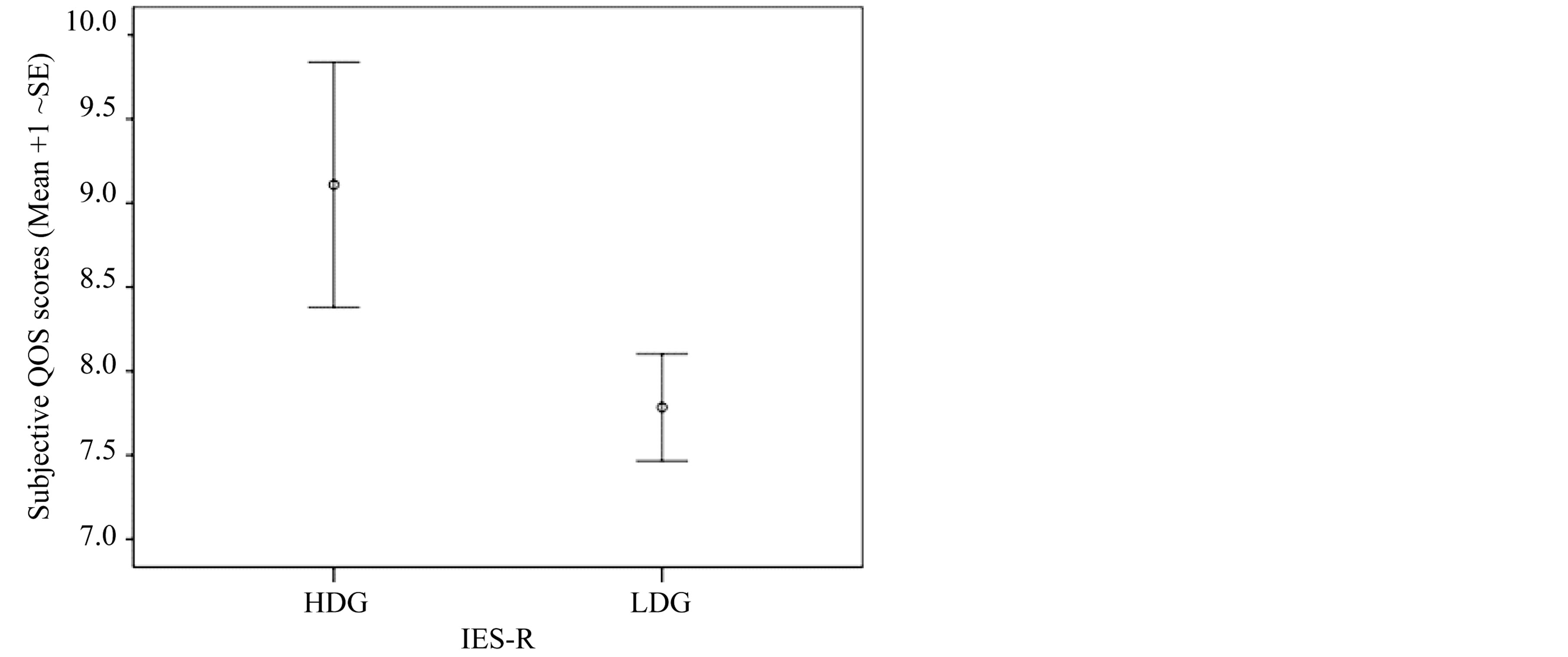

Figure 3. Comparison of current (March 2012) PTSD scores of participants of a High Damage Group (HDG) and a Low Damage Group (LDG) of the Hanshin-Awaji Great Earthquake (Jan 1995). HDG participants exhibited significantly worse sleep quality than LDG participants (Mann-Whitney U-test: Z = −4.637, p < 0.001).

Figure 4. Comparison of frequency of waking during sleep of between High Damage Group (HDG) and Low Damage Group (LDG). HDG participants woke more frequently during sleep than LDG participants (χ2 test: χ2-value = 48.517, df = 1, p < 0.001).

HDG participants exhibited significantly worse subjective sleep quality than LDG participants (Mann-Whit- ney U-test: z = −3.348, p = 0.001) (Figure 5). LDG participants fell asleep easily and slept deeply with higher frequency than HDG participants (p = 0.005, p = 0.011), although there was no difference in mood at awakening in the morning between the two groups (p > 0.05).

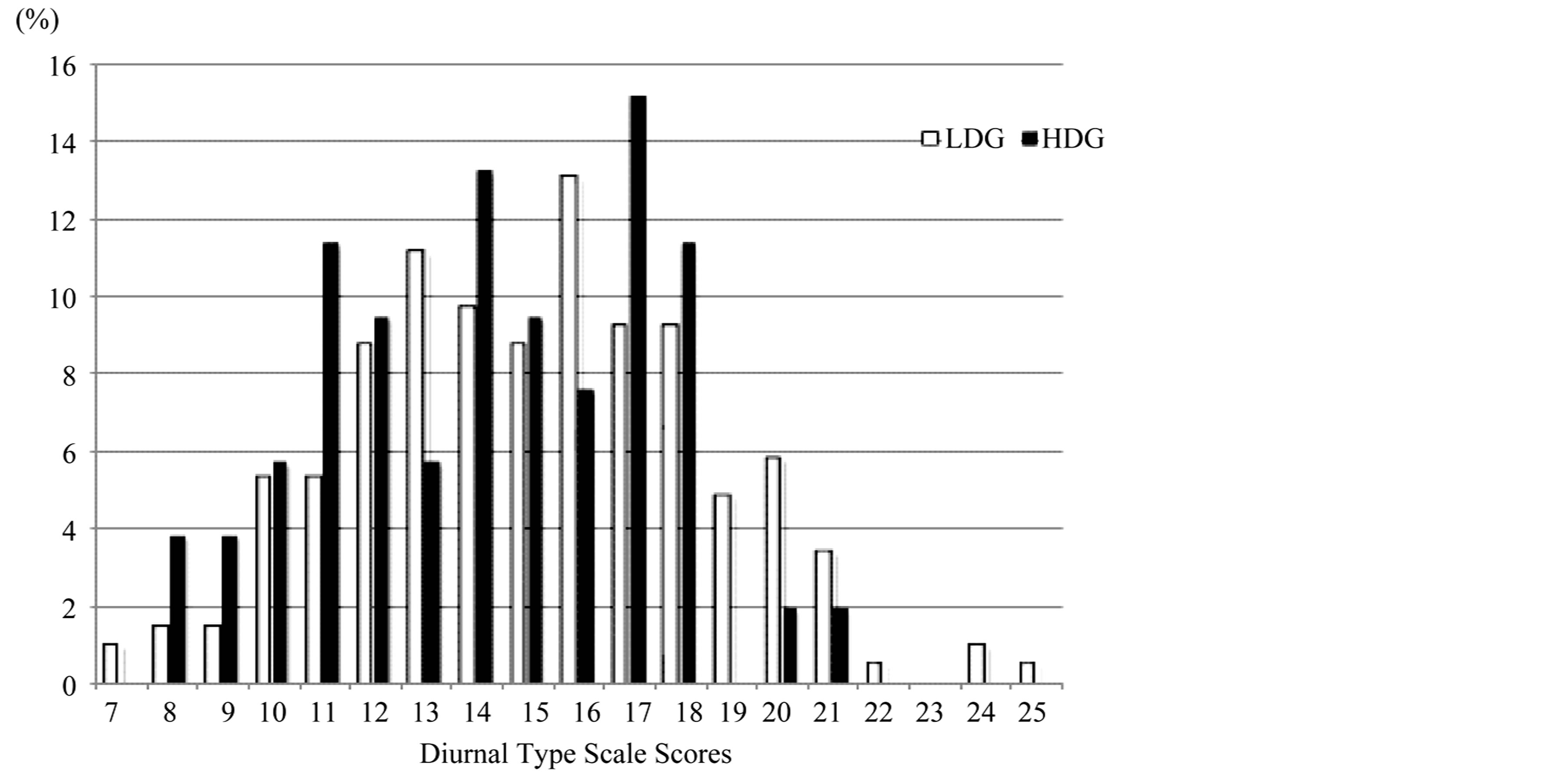

LDG participants tended to be more morning-typed than HDG participants (HDG: 14.17, LDG: 15.12, z = 1.659, p = 0.097) (Figure 6). Despite of degree of PTSD, significant positive correlation was shown between morning-typology and high sleep quality (HDG: DTS versus Monroe r = −0.420, p = 0.002, DTS versus Subjective QOS r = −0.580, p < 0.001; LDG: DTS versus Monroe r = −0.304, p < 0.001, ME versus Subjective QOS r = −0.359, p < 0.001).

Significant relationship of Diurnal Type Scores (DTS) didn’t appear to the IES-R score (ANOVA Variable factor: DTS score, p = 0.710), while that of Monroe’s QOS did so (Higher quality of sleep with lower IES-R score; ANOVA Variable factor: Monroe, p < 0.001).

3.2. Intervention Study

Only 1 person was over the cutoff point (between 24 and 25) before intervention (Figure 7). This high-traumatic person’s comprehensive sleep health tended to be improved through the intervention (Wilcoxon test: z = 1.941, p = 0.052) (Table 2).

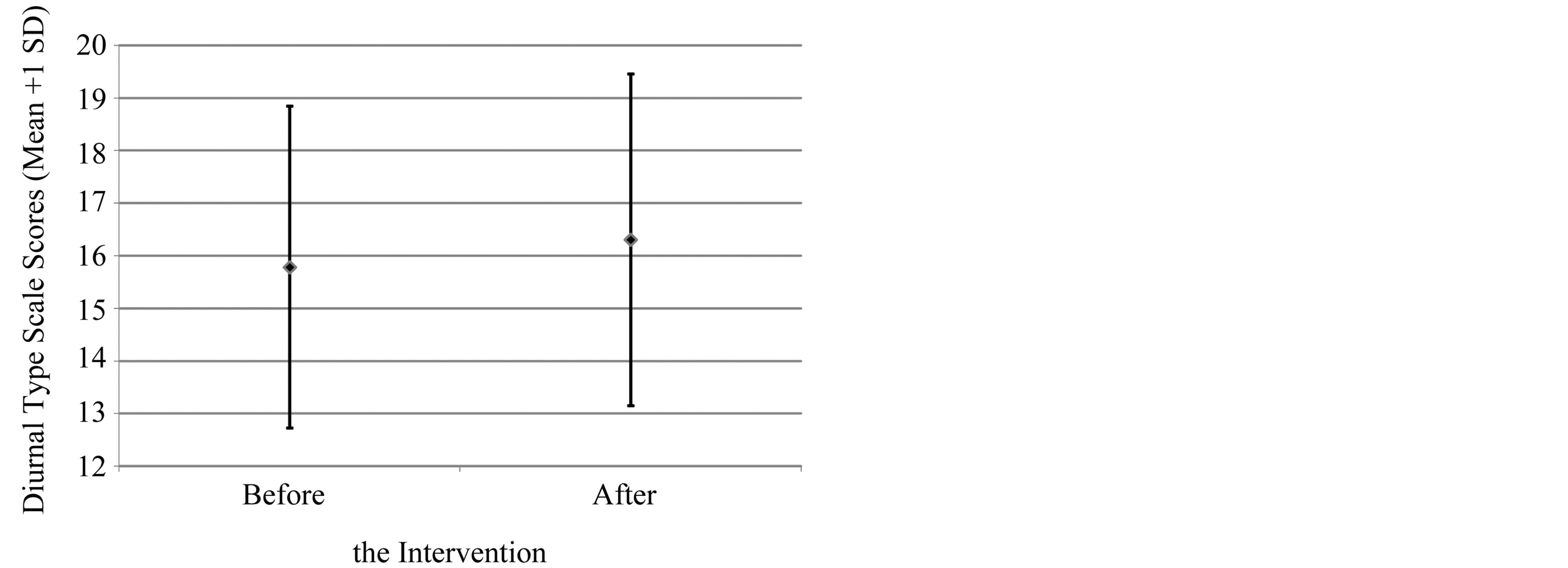

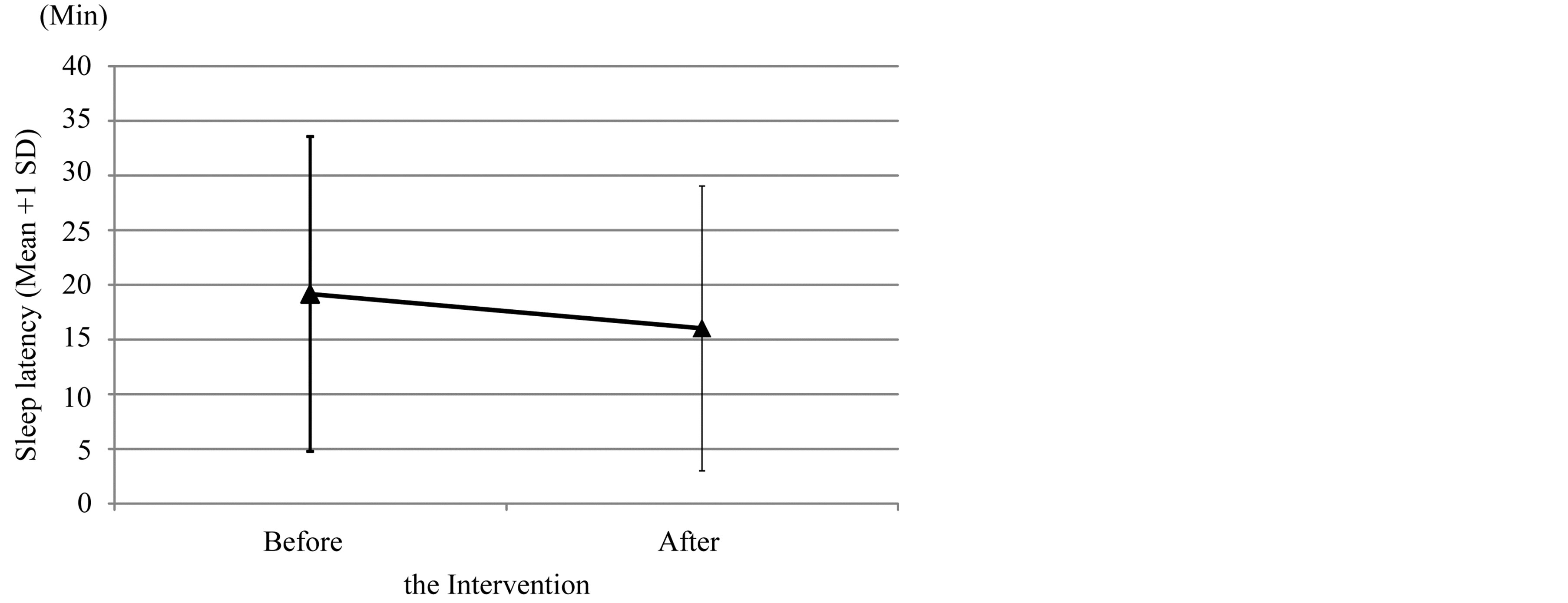

The others’ (non high-traumatic persons) diurnal type scale before intervention was significantly lower (evening-type) than that after intervention (Wilcoxon test: z = 2.004, p = 0.045) (Figure 8). Sleep latency of the others was significantly shortened through the intervention (z = −2.004, p = 0.045) (Figure 9).

The wake-up time of the high implementation group on the 2nd content (Protein rich food taken at breakfast) tended to become earlier than that of the low implementation group (Mann-Whitney U-test: z = 1.807, p = 0.071). Monroe’s sleep quality index in the high implementation group on the 3rd content (Exposed to sunlight after breakfast) was significantly improved (z = 2.540, p = 0.011) and their sleep latency tended to be shorten than those of the low implementation group (z = 1.902, p = 0.057). Participants in the high implementation group on the 4th content (Cut back on the time to watch TV at night) significantly shifted morning typed than those in the low implementation group (z = −2.518, p = 0.012). Subjective sleep quality index of the high implementation group of the 5th content (Cut back on the time to be exposed to fluorescent light at night) was significantly more improved than that of the low implementation group (z = 2.159, p = 0.031) (Table 3).

Figure 5. Comparison of subjective quality of sleep index between High Damage Group (HDG) and Low Damage Group (LDG). HDG participants exhibited significantly worse sleep quality than LDG participants (Mann-Whitney U-test: z = −3.348, p = 0.001).

Figure 6. Comparison of diurnal type scale between High Damage Group (HDG) and Low Damage Group (LDG) (HDG: 14.17, LDG: 15.12, Mann-Whitney U-test: z = 1.659, p = 0.097).

4. Discussion

4.1. Questionnaire Study

In this study, 20.8% participants scored 25 or more can be decided to be the persons who have PTSD symptoms. Kun et al. [33] reported that the estimated prevalence rate of PTSD symptoms of younger adults was 28.6% (n = 364; 15 - 34 years). Their survey was conducted three months after the 2008 Sichuan earthquake. Another previous study which was undertaken 15 months after the same earthquake reported that the prevalence rate of PTSD symptoms of younger adults was 8.0% (n = 138; <60 years) [34] . In this study, estimated PTSD symptoms remain even 17 years after the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake. A previous study found that PTSD became chronic in 46% of all patients who developed the disorder [35] , and Kessler et al. [36] reported that onethird of individuals who developed PTSD after traumatic event did not have remission of the disorder after ten

Figure 7. IES-R score before the intervention. Only 1 person was over the cut-off point (between 24 and 25).

Figure 8. Comparison of diurnal type scale between before and after the intervention of non high-traumatic persons who showed less than 25 of IES-R score. The diurnal type scale after intervention was significantly higher (more morningtyped) than that before the intervention (Wilcoxon test: z = 2.004, p = 0.045).

Figure 9. Comparison of sleep latency between before and after the intervention of the non high-traumatic persons. It was significantly shortened through the intervention (Wilcoxon test: z = −2.004, p = 0.045).

Table 2. Change in comprehensive variables on sleep health of the high-traumatic person with the IES-R score of 25. This sleep health of this person tended to be improved through the intervention (Wilcoxon test: z = 1.941, p = 0.052).

Table 3. Contents-segregated and cross-sectional analysis on the effects of the intervention to the 65 subjects on the variables of sleep health and circadian typology. The results of Mann-Whitney tests were shown on whether the high-implementatsion group was more impromed than the low-impementation one in each item. AT: Awakening time; SL: Sleep latency; DTS: Diurnal type scale; M: Monroe score for sleep squality; QOS: Quality of Sleep.

◎: sig improve (p < 0.05); ○: tend improve (0.05 ≤ p < 0.1).

years. Why the rate of PTSD in children which suffered such disaster was kept for long years has been remained unclear. Anyway, results of this study suggested that long-lasting mental health care services were required by the people who experienced severe disasters.

This study showed that there was no correlation between diurnal type and PTSD symptoms directly, but morning-typed participants had significantly good sleep quality. And it also resulted in that people who suffered the Great Hanshin-Awaji earthquake in childhood and, moreover, currently have PTSD had difficulty in achieving high sleep quality. A previous study was conducted to investigate the relationship between PTSD and current circadian typology and sleep habits of adults who exposed to the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake after becoming adults. They reported that old people who showed severe PTSD symptoms had a lower quality of sleep and were more evening-typed [21] . Because the PTSD symptoms are relatively moderate in young adults, the relationship between circadian typology and the IES-R score might be unclear in this study.

There are three possible hypothetical and physiological pathways to reduce PTSD symptoms which might be reduced by the morning-typed life. The first possible mechanism is that people who had better quality of sleep could consolidate the memory system during REM sleep and delete the scarce memory of the earthquake, because dreaming during REM sleep consolidates the memorizing system in the brain [37] [38] . The second is via a high amount of serotonin synthesis in the morning due to a rich-protein breakfast [31] [39] [40] followed by light exposure after that [41] . Such high serotonin level in the brain could improve mental health in the daytime. The third one is better inner synchronization of the main and slave clocks [42] . This strong coupling of the two clocks could improve their mental health and reduce the severity of PTSD symptoms. The clocks of morningtype people might be also well entrained to zeitgebers such as light, temperature and social cues.

4.2. Intervention Study

It was difficult to verify the effect of intervention to ease-up the PTSD symptoms because of absence of the participants who had severe PTSD. In the previous intervention study focused on the elderly who experienced the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake (on 17th January 1995) after becoming adults, the prevalence of PTSD was 31.7% (Kuroda, Wada et al., unpublished). Jia et al. [34] found that there were significant distinctions in the prevalence of PTSD (22.5% vs. 8.0%) and general psychiatric morbidity (42.0% vs. 25.4%) between elder and younger adult survivors after an earthquake. They concluded that compared with the younger adults, the elderly survivors were more likely to develop PTSD and general psychiatric morbidity. The underlying mechanisms that the elderly were more likely to develop psychological problems after disasters are still unclear. But Pekovic et al. [44] argued that due to the fact that an elder often already feels frail because of chronic health conditions, impaired cognitive abilities and decreased sensory awareness, the impact of an unexpected disaster may be overwhelming. Additionally Kessler et al. [36] reported that one-third of individuals who develop PTSD after trauma did not have remission of the disorder after ten years. The disaster-related impact seems more severe and lasting than we thought when the elderly were involved in the impaired psychological recovery [45] . It had past seventeen years since the Great Hanshin-awaji Earthquake. The reason of absence of the young participants who had severe PTSD might be related to that the post-disaster vulnerability to PTSD could be age-dependent.

On the other hand, the remains of participants significantly shifted their circadian phase in advance in the sleep-wake rhythms and got better quality of sleep. Intervention study of the same sort for university students belonging to football club concluded that the combined intervention on breakfast, morning sunlight and evening-lighting seems to be effective for students including athletes to keep higher melatonin secretion at night, because this intervention successfully induced easy onset of the night sleep and higher quality of sleep in these athletes [41] . Another previous intervention study (using a leaflet introducing the benefits of morningness and technical issues to make morning-typed life) for the elderly who experienced the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake when they were adult reported that intervention to improve participants’ quality of sleep and promote a morning-typed lifestyle may be an effective way to reduce PTSD symptoms (Kuroda, Wada et al., unpublished). These results suggested that the leaflet intervention would be an effective way to ease up PTSD symptoms for people who suffered natural disaster in childhood and have currently severe PTSD.

4.3. Limitation

The limitation of this study is that the rate of PTSD symptoms the IES-R score reported in our study is only measured by IES-R which is self-reported tool. It is said that interpretation and generalization of the results should be treated with caution because IES-R was not designated to estimate diagnostic prevalence of PTSD [43] .

Intervention to improve their quality of sleep and promote a morning-typed lifestyle may be an effective method to reduce PTSD symptoms. The limitation of this study is absence of the young participants who had severe PTSD in this study. Because of this it is difficult to verify the effect of intervention to PTSD symptoms. It is remained for future studies to test the effect of the leaflet intervention on the ease-up of PTSD in the young people who suffered the East-Japan Great Earthquake on 11th March, 2011.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participants of this study. Thanks are also due to the Kochi University President Foundation for Support of Research (2009-2012: to T. Harada) and Research Funds by JSPS (Fund No: 22370089: 2010-2013: to T. Harada; Found No: 23·10971: 2011-2014: to K. Wada) for financial support. Thanks are also due to Mis Laura Sato who is professional English editor and supported us from linguistic point of view.

References

- Fire and Disaster Management Agency (2006) Fixed Report about the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake.

- Bland, S.H., O’Leary, E.S., Farinaro, E., Jossa, F., Krogh, V. and Violanti, J.M. (1997) Social Network Disturbances and Psychological Distress Following Earthquake Evacuation. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 185, 188-194. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005053-199703000-00008

- Najarian, L.M., Goenjian, A.K., Pelcovitz, D., Mandel, F. and Najarian, B (1996) Relocation after a Disaster: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Armenia after the Earthquake. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 35, 374-383. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199603000-00020

- Chan, C.L.W., Wang, C.-W., Qu, Z., Lu, B.Q., Ran, M.-S., Ho, A.H.Y., Yuan, Y., Zhang, B.Q., Wang, X. and Zhang, X. (2011) Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms among Adult Survivors of the 2008 Sichuan Earthquake in China. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 24, 295-302. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jts.20645

- Kato, H., Asukai, N., Miyake, Y., Minakawa, K. and Nishiyama, A. (1996) Post Traumatic Symptoms among Younger and Elderly Evacuees in the Early Stages Following the 1995 Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake in Japan. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 93, 477-481. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb10680.x

- Tsai, K.Y., Chou, P., Chou, F.H.-C., Su, T.T.-P., Lin, S.-C., Lu, M.-K., Ou-Yang, W.-C., Su, C.-Y., Chao, S.-S., Huang, M.-W., Wu, H.-C., Sun, W.-J., Su, S.-F. and Chen, M.-C. (2007) Three-Year Follow-Up of the Relationship between Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms and Quality of Life among Earthquake Survivors in Yu-Chi, Taiwan. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 41, 90-96. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.10.004

- Livanou, M., Kasvilis, Y., Başoğlu, M., Mytskidou, P., Sotiropoulou, V., Spanea, E., Mitsopoulou, T. and Voutsa, N. (2005) Earthquake-Related Psychological Distress and Associated Factors 4 Years after the Parnitha Earthquake in Greece. European Psychiatry, 20, 137-144. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2004.06.025

- Harada, T. (2008) Diurnal Rhythms and Sleep Habits of Infants, Children and Elder Students Aged 2-25yrs—Focusing on Life Environmental Factors Which Include Ones Related to 24 hrs Commercialization Society. Chronobiology, 14, 36-43.

- Aschoff, J., Gerecke, U. and Wever, R. (1967) Desynchronization of Human Circadian Rhythms. Japanese Journal of Physiology, 17, 450-457. http://dx.doi.org/10.2170/jjphysiol.17.450

- Mecacci, L. and Zani, A. (1983) Morningness-Eveningness Preferences and Sleep-Waking Diary Data of Morning and Evening Types in Student and Worker Samples. Ergonomics, 26, 1147-1153. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00140138308963450

- Hayashi, M. and Hori, T. (1987) Survey on a Sleep Habits for University and High School Students. Hiroshima University Faculty of Integrated Arts and Sciences Bulletin III, 11, 53-63.

- Tanaka, H., Hayashi, M. and Hori, T. (1997) The Developmental Feature of the Sleep Problems in Adolescence: The Approach for the Application to Educational Stage. Memoirs of the Faculty of Integrated Arts and Sciences, Hiroshima University, 23, 141-154.

- Ishihara, K., Miyake, S., Miyashita, A. and Miyata, Y. (1988) Comparisons of Sleep-Wake Habits of Morning and Evening Types in Japanese Worker Sample. Journal of Human Ergology, 17, 111-118.

- Harada, T. and Takeuchi, H. (2001) Epidemiological Study on Students’ Daily Rhythms and Sleeping Habits. Journal Japanese Society for Chronobiology, 7, 36-46.

- Harada, T. and Takeuchi, H. (2011) Chapter 25: Rhythm in Life Habit of Japanese Infants, Children and Students. In: Shibata, S., Ed., Chronobiology and Industrial Applications, CMC Co. Ltd., Tokyo, 204-217.

- Harada, T. (2004) Current Evening Typed Life and Mental Health of Japanese Children. Journal of Child Health, 63, 202-209.

- Klein, E., Koren, D., Arnon, I. and Lavie, P. (2002) No Evidence of Sleep Disturbance in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Polysomnographic Study in Injured Victims of Traffic Accidents. Israel Journal of Psychiatry & Related Sciences, 39, 3-10.

- Wang, L., Zhang, J., Shi, Z., Zhou, M., Huang, D. and Liu, P. (2011) Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms Assessed by the Impact of Event Scale-Revised in Chinese Earthquake Victims: Examining Factor Structure and Its Stability across Sex. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25, 369-375. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.10.011

- Germain, A., Shear, M.K., Hall, M. and Buysse, D.J. (2007) Effects of a Brief Behavioral Treatment for PTSD-Related Sleep Disturbances: A Pilot Study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 627-632. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2006.04.009

- Mellman, T.A., Kumar, A., Kulick-Bell, R., Kumar, M. and Nolan, B. (1995) Nocturnal/Daytime Urine Noradrenergic Measures and Sleep in Combat-Related PTSD. Biological Psychiatry, 38, 174-179. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0006-3223(94)00238-X

- Kuroda, H., Wada, K., Takeuchi, H. and Harada, T. (2013) PTSD Score, Circadian Typology and Sleep Habits of People Who Experienced the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake 17 Years Ago. Psychology, 4, 106-110. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2013.42015

- Torsvall, L. and Åkerstedt, T. (1980) A Diurnal Type Scale: Construction, Consistency and Validation in Shift Work. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 6, 283-290. http://dx.doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.2608

- Kasugai, N. (1999) Anxiety Disorders and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Psychiatry, 28, 171-177.

- Wilson, J.P. and Keane, T.M. (2004) Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD. 2nd Edition, The Guilford Press, New York, 668.

- Harada, T., Inoue, M., Takeuchi, H., Watanabe, N., Hamada, M., Kadota, G. and Yamashita, Y. (1998) Study on Diurnal Rhythms in the Life of Japanese University, Junior High and Elementary School Students including Morningness- Eveningness Preference. Bulletin of the Faculty of Education, Kochi University, 56, 1-91.

- Takeuchi, H., Hino, N., Iwanaga, A., Hino, N., Matsuoka, A. and Harada, T. (2001) Light Conditions during Sleep Period and Sleep-Related Lifestyle in Japanese Students. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 55, 221-222. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1819.2001.00832.x

- Takeuchi, H., Inoue, M., Watanabe, N., Yamashita, Y., Hamada, M., Kadota, G. and Harada, T. (2001) Parental Enforcement of Bedtime during Childhood Results in Japanese Junior High School Students Preferring Morningness to Eveningness. Chronobiology International, 18, 823-829. http://dx.doi.org/10.1081/CBI-100107517

- Harada, T., Morikuni, M., Yoshii, S., Yamashita, Y. and Takeuchi, H. (2002) Usage of Mobile Phone in the Evening or at Night Makes Japanese Students Evening-Typed and Night Sleep Uncomfortable. Sleep and Hypnosis, 4, 150-154.

- Takeuchi, H., Oishi, T. and Harada, T. (2003) Morningness-Eveningness Preference, and Mental and Physical Symptoms during the Menstrual Cycle of Japanese Junior High School Students. Sleep and Biological Rhythms, 1, 245-247. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1446-9235.2003.00042.x

- Shinomiya, H., Takeuchi, H., Martoni, M. Natale, V. and Harada, T. (2004) Comparative Study on Circadian Typology of Japanese and Italian Students Aged 12 - 18 Years. Sleep and Biological Rhythms, 2, 93-95. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1479-8425.2003.00075.x

- Harada, T., Hirotani, M., Maeda, M., Nomura, H. and Takeuchi, H. (2007) Correlation between Breakfast Tryptophan Content and Morningness-Eveningness in Japanese Infants and Students Aged 0-15 Years. Journal of Physiological Anthropology, 26, 201-207. http://dx.doi.org/10.2114/jpa2.26.201

- Portaluppi, F., Smolensky, M.H. and Touitou, Y. (2010) Effects and Methods for Biological Rhythm Research on Animals and Human Beings. Chronobiology International, 27, 1911-1929. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/07420528.2010.516381

- Kun, P., Tong, X., Liu, Y., Pei, X. and Luo, H. (2013) What Are the Determinants of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: Age, Gender, Ethnicity or Other? Evidence from 2008 Wenchuan Earthquake. Public Health, 127, 644-652. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2013.04.018

- Jia, Z., Tian, W., Liu, W., Cao, Y., Yan, J. and Shun, Z. (2010) Are the Elderly More Vulnerable to Psychological Impact of Natural Disaster? A Population-Based Survey of Adult Survivors of the 2008 Sichuan Earthquake. BMC Public Health, 10, 172. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-172

- Davidson, J.R., Hughes, D., Blazer, D.G. and George, L.K. (1991) Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in the Community: An Epidemiological Study. Psychological Medicine, 21, 713-721. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291700022352

- Kessler, R.C., Sonnega, A., Bromet, E., Hughes, M. and Nelson, C.B. (1995) Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. JAMA Psychiatry, 52, 1048-1060. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012

- Karni, A., Tanne, D., Rubenstein, B.S., Askenasy, J.J. and Sagi, D. (1994) Dependence on REM Sleep of Overnight Improvement of a Perceptual Skill. Science, 265, 679-682. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.8036518

- Hornung, O.P., Regen, F., Danker-Hopfe, H., Schredl, M. and Heuser, I. (2007) The Relationship between REM Sleep and Memory Consolidation in old Age and Effects of Cholinergic Medication. Biological Psychiatry, 61, 750-757. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.08.034

- Nakade, M., Takeuchi, H., Taniwaki, N., Noji, T. and Harada, T. (2009) An Integrated Effect of Protein Intake at Breakfast and Morning Exposure to Sunlight on the Circadian Typology in Japanese Infants Aged 2-6 Years. Journal of Physiological Anthropology, 28, 239-245. http://dx.doi.org/10.2114/jpa2.28.239

- Nakade, M., Akimitsu, O., Wada, K., Krejci, M., Noji, T., Taniwaki, N., Takeuchi, H. and Harada, T. (2012) Can Breakfast Tryptophan and Vitamin B6 Intake and Morning Exposure to Sunlight Promote Morning-Typology in Young Children Aged 2-6 Years? Journal of Physiological Anthropology, 31, 11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1880-6805-31-11

- Wada, K., Yata, S., Akimitsu, O., Krejci, M., Noji, T., Nakade, M., Takeuchi, H. and Harada, T. (2013) A Tryptophan- Rich Breakfast and Exposure to Light with Low Color Temperature at Night Improve Sleep and Salivary Melatonin Level in Japanese Students. Journal of Circadian Rhythms, 11, 4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1740-3391-11-4

- Honma, K. and Honma, S. (1998) A Human Phase-Response Curve for Bright Light Pulses. Japanese Journal of Psychiatry and Neurology, 42, 167-168.

- Chan, C.L.W., Wang, C.W., Qu, Z., Lu, B.Q., Ran, M.S., Ho, A.H.Y., Yuan, Y., Zhang, B.Q., Wang, X. and Zhang, X. (2011) Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms among Adult Survivors of the 2008 Sichuan Earthquake in China. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 24, 295-302. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jts.20645

- Pekovic, V., Seff, L. and Rothman, M.B. (2007) Planning for and Responding to Special Needs of Elders in Natural Disasters. Generations, 31, 37-41.

- Toyabe, S., Shioiri, T., Kuwabara, H., Endoh, T., Tanabe, N., Someya, T. and Akazawa. K. (2006) Impaired Psychological Recovery in the Elderly after the Niigata-Chuetsu Earthquake in Japan: A Population-Based Study. BMC Public Health, 6, 230. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-6-230

NOTES

*Corresponding author.