Journal of Modern Physics

Vol.07 No.16(2016), Article ID:72783,13 pages

10.4236/jmp.2016.716200

Conservation of Energy in Classical Mechanics and Its Lack from the Point of View of Quantum Theory

Stanisław Olszewski

Institute of Physical Chemistry, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland

Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: November 7, 2016; Accepted: December 12, 2016; Published: December 15, 2016

ABSTRACT

It is pointed out that the property of a constant energy characteristic for the circular motions of macroscopic bodies in classical mechanics does not hold when the quantum conditions for the motion are applied. This is so because any macroscopic body―lo- cated in a high-energy quantum state―is in practice forced to change this state to a state having a lower energy. The rate of the energy decrease is usually extremely small which makes its effect uneasy to detect in course of the observations, or experiments. The energy of the harmonic oscillator is thoroughly examined as an example. Here our point is that not only the energy, but also the oscillator amplitude which depends on energy, are changing with time. In result, no constant positions of the turning points of the oscillator can be specified; consequently the well-known variational procedure concerning the calculation of the action function and its properties cannot be applied.

Keywords:

Classical Mechanics and Conservation of Energy, Motion Quantization of Macroscopic Bodies, Energy and Time of Transitions between Quantum States, Harmonic Oscillator Taken as an Example

1. Introduction

Mechanics is usually considered as a fundamental part of physics because of its role in establishing the physical ideas. In fact, with its aid the motion kinds of the bodies were rather easily percepted and classified according to their character. A systematic study of mechanics was stimulated especially by astronomy. Here a fundamental guide became an access to a less or more accurate repetition of the observed effects and events.

In result, the best examined motions could be classified as belonging to two domains. One of them concerned the periodic motions where the body returns to its original position after some period of time, another domain of mechanics considered typical progressive motions in space and time. For this second kind of motions the top results could be obtained in the framework of the relativistic theory. The main feature in description of this kind of motions became a necessary coupling between the space intervals and intervals of time.

Evidently another characteristics than for progressive motions became dominant in describing the periodic motions. Here a principal mechanical parameter is the system energy. A constant property of that parameter was at the basis of the whole mechanics of the examined system. As far as the motion of a celestial body―especially that present in the solar system―was examined, the theoretical framework based on the conser- vation property of energy seemed to be fully satisfactory; see e.g. [1] [2] . A difficulty came when the atomic systems were discovered and―at the initial stage of the quantum theory―the periodic character of the electron motion in the atom was attempted to be described in a way not much different than applied for the body motion in the solar system. The main change which had to be taken into account concerned the fact that a single electron particle in the atom―concretely the hydrogen atom―could assume different but strictly specified energy values called the energy states. Excepting for the state having the lowest energy, an occupation of the other, i.e. higher energy levels, could be only temporary. This is so because at some time moment―undefined by the theory―the electron is going from a state of a higher energy to the state of a lower energy. The transition process is connected with the emission of energy equal to a difference between the initial and final levels of energy. The Bohr theory could―with a high accu- racy―to define the energy levels in the atom and corresponding differences between them [3] [4] . A difficulty―rather fundamental―was due to the fact that the time of the electron transition process between the states remained an unknown quantity.

In result the emission intensity of energy in the atom was specified solely with the aid of a complicated quantum-mechnical radiation theory based on a probabilistic back- ground [5] [6] . Complication of such calculations became evident because of necessity of the use of possibly accurate electron wave functions [4] [7] [8] . A difficulty of the access to such functions increased very rapidly with increase of the number of electron particles present and interacting in the atom.

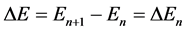

Only recently the time interval of the electron transitions could be estimated with no reference to the wave functions. This was done with the aid of the classical electrody- namics in which the Joule-Lenz theory of the dissipated energy has been adapted to the quantum electron transitions [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] . For, when two neighbouring quantum levels separated by the energy interval

(1)

(1)

are considered, the time of the electron transition  between the levels is given by the formula

between the levels is given by the formula

(2)

(2)

where  is the Planck constant

is the Planck constant

The formula (2) has occurred to be valid also for other quantum systems than the hydrogen atom [9] [12] . Here a rather fundamental question could be raised what is the relation between  and

and  when

when

(3)

(3)

and

(4)

(4)

so the interval  in (3) concerns the non-neighbouring quantum levels. An approach to this problem is presented in Section 2.

in (3) concerns the non-neighbouring quantum levels. An approach to this problem is presented in Section 2.

In general, the classical mechanics and quantum theory are seldom compared, since usually they are applied to different―respectively macroscopic and microscopic―areas of physics. Perhaps a best known comparison is represented by the Ehrenfest theorem according to which the Hamilton equations are shown to be equally applicable to the classical particles and quantum wave-packets [7] . In the case of the present approach a comparison of the quantum and classical theory could be extended to such classical systems like planets and satellites, or the macroscopic harmonic oscillator.

Basing on the old quantum theory [14] it has been found for planets and satellites that their energy can by no means remain a constant number but should decrease systematically with time [15] , on condition the masses of the gravitationally interacting bodies remain unchanged. In the present paper the case of a classical harmonic oscil- lator is examined. In fact an approximate agreement of the both kinds―classical and quantum―approaches can be considered as satisfactory. This is so because the rate of the energy decrease of classical systems calculated with the aid of the quantum theory is exceedingly small.

The point considered in the present paper―as well as in [15] ―seems to be fully new and never examined before.

2. Energy Emission and Transition Times of Electrons between Non-Neighbouring Quantum Levels

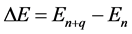

In this case the formula (2) does not hold. In place of it one of the factors entering (2) becomes

(5)

(5)

on condition we take for the components in (5) the expressions:

(6)

(6)

Evidently any difference on the right of (6) concerns the neighbouring electron levels.

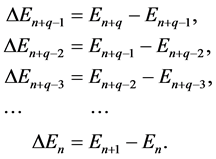

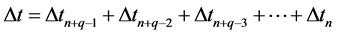

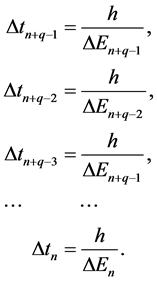

Time interval  and energy interval

and energy interval  enter (2) on an equal footing, therefore we assume that for

enter (2) on an equal footing, therefore we assume that for  we have

we have

(7)

(7)

where the formulae for the components in (7) are referred to the energy components in (5) by:

(8)

(8)

The formulae (8) hold because the relations between the energy differences and time differences concerning the neighbouring electron levels are dictated by the formula (2).

The validity of transition intensities

(9)

(9)

calculated according to (5)-(8) (see [16] [17] ) was confirmed by comparing the ratios of the intensities calculated in (9) with the quantum-mechanical ratios of transition probabilities in the hydrogen atom; see [8] . In general the agreement of both kinds of approach―quantum-mechanical and the present one―can be considered as satisfac- tory. It should be noted that the next interval of time begins immediately after a former one, which is a situation similar to the behaviour of the energy intervals in the emission process, where a lower interval of energy begins immediately after a higher one.

In the next section (Section 3) the energy relations for a macroscopic harmonic oscillator are considered.

3. Energy Relations for a Macroscopic Harmonic Oscillator

Classically a well-known property of energy of the harmonic oscillator, which―for the sake of simplicity―can be reduced to a linear system, is its conservation with time [1] [18] . In course of the oscillator motion we have two different energy components corre- sponding to the kinetic and potential energy, respectively, which add together at any time to a constant number of the total energy dependent solely on the oscilllator ampli- tude  and the oscillator constant

and the oscillator constant

The

the frequency

As far as

where

The quantization of the oscillator is a simple task. We have the velocity

the momentum

and the integral

If the integral (16) is extended over the time interval

where

therefore

Respectively the oscillator energies are [see (10) and (11)]:

and their difference becomes

Evidently at

4. Upper Limit of the Oscillator Frequency Due to the Energy-Time Uncertainty Principle and an Upper Limit of the Emission Rate

There exists a limit of the time interval

This relation replaces an earlier formula coupling

In fact a substitution of the quantum formula (2) deduced from the Joule-Lenz law into (21) gives the relation

from which we obtain

The result on the right of (24) is similar to that obtained earlier also on the basis of the energy-time uncertainty principle [4] [12] [23] :

In calculating the emission process of a single electron transition we have the in- tensity

because (26) gives

which is evidently identical with the formula (2):

On the other side from (20) we obtain

In effect from (27) and (29) we arrive at the equality

which is a situation characteristic not only for the harmonic oscillator but also for other quantum systems [9] [11] [12] [24] . A substitution of (30) into (24) gives

therefore

This relation, which for the electron mass

represents the upper limit of the frequency

A substitution of result (32) into (29) gives immediately an upper limit for the energy interval

Respectively the value of the frequency limit in (34) is equal to

A characteristic point is that the upper limit presented in (34a) is proportional to the particle mass

There exists also an upper limit of the emission rate of energy. It can be shown that this limit remains the same independently of that whether it is derived on the basis of the formula (2), or directly from the Joule-Lenz law for the dissipation of energy. In the case when the formula (2), or (26), is applied we have from (24) and (34):

On the other hand, the emission rate obtained from the Joule-Lenz law is

where

(characteristic for the integer quantum Hall effect [25] ), so

because of the formula (24).

Evidently the results based on the quantum uncertainty principle are of not much use for the macroscopic level.

5. Dissipation of Energy of the Macroscopic and Microscopic Oscillator

Our aim is to show that the dissipation of energy concerns equally a microscopic and macroscopic oscillator, though evidently it is relatively much less important in the macroscopic case.

In the microscopic situation we have a well-known emission of the quanta

Let us assume a macroscopic oscillator having mass

This implies the quantum condition [see (17)]

therefore

Equation (42) indicates that a very high quantum state

Since the energy of the oscillator in state

a lowering of (43) by the amount

leads to the energy

In the quantum approach to the Joule-Lenz law [9] [12] the lowering of energy represented by (44) takes place within the time interval equal to the oscillation period, i.e.

So―because of (40) and inferences before it―the formula (44) corresponds to the amount of emitted energy:

This is a very small amount of energy if we compare it with the energy of state

Practically a full loss of the energy (47) will occur when the oscillator being in state

if we note that approximately

Therefore―strictly speaking―the energy of the oscillator cannot be conserved. How- ever, the rate of decrease of energy is extremely small which makes uneasy to detect it in course of the observations or experiments.

6. Discussion: Energy Decrease and the Damping Term of the Oscillator

The decrease of the oscillator energy can be examined with the aid of the corresponding damping coefficient

Here

where

because of (11), and the same result gives the averaged potential energy.

Since

we find that

or

For the classical macroscopic oscillator considered in Sec. 5 we obtain from (40) and (42)

A characteristic point is that a similar value for

where

and

we arrive at:

This

so

The size of the frequency

7. Conclusions

In some earlier papers by the author [9] [10] [12] , an attempt has been done to establish the time interval

Another property of

[see also (30)], where

between states

The idea of the former [15] and present paper was to consider the classical mecha- nical systems of a periodic character on a quantum footing in spite of their macroscopic size. This has been done on the basis of the old quantum theory. In course of the treat- ment it became of importance to know―in the first step―whether

In [15] the celestial bodies of the solar system have been examined. With the neglected luminosity effect represented by the mass decrease of the Sun due to its light emission, the validity of (2) has been checked, first, by calculating

The present paper concerns the quantum approach to the macroscopic harmonic oscillator. In this treatment the validity of (2) and (63) could be easily confirmed. In any quantum calculation done on the macroscopic body the number

A basic result obtained from the quantum approach to the periodic macroscopic systems is that―strictly speaking―no conservation of energy does exist for such sys- tems, as far as the system does not reach its ground state represented by the lowest possible energy. In reality any of the examined systems had a huge index

This result can be compared with a totally different situation of the micoscopic systems like atoms. Here the energy emitted in a single transition is large, when com- pared with the total energy possessed by the electron, and the number of steps necessary to attain the ground state is relatively small. This makes the emission rate of energy relatively large.

There remains still the problem of causality of the transition process between the quantum states. In fact the very existence of these states is rather postulated by the (old) quantum theory than derived from a more advanced formalism, for example quantum mechanics. But there is no reason to reject such postulate.

Another problem is the time of the body transitions between the quantum states. This point seems to be carefully avoided by many of quantum physicists instead to be put into a calculational practice. In fact any transition rate of energy is considered from the very beginning of quantum theory―also the old one―solely on a probabilistic footing [5] [6] . This kind of approach does not apply to the theory outlined in the present paper: here, in course of any period

Cite this paper

Olszewski, S. (2016) Conservation of Energy in Classical Mecha- nics and Its Lack from the Point of View of Quantum Theory. Journal of Modern Phy- sics, 7, 2316-2328. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2016.716200

References

- 1. Sommerfeld, A. (1943) Mechanik. Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft, Leipzig.

- 2. Goldstein, H. (1965) Classical Mechanics. Addison-Wesley, Reading.

- 3. Bohr, N. (1922) The Theory of Spectra and the Atomic Constitution. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- 4. Slater, J.C. (1960) Quantum Theory of the Atomic Structure. Vol. 1, McGraw-Hill, New York.

- 5. Planck, M. (1910) Acht Vorlesungen ueber Theoretische Physik. S. Hirzel-Verlag, Leipzig.

- 6. Einstein, A. (1917) Physikalische Zeitschrift, 18, 121.

- 7. Schiff, L.I. (1968) Quantum Mechanics. 3rd Edition, McGraw-Hill, New York.

- 8. Condon, E.U. and Shortley, G.H. (1970) The Theory of Atomic Spectra. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- 9. Olszewski, S. (2015) Journal of Modern Physics, 6, 1277.

https://doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2015.69133 - 10. Olszewski, S. (2016) Quantum Matter, 5, 723.

https://doi.org/10.1166/qm.2016.1372 - 11. Olszewski, S. (2016) Reviews in Theoretical Science, 4, 336-352.

https://doi.org/10.1166/rits.2016.1066 - 12. Olszewski, S. (2016) Journal of Modern Physics, 7, 162-174.

https://doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2016.71018 - 13. Olszewski, S. (2016) Journal of Modern Physics, 7, 1725-1737.

https://doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2016.713155 - 14. Sommerfeld, A. (1931) Atombau und Spektrallinien. Vol. 1, 5th Edition, Vieweg, Braunschweig.

- 15. Olszewski, S. (2016) Journal of Modern Physics, 7, 1901-1908.

https://doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2016.714168 - 16. Olszewski, S. (2016) Journal of Modern Physics, 7, 827-851.

https://doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2016.78076 - 17. Olszewski, S. (2016) Journal of Modern Physics, 7, 1004-1020.

https://doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2016.79091 - 18. Landau, L.D. and Lifshitz, E.M. (2002) Theoretical Physics Vol. 1: Mechanics. 5th Edition, Fizmatlit, Moscow. (In Russian)

- 19. Olszewski, S. (2011) Journal of Modern Physics, 2, 1305-1309.

https://doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2011.211161 - 20. Olszewski, S. (2012) Journal of Modern Physics, 3, 217-220.

https://doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2012.33030 - 21. Olszewski, S. (2012) Quantum Matter, 1, 59-62.

https://doi.org/10.1166/qm.2012.1006 - 22. Heisenberg, W. (1927) Zeitschrift fuer Physik, 43, 172-198.

https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01397280 - 23. Olszewski, S. (1964) Journal of Modern Physics, 5, 1264-1271.

https://doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2014.514127 - 24. Olszewski, S. (2016) Quantum Matter, 5, 664-669.

https://doi.org/10.1166/qm.2016.1360 - 25. MacDonald, A.H. (1989) Quantum Hall Effect: A Perspective. Kluwer, Milano.

- 26. Lindsay, R.B. and Margenau, H. (1963) Foundations of Physics. Dover Publications, New York.

- 27. Kittel, C. (1987) Quantum Theory of Solids. 2nd Edition, Wiley, New York.