Journal of Modern Physics

Vol.06 No.06(2015), Article ID:56409,7 pages

10.4236/jmp.2015.66082

An Alternative Approach to Particle-Particle Collisions

C. Y. Chen

Department of Physics, Beihang University, Beijing, China

Email: cychen@buaa.edu.cn, chen4607@gmail.com

Copyright © 2015 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 22 March 2015; accepted 16 May 2015; published 19 May 2015

ABSTRACT

A new alternative approach to the statistical behavior of particle-particle collisions is introduced. The alternative approach is derived rigorously from well known mechanical laws; and the results given by it, quantitatively and qualitatively different from what the standard kinetic theory yields, can be directly checked with computer-simulated or realistic experiments. More importantly, from the introduction of it, a number of new concepts and new methodologies emerge, which might turn out to be very significant to the future development of nonequilibrium statistical mechanics.

Keywords:

Non-Equilibrium, Statistical Mechanics, Boltzmann Equation, Distribution Function, Discontinuity

1. Introduction

It is commonly believed that the statistical behavior of classical particle-particle collisions has been adequately codified into the equations of nonequilibrium gas dynamics (kinetic theory), and there is nothing truly new to today’s physicists. However, as has been pointed out by us [1] [2] , this belief is questionable.

What made us question the validity of the standard theory might be summarized as the following. In the context of gas dynamics, particle-particle collisions are supposed to be examined in the six-dimensional position- velocity phase space, but the space, though superficially simple, is inherently counterintuitive. When a six- dimensional statistical dynamics is of concern, it is often the case that our attention is invited to certain incomplete and misleading pictures. To get a taste of such trickiness, let’s briefly review a long-neglected fact associated with the Boltzmann equation [3] : while the differential operator on its left-hand side enjoys a relatively obvious position-velocity symmetry, the integral operator on its right-hand side does not exhibit any form of position-velocity symmetry. In this regard, one may reasonably wonder: How can the equation’s two sides be always equal when they behave themselves so differently?

In this paper, after advancing several typical examples, an alternative approach is proposed, which takes care of the position space and the velocity space in a relatively balanced way. The proposed formalism is strictly based on well-known mechanical laws, and the results given by it can be directly compared with computer simulations. More importantly, from the introduction of this alternative approach, a number of new concepts and new methodologies emerge, which might turn out to be very significant to the future development of nonequilibrium statistical mechanics.

The structure of this paper is the following. In Section 2, several examples are advanced in which particle- particle collisions cannot be well treated by the standard kinetic theory. In Section 3, an alternative approach is proposed. In Section 4, the newly proposed alternative approach is extended to more general situations. In Section 5, a brief summary is provided.

2. Typical Examples of Particle-Particle Collisions

To investigate the collective behavior of particle-particle collisions, we shall in this paper concern ourselves with three different, but interconnected, situations shown in Figure 1. They are a) a parallel beam of particles scattered by a group of resting particles, b) two parallel beams of particles colliding in the head-on manner, and c) two ordinary gases colliding with each other.

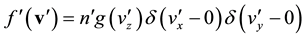

To begin with, let’s first look at the simplest situation illustrated in Figure 1(a). Suppose that the parallel beam on the left side is moving in the  -direction (rightwards), and the distribution function of it is

-direction (rightwards), and the distribution function of it is

(1)

(1)

where  is considered to be time-independent and

is considered to be time-independent and  -independent and

-independent and  over

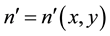

over  is equal to 1. The resting particles on the right side are described by the distribution function

is equal to 1. The resting particles on the right side are described by the distribution function

(2)

(2)

where  is time-independent.

is time-independent.

Figure 1. Various setups: (a) A parallel beam of particles scattered by resting particles; (b) Two parallel beams colliding in the head-on man- ner; (c) Two ordinary gases colliding with each other.

There are several reasons why we start our investigation with this particular example. Firstly, this is the case to which the standard collision theory is presumably applicable. Secondly, this is the case that we, as physicists, can easily realize and easily monitor in computer simulation. Thirdly, this is the case in which the complexity of the subject is largely reduced but the statistical characteristics of the subject remain intact (so the insight gained will be generally instructive).

It is further assumed that a virtual detector, marked as  in the figure, is placed at the position where the local distribution function is of interest. This arrangement possesses great importance in this paper; and the basic idea behind it is that the distribution function determines, almost uniquely, the local flux, and hence the distribution function should be directly computable if the flux information gathered by the detector situated there is somehow known. It will be seen that with certain improvement and refinement this simple idea works nicely. In contrast with that, the basic idea of the standard theory seems rather cumbersome. According to the standard theory, to determine the distribution function at a place we are supposed to investigate how the distribution function varies at the place, and to determine how the distribution function varies at the place we are supposed to investigate virtually all the fluxes around the place (eventually 12 coming-or-going fluxes are examined).

in the figure, is placed at the position where the local distribution function is of interest. This arrangement possesses great importance in this paper; and the basic idea behind it is that the distribution function determines, almost uniquely, the local flux, and hence the distribution function should be directly computable if the flux information gathered by the detector situated there is somehow known. It will be seen that with certain improvement and refinement this simple idea works nicely. In contrast with that, the basic idea of the standard theory seems rather cumbersome. According to the standard theory, to determine the distribution function at a place we are supposed to investigate how the distribution function varies at the place, and to determine how the distribution function varies at the place we are supposed to investigate virtually all the fluxes around the place (eventually 12 coming-or-going fluxes are examined).

Before entering the next section, where a new alternative approach will be introduced, let’s briefly go through what the Boltzmann equation has to say about the situation. Referring to Figure 1(a), suppose that the symmetry axis of  is the positive

is the positive  -coordinate axis and the origin of the

-coordinate axis and the origin of the  -coordinate starts from the bottom of the collision region. Thus, the distribution function of the collision-produced particles moving along the

-coordinate starts from the bottom of the collision region. Thus, the distribution function of the collision-produced particles moving along the  -axis obeys (with no external forces)

-axis obeys (with no external forces)

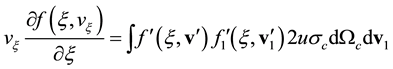

, (3)

, (3)

in which  and

and

In writing these two formulas, it is understood that the two initial gases are dilute enough so that the collision probability between

Surprisingly, although formally pertinent, expression (4) yields no meaningful result for the situation. Firstly, if we wish to compute the integral involved, we find no attainable way to get rid of the five

When treating the examples shown in Figure 1(b) and Figure 1(c), similar difficulties will be met with. In particular, the difficulty shown in Figure 2 is always there.

There has been a detailed investigation about the sources of the aforementioned problems [1] . In this paper, we shall focus ourselves on proposing a new alternative approach.

3. An Alternative Approach

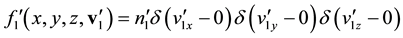

In connection with the situation shown in Figure 1(a), we now look at Figure 3(a) and Figure 3(b), in which

Figure 2. The qualitative illustration of the distribution func- tion along the axis of the detector in Figure 1(a).

Figure 3. Aftermath of a collision: (a) In the position space one of the two colliding particles starts to move toward the de- tector; (b) in the velocity space the two particles get new velocities,

the aftermath of a collision is illustrated in the position space and in the velocity space respectively. The two figures are drawn quite generally and their full implications will manifest themselves in this and the next sections.

In Figure 3(a), suppose that

where

Concerning expression (5), there are essential things worth discussing. To ensure that the right side of the expression stands for the “exact” distribution function at the position point

To make expression (5) physically meaningful in rather general situations, we shall adopt the following two assumptions: 1)

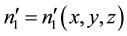

Under these two assumptions, we redefine the distribution function as a mathematical hybrid:

where

At this point, one remark seems in order. In the standard theory the distribution function, as the primary concept of the theory, is often defined or interpreted in intentionally vague language. For instance, in one of the books on nonequilibrium statistical mechanics [4] it is stated that the distribution function, denoted as

We take three steps to compute expression (6): 1) finding out the position region in which particle-particle collisions may possibly give contribution to

The first two steps can be accomplished rather easily. Since the solid angle

where

To accomplish the third step aforementioned, let’s first note that the information concerning how the scattered particles spread in the position space and the velocity space is stored in

Referring to Figure 3(a) and Figure 4(a), we find that there is an infinitely sharp cone formed by the point

Since

To connect the center-of-mass frame and the laboratory frame, we have to deal with the energy-momentum

Figure 4. Schematic of (a) how the scattered particles with

conservation law explicitly. Let all the particles in our consideration have the same mass (for simplicity); and let

where

The above expressions show that for a pair of

in which

With help of Equations (8), (9), (12) and (13), the limit-average-hybrid distribution function defined by Equation (6) is

in which the integration region of

Unlike expression (4), expression (14) is obviously computable. It yields a finite and definite result no matter whether

4. Extensions of the Alternative Approach

Now, we look at how to extend our proposed approach to the cases shown in Figure 1(b) and Figure 1(c).

Let the gas on the left-hand side of Figure 1(b) be represented by

where

where

Again, we are interested in determining

position of the detector’s inlet in Figure 1(b).

By defining the up-zone,

in which

Now, the energy-momentum conservation law shows us that

and Equation (17) becomes

in which

is the Jacobian of the variable transformation. Notice that Figure 4(a) makes sense generally as long as we disregard

where

in which the integration region of

namely, by

As for the general case shown in Figure 1(c), the formulation is about the same. Firstly, the collision number taking place in the up-zone can be represented by

where

in which

Notice that in Equation (25)

in which

velocity space,

sion can be determined by

which is interpreted similarly to the diagram given in expression (23).

Obviously, both expressions (22) and (27) are directly computable, and ready to be checked with computer-simulated or realistic experiments.

It is easy to see that if

5. Summary

In this paper, to formulate the statistical behavior of particle-particle collisions, a new alternative integral formalism has been introduced. The results given by the new formalism are quantitatively and qualitatively different from what the standard theory yields. If interested, readers may confirm or deny them by applying their own theoretical and/or numerical approaches.

More importantly, along with the introduction of the new approach, a set of new concepts and methodologies are proposed, which might turn out to be very significant to the future development of nonequilibrium statistical mechanics. Some of them are:

Due to the discontinuity concern, the distribution function in a nonequilibrium approach should be defined as an average in the position-velocity phase space, at least partially.

Instead of using differential-integral equations, approaches of completely integral type should be employed.

Instead of examining the events in a control volume element, what takes place in an upstream path zone should be investigated.

Collisional effects should be studied in both the position space and the velocity space. The energy- momentum conservation law should be fully incorporated.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Drs. M. Berry, O. Penrose, R. Littlejohn, V. Travkin, W. Hoover, Hanying Guo, Tian- rong Zhang, Keying Guan, Xingren Ying for their direct or indirect encouragement. The discussions with them have been pleasant and helpful.

References

- Chen, C.Y. (2002) Il Nuovo Cimento B, 117B, 177.

- Chen, C.Y. arXiv: 0812.4343 [physics.gen-ph]; cond-mat/0608712, 0504497, 0412396; physics/0312043, 0311120, 0305006, 0010015, 0006033, 0006009, 9908062.

- Reif, F. (1965) Fundamentals of Statistical and Thermal Physics. McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York.

- Dorfman, F. (1999) An Introduction to Chaos in Nonequilibrium Statistical Mechanics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511628870