International Journal of Clinical Medicine

Vol.2 No.5(2011), Article ID:8772,2 pages DOI:10.4236/ijcm.2011.25093

Sport in Psychiatric Rehabilitation:A Tool in Pre-Acute, Post-Acute and Chronic Phase

![]()

Unit of Mental Health, Pontedera (PI), Department of Psychiatry, Pisa, Italy.

Email: gcorretti@yahoo.it

Received August 15th, 2011; revised September 25th, 2011; accepted October 7th, 2011.

Keywords: Sport, Psychiatry, Psychiatric Rehabilitation, Psychiatric Illness, Primary Prevention, Post-Acute, Sociality, Recovery

ABSTRACT

The principal goal of psychiatric rehabilitation is to improve the global functioning of a person who suffer from a mental disorder. New emerging groups of patients meet difficult to attend to a rehabilitation program. Sport represents a new flexible model that can be used in psychiatric rehabilitation. Sport improves physical health and well being, increases sociality, increases self-efficacy and self-esteem. It is well accepted and well tolerated by the patients, too. Its use goes over the chronic phase of illness (typical target of rehabilitation) and it extends to the post-acute and pre acute phase, too.

1. Introduction

Psychiatric rehabilitation involves patients with serious mental disorders. The focus of rehabilitation program is on improvement and the goal is represented by an increase in the global functioning of the person, based on his/her age, cultural aspects and subjective interests.

A psychiatric rehabilitation program requires to develop a strong trust-based relationship with the client.

New groups of patients have been emerged as being particularly difficult to stay in a common rehabilitation program and setting. They are often young, with incomplete response to the treatment and a wide range of other problems (drugs, homelessness, etc.). Often they don’t accept a strictly defined and rigorous program with a change in their lifestyle although it could represent an increase in their quality of life. As confirm, sometimes these patients search alternative health care practices, that they think more fit, such as yoga, massage, meditation, etc. [1].

This means that rehabilitation services should move towards much more flexible models and programs in rehabilitation.

2. Sport in Mental Health

2.1. The Role of Sport in Mental Health

Sport is not only physical activity, as described in the White Paper on Sport [2], a document of European Commission, infact sport has an educational dimension and plays a social, cultural and recreational role. Sport promotes a shared sense of belonging and participation. In addition to this, sport activities contributing to social cohesion and social inclusion of vulnerable groups (such as people with severe psychiatric illness) can be considered as social services of general interest.

We use sport as specific tool for a good recovery in people affected by serious mental disorders.

Infact sport:

• Improves physical health and well being, reduces morbidity and mortality in associated general medical conditions [3-5];

• Give more opportunity for social interactions, and sometimes it is a training to increase sociality [2];

• Increases self-efficacy and self-esteem, due to the consciousness of improvements in sport ability;

• Is well accepted and well tolerated by the patients [5].

2.2. Sport in Different Phases of the Mental Disorder

Although commonly rehabilitation program are addressed to chronic patients, we extend it to other categories: post-acute and pre-acute patients.

Post-acute is a delicate phase after an hospitalization. The first episode of hospitalization, commonly coincide with the beginning of a mental disorder. The establishment

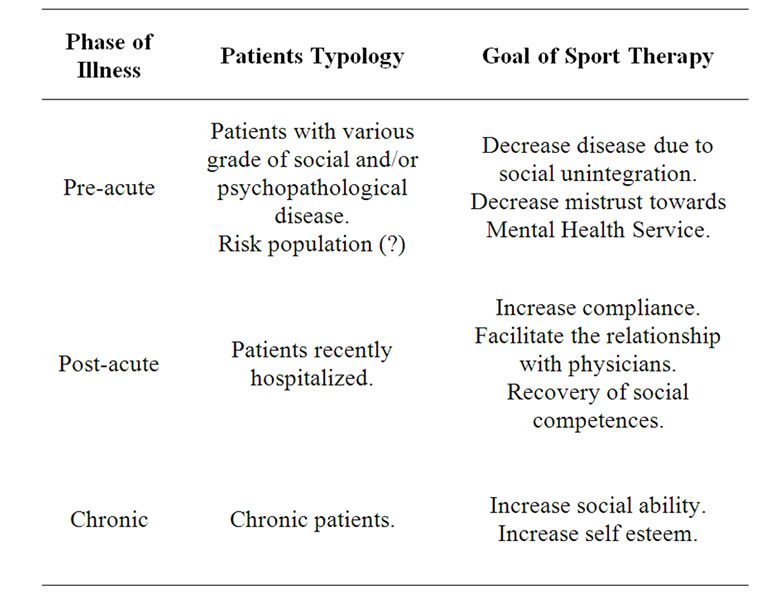

Table 1. Summary table about pahase of illness, patients typology and phase-specific goal of sport treatment.

of strong relationship with the physicians is necessary for an adequate adherence to the therapeutic program. Suspiciousness and mistrust obstacolate this link. Sport represents an uncommon tool to steady this connection, increasing mutual trust. On the other way, relapses are common in post-acute phase when patients have poor compliance [6]. High trust means high relationship with physicians and high compliance, too [7]. Definitely, sport increases compliance.

In pre-acute patients, sport plays the role of primary prevention. During last years many immigrants have been hospitalized in our psychiatric unit for a suicide attempt. This is a group of persons that show bad attitudes, when they was at the climax of a social disease (lack of integration). Provide social opportunities and take part in a sport team can decrease this disease, improving social life. This kind of sport can be extended to other risk populations for psychiatric or behavioural disorders.

3. Acknowledgements

Thanks to to R. Fabiani, F. Giunti, M. Cirri, M. Cecchetti.

REFERENCES

- Z. Russinova, N. J. Wewiorski and D. Cash, “Use of Alternative Health Care Practices by Persons with Serious Mental Illnes: Perceived Benefits,” American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 92, No. 10, 2002, pp. 1600-1603. doi:10.2105/AJPH.92.10.1600

- White Paper On Sport, Brussels, 2007. http://ec./Europa.eu/sport/white-paper/index_en.htm

- D. R. Jones, C. Macias, P. J. Barreira, W. H. Fisher, W. A. Hargreaves and C. M. Harding, “Prevalence, Severity, and Co-Occurrance of Chronic Physical Health Problems of Persons with Serious Mental Illness,” Psychiatric Services, Vol. 55, No. 11, 2004, pp. 1250-1257. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.55.11.1250

- C. R. Richardson, G. Faulkner, J. McDevitt, et al., “Integrating Physical Activity into Mental Health Services for Persons with Serious Mental Illness,” Psychiatric Services, Vol. 56, No. 3, 2005, pp. 324-331. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.56.3.324

- A. Fagiolini, A. L. Montejo, P. Thomas, et al., “Physical Health Considerations in Psychiatry: European Views on Recognition, Monitoring and Management,” European Neuropsychopharmacology, Vol. 18, Supplement 2, 2008, p. 3. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2008.02.001

- H. Ascher-Svanum, B. Zhu, D. E. Faries, et al., “The Cost of Relapse in the Treatment of Schizophrenia,” BMC Psychiatry, Vol. 10, No. 2, 2010, pp. .

- A. Charpentier, M. Goudermand and P. Thomas, “Therapeutic Alliance, a Stake in Schizophrenia,” Encephale, Vol. 35, No. 1, 2009, pp. 80-89. doi:10.1016/j.encep.2007.12.009