Open Journal of Political Science

Vol.06 No.01(2016), Article ID:62647,16 pages

10.4236/ojps.2016.61007

Unrecognized States in the Former USSR and Kosovo: A Focus on Standing Armies

Yoko Hirose

Faculty of Policy Management, Keio University, Kanagawa, Japan

Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 24 September 2015; accepted 8 January 2016; accepted 11 January 2016

ABSTRACT

The end of the Cold War and the collapse of the USSR and Yugoslavia result in a proliferation of unrecognized and weak states, which continue to exist today. This article considers the relationship between unrecognized states and the major powers, Russia and the United States, by focusing on the foreign military bases or standing armies of the latter. In addition, unrecognized states, their parent countries, and similar states have received significant merits and profits from being unrecognized states, and this situation has also helped the survival of unrecognized states. It is possible that unrecognized states can be understood as part of the global strategies of the two great powers and that these states have been maintained through a complex negotiation process that is designed to maintain the superpowers’ global influence.

Keywords:

Unrecognized States, Standing Army, American and Russian Military Bases, Cold War

1. Introduction

The proliferation of unrecognized states begins after WWII and peaks after the end of the Cold War, an event that largely coincides with the collapses of the USSR and Yugoslavia (Von Glahn, 1996) . Scholarship has looked at the phenomenon of unrecognized states from a number of vantage points, with the latest and most comprehensive definition of this phenomenon as follows:

(1) An unrecognized state has achieved de facto independence, covering at last two-thirds of the territory to which it lays claim and includes its main city and key regions.

(2) Its leadership is seeking to build further state institutions and demonstrates its own legitimacy.

(3) The entity has declared formal independence or demonstrated clear aspirations for independence, for example through an independence referendum, adoption of a currency, or similar act that clearly signals separate statehood.

(4) The entity has not gained international recognition or has, at the most, been recognized by its patron state and a few other states of no great importance.

(5) It has existed for at least two years (Caspersen, 2012; Caspersen, 2009; Pegg, 1998) .

The situation of unrecognized states changed radically in 2008, when Kosovo declared its independence. This event is followed by the outbreak of the Russia-Georgia War, after which Russia (as well as some other states) recognizes Abkhazia and South Ossetia as sovereign states. These events illustrate that the current standards of recognition of a state are extremely vague. The recognition of Kosovo’s independence highlights the ambiguity of the criteria for recognized and unrecognized states, and the country’s independence can be considered as an impetus for the Russia-Georgia War and the recognition of both Abkhazia and South Ossetia. The Russia- Georgia War, moreover, has a significant impact on the problem of unrecognized states.

Unrecognized states seem to be a relatively recent phenomenon, especially prevalent in the post-Cold War period, though such cases have existed throughout history (Caspersen, 2012) . The recent unrecognized states tend to be self-defined but are affected and manipulated by the countries that support them. This paper suggests that we can see the merits of such states for the big powers, which are their main patrons in many cases and which are why they have come into existence.

This paper examines the factors of standing armies especially in or near unrecognized states and the gains of the big powers in maintaining unrecognized states. The term “big powers” here refers to the United States and Russia. Though the conflicts and ideology of the Cold War no longer exist, Russia and the United States continue to be rivals, especially since the former has recuperated some power with the rise of its petroleum exploitation. Thus, this paper focuses on the geopolitical strategies of patrons and their use of standing armies. It shows that unrecognized states have been convenient both for the big powers and for the governments of these states. It offers a new and significant approach to understand the relationship between the big powers and unrecognized states.

2. Unrecognized States in the Former USSR and Kosovo: The Precedent of Kosovo

First, although history is full of unrecognized states, the dissolution of the USSR and Yugoslavia produced a host of new cases. This phenomenon is related to the collapse of the two unions that had both adopted ethno-federa- lism, a political system that includes many ethnicities and religions; in fact, Soviet ethno-federalism recognized some members as titular nations. This system was also adopted in Czechoslovakia during the Communist period. In these cases, minorities constituted autonomous republics. However, some minorities feared they would lose their traditions, cultures, and autonomy within the system, and in the dissolution of each of these federations, they insisted on their rights. In this way, serious conflicts developed, resulting in ethnic cleansings that aimed at removing minorities. Some de facto states have also appeared in the former USSR and the Yugoslavia, and in some cases, patrons have helped minorities form and retain their status as unrecognized states.

A traditional rule in international law is the uti possidetis (“as you possess”) principle, whereby a territory or other property remains with the possessor at the end of a conflict unless otherwise provided for by treaty. If the treaty does not include conditions regarding the possession of property and territory taken during the war, then the principle of uti possidetis prevails. In other words, the existing borders of polities must be respected. Thus, the redrawing and changing of borders during the collapse of the USSR and Yugoslavia was not permitted; therefore, separation and independence of their minorities was consistently denied. Because of this principle of law, the international community has hesitated to recognize de facto states, especially when genocides and deportations have occurred and when force has been widely employed in independence struggles. The acceptance of such de facto states by foreign nations would set a bad precedent in that it would imply that they accepted the results of such ethnic cleansings, although even a change in borders or territories by force is not allowed by international law. As a result, the national ambitions of minority groups have led to unrecognized states, whose situations have remained frozen, creating what has been called ‘‘frozen conflicts,” as in the Russia-Georgian War of 2008. When violence frequently erupts, the terms “prolonged” or “protracted conflicts” are often employed.

Two kinds of unrecognized states exist in the former USSR and Yugoslavia. In the first, a former autonomous province insists on independence and becomes an unrecognized state. In the second, the people who desire the new state set the border intentionally to create a “region,” insist on independence, and become an unrecognized state. Table 1 outlines the distinctions between these two types of unrecognized states.

The long period of deadlock in the situation of unrecognized states changed somewhat in 2008, when Kosovo declared independence and was widely recognized. Further changes occurred during and after the Russia-Geor- gia War. Many countries recognized Kosovo’s independence, despite the complicated background of the war. As a result, in the Russia-Georgian War, Russia recognized Abkhazia and South Ossetia, the breakaway regions in Georgia, citing the wide acceptance of Kosovo as a justification.

The reason for the widespread recognition of Kosovo’s independence is still not clear, though the main actors, the United States and the EU, have said that Kosovo’s case is special and exceptional. In order to understand the situation, a look at the wider context of the declaration might be useful. Kosovo declared independence in 1991, but Serbia did not recognize the move. Sporadic attacks by the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA), a radical group, began in 1996, following frustration over Serbia’s refusal to recognize independence. Serbian security forces responded to the KLA attacks with increasing intensity. The level of the conflict escalated, until Serbia agreed to a cease-fire in June 1999 (after a few complications that drew US mediation in the fall of 1998). During this time and after the cease-fire, the international community did not react consistently to the Kosovo problem. From the beginning of 1990 to around 1998, the issue was regarded as a “Serbian domestic problem”, and Kosovo’s claim to independence was consistently ignored. The international community came to regard Serbia as the villain and Slobodan Milošević, then the president of Serbia, as the source of the problem. NATO (the North Atlantic Treaty Organization) intervened from March to June 1999. After the cease-fire in June 1999, the problem of Kosovo’s status was put off because those involved gave priority to peace-building efforts.

Then, in November 2003, the US government announced the Contact Group (CG) initiative, which set out a success timeline and promised a review of Kosovo’s status in mid-2005, so long as Kosovo achieved defined standards on governance and treatment of ethnic minorities before 2005. The United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) and the Kosovo autonomous government agreed to the “Standards for Kosovo” in December 2003. Negotiations then began in October 2005, at which point Serbia and Kosovo had also started to speak, with the mediation of the UN’s special envoy. Although no results were achieved through negotiations, the UN’s special envoy proposed the recognition of Kosovo’s independence, with the proviso that the international community would continue observation. However, Russia strongly opposed the proposal, which was subsequently not adopted by the United Nations Security Council (UNSC).

A few years later, on February 17, 2008, Kosovo declared independence again, a move that divided the international community. As of September 2013, 101 countries had extended recognition, including such powerhouses as the United States, the United Kingdom, and France. The reasons for the changed attitude of international actors, led by the United States, are not clear, though it seems that the change stemmed from political motivations. However, many states with ethnic or territorial problems, such as Russia, China, Sri Lanka, and some European states, opposed it. In addition, when accounting for the pattern of recognition, it would be well to recall that the EU is not monolithic and that some member states―e.g., Cyprus, Greece, Romania, Slovakia, and Spain―are against an independent Kosovo.

On July 22, 2010, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) issued an advisory opinion stating that Kosovo’s declaration of independence was in accordance with international law (hereafter, the ICJ opinion). The opinion

Table 1. Types of unrecognized states in the former USSR and the former Yugoslavia.

*Chechen Republic, Republic of Srpska, and the Republic of Serbian Krajina can be said to have been unrecognized states at one time, but are not currently.

said that independence did not violate Security Council Resolution 1244, which had been the basis for the UN’s supervision of the territory from the end of the 1999 war until the legal settlement, nor did it violate the Constitutional Framework. This opinion aligned with the longstanding view of many countries, such as those of the United States and many EU member states (Krasniqi, 2011).

The ICJ opinion may have justified the recognition of Kosovo’s independence, but a controversy remained as to whether the opinion was legal. Still, the ICJ opinion has become an important touchstone in thinking about recognition for Kosovo. At the same time, the opinion does not shed light on the legal value of the declaration of independence or the legal grounds of recognition. Oddly enough, Serbia called on the ICJ to rule on Kosovo’s declaration of independence. Nearly everyone, including Serbia, thought that the ICJ would support the Serbian position against independence. Though Kosovo was greatly encouraged by the ICJ opinion, Serbia did not change its negative stance. However, the United States and EU welcomed the ICJ advisory ruling. Then-US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, for example, saw the opinion as “decisive” support for the independence of the youngest Balkan Republic and urged all nations, including Serbia, to recognize Kosovo’s sovereignty. Catherine Ashton, the EU High Representative for Foreign and Security Policy, also welcomed the opinion and urged the authorities in Serbia and Kosovo to engage in a dialogue (Sofia News Agency, 2010) .

The question most germane to this inquiry is the following: Why was Kosovo’s independence declared legal? The US government has never given its reasons for recognizing Kosovo’s independence, although it did clarify that the people of Kosovo had the right to determine their political future, once “requisite progress” was made in achieving UN benchmarks by developing democratic institutions and human rights protections (Kim & Woehrel, 2008). The United States also noted that the last legitimate Yugoslav Constitution gave Kosovo the same legal right to self-determination as the other five of the six Yugoslav Republics (Croatia, Slovenia, Montenegro, Macedonia, and Bosnia-Herzegovina). Nonetheless, the administration of former Serbian President Slobodan Milošević disbanded the institutions of Kosovo and unilaterally changed the constitution to strip the autonomous regions of these powers in the 1980s (Williams).

Not all the international actors, especially those with internal ethnic problems, were persuaded by these arguments. Some accused the United States and the EU of supporting organized crime; they alluded to the KLA, which some labeled as a terrorist group and as the source of regional criminals, including a drug cartel (Chossudovsky, 2008) . In addition, many doubted whether Kosovo had matured enough to be recognized as a sovereign state.1 The officials of international organizations in Kosovo―such as the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK), the International Civilian Office (CIO), and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization Kosovo Force (NATO KFOR)―said in March 2011 that they could not leave for some time because Kosovo had not matured enough to be treated as a sovereign state. In addition, the situation of the northern municipality of Mitrovica, which has been divided between an ethnic-Albanian majority in the south and an ethnic-Serb majority in the north and whose northern part is the de facto capital of the Serb enclave of North Kosovo, became very serious after July 2011. Many international actors were involved, such as NATO, the EU, and the International Crisis Group (Freizer, 2001; Prelec, 2011) .

Within the fuzzy logic of unrecognized states, failed states are independent legally but do not function as “states”, whereas others are not allowed independence, although they possess the means (e.g., Taiwan); and still others have achieved recognition from many countries, like Kosovo. Until recently, the Montevideo Convention―a treaty signed in Montevideo, Uruguay, on December 26, 1933―on the Rights and Duties of States (henceforth, Montevideo Convention), has been the standard for sovereign states. Article 1 sets out the premise: “The state as a person of international law should possess the following qualifications: (a) a permanent population; (b) a defined territory; (c) government and; (d) capacity to enter into relations with the other states (Monterideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States, 1933) .

The countries that signed the Montevideo Convention were limited to the Americas (the USA and 18 South American states); however, the EU follows a similar position, which is set out in the principal statement of the Badinter Committee, where states are defined as possessing a territory, a population, and a political authority. The committee also decided that the existence of states was a question of fact, while recognition by other states was purely declaratory and not a determinative factor of statehood. Switzerland, which is not member of the EU, adheres to the same principle.

With the US and EU recognition of Kosovo, it became clear that the Montevideo Convention was outdated and that its concept of the state is apparently inoperable. Indeed, the international situation has changed dramatically, and some types of states have come into being―such as regional unions like the EU and unrecognized states―that were not considered in the Montevideo Convention. Therefore, no standard for legitimizing unrecognized states in international politics exists, and the issue tends to become a grey zone. Unrecognized states pose a danger, however, since they can embody lawlessness and settings for human and drug trafficking terrorism, and other infringements on human security. In addition, the possibility of conflict is always present.

The absence of clear standards for recognition seemed to be one of the reasons for the Russia-Georgian War as well as Russia’s recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia as sovereign states after the war, since Russia has opposed the United States’ involvement in international society. At the time, Georgian President Saakashvili accused the West of double standards. This conflict shows how the absence of clear standards for sovereignty can be useful in keeping unrecognized states at the bidding of the big powers. In the following sections, this paper will look at how unrecognized states function with these powers.

3. The Unrecognized States as Useful Tools for Every Actor

As King (2001) made clear in his analysis of four case studies (Trans-Dniester, Abkhazia, South Ossetia, and Nagorno Karabakh), each nation he looked at has gained some benefit from the existence of unrecognized states. These areas worked as smuggling centers, not only because of their unrecognized statuses, but also because their parent states gained profit in their black markets. For its part, the international community was simply eager to put in place a ceasefire, leaving when it was concluded and becoming indifferent to any genuine peace. Russia, meanwhile, had been making large profits from unrecognized states in a number of ways. As long as an area remained unstable, the Russian military could remain a player in a “peace-keeping operation” with international legitimacy. In addition, many actors in or around the unrecognized states derive a benefit from the existence of unrecognized states and have an interest in perpetuating the situation. These include top leaders, government officials, military persons, military companies, illegal merchants, and so on. The entire constellation of interests came about through the “weakness” of states. However, such states―like those that became independent when the USSR dissolved―are weak politically and economically, and such weakness has been expedited by Russia, which can then support such unrecognized states, both militarily and economically, or apply similar pressure to parent states2 (King, 2001) .

Since King (2001) published his research fourteen years ago, the situation of such parent states has radically changed. Azerbaijan, for example, has succeeded economically by harnessing its oil and natural gas resources, although its political situation remains far from democratic. Georgia and Moldova have been the most corrupt countries in the former USSR and, indeed, the most corrupt in the world since circa 2000. However, since 2000, they have democratized. In Georgia, the Rose Revolution occurred in 2003, putting Mikhail Saakashvili in as the nation’s president, amidst mass protests following a contested election. However, he became authoritarian gradually, though efforts have been made to promote transparency. In comparison, Moldova has also promoted transparency, as has Ukraine, which experienced the Orange Revolution in 2004.

Following the revolution, Ukraine became strongly pro-EU and accepted the European Union Border Assistance Mission to Moldova and Ukraine (EUBAM), which was launched on November 30, 2005, following a request made jointly to the European Commission by the presidents of the Republic of Moldova and Ukraine. This request was made because of illicit cross-border activity, including the trafficking of human beings and smuggling and other illegal trade along the 1222 km-long border between Moldova and Ukraine, a phenomenon not helped by the secessionist region of Trans-Dniester in Moldova (which lies adjacent to 454 km of the same border), over which the government of Moldova has no control. As a result, both governments were losing substantial amounts in revenue to organized crime.3

In this way, parent states have become much stronger than in King’s (2001) description, and corruption has intensified during the decade of EU cooperation. However, King (2001) did accurately describe unrecognized states as frozen in their relationships with the big powers, although the parent states have become stronger. As the lack of recognition is prolonged and even though parent states, such as Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Moldova, have become stronger, they would realize some of the many convenient profit sources that unrecognized states provide at the same time. In these cases, the unrecognized state can be classified into one of two categories: “Dust Box” or “Security Box”.

A Dust Box can be defined as an unrecognized state that is an obvious lawless area, in which illegal or anti- humanitarian activity takes place and is transferred. Trans-Dniester, for example, has been called the Russian armory because Russia has military bases there and in the neighboring Abkhazia and South Ossetia, which play an important role in Russian military policy. In addition, drugs, weapons, radioactive substances, and even human beings (especially children and young women) are transferred though unrecognized states. These states thus work as smuggling routes, which is especially serious in the unrecognized states of the former USSR. The Caucasus, for example, is a famous source of illegal drug smuggling; its location in Central Asia means it is an easy route to and from Afghanistan. Profits in this case go not only to those related to such illegal trade in the recognized states, but also to the people in the neighboring states and Western countries engaging in black market trade. Thus, unrecognized states often become a trash dump―hence the moniker “Dust Box”. The Security Box, on the other hand, describes a situation where in an unrecognized state is used strategically by powerful states, namely either old or new big powers. The next section looks at military bases in or near unrecognized states, and explores the Security Box as a paradigm that helps explain the mechanisms behind the persistence of unrecognized states.

To maintain its hegemonic power, a big state generally tries to maintain its position in diverse territories via standing armies. However, such standing armies have led to problems with the governments and people of the states in which they are placed (Calder, 2007; Hayashi, 2012) . In addition, the big powers have sometimes ignored the political situations of the states that host their standing armies and have been criticized for apply a double standard in these cases. This big-power policy in the unrecognized states can destabilize regions or create global instability. Thus, unrecognized states are sometimes seen as zones that maintain or put at risk national, regional, or global security, causing them to be labelled “Security Box”. The meaning of the relationship between unrecognized states and big powers will be explored in the next section.

4. Unrecognized States and the Military Bases of the Big Powers

Just as, in the post-Cold War period, a change occurred in the landscape of unrecognized states, the strategies of the big powers’ overseas bases have also changed. During the Cold War period, the Western Block―the United States and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)―and the Eastern Block―the USSR and Warsaw Treaty Organization (WTO)―became engaged in an armaments race, which included increasing overseas military bases. For the most part, USSR bases were situated in Eurasia, except in cases such as Cuba that were farther afield. These bases were largely closed down at the end of the Cold War; however, the bases established by the Western Block have remained open. This is partly because of uncertainty about future developments in Russia and the post-Soviet region. The strategy remained uncertain until the attacks on the US World Trade Center in New York on September 11, 2001 (9/11).

It is essential to note that a significant number of overseas bases remain in or near unrecognized states, such as the American base in Kosovo and the Russian bases in Abkhazia, South Ossetia, and Trans-Dniester. Given the shift in military priorities and the continued presence of bases in or near unrecognized states, the relationship between big powers and unrecognized states is analyzed here, with special reference to the United States and Russia.

In order to make sense of the relationship, it is first necessary to review the military policies and international attitudes of the United States and Russia. Since the end of the Cold War, the United States has significantly closed large military facilities in Panama, the Philippines, and Spain. These closures took place in the 1990s at the request of the host governments, leading to the shutting of 97 American foreign bases between 1988 and 1995. In terms of policy, US overseas bases took on numerous roles, which are listed below:

(1) Military

(2) Strategic functions

(3) Service and repair facilities

(4) Storage

(5) Training facilities

(6) Logistical staging post

(7) Surveillance base

(8) Coordination of tasks

(9) Collecting intelligence

(10) Facilitating C3 (Command, Control, Communications)

(11) Transport points for enemy combatants and terror suspects

(12) Detaining and interrogating suspects

(13) Diplomatic symbol

Alexander Cooley (2008a) argued that points (1) to (10) can be considered general uses for military facilities, but notes that points (11) to (13) have recently gained heightened significance. He cited the former Karshi- Khanabad (K2) airbase in Uzbekistan as one example of the importance of locations for the detention, interrogation, and transport of enemy combatants and terror suspects. Cooley (2008a) said, further, that bases act as a “diplomatic symbol” for American power. Thus, base agreements are also symbols of US political and social commitments to the host country (Cooley, 2008a) . It is this wider idea of a military base as a “diplomatic symbol” that seems the most interesting, and this paper suggests that the term is akin to “imperial ambitions.” Indeed, a not insignificant number of people have argued that US bases have been established in order to guarantee security for US oil and energy routes, ensuring the transport of oil and natural gas from the Middle East to the United States from the Cold War period to the present (Gerson, 2009; Fazi & Parenti, 2012; Lutz, 2009) .

The Pentagon’s current Global Defense Posture Review (GDPR), which outlines US policy on overseas bases, lays out two important points of action. First, it advises a reduction in the number and scale of Cold War style bases, such as those in Japan, Germany, and Korea. Second, it advocates a “lily pad” strategy, which aims to establish a global network of smaller and more flexible facilities in locations where the United States has not traditionally maintained a presence, including Africa, Central Asia, and the Black Sea Area (Cooley, 2008a) . Within this framework, the following types of military facilities are advocated:

(1) MOBs (Main Operating Bases)

(2) FOBs (Forward Operating Sites)

(3) CSLs (Cooperative Security Locations)

In addition to these, other locations could be established for support, including prepositioned sites, and en route infrastructure (ERI) bases. MOBs are conventional large bases, such as those in Japan, Germany, and Korea, and are connected to the FOB (Cooley, 2008a; Lachowski, 2007) .

The important point in this strategy is for the US power not to overwhelm the host countries. The United States, however, tends to be thought of as overwhelming by those who view it as imperialist; moreover, the problems of bases tend to be politicized, as in the case of Uzbekistan (Cooley, 2008a) . The case in Uzbekistan, I suggest, demonstrates the general trend for all countries with overseas bases. Such bases make it possible to leave a US military footprint all over the world, maintained at a lower cost than the large sites and exercising a strategic logic (Cooley, 2008a; Lachowski, 2007) . This and the following case, Kyrgyzstan, involve recognized states; however, I would like to emphasize the importance of standing armies for the big powers; such military forces create problems and tensions in recognized states.

In 2001, the United States was permitted to use the military bases of Kyrgyzstan (Manas) and Uzbekistan (Karshi-Khanabad), both of which are in the former Soviet realm. The agreement surprised the international community because Russia had thought of the former Soviet region as within its sphere of interest, which it continued to insist that NATO not violate.

However, the United States was forced to leave the Karshi-Khanabad base after the May 13, 2005, Andijan massacre―for which official numbers claim 187 victims, but the National Security Service puts the number at 1500―in which the United States was criticized for its violation of human rights. In addition, the plan to withdraw from Kyrgyzstan was announced in 2013, alongside its planned withdrawal from Afghanistan the year after. However, leaving Central Asia seems to go against the general trend, given that maintaining the FOBs remains advantageous for the United States, in particular because they are bases in the former Soviet bloc. The reason for withdrawal is not simple and involves the following contributing factors: first, Russia was no longer able to keep the United States out of Central Asia, particularly after it allowed US bases in Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan. Though Putin did not welcome the US military per se, he did adopt the rhetoric of fighting terror because it worked in Russia’s favor in dealing with the “Chechen problem”. Whatever honeymoon there was between Russia and the United States was short lived, however, and relations soured during the “color revolutions”, NATO expansion, Kosovo, the Russia-Georgian War, and so on. After the fall-out, Putin found no reason for the United States to remain in the region, and he put pressure on the American government to leave.

Second, after the United States announced its pullout from Afghanistan, the immediate and “exceptional” reason for remaining in the region was gone―namely the effective execution of the war on terror. Finally, Kyrgyzstan lent its weight to Russian legitimacy in the region, thus reducing American claims. Since 2005, Kyrgyzstan has sought Russian support in order to maintain stability, in particular to calm ethnic strife. Moreover, former Kyrgyzstan president Kurmanbek Bakiyev was forced to leave the country because he used the military base problem politically, playing both sides of the US-Russia divide and angering Russia. Eventually, Russia’s role in the country grew larger, and Kyrgyzstan has considered entering the Custom Union, indicating that it did not want or seek to maintain a US base on its territory.

While it is easy to recognize the new pattern of international base development, it is almost impossible to determine the number and location of new or current “lily pad” bases. The US Department of Defense publishes the Base Structure Report annually4 that gives detailed information on US domestic and foreign bases or military facilities. However, their numbers do not seem accurate because the most recent report does not include important FOSs and CSLs that hold a considerable number of American troops, including facilities in places like Kosovo. It also does not include some of the bases that America has established recently under “Plan Colombia,” which was started as part of the “war on drugs” policy. While focusing on Colombia, the program has also targeted Ecuador and has led to the opening of four FOLs in Latin America.5 The United States has bases in some 60 countries or regions, but even this may not reflect the real number. Indeed, the United States has made a so-called “Agreement on the Status of US Armed Forces” with 93 countries.

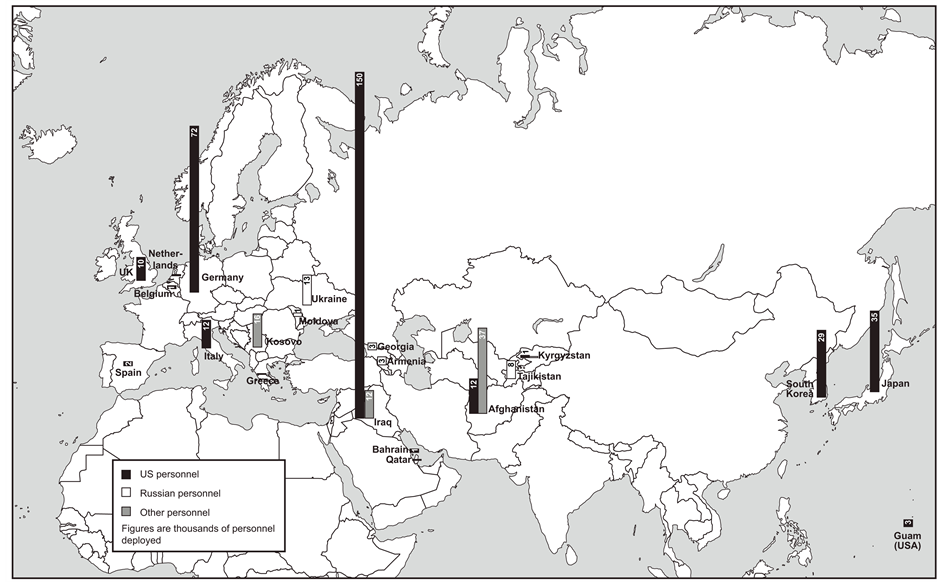

Secondary sources can be compiled to give a general picture of the existing military bases. Figures 1-3 and Table 2 and Table 3 show the details of US and Russian bases in unrecognized states (the American bases in Kosovo, Somaliland, and Taiwan6; and Russian bases in Abkhazia and South Ossetia) and near unrecognized states (American bases in Romania, near the Trans-Dniester; in Turkey, near North Cyprus; and in Israel, near Palestine; the Russian bases in Armenia, near Nagorno-Karabakh).7 These examples illustrate the relationship between overseas bases and unrecognized states. Russia, for example, can keep overseas bases in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, and under international law, the bases are in fact in Georgia.

Figure 1. Global US military bases (Source: Lutz, 2009 ).

Table 2. US overseas military bases.

**PRV ($M): Indicates the total plant replacement value (PRV) for all facilities (buildings, structures, and linear structures). This value represents the calculated cost to replace the current physical plant (facilities and supporting infrastructure) using today’s construction costs (labor and materials) and standards (methodologies and codes). The standard DoD formula for calculating PRV is as follows: Plant Replacement Value = Facility Quantity (1); X Construction Cost Factor (2); X Area Cost Factor (3); X Historical Records Adjustment (4); X Planning and Design Factor (5); X Supervision Inspection and Overhead Factor (6); X Contingency Factor (7). 1. Quantity of assets from the real property inventory database; 2. Construction cost as published in the DoD Cost Factor Handbook; 3. A geographic location adjustment for costs of labor, material, and equipment; 4. An adjustment to account for increased costs for replacement of historical facilities or for construction in a historic district; the current value of the factor is 1.05; 5. A factor to account for the planning and design of a facility; the current value of this factor is 1.09 for all but medical facilities and 1.13 for medical facilities; 6. A factor to account for the supervision, inspection, and overhead activities associated with the management of a construction project; the current value of the factor is 1.06 for facilities in the continental United States (CONUS) and 1.065 for facilities outside of the continental United States (OCONUS); 7. A factor to account for construction contingencies; the current value of the factor is 1.05. Pink: These sites have deep relations with unrecognized states. Note: This list does not include some of the most recently acquired US bases, such as those in Kosovo and Bosnia. Source: http://www.acq.osd.mil/ie/download/bsr/Base%20Structure%20Report%202013_Baseline%2030%20Sept%202012%20Submission.pdf (accessed 2013-11-3).

Figure 2. British, French, Soviet, and US troops based in Eurasia, 1990.

Table 3. Russian overseas military bases.

*The Northern Territory is internationally referred to as the “Kuril Islands” except in Japan. This area is the contested ground between Japan and Russia (or USSR) and Japan maintains that the Northern Territory is Japanese inherent territory. Pink: States which are the parent states of the unrecognized states or that have strong relations with unrecognized states. Yellow: Unrecognized states Gray: Gray zone internationally.

Figure 3. Russian, US, and other troops based in Eurasia, 2006-2007 (Source: Lachowski, 2007: pp. vi-vii ).

The United States maintains a large base, “Camp Bondsteel”, in Kosovo, although it can also be used for the NATO Kosovo Force (NATO KFOR) base (Film City). Camp Bondsteel is notorious as an almost secret large base that is serviced by American companies. It has American fast food shops, such as Burger King and Taco Bell, which serve the troops stationed at the base, as well as bars and restaurants, a gym, barber shop, a leisure complex, and so on; the companies brought into the military-industrial complex share the interests of the Pentagon and the military (Fazi & Parenti, 2012) . Within the camp, there is said to be an additional secret camp used to intern prisoners,8 in particular those with felonies and including those charged with crimes of terrorism, who have been transferred from the Guantanamo Bay detention camp in Cuba. Allegations have been made that the new camp was created because Guantanamo Bay had gained notoriety. While not a base in an unrecognized state, the situation seems similar to that of other new American sites. For example, in Romania, which has a US FOB, human rights groups have insisted that the CIA had operated a secret prison, prompting some Romanian parliamentarians to call for an investigation (Cooley, 2008b) .

American support for Kosovo’s independence (and Russian support for Abkhazian and South Ossetian independence), thus, may seem strange, but it can be easily explained. If Kosovo were independent, it would be very weak both politically and economically and would have to seek the patronage of strong states, such as the United States and the European countries. Kosovo would thus not likely oppose foreign bases. In particular, because its status would be weak, it would be indebted to the big powers that supported its claims.

5. Russian Policy

Following the collapse of the USSR and Moscow’s loss of influence over the region, Russia established its own overseas base policy. However, as the legal successor nation to the USSR, Russia closed most of its overseas bases, except those near its former Soviet space and in Syria. This policy is explained by the fact that Russia was overwhelmed by the fall-out of the Soviet collapse, including major financial difficulties; thus, Moscow could not afford to keep many overseas military bases. The successor state did fight to maintain as many strategic bases as possible; however, Russia sought both to maintain its power as a “big brother” and to organize its policies around ethnic problems and unrecognized states. It thus sought maintain an overwhelming influence over the region of the former USSR.

In 1994, after the last Russian troops pulled out of Estonia and Latvia, the Russian Federation held only 28 foreign bases or other installations in the former territory of the Soviet Union (in the newly independent post-Soviet states of Armenia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Moldova, Tajikistan, and Ukraine). By 2002, Russia had closed its intelligence installations in Lourdes, Cuba, and its largest naval base outside the WTO, in Cam Ranh Bay, Vietnam. Together with external politico-military reasons, domestic factors and budgetary constraints played a major role in these changes (Lachowski, 2007) .

Today, Russia maintains bases in the former USSR, with locations in Armenia, Belarus, South Ossetia (Georgia), Abkhazia (Georgia), Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Trans-Dniester (Moldova), and Ukraine (Crimea is now an illegal part of Russia), and has maintained bases in Azerbaijan, Georgia (mainland), and Moldova (mainland), although they were already supposed to be closed. The case of bases in Georgia and Moldova illustrates again the ease with which military bases can be established in other countries. In particular, Georgia and Moldova are young and weak states, and their positions in international society are not strong (King, 2001) ; they also receive only minimal support from other nations. Thus, Russia had assisted separatist parties in both states when they clashed with these governments. The assistance has led to the victory of separatist parties and Russian enforced cease-fire agreements, part of which involved establishing military bases.

Although the nations of the former USSR, such as Georgia and Moldova have resisted Russian bases, other countries have been willing to host them, including Armenia, which is next to the de facto and unrecognized state of Nagorno-Karabakh, within the border of Azerbaijan, where the chance of conflict remains elevated. Feeling threatened by this instability, Armenia makes use of the security provided by a Russian military base.

However, as noted, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine―members of GUAM―have tried to oust Russia from the bases on their territory. Attempts to remove the bases were especially strong during the democratizing periods of each nation. As predicted, the base problem was politicalized as host countries went through a democratizing process (Cooley, 2008a) . Such phenomena have been observed in the cases of Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine, since all three countries have tried to approach the EU and NATO, and Georgia and Ukraine developed democratic political movements without bloodshed, via the so called “color revolution”; they are expected to became countries with a “European Standard”. Georgia and Moldova both asked Western countries for help in closing Russian bases. The Russian military presence in the Caspian Sea and Caucasus area, which is near to the Middle East, however, has remained intact. This is partially because the area is confusing politically and ethno-nationally. Though the “Soviet Transcaucasus Military District” was dissolved in September 1992, and the Russian military left the South Caucasus, it returned later under the auspices of peacekeeping.

The Russia-Georgia “Military Cooperation Agreement” of October 9, 1993 allowed for the establishment of strategic bases in Georgia. Four more bases were created in 1995, after the 15 September signing of a second agreement: Vaziani near Tbilisi, Gudauta in Abkhazia, Akhalkaraki (settled as the 62nd military base), and Batumi (settled as the 12th military base). However, Georgia insisted on the closure of two out of these four bases, so Vaziani and Gudauta were gradually evacuated.

The Russian presence, especially in Georgia and Moldova, has been viewed as a serious problem by the OSCE because of the CFE treaty. At the OSCE Istanbul summit in 1999, a resolution was passed declaring that Russia should reduce its heavy weaponry in Georgia before the end of 2000, close the Vaziani and Gudauta bases by mid-2001, and then close the bases in Moldova by the end of 2002 (The Istanbul Document, 1999) .

However, Russia did meet the deadlines set by the agreement. Georgia requested that all Russian bases be closed by 2002, but Russia offered military assistance to Georgia and demanded, in return, the right to keep military bases in Akhalkaraki and Batumi for 15-25 years. Russia handed over the Vaziani base on June 29, 2001, and declared that it had dissolved the Gudauta base, finishing the withdrawal of troops in November 2001. That statement was not quite true, however, and the base problem between Georgia and Russia finally reached a stalemate between 2001 and 2004. One of the reasons that Russia tried to keep the bases in Georgia was a concern with US presence not only in Central Asia but also in the South Caucasus, where the United States had started training the Georgian military in 2002. Thus, the Russian position on military policy in the South Caucasus seems to have been established in this way. Russia tried to retain the Qabala Rader station in Azerbaijan (see footnote 9), and in 2002 it tried to remain at its Georgian military bases.

Further complicating the withdrawal, Russia requested financial compensation for the closed bases and then proposed the association of an anti-terror center with existing facilities for the West. At the time, then Georgian president Saakashvili, known as a radical anti-Russian politician, declared that Georgia would not host the new foreign military base. This statement put Russia at its ease. Subsequently, the Foreign Ministers of Georgia and Russia issued a joint statement on the cessation of the functioning of Russian military bases and other military facilities and also set the withdrawal of Russian forces from Georgia on May 30, 2005 (Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2005) . The Russian withdrawal of military facilities from Georgia was also postponed from June 2005 to sometime in 2008. The last stage of withdrawal was the evacuation of heavy equipment from the Batumi base and the closing of the Tbilisi headquarters of the Group of Russian Forces in the Transcaucasus (GRFT). Georgia assisted in the process of withdrawal and Russia promised not to replace or replenish the evacuated weapons and military equipment. In addition, three supplementary agreements were envisaged:

(1) Closure of the bases in Akhalkalaki and Batumi

(2) Establishment and functioning of an anti-terrorist center

(3) Transit through Georgian territory

The agreement is in line with the 1999 Istanbul Georgian-Russian joint statement, and this procedure was checked by foreign missions, such that of as Germany. Additional agreements were signed on the withdrawal of Russian forces from Georgia and on the transit of military equipment and personnel over Georgian territory March 31, 2006. All Russian military facilities were to be completely closed before the end of 2008 (Lachowski, 2007) .

Moldova has also sought to expel Russian military facilities. In 1994, its constitution declared that Moldova would remain neutral and not allow foreign military bases to enter the country. In line with the Istanbul document (1999) , Russia had to withdraw its military facilities and remove heavy weapons from Moldova by 2003. However, the nonattainment of the political resolution of the Trans-Dniester problem caused Russia to delay withdrawal of its remaining 1500 troops and the disposal of roughly 20,000 tons of stockpiled ammunition and equipment (2006 estimates). With Russia showing no intention of withdrawing its military power from Trans- Dniester, Moldova tried to solicit foreign support for settlement talks with Russia. The Russian military base in Tiraspol, the Trans-Dniester’s “capital,” houses the staff of the Operational Group of Russian Forces in Trans- Dniester (the former 14th Army) and two battalions, although it has no official base status. In October 2005, the enlarged “5 + 2” negotiating format (Moldova, the Trans-Dniester, Romania, Russia, and Ukraine, with the EU and the USA as observers) was agreed on in an attempt to overcome the deadlock. However, it was clear that Russia was not prepared to fulfill the Istanbul Agreement until a political settlement of the Trans-Dniester conflict had been reached and that Russia intended to keep its peacekeeping troops there indefinitely. Ammunition removal activities were also stalled (Lachowski, 2007) .

The halting of base removal, I suggest, is closely related to the Georgia-Russia war of August 2008. The war was started by a pre-emptive attack on South Ossetia by Georgia and escalated by the Russians with Abkhazian support for South Ossetia. However, there were many provocations by South Ossetia, supported by Russia, even before the outbreak of war. Russia began a war with Georgia in August 2008, just after Saakashvili sent his army to South Ossetia. The wide recognition of Kosovo and the problem of NATO seemed to provide Georgia with insight for the war. Russia prepared for the war in April 2008; it augmented its paratrooper force to 2542 men and conducted a large military exercise, “Kavkaz 2008”, in the Caucasus area in July 2008. The Russian army then intervened before the war, although Russia said that the actions were carried out by the “Vigilante corps of South Ossetia”, even though the troops involved were part of the Russian 58 Corps. Just after the war started, the Russian 58 Corps and airborne troops entered the Georgian territory officially with the aim of “saving Russian citizens”.

Actually, Russia seemed to be trying to keep its military bases in Georgia, apparently thinking it easier to maintain bases in the unrecognized states of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. The Russian withdrawal of military facilities from Georgia and the Georgia-Russian war led to the Russian recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia as sovereign states in 2008. This cannot be accidental.

The “Medvedev Doctrine” further supports the theory of a relationship between military bases, unrecognized states, and big power. Issued just after the Georgia-Russia conflict, it was meant to outline a new Russian diplomatic policy. The doctrine consists of five points:

(1) International law: “Russia recognizes the primacy of the basic principles of international law, which define relations between civilized nations. It is in the framework of these principles, of this concept of international law, that we will develop our relations with other states”.

(2) Multi-polar world: “The world should be multi-polar. Uni-polarity is unacceptable, domination is impermissible. We cannot accept a world order in which all decisions are taken by one country, even such a serious and authoritative country as the United States of America. This kind of world is unstable and fraught with conflict”.

(3) No isolation: “Russia does not want confrontation with any country; Russia has no intention of isolating itself. We will develop, as far as possible, friendly relations both with Europe and with the United States of America, as well as with other countries of the world”.

(4) Protect citizens: “Our unquestionable priority is to protect the life and dignity of our citizens, wherever they are. We will also proceed from this in pursuing our foreign policy. We will also protect the interest of our business community abroad. And it should be clear to everyone that if someone makes aggressive forays, he will get a response”.

(5) Spheres of influence: “Russia, just like other countries in the world, has regions where it has its privileged interests. In these regions, there are countries with which we have traditionally had friendly cordial relations, historically special relations. We will work very attentively in these regions and develop these friendly relations with these states, with our close neighbors” (Reynolds, 2008) .

In addition, Medvedev defined “priority regions” as those that bordered Russia, but in actuality, the definition is not limited only to these regions. Using this principle, Russia aimed to retain its influence in the former USSR and support the people who live in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, where about 90% of the people have Russian passports.

It can thus be said that unrecognized states are useful for Russia in its quest to maintain a strong influence in the former USSR. While Russia’s recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia as sovereign states seems to disprove the relationship between unrecognized states and the influence of big power via military base, it can be understood by the same logic of US support for Kosovo independence. That is, the newly independent states (Abkhazia and South Ossetia in this case) remain client states (to Russia in this case) with a debt of gratitude for independence. In addition, as a newly independent nation, it remains weak and cannot realize sovereignty or security without continuous support from patron countries. Therefore, newly independent states seem to be willing to accept foreign bases for survival.

6. Conclusion

Unrecognized states can best be understood as a legacy of the big powers. In the cases analyzed here, Russia and the United States―as modern-day big powers―need overseas military bases in order to maintain their influence over strategic parts of the world. Securing overseas military bases, especially large-scale ones, tend, however, to cause friction between the host region or government and the “big power”. However, unrecognized states or weak states (including newly independent states) can be easily managed by patrons or “big powers”, allowing them to establish their military bases. Such bases are even at times welcomed for the security guarantees that they can bestow on their host. This phenomenon illuminates an interesting facet within the field of big power research and shows the mechanisms by which the military interests of big powers are served and maintained via weak and unrecognized states.

Beginning in November 2013, Russian military forces entered the autonomous Ukrainian region of Crimea, where the majority of people were Russian or Russian speakers. In addition, the Crimea is important for Russia for historical and geo-political reasons. Russia uses the same logic as in South Ossetia and claims Russia has saved Russian people in the Crimea. The events of March 2014 only highlighted tensions; Russia annexed the special autonomous district of Crimea and Sevastopol, where a Russian military base was located. The annexation to Russia was approved in a referendum on March 16, in which 95.77% of votes approved the decision to become part of Russia. However, the referendum was carried out under military threat, and the people against the annexation boycotted the vote. Following this, the Crimean parliament declared independence on March 17 and expressed the hope that Russia would recognize Crimea as a sovereign state. On March 18, Putin announced that Crimea would be incorporated into Russia, and on the same day a treaty to that effect was established. Crimea became part of Russia, its citizens became Russian, Crimean time was changed to Moscow time, and the currency was changed to the Russian ruble. The Ukrainian interim government and Western countries had not recognized the referendum and incorporation, but Russia―at least in the short term―had succeeded in its de facto annexation.

Significantly, for the present analysis, Russia recognizes Crimea as a sovereign state, with Crimea being unrecognized for only a short period because it is likely that Russia wants to create the form of a sovereign state of the Crimea that will then merge with Russia, thus fending off criticism from the international community. In terms of an analysis of unrecognized states and big powers, it can be said that a new type of unrecognized state is created. Thus, the thesis of this paper has been demonstrably borne out in contemporary political affairs.

The difficulties inherent in resolving the problems of present unrecognized states extend to study about them as well. However, new unrecognized states not only continue to be formed but also have become a more or less frequent occurrence in this vulnerable world. Therefore, the need for further studies on unrecognized states is constantly growing, both to analyze the phenomenon and to seek resolution to the problem of existing unrecognized states. However, insofar as the problems of unrecognized states are not resolved, case studies will be limited, and it will be impossible to assess the true value of research into unrecognized states as well. To overcome such limitation as much as possible, researchers from various disciplines should collaborate in conducting many case studies of this problematic phenomenon.

Acknowledgements

This paper was based on a presentation at the AAASS (American Association for the Advancement of Slavic Studies) on a panel for the 45th Annual Convention of the ASEEES in 2013. I thank the discussant, Prof. Megan L. Dixon and guest from the floor, especially those who commented. In addition, Prof. Kimberly Martin and Prof. Catharine Lutz offered me great comments. I would like to thank all of them.

Cite this paper

YokoHirose, (2016) Unrecognized States in the Former USSR and Kosovo: A Focus on Standing Armies. Open Journal of Political Science,06,67-82. doi: 10.4236/ojps.2016.61007

References

- 1. Calder, K. E. (2007). Embattled Garrisons: Comparative Base Politics and American Globalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- 2. Caspersen, N. (2009). Playing the Recognition Games. The International Spectator, 44, 47-60. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03932720903351146

- 3. Caspersen, N. (2012). Unrecognized States. Cambridge, MA: Polity, John Wiley and Sons Ltd.

- 4. Chossudovsky, M. (2008). Kosovo: The US and the EU Support a Political Process Linked to Organized Crime. http://www.globalresearch.ca/kosovo-the-us-and-the-eu-support-a-political-process-linked-to-organized-crime/8055

- 5. Cooley, A. (2008a). Base Politics: Democratic Change and the U.S. Military Overseas. New York: Cornell University Press.

- 6. Cooley, A. (2008b). U.S. Bases and Democratization in Central Asia. Orbis, 52, 65-90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.orbis.2007.10.004

- 7. Fazi, T., & Parenti, E. (Directors/Writers) (2012). Standing Army. Documentary Film, Italy: Effendemfilm.

- 8. Freizer, S. (2001). Kosovo-Serbia: A Risky Moment for the International Community. Crisis Group Balkans Regatta. http://www.crisisgroup.org/en/regions/europe/balkans/kosovo/kosovo-serbia-a-risky-moment-for-the-international-community.aspx

- 9. Gerson, J. (2009). U.S. Foreign Military Bases and Military Colonialism: Personal and Analytical Perspective. In C. Lutz (Ed.), The Bases of Empire: The Global Struggle against U.S. Military Posts (pp. 44-70). London: Pluto Press.

- 10. Hayashi, H. (2012). Beigun Kichi No Rekishi [History of US military Bases]. Tokyo: Yoshikawa-Kobunsha.

- 11. King, C. (2001). The Benefits of Ethnic War: Understanding Eurasia’s Unrecognized States. World Politics, 53, 524-552. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/wp.2001.0017

- 12. Lachowski, Z. (2007). Foreign Military Bases in Eurasia: SIPRI Policy (p. 18). Stockholm: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

- 13. Lutz, C. (2009). Introduction: Bases, Big Power, and Global Response. In C. Lutz (Ed.), The Bases of Big Power: The Global Struggle against US Military Posts (pp. 1-24). London: Pluto Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511575600.004

- 14. Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States (1933). http://www.cfr.org/sovereignty/montevideo-convention-rights-duties-states/p15897.

- 15. Pegg, S. (1998). International Society and the De Facto State. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- 16. Prelec, M. (2011). North Kosovo Meltdown. Crisis Group Balkans Regatta. http://www.crisisgroup.org/en/regions/europe/balkans/kosovo/north-kosovo-meltdown.aspx

- 17. Reynolds, P. (2008). New Russian World Order: The Five Principles. BBC. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/7591610.stm

- 18. Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2005). Joint Statement by the Ministers of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation and Georgia. http://www.ln.mid.ru/brp_4.nsf/clndr?OpenView&query=31.05.2005&Lang=ENGLISH

- 19. Sofia News Agency (2010). US, EU Welcome ICJ Ruling on Legality of Kosovo Independence. http://www.novinite.com/view_news.php?id=118417

- 20. The Istanbul Document (1999). http://www.osce.org/mc/39569?download=true.

- 21. Von Glahn, G. (1996). Law among Nations: An Introduction to Public International Law. Boston: Allyn and Bacon Press.

NOTES

1Four important officials in the concerned international and regional organizations were interviewed in Kosovo on March 15 and 16, 2011; the officials wished to remain anonymous.

2The “parent state” refers to the state to which the unrecognized states belong legally or officially.

3EUBAM HP (http://www.eubam.org/en/about/overview).

4The related information can be accessed at: www.defense.gov

5They are recognized states; however, I introduce them because of the general tendencies of US military strategy.

6While not widely known, the photos of the US base in Taiwan were identified via online maps from Apple and Microsoft.

7Armenia is also a patron of Nagorno-Karabakh.

8Yomiuri Shimbun [Yomiuri Newspaper], November 26, 2005. This article appears in Le Monde, November 25, 2005. Many people in Kosovo have related the same stories to the author during field research in March 2011.