Journal of Mathematical Finance

Vol.05 No.02(2015), Article ID:56117,3 pages

10.4236/jmf.2015.52014

Cagan Effect and the Money Demand by Firms in China: A Nonlinear Panel Smooth Transition Approach

Fangping Peng1, Kai Zhan2*, Yujun Lian3*

1Business School, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China

2Finance School, Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, Guangzhou, China

3Lingnan College, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China

Email: *zhank97@163.com, *lianyj@mail.sysu.edu.cn

Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 21 March 2015; accepted 30 April 2015; published 5 May 2015

ABSTRACT

This paper examines the Cagan effect in China by using a panel smooth transition approach on the firm-level data. Our results reveal that the demand for money by firms relatively decreases for the high inflation period, because the firm anticipates further price increase that it seeks a substitute for money, supporting the presence of the Cagan effect in firms in China. A policy implication of our finding is that efficiently managing Inflation Expectation is necessary in China in stimulating the economy through expansion of the money supply.

Keywords:

Cagan Hypothesis, Panel Smooth Transition, Money Demand, Firm Level

1. Introduction

[1] argued that the demand for real cash balances will drop as inflation develops. Earlier studies focus primarily on the impact of expected inflation on money demand during hyperinflation period. However, hyperinflations are extreme events, which lead to a small sample problem for sound estimation. The problem has been moderated by examining the money demand schedule at daily frequency such as [2] . But the data sets about the money demand at daily frequency are usually unavailable in most developing countries such as China. Another strand of research abandons Cagan’s framework and opts for money demand schedules that allow for money substitutes, where elasticity increases as inflation accelerates and extends the sample to include the lower inflation period. Advancing that line, [3] argued that Cagan’s hypothesis might also hold in the deflationary period in which the demand for money will be higher during such period. [4] investigated the money-prices relationship under low and high inflation regimes in Argentina. Other recent studies include [5] .

In 2009, the obvious behavior of the public’s purchase of real estate against future price increase makes the Chinese government explicitly express that inflation expectation should be efficiently managed for the first time. A number of studies have explored the relationship between inflation and inflation expectation in China. However, little research has explored above relationship in the perspective of the Cagan money demand. Recently [6] has investigated the money-supply effect of inflation expectation in China by the model combining Cagan model and Lucas microeconomic rational expectation equation. What’s more, most of these previous studies examine demand for money by a linear model from macro view. In this paper, we adopt a panel smooth transition regression (PSTR) approach to study the demand for money by firms in China. Our method complements previous studies in three directions. Firstly, it overcomes the problems resulting from the sample-splitting regressions. Secondly, it reduces the potential endogeneity bias [7] . Finally, it allows heterogeneity of money demand for individual firms.

2. Model and Estimation

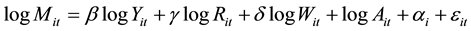

[8] and [9] define the money demand model as

(1)

(1)

where,  is the firm specific effects, and

is the firm specific effects, and  is the disturbance.

is the disturbance.  is the money holdings of firm i at date t.

is the money holdings of firm i at date t.  is the volume of sales of firm i at date t, as a measure of the scale of activity.

is the volume of sales of firm i at date t, as a measure of the scale of activity.  is the nominal opportunity cost of money and

is the nominal opportunity cost of money and  is the wage of the workers involved in the production of transaction services.

is the wage of the workers involved in the production of transaction services.  represents a type of productivity parameter that can be considered as an indicator of the firm’s degree of financial sophistication. Since the variables might contain unit roots, we rewrite the above model as:

represents a type of productivity parameter that can be considered as an indicator of the firm’s degree of financial sophistication. Since the variables might contain unit roots, we rewrite the above model as:

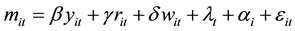

(2)

(2)

where ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  are the corresponding first-difference of the log variables in Equation (1).

are the corresponding first-difference of the log variables in Equation (1).  captures that time fixed effect which controls for economy-wide changes in financial sophistication [9] . According to [8] , we expect that

captures that time fixed effect which controls for economy-wide changes in financial sophistication [9] . According to [8] , we expect that  and

and . Our parameter of interest is

. Our parameter of interest is

Following [11] , we extend Equation (2) to a nonlinear panel smooth transition model:

where, the transition function

where, c denotes a location parameter,

Given the properties of the transition function, we have

3. Data and Results

3.1. Data

The firm-level data for the period of 1999 to 2007 are drawn from the annual surveys of Chinese manufacturing by the China National Bureau of Statistics. These annual surveys cover all state-owned enterprises, and those non-state-owned enterpricses with annual sales over 5 million RMB. This database has been widely used by previous studies, as it contains detailed firm-level information for manufacturing enterprises in China. Particularly, we are interested in the variables related to measuring firm financial holdings, average wage, total sales, and cost of capital. Table 1 describes the variables used in this paper. We exclude observations that do not follow standard accounting principles. To deal with outliers and the most severely misreported data, we winsorize all firm-level variables at the 1% level in both tails of the distribution.

3.2. Empirical Results

To begin with, we first test for linearity in Equation (3). According to the p-values for the LM tests [12] , the hypothesis of linearity can be rejected at the 5% level. The PSTR model is then estimated. The estimates of

The estimation results show that the coefficients on total sales and the nominal interest rate are both statistically significant and have expected signs for both the low and high inflation periods. The coefficient on wages is statistically significant and positive for the low inflation period, but not significant for the high inflation period, which is consistent with Cagan’s hypothesis.

Table 1. Variable definitions.

Table 2. Estimation results.

Note: ***, **, * indicate statistical significance of the difference at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively.

4. Conclusion

There are a relatively limited number of studies addressing Cagan’s hypothesis on money demand in China. This paper attempts to fill this gap by adopting a panel smooth transition approach on the firm-level data. Our results support the presence of the Cagan effect in China. In addition, it is found that the higher the inflation rate is, the stronger the Cagan effect is. The policy implications are obvious. Firstly, central banks should be more concerned with inflation expectation than they have been in the past, for inflation may have a significantly greater acceleration in the high inflation period. Secondly, once inflation expectation zooms up, central banks need to pursue aggressive and nontraditional monetary policy to reestablish suitable price anticipations by the public.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the foundation from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71201174 and 71002056) and Guangdong Natural Science Foundation (S2013010015019; 2014A030313577) for financial support of this research.

References

- Cagan, P. (1956) The Monetary Dynamics of Hyperinflation. In: Friedman, M., Ed., Studies in the Quantity Theory of Money, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Mladenović, Z. and Petrović, P. (2010) Cagan’s Paradox and Money Demand in Hyperinflation: Revisited at Daily Frequency. Journal of International Money and Finance, 29, 1369-1384. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2010.05.005

- Cargill, T.F. and Parker, E. (2004) Price Deflation, Money Demand, and Monetary Policy Discontinuity: A Comparative View of Japan, China, and the United States. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 15, 125- 147. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.najef.2003.11.002

- Basco, E., D’Amato, L. and Garegnani, L. (2009) Understanding the Money?Prices Relationship under Low and High Inflation Regimes: Argentina 1977-2006. Journal of International Money and Finance, 28, 1182-1203. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2009.06.008

- Minford, P. and Srinivasan, N. (2011) Ruling Out Unstable Equilibria in New Keynesian Models. Economics Letters, 112, 247-249. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2011.05.014

- Li, X.D. and Ji, Y.C. (2011) An Empirical Research on the Money-Supply Effect of Inflation Expectation When Managing Inflation Expectation in China-Based on Cagan Model and Lucas Microeconomic Rational Expectation Equation. IEEE 2011 International Conference on Management and Service Science (MASS), Wuhan, 12-14 August 2011, 1-4.

- Fouquau, J., Hurlin, C. and Rabaud, I. (2008) The Feldstein-Horioka Puzzle: A Panel Smooth Transition Regression Approach. Economic Modelling, 25, 284-299. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2007.06.008

- Mulligan, C.B. (1997) Scale Economies, the Value of Time, and the Demand for Money: Longitudinal Evidence from Firms. Journal of Political Economy, 105, 1061-1079. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/262105

- Lotti, F. and Marcucci, J. (2007) Revisiting the Empirical Evidence on Firms’ Money Demand. Journal of Economics and Business, 59, 51-73. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconbus.2005.12.003

- Choudhry, T. (1998) Another Visit to the Cagan Model of Money Demand: The Latest Russian Experience. Journal of International Money and Finance, 17, 355-376. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5606(98)00008-4

- Gonzalez, A., Terasvirta, T. and Van Dijk, D. (2005) Panel Smooth Transition Regression Models. Working Paper Series in Economics and Finance, No. 604.

- Van Dijk, D., Tersvirta, T. and Franses, P.H. (2002) Smooth Transition Autoregressive Models―A Survey of Recent Developments. Econometric Reviews, 21, 1-47. http://dx.doi.org/10.1081/ETC-120008723

NOTES

*Corresponding authors.