Open Access Library Journal

Vol.03 No.08(2016), Article ID:69756,16 pages

10.4236/oalib.1102800

EU Coordination Weaknesses: Transaction Costs

Jan-Erik Lane

Public Policy Institute, Belgrade, Serbia

Copyright © 2016 by author and OALib.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 6 June 2016; accepted 2 August 2016; published 5 August 2016

ABSTRACT

Both the Euroland and the EURO projects face increasing scepticism from several member states as well as nationalist movements. The call for economic reforms augmenting flexibility and work zest in EU member states meets resistance, as it poses threats to the specific European welfare state. The management of the great refugee crisis has led to fundamental questioning of the concept of “Europeanisation” as the commitment of the EU to humanitarian goals and universal human rights. Where lays the basic weakness of the inefficient and bureacratic European model of regional integration? Reply: Transaction costs.

Keywords:

Models of Regionalism, Coordination Mechanisms, Open and Closed Regionalism, Transaction Costs

Subject Areas: Political Economy

1. Introduction

In the charter of several regional organizations, there are rules that restrain state governments. These rules concerning human rights and rule of law are to be found both in the old type of regional organisation, such as the Council of Europe and the Organization of American States (OAS) and the African Union. The new regional organisations, like the EU and the ASEAN, or the UNASUR are heavily orientated towards economic affairs in a broad sense. They constitute coordination mechanisms for states to handle the increasing reciprocities, stemming from globalization process in both the financial and real economy. There are different models for these coordination mechanisms, mainly the EU model on the one hand and the Australian APEG model on the other hand. Let me spell out the logic behind coordination mechanisms, which may help us explain the UK choice on the so-called BREXIT option.

State Coordination Mechanisms: Autonomy versus Influence

Regional organisations line the EU and the ASEAN constrain their member states both politically and economically. When governments relinquish state sovereignty to regional bodies in the form of transfer of competencies, then the question of influence over decision-making in these regional bodies becomes crucial. When a nation like the UK feels that autonomy has been restricted too much by EU Law and that it plays a marginal role in EU policy-making, it would consider the BREXIT. But choosing state autonomy over influence in the EU may come with a price, as the UK or especially England now experiences.

2. Modelling State Autonomy and International Reciprocity

The growing international dependence concerns not only the economies. It pertains directly to the political system. Supranational bodies make recommendations to governments on how to frame laws regulating various aspects of the welfare state. There are strong tendencies toward uniform standards of employment conditions, pollution and so on. Moreover, the size of operations within modern well-ordered societies imposes narrow limits on government action due to the responsibility towards various nations incurred by such operations. The introduction of nuclear power plants affects other countries and ties countries together in cooperation to solve waste and storage problems. The growing political interdependence of states has resulted in the creation of a number of supranational regimes with various agreements on cooperation. Defence policies have been coordinated within a few major supranational bodies and within an international system of different pacts. The economic and political costs of warfare have grown to such an extent that even minor conflicts have repercussions on many states, particularly the Great Powers.

There are strong tendencies operating towards some form of control over military operations and political conflict between states; such efforts may create supranational bodies and complex agreements limiting state autonomy in this area. The staggering size of state involvement in defense policies, the tremendous effects on all systems of a war, the enormous risks connected with military defeat―all this works towards the creation of mechanisms for reducing risk, thus containing conflicts, creating possibilities for peaceful settlement, reducing the rate of increase in military spending, safeguarding small states, keeping hostile states or so-called rogue states within a system of checks and balances.

It used to be a dogma that sovereignty was a minimum property of the nation-state; if a state did not command sovereignty it perished. Some scholars have reinterpreted the classic idea of sovereignty, maintaining that the growing international reciprocity between states reduces autonomy and may even constitute a threat to democracy, as analysed by Dahl and Tufte [1] . Thus, it may be very true that reciprocity between states increases as a result of the growing interdependencies of globalisation, but the dogma of interdependence states that there is an inverted linear relation between reciprocity and autonomy. Actually, there are four possibilities (see Diagram 1).

These four cases are equally possible; autonomy may even be more vulnerable if a state isolates itself [2] . By means of reciprocity a state may safeguard a higher degree of autonomy than it would have in isolation. Economic interdependency may give a state a lot of resources by mustering trade and international cooperation instead of opting for autarchy. Political and military interdependency may be the only available means to a state against external threats from another state, seeking to make that state heteronomous. The interdependency dogma is wrong, because reciprocity maybe conducive to autonomy.

Even when interdependency reduces autonomy it is not self-evident that a nation should take counter-meas- ures. The costs of autonomy must be compared to the gains with regard to other values, like control over various resources. Modern states face the increasing challenge of separating those areas of decision-making where autonomy is a realistic goal from those where autonomy is not attainable at acceptable costs.

Governments may accept to transfer competencies to regional or international organisation in order to safeguard vital interests. These supra national organisation restrain the entire set of states, thus enhancing the

Diagram 1. Reciprocity and autonomy.

security of each one of them. Governments are especially interested in transferring competencies to supra national organisation when they not only restrain opportunism, reneging and beggar-thy-neighbour behaviour, but also when they can wield considerable influence over the decision-making in these bodies. This is the equation to be modelled here: Control = influence and autonomy, see Figure 1.

Autonomy cannot be maximized at the expense of all other considerations. A state that only seeks autonomy may become isolated and may suffer losses with regard to other values because of lack of influence. Few states manage to uphold total autonomy, even fewer regard it as a goal. The growing international interdependencies can only be accommodated if complete autonomy is abandoned. It would cost too much to cling firmly to the ideal of complete autonomy.

Even when interdependency reduces autonomy it is not self-evident that a state should take counter-measures. The costs of autonomy must be compared to the gains with regard to other values, like control over various resources. Modern nation-states face the increasing challenge of separating those areas of decision-making where autonomy is a realistic goal from those where autonomy is not attainable at acceptable costs, turning to regional or international organisation as a palliative.

The autonomy of the nation-state is a function of its sovereignty. International political systems including regional organisation restrict the autonomy of the nation state, while at the same time they provide mechanisms by means of which other sources of infringements on autonomy may be counteracted. Autonomy is a fundamental aspect of the state. Below a model is suggested that places autonomy in an equilibrium analysis of how demand and supply of autonomy interact with the demand and supply of influence and control. States may compensate for a reduction in autonomy due to for instance globalisation by seeking influence over regional and international organisations that are better suited to confront the challenges of increased interdependence.

Institutional autonomy of the nation state is linked with its sovereignty. It may be threatened from the environment by its neighbours or from within-anarchy. Much of what goes on in international polities is aimed at maximizing autonomy. Loss of autonomy versus environmental forces means loss of territorial independence, which may go as far as the complete absorption of one state into another. But recently states have looked for compensation for decreased autonomy and increased interdependencies through setting up regional organisations and strengthening international organisations.

To the state, institutional autonomy is a basic property. The demand for institutional autonomy concerns all aspects of the political territory. International regimes or regional organisations present a threat to the traditional autonomy of the nation state (sovereignty), but at the same time they provide mechanisms by means of which other sources of infringement on autonomy may be controlled, e.g. the market, multinational companies and external threats. Thus, state influence in regional or international bodies may compensate for a reduction in autonomy due to globalisation.

Figure 1. State autonomy and influence.

In a theoretical model, the demand for autonomy would be related to influence upon a regional or international organisation of which it is a member. The proposition states that there are basically two ways for the state to control the activity it engages in: either the action is autonomous or, if the action is heteronomous, the state may control it indirectly by means of influence over the group that decides the directives governing the action. To control the performance of actions means to decide the directives governing the action―what is to be done and how it is to be done. If an action is autonomous, then the state controls it. If an action is heteronomous, then the state controls it as far as its influence on the regional or international decisions governing the action goes. Thus, we have:

(1)

(1)

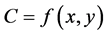

Assume that f(x, y) is two times diffentiable and f(x, y) = C constitutes an indifference curve. Moreover, we have:

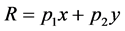

(2)

(2)

where p1 is the price unit for x and p2 is the price unit for y. The resource function states that a state faces a constraint on the amount of autonomy and influence that it may have or exercise. Though autonomy and influence belong to the type of entities which do not carry ordinary prices, the acquisition and employment of autonomy and influence carry costs for the state. For states, autonomy and influence require scarce resources, even when the price function for autonomy as well as for influence is a complex one and not easily measurable in terms of an index.

A state will allocate its resources R in such a way as to achieve as much autonomy as possible and to secure as much influence as possible. We find maximum control at the equilibrium point (x1, y1), when the resource function is tangent to an indifference curve. If R increases from R1 to R2 there is a new equilibrium; the new point of equilibrium (x2, y2) will be on another indifference curve C2.

A state has a certain amount of resources, R, at its disposal. It can allocate R between combinations of autonomy and influence in the following way―see Figure 2. The state considers C2 better than C1. It divides its amount of resources between autonomy and influence in an optimal way, depending on the cost for autonomy (Ca) and the cost for influence (Ci) respectively. It chooses influence x1 and autonomy y1 respectively, i.e. equilibrium G. Suppose that the state’s resource R increases. At the same time as the state increases its influence to x2, it also increases its autonomy to y2. The state is better off than earlier, i.e. it is in a new equilibrium H (Figure 2).

Figure 2. State choice: autonomy and influence.

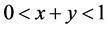

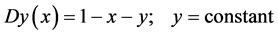

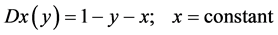

One may now introduce a control possibility line, i.e.

(3)

(3)

i.e. autonomy as well as influence have a highest value, and when the autonomy is high, influence is low, and vice versa. The control possibility line states that there are limits to the provision of autonomy and influence in a society, and that these two entities are interdependent, i.e. if the supply of one of the entities is maximized then the supply of the other entity cannot be maximized, and vice versa. By means of this assumption of a control possibility line, I define one demand function for autonomy and one demand function for influence:

We see that when x increases, then Dy decreases (y is constant). The same holds true for y and Dx. We may conclude that the demand for autonomy is a function of the supply of influence. In the same way we can derive that the demand for influence is a function of the supply of autonomy. Suppose that globalisation offers a low degree of influence as well as a low degree of autonomy to its various states (see Figure 3).

If a state finds itself at the point x1y1 in Figure 3, we see that both the demand for influence (x2, y1) as well as for autonomy is high (x1, y2). The situation is unstable and government will initiate a movement towards the line GH from inside the shadowed region. It seems that the seminal process of globalisationfavour point H, where influence in international and regional organisations should compensate for any reduction in state autonomy due to rising global interdependencies. Otherwise, the BREXIT that favours state autonomy at the expense of the costs of losing influence in the EU.

3. EU Model: Performance and Evaluation

One may understand that the overall performance of the EU during the last decade has resulted in a debate about the pros and cons of the European model of regional integration. The economic outcomes for many EU countries is disappointing, especially in the Southern parts of Europe. Why is economic growth meagre and unemployment high in several of the member states of the Eurozone? Could it be the case that the so-called EU model is somehow defective, not operating as hoped for? There were warnings from American economists when the EURO was introduced, but the debate about the failure of the EU model to create a dynamic area of regional economic integration should be extended to the entire EU area. In a comparative assessment, the EU model should be evaluated against other frameworks for regional integration.

One cannot find among the theoreticians of European integration any hesitance about the correctness of the framework chosen, neither with academic scholars like Scharpf, Schmitter, Wallace and Hicks or practical people like Schuman and Monet. Other countries and regions outside of Europe have chosen other models of regional integration in the period of globalisation. Could they have worked better for Europe?

Figure 3. Demand for and supply of influence (autonomy).

4. The European Coordination Mechanism: Ends and Means

It has been emphasized by the many commentators on the European project (federalists, anti-federalists, supra- nationalists, inter-governmentalists, functionalists, neo-functionalists, institutionalists, new institutionalists) that there was a strong intentional dimension behind the construction. In his most famous statement, Max Weber linked intentions (“Sinn”) with the actor, explaining:

“Jede denkende Besinnung auf die letzten Elemente sinnvoller menschlichen Handelns is zunacht gebunden an die Kategorien ‘Zweck’ und ‘Mittel’” [2] .

Scholars who disbelieve in the rational choice model in the social sciences would no doubt argue that the concepts of ends and means are not sufficient to explain the rise of the EC and the EU. It is true that the making of treaties constituted the basis for the European project, but there were also other forces―not always intentional―pushing for growth of the Europeans endeavours. Not denying the non-intentional factors and all the unintended and even unrecognized outcomes [3] , underlined by both new institutionalists like Johan P. Olsen and neo-functionalists like Philippe Schmitter, the actor focus of Weber offers a more convenient starting-point for explaining action [4] .

So we must ask: Which are (were) the objectives of the European model of regional integration, i.e. key goals and central means? One may answer by suggesting:

1) Peace and democracy;

2) Economic growth;

3) Institutional integration through bureaucracy and legalism;

4) Cultural promotion of European ideas and values.

I will not say much about goal 1, as it has been well accomplished. No doubt the goal 3 is partly a means to goal 2 and 4. I will first discuss the modes of institutional integration and then deal with economic growth in order to finish with cultural. Institutionalisation has been a most endorsed strategy in the EU project that sets this model of regional integration apart from other models employed elsewhere. The EU model has a formalistic bias, to say the least.

5. The Stylised EU Model: Bureaucracy

When comparing the EU with other regional organisations like the ASEAN, NAFTA, CARICOM, OECS, SADCC and MERCOSUR, one is struck by the central place of bureaucracy and law in the EU framework. The EU is an impressive colossus of institutions of two kinds:

a) The EU organisations in Brussels, Strasbourg, Luxembourg and Frankfurt;

b) EU Law, as the set of rules for European integration.

Turning first to the EU decision organisations, one may say that they have never overcome the critique of a lack in democratic legitimacy. Despite many reform efforts, the structure of decision-making retains the impression of supra-nationality, exercised by a small group of politicians and a huge bureaucracy that is basically not accountable to the peoples of Europe.

The peculiar structure of the EU organisations in Brussels, Strasbourg and Luxembourg as well as Frankfurt reflects the incremental construction of the EU from its EC beginnings and the Coal and Steel Union as well as the Euro-atom. It start as intergovernmental structures but have evolved into supranational institutions in a peace-meal fashion by successive reforms, responding to the democratic deficit critique. By and by, the Eu has become more supranational, almost to the point of constituting a “state”, as it were.

It is true that the setting up of arms control related bodies―Coal and Steel Union, Euroatom―was inspired by the supranational approach, in order to vest the governments involved of any possibility to go it alone. But the creation of the Council was definitely made in an intergovernmental fashion, which also holds for the Commission and the EU Parliament. The European Court of Justice had to be given supranational features, as court decisions have to be final somehow. Yet, the Court was restricted to specifically the set of rules enacted by EU treaties and Council decisions.

Inter-governmentalism in the EC was safeguarded by the upholding of the unanimity principle, or veto rule. In addition, the EU Parliament had only an advisory role and the Commission was basically just preparing decision options for the Council.

The institutional development of the EC into the EU with the Eurozone has been characterized by a strong preference for supra-nationality, not to be found or imitated among other regional organisations in the world. Thus, unanimity in the Council has been scrapped for qualified majority voting and the EU Parliament has been given decision-making competences. The democratic deficit has been counter-acted by the introduction of direct elections of EU parliamentarians as well as the creation of new offices, like an EU president and foreign minister. The trend towards supranational institutions has been combined with a drift of EU organisations to increase their competences in a tacit manner.

Despite a flood of publications on the political institutions of the European Community and thereafter the European Union, there has not been available a comprehensive interpretation of the European Commission until the volume by Kassim, et al. [5] . It will be the starting-point for the coming efforts at understanding the Commission at the centre of the EU fabric of political institutions, because it is a very good book. It combines many insights into politico-administrative theory with a broad based questionnaire to a targeted sample of some 4 000 out of some 12-14 000 officials (with a rough response rate at 40 per cent).

This joint effort by not less than 7 authors succeeds in handling the coordination problem, delivering some nice insights into the attitudes of these key placed EU officials. Thus, we are presented evidence to the effect that some often talked about hypotheses need rejection or revision. Thus, we have the following hypotheses about the Commission C seriously questioned:

− C as super government: less than 10 per cent adhere to the view of the Commission as the government of Europe;

− C as a coming federal state: less than 40 per cent endorse the philosophy of supra-nationalism;

− C as patronage: a small minority says that they were invited to apply for a job; similarly a minority states that political considerations do not trump administrative merits; yet, the data on networks tell a somewhat different story, as nationality is a strong element in the formation of these informal groups, so necessary for the function of the entire enterprise; moreover, many officials underline the advantageous salary and perks system as their motivation.

− C as closed bureaucracy: There have been several efforts at making the Commission a strictly meritocratic based structure; the data indicates partial success, as a majority of officials have long administrative or corresponding merits, but there is also a sizeable minority that has entered this structure on other merits.

− C as gender neutral or balanced: The male dominance is pronounced, despite efforts to increase women officials.

− C as leftist: The book finds convincing evidence that the Commission is centrist dominated, neither skewed to the right nor to the left; but interestingly, the more economical the tasks of the DGs, the more liberal the officials tend to be; the same tendency applies to the officials from new member states. Germany and France are underrepresented, surprisingly.

− C as inefficiency: In the own view, the DGs operate with a high degree of competence, legality and effectiveness. How matters stand in reality is another question, but one notes the majority support for reforms and the lukewarm attitude towards more of coordination/centralisation, especially has they believe the Commission has lost power.

6. Legal Integration

A major achievement of the EU is the creation of a new bulk of law―EU law. It comprises the rules―treaties, legislation, recommendations, case decisions, bureaucratic statutes and enforcement decision that the EU set of organisations operate with or implement. It is basically public law, regulating first the EU itself and second economic activity in the member states.

EU Law has quickly become one of the chief topics in the faculties of jurisprudence in Europe. It consists of both the political institutions and the encompassing regulation of the member states in so far as such rules concern the core of the EC activities, namely the Common Market and its four liberties: labour, capital, goods and services.

The creation in such a short time of a new bulk of law regulating economic integration in so many member countries is an enormous accomplishment of the civil law tradition. This is codified law, handed down in written documents supported by the sovereign Umpire of the European Court of Justice. Il is always pointed out that the expanding Court is a true supra-national institution in the EU fabric. However, it is confined in several ways. Firstly, the Court has to respect the delegation of competences according to the Treaties, although it has tried to enlarge its scope of power through interpretation. Secondly, there is the central principle of subsidiarity, reinforcing the position of the institutions of member states. The Court can surely strike down decisions by member states that violate EU Law, but whether it can change decisions by the for example the Constitutional Court of Germany is doubtful.

About EU law, one may simply say that it has developed into a huge framework of rules, making up volumes of various types of rules and decisions, amounting to a new form of law taught in the faculties in European universities. This is a unique form of regional integration, not imitated anywhere around the world. Necessity?

The EU regulation is to say the least a complex edifice with various kinds of rules enacted by the Commission, Council and Parliament, supplemented with massive legal interpretation by the Court (“cassis de Dijon” approach). Not only is there hard regulation and soft regulation, but in addition there is so-called variable geometry with rules applying in some areas but not in others, countries opting out as it were. No doubt this legal approach fits well with path dependency from the German-French legal family―the civil law method inherited from Roman law. The drawback is that EU regulation is unwieldy as well as difficult to apply in a transaction cost minimising manner. Often its existence is not always known or recognised by the actors concerned. And its growth has been spectacular, almost unstoppable even when supposedly constrained by the principle of subsidiarity.

7. Moral Integration: “Europeanisation”

Up until the migrant crisis and the influx of thousands of immigrants from the Middle East and Libya, there was much talk, if nor propaganda, about the exclusive commitment to universal values by the EU. Scholars even went so far as to measure the extent of “europeanisation” around the world and with other regional organisations. Nobody could understand and fully explain why universal moralism should be designated “europeanisation”. It is true that the EU emphasized the respect for human rights and personal integrity in its relations, internally and externally (for instance with Turkey). But the management of the migrant crisis turned quickly into such a disaster that the EU lost its moral high seat. So many men, women and children have drowned in the Mediterrean Sea, completely unnecessarily. And several member states reneged upon the policy commitments towards refugees from the destruction of the Syrian and Libyan nations. Policy coordination failed at the EU level and the implementation of support activities to the immigrants was ambivalent and hesitant.

Actually, the EU member states often suffer from a lack of skilled workers. The treatment of the migrants was therefore sometimes a “lost opportunity”. But it certainly fuelled the fear of Islam in several EU countries.

8. Real Economic Outcomes

Bypassing the goal of peace, ending centuries of war in Europe―a truly important objective, the EU has primarily set itself economic goals and pursued economical means. One may conveniently separate between real regional integration in Europe on the one hand and economic growth on the other hand.

a) Market integration

A most telling indicator on the extent to which the country economies in Europe have been transformed into ONE European economy is the reorientation of trade since the creation of the EC. Intra-European trade is now larger than trade between Europe and other continents (Table 1).

The expansion of trade in Europe, especially inter European trade led to general economic expansion, as measured by economic growth.

b) Economic Growth 1960-2000

The idea behind regional integration in Europe was not only to abolish the risk if war but also to enhance the capacity of European countries to compete globally. There was much talk about the future threat of South East Asia to European economic dominance, besides the US. The US saw the EC as a mechanism for trade diversion, but economic growth in European took off (Table 2).

The economic expansion during the period of the build up of the EC-EU was rather strong, giving the global impression that the special European model was a success, and could be emulate elsewhere in the world: “Europeanisation”. Besides economic growth, it promised the rule of law and democracy. However, in the early 21st century things took a different turn, especially with the financial disaster in the private sector in the US and the EU. The chief question in research today is whether the introduction of the monnai unique is to blame, at least to some extent.

Table 1. Trade within Europe against total European Trade: EU trade shares and growths.

Notes: 1 refers to EU6 (Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Luxemburg, Netherlands) from 1960 to 1969; 2 refers to EU6 from 1970 to 1973 and EU9 (EU6 plus Denmark, Ireland and UK) from 1973 to 1979; 3 refers to EU9 in 1980, EU10 (EU9 plus Greece) from 1981 to 1985, and EU12 (EU10 plus Portugal and Spain) from 1986 to 1989; 4 refers to EU12 from 1990 to 1994 and EU15 (EU12 plus Austria, Finland and Sweden) from 1995 to 1999; 5 refers to EU15 from 2000 to 2001; 6 refers to EU15 from 2001 to 2004 and EU25 (EU15 plus Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia) and EU27 (EU25 plus Romania and Bulgaria) from 2007 to 2008, respectively. Sources: Statistical Yearbook, Eurostat (1997) and Trade Policy Review of the European Union: A Report by the Secretariat of the WTO, WTO (2002), Unctad (2012), World Bank (2012). Laura Serlenga and Yongcheol Shin (2013) “The Euro Effect on Intra-EU Trade: Evidence from the Cross Sectionally Dependent Panel Gravity Models”; University of York.

Table 2. Economic affluence in european countries 1960-2014 (LN GDP).

Source: World Bank data Indicators, data.worldbank.org/World Bank national accounts data, and OECD National Accounts data files.

The economic expansion during the period of the build-up of the EC-EU was rather strong, giving the global impression that the special European model was a success, and could be emulate elsewhere in the world: “Europeanisation” as the model type of regionalism. Besides economic growth, it promised the rule of law and democracy. However, in the early 21st century things took a different turn, especially with the financial disaster in the private sector in the US and the EU. The chief question in research today is whether the introduction of the monnai unique is to blame.

c) Economic decline 2006-2013

The beginnings of the 21st century have proven to be a critical test for the economy of the EU and the EURO-zone. The wide disappointment in several countries and the increase in support for nationalist parties is a natural outcome of the worsening of the basic economic statistics, First, there has been very little growth in GDP per capita since 2006―see Table 3.

Table 3. GDP/capita in constant value (LN).

Source: World Bank data indicators, data.worldbank.org.

When compared with the corresponding figures for the rising giants―China, India and Brazil―in the global market economy, the economic developments in the EURO-zone are dismal.

Examining the rates of growth between 2009 and 2013, one discovers not only that the average rates are meagre for several EU countries, but also that growth rates differ in the North from the South. This North-South split in economic development has been much debated, as it indicates that the EU is not well integrated as well as that the EURO-zone is not an “optimal currency area”. In fact, countries outside of the EU entirely or outside the EURO-zone have done the best in Europe, with the exception of Iceland. Perhaps monetary policy is best left at the state level in systems of multi-level governance?

When growth is meagre or even negative, then labour salaries stagnate or even decline, relatively speaking. This fuels discontent, especially when combined with large unemployment.

d) Unemployment

The economies of several EU countries have been anaemic as a result of the financial crisis and the Chinese supply chock. It is visible in the high rates of unemployment, which ultimately leads to people posing the question about the entire EU framework: Cui bono? Again, it is the Southern countries of the EU that have been worst hit by mass unemployment, leading to staggering social costs (Table 4).

Table 4. Unemployment 2006-2012.

Source: International labour organization/world bank data indicators.

The European welfare state has up to this economic crisis provided reasonable protection, but it comes with a huge cost for governments. Yet, it has been cut down considerable in Greece, Spain and Portugal. The question is whether it is survival fit in a global market economy based on murderous competition between countries.

e) Central government debt

In Table 5, we take a look at the increase in the overall debt of the central governments in EU. In several countries, fiscal deficits year in and out have resulted in an almost doubling of the debt. In a few countries, the debt ratio to GDP is close to or even above 100 per cent, which can be regarded as the start of the politics of the debt trap.

It is little wonder that EU member states have opted not to engage in Keynesian policy-making, as it could be too risky. However, the austerity approach has been painful in several countries and hardly effective in any.

9. Summing up

In the debate about the ailing economy in several EU countries, especially in Southern Europe, there are two major themes:

Table 5. Central government debt 2006.

Source: World Bank data indicators/international monetary fund, Government finance Statistics yearbook and data files.

a) Need for structural reforms

Although it is never specified what is meant by “structural reforms’, it implies reductions in the public sector, both in its allocation parts and redistribution side. Given the strength of left-wing parties and the trade union movement, this is practically very difficult to achieve. The call for less of spending on welfare state programs sits badly with the strong increase in remuneration for CEO:s and the accumulation in private wealth, taking place the last decade. Result: transaction costs.

b) The EURO: Advantage or disadvantage?

When the Euro is blame for the economic decline of Europe, then the following arguments are adduced:

1) The Euroland is not an optimal currency area;

2) The Euro lacks the institutional foundation in the form of the necessary banking and budget requisites;

3) The Euro has a deflationary bias built into it, as it cannot be used in expansionary monetary policy;

4) The Euro started un excessive borrowing streak with especially Southern member states wasting “cheap” money on bubbles.

This is not the place to discuss these opposing hypotheses about the Euro and its effects. Partly they reflect different basic research paradigms like Keynesianism against monetarism.

What is undisputable is that the austerity policies conducted by EU member governments have NOT succeeded in bringing down the high debt/GDP ratios. In addition, the Euro has not weakened due to the Northern- Southern split in Europe. A high Euro has definitely made things worse for France, Spain, Portugal and Italy. Meeting the challenge from East and South East Asia―supply chock―with expensive money and a huge debt mountain has proved too difficult for many members of the eurozone. Result: transaction costs.

10. The European Project: Why the Special EU Model of Regional Integration?

When scholars analyse the European Project, they take the basic model of deep and closed integration for granted. From this starting-point, they advocate various changes in institutions or policy in order to reinforce this model. They never consider other models of regional integration, for instance the weak and open model. Why, then, did European regional integration need the strong model of deep and closed integration? One finds the explanation in the main theories of the European project. Thus, we have the following:

a) Federalist dreams [6] : Several scholars have approached the EEC and the EU against the blueprint of a federal model. Had the idea of an EU constitution been successful, federalism would have a strong foundation in the EU project. However, it failed miserably. The EU framework never came close to federalism, as it is emphasized that it is and remains a Union of Nation-States.

b) Functionalist fallacy [7] : Functionalism or neo-functionalism in various version claim that European regional integration was a MUST around 1950-60ies. This may be true, but as in all forms of functionalism, there is the logic fallacy of explaining of several structures with the necessary function that they all could fill. No doubt the ASEAN has contributed to regional integration in that area without copying the EU model.

c) Inter-governmentalist flaw [8] : The attempt at rebuttal for functionalism-supra-nationalism would make the European model more similar to other models of regional integration. They are all state centred in that their organisational framework underline the veto of the member states, focussing upon unanimity in decision-making and policy-making. So the EEC and the EU would be basically inter-governmental bodies. However, once the EU embarked upon qualified majority voting, it has no longer an intergovernmental structure.

d) Supra-national legitimacy deficit [9] : It is widely recognized that the EU has developed in the direction of supra-nationalism, when compared with the EC. Various devices such as unanimity voting in very important decisions, the principle of subsidiarity, etc. has put a brake upon the trend towards supra-nationality. Thus, the European Court has extended its competencies to include human rights, which is accepted only because the EU cherishes human rights. Yet, when the EU takes decisions against the will of member states, it opens itself up for the accusation of democratic deficit.

e) EU as European Empire [10] : Thia ambition has no doubt been driving some of the founders of this coorrdination mechanism, but little consensus and too much top heavy bureacracy has reduced the capacity of the EU to act, especially in foreign affairs. So few activities were launched to save the migrants, for instance. And Russia could not be contained.

f) EU as flawed institutional construction [11] - [13] : If EU needed more centralisation, two chamber legislative assemly and a real government, i.e. real Europe-wide federalsm, it would no longer be thrcordination me- chanism that a majority of citizens would approve.

These stylised models of the European Union does not identity the EU as merely a coordination mechanism. Instead, they all remind of the wrongful Balassa model of the “logical” steps in regional integration.

1) Following the Balassa Model

One can say the evolution of the European integration fits well the classical Balassa model [14] . He imagined five steps in regional integration processes, which one may remember today when the EU is in a deep seach of organisational identity:

− Free trade area or customs union.

− Internal market.

− Monetary union.

− Federal union.

In the late fifties and early sixties, Europe pondered over the means of regional integration, deemed necessary. Either one would use the EFTA model―free trade area―or the EC model―customs union. We all know that Europe embarked upon the EC model in order to end up with a currency union, vizEuroland for 2/3rds of the member states.

Although the organisational development of the EC or EU did not follow any straight line but experienced numerous crises, the logic of the Balassa model―ever deeper integration―applied up until the rejection of the constitutional proposal in 2004. This killed the final option, federalism.

Yet, the making of the Lisbon Treaty in 2009 meant that much of the constitutional proposals were enacted, but without asking the peoples of Europe. Thus, Finke, Koenig, Prokoksch and Tsebelis [15] find in their enquiry into the evolution of EU from 2004 to 2009 that: i) Giscard d’Estaing was most successful in turning a first round defeat to final victory; ii) The Lisbon Treaty is not a minor reform but the major overhaul of the EU political institutions.

The EU still does not have a constitutional framework and its popular legitimacy has not increased since the Lisbon Treaty in 2009. Yet, it is true that reforms could be made by taking them up from the rejected constitutional draft, again without popular acceptance.

With so many features from the Balassa ideal-types, what does it all add up to for the identity of the EU: What is it? When the economic outcomes do not match ambitions, electoral groups start considering a more national approach to globalisation.

It should be emphasized that none of the other regional bodies around the globe resembles the EU model. They are all intergovernmental bodies with small size secretariats and lacking legislation, law and a supranational court. European scholars have long argued that “Europeanisation” would be the best approach to regional integration, but is it really true?

2) “Palaces” versus “tents”

In the well-known article “Camping on the Seesaws”, a distinction was made between two strategies for building an organisation that will operate in a turbulent and changing environment (Hedberg, Nystrom and Starbuck [16] . Either one attempts to build up a stable palace that is strong enough to withstand any and all shocks from the environment. Or one puts up a tent here and there to be moved and transformed whenever necessary to cope with instability. The EU adheres to the palace type of regional organisation, whereas the APEC kind of regional organisation fits the tent type of regionalism. Both the European and the Australian model have its pros and cons.

The Australian model relies upon informal organisation, meetings and promises. It does not lead to more than the FTA:s or PTA:s, if anything. But the results are tents that may be placed here and there and taken down and replaced easily. Since the FTA:s are often cascadable, the FTA:s may successively lead to ever more free trade, helping the WTO ambitions. However, the EU had other goals besides promoting free trade, such as peace, democracy and the rule of law all over Europe.

The EU endeavours have reached the fourth stage in the Balassa logic of regionalisation, but with the currency union the economic difficulties of the EU model have become most visible: The Eurozone is a Palace that is not easily adapted to changes in the ocean markets, receiving cracks when it camps on the seesaws.

The Eurozone crisis is not over despite years of attempted reforms in a federalist direction. And the Euro is still too highly valued for a major turnaround in Southern Europe, including France. The US has successfully counter-acted the economic depression by so-called “Quantitative easing”, but the ECB is not really allowed to engage in such huge money printing that would lower the Euro in the same way as the US dollar declined to the benefit of American industry. Most of the Eurozone countries have done worse economically that other EU member states and countries outside EU, like Switzerland and Norway.

11. Conclusions

The model employed for regional integration in Europe―deep and closed integration―has been achieved by the use of massive formal organisation tools: large scale bureaucracy, the erection of EU law and the creation for supra-national political institutions. Result: Transaction costs.

The pioneers behind the EC-EU project (Haldstein, Monet, Schuman, Delors) like the key scholars above never considered to look for a model of regional integration outside of Europe. They were so to speak locked into the logic of the Balassa framework. Had they looked carefully at the opposite framework for regional integration―shallow and open regionalism―they may have shown more appreciation for the EFTA approach?

As things now stand, there has emerged a flat contradiction between economic and politics in the European project: New plans about reforms of the banking and financial sector pushes the EU in the federalist direction, while at the same time EU federalism has even less support than some decades ago. If the ECB (European Central Bank) is to play the same role in every aspect of monetary policy-making and financial control as the Federal Reserve, then this would probably require a Treaty change. One may dream of a quick-fix to the sluggishness of Euroland, like depreciation of the EURO [17] - [21] for instance by QE (printing money), but it is too risky, especially when structural reforms seem imperative. The EU as a coordination mechanism suffers from the weaknesses of deep and closed integration, compared with the Australian model of open and weak integraion (APEC). Its mode of functioning [22] - [25] results in very heavy transaction costs.

Cite this paper

Jan-Erik Lane, (2016) EU Coordination Weaknesses: Transaction Costs. Open Access Library Journal,03,1-16. doi: 10.4236/oalib.1102800

References

- 1. Dahl, R.A. and Tufte, R. (1973) Size and Democracy. Yale U.P., New Hvaen.

- 2. Weber, M. (1922/1985) Gesammelte Aufsätze zur Wissenschaftslehre. Johannes Winckelmann, Tübingen, 214.

- 3. Merton, K. (1956) Social Theory and Social Practice. Free Press, New York.

- 4. Touraine, A. (2013) La fin des societes. Seuil, Paris.

- 5. Kassim, H., Peterson, J., Bauer, M.W., Connolly, S., Dehousse, R., Hooghe, L. and Thompson, A. (2013) The European Commission in the Twenty-First Century. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- 6. Scharpf, F.C. (1999) Governing in Europe: Effective and Democratic? Oxford U.P., Oxford.

- 7. Schmitter, P.C. (2000) How to Democratize the European Union... and Why Bother? Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham.

- 8. Moravcsik, A. (1998) The Choice for Europe. Social Purpose and State Power from Messina to Maastricht. Cornell University Press, Ithaca.

- 9. Foellesdal, A. (2006) The Legitimacy Deficits of the European Union. Journal of Political Philosophy, 14, 441-468.

- 10. Colomer, J. (2016) The European Empire. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, Charlston.

- 11. Hicks, S. (2007) What’s Wrong with the Europe Union and How to Fix It. Polity Press, Cambridge.

- 12. Marsh, D. (2013) Europe’s Deadlock: How the Euro Crisis Could be Solved and Why It Won’t Happen. Yale University Press, New Haven.

- 13. Peet, P. and La Guardia, A. (2014) Unhappy Union: How the Euro Crisis- and Europe Can Be Fixed. Economist Books, London.

- 14. Finke, D., Koenig, T., Prokoksch, S.-O. and Tsebelis, G. (2012) Reforming the European Union: Realizing the Impossible. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- 15. Balassa, B. (2012) The Theory of Economic Integration. Routledge, London.

- 16. Hedberg, B.L.T., Nystrom, P.C. and Starbuck, W.H. (1976) Camping on Seesaws: Prescriptions for a Self-Designing Organization. Administrative Science Quarterly, 21, 41-65.

- 17. Feldstein, M. (2011) The Euro Zone’s Double Failure. The Wall Street Journal, December 16.

- 18. Feldstein, M. (2014) A Weaker Euro for a Stronger Europe. In: Project Syndicate, April 30.

- 19. Bergsten, C.F. (2012) Why the Euro Will Survive. Foreign Affairsl.

- 20. Hugh, E. (2014) Is The Euro Crisis Really over?: Will Doing Whatever It Takes Be Enough. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, Charlston.

- 21. Sinn, H.-J. (2014) The Euro Trap. Oxford U.P., Oxford.

- 22. Pisani-Ferry, J. (2014) The Euro Crisis and Its Aftermath. Oxford U.P., Oxford.

- 23. Pryce, V. (2013) Greekonomics: The Euro Crisis and Why Politicians Don’t Get It. Biteback Publishing, London.

- 24. Wallace, H., Pollack, M.A. and Young, A.R. (2010) Policy-Making in the European Union. Oxford U.P., Oxford.

- 25. Olsen, J.P. (2010) Governing through Institution Building: Institutional Theory and Recent European Experiments in Democratic Organization. Oxford U.P., Oxford.