Open Access Library Journal

Vol.02 No.09(2015), Article ID:68631,15 pages

10.4236/oalib.1101756

The Dynamics of Policies and Practices of Labour Contracting in the Nigerian Oil and Gas Sector

Hakeem Adeniyi Ajonbadi

Department of Business and Entrepreneurship, School of Business and Governance, College of Humanities, Management and Social Sciences, Kwara State University, Malete, Nigeria

Email: ajons2003@yahoo.co.uk, hakeem.ajonbadi@kwasu.edu.ng

Copyright © 2015 by author and OALib.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 24 August 2015; accepted 10 September 2015; published 16 September 2015

ABSTRACT

This study critically examined the dynamics of the policies and practices of labour contracting within the Nigerian oil and gas sector as operated by some selected multinational organisations, namely: Mobil, Shell and Chevron. The study examined the nature of labour contracting, how and why it was adopted; and the implications of MNCs using such policies and practices in managing Nigerian workers. The study shed light on labour contracting arrangements and emerging employment relationships, as well as tensions among workplace actors. The research methodology was qualitative and was essentially driven by a subjective philosophy. It has an ontological undertone embedded with social constructionist approach. The target population for the study, therefore, was all the randomly selected contract workers of the three MNCs, the contractors of the user firms, and the two trade unions―NUPENG and PENGASSAN who were given survey questionnaires to complete and were engaged in semi-structured interviews. The study found that there are increased tensions in the working relationship. Other findings from this study include: the challenges that come with the entry point (recruitment); pronounced disparities in the remuneration packages between contract staff and permanent employees; contracted labour being faced with poor working conditions; and increase in the precarious nature of job security.

Keywords:

Labour Contracting, Policies, Practices, Multinational Corporations, Employment Relations

Subject Areas: Human Resource Management

1. Introduction

The Nigerian oil and gas industry is heavily dominated by multinational corporations (MNCs) whose recruitment and selection are assigned to different levels of management. Organisations vary, as to which level of management has responsibility for the recruitment of certain grades of employees. Given that the population of Nigeria is over one hundred and seventy million [1] making it the most populous African nation, with discreditable unemployment statistics, the country is vulnerable for exploitation by MNCs in terms of cheap labour [2] . There is an obvious disparity in the conditions of service, including remuneration, benefits, and job security between contract workers and permanent workers. This often heightens tensions and creates insecurity within the working environment [3] . Thus, the MNCs in the oil industry capitalise on the comatose nature of the unemployment in Nigeria, paying salvage wages, and widening the gap between contract and permanent workers [4] .

Labour contracting in the oil sector in Nigeria is perceived by the trade unions as a social phenomenon and a hydra-headed monster in labour relations. Contract staffing in the industry was seen as a deliberate policy of the MNCs who created it in place of permanent labour employment [5] . This is the placement of workers as temporary employees on jobs that are routine, continuous and permanent in nature. There are various nomenclatures used to describe labour contracting, including labour contract workers, temporary staff, service contract workers, direct hire, body shop, and fixed time contract, among others [3] . Whatever the name given, the bottom line is that these workers are not on the user firms’ payroll and are therefore paid low wages, and hired and fired at will by the service providers/contractors [6] .

The MNCs in the oil and gas sector contract out a large portion of their workforce to labour contractors to provide services to the companies (user firms) and pay the contractors service handling fees or commission; notwithstanding the continuous, routine and permanent nature of the job. The principal companies (user firms) in most cases employ these categories of workers, supervise their conduct and determine their salaries, but only transfer payment to the labour contractors [7] .

With the increasing use of labour contracting, there is a greater integration of this approach into the production process. This tends to have changed employment practices and how workers’ rights are exercised [7] . Whilst organisations are quick to advance arguments in support of this approach in terms of reduced labour costs, employment flexibility, and increased productivity, their antagonists see things differently [8] . In their view, the organisations have contributed to reduce a continuous increase in the unemployment rate, particularly for those from ethnic minorities [9] . On the contrary, those arguing against the use of this precarious employment contract consider that this approach increases job insecurity, pays low wages, keeps the contracted workers in poor working conditions, and increases tension among all of the parties involved―the user firm, the contractors, the contracted workers, the permanent workers, their trade unions, and the government [10] .

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Conceptual Understanding of Organisational Flexibility and Labour Contracting

Flexible employment has increasingly become a focal point of discussion and dispute among scholars, practitioners, politicians and the public of many countries. It is no longer in doubt that managers have strong concerns in favour of an in-firm flexibility and internally-divided labour market for reasons of maximising profit, developing an ability to respond to changes in market conditions and control or better manage its workforce [11] . Flexible employment policies are tactical tools in the hands of employers and managers, used in designing control systems at work. For Serrano [12] , flexible employment policies can be categorised as one of the four key guiding principles of human resource management―the others include the incorporation of human resource management issues into strategic plans, high commitment and high quality. Hatton [8] argue that flexibility can be viewed as an aspect of strategic HRM adopted by organisations to strip out jobs which do not contribute directly to production. Bamber et al. [13] , point out that concern for flexibility has arisen as a response to issues relating to globalisation, increased market volatility, uncertainty, acceleration and pervasiveness of technological change, and the intensification of international competition. The debate on flexibility, as proposed by Atkinson [14] [15] , is akin to the notions of the dual labour market theory.

Specifically, flexible employment refers to employees or workers on precarious market-mediated contracts such as short-term, part-time and quasi employment which are managed by business-related contracts such as sub-contracting, the use of self-employed independent contractors and labour contracted workers [16] . Flexibility has come to be seen as a solution or cure for organisational inefficiencies and a policy of economic good, in the sense that it helps in the creation of jobs [17] - [19] .

Atkinson [14] , who espoused the flexible firm model, suggested that, as employers reorganised their internal labour market, they were tending toward the division of the workforce into a two tier market of core and peripheral. Atkinson’s thesis on flexible firms is akin to the notions of the segmented labour market theorists, that the flexible firm is an in-house divided workforce: a “core” workforce of stable, skilled workers with access to secure employment and prospects for career growth. The secondary segment of insecure employees, on the other hand, is made up of employees who enjoy less security as they are in and out of contracts due to limited contractual employment, i.e. short-term contracts, part-time contracts or government training schemes [20] . Such workers are open, to a considerable extent, to insecurities in the labour market. In this group, workers share common traits: they are increasingly insecure, often poorly paid, supposedly meant to be semi or non-skilled but more often are skilled workers vulnerable to the volatility of market forces.

There have been several objections to the flexible firm approach. First, it is not clear if the flexible firm model describes reality or whether it is another approach employers may use to control labour. On one occasion, Pollert [21] pointed out that Atkinson appears to argue that it is neither an example of a type of company, that already exists, nor ideal for what firms could achieve; rather, it is an investigative tool for examining the various changes taking place at the workplace. On the other hand, Battisti and Vallanto [22] insist that flexibility is no longer an analytical happening in employment. They points out that the organisational flexibility concept is being contested on different fronts. They further identifies the following as part of the key issues that have emerged: “What forms of labour flexibility are being sought by organisations?”; “What are the reasons for such changes?”; “Is flexibility being developed as a strategic response to changes in market conditions?”; “What are the consequences of increased flexibility?”; and “Are they consistent with the emphasis on ‘high commitment’ within HRM?” [23] .

For Pollert [21] , other problems with the flexible firm model include the inability of the proponents to adduce convincing evidence to prove that companies are adopting a flexible strategy. There is the inability to define convincingly what they mean by “core” and “periphery” or the premise on which the distinction is made. Much of the recent debates of the flexible firm have centred around the empirical evidence for the influence of the core-periphery thinking on organisations. Labour contracting and the precarious employments associated with it are often characterised by uncertainty which introduce complexities into the employment relationship [24] .

The practices found among the oil MNCs in Nigeria are not different from what is described. Whereas permanent workers within the core segment of the MNCs are protected by the two trade unions in the firms, workers within the periphery segment are not protected. The two trade unions referred to are Petroleum and Natural Gas Senior Staff Association of Nigeria (PENGASSAN), which represents the senior and middle management workers, and Nigerian Union of Petroleum and Natural Gas (NUPENG), which represents the junior workers. The MNCs studied do not accord these unions recognition to bargain for workers within the secondary workforce. For example, the PENGASSAN and Shell Nigeria have an agreement that covers only workers in the core (4500 permanent workers) of Shell Nigeria [25] ; yet there are over 50,000 contract workers and this excludes all expatriates [26] . It is important to note that, the oil MNCs operating in Nigeria vehemently opposed the formation of a trade union in August 1978 [27] . These findings are similar to Redman [28] who reported that 54% of employers were neutral about their employees being members of a union while 17% absolutely did not favour the employees being members of a workplace union.

The impact of the union’s inability to protect contract workers appears to have extended the frontiers of influence or role of the ethnic associations who, through influential job gate-keepers or personalities, negotiate recruitment, promotions and protect jobs of its members within the MNCs in Nigeria. The role being played by ethnic associations has weakened the trade unions. This is because multinational oil companies’ management are harnessing the use of ethnicity as a divisive instrument in their control of labour [25] . There is a consensus among workers, union officials and scholars that the pursuit of a large secondary workforce via precarious employment contracts for reasons of profit or control has come with a cost [29] [30] . Non-cordial relations at work have been an issue accompanying the large scale use of insecure workers.

2.2. The Nigerian Labour Market and Labour Contracting

Nigeria has emerged as Africa’s largest economy with 2013 GDP estimated at US $502 billion after the “rebasing” exercise in 2014 [1] . Oil has been a dominant source of government revenues since the 1970s. Regulatory constraints and security risks have limited new investment in oil and natural gas, and Nigeria’s oil production contracted in 2012, 2013 and 2014 [31] . Nevertheless, the Nigerian economy has continued to grow at a rapid 6% - 8% per annum (pre-rebasing), driven by growth in agriculture, telecommunications, and services, and the medium-term outlook for Nigeria is good, assuming oil output stabilizes and oil prices remain strong. Despite its strong fundamentals, oil-rich Nigeria has been hobbled by inadequate power supply, lack of infrastructure, an inconsistent regulatory environment, a slow and ineffective judicial system, unreliable dispute resolution mechanisms, insecurity, pervasive corruption and alarming unemployment rate.

In Nigeria, the unemployment rate measures the number of people actively looking for a job as a percentage of the labour force. Unemployment rate in Nigeria averaged 15.97 percent from 2006 until 2015, reaching an all-time high of 24.20 percent in the first quarter of 2015 and a record low of 5.30 percent in the fourth quarter of 2006 [1] . Economic diversification and strong growth have not translated into a significant decline in poverty levels as over 62 percent of Nigeria’s 170 million people live in extreme poverty [1] .

The oil unions’ decade-long fight for higher wages, job security, and benefits has occurred while corruption, pollution, and corporate indifference have eroded job growth and living standards in the rest of the country [2] . As a result, Nigerian oil workers are vulnerable to a new kind of attack―quiet but more potent through an industry-wide shift away from regular, full-time work toward forms of cheaper temporary labour and short-term contracting. This process, called “casualisation” or labour contracting in Nigeria, attempts to lower corporate costs while breaking workers’ strength―pushing oil workers out of an industry they built and pitting them against one another in a struggle for jobs in a country where an estimated 71% live on less than $1 per day [32] . This again poses a challenge for trade unions as contracted labourers have short term employment contracts, and, as such, do not often feel the need to belong to a trade union. This weakens the strength of the union [33] . The rise of casual employment is a global trend [10] [27] . The Nigerian oil industry is just the latest snapshot in a larger global picture where decent work as a path to broad-based development is rejected and more jobs are created through outsourcing or labour agencies/contractors. Work is often temporary, with uncertain wages, long hours, and no job security [34] . The push toward casualisation in Nigeria is evidence of a continued effort by the government and corporate elites to maximise oil profits at the expense of a long-term job policy, transparent governance, and shared economic development [3] .

The unions are not barred from organising secondary workers in the firm; however, the evidence suggests that union officials have not concerned themselves with organising this group of workers. Since a large proportion of the workers are located in the secondary workforce, the inability of the unions to organise and effectively represent this precarious group of workers has resulted in the unions being weak. The lack of a collective representative voice for periphery workers in the multinational oil companies in Nigeria is in negation of section 1 of the Nigerian Trade Union Act 1973. This legislation allows unions to organise and represent all kinds of workers in a firm.

2.3. Methodological Approach

The research methodology is qualitative and was essentially driven by a subjective philosophy. It has an ontological undertone embedded with social constructionist approach. The target population for the study, therefore, is all the randomly selected contract workers of the three MNCs under consideration―Mobil, Shell and Chevron. The samples in this study were selected on purposive bases. There were three samples. The first was selected among the contracted employees; the second category was the contractors and the third was the trade union officials in the oil industry. 300 questionnaires were distributed and 219 were returned, representing 73 percent response rate. In validating this survey, 68 participants were interviewed and obtained data were interpreted with the use of NVivo software. The NVivo is perhaps the most widely used and potent computer software for the analysis of qualitative data for management scientists [35] . With the use of this powerful software, all the questionnaires’ data for this research study were defined. Given the nature of the data and the research questions, a descriptive statistical method that includes frequencies and percentages were used, in order for easy clarification.

2.4. Results, Findings and Discussions

2.4.1. Labour Market Entry Point for the Contractors and the Contracted

The quality of an organisation’s human resources is said to depend on the quality of its recruits [36] . Recruitment is the process of attracting and finding supposedly capable hands for a job; the process will begin when new recruits are sought. The complexity of international recruitment by MNCs compounds an already difficult recruitment environment. Thus, as more firms become international, attracting foreign managers to work for domestic firms and finding domestic workers to join foreign organisations increases the complications [37] .

Labour contractors are a significant group in the labour market of MNCs operating in the Nigerian oil and gas sector. This is because Shell, Mobil, and Chevron managers have increasingly outsourced a variety of their organisational task activities to labour contractors. A contractor with Mobil pointed out that:

“It amounts to fallacy for anyone to conclude that the MNCs find it easy using contract workers to carry out their tasks. The process of engaging a contractor with any of these firms is not so straight forward, and usually expensive. The user firms are required by law to advertise for contractors and screen them before the contracts could be awarded. This is by no means cheap. And when you look at what is contracted out, they range from the very technical aspects of production to the mundane tasks of driving and catering services”.

However, from the interviews conducted, participating contractors pointed out that not all jobs are advertised, and a number of contracts have been awarded to local communities or individuals in local communities with the prevalence of nepotism, ethnic connection and favouritism, without necessarily going through the formal pro- cesses. Contractors with the three firms studied pointed out that the process of bidding to fill vacancies in the MNCs is a highly subjective competition. A contractor with Chevron pointed out that:

“Biddings can be won or lost before the management even places such jobs in the market for a bidding exercise; a lot depends on how highly influential your contact is. If the manager or contact person is influential, you will get the job. The bidding exercise is nothing but an attempt to fulfil all righteousness as it is often a mere formality. This is because the managers have already agreed on who to select”.

It might be safe to assume that one of the challenges with international recruitment and selection processes is that they are often aimed at traditional, standardised and generic hiring methods, although with some cosmetic colourations. Budd and Spencer [38] pointed out that, at each managerial level, managers may have similar responsibilities, but with different activities in size and scope. This is true when considering recruitment at international levels by MNCs who must appreciate the local challenges and the need for native knowledge.

The use of positive discrimination or the arbitrary way in which certain contracts have been shared has irked some individuals, and created a lot of heated problems among communities competing for a share of labour contract jobs within the Niger Delta oil region in Nigeria [39] . To underscore the significance of the ethnic groups, particularly within the oil producing regions in Nigeria where the activities of militants are more pronounced, came the voice of a group called the “Itsekiri Patriots”. The group unequivocally came out lamenting the discriminatory manner in which contracts were awarded to non-locals while at the same time favouring one community over the other. The community is one in which Chevron primarily operates, and their views were well articulated in a conference held in January 1999. They argued that:

“The Itsekiris are hardly represented in the workforce of oil companies much less at the management levels, especially in Chevron Nigeria Limited, which has the bulk of its production in Itsekiri land… Even in Ugborodo and Ogidigben, its operational base has no electricity, water and motorable roads. Indigenes still depend on rainfall and shallow wells as sources of drinking water. In terms of employment opportunity, the Itsekiris are the least to be considered and the first to be sacked, usually for no just cause”.

Beside the allegations of neglect and systematic exclusion of local communities in Itsekiri, Chevron was accused of a “divide and rule” policy aimed at playing community groups against one another. In some cases, attempts were made to manipulate the selection of contractors as preferred candidates [5] . Another contractor with Shell stated during the interview that:

“For you to be assured of a contract renewal, you must play by the rules and satisfy the third parties (the MNCs), as they are under incessant pressure from the community leaders who believe it is their birth right to be a contractor with the companies, and plant their natives in the organisations, irrespective of competence. This leaves the third parties nowhere as they rely more on the community leaders in solving their problems during crises/hostilities from the locals of the community. In fact, you will be surprised that some of the MNCs have more than 500 contractors with some contractors supplying only two staff”.

This study revealed that there are three ways through which contract employees gain entrance into the firms―these include: a) direct recruitment, b) a labour contractor who has a contract to bring in employees and, c) those that join on a contract for service basis. The last two categories are more relevant to this research.

Workers who occupy the valued core spots of Shell, Mobil and Chevron and are normally called “tenured staff”, are employed on a full-time/permanent basis, and as such, are usually in through the direct recruitment means. Remuneration for this category of workers includes a basic salary, standard allowances and other enviable welfare packages [40] . Candidates applying for tenured employment are made to enter into a contract for service with Shell, Mobil and Chevron Nigeria, specifying the terms and conditions of service and the effective date on which the company has engaged the worker. Bamber [13] notes that organisations use different approaches in different countries in which they invest, which largely depends on the company’s extent of global integration against local/national embeddedness.

The Nigerian oil workers have many ways of describing the contract labour system, as mentioned in the previous section. The two unions―the Petroleum and Natural Gas Senior Staff Association of Nigeria (PENGASSAN) and the National Union of Petroleum and Natural Gas Workers (NUPENG), they are campaigning all-out against what they see as exploitation. When oil and gas production began in Nigeria, “the companies were integrated in terms of structure, staffing and operations”, recalls NUPENG General Secretary. Unfortunately, “over the last twenty-five years, an ugly situation started emerging with the contracting out of certain jobs, perceived by these companies not to be directly linked with the core production line”. This “cankerworm” has, he says, “eaten deeply into the industrial relations practice in the oil and gas industry.” A contract staff with Shell Information Technology department informed that:

“The oil companies are making so much money from Nigeria and only embark on capital flight, rather than use part of the money in creating sustainable employment opportunities in this country. Some of the practices you find with the companies will not happen in any other part of the world but they (the MNCs) are capitalising on the comatose nature of the Nigerian economy. But for the alarming unemployment rate plus a very weak legal structure, the situation could have been different I suppose”.

This argument was debunked by most of the contractors who see no need to hire employees on a permanent basis when his/her services would be short-lived. A contractor with Mobil summarised the views of other contractors as follows:

“I think labour contracting has come to stay and it is not peculiar to Nigeria or the oil sector. Please, tell me why a company should hire someone on full time/permanent basis when they already know the end date of the project at hand. After the completion of the project, what should the person be doing? People must realise that an employee is hired, irrespective of the nature of contract, for what he can do and to serve the need of an organisation. All of these arguments from the contract staff or their unions are nonsense; after all, they are lucky, as millions of others are roaming the streets in search of a job”.

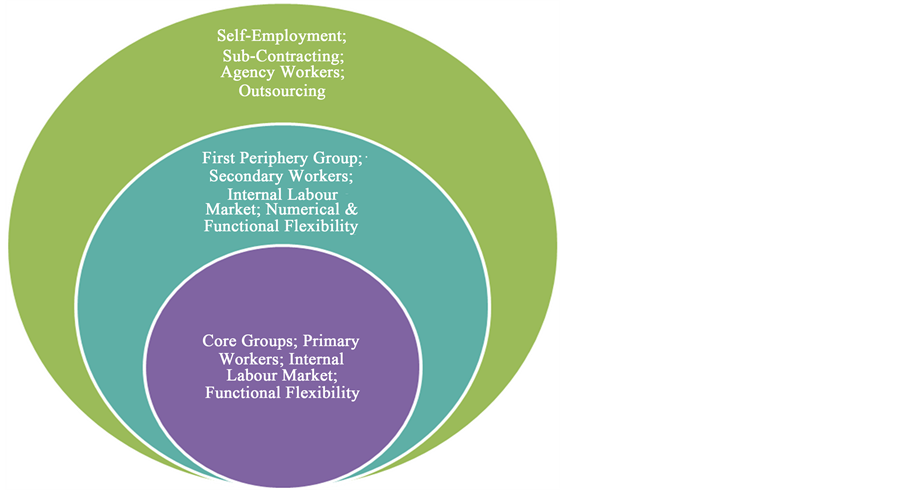

The internal labour market in Shell, Mobil and the Chevron Nigerian subsidiary can be divided into the core and periphery (servicing sector) segments. The core segment is similar to the character of Atkinson’s flexible firm model as depicted in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. The Atkinson’s model. Source: Atkinson, 1984.

This is made up of workers with relatively stable employment, who are usually well remunerated with “mouth-watering” benefits that keep them secured against the highly-fluctuating economic conditions in the country. Such contracts also provide enormous opportunities for career progression within the various departments of the organisations. Those in the core are often recruited through formal firm-specific recruitment procedures. At present, Shell, Mobil and Chevron have policies of directly employing a limited number of graduates and experienced professionals on permanent basis. The scale and dimension with which the companies’ management have engaged the use of contract workers have made the core of Shell, Mobil and Chevron Nigeria’s internal labour market a highly valued spot for Nigerian graduates and professionals to occupy [25] .

As stated by one of the employees of Mobil in the security unit:

“I am a university graduate with second class upper division in Engineering but here I am as a security man in Mobil. What choice have I, having searched for job in my field without luck? So, when this came my way, even though it is a contract job, I quickly grabbed it. More so, the pay is relatively better than what my colleagues in the public sector are paid”.

As the shift towards a two-tier workforce becomes more entrenched with pronounced job insecurity, the MNCs have inadvertently increased resentment among individuals and surrounding communities. This purposive employer segmentation or flexible strategy incentivised by economic motives provides a scope for internal work conflicts, which often spill over to the surrounding communities [41] . The dissatisfaction of contract workers with the new forms of work organisation has led to increased community tension [27] .

The work environment in traditional Nigerian communities was characterised by security of employment, devoid of the fear of redundancy, dismissal or early retirement [2] [42] . This practice was prevalent in civil service jobs, where employment contracts are often on a permanent basis. In urban and rural Nigeria, the preference of work-for-life is obvious, as social security is a virtually non-existent resource. For many in Nigeria, getting a “permanent job” is the only way they can augment the poor allocation or distribution of social amenities.

2.4.2. Remuneration of Contract Staff

Compensation, reward, remuneration and payment are the four most commonly used terminologies when describing what an employee deserves after his/her services to an organisation. All of these can include monetary or non-monetary value. Wages and salaries are decreasing as many organisations move towards the harmonisation of terms and conditions for different groups of workers [43] . Contemporary pay systems (outside the entertainment and professional sports fields) are characterised with cost containment, pay, and benefit levels commensurate with what a company can afford, and by programmes that encourage and reward performance [44] .

A number of authors, including Gomez-Mejia et al. [36] , Mullins [45] , and Eyupoglu and Saner [46] have drawn a link between remuneration and job satisfaction. In Nigeria, there is a minimum wage for public sector workers, which is not enforced by employers in the private sector [41] . As a result, wages and benefits in the oil and gas sector are determined by the management of the organisation and this differs significantly between the “tenured staff” and the “contract staff”. On the question of remuneration, employees were asked to give an idea of the disparity (if any) in their (contract workers) salary and that of the permanent workers.

The range of responses showed that 80% of respondents believed that they were paid significantly less than their colleagues depending on the type of contract; 18% were in agreement of pay satisfaction; and 2% claimed to be indifferent. A contract staff with Chevron in the Engineering department said that:

“There is no equity in the reward system here. At least, you will expect that internal equity will ensure that more demanding positions or better qualified people within the organisation are paid more, but that is not the case. Rather, if you are a contract staff, you get less, even when you are better qualified”.

From the semi-structured interview with some of the contractors, it was revealed that the organisations operate a system of salary secrecy in which employees are kept in the dark regarding the wages of colleagues. However, this information is passed around during informal discussions among employees. One of the contractors with Shell was confronted with the question of the disparity in salaries of permanent and contract staff, and she said:

“This is something beyond my purview as the third party often dictates what should be paid and only give us (contractors) a fee for the services provided―supply of labour. I agree that actual wage levels should depend on labour market conditions, legislation, collective bargaining, management attitudes, and the organisation’s ability to pay; but that is not the case in Nigeria, as all of these factors come with challenges”.

The interview revealed that the majority of those who consider their pay to be good do so according to relative terms with that which is prevalent in other industries within the economy. In contrast, those who disagree with the pay package are comparing their output with that of the permanent staff who earns more money, as claimed. One employee in the Finance department of Mobil resorted to saying that:

“How can I be satisfied with my pay when I know that there are people in this organisation who do not have my qualifications, yet earn a lot more than me? Of course, I agree that when you compare what I earn as a contract staff in an oil company with what is paid in other sectors in Nigeria, I should be happy; but you know how painful it is when you know your worth”.

Another staff of Chevron in Operations department claimed that:

“I am upset when I look at my salary and that of my colleagues who are on permanent employment. While we are in the same office, carry out the same routine, we end up going home with different pay; and I am talking of a wide margin. What can be more annoying and depressing”?

It appears that the option that is chosen in the Nigerian oil and gas sector is the use of contract labour to be dominant in order to cut costs, at the expense of other viable options. One of the contract staff from the “Meet and Greet” unit of Chevron in Lagos said that:

“The MNCs cannot claim any inability to pay us contract staff what they pay permanent staff or even hire us on a permanent basis. After all, we know how much money they are making, and we see how the expatriates and executives among the indigenous ones live large and travel frequently with their family. They are capitalising on the fact that we are voiceless and the employment law here is weak”.

On the issue of being voiceless, this study probed into the role of the trade union in wage determination. In recent years, with a framework of legislation that has sought to curb the power of the unions against a background of high unemployment, trade unions have not particularly been powerful forces in bargaining on wages and salaries, especially for the casualised workers [2] [3] . The Operations Director of NUPENG mentioned that:

“Nigerian employment law does not make provision for the union to be part of the negotiation for employees pay, except for those in the public service that have the support of the NLC. The situation is more challenging in the private sector”.

Equity theory suggests that social comparisons are an important influence on how employees evaluate their pay. Employees make external comparisons between their pay and the pay they believe is received by employees in other organisations. Such comparisons may have consequences for employee attitudes and retention [13] . Employees also make internal comparisons between what they receive and what they think others within the organisations are paid. These types of comparisons may have consequences for internal movement and may raise the question of equity. This often plays an important role in the controversy over executive pay.

2.4.3. Condition of Work (Benefits and Services)

Respondents for this research were asked about the incentives and fringe benefits they received. Fringe benefits include: medical treatment, pension schemes, sick allowances, and house and car allowances.

Following the findings from the interview, 100% of the interviewees confirmed that contracted employees do not get fringe benefits like the permanent staff, especially the pension scheme and medical treatment. The permanent employees of the case study organisations are entitled to the mentioned benefits. The pension scheme operated is a contributory one, with the employer matching the contributions of the employees. All permanent/core staff and four of their dependants have access to free medical treatment. These categories of workers also get house and car allowances, which are usually given to them once a year. Other perks given to core staff include maternity pay, Christmas bonus, leave allowance, profit sharing, a performance bonus and rent allowance. A contract staff member with Mobil in the transport section suggested that at the end of their contracts:

“We are paid off without any pension allowance, without any access to free medical facilities nor are we given car or house allowances every year like the permanent staff”.

A number of lobbying initiatives and industrial actions have been staged by the unions over the issue of inequity of remuneration and benefits in the industry [47] . It must be mentioned that the contractors interviewed disputed the claim by the contract staff that they have no pension or medical facilities access. The quote below typified the views of most of the contractors but was succinctly placed by one with Shell and Mobil:

“Whoever says contract staff don’t have access to medical facilities at all will be lying, ditto for the payment of pension. The two multinationals that I have contracts with, Shell and Mobil, make it mandatory for us to give medical facilities and ensure provision for pension for contract staff. To do otherwise is to risk losing your contract, because the staff talk, and also they are the ones that work directly with the third party―MNCs. Of course, the amount of benefit is incomparable with the employees with the same organisation but on permanent employment; and I guess that is understandable”.

Employees were asked who they discuss work problems with as part of existing conditions at work.

77% said they were comfortable discussing their problems with fellow colleagues on contract like them. Another 13% claimed that they discuss with their line manager at the contracting firm. 8% discuss with their line manager in the user firms; while 1% each discuss with the union and employees on permanent employment.

With the above statement in view, contract staff were confronted with the question again on whether or not they get any of these benefits, and one of the Shell employees in the “Meet and Greet” unit said:

“It is true that we are told we have medical facilities but I think it just another avenue to reduce my take-home. For instance, every month N15000 is deducted from my salary for medical and neither myself nor any family member have been sick. In fact, a few colleagues on contract employment like me who were in the Medical Centre during sickness reported poor services as they were given paracetamol which could be bought for a lesser amount. I would rather have my money and take care of myself when I am sick”.

The responses of employees when asked how long they have been working as contract staff, vis-à-vis the number of times their contracts have been renewed on a yearly basis were posed:

49% of those interviewed claimed to have been on contract for over six years, 33% claimed to have been in employment as contract staff for between four and five years; with 16% having been employed for over two to four years and only 2% are less than a year in employment. However, it is important to mention that some have only received one contract, which was signed at the beginning without ever having to sign any other.

A Mobil contract staff member from the Finance department in the Lagos office said during the interview:

“The level of discrimination here in Mobil is worse than you will get in some of the oil companies. Here, you will not believe that there are different entrances for permanent workers and those of us on contract. As if that is not enough, we don’t use the same canteen as we are seen as second class staff. The discrimination is carried further to the staff bus. As contract staff, we have no right to use the staff bus but could be given the privilege if there are spaces with no permanent staff waiting; yet we are working for the same organization”.

However, when contract staff members with Chevron in Escravos were asked the same question, their responses were more generous, as represented by the quote below:

“I will say the situation here in Chevron is such that we have the same canteen with the permanent staff, use the same staff bus, though, with priority for the permanent staff and our medical facilities are good too. This is not to say that there are no inherent hostilities between us as the permanent staff allows their ‘status’ to go to their heads”.

Temporary workers and union officials have consistently claimed that Shell, Mobil and Chevron managers have deliberately kept a very small permanent workforce in Nigeria and continuously enlarged the number of contract staff. For instance, the PENGASSAN Oil Union Assistant Secretary General pointed out that:

“The sort of complaint we get from our members and those who want to be our members is disturbing. I even believe the MNCs are short-changing themselves, because how do you create such a divide within the rank and file of your staff and expect productivity to be optimal? I can’t get it”.

Again, it was pointed out that Shell, Mobil and Chevron management have adopted a strategy of keeping a small core workforce, by redeploying expatriates from various countries to Nigeria to attain their aim of bringing in people just-in-time to take on new tasks [4] . This is in agreement, in a sense, with Atkinson’s view as he argues that the new structure emerging among MNCs is that managers are tending towards breaking up the workforce into peripheral or numerical flexible groups of workers clustered around a stable core group that would conduct the organisation’s specific activities. Workers at the core are those who win their employment security at the cost of accepting functional flexibility both in the short term (involving cross-trade working, reducing demarcation, and multi-discipline project teams) as well as in the longer term (changing career and retraining) [48] .

2.4.4. Job Security

Job security is arguably the most important factor among employees on contract with the organisations studied in this research. Employment insecurity refers to that subjective awareness that workers have about the threat of losing their jobs [12] . A high level of job insecurity is seen as the hallmark and characteristic of contract staff. This set of individuals worry about the future of their jobs; it is uncertain whether they will retain their jobs or not, which makes it impossible for them to adequately prepare for the future. As contract staff, they already know the end at the beginning. The contract can be ended at any time, which leads to anxiety (hoping that the contract will be renewed). A contract staff with the Chevron “Meet and Greet” unit said during the interview:

“The absence of job security in my employment contract is a cause for perpetual anxiety as the future is ever bleak and uncertain. I must say that if it is a deliberate design to keep us contract staff on our toes, then it’s working because we always attempt to impress everyone so as to keep the job”.

Below is the response of employees when asked about job security:

From the survey carried out on job security, 80% of the respondents agree that there is no job security for them. Another 18% felt the job is relatively secured. It is important to mention that those in this category (18%) have been in the job for over six years and assumed automatic contract renewal since this has been the case over the years. Only 2% felt indifferent.

Another participant from the Mobil Medical Unit pointed out that:

“We are frequently sacked; sometimes workers are sacked and reappointed a few months later through the agency of another contractor. There are some workers who are fortunate that they work under different contracts that get renewed every year. Many are less fortunate”.

For Budd Spencer [38] , “Job insecurity or scarcity creates motivation among workers to exert more effort on their work”. It is debatable as to what extent contract workers will be encouraged in the operations of the MNCs in the Nigerian oil sector when they feel consistently barred or deliberately retarded from promotion or career progression by the organisations being studied. It can be argued that when workers feel wholly excluded from employment, some workers will feel disintegrated and alienated from the firm. The “hidden costs” of employing a large secondary workforce are often difficult to measure [41] . For instance, in Shell Nigeria, contract workers in both the core and the secondary sectors are setting up personal, private businesses, in order to survive the termination of their employment. One participant in the transport unit of Shell informed that:

“When you are a contract staff, you are operating with mixed feelings. One, you want to work your heart out to impress the third party so that you can be recommended for contract renewal and you might be lucky to get converted into permanent employment. But the other natural feeling is the question of why should I over-work myself when I know the end from the beginning. This is because there are people who have been working as contract staff for more than twelve or even fifteen years, yet they never get converted. So, what I have resorted to is to have a small business in case I never get called back”.

On the issue of the number of times a contract may be renewed, some of the contract staff revealed:

“You can get your contract renewed many times year-in, year-out, without signing any paper. The last thing you want to ask is the contract paper, as you will thank your God that you still have the job. Most of us have been on contract for over seven to ten years, yet, we have only signed once for a year at the beginning. All these don’t give you assurance you have a job the next month. It is more of an instrument to deal with our psyche and what choice do we have?”

Survey was carried out on the number of times contracts were renewed for a contract staff. 37% claimed they only signed one contract at the beginning and have been on the job for over seven years; 22% claimed their contracts have been renewed about five to six times; 14% claimed four to five times; while 11% claimed three to four times. Only 16% claimed they have only renewed once or twice.

The subject of job security was echoed in the work of Saloniemi and Zeytinoglu [49] while examining the complex nature of flexible working arrangement in the Finland and Canadian labour market. They asked respondents to assess their job security, and it was revealed that the categories of workers who regarded themselves as having low levels of job security were the secondary work groups. They suggested that employers were achieving flexibility through job insecurity.

2.4.5. Employment Relations between Contract Workers, Management and Oil Unions

In Nigeria, from a legal perspective, a trade union can be defined as “any combination of workers or employers, whether temporary or permanent, the purpose of which is to regulate the terms and conditions of employment of workers” [50] . Nwoko [51] points out that trade unions are organisations that have the capacity to, and do, facilitate, “the creation and mobilisation of workers” collective powers. This “collective powers” primarily allow workers “to exert, collectively, the control over their conditions of employment, which they cannot hope to possess as individuals” [52] . Workers generally join the trade unions for the benefits that may accrue to them; these benefits include economic, social, educational and political benefits. However, in Mobil, Chevron and Shell Nigeria’s internal labour market, contracted workers find it difficult to be members of the companies trade unions as some of the contractors made this known from the beginning, or where their contract covertly suggests so― “yellow dogs”. For example, the Operations Director of Petroleum and Natural Gas Senior Staff Association of Nigeria (PENGASSAN) pointed out:

“It has always been a battle to unionise the contract workers. This has continued to weaken us and many attempts have been made to get the management of these organisations on our side. The fact that they (the user firms) threaten the contractors and by extension, the contracted workers do not help matter at all”.

The survey shows that 84% of respondents were not members of a union, while 16% were members. All union officers interviewed for this study viewed the increasing use of the precarious employment contracts as an adverse or negative managerial policy, which has led to a weakening of the union. For instance, the PENGASSAN president argued that the increasing use of secondary workers in the oil and gas sector in Nigeria is the employers’ strongest weapon in vitiating the viability of the union. To this end, the contract staff also often queries the need to join a union, as a number of them believe this will threaten their jobs. One staff member in the Human Resource department of Mobil asserted that:

“Why should I join the union and open myself to cheap attack by management. My contract is only for a year, and nothing guarantees that the union can ensure its renewal; rather my activities or affiliation with the union can only put me in the trouble spotlight”.

Another staff member of Chevron in the transport unit viewed it purely from financial angle, when he said:

“There is no point in joining the union when you are a contract staff. As a union member, I will be required to make a financial contribution every month, and my contract is only for a year without any assurance of renewal. Even when my contract is renewed, it is as good as I am starting afresh and all that had been contributed in the previous year would be gone. Please, tell me, where is my gain? Yet, management frown at union members and their activities; so, why should I subject myself to cheap attack when I can avoid it”.

Respondents were asked whether or not they were aware of the activities and impact of the trade unions. An overwhelming majority of about 84% claimed to be aware but lamented the challenges that come with discharging such responsibilities by the unions. About 8% claimed a lack of awareness of union activities as it relates to the concerns of contract staff, and 8% suggested that they were indifferent. As pointed out by many of the leaders, the fact that there are no clear laws that overtly support the unionisation of contract staffs is challenging, albeit there are policy statements to this effect which are often manipulated. The Assistant General Secretary of NUPENG in Lagos said that:

“All we can do is to pick our battles wisely. The odds are many and difficult to combat as there are no definite laws supporting these (contract) workers. As I speak with you, we will be in court next week over some of the employees of MRS Company that were recently sacked. Some of them have been working with the organisation for over seven years, yet have only one contract which was given to them at the beginning stating that the contract is only for a year. We have had to go through unconventional means to get the staff on board as members, and now, we have to fight for them”.

The fact that contracted employees do not get immediate dividends for being union members is another concern for many, and this has made a number of them lose faith in the capability of the union. One of the contract staff of Mobil, from the Engineering department, said that:

“I am not keen to join the union as I do not see what they can do for me. Some of my colleagues do not get a renewal at the end of their last contract and they are union members. The union couldn’t do anything because the contract terms are clear. So, the fact that I am lucky to get mine renewed is not to the glory of the union but God”.

Ideally, the union influence can affect motivation through the determination of wage rates, seniority rules, layoff procedures, promotion criteria, and security provisions [44] . Unions can influence the competence with which employees perform their jobs by offering special training programmes to their members, requiring apprenticeships, and allowing members to gain leadership experiences through union organised activities [53] . The actual level of employee performance will be further influenced by collective bargaining restrictions placed on the amount of work produced, the speed with which work can be done, overtime allowances per worker, and the kind of tasks that any given employee is allowed to perform [54] .

When I confronted the contractors with the question of why they threaten the contract staff with dismissal should they join the union, a contractor with Chevron said that:

“It is untrue to say that we threaten any of the contract staff with dismissal if they join the union. Every employment, irrespective of its nature, be it tenured or fixed-term, have employment contract terms detailing expectations, and so it is, with the contract employment. But candidly speaking, why should an employee of a fixed-term contract, like those we manage, be part of a union? His employment is for a short term and the union will only collect his money for that period without giving him/her anything in return. Don’t forget that the union is not a cooperative society where you can get your money at the end of the day”.

Clearly, from the foregoing, the discriminatory segmentation of the oil MNC in the Nigerian labour market has had key negative knock-on effects on the influence of the oil and gas unions.

3. Conclusion

Whereas downsizing has been a popular method for reducing a labour surplus, hiring temporary workers and labour contracting has been the most widespread means of eliminating labour shortage. Contract employment may afford firms the flexibility needed to operate efficiently in the face of swings in the demand for goods and services. Again, the use of contract workers frees the firm from many administrative tasks and financial burdens associated with being “employer of record” [55] . It is equally hoped that contract workers with little experience of the host firm will bring an objective perspective to the organisation’s problems and procedures that is sometimes valuable. This is in addition to the fact that a contract worker may have a great deal of experience in other firms, which can sometimes be used to identify solutions to the user firm’s problems that are confronted in a different firm.

Cite this paper

Hakeem Adeniyi Ajonbadi, (2015) The Dynamics of Policies and Practices of Labour Contracting in the Nigerian Oil and Gas Sector. Open Access Library Journal,02,1-15. doi: 10.4236/oalib.1101756

References

- 1. National Bureau of Statistics (2015) Social Statistics of Nigeria.

http://www.nigerianstat.gov.ng/nbsapps/social_statistics/SSD%20final.pdf - 2. Fajana, S. (2011) Industrial Relations and Collective Bargaining in Nigeria. 6th African Regional Congress of the International Labour and Employment Relations Association, University of Lagos, 24-28 January.

- 3. Okougbo, E. (2010) The Menace of Contract Staffing/Casualisation in the Oil and Gas Industry Capable of Creating Industrial Unrest. Energy News International Journal.

- 4. Ajayi, F. (2011) Challenges before the Labour Movement in Nigeria. Energy News International, 8.

- 5. Momoh, A. (2010) Casualisation/Contract Staffing in Oil and Gas Industry: Giving It a New Status. Energy News International Journal.

- 6. Barrientos, S. (2011) “Labour Chains”: Analysing the Role of Labour Contractors in Global Production Networks. Brooks World Poverty Institute Working, Paper 153, Manchester.

- 7. Mohammed, Z. (2010) The Agony of Casual Labour. http//www.theexpress.com/express20418/features/features2.htm

- 8. Hatton, E. (2014) Temporaty Weapons: Employers’ Use of Temps against Organized Labour. ILR Review, 67, 86-110.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/001979391406700104 - 9. Hveem, J. (2013) Are Temporary Work Agencies Stepping Stones into Regular emPloyment? IZA Journal of Migration, 2, 1-27.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/2193-9039-2-21 - 10. ILO (2015) Non-Standard Firm of Employment, Report for Discussion at the Meeting of Expert on Non-Standard Form of Employment, Conditions of Work and Equality Department, Geneva.

- 11. Lee, J.W. (2014) Labour Contracting and Changing Employment Relationships in South Korea. Development Policy Review, 32, 449-473.

- 12. Serrano, M.R. (2014) Between Flexibility and Security: The Rise of Non-Standard Employment in Selected ASEAN Countries. ASEAN Services Employees Trade Unions Council (ASEANTVC), Jakarta.

- 13. Bamber, G.J., Lansbury, R.D. and Wailes, N. (2011) International and Comparative Employment Relationships. 5th Editions, Sage Publications Ltd., London.

- 14. Atkinson, J. (1984) Manpower Strategies for Flexible Organisations. Personnel Management, 16, 28-31.

- 15. Atkinson, J. (1996) Temporary Work and the Labour Market. IES, London.

- 16. Carpenter, M. (2009) Managing Effectively through Tough Times.

- 17. Burgess, J. and Connell, J. (2004) International Perspectives on Temporary Work. Routledge, London.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780203579084 - 18. Burgess, J. and Connell, J. (2005) Temporary Agency Work: Conceptual, Measurement and Regulatory Issues. International Journal of Employment Studies, 13, 19-30.

- 19. Burgess, J. and Connell, J. (2006) The Influence of Precarious Employment on Career Development: The Current Situation in Australia. Education + Training, 48, 493-507.

- 20. Papola, T.S. (2013) Role of Labour Regulation & Reforms in India; Country Case Study on Labour Market Segmentation, Employment Working Paper No. 149. ILO, Geneva.

- 21. Pollert, A. (1987) The Flexible Firm: A Model in Search of Reality (or a Policy in Search of a Practice?). Warwick Papers in Industrial Relations, No. 19.

- 22. Battisti, M. and Vallanto, G. (2013) Flexible Wage Contracts, Temporary Jobs and Firm Performance: Evidence from Italian Firms. Journal of Industrial Relations, 52, 737-764.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/irel.12031 - 23. Claydon, T. (2001) Human Resource Management and the Labour Market.

- 24. Jahn, E.J. and Rosholm, M. (2014) Looking beyond the Bridge: The Effect of Temporary Agency Employment on Labour Market Outcomes. European Economics Review, 65, 108-125.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2013.11.001 - 25. Mordi, C. (2008) Segmented Work and Ethnic Divided Workers in the Nigerian Oil Sector. International Africa Academy of Business and Development Journal, 9, 533-537.

- 26. Eppeh, L. (2001) Stop Slave Labour. Energy News International, 1, 12-16.

- 27. Okafor, E.E. (2007) Globalisation, Casualisation and Capitalist Business Ethics: A Critical Overview of Situation in the Oil and Gas Sector in Nigeria. Journal of Social Science, 15, 169-179.

- 28. Redman, T. and Wilkihson, A. (2008) Contemporary Human Resources Management: Text and Cases. 3rd Edition, FT/Prentice Hall, Harlow.

- 29. Pena, X. (2013) The Formal Informal Sectors in Colombia: Country Case Study on Labour Market Segmentation, Employment Working Paper No. 146. ILO, Geneva.

- 30. Neuman, S. (2014) Job Quality in Segmented Labour Markets: The Israeli Case Conditions of Work and Employment Series. ILO, Geneva.

- 31. Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) (2015) Economic Report for the First Quarter of 2015.

http://www.cenbank.org/OVT/2015.publicoluns/reports/RSR/2015 - 32. Uwaifo, O.R. (2008) Disparities in Labour Market Outcomes across Geopolitical Regions in Nigeria Fact or Fantasy? Journal of African Development, 10, 16-31.

- 33. Coe, N. and Jordhus-Lier, D. (2010) Constrained Agency? Re-Evaluating the Geographies of Labour. Progress in Human Geography Journal, 23 April 2010.

- 34. Weil, D. (2014) The Fissured Workplace: Why Work Balance So Bad for So Many and What Can Be Done to Improve It. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4159/9780674726123 - 35. Bell, E. (2011) Managerialism and Management Research: Would Melville Dalton Get a Job Today? In: Cassell, C. and Lee, B., Eds., Challenges and Controversies in Management Research, Routledge, London, 122-137.

- 36. Gomez-Mejia, L., Balkin, D. and Cardy, R. (2012) Managing Human Resource. 5th Edition, Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River.

- 37. Harzing, A.W.K. and Pinnington, A. (2011) International Human Resources Management. 3rd Edition, Sage Publication Ltd., London.

- 38. Budd, J.W. and Spencer, D.A. (2014) Worker Well-Being of Work; Bridging the Gap. European Journal of Industrial Relations, 21, 181-196.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0959680114535312 - 39. Mordi, C. and Mmieh, F. (2009) Divided Labour and Divided In-Firm Markets in the Nigeria Petroleum Sector. Proceedings of the 10th International Academy of African Business and Development Conference, Kampala, 19-23 May 2009, 439-446.

- 40. Oke, A. and Idiagbon-Oke, M. (2007) Implementing Flexible Labour Strategies: Challenges and Key Success Factors. Journal of Change Management, 7, 69-87.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14697010701254912 - 41. Kupolokun, F. (2007) The Nigerian Oil and Gas Industry: Consolidating the Gains. A Paper Presented at the Nigerian Oil and Gas Conference, Abuja.

- 42. Otite, O. (2001) Sociological Dimensions of Researching Ethnicity and Ethnic Conflicts in Nigeria. Paper Presented at the Methodology Workshop, Ethnic Mapping Project Programme on Ethnic and Federal Studies, University of Ibadan, Ibadan.

- 43. Kew, J. and Stredwick, J. (2010) Human Resources Management in Context. 3rd Revised Edition, CIPD, London.

- 44. Gamero, A., Kampelmann, S. and Rycx, F. (2014) Minimum Wage Systems & Earnings Inequalities; Does Institutional Diversity Matter. European Journal of Industrial Relations, 21, 115-130.

- 45. Mullins, L. (2007) Organisational Behaviour. 4th Edition, Pearson Education, New York.

- 46. Eyupoglu, S.Z. and Saner, T. (2009) The Relationship between Job Satisfaction and Academic Rank: A Study of Academicians in Northern Cyprus. Paper Presented at the World Conference on Educational Science, North Cyprus, 4-7 February 2009, 686-691.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2009.01.120 - 47. Natural Union of Petroleum and Natural Gas Workers (NUPENG) (2014)

- 48. Nielen, S. and Schiersch, A. (2014) Temporary Agency Work and Firm Competitiveness: Evidence from German Manufacturing Firms. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 53, 365-393

- 49. Saloniemi, A. and Zeytinoglu, I.U. (2005) Achieving Flexibility through Insecurity: A Comparison of Work Environments in Fixed-Term and Permanent Jobs in Finland and Canada. European Journal of Industrial Relations, 13, 109-128.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0959680107073971 - 50. Aturu, B. (2005) Nigeria Labour laws: Principles, Cases, Commentaries and Materials. Frankad Publishers, Lagos.

- 51. Nwoko, K.C. (2009) Trade Unionism and Governance in Nigeria: A Paradigm Shift from Labour Activism to Political Opposition. Journal of Information, Society and Justice, 2, 139-152.

- 52. Archibald, W.P. (2009) Marx, Globalisation and Alienation: Received and Underappreciated Wisdoms. Critical Sociology, 35, 151-174.

- 53. Marginson, P. (2015) Coordinated Bargaining in Europe: From Incremental Corrosion to Frontal Assault. European Journal of Industrial Relation, 21, 97-114.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0959680114530241 - 54. Garcia-Serrano, C. and Malo, M.A. (2013) Beyond the Contact Type Segmentation in Spain. Country Case Study on Labour Market Segmentation, Employment Working Paper, No. 143, ILO, Geneva.

- 55. Belous, R.S. (1990) Flexible Employment: The Employers’ Point of View. In: Doeringer, P.B., Ed., Bridges to Retirement, Cornell University, ILR Press, Itchca, 111-129.