Open Access Library Journal

Vol.02 No.08(2015), Article ID:68571,9 pages

10.4236/oalib.1101800

Food Insecurity: Prevalence and Associated Factors among Adult Individuals Receiving Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) in ART Clinics of Hosanna Town, Hadiya Zone, Southern Ethiopia

Mekuria Asnakew

Department of Epidemiology, College of Public Health and Medical Sciences, Jimma University, Jimma, Ethiopia

Email: mekas63@yahoo.com

Copyright © 2015 by author and OALib.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 30 July 2015; accepted 18 August 2015; published 21 August 2015

ABSTRACT

Background: Food insecurity and poor nutritional status may hasten progression to Acquired Immuno Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS)-related illnesses, undermine adherence and response to antiretroviral therapy, and exacerbate socioeconomic impacts of the virus. There is a risk that declining food security will lead some people to discontinue treatment, due to a lack of adequate food. Little is known about prevalence and predictors of food insecurity among adults people on antiretroviral therapy (ART) in the Ethiopia context, particularly at the study area. Objective: To determine prevalence of food insecurity and identify its predictors among adult individuals receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in ART clinics of Hosanna Town. Methods: A cross sectional study was carried out from January 1, 2015 to February 30, 2015 in health facilities of hosanna town. Data were collected by face-to-face interview using structured pretested questionnaires and record review. I used multivariable logistic regression model to identify predictors of food insecurity among 385 adult people (≥18 years) attending ART Clinics of Hosanna town. Results: Overall, the prevalence of food insecurity was (67.5%) among people on HAART at the study area. Poor economic status [OR = 4.34 (95% CI; (2.53 - 7.45))], middle economic status [OR = 4.1(95%CI; (2.17 - 7.57))], educational status of secondary or lower [OR = 1.7 (95%CI; (1.06 - 2.72))], absence of food support [OR = 2.35 (95%CI; (1.02 - 5.39))], and unemployment [OR = (95%CI; 1.71 (1.06 - 2.74))] were significant and independent predictors of food insecurity. Conclusions: People on HAART suffer from a significant amount of Food insecurity at the study area. Absence of food support, lower educational status, unemployment, poor and middle economic status were independent predictors of food insecurity. Food insecurity interventions should be an integral component of ART programs. Intervention initiatives should address patients with lower educational status and unemployed; and also should focus in improving socio-economic status and involving people on ART in income generating g activities.

Keywords:

Anti-Retroviral Therapy, Food Insecurity, Human Immune Deficiency Virus, Hosanna

Subject Areas: Nutrition

1. Introduction

According to World Bank, food security is defined as “access by all people at all times to enough food for an active, healthy life” [1] . The concept of food insecurity includes problems with the quantity and quality of the food available, uncertainty about the supply of food, and experiences of going hungry [2] . The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic remains one of the main public health challenges especially in low and middle income countries. At the end of 2010, globally an estimated 34 million people were living with HIV/AIDS with 2.7 million new HIV infections and the annual number of people dying from AIDS related causes was 1.8 million. The majority of adults newly infected with HIV are in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). In SSA, an estimated 1.9 million people become infected with HIV in 2011. Ethiopia is one of the seriously affected countries in SSA with a large number of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA), approximately 800,000 and 44,751 AIDS-re- lated deaths [3] . According to the 2011 Ethiopian demographic and health survey (EDHS), HIV prevalence in Ethiopia is 1.9% for women and 1.0% for men with an overall prevalence of 1.5%. This is essentially unchanged from the HIV Prevalence reported in 2005 (1.4%) [4] . Food insecurity and poor nutritional status may hasten progression to Acquired Immuno Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS)-related illnesses, undermine adherence and response to antiretroviral therapy, and exacerbate socioeconomic impacts of the virus. Research shows that, within households affected by HIV, there is an increased risk of food insecurity as sick members are unable to work, income declines, expenditure on health care increases and care-giving burdens increase [5] . HIV infection itself weakens food security and compromises nutritional status by reducing work capacity and productivity, and jeopardizing household livelihoods [6] . In resource limited settings, many people infected with HIV lack access to sufficient quantities of nutritious foods, which poses additional challenges to the success of Anti Retroviral Therapy (ART) [2] [7] . There is a risk that declining food security will lead some people to discontinue treatment, due to a lack of adequate food (which is necessary for taking antiretroviral drugs) [7] . The combined impacts of food insecurity and HIV/AIDS place further strain already limited household resources as affected family members struggle to meet household food needs [8] . However; little is known regarding to prevalence of food insecurity and associated factors among adult individuals on ART in the Ethiopia context, particularly at the study area. In addition, previous study was not well addressed factors affecting food insecurity. Thus, the objective of this study was to determine prevalence of food insecurity and identify its predictors among adult individuals receiving highly active antiretroviral in ART clinics of Hosanna Town. The results of this study will help health authorities and other concerned bodies to design food insecurity interventions to improve the health status of people infected with HIV on ART. Further, the study can provide base line information for other studies and the information obtained can strengthen HIV/AIDS continuum of care.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Study Design, Area and Study Population

Facility based cross-sectional study was conducted among adult people on HAART at health facilities of Hosanna town. The study was conducted from January 1, 2015 to February 30, 2015 in Hosanna town, which is 230 km far from Addis Ababa in the south west direction. There are only two ART care units in the town at Nigist Elenie memorial Hospital and Hosanna health centre. A total of 3780 clients were present on pre ART and ART care units at the two ART care units. The source population was all adult people who are enrolled in highly active anti-retro viral therapy at ART clinics of Hosanna town and the study population was selected adult people on antiretroviral therapy at ART clinics of Hosanna town during the study period that fulfils the inclusion criteria. The study include all adult people on antiretroviral therapy willing to participate and age of 18 years and more and exclude individuals who were seriously ill and un-able to get through the interview.

2.2. Sample Size Determination and Sampling Procedure

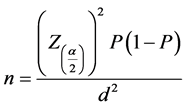

The required sample size was determined using single population proportion formula,

considering the following assumptions: P = 63% (proportion of people on ART considered as food insecure) [9] , Zα/2 is the value of the standard normal distribution corresponding to a significant level of alpha (α) of 0.05, which is 1.96 and desired degree of precision (d) of 5%, the computed sample size was 309 and by adding 10% non response rate, the total sample size computed was 394. Before data collection a list of eligible ART clients were identified from ART data base. According to the total number of ART clients in each clinic, proportionate umber of sample clients were assigned for each ART clinics. Study participants were selected by simple random sampling technique using random number computer generation method.

2.3. Data Collection Procedures

Data were collected by face-to-face interview using pre tested structured questionnaires and record review. Three ART adherence counselors as data collectors and one health officer as supervisor were recruited. Data on variables including food security, meal frequency, dietary diversity, income, food support, age, sex, residence, employment status, educational level, occupation, marital status, head of the house hold, social support and family size were collected using a pretested interviewer administered Amharic version structured questionnaires and opportunistic infections were collected using record review.

2.4. Data Processing and Analysis

Data were edited, coded and entered in to Epi data 3.1 and exported to SPSS window version 16.0 for analysis. Further, data cleaning (editing, recoding, checking for missing values, and outliers) was made after exported to SPSS. The data analysis ranges from the basic description to the identification of potential predictors of food insecurity. Bi-variate analysis and multivariable logistic models were used to show the relation between food insecurity and various associated factors. The basic descriptive summaries of patients’ characteristics and outcome of interest was computed. Accordingly, simple frequencies, measure of central tendencies and measure of dispersions were computed. Finally, all explanatory variables that results (P < 0.25) with the outcome variable were entered in to multivariable logistic regression model using backward likely hood ratio method to identify independent predictor of food insecurity. P-value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant and odds ratio at 95% confidence interval is used to examine the precision and strength of association.

2.5. Measurements

Food insecurity: was assessed by using a short version of the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) developed by the Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance (FANTA) project which was adapted to individual level. Occurrence questions relate to three different domains of food insecurity was used. I. Anxiety and uncertainty about the household food supply. II. Insufficient quality (includes variety and preferences of the type of food). III. Insufficient food intake and its physical consequences. Each of the questions was asked with a recall period of four weeks (30 days). The respondent was first asked an occurrence question that is, whether the condition in the question happened at all in the past four weeks (yes or no). If the respondent answers “yes” to an occurrence question, a frequency-of-occurrence question will be asked to determine whether the condition happened rarely (once or twice), sometimes (three to ten times) or often (more than ten times) in the past four week [10] . It was computed and dichotomized into two categories; which is food insecure and food secure.

Dietary Diversity Score (DDS): a record of the 24 hour recall of all food groups eaten by the respondents was taken and classified into the 12 food groups using the food and agriculture organization(FAO)/Nutrition and Consumer Protection Division recommended questionnaires [11] . It was computed and dichotomized into two categories; which is low dietary diversity score(less than four) and high (greater than or equal to four) dietary diversity score.

Meal frequency: daily eating occasions over the 24-hour period was asked and recorded. It was computed and dichotomized into two categories; which is low (less than four) and high (greater than or equal to four) meal frequency score [12] .

Wealth index: initially, reliability test was performed using the economic variables involved in measuring the wealth. The variables which were employed to compute the alpha value were entered in to the principal component analysis. At the end of the principal component analysis, the wealth index was obtained as a continuous scale of relative wealth. Finally, tercile of the wealth index were created to see the association with food insecurity.

2.6. Data Quality Control

The questionnaires were adapted from previous literatures & modified in to the study context. It were prepared first in English and translated into Amharic, and then retranslated back to English by an expert who is fluent in both languages to maintain its consistency. Training was given for data collectors and supervisor on objective of the research, how to collect the data through interviewing approach, and data recording. Pre testing of the questionnaires was made on 17 ART care clients in the nearby Woreda health centre a week prior to the actual survey. Consequently, based on the feedback obtained from the pre-test, questions which need clarification were revised. Daily the data were strictly revised for completeness, accuracy and clarity by the supervisors and principal investigator. In addition, the data were thoroughly cleaned and carefully entered in to computer using Epi data version 3.1 using double entry verification.

2.7. Ethical Consideration

Prior to data collection, ethical approval were obtained from ethical review committee of Jimma University, College of Public Health and medical sciences and submitted to Hadiya zone Health Bureau, Nigist Elienie Mohammed Hospital, Hosanna health centre administrators and other concerned bodies to obtain their co-oper- ation. Verbal consent was taken from each participant after the purpose of the study explained. They were told to withdraw at any time from responding to questions if they are not interested to respond. Participants were informed that all the data obtained from them will be kept confidential using codes instead of any personal identifiers.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic and Economic Characteristics

A total of 385 adult people on HAART were participated in the study giving a response rate of 97.72%.Out of 385 respondents the largest numbers of participants, 49.4% were in the age group of 25 - 34 years with the mean age of the respondents was 34.71 (±9.4) years. Larger proportion of the respondents (64.7%) were female by sex and (65.2%) from Hosanna City, (59.2%) were Hadiya by ethnicity. Regarding wealth status, (48.6%) were poor by economic situation. Two hundred thirty two (60.3%) were protestant by religion, one hundred ninety four (50.4%) were married, (27.3%) had a family size (>5) and (58.4%) attended secondary and lower education. Two hundred six (53.5%) were employed by occupation, 36.1% were lived with their parents, and (92.7%) didn’t have any food support from any organization and (90.4%) didn’t have any money support from any organization. One hundred fifty one (39.2%) diagnosed with opportunistic infections in the past two weeks before the survey (Table 1).

3.2. Prevalence of Food Insecurity, Dietary and Health Characteristics

Overall, 260 (67.5%) of participants were food insecure. Females were most affected by food insecurity (66%). Three hundred fifty seven (92.7%) of respondents didn’t get food support. The proxy indicators used to support food insecurity like food diversity and meal frequency showed a significant numbers of people on ART took less than the mean eating occasions and food diversity, which were (84.9%) took low meal frequency and (69.4%) took inadequate diversified food in the past 24 hour period. One hundred fifty one (39.2%) participants were diagnosed with opportunistic infections in the past two weeks before the survey (Table 2).

Table 1. Socio-demographic and economic characteristics of respondents taking antiretroviral therapy at ART clinics of Hossana town, Hadiya zone, Southern Ethiopia, from January 1, 2015 to February 30, 2015.

*Adventist (1), catholic (8); **Silte (21), Oromo (10), Tigre (5) and wolayta.

Table 2. Food insecurity, dietary and Health characteristics of respondents taking antiretroviral therapy at ART clinics of Hosanna town, Hadiya zone, South Ethiopia, from January 1, 2015 to February 30, 2015.

3.3. Predictors of Food Insecurity among Respondents Taking Antiretroviral Therapy

After controlling the effects of confounding variables, variables which were significantly associated on the bivariate analysis with food insecurity with P-value < 025 (place of residence, educational status, marital status, wealth status, occupation, getting food support and getting money support) were fitted into multivariable logistic regression model by backward likely hood ratio method. Four variables were identified to be independent predictors of food insecurity among people on ART. These are lower educational status, absence of food support, unemployment, poor and middle economic status. Individuals with educational status of secondary or lower were 1.7 times more likely to be food insecure than those who had college and above educational status [OR = 1.7 (95%CI; (1.06 - 2.72))]. wealth status was the other predictor of food insecurity; individuals with poor economic status were 4.34 times more likely to be food insecure [OR = 4.34 (95% CI; (2.53 - 7.45))] than those with rich; individuals with middle economic status were 4.1 times more likely to be food insecure than those with rich [OR = 4.1 (95% CI; (2.17 - 7.57))], individuals with unemployed occupation status were 1.71 times more likely to be food insecure than those employed [OR = 1.71 (95%CI; (1.06 - 2.74))] and individuals who didn’t get food support were 2.35 times more likely to be food insecure than who got food support [OR = 2.35 (95%CI; (1.02 - 5.39))] (Table 3). Regression diagnostic procedures was carried out and showed no evidence of multi-co linearity and substantial influence from outliers. In addition, there was no interaction effect between the potential predictor variables.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to determine prevalence of food insecurity and identifying its predictors among adult people on antiretroviral therapy. Results of the study showed that people on antiretroviral therapy suffer from food insecurity, majority 260 (67.5%) of the study participants were food insecure which is higher than the reports form study done in British Columbia, Canada [13] where 48% of people infected with HIV were food insecure, and also it is higher than the study done in Jimma, Ethiopia [9] where 63% of people infected with HIV were food insecure This high rate of food insecurity could be due to the variation in the socio economic status where as it is lower than the one reported from Ethiopia [12] [14] ; this difference could be due to measurement difference of food insecurity like in Dire Dawa where measurement was taken at household level while the current study assessed the individual food insecurity experiences of participants. The proxy indicators of food insecurity used in this study to support the assessment of food insecurity also showed that significant number of people on ART (84.9%) and (69.4%) had low mean meal frequency and inadequate dietary diversified food, respectively. Similar findings were documented in Côte d’Ivoire and Uganda [14] - [16] . The results of this study indentified independent predictors of food insecurity; lower educational status, absence of food support, unemployment, poor and middle economic status were significantly associated with food insecurity at P < 0.05 among adult people on

Table 3. Multivariable logistic regression models predicting food insecurity among people taking anti retroviral therapy at ART clinics of Hosanna town, Hadiya zone, Southern Ethiopia, from January 1, 2015 to February 30, 2015.

*P value < 0.05.

ART. Individuals whose educational status is secondary and lower were 1.7 times more likely to be food insecure than those who educated higher than college and above [OR = 1.7 (95%CI; (1.06 - 2.72))]. This finding is consistent with the findings of other reports [13] [17] . This could be due to uneducated participants had no an opportunity to involve in better income generation activity than educated ones. The finding of this study showed low and middle economic status had significant positive association with food insecurity. Individuals with poor economic status were 4.34 times more likely to be food insecure [OR = 4.34 (95% CI; (2.53 - 7.45))] than those with rich; individuals with middle economic status were 4.1 times more likely to be food insecure than those with rich [OR = 4.1 (95% CI; (2.17 - 7.57))]. This finding is consistent with the findings of other reports [9] [13] . This has significant programmatic implication in that addressing the food insecurity issues among people on ART which is a critical element in achieving a better treatment and clinical outcome for ART. People on ART might even face economic problems due to cut down of their earnings due to frequent sickness days that they have passed. Regarding to occupation, individuals with unemployed occupation status were 1.71 times more likely to be food insecure than those employed [OR = 1.71 (95%CI; (1.06 - 2.74)]. This is due to unemployment promotes poverty, which contributes to food insecurity. This finding is supported by reports of [17] - [19] . Additionally, absence of food support is the other predictor of food insecurity. Individuals who didn’t get food support were 2.35 times more likely to be food insecure than who got food support [OR = 2.35 (95%CI; (1.02 - 5.39))]. This finding is supplemented by the report [20] . The findings of this study should be interpreted with some limitations. Respondents may not tell the real information about their food security status due to the need for aid. As a result of cross-sectional study design nature, the temporal sequence of events cannot be determined. In addition, recall bias and social desirability bias are also potential limitations that may have been encountered in this study.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, people on ART suffer from a significant amount of food insecurity in ART clinics of Hosannatown Southern Ethiopia. The proxy indicators used to support food insecurity; food diversity and meal frequency also showed a significant numbers of people on ART took low meal frequency and inadequate diversified foods. Predictors of food insecurity were having lower education status, absence of food support, unemployment, poor and middle economic status. This calls for integration of ART programs with food insecurity interventions at health facilities level. Improving socio-economic situations, focusing in food support and involving in income generation strategies are recommended to mitigate further vulnerability people on ART in coping with food insecurity. Further studies with different study design are needed to address the problem of food insecurity.

Acknowledgements

I gratefully acknowledge the study participants, supervisors and data collectors for the information provided, without which this work would not have been possible. The funders had no role in the study.

Competing Interests

I declare there is no competing interests.

Cite this paper

Mekuria Asnakew, (2015) Food Insecurity: Prevalence and Associated Factors among Adult Individuals Receiving Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) in ART Clinics of Hosanna Town, Hadiya Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Open Access Library Journal,02,1-9. doi: 10.4236/oalib.1101800

References

- 1. (1986) World Bank: Poverty and Hunger: Issues and Options for Food Security in Developing Countries. World Bank, Washington DC.

- 2. Alaimo, K., Briefel, R.R., Frongillo Jr., E.A. and Olson, C.M. (1998) Food Insufficiency Exists in the United States: Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). American Journal of Public Health, 88, 419-426.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.88.3.419 - 3. WHO, UNAIDS and UNICEF (2011) GLOBAL HIV/AIDS Response Epidemic Update and Health Sector Progress towards Universal Access. Progress Report.

- 4. (2011) EDHS: Central Statistical Agency (CSA): Ethiopia, Addis Ababa, CSA.

- 5. Crush, J., Frayne, B. and Grant, M. (2006) The Regional Network on HIV/AIDS, Livelihoods and Food Security/International Food Policy Research Institute/Southern African Migration Project. IFPRI, Washington.

- 6. Castleman, T., Seumo-Fosso, E. and Cogill, B. (2004) Food and Nutrition Implications of Antiretroviral Therapy in Resource Limited Settings. Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project (FANTA) Academy for Educational Development, Report No. 7, Washington DC.

http://www.fantaproject.org/publications/tn7.shtml - 7. (2009) World Bank and UNAIDS: The Global Economic Crisis and HIV Prevention and Treatment Programmes: Vulnerabilities and Impact. World Bank and UNAIDS.

http://www.unaids.org - 8. FANTA and WFP: Food Assistance Program in the Context of HIV, Washington DC, FANTA and WFP.

http://www.unscn.org/layout/modules/resources/files/Food_Assistance_Context_ - 9. Ayele, T., Tefera, B., Fisehaye, A. and Sibhatu, B. (2012) Food Insecurity and Associated Factors among HIV-Infected Individuals Receiving Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy in Jimma Zone Southwest Ethiopia. Nutrition Journal, 11, 51.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-11-51 - 10. Coates, J., Swindale, A. and Bilinsky, P. (2007) Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for Measurement of Household Food Access: Indicator Guide. Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project, Academy for Educational Development, Washington DC.

http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/eufao-fsi4dm/doc-training/hfias.pdf - 11. FAO (2007) Nutrition and Consumer Protection Division: Guidelines for Measuring Household and Individual Dietary Diversity. FAO, Rome.

- 12. Seifu, A. (2007) Impact of Food and Nutrition Security on Adherence to Anti-Retroviral Therapy (ART) and Treatment Outcomes among Adult PLWHA in Dire Dawa Provisional Administration.

http://etd.aau.edu.et/dspace/bitstream/123456789/861/1/Thesis_Abiy%2520Se - 13. Normén, L., Chan, K., Braitstein, P., Anema, A., Bondy, G., Montaner, J.S. and Hogg, R.S. (2005) Food Insecurity and Hunger Are Prevalent among HIV-Positive Individuals in British Columbia, Canada. Journal of Nutrition, 135, 820-825.

- 14. Asnakew, M., Hailu, C. and Jarso, H. (2015) Malnutrition and Associated Factors among Adult Individuals Receiving Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy in Health Facilities of Hosanna Town, Southern Ethiopia. Open Access Library Journal, 2, e1289.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/oalib.1101289 - 15. Béchu, N. (1998) The Impact of AIDS on the Economy of Families in Côte d’Ivoire: Changes in Consumption among AIDS-Affected Households. In: Ainsworth, M., Fransen, L. and Over, M., Eds., Con-Fronting AIDS: Evidence from the Developing World, European Union, Brussels, 341-348.

- 16. Bukusuba, J., Joyce, K. and Roger, G. (2007) Food Security Status in Households of People Living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) in a Ugandan Urban Setting. British Journal of Nutrition, 98, 211-217.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0007114507691806 - 17. Nord, M., Hooper, M.D. and Hopwood, H. (2008) Household-Level In-come-Related Food Insecurity Is Less Prevalent in Canada than in the United States. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition, 3, 17-35.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19320240802163498 - 18. Rose, D. and Charlton, K.E. (2002) Quantitative Indicators from a Food Expenditure Survey Can Be Used to Target the Food Insecure in South Africa. Journal of Nutrition, 132, 3235-3242.

- 19. Campa, A., Yang, Z., Lai, S., Xue, L., Phillips, J.C., Sales, S., Page, J.B. and Baum, M.K. (2005) HIV-Related Wasting in HIV-Infected Drug Users in the Era of Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 41, 1179-1185.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/444499 - 20. Louise, C., Yuchiao, C., Gregory, J. and Kenneth, A. (2010) Food Assistance Is Associated with Improved Body Mass Index, Food Security and Attendance at Clinic in an HIV Program in Central Haiti: A Prospective Observational Cohort Study. AIDS Research and Therapy, 7, 1-8.