Creative Education 2011. Vol.2, No.3, 226-235 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. DOI:10.4236/ce.2011.23031 Factors Affecting South African District Officials’ Capacity to Provide Effective Teacher Support Bongani D. Bantwini1, Nolutho Diko2 1Department of Elementary & Early Childhood, Kennesaw State University, Kennesaw, USA; 2Human Sciences Research Council, ESD, Pretoria, South Africa. Email: bbantwin@kennesaw.edu Received March 19th, 2011; revised April 13th, 2011; accepted May 2nd, 2011. The role of district o f f icials as education reform agents is unden i able. Through perspectives analyses, we exp l o r e factors that affected the capacity of eight South African districts to provide effective teacher support during the last implementation of natural science reforms. We argue that district officials’ capability and reality issues are some of the factors that are likely to determine the success or failure of reforms. Further, they have the gravity to nullify the efforts to improve school performances. Lastly, we propose ways to bridge the gap between theory and practice and strategies t o promote partnership between district officials and schools. Keywords: School Districts, District Officials, Curriculum Spec ialists, Curriculum Reforms, Natural Science, Science Education, South Africa Introduction The significance of local school districts in mediating be- tween schools and the government is undeniable (Abele, Iver, & Farley, 2003; Anderson, 2003; Hightower, Knapp, Marsh, & McLaughlin, 2001; Spillane, 2000, 2002). Their influential role, which includes ensuring quality teaching and learning, effective assessment, increased learner performance, and achievement, to mention but a few, is indispensable (Anderson, 2003; Iver, Abele, & Elizabeth, 2003). As the literature shows, school dis- tricts are key elements and authorized agents that oversee and guide schools (Massell, 2000). They are the vital institutional actors in educational reforms (Rorrer, Skrla, & Scheurich, 2008), and the major sources of capacity building for the schools (Massell, 2000). These district functions and responsi- bilities are true but also in the South African context. The South African school districts are the intermediaries between the Na- tional and Provincial Departments of Education and the local schools, and their officials play a fundamental role of oversee- ing the implementation of all new policies developed by the National Department of Education and implemented by the nine Provincial Departments of Education. Roberts (2001) describes the primary function of school districts in South Africa as two- fold: to support the delivery of curriculum in schools and to monitor and enhance the quality of learning experiences offered to learners. He argues that district offices have a particular role to play in working closely with local schools and ensuring that local educational needs are met. As he explains, in supporting the primary function of the district, there are five possible areas of operation: policy implementation; leading and managing change; creating an enabling environment for schools to operate effectively; intervening in failing schools; and offering admin- istrative and professional services to schools and teachers. Fur- thermore, Roberts believes that these different areas of opera- tion should be aligned to support the district’s primary purposes, teaching and learning. Despite the critical role played by school districts, South Af- rican school improvement literature continues to show that districts and their officials hardly receive sufficient attention on their role in the curriculum reform process (Chinsamy, 2002), creating deficiencies in our comprehension of the struggles confronting the new policy implementation. The neglect of the district offices and their officials, as Murphy and Hallinger (2001) and Massell (2000) caution, can be done at the peril of the new curriculum and policy reform implementation at the contextual level. Thus, research on districts and their officials will provide a crucial puzzle piece necessary to understand and achieve success in every new reform policy. Spillane (2000) argues that the successful implementation of instructional re- forms depends in some measure on the broader policy envi- ronment in which classrooms are nested, a complete terri tory of the school district. In South Africa, as Chinsamy (2002) con- tends, the National and Provincial Department of Education have successfully formulated empowering educational policies but their implementation has been disappointing. The gap be- tween policy formulation and implementation has been re- garded as the primary reason for the failure of transformation in education (Chinsamy, 2002; Jansen, 2002). Chinsamy high- lights that between the Provincial Department of Education and the school stands the district office, where he believes the an- swers seem to be pointing. Through interview analyses, this paper explores the perspec- tives of intermediate phase (grades 4 - 6) district officials1 from the Eastern Cape Province in South Africa regarding their chal- lenges with the Natural Science2 reform implementation. This curriculum reform, commonly known as the Revised National Curriculum Statement (RNCS), was launched in 2002, resulting from recommendations made by a team that reviewed and re- 1This paper uses “district officials” to refer to curriculum specialists in natural science; science, mathematics, and technology education district coordinators; and natura l science distr i ct subject advisors. 2Natural Science is science education at the primary level.  B. D. BANTWINI ET AL. 227 vised the previous curriculum, Curriculum 2005 (DoE, 2002). This paper therefore investigates the following: 1) factors that hinder or facilitate district officials’ capacity to provide effec- tive support to natural science teachers in their implementation of the new curriculum in classrooms and 2) their perspectives regarding changing the status quo of reform implementation in classrooms. South African district officials’ perspectives are seldom heard voices, yet constitute nuggets of knowledge that play a critical role in the implementation of new curriculum policies. They constitute comprehension of the intricacies in- herent in the reform implementation process. Thus, understand- ing officials’ perspectives is essential because they are the key support for teachers at the local level, responsible for ensuring that they comprehend the new policies by providing them with a vision, interpretation, focus, policy coordination, and above all, with ensuring the desired success (Corcoran, Fuhrman, & Belcher, 2001). Moreover, Rorrer, Skrla, and Scheurich (2008) reveal that the previous line of research has been informative; however, it leaves us without an understanding of the complex- ity intrinsic in district-level, systemic reform. In discussing these perspectives, this paper will begin by presenting a brief review of the international literature on the school districts’ role and their officials, as well as the critique leveled against them. This will be followed by a synopsis of South African school districts and their officials, intended to situate the reader in the context of the reported study. Next, we describe the study methodology, contextual background, and data analysis. This will be followed by presentation of the re- search findings, which will focus on three key themes: district officials’ workload versus what is feasible for them, school reality issues, and district officials’ perspectives on changing the status quo in the implementation of curriculum reforms. The next section will discuss these findings, with an emphasis on the need for the South African National Department of Educa- tion to heed such challenges as they have the gravity to nullify the efforts to improve teaching and learning in schools and negatively impact on teacher and student performances. Then we draw conclusions that propose ways to bridge the gap be- tween theory and practice and strategies to promote effective partnerships between district officials and schools. International Literature on the School District Role and Its Officials The literature indicates the existence of various views re- garding the role that school districts and their officials play (Anderson, 2003; Hightower, Knapp, Marsh, & McLaughlin, 2001; Rorrer, Skrla, & Scheurich, 2008; Spillane, 2000, 2002). These views include those that endorse the critical role played by the district and its officials; those that raises some concerns about districts; and those that speaks to the neglect in the studying of districts a s essential players in the systemic reforms. Hightower, Knapp, Marsh, and McLaughlin (2001) highlight that the different conceptions of what constitutes a school dis- trict include the idea that districts are geographic entities repre- senting a designated area and a set of schools contained within these boundaries. These authors view districts as legal entities required by state law to provide education to all students re- gardless of race, ethnicity, socio-economic background, and disability within the attendance boundaries. Other researchers view districts as implementers of state policies (Marsh, 2001); as professional learning laboratories (Stein & D’Amico, 2001); teacher educators for beginning teachers as they struggle with the daily decisions about what and how to teach (Grossman, Thompson, & Valencia, 2001); and as boundary spanners in the context of collaborative education policy implementation (Honig, 2006). In addition, they also affect school capacity by initiating a variety of other policies that shape the way professional de- velopment is conducted (Youngs, 2001). Collective ly, these sc h- olars strongly emphasize the significance and need for school districts and their officials in the accomplishment of the rollout of new reforms or mandates. Hightower et al. (2001) argue that districts are responsible for the development and enforcement of functions, including attendance, transportation, educational goals, instructional guidance, personnel, operation, and main- tenance of facilities, as well as teacher professional develop- ment. Additionally, the district officials play an essential role in ensuring the success of new mandates and reforms filtered by the government as they strongly influence the strategic choices that schools make to improve teaching and learning (Massell, 2000). Rorrer, Skrla, and Scheurich (2008) further view a dis- trict, which comprises vital institutional actors, as an organized collective that is bound by a web of interrelated and interde- pendent roles, responsibilities, and relationships that facilitate systemic reforms. Despite the consensus on the vital role played by districts and their officials, some literature shows that advocates against the local school districts also exist (Abele, Iver, & Farley, 2003; Tyack, 2002). Tyack argues that in the United States of Amer- ica these advocates, federal activities, hardly see the need for local school districts. Citing Myron Lieberman (1960), Tyack note that these advocate perceive local districts as obstacles to reform and the main source of “the dull parochialism and at- tenuated totalitarianism” of American schooling. These advo- cates also highlight that the local school boards were excluded in most of the critical decision making and policy signing processes of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) enacted in 1965 in the US, which serves as a revelation of how highly valued the local districts (Tyack, 2002). Tyack states that as part of excluding local districts, policy analysts recently focused attention on every level of government but local districts; as they view them as ineffective and obsolete and deserving to be abolished. According to Corcoran, Fuhr- man, and Belcher (2001), some critics have even argued that districts are inherently incapable of stimulating and sustaining meaningful reforms in teaching and learning because of their political and bureaucratic character. Additionally, some re- formers view the districts as problems and identify a criticism that districts play no significant role as they are inconsistent with sound policy and are just ineffective bureaucratic institu- tions (Marsh, 2001). To other critics, as Marsh (2001) indicates, districts have become overly politicized and unresponsive to the public, teachers, and students. A further observation about dis- tricts and their officials was made by Spillane (2000), who found that district officials sometimes contribute to the non implementation of new reforms by the teachers, especially when they do not fully comprehend the vision of the reforms. Though Spillane values and supports local school districts, he asserts that district official’s interpretation of the reforms mes- sage is an important explanatory variable in accounting for implementation.  B. D. BANTWINI ET AL. 228 Adding to these views about school districts are Rorrer, Skrla, and Scheurich (2008), who in their review of Smith and O’Day’s (1991) seminal work on systemic school reform point to the neglect of the role of local school districts in reform. These authors argue that the role of school districts was un- deremphasized in all three of these reform waves (see Smith and O’Day’s, 1991); rather, the research emphasis has been directed towards schools, teachers, states, and other elements involved in the reform process. Rorrer, Skrla, and Scheurich argue that over the past 20 years research studies on districts have been relatively fewer in number and discontinuous com- pared to research on schools as the center of reform. Further- more, they argue that the neglect by many researchers, practi- tioners, and policy makers alike to acknowledge the nested nature of schools within districts and the district’s instrumental role in systemic re form appears remarkable. Despite the criticism and constriction and neglect of local district control, Tyack (2002) argues that the public still trusts local officials more than state and federal government officials or representatives. Increasing numbers of leaders are insisting that public education be deregulated and that local districts recapture more power to make decisions about schooling in their communities. Spillane and Thompson (1997) argue that the notion of local capacity needs to be rethought in light of the extraordinary demands for teaching imposed on teachers and others by the current wave of reform in science, mathematics, and other subjects. These authors argue that district capacity to support ambitious reforms consists of human capital, which involves knowledge, skills, and dispositions of leaders within the district; social capital, which involves social links within and outside the district, together with norms and trust to support open communication; and financial resources, which include allocation of staffing, time, and materials. This brief literature review clearly shows that districts and their officials are crucial stakeholders in the education enterprise. Schools and teachers can do as much but requires districts officials for more policy direction and various supports. Thus, investigating district offi- cials’ perspectives about curriculum reform issues merits the efforts, since they are expected to be conversant with issues that facilitate or hinder successful implementation of curriculum reform at the local level. Understanding such issues will assist in bridging the existing gap between theory and practice and therefore promote coherent (new) reform implementation. Synopsis of South African School Districts Although a great deal of literature on school dist ricts and their officials is commonly found in ot her countries, So uth A fr ic a s ti ll has a knowledge deficiency in that area (Chinsamy, 2002; Nar- see, 2006). There is knowledge deficiency regarding how dis- trict officials’ collaborate as well as the factors that hinder their capacity to provide effective support to schools and teachers. Some scholars only hint on the challenges that district officials are confronted with in the process of supporting teachers with- out providing deep analysis of the situation (Bantwini, 2010; Bantwini & King-McKenzie, 2011). The schools’ district role in South Africa has been described as largely neglected (Chin- samy, 2002; Narsee, 2006), and requires more attention. Rob- erts (2001) highlights that the position of South African school districts in the educational hierarchy means that they have great potential to be a vehicle for medium- to large-scale educational reform. He argues that the potential of the district to be the fulcrum around which educational change and improvement pivot lies in the district’s ability to fulfill its core function, which is to support the delivery of the curriculum and to ensure that all learners are afforde d good-quality learning opportuni- ties—the quality of which is evidenced by learner achieve- ment. Despite the limitation of knowledge deficiency, districts and their officials, as in other countries, play an essential role in ensuring the implementation of the stream of education policies promulgated especially during the post-apartheid era (Jansen, 2004). Worth mentioning is that the post-apartheid era is marked by the development and rollouts of new policies in- tended to redress the past injustices committed by the apartheid regime. These efforts are also characterized by the re-definition of certain departments and the roles of their officials. Roberts (2001) highlights that since 1994 there has been considerable debate on the form and functions of district offices and in some provinces these debates have led to the large-scale reorganiza- tion of Provincial Departments of Education and their support- ing bureaucracies at the Provincial, Regional, and District lev- els. Currently, at the apex of the South African education struc- ture is the Department of Basic Education (DBE) and the De- partment of Higher Education and Training (DHET), both re- sulting from the recent split of the then National Department of Education, which occurred in 2009. The Department of Basic Education, which this paper focuses on, is responsible for the primary and secondary education including adult basic educa- tion and training, whereas the Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) is responsible for tertiary education and technical and vocational training (for more details see South Africa Department of Education). The vision of the DBE is to ensure that all South African people have access to lifelong education and training opportunities that will contribute to- wards improving the quality of life and building a peaceful, prosperous and democratic society. The critical role of DBE is to develop education policies that are later filtered to schools through the Provincial Departments of Education (SASA, 1996) and providing a broad management framework for support (DoE, 2005). Generally, it is responsible for matters that cannot be regulated effectively by provincial legislation, and also for matters that need to be coordinated in terms of norms and stan- dards at a national level (DoE, 1999). The National Department provides active assistance to provincial departments in streng- thening their ad ministrative and professional capacity. South Africa is made of nine Provinces, with each compris- ing a Provincial Department of Education. These provincial departments are intended to decentralize education in the coun- try, thus promoting efficiency in the management of all educa- tional activities and issues. Among their many roles, these de- partments are tasked to implement new policies and collaborate with the various school districts within their provinces. They are tasked to coordinate the implementation of a national fr ame- work of support, in relation to provincial needs (2005). Each Province consists of a number of school districts that vary depending on the size of the province and population. The school districts are the governing institutions, the “eyes and ears” of the government, and are led by the District Director.  B. D. BANTWINI ET AL. 229 Depending on the size of the district, the number of schools per district also varies. Though South African school districts play a significant role in many way s, they still la ck a legislati ve framework that spell s out their powers and functions. In Roberts (2001) observations, there has been a historical neglect of the subsystems level of the education system and the disappointing results of previous school improvement approaches. The South African Depart- ment of Education (2005) also acknowledges that in some dis- tricts, there has been no meaningful support for some time. This is particularly true in rural and historically disadvantaged areas. They also note that even if support is available, it is often frag- mented and uncoordinated and to unite it into cohesive practice that works is the challenge (DoE, 2005). The literature indicates that the persistent calls for a legislated district framework over the past decades have not yet borne fruit (Narsee, 2006). The landscape of and the role played by school districts and their officials, their capacity to work with schools and more, is a relatively unexplored area in the South African context, and hence this study. Study Context The reported qualitative study was conducted in eight school districts in the Eastern Cape Province (EC), South Africa. The Province consists of 23 school districts that are grouped into three clusters: clusters A, B, and C. Each cluster is led by a Chief Director, and is composed of a varying number of dis- tricts that are led by District Directors. The District Directors subsequently lead teams of Curriculum Specialists for various subject/learning areas. In some of the Provinces, districts are the smallest units within the education system while in others the smallest unit is a circuit. In the case of the EC, the smallest unit is a circuit and is led by a Circuit Manager. Districts or circuits have varying number of schools (primary and secon- dary schools). The school districts’ sampling was purposive, and was based on their geographic positioning, which ensured that most parts of the province were covered. Also, the will- ingness of the District Directors to undertake the study in their districts served as another motivating criterion. Research Design Initially, the reported study focused on eight Natural Scienc e (NS) district officials, however, only six were successfully formally interviewed. The other two district officials had casual discussions with the researcher and were not formal inter- viewed, though they had consented on it. This was due to time constraints resulting from their busy schedules during the data collection period. The formally interviewed officials, four males and two females, all over forty years of age with varied teach- ing experiences, were working closely with the Natural Science teachers at the intermediate phase (grades 4 - 6). Their respon- sibilities involved providing teachers with curriculum policies from the National Department of Education; interpreting the policies in comprehensible way to the teachers; supporting teachers with the content knowledge; conducting workshops as part of teacher professional development; monitoring the im- plementation of the new curriculum policies in schools; support and monitor the functionality of curriculum structures, to men- tion but a few. District officials were interviewed using semi-structured in- terviews that lasted between 60 - 90 minutes. According to Hargreaves (2005), interviews offer an approach that gives access to personal experiences, some flexibility in responding to the interview topics, and probing of people’s account of these, and an initial opportunity to identify patterns of similar- ity and experiences. Some of the interviews were tape recorded with participant’s permission, while in other cases interview notes were taken. The recorded interviews were later tran- scribed verbatim. The data coding and analysis followed an iterative process, as recommended by Miles and Huberman (1994). Miles and Huberman describe various steps that include reading and affixing codes to the transcript notes while noting reflections or other remarks in the margins; sorting and sifting through these materials to identify similar phrases, relationships between variables, patterns, themes, distinct differences be- tween subgroups and common sequences; isolating these pat- terns and processes, commonalities and differences; while gradually elaborating a small set of generalizations that cover the consistencies and; confronting those generalizations with a formalized body of knowledge in the form of constructs (p. 9). During this process, the research questions were used to inform the emerging the mes and issues which are discussed below. To enrich our data, four schools from each of the eight dis- tricts, totalling 32, were also sampled with the assistance of district officials, as they were more familiar with the context than the researchers. Among the selection criterion used was the requirement that the sampled schools should be in prox- imity with each other in order to ease the movement from one school to the other. From each district the targeted schools were public schools comprising farm3 schools, township4, rural5, and urban6 schools. The other criterion was that each school should comprise grades 4 - 6 natural science classes. To triangulate the district officials’ information, about 108 natural science teachers were asked to complete a questionnaire, of which 55 (51%) were returned completed. The question- naires focused on the teachers’ demographic details and quali- fications, which gave us an idea of who the district officials were working with. It also focused on the teacher learning, new curriculum reform, classroom implementation and their district professional development. All the completed questionnaires were imported into the Statistical Package for the Social Sci- ences (SPSS) and frequency distributions was conducted. In this paper the data from the questionnaires will not receive much attention as it does in another article. Additionally, eleven teachers (8 females and 3 males) were interviewed using a semi structured interviews to further learn about the new curriculum reforms in South Africa, the class- room implementation process and whether or not they were receiving the desired support from their district officials. The interviewed teachers were purposively sampled based on their teaching experiences, number of years in the same district, their willingness to be interviewed, to mention but few. These inter- 3Farms school are schools situated in farms and accommodate mostly chil- dren of the farm workers. 4Township schools, on the other hand, are public schools located in the townships. 5Rural schools a re public schools locate d in the rural areas. 6And urban schools are public schools in the urban areas.  B. D. BANTWINI ET AL. 230 views were audio recorded with their permission and later tran- scribed verbatim. The data coding and analysis followed the iterative procedure as suggested by Miles and Huberman (1994). Reference to these interviews will occasionally be made to present clarit y on c ertain issues , wh enever neces ary (s ee Tab le 1). Ethical Issues The permission to conduct the study was requested from and granted by the Eastern Cape Department of Education Superin- tendent, as per their research policy requirement or procedure. Throughout the paper, pseudonyms are used to protect the iden- tity of the school districts, the district personnel, and the teach- ers. In the following, we discuss the the matic issues that emerged from the data analysis. Factors Affecting District Officials’ Capacity to Provide Effective School Support Capability versus Feasibility at the Gro und Level The district offi cials ci ted th eir w orkload in relat ion to w hat is feasible to accomplish at the district level as a critical challenge in most districts, impacting their capacity to provide effective support to their teachers. Partly contributing to this factor was the large number of schools, ranging from 200 to 500, that offi- cials were responsible to provide with profession al dev elopment on new curriculum reforms; the need to monitor the reform implementation process; and the effort to provide ongoing school-based support, just to mention a few. Justice and success in providing a better service to all their NS teachers was said to be a utopian dream. The common belief was that the district officials’ work was characterized by difficulties as they were thinly stretched in their work. Further aggravating the situation was the fact that some officials were also working with teachers of two different phase levels, the intermediate phase (grades 4 - 6) and the senior phase (grades 7 - 9), making it difficult to accomplish their goals. Consequently, some schools and teach- ers had never been visited to discuss and resolve some of the challenges they were confronted with. Ironically, the South Africa Department of Education’s (2005) continue to argue that educators and their institutions need constantly to learn and grow, and must have ongoing support to achieve this. Therefore, their function is to provide the necessary infra-structural and human resource support for success through the district-based support team. District officials complained about their job descriptions and the related organogram (management structure), viewing them as also causing a handicap in the nature of support they were offering teache r s: “I think the other thing that handicaps the kind of support that we give to schools is the structure of the organogram itself. For example I find it funny that we could stretch the intermedi- ate phase and senior phase. There is a set of about six different grades (grades 4 - 9) and with one person who is to give suppor t to these teachers; that stretch from intermediate phase to senior phase! You know, there is no one who has that broad, that kind of expertise to give a very genuine… (Mr. Zama-Zama, 2008).” Combining the intermediate and senior phase level under the leadership of one district official was perceived as a serious challenge. District officials cited that if the individual was not well or away for one reason or another, that meant that both phase levels would suffer, since no one else was there to assist them. This concern was raised in light of the historical chal- lenges that the province was still grappling with, of teachers with inadequate content knowledge, the weak culture of teach- ing and learning in most schools, and more. As a solution to this challenge, district officials believed that it would be ideal if district officials were responsible for just one phase level. For example, if there was a subject advisor responsible for the in- termediate phase and another for the senior phase, a similar case as in the Further Education and Training band (FET) in their districts, schools would be better served. “Instead, what they have done in the organogram is to ‘put a lot of generals without foot soldiers’; for example, there could be coordinators, there is a coordinator for the intermediate phase and that coordinators has got no Subject Advisors. There is one for senior phase and there is just one line of Subject Ad- visors, therefore these have got two bosses. I mean if there are in each and every area, there is one Subject Advisor for natural science for intermediate and Senior phase, there is a boss for senior and there is a boss for intermediate phase, so this poor guy has to report in two bosses (ha ha ha ha, laughing). You have two bosses. So you work very bad because you become very busy like a lunatic and it’s difficult, making no sense. Also, appointing a general before there are even foot soldiers, there is a general with no army what does, (ha ha ha, laughing), it does not make no sense. (Mr. Zama-Zama).” The workload issue was juxtaposed with the insufficient re- sources, particularly in the form of policy documents, for all the teachers. As one of their tasks, dis trict officials are responsible to provide teachers in their learning area with the relevant and current policy documents. They have to ensure that all the teachers are clear about the policies and are also in possession of those documents as their teaching references. Nevertheless, six years later after the launch of the Revised National Curriculum Statement, there were still natural science teachers who did not possess a copy of a policy document. Explaining the challenges Table 1. Research design summa ry. Participants Sampling Method # of Participants Gender Instruments District Officials Convenienc e sampling 8 5 males & 3 Fe males Formal & I n fo r mal inter views Teachers Purposeful Sampling 11 3 Males & 8 Females Formal inte r vi ews Teachers Purposeful Sampling Target 108 teachers & 55 (51%) Completed the Questionnaires 5 Males & 50 Females completed the Questionnaire Questionnaires  B. D. BANTWINI ET AL. 231 resulting from this lack, one district official said: “If you are not reading, then you have to be dependent on the information given to you in a forum or workshop. Therefore you are unable and you are not assisting yourself in terms of reinforcing that information by further reading. (Mr. Dock, 2008). A person gradually shall have to, when coming across a problem, consult a relevant policy document and read about it. We cannot seat and read with them, unfortunately, so people have got to learn to read. (Mr. Dock, 2008).” The challenge of a policy document shortage resulted in most teachers relying on district officials for information regarding the new reforms. According to the district officials, their pro- vincial office was to be blamed for this matter as they were supposed to provide all the teachers with policy documents, something that was not happening. Despite the fact that most teachers relied on district officials for most information, meetings between these groups for the purpose of professional development or other activities also seldom took place. The district officials were supposed to meet with the teachers at least every semester, but that proved to be difficult, given the large numbers of schools and teachers they had. “If you could deal with rural schools and some of them if you could ask if, who their subject advisor is, they will say, we don’t know any person like that. There are schools in the dis- trict who do not know that I am employed to support them. They have never seen my face, let alone know my name (ha ha ha, laughing) and yet my brief is to support those schools. (Mr. Zama-Zama).” Several teachers also confirmed the issue raised in the above quote and said: “In the case of Natural Science, who is responsible for it I don’t know. We don’t even have the Natural Science work- shops, the last time we had one I think it was in the nineties, just to attend them. Right now I don’t want to lie; I don’t know who is responsible for Natural Science. (Mrs. Crak, Natural Science teacher) I don’t know about Natural Science, I have never been to a workshop on it. If they had a workshop, then it means they did not inform us. I have taught in this district since 1985 and have never been to a Natural Science workshop. (Mrs. Duplesis, Natural Science teacher).” Responding to a question about how schools were imple- menting the new reforms, one district official said: “I don’t have a broader scope of the schools in my district, but this year I managed to visit three schools out of the 466 because I work with grades 4 - 9. (Mr. King)” The neglect of teachers at the primary school level for the sake of grade 9, which is the exit level in the phase, was viewed as a critical challenge. This was a challenge because teachers at the primary school level needed additional support since they were tasked with the d evelopment of a solid foundation in t he learning of science at the lower levels of schooling. The district officials argued that it is difficult to do justice to all the schools in the district, let alone the phase, when you are thinly spread. Reality Aspects of School s at District Level Among the factors that were incapacitating di strict officials in their mission to support schools were teachers who still did not have a clear understanding of the new curriculum, an issue that has received considerable attention in several studies including one by Bantwini (2010). Expressing this concern about these teachers, Mr. Dock said: “If you are having a confident educator in class, then your chances are very good that you are going to be imparting some difference in your learners. But if teachers are still not yet sure, then chances are great that you putting that educator to a situa- tion that is frustrating five days a week. Then you are invariably creating some destruction to your learners.” Concurring with the above idea is Davis (2003) who con- tends that without the necessary subject matter knowledge, it is hard for teachers to learn strategies and techniques needed to respond to students’ thinking about the subject in ways that facilitate their learning. The district officials noted that during workshops teachers would claim to understand the vision of the policy, however, when they are faced with challenges in their classroom practice, it was said nobody was there to assist them. This was a challenge that retarded progress among teachers. Despite the challenges, some officials were optimistic that teachers were doing their best they could in relying on what they learned from workshops. This handicap, as the officials mentioned, has resulted in some teachers avoiding implement- ing things they did not understand. They also perceived this as the only option teachers had, to either try to do what is expected of them as prescribed by the policies or else revert to their comfort zone where they felt they don’t understand; not be- cause they resisted the policy but because they could not ade- quately interpret it. In Elmore and McLaughlin (1988) observa- tion, teachers response to new proposals for change most often are deeply rooted in the nature of their work and in the profes- sional norms, standards and concerns that guide practice and support professional learning. However, despite acknowledg- ment of this challenge, officials felt that there was no time for retraining and re-skilling teachers since there was not even enough time to conduct ongoing professional development workshops in their districts. Teachers were also said to be struggling with assessment. Apparently, they had a different perception about Outcomes Based Education, in that students were supposed to do every- thing without considering that it was still their responsibility as facilitators to plan for everything that students should do. Some teachers were said to be still planning for one learner, the aver- age performing learner, instead of planning for three learners; the best, average, and poor performing learner in their class- rooms. Accompanying this challenge was the fact that some teachers, when talking about grouping, would think that learn- ing and teaching was actually occurring in their classrooms. When asked what they were doing to help those teachers strug- gling to implement the curriculum, the district officials admit- ted that it is their responsibility to intervene and assist them to resolve whatever issue a teacher might have. However, time was their worst enemy, as well as a lack of resources to attend to the struggling teachers. From the interviews’ analysis, it was evident that most of these teachers were not receiving the due attention. This certainly is against the literature that argues that few teachers can move from a staff development program di- rectly into the classroom and begin implementing a new pro- gram or innovation with success (Guskey, 2002). Also common in most districts were teachers who were  B. D. BANTWINI ET AL. 232 comfortable in teaching certain areas like biology or physics, while not comfortable in teaching the other areas within the Natural Science content. These teachers were cited as only conducting demonstrations and also theorizing in their teaching of natural science, defeating the purpose of developing students who will be prob lem solve rs and criti cal think ers. Man y teachers were viewed as lacking confidence in the teaching and learning of science in general. The Department of Education was also blamed for not providing them with the adequate teaching ma- terial for natural science areas. “Firstly, what I have observed with our teachers in the inter- mediate phase le vel, it i s people who ar e not confident about the subject matter, for many reasons. One of them being that be- cause of job shortage, they found themselves having to grab whatever job is giv en to th em or w hatever locatio n in the school . Very few of them are doing science because it is in their blood, they love it. Some another fraction, another portion of them, they really love science but now they did not have good background. Although they never been given that opportunity to be well founded in the subject (Mr. Matilu, 2008).” The other common issue from the districts was that most natural science teachers were teaching science without love or passion for the learning area. Teacher s lacked a d rive th at should propel them to consult their district officials when encountering implementation challenges in their classroom. Teachers were viewed as not being willing to go that extra mile in their work. For example, during workshops, teachers would take whatever they were told without question. Several issues we re attributed to these issues including the fact that the Department of Education was not providing teachers with ad equate support material. Most schools could not afford to purchase all the science equipment that would ensure that effective teaching and learning were taking place. As a result, district officials were not happy about the status of science teaching and learning in their schools, as some teachers lacked subject content knowledge, a basic re- quirement for teaching science education. “They (teachers ) are on the ground level, they are not doing well at all. Take from what I said about their background, it looks like others are just on ly sustaining life, they are driving the course, they are driving the time so that from Thursday of the month up to the end they receive their salaries and it’s over. There is nothing else they can say about science. They are just doing it because they are told, most of them. So because of that they seem to be stagnan t, ther e is no p rogress; you can see it b est in a workshop (Mr. Matilu).” The level of teachers’ subject content knowledge was viewed as a critical component in the teaching of science, also co rrelated with the poor learner performance in science subjects. Until this issue was properly addressed, the status quo in science was said to be one of the ongoing challenges. Nonetheless, how this was to be “addressed” was said to be not yet clear. “You find educators of varying background in science and therefore even if you introduce a very down to earth concept, it will take more than it ought to if they were well founded in natural science (Mr. Matilu).” The lack of acco u ntabil it y p rev io usl y pres en t was viewe d as a contributing factor and hindering district officials’ capacity to effectively support the teachers. In schools, school principals were said to be afra id of teach ers who were just doing ever ything as they preferred. These teachers were said to be doing their work for the sake of doing it, without the p assion and dedication that should be expected. “Take for, example, if you can visit one of the schoo ls without informing the teachers about your visit. You will find that the teacher is not there and you find that the principal cannot even fully account for their absence. They just cover for the teachers but if you check the paper work you will find that there is nothing written (Mr. King).” Aggravating the challenge was the lack of authority over the teachers. Data analysis reveals that in other schools the head of the subject department would be someone who is maybe a lan- guage teacher, who hard ly knows an ything abou t scien ce. In th is case the teachers would not be challenged about whatever they were doing in the learning area. Perspectives on Changing the Status Quo of Curriculum Implementation As a solution to their challenges, the district officials sug- gested that the Eastern Cape Provin cial Department of Education will have to make r adical changes in ever y leve l of th e educa tion system in order to change the status quo. These radical changes would have financial implications, which usually determine the success of m any initiativ es. The key changes will need to include a decrease in th e nu mber o f schools t hat e ach d istrict offic ial has to support. For example, instead of supporting 20 0 - 500 schools, each official should hav e 40 - 75 schools. This was viewed as an ideal and reasonable number of schools to support as the offi- cials will be able to assist several of the currently struggling teachers. Consequently, that would improve even their working relationship with the teachers and also improve their under- standing and implementation of the new natural science cur- riculum reforms. Such a move will also enable officials to visit schools and have conversations with teachers that will lead to resolving some of the issues and challenges teachers are cur- rently experiencing. The district officials also believed that if each phase level could be assigned an official rather than having one official overseeing two phase leve ls as was current ly the cas e, that would provide them relief. Furthermore, they believed that district officials should be deployed based on their experiences, educa- tional qualifications and strengths. For example, if you have intermediate phase level teaching experience, then you should be in charge of that phas e level and not be asked to oversee, say, the Further Education and Training level, which you hardly have any experience with. In this way, all the district officials would be comfortable to assist teachers using their previous experi- ences and background knowledge; and in return, teachers are likely to develop confidence and trust in you based about the knowledge of your previous experiences. The district officials believed that provision of adequate ma- terial and r esources suc h as polic y document w as als o a potenti al solution to some of the challenges they were confronted with. They wished th at the Provin cial Department of Education would stop providing policy document copies per schools but rather per teachers since some schools had their grades levels in different sites. This would ensure that each teacher has a copy and would eliminate excuses even from those teachers who do not usually read the material. Though district officials feel this way about policy document, Bantwini (2009 ) found that some teachers who  B. D. BANTWINI ET AL. 233 possessed policy documents never read them; rather they left them to gather dust on the shelves. Probing reason for not reading the new curriculum documents, teachers cited lack of time among the issues. In Elmore and McLaughlin (1988) ob- servation, the requirement to learn new behaviors, especially when they involve modification or replacement of an existing routine, threaten a teacher who is already well-organized self- concept and established level of accomplishment. These authors argue that the external demands are largely ineffective in stimu- lating teacher learning, thus motivation to learn new things should also come from within. Discussion and Conclusion As Spillane and Thom pson (1997) argue, the factors that make up a district’s capacity to support ambitious i nstructional reform are highly intertwined and therefore the capacity to support instructional reforms should best be understood as a complex and interactive configuration. Spillane and Thompson contend that growth in one component depends crucially on, and fre- quently contributes to, growth in the others. That observation points to the complexity of the education system and reforms and the necessity for the synchronization of the various ele- ments that eventually contribute towards student success, an ultimate goal for every education. Chisholm and Leyendecker (2008) cautions that while there is a need for different and bet- ter learning outcomes in all sub-Saharan African educational systems, the scope of change is frequently underestimated. The underestimated scope of educational change is also depicted by the findings of this study; the need for changes that appear to be primarily on the curriculum policies with no correspondence on the district support structure. Ironically, South Africa, as Jansen (2004) contends, possesses great and phenomenal education policies. However, he reminds us that policy is not practice and argues that while an impressive architecture exists for democ- ratic education, South Africa has a very long way to go in order to make the ideals concrete and achievable within educational institutions, a sentiment also highlighted by the findings in this study. This paper concurs with Chisholm and Leyendecker (2008), who argue that curriculum reforms probably work best when curriculum developers acknowledge existing realities, classroom cultures, and implementation requirements. In this case these realities exist on both sides: the district office and the schools. Obviously, that requires an understanding and sharing the meaning of the educational change, providing for adapta- tions to cultural circumstances, local context, and capacity build- ing throughout the system. Furthermore, it means that policies need to be flexible enough to fit particular school contexts and needs (King, 2004). From the findings, one of the critical issues facing school districts is the deficit of human capacity, hindering and inca- pacitating the few officials from effectively servicing schools and the teachers. The lack of human capital has negative im- pacts on the expected results, especially in the implementation of the ongoing curriculum reforms in South Africa. Considering the district officials’ and schools/teacher ratio, it would be un- realistic to expect a profound amount of change in the current teaching and learning in schools. The South African Depart- ment of education has on several occasions mentioned that there are deficiencies in the culture of teaching and learning in their schools. Based on that observation, one would expect drastic moves towards addressing that issue. You would expect a drastic increase in the number of district officials, with nec- essary skills to work with teachers at all levels; and you would also expect provision of adequate resources for district officials and the teachers in order to perform their various tasks. How- ever, what is transpiring in the districts goes against the de- partment of education (2005) policy that the key function of the districts is to assist education institutions, including schools, to identify and address barriers to learning and promote effective teaching and learning. As they argue, this includes classroom and organizational support, providing specialized learner and educator support, as well as curricular and institutional devel- opment and administrative support. How possible is this task when there is lack of sufficient human power? This typically points to policy development that does not correspond with reality. It is imperative as Davis (2003) suggests that much thought and effort needs to be given to how teachers learn to teach; what teachers know; how their knowledge is acquired; how it changes over time; and what processes bring about change in individual teacher practices as well as deep and long lasting change in science classroom. This is crucial if new re- forms are intended to be worthwhile and not political symbols. Several district officials complained about their organogram as propelling their challenges. A similar observation was made by Narsee (2006), who argues that the central dilemma for education districts in South Africa is their structural conditions. Narsee emphasizes that school districts operate at the intersec- tion of dual, related dichotomies of support and pressure, cen- tralization and decentralization. However, she believes that it is only through conscious engagement with these dichotomies, as well as by active, positive agency on district-school relation- ships, will districts be able to straddle, if not resolve, the ten- sions between the policy, support, and management roles ex- pected of them. The research of Walberg and Fowler Jnr. (1987) suggests that bigger districts yield lower achievements. This is probably true as the findings reveal that it is difficult for offi- cials to assist schools that are in dire need of help. According to Anderson (2000), districts that believe that quality of student learning is highly dependent on the quality of instruction organize themselves and their resources to support instructionally focused profe ssional learning for teac hers. S c ho o l s , as Fullan (1992) argues, cannot redesign themselves; districts play an important function in establishing the conditions for continuous and long-term improvements for schools as they control and coordinate all the development projects imple- mented in their schools. This paper argues that if the school districts under discussion value student quality teaching and learning, drastic changes will have to be effected. The com- plexity in such changes is that they will also affect policies not only at the local district level but higher up in the educational hierarchy. Chinsamy (2002) concludes that “it is the district office—the way it is comprised, its functions and roles, its management and its vision and the way it operates, its limita- tions and its possibilities—that is pivotal to successful school improvement”. The undisputable critical function of school districts cannot be overlooked anymore. Expressing their con- cern, Chisholm and Leyendecker (2008) note that the local cultural and contextual realities and capacities as much as im- plementation requirements still appear to be overlooked. We  B. D. BANTWINI ET AL. 234 believe that the overlook on the current crisis confronted by the district shortage of human capacity will be an ideal recipe for an ongoing disaster. Resolving that crisis by filling the vacant positions and correcting the district official teacher ratio will be the first step in curbing some of the school reality challenges slowing the reform implementation process. This paper strongly suggests that more research focusing on school districts and their mandates/roles should be undertaken. This will help unearth all the issues requiring immediate atten- tion in order to correct the schooling crisis that confronts South Africa. This paper acknowledges that the data used here may not be sufficient to generalize about the conditions of all the districts in the country. Nonetheless, this study provides a win- dow for viewing how other districts are surviving during this education transformation era. References Abele, M., Iver, M., & Farley, E. (2003). Bringing the district back in: The role of central office in improving instruction and student achievement. Baltimore, MD: Centre for Research on the Education of Students Placed at Risk, John Hopkins University. Anderson, S. E. (2003). The school district role in educational change: A review of the literature. Toronto: International Centre for Educa- tional Change, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education. Bantwini, B. D., & King-McKenzie, E. (2011). District officials’ as- sumptions about teacher learning and change: Hindering factors to curriculum reform implementation in South Africa. International Journal of Education, 3, 1-25. Bantwini, B. D. (2010). How teachers perceive the new curriculum reform: Lessons from a school district in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. International Journal of Educational Development, 30, 83-90. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2009.06.002 Bantwini, B. D. (2009). A Researcher’s experience in navigating the murky terrain of doing research in South Africa’s transforming schools. Perspective s i n Education, 27, 30-39. Chisholm, L., & Leyendecker, R. (2008). Curriculum reform in post- 1990 Sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Educational Development, 28, 195-205. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2007.04.003 Corcoran, T., Fuhrman, S. H., & Belcher, C. L. (2001). The district role in instructional improvement. Phi Delta Kappan, 83, 78-84. Davis, K.S. (2003). “Change is hard”: What science teachers are telling us about reform and teacher learning in innovative practices. Science Education, 87, 3-30. doi:10.1002/sce.10037 Department of Education (2005). Conceptual and operational guide- lines for the implementation of inclusive education: District-based support teams. Pretoria. Fiske, E. B., & Ladd, H. F., (2004). Elusive equity: Education reform in post-apartheid South Africa. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. Grossman, P., Thompson, C. S., & Valencia, S. W. (2002). Focusing the concerns of new teachers: The district as teacher educator. In A. M. Hightower, M. S. Knapp, J. A. Marsh, & M. W. McLaughlin (Eds.), School districts and instructional renewal (pp. 129-142). New York: Teacher College, Columbia University. Hargreaves, A. (2005). Educational change takes ages: Life, career and generational factors in teachers’ emotional responses to educational change. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25, 967-983. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2005.06.007 Hightower, A. M., Knapp, M. S., Marsh, J. A., & McLaughlin, M. W. (2002). The district role in instructional renewal: Setting the stage for dialogue. In A. M. Hightower, M. S. Knapp, J. A. Marsh, & M. W. McLaughlin (Eds.), School districts and instructional renewal (pp. 1-6). New York: Teacher College, Columbia University. Jansen, D. J., (2002). Political symbolism as policy craft: Explaining non-reform in South African education after apartheid. Journal of Education Policy, 17, 199-215. doi:10.1080/02680930110116534 Jansen, D. J., (2004). Race and education after ten years. Perspective in Education, 22, 117- 128. Lemon, A. (2004). Redressing school inequalities in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies, 3 0, 269-290. doi:10.1080/0305707042000215392 King, M. B. (2004). School- and district-level leadership for teacher workforce development: Enhancing teacher learning and capacity. In M. A. Smylie, & D. Miretsky (Eds.), Developing the teacher work- force: 103rd yearbook of the NSSE Part I (pp. 303-325). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Marsh, J. A. (2002). How districts relate to states, schools, and com- munities: A review of emerging literature. In A. M. Hightower, M. S. Knapp, J. A. Marsh, & M. W. McLaughlin (Eds.), School districts and instructional renewal (pp. 25-40). New York: Teacher College, Columbia University. Massell, D. (2000). The district role in building capacity: Four strate- gies. Philadelphia: Consortium for Policy Research in Education, Graduate School of Educa t i on, University of P e n n s ylvania. Massell, D., & Goertz, M. E. (2002). District strategies for building instructional capacity. In A. M. Hightower, M. S. Knapp, J. A. Marsh, & M. W. McLaughlin (Eds.), School districts and instructional re- newal (pp. 43-60). New York: Teacher College, Columbia Univer- sity. Miles, M. B., & Huberman, M. A. (1984). Qualitative data analysis: A sourcebook of new methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. Murphy, J., & Hallinger, P. (2001). Characteristics of instructionally effective school districts. Journal of Educational Research, 81, 175- 181. Nakabugo, M. G., & Siebörger, R. (2001). Curriculum reform and teaching in South Africa: Making a “paradigm shift”? International Journal of Educational Development, 21, 53-60. doi:10.1016/S0738-0593(00)00013-4 Roberts, J. (2001). District development—The new hope for educational reform. Jo h an ne s bu rg: JET Education Services. Rorrer, A. K., Skrla, L., & Scheurich, J. J. (2008). Districts as institutional actors in educat iona l reform . Educational Administration Quarterly, 44, 307-358. doi:10.1177/0013161X08318962 Speck, M., & Knipe, C. (2005). Why can’t we get it right? Designing high-quality professional development for standard-based schools. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. Spillane, J. P., & Callahan, K. C. (2000). Implementing state standards for science education: What district policy makers make of the hoopla. Journal of Research in Science Teachi ng, 37, 401-425. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2736(200005)37:5<401::AID-TEA2>3.0.C O;2-D Spillane, J. P. (2000). Cognition and policy implementation: District policy makers and the reform of mathematics education. Cognition and Instruction, 18, 141-179. doi:10.1207/S1532690XCI1802_01 Spillane, J. P. (2002). Local theories of teacher change: The pedagogy of district policies and programs. Teacher College Record, 104, 377- 420. doi:10.1111/1467-9620.00167 Spillane, J. P., & Thompson, C. L. (1997). Reconstructing conceptions of local capacity: The local education agency’s capacity for ambi- tious instructional reform. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analy- sis, 19, 185-203. Spillane, J. P., & Thompson, C. L. (1998). Looking at local districts’ capacity for ambitious reforms. Philadelphia, PA: Consortium for Policy Research in Education. Stein, M. K., & D’Amico, L. (2002). The district as a professional learning laboratory. In A. M. Hightower, M. S. Knapp, J. A. Marsh, & M. W. McLaughlin (Eds.), School districts and instructional re- newal (pp. 61-75). New York: Teacher College, Columbia Univer- sity. Tyack, D. (2002). Forgotten players: How local school districts shaped american education. In A. M. Hightower, M. S. Knapp, J. A. Marsh, & M. W. McLaughlin (Eds.), School districts and instructional re- newal (pp. 9-24). New York: Teacher College, Columbia University. Walberg, H. J., & Fowler, J. T. (1987). Expenditure and size efficien-  B. D. BANTWINI ET AL. 235 cies of public school districts. American Educational Research Asso- ciation, 16, 5-13. Narsee, H. (2006). The common and contested meanings of education districts in South Africa. Pretoria: Faculty of Education, University of Pretoria. http://upetd.up.ac.za/thesis/available/etd-03232006-094442/unrestrict ed/00front.pdf

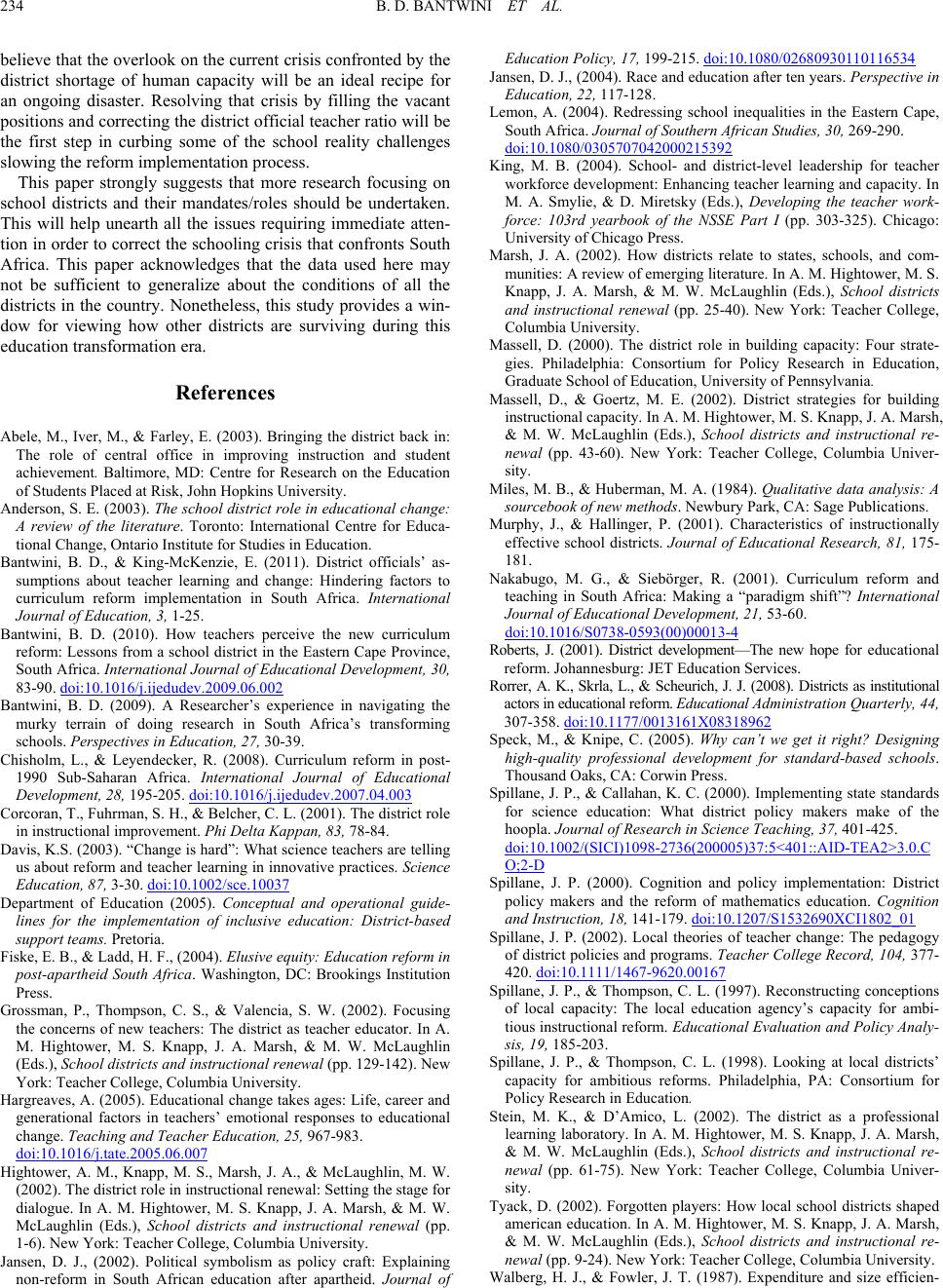

|