Open Access Library Journal How to cite this paper: Noori, N., Fatemi, M.A. and Najjari, H. (2014) The Relationship between EFL Teachers’ Motivation and Job Satisfaction in Mashhad Language Institutions. Open Access Library Journal, 1: e843. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/oalib.1100843 The Relationship between EFL Teachers’ Motivation and Job Satisfaction in Mashhad Language Institutions Najmeh Noori*, Mohammad Ali Fatemi, Hossein Najjari Department of English, Torbat-e-Heydareih Branch, Islamic Azad University, Torbat-e-Heydareih, Iran Email: *nj_noori@mail2student.com Received 4 August 2014; revised 20 September 2014; accepted 22 October 2014 Copyright © 2014 by authors and OALib. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativ ecommon s.org/l icens es/by/4.0/ Abstract The scarcity of research on EFL teachers’ job satisfaction and motivation prompted this study which aimed at identifying the relationship between EFL teachers’ motivation and job satisfaction. To achieve this goal, the researcher selected 250 EFL teachers randomly with different years of experience in Mashhad language institutions. To collect the required data, the researcher em- ployed Teacher’s Motivation Questionnaire (TMQ) to elicit sources of motivation of EFL teachers and Teachers’ Job Satisfaction Questionnaire (TJSQ) to elicit the job satisfaction levels. The results revealed a significant positive relationship (r = 0. 44 , p < 0.01) between EFL teachers’ motivation and job satisfaction in Mashhad language institutions. Keywords Teachers’ Motivation, Teacher Job Satisfaction, EFL Teachers, Mashhad Language Institutions Subject Areas: Education, Linguistic s, Psy chology, Sociol ogy 1. Introduction In the process of development of any educational system around the world, job satisfaction is vital. Special training, a high level of education, focus competencies, educational resources, and strategies determine whether or how educational success and performance happen [1]. As [2], “there is a growing body of evidence that when teachers feel good about their work, pupil achievement improves” (p. 73). Job satisfaction not only affects teacher roles but also affects student achievements. Consequently, the issue of teacher job satisfaction needs to * N. Noori et al. OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100843 2 October 2014 | Volume 1 | be studied very carefully from every viewpoint a nd a ttitud e [3]. 1.1. Statement of the Problem In the discussions of motivation in SLA, special attention is often devoted on the language learner. Research on motivation reported during the last three decades in the field provides evidence for this. However, with the re- cent findings of a close relationship between teacher motivation and student motivation in many learning con- texts [4], the phenomeno n of teacher motivation also needs empirical investigations to discover the facts about the nature of thi s relatio nship in di fferent l anguage l earning contexts. In many educational contexts, teachers increasingly leave the profession after a few years in service. In addi- tion studies worldwide have found that teachers are exposed to the highest level of job related stress and that they are less satisfied with their jobs than any other professional group. Research into teacher satisfaction has a great effect and value because job dissatisfaction causes little commitment and productivity, reduced ability to meet student needs, certain degrees of psychological disorders and high levels of stress related disability [5]. [6] suggested that language learner motivation is highly recommended both in educational and cultural con- text. With t his clai m, it is possible to assume t hat the di fficulty in learning a language as well as lear ning other subjects poses more challenges to language teachers too. Language teachers, on the other hand to other subject teachers in ho mogene ous clas ses, freq uently have to keep the mselves in formed o f many differ ent soc io-cultural and affective factors which ascertain the success of the learners. 1.2. Significance of the Study Due to the fact that there is not enough research on the relationship between EFL teacher job satisfaction and motivation, first and fore most, this stud y is set ou t to in vestigate ho w EFL teachers feel wi th their j o b, what mo- tivate s them, how they manage to sustain their motivation a nd remain in the teaching profession. According to [7], understanding the determinants of ESL teacher motivation in the country is significant for three reasons: it can i mpr ove st ud e nt mot iva t io n; i t ca n he lp to the co untry’s langua ge ed uc at io n r eforms; and it can cause the sa- tisfaction and accomplishment of teachers themselves. 1.3. Definition of Key Terms 1.3.1. Teacher Motivation There are many motivation theories for explaining for just about everything that happens to people at work. Many definitions of moti vatio n exi st in t he literat ure a nd nu merous deb ates surro und the se definitio ns. T his lack of clarity on how to define motivation quickly created problems for researches. Different perspectives arose on how to define motivation. As a way to deal with the confusion over the definitional and conceptual issues with motivation construct, researchers switched their way to facet specific motivation. Work settings have many of these specific motivations present at any given time. At the amount of practical application, understanding that teachers are motivated by the necessity to achieve ideal-oriented goal is of no real use. For practical purposes, much non specificity is needed and attention must be inclined to what, precisely, motivates rather than at wh y it motivates [8]. In schools, motivation among teachers is required for the objective of effective teaching learning process. Thus efficient teaching somewhat is the co nsequence of moti vation [9]. Students’ attitudes and behavior, the task of teaching affected teacher s’ motivation, com mitment to teaching and respondents’ attitudes to wards var- ious language institution based factors, towards their work and their relationship with students are interpreted in this research. Finally, a few studies of motivation have exa mined healt h related outco mes such as stress and psy- chological well-being. F or instance, motiva ti on has be en l inked t o s t ress and psychological well-being [5]. 1.3.2. Teacher Job Satisfaction The underlying conceptual problem connected with researching job satisfaction is that there is no agreed defini- tion of t he term. A variety of definitio ns is evide nt, and the d isparit y amongst these r elates bo th to the de pths o f analyses of the concept and to interpretation of it [8]. Job satisfaction is reall y a multidi mensional and d ynamic construct affected by many fa ctors concerning individ ual characteristics, to options that come wit h the working context and to specific facets of the job [10]. In general job satisfaction equates with how someone feels about his job [11]. Based on [12], job satisfaction identifies “a state of mind encompassing all those feelings deter- mined by the extent to which the individual perceives her/his job related needs to be being met” (p. 294). And N. Noori et al. OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100843 3 October 2014 | Volume 1 | similarly, teacher satisfaction “refers to a teacher’s affective relation to his or her teaching role and is a function of the perceived relationship between what one wants from teaching and what one perceives it is offering to a teacher” ([13], p. 359). Teacher motivation and job satisfaction wi ll vary construct s b ut inextricably linked a s one influences the o ther. In most cases, motivation describes to an innate stimulus for behavior and action, an internal drive which in- spires us to behave in the light of a specific context, whereas job satisfaction identifies a product of a behavior or action in the ligh t of a specific context [11]. Also two sets of factors appear to affect teachers’ ability to perform effectively: 1) Work context factors referred to the teaching environment. 2) Work content factors referred to teaching ([14], p. 56). 1) Work Context Factors These are factors extrinsic to the teacher. [14] defi n es it as follow: They include working conditions such as class size, discipline conditions, and accessibility to teaching mate- rials; the grade of the supervision; and basic psychological needs such as money, status and security. When present, these factors prevent dissati sfaction. But thes e factors may not have a lo ng motiva tional effect or result in improved teaching. A survey conducted by the National Center for Education Statistics found that teacher compensation, including salary, benefits, and supplemental income, showed little relation to long-term satisfaction with teaching as a career (p. 56). 2) Work Content Factors Work content factors are intrinsic to the job itself. They include opportunities for professional development, recognition, challenging and varied work, increased responsibility, achievement, empowerment, and authority. Three major areas that connect with teachers’ job satisfaction: a) Feedba ck may be the factor most strongly linked to job satisfaction, yet teachers typically receive almost no accurate and helpful feedback regarding their teaching. b) Autonomy is freedom to produce collegial relationships to perform tasks. c) Collegiality is experiencing challenging and stimulating work, creating school improvement plans, and leadi ng curriculum development groups ([14], p. 56). 1.3.3. EFL Teachers In T ESOL, tho se who teac h Engl ish i n non-nat ive En glis h co untries ( excep t UK, USA, Austra lia, N ew Zea land and Canada) are often categorized as EFL teachers. The term ESL is only used to introduce language teaching in native cont exts [15]. 1.3.4. Language Institutions Lang uage Ins titutio ns offer courses for all levels of language proficiency and all age groups. Some for eign la n- guages are taught in these institutions. The institutions use up-to-date text-books and professional teachers hold ing M A or B A in T EFL o r other field s. T he de mand for Engl ish i n Ir an ha s grown rapidly over the last two dec ades and language institutions have more important role than schools and unive rsities. 1.4. Limitations of the Study This study’s focus was on teachers who teach in language institutions. It is possible that the result of it would not b e ap plic ab le to schoo ls or univer siti es. And t he c urre nt st udy wa s d one in I ra nian c onte xt; c onse que ntl y, it s results cannot be generalized to other contexts. The sample did not include teachers who move away from par- ticipating or who did not complete a greater portion of their questions. The study was also delimited to partici- pants who were present in the classroom at the time of distribution of the questionnaires. Some teachers took questionnaire ho me and collected several later, therefore, there was no control the degree to which teachers col- laborated or discussed the questions and influenced each other. In addition, faced specific approach used in this research. The faced specific approach has been almost subsumed under specific topical area rather than com- pri s ing an increasingly strong base for a broad job s atisfact i on and motivation in and of itself. 1.5. Review of Literature Gibson, et al. (1989) commented that motivation and job satisfaction are connected but are not synonymous. N. Noori et al. OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100843 4 October 2014 | Volume 1 | They certified that job satisfaction is one ar e a of the motivational proce ss. While motivation is chiefly concerned with purposive behavior, job satisfaction assesses the performance developed by experiencing different job ac- tivities and helpful effects. It is possible that an employee may present low motivation from the organization’s perspective yet enjoys every facets of the job. This state represents high job satisfaction (as cited in [16]). [16] also gave reasons that a highly motivated employee might also be dissatisfied with every facets of his or her job. Research on teacher job satisfaction has identified a variety of factors that affect job satisfaction and teacher motivation. According to [17], these factors divided into two domains: intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Also ex- trinsic factors divided into two factors: school facto rs and system factor s. 1.5.1. Factors Intrinsic to Teaching Based on some studies such as [12] [17]-[21], it is concluded that the key factors found to subscribe to teacher job satisfaction relate with the specific work of teaching, that is, dealing with children, developing warm per- sonal relatio nships with c hildr en, the intellec tual challen ge of te achi ng, auto no my a nd in dep end ence a nd ha vi ng opportunitie s to e xp e rience new ideas. Teachers, no matter of sex, teaching experience, position held and location and kind of school, have been found to acquire their greatest satisfaction and experience a great sense of success through dealing with and for young people and by enabling young people to understand their potential, experience success and grow into re- spo nsible ad ults. T eachers u niversa lly have alread y been fo und to value st udent e nthusias m and resp onsi veness as an important factor of their own enthusiasm while listing students’ low motivation as a discourager. Quite simply, in the same way dealing with students a nd affectin g their lives is prob ab ly the most central and po werful supply of satisfaction for teachers, dealing with difficult and demotivated students could have negative conse- quenc es for teacher satisfaction and could be the origin of emoti onally exhausting and discouraging exp eriences. 1.5.2. Factors Operating at the School Level The second supply of factors affecting job satisfaction include largely school based factors such as school lea- dership, school climate and participation in decision making, support from leadership and peers, school infra- structure, the school’s relation using its local community, workload, staff supervision, class size, school com- munication networks [17]. These are factors extrinsic to the task of teaching but can become po werful dissatis- fiers when absent or problematic. According to some studies such as [2] [17] [22] [23], the significance of a school culture with strong support networks that promotes collaboration, communication, collegiality has been identified by many studies as a central determinant of teacher job satisfaction. 1.5.3. Factors Operating at the System Level The third supply of factors includes those coming from the wider social context, the state government and the system. They are factors which are extrinsic to the job itself and include imposed educational change, increased expectations on schools to cope with and solve social problems, community’s opinion of teachers, the image of teachers portrayed in the media, level of support by the system to implement curricular changes, support servic- es to teachers, promotion prospects, status of teachers, conditions of service, salary [5]. Based on [13], Teachers generally regard job dissatisfaction as mainly originating from work overload, poor pay and perceptions of how teachers are regarded by society. To [5], these extrinsic, systemically based factors have been found as powerful dissatisfier s which detract from or prevent from the core business of teaching and which can meaningfully affect teachers’ motivation and their wish to stay in teaching. 1.5.4. Teacher Job Satisfaction and Teacher Efficacy [18] stated that another important construct in the study of teacher job satisfaction which affects how teachers deal with and manage sources of job dissatisfaction is the concept of teacher efficacy. Teacher efficacy refers to the self-perception of teaching competence; it is the self-belief of teachers that they can affect positive effect on their students’ growth and success. Teachers with a high sense of efficacy have been found to show greater ea- gerness for and co mmitment to teaching, displa y greater willingness to deal with students’ e motional and beha- vioral difficulties, show greater need and readiness to carry out and find better ways of teaching and generally exhibit higher levels of job satisfaction. A good reason for the impo rtance of teac her efficac y and its rela tion to job satisfaction is provided by [2] who stated: N. Noori et al. OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100843 5 October 2014 | Volume 1 | Teacher efficacy has at least t wo imp orta nt moti vational out co mes: Firstl y it in flue nces the kind of challenges and environments teachers are prepared to face in their work. If teachers believe that teaching difficult subject matter o r wor ki ng wit h co l leagues is so bad to deal with it (lo w self-efficac y) the y will re fuse t he se s it ua tions on the side of less challenging and finally less beneficial learning contexts. Secondly, strong self-efficacy beliefs influence effort and persistence. Teachers with high self-efficacy quickly recover after something unpleasant setbacks in their teaching efforts and this fast recovering is vital in helping students to keep their diligence and self-belief (p. 3). Based on some s tudies such as [12] [17]-[21], it is concluded that the key factors found to subscr ibe to teacher job satisfaction relate with the specific work of teaching, that is, dealing with children, developing warm per- sonal relatio nships with c hildr en, the intellec tual challen ge of te achi ng, auto no my a nd in dep end ence a nd ha vi ng opportunities to experience new ideas. According to some studies such as [2] [17] [22] [23], the significance of a school culture with strong support networks that promotes collaboration, communication, collegiality has been identified by many studies as a central determinant of teacher job satisfaction. [21] stated teachers generally re- gard job dissatisfaction as mainly originating from work overload, poor pay and perceptions of how teachers are regarded by society. 1.6. Research Question and Hypothesis Based on the above mentioned issues, to our knowled ge, this study posed the following researc h question: Q1: Is there any relationship between EFL teachers’ motivation and their job satisfaction in Mashhad lan- guage institut i ons? H01: There is no significant relationship between EFL teachers’ motivation and their job satisfaction in Mashhad language institutions. 2. Method 2.1. Participants and Sett i ng s The sample for this study included 250 teachers selected by random sampling technique from among 14 lan- guage institution s in the North-east of Iran, Mashhad (fall 2012). The sample consisted of teachers with varying age (63% from 22 to 30, 37% from 31 to 40), gend e r (53 % female, 47% male ), work e xp erience (45% from 6 to 10 years of experience, 25% from 1 to 5 years of experience, 26% from 11 to 15 years of experience and 5% more than 16 years of experience), level of education (34% a Master’s degree, 61% Bachelor’s degree and 5% lower than BA), and field of education (71% Engli s h majors and 29% studied in other fields). The following tables showed the characteristics of the survey participants. 2.2. Procedure In order to recognize EFL teachers’ motivation and job satisfaction, the researcher administered the piloted questionnaires (TMQ and TJSQ) in paper and pencil formats randomly to 320 EFL teachers who taught lan- guage s kill s co ur ses in d if fer e nt l eve l s in d i ffe re nt M a sh ha d l ang uage i nst i tut i ons . P r io r to da ta colle ction, lette rs were d ispatc hed to the princip als of se lecte d langua ge insti tution s, explai ning the signi ficance of the s tudy, a nd requesting that t hey allow thei r teachers to pa rticipate. Pr ior to the day of distrib ution of questionna ires, partici- pants were alerted of the meaning and need for the study. The participants took the questionnaires home, filled them in and submitted them to the researcher over the following weeks. Reservations were made for a second day to collect data from participants who could not be present on the first day. A total of 320 questionnaires were distributed, 50 were not returned, 20 were incomplete. The total number of acceptable data from teachers therefore was 250. To receive reliable data, the researchers explained the purpose of the study to the participants, and a s sured them that t heir i nformation would be confid ential. The quantitative data for the current study included EFL teachers’ responses to the close-ended questions on the teacher motivation questionnaire (TMQ) and job satisfaction questionnaire (TJSQ). These responses were entered into a data file and analyzed statistically using the computer software program Statistical Package for Social Sciences. Statistical analyses carried out on the data included Pearson product-moment correlation coef- ficient and Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. N. Noori et al. OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100843 6 October 2014 | Volume 1 | 2.3. Instrumentations The questionnaires that administered in this study were taken from an article which conducted a research about EFL teacher motivation and job satisfaction in Greek. Based on a conceptual framework (factors ope rating at the school based level, factors relating to wider domain of society, school culture, students attitudes and behavior, the task of teaching affected teachers’ motivation, commitment to teaching and the concep t of self-efficacy), [5] developed these questionnaires in Greece. 2.3.1. Teacher Job Satisfaction Questionnaire (TJS Q) This part of the questionnaire asked respondent questions related to their level of satisfaction with various as- pects extrinsic to the task of teaching such as their recognition by students, peers, parents and the wider commu- nity, the ima ge o f teac her s, th eir stat us i n soc iet y, t heir s ala ry, wor king hours , be nef its e tc. T he que stions in this part were measured on a 5 point scale ranging from 1 = highl y sati sfyin g to 5 = highly di ssati sfyi ng. T he Cron- bach’s alpha coefficient of this questionnaire was 0.72 (r = 0.72). 2.3.2. Teacher Motivation Questionnaire (T MQ) This part of the questionnaire elicited respondents’ attitudes towards various language institution based factors, towards their work and their relationship with students. The questions in this part were measured on a 5 point scale ranging from 1 = strongly agree to 5 = strongly disagree. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of this ques- tionnaire was 0.71 (r = 0.71). 2.4. Design Issues Finally, there are issues related to the design of job satisfaction and motivation studies, such as the means by which motivation a nd job satisfaction data a re collected. The predominate methodology used in job satisfaction and moti vation re search i s the use of surve ys. This methodo logy has several limitatio ns regarding its use. Fir st, this type of design is susceptible to same source bias that can artificially inflate relationships. One way around this is to use a split-sample approach where groups are split into subgroups whose responses can be used to sep- arately measure variables in a relationship (e.g., [24]). 3. Results and Discussions Having collected the required data based on the mentioned data collection instruments and procedures, the re- searchers conducted data analysis and tested the hypothesis formulated for the present study. 3.1. Descriptive Statistics of TJSQ Questions This questionnaire investigated teachers’ degree of satisfaction with various factors extrinsic to the task of teaching-namely language institution based factors and especially system based factors (factors of the wider so- cial domain). Questions of this teacher job satisfaction questionnaire were divided into three sections: factors that respondents were satisfied with and factors that are dissatisfied with and factors that were ambivalent. The re searcher used 1 for highly satisfaction, 2 for satisfaction, 3 neither satisfying nor dissatisf ying and 4 for di ssatis- fying. Therefore, the less Mean showed the more satisfaction. 3.1.1. Satisfied Extrinsic Factors Results were presented in descending order, starting from those factors the respondents seemed to be most satis- fied with a nd proce eding to fa ctors they see med less satisfied or dissatis fied with. T he ma jor ity of EFL teachers (see Table 1) in the institutions seemed to be most satisfied with their status as an EFL teacher in their language institution (87.6%) and (M = 1.9440 and SD = 0.54961), the amount of recognition they received for their ef- forts fro m their students (83.6%) and (M = 2.0960 and SD = 0.68165), their status as an EFL teacher in society (55.2%) and (M = 2.2520 and SD = 0.90763), the amount of recognition they received for their efforts from parents and community (48.8%) and (M = 2.3320 and SD = 0.76427), the amount of rec ognition they received for their efforts fro m peop le i n their lan guage i nstit ution (7 0.4%) and (M = 2.3560 and SD = 0.77955). A signif- icant nu mber of teac hers also felt satis fied with their a moun t of recognition they received for their efforts from their employer/institution governing body (65.2%) and (M = 2.4160 and SD = 0.91996), their opportunities for  N. Noori et al. OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100843 7 October 2014 | Volume 1 | Table 1. Descriptive statistics of teachers’ answers to questions related to job satisfaction. Questions HS S NS D Mea n SD Q6 18.0 6 9.6 12.4 1.9440 0.5496 1 Q4 12.8 7 0.8 10.4 6.0 2.0 960 0.6816 5 Q5 25.6 2 9.6 38.8 6.0 2.2 520 0.9076 3 Q3 18.0 30.8 51.2 2.3 320 0.7642 7 Q1 6.4 6 4.0 17.2 12.4 2.3560 0.77955 Q2 11.6 53.6 16.4 18.4 2.4160 0.9199 6 Q12 12. 8 44.8 24. 0 17.6 2.7560 0.6483 7 Q13 6.4 34.0 37.2 22.4 2.7840 0.87380 Note: HS = highly satisfying = 1; S = satisf ying = 2; NS = neithe r sati sfy ing nor di s satisfying = 3 and D = dissatisfying = 4. promotion or advancement (57.6%) and (M = 2.7560 and SD = 0.64837) and the physical working environment of their language institution (infrastructure, resources etc.) (40.4%) and (M = 2.7840 and SD = 0.87380). 3.1.2. Dissatisfied Extrinsic Factors As far as sources of dissatisfaction were concerned (see Table 2), the majority of respondents seemed dissatis- fied with system based factors such as the government’s initiatives for improving the status of EFL teachers (69.6%) (M = 3.6280 and SD = 0.60918) and over 1/3 of the teachers were dissatisfied with the range of profes- sional in-services (36.0%) (M = 3.0760 and SD = 0.80049). Many of the teachers felt dissatisfied with the in- frastructure and resources of their working environment and opportunities for their professional development offer ed by the government. 3.1.3. Ambivalent System Based Factors Teachers felt there was room for improvement in some factors (see Table 3). The results of teacher official working hours were (M = 2.8000 and SD = 1.04900). Participants were divided on this issue: slig htly over 1/3 of the teachers felt dissatisfied with their official working hours (34.0%), slightly under 1/4 of the teachers felt there was room for improvement (24.8%), slightly over 1/4 felt satisfied (28.4%) and (12.8%) of the teachers felt strongly sat isfied. T he next factor that elicite d the followi ng result was benefits such as holidays, ed ucation- al leaves (M = 2.9160 and SD = 0.05108) was a source of dissatisfaction of 1/3 of the respondents (34.8%) and more than 1/4 of the respondents (28.4%) felt that there was room for improvement and the rest of the respon- dents were satisfied. The other factor was public perception of EFL teachers and how they were portrayed in the medi a (M = 2.9240 and SD = 0.72687). Slightly under 1/2 of the respondents (46.8%) expressed a neutral atti- tude feeling neither satisfied nor dissatisfied. The other factor was salary (M = 2.9680 and SD = 0.85903). Par- ticipants were divided on this issue: slightly under 1/2 of the teachers felt there was room for improvement (45.6%) and 28.8% of the tea chers felt dissatisfied and 19.2% felt satisfied and onl y 6.4% fel t hi ghl y sat is fyin g. The final factor was the way that professional associations work the improvement of the ELT profession (M = 3.2000 and SD = 0.71135). Slightly under 1/2 of the respondents (45.6%) expressed a neutral attitude feeling neither satisfied no r dissatisfied. 3.2. Descriptive Statistics of TMQ Questions The second part of the questionnaire investigated teachers’ attitudes towards various language institution based factors such as language institution leadership, language institution climate, support fro m leadership and peers, language institution communication networks. These were factors extrinsic to the task of teaching but can be- come powerful dissatisfiers when abse nt or problematic. In addition, this par t of the questionnaire a lso included statements rela ting to factors intrinsic to the ta sk of teaching such as the qua lity of teacher student relatio nship, teachers’ sense of efficacy and teachers’ feelings regarding their work such as challenge of teaching and com- mitment to teaching which act as powerful sources of motiv ation for teachers. The researcher used 1 for strongly  N. Noori et al. OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100843 8 October 2014 | Volume 1 | Table 2. Descriptive stati s tics of teach ers’ answers to questions of job satisfaction. Questions HS S NS D Mea n SD Q10 28.4 35.6 36.0 3.0760 0.80049 Q9 6.8 23.6 6 9.6 3.6280 0.60918 Note: HS = highly satisfying = 1; S = satisf ying = 2; NS = neithe r sati sfy ing nor di s satisfying = 3 and D = dissatisfying = 4. Table 3. Descriptive stati s tics of teach ers’ answers to questions of job satisfaction. Questions HS S NS D Mea n SD Q15 12. 8 28.4 24. 8 34.0 2.8000 1.04900 Q14 6.4 30.4 28.4 34.8 2.9160 0.05108 Q7 30.4 46.8 22.8 2.9240 0.72687 Q11 6.4 19.2 45.6 28.8 2.9680 0.85903 Q8 17.2 45.6 37.2 3.2000 0.71135 Note: HS = highly satisfying = 1; S = satisf ying = 2; NS = neithe r sati sfy ing nor di s satisfying = 3 and D = dissatisfying = 4. agree, 2 for agree, 3 do n’t know and 4 for disagree. Therefore, the less Mean showed the more agree. 3.2.1. Teachers’ Attitudes towards Language Institution Based Factors According to Table 4, most of teachers felt satisfied with the opportunities and support from language institu- tion admini stration for tr ying out new ideas a nd practices (M = 3.7440 and SD = 0.56546) (80.8% of the teach- ers) and (12.8%) of the teachers answered that they didn’t know. (6.4%) of the teachers agreed that Language institution administration did not support them. Over 1/2 of teachers valued Cooperation with colleagues (M = 2.3840 and SD = 0.78422) (62.4%) , 12.8 % of teachers disagreed with, and 18.8% of teachers answered that they didn’t know. 18.8% of the participants disagreed that their institution provided a collegial supportive environ- ment for them to work in (M = 2.5520 and SD = 0.93959). Less than 1/3 (30.4%) of the participants answered they didn’t know. 38.0% of the participants agreed that their institution provided a collegial supportive envi- ronment for them to work in and 12.8% strongly agreed that their institutio n provided a collegial supp ortive en- vironment for them to work in. Slightly under half of the participants agreed that their work load (M = 2.6800 and SD = 0.96609) was heavy (48.4%). 6.4% felt high pressure, 16.0% of the participants answered they didn’t know a nd 29.2% of the participants disagreed that their work load was heavy. 40.4% of teachers agreed that ex- tra-curricular activities (M = 2.7840 and SD = 0.73996) were as stimulating to them as teaching is, 40.8% of teachers didn’t know and 18.8% of the teachers disagreed. 56.8% of the participants disagreed that administra- tive meetings in language institution (M = 3.2600 and SD = 0.96962) were not helpful in solving teachers’ problems. 18.8% of the participants a nswered that the y didn’t know. 1 8.0% of participants agreed that admi nis- trative meetings in institution were no t helpful in sol vin g teachers’ pro blems. Two stateme nts in this part of the ques tionnaire in additio n were related to tea c her s’ confidence in their ability to use a positive effect on their students’ progress and success. Teachers’ sense of efficacy was an effective mo- tivational factor because assists teachers’ achievement and perseverance in spite of obstacles and problems to investigate and better the quality of their teaching [5]. There were two questions (see Table 5) about self-e ffi- cacy (M = 2.3120 and SD = 0.83313) and (M = 2.2360 and SD = 0.93370). 11.6% of the teachers strongly agreed and 58.0% agreed that they had dealt effectively with the problems of their students. 22.8% of the teach- ers strongly agreed and 42.4% of t he tea cher s agre ed that they ha d po sitive ly inf luenc ed st udent s’ live s thro ugh their teachin g. I t meant that Iranian E FL teachers had a very good self-efficacy. 3.2.2. Teachers’ Attitudes towards Factors Intrinsic to Teaching A look at Table 6 revealed that less than half (41.2%) of the EFL teachers regretted their career choice (M = 2.8840 and SD = 1.08963). Less than half (46.8%) of the p articipants felt t he relations hip with their students as the most rewarding aspect of their work (M = 2.7080 and SD = 0.90444). The negative points about teaching  N. Noori et al. OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100843 9 October 2014 | Volume 1 | Table 4. Descriptive statistics of teachers’ attitudes towards language institution based factors. Questions SA A N D Mean SD Q3 6.0 6 2.4 18.8 12.8 2.3840 0.78422 Q18 12. 8 38.0 30. 4 18.8 2.5520 0.9395 9 Q11 6.4 48.4 16.0 29.2 2.6800 0.96609 Q6 40.4 40.8 18.8 2.7 840 0.7399 6 Q8 6.4 1 8.0 18.8 56.8 3.2600 0.96962 Q1 6.4 12.8 8 0.8 3.7440 0.56546 Note: SA = str ongly agree = 1; A = agree = 2; N = do n’t k no w = 3 and D = disagree = 4. Table 5. Descriptive stati s tics of teach ers’ perceptions of their teaching effic a cy. Questions SA A N D Mean SD Q13 11. 6 58.0 18. 0 12.4 2.3120 0.8351 3 Q15 22. 8 42.4 23. 2 11.6 2.2360 0.9337 0 Note: SA = str ongly agree = 1; A = agree = 2; N = do n’t k no w = 3 and D = disagree = 4. Table 6. Descriptive stati s tics of teach ers’ attitudes towards their work. Questions SA A N D Mean SD Q2 12.8 2 7.2 18.8 4 1. 2 2.8840 1.08963 Q4 6.4 4 0.4 29.2 24.0 2.7080 0.90444 Q5 16.8 22.0 61.2 3.4 440 0.7649 9 Q7 17.6 42.0 40.4 3.2 280 0.7281 0 Q9 24.4 39.6 24.4 11.6 2.2320 0.9496 2 Q10 24. 8 51.6 11. 2 12.4 2.1120 0.9202 4 Q14 12. 8 5.2 27.6 54.4 3.2360 1.02788 Q16 18.4 22.8 58.8 3.4040 0.78181 Q19 18. 0 52.4 29.6 2.4 120 1.09501 Note: SA = str ongly agree = 1; A = agree = 2; N = do n’t k no w = 3 and D = disagree = 4. were not ala rmin g. Onl y 16.8% of the teachers felt emotionally drained from their work (M = 3.4440 and SD = 0.76499). Only 17.6% of the participants agreed that they could not see themselves continuing to teach for the rest of their career (M = 3.2280 and SD = 0.72810) and 42.0% of the participants expressed that there was room for i mpr ove ment. The majority o f the par ticipants expressed total commitme nt to teac hing (M = 2.2320 and SD = 0.94962) (64.0%). The majority of the participants found that teaching increased their self-esteem (M = 2.1120 and SD = 0.92024) (76.4%). More than half of the teachers (54.4%) disagreed that teaching often stressed them (M = 3.2360 and SD = 1.027 88 ). Mor e than ha l f ( 5 8. 8%) of the participa nts disagre ed that the y had felt burn ou t from their work (M = 3.4040 and SD = 0.78181). The majority of the participants found teaching mentally sti- mulating (M = 2.4120 and SD = 1.09501) (70.0%). Table 7 showed that for the majority of teachers, their learners’ ensuing discipline problems (M = 2.3080 and SD = 1.01254), lack of motivation for learning English (M = 2.8520 and SD = 1.03653) and attitude problems (M = 2.4640 and SD = 1.03779) significantly impaired their motivation for teaching and had an impact on the quality of t heir teaching. Research question 1: Is there any relationship between EFL teachers’ motivation and the levels of job satis- faction in Mashhad language institutions? Table 8 showed the relationship between teacher motivation (as measured by TMQ) and job satisfaction (as  N. Noori et al. OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100843 10 October 2014 | Volume 1 | Table 7. Descriptive statistics of teachers’ attitudes towards students. Questions SA A N D Mean SD Q12 22. 8 41.2 18. 4 17.6 2.3080 1.01254 Q17 12. 8 23.6 29. 2 34.4 2.8520 1.03653 Q20 18. 0 40.8 18. 0 23.2 2.4640 1.03779 Note: SA = strongly agree = 1; A = agr ee = 2; N = do n’t k no w = 3 and D = disagree = 4 . Table 8. Pearson corr elation of teacher motivation and job sati sfacti on. Questions SA A Motivation Total Satisfaction Total Motivation Total Pearson Correlation 1 0.440** Sig. (2-Taile d ) 0.000 N 250 250 Satisfaction Tota l Pearson Correla tion 0.440** 1 Sig. (2-Taile d ) 0.000 N 250 250 Note: **Corr elation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tai le d). measured by TJSQ). The Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient was used. The result indicated that there was a significant moderate relationship between the two variables. Thus, the null-hypothesis, that there is no significant re lationship be tween EF L teachers’ motiva tion and the le vels of jo b satisfaction in la nguage insti- tutions was rejected. As the results of Table 8 revealed, there was positive moderate relationship (r = 0.44, p < 0.01) between EFL teachers’ motivation and the levels of job satisfaction in Mashhad language institutions. A positive correlation indicated that higher values on the job satisfaction were associated with higher values of teacher motivation. 4. Conclusions The results of TMQ and TJSQ approved that there was a significant positive correlation between teacher moti- vation and job satisfactio n. This res ult was in line with [5]. This study reinforces the theory that the needs satis- faction or work related needs of employees, if considering national background as not being important, can be grouped based on need theories of motivation [1]. The results of this st udy coincided with results from international research on teachers’ job satisfaction [5] [17] [20] [25] where the most strongl y felt dissatisfiers were facts extrinsic to the task of teaching such as the range of professional in services courses/programs/support offered to EFL teachers and the way that governments work for the betterment of their status, and mostly out of control of teachers and language institutions found within the domain of the state government and the system. The difference of this study with previous studies about job satisfaction and teacher motivation was the con- text o f the stud y. T he previo us resea rches’ c ontext was sc hool b ut in this st udy, the c ontext was langua ge inst i- tutio n. These inst it u tio ns wer e p r iva te a nd had no co n ne cti o n wit h t he go vernment and ma ybe t hi s was wh y t he y were dissatisfied with the systems factors. The other difference of this stud y with previo us (as [5]) was the de- gree satisfaction of teachers about benefits and official working hours. The result of previous studies showed that teachers were satisfied with their benefits and official working hours but in this study teachers were neither satisfied nor dissatisfied. Also nearly half of the teachers reported their work load was heavy. The majority of EFL teachers expressed total commitment to teaching and found that teaching increased their self-esteem they also found teaching mentally stimulating. These results were in line with studies such as [5] [18]. Less than half of the participants felt the relationship with their students as the most rewarding aspect of their work, this result differe d from [5] [12] [17]-[21]. The percentages of questions about teacher stress, feeling burn o ut a nd e mo ti ona ll y d r ai ned fr o m tea c hi ng wer e no t a l a r ming in this rese ar c h. These findings diffe re d from  N. Noori et al. OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100843 11 October 2014 | Volume 1 | the results o f international res earch that teac hers r epor ted the highes t level s of st ress a nd bur n out tha n any p ro- fessi o nal gr o up ([2] [5] [26] [27]). A possible explanation for the rather low levels of stress and burn out expressed by EFL teachers in this re- search may be found in their students. One of the powerful demotivating factors for teachers was students’ lack of motivation or lack of interest in the subjec t. Most of the Iranian students who go to language instit utions like learning English, because the methods of teaching English in language institutions is different from schools. Like pervious researches (such as [5]), EFL teachers reported that students’ discipline problems and attitudes pro b le ms sign i ficantly red uced their o wn mot iva t io n and e nt hu sia s m for te ac hi ng and ha d an i mpa ct on t he q ua l- ity of their teach ing. One i mporta nt po int in th is re searc h was t hat in spite of te achers’ positive at titudes to wards their intrinsic as- pects of their work, many teachers regretted to have chosen teaching. This result went against previous re- searches that most of the teachers had no regret for entering the teaching profession (s uc h a s [5]). Some teachers felt sorry about enterin g teaching profes sion, althoug h they felt satisfied or stro ngly satisfied with their salar y. I t seemed that it wasn’t related to salary. Two other important issues were salary and position in the language institution. Most of teachers who were satisfied with their salary had important position in the language institutions. It seemed that there was a direct relationship between salary and position. This result was in line with [27], they stated that those teachers who hold different promotion positions were found to differ on some measures of satisfaction. In sum, teacher motivation and job satisfaction of EFL teachers was good. They had high efficacy and co m- mitment, they didn’t experience much stress and they were relatively satisfied with the language institution based factors. Acknowledgements I greatly appreciate the teachers who participated in this study. They provided me with so much precious data and perhaps contributed the most to this research. References [1] Ololube, N.P. (2006) Teachers Job Satisfaction and Motivation for School Effectiveness: An Assessment. ERIC Num- ber: ED496539, 19 p. [2] Morgan, M., Kitching, K. and O’Leary, M. (2007) The P sychic R ewards of Teaching: Examining Global, National and Local Influences on Teacher Motivation. AERA Annual Meeting, Chicago, April 2007, 19 p. [3] Darmody, M. and Smyth , E. (2010) Job Satisfaction and Occupational Stress among Primary School Teachers and School Pri ncipal s in Ireland. E S RI/The Teaching Council, Dublin, [4] Bernaus, M., Wilson, A. and Gardner , R.C. (2009) Teachers’ Motivation, Classroom Strategy Use, Students’ Motiva- tion and Second Language Achievement. Porta Linguarum, 12, 25-36. [5] Karavas, E. (2010) How Satisfied Are Greek EFL Teachers with Their Work? Investigating the Motivation and Job Sa- tisfaction Levels of Greek EFL Teachers. Porta Linguarum, 14, 59-78. [6] Gardner, R.C. (2007) Motiva tion a nd Second Lan guage Acquisi tion. Porta Li n guarum , 8, 9-20. [7] Jesus, S.N. and Lens, W. (2005) An Integrated Model for the Study of Teacher Motivation. Applied Psychology: An Inter natio nal R e v ie w , 54, 119-134. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2005.00199.x [8] Evans, L. (1998) Teacher Morale, Job Sa ti s fac t ion and Motiv a t ion. [9] Khan, T. (2005 ) Teacher Job Satisfaction and Incentives: A Case Study of Pakistan: DFID, London. http://books.google.com [10] Koustelios, A. , Kouli, O. and Theodorakis, N. (2003) Job Security and Job Satisfaction among Greek Fitness Instru c- tors. Perceptual Motor Skills, 97, 192-194. http://dx.doi.org/10.2466/pms.2003.97.1.192 [11] Scott, C., Stone, B. and Dinh am, S. (2001) I Love Teaching but…. International Patterns of Teacher Discontent. Edu- cation Policy Analysi s Archives, 9, 1-7. [12] E van s, L. (20 01 ) Delving Deeper into Morale, Job Satisfaction and Motivation among Education Professionals. Educa- tional Management Administration & Leadership, 29, 291-306. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0263211X010293004 [13] Zembylas, M. and Papanastasiou, E. (2004) Job Satisfaction among School Teachers in Cyprus. Jour nal of E ducational Administration, 42, 357-374. http://dx.doi.o r g/10.1108/09578230410534676  N. Noori et al. OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100843 12 October 2014 | Volume 1 | [14] National Center for Education Statistics (1997) Job Satisfaction among America’s Teachers: Effects of Workplace Condi tions, Background Characteristics, and Teach er Compensation. Office of Edu cational R esearch and Improvement, US Department of Education, Washington DC. [15] Brown, H.D. (2007) Princi pl es of Language Learn ing and Teaching. Pearson Education, New York. [16] P ereto mode, V.F. (1991) Educational Administration: Applied Concepts and Theoretical Perspective. Joja Educational Research and Publishers, Lagos. [17] Dinham, S. and Scott, C. (1998) A Three Domain Mod el of Teacher and S chool E xecut ive Career Sat isfact io n. Journal of Educational Administration, 36, 362-378. [18] Day, C., Stobart, G., Sammon, P. and Kington, A. (2006) Variations in the Work and Lives of Teach ers: Relative and Relational Effectiven es s. Teachers and Teachi ng: Theory and Practice, 12, 169-192. [19] V an Houtte, M. (2006) Tracking and Teacher S atisfa ctio n : Role o f Stud y Cultu re an d Trust . The Journal of Education- al Research, 99, 247-256. http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOER.99.4.247-256 [20] Scott, C. and Dinham, S. (2003) The Developmen t of Scales to Measure Teacher and School Executive Occup ational Satisfaction. Journal of E ducational Adm i ni s tr at ion, 41, 74-86. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09578230310457448 [21] K yriacou, C. and Coulthard, M. (2000) Undergr aduates’ V iews of Teachin g as a Career Ch oice. Journal of Education for Teaching, 26, 117-126. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02607470050127036 [22] Papanastasiou, E.C. and Zembylas, M. (2005) Job Satisfaction Variance among Public and Private Kindergarten School Teachers in Cyprus. I nte r nat ional Journ al of Educati o nal Re s e ar c h, 43, 147-167. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2006.06.009 [23] Woods, A.M. and Weasmer, J. (2004) Teacher Per s istence; Job Satisfaction; Mentors; Leadership; Collegiality. Educa- tion, 123, 681-688. [24] Ostroff, C., Kinicki, A. and Clark, M. (2002) Substantive and Operational Issues of Response Bias across Levels of Analysis: An Example of Climate-Satisfaction Relationships. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 355-368. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.2.355 [25] Cr ossman, A. and Harris, P. (2006) Job Sati sfaction of Seco ndary Sch ool Teachers. Educational Management Admin- istr ati o n and Leader s hip, 34, 29-46. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1741143206059538 [26] Miller, G.V. and Travers, C.J. (2005) Ethnicity and the Experience of Work: Job Stress and Satisfaction of Minority Ethnic Teachers in th e UK . International Review of Psychiatry, 17, 317-327. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09540260500238470 [27] Scott, C., Cox, S. and Dinham, S.K. (1999) The Occupational Motivation, Satisfaction and Health of English School Teachers. Educatio nal P s y c hology , 19, 287-308. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0144341990190304 N. Noori et al. OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100843 13 October 2014 | Volume 1 | Appendix A Teacher Job Satisfaction Questionnaire Background Information A. A ge 22 - 30 31 - 40 41 - 50 50+ B. Gender Male Female C. Total number of years service in teaching 1 - 5 years 6 - 10 years 11 - 15 years 16 years or more D. Where did you teach in the past? Please tick more than once if necessary. Please write number of years service. Public schoo ls Private schoo ls Language Institutions Universities Where do you currently teach? Please tick more than once if necessary. Please write of years service Public schoo ls Private schoo ls Language Institutions Universities 1. In which fields did you study? 1. English literature 2 . English translation 3. English teaching 4 . O ther field s 1. What is your level o f ed ucation? 1. Lower than BA/BSc 2 . BA/BS c 3. MA/MSc 4. PhD Please tick your degree of satisfaction with each of the statements below. How satisfying do you find: 1. H ighly satisfying 2. Satisfying 3. Neither satisf ying nor dissatisfying 4. Dissatisfying 1. The amount of recognition you receive for your efforts from people in your Language inst itution. 2. The amount of recognition you receive for your efforts from your employer /lan guage i nstit utio n gover ning body. 3.The amount of recognition you receive for your efforts from parents and your community. 4. The amount of recognition you receive for your efforts from your students. 5. Your status as an EFL teacher in society. 6. Your status a s a n EFL teacher in your language instit ution. 7. The image of EFL teachers as portrayed in the media. 8. The way that educational professional associations work for the betterment of your profession. 9. The way that go vernments wo rk fo r the bet te r me nt of yo ur stat us . 10. The range of professional in-services courses/programs/support offered to EFL teachers 11. Your salary. 12. Your opportunities for promotion or advancement 13. The p hysical working en vironment of your language i nstitution (infrastructure, re s ources etc.). 14. Yo ur benefits (holidays, e ducational leaves etc.) . 15. Your official working hours (in terms of quantity). Appendix B Teacher Motivation Questionnaire Below is a series of statements relating to factors which have been found to affect teacher motivation. Please read each statement and tick your degree of a greement or disagreement with each one. 1. S t rongly agre e 2. Agree 3. Don’t know 4. Disagree 1. Language i nstitution ad ministration d oes not supp ort my effort s to try out ne w ideas/pr actices with my stu- dents . 2. If I had to do it again, I would still choose to become a teacher. N. Noori et al. OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100843 14 October 2014 | Volume 1 | 3. Cooperat ion with co llea gues in my language institution is rewarding and beneficial. 4. I feel that working closely with young people is the most fascinating aspect of my work. 5. I feel emotionally drained from my work. 6. Extra-curricular activities (language institution proj ects, organizing language institution events etc.) are as stimulating to me as teaching is. 7. I cannot see myself continuing to teach for the rest of my career. 8. Administra tive meetings in la ng uage institution ar e no t helpful in solving teachers’ pro blems. 9. I feel total c ommitment to teac hin g. 10. Teaching increases my self-esteem. 11. I feel my workload (teaching and administrative work) is too heavy. 12. Students ’ discipline problems affect my motivation and enthusiasm for teachi ng. 13. I have dealt effectively with the problems of my students. 14. Teaching often stresses me. 15. I have posi tively i nfluenced stude nts’ lives t hrough my teaching. 16. I have felt burned out from my work. 17. My students’ low motivation levels for learning English create great stress to me. 18. My language institution provides a collegial supportive environment for me to work in. 19. I find my work mentally stimulating. 20. Students’ attitude pro blems (misbehavior in class, lack of interest i n the subject etc.) have an effect on the quality of my teaching.

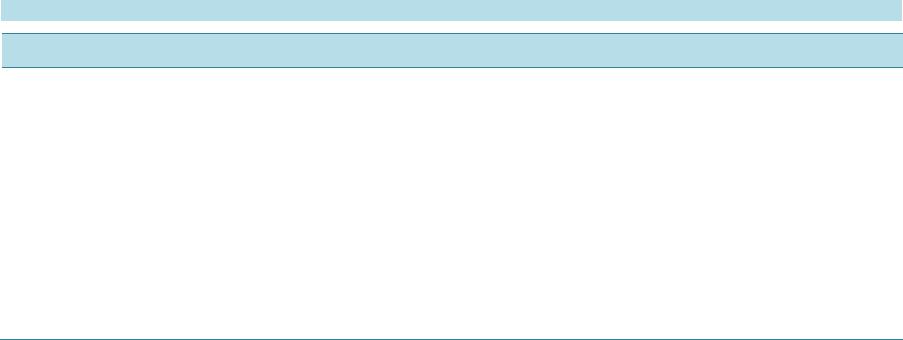

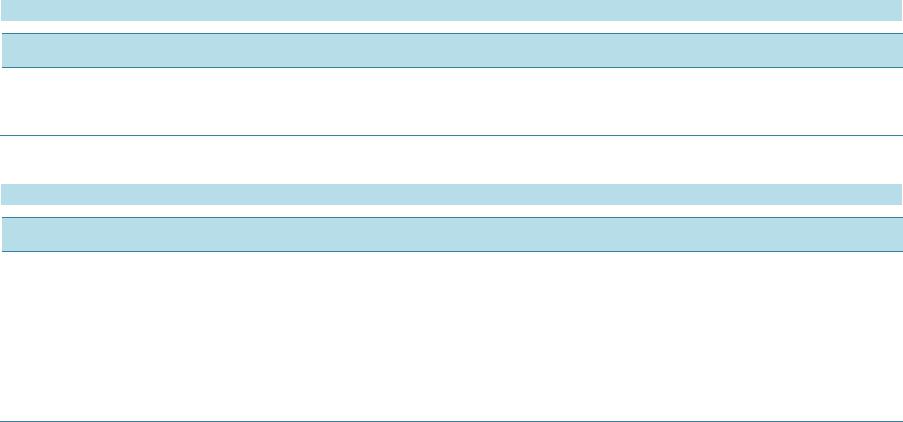

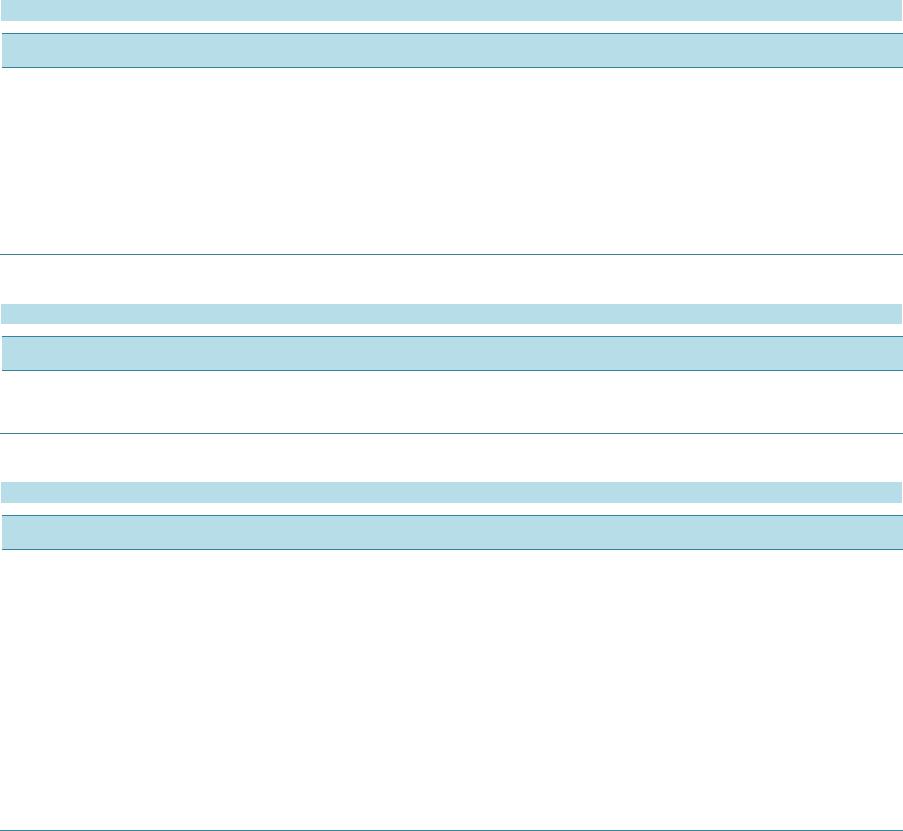

|