Open Access Library Journal How to cite this paper: Midega, M. (2014) Official Language Choice in Ethiopia: Means of Inclusion or Exclusion? Open Access Library Journal, 1: e932. http://dx. doi.org/10.4236/ oalib.1100932 Official Language Choice in Ethiopia: Means of Inclusion or Exclusion? Milkessa Midega Dire Dawa University, Dire Dawa, Ethiopia Email: milkessam@gmail.c om Received 31 July 2014; revised 19 September 2014; accepted 22 October 2014 Copyright © 2014 by author and OALib. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommo ns.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract Official language choice in a multilingual polity is a challenging phenomenon. One of such polities, Ethiopia, took “historical accident” justifications for grant to select its official language which un- equivocally disregards its own linguistic diversities. Amharic language has been arbitrarily desig- nated as the sole official language of Ethiopia since the making of modern Ethiopia. This piece uses government documents and other literature to examine Ethiopia’s official language choice and its consequences. Overall, the findings show that the knowledge of Amharic language remained de- terminant in order to access federal government institutions thereby serving as a means of exclu- sion of non-official language speakers, such as Oromo, the largest ethnic group in the country. This work thus suggests rethinking official language of Ethiopia. Keywords Afaan Oromoo, Amharic, Federal Government, Official Language Subject Areas: Linguistics, Politics 1. Introduction Ethiopia is a divided polity home to div erse groups; particularly its eth no-linguistic diversity has significant in- fluence on the country’s political, economic, social and cultural systems [1]. Currently, the number of languages spoken in Ethiopia is estimated to more than eighty, where the choice of official language at the federal level will exactly pose a challenge. Ethiopia’s Federal Constitution [2] selects only Amharic as federal official lan- guage and maintains its dominant status throughout federal jurisdictions. The major achievement of the contemporary federal constitution, as compared to previous con stitution s, is the inclusion of the provision that bestows opportunity to Members of the Federation to determine their respective official languages [2]. In spite of this success, the framers of the constitution seem to have neglected the factual numerical status of the other competing languages particularly Afaan Oromoo in the choice of federal official M. Midega DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100932 2 October 2014 | Volume 1 | language. The very preservation of monolingual government for multilingual state hosting diverse nationalities suggests discrimination. With regard to the selection of Amharic, the conventional view of the formulators of the constitution and its current sympathizers has been that “Amharic has become the most widely spoken lan- guage due to historical accident” [3]. Often it is also suggested that economic rationa le (i. e. cost of adopting two or more languages) justifies the ch oice. Can th ese one-sided views be convincing reasons where there have been civil wars for decades largely due to ethno-linguistic domination and exclusion? This piece has threefold pur- poses: 1) to briefly discuss general guiding principles that multilingual countries make use of in their choice of official language(s); 2) to examine factors that Ethiopia used for the choice of federal official language; and 3) to unearth how much language choice is a causal for ex(in)clusion in public institutions . 2. Guiding Principles of Official Language Choice in Multilingual Countries An introductory interrogation would be that if a state has to choose one or few language(s) for the official busi- ness es in a reas onab le, balanced and democratic way, wh at factors, principles, rules and guidelines are expected to be considered. Francesco Capotorti [4] explains that “a just equilibrium must be found between these con- flicting requirements in order to safeguard the fundamental rights of the persons belonging to the various lin- guistic groups as well as the interests of the nation as a whole”. Despite the fact that in a world with thousands of languages the choice of official language(s) is primarily a political decision [5], Capotorti identifies certain principles which multilingual polities have used as a guideline for the choice of official languages and according to him, those factors that need to be considered are: The numerical importance of the respective linguistic communities, their political and economic position within the country concerned, the existence at the frontiers of the country concerned of a powerful state in which the main language is one which is spoken by a minority group of that country and also… th e state of the devel- opment of the language as an effective means of wide communication in all fields [4]. Pool [5] adds “the inevitable compromise between efficiency and fairness” as the other principle. Thus, if there are two or more competing languages for the status of official language of a given jurisdiction, language policy makers of that polity need to consider the numerical size, political and economic position, languages spoken in neighboring states, eff iciency and fairness, and the development of languages of ethnic groups. Apart from “numerical, political and economic power of the speakers of the main competing languages” [6], certain languages may be chosen if it tends to “enhance external trade, strengthen geopolitical links or encourage conti- nental integration” [7]. It would be imperative to briefly touch these guiding factors to select official languages in multilingual countries. The first significant guiding factor that needs to be considered in the choice of official languages is the thre e main human rights general principles: the right to freedom of expression, the right to non-discrimination, and the right of individuals belonging to linguistic minorities. The right to freedom of expression has a linguistic aspect in any decision which establishes that the right to express opinion freely implies the right to do so in the lan- guage of one’s own choice. Certain groups may be limited from the appropriate information if, for example, there is no ne wspapers published in their languages. Fernand de Varennes argues that: There does seem to be a trend towards recognition that language is an integral part of the freedom of expres- sion, though many countries have not dealt with the issue directly. In Switzerland, for example, the Tribunal Federal indicated that language is a necessary condition to the exercise of all the fundamental rights connected with freedom of expression in written or verbal form [8]. The other principle that countries need to take into account in their language choice is the right to non-d is- crimination which is interrelated to third principle, the right of linguistic minorities. The right to non-discrimi- nation is founded mainly on fundamental right to equality of treatment at the hands of the state. Much legislation agrees the right to non-discrimination to be the most effective guarantee for the rights of any linguistic groups. Ther e are several in ternational instruments dealing with the issue of linguistic rights requirin g states to consider while selecting their respective official languages. One of such documents is the UN Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious or Linguistic Minorities, 1992. Article 2 (1) of the Decla- ration provides these persons with: “the right to enjoy their own culture, to profess and practice their own reli- gion, and to use their own language, in private and in public, fr eely and without interference of any form of dis- crimination” [9]. The second factor, the sliding scale approach, is another most popular criterion that states are considering in M. Midega DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100932 3 October 2014 | Volume 1 | their official language choice. It means that the numerical size of the speakers of a language in proportion to the whole population of a country is the most important factor in the choice of official language. Particularly, in multiethnic polities where there are several languages with varying sizes of speakers, states are expected to take into account the numerical sizes of the speakers in order to address language questions. One of the prominent legal documents providing comprehensive sliding scale approach is the European Charter for Regional or Mi- nority Language s, 1992 [10]. The third factor in th e choice of official languag e indicates economic and political position of th e speakers of a given language. Cohen [11] maintains that the selected language as the official language will actually be that of potentially and practically “a pow erful group within the state, often the lang uage of the most populous group which is also likely to be politically dominant”. According to Pool [5], persons whose native languages are not the official language(s) adopt the official one for use in communicating with the government institutions. Pool computes that: “the cost of adopting an official language might consist of time, effort, and money spent in learning the language; deprivations caused by imperfect command of the language; and the loss of prestige aris- ing from the denial of official status to one’s native language” [5]. He thus tries to resolve official language problems mathematically and correctly argues for the language of numerically and economically largest groups to be the official language because economically “the cost is proportional to the volume of those utterance and hence to the group’s size, and also proportional to the number of times they are translated” [5]. It is also argued that the choice of official languages involves an inevitable compromise between efficiency and fairness principles, which becomes the other influencing factor. Pool, for instance, tries to reconcile effi- ciency and fairness ideas in language policy through his complex mathematical model. One of his mathematical outcomes affirms that: Efficiency would require officializing the largest native language and also any other language natively spo- ken by more than 20% of the population… The three terms imply that the tax would 1) vary directly with the number of officia l languages, 2) vary inversely with the fraction of the population not natively speaking an offi- cial language, and 3) exactly compensate those who must learn an official language [5]. The last factor this article tries to touch is the principle of linguistic neutrality of the state. The notion of the neutrality of the state is usually suppos ed to mean that the state does not favor any particular indigenous gr oup at the expense of others. If there are two or more languages competing for the same status, according to Phillipson [12] “a neutral language—that is not associated w ith a particular power”, is better preferred as official language over the others. Therefore, one way to settle language competition for the same status, according to him, is the post-colonial scenario in which a foreign colonial language (typically English or French) is selected as official language on grounds of state neutrality in a multilingual multiethnic context. To sum up, there are several guiding principles that need to be considered and indeed are being used in many multilingual countries in th e selection of official language, of which one is the three main human rights general principles including the right to freedom of expression, the right to non-discrimina tion, and the right of individ- uals belonging to minority. The other commonly applied guiding principles are the sliding scale formula (nu- merical size of ling uistic groups), economic and political contributions of the groups, compromise between effi- ciency and fairness, and neutralizing the state from indigenous languages. These are highly interrelated prin- ciples. Applying one or more of these principles, for instance, Canada has adopted two federal official languages, Switzerland (three), Belgium (three), South Africa (eleven), India (two), Nigeria (one foreign language), and Cameron (opts for two foreign languages). 3. Ethiopia: Official Language Choice and Access to Federal Government The modern multiling ual state of Ethiopia was created by wars of conques t which has resulted in manifold eth- no-national problems that were and are shaping and reshaping the successive generations, creating a link be- tween past, present and future. More precisely, the Ethiopian empire state was cr eated in the second half of the nineteenth century, mainly through the use of force. The subsequent evolution of the Ethiopian polity proved na- tional domination and consequently, the independence of various ethnic groups was forcefully taken away. The vanquished ethno-linguistic groups were subjected to politico-economic domination and exploitation; and the cultures and languages of the indigenous peoples were suppressed and the dominating ethnic group’s culture and language was imposed on the c on quered pe oples [13]. From the 1960s onwards, various forms of national resistance by the subject people started to shake the rotten M. Midega DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100932 4 October 2014 | Volume 1 | empire state of Ethiopia. The 1974 revolution ended the county’s feudo-assimilation ist regime but unable to re- solve the “nationalities question” (language being at the center of it) because the revolu tion as well as its prom- ises was stolen by the military junta [5]. Since the demise of the military regime in May 1991, there has been an attempt to democratize Ethiopia’s multiethnic state and society with an ethno-linguistic federal arrangement and a multi-party democracy. There are some visible efforts to reorganize the Ethiopian state and society as parts of democratization particularly in view of language questions. Since then, Ethiopia is a multilingual country with monovoca l federal governme nt . Ethiopia hosts over eighty languages. However, simply citing the raw figure can create confusion and thus, it is necessary to realize that the majority of the languages have only very small number of speakers. Conversely, the most widely spoken languages are Afaan Or omo, Amharic, Somali , Tigrigna, Sida ma, Wolaita, Gurag e, Afar, Hadiya, and Gamo. Two of these languages, Afaan Oromo and Amharic, ar e also widely spoken as second lan- guages by members of several minority ethnic groups [14]. To say little about the Oromo language, referred to as Afaan Oromoo by its speakers and in this study, being the biggest mother tongue in Ethiopia, is the third largest indigenous language in Africa after Hausa in Nigeria and Kiswahili in eastern Africa [14]. It is also the third largest Afro -Asiatic language in the world after Arabic and Hausa [15]. Afaan Oromoo is classified as one of the Cushitic (Kushitic) cross -border languages and is spoken in Ethiopia, Soma li a , Sudan, Tanzania and Kenya [16]. In Ethiopia the language is spoken in various several places except in some northern parts. There- fore, in addition to its native speakers, Afaan Oromoo is used by members of several ethnic groups who are in contact with the Oromo such as the Harari, So mal i, S id a ma, Kaficho, Burji, Bambassi, Gedi o, Berta, Ko mo , Kulo , Anuak , Gurage and Amhara settlers in Oromia as means of communication and trade with their neighbor s [17]. This is due to the fact that in Ethiopia the Oromo are settled in an area extending from Tigray in the north to the border with Kenya in the south, and from the western tip to the eastern part, with Addis Ababa at the in- tersection of the two axes [18]. In spite of its significance as a leading mother tongue in Ethiopia, Afaan Oromoo has been one of the prohi- bited languages in Ethiopia; and remains excluded at the federal level. Amharic, the second largest mother ton- gue in Ethiopia, has come to dominate the linguistic profile of the state ever since the formation of modern Ethiopia [11] and non-Amharic languages remain disadvantageous. Until 1991, Amharic was the only Ethiopian language employed in an official capacity all-over the country. Even though the language policy of the current regime has allowed certain levels of regional linguistic freedom, it h as retained Amharic as the sole federal offi- cial language of Ethiopia. 3.1. The Ethno-Linguistic Setting and the Choice of Federal Official Languag e When it comes to numerical sizes and distributions of ethno-linguistic groups in the country, according to the national census [19], the population of Ethiopia was 53,132,296; of which 32.1% was Or omo, 30.1% was Am- hara, 6.2% was Tigrayan, 5.9% was Somali and other nationalities. Although ethnically the Oromo constitute the largest ethnic group in Ethiopia, for reasons such as assimilation policies, the number of Afaan Oromoo speakers [as mother tongue] was 31.6% of Ethiopian population, preceded by Amharic with its corresponding percentage to be 32.7% [19]. The two languages were contending languages for similar status though Afaan Oromoo was deliberately disregarded during the endorsement of federal official language on the current consti- tution. With the other census [20], the population of Ethiopia increased to 73,750,932; of which Oromo are 34.5% followed by Amhara (26.9%), Somali (6.2%), Tigrayan (6.1%) and Sidama (4.0%) constituting the top five largest ethnic groups in the country. By this census the numerical size of speakers of Afaan Oromoo has reached 33.8% of the total population of Ethiopia followed by Amharic (29.3%), Somali (6.2%), Tigre (5.9%), and oth- ers [20]. The following data (Table 1 and Table 2) provide clear picture of distribution of ethnic groups in Ethiopia and the languages they speak. The two major ethno-linguistic groups in Ethiopia are Oromo and Amhara, constituting about 2/3 of the na- tion. This literally implies the r elationships between the two adversely affect th e politics of the countr y. Accord- ing to the figures of the 1994 and 2007 censuses, Afaan Oromoo was the mother tongue of 31.58% and 33.8% of Ethiopian populatio n respectively, while Amharic was the mother tongue of 32.7% an d 29.3% respectively and other languages are less than 6% each by the two censuses. It is therefore not as such intricate to understand what made Amharic the official language of the federal government and consequently to be taught allover Ethi- opia as second language; thereby confining Afaan Oromoo mainly to Oromia Region. Such official language  M. Midega DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100932 5 October 2014 | Volume 1 | Table 1. Distribution of ethnic groups with one million or more persons in Ethiopia. Ethnic group 1994 2007 Population Population Nu mbe r % Nu mbe r % Oro mo 17,080,318 32.1 25,363,756 34.5 Amh ara 16,007,933 30.1 19,878,199 26.9 Somali 3,160,540 5.9 4,586,876 6.2 Tigrayan 3,284,568 6.2 4,486,513 6.1 Sidama 1,842,314 3.5 2,951,889 4.0 Gurage 2,290,274 4.3 1.859,831* 2.5 Wolaita 1,269,216 2.4 1,676,128 2.3 Afar 979,367 1.8 1,276,867 1.7 Hadiya 927,933 1.7 1,269,382 1.7 Gamo 719,847 1.4 1,104,360 1.5 The rests 5,569,986 10.5 9,297,131 12.6 Total 53,132,296 100 73,750,932 100 Source: [19] [20]. *Note: the Gurage population does not include the Silte ethnic group in the 2007 census. Table 2. Distribution of major mother tongues in Ethiopia. Mother tongue languages 1994 2007 Population Population Nu mbe r % Nu mb er % Afaan Oromoo 16,777,976 31.58 24,930,424 33.8 Amharic 17,372,913 32.70 21,634,396 29.3 Somali 3,187,053 6.00 4,609,274 6.2 Tigrigna 3,224,875 6.07 4,324,933 5.9 Sidama 1,876,329 3.53 2,981,471 4.0 Wolaita 1,231,673 2.32 - - Guragigna 1,881,574 3.54 1,481,836 2.0 Afar 965,462 1.82 1,281,284 1.7 Hadiya 923,958 1.74 1,253,894 1.7 Gamo 690,069 1.30 1,070,626 1.5 The rests 8,222,064 15.5 10,182,794 13.8 Total 53,132,296 100 73,750,932 100 Source: [19] [20]. imposition would never be reasonable if the government is meant to serve the peoples of the country. By the 1994 national census, during which year federal constitution was endorsed, the population size who spoke Amharic, the language which has been sponsored by the state for centuries, as second language was 9.61% of Ethiopian population, while the corresponding number for Afaan Oromoo, which has been suppressed from public institutions ever since the formation of modern Ethiopia, was 2.89 %. However, by the 2007 census, the number of Amharic speakers as second language has sharply declined while that of Afaan Oromoo rose. Thus, Jonathan Pool is correct to conclude that “in a world with thousands of languages, the choice of official lan- guage is a natural p olitics” [5]. The selection of Amharic thus was the continuity of the unfair monolingual poli- cies of previous regimes of Ethiopia. The other thing which attracts attention is the discrepancies between the numerical size of national groups and M. Midega DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100932 6 October 2014 | Volume 1 | their corresponding mother tongue languages particularly of Oromo and Amhara. This is clearly shown in Table 1 and Table 2, which explain both continuity and change of policies and practices of linguistic homogenization against various Ethiopian national groups in general and the Oromo in particular. Let us compare the numerical sizes of the two largest national groups, Oromo and Amhara, with their corresponding languages. In 1994, for example, the numerical size of Oromo constituted 32.1% of Ethiopian population and the corresponding people who spoke Afaan Oromoo was 31.58%; and Amhara formed 30.1% of the total population with the correspond- ing 32.70% Amharic speakers. In 2007, the size of the Oromo grown to 34.5% of the total population with 33.8% Afaan Oromoo speakers; and the number of Amhara national group dropped to 26.9% with Amharic speakers 29.3%. While Afaan Oromoo rises from 31.58% to 33.8%, Amharic declines from 32.70% to 29.3%; witnessing the demise of Amharic assimilation projects which could arguably be one of the optimistic outcomes of the current multinationa l federalism with its reg ional language policies and the strengths and commitments of nationalities to their languages cannot be undermined. Mamushet [21], in lieu of All Ethiopian Unity Party, ar- gues that “in fact, most of the Oromo individuals, who are able to speak Amharic, are those who learned it dur- ing the preceding regimes, particularly Haile Sellassie”. This thus suggests that Amharic has retreated to its home region, Amhara and where it retained its hegemony such as Addis Ababa and Di re Dawa. This numerical comparison also suggests some signs of continuity. In 1994, for instance, the difference be- tween the numerical size of Oromo (32.1%) and Afaan Oromoo speakers (31.58%) was 302,342 people. These volumes of people are ethnically Oromo but do not speak Afaan Oromoo, symbolizing continuation of linguistic assimilation. By the same token , in 2007, the variation between the number of Oromo (34.5%) and Afaan Oro- moo speakers (33.8%) was 433,332 people, nearly half a million. This huge figure displays the extension of pre- vious regimes’ ethno-linguistic assimilation of Oromo. Furthermore, the difference between the number of Am- hara (30.1%) and Amharic speakers (32.70%) in 1994 was 1,364,980 populations. This enormous size of popu- lation is ethnically non-Amhara but their mother tongue is Amharic language. They do not know their ethnic languages which reveal that they are assimilated to Amharic. In 2007, the difference between the numerical size of Amhara (26.9%) and Amharic speakers (29.3%) constituted 1,756,197 people of the total population of the country. These numerical facts depict how much of non-Amhara peoples of Ethiopia are still assimilated to Amharic language which inevitably includes acculturation. The previous regimes’ ethno-cultural assimilation practice s have therefore cont inued una ba ted. Moreover, the formulators of federal Cons titution, Constituent A ssemblies, who endorsed Amharic to remain the sole language of the central government, did not pay any consideration to the linguistic profiles of the coun- try. They talked merely about the forceful expansion of Amharic at the expense of other non-Amharic languages but they did no t make any effort to questi on w he ther the impositio n of Amharic succeeded to become the mother tongue of several national groups of Ethiopia. The designers of the constitution took historical accident’s justi- fications for granted, which claims that Amharic has expanded all-over the country ever since the formation of modern Ethiopia through what they call “accidents of history” and thus solely deserves the status of federal offi- cial language [22]. With this fallacy they ignored all language choice guiding principles in multilingual coun- tries. As has been said, by the 1994 and 2007 national censuses, Ethiopian population who speak Amharic as their mother tongue was 32.7% and 29.3%; while that of Afaan Oromoo was 31.6% and 33.8% respectively. The two languages were ideal for the status of federal official language of Ethiopia though Afaan Oromoo was discriminated against in order to perpetuate the historical exclusion of Oromo from the government. 3.2. Official Language as a Means of E xclusion Al and Bo grew up learning different mother tongues. At some time later stage, Bo learns Al’s, while Al does not learn Bo’s. They can now communicate with one another. Not quite on an equal footing, of course—Al tends to have the upper hand in any argument they might have with one another and in any competition in which they might have to take part using the shared language—but nonetheless with significant benefits, both material and non-material, accruing to both… So far, therefore, so good enough —except perhaps that the cost of producing this benefit, though enjoyed by Al with greater comfort and with the bonus of some pleasing by-products, is borne entirely by Bo. Is this nothing to worry about…? [23]. This quote excavates the role of proficiency in certain shared language in day-to-day activities which includes but not limited to competition over access to government institutions of the two linguistic groups, Al and Bo. This section deals with the consequences that the choice of Amharic as the sole official language brought in  M. Midega DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100932 7 October 2014 | Volume 1 | federal governments. The Federal Constitution of Ethiopia [2] orders access to federal government through Amharic knowledge; which means denial for non-Amharic languages particularly Afaan Oromoo, the mother tongue of the largest group. Disqualification of the largest language from the status of federal official language could exactly amount systematic exclusion of the group who speak the language. This piece dares to establish that conscious choices between several competing languages have vital political, economic and social costs, par- ticularly when language skills are unevenly distributed. Language choice remains one of the political weapons at the leaders’ disposal as a means of exclusion or inclusion of linguistic groups in government. For obvious reasons, if a language is selected for official purposes from among several languages, national group who speak it as its native is advantageous over others. Accordingly, figures on table 3 demonstrate the techniques how the skill in a particular language, Amharic in this case, exactly defines entrée into the federal government. From the outset, it could be argued that, when the government of Ethiopia chose Amharic language to resolve what it perceives as communication problems, it affected “patterns of participation in power, wealth and prestige ” (to use Weinstein’s expre ssion). This discloses the real politics of language in Ethiopia where lin- guistic, political, social and economic interests have been interwoven. According to the annual government reports, by June 2003, June 2004, June 2006, June 2007, and Jun e 2008, of the permanent employees of the Federal Government, Amhara national group are 52.65%, 54.44%, 46.85%, 50.15%, 50.29%; and the Oromo nationals are 17.90%, 18.88%, 17.42%, 17.75%, 18.30% followed by Ti- grayans who constit ute 7.52%, 6.43%, 6.69%, 8.70%, 7.79% respectively (see Table 3). Thus, it appears that the largest national groups, Oromo , are systematically marginalized in the expanding bureaucracies of the Federal Government. It is at this juncture that we need to observe the determinant role of language as the main gate way to the state. It is invariably constant that across years Amhara share more than half of the federal employees, where it was expected to be shared public institutions. Suggesting the severity and intolerability of the conse- quences of language choice in the long run, Abraham remarks that: As soon as you designate one language the official/national language, you thereby give a major competitive advantage… to the native speaker of that language. You also, at th e same time and by the v ery sam e act, disen- franchise the speakers of all the others language in the nation. You eliminate or heavily constrain their access to education, to employment, to i nf ormation in general a nd to power an d prestige in m any forms [14]. As a result, the rest of the linguistic groups would be marginalized; and this is apparently against the very reason of multinatio nal federalism and power sharing principles that Ethiopia is o fficially following. L aitin [24] has also similar conclusion in that if the language of former colonial power is chosen as the official language, those groups which had greater access to the state, or which are in favor of past systems, will be in a privileged position. The selection of Amharic as a sole federal official language of Ethiopia has been benefiting those who speak it as their native language. This same language policy act also subjected particularly the Oromo to another era of exclusion from state apparatus. Table 3. Federal government permanent employees by ethnic group. Ethnic groups Employee percentage 2003 2004 2006 2007 2008 Amh ara 52.65 54.44 46.85 50.15 50.29 Oro mo 17.90 18.88 17.42 17.75 18.30 Tigrayan 7.52 6.43 6.69 8.70 7.79 Gurage 4.75 4.56 4.21 4.26 4.27 Wolaita 1.02 1.15 1.30 1.37 1.45 Sidama 0.38 0.36 0.39 0.39 0.41 Somali 0.12 0.14 0.09 0.09 0.12 Not stated 11.73 9.95 19.22 13.52 13.05 Others 3.96 4.07 3.83 3.77 4.33 To tal in No. 45,514 46,184 52,833 56,9 11 57,012 To tal in % 100 100 100 100 100 Source: [26]. M. Midega DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100932 8 October 2014 | Volume 1 | Nevertheless, Yonatan [25] tends to deny these facts when he views that: “It is not all clear how the language policy will have the effect of compromising the capacity of individuals from non-Amharic speaking groups to access the state thereby continuing their historical marginalization. In fact, the reverse seems to be true in present day Ethiopia.” As has been presented, by the 2007 national census, the Oromo constitute 34.5% of the Ethiopian population, followed by Amhara (26.9%), Somali (6.2%), Tigrayan (6.1%), Sidama (4.0%) and Gu- rage (2.5%). Had the official language choice been reasonable and justifiable, all national groups could have enjoyed fair access to the federal bureaucracies; and the Oromo in particular could have had better access than any other nationalities as they are the largest group in Ethiopia. The knowledge of Amharic language remains essential factor to get employed in the federal p ublic service institutions. The federal government employment facts and figures illustrate who enjoy more and who enjoy less access to public resources, political participations and generally policy making and enforcing powers in the country. In this regard, if we compare the percentages of Oromo and Amhara in the federal government, the latter are in- cluded in the system three times do the former mainly for the reason that the favored language is their mother tongue. Weinstein properly argues that “everywhere the official language is the property of those who use it as a mother tongue or who can learn to use it as well” [27]. It appears largely possible to argue that the speakers of the winner mother tongue-take-all government institution s . As I have argued elsewhere the language policy of Ethiopia in its federal domain therefore is completely un- sound and its employment consequence is not only unreasonable but it can be potentially stereotyping and pre- judicial [28]. These facts lay evidences for the “structural discrimination and exclusion” ensuring that certain groups such as the Oromo are permanently deprived of access to the state and thus, permanently dominated. This deprivation is mainly produced by refusal to designate Afaan Oromoo as the other official language in this jurisdiction. Brian We instein enthusiastically remarked that: “Domination is a n outcome of deprivation because if one is poor, weak, and disdained, one is dependent on others. Without power one needs direction and protec- tion; without wealth one needs financial support from others; and without prestige one believes in the natural superiority of oth ers to lead. At the basis of domination and participation are deprivation and access” which are effects of official language choice [27]. In this regard, only very few ethnic groups happen to share the Ethiopian federal cake, which precisely re- flects absence of inter-ethnic equity, justice, and public power sharing [29]. Strictly speaking, the collective power and resources were expected to be shared among national groups of Ethiopia fairly. Ideally, the Oromo would have shared greater part of the cake. Cohen [11] observes that “single language policy inevitably favors the group that speaks the chosen language as a mother tongue”. This confirms that the p articipation of the Oro- mo in the federal pub lic institutions is adversely affected by this linguistic arrangement. One of the risky politi- cal strategies in Ethiopia has been such seemingly systematic exclusion of certain groups from the state. Ac- cording to the forego ing ethnic groups and linguistic figur es in Ethiopia, Van Parijs’s assertion of “there are two linguistic communities, respectively called D(ominant) and d(minate d), with respectively N and n na tive speak- ers (N > n)” [23] does not work since Amharic native speakers, who continued to be numerically Dominant in the federal state bureaucracy, are less than Afaan Oromoo native speakers who remain dominated [remember that currently Afaan Oromoo native speakers constitute 33.8% of the total population of Ethiopia which is greater than Amharic native speakers 29.3%] in the same government. Contrary to the actual government activities uncovered in the preceding arguments, the federal constitution has mainly devoted to equalities of benefits for all national groups in Ethiopia. Accordingly, the Preamble of Ethiopian Constitution [2] promises “…to build a political community founded on the rule of law… to live to- gether on the basis of equ ality… by rectif ying historically un just relationship ... to live as one economic commu- nity…”. The practices on the ground stand out absolutely against these promises becau se historical linguistic in- justices have been perpetuated. Article 41 (3) of the constitution also declares th at “every Ethiopian national has the right to equal access to publicly funded social services”, and Article 43 of it requires that: The Peoples of Ethiopia as a whole, and each Nation, Nationality and People in Ethiopia in particular have the right to improved living standards and to sustainable development. Nationals have the right to participate in national development and, in particular, to be consulted with respect to policies and projects affecting their community… The basic aim of development activities shall be to enhance the capacity of citizens for the devel- opment and to meet their basic needs [2]. The constitution thus strictly forbids any form of exclusion particularly from policy making and publicly funded social services. Furthermore, Article 89 (1&2) guarantees that “…government has the duty to ensure that  M. Midega DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100932 9 October 2014 | Volume 1 | all Ethiopians get equal opportunity to improve their economic conditions and to promote equitable distribution of wealth among them” [2]. Participation in practical sense is not only to elect or to be elected but it means sharing in the public wealth which include, in ter alia, employment, prestige and positive symbols of the society through language. Numerous international and regional legal instruments also advocate non-discrimination on the basis of language or others by declaring that all human beings have certain inalienable political, economic, and social rights which are forms of participation. The choice of Amharic as the sole official language in the federal jurisdiction has no justifiable ground. Let us now compare ethnic group’s share of federal employees with the nationwide ethnic group’s population percentage in 2007. According to comparison Table 4, in 2007, Oromo who form 34.5% of the Ethiopian population was em- ployed by half of its percentage (17.75%); while Amhara constituting 26.9% of the total population gets em- ployed nearly twice its percentage (50.15%). The Somali ethnic group (6.2%) is employed only by 0.09%; the Tigrayan (6.1%) is employed by 8.70%; the Sidama (4.0%) is employed by 0.39%; and th e Gurage (2.5%) gets employed by 4.26%. The Oro mo, Somali and Sidama had to suffer from unfair access to the state. Do not forget that the Oromo, Somali and Sidama national groups are Cushitic language speakers; while the Amhara, Tigrayan, and Gurage are Semitic language family speaking groups. Ethiopia’s federal official language has thus assured inclusion for some ethnic groups and exclusion f or others. Data on Table 5 exhibit the speed at which ethnic groups are being employed or getting access to the state bureaucracy in the Federal Government. The Oromo in particular are subjected to discriminatory linguistic for- mula of the Federal Government. These lethal effects of official language problems in job markets, political par- ticipation and generally democratic power sharing among ethnic groups suggest the centrality of language in the age-old nationalities question of access to the state. Alan Patten and Will Kymlicka observe that “…the very process of selecting a single language can be seen as inherently exclusionary and unjust. Where political debate Table 4. Comparison of population with employees, 2007 for six major ethnic groups. Ethnic group Country population percentage by 2007 Federal government empl oyees percentage by 2007 Oro mo 34.5 17.75 Amh ara 26.9 50.15 Somali 6.2 0.09 Tigrayan 6.1 8.70 Sidama 4.0 0.39 Gurage 2.5 4.26 Source: [20] [26]. Table 5. Permanent employees hired in 2008 in the federal government. Hired employees in 2008 Ethnic group Nu mb er % Amh ara 1514 45.8 Oro mo 670 20.3 Tigrayan 244 7.4 Gurage 169 5.1 Somali 8 0.2 Sidama 17 0.5 Wolaita 68 2.1 Gamo 70 2.1 Not stated 425 12.9 Others 122 3.7 Total 3307 100 Source: [26]. M. Midega DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100932 10 October 2014 | Volume 1 | is conducted in the language of the majority, linguistic minorities are at a disadvantage, and must either invest the time and effort needed to shift as best they can to the dominant language or accept political margina lization” [30]. My personal interview with Adebabay [31] shows that: It is unquestionable that knowledge of the official language is the dominant way to the state’s employment opportunities. No matter how we master the required profession and knowledge from the universities, official language incompetence limits us from communicating it out when necessary. The processes and procedures of recruiting employees for th e federal institution s, as we know, are conducted in Amharic language except for li- mited offices. Specifically, written exams and interviews are carried out in the medium of Amharic. This appar- ently prevents those graduates and others who are unable to explain their knowledge in Amharic from access to public offices. Moreover, he remarks how much the knowledge of Amharic remained significant to access federal public of- fices in Ethiopia: Even if they [non-Amharic speakers] get the likelihood of recruitment for some positions, they face Amharic language difficulty on-the-job as we have experienced in the last few years. In this regard, Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa administrations are no exception. The fundamental trouble will be that if the principle of fair em- ployment of ethnic groups in the federal institutions is disregarded, those underrepresented ethnic groups feel excluded from the government which is politically dang erous state of affairs that veers in the conflict directions [31]. Thus, Adebabay has never hidden the future political dangers of currently excluding certain ethnic groups from the state on the basis of such flawed official language choice. Likewise, Mamushet [21] argues that Oromo graduates can only be employed within Oromia Region for the reason of language; and also it is hardly possible to find offices paying better salaries as compared to salaries at the Federal level. They are losers at both national and regional levels [21]. Moreover, Yared [32] maintains that “focusing on their own languages, as important as it is to maintain a distinc t identity, might lock non-Amharic linguistic groups up in regional politics and matters since Amharic is the language of the federal government and business in Addis Ababa where the bulk of the government’s currency circulates”. The exclusion of some nationalities from federal government is not caused by focusing on o ne’s own language, but by the official language problem. The government policy that does not address the principles of equitable participation of ethnic groups in power and resource sharing tends to sponsor conflicts. McGarry, O’Leary and Simeon have famously stated that “a state that serves the interests of one (or so me) nationality, religion, ethnicity or language will promote the counter mobilization of the excluded com- munities, and hence conflict” [33]. Let me summarize this article with Merera’s [34] concern which argues that learning in Afaan Oromoo or English and competing for jobs in another language is not only denying opportunities but it amounts to a crime for people are made to compete in an area where they are completely deficient. He puts that “there is no equal competition. Non-Amharic speakers, particularly the Oromo are competing with those who were born in Am- har ic speakers , grown up speaking Amharic and learnt in Amharic. There is no equal level playing field for the Oromo. Thus… no argument; it is clear disadvantage to the Oromo and other non-Amharic speakers” [34]. In general, this article has argued that designation of Amharic as the sole federal official language has benefited some in ensuring their better access to the state and cost others serving as a means of their exclusion and marg i- nalization. 4. Concluding Remarks The foregoing discussion suggests that the choice of official language in federal Ethiopia is surrounded by poli- tics of exclusion. This is apparent, especially, when the status of Afaan Oromoo at the federal level comes to the picture. The designation of Amharic as the sole official language of the federal government has resulted in the continuation of age-old marginalization of non-Amharic speakers in general and Oromo in particular in the state bureaucracy. Despite the fact that the Oromia regional policies encourage the development of Afaan Oromoo at the regional level, Oromo remains subjected to discriminatory linguistic formula of the central government of Ethiopia. The post-1991 government has retained Amharic linguistic status quo to determine who would have to have access to institutions of the federal government through its single language-language policy. This in turn has led  M. Midega DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100932 11 October 2014 | Volume 1 | non-Amharic speakers, especially the Oromo, the largest national group in Ethiopia, to continue suffering from domination and marginalization in the federal government. First, the federal official language choice was f lawed for its disregard of Afaan Oromoo, the leading mother tongue in Ethiopia. No general guiding principle of offi- cial language choice in multilingual countries was considered; rather the makers of federal constitution had Ethiopia in mind as a monolingual unitary polity. The misperception that Amharic is the uniting language of Ethiopia and other languages such as Afaan Oromoo are divisive and disintegrative which remains unresolved has impact on the official language choice. Second, the results of disregarding Afaan Oromoo from federal offi- cial status have been severe for the Oromo national group. The federal official language policy of Ethiopia has lingered to serve as a means of exclusion particularly for the largest national group in the country. While the Oromo accesses the federal government by half percentage of their population size, the Amhara accesses the same government twice their population size. Put differently, the Amhara accesses the federal government of Ethiopia three times the Oromo. It shows that the Oromo is severely marginalized in th e federal gover nment insti- tutions as compared to others in general. Such domination has national policy implications for the future con- flicts. The main questions thus remain: should the existing monolingual policy of the federal government be retained? Should Afaan Oromoo continue to be unqualified from entering into the linguistic profiles of central government of Ethiopia? Isn’t there an option to address structural employment discriminations caused by flawed official language choices? These and other questions, in fact, call for radical rethinking of the choice of the current fed- eral official language through comprehensive realistic approach. National dialogue on the status of Afaan Oro- moo would be imperative so as to transform Ethiopia’s federal government to where public power and r esource sharing would be reasonably guaranteed among all national groups. Adopting Afaan Oromoo as the other feder- al official language may resolve the Ethiopia’s largest group age-old access to the state question in this regard. Two official languages are ideal for federal government of Ethiopia for the two groups, Oromo and Amhara, constituting 2/3 of the population of the country. The formation of bilingual federal government would be less costly since Oromo don’t need to learn Afaan Oromoo. Such decisions would tame Oromo nationalism and the- reby promote national consensus and unity. Exclusion of Oromo from public power, resources, and prestige will never bring peace and development to the country. Particularly the two dominant national groups have to come to consensus on matters of interpretation of Ethiopian political history. This will pave the way for other natio- nalities to have their say in the state politics. In this regard, national dialogue on the federal official language question would enable to build better understanding of language politics in Ethiopia and come up with appropri- ate and better inclusive language policy suggestions for the future federal government of multinational Ethiopia. References [1] Levine, D. (2000) Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multi-Ethnic Society. The University of Chicago Press, Chi- cago and London. [2] FDRE (1995) Constitution of Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Proclamation No. 1, Addis Ababa. [3] Aberra, D. (2009) Principles Guiding the Choice of Official Languages Is Multilingual Societies: Some Reflections on the Language Policy of Ethiopia. In: Regassa, T., Ed., Issues of Federalism in Ethiopia: Towards an Inventory, Ethio- pian Constitutional Law Series, Vol. 2, Addis Ababa University Press, Addis Ababa. [4] Capotorti, F. (1991) Study on the Rights of Persons Belonging to Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minority. UN Spe- cial Rapporteur, New York. [5] Pool, J. (1991) The Official Language Problem. The American Political Science Review, 82, 495-514. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1963171 [6] Druviate, I. (1999) Language Policy in a Changing Society: Problematic Issues in the Implementation of International Linguistic Human Rights Standard. In: Kontra, M., Phillipson, R., et al., Eds., Language: A Right and a Resource: Ap- proaching Linguistic Human Rights, Central European University Press, Budapest. [7] Phillipson, R. and Skutnabb-Kangas, T. (1995) Linguistic Rights and Wrongs. Applied Linguistics, 16, 483-504. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/applin/16.4.483 [8] De Varennes, F. (1994) Language and Freedom of Expression in International Law. Human Rights Quarterly, 16, 163- 186. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/762415 [9] General Assembly Resolution 47/135 (1992) UN Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious or Linguistic Minorities. [10] Strasbourg (1992) European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.  M. Midega DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100932 12 October 2014 | Volume 1 | http://conventions.coe.int/Treaty/en/Treaties/html/148.htm [11] Cohen, P.E.G. (2000) Identity and Opportunity: The Implications of Using Local Languages in the Primary Education System of the Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Region (SNNPR), Ethiopia. Ph.D. Dissertation, School of Oriental & Africa Studies, London University, London. [12] Phillipson, R. (1999) International Languages and International Human Rights. In: Kontra, M., Ed., Language: A R ight and a Resource: Approaching Linguistic Human Rights, Central European University Press, Budapest. [13] Gudina, M. (2003) Ethiopia: Competing Ethnic Nationalisms and the Quest for Democracy, 1960-2000. Shaker Pub- lishing, Netherlands. [14] Demewoz, A. (1990) Language, Identity and Peace in Ethiopia and the Horn. 4th International Conference on the Horn of Africa 1989, Centre for the Study of the Horn of Africa, New York, 69-75. [15] Gragg, G.B. (1982) Oromo Dictionary. Michigan State University, East Lansing . [16] Gamta, T. (1993) Qube Afaan Oromoo: Reasons for Choosing the Latin Script for Developing an Oromo Alphabet. The Journal of Oromo Studies, 1. [17] Bulcha, M. (1994) The Language Policies of Ethiopian Regimes and the History of Written Afaan Oromoo: 1844-1994. The Journal of Oromo Studies, 1. [18] Kebede, H. (2005) The Varieties of Oromo. In Ethiopian Language Research Centre. Working Papers, Vol. 1, No. 1, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa. [19] FDRE (1999) The 1994 Population and Housing Census of Ethiopia. Results at Country Level Vol. II. Analyti cal Re- port, Central Statistic Authority, Addis Ababa. [20] FDRE (2010) The 2007 Population and Housing Census of Ethiopia. Results at Country Level. Analytical Report. Central Statistical Agency, Addis Ababa. [21] Mamushet, A. (2010) Public Relations of All Ethiopian Unity Party (AEUP) Interview. Addis Ababa. [22] Ethioipa (1994) Minutes of the Ethiopian Constituent Assembly. Vol. 2, Minute No. 11, 000010-000026, Addis Ababa. [23] Van Parijs, P. (2003) Linguistic Justice. In: Kymlicka, W. an d Pat ten , A., Eds., Language and Political Theory, Oxford University Press, New York. [24] Laitin, D.D. (1977) Politics, Language, and Thought: The Somali Experience. The University of Chicago Press, Chi- cago and London. [25] Fessha, Y.T. (2009) A Tale of Two Federations: Comparing Language Rights Regimes in South Africa and Ethiopia. In: Ararssa, T.R., Ed., Issues of Federalism in Ethiopia: Towards an Inventory, Ethiopian Constitutional Law Series, Vol. 2, Addis Ababa University Press, Addis Ababa. [26] Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (2004) Personnel Statistics Report 2002. Federal Civil Service Commission, Addis Ababa. Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (2005) Personnel Statistics Report 2003. Federal Civil Service Commission, Addis Ababa. Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (2007) Personnel Statistics Report 2006. Federal Civil Service Agency, Ad- dis Ababa. Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (2008) Annual Civil Service Statistics Report 2007. Federal Civil Service Agency, Addis Ababa. Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (2009) Civil Service Human Resource Statistics Report 2008. Federal Civil Service Agency, Addis Ababa. [27] Weinstein, B. (1983) The Civic Tongue: Political Consequences of Language Choices. Longman Inc., New York and London. [28] Milkessa, M. (2011) Ethiopia’s Choice of Federal Working Language and Its Implications For non-Amharic Languag- es: The Case of Afaan Oromoo. M.A. Thesis, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa. [29] Benti, G. (2001) An Overview of Some Factors Limiting the Migration of the Oromo to Addis Ababa. The Journal of Oromo Studies, 8. [30] Patten, A. and Kymlicka, W. (2003) Introduction: Language Rights and Pilitical Theory: Context, Issues, and Ap- proaches. In: Kymlicka, W. and Patten, A., Eds., Language and Political Theory, Oxford University Press, New York. [31] Adebabay, A. (2010) Public Relations Service Head of the Federal Civil Service Agency. Interview, Addis Ababa. [32] Yared, L. (2009) Linguistic Regimes in Multinational Federations: The Ethiopian Experience in Comparative Perspec- tive. In: Ararssa, T.R., Ed., Issues of Federalism in Ethiopia: Towards an Inventory, Ethiopian Constitutional Law Se- ries, Vol. 2, Addis Ababa Unive rsity Press, Addis Ababa. [33] McGarry, J., O’Leary, B. and Simeon, R. (2008) Integration or Accommodation? The Enduring Debate in Conflict M. Midega DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100932 13 October 2014 | Volume 1 | Regulation. In: Choudhry, S., Ed., Constitutional Design for Divided Societies: Integration or Accommodation, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 41-88. [34] Gudina, M. (2010) Chai rman of the Oromo People’s Congress (OPC), and Vice Chairman and Chairman of the Orga- nizational Affairs Committee of the Ethiopian Federal Democratic Forum. Interview, Addis Ababa.

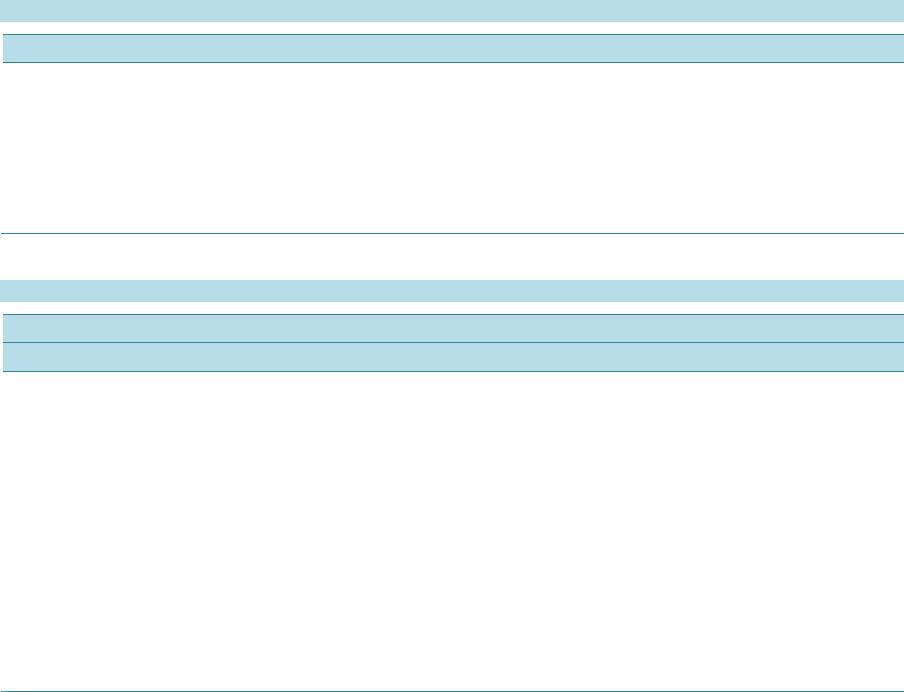

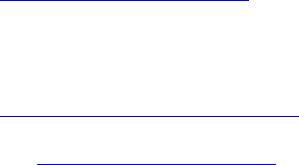

|