Open Access Library Journal How to cite this paper: Rana, K.K. and Rana, S. (2014) Microwave Reactors: A Brief Review on Its Fundamental Aspects and Applications. Open Access Library Journal, 1: e686. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/oalib.1100686 Microwave Reactors: A Brief Review on Its Fundamental Aspects and Applications Kalyan Kumar Rana1*, Suparna Rana2 1Department of Chemistry, Gushkara Mahavidyalaya, Gushkara, Burdwan, WB, India 2Department of Applied Science, Haldia Institute of Technology, Haldia, WB, India Email: *kalyankrana@yahoo.co.in, ranamandal@yahoo.co.in Received 1 July 2014; revised 2 August 2014; accepted 10 September 2014 Copyright © 2014 by authors and OALib. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativ ecommon s.org/l icens es/by/4.0/ Abstract Improved laboratory protocols for convenient and rapid transformations are highly desired in modern synthetic chemistry. Microwave irradiated reactions have received considerable attention in recent years and it is a subject of intense discussion in the scientific community. Microwave heating is more efficient in terms of the energy used, produces higher temperature homogeneity and is considerably more rapid than conventional heating methods. This technique as an alterna- tive to conventional energy sources for introduction of energy into reactions has become a recog- nized practical method in various fields of chemistry. Microwave-assisted organic synthesis (MAOS) is known for the spectacular accelerations produced in many reactions as a consequence of the increased heating rate, a phenomenon that cannot be easily reproduced by classical heating means. As a result, higher yields, milder reaction conditions and shorter reaction times can often be at- tained. Its specific heating method attracts extensive interest not only because of rapid volumetric heating, but also for suppressed side reactions, energy saving, decreased environmental pollu- tions and safe operations. In this review, we will try to represent an overview on origin and fun- damental features of microwave ovens and its usefulness in MAOS. Keywords Microwave, Dielectric Heating, Loss Angle, Monomode, Multimode, Synthesis Subject Areas: Green Chemistry, Material Exp erim ent, Organic Chemistry 1. Introduction The first chemists or alchemists as they may be called, transformed one body into another by means of, princi- pally, fire. Fortunately, fire is no w rarely used but it was not until Robert Wilhelm Eberhard Bunsen (1811-1899, *  K. K. Rana, S. Rana OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100686 2 September 2014 | Volume 1 | discoverer of caesium in 1860 and rubidium in 1861) invented the burner that the energy from this heat source could be applied to the reaction vessel in a focused manner. The Bunsen burner was later superseded by the heating mantle, oil bath or ho t plate. Recently, a new technique has come to the forefront of chemical research, microwave dielectric heating. In a similar way to the introduction of the heating mantle, this technolo gy will no doubt require a change in the chemist’s mindset. In 1986, Gedye and Giguere reported [1] for the first time t hat the organic reactions could be conducted very rapidly under microwave irradiation [1] [2]. Since then, micro- wave has been widely used in synthetic chemistry to reduce reaction time and increase product yield [3] [4]. Par- ticularly over the past few years there has been a dramatic uptake in th e us e of microw aves as an en er gy source to promote synthetic t ransformations. The production of dedicated in strumentation by the leading manufacturers has propelled what was 20 years ago a fascinating idea into a day-to-day device for synthetic chemists. Microwave- assisted organic synthesis (MAOS) is clearly a method by which a chemist can achieve target in a fraction of the time as compared to traditional conductive heating methods. Reactions times in the best cases have been reduced from days or hours to minutes. 2. Behind the Backdrops It was dur ing a rad ar-related research project in 1946 in USA, end stage period of World War-II, that Dr. Percy LeBaron Spencer (1894-1970, was orphaned, never finished grammar school and bagged more than 150 patents) ([5] a), a self-taught engineer with the Raytheon Corporation, noticed something abnormal. One day, while makin g magne trons, t hen used to generate microwave radio signals for combat radars, Sp encer was st anding in front of an active radar set and noticed the candy bar he had kept in his pocket had melted. Spencer was not the first man to note t his i ncide nt, but he was the first to examine it. He decided to test with some popcorn kernels. Along with his colleagues, Spencer watched the popcorns were cracked, popped up and splattered all over the nearby place. This way the world’s first micro waved popcorns were prepared. In continuation to his innovative trial, Spencer next took an egg, put it in a kettle and placed the magnetron above the kettle. Unfortunately, one of his curio us colleagues came very close to it and tried to look from above what was ha ppening inside the ket tle. Suddenly, as per modus operandi of microwave heating, the innocent egg exploded and splattered hot viscous liquid all o ver the colleague’s stunned face. In contrast, the face of Spencer lit up with a logical scientific idea: the melted candy bar, the popcorn and now the exploding egg were all resulting from exposure to low-density microwave energy. He thought, if an egg could be cooked quickly, why not other foodstuffs? Experimentation continued and Spencer created the first true microwave oven by joining a high density electromagnetic field ge- nerator device to an enclosed metal box. Allowing controlled and safe testing, the device emitted microwaves into the metal box without any escape. He then tried to monitor temperatures and observed effects with various foodstuffs in the box. In 1947 Raytheon produced the first commercial microwave oven which was around 6 feet tall, weighed about 750 lbs and cost between $2000 and $3000 at that ti me. The first kitchen countertop, domes- tic oven was produced in 1967 by Amana (a division of Raytheon). It was a 100-volt microwave oven, which cost just under $500 and was smaller, safer and more reliable than previous models. During 1970s there was an upsurge of microwave ovens elsewhere in the world. Up to the middle of 1980’s microwave oven or famous electronic oven was used only for defrosting frozen food and cooking. Since 1986 [1] the microwave has be- come a source of heating chemical reaction, extraction etc. So, a concise account ([5] b, c) of evolution and de- velopment of microwave ovens would be as follows: 1946―Microwave radiation was discovered as a method of heating. By late 1946, the Raytheon Company had filed a patent proposing that microwaves be used to cook food. An ove n that hea ted fo od using micro wave energy was then placed in a Boston restaurant for testing. 1947―Raytheon built the first commercially available microwave oven, “Radarange”, standing 5.5 ft tall, weighing over 750 lbs and costing about US $5000 (~$53,000 in today’s dollars) each. 1952―Raytheon licensed its technology to the Tappan Stove company of Mansfield, Ohio. 1954―Raytheon introduced the first commercial microwave oven “1161 Radarange”. 1955―Tappan introduced a large, 220 volt wall unit as a home microwave oven, cost was about US $1295 (~$11,500 in today’s do llars) each. 1965―Ray theon acquired Amana Home Appl iances , Iowa, an American brand of household appliances. 1967―Amana introduced the first popular home model, the countertop Amana Radarange, at a price of US $495 ($3500 in today’s dollars) each.  K. K. Rana, S. Rana OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100686 3 September 2014 | Volume 1 | 1978―First microwave laboratory instrument was developed by CEM (abbreviation for Chemistry, Electron- ics and Mechanics as three founders were a Chemist, an Electrical engineer and a Mechanical eng i nee r ) Corpo- ration, US A, to analyze moist ure in solids. 1983-1985—Microwave radiation was used for chemical analysis. 1986—Robert Gedye of Laurentian University, Canada, George Majetich of University of Georgia, USA and Raymond Giguere of Mercer University, USA along with their co-workers published papers relating to micro- wave radi ation in chemica l synt hesis. 1990—Milestone S.r.l., Italy, made the first high pressure MW vessel (HPV 80) for performing complete di- gestion of difficult to digest materials like oxides, oils and pharmaceutical compounds. 1992-1996—CEM Corporation developed a more effective batch system reactor (MDS 200) and a single mode cavity system (Star 2) that were suc cessfull y used for chemi cal synthesis. 1997―Milestone S.r.l. a nd Prof. H. M. K ingston of Duq uesne U niversi ty cul minated t he land mark refe rence book titled “Microwave-Enhanced Chemistry-Fundamentals, Sample Preparation, and Applications”, edited by H. M. Kingston and S. J. Haswell. 1990s—Microwave chemistry emerged and developed as a most promising field of study for its applications in chemical reactions. 2000 onwards―CEM, Bio tage, Anton Paar, Milesto ne etc. marketed a n umber o f MW reactor models o f varying capacities and temperature control that broadens the applicability and prosperity of MW as sist ed organic synthesis. 3. Microwave’s Essential Parameters Microwave heating refers to the use of electromagnetic waves of certain frequencies to generate heat in the sub- strate [6]. Microwaves lie in the region of the electromagnetic spectrum between millimeter wave and radio wave i.e., between I.R. and radio waves. These waves are sometimes defined as waves with wavelengths (Figure 1) between 0.01 m to 1 m, corresponding to the frequency of 30 GHz (or 3 × 104 MHz) to 0.3 GHz (or 3 × 102 MHz). 3.1. Basic Theory of Microwave Heating As stated, microwave irradiation is actually an electromagnetic irradiation in the frequency range of 0.3 to 300 GHz. All microwave ovens, be it do mestic type or dedicated microwave reactors for chemical synthesis, operate at a particular frequency of 2.45 GHz (which corresponds to a wavelength of 12.24 cm) to avoid interference with telecommunication and cellular phone frequencies. An important point is that the energy of a microwave photon in this frequency region (0.0016 eV) is lower than the energy of Brownian motion and is also too feeble to break chemical bonds. It is, therefore, clear that microwaves, by itself, cannot induce chemical reactions ([7] a-c). Energies of chemical bonds in comparison to different microwave energies ( Table 1) and standard frequen- cies for industrial, scientific and medical use (Table 2) are summarized. Figure 1. The electromagnetic spectrum sho wing charact er istics of microwaves.  K. K. Rana, S. Rana OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100686 4 September 2014 | Volume 1 | Table 1. Energies of chemical bondsa in comparison to different mi crowave energies . Ener gy/eV b Energy/kJ∙mol−1 1 CC single bond 3.61c347 2 CC double bond 6.35c613 3 CO single bond 3.74c361 4 CC double bond 7.71c744 5 CH bond 4.28c413 6 OH bond 4.80c463 7 hydrogen bond 0.04 - 0.44d4 - 42 8 MW 0.3 GHz 1.2 × 10−26 0.00011 9 MW 2.45 GHz 1.0 × 10−25 0.00096 ≈ 1 J∙mol−1 10 MW 30 GH z 1.2 × 10−3 0.11 aFor more examples of strengths of chemical bonds see Ref. ([7] d); b1 e V = 1.602177 × 10−19 J; cSee Ref. ([7] e); dSee Ref. ([7] f). Table 2. In accor dan ce with i nt ern ation al agree men ts all owed freq u en cies for industri- al, scientific and medical use (ISM-frequenci es). Frequen cy in MHz Wavelength in cm 433.92 ± 0.2% 69.14 915 ± 13#32.75 2450 ± 50 1 2. 24 5800 ± 75 5.17 24125 ± 125 1.36 #Not allowed in Germany. Microwave irradiated chemistry is based on the efficient heating of materials by “microwave dielectric heat- ing” effects. This phenomenon is dependent on the ability of a specific material (solvent or reagent or anything else) to absorb microwave energy and convert it into heat. The electric component [8] of an electromagnetic field causes heating by t wo main mechanis ms: dipo lar polarizatio n and ionic co nduction. Irrad iation of the sam- ple at microwave frequencies results in the dipoles or ions aligning in the applied electric field. As the applied field oscillates, the dipole or ion field attempts to realign itself with the alternating electric field and in this process, energy is lost in the form of heat energy through molecular friction and dielectric loss. The amount of heat genera ted by this process is direc tly related to the ability of the matri x to align itself with the freque ncy of the applied field. If the dipole does not have enough time to realign with the vibrating applied electromagnetic field or reorients itself too quickly with the applied field, no heating occurs. The allocated frequency of 2.45 GHz used in all commercial systems lies between these two extremes and gives the molecular dipole time to align in the field, but not to follow the alternating field, in concert with its frequency, precisely ([7] b, c). The heating characteristics of a particular material (for example, a solvent) under microwave irradiation conditions are dependent on its dielectric properties. The ability of a specific substance to convert electromagnetic energy into heat at a given frequency and temperature is determined by the so-called loss factor or loss angle or loss tangent, . T his loss fact or is e xpressed as , where is the dielectr ic loss, which i s indica- tive of the efficiency with which electromagnetic radiation is converted into heat and is the dielectric con- stant. A reaction medi um with a high value is more effective for fruitful absorption and consequently, for rapid heating. In other words, the more the value of loss factor or loss angle ( ), the more will be the diele c- tric heating of a material under microwave irradiation. The loss angles or loss factors of some common organic solvents are s ummarized in Table 3. Generall y, solve nts are clas sified as high ( ), medium ( 0.1 - 0.5) and low microwave absorbing (tanδ < 0.1).  K. K. Rana, S. Rana OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100686 5 September 2014 | Volume 1 | Table 3. Loss factors (tanδ) of different solvents [9] at 2.45 GHz and 20˚C. Solvent tan δ Solvent tanδ ethylene glycol 1.350 DMF 0.161 eth anol 0.941 1,2-dichloroetha n e 0.127 DMSO 0.825 water 0.123 2-propanol 0.799 chlorobenzene 0.101 formic acid 0.722 chloroform 0.091 methanol 0.659 acetonitrile 0.062 nitrobenzene 0.589 ethyl acetate 0.059 1-butan ol 0.571 acetone 0.054 2-butan ol 0.447 tetrahydrofuran 0.047 1,2-dichlor obenzene 0.280 dichloromethane 0.042 N-meth yl-2 -pyrrolidinone (NMP) 0.275 toluene 0.040 acetic acid 0.174 hexane 0.020 Other common solvents without a permanent dipole moment such as carbon tetrachloride, benzene and dio- xane are more or less microwave transparent. It is to be emphasized that a low value d oes no t rule o ut a particular solvent from being used in a microwave-heated reaction. Since either the substrates or some of the reagents/catalysts are likely to be polar, the overall dielectric properties of the reaction medium will in most cases allow sufficient heating by microwaves. Furthermore, polar additives such as ionic liquids, for example, can be added to otherwise low-absorbing reaction mixtures to increase the MW absorbance level of the medium. Of course, one must remember that the rate of temperature increase also depend upon the specific heat capacity, volume, emiss ivity, geometry o f the mole c ules and the strength of the applied e le c tromagnetic field . 3.2. Loss Angle The relationship between , and is purely mathematical and can be described using simple trigo- nometrical rules ([7] c). The dielectric loss ( ) and the dielectric constant ( ) of a material are two determi- nants of the efficiency of heat transfer to the sample. The magnitude of the force acting between two given elec- tric charges placed at a definite distance apart in a uniform medium is determined by a property of the medium which is known as dielectric constant. If “ ” and “ ” are the values of the two electric charges placed at a distance “ ” apart in a uniform medium, then the force “F” a ctin g bet ween the m is gi ven by C oulo mb’s law as , where e′ = dielectric constant of the medium. The larger the dielectric constant, the greater the coupling with microwaves and thus, faster the rate of heating. The quotient or the dissipation factor, with a hi gh val ue sho ws rea dy susc eptib ility to micro wave energy. In realit y, loss angle or loss factor ( ) is proportional to the polarizability and the electrical conductivity of the reaction medium which means polar and ionically conducting solvents are pr eferable for microwave-assisted reactions. 3.3. Microwave Oven: The Apparatus Monomode and multimode are the two categories into which microwave ovens are often classified [10]. Monomode or Single -mode Microwave Oven: Monomode microwave ovens are able to create a standing wave model, which is produced by the interference of fields that have the same amplitude but different oscillat- ing directions ( Figure 2). This interface generates an arrangement of nodes where microwave energy intensity is zero and a collection of antinodes where the magnitude of microwave energy is maximum. The main wave mechanical factor that determines the structural design of a single-mode apparatus is the dis- tance of the sample from the magnetron. This distance should be such that the sample vessel is placed at the an- tinodal po sitio n o f the standing electr omagnetic wave pattern (Figure 3). Among many advantages, most important advantage of single-mode apparatus is their high rate of heating. One of the drawbacks of single-mode apparatus is that, at a time, only one vessel can be irradiated.  K. K. Rana, S. Rana OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100686 6 September 2014 | Volume 1 | Multi-Mode Microwave Oven: Initial simple microwave ovens and present day household microwave ovens are of this category. Purposeful avoidance of generating a standing wave pattern inside the oven cavity is the most significant feature of a multi-mode apparatus (Figu re 4). This is done so as to generate as much chaos as possible inside the cavit y. The greater the chaos, the higher the dispersion of radiation which ultimately increases the area of effective heating. Thus, a multi-mode microwave heating apparatus can accommodate a number of samples simultaneously, unlike single-mode app aratus. O n the b asis o f this c haracteristic, a multi-mod e o ven i s o f- ten used for bulk heating and carrying out chemical analysis processes like ashing, extraction etc. Improper control of heating of samples is a major limitation of multi-mode apparatus because of absence of temperature uniformity. This is largely due to the chaos of the waves that makes it practically impossible to Figure 2. Standing wave pattern―Generated in monomode apparatus. Figure 3. Mechanism of heating in monomode apparatus. Figure 4. Design of a multi-mode heating apparatus.  K. K. Rana, S. Rana OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100686 7 September 2014 | Volume 1 | create equal heating (actually creates hot-spots and cold-spots in the material) of the sa mples tha t are kep t inside the oven. 3.4. Conventional vs Microwave Heating Microwave heating is different from conventional heating in many respects. Difference between these two heat sources have been discussed in a wealth of literatures [ 11]-[26] which are summarized below. Conventional Heating Microwave Heating By thermal or electrical sources, heating takes place. By electromagnetic waves, heating takes place. Heatin g o f reaction mixtur e proc eeds from a surface usua lly from the insid e surf ace of reaction vessels. Heatin g o f reaction mixtur e proc eeds directly inside the mat er ial av oiding the vessel. The vessel surface is brought in physical contact with the sou r ce whi ch is at a higher tem pera ture (e.g., burner , man tle, oil bath, steam bath etc.) . No need of physical contact of reaction vessel with the higher temperature source. The reaction vessel is kept in the oven cavity and microwave source or the magnetron is k ept little further. Heati ng mechanism involve conduction of heat. Heati ng mechanism involve dielectric polarization and ionic conduc tion. In conventional heating, generally, the achievable highest temperature is limited by boiling point of a substrate. In microwave, the tempera ture of a sub strate can be rais ed hig her than , i.e., sup er heating may take plac e. In the conventi onal heating, all the components in a mi xture are heat ed almos t equally. In microwave heating, specifically a particular component can be hea ted more depending on its diel ectric characterist ics. ral (fr om 10 to 100 0 in best cases) fold high. 3.5. General Conditions/Guidelines for Microwave Synthesis Like any other scientific processes microwave irradiated reactions also have some provisions with respect to the nature of s olvents, tempe rature, pressure etc. [27]. These are described in short as below. 3.5.1. Sol ven t • Different solvents interact very differently with microwave, because of their diverse polar and ionic proper- ties. • Ethanol ( 0.941), DMF ( 0.161) and acetonitrile ( 0.062), are often used for microwave-as- sisted o rgani c s yn t he si s. Us uall y, one mig ht nee d not change the so l vent t hat i s u sua l l y us ed und er tr ad itional conditions. • Non-polar solvents, for example, THF ( 0.047), toluene ( 0.0 40) , hexa ne ( 0.020) etc. ca n b e heated only when other component s in the reac t ion mixture respond to microwave energy. • Ionic liquids are environmentally friendly and recyclable alternatives to dipolar aprotic solvents. As these are salts and readily dissolve in a wide range of organic solvents, these are better choice for MW absorption for poor absorbing reaction mixtures. The low vapor density and effective dielectric properties of ionic liquids make them highly suitable to be used as sol vents or additives in micr owave-assisted organic synthesis. • Solvents with lo w boiling points (e.g., methanol, dichloromethane, acetone etc), have lower reaction tempera- tures due to t he pr essur e build -up within the vessel. If a higher temperature is desired, it is advisable to shift to a solvent having higher bo iling po int with compatible value . 3.5.2. Volume • Too low volume will give an incorrect temperature measurement while a high volume does not leave suffi- cient head-space for pressure build-up. 3.5.3. Pressure • Usually MW reactors allow reaction pressures as high as 20 bar. In dedicated MW reactors, if pressure in a vessel becomes higher, heating is automatically stopped and cooling begins. For an indication of the ex- pected pressure of a reaction, one can use the solvent table or the vapor pressure calculator ([27] b).  K. K. Rana, S. Rana OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100686 8 September 2014 | Volume 1 | 3.5.4. Te mp e ra tu re • Optimum temperature should be as high as substrates and products allow before they start decomposing or as high as the react ion solvent allows, whic he ver is less. 3.5.5. C oncentr ation • The concentration depends on the type of chemistry that is performed. The maximum obtainable concentra- tion is dependent on the properties of the substrates and reagents as well as the properties of the solvent(s) used. A unimolecular reaction is independent of concentration and can be performed in a very dilute solution. On the other hand, bi- or tri-molecular reactions are essentially concentration dependent. Higher concentra- tion offers faster rate of reaction. 3.5.6. Inert Atm osph ere • Inert atmosphere, in general, is not initially employed in micro wave chemistry and often not needed even if the reaction is carried out under inert media in conventional method. If needed, vials are flushed with inert gas before capping. 3.5.7. Time • Generally MAOS reactions require 2 - 15 minutes of irr a diation but the time require d for a p a rticular reaction would be determined by the operator himself. 3.5.8. Reaction Optimization • Optimizing a microwave reaction is equivalent to optimizing a conventional synthesis, for example, if the first attempt is a failure, changing the temperature and reaction time may cause significant improvement. All remaining parameters that we usually change (i.e., concentration, solvent, reagent etc.) can be changed as and when r equir ed. 3.6. Microwave Assisted Organic Synthesis In recent years microwave assisted reactions has opened the door of a new era in the field of organic synthesis [28]. The technique offers simple, clean, fast, efficient and econo mic protocol for the synthesis of a large num- ber of organic molecules. Now a day’s this procedure is considered as an important weapon to employ green chemistry, since this i s signifi cantly enviro nmentall y friendly. This tec hnology is still le ss-used in the traditio nal laboratories. Conventional method of heating usually need longer time, tedious and costly apparatus setup and the e xcessive use o f solvents/reagents that ultimately lead to e nvironmental p ollution. After initiation by Richard Gedye and his co-workers [1], che mists have successfully employed MW heating in a large number of organic reactions. A plethora o f articles and reviews describing a variety of new chemistries performed with microwave irradiation have appeared [9]. Because of space constraints the major applications of microwave assisted organic syntheses are summarized in Table 4 with their correspond ing re ferences. Let us take a look at some particular reports of MW assisted organic reactions: 1) In a report [62] of the Fischer indole synthesis, primary and secondary alcohols have been catalytically oxidized in the presence of phenylhydrazines and Lewis acids to give the corresponding indoles in a single step. Replacing alde hydes o r keton es, the use o f alco hols widens the scope of a vailabili t y of sta rting materia ls a nd of - fers e asy handling a nd safety. 2) N-Sulfonyl -1,2,3-triazoles react with water in the presence of a rhodium catalyst to produce α-amino ketones in ver y goo d yield s. This co nversio n for mally a chieve s 1,2-amino hydroxylatio n of terminal alkynes in a region selective manner in combination with a copper(I)-cataly zed 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition with N-sulfonyl azides [63].  K. K. Rana, S. Rana OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100686 9 September 2014 | Volume 1 | Table 4. Few exampl es of micro wave assisted organic s ynthesis. Entry Reaction Ref. Entry Reaction Ref. 1 Acetylation reaction [29] 17 Dehalogenat ion r eaction [45] 2 Addition reaction [30] 18 Diel’s-Alder r eaction [46] 3 Alkylation reaction [31] 19 Dimerization reaction [47] 4 Alkynes metathesis [32] 20 Elimin ation rea ction [29] 5 Allylation reaction [33] 21 Estrification/Transestrification reaction [48] 6 Amination reaction [34] 22 Enantioselect ive rea ction [49] 7 Aromat ic nucleophillic substitution reaction [35] 23 Halogenation reaction [50] 8 Arylation reac tion [36] 24 Mannich reaction [ 51] 9 Cla isen-Smith reaction [37] 25 Oxidat ion reacti on [52] 10 Combinatorial reaction [38] 26 Phosphorylati on synthesis [53] 11 Condensat ion reacti on [39] 27 Polymerization reaction [54] 12 Coupling reaction [40] 28 Rear rang ement reaction [ 55] 13 Cyanation reaction [41] 29 Reduction reaction [56] 14 Cyclization reaction [42] 30 Ring closing synthesis [57] 15 Cyclo-addition reaction [43] 31 Solvent free rea ction [58] 16 Deacetylation reaction [44] 32 Hydrolysis reaction [59] Authors apologize to the numerous scientists whose works are not cited properly, in an attempt to limit the reference list. ever, asymmetric reactions, carbohydrates, CO insertions, condensations cyanations, heterocycle synthesis, reactions involving ionic liquids, Michael reactions, nucleoside synthesis, organ om etallics, benzillic acid rearrangement, -Hartwig, Heck, Suzuki, Sonogashira, Fischer carbenes, Pauson-Khand, oxidations, peptides, proteins, photochemistry, protections/deprotections, free radicals, ring -closing m etathesis ( RC M), scavengers, simultaneous -phase (solvent free) reactions , dye synthesis, halide exchange, halogenation, macrocycles, nitration, ph osgenation, polymerase chain rea ction (PCR), trypsin digestion, flavones, C-alkylation, Wittig reactionetc ecognized as m ajor succes s of MAOS. [4] [22] [60] [61] 3) Various alcohols were synthesized by metal-free coupling of diazoalkanes derived from p-toluene sulfo - nylhydra zones with wa ter un de r reflux a nd micro wa ve con di tions, in high yie lds [64]. In addition, this protocol was succes sfully applied for the s ynthesis of deut eriu m-tagged alcohols using deuterium oxide. 4) An efficient micro wave-assisted, palladiu m-catalyzed hydroxylation is reported [65] that co nvert s ar yl a nd heteroaryl chlorides to phenols in the presence of a weak base carbonate. The reaction has shown to take place in presence of ketone, aldehyde, ester, nitrile, or amide functionalities.  K. K. Rana, S. Rana OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100686 10 September 2014 | Volume 1 | 5) Microwave-irradiated condensation of carbonyl compounds with (R)-2-methylpropane-2-sulf ina mi d e u nd er solvent-free conditions in the presence of Ti(OEt)4 offers a simple, environmentally friendly synthesis of optically pure N-(tert-butylsulfinyl)imines [66]. Sulfi nyl aldimines can be pr e pared with both excellent yields and p urities in only 10 min, while the reaction time for the preparation of ketimines has been extended to 1 h. 6) An efficient microwave-assisted metal-free amino benzannulation of aryl(4-aryl -1-(prop-2-ynyl)-1H-im- idazol-2-yl)methanone with dialkylamines affords various 2,8-diaryl-6-a minoimid azo[ 1 , 2 -a]pyridines in good overall yield [67]. 7) Sequential co up ling-imination-annulation reactions of ortho-bromoarylaldehydes and terminal alkynes with ammonium acetate in the presence of a palladium catalyst under microwave irradiation fu rnishes differe nt s ubs - tituted isoquinolines, furopyridines and thienopyridines in good yields [68]. 8) M W irradiation of the nitrile substrates by the Brønsted or Lewis acid catalyst has been found to be respon- sible for rate enhancement in azide-nitrile cycloaddition [69]. Lewis acids such as Zn or Al salts perform in a similar manner, activating the nitrile moiety and leading to an open-chain intermediate that subsequently cyclizes to produce the tetrazole nucleus. The desired tetrazole products were obtained in high yields within 3 - 10 min employing controlled microwave heating. 9) A multitalented microwave-assisted procedure [70] for the palladium-catalyzed direct arylation of hetero- cycles by aryl bromides and heteroaryl bromides using MW heating features short coupling times (10 - 60 min) and lo w catalyst loadin gs. Thi s al so al lows succ e ss f ul a r ylat i on o f p r evio usly fo und u nre a c tive het er o c yc lic s ub - strate s. 10) A co mparatively easier MW assisted three-step route enabled the synthesis of arylacetaldehydes from the corresponding carboxylic acids in very high yields. A subsequent microwave-assisted Gewald reaction [71] gives  K. K. Rana, S. Rana OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100686 11 September 2014 | Volume 1 | 5-substituted-2-aminothiophenes in short time, with high yield s and p urities . 11 ) A straightforward and efficient Yb(OTf)3 catalyzed three-component reaction of aldehydes, alkynes and amines under microwave irradiation in an ionic liquid has been developed. A number of 2,4-disubst it ute d q ui no - lines have been synthesized in excellent yield (69% - 93%) under mild reaction condition [72] and th e catalyst is reused up to four times. 12) 3,3′-Br2-BINOL has been shown to catalyze the enantioselective asymmetric propargylation of ketones using allenyldioxoborolane as nucleophile, in absence of solvent and under micro wave irradiation to afford ho- mopropargylic alcohols in good yields (60% - 98%) and high enantio meric ratios (3 :1 - 99:1) [73]. Diastereose- lective propargylations using chiral racemic allenylboronates result in good diastereoselectivities (dr > 86:14) and enantioselec tivities (er > 9 2:8) under the catalytic conditions. 13) A facile, pro ficient and large-scale procedure for the synthesis of N-(1-oxo-1H-inden-2-yl)benzamide de- rivatives via domino reaction between aryl aldehydes, hippuric acid and acetic anhydride is catalyzed by HPW/ nano -SiO 2 under microwave irradiation [74]. The reactio n conditions are trouble -free and offer easy isolation of the product. Moreover, the catalyst can be reused up to five times after simple filtration. 14) ZrOCl 2∙8H2O has been identified as a highly successful, water-tolerant and reusable catalyst for the direct condensation of carboxylic acids and N,N′-dimethylurea under microwave irradiation to give the corresponding N-methylamides in moderate to e xcellent yields [75]. Due to its easy availabilit y, efficient activity, low cost a nd toxicity, ease of handling, easy recovery and reusability, ZrOCl2∙8H2O is considered as a useful green catalyst. 15) The efficient and simple technique for phosphine-free Heck reactions in water in the presence of Pd(L- proline)2 complex as the catalyst under controlled microwave irradiation conditions is reported [76] to be versatile. This provides excellent yields in much short reaction times. In fact, the reaction minimizes costs, operational hazards and environmental pollution.  K. K. Rana, S. Rana OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100686 12 September 2014 | Volume 1 | 16) Aromatic nucleophilic substitutions are carried out using sodium phenoxide and 1,3,5-trichlorotriazine under microwave irradiation [77] [78]. 17) Under microwave irradiation a number of azaheterocycles (i.e., pyrrole, imidazole, pyrazole, indole, and carbazole) shown to react [79] remarkably fast with alkyl hal ides to give exclusively N-alkyl derivatives. 18) Condensation of acetylarenes with benzaldehydes under microwave irradiation affords [80] chalcones which undergo facile and clean cyclizations with hydrazines (RNHNH2, R=H, Ph, Ac) to afford 3,5-arylated 2-pyrazoline s in quantita tive yields, al so under microwave irradiation and in the presence of dry AcOH as c yc- lizing agent. This is actually an example of Claisen-Smith reaction under MW irradiation. The results obtained indicate that unlike classical heating, microwave irradiation results in higher yields, shorter reaction times (2 - 12 min) and cleaner reactions. 3.7. Advantages of Microwave Chemistry [81] Microwave radiation has proved to be a highly effective heating source in chemical reactions. Microwaves can speed up the reaction rate, afford better yields and uniform as well as selective heating, achieve better reprodu- cibility of reactions and help in improving cleaner and greener synthetic pathways. Increased Rate of Reactions [82]: Co mpared to conventional heating, microwave heating enhances the rate of certain chemical rea c tions by 10 to 1000 times. This is due to its ability to consid erably augment the temperature of a reaction, for instance, synthesis of fluorescein, which usually takes about 10 hours by conventional heating methods, can be conducted in only 35 minutes by means of microwave heating (Table 5). Efficient Source of Heating [83]-[85]: Heating by means of microwave radiation is a highly resourceful process and results insignificant energy savings. This is primarily because microwaves heat up just the sample and not the apparatu s and therefore, energy consumptio n is less. A typical example is the use of micr owave radia- tion in the ashing process. Since microwave ashing devices can reach temperatures of over 800˚C in ~50 mi- nutes , the y elimi nate the length y heatin g-up periods associa ted with conventio nal electrical-resistance furnaces. This drastically lowers the associated energy costs.  K. K. Rana, S. Rana OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100686 13 September 2014 | Volume 1 | Table 5. Comparison of reaction duration (in minutes). Reaction Conventi on a l Microwave Synthesis of Flu o rescein 6 00 35 Condentation of Benzoin with Urea 60 8 Biginelli R eactio n 3 60 35 Synthesis of Aspirin 130 1 Synthesis of Phenothiazine 60 4 Higher Yields [86]: In certain chemical reactions, microwave radiation produces higher yields compared to conventional heating methods, for example, microwave synthesis of fluorescein results in an increase in the yield of the reaction, from 70% to 82% (Table 6). Uniform Heating: Microwave radiation, unlike conventional heating methods, provides uniform heating through- out a reaction mixture. Selective Heating: Selective heating is based on the principle that different materials respond differently to microwaves. Some materials are transparent whereas others absorb microwaves. Therefore, microwaves can be used to heat a combination of such materials. Environmentally-Friendly Chemistry [87]: Reactions performed in microwaves are reasonably cleaner and more environmentally friendly than conventional heating methods. Microwaves heat the compounds directly therefore, usage of solvents in the chemical reaction can be reduced or eliminated. Greater Reproducibility of Chemical Reactions: Reactions with microwave heating are more reproducible compared to conventional heating because of uniform heating and better control of process parameters. 4. Question of Greenness: A Comment Assessment of “greenness” of microwave assisted transformations is a relatively complex job that demands con- sideration of different factors into account. The issue of the energy efficiency of microwave vs. conventionally heated reactions must, in general, be estimated with great care on a case-by-case basis. However, as a number of studies have d emonstrated, it should be emphasized that the microwave heating process performed in laboratory- scale single-mode microwave reactors is sufficiently energy inefficient [88]. As t he irresistible bulk o f the mor e than 5000 published microwave chemistry experiments rely on the use of this type of equipment, it is highly questionable whether this non-classical form of heating should be labeled as being green, sustainable or envi- ronmentally friendly, based on energy efficiency considerations. However, when moving from laboratory scale to kilogram scale and from single-mode to multimode reactors, microwave heating processes can indeed be more energy efficient than conve ntionally heated experiments, assuming otherwise conditions remain identical. This has been highlighted in a number of recent studies derived from different laboratories [88]. 5. Limitations of Microwave Chemistry [83] [84] The limitations of microwave chemistry are linked to its scalability, limited application, and the hazards in- volved in its use . Lack of Scalab ility: The product obtained by using micro wave apparatus available in the market is restricted to a fe w gra ms. T hough t here ha s been impro vement in the recent past, rela ting to the sca lability [87] of micro - wave apparatus, there is still a space that needs to be lin ked to make the machinery scalable. This is principa lly true for reactions at the industrial level and for solid-state reac tions. Limited Applicabilit y: The use of microwaves as a heating source has restricted applicability for materials that absorb them. Microwaves cannot heat materia ls such a s sul phur, whic h are tra nspare nt to thei r radia tion. I n ad- dition, although microwave heating increases the rate of reaction in certain reactions, it also results in yield re- duction compared to conventional heating methods [89]. Safety Hazards Related to the Use of Microwave-Heating Apparatus: Even though makers of microwave- heating apparatus have directed their research to make microwaves a secure source of heating, uncontrolled reaction involving volatile reactants under superheated conditions may result with explosions. Furthermore, in-  K. K. Rana, S. Rana OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100686 14 September 2014 | Volume 1 | Table 6. Comparison of yields (%). Reaction Conventi on a l Microwave Synthesis of Flu o rescein 70 82 Condentation of Benzoin with Urea 70 73 Biginelli R eactio n 70 75 Synthesis of Aspirin 85 92 Synthesis of Phenothiazine 71 86 appropriate use of microwave heating for rate enhancement of chemical reactions involving radioisotopes may result in uncontrolled and harmful radioactive decay. Certain evils, with dangerous end results, have also been observed while conducting polar acid-based reactions, e.g., microwave irradiation of are action involving con- centrated sulphuric acid may spoil the polymer vessel used for heating. This is because sulphuric acid is a strong coupler of microwave energy and raises the reaction temperature to 300˚C within a ver y short time. As a r esult, the po lymer micro wave-heati ng cont ainer may melt, with hazardous consequences [90]. Cond ucti ng micro wa ve reactions at high-pressure conditions may also result in uncontrolled reactions and cause explosions. Health Risk Related to the Use of Microwave-heating Apparatus: Health hazards in connection with micro- waves are caused by the penetration of microwaves. When microwaves operating at a low frequency range are only able to penetrate the human skin, higher freque ncy-range microwaves have been found to reach body or- gans. Studies have proven [91] that on extended exposure to microwaves may result in the complete degenera- tion of body tissues and cells. It has also been established th at constant exposure of DN A to high-freque ncy mi- crowaves during a biochemical reaction may lead to complete degeneration of the DNA strands. Research has bee n car ried o ut to under stand this p heno meno n and two sc hoo ls o f thoug hts ha ve evo lve d. T he fir st is b ased on the thermal degeneration of DNA by microwave irradiation and believes that microwaves have enough energy to disrupt the covalent bo nd of a DNA strand. T he other discipline of thought is e mphatic abo ut the existence of a “non-thermal microwave effect”. Kakita et a l. [92] [93] have sho wn that in identical ther mal conditio ns, micro- wave irradiated DNA strands are different from those heated under conventional heating methods. Microwave irradiated DNA strands were habitually damaged whic h does not occur in conventional heati ng. This discovery has restricted the use of microwave heating to only biological reactions. Other limitations: • Sudden increase in temperature may lead to the distortion o f molecular str uctures which may lead to rap ture of them and may yield undesired products [94]. • MAOS reactions are generally short-timed, so, always a care must be taken during the process [95]. • Temperature sensitive reactions, reactions involving bumping of materials or reactions which involve effer- vescences are ordinarily difficult to perform in Microwave reactors [96]. • Since heating takes place too fast, sometimes reactions become vigorous and to some extent hazardous [96]. • Dedicated or focused microwave reactors are generally expensive and therefore, special care must be taken duri ng and after their use [96]. 6. Future Prospect and Conclusions As with almost all instances of incorporation of new technology in an industrial set up, the question remains: Is it being emplo yed to the level o f maximum extent possible? At the prese nt time, micro wave-assi sted o rganic syn- thesis is no lon ger a curio sit y b ut a pro mising tech nolo gy w hose full la tent po ssibilit y ha s yet not b een e xplor ed. The use of microwave ovens to heat reactions is a paradigm shift for nearly all trained synthetic chemis ts. In reality , the use of microwaves as an energy source requires a mind-set cha nge in the way in which synthetic chemi s try i s practised. Initial use requires conversion of traditional reaction conditions to microwave conditions. Household MW ovens create n ot only sudden untoward incidents but also af fect the quality of publications [22]. Even though, most MAOS reactions are unfortunately still performed in domestic household ovens. If truth be told, for example, the use of 70% of full power for 5 minutes in a domestic microwave oven will never be a quantitative measure- ment of the energy delivered to a reaction [22]. Hence, novel, dedicated and refined MW reactors with ability to reproduce performance and minimal hazard should be used rather than the domestic counter-top variants. New  K. K. Rana, S. Rana OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100686 15 September 2014 | Volume 1 | development in MW reactors and vessel designing are required with respect to scale-u p, high through put and m ore reliable temperature contro l. In future, with discovery of new MW assisted reactions, suitable technologies will also be developed to carry out these reactions on industrial scales. In concert with rapidly expanding application possibilities, microwave synt hesis can be effectively ap plied to any cate gory of synthetic c hemistry, r esulting in faster reaction times and improved product yields. At present, the benefits of m icrowaves as a source of ener gy for heatin g chemical reactions are adequately clear. What is less clear , as with most innovative techni ques or technologies, is what is the rate of uptake of this approach and what factors are affecting the impleme ntation rate. T hough the percentage of reactions being performed with microwave irradiation has not been quantified appropriately, the use of microwave energy to promote a diverse range of che mistr y is co nti nuousl y escala tin g. It is interesting to note that the country in which the technique seems to be most accepted, according to the number of publications, is India [22]. Thi s illustrates that the MAOS reactions possess enormous potential to be a very sturdy tactical tool for advancement of basic sciences even in the financially disadvantageous regions of the globe. With the rapidly expanding number of published examples and the readily available tips and tools that accompany commercial instrumentation, the leap from traditional heating to microwave heating is far les s disapp ointing t han whe n the field began. De spite several li mitatio ns and restrictions, use of microwave heating in MAOS chemistry will continue to grow and is likely to become a standard procedure in coming years. References [1] Gedye, R., Smith, F., Westaway, K., Ali, H., Baldiser a, L., Laberge, L. and Rousel l, J. (1986) The Use of Microwave Ovens for Rapid Organic Synthesis. Tetrahedron Letters, 27, 279-282. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0040-4039(00)83996-9 [2] Giguere, R.J., Bray, T.L. and Duncan, S.M. (1986) Application of Commerci al Mi cro wave Oven to Organ i c S ynt hesi s. Tetrahedron Letters, 27, 4945 -494 8 . http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0040-4039(00)85103-5 [3] Jin, Q.H. (1999) Microwave Chemistry. Scien ce Press, Beijing. [4] Kappe, C.O. (2004) Controlled Microwave Heating in Modern Organic Synthesis. Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 43, 6250-6284. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anie.200400655 [5] (a) Pradhan, D.K., Dharamrajan, T.S., Mishra, M.R. and Mishra, A. (2012) An Overview of Microwave Oven in the Field of Synthetic Chemistry. International Journal of Research and Development in Pharmacy & Life Sciences (IJRDPL), 44, 44-50. (b) Taylor, M., Atri, S.S. and Minhas, S. Evalueserve Analysis: Developments in Microwave Chemistry. www.rsc.o r g/imag es/ eval u eserv e _ tcm18 -16758.pdf (c) Horeis, A.G., Pichler, S., Stadler, A., Gössler, W. and Kappe, C.O. (2001 ) Mi cro wave-Assisted Organic Synthe- sis—Back to the Roots. 5th International Electronic Conference on Synthetic Organic Chemistry (E CSOC -5), Basel, 1-30 September 2001. http://www.mdpi.org/ecsoc-5.htm [6] http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/3197/8/08_chapter%201.pdf [7] The type of radiation emitted by MW ovens is non-ionizing. This means that unlike X-ra y or UV light , it do es no t ha ve potent ial to cause cancer. Although it possess possi ble heat -burn risks. Dr. Spencer himself, despite being literally sur- rounded by intense microwaves for a long period of his life, lived to the ripe old age of 76, dying apparently of nat- ural causes. (a) Stuerga, D. and Delmotte, M. (2002) Chapter 1. Wave-Material Interactions, Microwave Technology and Equip- ment. In: Loupy, A., Ed., Microwaves in Organic Synthesis, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 1-34. (b) Mingos, M.D.P. (2004) In: Lid st r o m, P. and Tier ne y, J.P. , Eds., Microwave-Assisted Organic Synthesis, Blackwell , Oxford. (c) Gabriel, C., Gabriel, S., Grant, E.H., Halstead, B.S. and Mingos, D.M.P. (1998) Dielectri c Parameters Relevant to Micro wave Dielectric Heat ing. Chemical Society Review s , 27, 213-223. (d) Kerr, J.A. (1992) Strengths of Chemical Bonds. In: Lide, D.R., Ed., CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 76th Edition, CRC Press, Boca Raton, Ann Arbor, London, Tokyo, 51. (e) Atkins, P.W. (1990) Physical Chemistry. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 938. (f) Stuerga, D.A.C. an d Gaillard, P. ( 1996) Microwave Athermal Effects in Chemistry: A Myth’s Autopsy Part I: His- torical Background and Fundamentals of Wave-Mat ter Interact ion. The Journal of Microwave Power Electromagnetic Energy, 31, 87-100. [8] In s pecific cases, magnetic fiel d inter actions have als o been observed, see: (a) Stass, D.V., Woodward, J.R., Timmel, C.R., Hore, P.J. and McLauchlan, K.A. (2000) Radiofrequency Magnetic Field Effects on Chemical Reaction Yields. Chemical Physics Letters, 329, 15-22.  K. K. Rana, S. Rana OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100686 16 September 2014 | Volume 1 | http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0009-2614(00)00980-5 (b) Timmel, C.R. and Hore, P.J. (1996) Oscillating Magnetic Field Effects on the Yields of Radical Pair Reactions. Chemical Physi cs Letters, 257 , 401-408. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0009-2614(96)00466-6 (c) Woodward, J.R., Jackson, R.J., Timmel, C.R., Hore, P.J. and McLauchlan, K.A. (1997) Resonant Radiofrequency Magneti c Field E ffects on a Chemical R eaction. Chemical Physics Letters, 272, 376-382. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0009-2614(97)00542-3 [9] Hayes, B.L. (2002) Microwave Synthesis: Chemistry at the Speed of Light. CEM Publishing, Matthews NC and Ref- erences Cited Therein. [10] Gaba, M . and Dhin gra, N. (2011) Microwave Chemist ry: General Feat ures and Applications. Indian Journal of Phar- maceutical Education and Research, 45, 175-183. [11] http ://www.milestonesci.com [12] http ://www.maos.net [13] http ://www.cem.com [14] Westaway, K.C. and Gedye, R.J. (1995) The Question of Specific Activation of Organic Reactions by Microwaves. Journal of Microwave Power and Electromagnetic Energy, 30, 219-230. [15] Kuhnert, N. (2002) Microwave-Assisted Reactions in Organic Synthesis—Are There An y Nonthermal Micr owave Ef- fects? Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 41, 1863-1866. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1521-3773(20020603)41:11<1863::AID-ANIE1863>3.0.CO;2-L [16] Langa, F., De la Cruz, P ., De la Hoz, A., Diaz-Ortiz, A. and Diez-Barra, E. (1997) Microwave Irra diation: More t han Just a Met hod for Accelerati ng Reactions. Contem porary Or ga nic Synthe s i s , 4, 373-386. http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/co9970400373 [17] Saillard, R., Poux, M., Berlan, J. and Audhvy-Peaudecer t, M. (1995 ) Microwave Heat ing of Organic Solvents: Thermal Effects and Field Modeling. Tetrahed r on , 51, 4033-4042. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0040-4020(95)001 44 -W [18] Stuerga, D. and Gaillard, P. (1996) Microwave Heatin g as a New Way to I ndu ce Localized Enhan cements of Rea ction Rate. Non-Isothermal and Het erogeneous Kinet ics. Tetrahedr on , 52, 5505-5510. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0040-4020(96)00241-4 [19] Caddick, S. (1995) Microwave Assisted Organic Reactio ns. Tetr ahedron , 51, 10403-10432. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0040-4020(95)00662-R [20] Strauss, C. R. and Trainor, R.W. (1995) Developments in Microwave-Assisted Organic Ch emistry. Australian Journal of Chemist ry, 48, 1665-1692. htt p: / / d x. do i .o r g/ 1 0. 1071/ CH 9 95 1665 [21] Bose, A.K., Banik, B.K., Lavlinskaia, N., Jayaraman, M. and Manhas, M.S . (19 97 ) MORE Ch emistry in a Microwave. Chemtech , 27, 18-124. [22] Lidstrom, P., Tierney, J., Wathey, B. and Westman, J. (2001) Microwave Assisted Organic Synth esis—A Rev ie w. Te- trahedron, 57, 9225-9283. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0040-4020(01) 00 906-1 [23] Nu ch ter, M., Ondruschka, B. and Lautenschlager, W. (2003) Microwave-Assisted Chemical Reactions. Chemical En- gineering & Technology, 26, 1208-1216. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ceat.200301836 [24] Nuchter, M., Ondruschka, B., Bonrath, W. and Gum, A. (2004) Microwave Assist ed Synthesis—A Critical Technology Overvi ew. Green Chemistry, 6, 128-141. http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/b310502d [25] Abramovitch, R.A. (1991) Applications of Microwave Energy in Organic Chemistry. A Review. Organic Preparations and Procedures International, 23, 683-711. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00304949109458244 [26] Leadbeater, N.E. (2010) In Situ Reaction Monitoring Of Microwave-Mediated Reactions Using IR Spectroscopy. Chemical Communications, 46, 6693-6695. http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/c0cc01921f [27] (a) http://www.mrl.ucsb.edu/polymer-characteriz at io n -facility/instruments/microwave-reacto r-b io tage (b)http://www.biotagepathfinder.com/pressurePC.jsp [28] For recent r evi ews o n microwave-assisted organic synthesis see: (a) Adam, D. (2003) Microwave Chemistry: Out of the Kitchen. Nature, 421, 571-572. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/421571a (b) Kappe, C.O. and Dallinger, D. (2006) The Impact of Microwave Synthesis on Drug Discovery. Nature Reviews Drug Disco very, 5, 51-63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrd1926 (c) Nagariya, A.K., Meena, A.K., Kiran, K. , Yadav, A.K., Niranjan, U.S., Pathak, A.K., Singh, B. and Rao, M.M. (2010) Microwave Assisted Organic Reaction as New Tool in Organic Synthesis. Journal of Pharmacy Research, 3, 575-580. (d) Jignasa, K.S., Ketan, T.S., Bhumika, S.P. and Anuradha, K.G. (2010) Microwave Assisted Organic Synthesis: An Alternative Synthetic Strategy. Der Pharma Chemica , 2, 342-353.  K. K. Rana, S. Rana OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100686 17 September 2014 | Volume 1 | (e) Bose, A.K., Banik, B.K., Lavlinskaia, N., Jayaraman, M. and Manhas, M.S. (1997) MORE Chemistry in a Micro- wave. Chemt ech, 27, 18-24. (f) Bose, A.K., Manhas, M.S., Ganguly, S.N., Sharma, A.H. and Banik, B.K. (2002) MORE Chemistry for Less Pol lu- tion: Applications for Process Development. Synthesis, 11, 1578-1591. http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-2002-33344 [29] Moghaddam, F.M. and Sharifi, A. (1995) Microwave Promoted Acetalization of Aldehydes and Ketones. Synthetic Communications, 25, 2457-2461. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00397919508015450 [30] Mogilaiah, K., Kavita, S. an d Babu, H.R. (2003) Microwave Assisted Addition-Elimination Reactions of 3-Phenylimino- 2-Indolinones with 2-Hydrazino-3-(p-Chlorophenyl)-1, 8-Naphthyridine: A Simple and Facile Synthesis of 3-(3-p-Chlor- ophenyl-l,8-Naphthyridin-2-yl Hydrazono)-2-Indolinones. Indian Journal of Chemistry, 42B, 1750 -1752. [31] Abramovitch, R.A., Shi, Q. and Bogdal, D. (1995) Microwave-Assisted Alkylations of Activated Methylene Groups. Synthetic Communications, 25, 1-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00397919508010781 [32] Miljanic, O.S., Volhardt, K.P.C. and Whitener, G.D. (2003) An Alkyne Metathesis-Based Route to ortho-Dehydro- benzan nul en es. Synlett, 1, 29-34. [33] Motorina, I.A., Parly, F. and Grierson, D.S. (1996) Selective O-Allylation of Amidoalcohols on Solid Support. Syn lett, 4, 389-391. http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-1996-5416 [34] Mccarroll, A.J., Sandham, D.A., Titumb, L.R., Dek Lewis, A.K., Cloke, F.G.N., Davies, B.P., Desantand, A.P. , Hiller, W. an d Caddicks, S. (2003) Stud ies on High -Te mperature Aminati on Reaction s of Aromatic Chl orides Using Di screte Palladium-N-Heterocyclic Carbene (NHC) Complexes and in Situ Palladium/Imidazolium Salt Protocols. Molecular Diversity, 7, 115-123. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/B:MODI.0000006863.14423.da [35] Angrish, C., Kumar, A. and Chouhan, S.M.S. (2005) Microwave Assisted Aromatic Nucleophilic Substitution Reaction of Chloronitrobenzenes with Amines in Ionic Liquids. Indian Jo urnal of C he m is t ry, 44B, 1515-15 18 . [36] Ermolat’ev, D.S., Giménez, V.N., Babaev, E.V. and Van der Eycken, E. (2006) Efficient Pd(0)-Mediated Micro wave- Assisted Arylation of 2-Substituted Imidazo[1,2-a]Pyrimidines. Journal of Combinatorial Chemistry, 8, 659-663. [37] Azarifar, D. and Ghasemnejad, H. (2003) Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Some 3,5-Arylated-2-Pyrazolin es. Mole- cules, 8, 642-648. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/80800642 [38] Al-Obeidi, F., Austin, R.E., Okonoya, J.F. and Bond, D.R.S. (2003) Microwave-Assisted Solid-Phase Synthesis (MASS): Parallel and Combinatorial Chemical Library Synthesis. Mini-Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry, 3, 449-460. http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/1389557033488042 [39] Kim, J.K., Kwon, P.S., Kwon, T.W., Chung, S.K. and Lee, J.W. (1996) Application of Microwave Irradiation Tech- niques for the Knoevenagel Condensation. Synthetic Communications, 26, 535-542. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00397919608003646 [40] Burten, G., Cao, P., Li, G. and Rivero, R. (2003) Palladiu m-Catalyzed Intermolecular Coupling of Aryl Chlorides and Sulfonamides under Microwave Irradiation. Organic Letters, 5, 4373 -4376. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ol035655u [41] Arevel a, R.K. an d Leadbeat er, N.E. (20 03) Rapid, Easy Cyanation of Aryl Bromides and Chlorides Using Nickel Salts in Conjunction with Microwave Promotion. Journal of Organic Chemistry, 68, 91 22-9125. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jo0350561 [42] Crawford, K.R., Bur, S.K., Straub, C.S. and Padwa, A. (2003) Intramolecular Cyclization Reactions of 5-Halo - and 5-Nitro-Substituted Furans. Organic Lett ers , 5, 3337 -3340. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ol035233k [43] Lerestif, J.M., Peroch eav, J., Tonnard, F., Bazareav, J.P. and Hamelin, J. (199 5) 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition of Imidate Ylides on Imino-Alcohols: Synthesis of New Imidazolones Using Solvent Free Conditions. Tetrahedron, 51, 6757- 6774. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0040-4020( 95 ) 00 321-X [44] Jayakumar, G., Ajithabai, M.D., Santhosh, B., Veena, C.S. and Nair, M.S. (2003) Microwave Assist ed Acetylation an d Deacetylation Studies on the Triterpenes Isolated from Dysoxylum malabaricum and Dysoxylum beddomei. Indian Journal of Chemistry, 42B , 429-431. [45] Calinescu, I., Calinescu, R., Martin, D.I. and Radoiv, M.T. (2003) Microwave-Enhanced Dechlorination of Chloro- benzen e. Research on Chemical Intermediates, 29, 71-81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/156856703321328424 [46] Mavoral, J.A., Cativicla, C., Garcia, J.I., Pires, E., Rovo, A.J. and Figueras, F. (1995) Diels-Alder Reactions of α-Amino Acid Precursors by Heterogeneous Catalysis: Thermal vs. Microwave Activation. Applied Catalysis A, 13 1, 159-166. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0926-860X(95)00131-X [47] Santagoda, V., Fiorino, F., Perissuti, E., Severino, B. , Terracciano, S. , Cirino, G. and Caliendo, G. (2003) A Conven- ient Strategy Of Dimerizatio n By Microwave Heating And Usi ng 2,5-Di ketopip erazine As Scaffold. Tetrahedron Let- ters, 44, 1145-1148. [48] Mazo, P.C. and Ríos, L.A. (2010) Esterification and Transesterification Assisted by Microwaves of Crude Palm Oil:  K. K. Rana, S. Rana OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100686 18 September 2014 | Volume 1 | Homogeneous Catalysis. Latin American Applied Research, 40, 343-349. [49] Diaz-Ortiz, A., De la Hoz, A., Merrero, M.A., Prieto, P., Sanch ez-Migallon, A., Cassio, F.P., Arriela, A., Vivanco, S. and Foces, C. (2003) Enhancing Stereo chemical Diversit y by Mea ns of Microwave Irradiatio n in the Absence o f Sol- vent: Synthesis of Highly Substituted Nitroproline Esters via 1,3-Dipolar Reactions. Mo lecular Diversi ty, 7, 175-180. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/B:MODI.0000006799.01924.2e [50] Jnagaki, T., Fukuhara, T. and Hara, S. (2003) Effective Fluorination Reaction with Et3N.3HF under Microwave Irra- diation. Synthesis, 8, 1157-1159 . [51] Lech man n, F., Pilotti, A. and Luthman, K. (2003) Efficient Large Scal e Micr owave Ass isted Man n ich React ion s Usin g Substituted Acetophenones. Molecular Diversity, 7, 145-15 2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/B:MODI.0000006809.48284.ed [52] Kiasat, A.R., Kazemi, F. and Rafati, M. (2003) Microwave Promoted Rapid Oxidation of Alcohols Using Cobalt Ni- trate Hexahydrate Supported on Silica Gel Under Solvent Free Conditions. Synthetic Communications, 33, 601-605. http://dx.doi.org/10.1081/SCC-120015814 [53] Gospondinova, M., Gredard, A., Jeannin, M., Chitanv, G.C., Carpov, A., Thiery, V. and Besson, T. (2002) Efficient Solvent-Free Microwave Phosphorylation of Microcrystalline Cellulose. Green Chemistry, 4, 220-222. http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/b200295g [54] Vu, Z.T., Liu, L.J. and Zhuo, R.X. (2003) Microwave-Improved Polymerization of ϵ-Caprolactone Initiated by Car- boxylic Acids. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry, 41, 13-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pola.10546 [55] Srikrishana, A. and Kumar, P.P. (1995) Naphthalenes M icrowave Ir radiat ion Indu ced Rearran gemen t on Mo ntmorillo- nite K-10. Tetr ahe dron Le t te r s , 36, 6313-6316. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0040-4039(95)01219-8 [56] Danks, T.N. and Wagner, G. (2005) Microwave-Assisted Reductions. In: Tierne y, J.P . and Lids tröm, P., Eds., Micro- wave Assi s ted Organ ic Synthesis, Blackwell Publishing Ltd., Oxford. http:// d x. do i .o r g/ 10 . 1002/ 97 814 44305 54 8. c h 4 [57] Garba cia, S., Desai, B., Lavastre, O. and Kapp e, C.O. (2003) Microwave-Assisted Ring-Closing Metathesis Revisited. On the Question of the Nonthermal Microwave Effect. Journal of O r ganic Chem i s tr y, 68, 9136-91 39 . http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jo035135c [58] Laurent, A., Jacquault, P., Di Martino, J.L. and Hamelin, J. (1 995) Fast Synthesis of Amino Acid Salts and Lactams without Solvent under Microwave Irradi ation. Chem. Commun., 11, 1101. [59] Nielsen, T.E. and Schreiber, S.L. (2007) Towards the Optimal Screening Collection: A Synthesis Strategy. Ange- wandte Chemie International Edition, 47, 48-56. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anie.200703073 [60] (a) H ayes, B.L. (2004) Recent Advances in Mi cro wave-Assisted Synthesis. Aldrichimica Acta, 37 , 66-76. (b) Bogdal, D. (2005) Microwave-Assisted Organic Synthesis: One Hundred Reaction Procedures (Tetrahedron Or- ganic Ch emistry). Elsevi er Science, Amsterdam. [61] (a) Seijas, J.A., Vázquez-Tato , M.P. and Carballido-Reboredo, R. (2005) Solvent-Free Synthesis of Functionalized Flavones under Microwave Irrad iation. Journal of Organic Chemistry, 70, 2855-2858. (b) Ranu, B.C., Guchhait, S.K., Ghosh, K. and Patra, A. (2000) Construction of Bicyclo[2.2.2]octanone Systems by Mi- crowave-Assisted Solid Phase Michael Addition Followed by Al2O3-Mediated Intramolecular Aldolisation. An Eco-Friendly Approach. Green Chemistry, 2, 5-6. htt p://dx.doi.org/10.1039/a907689a [62] Po rchedd u, A., Mur a, M.G., De Luca, L., P izzett i, M. and Tad dei, M. (2012) From Alcohols to Indoles: A Tandem Ru Catal yzed Hydrogen-Tr ansfer Fi scher Indole Synthesi s . Or ganic Letters, 14, 6112-6115. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ol3030956 [63] Miura, T., Biyajima, T., Fujii, T. and Murakami, M. (2012) Synthesis of α-Amino Ketones from Terminal Alkynes via Rhodium-Catalyzed Denitrogenative Hydration of N-Sulfonyl-1,2,3-Triazoles. Journal of the American Chemical So- ciety, 134, 194-196. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ja2104203 [64] Garcí a-Muñoz, Á., Ortega-Arizmendi, A.I., García-Carrillo, M.A., Díaz, E., Gonzalez-Ri vas, N. an d Cuevas-Yañe z, E. (2012) Direct, Metal-Free Synthesis of Benzyl Alcohols and Deuterated Benzyl Alcohols from p-Toluenesulfonylhy- drazones Using Water as Solvent. Synthesis, 44, 2237-2242. http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-129 037 2 [65] Yu, C.W., Chen, G.S., Huang, C.W. an d Chern, J.W. (2012) Efficient Microwave-Assisted Pd-Catalyzed Hydroxyla- tion of Aryl Chlorides in the Presence of Carbonate. Organic Letters, 14, 3688-3691. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ol301523q [66] Collados, J.F., Toledano, E., Guijarro, D. and Yus, M. ( 2012) Microwave-Assisted S olvent-Free Synth esis of Ena ntio- merically Pure N-(Te r t-Butylsulfinyl)Imines. Journal of Organic Chemistry, 77, 5744-57 50 . http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jo300919x [67] Nagaraj, M., Boominathan, M., Muthusubramanian, S. and Bhuvanesh, N. (2012) M icr owave-Assisted Metal-Free Synthesis of 2,8-Diaryl-6-Aminoimidazo-[1 ,2-a]Pyridine via Amine-Triggered Ben zannu lation . S yn lett, 23 , 1353-1357.  K. K. Rana, S. Rana OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100686 19 September 2014 | Volume 1 | http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1290979 [68] Yang, D., Burugupalli, S., Daniel, D. and Chen, Y. (2012) Microwa ve-Assisted One-Pot Synthesis of Isoquinolines, Furopyridines, and Thienopyridines by Palladium-Catalyzed Sequential Coupling-Imination-Annulation of 2-Bromoary- laldehydes with Terminal Acet yle nes and Ammoni um Acetate. Journal of Organic Chemistry, 77, 4466-4472. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jo300494a [69] Cantillo, D., Gutmann, B. and Kappe, C.O. (2011) Mechanistic Insights on Azide-Nitrile Cycloadditions: On the Dial- kyltin Oxide-Trimethylsilyl Azide Route and a New Vilsmeier-Haack-Type Organocatalyst. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 133, 4465-4475. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ja109700b [70] Bagh banzadeh, M., Pi lger, C. and Kappe, C.O. (20 11) Palladium-Catalyzed Direct Aryl ation of Hetero aromatic Com- pounds: Improved Conditions Utilizing Controlled Microwave Heating. Journal of Organic Chemistry, 76, 8138-8142. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jo201516v [71] Revelant, G., Dunand, S., Hesse, S. and Kirsch, G. (2011) Microwa ve-Assisted Synthesis of 5-Substituted 2-Amino- thiophenes Starting from Arylacetaldehydes. Synthesis, 2011 , 2935-2940. [72] Kumar, A. and Rao, V.K. (2011) M icr o wave-Assisted and Yb(OTf)3-Promoted One-Pot Multicomponent Synthesis of Substituted Quinolines in Ionic Liquid. Synlett, 15, 2157-2162. http://d x. doi.or g/ 1 0. 1055/s -00 30-1261 200 [73] Barnett, D.S. and Schaus, S.E. (2011) Asymmetric Propargylation of Ketones Using Allenylboronates Catalyzed by Chiral Biphenols. Organic Letters, 13, 4020-4023 . http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ol201535b [74] Rostami, M., Khosropour, A.R., Mirkhani, V., Mohammadpoor-Baltork, I., Moghadam, M. and Tangestaninejad, S. (2011) An Efficient, Simple, and Scaleable Domino Reaction to Diverse N-(1-Oxo -1H-inden-2-yl)benzamides Cata- lyzed by HPW at Nano-SiO2 under Micro wave I r radiation. Syn lett, 2011, 1677-1682. [75] Talukdar, D., Saikia, L. and Thakur, A.J. (20 11) Zirconyl Chloride: An Efficient, Water-Tolerant, and Reusabl e Cata- lyst for the Synthesis of N-Methylamides . S yn let t, 11, 1597-1601. [76] Allam, B.K. and Singh, K.N. (2011) An Efficient Phosphine-Free Heck Reaction in Water Usin g Pd(L-Proline)2 as th e Catal yst Un der Microwave Irradiation. Synthesis, 2011, 1125-1131. [77] Seijas, J.A., Vazquez-Tato, M.P., Martinez, M.M. and Corredoira, G.N. (1999) Direct Synthesis of Imides from Di- carboxylic Acids Using Microwaves. Journal of Chemical Research, 1999, 4 20 -42 5. [78] Dahmani, Z., Rahmouni, M., Brugidou, R., Bazureau, J.P. and Hamelin, J. (1998) A New Route to α-Hetero β-Ena- mino Esters Using a Mild and Convenient Solvent-Free Pro cess Assisted by Focus ed Microwave Irradiat ion. Tetrahe- dron L etters, 39, 8453-8456. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0040-4039(98)01894-2 [79] Bogdal, D., Pielichows k i, J. and Jaskot, K. (1997) Remarkable F ast N-Alkylation of Azaheterocycles under Microwave Irradiation in Dry Media. HeteroCycl es, 45, 715-722. http://dx.doi.org/10.3987/COM-96-7731 [80] Azarifar, D. and Ghasemnejad, H. (2003) Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Some 3,5-Arylated 2-P yrazoli n es. Mole- cules, 8, 642-64 8. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/80800642 [81] Mi ch ael, C.J. and Den nis , M.P. (1988) Microwave Heating Apparatus for Laboratory Analyses. CEM Corporation. US Patent No. 4835354. [82] P r ice, W.H. and Earl, E.K. (1999) Pressure Vessel with Composite Sleeve. CEM Limited, L.L.C. US Patent No. 6534140. [83] Bernd, O., et al . (20 02 ) Device for Performing Safety Functions in Areas with High Frequency Radiation. Mikrowel- len-Labor-SystemeGmbh. US Patent No. 20020096340A1. [84] Edward, J.T., Pri ce, W.H. and Earl Edward, K. (1999) Pressure Sensing Reaction Vessel for Microwave Assisted Chemistry. CEM Corporation. US Patent No. 6124582. [85] P r ice, W.H. (1999 ) Sealing Closure for High-Pressure Vessels in Microwave Assisted Chemistry. CEM Corporation. US Patent No. 62 87526. [86] Stone-Elander, S. and Elander, N. (2002) Microwave Applications in Radiolabelling with Short-Lived Positron-Emitting Radionuclides. Journal of Labelled Compounds and Radiopharmaceuticals, 45, 715-746. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jlcr.593 [87] St adler, A., Yousefi, B.H., Dallinger, D., Walla, P., Van der Eycken, E., Kaval, N. and Kappe, C.O. (2003) Scalability of Micro wave-Assisted Organic Synthesis. F rom Single-Mode to Multimode Parallel Batch from Single-Mode to Mul- timode Parallel B atch Reacto r s . Organi c Pro ces s Research Devel opment, 7, 707-716. [88] Mo seley, J.D. and Kap pe, C.O. (2011) A Crit ical Assessment of th e Greenness an d Energy Efficiency of Micro wave- Assisted Organic Synthesis. Green Chemistry, 13, 794-806. http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/c0gc00823k [89] MILESTONES Inc. (2014) Digestion. http://www.milestonesci.com/digestion.php [90] MILESTONES Inc. (2014) Extraction. http://www.milestonesci.com/extraction.php  K. K. Rana, S. Rana OALibJ | DOI:10.4236/oalib.1100686 20 September 2014 | Volume 1 | [91] Developments in Microwave Chemistry (2005) Royal Society of Chemistry, Evalueserve, London, UK. [92] Kakita, Y. , Kashige, N., Murata, K. , Ku ro iwa, A., Funatsu, M. and Watan abe, K. (1995) Inactivation of Lactobacillus Bacterio phage PL-1 by Microwave Irradiation. Microbiology and Immunology, 39, 571-576. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1348-0421.1995.tb02244.x [93] Kakita, Y., Funatso, M., Miake, F . and Watanabe, K. (1999) Effects of Micro wave Irradiatio n on Bacteria Attached to the Hospiral White Coats. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health, 12, 123-12 6. [94] Sekhon, B.S. (2010) Microwave-Assisted Pharmaceutical Synthesis: An Overview. International Journal of Pharm- Tech Research, 2, 827-833. [95] Nüchter, M., Ondruschka, B., Bonrath, W. and Gum, A. (2004) Microwave Assisted Synthesis—A Critical Technology Overview. Green C hemistry, 6, 128-141. [96] Brett, A. and Christopher, R. (2005) Toward Rapid, “Green”, Predictable Microwave-Assisted Synthesis. Accounts of Chemical Research, 38, 653 -661. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ar040278m

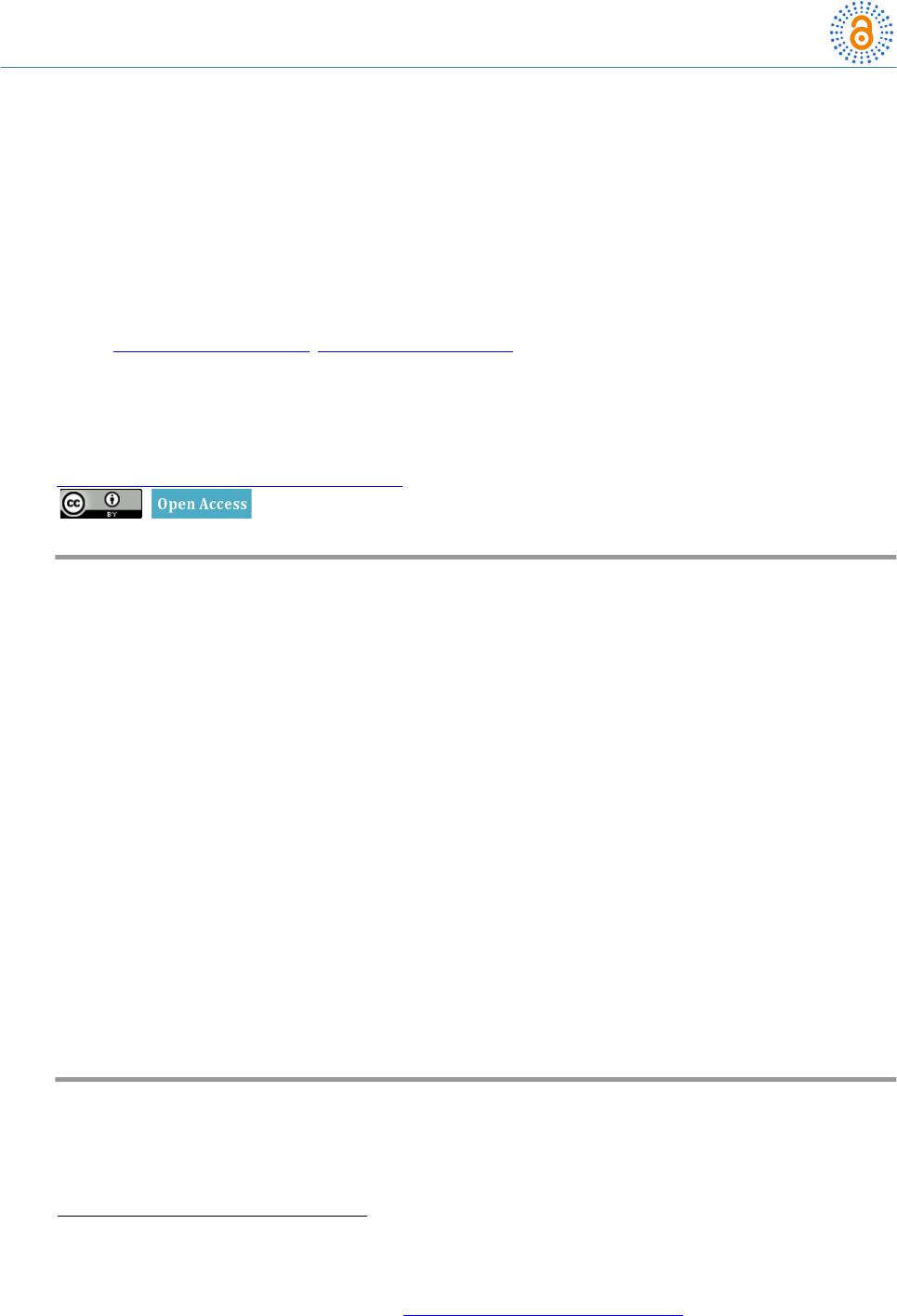

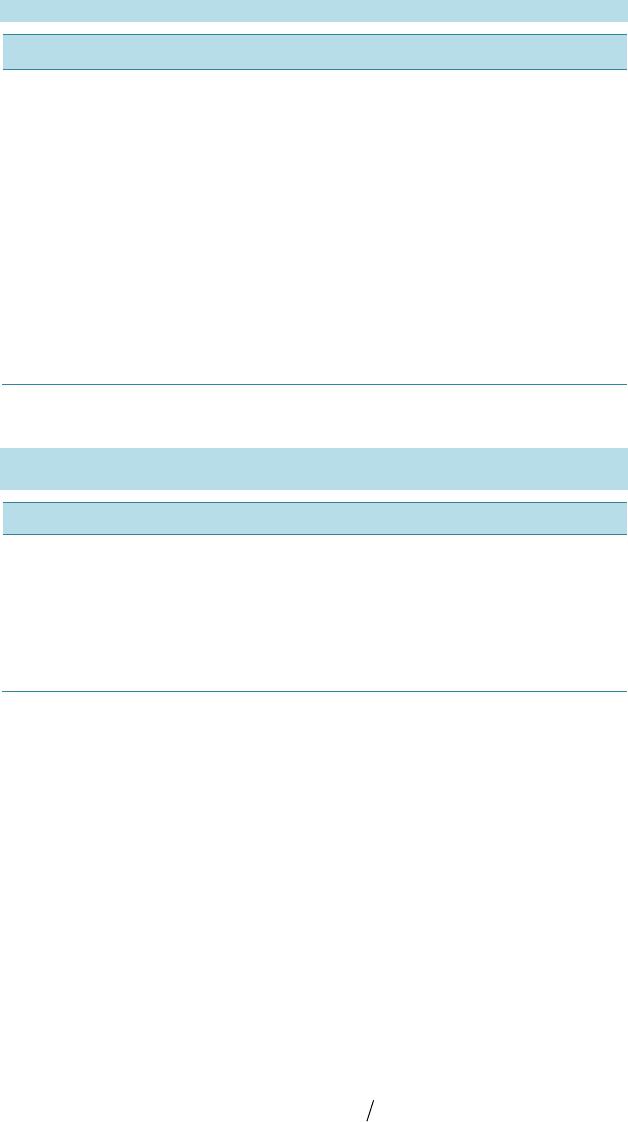

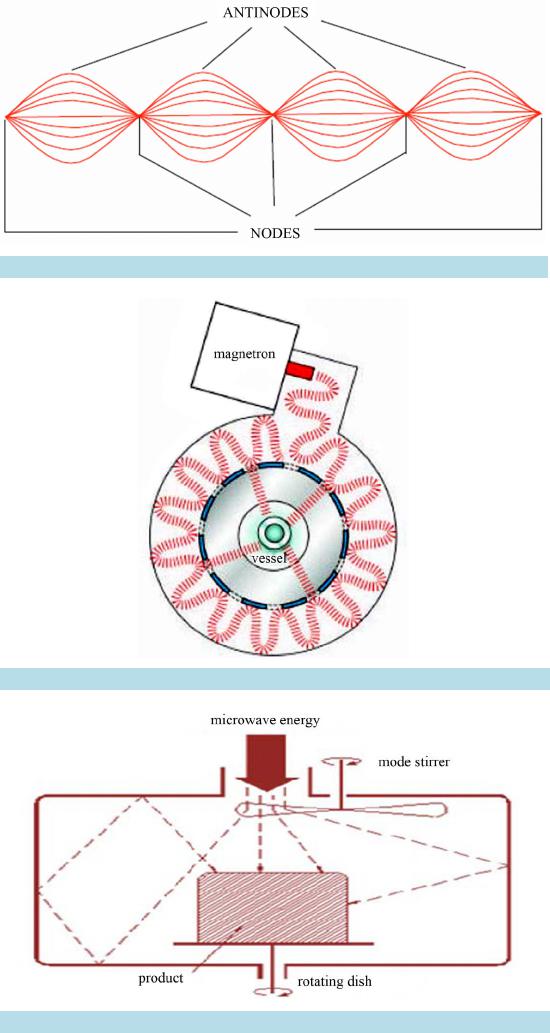

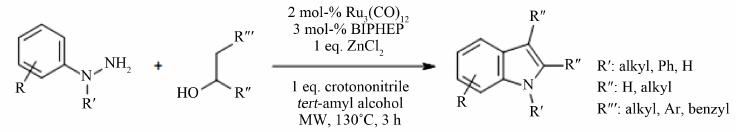

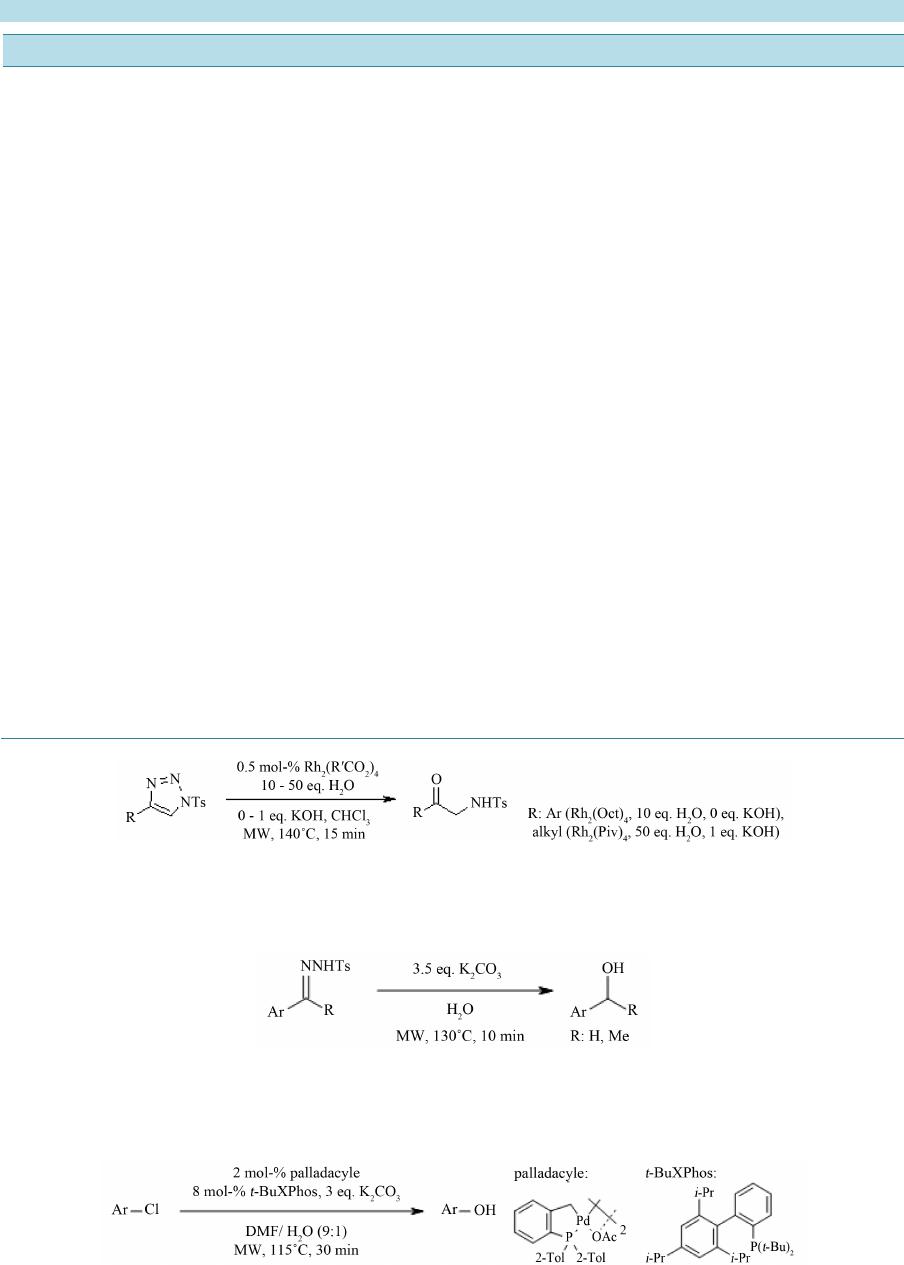

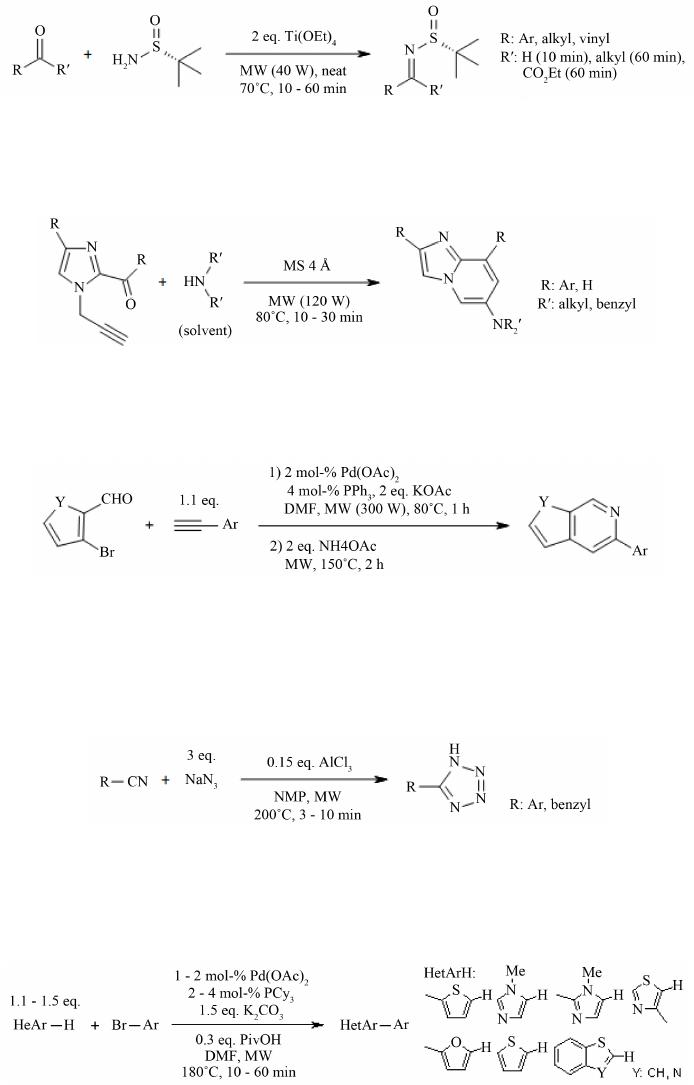

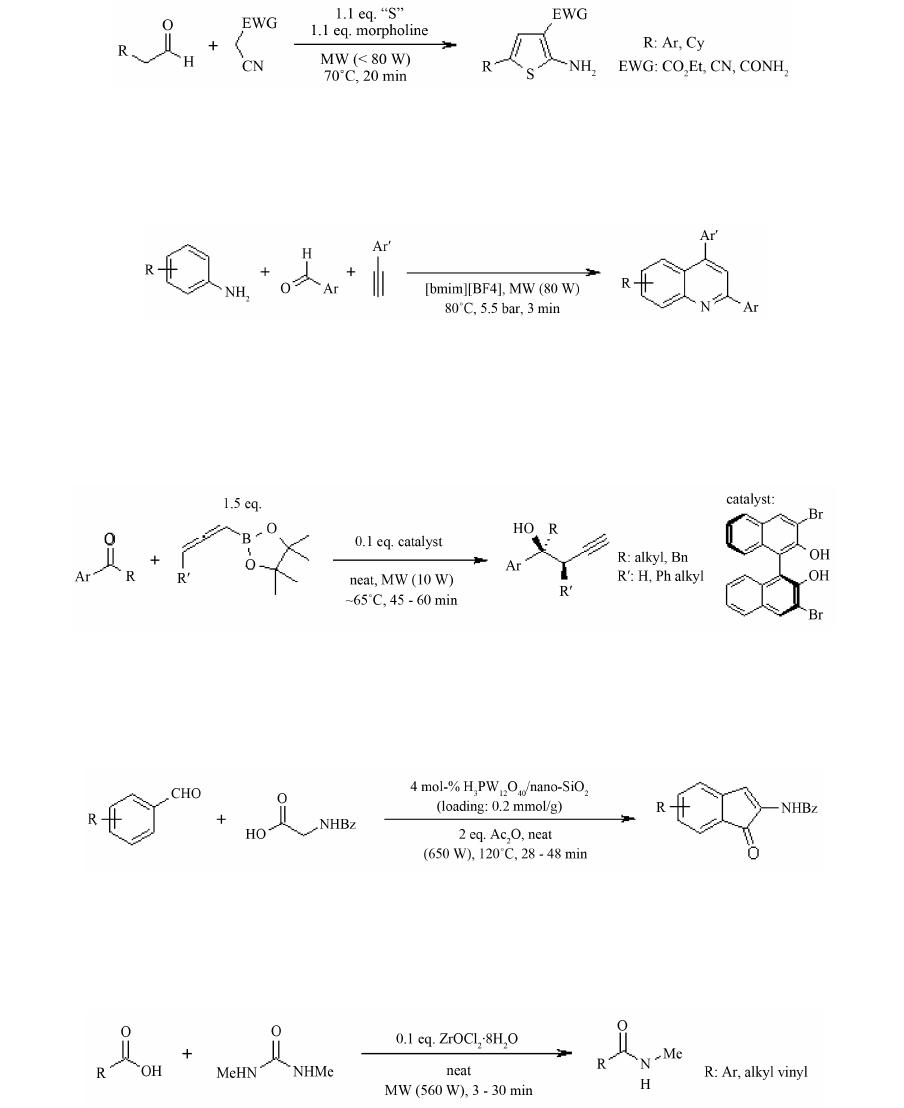

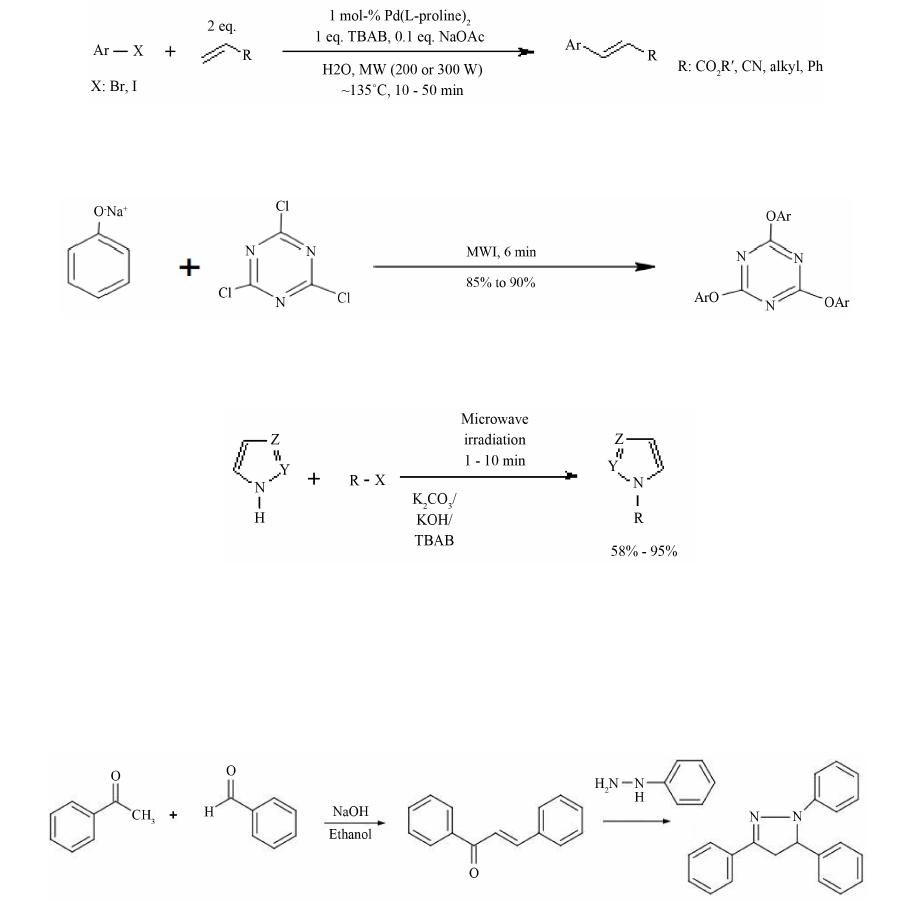

|