J. Biomedical Science and Engineering, 2011, 4, 483-489 doi:10.4236/jbise.2011.47061 Published Online July 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jbise/ JBiSE ). Published Online July 2011 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/JBiSE The clinical significance of CD97, NF-kB and COX-2 in gastric MALT lymphomas Shao-Liang Han*, Jun Cheng, Xiu-Ling Wu, Zeng-Rong Jia, Peng-Fei Wang, Zhan-Wei Wang Department of General Surgery, The First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical College, Wenzhou, China. Email: hanshaoliang99@gmail.com, slhan88@126.com Received 12 August 2010; revised 9 September 2010; accepted 20 October 2010. ABSTRACT Background and Objectives: Increased expression of the CD97, nuclear factor-kB (NF-kB) and cyclooxy- genase-2 (COX-2) has been found to play an impor- tant role in development of many cancers, including gastric neoplasm. However, the expression and bio- logical behavior of CD97, NF-kB and COX-2 in gas- tric MALT (mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue) lymphoma has not been well investigated. Methods: The expressions of CD97, COX-2 and NF-kB in 47 cases of gastric MALT lymphoma were detected im- munohistochemically, and the relevance between their expressions and the biological behavior was analyzed retrospectively. Results: 1) The expressions of CD97, NF-kB and COX-2 were 87.2%, 36.2% and 48.9%, respectively; 2) The difference of CD97 ex- pression between depth of invasion limited in mucosa and submucosa and beyond muscularis propria was significant (100.0% vs. 71.4%, P < 0.01). Moreover, the expression of nuclear CD97 between stage IIE, III, IV and stage I patients showed significant difference (96.4% vs. 73.7%, P < 0.05); 3) The expression of NF-kB was significantly correlated with tumor size, depth of invasion and stage; 4) The expression of COX-2 was significantly correlated with Helicobacter pylori infection, clinical stage, depth of invasion and tumor size (P < 0.05). Conclusions: Expressions of CD97, NF-κB and COX-2 were correlated with tumor invasion and metastasis in gastric MALT lym- phoma. Keywords: Stomach Neoplasm; CD97; Nuclear Factor-Kb (NF-Kb); Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2); Mu- cosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue (MALT) Lymphoma 1. INTRODUCTION Gastric mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma has recently been incorporated into the World Health Organization (WHO) lymphoma classification, termed as extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT-type [1,2]. Low grade gastric MALT lymphoma is a neoplasia with a very indolent course and an excel- lent prognosis, and it has a tendency to remain localized to the gastric wall and seldom involve lymph nodes and bone marrow [1-5]. As with other malignancies, the ac- cumulation of genetic abnormalities is required for ma- lignant transformation of human lymphocytes. CD97 is known as a leukocyte-restricted, cell surface glycoprotein expressed constitutively by human granu- locytes, monocytes, and, at low levels, resting T and B cells [6], and it regulates the expression of genes that are involved in inflammation, cell proliferation, and apop- tosis [7]. Recent studies suggest that CD97 expression correlates with tumor dedifferentiation, migration, and invasion in many tumors, such as thyroid, colorectal, and gastric cancer [8-15]. Furthermore, CD97 has features of a multifunctional protein that may play a role in signal transduction associated with the development or estab- lishment of the inflammatory processes [6,7]. However, CD97 has never been systemically investigated in gastric MALT lymphoma. Nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB), a transcription factor, plays an important role in carcinogenesis as well as in the regulation of immune and inflammatory responses, and it induces the expression of diverse target genes that promote cell proliferation, regulate apoptosis, facilitate angiogenesis and stimulate invasion and metastasis [16-25]. And the transcription factor NF-kB is a tightly regulated positive mediator of T- and B-cell develop- ment, proliferation, and survival [16-22,24,26-29]. Vari- ous molecular events lead to deregulation of NF-kB sig- naling in Hodgkin disease and a variety of T- and B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas either up-stream or down- stream of the central IkppaB kinase. These alterations are prerequisites for lymphoma cell cycling and block- age of apoptosis. Epidemiological and clinical studies demonstrated a link between gastric MALT lymphoma and chronic infection  S.-L. Han et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 4 (2011) 483-489 484 with Helicobacter pylori (H pylori) [30]. Cyclooxy- genase-2 (COX-2) is one of important enzymes that medi- ate inflammatory processes. In recent years, it has been demonstrated that both COX-2 play an important role in various tumors, including gastric lymphoma [3,31-36]. Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) is a key biosynthetic enzyme of COX enzyme family, which is the rate-limiting enzyme for prostaglandin H synthesis. It is an inducible enzyme, and normally absent in cells, but its expression is rapidly and transiently induced in response to growth factors, tu- mor promoters or cytokines, and it has an important role in the development and progression of various malignancies [31-34,36]. COX-2 has been studied in solid tumors; however, there is little data on the potential role of COX-2 in gastric MALT lymphoma pathogenesis. In this study, we conducted to determine the expressions of CD97, NF-kB and COX-2 with the clinicopathological data in 47 gastric MALT lymphomas and 10 adjacent mucosal specimens by using immunohistochemistry. 2. MATERIAL AND METHODS 2.1. Patients and Specimens A total of 47 Chinese patients with gastric MALT lym- phoma, who were treated surgically from January 1994 to May 2007 at the University Hospital of Wenzhou Medical College, participated in this study. All the patients were pathologically confirmed as low grade gastric MALT lymphoma. The diagnosis of low grade gastric MALT lymphoma was made according to the criteria of Isaacson [1,2], which are composed of centrocyte-like cells, lym- phoid follicles and plasma cell differentiation, and scoring system of Wotherspoon et al. [5], and the stains of immu- nohistochemical markers, such as leukocyte common an- tigen (LCA), L26, CD5 and CD10 was performed. The initial staging procedures included a complex physical examination, chest roentgenogram, bone marrow examina- tion, abdominal CT scan and endoscopy. Normal gastric mucosal samples were located at least 8 cm from the mar- gin of the tumors of surgical specimens. The average age was 56.4 years, ranging from 32 years to 81years, and the ratio of male to female was 30 to 17. 2.2. Immunohistochemistry The expressions of CD97, NF-kB and COX-2 were stud- ied by immunohistochemicl Envision method according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Briefly, all the tissue specimens were preserved with 10% v/v formalin and embedded in paraffin. Sections (5-μm-thick) were cut, placed on glass slides, and depaffinized. One section from each block was stained with hematoxylin-eosin for evaluating the diagnosis of gastric MALT lymphoma. After depaffinization and dehydration, the tissue sections were subjected to microwave oven treatment in 0.01 mol/L sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 8 minutes at 600W and then exposed to 0.3% H2O2 for 30 minutes to block endogenous peroxidase. After washing with PBS, sections were incubated in PBS supplemented with 10% goat serum for 20 min at room temperature to block non-specific binding of secondary antibody, then incu- bated overnight at 4˚C with CD97 (1:50), NF-kB (1:100) and COX-2 (1:50) in PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin. After rinsing three times in PBS, sections were treated with biotinylated anti-immunoglobulin for 1h at room temperature, then washed again and reacted with the streptavidinbiotin system by using 0.04% 3, 3’-dia- minobenzidine tetrahydrochloride for1min as chromogen. Negative control was established by replacing the pri- mary antibody with PBS. The primary antibody of rabbit polyclonal CD97 (ab13345) was purchased from Cambridge Science Park (Abcam plc332, Cambridge, UK), monoclonal mouse anti-human NF-kB oncoprotein were purchased from Beijing Zhongshan Godden Bridge Biotechnology Co. LTD., and rabbit polyclonal anti-human COX-2 IgG from (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). 2.3. Evaluation of Immunohistochemical Staining Immunoreactivity was scored semiquantitatively by two independent investigators who were unaware of the his- tological results using a light microscope in the terms of proportion of cells in gastric MALT lymphoma tissues. The criteria for grade referenced to the report of Wu et al. [37]: grade 0, stained cells accounted for less than 10%; grade 1, between 10% and 29%; grade 2, between 30% and 49%; and grade 3, more than 50%. Grades 1 through 3 were considered positive. And the level of staining intensity was estimated to grades between 0 and 3 (0, negative; 1, weak; 2, moderate; 3, strong staining). CD97-positive tumors were further examined for the presence of more strongly stained scattered cells or scat- tered cell groups near or on the invasion front. 2.4. Statistical Analysis Statistical analysis was performed with SSPS 13.0; the parameters were compared with the χ2 test. Spearman cor- relation test was used for the correlation between positive rates. A level of P 0.05 was considered significant. 3. RESULTS 3.1. CD97 Protein Expression Correlates with Clinicopathological Variables Forty-one of 47 gastric MALT lymphoma tissues showed CD97 positive staining, including 8 weak, 15 moderate and 18 strong staining (Figure 1(a)). All three cases with large cell differentiation stained strongly, C opyright © 2011 SciRes. JBiSE  S.-L. Han et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 4 (2011) 483-489 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. 485 whereas, in normal gastric mucosa tissue, no immuno- reactivity of CD97 was found. The relationship between CD97 protein expression and a number of clinical in- dexes, including depth of tumor invasion and clinical staging, as well as patient’s age and sex, tumor size, and H pylori infection, were also investigated and summa- rized in Table 1. The difference of CD97 expression between depth of invasion limited in mucosa and sub- mucosa and beyond muscularis propria was significant (100.0%, 26/26 vs. 71.4%, 15/21, P < 0.01). Moreover, the expression of nuclear CD97 between stage IIE, III, IV and stage I patients showed significant difference (27 of 28, 96.4% vs. 14 of 19, 73.7%, P < 0.05), but not with the age and gender of patients, H pylori infection, and tumor size (P > 0.05, Table 1). JBiSE There was no correlation between CD97 and NK-kB (r = 0.243, P = 1.00) or COX-2 expression (r = 0.263, P = 0.74). 3.2. NF-kB Protein Expression Correlates with Clinicopathological Variables In this study, no immunoreactivity of NF-kB was found in all normal gastric mucosa tissues, the positive expres- sion of NF-kB protein (Figure 1(b)) in the patients with gastric MALT lymphoma was 36.2% (17/47), moreover, tumors with low expression of NF-kB were significantly smaller in size (17 of 47, 36.2%, P < 0.05) than those with high expression (9 of 21, 42.8% and 5 of 7, 71.4%). The incidence of deeper invasion was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than that in tumor with low expression (13 of 26, 50% vs. 4 of 21, 26.7%). Furthermore, the expression of nuclear NF-kB between stage IIE, IV and stage I and stage II patients showed significant differ- ence(16 of 19, 84.2% vs. 4 of 19, 21.1% vs. 4 of 15, 26.7%, P < 0.05).Whereas, not with the age and gender of patients, or H pylori infection (P > 0.05, Table 1). 3.3. COX-2 Protein Expression Correlates with Clinicopathological Variables Twenty-three of 47 gastric MALT lymphoma tissues showed COX-2 positive staining, immunohistochemi- cally, COX-2 was stained diffusely in cytoplasm of the tumor cells (Figure 1(c)). In contrast, no or very faint signal was found in neighboring normal tissues. The expression of COX-2 gastric MALT lymphoma patients with H pylori infection was significantly higher than those in patients without H pylori infection (19 of 29, 65.5% vs. 4 of 18, 22.2%) (P<0.05), moreover, COX-2 expression was significantly correlated with clinical stage, depth of invasion, tumor size (P<0.05). Univariate factor analysis showed that the overall survival of gastric MALT lymphoma patients with positive COX-2 protein Figure 1. (a) Strong immunohistological stain of CD97 in gastric MALT lymphoma (original magnification × 200). (b) The gastric MALT lymphoma stained NF-kB nuclear immunity (original magnification × 200). (c) Strong immunohistological stain of COX-2 in gastric MALT lymphoma (original magnification × 200).  S.-L. Han et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 4 (2011) 483-489 486 Table 1. The relationship between CD97, NF-kB and COX-2 positive expression and the clinico- pathological factors in gastric MALT lymphoma. Clinicopathological factors CD97 positive expression (%) NF-kB positive nuclear expression (%) COX-2 expression (%) Age >60year (n = 20) ≤60year (n = 27) 18 (90.0%) 23 (85.2%) 11 (55.0%) 10 (43.5%) 10 (50.0%) 13 (48.1%) Sex male (n = 30) female (n = 17) 26 (86.7%) 15 (88.2%) 13 (50.0%) 8 (53.3%) 14 (46.7%) 9 (52.9%) H pylori infection yes (n = 29) no (n = 18) 24 (82.8%) 17 (94.4%) 10 (41.7%) 7 (29.9%) 10 (34.5%) ** 14 (77.8%) Tumor size ≤5 cm (n =19) 5 - 10 cm (n = 21) >10 cm (n = 7) 14 (73.7%) 20 (95.2%) 7 (100.0%) 3 (15.7%) 9 (42.8%)* 5 (71.4%) ** 14 (73.7%)* 10 (35.7%) Depth of invasion m + sm (n = 21) pm + s (n = 26) 15 (71.4%) ** 26 (100.0%) 4 (19.0%)* 13 (50.0%) 15 (71.4%)* 9 (34.6%) Staging stage I (n = 19) stage II (n = 15) stage IIE + IV (n = 13) 14 (73.7%)* 14 (93.3%) 13 (100.0%) 4 (21.1%)* 4 (26.7%)* 9 (69.2%) 12 (63.2%)* 9 (60.0%) 2 (15.4%) Tumor recurrence yes (n = 4) no (n = 43) 3 (75.0%) 38 (88.4%) 3 (33.3%) 14 (36.8%) 5 (29.4%)* 19 (63.3%) Note: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 (59.9 months) was shorter than that of patients with negative COX-2 protein (77.8 months), but this differ- ence was no statistically significant (P > 0.05). There was a significant correlation between COX-2 and NK-kB expression (r = 0.442, P = 0.02). 4. DISCUSSION Normal human gastric mucosa is devoid of MALT, and MALT accumulates within gastric mucosa as a result of long-standing H pylori infection in a subset of infected patients, and from this acquired MALT, low-grade B cell MALT lymphoma may eventually develop [1-3,5]. H pylori can be demonstrated in the gastric mucosa of the majority of cases of gastric MALT lymphoma [23,30]. Additionally, eradication of H pylori was reported to result in the complete regression of the majority of these tumors [5,38]. However, the exact mechanism responsi- ble for the development of MALT lymphoma still re- mains obscure. It has been showed that expression of CD97 was found in various epithelial tumours, for example, thyroid, colorectal, gastric, oesophageal and pancreatic carcino- mas [30-36,39]. A study from Steinert et al. [14] sug- gests a strong correlation between the appearance of moderate of severe tumor budding and accumulating of CD97 in these scattered tumor cells. Recent studies sug- gest that molecule CD97 are contributing to cell-matrix and cell to cell interactions and identify a subset of car- cinoma cells prone to invade focally, spread, and metas- tasis in colorectal cancer [10,12]. In addition, the level of CD97 in cancer cell line correlates with migration and invasion in vitro, and this result was confirmed in CD97-inducible Tet-off HT1080 cells [14]. However, there is no data on CD97 expression in MALT lym- phoma. Our observation for the first time demonstrated that CD97 protein was strongly expressed in 87.2% gas- tric MALT lymphoma tissues, moreover, CD97 protein was diffusely expressed in the gastric MALT lymphoma tissues, and very highly expressed in the tumor with large cell differentiation, but it remarkably differed from the characteristics of CD97 in gastric or colorectal can- cer tissues [12,14]. Moreover, our data showed that CD97 protein expression was inversely correlated with tumor size, depth of invasion and clinical staging in gas- tric MALT lymphoma (P < 0.01 or 0.05), namely, the immunoassaying of CD97 in gastric MALT lymphoma suggests that CD97 expression may play an important role in the development and aggressiveness of gastric MALT lymphoma. NF-kB is a family of important transcription factors that regulate B-cell development, maintenance, and stimulation [19,20,23,25] ;it is constitutively present in the cytosol and inactivated by its association with IkB family inhibitors [17,22]. B-cell receptor signaling and some tumor necrosis factor (TNF) cytokine signaling induce NF-kB activation through the NF-kB1 pathway [24], where phosphorylation of the NF-kB inhibitor IkB by the IkB kinase (IKK) complex allows the cytoplasmic C opyright © 2011 SciRes. JBiSE  S.-L. Han et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 4 (2011) 483-489 487 NF-kB proteins p65 and p50 to translocate to the nucleus when their nuclear localization sequence (NLS) is ex- posed. Once phosphorylated, IkB is targeted for ubiquit- ination and degradation by the 26S proteasome, allowing translocation of NF-kB into the nucleus where it binds to specific DNA sequences in the promoters of target genes, thereby stimulating transcription [16,21]. Recently, ge- netic and biochemical evidence has accumulated, sug- gesting that constitutive activation of NF-kB proteins plays an important role in the development/progression of B and T cell lymphoid malignancies [19,22,29]. In particular, genetic and molecular alterations of NF-kB family members and their transcriptional target genes have been implicated in the development of diffuse large B cell lymphoma and mucosa-associated lymphoid tis- sue lymphoma. Various molecular events lead to de- regulation of NF-kB signaling in Hodgkin disease and a variety of T- and B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas either up-stream or downstream of the central IkappaB kinase. Although NF-kB proteins represent an integrating point of several pathways, potentially contributing to several diseases, their unique activation depends on cell type and stimulus [26,28]. H pylori activate the alternative NF-kB pathway in B lymphocytes. The effects on chemokine production and antiapoptosis mediated by H. pylori-induced processing of NF-kB2/p100 to p52 may drive lymphocytes to ac- quire malignant potential [10]. Merzianu M et al. [27] reported that nuclear expression of the p65 subunit of NF-kB in lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma was 34%, sug- gesting that NF-kB is active in these tumors. In this study, expression of NF-kB was examined in gastric MALT lymphoma, and found NF-kB nuclear expression was inversely correlated with tumor volume, depth of tumor invasion and clinical staging in gastric MALT lymphoma. These results suggest that nuclear expression of NF-kB involve in the tumorogenesis and development of gastric MALT lymphoma and inhibition of NF-kB pathway may be an alternative for prevention and treat- ment of this disease. Cyclooxgenases (COXs) are the key enzymes in ara- chidonate metabolism and catalyze the biosynthesis of prostaglandin H2, which is the precursor for prostanoids. There are at least two isoformers, COX-1 and COX-2, the former, which is constitutively expressed in many tissues, and involved in the homeostasis of various physiologic functions, and the latter, which is involved in many inflammatory reactions with its expression rap- idly induced by growth factors, tumor promoters or cy- tokines [30,33]. Under normal conditions, COX-2 is absent in tissue cells. Over-expression of COX-2 in ade- nocarcinoma cells has also been linked to increased an- giogenesis and metastasis [32-34]. COX-2 can be regu- lated at both transcriptional and posttranscriptional lev- els [33]. The transcriptional activation of COX-2 is me- diated by the binding of inducible transcriptional factors to cis-acting elements in the COX-2 promoter. Binding sites for the regulatory elements, including NF-kB, nu- clear factor for interleukin-6 (NF-IL-6), cyclic AMP response element (CRE), PEA-3, SP-1, activator pro- tein-2 (AP-2), and T-cell factor 4 (TCF-4), have been identified in the 5’-flanking region of the COX-2 gene [19,20,29]. COX-2 has been found to be overexpressed in various B-cell lymphoma cell lines [32,34,36,40]. With respect to lymphoma, Paydas et al.’s study sug- gested that there was an important association between aggressive histology and COX-2 expression: COX-2 was negative in about half of the cases with indolent mor- phology, while two thirds of the COX-2 positive cases had aggressive histology (P = 0.036) [32]. Furthermore, though the difference was not significant statistically, the overall survival of COX-2-positive patients was less than for those without COX-2 expression [31]. Our study showed COX-2 positive staining, and the expres- sion of COX-2 gastric MALT lymphoma patients with H pylori infection was significantly higher than those in patients without H pylori infection (P < 0.05), moreover, COX-2 expression was significantly correlated with clinical stage, depth of invasion, tumor size in gastric MALT lymphoma(P < 0.05), and gastric MALT lym- phoma patients with positive COX-2 protein lived shorter than patients with negative COX-2 protein (P > 0.05) in univariate factor analysis. This is in agreement with the report of Yang et al. [41], the COX-2 expression correlated with clinical stage and COX-2 negative pa- tients had lower survival than COX-2 positive patients (p = 0.014). Lymphoma cells treated with COX-2 inhibitor (celecoxib) revealed apoptotic induction of greater than 85% in all cell lines examined at 50 microM celecoxib, these findings suggest that increased COX-2 expression and activity, contributes to the pathogenesis of B cell lymphomas and point to a possible role for COX-2 inhi- bition in their treatment [34]. These findings suggest that increased COX-2 expression and activity, contributes to the pathogenesis of gastric MALT lymphomas and point to a possible role for COX-2 inhibition in their treat- ment. COX-2 over-expression parallels NF-kB expression in oral precancer and cancer[40], and synchronism between individual expressions may denote a regulatory role of the latter in COX-2 tansactivation[41]. Our results indi- cate that there was a significant correlation between COX-2 and NK-kB Expression (r = 0.02, P < 0.05), but no correlation was found between CD97 and NK-kB (r = 1.00, P > 0.05) or COX-2 expression (r = 0.74, P > 0.05). Taken together, our findings was the first to indicate C opyright © 2011 SciRes. JBiSE  S.-L. Han et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 4 (2011) 483-489 488 that CD97 strongly expressed in gastric MALT lym- phoma tissues, and expressions of CD97, NF-kB and COX-2 may play a synergistic role in the pathogenesis of gastric MALT lymphoma, moreover, their expressions were correlated with tumor invasion and metastasis. REFERENCES [1] Isaacson, P. and Wright, D.H. (1983) Malignant lym- phoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. A distinc- tive type of B-cell lymphoma. Cancer, 52, 1410-1416. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19831015)52:8<1410::AID-CN CR2820520813>3.0.CO;2-3 [2] Isaacson, P.G. (2005) Update on MALT lymphomas. Best Practice & Research Clinical Haematology, 18, 57-68. doi:10.1016/j.beha.2004.08.003 [3] Gascoyne, R.D. (2003) Molecular pathogenesis of mu- cosal-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma. Leukemia & Lymphoma, 44, S13-20. doi:10.1080/10428190310001623793 [4] Harris, N.L., Jaffe, E.S., Diebold, J., et al. (1999) World Health Organization classification of neoplastic diseases of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: Report of the Clinical Advisory Committee meeting-Airlie House, Vir- ginia, November 1997. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 17, 3835-3849. [5] Wotherspoon, A.C., Ortiz-Hidalgo, C., Falzon, M.R. and Isaacson, P.G. (1991) Helicobacter pylori-associated gas- tritis and primary B-cell gastric lymphoma. Lancet, 338, 1175-1176. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(91)92035-Z [6] Jaspars, L.H., Vos, W., Aust, G., et al. (2001) Tissue dis- tribution of the human CD97 EGF-TM7 receptor. Tissue Antigens, 57, 325-331. doi:10.1034/j.1399-0039.2001.057004325.x [7] Wang, T., Ward, Y., Tian, L., et al. (2005) CD97, an ad- hesion receptor on inflammatory cells, stimulates angio- genesis through binding integrin counterreceptors on en- dothelial cells. Blood, 105, 2836-2844. doi:10.1182/blood-2004-07-2878 [8] Aust, G., Eichler, W., Laue, S., et al. (1997) CD97: A dedifferentiation marker in human thyroid carcinomas. Cancer Research, 57, 1798-1806. [9] Aust, G., Steinert, M., Schutz, A., et al. (2002) CD97, but not its closely related EGF-TM7 family member EMR2, is expressed on gastric, pancreatic, and esophageal car- cinomas. American Journal of Clinical Pathology, 118, 699-707. doi:10.1309/A6AB-VF3F-7M88-C0EJ [10] Galle, J., Sittig, D., Hanisch, I., et al. (2006) Individual cell-based models of tumor-environment interactions: Multiple effects of CD97 on tumor invasion. American Journal of Pathology, 169, 1802-1811. doi:10.2353/ajpath.2006.060006 [11] Hoang-Vu, C., Bull, K., Schwarz, I., et al. (1999) Regu- lation of CD97 protein in thyroid carcinoma. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 84, 1104-1109. doi:10.1210/jc.84.3.1104 [12] Liu, Y., Chen, L., Peng, S.Y., et al. (2005) Role of CD97(stalk) and CD55 as molecular markers for progno- sis and therapy of gastric carcinoma patients. Journal of Zhejiang University Science B, 6, 913-918. doi:10.1631/jzus.2005.B0913 [13] Mustafa T, Klonisch T, Hombach-Klonisch S, et al.: Ex- pression of CD97 and CD55 in human medullary thyroid carcinomas. Int J Oncol 2004;24:285-294. [14] Steinert, M., Wobus, M., Boltze, C., et al. (2002) Expres- sion and regulation of CD97 in colorectal carcinoma cell lines and tumor tissues. American Journal of Pathology, 161, 1657-1667. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64443-4 [15] Wobus, M., Huber, O., Hamann, J. and Aust, G. (2006) CD97 overexpression in tumor cells at the invasion front in colorectal cancer (CC) is independently regulated of the canonical Wnt pathway. Molecular Carcinogenesis, 45, 881-886. doi:10.1002/mc.20262 [16] Claudio, E., Brown, K., Park, S., et al. (2002) BAFF-induced NEMO-independent processing of NF-kappa B2 in maturing B cells. Nature Immunology, 3, 958-965. doi:10.1038/ni842 [17] Fu, L., Lin-Lee, Y.C., Pham, L.V., et al. (2006) Constitu- tive NF-kappaB and NFAT activation leads to stimulation of the BLyS survival pathway in aggressive B-cell lym- phomas. Blood, 107, 4540-4548. doi:10.1182/blood-2005-10-4042 [18] Hinz, M., Lemke, P., Anagnostopoulos, I., et al. (2002) Nuclear factor kappaB-dependent gene expression pro- filing of Hodgkin’s disease tumor cells, pathogenetic sig- nificance, and link to constitutive signal transducer and activator of transcription 5a activity. Journal of Experi- mental Medicine, 196, 605-617. doi:10.1084/jem.20020062 [19] Hosokawa, Y. and Seto, M. (2004) Nuclear factor kap- paB activation and antiapoptosis in mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. International Journal of Hematology, 80, 215-223. doi:10.1532/IJH97.04101 [20] Jost, P.J. and Ruland, J. (2007) Aberrant NF-kappaB signaling in lymphoma: Mechanisms, consequences, and therapeutic implications. Blood, 109, 2700-2707. [21] Kaisho, T., Takeda, K., Tsujimura, T., et al. (2001) Ikap- paB kinase alpha is essential for mature B cell develop- ment and function. Journal of Experimental Medicine, 193, 417-426. doi:10.1084/jem.193.4.417 [22] Karin, M. and Ben-Neriah, Y. (2000) Phosphorylation meets ubiquitination: The control of NF-[kappa]B activ- ity. Annual Review of Immunology, 18, 621-663. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.621 [23] Ohmae, T., Hirata, Y., Maeda, S., et al. (2005) Helico- bacter pylori activates NF-kappaB via the alternative pathway in B lymphocytes. Journal of Immunology, 175, 7162-7169. [24] Senftleben, U., Cao, Y., Xiao, G., et al. (2001) Activation by IKKalpha of a second, evolutionary conserved, NF-kappa B signaling pathway. Science, 293, 1495-1499. doi:10.1126/science.1062677 [25] Souvannavong, V., Saidji, N. and Chaby, R. (2007) Lipopolysaccharide from Salmonella enterica activates NF-kappaB through both classical and alternative path- ways in primary B Lymphocytes. Infection and Immunity, 75, 4998-5003. doi:10.1128/IAI.00545-07 [26] Kim, H.J., Hawke, N. and Baldwin, A.S. (2006) NF-kappaB and IKK as therapeutic targets in cancer. Cell Death & Differentiation, 13, 738-747. doi:10.1038/sj.cdd.4401877 [27] Merzianu, M., Jiang, L., Lin, P., et al. (2006) Nuclear C opyright © 2011 SciRes. JBiSE  S.-L. Han et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 4 (2011) 483-489 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. 489 JBiSE BCL-10 expression is common in lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma/Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia and does not correlate with p65 NF-kappaB activation. Modern Pathology, 19, 891-898. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3800609 [28] Pham, L.V., Tamayo, A.T., Yoshimura, L.C., et al. (2003) Inhibition of constitutive NF-kappa B activation in man- tle cell lymphoma B cells leads to induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Journal of Immunology, 171, 88-95. [29] Stoffel, A. (2005) The NF-kappaB signalling pathway: A therapeutic target in lymphoid malignancies? Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets, 9, 1045-1061. doi:10.1517/14728222.9.5.1045 [30] Konturek, P.C., Konturek, S.J., Pierzchalski, P., et al. (2001) Cancerogenesis in Helicobacter pylori infected stomach—Role of growth factors, apoptosis and cyclooxygenases. Medical Science Monitor, 7, 1092- 1107. [31] Hazar, B., Ergin, M., Seyrek, E., et al. (2004) Cyclooxy- genase-2 (Cox-2) expression in lymphomas. Leukemia and Lymphoma, 45, 1395-1399. doi:10.1080/10428190310001654032 [32] Paydas, S., Ergin, M., Erdogan, S. and Seydaoglu, G. (2007) Cyclooxygenase-2 expression in non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Leukemia and Lymphoma, 48, 389-395. doi:10.1080/10428190601059787 [33] Phipps, R.P., Ryan, E. and Bernstein, S.H. (2004) Inhibi- tion of cyclooxygenase-2: A new targeted therapy for B-cell lymphoma? Leukemia Research, 28, 109-111. doi:10.1016/S0145-2126(03)00260-1 [34] Wun, T., McKnight, H., Tuscano, J.M. (2004) Increased cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2): A potential role in the pathogenesis of lymphoma. Leukemia Research, 28, 179-190. doi:10.1016/S0145-2126(03)00183-8 [35] Yamamoto, S., Yamamoto, K., Kurobe, H., et al. (1998) Transcriptional regulation of fatty acid cyclooxy- genases-1 and -2. International Journal of Tissue Reac- tions, 20, 17-22. [36] Yang, H., Zuo, X., Zhang, K., et al. (2006) Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and proliferating cell nuclear antigen in gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. World Chinese Journal of Digestology, 12, 1178-1182. [37] Wu, X., Han, S., Wan, L., et al. (2007) BCL10 and NF-kB are prognostic factors in gastric MALT lympho- mas. Chinese Journal of General Surgery, 22,172-175. [38] Park, S.W., Sung, M.W., Heo, D.S., et al. (2005) Nitric oxide upregulates the cyclooxygenase-2 expression through the cAMP-response element in its promoter in several cancer cell lines. Oncogene, 24, 6689-6698. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1208816 [39] Wotherspoon, A.C., Doglioni, C., Diss, T.C., et al. (1993) Regression of primary low-grade B-cell gastric lym- phoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Lancet, 342, 575-577. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(93)91409-F [40] Sawhney, M., Rohatgi, N., Kaur, J., et al. (2007) Expres- sion of NF-kappaB parallels COX-2 expression in oral precancer and cancer: Association with smokeless to- bacco. International Journal of Cancer, 120, 2545-2556. doi:10.1002/ijc.22657 [41] Yang, G.Z., Li, L., Ding, H.Y., Zhou, J.S. (2005) Cyclooxygenase-2 is over-expressed in Chinese eso- phageal squamous cell carcinoma, and correlated with NF-kappaB: An immunohistochemical study. Experi- mental and Molecular Pathology, 79, 214-218. doi:10.1016/j.yexmp.2005.09.002

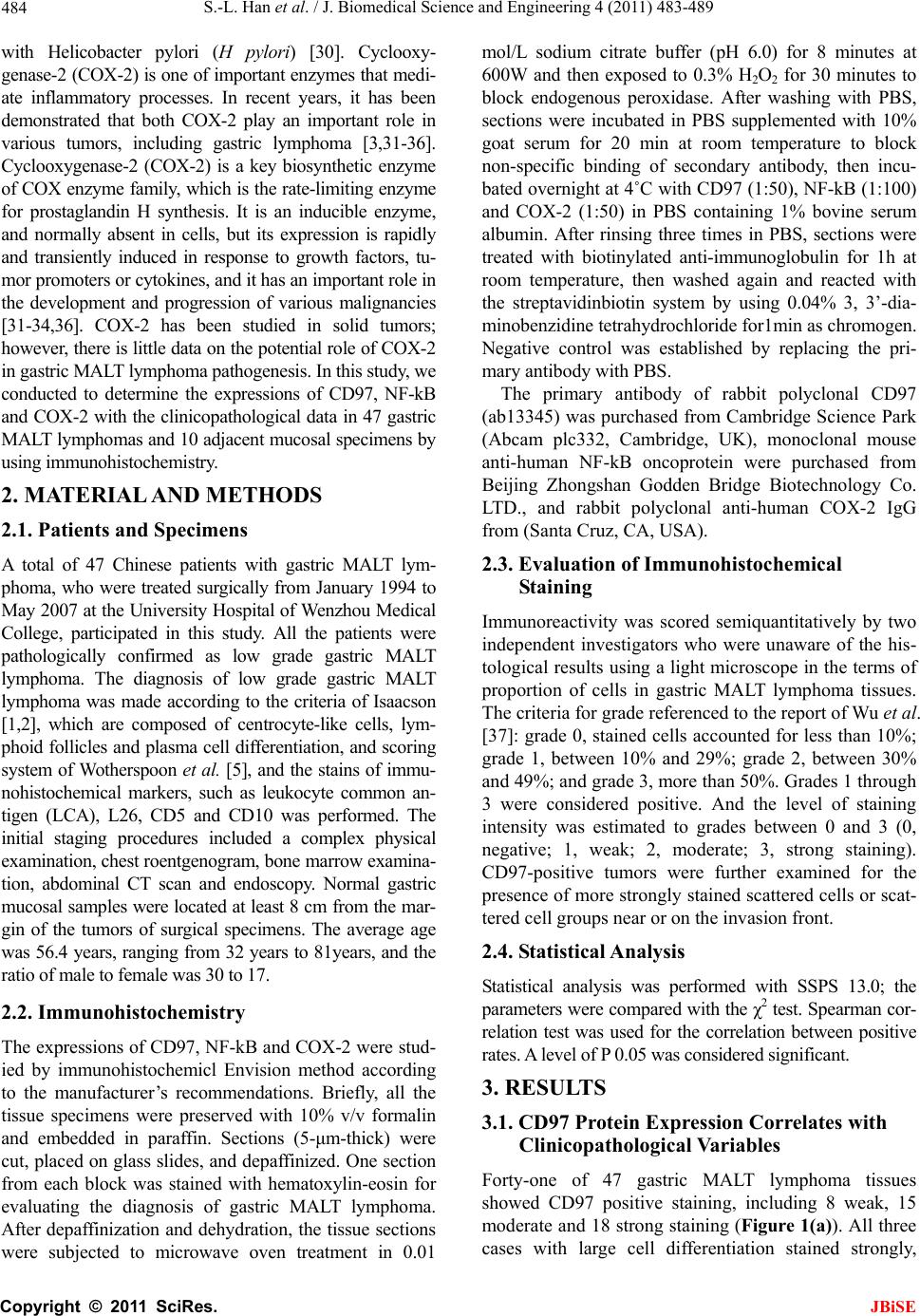

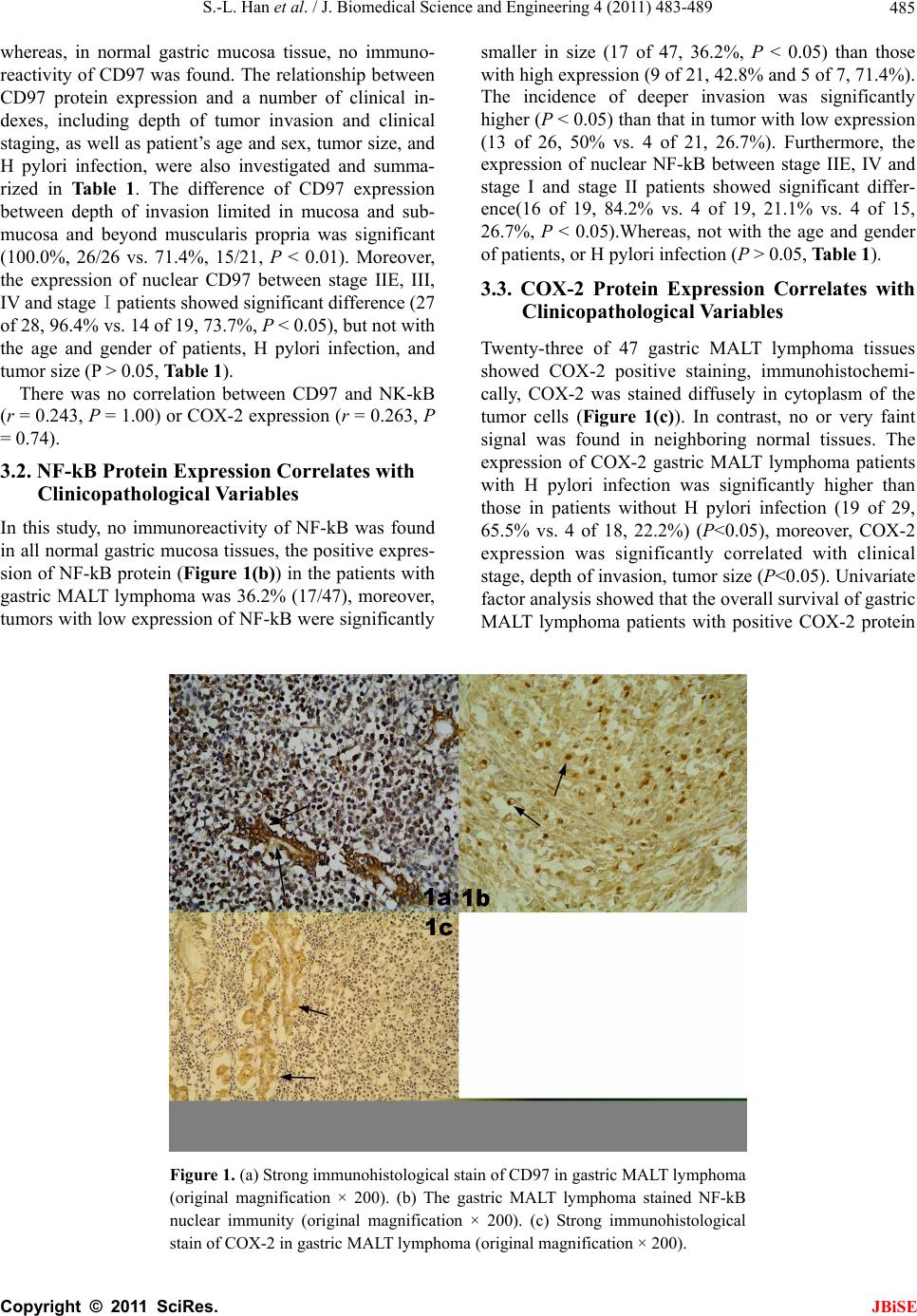

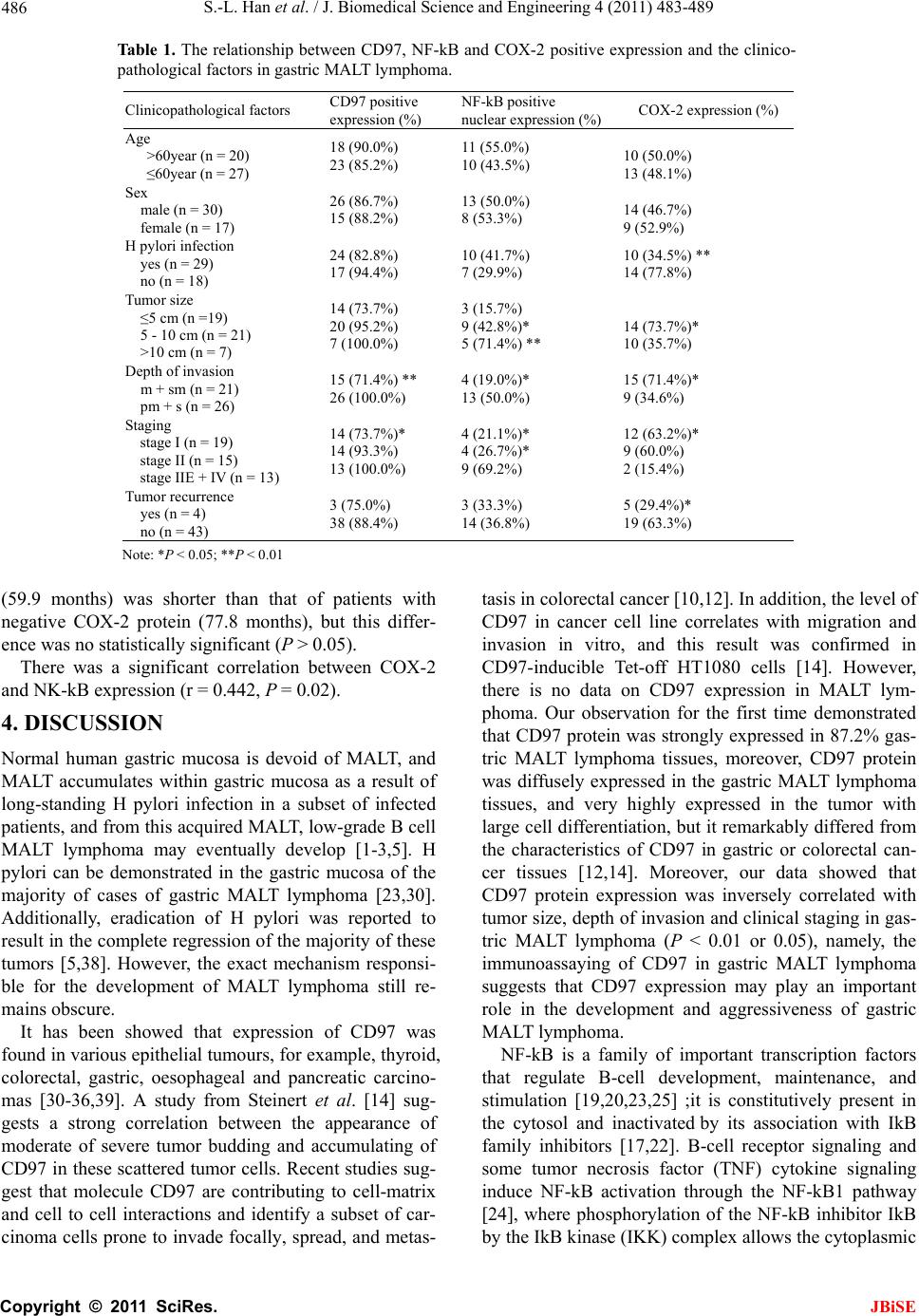

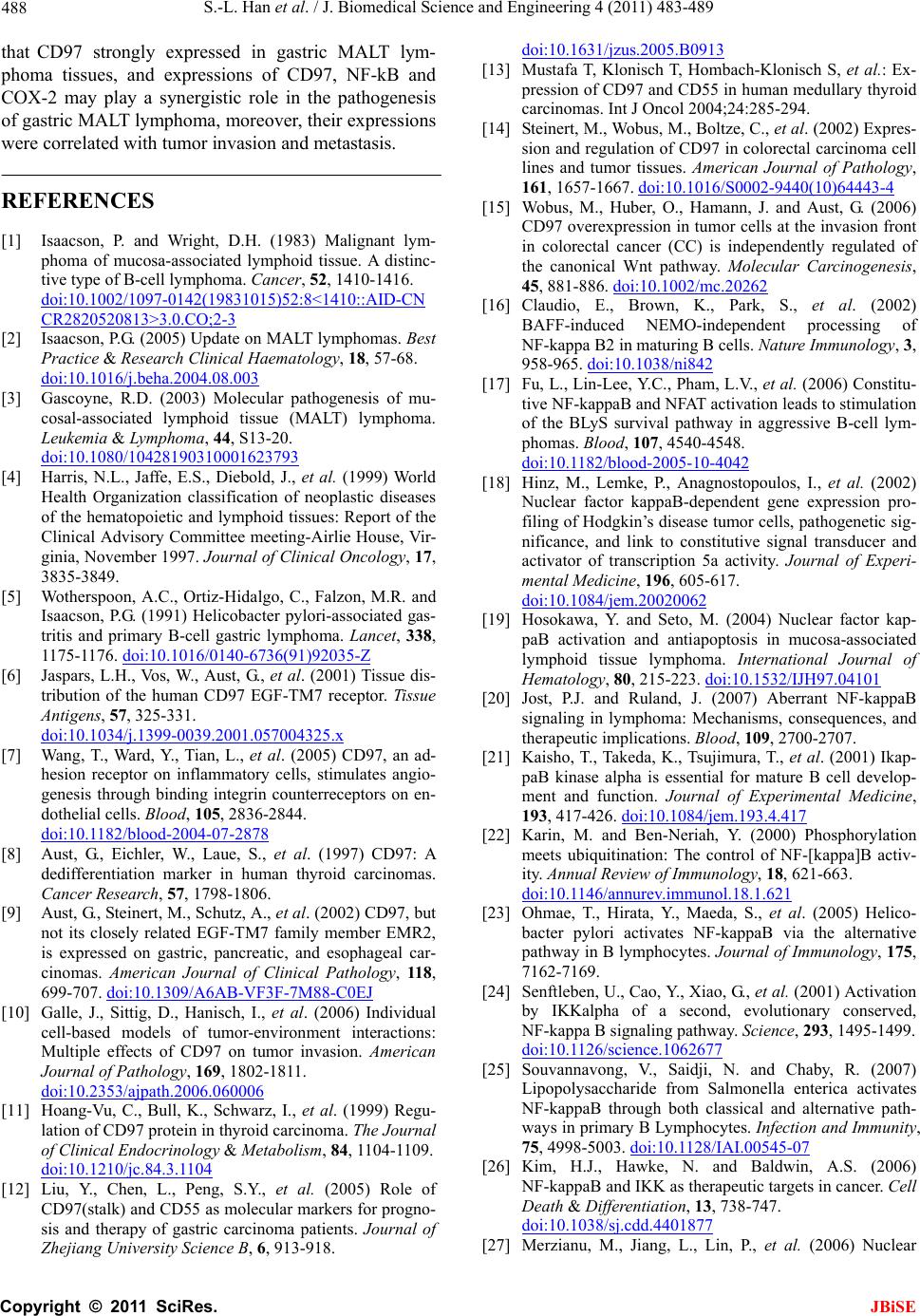

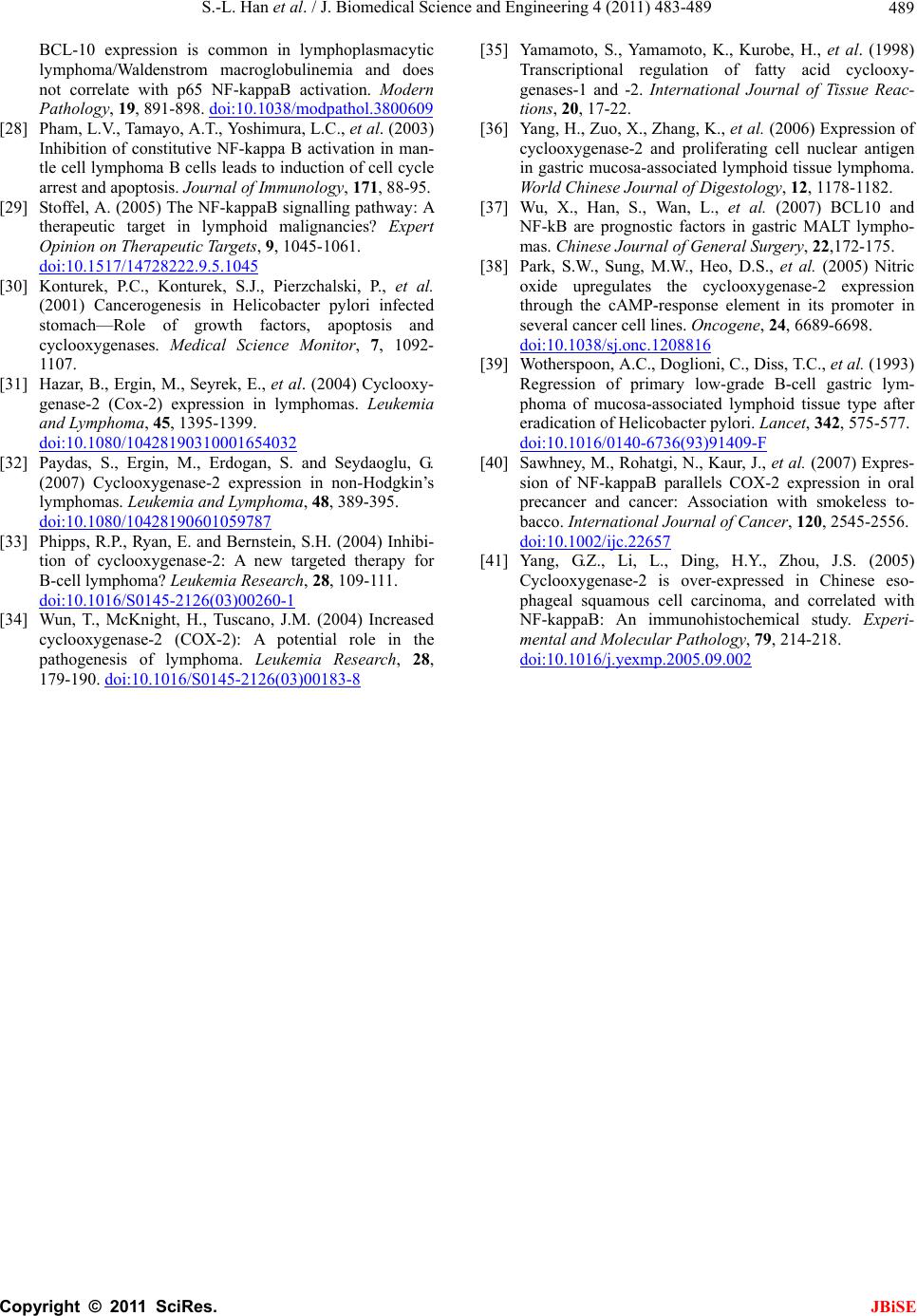

|