Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

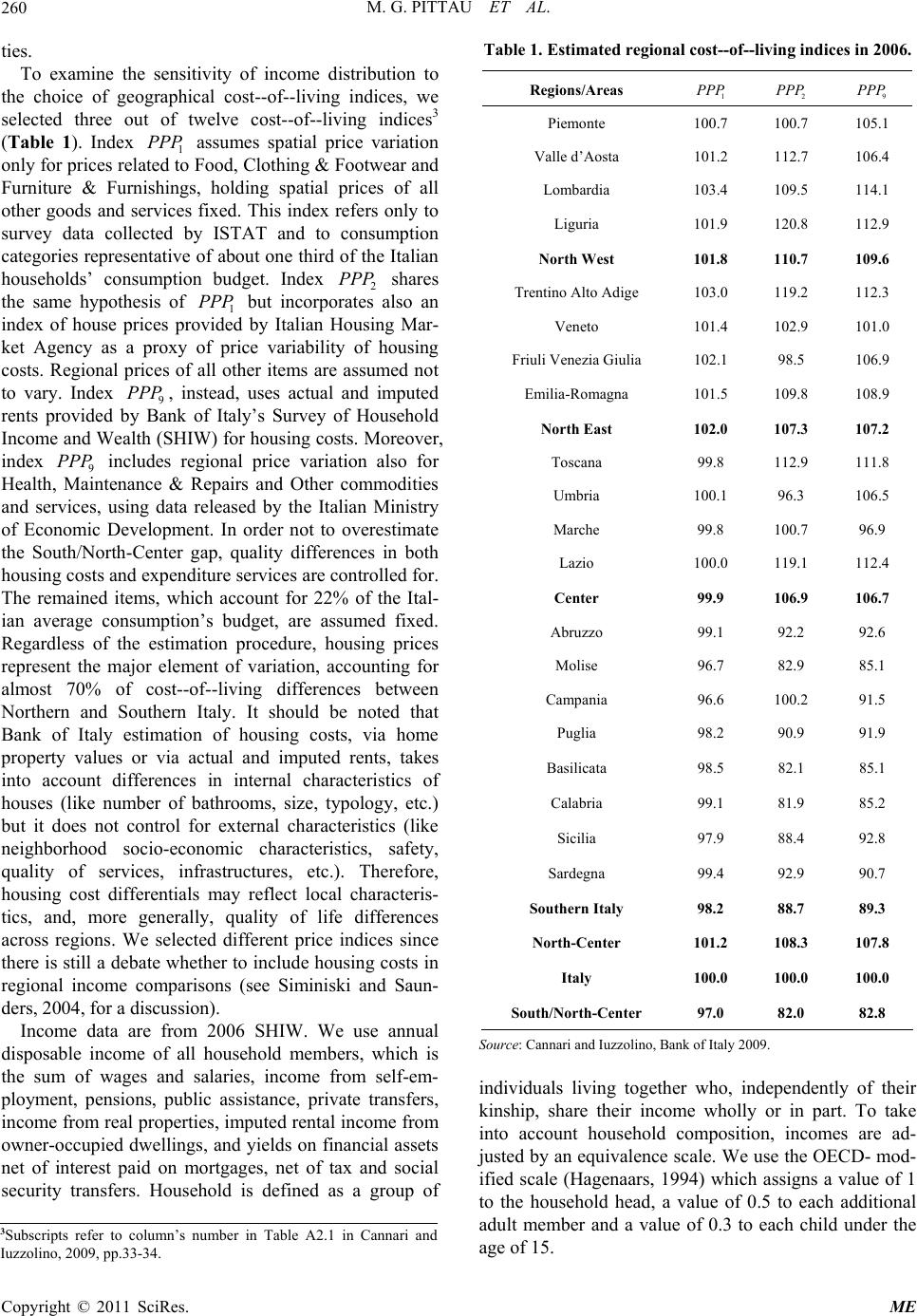

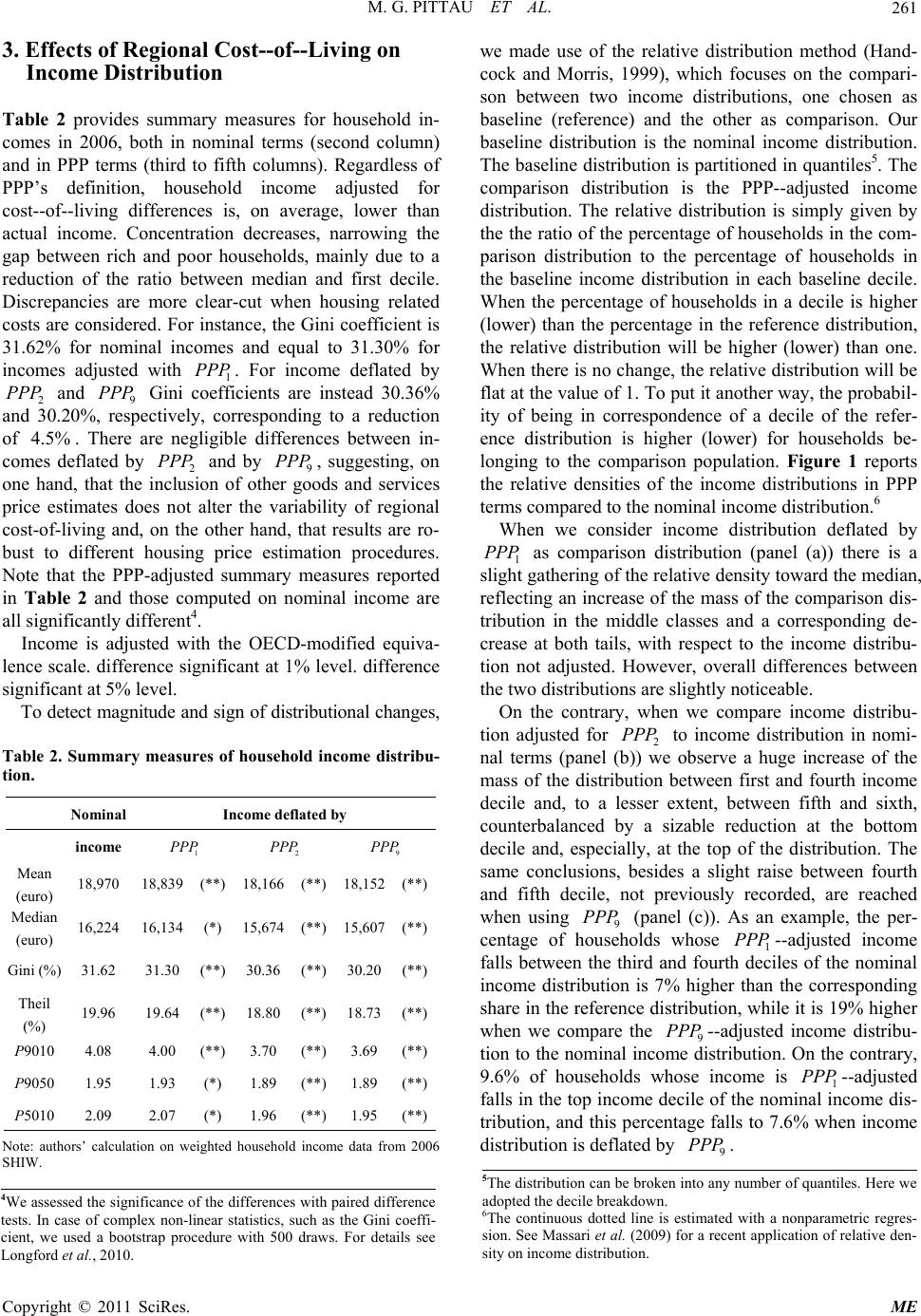

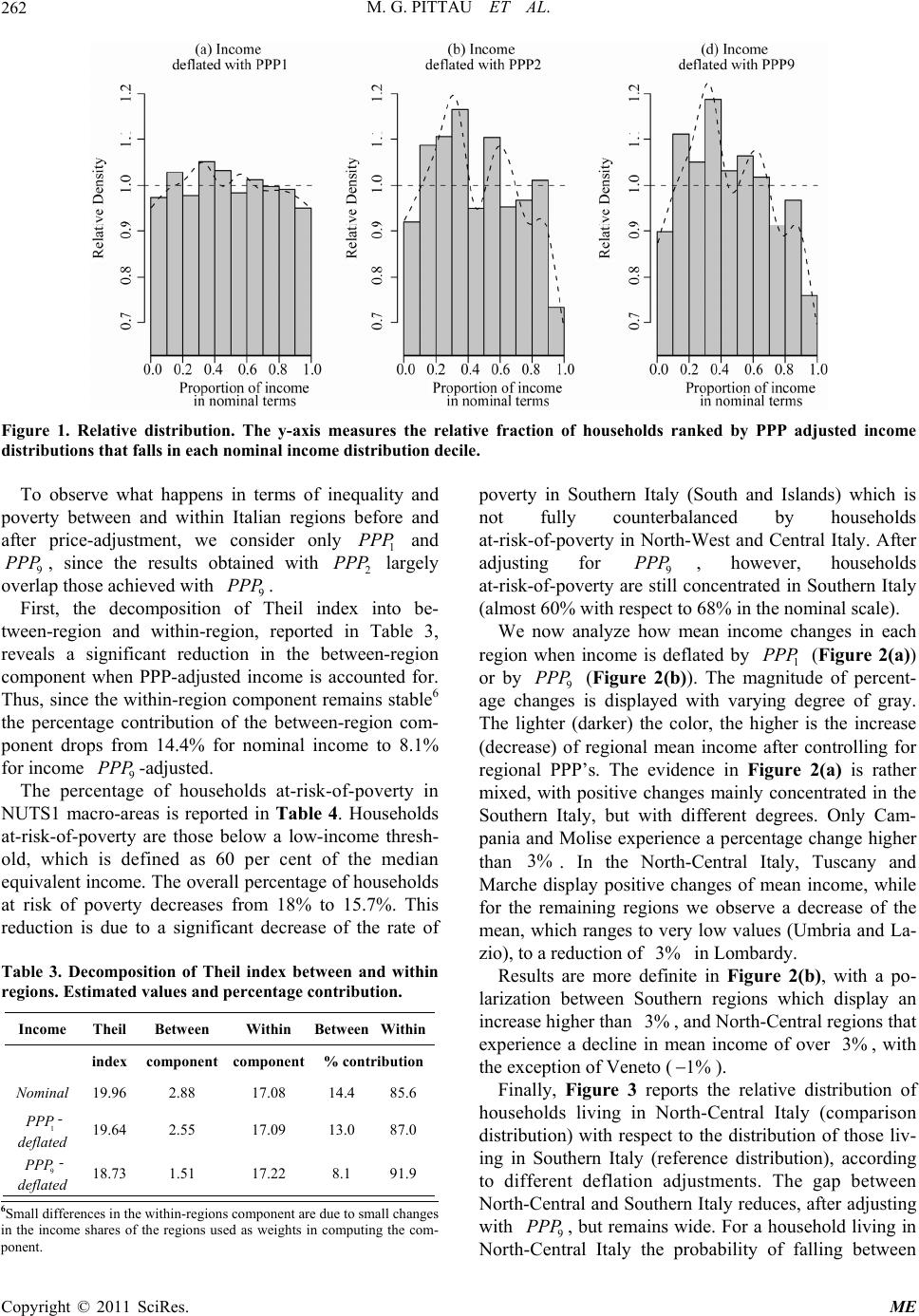

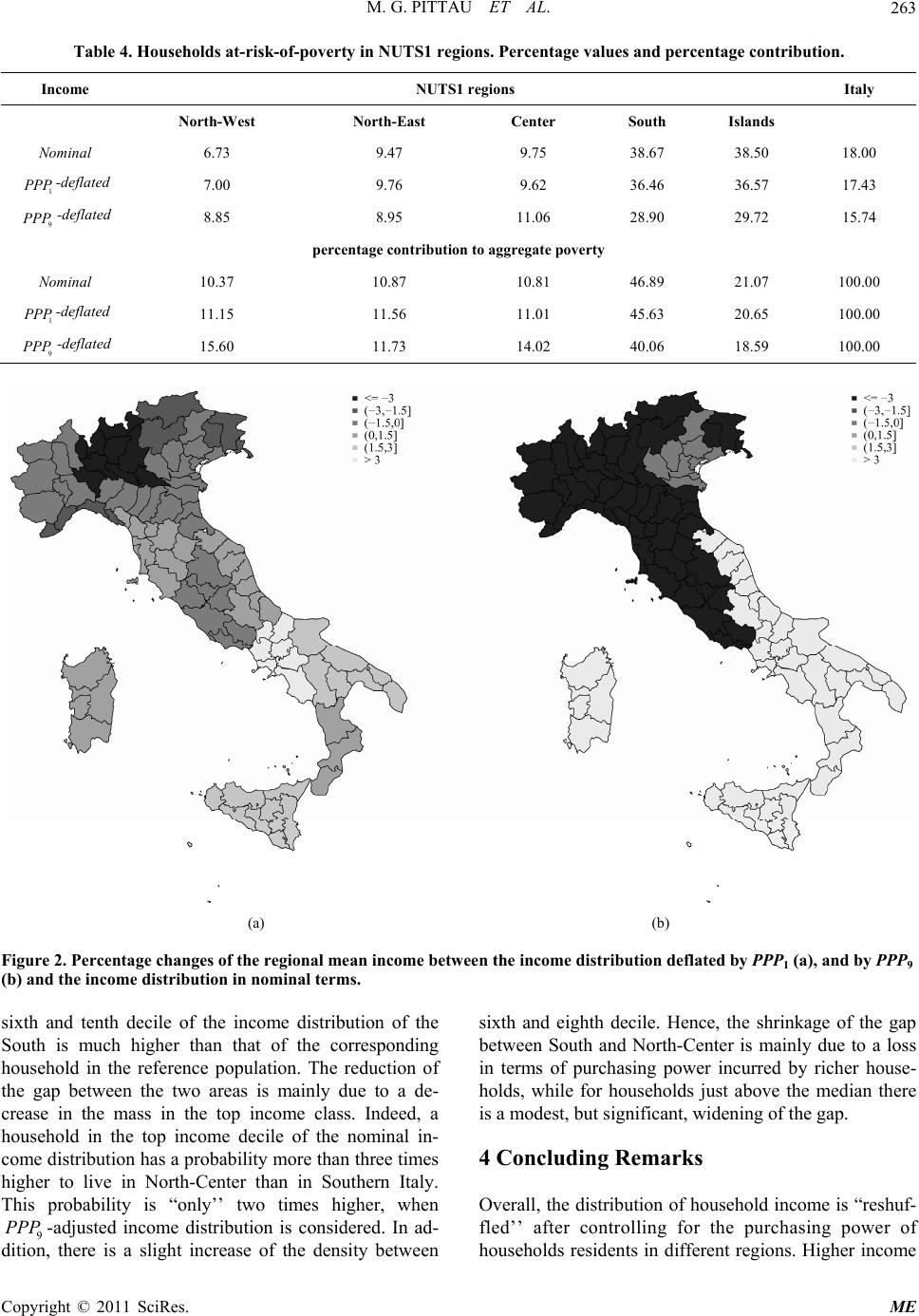

Modern Economy, 2011, 2, 259-265 doi:10.4236/me.2011.23029 Published Online July 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/me) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME Do Spatial Price Indices Reshuffle the Italian Income Distribution? M. Grazia Pittau, Roberto Zelli, Riccardo Massari_ Sapienza University of Rome, P.le ALdo Moro 5, Rome, Italy E-mail: {grazia.pittau, roberto.zelli, riccardo.massari}@uniroma1.it Received February 24 , 20 1 1; revised April 6, 2011; acce pte d April 20, 2011 Abstract This paper examines how spatial price differentials affect income distribution in Italy. Established results concerning disparities between the Northern and Southern regions of Italy hold up when adjusting incomes for the regional purchasing power. Poverty is still concentrated in the Southern part of the country. Further- more, the cost-of-living indices that have the highest impact on the Italian income distribution are those ac- counting for regional differential in housing prices. Keywords: Income Distribution, Regional Purchasing Power Parity, Italy 1. Introduction Adjusting for differences in relative price levels is wide- ly recognized as being important in inter-country inco me comparisons. Analogously, intra-country com- parisons should be adjusted for sub-national purchasing power parities (PPP). Regional cost-of-living1 adjust- ments affect real wages and public transfers and, to a larger extent, income distribution, poverty and inequality with- in a country. Nevertheless, PPP estimates require de- tailed price data which are not usually available at sub- national level. Spatial price variability has been investi- gated in developing countries, where regional price dif- ferences are expected to be wide because of high degrees of market segmentation (e.g. Coondoo et al., 2004; Jol- liffe et al., 2004; Gong and Meng, 2008), and relatively few attempts provide evidence for developed countries. For instance, poverty measures adjusted for cost of living differences in US metropolitan and nonmetropolitan ar- eas show a complete reversal of the nonmetro/metro original poverty profile (Jolliffe, 2006). Kosfeld and Eckey (2008) estimated consumer price index (CPI) and housing rent i n dex ( HR I) for German NUTS sub-national areas to analyze price disparities aross German regions. The authors found that disparities of regional per capita GDP adjusted for PPP reduced but did not eliminate East/West real income gap. Adjustment for regional cost of living of poverty rates in the United Kingdom, in- duced higher value of poverty in Greater London, South East, Scotland and Northern Ireland and smaller values in the North and in Yor kshire and Humberside (Borooah et al., 1996). Using regional price indices recently pro- vided by Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) and by Bank of Italy, this paper checks whether the well-known income disparity between Northern and Southern Italy persists after accounting for regional price differentials. The next section describes the spatial price indices estimated for Italian regions. Section 3 reports the main effects of cost of living adjustment on house- hold disposable income, inequality and poverty. Section 4 concludes. 2. Data ISTAT in collaboration with Institute Guglielmo Taglia- carne--Union of Italian Chambers of Commerce (Istat, 2008) estimated spatial price indices for Italian regions’ capital cities2 in 2006. Three expenditure items were selected: Food, Clothing & Footwear and Furniture & Furnishings. Based on these indices, Bank of Italy (Can- nari and Iuzzolino, 2009) first estimated regional price indices for other consumption categories, and then ag- gregated all the commodity--group prices into regional cost--of--living ind ices. Based on alternative hypotheses, which essentially refer to the estimation procedure of additional commodity--group indices and to the weights attached to each item in the aggregation pr ocedure, Bank of Italy finally estimated twelve purchasing power pari- 2Italian regions are administrative units that correspond to the second level of disaggregation in the Eurostat Nomenclature of the Territorial Units for Statistics, named NUTS2. 1Even if PPP and regional cost-of-living are not technically the same, we use these terms interchangeably in this context.  M. G. PITTAU ET AL. 260 ties. To examine the sensitivity of income distribution to the choice of geographical cost--of--living indices, we selected three out of twelve cost--of--living indices3 (Table 1). Index 1 assumes spatial price variation only for prices related to Food, Clothing & Footwear and Furniture & Furnishings, holding spatial prices of all other goods and services fixed. This index refers only to survey data collected by ISTAT and to consumption categories representative of about one third of the Italian households’ consumption budget. Index 2 shares the same hypothesis of 1 but incorporates also an index of house prices provided by Italian Housing Mar- ket Agency as a proxy of price variability of housing costs. Regional prices of all other items are assumed not to vary. Index 9, instead, uses actual and imputed rents provided by Bank of Italy’s Survey of Household Income and Wealth (SHIW) for housing costs. Moreover, index 9 includes regional price variation also for Health, Maintenance & Repairs and Other commodities and services, using data released by the Italian Ministry of Economic Development. In order not to overestimate the South/North-Center gap, quality differences in both housing costs and expenditure services are controlled for. The remained items, which account for 22% of the Ital- ian average consumption’s budget, are assumed fixed. Regardless of the estimation procedure, housing prices represent the major element of variation, accounting for almost 70% of cost--of--living differences between Northern and Southern Italy. It should be noted that Bank of Italy estimation of housing costs, via home property values or via actual and imputed rents, takes into account differences in internal characteristics of houses (like number of bathrooms, size, typology, etc.) but it does not control for external characteristics (like neighborhood socio-economic characteristics, safety, quality of services, infrastructures, etc.). Therefore, housing cost differentials may reflect local characteris- tics, and, more generally, quality of life differences across regions. We selected different price indices since there is still a debate whether to in clude housing costs in regional income comparisons (see Siminiski and Saun- ders, 2004, f or a discussion). PPP PPP PPP PPP PPP Income data are from 2006 SHIW. We use annual disposable income of all household members, which is the sum of wages and salaries, income from self-em- ployment, pensions, public assistance, private transfers, income from real properties, imputed rental income from owner-occupied dwelling s, and yields on financial assets net of interest paid on mortgages, net of tax and social security transfers. Household is defined as a group of Table 1. Estimated regional cost--of--living indices in 2006. Regions/Areas 1 PPP 2 PPP 9 PPP Piemonte 100.7 100.7 105.1 Valle d’Aosta 101.2 112.7 106.4 Lombardia 103.4 109.5 114.1 Liguria 101.9 120.8 112.9 North West 101.8 110.7 109.6 Trentino Alto Adige 103.0 119.2 112.3 Veneto 101.4 102.9 101.0 Friuli Venezia Giulia 102.1 98.5 106.9 Emilia-Romagna 101.5 109.8 108.9 North East 102.0 107.3 107.2 Toscana 99.8 112.9 111.8 Umbria 100.1 96.3 106.5 Marche 99.8 100.7 96.9 Lazio 100.0 119.1 112.4 Center 99.9 106.9 106.7 Abruzzo 99.1 92.2 92.6 Molise 96.7 82.9 85.1 Campania 96.6 100.2 91.5 Puglia 98.2 90.9 91.9 Basilicata 98.5 82.1 85.1 Calabria 99.1 81.9 85.2 Sicilia 97.9 88.4 92.8 Sardegna 99.4 92.9 90.7 Southern Italy 98.2 88.7 89.3 North-Center 101.2 108.3 107.8 Italy 100.0 100.0 100.0 South/North-Center 97.0 82.0 82.8 Source: Cannari and I u zzolino, Bank of Ita ly 2009. individuals living together who, independently of their kinship, share their income wholly or in part. To take into account household composition, incomes are ad- justed by an equivalence scale. We use the OECD- mod- ified scale (Hagenaars, 1994) which assigns a value of 1 to the household head, a value of 0.5 to each additional adult member and a value of 0.3 to each child under the age of 15. 3Subscripts refer to column’s number in Table A2.1 in Cannari and Iuzzolino, 2009, pp.33-34. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  M. G. PITTAU ET AL.261 3. Effects of Regional Cost--of--Living on Income Distribution Table 2 provides summary measures for household in- comes in 2006, both in nominal terms (second column) and in PPP terms (third to fifth columns). Regardless of PPP’s definition, household income adjusted for cost--of--living differences is, on average, lower than actual income. Concentration decreases, narrowing the gap between rich and poor households, mainly due to a reduction of the ratio between median and first decile. Discrepancies are more clear-cut when housing related costs are considered. For instance, the Gini coefficient is 31.62% for nominal incomes and equal to 31.30% for incomes adjusted with 1. For income deflated by 2 and 9 Gini coefficients are instead 30.36% and 30.20%, respectively, corresponding to a reduction of . There are negligible differences between in- comes deflated by 2 and by 9, suggesting, on one hand, that the inclusion of other goods and services price estimates does not alter the variability of regional cost-of-living and, on the other hand, that results are ro- bust to different housing price estimation procedures. Note that the PPP-adjusted summary measures reported in Table 2 and those computed on nominal income are all significantly different4. PPP P PPP 4.5% PPP PP PPP Income is adjusted with the OECD-modified equiva- lence scale. difference significant at 1% level. difference significant at 5% level. To detect magnitude and sign of distributional changes, Table 2. Summary measures of household income distribu- tion. Nominal Income deflated by income 1 PPP 2 PPP 9 PPP Mean ( euro ) 18,970 18,839 (**) 18,166 (**) 18,152(**) Median ( euro ) 16,224 16,134 (*) 15,674 (**) 15,607 (**) Gini (%) 31.62 31.30 (**) 30.36 (**) 30.20(**) Theil ( % ) 19.96 19.64 (**) 18.80 (**) 18.73(**) 9010P 4.08 4.00 (**) 3.70 (**) 3.69 (**) 9050P 1.95 1.93 (*) 1.89 (**) 1.89 (**) 5010P 2.09 2.07 (*) 1.96 (**) 1.95 (**) Note: authors’ calculation on weighted household income data from 2006 SHIW. we made use of the relative distribution method (Hand- cock and Morris, 1999), which focuses on the compari- son between two income distributions, one chosen as baseline (reference) and the other as comparison. Our baseline distribution is the nominal income distribution. The baseline distribution is partition ed in quantiles5. The comparison distribution is the PPP--adjusted income distribution. The relative distribution is simply given by the the ratio of the percentage of househo lds in the com- parison distribution to the percentage of households in the baseline income distribution in each baseline decile. When the percentage of households in a decile is higher (lower) than the percentage in the reference distribution, the relative distribution will be higher (lower) than one. When there is no change, the relativ e distribution will be flat at the value of 1. To put it another way, the probabil- ity of being in correspondence of a decile of the refer- ence distribution is higher (lower) for households be- longing to the comparison population. Figure 1 reports the relative densities of the income distributions in PPP terms compared to the nominal income distribution.6 When we consider income distribution deflated by 1 as comparison distribution (panel (a)) there is a slight gathering of the relative density toward the median, reflecting an increase of the mass of the comparison dis- tribution in the middle classes and a corresponding de- crease at both tails, with respect to the income distribu- tion not adjusted. However, overall differences between the two distributions are slightly noticeable. PPP On the contrary, when we compare income distribu- tion adjusted for 2 to income distribution in nomi- nal terms (panel (b)) we observe a huge increase of the mass of the distribution between first and fourth income decile and, to a lesser extent, between fifth and sixth, counterbalanced by a sizable reduction at the bottom decile and, especially, at the top of the distribution. The same conclusions, besides a slight raise between fourth and fifth decile, not previously recorded, are reached when using 9 (panel (c)). As an example, the per- centage of households whose 1--adjusted income falls between the third and fourth deciles of the nominal income distribution is 7% higher than the corresponding share in the reference distribution, wh ile it is 19% higher when we compare the 9--adjusted income distribu- tion to the nominal income distribution. On the con trary, 9.6% of households whose income is 1--adjusted falls in the top income decile of the nominal income dis- tribution, and this percentage falls to 7.6% when income distribution is deflated by . PPP PPP PPP PPP PP PPP 9 P 5The distribution can be broken into any number of quantiles. Here we adopted the decile breakdown. 6The continuous dotted line is estimated with a nonparametric regres- sion. See Massari et al. (2009) for a recent application of relative den- sit y on income distribution. 4We assessed the significance of the differences with paired difference tests. In case of complex non-linear statistics, such as the Gini coeffi- cient, we used a bootstrap procedure with 500 draws. For details see Longford et al., 2010. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  M. G. PITTAU ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 262 Figure 1. Relative distribution. The y-axis measures the relative fraction of households ranked by PPP adjusted income distributions that falls in each nominal income distribution decile. To observe what happens in terms of inequality and poverty between and within Italian regions before and after price-adjustment, we consider only 1 and 9, since the results obtained with largely overlap those achieved with . PPP 2 PPPP PP poverty in Southern Italy (South and Islands) which is not fully counterbalanced by households at-risk-of-poverty in North-West and Central Italy. After adjusting for 9, however, households at-risk-of-poverty are still concentrated in Southern Italy (almost 60% with respect to 68% in the no minal scale). PPP 9 First, the decomposition of Theil index into be- tween-region and within-region, reported in Table 3, reveals a significant reduction in the between-region component when PPP-adjusted income is accounted for. Thus, since the within-region component remains stable6 the percentage contribution of the between-region com- ponent drops from 14.4% for nominal income to 8.1% for income -adjusted. PPP We now analyze how mean income changes in each region when income is deflated by 1 (Figure 2(a)) or by 9 (Figure 2(b)). The magnitude of percent- age changes is displayed with varying degree of gray. The lighter (darker) the color, the higher is the increase (decrease) of regional mean income after controlling for regional PPP’s. The evidence in Figure 2(a) is rather mixed, with positive changes mainly concentrated in the Southern Italy, but with different degrees. Only Cam- pania and Molise experience a percentage change higher than . In the North-Central Italy, Tuscany and Marche display positive changes of mean income, while for the remaining regions we observe a decrease of the mean, which ranges to very low values (Umbria and La- zio), to a reduction of in Lombardy. PPP PPP 3% 3% 9 The percentage of households at-risk-of-poverty in NUTS1 macro-areas is reported in Table 4. Households at-risk-of-poverty are those below a low-income thresh- old, which is defined as 60 per cent of the median equivalent income. The overall percentage of households at risk of poverty decreases from 18% to 15.7%. This reduction is due to a significant decrease of the rate of PPP Table 3. Decomposition of Theil index between and within regions. Estimated values and percentage contribution. Results are more definite in Figure 2(b), with a po- larization between Southern regions which display an increase higher than , and North-Central regions that experience a decline in mean income of over , with the exception of Veneto ( 3% 3% 1% ). Income Theil Between Within Between Within index component component % contribution Nominal 19.96 2.88 17.08 14.4 85.6 1- deflated PPP 19.64 2.55 17.09 13.0 87.0 9- deflated PPP 18.73 1.51 17.22 8.1 91.9 Finally, Figure 3 reports the relative distribution of households living in North-Central Italy (comparison distribution) with respect to the distribution of those liv- ing in Southern Italy (reference distribution), according to different deflation adjustments. The gap between North-Central and Southern Italy reduces, after adjusting with 9, but remains wide. For a household living in North-Central Italy the probability of falling between PPP 6Small differences in the within-regions component are d ue to small changes in the income shares of the regions us ed as weights in computing the com- ponent.  M. G. PITTAU ET AL.263 Table 4. Households at-risk-of-poverty in NUTS1 regions. Percentage values and percentage contribution. Income NUTS1 regions Italy North-West North-East Center South Islands Nominal 6.73 9.47 9.75 38.67 38.50 18.00 1 PPP -deflated 7.00 9.76 9.62 36.46 36.57 17.43 9 PPP -deflated 8.85 8.95 11.06 28.90 29.72 15.74 percentage contribution to aggregate poverty Nominal 10.37 10.87 10.81 46.89 21.07 100.00 1 PPP -deflated 11.15 11.56 11.01 45.63 20.65 100.00 9 PPP -deflated 15.60 11.73 14.02 40.06 18.59 100.00 (a) (b) Figure 2. Percentage changes of the regional mean income between the income distribution deflated by PPP1 (a), and by PPP9 (b) and the income distribution in nominal terms. sixth and tenth decile of the income distribution of the South is much higher than that of the corresponding household in the reference population. The reduction of the gap between the two areas is mainly due to a de- crease in the mass in the top income class. Indeed, a household in the top income decile of the nominal in- come distribution has a pro bability more than three times higher to live in North-Center than in Southern Italy. This probability is “only’’ two times higher, when 9-adjusted income distribution is considered. In ad- dition, there is a slight increase of the density between sixth and eighth decile. Hence, the shrinkage of the gap between South and North-Center is mainly due to a loss in terms of purchasing power incurred by richer house- holds, while for households just above the median there is a modest, but significant, widening of the gap. PPP 4 Concluding Remarks Overall, the distribution of household income is “reshuf- fled’’ after controlling for the purchasing power of households residents in different regions. Higher income Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  M. G. PITTAU ET AL. 264 Figure 3. Relative distribution. The y-axis measures the relative fraction of households living in North-Central Italy that falls in each Southern Italy income decile, according to different deflation adjustments. regions tend to be higher price level regions, therefore inequality between regions and overall inequality across households reduces after adjusting for prices. The ap- parent living standards of households living in the South improve when the regional price index is used, but only when housing price variations are included in the index. Despite this, poverty is still concentrated in the South whichever regional price index is used. An issue left for further research regards the relationship between quality of life and cost-of-living. Had housing costs been posi- tively correlated with quality of life, the gain in terms of purchasing power experienced by households living in poorer areas, where housing prices are typically lower, could be interpreted as a compensation for the loss in terms of quality of life. 5. Acknowledgments we would like to thank an anonymous referee for helpful comments. 6. Reference [1] Borooah V. K, Gregor P. P. M., Kee P. M. M., Mulhol- land G.E., (1996). Cost--of--living differences between the regions of the United Kingdom, in J. Hills (Ed.), New Inequalities, the changing distribution of income and wealth in the United Kingdom, Cambridge University Press. [2] Cannari L., Iuzzolino G., (2009). Le differenze nel livello dei prezzi al consumo tra Nord e Sud, Questioni di Eco- nomia e Finanza, Banca d’Italia. [3] Coondoo D., Majumder A., Ray R., (2004). A Method of Calculating Regional Consumer Price Differentials with Illustrative Evidence from India, Review of Income and Wealth, 50(1), 51-68. [4] Gong, C.H., Meng X., (2008). Regional Price Differences in Urban China 1986-2001: Estimation and Implication, IZA Discussion Papers, n.3621. [5] Hagenaars A. J. M., K. De Vos and M. A. Zaidi (1994). Poverty Statistics in the Late 1980s: Research Based on Micro-Data, Office for Official Publications of the Euro- pean Communities. Luxembourg. [6] Handcock M. S., Morris M., (1999). Relative distribution methods in the social sciences, Cambridge University Press. [7] Istat (2008). Le differenze nel livello dei prezzi tra i ca- poluoghi delle regioni italiane per alcune tipologie di beni, Istat, Roma. [8] Jolliffe D., (2006), Poverty, Prices, and Place: How Sen- sitive is the Spatial Distribution of Poverty to Cost of Living Adjustments?, Economic Inquiry, 44(2), 296-310. [9] Jolliffe D., Datt G., Sharma M., (2004), Robust Poverty and Inequality Measurement in Egypt: Correcting for Spatial-price Variation and Sample Design Effects, Re- view of Development Economics, 8(4), 557-572 [10] Kosfeld R., Eckey H.F., (2008). Market Access, Regional Price Level and Wage Disparities: The German Case, MAGKS Papers on Economics, Philipps-Universitt Mar- burg. [11] Longford N. T., M. G. Pittau, R. Zelli and Riccardo Massari (2010). Measures of poverty and inequality in the countries and regions of EU, ECINEQ Working Papers Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  M. G. PITTAU ET AL.265 182, Society f or th e S tu dy of Economic Inequality . [12] Massari R., M. G. Pittau and R. Zelli (2009). A dwindling middle class? Italian evidence in the 2000s. Journal of Economic Inequality, 7(4), pages 333-350. [13] Siminski P. and P. Saunders (2004). Accounting for Housing Costs in Regional Income Comparisons. Aus- tralasian Journal of Regional Studies 10(2), 139-156. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME |