Open Access Library Journal, 2014, 1, 1-9 Published Online June 2014 in OALib. http://www.oalib.com/journal http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/oalib.1100651 How to cite this paper: Sado, E. and Gedif, T. (2014) Drug Utilization at Household Level in Nekemte Town and Surrounding Rural Areas, Western Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Open Access Library Journal, 1: e651. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/oalib.1100651 Drug Utilization at Household Level in Nekemte Town and Surrounding Rural Areas, Western Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study Edao Sado1*, Teferi Gedif2 1Department of Pharmacy, College of Medical and Health Science, Wollega University, Nekemte, Ethiopia 2Department of Pharmaceutics and Social Pharmacy, School of Pharmacy, College of Health Science, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Email: *edaosd6@gmail.com Received 5 May 2014; revised 7 June 2014; accepted 15 June 2014 Copyright © 2014 by authors and OALib. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract Background : At household levels drug may be hoarded and re-utilized inappropriately, shared within families and/or outside family and unnecessarily utilized in self-medication. Therefore this study was conducted to assess drug utilization at household level in Nekemte town and surround- ing rural areas western Ethiop ia. Methods: It was conducted on 844 households’ head through in- terviewing where households were stratified into urban and rural; a household was selected by using systematic random and cluster sampling in the town and rural areas respectively. Results: It was found that prevalence of drug hoarding was 49.9% where urban areas were 1.4 times more likely to hoard drug than rural areas (Adjusted OR = 1.4; 95% CI = 1.02 - 1.8) and it was also found that drug hoarding was associated with level of households’ education where household heads who had level of education higher than or equal primary were 1.5 times more likely to hoard drug (Adjusted OR = 1.5; 95% CI = 1.04 - 2.3). The prevalence of drug sharing was found to be 24.9% where urban areas were 0.4 times less likely to share drugs than surrounding rural areas (Crude OR = 0.4; 95% CI = 0.3 - 0.6). Nineteen point five percent of illness episodes were reported from total surveyed households where 36.3% of them were sel f-medicated with modern medicines. Self-medication with modern drugs was significantly associated with age older than fifteen years old (Crude OR = 0.37; %CI = 0.2, 0.83). Conclusions: Drug hoarding, sharing and self-medication with modern drugs particularly antibiotics are commonly practiced in the community, so they should be avoided through educating general public on drug use so as to minimize of risk of using expired drugs and accidental poisoning; under dose and inappropriate use; and combat antim- icrobial resistance. *Corresponding author.  E. Sado, T. Gedif Keywords Drug Utilization , Drug Hoarding, Nekemte Town and Surrounding Rural Area, Self-Med ic ation, Western Ethiopia Subject Areas: Drugs & Devices, Epidemiology, Evidence Based Medicine, Global Health, Health Policy, Phar macolo gy 1. Introduction According to World Hea lth Organization drug utilization is defined as “the marketing, distrib ution, prescr ibing, and use of drugs in society, with special emphasis on the resulting medical, social, and economic consequences” [1]. Thus drug utilizat ion study focuses on the factors related to the prescribing, dispensing, administering, and taking of medication, and its associated events, covering the medical and non-medical determinants of drug utilization [2]; it also evaluates drug use at a population level, according to age, sex, social class, morbidity and residence areas [2] [3]. Essential medicines are one of the vital tools needed to improve and maintain health. However, for too many people throughout the world medicines remain unaffordable, unavailable, unsafe and improperly used. When available, the medicines are often used incorrectly: where medicines are prescribed, dispensed or sold inappro- priatel y and patients fa il to tak e their medicines ap pr op riately [4]. All prescribing is not nec essaril y based on pa- tient needs a nd all patient needs are not necessarily met with drug therapy. Consequently, there is much concern about inappropriate and expensive prescribing [5]. Rational use of medicines is a crucial part of the national health policy and access to medicines is a tool to improve and maintain health. Rational use of medicine has been defined as patients receive medications appro- priately to their clinical needs, in doses that meet their individual requirements, for an adequate period of time, and at the lowest cost to them and their co mmunit y while irratio nal or non-rational use is the use of medicines in a way that is not c ompliant with rational use [6] [7]. Irrational use of medicines is a worldwide proble m, which has a serious impact on health and economy [6] [8]. The op timal benefits o f drug ther apy in patient care i n every community may not be achi eved because of in- app r opr ia te d rugs use [4]. One of the inappropriate drug uses is prematurely discontinued treatment course when they felt that the symptoms had abated and kept the rest of the medicines for future use [9]-[14]. Other forms of inappropriate drug use are drug sharing and sel f-medication. Sharing of drugs can be within and across households for friends, neighbors and relatives [14] [15]. Se l f-medicatio n with antibiotics in co mmu- nity i s common i n third world countrie s [16]. Hence people are willing to pay high prices for antibiotics, and if they cannot afford a full course, they will purchase them in smaller quantities [14] [17]-[21]. Self-medication may also be influenced by low severity of illness [22] and easy acce ssibi lit y o f d rug s fro m i nfor mal sect or s suc h as open mar kets and village ki osks [23]. Drug utilization can be influenced by socio-demographic factors such as age, sex, social status; education, morbidity, cultural heritage, individual attitudes, and personality are among the factors that have been associated with the use of medicines [24]. But o ver a ll, morbidit y is the str ongest pred ic tor of drug utilization [25]. Pat terns o f drugs p resc ribin g and d rugs use on the inst itutio nal le vels have be en exte nsive ly st udied in de vel- oping country [26]. However, there has not yet been any systematic research conducted on the utilization of drugs at the ho usehold le vel, little is k nown about patterns of dr ug utilization a t household le vel in Ethiop ia [27]. At household level drug may be utilized in different ways such as being hoarded and re-utilized, shared with household and/or outside households for neighbors and might be used for self-medication inappropriately. In- for matio n on t hese for ms o f d rug ut iliza ti on at hou seho ld l eve ls in N eke mte to wn and sur ro undi ng rur al ar ea s is scarce and anecdotal. Nekemte town is selected because it is the most populous and oldest city in the western part of Oro mia National Re gional state. So we supposed that information obtained from this study may be used to improve rational use of drugs by policy makers. The aim of this study is therefore to assess prevalence of drug hoar ding, self-medi cation with modern drugs and drug shari ng practice at household level.  E. Sado, T. Gedif 2. Methods The study was conducted in Nekemte town and surrounding areas located at 328 Km west of Addis Ababa, the capital cit y of Ethio pia. Nekemte i s the largest town in the Western part of t he Oromia Na tional Regional State, Ethiopia. Oromia National Regional State is one of the nine regions in Ethiopia and it is the largest and most populous region. The town is surrounded by rural kebeles namely Gari, in the East, Feyinera in the West, Kitesa in the North, and Alemi in the South. Currently it is a capital city of East Wollega Zone with the total area of 5480 hectares. Administratively, it is divided in to six sub cities with a total of 12 Kebeles and with a total of 20,000 households. A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted in August, 2012 among households’ heads to assess the prevalence of drug hoardi ng, drug shar ing, self-medicatio n and their determinant s. All house holds were included in the st udy and pr o po rt io nal ly st ra tif ie d into ur b an a nd surr o und i ng r ura l areas. S ystematic and cluster sampling technique were employed to obtain a single household from urban and surrounding rural areas respectively. The sample size was determined by using single proportion formula [28]. Since no up to date and no reliable information was available on the prevalence of drug utilization at household level; 50% prevalence was assumed with 95% confidence level and 5% sampling error. After considering a design effect of 2% and 10% compensa- tion for non-response, the sample size was determined to be 844. A s em i -structured questionnaire consisting of open and closed ended questions was developed from a review of the literature. The anonymous questionnaire covers socio-demographic factors in addition to drug hoarding, shari ng and self-medication. The English version of the questionnaire was translated into Afan Oromo, the offi- cial language of the study area, by a panel of experts fluent in the lan guage. It was then translated back in to Engl ish b y anot her per son t o ens ure consi ste nc y with t he E ngl ish l ang uage q ue stio nna ire . T he Afan O ro mo ve r- sion was used to collect data. It was employed after pre-testing on 84 households head outside but close to the study area and corrections was made thereafter to improve the clarity of some items. Data we re collected by trained data collectors through intervie wing t he house holds ’ head s. The princip al invest igat or ca rried out on site supervision to check the completeness, clarity, accuracy, and consistency of the interview administration. Data was coded, cleaned and entered into Epi-info version 3.5.3 and exported to SPSS for windows version 16.0. Analysis was done by using SPSS version 16 and Microsoft Office Excel 2007. Descriptive statistics were conducted using frequencies and proportions. Bivariate and multivariate analyses were carried out using logistic regr essio n to exa mine the r ela tions hip bet ween the d rug ho ardi ng, shari ng and self-medication; and selected de- terminant factors. Adjusted and unadjusted odds ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used as indicators of strength of association. A P value o f 0.05 or less wa s used as t he cut -off level for statistica l sig- nificance. For the sake of clarity the follo wings are operationalized: Drug hoarding―keeping at least one drug at home for the purpose of preventing, tre a ting or alleviating diseases or left over drugs. Drug sharing-refers to sharing of drugs for therapeutic or prophylaxis purpose not for recreational purpose. Self-medication-refers to the use of modern drugs without recommendation of health care professionals regardless of their sources. Drug utilization- using any modern drug for the purpose of preventing, treating or alleviating disease regardless of its source. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee of the School of Pharmacy, College of Health Science s, Addis Abab a Univer sity. A letter of coop eration was written fro m Addis Ababa University a nd further approval was obtained from the zonal health bureau and administration department. The objective of the study was explained to the study participants. The household heads were briefed about the confidentiality of their response and the importance of providing correct and accurate information, and that participation was vol- untary. All parti cipa nts included in the study ha ve pr ovided a verbal conse nt 3. Results 3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Studied Participants Out of a total of 844 of households heads interviewed, 820 respondents provided full information and included in the study this making a response rate of 97.2%. Of these 408 (49.8%) were males and 412 (50.2%) were fe- male. The mean (SD) age of the respondent s’ was 3 1 (11.3). Five hundred and thirty one (64.8%) of the respon- dent were married and the rest 289 (35.2%) were single. The mean (SD) household size of the study population was 4.8 (2.2) persons. Five hundred and for ty (66%) of the surveyed house holds ha d famil y size less t han five,  E. Sado, T. Gedif 268 (32.7%) had between 5 and 10, and the rest 12 (1.3%) had more than 11. The majority 678 (82.7%) of the respondents were Christian and 142 (17.4%) of the respondents were Muslims. Oromo constituted the largest 709 (86.5%) ethnic group followed by Amhara 71 (8.7%) and Guragie 29 (3.5%) (Table 1). 3.2. Drug Hoarding A total of 409 (49.9%) households head hoarded drugs at their home. Two hundred twenty three (54.5%) of whom were from urban and 186 (44.5%) were from the surrounding rural areas. In all households which hoarded drugs, 719 different types of drugs products were encountered. Hence the average number (SD) of drugs per household was found to be 1.8 (1.2). Drugs used for the treatment of infectious diseases were the second most hoarded types of drugs at household level 180 (25%), next to Analgesics such as Paracetamol, Diclofenac, Ibuprofen and Aspirin which were the leading drugs 294 (41%) and the other significant categories of drugs kept in the households were GIT drugs 100 (13.9%), CVS drugs and drugs used for endocrine disorders 28 (3.8%) and respiratory drugs account 29 (4%). Twenty four (3.3%) of all the drugs found in the households, were unidentified because they were either not labeled or their label was removed and 64 (9%) others (Figure 1). Factors Independently Associated with Drug Hoarding The study showed that place of residence (X2 = 5.9, P < 0.05) and levels of education (X2 = 4.2, P < 0.05) were significantly associated with drug ho arding at households’ level. In ord e r to determine the str e ngth of associa tion, multivariate logistic regression analysis was run and it showed that the odds of drug hoarding were 1.4 times higher with urban household heads compared to surrounding rural areas households head (Adjusted OR = 1.4; 95% CI = 1.0, 1.8). Households head who had level of education higher than primary education were 1.5 times higher odds compared to those who had level education less than primary education (Adjusted OR = 1.5; 95% CI = 1.0, 2.3) (Table 2). Table 1 . Socio -demographic characteristics of respondents surveyed from households in Nekemte town and surrounding ru- ral areas western Ethiopia August, 2012 (N = 820). Var iables Frequency Percentage Sex Male Fema le 408 412 49. 8 50.2 Age 18 - 30 31 - 43 44 - 56 ≥57 487 223 85 25 59.4 27.2 10.4 3 Marital status Married Sin g le# 5 31 289 64. 8 35.2 Religion Christian* Mu s lim 6 78 142 82. 7 17.3 Ethnicity Oromo Amhara Guragie Tigre 709 71 29 11 86.5 8.7 3.5 1.3 Educati on al status <Primary ≥Prima ry 350 470 42. 7 57.3 Occupation Employed Unem ployed @ Farmers 195 439 186 23.8 53.5 22.7 Household size Less than 5 ≥5 540 280 65. 9 34.1 Christian*: Orthodox, Prot estant, Catholic; Unemp loyed @: includes jobless, housewife, daily labours. Single#: Unmarried, widow, divorced.  E. Sado, T. Gedif Table 2. Factors determining drugs hoarding at household level in Nekemte town and surrounding rural areas western Ethio- pia, August 2012. Variable Drug hoarding Crude OR Adjuste d OR 95% CI Yes No Sex Male Fema le 207 202 201 210 1 .3 1.0 1.1 (0.8, 1.6) 1 (-) Marital status Married Sin g le# 2 67 142 264 147 1 .2 1.0 1.2 (0.6, 2.6) 1 (-) Place of residence Urban Rural 223 186 189 222 1 .5 1.0 1.4 (1.02, 1. 8)* 1 (-) Religion Christian Mu s lim 3 31 78 347 63 0.9 1.0 0.9 (0.6, 1.3) 1 (-) Level of education <primary ≥pri mary 61 177 79 153 1 .0 1.5 1 (-) 1.5 (1.04, 2.3)* Household size ≤5 >5 272 137 270 141 1 .0 1.02 1 (-) 1.02 (0.8, 1.4) *P < 0.05; Single #: Unmarried, widow, divorced. Figure 1. Frequency of the pharmacological category of drugs hoarded in surveyed households in Nekemte town and surrounding rural areas western Ethiopia August, 2012. 3.3. Drugs Sharing and Its Influencing Factors It was found that prevalence of drug sharing wit hin the household and outside househol d including friends and neighbors was 24.9%. It was also found that drug sharing was significantly associated with place of residence (X2 = 7.9, P < 0.05). Binary logistic regression showed that the odds of drug sharing were 0.4 times less with those liv in g i n urb a n as c o mp a re d to tho se li vin g in s ur ro un d ing r ura l a r ea s (C rud e OR = 0. 4 ; 95 % CI = 0.3, 0.6) (Table 3). 3.4. Self-Medication Practice A total of 160 households head reported illness episodes in four weeks recall period, where 51 (36.7%) of them  E. Sado, T. Gedif Table 3. Factors associated with drug sharing in Nekemte town and surrounding rural areas western Ethiopia August, 2012. Variables Drug sharing Cru de OR 95% CI Yes No Residence area Urba n Rural 72 132 340 276 0.4 (0.3, 0.6)* 1 (-) Sex Male Fema le 108 96 300 316 1 (-) 1.1 (0.8, 1.6) Age 18 - 30 31 - 43 44 - 56 ≥57 126 54 19 5 361 169 66 20 1.4 (0.5, 3.7) 1.2 (0.4 - 3.6) 0.38 (0.38, 3.4) 1 (-) Marital status Married Sin g le* 1 27 77 404 212 1 (-) 1.3 (0.5, 3.4) Religion Christian# Mu s lim 1 78 26 500 116 1.5 (0.9, 2.4) 1 (-) Level of education <primary ≥primary 126 78 364 252 1 (-) 0.9 (0.4, 1.5) Household size ≤5 >5 142 62 400 216 1 (-) 1.4 (0.9, 1.9) *P < 0.05; Single*: includes unmarried, divorced and widowed; Christian#: includes Orthodox, Protestant and Catholic . were self-medicated with modern drugs; 5 (8.6%) of them were self-medicated with traditional medicine and the rest 104 (65% ) of the m consulted health care professionals. A total of 82 modern drugs were used for self-medi- cation. Among the modern drugs used for self-medication, the most leading drugs category were antibiotics 27 (33%) and anti-inflammatory analgesics 26 (32%), followed by GIT drugs category 14 (17%), unidentified 4 (5%) drugs because they did not remember drugs but obtained from drug outlets, cough preparations 2 (2%) and others 9 (11%) which comprises of different categories of drugs (Figure 2). 4. Discussions Though the drugs were not offered free of charges from both public (except for fee waiver & exempted health services) and private health care facilities, the study revealed that almost half of the surveyed households head hoarded drugs at their home. This finding is similar to reports from studies conducted in New Guinea, Spain, Pakistan and European countries [13] [17] [29] [30]. However it is less than those reported from study con- ducte d in I ran, Iraq, Tanzania and Sudan where the rates were 82%, 94% ,73% and 97.1% respectively [11] [14] [15] [31] . And it is great er t han thos e re por ted from st ud y conduc ted in Vietna m and Turke y [18] [32] . T he high prevalence of drug hoarding in our study might be attributed to less controlled distribution of drugs and the presence of a large number of drug outlets dispensing drugs without prescriptions. The average number of drugs hoarded per household was 1.8, which may be considered very low in compari- son with other study conducted Iraq which was 14.26 per households but comparable with the studies conducted in Vietna m, Paki stan a nd Turkey [17] [18] [31] [32]. T he variation in numbers of hoarded drugs may be related to socioec onomic factors, cu ltural attit udes, inappr opriate drug use, treatmen t modificatio ns after hosp italizatio n and drug advert ising [4] [11] [31] [33]. Besides aforementioned factors influencing drug hoarding at household level, in present study it was also found that drugs hoarding are significantly associated with residence area and level of education. These associa- tions revealed that peoples who live in urban areas were 1.4 times more likely to store drugs at their home than those who live in rural areas and a higher proportions of peoples who had level of education higher than or equal to primary educations were 1.5 times more likely to hoard drugs at their home than those who had level of edu- cation less than primary education. The urban population was relatively more educated and education increases knowledge of a drug, as they read leaflet and understa nd its merit and d emerits. So those who had level of ed u- cation higher than primary may cease taking drugs prematurely to fear of side effects once symptoms abated or  E. Sado, T. Gedif Figure 2. Pharmacological category of drugs used for self-medication by sur- veyed households’ head in Nekemte town and surrounding rural areas western Ethiopia August, 2012. they may obtain drugs without advice of health care professionals. But the previous study conducted in Addis Ababa showed that drugs hoarding was associated with gender and education [9]. This discrepancy may be re- sulted from the difference in socio-cultural factors of studied population and geographic areas. The study also revealed that 24.9% of households were found to practice drugs sharing within the households or outside households for friends and neighbors. But the previous study conducted in Addis Ababa community showed lower percent (17%) of drug sharing practice [9]. This discrepancy may be associated with relative ac- cessibility of healt h facilities, ti me when the study was conducted, and difference in socio-economical factors of two areas [34]. Similar study conducted in Tanzania showed that drug sharing within family or outside family was practiced by 12% of surveyed households [15] but the study conducted in Sudan showed higher percent (59.3%) of drug exchange among surveyed households [14]. It was found that drug sharing was significantly associated with place of residence. This showed that a higher numbers of households who live in urban areas were 0.31 times less likely to share drugs than those who live in rural areas. This association was in contrast to the pr evious st udy which r eported t hat drug shar ing was assoc iated with sex, age, edu cation and marital status of the households [9]. The prevalence of self-medication with modern medicine was found to be thirty six and this finding is com- parable with the study done in Western Nepal which reported 34.8% self-medication with modern drugs [24]. But it was higher than the reports from studies conducted in Jimma (27.6%) and Pakistan (15%) [17] [27]. The most common reasons why respondents practiced self-medication were the previous experience with the drugs and relatively less cost. Similarly Andualem & Gebre-meriam (2004) in a study conducted in Addis Ababa noted that most of the people who practiced self-diagnosis and self-medication were due to prior experience on drug. Cost as a reason to practice self-medication was also identified in Jima’s study [24]. But the study con- ducted in India showed the main reasons why people practice self-medication i s d ue to easily accessibility [19]. This study also revealed that self-medication with modern drug was significantly associated with age. Ac- cordingly, respondents whose age greater than fifteen were more likely to self-medicate tha n those less t han fi f- teen. This was comparable with study conducted in Nigeria which showed the extent of self-medication with modern drug was associated with age [35]. 5. Conclusion In co ncl us io n s, d r ug hoa r di ng and sha ri ng were p re val e nt amon g house ho l ds in t he st ud ie d a re as. D rug ho a rd in g was significantly associated with residence place and education while drug sharing was significantly associated only with residence place. Self-medication with modern drug was also prevalent in the study areas. These find- ings ind icated that there is a need fo r avoid ing drug hoar ding, dr ug sharing a nd self-medicatio n with antibiotics to minimize of risk of using expired drugs and accidental poisoning; under dose and inappropriate use; and combat antimicrobial resistance respectively.  E. Sado, T. Gedif Acknowledgements Our special than ks go to all the stud y participants for their willin gness to participate, data collector s, Zonal and town administration official s who provide us valuable cooperation during data collection. We would like to ex- tend our acknowledgement to the School of Pharmacy, Addis Ababa University for sponsoring the research. References [1] World Health Organization (2003) What Is Drug Utilization Research and Why Is It Needed: Introduction to Drug Utilization Research. Oslo Press, Oslo . [2] Gama , H. (2008) Drug Utilization Studies. Arq ui v os de Medicina, 22, 69-74. [3] Mishra, P., Dubey, A., Rana, M., Shankar, P., Subish, P., et al. (2005) Drug Utilization with Special Referenc e to An- timicrobials in a Sub Health Post in Western Nepal. Journal of Nepal Health Research Council, 3, 65-69. [4] World Health Organization (2004) How to Investigate the Use of Medicines by Consumers. Universi ty of Amsterdam, Royal Tropical Institute, Amsterdam. [5] Truter, I. (2008) A Review of Drug Utilization Studies and Methodologies. Jordan Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 1, 91-104. [6] Abdulrasool, B., Fahmy, S., Abu-Gharbieh, E. and Ali, H. (2010) Professional Practices and Perception to wards Ra- tional Use of Medici nes Accordi ng to WHO Methodology in United Arab Emirates. http://www.pharmacypractice.org/vol08/pdf/070-076.pdf [7] World Health Organization (1985) The Rational Use of Drugs: Report of the Conference of E xperts. In Promoting Ra- tional Use of Medicines. WHO, Gene va. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s16221e/s16221e.pdf [8] Bhartiy, S., Shinde, M., Nandeshwar, S. and Ti wari, S. (2008) Pattern of Prescr ibing Pr actices in the Madh ya Pradesh, India. Kathmandu University Medical Journal, 6, 55-59. [9] Amare, G., Alemayehu, T., Gedif, T. and Tesfahun, B. (1997) Pattern of Drug Use in Addis Ababa Community. East Africa Medical Journal, 74, 362-367. [10] World Health Organization/DAP (1992) People’s Perceptions and Use of Drugs in Zimbabwe: A Socio-Cultural Re- search Projects. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1992/WHO_DAP_92.7.pdf [11] Asefzadeh, S. and Nassiri-Asl, M. (2009) Drugs at Home in Qazvin, Iran: Community Based Participatory Research. Europea n Journal o f Scientific Research, 32, 42-46. [12] Asefzadeh, S., Asefzadeh, M. and Javadi, H. (2005) Care Management: Adherence to Therapies among Patients at Bu-Alicina Clinic, Qazvin, Iran. Journal of Research in Medical Sciences, 10, 343-348. [13] Kiyingi, K. and Lauwo, J. ( 19 93) D rugs in Home: Danger and Waste. World Health Forum, 14, 381-384. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/whf/1993/vol14no4/WHF_1993_14(4)_p381-384.pdf [14] Yousif, M. (2002) In-Home Drug Storage and Utilization Habits: A Sudanese Study. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 8, 422-431. [15] Temu-Justin, M., Ma kwa ya, C., Mlavwasi, Y., Risha, P. and Leshabar i, M. (2002) Availability and Usage of Drugs at Households Level in Tanzania: Case Stud y in Kinondoni District, Dar es Salaam. The East and Central African Jour- nal of Pharmac e uti c al Sc i e nc e s , 5, 49-54. [16] Haak, H. and Radyowijati, A. (2002) Determinants of Antimicrobial Use in the Developing World Manual. Child Health R esearch Project Special Report Volume 4. http://www.bvsde.paho.org/bvsacd/cd65/amr_vol4.pdf [17] Hussain, S., Ah mad, S., Ashfaq, K., Hameed, A., Malik, F., et al. (2011) Prevalence of Self-Medication and Health- Seeking Behavior in a Developing Country. African Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology, 5, 972-978. [18] Okumura, J., Wakai, S. and Umenai, T. (2002) Drug Utilization and Self-Medication in Rural Communities in Vietnam. Social Science & Medici ne, 54, 1875-1886. [19] Kadri, R., He gde, S., Kudva, A., Achar, A. and Shenoy, S. (2011) Self-Medication with over the Counter Ophthalmic Preparations: Is It Safe? International Journal of Biological & Medical Research, 2, 528-530. [20] Durgawale, P., Phalke, D. and Phalke, V. (2006) Self-Medication Practices in Rural Maharashtra. Indian Journal of Community Medicine, 31, 34-35. http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0970-0218.54933 [21] Gupta, P., Bobhate, P. and Shrivastava, S. (2011) Determinants of Self Medication Practices in an Urban Slum Com- munity. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research, 4, 54-57. [22] Suleman, S., K etsela, A. and Mekonnen, Z. (2009) Assessment of Self-Medicatio n Pract ices in Assend abo Town, Ji m- ma Zone, Southwestern Ethiopia. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 5, 76-81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2008.04.002  E. Sado, T. Gedif [23] Baruzaig, A. and Bashrahil, K. (20 08) Self-Medicat ion: Concep t, Prevalence & Risks i n Mukalla Ci ty (Yemen). Anda- lus for studies & Research es Yemen, 2, 1-15. [24] Kumar, P., Partha, P., Shankar, R., Shenoy, N. and Theodore, A. (2003) A Survey of Drug Use Patterns in Western Nepal. Singapore Medical Journal , 44, 352-356. [25] Andualem, T. and Gebremariam, T. (2004) A Prospective Study on Self Medication Practices and Consumers Drug Knowledge in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop Journal of Health Science, 14, 1-11. [26] Le Grand , A., Hagerzeil, H. an d Haaijer-Ruskam, F. (199 9) In terventi on Resear ch i n Ration al Us e of Drugs: A Revie w. Health Policy and Planning Journal, 14, 89-92. [27] Mariam, A. and Worku, S. (20 03) Practice of Self-Medication in Jimma Town. Ethiop Journal of Health Science, 17, 111-116. [28] WHO (2001) Sampling Methods and Sample Size. In: Omi, S., Ed., Health Research Methodology: A Guide for Trai- ning in Research Methods, Manila, 71-84. [29] Gonzales, J., Orero, A. and P rieto, J. (1997) Antibiotics in Spanish Households, Medical and Socioeconomic Implica- tions. Medicina Clínica, 109, 782-785. [30] Burgerhof, J., Gr i g orya n, L., R u s k a mp, F., M echt ler, R., Deschep per, R., Andrasevic, A., et al. (2006 ) Se lf-Medication with Antimicrobial Drugs in Europe. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 12, 452-459. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1203.050992 [31] Jassim, A. (2010) In-Home Drug Storage and Self Medication with Antimicrobial Drugs in Bisrah, Iraq. Oman Medi- cal Journal, 25, 79-87. http://dx.doi.org/10.5001/omj.2010.25 [32] Aksakal, N., Ilhan, N., Durukan, E., Ilhan, S., Özkan, S. and Bumin, M.A. (2009) Self-Medication with Antibiotics: Questionnaire Survey among Primary Care Center Attendants. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 18, 1150- 1157. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pds.1829 [33] Sachdeva, P. (2010) Drug Utilization Studies—Scope and Futu re Persp ectives. International Journal on Pharmaceuti- cal and Biological Research, 1, 11-17. [34] Gedif, T. an d Hahn, H. (2003) The Use of Medicinal Plants in Self-Care in Rural Central E thiopia. Journal of Ethno- pharmacology, 87, 155-161. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0378-8741(03)00109-0 [35] Afolabi, A. (2008) Factors Influencing the Pattern of Self-Medication in an Adult Nigerian Population. Annals of Afri- can Medicine Journal, 7, 120-127. http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/1596-3519.55666

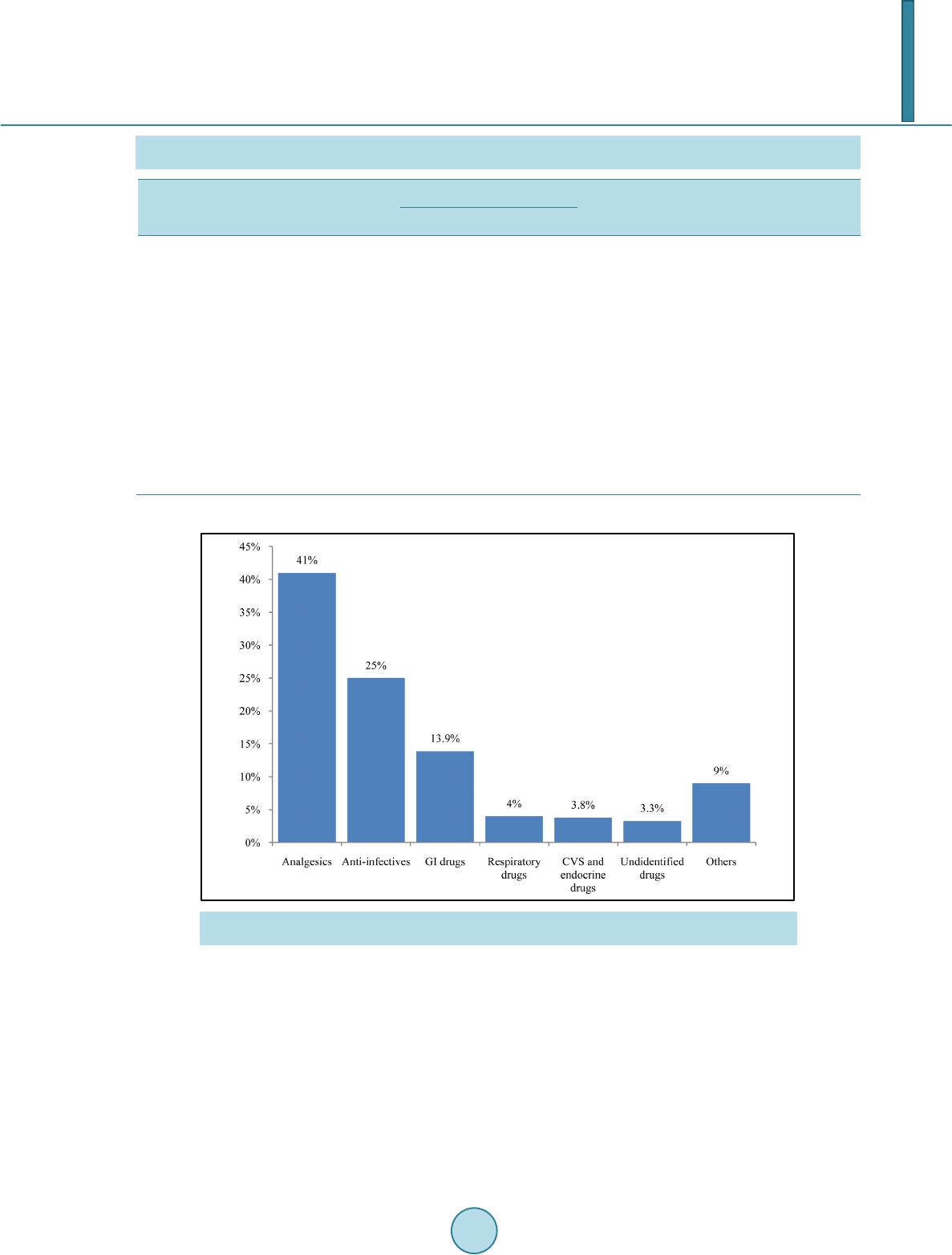

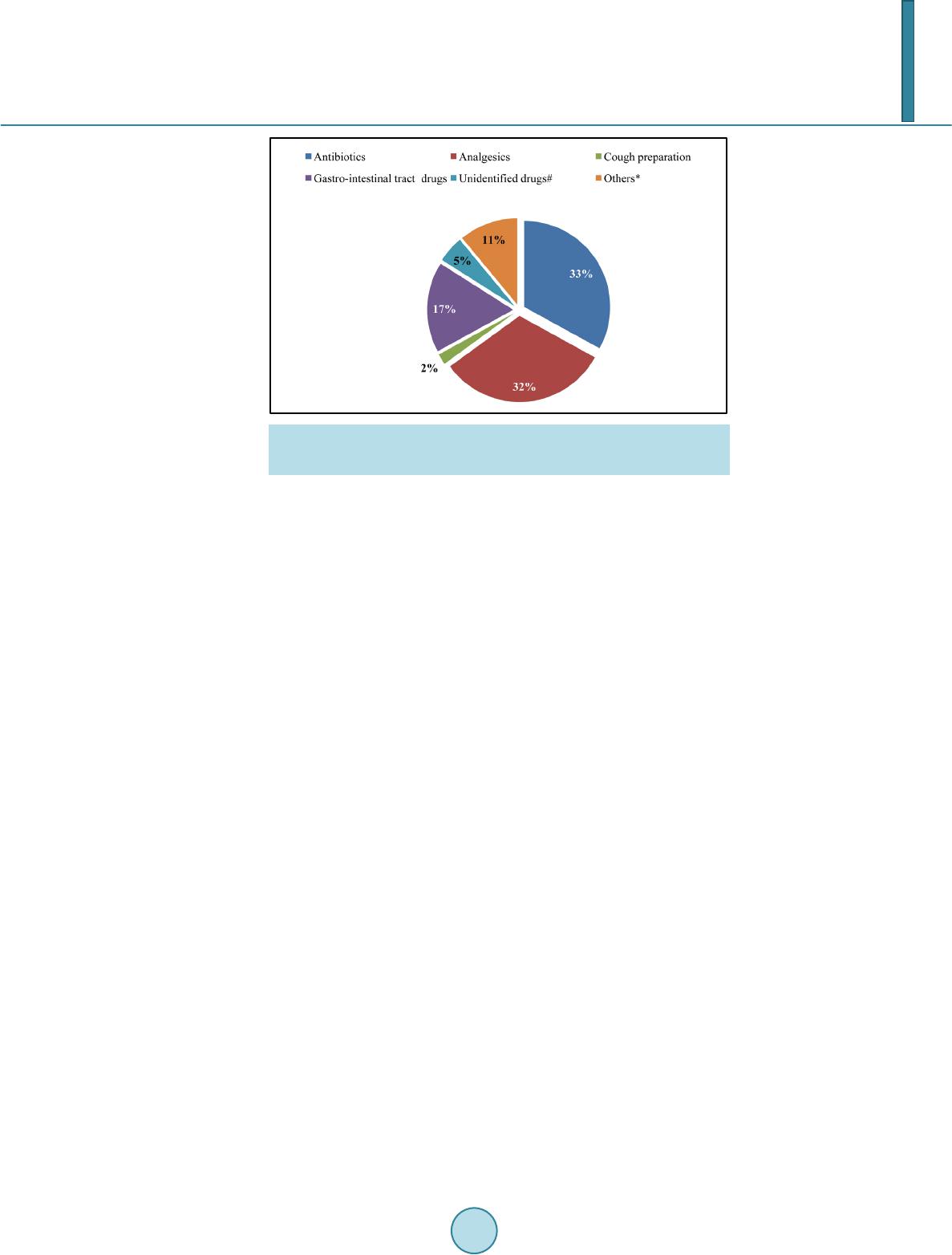

|