Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

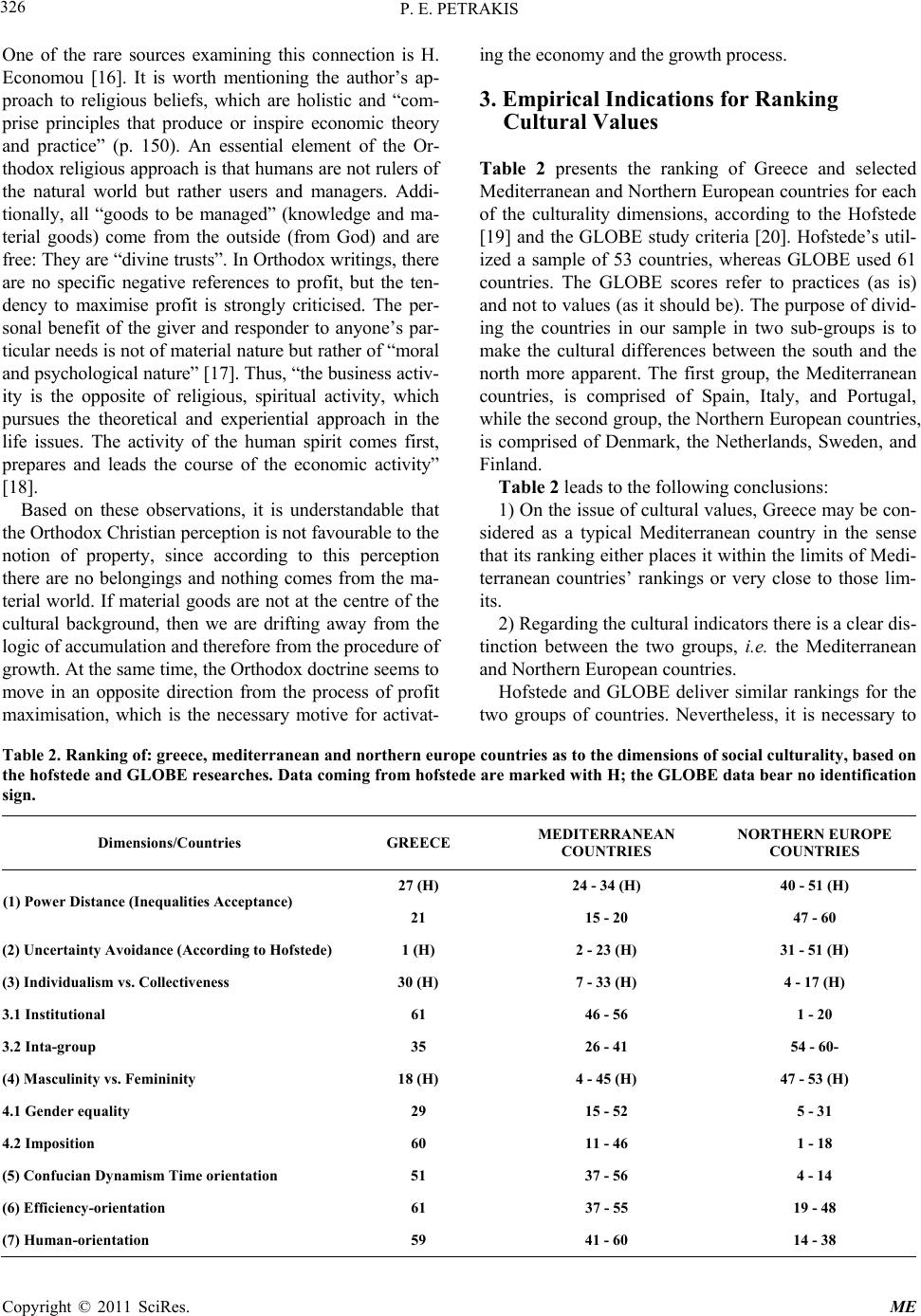

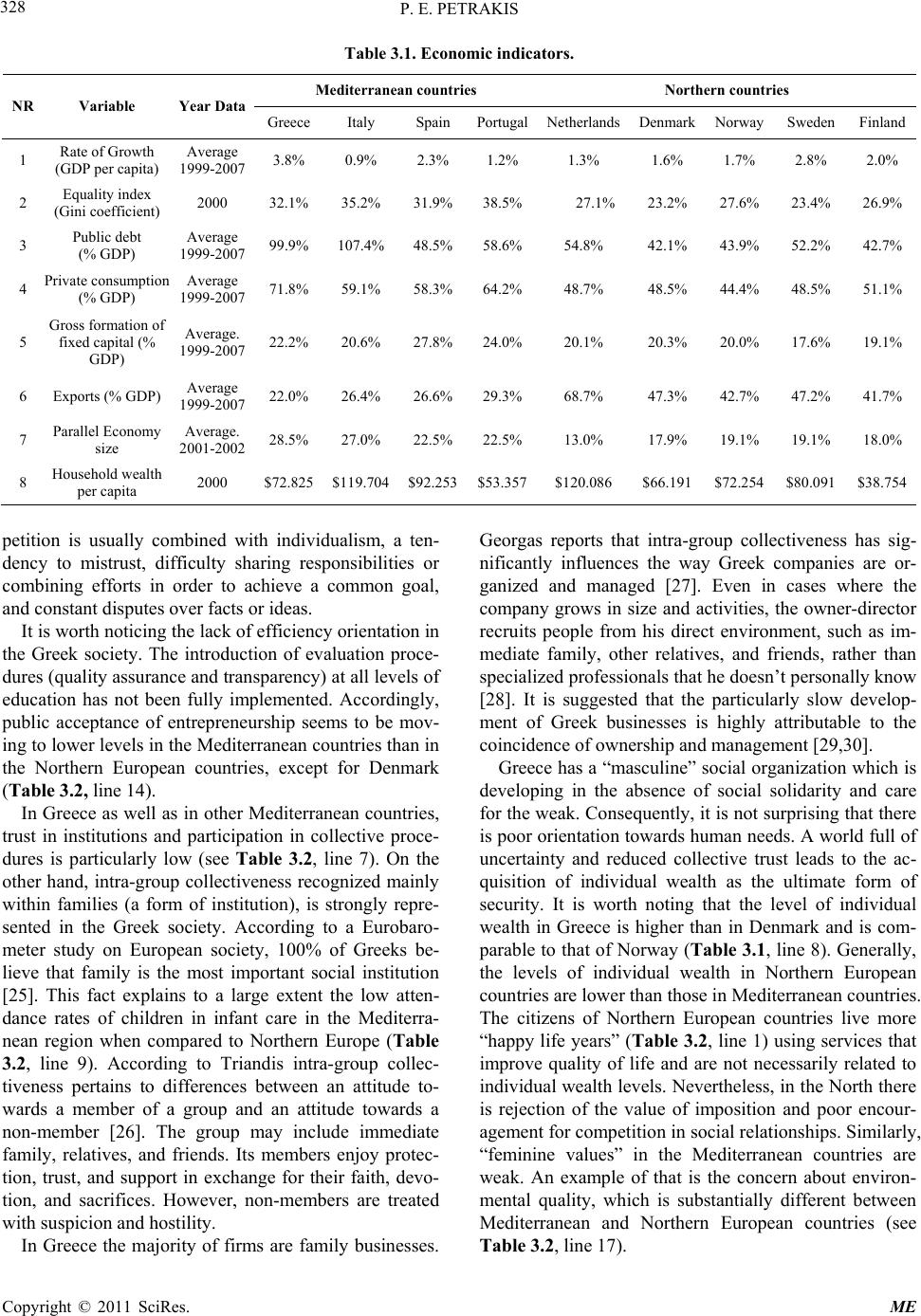

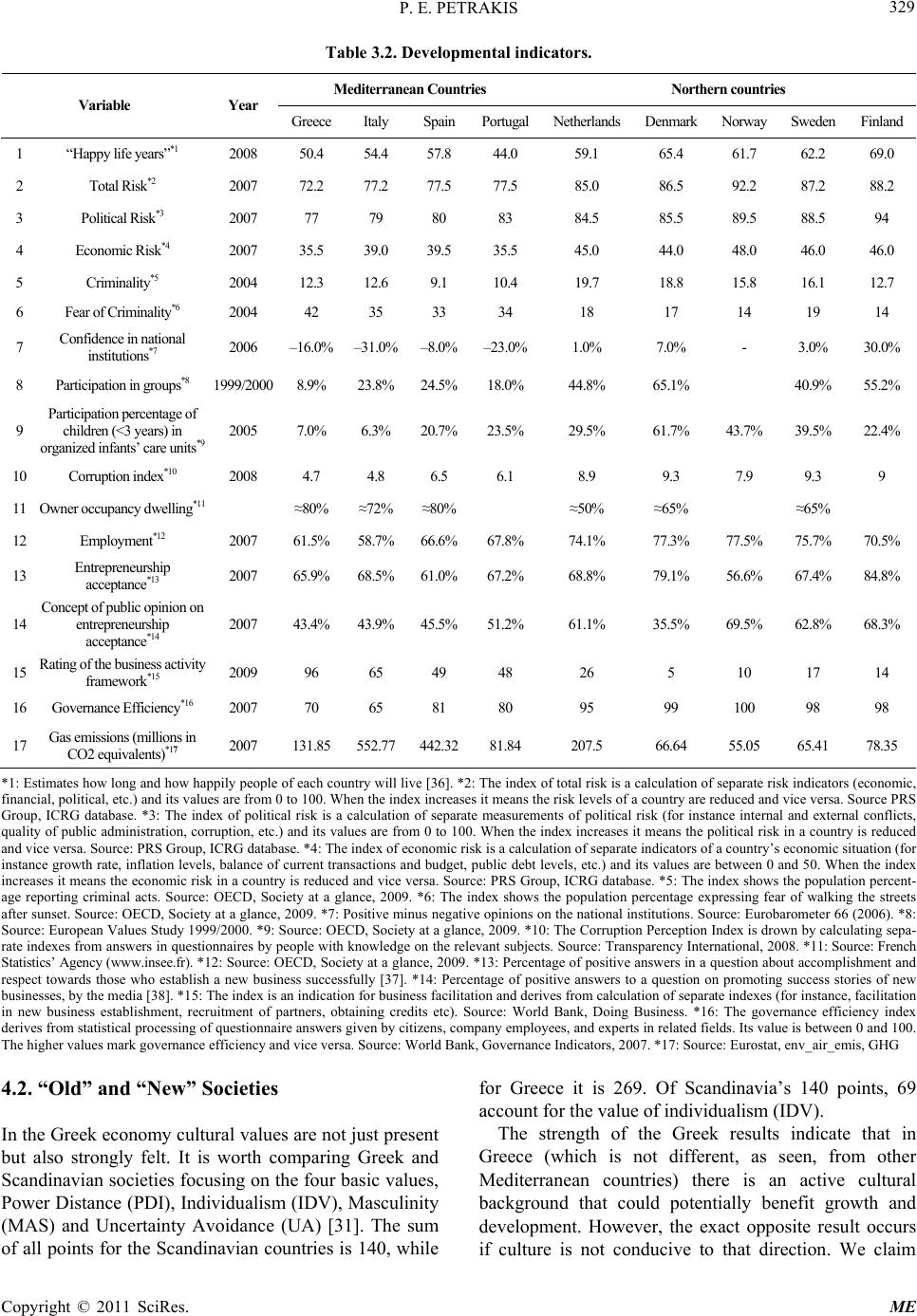

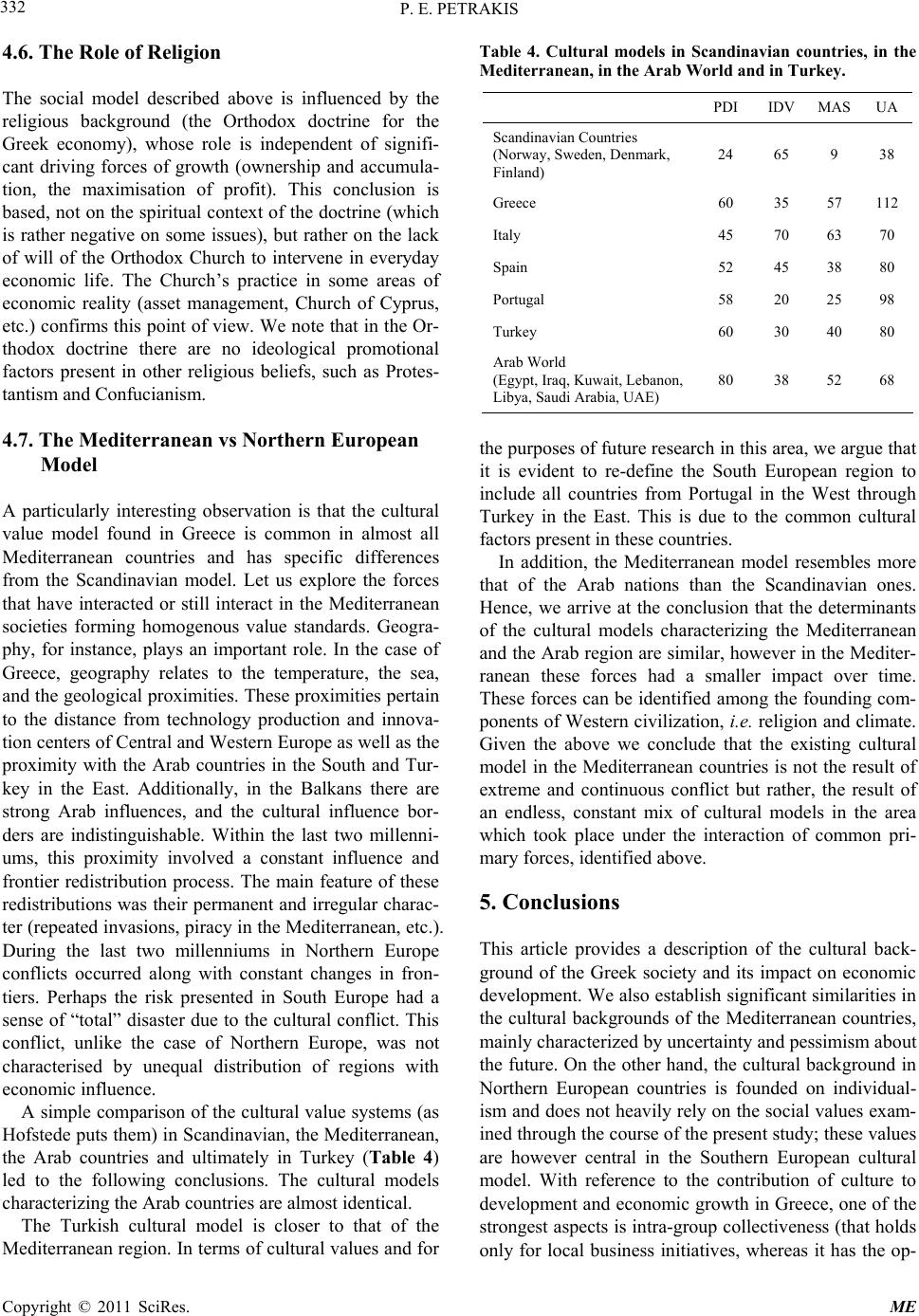

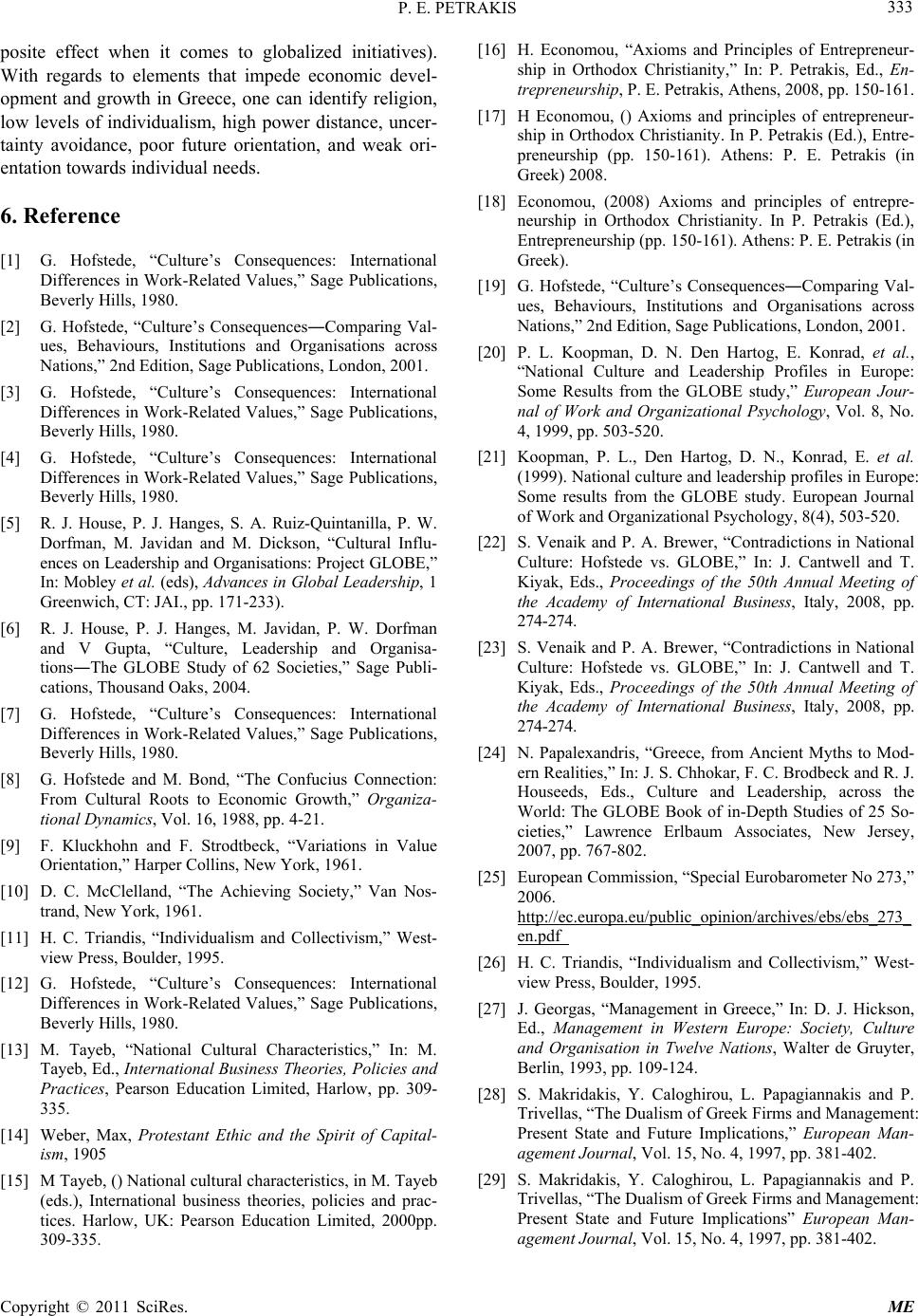

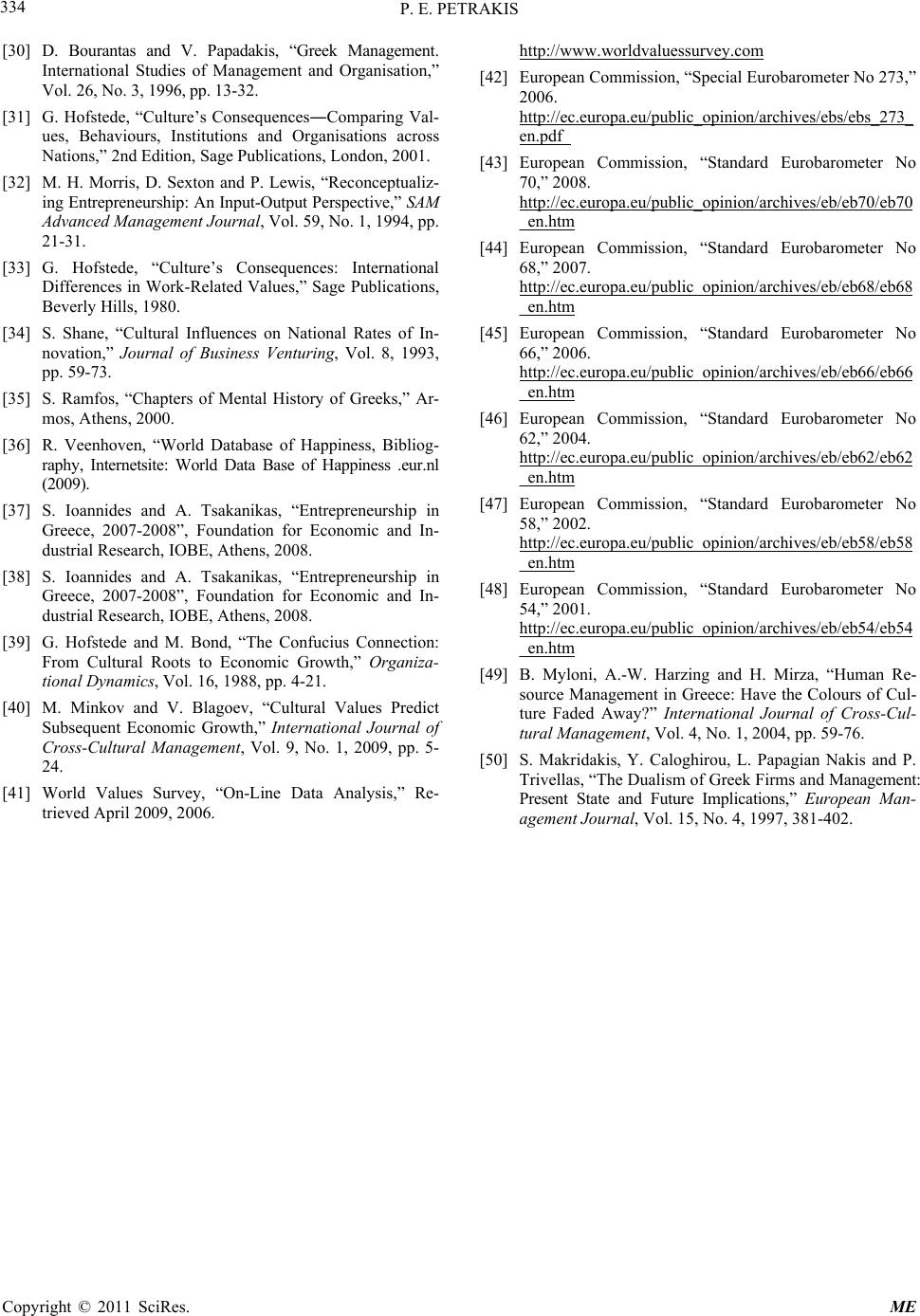

Modern Economy, 2011, 2, 324-334 doi:10.4236/me.2011.23035 Published Online July 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/me) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME Cultural Background and Economic Development Indicators: European South Vs European North P. E. Petrakis Department of Economic Studies, National a nd Ka p odi st ri a n Universi t y of Athens, Athens, Greece E-mail: ppetrakis@econ.uoa.gr Received February 10, 2011; revised April 12, 2011; accepted April 26, 2011 Abstract This paper examines the relationship between cultural background and economic development. We focus on the example of Greece in order to analyze the cultural disparities between the Mediterranean and the North- ern European countries. We find that there is a common cultural model characterizing the Southern European nations, which spans the Mediterranean coast, from Portugal to Turkey. These countries are characterized by high uncertainty and absence of future orientation. On the other hand the cultural background in Northern European countries is found on individualism. The paper shows that the cultural values model is mirrored in the basic traits characterizing the economic and business environment of the areas (North-South) under ex- amination. The differential cultural background is reflected in the basic economic and social developmental indicators in a consistent way. Keywords: Cultural Background, Economic Development, Growth and Culture 1. Introduction Discourse into the role of cultural values in the formation of a society’s economic model, its growth and develop- ment has its roots in the ancient Greek authors in an effort to explain economic reality through human behaviours. The crucial question raised from this discourse is whether the existing social model promotes or deters growth and development and whether its evolution follows a favour- able course for growth. Within the European Union, Southern European coun- tries, and particularly the Greek economy, systematically present macroeconomic characteristics, such as public over-indebting and a greater propensity to consume, that contrast markedly with Scandinavian economies. These characteristics have brought about higher standards of living, however at a future cost; i.e. loss of welfare for the generations to come. Other notable features of these economies are the absence of production and investment initiatives in innovation, high levels of self-employment, etc. A macroeconomic behaviour can be considered irra- tional if certain attributes are not repeated systematically. If certain economic decisions are repeated, they cannot be classified as “mistakes”, since economic agents act “ra- tionally” and are not myopic by assumption. What could be happening in this case is that economists interpret these decisions in the wrong context. In other words, the background information and assumptions made for the purposes of interpreting the macroeconomic environment are not the appropriate ones. Therefore, certain forces within those societies are systematically influential and contribute in the formation of economic phenomena. We speculate that such forces are strongly related with the structure of the specific cultural background and the long-term development model of these societies. This issue is particularly timely after the 2008 financial crisis. The main characteristic of the over-indebted coun- tries that were hit by the crisis is the government inability to aggressively intervene by further increasing the deficit, in order to cover the “potential production gap”. The study of economic forces deriving from cultural values cannot help form short-term intervention schemes, since cultural norms are shaped under long-run influences. Thus, a deeper understanding of those cultural values is necessary for the assessment of the efficacy of short-term policy goals and the elaboration of an efficient long-term development strategy. The rest of the article proceeds as follows: Section 2 discusses the cultural dimensions that we are focusing on, in this paper. Section 3 presents some preliminary evi- dence for the cultural differences between Northern and Southern European countries. Section 4 presents, in detail,  P. E. PETRAKIS325 the dominating cultural model in the Greek society. Last, Section 5 concludes. 2. Context of Culturality Hofstede contributes to the valuatory, international com- parative research literature in the following way [1,2]. He comes up with a set of values which can be used to meas- ure a country’s cultural background. Hofstede argues that these valuatory dimensions describe humanity’s problems, present in all societies [3]. Countries have different scores per dimension demonstrating that various societies handle these problems differently. Hofstede identifies four di- mensions, which pertain to: power distance (i.e. the ac- ceptance of inequalities), uncertainty avoidance, indivi- dualism in opposition to collectiveness, and masculinity in opposition to femininity [4]. The Global Leadership and Organizational Effective- ness (GLOBE) study, conducted in the mid 1990s, adds to Hofstede’s culture dimensions [5,6]. This research aims to explore the relationship between social culture, organ- isational culture and practice, and organisational leader- ship. The GLOBE study establishes nine dimensions of social culture that reflect society perceptions of me- dium-ranged managers, and their preferences on desired social traits. These dimensions are: power distance, un- certainty avoidance, institutional collectiveness (Collec- tiveness I), intra-group collectiveness (Collectiveness II), gender equality, imposition, future orientation, effective- ness orientation, and human orientation. Those dimen- sions resulted from bibliographic research on a vast sam- ple of studies on culture measurement and the existing intercultural theory [7-11]. Table 1 presents the dimensions of social culturality in light of existing research. The dimensions described in points 1 through 4, derive from Hofstede’s respective di- mensions [12]. The first three correspond to power dis- tance, uncertainty avoidance, and individualism respec- tively. Point 4 relates to the dimension of masculinity. In Table 1, the role of religious background is mentioned as a separate dimension. Religious background is not a dif- ferent value per se, since its influence expands over the whole valuatory background. However, it is addressed here due to lack of in depth examination and analysis of religion within the Greek society. Many researchers have concluded that religion creates and influences personal values and mentalities [13]. For instance, according to Weber [14], individualism, prefer- ence in personal choice and autonomy, and pursuing per- sonal objectives are distinct features of Protestantism. By contrast, Confucianism is family- and group-oriented, shows respect for age and hierarchy, prefers harmony, and avoids conflicts and competition. According to Weber, the Protestant “moral” plays a significant role, since it emphasises the tireless, endless acquisition of goods that was developed in some areas of Protestant Europe. Weber argues that Protestantism is the cradle of the modern economic person and that Calvinism, in particular, has accentuated individualism, personal potential, and initiative. Even though modern capitalism was the result of the social structure in the Western world, it would have been inconceivable without Calvinism’s contribution to freeing the acquisition of goods from the restrictions of tradi- tional morality [15]. The connection between cultural values, stemming from the influence of the Orthodox Christian doctrine, dominating roughly 90% of the population of Greece and other Balkan countries for almost two millenniums, and economic activity has not been sufficiently examined. Table 1. Dimensions of social culturality. (1) Power distance (Acceptance of Inequalities) (2) Uncertainty Avoidance (3) Individualism vs Collectiveness (3.1) Institutional Collectiveness (Collectiveness Ι) (3.2) Intra-group Collectiveness (Collectiveness ΙΙ) (4) Masculinity vs Femininity (4.1) Gender equality (4.2)Imposition (5) Confucian Dynamism/ Future Orientation (6) Efficiency- orientation (7) Human orientation (8) The role of Religion Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  P. E. PETRAKIS Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 326 One of the rare sources examining this connection is H. Economou [16]. It is worth mentioning the author’s ap- proach to religious beliefs, which are holistic and “com- prise principles that produce or inspire economic theory and practice” (p. 150). An essential element of the Or- thodox religious approach is that humans are not rulers of the natural world but rather users and managers. Addi- tionally, all “goods to be managed” (knowledge and ma- terial goods) come from the outside (from God) and are free: They are “divine trusts”. In Orthodox writings, there are no specific negative references to profit, but the ten- dency to maximise profit is strongly criticised. The per- sonal benefit of the giver and responder to anyone’s par- ticular needs is not of material nature but rather of “moral and psychological nature” [17]. Thus, “the business activ- ity is the opposite of religious, spiritual activity, which pursues the theoretical and experiential approach in the life issues. The activity of the human spirit comes first, prepares and leads the course of the economic activity” [18]. Based on these observations, it is understandable that the Orthodox Christian perception is not favourable to the notion of property, since according to this perception there are no belongings and nothing comes from the ma- terial world. If material goods are not at the centre of the cultural background, then we are drifting away from the logic of accumulation and therefore from the procedure of growth. At the same time, the Orthodox doctrine seems to move in an opposite direction from the process of profit maximisation, which is the necessary motive for activat- ing the economy and the growth process. 3. Empirical Indications for Ranking Cultural Values Table 2 presents the ranking of Greece and selected Mediterranean and Northern European countries for each of the culturality dimensions, according to the Hofstede [19] and the GLOBE study criteria [20]. Hofstede’s util- ized a sample of 53 countries, whereas GLOBE used 61 countries. The GLOBE scores refer to practices (as is) and not to values (as it should be). The purpose of divid- ing the countries in our sample in two sub-groups is to make the cultural differences between the south and the north more apparent. The first group, the Mediterranean countries, is comprised of Spain, Italy, and Portugal, while the second group, the Northern European countries, is comprised of Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Finland. Table 2 leads to the following conclusions: 1) On the issue of cultural values, Greece may be con- sidered as a typical Mediterranean country in the sense that its ranking either places it within the limits of Medi- terranean countries’ rankings or very close to those lim- its. 2) Regarding the cultural indicators there is a clear dis- tinction between the two groups, i.e. the Mediterranean and Northern European countries. Hofstede and GLOBE deliver similar rankings for the two groups of countries. Nevertheless, it is necessary to Table 2. Ranking of: greece, me diterr anean and northern europe countries as to the dimensions of social culturality, based on the hofstede and GLOBE researches. Data coming from hofstede are marked with H; the GLOBE data bear no identification sign. Dimensions/Countries GREECE MEDITERRANEAN COUNTRIES NORTHERN EUROPE COUNTRIES 27 (H) 24 - 34 (H) 40 - 51 (H) (1) Power Distance (Inequalities Acceptance) 21 15 - 20 47 - 60 (2) Uncertainty Avoidance (According to Hofstede) 1 (H) 2 - 23 (H) 31 - 51 (H) (3) Individualism vs. Collectiveness 30 (H) 7 - 33 (H) 4 - 17 (H) 3.1 Institutional 61 46 - 56 1 - 20 3.2 Inta-group 35 26 - 41 54 - 60- (4) Masculinity vs. Femininity 18 (H) 4 - 45 (H) 47 - 53 (H) 4.1 Gender equality 29 15 - 52 5 - 31 4.2 Imposition 60 11 - 46 1 - 18 (5) Confucian Dynamism Time orientation 51 37 - 56 4 - 14 (6) Efficiency-orientation 61 37 - 55 19 - 48 (7) Human-orientation 59 41 - 60 14 - 38  P. E. PETRAKIS Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 327 comment on the ranking for the uncertainty avoidance dimension. The GLOBE research presents several dif- ferent results on the uncertainty avoidance dimension when compared to Hofstede’s findings: Mediterranean countries have a lower ranking, implying lower uncer- tainty avoidance levels. The explanation might lie in the fact that Hofstede did not include Central and Eastern European countries in his sample. Additionally, the two studies used different measurement means in order to render this dimension operational [21]. Veneik and Brewer report 14 correlations between Hofstede’s and GLOBE’s measures of cultural values [22]: five vari- ables are statistically significant and bear the expected sign (positive), eight bear the expected sign but are not statistically significant, and for one (uncertainty avoid- ance) there is a large negative and statistically significant correlation between the two measurement ways, which is strongly unexpectes. These two studies are similar in the social culturality dimensions they develop, except for “uncertainty avoidance”. Generally, the two studies are similar in the rankings they create between societies, except for the “uncertainty avoidance” dimension. Ve- neik and Brewer are also concerned with this issue and in particular with the disparate findings for Greece and Portugal [23]. They base their interpretation of these disparities on the time difference (two decades) between the two studies. However, this interpretation does not sound convincing due to the slow pace characterizing behavioural and cultural changes. The authors rightly note that the two studies measure opposing concepts. This is due to the nature of the questions of the surveys themselves. The present study adopts Hofstede’s meas- urement of “uncertainty avoidance” because it is com- patible with the risk measurements (see Table 3.2, lines 2, 3 and 4) which prove that the Mediterranean countries have always been characterized by systematically higher risk levels. This fact justifies the formation of chronic risk avoidance behaviours. The model of cultural values formed in the two groups of countries is roughly the following: Mediterranean countries accept more widely the existence of greater inequalities and (according to Hofstede) and demonstrate higher rates of uncertainty, when compared to Northern European countries. Individual achievements are not highly appreciated and at the same time the socially es- tablished organization rules and practices are not ac- ceptable. Nevertheless, individuals express pride, faith, and cohesion with their families and any specific social group they belong to. Feminine values, such as quality of life, care for the weak, and solidarity play a small part and are characteristic features of Northern European countries. Accordingly, the values of imposition and of dispute do not seem to prevail. The Mediterranean countries examined here are char- acterized by limited future orientation, lack of scheduling and long-term planning and portray low efficiency and human orientation levels while their main focus is on short-term planning. 4. Synthesis on the Cultural Model of Greek Society and Economy Greece exhibits sociocultural traits similar to those of other Mediterranean countries. The formation of a social model for the Mediterranean as well as for Scandinavia is primarily based on common elements shared by the members of each group of countries (geography, evolu- tion, history, etc.). 4.1. Basic Description of the Model The cultural model of Greece consists of a synthesis of priorities. Despite the existence of a high degree of ine- quality in areas such as wealth, revenue, and power in Greece, the general feeling is disapproving of inequali- ties. It is characteristic that the GINI indicator (Table 3.1, line 2) for Greece, and the Mediterranean countries in general, is significantly higher (indicating a more un- equal distribution) compared to that of the Northern European countries. The degree of uncertainty avoidance is high, while the risk levels experienced by the social model are also large. It is worth mentioning that all risk indicators―total risk, political risk, and economic risk (Table 3.2, lines 2, 3, 4)―are higher (lower indexes) in the Mediterranean countries than the Northern European countries. In addi- tion, fear of crime is much more intense in Mediterra- nean countries (see Table 3.2, lines 6, 7), compared to Scandinavia, although Mediterranean countries experi- ence considerably lower crime rates. Fear of crime has an inverse prevalence, demonstrating that these countries “are worried” and “scared” about the present and the future. Regarding future-orientation rankings, Greece is in the 51st place, a considerably low point among the 61 coun- tries included in the sample. This fact points to poor use of long-term planning. This implies that in general, there is a short-term perspective in the country and poor use of programming and long-term planning. The individualiza- tion of effort and the value of individual achievements are of low priority. The society does not encourage or reward its members adequately or according to their performance, while other indicators show that Greeks point to the need for wider recognition. According to Papalexandris there is a general trend of mistrust in indi- vidual achievements and highuccess levels [24]. Com- s  P. E. PETRAKIS 328 Table 3.1. Economic indicators. Mediterranean countries Northern countries NR Variable Year Data Greece Italy Spain PortugalNetherlandsDenmark Norway SwedenFinland 1 Rate of Growth (GDP per capita) Average 1999-2007 3.8% 0.9% 2.3% 1.2% 1.3% 1.6% 1.7% 2.8% 2.0% 2 Equality index (Gini coefficient) 2000 32.1% 35.2% 31.9%38.5% 27.1% 23.2% 27.6% 23.4% 26.9% 3 Public debt (% GDP) Average 1999-2007 99.9% 107.4%48.5%58.6% 54.8% 42.1% 43.9% 52.2% 42.7% 4 Private consumption (% GDP) Average 1999-2007 71.8% 59.1% 58.3%64.2% 48.7% 48.5% 44.4% 48.5% 51.1% 5 Gross formation of fixed capital (% GDP) Average. 1999-2007 22.2% 20.6% 27.8%24.0% 20.1% 20.3% 20.0% 17.6% 19.1% 6 Exports (% GDP) Average 1999-2007 22.0% 26.4% 26.6%29.3% 68.7% 47.3% 42.7% 47.2% 41.7% 7 Parallel Economy size Average. 2001-2002 28.5% 27.0% 22.5%22.5% 13.0% 17.9% 19.1% 19.1% 18.0% 8 Household wealth per capita 2000 $72.825 $119.704$92.253$53.357$120.086 $66.191$72.254 $80.091$38.754 petition is usually combined with individualism, a ten- dency to mistrust, difficulty sharing responsibilities or combining efforts in order to achieve a common goal, and constant disputes over facts or ideas. It is worth noticing the lack of efficiency orientation in the Greek society. The introduction of evaluation proce- dures (quality assurance and transparency) at all levels of education has not been fully implemented. Accordingly, public acceptance of entrepreneurship seems to be mov- ing to lower levels in the Mediterranean countries than in the Northern European countries, except for Denmark (Table 3.2, line 14). In Greece as well as in other Mediterranean countries, trust in institutions and participation in collective proce- dures is particularly low (see Table 3.2, line 7). On the other hand, intra-group collectiveness recognized mainly within families (a form of institution), is strongly repre- sented in the Greek society. According to a Eurobaro- meter study on European society, 100% of Greeks be- lieve that family is the most important social institution [25]. This fact explains to a large extent the low atten- dance rates of children in infant care in the Mediterra- nean region when compared to Northern Europe (Table 3.2, line 9). According to Triandis intra-group collec- tiveness pertains to differences between an attitude to- wards a member of a group and an attitude towards a non-member [26]. The group may include immediate family, relatives, and friends. Its members enjoy protec- tion, trust, and support in exchange for their faith, devo- tion, and sacrifices. However, non-members are treated with suspicion and hostility. In Greece the majority of firms are family businesses. Georgas reports that intra-group collectiveness has sig- nificantly influences the way Greek companies are or- ganized and managed [27]. Even in cases where the company grows in size and activities, the owner-director recruits people from his direct environment, such as im- mediate family, other relatives, and friends, rather than specialized professionals that he doesn’t personally know [28]. It is suggested that the particularly slow develop- ment of Greek businesses is highly attributable to the coincidence of ownership and management [29,30]. Greece has a “masculine” social organization which is developing in the absence of social solidarity and care for the weak. Consequently, it is not surprising that there is poor orientation towards human needs. A world full of uncertainty and reduced collective trust leads to the ac- quisition of individual wealth as the ultimate form of security. It is worth noting that the level of individual wealth in Greece is higher than in Denmark and is com- parable to that of Norway (Table 3.1, line 8). Generally, the levels of individual wealth in Northern European countries are lower than those in Mediterranean countries. The citizens of Northern European countries live more “happy life years” (Table 3.2 , line 1) using services that improve quality of life and are not necessarily related to individual wealth levels. Nevertheless, in the North there is rejection of the value of imposition and poor encour- agement for competition in social relationships. Similarly, “feminine values” in the Mediterranean countries are weak. An example of that is the concern about environ- mental quality, which is substantially different between Mediterranean and Northern European countries (see Table 3.2, line 17). Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  P. E. PETRAKIS329 Table 3.2. Developmental indicators. Mediterranean Countries Northern countries Variable Year Greece Italy Spain PortugalNetherlandsDenmark Norway SwedenFinland 1 “Happy life years”*1 2008 50.4 54.4 57.8 44.0 59.1 65.4 61.7 62.2 69.0 2 Total Risk*2 2007 72.2 77.2 77.5 77.5 85.0 86.5 92.2 87.2 88.2 3 Political Risk*3 2007 77 79 80 83 84.5 85.5 89.5 88.5 94 4 Economic Risk*4 2007 35.5 39.0 39.5 35.5 45.0 44.0 48.0 46.0 46.0 5 Criminality*5 2004 12.3 12.6 9.1 10.4 19.7 18.8 15.8 16.1 12.7 6 Fear of Criminality*6 2004 42 35 33 34 18 17 14 19 14 7 Confidence in national institutions*7 2006 –16.0% –31.0%–8.0% –23.0% 1.0% 7.0% - 3.0% 30.0% 8 Participation in groups*8 1999/2000 8.9% 23.8% 24.5% 18.0% 44.8% 65.1% 40.9% 55.2% 9 Participation percentage of children (<3 years) in organized infants’ care units*9 2005 7.0% 6.3% 20.7% 23.5% 29.5% 61.7% 43.7% 39.5% 22.4% 10 Corruption index*10 2008 4.7 4.8 6.5 6.1 8.9 9.3 7.9 9.3 9 11 Owner occupancy dwelling*11 ≈80% ≈72% ≈80% ≈50% ≈65% ≈65% 12 Employment*12 2007 61.5% 58.7% 66.6% 67.8% 74.1% 77.3% 77.5% 75.7% 70.5% 13 Entrepreneurship acceptance*13 2007 65.9% 68.5% 61.0% 67.2% 68.8% 79.1% 56.6% 67.4% 84.8% 14 Concept of public opinion on entrepreneurship acceptance*14 2007 43.4% 43.9% 45.5% 51.2% 61.1% 35.5% 69.5% 62.8% 68.3% 15 Rating of the business activity framework*15 2009 96 65 49 48 26 5 10 17 14 16 Governance Efficiency*16 2007 70 65 81 80 95 99 100 98 98 17 Gas emissions (millions in CO2 equivalents)*17 2007 131.85 552.77 442.3281.84 207.5 66.64 55.05 65.41 78.35 *1: Estimates how long and how happily people of each country will live [36]. *2: The index of total risk is a calculation of separate risk indicators (economic, financial, political, etc.) and its values are from 0 to 100. When the index increases it means the risk levels of a country are reduced and vice versa. Source PRS Group, ICRG database. *3: The index of political risk is a calculation of separate measurements of political risk (for instance internal and external conflicts, quality of public administration, corruption, etc.) and its values are from 0 to 100. When the index increases it means the political risk in a country is reduced and vice versa. Source: PRS Group, ICRG database. *4: The index of economic risk is a calculation of separate indicators of a country’s economic situation (for instance growth rate, inflation levels, balance of current transactions and budget, public debt levels, etc.) and its values are between 0 and 50. When the index increases it means the economic risk in a country is reduced and vice versa. Source: PRS Group, ICRG database. *5: The index shows the population percent- age reporting criminal acts. Source: OECD, Society at a glance, 2009. *6: The index shows the population percentage expressing fear of walking the streets after sunset. Source: OECD, Society at a glance, 2009. *7: Positive minus negative opinions on the national institutions. Source: Eurobarometer 66 (2006). *8: Source: European Values Study 1999/2000. *9: Source: OECD, Society at a glance, 2009. *10: The Corruption Perception Index is drown by calculating sepa- rate indexes from answers in questionnaires by people with knowledge on the relevant subjects. Source: Transparency International, 2008. *11: Source: French Statistics’ Agency (www.insee.fr). *12: Source: OECD, Society at a glance, 2009. *13: Percentage of positive answers in a question about accomplishment and respect towards those who establish a new business successfully [37]. *14: Percentage of positive answers to a question on promoting success stories of new businesses, by the media [38]. *15: The index is an indication for business facilitation and derives from calculation of separate indexes (for instance, facilitation in new business establishment, recruitment of partners, obtaining credits etc). Source: World Bank, Doing Business. *16: The governance efficiency index derives from statistical processing of questionnaire answers given by citizens, company employees, and experts in related fields. Its value is between 0 and 100. The higher values mark governance efficiency and vice versa. Source: World Bank, Governance Indicators, 2007. *17: Source: Eurostat, env_air_emis, GHG 4.2. “Old” and “New” Societies In the Greek economy cultural values are not just present but also strongly felt. It is worth comparing Greek and Scandinavian societies focusing on the four basic values, Power Distance (PDI), Individualism (IDV), Masculinity (MAS) and Uncertainty Avoidance (UA) [31]. The sum of all points for the Scandinavian countries is 140, while for Greece it is 269. Of Scandinavia’s 140 points, 69 account for the value of individualism (IDV). The strength of the Greek results indicate that in Greece (which is not different, as seen, from other Mediterranean countries) there is an active cultural background that could potentially benefit growth and development. However, the exact opposite result occurs if culture is not conducive to that direction. We claim Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  P. E. PETRAKIS 330 that the societies of the South have a “strong subcon- scious” as “old” societies. On the other hand, northern societies are “new”, lack a firm background, and are therefore more open to cultivation of modern values that provide them a satisfactory level of happiness. It is worth noticing that in the “happy years of life” index (that is the combination of satisfaction with life according to the Gallup World Poll and life expectancy) the Northern European countries have a lead of almost a decade com- pared to the Mediterranean countries (Table 3.2, line 1). 4.3. The Basic Difference between the Two Models The difference between Greece and Scandinavia derives from two values. For Greek society this value is uncer- tainty avoidance, and for Scandinavia it is the importance of individualism. These factors determine the vitality of growth and development processes. Morris et al. connect the dimension of individualism with entrepreneurship [32]. They focus on the concept of individualism in relation to the level of incitement for achievements and the desire to breach the rules con- nected to entrepreneurial action. Hofstede observed equi- valence between economic indicators, such as per capita GDP, and the dimension of individualism [33]. Although the positive correlation between the two is not evidence of causation, societies with a high individualism index and low power distance index present higher economic growth and stronger tendencies for innovation. This fact is also confirmed by Shane [34]. Uncertainty avoidance in practice orients the social model away from entrepreneurship (Table 3.2, line15) but is able to cover survival needs through “secure” em- ployment positions, i.e. in the public sector. It is re- markable that approximately 27.4% (or 1,250,000 work- ers) of the Greek labor force is employed in the public sector, either as permanent employees (60%) or as con- tract servants (40%). Lack of individualisation and rec- ognition of personal achievements are among the most important features of the prevailing cultural values model. Serious discourse regarding the lack of these two values in the Greek society took place between 1995 and 2005. The most crucial contribution to this matter was done by Ramfos in an attempt to relate the value of individualiza- tion with its substitution by the constant reference to the “state entity” [35]. The establishment of the significance of state entity in social conscience should also be attrib- uted to the historical evolution of the neo-Hellenic soci- ety, in combination with high risk levels in the economy. Besides, the acceptance of power distance in the Greek society favours in particular the dominance of the state, in the operation of which the citizens do not bear the direct costs and at the same time are relieved from deci- sion-making responsibilities. These features led to 1) the formation of a strong bureaucratic management (requir- ing multiple approval signatures), 2) the absence of per- sonal responsibility in business successfulness, and 3) lack of methods of control and evaluation of personal activity, that lead to poor efficiency orientation. As a result, Mediterranean countries are rated lower than Northern European countries in governing efficiency (Table 4.2, line 16). At a first glance we observe a controversial correlation between institutional entity and institutional collective- ness, which however, can be intuitively explained in the following way. Lack of strong individualism in the Greek society is not due to its replacement by organized collectiveness (where the person participates with re- sponsibilities), but rather by a transcendent entity (that resembles the divine ownership of the Orthodox doctrine) that acts instead of the person. The existence of such an entity a priori acts as an ob- stacle to the motivation for entrepreneurship in the sense that “it is not needed” and eventually “not approved”, especially when it requires tying up resources for a con- siderable period of time. The second level of individual protection (after the invocation of the state entity) is the promotion of in- tra-group collectiveness, mainly comprising human and social networks. As a cultural value, intra-group collec- tiveness does foster the operation of the labor market because it blocks important work forces. However, at the same time it produces unusual levels of trust and social cohesion. These two values are present in local markets, however remain absent when a market is globalizes. Consequently, the expectation of economic extroversion is confirmed (see Table 3.1, line 4). Individualization and “denial” of institutional collec- tiveness in combination with promotion of “masculinity” (aggressiveness) result in a non-regulated market opera- tion, an example of which is the development of a paral- lel economy and economic delinquency. The Mediterra- nean countries demonstrate higher rates of parallel economy (as a GDP percentage, see Table 3.1, line 5) while the corruption index take lower values (indicating higher corruption levels, see Table 3.2, line 11,) in the Mediterranean countries compared to Northern European countries. 4.4. Time Orientation and the Future Hofstede and Bond showed that the measure of future orientation and of delayed gratification named Confucian Dynamism is positively related to the economic growth of the Asian Tigers from 1968 to 1985 [39]. Dornbusch Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  P. E. PETRAKIS331 et al. comment on the economic miracle of those coun- tries, underlining that hard work, sacrifices, education, savings, and investment relate to economic growth [40]. Societies with members that sacrifice immediate con- sumption for future consumption should experience faster growth. Using the database of the World Values Survey (2006), Minkov and Blagoev point out that cultures demonstrat- ing high savings rates show for the most part small in- terest in entertainment, family, and contribution to their fellow men [41]. The pessimism observed in Greek soci- ety is connected to the lack of future orientation. More specifically, in Greece we observe a strong pessimism for the future, expressed by high percentages of people who think that the economic situation and employment will only deteriorate (55% and 59% respectively) [42]. A study of the Eurobameter data surveys on the European Union public opinion for the years 2001 and 2008 leads to the conclusion that there is a progressively decreasing number of Greek citizens who expect progress in social issues [43-48]. It is extremely difficult to understand whether pessi- mism and the lack of future orientation are related in a causal manner or if the two simply coexist having dif- ferent generating causes. Such a cause would be the so- cial understanding of the potential of the development model, which is limited. Another cause, however, could be the gap between the actual life of a person as com- pared to the perception of the real possibilities at his disposal. It should be noted that this pessimism is also abundant in other Southern European countries and less so in Northern European countries. However, these val- ues evidently drive people away from saving and invest- ing and therefore away from growth, while pushing to- wards consumption (see Table 3.1, line 3). Consumption as a GDP percentage is higher in the Mediterranean countries than in Northern Europe. The lack of future orientation is equivalent to macroeconomic behaviours expressed through political parties and governments as global social perceptions. The constant presence of pub- lic deficits in national accounts implies a strong prefer- ence for the present rather than the future (see Table 3.1, line 2). Public deficit as a percentage of GDP in the Mediterranean countries is higher than in Northern Euro- pean countries. This is another significant drawback of the Greek managerial malpractices due to lack of strate- gic long-term planning [49]. Makridakis et al. argue that the lack of long-term planning is a result of i) increased uncertainty for the future, ii) frequent legislative amendments, and iii) unpredictable facts that force Greek managers to restrict themselves to short-term planning [50]. The lack of future orientation is also obvious in the existence of high uncertainty levels that correlate with the observation that the most preferable investment for Greeks (and for other Southern Europe countries) is to “have a roof over your head”, i.e. to invest in homes. Greece presents one of the highest owner-occupancy dwelling rates in the measurable world (see Table 3.2, line 12). Additionally, in a world of uncertainty and a lack of respect towards institutional collectiveness, and the services provided by this collective entity, it is rea- sonable to make efforts to expand personal wealth as a means to secure the individual and his/her family from the “hostility of the outside world”. 4.5. Self-Employment and Parallel Economy Promotion of self-employment and the lack of creative entrepreneurship are highly related with 1) the degrada- tion of personal achievements, 2) the downgrading of the value of profits in conjunction with the promotion of competitiveness, and 3) the lack of faith in collective work. Self-employment has its roots in the lack of employ- ment opportunities in the public sector, which is usually the first employment choice in the Greek society, as well as the private sector. “Masculinity” is expressed through personal independence that goes along with self-em- ployment. At the same time the individual tackles the risks of the liberal profession using his personal net- works. Consequently, a big proportion of the Greek labor force is self employed (see Table 3.2, line 12). Future uncertainty and the resulting reluctance to tie up capital in business development contributes to higher self-em- ployment levels. From a cultural point of view, the parallel economy expansion results from the coincidence of a number of values. The lack of trust in institutions, combined with the dominance of intra-group collectiveness, and the re- jection of institutional collectiveness play the most sig- nificant role. However, at the same time, an equally im- portant role is played by the poor future orientation, in- cluding the pessimism that prevents tying up resources. In this view, an unwillingness to participate in the cost carried by the society (tax evasion) is acceptable, fol- lowed by the over-indebting of the “other entity” (the state) that maintains the “inexpensive” improvement of the living standard, while increasing the opportunities to expand personal wealth. The parallel market delinquency is cultivated by the masculinity background. Under these circumstances, entrepreneurship develops by “extract- ing” legitimacy from the state entity in a process of con- flict between the two powerful actors (businessmen and the state entity). Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  P. E. PETRAKIS 332 4.6. The Role of Religion The social model described above is influenced by the religious background (the Orthodox doctrine for the Greek economy), whose role is independent of signifi- cant driving forces of growth (ownership and accumula- tion, the maximisation of profit). This conclusion is based, not on the spiritual context of the doctrine (which is rather negative on some issues), but rather on the lack of will of the Orthodox Church to intervene in everyday economic life. The Church’s practice in some areas of economic reality (asset management, Church of Cyprus, etc.) confirms this point of view. We note that in the Or- thodox doctrine there are no ideological promotional factors present in other religious beliefs, such as Protes- tantism and Confucianism. 4.7. The Mediterranean vs Northern European Model A particularly interesting observation is that the cultural value model found in Greece is common in almost all Mediterranean countries and has specific differences from the Scandinavian model. Let us explore the forces that have interacted or still interact in the Mediterranean societies forming homogenous value standards. Geogra- phy, for instance, plays an important role. In the case of Greece, geography relates to the temperature, the sea, and the geological proximities. These proximities pertain to the distance from technology production and innova- tion centers of Central and Western Europe as well as the proximity with the Arab countries in the South and Tur- key in the East. Additionally, in the Balkans there are strong Arab influences, and the cultural influence bor- ders are indistinguishable. Within the last two millenni- ums, this proximity involved a constant influence and frontier redistribution process. The main feature of these redistributions was their permanent and irregular charac- ter (repeated invasions, piracy in the Mediterranean, etc.). During the last two millenniums in Northern Europe conflicts occurred along with constant changes in fron- tiers. Perhaps the risk presented in South Europe had a sense of “total” disaster due to the cultural conflict. This conflict, unlike the case of Northern Europe, was not characterised by unequal distribution of regions with economic influence. A simple comparison of the cultural value systems (as Hofstede puts them) in Scandinavian, the Mediterranean, the Arab countries and ultimately in Turkey (Table 4) led to the following conclusions. The cultural models characterizing the Arab countries are almost identical. The Turkish cultural model is closer to that of the Mediterranean region. In terms of cultural values and for Table 4. Cultural models in Scandinavian countries, in the Mediterranean, in the Arab World and in Turkey. PDI IDV MASUA Scandinavian Countries (Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Finland) 24 65 9 38 Greece 60 35 57 112 Italy 45 70 63 70 Spain 52 45 38 80 Portugal 58 20 25 98 Turkey 60 30 40 80 Arab World (Egypt, Iraq, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Saudi Arabia, UAE) 80 38 52 68 the purposes of future research in this area, we argue that it is evident to re-define the South European region to include all countries from Portugal in the West through Turkey in the East. This is due to the common cultural factors present in these countries. In addition, the Mediterranean model resembles more that of the Arab nations than the Scandinavian ones. Hence, we arrive at the conclusion that the determinants of the cultural models characterizing the Mediterranean and the Arab region are similar, however in the Mediter- ranean these forces had a smaller impact over time. These forces can be identified among the founding com- ponents of Western civilization, i.e. religion and climate. Given the above we conclude that the existing cultural model in the Mediterranean countries is not the result of extreme and continuous conflict but rather, the result of an endless, constant mix of cultural models in the area which took place under the interaction of common pri- mary forces, identified above. 5. Conclusions This article provides a description of the cultural back- ground of the Greek society and its impact on economic development. We also establish significant similarities in the cultural backgrounds of the Mediterranean countries, mainly characterized by uncertainty and pessimism about the future. On the other hand, the cultural background in Northern European countries is founded on individual- ism and does not heavily rely on the social values exam- ined through the course of the present study; these values are however central in the Southern European cultural model. With reference to the contribution of culture to development and economic growth in Greece, one of the strongest aspects is intra-group collectiveness (that holds only for local business initiatives, whereas it has the op- Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  P. E. PETRAKIS333 posite effect when it comes to globalized initiatives). With regards to elements that impede economic devel- opment and growth in Greece, one can identify religion, low levels of individualism, high power distance, uncer- tainty avoidance, poor future orientation, and weak ori- entation towards individual needs. 6. Reference [1] G. Hofstede, “Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values,” Sage Publications, Beverly Hills, 1980. [2] G. Hofstede, “Culture’s Consequences―Comparing Val- ues, Behaviours, Institutions and Organisations across Nations,” 2nd Edition, Sage Publications, London, 2001. [3] G. Hofstede, “Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values,” Sage Publications, Beverly Hills, 1980. [4] G. Hofstede, “Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values,” Sage Publications, Beverly Hills, 1980. [5] R. J. House, P. J. Hanges, S. A. Ruiz-Quintanilla, P. W. Dorfman, M. Javidan and M. Dickson, “Cultural Influ- ences on Leadership and Organisations: Project GLOBE,” In: Mobley et al. (eds), Advances in Global Leadership, 1 Greenwich, CT: JAI., pp. 171-233). [6] R. J. House, P. J. Hanges, M. Javidan, P. W. Dorfman and V Gupta, “Culture, Leadership and Organisa- tions―The GLOBE Study of 62 Societies,” Sage Publi- cations, Thousand Oaks, 2004. [7] G. Hofstede, “Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values,” Sage Publications, Beverly Hills, 1980. [8] G. Hofstede and M. Bond, “The Confucius Connection: From Cultural Roots to Economic Growth,” Organiza- tional Dynamics, Vol. 16, 1988, pp. 4-21. [9] F. Kluckhohn and F. Strodtbeck, “Variations in Value Orientation,” Harper Collins, New York, 1961. [10] D. C. McClelland, “The Achieving Society,” Van Nos- trand, New York, 1961. [11] H. C. Triandis, “Individualism and Collectivism,” West- view Press, Boulder, 1995. [12] G. Hofstede, “Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values,” Sage Publications, Beverly Hills, 1980. [13] M. Tayeb, “National Cultural Characteristics,” In: M. Tayeb, Ed., International Business Theories, Policies and Practices, Pearson Education Limited, Harlow, pp. 309- 335. [14] Weber, Max, Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capital- ism, 1905 [15] M Tayeb, () National cultural characteristics, in M. Tayeb (eds.), International business theories, policies and prac- tices. Harlow, UK: Pearson Education Limited, 2000pp. 309-335. [16] H. Economou, “Axioms and Principles of Entrepreneur- ship in Orthodox Christianity,” In: P. Petrakis, Ed., En- trepreneurship, P. E. Petrakis, Athens, 2008, pp. 150-161. [17] H Economou, () Axioms and principles of entrepreneur- ship in Orthodox Christianity. In P. Petrakis (Ed.), Entre- preneurship (pp. 150-161). Athens: P. E. Petrakis (in Greek) 2008. [18] Economou, (2008) Axioms and principles of entrepre- neurship in Orthodox Christianity. In P. Petrakis (Ed.), Entrepreneurship (pp. 150-161). Athens: P. E. Petrakis (in Greek). [19] G. Hofstede, “Culture’s Consequences―Comparing Val- ues, Behaviours, Institutions and Organisations across Nations,” 2nd Edition, Sage Publications, London, 2001. [20] P. L. Koopman, D. N. Den Hartog, E. Konrad, et al., “National Culture and Leadership Profiles in Europe: Some Results from the GLOBE study,” European Jour- nal of Work and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 8, No. 4, 1999, pp. 503-520. [21] Koopman, P. L., Den Hartog, D. N., Konrad, E. et al. (1999). National culture and leadership profiles in Europe: Some results from the GLOBE study. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8(4), 503-520. [22] S. Venaik and P. A. Brewer, “Contradictions in National Culture: Hofstede vs. GLOBE,” In: J. Cantwell and T. Kiyak, Eds., Proceedings of the 50th Annual Meeting of the Academy of International Business, Italy, 2008, pp. 274-274. [23] S. Venaik and P. A. Brewer, “Contradictions in National Culture: Hofstede vs. GLOBE,” In: J. Cantwell and T. Kiyak, Eds., Proceedings of the 50th Annual Meeting of the Academy of International Business, Italy, 2008, pp. 274-274. [24] N. Papalexandris, “Greece, from Ancient Myths to Mod- ern Realities,” In: J. S. Chhokar, F. C. Brodbeck and R. J. Houseeds, Eds., Culture and Leadership, across the World: The GLOBE Book of in-Depth Studies of 25 So- cieties,” Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, New Jersey, 2007, pp. 767-802. [25] European Commission, “Special Eurobarometer No 273,” 2006. http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_273_ en.pdf [26] H. C. Triandis, “Individualism and Collectivism,” West- view Press, Boulder, 1995. [27] J. Georgas, “Management in Greece,” In: D. J. Hickson, Ed., Management in Western Europe: Society, Culture and Organisation in Twelve Nations, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, 1993, pp. 109-124. [28] S. Makridakis, Y. Caloghirou, L. Papagiannakis and P. Trivellas, “The Dualism of Greek Firms and Management: Present State and Future Implications,” European Man- agement Journ a l, Vol. 15, No. 4, 1997, pp. 381-402. [29] S. Makridakis, Y. Caloghirou, L. Papagiannakis and P. Trivellas, “The Dualism of Greek Firms and Management: Present State and Future Implications” European Man- agement Journ a l, Vol. 15, No. 4, 1997, pp. 381-402. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  P. E. PETRAKIS Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 334 [30] D. Bourantas and V. Papadakis, “Greek Management. International Studies of Management and Organisation,” Vol. 26, No. 3, 1996, pp. 13-32. [31] G. Hofstede, “Culture’s Consequences―Comparing Val- ues, Behaviours, Institutions and Organisations across Nations,” 2nd Edition, Sage Publications, London, 2001. [32] M. H. Morris, D. Sexton and P. Lewis, “Reconceptualiz- ing Entrepreneurship: An Input-Output Perspective,” SAM Advanced Management Journal, Vol. 59, No. 1, 1994, pp. 21-31. [33] G. Hofstede, “Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values,” Sage Publications, Beverly Hills, 1980. [34] S. Shane, “Cultural Influences on National Rates of In- novation,” Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 8, 1993, pp. 59-73. [35] S. Ramfos, “Chapters of Mental History of Greeks,” Ar- mos, Athens, 2000. [36] R. Veenhoven, “World Database of Happiness, Bibliog- raphy, Internetsite: World Data Base of Happiness .eur.nl (2009). [37] S. Ioannides and A. Tsakanikas, “Entrepreneurship in Greece, 2007-2008”, Foundation for Economic and In- dustrial Research, IOBE, Athens, 2008. [38] S. Ioannides and A. Tsakanikas, “Entrepreneurship in Greece, 2007-2008”, Foundation for Economic and In- dustrial Research, IOBE, Athens, 2008. [39] G. Hofstede and M. Bond, “The Confucius Connection: From Cultural Roots to Economic Growth,” Organiza- tional Dynamics, Vol. 16, 1988, pp. 4-21. [40] M. Minkov and V. Blagoev, “Cultural Values Predict Subsequent Economic Growth,” International Journal of Cross-Cultural Management, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2009, pp. 5- 24. [41] World Values Survey, “On-Line Data Analysis,” Re- trieved April 2009, 2006. http://www.worldvaluessurvey.com [42] European Commission, “Special Eurobarometer No 273,” 2006. http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_273_ en.pdf [43] European Commission, “Standard Eurobarometer No 70,” 2008. http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/eb/eb70/eb70 _en.htm [44] European Commission, “Standard Eurobarometer No 68,” 2007. http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/eb/eb68/eb68 _en.htm [45] European Commission, “Standard Eurobarometer No 66,” 2006. http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/eb/eb66/eb66 _en.htm [46] European Commission, “Standard Eurobarometer No 62,” 2004. http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/eb/eb62/eb62 _en.htm [47] European Commission, “Standard Eurobarometer No 58,” 2002. http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/eb/eb58/eb58 _en.htm [48] European Commission, “Standard Eurobarometer No 54,” 2001. http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/eb/eb54/eb54 _en.htm [49] B. Myloni, A.-W. Harzing and H. Mirza, “Human Re- source Management in Greece: Have the Colours of Cul- ture Faded Away?” International Journal of Cross-Cul- tural Management, Vol. 4, No. 1, 2004, pp. 59-76. [50] S. Makridakis, Y. Caloghirou, L. Papagian Nakis and P. Trivellas, “The Dualism of Greek Firms and Management: Present State and Future Implications,” European Man- agement Journ a l, Vol. 15, No. 4, 1997, 381-402. |