Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

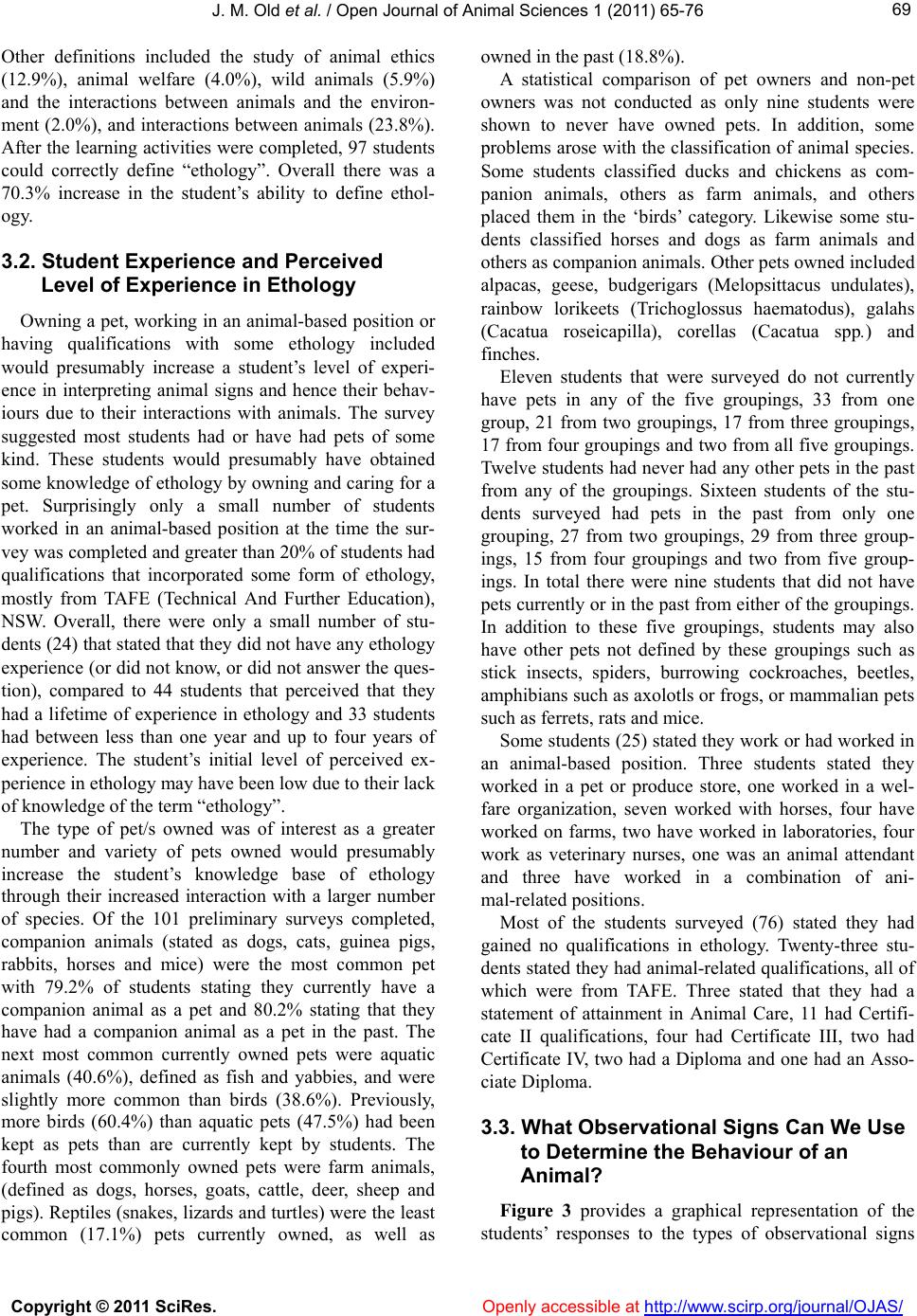

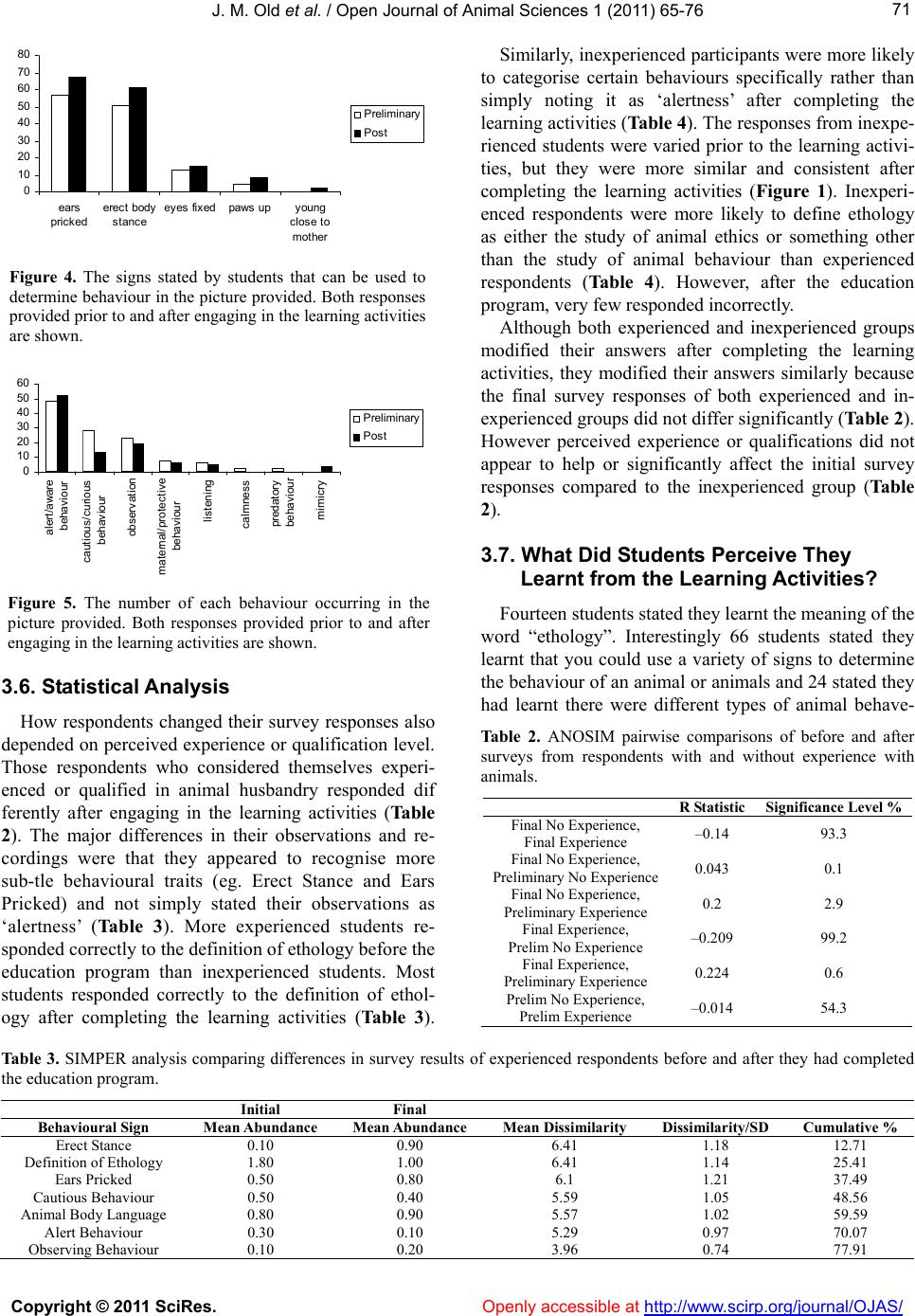

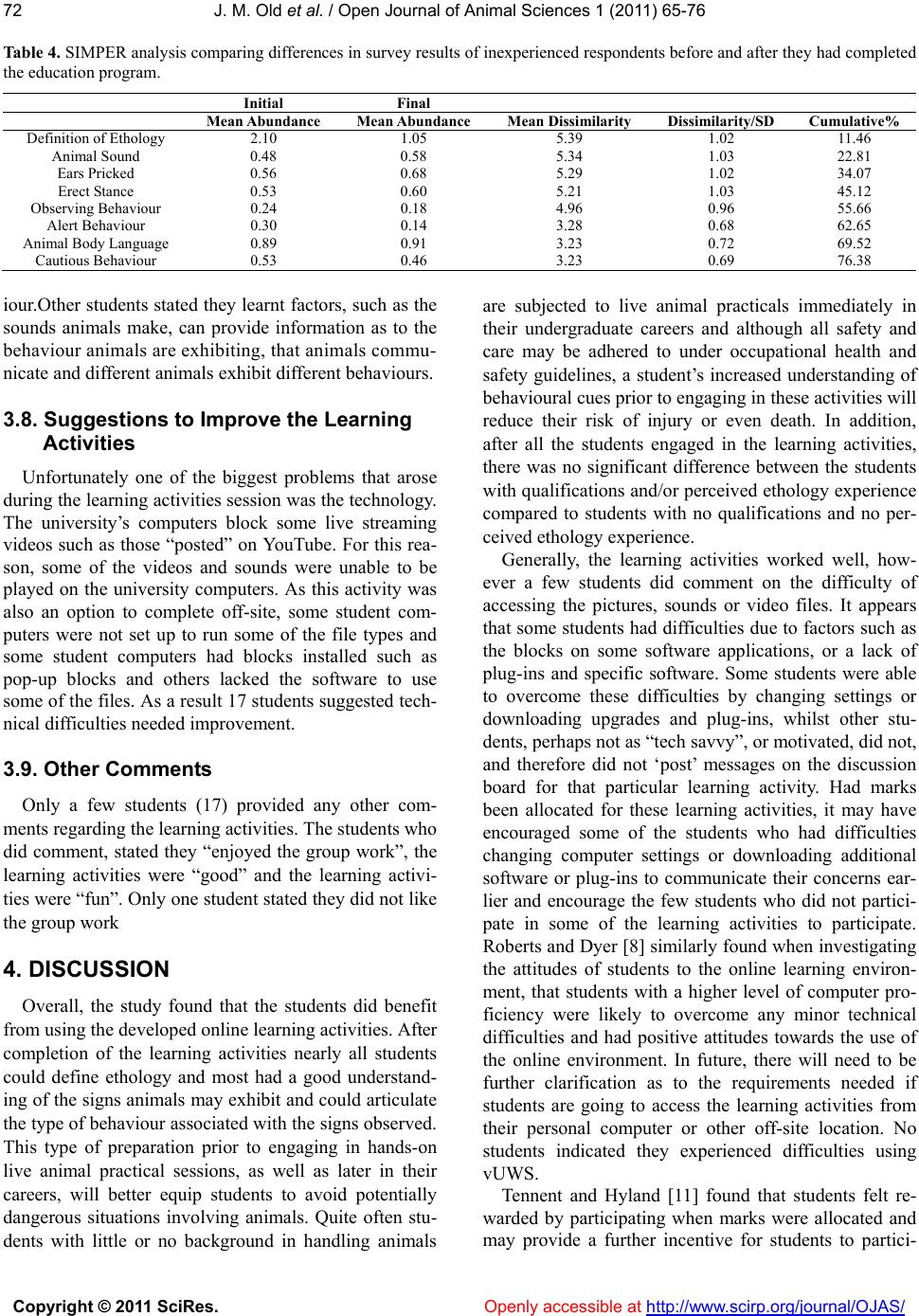

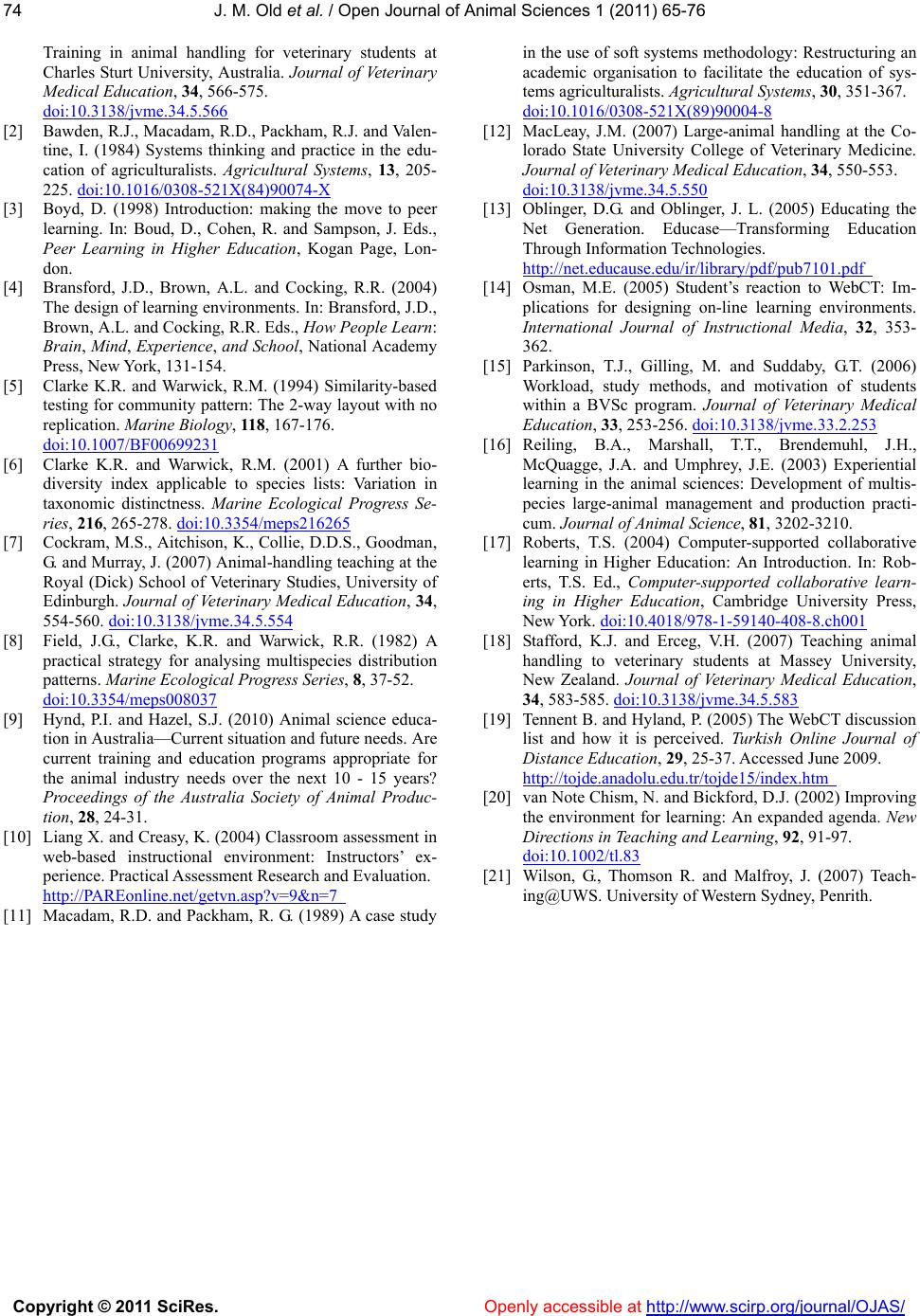

Vol.1, No.2, 65-76 (2011) Open Journal of Animal Sciences doi:10.4236/ojas.2011.12009 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ Development of online learning activities to enhance student knowledge of animal behaviour prior to engaging in live animal handling practical sessions Julie M. Old*, Ricky-John Spencer Native and Pest Animal Unit, School of Natural Sciences, Hawkesbury Campus, University of Western Sydney, Sydney, Australia; *Corresponding author: j.old@uws.edu.au Received 16 May 2011, revised 27 May 2011, accepted 22 June 2011. ABSTRACT Learning activities were developed to increase the awareness of animal behaviour among first year students enrolled in animal-associated degrees prior to students engaging in hands-on live animal practical sessions. Learning activi- ties were developed in an easy to use collegial online environment and to encourage student engagement in learning activities. One hundred and one students were given a preliminary and post learning activity su rvey to assess their ini- tial knowledge and experience of animal be- haviour, as well as to determine if the learning activities increased the students’ knowledge of animal behaviour after engaging in the learning activities. Of the students surveyed, most cur- rently owned pets or have had pets (91.1%), some had animal-related qualifications (22.8%) and currently worked in an animal-related posi- tion (24.8%). There was a significant difference (70.3% increase) in student responses after engaging in the learning activities with the ma- jor change occurring in the students’ under- standing of the term ‘ethology’, regardless of the level of qualifications or animal-related ca- reer experience. In addition, after engaging in the learning activities, most students believed that they could better articulate and interpret animal behaviors based on their observations. Overall, the inclusion of learning activities successfully increased the ability of students to understand behavioral traits of animals, which will increase safety in live animal practical ses- sions. The learning activities also encouraged a collegial learning environment that enhanced new knowledge construction amongst the stu- dents. Keywords: Agriculture; Animal Science; Ethology; Learning; Safety 1. INTRODUCTION The use of animals in laboratory and field environ- ments for undergraduate teaching is vital in animal sci- ence, agriculture, zoology and veterinary science, how- ever there has been increased scrutiny, and justification associated with their use in these contexts. Amongst the many issues covered by the term ‘bioethics’, the use of animals for teaching and research remains a hot topic, with animal rights groups, the general public and ulti- mately legislation requiring increased standards and greater accountability by tertiary institutions. At the coalface are the undergraduate students that are actively using and learning from their experiences with animals, but it is this level which has been largely neglected in terms of improving standards of animal welfare. First year undergraduate students are generally ex- posed to classes involving live animals with no formal preparation, hence programs that prepare students for practicals involving live animals, will not only increase animal welfare standards, but also provide grounding for improved knowledge assimilation for the student. The Hawkesbury campus at the University of Western Syd- ney (UWS) has an extensive history in agricultural teaching [1,2]. Formerly known as the Hawkesbury Ag- ricultural College, the agricultu ral educational institution was established in 1891, and was the first of its kind in New South Wales, Australia. Over the past few years, UWS has offered courses in animal science as well as retaining agricultural degrees. The animal science de- grees are very popular and currently contain one of the larger cohorts of students within the School of Natural Science. The animal science degrees at UWS allow stu- dents to engage their passion in animals, whether it is domestic animals, companion animals or wildlife and  J. M. Old et al. / Open Journal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 65-76 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 66 provide a range of potential career opportunities. The animal facilities (traditional outdoor domestic animal facilities including cattle, sheep , horses and deer, as well as a rat and mouse, native mammal and reptile facilities) on campus allow a range of handling expertise to be gained throughout the courses as well as utilising the wildlife that naturally occur on the campus. In addition many students enrolled in environment and traditional science-based courses such as biology, choose electives from the animal science core units to gain insights into animal husbandry and obtain animal handling skills. Over the last few years the university has seen a change in the student demographic [3]. Previously, many students enrolling in traditional agricultural degrees came from farming backgrounds, whereas more recently the bulk of students enrolling are sourced from the sur- rounding western Sydney area. The reduced number of students from farms enrolling in agricultural degrees has also been evidenced in the United States [4]. Students without farming backg rounds are therefo re entering th eir degrees with less and less exposure to a wide range of animal species and many appear to lack a general under- standing of animal behaviour. The learning objectives for one of the first units within the Animal Science degrees, are aimed at ensur- ing students learn how to handle, restrain and work with animals based on the NSW Animal Research Act, UWS Animal Care and Ethics Committee approved protocols and the Australian Code of Practice for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes. However, prior to students engaging in hands-on animal handling practical sessions there is a need to ensure students have acquired some basic observational skills to increase their confi- dence, around large domesticated animals, as well as wildlife. Not only should this increase in base level knowledge improve the educational experience, but standards of animal welfare should also improve because students may be better equipped to identify behaviours indicative of distress and/or discomfort. In the case of large domestic animals such as horses and cattle, a lack of understanding of interpreting animal behaviour, can also lead to either animal, student, or potentially staff injuries. Likewise, with smaller animals such as rats, mice, small native mammals and reptiles, bites can occur. Good animal handling sk ills and an awareness of animal behaviour is therefore an essential attribute and require- ment of students during enrolment, and graduating from animal science degrees, similar to that stated in [5] for veterinary students. The aim of this study was to develop learning activi- ties that increase student awareness of animal behaviour prior to their engagement in practical sessions. The pa- per discusses the outcomes of students engaging in the learning activities prior to hands-on practical sessions with animals and includes the results of a survey to as- sess what the students learnt by engaging in the learning activities. The learning activities were developed using the online learning environment (Web Course Tools), at the University of Western Sydney called vUWS. 2. MATERIALS AND METHODS 2.1. Development of Learning Activities A collegial peer learning environment was developed for students to “post” their opinions using the online discussion board within vUWS. It was thought this me- dium would be beneficial to all students as it involves sharing of experience, knowledge and ideas among the group members [6] and is learner-centred rather than a teacher-centred traditional didactic lecture method. Small groups of students (up to 10) were randomly cho- sen to work together in the online learning environment with the aim of enhancing engagement in the learning activities, social interaction, and physical comfort [7] as well as critical thinking. The collaborative learning en- vironment was aimed at promoting critical thinking. Roberts [8] has previously suggested a collaborative learning environment is successful because it aids stu- dents to clarify their ideas during discussions. In addi- tion, as students were required to write their responses to one another while unable to see other students’ physical responses (such as facial expressions) straight away, it was hoped it would encourage students to reflect on the “postings”, and their own answers, prior to submitting a new “post” [9]. The incorporation of the discussion board into the learning activities was also aimed at in- creasing inclusiveness, as some students are more likely to respond (“post” a message) in a non-threatening en- vironment. The majority of students enrolled in the animal sci- ence degrees, as apposed to the wider UWS student community, enrol after completing secondary school (18 - 20 years), or within one year of completion of school [3]. Animal science students are therefore presumed to be generally classified as “tech savvy net geners” [10] that are adept at communication via email, b logs, twitter and facebook. The online learning discussion board available through vUWS is therefore presumably easy for students and staff to use. A discussion board on vUWS with small groups (maximum of eight students) was therefore established to allow discussions regarding the pictures, sounds or videos provided. Each student enrolled in the first year Animal Science unit at UWS was randomly provided with a picture, sound and video file of an animal or group of animals exhibiting some  J. M. Old et al. / Open Journal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 65-76 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 6767 form of behaviour and asked to “post” a message on the discussion board stating what they believed the behav- iour to be and to provide evidence to support their deci- sion. Each student was then asked to respond to at least two messages “posted” by another member of their group. Each group of ten students was therefore pro- vided with a maximum of 30 files (of three media types) to discuss and could only see the messages “posted” by members of their group. There were 11 groups in total. An additional benefit of having an online resource al- lowed students to engage in the learning activities at any time. Many students at UWS have part-time jobs and decreasing time and money to spend on their studies. In addition, there is no time lost travellin g to the campus as students can engage in the learning activities in the comfort of their own homes or even the local library or internet café. Tennent and Hyland [11] have previously found that students enrolled as distance or rural students valued online discussion boards and many UWS stu- dents presumably value the flexibility as well. As students were randomly a l lo c at ed gr ou p s, a n d were mostly newly enrolled at university, it was highly likely that the students working together in groups online had not met. The learning activities conducted within the first week of semester therefore also acted as an “ice- breaker” activity and is supported by the findings of Roberts [8] whereby group work encourages student self-esteem, allows students to learn more about their peers and essentially develop a social support network. The collaborative learning environment developed therefore allowed students to meet and socialise and de- velop a social support network with one another. In the longer term, the learning activities may even aid student retention. Apart from the flexibility and collegial benefits pro- vided by the development of the online teaching re- source, the online resource can also provide examples to students of animal behaviours that we can not provide on campus. These behaviours can include specific behav- iours of exotic species we do not have on campus, and other behaviours we can not include due to animal wel- fare implications such as pain, illness and some interac- tive behaviours between different species such as preda- tor/prey behaviour. 2.2. Survey of Student Learning Preliminary and post learning activity surveys were conducted using a matched but anonymous design. See Appendices 1 and 2 for modified versions of the su rvey s. The original surveys had larger spaces provided for some of the questions. The preliminary survey was used to gauge the stu- dent’s level of interpreting animal behaviour, such as their perceived level of knowledge of ethology, their qualifications, and whether or not they had animals of their own in the past or currently, and what type of ani- mal (companion, farm, bird, aquatic and reptile) they have had or currently have prior to engaging in the learning activities. In addition, students were asked th ese specific quest i ons : 1) What observational signs can we use to determine the behaviour of an animal? 2) What signs do you observe in this picture? 3) What behaviour is being exhibited in this picture? Questions 2) and 3) (above) refer to a picture of two kangaroos (see Figure 1) and asked students to describe the behaviour being exhibited and to provide reasoning in their answer. The kangaroo was chosen as it is an iconic and widely distributed Australian animal. After the students engaged in the learning activities, the same picture was shown to assess the level of change in the students’ level of observational skills in regard to exhib- ited animal behaviour. The final survey also had some questions asking stu- dents to state what they believed they had learnt about ethology and allowed them to provide feedback on im- proving the learning activities for future students. Any unmatched surveys were removed from the analysis. Student survey responses were categorised and en- tered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet to allow graphical comparisons to be made. In addition, the Primer v5 [12] statistical package was used for compar- ing student responses, both before and after completing the learning activities. Specifically, SIMPER, ANOSIM 2.3. Data Analysis Figure 1. Photograph of mother eastern grey kangaroo (Macropus giganteus) with young at foot. The photograph was used in both the surveys to gauge the level of observational skills of students prior to and after engaging in the learning activities.  J. M. Old et al. / Open Journal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 65-76 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 68 and non-metric multidimensional scaling (MDS) analy- ses (Primer v5 [13]) were used. Participants were also grouped based on their perceived experience with ani- mals or animal husbandry/handling qualifications (ex- perienced or inexperienced). Bray–Curtis dissimilarities were used to construct an MDS-diagram. The survey responses of all participants were then compared, both before and after completing the learning activities using these techniques. Participants were also grouped based on their perceived experience with animals or animal husbandry/handling qualifications (experienced or inex- perienced). Similar analyses were conducted to deter- mine how both groups differ in their responses both be- fore and after engaging in the learning activities. Prior to the calculation of the Bray-Curtis indices, data was standardised and square-root transformed [12,13]. ANOSIM is similar to an ANOVA but for multivariate statistics. ANOSIM produces an R statistic which corre- lates to how similar the samples are. This analysis pro- duces global (over all samples) and pairwise (between each combination of two samples) R statistics and p values. An R statistic of one indicates that samples are completely different while an R statistic of zero indicates samples are identical [13]. R statistics are only inter- preted here where p values are < 0.05. SIMPER analysis produces an average dissimilarity between samples and gives each species’ percent contribution to this dissimi- larity. 3. RESULTS The study led to both a perceived and actual increase in student awareness of the signs exhibited by animals and their behaviour after completing the learning activi- ties. A total of 101 preliminary and 101 post learning activity surveys were completed. Five surveys that did not have the corresponding preliminary or post learning activity survey were removed from the analysis. Overall, the responses to the survey questions varied significantly prior to and after students engaged in the learning activi- ties (Global R = 0.049 p = 0.01; Figure 2). 3.1. Defining Ethology The major change in the survey responses related to- the students’ understanding of the definition of ethology (Tab le 1). Initially 30 students could not define “ethol- ogy”, and an additional 45 gave an incorrect defini- tion,whereas 26 students could correctlydefine “ethol- ogy” prior to starting the learning activities. Figure 2. MDS plot comparing survey results of all respondents before and after they had completed the education program. This plot separates respondents based on experience or qualifications. Table 1. SIMPER analysis comparing differences in survey results of all respondents before and after they had completed the educa- tion program. Initial Final Mean Abundance Mean AbundanceMean DissimilarityDissimilarity/SD Cumulative % Definition of Ethology 2.10 1.07 6.85 1.3 12.91 Ears Pricked 0.55 0.69 5.42 1.1 23.13 Animal Sound 0.48 0.57 5.29 1.11 33.09 Erect Stance 0.49 0.63 5.19 1.12 42.88 Animal Body Language 0.88 0.91 5.09 1 52.47 Alert Behaviour 0.30 0.14 4.86 0.9 61.63 Observing 0.23 0.18 4.18 0.91 69.51 Final No Experi- ence Final Ex- p erience Preliminary No Experience Preliminary Experience  J. M. Old et al. / Open Journal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 65-76 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 6969 Other definitions included the study of animal ethics (12.9%), animal welfare (4.0%), wild animals (5.9%) and the interactions between animals and the environ- ment (2.0%), and interactions between animals (23.8%). After the learning activities were completed, 97 students could correctly define “ethology”. Overall there was a 70.3% increase in the student’s ability to define ethol- ogy. 3.2. Student Experience and Perceived Level of Experience in Ethology Owning a pet, working in an animal-based position or having qualifications with some ethology included would presumably increase a student’s level of experi- ence in interpreting animal signs and hence their behav- iours due to their interactions with animals. The survey suggested most students had or have had pets of some kind. These students would presumably have obtained some knowledge of ethology by owning and caring for a pet. Surprisingly only a small number of students worked in an animal-based position at the time the sur- vey was completed and greater than 20% of students had qualifications that incorporated some form of ethology, mostly from TAFE (Technical And Further Education), NSW. Overall, there were only a small number of stu- dents (24) that stated that they did not have any ethology experience (or did not know, or did not answer the ques- tion), compared to 44 students that perceived that they had a lifetime of experience in ethology and 33 students had between less than one year and up to four years of experience. The student’s initial level of perceived ex- perience in ethology may have been low due to their lack of knowledge of the term “ethology”. The type of pet/s owned was of interest as a greater number and variety of pets owned would presumably increase the student’s knowledge base of ethology through their increased interaction with a larger number of species. Of the 101 preliminary surveys completed, companion animals (stated as dogs, cats, guinea pigs, rabbits, horses and mice) were the most common pet with 79.2% of students stating they currently have a companion animal as a pet and 80.2% stating that they have had a companion animal as a pet in the past. The next most common currently owned pets were aquatic animals (40.6%), defined as fish and yabbies, and were slightly more common than birds (38.6%). Previously, more birds (60.4%) than aquatic pets (47.5%) had been kept as pets than are currently kept by students. The fourth most commonly owned pets were farm animals, (defined as dogs, horses, goats, cattle, deer, sheep and pigs). Reptiles (snakes, lizards and turtles) were the least common (17.1%) pets currently owned, as well as owned in the past (18.8%). A statistical comparison of pet owners and non-pet owners was not conducted as only nine students were shown to never have owned pets. In addition, some problems arose with the classification of animal species. Some students classified ducks and chickens as com- panion animals, others as farm animals, and others placed them in the ‘birds’ category. Likewise some stu- dents classified horses and dogs as farm animals and others as companion animals. Other pets owned included alpacas, geese, budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulates), rainbow lorikeets (Trichoglossus haematodus), galahs (Cacatua roseicapilla), corellas (Cacatua spp.) and finches. Eleven students that were surveyed do not currently have pets in any of the five groupings, 33 from one group, 21 from two groupings, 17 from three groupings, 17 from four groupings and two from all five groupings. Twelve students had never had any other pets in the past from any of the groupings. Sixteen students of the stu- dents surveyed had pets in the past from only one grouping, 27 from two groupings, 29 from three group- ings, 15 from four groupings and two from five group- ings. In total there were nine students that did not have pets currently or in the past from either of the groupings. In addition to these five groupings, students may also have other pets not defined by these groupings such as stick insects, spiders, burrowing cockroaches, beetles, amphibians such as axolotls or frogs, or mammalian pets such as ferrets, rats and mice. Some students (25) stated they work or had worked in an animal-based position. Three students stated they worked in a pet or produce store, one worked in a wel- fare organization, seven worked with horses, four have worked on farms, two have worked in laboratories, four work as veterinary nurses, one was an animal attendant and three have worked in a combination of ani- mal-related positions. Most of the students surveyed (76) stated they had gained no qualifications in ethology. Twenty-three stu- dents stated they had animal-related qualifications, all of which were from TAFE. Three stated that they had a statement of attainment in Animal Care, 11 had Certifi- cate II qualifications, four had Certificate III, two had Certificate IV, two had a Diploma and one had an Asso- ciate Diploma. 3.3. What Observational Signs Can We Use to Determine the Behaviour of an Animal? Figure 3 provides a graphical representation of the students’ responses to the types of observational signs  J. M. Old et al. / Open Journal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 65-76 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 70 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 animal body language animal sound animal biorhythms ani mal interactions animal interactions with environment Preliminary Post Figure 3. The number of each ‘sign’ stated by students that can be used to recognise behaviour. Both responses provided prior to and after engaging in the learning activities are shown. that can be used to determine the behaviour of an animal. Most students stated that animal body language was an observational sign used to determine animal behaviour before engaging in the learning activities (88.1%) and after engaging in the learning activities (89.1%). The second most commonly stated sign used to determine animal behaviour was the sound animals made. Initially 48.5% stated sound was one of the factors used to de- termine the behaviour of an animal an d after the learning activities there was an increase in this response to 57.4 %. The reasons for the increase in this response (sound) may be a reflection on the type of learning activities provided—videos, photographs and sounds. Prior to the learning activities being conducted, other observational signs suggested included animal biorhythms (11.9%), animal interactions with other animals (9.9%) and ani- mal interactions with the environment (6.9%). These suggestions decreased in number after the learning ac- tivities (5.9%, 3.0% and 7.9% respectively). Prior to the learning activities, three students did not answer the question and following the activities, eight students did not answer the question. In total, only one student did not answer this question either before or after the learn- ing activities (1.0%). Thirty-six students stated only one sign prior to en- gaging in the learning activities, 56 students stated two signs, five stated three signs and one student stated four signs could be used to determine animal behaviour. Thirty-two students stated one sign after engaging in the learning activities, 53 stated two, eight stated three and one student stated that four signs could be used to de- termine animal behaviour. 3.4. What Signs Do You Observe in This Picture? Prior to engagement in the learning activities, students stated four signs they observed in the picture, namely erect ears, erect body stance, eyes fixed and paws up, that could be used to determine behaviour. Figure 4 provides a graphical representation of the student re- sponses to the signs they observe in the picture provided. After engaging in the learning activities, another obser- vational sign was stated, namely, that the young animal was close to the adult (3.0%). Prior to the learning ac- tivities, 32 students did not record any observations, 15 stated one observation, 36 stated two observations, 11 stated three and one student stated four signs. After the learning activities, 15 students noted one observational sign, 32 noted two, 23 noted three and four noted four. Twenty-seve n st udents recorded no observati ons. The most popular observations recorded prior to en- gaging in the learning activities were ears erect (56.4%), followed by erect body stance (50.5%), eyes fixed (12.9%) and paws up (5.0%). Following the learning activities, there was an increase in all observations re- corded, as evidenced by 67 students stating that they observed erect ears, 61 (60.4%) stated they observed an erect body stance, 25 stated they observed ears fixed, eight stated they observed paws up and three stated they observed that the young was close to the mother (a new observation). 3.5. What Behaviour Is Being Exhibited in This Picture? Eight categories were used to classify the behaviour exhibited in the picture provided. The most commonly stated behaviour exhibited in the picture, before the stu- dents engaged in the learn ing activities, were alert/aware behaviour (45.7%), followed by cautious/curious behav- iour (28.7%), and observation (22.8%), and in lower numbers, maternal/protective behaviour (6.9%), listen- ing (5.9%), calmness (0.9%) and predatory behaviour (0.9%). Figure 5 provides a graphical representation of the numbers of behaviours stated by the students to be occurring in the picture. After the students engaged in the learning activities, all categories reduced in number except for the most commonly stated behaviour of alert/awareness behaviour (51.5%) which increased. No calmness or predatory behaviour was stated after the students engaged in the learning activities however mimicry was suggested (2.0%). There was a consistent increase in observing and recording most behavioural traits after engaging in the learning activities, however the recording of Alert and Observing Behaviours de- creased (Table 1).  J. M. Old et al. / Open Journal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 65-76 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 7171 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 ears pricked erec t body stance ey es fix edpaws upy oung c l ose to mother Preliminary Post Figure 4. The signs stated by students that can be used to determine behaviour in the picture provided. Both responses provided prior to and after engaging in the learning activities are shown. 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 alert/aware behaviour cautious/curious behaviour observation maternal/protective behaviour listening calmness predatory behaviour mimicry Preliminary Post Figure 5. The number of each behaviour occurring in the picture provided. Both responses provided prior to and after engaging in the learning activities are shown. 3.6. Statistical Analysis How respondents changed their survey responses also depended on perceived experience or qualification level. Those respondents who considered themselves experi- enced or qualified in animal husbandry responded dif ferently after engaging in the learning activities (Table 2). The major differences in their observations and re- cordings were that they appeared to recognise more sub-tle behavioural traits (eg. Erect Stance and Ears Pricked) and not simply stated their observations as ‘alertness’ (Table 3). More experienced students re- sponded correctly to the definition of ethology before the education program than inexperienced students. Most students responded correctly to the definition of ethol- ogy after completing the learning activities (Table 3). Similarly, inexperienced participants were more likely to categorise certain behaviours specifically rather than simply noting it as ‘alertness’ after completing the learning activities (Table 4). The responses from inexpe- rienced students were varied prior to the learning activi- ties, but they were more similar and consistent after completing the learning activities (Figure 1). Inexperi- enced respondents were more likely to define ethology as either the study of animal ethics or something other than the study of animal behaviour than experienced respondents (Table 4). However, after the education program, very few responded incorrectly. Although both experienced and inexperienced groups modified their answers after completing the learning activities, they modified their answers similarly because the final survey responses of both experienced and in- experienced groups did not differ significantly (Table 2). However perceived experience or qualifications did not appear to help or significantly affect the initial survey responses compared to the inexperienced group (Table 2). 3.7. What Did Students Perceive They Learnt from the Learning Activities? Fourteen students stated they learnt the meaning of the word “ethology”. Interestingly 66 students stated they learnt that you could use a variety of signs to determine the behaviour of an animal or animals and 24 stated they had learnt there were different types of animal behave- Table 2. ANOSIM pairwise comparisons of before and after surveys from respondents with and without experience with animals. R Statistic Significance Level % Final No Experience, Final Experience –0.14 93.3 Final No Experience, Preliminary No Experience0.043 0.1 Final No Experience, Preliminary Experience 0.2 2.9 Final Experience, Prelim No Experience –0.209 99.2 Final Experience, Preliminary Experience 0.224 0.6 Prelim No Experience, Prelim Experience –0.014 54.3 Table 3. SIMPER analysis comparing differences in survey results of experienced respondents before and after they had completed the education prog ra m. Initial Final Behavioural Sign Mean Abundance Mean Abundance Mean Dissimilar ity Dissimilarity/SD Cumulative % Erect S tance 0.10 0.90 6.41 1.18 12.71 Definition of Ethology 1.80 1.00 6.41 1.14 25.41 Ears Pricked 0.50 0.80 6.1 1.21 37.49 Cautious Behaviour 0.50 0.40 5.59 1.05 48.56 Animal Body Language 0.80 0.90 5.57 1.02 59.59 Alert Behaviour 0.30 0.10 5.29 0.97 70.07 Observing Behaviour 0.10 0.20 3.96 0.74 77.91  J. M. Old et al. / Open Journal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 65-76 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 72 Table 4. SIMPER analysis comparing differences in survey results of inexperienced respondents before and after they had completed the education prog ra m. Initial Final Mean Abundance Mean Abundance Mean Dissimilarity Dissimilarity/SD Cumulative% Definition of Ethology 2.10 1.05 5.39 1.02 11.46 Animal Sound 0.48 0.58 5.34 1.03 22.81 Ears Pricked 0.56 0 .68 5.29 1.02 34.07 Erect S tance 0.53 0.60 5.21 1.03 45.12 Observing Behaviour 0.24 0.18 4.96 0.96 55.66 Alert Behaviour 0.30 0.14 3.28 0.68 62.65 Animal Body Language 0.89 0.91 3.23 0.72 69.52 Cautious Behaviour 0.53 0.46 3.23 0.69 76.38 iour.Other students stated they learnt factors, such as the sounds animals make, can provide information as to the behaviour animals are exhibiting, that animals commu- nicate and different animals exhibit different behaviours. 3.8. Suggestions to Improve the Learning Activities Unfortunately one of the biggest problems that arose during the learning activities session was the techno logy. The university’s computers block some live streaming videos such as those “posted” on YouTube. For this rea- son, some of the videos and sounds were unable to be played on the university computers. As this activity was also an option to complete off-site, some student com- puters were not set up to run some of the file types and some student computers had blocks installed such as pop-up blocks and others lacked the software to use some of the files. As a result 17 students suggested tech- nical difficulties needed improvement. 3.9. Other Comments Only a few students (17) provided any other com- ments regarding the learning activities. The students who did comment, stated they “enjoyed the group work”, the learning activities were “good” and the learning activi- ties were “fun”. Only one student stated they d id not lik e the group work 4. DISCUSSION Overall, the study found that the students did benefit from using the developed online learning activities. After completion of the learning activities nearly all students could define ethology and most had a good understand- ing of the signs animals may exhibit and could articulate the type of behaviour associated with the signs observed. This type of preparation prior to engaging in hands-on live animal practical sessions, as well as later in their careers, will better equip students to avoid potentially dangerous situations involving animals. Quite often stu- dents with little or no background in handling animals are subjected to live animal practicals immediately in their undergraduate careers and although all safety and care may be adhered to under occupational health and safety guidelines, a student’s increased understanding of behavioural cues prior to engag ing in these activities will reduce their risk of injury or even death. In addition, after all the students engaged in the learning activities, there was no significant difference between the students with qualif ications and /or perceived ethology experience compared to students with no qualifications and no per- ceived ethology experience. Generally, the learning activities worked well, how- ever a few students did comment on the difficulty of accessing the pictures, sounds or video files. It appears that some students had difficulties due to factors such as the blocks on some software applications, or a lack of plug-ins and specific software. Some students were able to overcome these difficulties by changing settings or downloading upgrades and plug-ins, whilst other stu- dents, perhaps not as “tech savvy”, or motivated, did not, and therefore did not ‘post’ messages on the discussion board for that particular learning activity. Had marks been allocated for these learning activities, it may have encouraged some of the students who had difficulties changing computer settings or downloading additional software or plug-ins to communicate their concerns ear- lier and encourage the few students who did not partici- pate in some of the learning activities to participate. Roberts and Dyer [8] similarl y found when investigatin g the attitudes of students to the online learning environ- ment, that students with a higher level of computer pro- ficiency were likely to overcome any minor technical difficulties and had positive attitudes towards the use of the online environment. In future, there will need to be further clarification as to the requirements needed if students are going to access the learning activities from their personal computer or other off-site location. No students indicated they experienced difficulties using vUWS. Tennent and Hyland [11] found that students felt re- warded by participating when marks were allocated and may provide a further incentive for students to partici-  J. M. Old et al. / Open Journal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 65-76 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 7373 pate or respond with deeper learning or more critical thinking style responses. No marks were allocated for engaging in the learning activities described in th is study, as it was believed that the incentive to participate, en- gage in hands-on practical sessions in live animal han- dling, would be enough incentive to participate. In this study, the reward of marks was therefore replaced by a different type of reward. It therefore appears that the reward used in this study aided student engagement in the learning activities, regardless of a lack of marks be- ing allocated. A similar motivation has been used previ- ously with veterinary students as they likewise want to engage in practical hands-on experiences with animals [14]. It is well recognised that students are motivated by assessment. This activity appears to be no different, as although all the students participated in the learning ac- tivities some students did not engage strongly and their ‘postings’ were limited. If a small assessment weighting had been applied to the learning activities, it would therefore be anticipated that a much larger proportion of students would have engag ed in the learning activities at a deeper level. However, the lack of assessment in this study ensured that the students had control of their own learning outcome, rather then the students focusing on meeting a criterion that would have been associated with an assessment task. If an assessment mark/grade was included as part of the learning activities it may have resulted in students taking less risk in their discussion ‘postings’, reduced the creativity in their responses, and decreased their levels of ne w kn o wl ed ge con st ructi o n. Further studies could investigate more thoroughly if pet ownership is advantageous to first year students when articulating the signs that animals’ exhibit that allow us to define their behaviours. In this study, the categories students chose for their pets varied and a more reliable set of categories would be required in any future study. The differences between the abilities of male and fe- male student to define animal behaviours was not inves- tigated in this study as most of the students enrolled in the agriculture and animal science degrees were female students enrolling straight after finishing high school. A large number of female students have also been observed in students enrolled in animal science degrees at the University of Adelaid e, SA, Australia [9,15] found there was no variation in male or female student perceptions of the use of technology in web-based learning, but some difference in students of varying ages, and so it is unlikely that the online environment had an effect on either males or females. Other factors such as part-time versus full-time enrolment and mature-age versus stu- dents enrolling straight from school were likewise not investigated to ensure anonymity, but could be incorpo- rated into future studies. The learning activities developed had the desired out- come of increasing student knowledge of animal behav- iour and were successful in terms of the development of a social support network where students engaged in a collaborative learning environment and constructed new knowledge through group work activities. Most students can now recognise the signs exhibited by animals and can articulate what those signs translate into in terms of a defined behaviour. The learning activities were there- fore successful in increasing student awareness of ani- mal behaviour and will therefore increase the safety of animals, staff and students in future hands-on practical sessions involving live animals. The learning activities also have the potential to be used by community groups as part of their training sessions prior to trainees engag- ing in hands-on live animal handling such as animal welfare and wildlife rescue organizations. Although teaching aspects of animal husbandry and handling to veterinary students in institutions worldwide has been discussed in several recently published papers (for example, [16-19]), little has been written about the expanding requirements of animal handling skills for animal science and zoology students. Given that animal science students can follow a broad range of career op- portunities, students require a broad knowledge and animal handling skills for a range of companion, live- stock, and native and exotic wildlife species. The inclu- sion of the online resource into the first year animal sci- ence unit will enhance student-learning ou tcomes related to animal handling in the future. At a time when both agricultural, animal science and veterinary sectors have a growing need for personnel trained in the understanding and objective analysis of a growing range of ethical issues, the graduates emerging from tertiary education are largely inexperienced in ap- propriate animal handling techniques. Preparing students for a vocation in these fields not only requires practical experience, but also requires training in the theoretical and historical ba si s behind behaviour. 5. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Funding for this project was provided by a Learning and Teaching Action Plan grant from the University of Western Sydney awarded to JO. This study was conducted with the approval of the University of Western Sydney’s Animal Care and Ethics Committee and Human Ethics Committee. Ms Ruth Donovan provided data entry support. Dr Penny Trevor-Jones assisted in discussions regarding the conduct of the project and Mr John Old provided feedback on an earlier version of the manuscript. REFERENCES [1] Austin, H.E., Hyams, J.H. and Abbott, K.A. (2007)  J. M. Old et al. / Open Journal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 65-76 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 74 Training in animal handling for veterinary students at Charles Sturt University, Australia . Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 34, 566-575. doi:10.3138/jvme.34.5.566 [2] Bawden, R.J., Macadam, R.D., Packham, R.J. and Valen- tine, I. (1984) Systems thinking and practice in the edu- cation of agriculturalists. Agricultural Systems, 13, 205- 225. doi:10.1016/0308-521X(84)90074-X [3] Boyd, D. (1998) Introduction: making the move to peer learning. In: Boud, D., Cohen, R. and Sampson, J. Eds., Peer Learning in Higher Education, Kogan Page, Lon- don. [4] Bransford, J.D., Brown, A.L. and Cocking, R.R. (2004) The design of learning environments. In: Bransford, J.D., Brown, A.L. and Cocking, R.R. Eds., How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experien ce, and School, National Academy Press, New York, 131-154. [5] Clarke K.R. and Warwick, R.M. (1994) Similarity-based testing for community pattern: The 2-way layout with no replication. Marine Biology, 118, 167-176. doi:10.1007/BF00699231 [6] Clarke K.R. and Warwick, R.M. (2001) A further bio- diversity index applicable to species lists: Variation in taxonomic distinctness. Marine Ecological Progress Se- ries, 216, 265-278. doi:10.3354/meps216265 [7] Cockram, M.S., Aitchison, K., Collie, D.D.S., Goodman, G. and Murray, J. (2007) Animal-handling teaching at the Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies, University of Edinburgh. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 34, 554-560. doi:10.3138/jvme.34.5.554 [8] Field, J.G., Clarke, K.R. and Warwick, R.R. (1982) A practical strategy for analysing multispecies distribution patterns. Marine Ecological Progress Series, 8, 37-52. doi:10.3354/meps008037 [9] Hynd, P.I. and Hazel, S.J. (2010) Animal science educa- tion in Australia—Current situation and future needs. Are current training and education programs appropriate for the animal industry needs over the next 10 - 15 years? Proceedings of the Australia Society of Animal Produc- tion, 28, 24-31. [10] Liang X. and Creasy, K. (2004) Classroom assessment in web-based instructional environment: Instructors’ ex- perience. Practical Assessment Research and Evaluation. http://PAREonline.net/getvn.asp?v=9&n=7 [11] Macadam, R.D. and Packham, R. G. (1989) A case study in the use of soft systems methodology: Restructuring an academic organisation to facilitate the education of sys- tems agriculturalists. Agricultural Systems, 30, 351-367. doi:10.1016/0308-521X(89)90004-8 [12] MacLeay, J.M. (2007) Large-animal handling at the Co- lorado State University College of Veterinary Medicine. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 34, 550-553. doi:10.3138/jvme.34.5.550 [13] Oblinger, D.G. and Oblinger, J. L. (2005) Educating the Net Generation. Educase—Transforming Education Through Information Technologies. http://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/pub7101.pdf [14] Osman, M.E. (2005) Student’s reaction to WebCT: Im- plications for designing on-line learning environments. International Journal of Instructional Media, 32, 353- 362. [15] Parkinson, T.J., Gilling, M. and Suddaby, G.T. (2006) Workload, study methods, and motivation of students within a BVSc program. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 33, 253-256. doi:10.3138/jvme.33.2.253 [16] Reiling, B.A., Marshall, T.T., Brendemuhl, J.H., McQuagge, J.A. and Umphrey, J.E. (2003) Experiential learning in the animal sciences: Development of multis- pecies large-animal management and production practi- cum. Journal of Animal Science, 81, 3202-3210. [17] Roberts, T.S. (2004) Computer-supported collaborative learning in Higher Education: An Introduction. In: Rob- erts, T.S. Ed., Computer-supported collaborative learn- ing in Higher Education, Cambridge University Press, New York. doi:10.4018/978-1-59140-408-8.ch001 [18] Stafford, K.J. and Erceg, V.H. (2007) Teaching animal handling to veterinary students at Massey University, New Zealand. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 34, 583-585. doi:10.3138/jvme.34.5.583 [19] Tennent B. and Hyland, P. (2005) The WebCT discussion list and how it is perceived. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education , 29, 25-37. Accessed June 2009. http://tojde.anadolu.edu.tr/tojde15/index.htm [20] van Note Chism, N. and Bickford, D.J. (2002) Improving the environment for learning: An expanded agenda. New Directions in Teaching and Learning, 92, 91-97. doi:10.1002/tl.83 [21] Wilson, G., Thomson R. and Malfroy, J. (2007) Teach- ing@UWS. University of Western Sy dney, Penrith.  J. M. Old et al. / Open Journal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 65-76 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 7575 Appendix 1 Preliminary Student Survey 1. How would y ou define ethology? 2. Circle the type of experience you have had in ethology? You may circle more than one answer. a. None b. Pets c. Work d. Qualifications e. Not sure f. Other please specify: (such as life experiences, holidays, work experience) If you answered (b) above, what pets do you currently have? Reptiles Companion Aquatic Birds Farm If you answered (b) above, what pets have you had in the past? If you answered (c) above, what was the position you were employed in (eg. Veterinary nurse) and how many years were your in that position? If you answered (d) above, what qualifications do you have (eg. TAFE Cert IV) and what year did you gain this qualifi- cation? If you answered (f) above, what other experience do you have? 3. Please circle your perceived level of experience in ethology in years. None Less than 1yr 1-2 3-4 Lifetime 4. What obse rv at i onal sig ns c a n we use t o de t ermine the behaviour of an animal? 5. What signs do you observe in this picture? 6. What behaviour is being exhibited in this picture? Appendix 2 Final Student Survey 1. How would y ou define ethology? 2. What obse rv at i onal sig ns c a n we use t o de t ermine the behaviour of an animal? 3. What signs do you observe in this picture? 4. What behaviour is being exhibited in this picture?  J. M. Old et al. / Open Journal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 65-76 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 76 5. What have you learnt from the Learning Activities? 6. Can you make any suggestions to improve the Learning Activ ities? 7. Any other comments you wish to add? |