Vol.1, No.2, 41-53 (2011) doi:10.4236/ojas.2011.12006 C opyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ Open Journal of Animal Sciences Maternal dystocia in cows and buffaloes: a review Govind Narayan Purohit*, Yogesh Barolia, Chandra Shekhar, Pramod Kumar Department of Veterinary Obstetrics and Gynecology, College of Veterinary and Animal Science, Rajasthan University of Veterinary and Animal Science, Bikaner Rajasthan, India; *Corresponding Author: gnpvog@yahoo.co.in Received 20 April 2011; revised 3 May 2011; accepted 29 June 2011. ABSTRACT The maternal causes of dystocia in cattle and buffaloes are analyzed. Uterine torsion appears to be the most frequent maternal cause of dys- tocia in buffaloes whereas improper cervical dilation appears to be more frequent maternal cause of dystocia in cattle. Failure of uterine expulsive forces (Uterine Inertia) and neo- plasm’s of vagina, vulva and uterus are com monly seen in cows but less frequent in buffa- loes. The various maternal causes of dy stocia in cattle and buffaloes and their management are described. Keywords: Dystocia; Maternal; Uterine Torsion; Inertia; Neoplasms 1. INTRODUCTION Amongst all domestic animals, cattle and buffalo are considered the species in which the incidence of dystocia appears to be highest. Although cattle and buffaloes ap- pear to be similar in the parturition process but subtle differences are known to be existent in the anatomy and physiology of the birth canal between cows and buffa- loes. The anatomic differences in the pelvis [1] and geni- tal structures have been described. The differences in the pelvis between cow and buffalo include more capacious pelvis, larger area of ilium and the free and easily sepa- rable fifth sacral vertebra in the buffalo [1]. The differ- ences in the genital structures include tightly downward curled uterine horns, less conspicuous shorter and nar- rower cervix, smaller and less tight vagina and elongated and wide apart vulvar lips in the buffalo [2]. Physiologic differences between cattle and buffalo pregnancy and parturition include a longer gestation period in the buffalo (305 to 320 days for the river and 320 to 340 days for the swamp buffalo [3], com- pared to 280 days in cattle [2], lesser time required for completion of first and second stages of labor[1,4,5] (70 and 20 minutes in buffalo compared to 2 to 6 and 0.5 - 1 hours in cows), a preponderance for parturition during night hours [6], and an absence of physiologi- cal cervical hypertrophy with consecutive calvings in the buffalo [2]. All the above differences between cows and buffa- loes point out that the parturition process is much easier in the river buffalo compared to cows and therefore, Jainudeen [3], considers that dystocia is not a serious problem in the water buffalo. The incidence of dystocia is considered to be higher in river than in swamp buffalo (in which it has not been described) and also in primipara than in pleuripara [3] however, a few studies consider higher incidence of dystocia in pleuriparous buffaloes [7]. In cows the incidence of dystocia is higher compared to that in heifers [8-10]. 1.1. Causes of Dystocia in Cows and Buf- faloes The causes of dystocia are generally classified into the maternal and fetal causes [11-14]. Buffaloes are known to have greater incidence of maternal dystocia [15,16], however, in many other studies; a higher in- cidence of fetal dystocia was recorded [7,17-19]. In the authors’ experience buffalo generally have fewer problems in dilation of the birth canal com- pared to cattle and there is a greater incidence of uterine torsion in buffaloes. The incidence of fetal monstrosities is higher in the buffalo. 1.2. Maternal Causes of Dystocia The maternal causes of dystocia are considered to be arising either because of the constriction/obstruction of the birth canal or due to a deficiency of the maternal expulsive force [13,14,20-22]. Each of the cause is de- scribed in detail. 2. CONSTRICTION/OBSTRUCTION OF THE BIRTH CANAL The constriction/obstruction of the birth canal can result in maternal dystocia and can be due to pelvic  G. N. Purohit et al. / Open Jour nal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 41-53 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 42 abnormalities, vulvar or vaginal stenosis, neoplasms of the vagina and vulva, vaginal cystocoele, incom- plete cervical dilation, uterine torsion and ventral dis- placement of the uterus. An uncommon cause of con- striction of birth canal is carcinoma of urinary bladder [23,24] with metastasis in cervix. 2.1. Pelvic Abnormalities Pelvic abnormalities of the mother that can result in dystocia include small size of the pelvis [13], pelvic deformities or exostoses [11], osteomalacia and hy- poplasia of vagina and vulva [1]. Breeding of heifers at too young an age, breeding of poorly grown heifers, or breeding of heifers and cows that had pelvic fractures can result in a smaller pelvis of the mother culminating in dystocia at parturition. Breeding of small sized breeds of cattle or buffaloes with breeds of larger size can result in fetuses of bigger size being obstructed at the small sized pelvis of the mother. Rarely, the cause of small bony pelvis is sacral luxa- tion or displacement [13]. Other causes described in- clude twins and intra pelvic hemorrhage [20]. However, pelvic fractures and exostoses are considered to be un- common as a cause of dystocia in large animals [11]. An inadequate sized pelvis is a frequent cause of dystocia in the bovine primipara [14,21]. Narrow pelvis is known to be a cause of dystocia in the buffalo [25]. The incidence of narrow pelvis has been recorded to be 7.79 percent [7]. 2.1.1. Incidence The incidence of pelvic deformities as a cause of dys- tocia in buffaloes is described to be 1.2 percent [26]. In cows and buffaloes, the incidence of narrow pelvis is known to be 9.2 percent [18]. 2.1.2. Clinical Signs Usually, there is a lack of progress in the second stage of labor. If the fetus is able to enter the pelvis partially, severe non-progressive straining occurs. If the fetus is too large, then there is no progress in delivery subse- quent to first stage of labor. Vaginal examination must be done to compare the fetal and pelvic size. Any previous fractures can be ascertained by the presence of calluses. 2.1.3. Management of Dystocia If by palpation, it is felt that the fetus can pass through the birth canal with assistance, traction must be applied on the fetus after plenty of lubrication. However, excessive traction in a narrow birth canal is not advisable. It is better to opt for a caesarean section if the birth canal is too narrow, or it is coupled with fetal postural abnormality. 2.2. Vulvar or Vaginal Stesis/Stricture/Rupture Formation of scar tissue due to injuries sustained at previous calving in aged animals [13], improper relaxa- tion during parturition, congenital stenosis of the vagina [13], vaginal obstruction by fibrous bands [27,28], perivaginal abscess or cysts can occlude the genital pas- sage and hinder with the delivery of the fetus. Dystocia due to an infantile vulva has been recorded in a Jersey heifer [29]. In the authors experience improper relaxa- tion of the vulva/vagina is less common in the buffalo [21]. Fetal parts may get stuck up in a ruptured vagina and result in dystocia [30], or the gravid horn may some- times prolapse through the vaginal rupture [31]. Post partum vaginal ruptures can sometimes result in prolapse of abdominal organs [32]. 2.2.1. Clinical Signs Improper vulvar relaxation may be evident clinically and there may be difficulty sometimes in inserting the lubricated hand into the birth canal. The vulva may have a hard consistency in some cows; however, due to the anatomic structure vulvar relaxation is less a problem in the buffalo. Improper vaginal relaxation is evident on internal examination of the vagina. Perivaginal abscesses or haematoma may be palpable as soft or firm fluctuating masses pressing the vaginal walls inwardly. Vaginal ruptures can be located by careful palpation. 2.2.2. Management of Dystocia The usual management of a constricted vulva sug- gested is gentle manipulation with or without an episi- otomy cut, about one third down the lateral wall of the vulva through the skin mucosa junction [33]. Surgical correction of the vaginal stricture has been suggested [34]. Mucosal folds in the vagina caudal to cervix obstruct- ing the passage of fetus can be broken manually. Creams containing prostaglandins E2 are in common practice in medical obstetrics and can be tried in functional non-dilation however, in large sized perivaginal ab- scesses or hematomas, it is a wise decision to opt for a caesarean section rather then to apply undue traction. The fetus must be delivered by traction in the presence of vaginal ruptures which must then be sutured. Like- wise, the prolapsed part must be replaced and the vagina sutured in mid gestation vaginal ruptures. 2.3. Neoplasms of Vagina, Vulva, Uterus  G. N. Purohit et al. / Open Jour nal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 41-53 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 4343 Tumours of the vulva, commonly seen in cows in- clude papillomata, sarcomata, fibroma and squamous cell carcinoma [35,36]. Cryosurgery of squamous cell carcinoma of vulva has been suggested. Submucus vaginal tumours are uncommon in cattle and buffaloes, however, leiomyomas [37,13], sqamous cell carcinoma [38,13], perivaginal granuloma [39], lipoma [40], fi- broma [38] and fibroleiomyoma of vagina [41], have been reported but seldom seen clinically during dystocia. Tumours of the cervix include fibroma [42-45], ademona [46] fibro leiomyoma [47-49] and squamous cell carci- noma [50] or nebothean cyst [51]. Carcinoma of the cer- vix has been recorded in the buffalo [23,24]. The tumor masses in cervix and vagina seldom obstruct the birth canal and are usually noticed subsequent to parturition when they prolapse out. Tumours of the uterus are re- corded from genitalia usually obtained post slaughter and include adenoma [52], lipoma [52] and fibroma [38] or polyps [53] noticed subsequent to calving. When no- ticed clinically, they either prevent a pregnancy or cul- minate in abortion [54]. The incidence of uterine tu- mours in the buffaloes is known to vary from 0.3 to 0.7 percent [55]. 2.4. Vaginal Cystocoele Vaginal cystocoele has been described to be occurring in the mare and cow [56,57] and also in the buffalo [58] and can result in dystocia. The condition involves the protruding of the urinary bladder either through the aversion of the organ through the urethra [56] or prolapse through a rupture on the vaginal floor [32]. Prolapse through a rupture on the vaginal floor is more likely in the cow and buffalo. Since the prolapsed blad- der may obstruct the birth canal it is suggested to iden- tify the organ and replace it back after repelling the parts of the fetus under epidural anaesthesia and ample lubri- cation. The vaginal rupture must be sutured after re- placement of the urinary bladder. The fetus can then be delivered. 2.5. Incomplete Cervical Dilation The dilation of the cervix at the time of delivery of fetus is essential for the easy passage of the fetus. A wide variety of changes in the hormonal milieu [59,18] enzy- matic loosening of fibrous strands by elevated colla- genase [60] and the physical forces of the uterine con- tractions and fetal mass are considered to be responsible to effect sufficient dilatation of the cervix during parturi- tion in the cow [61] and buffalo [62,63]. An activation of inflammatory network is considered to play an important role in the progress of cervical dilation [64)]. An in- crease in inflammatory cytokines during parturition is known to effect dilation [65] as is the interplay of hor- mones. In buffaloes, however, cervical non-dilation is rare. Only sporadic cases have been reported [66]. Ani- mals with delivery problems associated with the cervix are those that had already delivered many calves [67]. Cervical non-dilation can occur because of the failure of any of the mechanisms responsible for dilation described above or spasm of the cervical muscles [3] or some other poorly understood mechanisms and results in dystocia. 2.5.1. Incidence The incidence of cervical dystocia was seen to be from 11.1 to 16.7 percent [67] in cows. The collective incidence of incomplete cervical dilation in cattle and buffaloes is described to be 5.1 percent [18]. 2.5.2. Clinical Signs When the cervix is fully dilated, it is not palpable as a separate structure and is continuous with the vagina. Incompletely dilated or undilated cervix is palpable through per rectum examination. By examination per vaginum only a finger or two can be inserted in a par- tially dilated cervix. Parts of fetus or the water bags can sometimes be palpated at the cervix. 2.5.3. Management of Dystocia Attempts can be made to dilate the cervix manually if possible using sponge tents and local anesthetics [1], but because the cervix has many annular rings it is often not possible to dilate the bovine cervix manually. If the fetus is present in the birth canal gentle traction over long pe- riods can sometimes dilate the cervix, but excessive trac- tion is not advisable. It sometimes happens that a mald- isposed fetus present in a previously dilated birth canal becomes tightly impacted because of continued uterine contractions without fetal delivery. An obstetrician must differentiate such a case from incomplete cervical dila- tion. If the cervix remains closed, the fetus is live and its fetal membranes are intact, it is suggested to wait for 30 minutes to allow time for natural dilation. A deficiency of estrogen is considered to be one im- portant cause of failure of cervical dilation [68], hence, injection of estrogens like estradiol valerate 20 - 30 mg im can be helpful, however, estrogen should be given with care in a completely closed cervix because of the dangers of uterine rupture that may follow because of violent contractions. Likewise, injections of oxytocin 20 - 40 IU, iv or im can be given to promote uterine con- traction to effect cervical dilation when it is partially dilated. When the legs of a putrefied dead, fetus are pre- sent in the birth canal and the fetus cannot come out be- cause of incompletely dilated cervix, the authors suggest  G. N. Purohit et al. / Open Jour nal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 41-53 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 44 partial cervicotomy instead of a cesarean. One or two cuts applied on the cervix are usually sufficient to de- liver the calf. In the authors experience potent analgesics like valethamate bromide (Inj. Epidosin TTK Pharma, India) at the dose rate of up to 500 mg im or iv is of lim- ited value in dilating a closed bovine cervix at term. β2 adrenergic drugs like isoxsuprine at doses of 200 - 300 mg iv or 0.3 mg iv clenbuterol have been suggested to relax the entire genital tract including the cervix but may not be always helpful because of the complex mechanism that is responsible for cervical dilation which largely remains poorly understood. Moreover, the β2 adrenergic drugs would reduce uterine contractions and hence delay parturition. Caesarean section appears to be the best re- sort when all attempts at cervical dilation have failed. Use of relaxin as a cervical ripening agent and its use for inducing labor in human subjects still remain unclear [69] and hence, its use in animal therapy is out of question because of the high cost. 2.6. Uterine Torsion Torsion of uterus usually occurs in a pregnant uterine horn and is defined as the twisting of the uterus on its longitudinal axis [58]. The pregnant uterus rotates about its long axis, with the point of torsion being the anterior vagina just caudal to the cervix [13] (post cervical tor- sion). Less commonly the point of torsion is cranial to the cervix [13] (pre-cervical torsion). Uterine torsion during pregnancy [70,71], at parturition [72-75], or post-partum [66,67] is one of the complicated cause of maternal dystocia both in cows and buffaloes culminat- ing in death of both the fetus and the dam if not treated early. There exists a difference of opinion as to the fre- quent side of uterine torsion in cows. While Arthur et al. 1996 and few other workers concluded that the side of torsion is generally left side in cows, a few reports [78,79] and the authors are of the view that because of presence of rumen on the left side, the side of torsion should usually be the right side in cows. For buffaloes, right sided torsion is mostly reported [62,80-82]. It is probable that pregnancies occurring in the left horn may be rotating towards the left side especially when rumen is partially filled. The degree of torsion is generally 90˚ to 180˚ although it can occur up to 360˚ or even more. Torsions up to 540˚ [75] or 760˚ [83] have been recorded. Because of the rapidity of fetal death that ensues fol- lowing torsion and the uterine adhesions with visceral organs that develop, uterine torsion must be considered an emergency. Torsion has been reported from a cow with didelphic uterus [84,85] and along with uterine prolapse [86]. Torsion can result into haemoperitoenum if it results from horn butting between animals [87]. A rare case of uterine torsion in a buffalo carrying twin fetus has been reported [88]. 2.6.1. Incidence The incidence of uterine torsion is considered to be higher in buffaloes compared to cows. The reasons for such a discrepancy are poorly explained. Uterine torsion is considered to be the single largest condition contrib- uting to dystocia in buffaloes with incidence as high as 56% to 67% [25,81,89] and up to 70% [16]. Uterine tor- sion has been reported mostly in dairy type buffaloes of India, Pakistan [90] and Egypt [91,92], but reports on its occurrence in the swamp buffalo are not seen. In the authors experience uterine torsion is predominantly seen in dairy cows and dairy buffaloes [81]. In cows the inci- dence is comparatively lower although at various loca- tions it is known to vary between 7% to 30% [92-94]. The incidence is known to be higher in pleuriparous cows [72,75,79] and buffaloes [25,75,94,95] with maximum frequency during second and third calvings [96,62]. Although a seasonal incidence [25,80] has been de- scribed in buffaloes but it appears to be because of higher calvings during that season. The usual age (years) of animals that suffer from uterine torsion is 4 - 12 for buffaloes and 5 - 7 for cows [72]. The incidence is known to be more in cows maintained on mountainous areas [97]. 2.6.2. Etiology The exact etiology of uterine torsion is poorly under stood. It appears that instability of the uterus during a single horn pregnancy and inordinate fetal or dam movements probably are the basic reasons for rotation of the uterus on its own axis. The bovine amnion is fused at many places to the surrounding allantois, which is at- tached to the uterine wall [98]. Rotatory fetal move- ments during the second stage of labour or late gestation would rotate the uterus. The uterus lies on the abdominal floor during mid and late gestation with no stabilizing attachments. A large number of predisposing causes have been described [58,103] for uterine torsion and include anatomical factors, close confinement, hilly tracts, and wallowing habits of the buffaloes and the lowering of front legs by the animal first, when lying down. The higher occurrence of the problem in buffaloes is hy- pothesized to be because of a deep capacious and pen- dulous abdomen of buffalo [97], inherently weaker mus- cles of the broad ligaments [99,100] and the wallowing habits of the buffalo [97]. However, daily forceful wal- lowing of pregnant buffaloes failed to induce uterine torsion in one study [101]. Some exciting causes for the occurrence of uterine torsion have been described [58] and include external injury, lack of exercise and irregular movement of animals. Uterus didelphus has been de-  G. N. Purohit et al. / Open Jour nal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 41-53 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/Openly accessible at 4545 scribed as one of the cause of uterine torsion in the buf- falo [97]. Slight rotations (below 90˚) are symptom less clinically and may be corrected spontaneously but rota- tions of higher degree usually do not detort spontane- ously. 2.6.3. Nature of Uterine Torsion A pregnant uterine horn may rotate at mid to late ges- tation, at normal parturition time, or sometimes post partum. The horn may rotate to its right (clock-wise) or left side (anti-clockwise) with degree of rotation from 90˚ to 720˚. The point of rotation can be caudal to the cervix (post cervical) [102] or just cranial to the cervix (pre-cervical). The percentage of frequencies of the na- ture of torsion in terms of its relation with gestation, side of torsion, point of rotation and degree of rotation re- ported in some of reports are mentioned in Table 1. It is clear that uterine torsion generally occurs at parturition in cows and buffaloes, on the right side of the abdomen at a point just caudal to cervix and usually rotates to 180˚ or more from its axis. 2.6.4. Clinical Signs The usual clinical signs are the onset of labor without delivery of fetus and/or fetal membranes [13] and later regression of parturition signs [25]. The cow may show signs of mild discomfort. The animal may adopt a rock- ing horse stance [13,103] and show mild colic pain. Par- tial anorexia, dullness and depression may be evident [94]. Restlessness and arching of back and colic may be seen in buffaloes [71]. One or both lips of the vulva are pulled in because of torsion of the birth canal. Vaginal examination reveals twisting of the vaginal mucous membranes and the hand cannot be passed deeper into the anterior vagina which has a conical end in torsion with a degree of 180˚ or more. In lesser degree torsions however, the fetus can be sometimes felt. The direction of the vaginal fold twisting shows the direction of tor- sion. On rectal examination, the twisted horn can be felt and the broad ligament on the side of torsion is rotated downwards sometimes palpable under the uterus and the ligament on the opposite side is tense and stretched and crossing to the opposite side. The positive diagnosis of uterine torsion should thus, be based on the location of broad ligaments palpated per rectum. Animals at many locations may be presented to the obstetrician after varying times since the first onset of labour; hence, the clinical signs of shock, toxaemia may be evident de- pending upon the severity of torsion, previous handling, death of fetus and post-torsion complications. Clinical studies on the hematology and blood biochemistry of torsion affected buffaloes have shown marginal differ- ences [105,106]. 2.6.5. Management of Dystocia Cases of uterine torsion must be considered an emer- gency and therapy must be instituted early. It is impera- tive to precisely evaluate the patient for the general con- dition before any handling efforts. The patient must be evaluated for presence of toxaemia and shock as cases presented to the obstetrician after 36 hours are likely to have one or more of these conditions. The authors sug- gest infusion of plenty of fluid therapy along with corti- costeroids and antibiotics whenever necessary to combat toxaemia and shock before handling of cases presented beyond 36 hours of delay. It is also usual to assess the type of previous handling or therapies provided includ- ing previous rolling given. Cases presented beyond 36 - 72 hours are likely to have plenty of toxaemia set in, fetal death coupled with loss of fluid and uterine inertia. Table 1. Percent frequencies of the nature of torsion in cows and buffaloes. Buffaloes Cows Reference Age (Year) 4 - 12 5 - 7 72 1 - 5 2 - 3 72 Pleuriparous Pluriparous 103 1st-16% - 54 2nd-24% - 62 3rd & above-56%- 62 1st-31.9% - 62 2nd 20.5% - 54 No. of Calving 2nd-6th-79% - 108 Stage of gestation 18.0% - 62 2.0% - 39 2.63% - 103 16.52% 22.8% 72 Pre-term 5 - 60 days 2 - 5 days 72  G. N. Purohit et al. / Open Jour nal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 41-53 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 46 25.5% - 54 78% - 62 81.3% - 81 100% 100% 103 98% - 39 83.4% 77.20% 78 100% - 54 At parturition 100% - 92 Prolonged gestation 9.1% - 49 Post partum - 2 to 4 weeks post partum77 Nature of torsion Side of torsion 94.0% - 54 Right 6.0% - 62 79 116 87.0% - 39 63.8% 100% 72 87.0% - 81 97.79% 82.26% 78 8.5% - 72 12.9% - 39 2.21% 17.14% 78 Left - 75% 6 Place of torsion 8.5% - 72 19.82% - 103 - 27% 39 - 4.17 73 Pre cervical 50% - 108 18 63.8% 100% 72 100% 99% 103 95% - 81 94.8% - 62 95% - 54 50% - 108 Post cervical 92.86% - 49 Degree of torsion 8.06% - 81 90˚ 21.28% - 54 64.0% - 81 64.6% - 62 46.8% - 54 41.2% - 108 180˚ - 98˚ - 180˚ most common104 270˚ 20.9% - 81 6.4% 81 - 82% 73 19.15% - 54 360˚ 38.2% - 108 540˚ 4.6% - 108 720˚ 6.1% - 108 Single case 83  G. N. Purohit et al. / Open Jour nal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 41-53 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/Openly accessible at 4747 The incidence of uterine rupture is fairly high and there- fore an examination should be made for this before treatment. Rarely uterine torsion can result into problems like jejunal incarceration [107].The histamine levels are known to be high in buffaloes suffering from uterine torsion [108], hence, antihistaminics should be given. The management techniques in cows and buffaloes sug- gested for detorting the rotated uterus include rotation of the fetus and uterus per vaginum [13], rolling of the animal, laparotomy with manual intra-abdominal ma nipulation and laparohysterotomy [21]. The choice of the method to be adopted depends on the nature and intensity of the torsion, the viability of the fetus and the time lapse since dystocia onset. Rotation of the fetus per vaginum is possible only in mild degrees of torsion where the obstetricians hand can touch the fetus and sufficient fluids are present in the uterus [13]. The fetus is grasped by a bony prominence such as elbow, sternum or thigh and swung from side to side before being pushed right over in the opposite di- rection of torsion. If both fetal limbs are palpable they can be tied in the cuffs of caemmerer’s torsion fork or a Kuenhs crutch and an assistant can rotate them. If the manipulation is successful, the torsion will disappear and the vaginal folds will regain normal shape and the fetus can be delivered with little difficulty. However, suffi- cient lubrication must be available in the birth canal and uterus before attempts at rotating the fetus are made us- ing instruments. When sufficient time has passed since the onset of such a problem, the uterus will tightly con- tract around the fetus and detortion with this method is not possible. Rolling the cow or buffalo utilizes the principle to roll the animal around its uterus while the uterus remains static. It is one of the oldest and simple methods to re- lieve uterine torsion in cows and buffaloes. The animal must be rolled preferably on grass with its head lower than the rear quarters. Vicious animals must be given a sedative. The animal is laid down in lateral recumbency on the same side to which the torsion is directed. The two hind legs are tied together by a rope. Both the fore legs are also tied together using a separate rope. The animal is rolled suddenly in the same direction as the torsion of the uterus to the other side. The rapidly rotat- ing body of the cow/buffalo overtakes the more slowly rotating gravid uterus. After the animal has been rolled to 180˚ her body must be brought back to the original position slowly so that she can be rolled once again. Af- ter two rolling, the birth canal should be examined to determine whether the torsion is corrected or not. If cor- rected properly, the spiral folds and stenosis of the birth canal would disappear and if the cervix is dilated, the fetus can be palpated with ease. Plenty of blood stained fluid comes out of the birth canal if the cervix is open and this is sufficient evidence of torsion correction. If the torsion is not corrected, the rolling procedure should be repeated 3 or 4 times. If after 4 attempts, the torsion is not corrected, then other procedures for correction of torsion must be considered as uterine rupture can result due to violent rollings [109,110]. Although, torsion may be corrected by rolling in patients of not more than 36 hours duration, the potential dangers of uterine rupture with continuous rolling must always be kept in mind. If the vaginal folds are increasing after a rolling, the rolling must be done on the opposite side. Sometimes, after the correction of torsion, it may take 12 hours or more for the cervix to dilate and hence one should not take rapid action of removing the fetus after torsion correction without proper cervical dilation. Prostaglandin injections are suggested subsequent to torsion correction if the cer- vix is not dilated. Fetuses are delivered 12 - 24 h later in such cases. A modification of the rolling technique called Schaffer’s method, has been described by Arthur, [111] and recommended widely [58,79] for detorsion of uterus in cows and buffaloes. In this method, a slightly flexible wooden plank of 9 to 12 feet long and 8 to 12 inches wide is placed on the recumbent cows flank with the lower end of the plank on the ground. An assistant stands on the plank while the cow/buffalo is slowly turned over by pulling the ropes. A slight modification of this method has been suggested for the buffalo [112]. The advantages of this technique are that the plank fixes the uterus while the cow’s body is turned and that, because the cow/buffalo is turned slowly less assistance is re- quired and it is easier for the veterinary surgeon to check the correct direction of the rolling by vaginal palpation [21]. Usually, the first rolling is successful [14]. Similar methods have been used with varying degrees of success in the buffalo [74,75,95]. It is considered that since buf- faloes have a capacious abdomen more pressure is re- quired on the free end of the plank that is being modu- lated by an assistant resulting in better detorsion com- pared to the Schaffer’s method [113]. The number of turns required in buffaloes are more (2.5) compared to cattle (1.0) [95] and vaginal delivery takes a longer time after detorsion. Buffaloes with fully dilated cervix at detorsion had maximum survival [89,75] and detorsion failure occurs in 20% of the cases [66]. In the authors experience, detorsion failure is common in cases presented beyond 36 hours of delay and in animals  G. N. Purohit et al. / Open Jour nal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 41-53 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 48 where dead emphysematous fetus is present or uterine adhesions or uterine rupture is present. Similar views have been expressed by other workers [114,115]. It is known that detorsion is difficult in the presence of a dead fetus [78]. Myometrial degeneration and endo- metrial damage is more in cases of uterine torsion that are delayed for treatment [116]. Laparotomy with manual intraabdominal detorsion is suggested in cases of torsion during mid or late gestation, or when the cervix is closed [79]. The procedure de- scribed involves laparotomy through the left or right paralumbar fossa under paravertebral or local infiltration anaesthesia in a standing lightly tranquilized animal. The hand is passed between the uterus and abdominal wall or rumen and uterus, the fetal extremity is grasped and by rocking movements the uterus is lifted and detorted. The fetus may be removed if it is dead. Otherwise, it is left for completion of gestation. The abdominal would is closed routinely. Laparohysterotomy is suggested in cases of uterine torsion that fail to be corrected by rolling or in long standing cases where fetus is dead and uterine adhe- sions/rupture are likely. The outcome of a caesarean when the fetus is dead and emphysematous can be grave. It is advisable to take care of the patient for the general condition before deciding to operate. Caesarean is a method of choice in cases presented with a closed cervix, dead fetus with subsided symptoms of parturition [114]. It is better to administer plenty of fluid therapy, antibiot- ics and corticosteroids before starting the operation. Different operative sites for caesarean are suggested including the right [84,114] or left flank, midline (on or parallel to linea alba), horizontal incision above arcus cruralis [25], or appropriate incision in the right [94] or left lower flank [71,74,117] or an oblique ventrolateral approach with the animal in right lateral recumbency [21]. The authors and few other workers [95,118] con- sider the left oblique ventro lateral approach with the animal in right lateral recumbency as a better operative site as it results into minimum post operative complica- tions. The anesthesia usually required is mild sedation with local infiltration. The anesthetic management of cattle has been reviewed recently [119] and detomidine is suggested as the drug of choice when sedation is needed in pregnant cattle. An iv dose of 2.5 - 10µg/Kg produces standing sedation for 30- 45 min [120]. Higher dose (40 µg/Kg, iv) will produce profound sedation and recumbency [16]. General anesthesia using xylazine (0.1 - 0.2 mg/kg im) can be given to cattle followed by keta- mine (10-15 mg/kg im). Such anaesthesia lasts for 45 minutes and can be prolonged by use of additional keta- mine (1 - 2 mg/kg iv). Inhalation anaesthesia with halo- thane and isoflurane with tracheal intubations using conventional human anaesthetic machines are sufficient for animal’s upto 200 kg [119] and are now becoming increasingly common for bovine anaesthesia because cows seldom experience emergence delirium, with inha- lation anesthetics. During the laparohysterotomy, the uterus is brought to the site of incision by holding a fetal extremity and in- cised. The fetus is removed with due care. Because of the fetal death and the consequent uterine adhesions that develop in cases operated beyond 36 hours it is not many times possible to detort the uterus before the removal of the fetus. Rarely if the animal had uterine torsion, rup- ture of uterus can occur subsequent to attempts at cor- rection of torsion by rolling. Such ruptures must be searched during the operation and if possible repaired. If the tear is not within approach, the best option is to inject 20 - 40 IU oxytocin within the uterine wall at 3 - 4 or more locations to contract the uterus. The abdominal wound is closed routinely. A few of other less commonly used methods, have been described for correction of uterine torsion [57] in- cluding suspension of the cow’s body, abdominal bal- lotment, and stimulation of vigorous fetal movements. If the cow’s hind parts are raised with her ventral ab- dominal wall uppermost, gravity will cause the uterus to fall back into its normal position [93]. The cow is raised until its back forms an angle of atleast 45 degree with the floor. However, the method appears to be difficult and not used widely. Abdominal ballottement [121] is performed with the animal standing. Two assistants one on the right side with clenched fist pushes downwards and inwards and the other on the left pushes upwards and inwards low down on the flank. The push is given alternatively each at a rate of about one per second, so as to make the uterus swing and being corrected because of the fetal movements. The method however, appears to be work- ing in fresh cases of uterine torsion of less than 180˚. Likewise, stimulation of fetal movements by rectogenital pressure on fetal parts can sometimes correct the uterine torsion of smaller degree. It is considered that abdominal ballotment is not pos- sible in the buffalo due to a heavy abdominal muscula- ture [97]. The major complications that can occur following uterine torsion are fetal and maternal death [66], uterine rupture, vaginal rupture [32,33] and poor fertility fol- lowing correction of a long standing case of torsion. Sometimes fatal peritonitis or expulsion of fetus in the abdominal cavity from a uterine rupture is possible. 2.7. Downward (Ventral) Displacement of the Uterus  G. N. Purohit et al. / Open Jour nal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 41-53 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 4949 Ventral displacement of the uterus is an uncommon cause of dystocia in cows [13] and buffaloes [21]. It is seen in animals with a ventral hernia or rupture of the prepublic tendon where the pregnant uterus passes downward into the point of the hernia. 2.7.1. Clinical Sings If the herniation is large enough, a herniated uterus can be recognized externally with ease. The uterus may herniate on the left or the right side of the abdomen. Af- fected animals have difficulty in lying down and getting up. Large left side herniation of the uterus may be asso- ciated with mild degree torsion of the uterus and would displace the rumen cranially with resultant rumen func- tion disorders. Herniations of a lesser degree result in a first stage labor without fetal delivery. The birth canal may be sometimes occluded. 2.7.2. Management of Dystocia In mid gestation herniations, support must be given to the abdominal floor by tying strong canvas around the abdomen. Such pregnancies would continue to term with support except, when the herniations are large sized. In herniations at or around parturition, it is better to restrain the animal in dorsal or lateral recumbency to assist the delivery of the fetus because the fetus may be beyond reach in a standing animal. An alternative is to raise the abdominal floor using a wooden plank or a strong can- vas held and lifted by two assistants. If vaginal delivery is not possible, then caesarean section must be per- formed. Further breeding from such animals should be discouraged. 2.8. Carcinoma of Urinary Bladder Carcinoma of the urinary bladder are extremely rare in the bovine species The transitional type cell carcinoma [85] seldom cause dystocia but result in dysuria, how- ever, squamous cell carcinoma are associated with ex- tensive fibrosis with metastasis in the wall of cervix, vagina and perivaginal adipose tissue resulting in marked constriction of the birth canal and dystocia. Clinically hard polypoid growths are palpable over many places in the birth canal. The affected animals show dy- suria and futile efforts to deliver the fetus [32]. Attempts to dilate the birth canal and deliver the fetuses by inject- ing estrogens and oxytocin usually fail and fetus can be delivered by caesarean section [32]. The dysuria contin- ues even after fetal deliveries and animals usually die or must be euthanized. 3. FAILURE OF THE EXPULSIVE FORCES Failure of expulsive forces could result because of the failure of abdominal or uterine expulsive forces. The condition where the uterine expulsive forces fail to de- liver a fetus is known as uterine inertia. The uterus qui- etens and the progression of the fetus out of the birth canal does not follow because of lack of contractions in the uterus. Uterine inertia is classified conventionally into primary and secondary uterine inertia [13,14,93]. 3.1. Primary Uterine Inertia In this condition, although the cervical dilation occurs and the fetus is in normal presentation, position and posture but it is not delivered due to lack of uterine con- tractions. The process of birth begins but do not continue into second sage labor. The most common cause of primary uterine inertia in dairy cows [13] and buffaloes [122] is considered to be hypocalcaemia, with the animal showing signs of milk fever as calving is about to begin. Over distension of the uterus because of dropsical fetal conditions, general de- bility and environmental disturbances are other causes. A few of the less common causes described [86] include inherited weakness of uterine muscle, toxic infections, myometrial degeneration, senility and nervousness. The incidence of uterine inertia is known to be 5.9 percent [7]. Therapy for dystocia management includes intrave- nous therapy with calcium borogluconate and 15 - 20 I.U of oxytocin IM or IV. When the cause is calcium defi- ciency animals will respond favorably and parturition process would begin. The fetus can be delivered after some time spontaneously or with little assistance. An injection of oxytocin must be given after removal of fetus to aid in uterine involution and placental expulsion. 3.2. Secondary Uterine Inertia Secondary uterine inertia occurs due to exhaustion as a result of dystocia [14]. When the uterine musculature becomes exhausted subsequent to failure of delivery of a maldisposed or oversized fetus or due to obstruction in the birth canal, then the condition is known as secondary uterine inertia. The contractions in the uterus then stop or become weak and transient. The animal shows no progress in parturition after the second stage of labor. The fetal membranes are ruptured and the cervix dilated. If dystocia is prolonged without fetal delivery, the fetal fluids are expelled out and the uterus contracts tightly around the fetus. It is necessary to correct the primary cause of dystocia and deliver the fetus. Doses of oxyto- cin must be given after fetal delivery to regain uterine contractility. Secondary uterine inertia invariably results in retention of the placenta.  G. N. Purohit et al. / Open Jour nal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 41-53 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 50 3.3. Uterine Rupture Rupture of the uterine wall can occur as a result of ac- cidental traumatic injuries, the presence of some weak points [13], or subsequent to severe uterine torsion, both in cows [123,124] and buffaloes [67,114, 125]. Uterine rupture is considered the result rather than the cause of dystocia [126] the predisposing causes being uterine tor- sion, breech presentation and abnormal fetal movement. Small tears are insignificant and the fetus may be deliv- ered without much difficulty. Large tears can result into passage of the fetus into the peritoneal cavity [108,127]. The resultant severe haemorrhage can result into mater- nal death. Loops of intestines or other visceral organs can prolapse through the vulva if the tear occurs at a time when the birth canal is sufficiently dilated. The general condition of the patient in such cases would be extremely poor. Such patients must be managed early with fluid therapy and laparotomy must be performed immediately. The fetuses whether present in the abdo- men or uterus must be removed and the uterine tear re- paired. Parts of the fetus may sometimes project into the peritoneum from the tear and the fetus develops nor- mally for some time, but such cases are rare. Examina- tions of such patients reveal the extra uterine presence of the fetus [128] and such animals may evidence colic or other clinical signs. The vaginal delivery of such fetus is extremely difficult and unrewarding and hence a laparo- tomy is suggested. 3.4. Failure of Abdominal Expulsive Forces The abdominal musculature plays an important part in the second stage of labour to expel the fetus. Failure of abdominal expulsive forces can occur due to painful conditions, tears in the muscles, or weak muscles as are seen in old and weak animals. Conditions like traumatic reticulitis/pericarditis, painful conditions of diaphragm or chest may cause voluntary inhibition of attempts to strain [13]. The birth fails to occur in such causes despite the presence of normal preparatory signs and first stage labor. In cases of abdominal distension fetus must be delivered with assistance with the patient in recumbent position. In conditions, like traumatic pericarditis a cae- sarean is suggested. REFERENCES [1] Kodagali, S.B. (2003) Notes on applied bovine reproduc- tion. Part II. In: Kodagali S.B. Ed., Bovine Obstetrics. Indian Society for the study of Animal Reproduction Gujarat Chapter Anand, Gujarat, India, 22-67. [2] Agarwal, S.K. and Tomer, O.S. (1998) Reproductive technologies in buffalo. Indian Vet. Res. Institute, Izat- nagar, 10. [3] Jainudeen, M. R. (1986) Reproduction in the water buf- falo. In: Current therapy in Theriogenology. Ed., Morrow DA WB Saunders Company, Philadelphia, 443-449. [4] Mody, M., Chauhan, R.A.S. and Shukla, S.P. (2002) Process of parturition in buffaloes. Indian Journal of Animal Reproduction, 23, 141-143. [5] Ramasamy, M. and Singh, M. (2002) A comparative study on normal and abnormal parturition in Karan Fries Cattle and Murrah buffaloes. National Symposium Re- pord. Technologies for Augmentation of Fertility in Livestock. Nov. 14-16, IVRI, India. Compendium of Ab- stracts. Pp. 148-149. [6] Manju, T.S. and Varma, S.K. (1985) Dystocia in buffa- loes. Indian Journal of Animal Reproduction, 6, 54-57. [7] Phogat, J.B., Bugalia, N.S. and Gupta, S.L. (1992) Inci- dence and treatment of various forms of dystocia in buf- faloes. Indian Journal of Animal Reproduction, 13, 69-70. [8] Berger, P.J., Cubas, A.C. and Koehler, K.J. (1992) Fac- tors affecting dystocia and early calf mortality in Angus cows and heifers. Journal of Animal Science, 70, 1775-1786. [9] Mee, J.F. (2008) Prevalance and risk factors for dystocia in dairy cattle. The Veterinary Journal, 176, 93-101. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2007.12.032 [10] Zaborski, D., Grzesiak, W., Szatkowska, I., et al. (2009) Factors affecting dystocia in cattle. Reproduction in Do- mestic Animals, 44, 540-551. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0531.2008.01123.x [11] Robert, S.J. (1986) Dystocia: In: Veterinary obstetrics and genital diseases. Ed. Roberts SJ CBS Publishers, New Delhi, 227-236. [12] Khammas, D.J. and Al-Hamedawi, T.M. (1994) Clinical investigation on bovine dystocia in Iraq. Indian Veteri- nary Journal, 71, 464-468. [13] Jackson, P.G.G. (1995) Dystocia in the cow: In: Hand- book of veterinary obstetrics. W.B. Saunders Co. Ltd., Philadelphia, 30-69. [14] Arthur, G.H., Noakes, D.E., Pearson, H., et al. (1996) Maternal dystocia treatment. In: Arthur, G.H. Ed., Vet- erinary Reproduction and Obstetrics. WB Saunders Philadelphia, Philadelphia [15] Saxena, O.P., Varshney, A.C., Jadon, N.S., et al. (1989) Surgical management of dystocia in bovine: A clinical study. Indian Vete rinary Journal , 66, 562-566. [16] Nanda, A.S., Brar, P.S. and Prabhakar, S. (2003) En- hancing reproductive performance in dairy buffalo: major constraints and achievements. Reproduction Supplement, 61, 27-36. [17] Singla, V.K., Gandotra, V.K., Prabhakar, S., et al. (1990) Incidence of various types of dystocias in cows. Indian Veterinary Journal, 67, 283-284. [18] Sharma, R.D., Dhaliwal, G.S., Prabhakar, S., et al. (1992) Percutaenous fetotomy in management of dystocia in bo- vines. Indian Veterinary Journal, 69, 443-445. [19] Singla, V.K. and Sharma, R.D. (1992) Analysis of 188 cases of dystocia in buffaloes. Indian Veterinary Journal , 69, 563-564. [20] Youngquist, R.S. (1997) Parturition and dystocia In: Youngquist, R.S., Ed., Current Therapy in Large Animal Theriogenology, WB Saunders Co. Philadelphia, 309-323. [21] Purohit, G.N. (2006) Maternal causes of dystocia in cows  G. N. Purohit et al. / Open Jour nal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 41-53 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 5151 and buffaloes. In: Suresh, S.H., Tandle, M.K. Eds., Ve t - erinary Obstetrics A Practical Guide, Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers, New Delhi, 16-25. [22] Srinivas, M., Sreenu, M., Lakshmi, R.N., et al. (2007) Studies on dystocia in graded Murrah buffaloes: A retro- spective study. Buffalo Bulletin, 26, 40-45. [23] Gupta, P.P. (1983) Infiltrative transitional-cell carcinoma of urinary bladder in a buffalo. Indian Veterinary Journal, 60, 934. [24] Gupta, P.P. and Kumar, N. (1986) Dystocia in buffaloes due to carcinoma of urinary bladder. Indian Veterinary Journal, 63, 508-510. [25] Singh, J., Prasad, B. and Rathore, S.S. (1978) Torsio uteri in buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis). An anlaysis of 65 cases. Indian Ve t erinary Journal , 55, 161-165. [26] Deshmukh, M.J. (1975) Clinical studies on problems of parturition and post parturient reproductive disorders in buffaloes. M.V.Sc. thesis, Punjabrao Krishi Vidyapeeth, Akola. [27] Markandeya, N.M., Pargaonkar, D.R., Panchbhai, V.S., et al. (1991) Vaginal obstruction in a pregnant Holstein Freisian heifer. Indian Journal of Animal Reproduction, 12, 98. [28] Nair, P.K. and George, V. (1993) A dorsoventral post-cervical band in a parous cross bred cow. Indian Journal of Animal Reproduction, 14, 128. [29] George, R.S., Balasubramanian, S., Ayyappan, S., et al. (1997) Dystocia due to infantile vulva in a heifer. Indian Veterinary Journal, 74, 620-621. [30] Balasubramanian, S., Asokan, S.A., Subramanian, A., et al. (1991) Dystocia with vaginal rupture in a heifer. In- dian Ve ter inary Journal, 68, 683-684. [31] Siddiquee, G.M. (1992) Protrusion of gravid uterus through ruptured vaginal wall in a buffalo: A case report. Indian Ve t erinary Journal , 69, 255-256. [32] Dhaliwal, G.S., Prabhakar, S. and Sharma, R.D. (1991) Spontaneous rupture of vagina in buffalo heifers. Indian Journal of Animal Reproduction, 12, 98-101. [33] Sood, P., Singh, M. and Vasistha, N.K. (2002) Uterine torsion in a goat. Indian Journal of Animal Reproduction, 23, 203. [34] Bennett, J., Kennel, A. and Stanhope, C.R. (1998) Surgi- cal correction for an aquired vaginal stricture in a llama using a carbon dioxide laser. Journal of American Vet- erinary Medical Association, 212, 1436-1437. [35] Omara-Opyene, A.L., Varma, S. and Sayer, P.D. (1985) Cryosurgery of bovine squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Veterinary Record, 117, 518-520. doi:10.1136/vr.117.20.518 [36] Meyers, S.A. and Read, W.K. (1990) Squamous cell car- cinoma of the vulva in a cow. Journal of American Vet- erinary Medical Association, 198, 1644-1646. [37] Saiyari, M., Naddaf, H. and Gooraninejad, S. (1994) Leiomyoma in the vagina of a cow. Indian Veterinary Journal, 71, 842-843. [38] Rama, R.P. and Rajya, B.S. (1976) A note on the neo- plasms of the female genital system of buffaloes. Indian Veterinary Journal, 53, 323-324. [39] Dhoble, R.L., Singh, M., Gupta, V.K., et al. (1992) Perivaginal granuloma in a buffalo. Indian Veterinary Journal, 69, 845-846. [40] Balasubramanian, S., Seshagiri, V.N., Subramanian, A., et al. (1991) Vaginal lipoma in a crossbred Jersey cow. Indian Ve t erinary Journal , 68, 1073-1074. [41] Dutta, J.C., Lahen, D.K., Bhattacharjee, M., et al . (1987) Fibroleiomyoma of vagina in two Jersey heifers. Indian J ournal of Animal Reproduction, 8, 66-68. [42] Sharma, G.P., Reddy, V.M., Hafeezuddin, M., et al. (1977) A note on fibroma of cervix in a buffalo cow. Indian Vet- erinary Journal, 54, 763. [43] Kohli, I.S. and Bishnoi, B.L. (1980) Pedunculated tu- mour (Fibroma) of cervix in a Rathi cow. Indian Veteri- nary Journal, 57, 511. [44] Ryot, K.D. (2000) Multiple cervical tumours as the cause for recurrent vagino cervical prolapse in a cross bred cow —A case report. Indian Journal of Animal Reproduction, 21, 78. [45] Sharma, S.S., Bishnoi, B.L. and Purohit, G.N. (2001) A case of cervical pedunculated fibroma durum in a Rathi cow. Veterinary Practitioner, 2, 170-171. [46] Bakshi, S.A., Panchbhai, V.S., Pargaonkar, D.R., et al. (1986) Fibro adenoma of cervix in a pregnant non-descript cow. Indian Journal of Animal Reproduc- tion, 7, 140-141. [47] Sidhaye, J. (1982) Cervical fibroleiomyoma in a cross- bred cow. Indian Ve terinary Journal, 59, 566-567. [48] Roesti, A. (1986) Fibroleiomyoma of the cervix in a cow. Veterinary Medical Review, 2,198-199. [49] Pandit, R.K., Nema, S.P. and Garg, U.V. (1990) Success- ful treatment of cervical fibroleiomyoma in a crossbred cow. Indian Journal of Animal Reproduction, 11, 72-73. [50] Vasistha, N.K., Sood, P., Singh, M., et al. (2000) Squamous cell carcinoma of cervix in a cow. Indian Journal of Animal Reproduction, 21, 165. [51] Devanathan, T. G., Asokan, S.A., Rajasundaram, R.C., et al. (2000) A case report of nebothian cyst in a crossbred cow. Indian Journal of Animal Reproduction, 21, 79. [52] Kumar, N. and Singh, B. (1984) Some neoplasms in- volving female genitalia of buffaloes. Indian Veterinary Journal, 61, 185-187. [53] Paikne, D.L. and Pathak, V.P. (1989) A note on the oc- currence of uterine polyps in a Sahiwal cow. Indian Journal Animal Reproduction, 10, 170-171. [54] Purohit, G.N., Kumar, D., Garg, N., et al. (2004) Suc- cessful removal of a fibroma from the uterus of a cow. Acta Veterinaria Hungarica, 52, 47-50. doi:10.1556/AVet.52.2004.1.5 [55] Samad, H.A., Ali, C.S., Ahmad, K.M.Z., et al. (1994) Reproductive disease of the water buffalo Proc. 10th Int Congr Anim Reprod and AI, Urbana. 4, 14-25. [56] Ducharme, N.G. and Stem, E.S. (1981) Eversion of uri- nary bladder in a cow. Journal of American Veterinary Medical Associati on, 179, 996-998. [57] Benesch, F. and Wright, J.G. (2001) Veterinary Obstetrics. Greenworld Publishers, India, 75-89. [58] Sane, C.R., Luktuke, S.N., Deshpande, B.R., et al. (1982) Reproduction in Farm Animals. Varghese Publishing House, Bombay, India. [59] Kindahl, H. (2000) Endocrine changes in late bovine pregnancy with special emphasis on fetal well being. Domestic Animal Endocrinol ogy, 23, 321-328. doi:10.1016/S0739-7240(02)00167-4 [60] Rajabi, M.R., Dean, D.D., Beydoun, S.N., et al. (1988) Elevated tissue levels of collagenase during dilation of  G. N. Purohit et al. / Open Jour nal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 41-53 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 52 uterine cervix in human parturition. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 159, 971-976. [61] Breeveld, D.V.N., Strujik, P.C., Lotgering, F.K., et al. (2003) Cervical dilation related to uterine electromyog- raphic activity and endocrinological changes during prostaglandin F (2 alpha)—induced parturition in cows. Biology of Reproduction, 68, 536-542. [62] Mannari, M.N. (1969) Cervical non-dilation in buffaloes. Gujarat Ve t erina rian, 3, 37-38. [63] Deshmukh, M.L. and Kaikini, A.S. (1976) Studies on problems of parturition in buffaloes-I. Maternal dystocia. Indian Ve t erinary Journal , 53, 212-213. [64] Maul, H., Nagel, S., Welsch, G., et al. (2002) Messenger ribonucleic acid levels of interleukin-1 beta interleukin-6 and interleukin—8 in the lower uterine segment in- creased significantly at final cervical dilation during ter- minal parturition, while those of tumour necrosis factor remained unchanged. European Journal of Obstetrics Gynaecology and Reproductive Biology, 102, 143-147. doi:10.1016/S0301-2115(01)00606-6 [65] Kemp, B., Menon, R., Fortunato, S.J., et al. (2002) Quantitation and localization of inflammatory cytokines, interleukin—6 and interleukin-8 in the lower uterine segment during cervical dilation. Journal of Assisted Re- production and Genetics, 19, 215-219. doi:10.1023/A:1015354701668 [66] Das, G.K., Ravinder, K., Deori, S., et al. (2008) Incom- plete cervical dialation causing dystocia in a buffalo. In- dian Journal of Veterinary Research, 17, 51 [67] Wehrend, A. and Bostedt, H. (2003) The incidence of cervical dystocia and disorders of cervical involution in the post partum cow. Deutsche Tierarzlithe Wochen- schrift, 110, 483-486. [68] Zhang, W.C., Nakao, T., Moriyoshi, M., et al. (1999) Relationship of maternal plasma progesterone and es- trone sulfate to dystocia in Holstein Friesian heifers and cows. The Journal of Veterinary Medical Science, 61, 909-913. doi:10.1292/jvms.61.909 [69] Kelly, A.J., Kavanagh, J. and Thomas, J. (2001) Relaxin for cervical ripening and induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2, CD 003103. [70] Kanakapur, D.K., Krishnaswamy, A. and Dubey, B.M. (1999) Studies on some factors influencing treatment and maternal recovery rate in uterine torsion among cross- bred dairy cattle. Indian Journal of Animal Reproduction, 20, 31. [71] Murty, K.K., Prasad, V. and Murty, P.R.K. (1999) Clini- cal observations on uterine torsion in buffaloes. Indian Veterinary Journal, 76, 643-645. [72] Mogha, I.V., Das, S.C. and Bhattacharya, A.R. (1976) Bovine uterine torsion. A case report. Indian Veterinary Journal, 53, 373-376. [73] Sharma, S.P., Agarwal, K.B.P. and Singh, D.P. (1995) Torsion of gravid uterus and laparohysterotomy in bovine. A report on 72 clinical cases. Indian Veterinary Journal, 74, 1180-1182. [74] Prasad, S., Rohit, K. and Maurya, S.N. (2000) Efficacy of laparohysterotomy and rolling of dam to treat uterine torsion in buffaloes. Indian Veterinary Journal, 77, 784-786. [75] Matharu, S.S. and Prabhakar, S. (2001) Clinical observa- tions and success of treatment of uterine torsion in buf- faloes. Indian Journal of Animal Reproduction, 22, 45-48. [76] Manju, T.S. and Varma, S.K. (1985) Dystocia in buffa- loes. Indian Journal of Animal Reproduction, 6, 54-57. [77] Mathijsen, H.F. and Putker, P.H. (1989) Postpartum tor- sion of the right uterine horn in a cow. Kijdschr Dier- geneeskd, 114, 17-19. [78] Singla, V.K., Sharma, R.D., Dhaliwal, G.S., et al. (1992) Uterine torsion in cows—an analysis of 34 cases. Indian Veterinary Journal, 69, 281-282. [79] Roberts, S.J. (2002) Diagnosis and treatment of dystocia. In: Roberts S.J., Ed., Veterinary Obstetrics and Genital Diseases, Indian edition CBS Publishers, New Delhi, 274-299. [80] Prabhakar, S., Singh, P., Nanda, A.S., et al. (1994) Clinico obstetrical observations on uterine torsion in bo- vines. Indian Veterinary Journal, 71, 822-824. [81] Purohit G.N. and Mehta J.S. (2006) Dystocia in cattle and buffaloes: A retrospective analysis of 156 cases. Veteri- nary Practitioner, 7, 31-34. [82] Penny, C.D. (1999) Uterine torsion of 540º in a mid ges- tation cow. Veterinary Record, 145.230. [83] Ruegg, P.L. (1988) Uterine torsion of 720 degrees in a midgestation cow. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Associati on, 192, 207-208. [84] Dhaliwal, G.S., Sharma, R.D., Singla, V.K., et al. (1988) Torsion of didelphic uterus in a cow. Indian Journal of Animal Reproduction, 9, 71-72. [85] Dhaliwal, G.S., Prabhakar, S. and Sharma, R.D. (1989) A note on reoccurrence of uterine torsion in a cow with didelphic uterus. Indian Journal of Animal Reproduction, 10, 171-172. [86] Biggs, A. and Osborne, R. (2003) Uterine prolapse and mid pregnancy uterine torsion in cows. Veterinary Re- cord, 152, 91-92. [87] Jadhao, P.T., Markandeya, N.M. and Rautmare, S.S. (1993) Uterine torsion along with haemoperitoneum in a buffalo. Indian Journal of Animal Reproduction, 14, 59. [88] Siddiquee, G.M. and Mehta, B.M. (1992) Uterine torsion in a buffalo with viable twins. Indian Veterinary Journal, 69, 257-258. [89] Nanda, A.S., Sharma, R.D. and Nowshahari, M.A. (1991) The clinical outcome of different regimes of treatment of uterine torsion in buffaloes. Indian Journal of Animal Reproduction, 12, 197-200. [90] Ahmed, M., Choudhary, R.A. and Khan, I.H. (1980) Torsion of uterus as a cause of dystocia in the buffalo. Pakistan Veterinary Journal, 1, 22-24. [91] Foud, K. and El-Sawaf, S. (1964) Some observations on torsio-uteri in buffaloes with special reference to its etio- logical factors. Veterinary Medical Journal Giza, 9, 173-177. [92] El Naggar, M. (1978) Uterine torsion in buffaloes. Indian Veterinary Journal, 55, 61-67. [93] May, J.A. (1950) Torsio uteri. Tierazzt. Umsch 5, 1259-1260. [94] Pearson, H. (1971) Uterine torsion in cows. Veterinary Record, 89, 597-599. doi:10.1136/vr.89.23.597 [95] Pattabiraman, S.R., Singh, J., Rathore, S.S., et al. (1979) Non surgical method of correction of bovine uterine tor- sion-A clinical analysis. Indian Veterinary Journal, 56, 424-428.  G. N. Purohit et al. / Open Jour nal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 41-53 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/Openly accessible at 5353 [96] Nanda, A.S. (1995) Recent advances in animal reproduc- tion and gynaecology. USG Publishers and Distributors, Ludhiana. [97] Singh, P. (1995) Recent observations on etiology and treatment of uterine torsion in buffaloes. In: Nanda, A.S. Ed., Recent Advances in Animal Reproduction and Gy- naeoclogy, USG Publishers and Distributors, Ludhiana, 137-141. [98] Singh, P., Prabhakar, S., Kochar, H.P., et al. (1995) Uterus didelphus-a cause of torsion of uterus in a buffalo. Indian Ve t erinary Journal , 72, 172-173. [99] Singh, P. (1991) Studies on broad ligament in relation to uterine torsion in buffaloes. M.V.Sc Thesis; Punjab Ag- ricultural University, Ludhiana. [100] Singh, P., Sharma, R.D., Saigal, R.P., et al. (1992) Uter- ine torsion in buffaloes. National symposium on Recent Advances in Clinical Reproduction in Dairy Cattle, Chennai, 45. [101] Agarwal, R.G. (1987) Some studies on uterine torsion with special reference to its etiology and treatment in buffaloes. Ph.D. Thesis, Punjab Agricultural University, Ludhiana. [102] Deori, S., Kumar, R. and Jaglan, P. (2009) Post cervical uterine torsion in a buffalo-a case study. Indian Journal of Animal Reproduction, 30, 85. [103] Mannari, M.N. and Tadkod, D.M. (1976) Uterine torsion in buffaloes. Indian Journal of Animal Sciences, 10, 83. [104] Wright, J.G. (1958) Bovine dystocia. Veterinary Record, 70, 347-356. [105] Phogat, J.B., Bugalia, N.S., Verma, S.K., et al. (1991) Plasma cholesterol and haemogram in buffaloes affected with uterine torsion. Indian Veterinary Journal, 68, 1048-1052. [106] Singla, V.K., Sharma, R.D., Gandotra, V.K., et al. (1992) Changes in certain serum biochemical constituents in buffaloes with uterine torsion. Indian Veterinary Journal, 69, 805-807. [107] Frazer G.S. (1988). Uterine torsion followed by a jejunal incarceration in a partially everted urinary bladder of a cow. Australian Veterinary Journal, 65, 24-25. doi:10.1111/j.1751-0813.1988.tb14925.x [108] Matharu, S.S. and Prabhakar, S. (1999) Blood histamine levels in buffaloes after detorsion of uterus and/or cae- sarean section. Indian Veterinary Journal, 76, 524-526. [109] Prabhakar, S., Dhaliwal, G.S., Sharma, R.D., et al. (1997) Success of treatment and dam survival in bovines with precervical uterine torsion. Indian Journal of Animal Re- production, 18, 121-123 [110] Singh, J. and Dhaliwal, G.S. (1998) A retrospective study on survivability and fertility following cesarean section in bovines. Indian Journal of Animal Reproduction, 19,21-23 [111] Arthur, G.H. (1966) Recent advances in bovine obstetrics. Veterinary Record, 79, 630-640. doi:10.1136/vr.79.22.630 [112] Prakash, S. and Nanda, A.S. (1996) Treatment of uterine torsion in buffaloes-modification of Schaffers method. Indian Journal of Animal Reproduction, 17, 33-34. [113] Singh, P. and Nanda, A.S. (1996) Treatment of uterine torsion in buffaloes. Modification of Schaffer’s method. Indian Journal of Animal Reproduction, 17, 33-34. [114] Dhaliwal, G.S., Prabhakar, S. and Sharma, R.D. (1993) Torsion of pregnant uterine horn in a cow. A case report. Indian Journal of Animal Reproduction, 14, 129. [115] Prasad, S., Singh, O.V., Dabas, Y.P.S., et al. (1998) Clini- cal management of delayed uterine torsions of more than 360° in buffaloes. Case reports. Indian Veterinary Jour- nal, 75, 890-891. [116] Mandal, P.K., Luthra, R.A. and Arya, S.C. (2002) Histo- pathological observations on buffalo uterus affected with uterine torsion. National Symposium on Reproductive Technologies for Augmentation of Fertility in Livestock. Indian Veterinary Research Institute, Compendium of Abstracts, Bareilly, 14-16 November 2002, 146-147. [117] Singh, M., Singh, M. and Kumar, V. (1998) Rupture of uterus following uterine torsion in a buffalo-a case report. Indian Journal of Animal Reproduction, 19, 71. [118] Varshney, A.C., Kumar, A. and Singh, H., et al. (1992) Studies on haematological and biochemical alterations following caesarean section in cows. Indian Veterinary Journal, 69, 632-636. [119] Riebold, T.W. (2001) Anaesthetic management of cattle. In: Steffy, E.P. Ed., Recent Advances in Anaesthetic Management of Large Domestic Animals., International Veterinary Information Service, Ithaca, (www.ivis.org), A 0603.0201. [120] Caroll, G.L. and Hartisfield, S.M. (1996) General anaes- thetic techniques in ruminants. Veterinary Clinics of North America: F o od Animal Practice, 12, 627-661. [121] Auld, W.C. (1947) Correction of uterine torsion by ab- dominal ballotment. Veterinary Record, 59, 287. [122] Pargaonkar, M.D., Tandle, M.K., Goswami, J.D., et al. (1993) Maternal dystocia followed by uterine prolapse in a buffalo. A case report. Indian Journal of Animal Re- production, 14, 125. [123] Arthur, G.H. and Jenner, F.H.J. (1969) Uterine rupture in cows. Veterinary Record, 72, 263. [124] Verma, S.K., Tyagi, R.P.S. and Manohar, M. (1974) Cae- sarean, section in bovine: A clinical study. Indian Veteri- nary Journal, 51, 471-479. [125] Hoque, M. (1991) Rupture of uterus with displacement of fetus into the peritoneal cavity in a cow: A case report. Indian Ve t erinary Journal , 68, 271-272. [126] Pearson, H. and Denny, H.R. (1975) Spontaneous uterine rupture in cattle: A review of 26 cases. Veterinary Record, 97, 240-244. doi:10.1136/vr.97.13.240 [127] Rao, A.V.N. and Sreemannarayana, O. (1984) Full term extra uterine pregnancy in a Murrah buffalo cow. Indian Veterinary Journal, 61, 809-810. [128] Rajasekaran, J., Thangaraj, T.M. and Venkataswami, V. (1991) Extra uterine pregnancy in a cow. Indian Journal of Animal Reproduction, 12, 204.

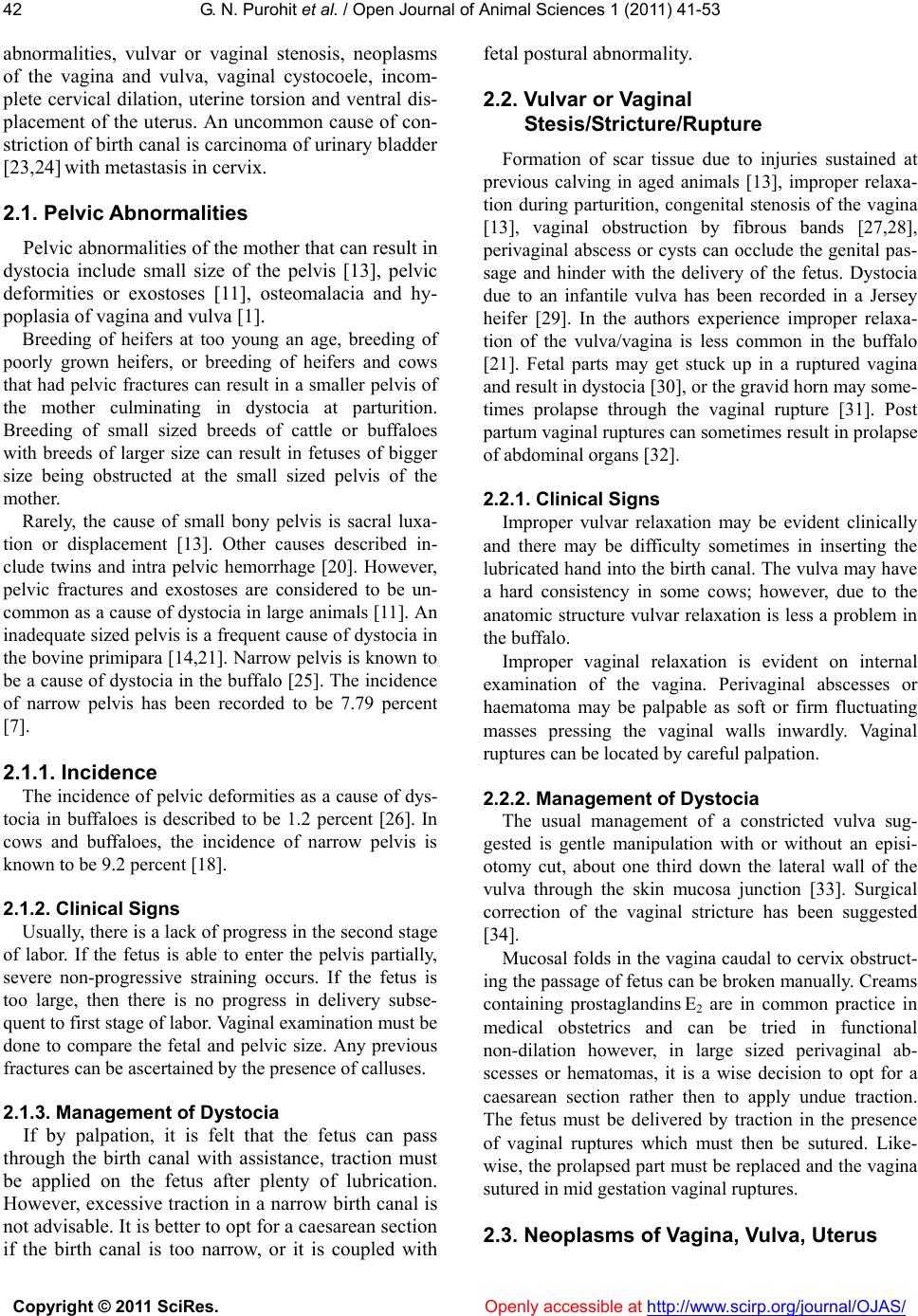

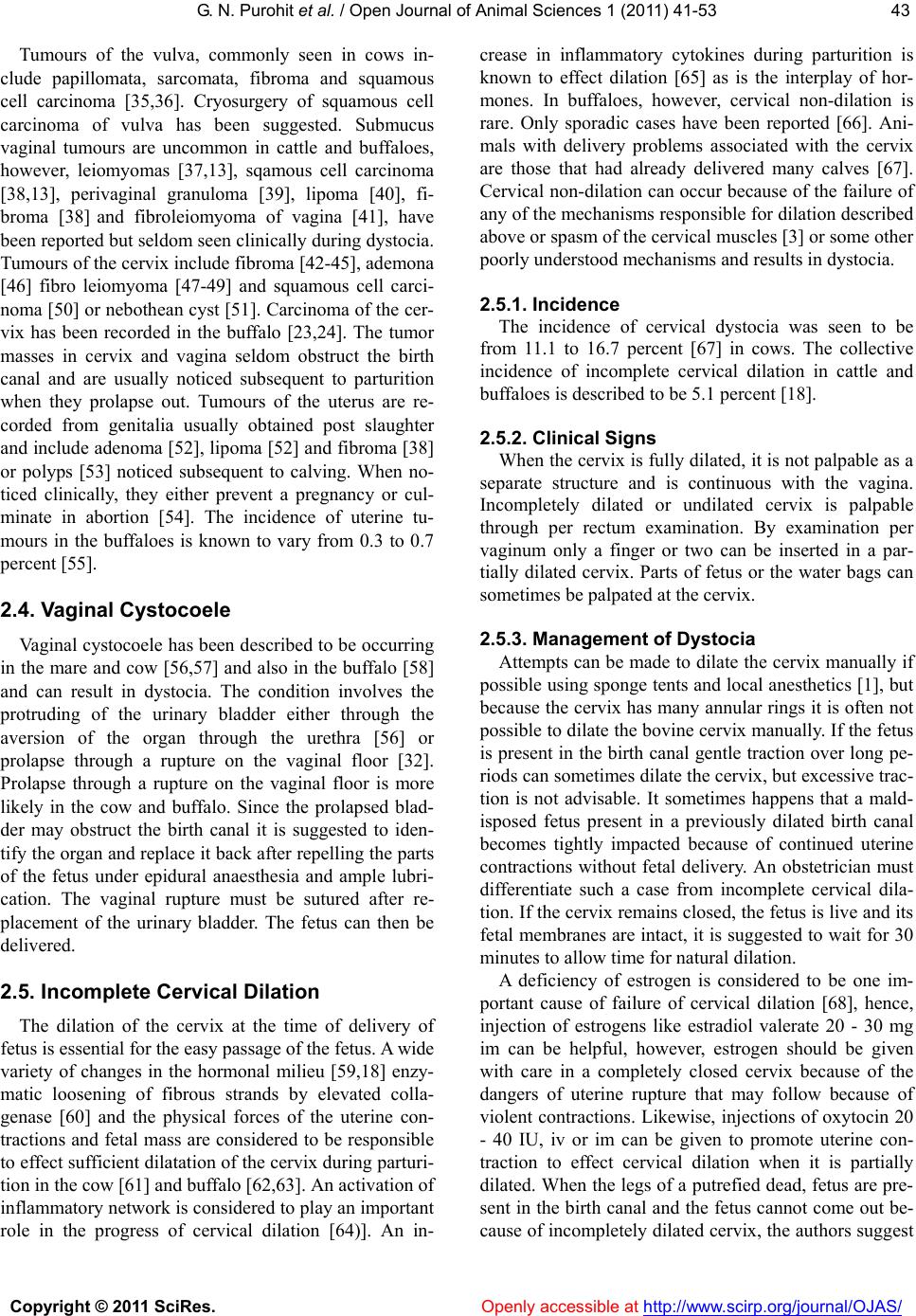

|