iBusiness

Vol.3 No.3(2011), Article ID:7476,9 pages DOI:10.4236/ib.2011.33036

Chinese Knowledge Employees’ Career Values, Perceived Organizational Support and Career Success*

![]()

Zhejiang Gongshang University, Hangzhou, China.

Email: yuchensf@163.com

Received July 26th, 2011; revised August 28th, 2011; accepted September 10th, 2011.

Keywords: Career Success, Knowledge Employees, Career Values, Perceived Organizational Support

ABSTRACT

Purpose: the purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of career values and perceived organizational support on career success and to examine what career values are. Design/Methodology: survey data were collected from a sample of 151 Chinese knowledge employees. Career success was measured by subjective, that is career satisfaction. Findings: 1) There were three dimensions of career values, and they are self-achievement, factor hygienic factor and prestige factor. 2) Career values and organizational support can predict career success. Implications: knowledge of the antecedents to career success should provide certain advantages to organizations attempting to select and motivate employees. Originality/value: this paper makes a valuable contribution to career success literatures by being one of the first to examine the effect of career values on career satisfaction.

1. Introduction

Career success has been an important and popular focus of investigation in the management literature since 1980s. Career success is defined as the accumulated positive work and psychological outcomes resulting from one’s work experiences [1]. It improves individuals’ quantity or quality of life, in fact, career success also is the real or perceived achievements individuals have accumulated as a result of their work experiences.

There has been more information produced in the last 60 years than that produced during the previous 2000 years. Information is very important to everyone. We define the people who access and use significant portions of the information resources as knowledge employees/ workers. Organizational success will be based not just on what the growing number of knowledge employees know, but on how fast they can learn and share their knowledge, the latter is related to career success.

Career success is of concern not only to knowledge employees but also to organizations. At the individual level, career success refers to acquisition of materialistic advancement, power, and satisfaction [2-4]. Thus, individuals with high career success feel happier and more successful about their careers relative to their own internal standards. Knowledge of career success helps knowledge employees develop appropriate strategies for career development [5,6]. Therefore, knowledge employees’ personal success can eventually contribute to organizational success [7].

At the employer level, knowledge of the relationship between predictors (such as career values and perceived organizational support) and career success can help employer design effective career systems and policy.

Sociological research on the determinants of career careers is quite extensive. A recent review of the career success literature identified several categories of influences on career success [8]. The most commonly investigated influences were human capital attributes (training, work experience, education) and demographic factors (age, sex, marital status, number of children). Although these classes of influences have provided important insights into the determinants of career success, there is room for further development. Specifically, little research has examined the relationship career values and career success.

The most recent and encompassing studies on the relationship between various predictors and career success [1,7,9] are mostly based on relatively selective US samples with a narrow range of occupations. Our study seeks to improve on these earlier studies. We analyze pooled cross-sectional data of China. The nature of these samples allows us to investigate career success for the bigger range of occupations. Furthermore, we gain insight into the extent to which psychological factors relate to career success in non-US samples.

The purpose of this paper is to examine the correlates of career values, organizational support and career success. Specifically, our interest lies predominately with the dimensions of career values.

In spite of the importance and intuitive appeal of the concept of career values to career success, there has been much less research attention to these, in contrast with the much more frequently studied (and measured) constructs of personality, abilities, and human capital.

2. Related Literature and Hypothesis

2.1. Career Satisfaction

A person’s career can be defined as an ongoing sequence of education and work activities that are meaningful to the individual and that add value to the organizations in which the individual participates.

Career success has also been defined as objective and subjective elements of achievement and progress of an individual through the vocational lifespan. Career success has two kinds of components: extrinsic and intrinsic. Extrinsic success is relatively objective and observable, and typically consists of highly visible outcomes such as pay, ascendancy, promotions, and/or position [10,11]. Conversely, intrinsic success is defined as an individual’s subjective reactions to his or her own career, and is most commonly operationalized as career satisfaction [2,3]. Organizations might be especially care about objective career success (e.g. an individual’s achievements in terms of pay, position, promotions, and performance), individuals might be interested in subjective career success (e.g. positive career-related perception). By far, subjective career success has been the most widely used in previous literature. On the other hand, satisfaction with one’s career is a standard for assessing the quality of one’s career experiences.

Success is an evaluative concept, evaluation requires judges and a criterion against which an outcome can be assessed. Research concerned with success must therefore consider to whom and by what criteria a given indicator connotes success. The most meaningful distinction about who is judging success is probably whether individuals are judging their own success or others are judging for them. If success is to be judged reliably by others, the criteria used must be relatively objective and visible to others. When individual career success can be defined as the real or perceived achievements individuals have accumulated as a result of their work experiences [3]. Consistent with previous research, we chose to partition career success into extrinsic and intrinsic components. Extrinsic success is relatively objective and observable, and typically consists of highly visible outcomes such as pay and ascendancy [10]. Although individuals probably also assess their own success by these objective criteria, more subjective measures are needed to tap possible individual differences in feelings about these objective accomplishments; examples of measures that have been used include job satisfaction and employment goals reached.

Researchers from a wide variety of disciplines continue to investigate many psychological characteristics that could contribute to career success. For example, Thomas & Daniel [12] examined the mediating processes through which human capital (e.g. education and work experience) contribute to objective indicators of career success (e.g. salaries and promotions). Career choice [2], success criteria [4] are also some examples of more recent determinants of career success that have been examined. In one extensive cross-organization study, Judge et al. [3] surveyed 1400 executives in a diverse sample of US organizations, examining the extrinsic career success and intrinsic career success. They found that demographic, human capital, and motivational variables had important effects on career success, but they did not examine the role of psychological factors.

It is important to point out that work values are found to be important in many other related domains of organizational behavior, including organizational commitment [13], and job satisfaction [14-16].

Work values are individual intrinsic factor, career success can be affected by external factor, such as organizational support, at the same time, and the study will focus on perceived organizational support, which influences career success.

2.2. Career Values and Career Satisfaction

Work values and their structures are well studied in Western countries since 1970’s [14,17]. In the past 40 years an increasing amount of attention has been directed at the effect of work values on employee attitudes and behaviors [13,18].

Values are different from needs, work values represent what the individual wanted to obtain from work. Job need has a much more powerful effect job satisfaction. When job needs are satisfied, individual job satisfaction will increase irrespective of whether he or she values that reward highly. At the same time, work values have an independent effect on job satisfaction. However, this effect maybe weaker and negative; that is, if an individual values something highly, he or she is likely to be less satisfied, because it is for her or him less likely to obtain a high satisfactory level.

Nearly 30 years ago, Jurgensen [17] asked 57,000 job applicants of a public utility to rank the importance of 10 factors that make a job good or bad. The order for men is security, advancement, type of work, company, pay, coworkers, supervisor, benefits, hours, and working conditions. Women consider type of work more important than any other factor, followed by company, security, coworkers, advancement, supervisor, pay, working conditions, hours, and benefits. Preferences attributed to others differ markedly from self-preferences, with both men and women believing pay is most important to others. In his study, importance of a job represented work values, in fact.

Super [19] constructed a prototype version of 15 statements as an inventory to evaluate the job characteristics, each one. The version published in 1964 also consisted of pair comparisons of single statement scales, which resulted in a total of 120 items. In later iterations, the 1970 version presented 15 scales of three item each, with responses on a 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 (unimportant) to 5 (very important). The scales in this version were as follows: Altruism, Esthetics, Creativity, Intellectual Stimulation, Achievement, Independence, Prestige, Management, Economic Returns, Security, Surroundings, Supervisory Relations, Associates, Way of Life, and Variety.

Robinson, & Betzfactor [20] defined work values as four theoretically consistent underlying factors, as follows: Environment, Esteem, Excitement, and Safety.

Kalleberg [14] defined work values as general attitudes regarding the meaning that an individual attaches to the work role. That is, they represent what the individual pay importance on job’s reward. Logically, career values can be defined as general attitudes regarding the meaning that an individual attaches to the career role, which represent what the individual career about career’s reward.

Thus, we believe it is reasonable to expect that:

H1: There were three dimensions of career values, they are self-achievement, factor hygienic factor and prestige factor.

In Super’s [19] life-span theory of career development, emphasized the core concept of “role” (i.e., child, student, citizen, worker, and homemaker) and acknowledged the importance of work-related values in the development of an individual’s role concepts.

Work values are viewed as the predictor of job satisfaction and other reactions to job. That is, work values are useful in explaining work behavior, Shapira, Z. & Griffith, T. L. [18] found work values can predict behavioral outcomes such as performance, organizational commitment. Mottaz [13] demonstrated that the effect of education on organizational commitment is, for the most part, through intrinsic rewards and work values. Empirical evidence supported the relationship between work values and job satisfaction and other reactions to work. For example, Kalleberg [14] found work values had independent-effects on job satisfaction. In addition, Watson, J.M. and Meiksins, P. F. [21] affirmed that the content of engineers’ work-that is, the level of challenge and the intrinsic interest of the work is the central predictor of their satisfaction.

In accord with this previous work, we replicate and test the relationship between career values and career satisfaction in China. In doing so, we argue that the careers literature can gain from testing western theorizing of work values/job satisfaction relationship outside the USA in order better to understand the career values involved in the career success process.

One of the main reasons for the interest in career values is the belief that it is a much more stable attitude than organizational support, human capital, and hence is a more useful measure of an individual’s response to his career. Another reason is career values should be a more effective and reliable predictor of career success.

In a word, work values can predict job satisfaction, it is logical to hypothesis career values are positive related to career satisfaction. Thus, we hypothesize:

H2: Career values will be positively related to career satisfaction.

Although we draw from research relating work values to job performance/satisfaction in developing our hypotheses, career satisfaction is conceptually and empirically distinct from these work outcomes. Job performance reflects one’s level of effectiveness in performing specific job tasks and duties and is measured with respect to a specific job [22]. In contrast, career satisfaction represents the material rewards an individual accumulates over a sequence of jobs [3].

2.3. Perceived Organizational Support and Career Satisfaction

Past research has suggested that organizational-level factors need to be taken into account when investigating the antecedents and correlates of career satisfaction. In this study we analyze how perceived organizational support relate to knowledge employees’ career satisfaction.

The attention on perceived organizational supports has increased since 1980s. Perceived organizational support (POS) refers to employees’ beliefs concerning the extent to which the organization values their contribution and cares about their well-being [23]. Previous empirical studies support that perceptions of organizational support was related to job performance, job satisfaction, affective commitment and job induced tension [24]. Several studies reported employees’ perception of being valued and cared about by the organization and organizational affective commitment to be strongly related [23,25].

Chen & Fang [26] found when perceptions of organizational politics are low, employees who engage in high levels of job-focused impression management tactics are more likely to gain better ratings than those who employ low-level tactics. We can use social exchange view to explain the reciprocal effect of commitment between the employee and organization.

Riggle, Edmondson, & Hansen [27] conducted a metaanalysis examining the effects of perceived organizational support on four employee outcomes: organizational commitment, job satisfaction, performance, and intention to leave. They did this through a main-effect meta-analysis of studies addressing these relationships over the last twenty years. They found job satisfaction (r = 0.61, p < 0.001) exhibit strong positive relationships with POS. Kwak, et al. [28] also confirmed job satisfaction was directly correlated with burnout and organizational support. DeConinck [29] examined the role of perceived support as a mediator between organizational justice and trust, the results indicated that perceived organizational support serves as a mediator between procedural justice and organizational trust.

Given the positive effect of POS on employee commitment and job satisfaction [30], it seems logical to suggest that perceived organizational support is related to career satisfaction as well. Rhoades and Eisenberger [30] found POS to be positively associated with opportunities for greater recognition and pay and promotion. Within the work field, POS may emanate either from the supervisor or other senior managers. Supportive supervisors affect individuals’ willingness to engage in development activities [31] and are critical for subordinate performance and career success. In some organizations, for example, social support provided by supervisor may take the form of career guidance and information, learning opportunities and challenging work assignments that promote career advancement [22]. For example, Dreher and Ash [32] found mentorship to be related to both objective and subjective measures of career success. Kirchmeyer [33] found supervisor support significantly predicted men’s and women’s managerial perceived career success and Greenhaus et al. [22] found supervisor support to be significantly related to employees’ career satisfaction. Whitely et al. [34] examined mentoring and socioeconomic origins as antecedents of early career outcomes for salaried managers and professional graduates working in various organizations. Other researchers found that mentorship and supportive work relationships were related to career advancement as well as perceived career success [35]. Wallace [36] found that mentoring for female lawyers increased their career satisfaction. Nabi [37] suggested social support to fall into three categories: personal, peer, and network. He found peer support to be strongly related to men’s subjective career success, whereas personal support to be strongly related to women’s subjective career success.

Barnett et al. [38] examined the relationship between organizational support for career development and employees’ career satisfaction. Based on an extended model of social cognitive career theory and an integrative model of proactive behaviors, their study proposed that career management behaviors would mediate the relationship between organizational supports career development and career satisfaction, and between proactive personality and career satisfaction.

It is reasonable that perceived social/organizational support at work in the form of mentorship, training, caring benefit and supportive work relationships would lead to greater career opportunities and enhanced career satisfaction. Hence, we propose that perceived organizational support at work would lead to greater career opportunities and enhanced career satisfaction.

Based upon the above, we develop hypothesis:

H3: There will be a positive relationship between perceived organizational support and career satisfaction. Knowledge employees who perceive high levels of organizational support will report greater career satisfaction than those who perceive low levels of support.

3. Participants

The data for this study were obtained 151 knowledge employees from many companies, such as manufacturing company, consulting company, high technology companies and so on. Job titles included managers (82%), technology personnel (18%). Of the total sample, 47.8% were male and 52.2% were female. Relative frequencies by age group were: 25 to 29, 65.7%; 30 to 39, 29.9%, 40 to 49, 5.2%,older 50, 2.4%.

A recent comparative study of nine countries found no differences in career success based on occupation or country and most demographic variables [39]. Another comparative study of Australian and Malaysian managers also found no significant differences between the two groups with regard to career identity and career planning commitment [40]. Therefore, we expect career values and perceived organizational support to influence career success as predicted by western models of career success though little research addressing the specific issues of this study in a cross-cultural context.

4. Variable Measurement

Career success is defined as the satisfaction individuals derive from intrinsic and extrinsic aspects of their careers, including pay, advancement, and developmental opportunities [3]. Career success captures an individual’s long term satisfaction with his/her career [3].

Career success is an evaluative concept. Evaluation requires judges and a criterion by which an outcome can be assessed. Therefore, research related to career success must consider to by what criteria. Judge their own career success, individuals can use internalized aspirations and feelings that are not visible to others as criteria; the results of such judgments are relatively subjective internal states or feelings. In the study, career success is evaluated by subjective feelings, career satisfaction.

Career satisfaction was measured with the eight-item scale developed by Judge [7], which measure subjective career success. The eight items are: 1) I am satisfied with income; 2) I am satisfied with degree to which work involves interests; 3) I am satisfied with coworkers; 4) I am satisfied with use of skills and abilities; 5) I am satisfied with supervision; 6) I am satisfied with ability to develop ideas on job; 7) I am satisfied with respect that others give to job; 8) I am satisfied with satisfaction with job security. Judge [7] reported an acceptable level of internal consistency for this scale (alpha = 0.92). In the present study, the coefficient alpha reliability estimate was 0.88.

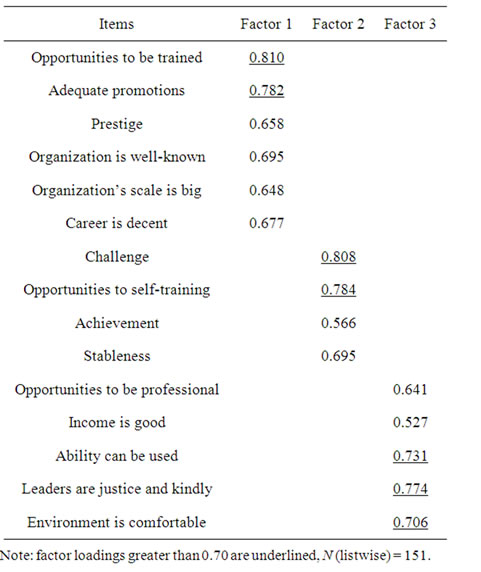

The following question in the survey assessed career values: “On these cards, there are various aspects of careers how important do you personally consider there careers characteristics? Please use the scale from 1 to 5 for your answers. The response scale was unlabeled except for the endpoints unimportant (1), and very important (5). The cards showed are the 15 career values items in Table 1.

In a previous longitudinal study [41], six of the ten items loaded on “formal” organizational support career development (e.g. “I have been given work which has developed my skills for the future”) and four items loaded on “informal” OSCD (e.g. “I have been encouraged to obtain a mentor to help my career development”). In this study, five of the items indicating the extent to which they perceived organizational support were modified slightly to reflect a supportive, rather than directive organizational relationship with employees. In this study, the POS had an alpha reliability of 0.85.

At the same time, several measures were employed as control variables (e.g. age, education and tenure).

5. Result

We factor analyzed the fifteen career values items. Using a varimax rotation, the factor analysis results are dis

Table 1. Factor analysis of career values measures (N = 151).

played in Table 1. As is shown in the table, the factor analysis identified three factors with Eigenvalues greater than 1.0. Cumulatively, the three factors explained 65.9% of the variance in the measures. Examination of the scree plot showed a distinct break between the slope of the three factors and those of the subsequent factors whose Eigenvalues were less than 1.0. As can be seen in the table, the six career values items about self-achievement loaded strongly on Factor 1 (the average factor loading was 0.712). Thus, this factor can be labeled self-achievement. The four career values items about hygienic factor loaded strongly on Factor 2 (the average factor loading was 0.713). Thus, this factor can be labeled hygienic factor. The five career values items about prestige loaded strongly on Factor 3 (the average factor loading was 0.675). Thus, this factor can be labeled prestige factor.

In a word, because the factor analytic results suggested that these 15 items could be reduced to three factors, the subsequent analyses are confined to the three factors—self-achievement, hygienic factor and prestige factor.

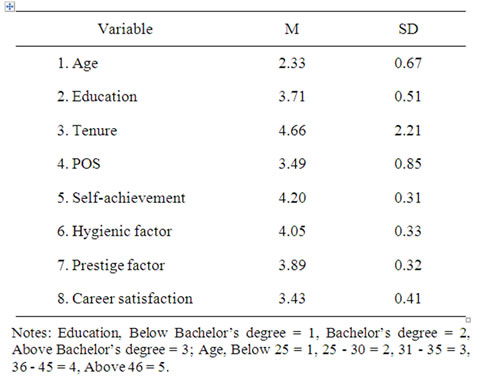

Means, standard deviations among the study variables are presented in the table 2.

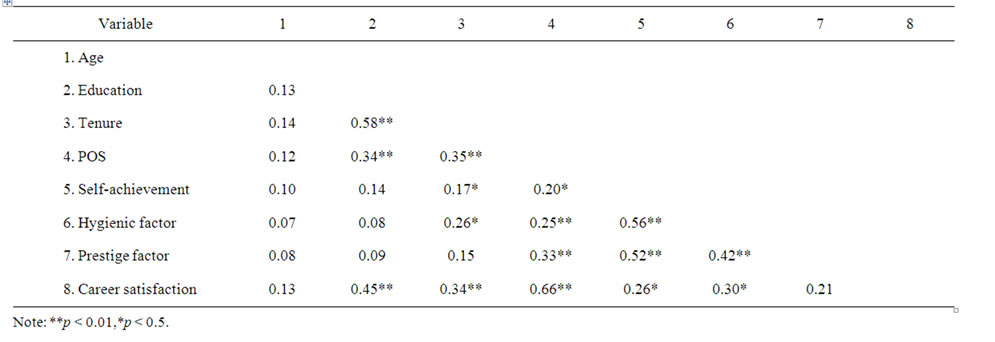

Spearsons correlations among the study variables are presented in the table 3. As could be expected, Table 3 shows that POS and career values (three factors) are sig

Table 2. Means, standard deviations of study variables (N = 151).

nificantly correlated to career success. We should note correlation between POS and career satisfaction is bigger then that between career values and career satisfaction.

6. Discussion

This study investigated the relationship of career values and POS with perceived career success for 151 knowledge employees in Hangzhou, the People’s Republic of China. As suggested by hypothesis one, career values have three dimensions, self-achievement, factor hygienic factor and prestige factor. As suggested by hypothesis three, knowledge employees whose perceive organizational support were more reported higher levels of career satisfaction. The results of the study also revealed that career values and perceived organizational support contributed separately and uniquely to career satisfaction.

In economy, market, technology, structure and society in general areas, Chinese organizations are facing big pressures to adjust to the new, evolving demands of their constituencies and to become more efficient and competitive within their environments. These new demands will more likely necessitate changes in managing and supporting their employees’ careers, which are their conceptions of the desirable regarding careers.

Career success is the positive psychological outcomes or achievements one has accumulated as a result of experiences over the span of working life. Therefore, employers should help their employees’ career to succeed. Of course, nowadays the models of careers are experiencing differently as compared to previous decades, knowledge employees and organizations should share responsibility in managing and controlling the process and the challenging nature of career success. There is widespread agreement among researchers and practitioners that career success is no longer solely determined by a set of well-defined variables, with careers are changing. However, in today’s contemporary work environment, most of employees are also likely to need organizational support in managing their careers. Consequently, employees who receive more organizational support are likely to enhance their opportunities for career advancement, which, in turn, have higher level organizational commitment, organizational citizenship behaviors, and so on. In a word, knowledge employees’ career success can eventually contribute to organizational performance, so, employers should take care of their career success to exchange their organizational commitments. Organizations should care antecedents of career success. Career success can be affected by the accumulated interaction between a variety of individual, organizational and societal norms, behaviors, and work practices. Studies of career success must consider motivation, human capital, personality, and dispositional factors.

According to leader-member theory, it can be seen that

Table 3. Coefficients & correlations of study variables (N = 151).

high quality individuals reap a great deal of individual as well as organizational benefits, including organizational support, and more preferential treatment, which is helpful to their job satisfaction and career success.

With challenges of today’s continually changing work environment, knowledge employees should take charge of their careers because recently a rapid shift in the locus of responsibility for career success has been seen. For example, Murphy, S. E., & Ensher, E. A. [42] found that individuals who used self-set career goals reported greater job satisfaction and perceived career success; those who engaged in positive cognitions also had higher job satisfaction; and those who used behavioral selfmanagement strategies reported greater perceived career success.

In this paper, we have investigated—from a multidisciplinary point of view—whether, and if so, to what extent career values are directly related to knowledge employees’ career success. Our analyses showed direct associations between career values and career satisfaction. Thus, knowledge employees should build right career values.

One of central thesis of this study is that knowledge employees’ career values, which is their conceptions of the desirable regarding career-are rooted in, and largely shaped by the work structures and social institutions in which individuals participate and are embedded. Career values affect the kinds of interests that motivate knowledge employees and the types of incentives and benefits that are available through their career activity.

Overall, our findings are to some extent in accordance with the findings of previous studies, but we have also found differing result. We found POS influenced career satisfaction more than career values for knowledge employees.

7. Conclusions

Knowledge employees not only should take responsibility for their own careers, but that they stand to benefit from so doing, even if their plans sometimes fail to be realized and their tactics do not always work. Changing career values is important for knowledge employees.

The most important contribution of this research is that knowledge of the antecedents to career success should provide certain advantages to organizations attempting to select and motivate employees. The study of career values, perceived organizational support and career success is particularly useful since those whose career is satisfied are more likely to remain with the organization, strive towards the organization’s mission, goals and objectives and devoted to their organization.

Organizations that seek to attract and retain the best possible employees can benefit from an understanding of what leads to their career success. An understanding of the process by which career success is created could therefore allow organizations to attract applicants whose higher levels of career values, in turn, to be satisfied and committed to their job and career.

At the same time, POS could also play a particularly important role under these circumstances.

An unanswered question in this research remains, why and how career values play a role in helping knowledge employees to obtain career success.

This study also contributes to career research. Ng et al.’s [11] meta-analysis summarized that currently there are four categories of predictors of career success: human capital, organizational sponsorship, socio-demographic status, and stable individual difference. Against the background of meager research on the career values antecedents of career satisfaction, this study makes a proactive attempt in exploring one important factor, career values and extends the line of research to career success.

The results indicated that employees who reported high levels of POS will report greater career success than employee who does not.

REFERENCES

- S. E. Seibert and M. L. Kraimer, “Proactive Personality Indirectly Relates to Career Progression and Satisfaction through Specific Proactive Behaviors and Cognitive Processes,” Personnel Psychology, Vol. 54, 2001, pp. 845- 874.

- U. E. Gattiker and L. Larwood, “Predictors for Career Achievement in the Corporate Hierarchy,” Human Relations, Vol. 43, 1990, pp. 703-726.

- T. A. Judge, D. M. Cable, J. W. Boudreau, and R. D. Bretz, “An Empirical Investigation of the Predictors of Executive Career Success,” Personnel Psychology, Vol. 48, No. 3, 1995, pp. 485-519. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.1995.tb01767.x

- M. Poole, J. Langanfox and M. Omodei, “Sex-Difference in Perceived Career Success,” Genetic Social and General Psychology Monographs, Vol. 117, No. 2, 1991, pp. 153-178.

- S. Aryee, Y. W. Chay and J. Chew, “An Investigation of the Predictors and Outcomes of Career Commitment in Three Career Stages,” Journal of Vocational Behavior, Vol. 44, No. 1, 1994, pp. 1-16. doi:10.1006/jvbe.1994.1001

- R. Ellis and H. G. Heneman, “Career Pattern Determinants of Career Success for Mature Managers,” Journal of Business and Psychology, Vol. 5, No. 1, 1990, pp. 2- 24. doi:10.1007/BF01013942

- T. A. Judge, C. A. Higgins, C. J. Thoresen and M. R. Barrick, “The Big Five Personality Traits, General Mental Ability, and Career Success across the Life Span,” Personnel Psychology, Vol. 52, No. 3, 1999, pp. 621-651.

- P. Tharenou, “Explanations of Managerial Career Advancement,” International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 12, No. 1, 1997, pp. 39-93.

- J. W. Boudreau, W. R. Boswell and T. A. Judge, “Effects of Personality on Executive Career Success in the United States and Europe,” Journal of Vocational Behavior, Vol. 58, No. 1, 2001, pp. 53-81. doi:10.1006/jvbe.2000.1755

- G, Jaskolka, J. M. Beyer and H. M. Ti-ice, “Measuring and Predicting Managerial Success,” Journal of Vocational Behavior, Vol. 26, No. 2, 1985, pp. 189-205.

- T. W. H. Ng, L. T. Eby, K. L. Sorensen and D. C. Feldman, “Predictors of Objective and Subjective Career Success: A Meta-Analysis,” Personnel Psychology, Vol. 58, No. 2, 2005, pp. 367-408. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2005.00515.x

- W. H. Thomas and C. F. Daniel, “Human Capital and Objective Indicators of Career Success: The Mediating Effects of Cognitive Ability and Conscientiousness,” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 83, No. 1, 2010, pp. 207-235. doi:10.1348/096317909X414584

- C. J. Mottaz, “An Analysis of the Relationship between Education and Organizational Commitment in a Variety of Occupational Groups,” Journal of Vocational Behavior, Vol. 28, No. 3, 1986, pp. 214-228. doi:10.1016/0001-8791(86)90054-0

- A. Kalleberg, “Work Values and Job Rewards: A Theory of Job Satisfaction,” American Sociological Review, Vol. 42, No. 1, 1977, pp. 124-143. doi:10.2307/2117735

- C. J. Berger and C. A. Olson, “Effects of Unions on Job Satisfaction: The Role of Work-Related Values and Perceived Rewards,” Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, Vol. 32, No. 3, 1983, pp. 289-324. doi:10.1016/0030-5073(83)90153-8

- K. P. Kuchinke, H. S. Kang and S. Y. Oh, “Examination of the Combined Effects of Work Values and Early Work Experiences on Organizational Commitment,” Asia Pacific Education Review, Vol. 94, 2008, pp. 552-564.

- C. E. Jurgensen, “Job Preferences (What Makes a Job Good or Bad?),” Journal of Psychological, Vol. 63, No. 3, 1978, pp. 267-276.

- Z. Shapira and T. L. Griffith, “Comparing the Work Values of Engineers with Managers, Production, and Clerical Workers: A Multivariate Analysis,” Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 11, No. 4, 1990, pp. 281-292. doi:10.1002/job.4030110404

- D. E. Super and C. Super, “The Psychology of Careers,” Harper, New York, 1957

- C. H. Robinson and N. E. Betzfactor, “A Psychometric Evaluation of Super’s Work Values Inventory-Revised,” Journal of Career Assessment, Vol. 16, No. 4, pp. 456- 473. doi:10.1177/1069072708318903

- J. M. Watson and P. F. Meiksins, “What do Engineers Want? Work Values, Job Rewards, and Job Satisfaction,” Science, Technology, & Human Values, Vol. 16, No. 2, 1991, pp. 140-172.

- J. Greenhaus, S. Parasuraman and W. Wormley, “Effects of Race on Organizational Experiences, Job Performance Evaluations, and Career Outcomes,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 33, No. 1, 1990, pp. 64-86.

- S. E. Seibert, J. M. Crant and M. L. Kraimer, “Proactive Personality and Career Success,” Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 84, 1999, pp. 416-427.

- W. A. Hochwarter, C. Kacmar, P. L. Perrewe and D. Johnson, “Perceived Organizational Support as a Mediator of the Relationship between Politics Perceptions and Work Outcomes,” Journal of Vocational Behavior, Vol. 63, No. 3, 2003, pp. 438-456.

- R. A. Guzzo, K. A. Noonan and E. Elron, “Expatriate Managers and the Psychological Contract,” Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 79, No. 4, 1994, pp. 617-626.

- Y. Y. Chen and W. Fang, “The Moderating Effect of Impression Management on the Organizational Politics Performance Relationship,” Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 79, No. 3, 2008, pp. 263-277.

- R. J. Riggle, D. R. Edmondson and J. D. Hansen, “A Meta-Analysis of the Relationship between Perceived Organizational Support and Job Outcomes: 20 Years of Research,” Journal of Business Research, Vol. 62, No. 10, 2009, pp. 1027-1030.

- C. Kwak, B. Y. Chung, Y. Xu and C. Eun-Jung, “Relationship of Job Satisfaction with Perceived Organizational Support and Quality of Care among South Korean Nurses: A Questionnaire Survey,” International Journal of Nursing Studies, Vol. 47, No. 10, 2010, pp. 1292-1298.

- J. B. De Coninck, “The Effect of Organizational Justice, Perceived Organizational Support, and Perceived Supervisor Support on Marketing Employees’ Level of Trust,” Journal of Business Research, Vol. 63, No. 12, 2010, pp. 1349-1355.

- L. Rhoades and R. Eisenberger, “Perceived Organizational Support: A Review of the Literature,” Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 87, No. 4, 2002, pp. 698-714.

- R. A. Noe, “Is Career Management Related to Employee Development and Performance?” Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 17, No. 2, 1996, pp. 119-133. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(199603)17:2<119::AID-JOB736>3.0.CO;2-O

- G. F. Dreher and R. A. Ash, “A Comparative Study of Mentoring among Men and Women in Managerial, Professional, and Technical Positions,” Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 75, No. 5, 1990, pp. 539-546. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.75.5.539

- C. Kirchmeyer, “Determinants of Managerial Career Success: Evidence and Explanation of Male/Female Differences,” Journal of Management, Vol. 24, No. 6, 1998, pp. 673-692.

- W. Whitely, T. Dougherty and G. Dreher, “Relationship of Career Mentoring and Socioeconomic Origin to Managers’ and Professionals’ Early Career Progress,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 34, No. 2, 1991, pp. 331-351.

- D. Turban, and T. Dougherty, “Role of protégé’s personality in receipt of mentoring and career success,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 37, No. 4, 1994, pp. 688-702.

- J. E. Wallace, “The Benefits of Mentoring for Female Lawyers,” Journal of Vocational Behavior, Vol. 58, No. 3, 2001, pp. 366-391. doi:10.1006/jvbe.2000.1766

- G. Nabi, “The Relationship between HRM, Social Support and Subjective Career Success among Men and Women,” International Journal of Manpower, Vol. 22, No. 5, 2001, pp. 457-474. doi:10.1108/EUM0000000005850

- B. R. Barnett and M. L. Bradley, “The Impact of Organizational Support for Career Development on Career Satisfaction,” Career Development International, Vol. 12, No. 7, 2007, pp. 617-636. doi:10.1108/13620430710834396

- B. J. Punnett, J. A. Duffy, S. Fox, A. Gregory, T. Lituchy, J. Miller, et al., “Career Success and Satisfaction: A Comparative Study in Nine Countries,” Women in Management Review, Vol. 22, No. 5, 2007, pp. 371-390. doi:10.1108/09649420710761446

- F. Noordin, T. Williams and C. Zimmer, “Career Commitment in Collectivist and Individualist Cultures: A Comparative Study,” International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 13, No. 1, 2002, pp. 35-54. doi:10.1080/09585190110092785

- J. Sturges, D. Guest, N. Conway and K. M. Davey, “A Longitudinal Study of the Relationship between Career Management and Organizational Commitment Among Graduates in the First Ten Years at Work,” Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 23, No. 6, 2002, pp. 731- 748. doi:10.1002/job.164

- S. E. Murphy and E. A. Ensher, “The Role of Mentoring Support and Self-Management Strategies on Reported Career Outcomes,” Journal of Career Development, Vol. 27, No. 4, 2001, pp. 229-246. doi:10.1023/A:1007866919494

NOTES

*Sponsorship: National Natural Science Foundation of China. (70972135).