Journal of Modern Physics

Vol.08 No.09(2017), Article ID:78845,26 pages

10.4236/jmp.2017.89096

Selection of Optimal Embedding Parameters Applied to Short and Noisy Time Series from Rössler System

Olivier Delage1, Alain Bourdier2

1Department of Physics, The University of La Reunion, Saint Denis, France

2Department of Physics and Astronomy, The University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, USA

Copyright © 2017 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: July 26, 2017; Accepted: August 28, 2017; Published: August 31, 2017

ABSTRACT

Throughout scientific research, the state space reconstruction that embeds a non-linear time series is the first and necessary step for characterizing and predicting the behavior of a complex system. This requires to choose appropriate values of time delay T and embedding dimension . Three methods are applied and discussed on nonlinear time series provided by the Rössler attractor equations set: Cao’s method, the C-C method developed by Kim et al. and the C-C-1 method developed by Cai et al. A way to fix a parameter necessary to implement the last method is given. Focus has been put on small size and/or noisy time series. The reconstruction quality is measured by using a criterion based on the transformation smoothness.

. Three methods are applied and discussed on nonlinear time series provided by the Rössler attractor equations set: Cao’s method, the C-C method developed by Kim et al. and the C-C-1 method developed by Cai et al. A way to fix a parameter necessary to implement the last method is given. Focus has been put on small size and/or noisy time series. The reconstruction quality is measured by using a criterion based on the transformation smoothness.

Keywords:

Phase Space Reconstruction, Embedding Window, Rössler System, Time Series, Correlation Integral, Delay Time

1. Introduction

In many fields of science and industry, complex systems are studied through temporal time series of scalar observations of a k dimensional dynamical system [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] . In most cases, the state space dimension and the system of equations that define the system evolution and behavior in the state space are unknown. Each value in a time series results from the interaction of the state variables in the state space. The main purpose of time series analysis is to learn about the dynamics behind some time ordered measurement data. To investigate an experimental kth order dynamical system from a scalar time series, it is necessary to reconstruct a state space by using time delay or time derivative coordinates. The reconstructed trajectory is expected to have the same characteristics than the trajectory embedded in the original phase space. It can be proved through Taken’s theorem that the unstable periodic orbits of a strange attractor could be recovered in an embedded state space whenever the time series is long enough with no noise [1] [2] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] . In that case, the embedding dimension  and the time delay T [1] [2] [3] [10] [11] are not correlated and can be selected independently [7] [8] [9] . In the real world, time series are not infinitely long and could be hardly noisy. In that case

and the time delay T [1] [2] [3] [10] [11] are not correlated and can be selected independently [7] [8] [9] . In the real world, time series are not infinitely long and could be hardly noisy. In that case  and T are correlated and an alternative approach used in the literature is to determine the time window length

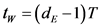

and T are correlated and an alternative approach used in the literature is to determine the time window length  which is the entire time spanned by the embedding vectors [7] [8] [9] . Once

which is the entire time spanned by the embedding vectors [7] [8] [9] . Once  is determined, the time delay T should be chosen so that the serial correlation of the

is determined, the time delay T should be chosen so that the serial correlation of the  time subseries should be minimum [7] [8] . As the essence of serial correlation is to see how sequential observations in a time series affect each other, Brock, Dechert and Scheinkman have developed a new statistic named “BDS statistic” able to test if a given data set is independently and identically distributed [12] [13] . The BDS statistic is based on the correlation integral and Brock has shown that the correlation integral behaves like the characteristic function of a time series through the fact that if the time series arises from several independent random variables, the correlation integral is the product of the correlation integrals of sub time series components. In that sense, the BDS statistic can be interpreted as the serial correlation of a nonlinear time series. State space reconstruction is necessary before developing forecasting methods and, as the quality of state space reconstruction affects significantly the accuracy in time series forecasting, the scope of this paper is threefold: i ) to review test and compare, in terms of quality, three methods used for selecting state space reconstruction parameters (time delay, embedding dimension) from a nonlinear time series provided by the Rössler attractor equations set; ii) to apply these methods to small size time series and test their robustness to noise with the objective to use them for experimental data; iii) to qualify these methods by defining a criterion able to measure the quality of the state space reconstruction.

time subseries should be minimum [7] [8] . As the essence of serial correlation is to see how sequential observations in a time series affect each other, Brock, Dechert and Scheinkman have developed a new statistic named “BDS statistic” able to test if a given data set is independently and identically distributed [12] [13] . The BDS statistic is based on the correlation integral and Brock has shown that the correlation integral behaves like the characteristic function of a time series through the fact that if the time series arises from several independent random variables, the correlation integral is the product of the correlation integrals of sub time series components. In that sense, the BDS statistic can be interpreted as the serial correlation of a nonlinear time series. State space reconstruction is necessary before developing forecasting methods and, as the quality of state space reconstruction affects significantly the accuracy in time series forecasting, the scope of this paper is threefold: i ) to review test and compare, in terms of quality, three methods used for selecting state space reconstruction parameters (time delay, embedding dimension) from a nonlinear time series provided by the Rössler attractor equations set; ii) to apply these methods to small size time series and test their robustness to noise with the objective to use them for experimental data; iii) to qualify these methods by defining a criterion able to measure the quality of the state space reconstruction.

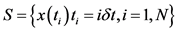

In this work, a pseudo experimental approach is considered. The equations describing the Rössler attractor are solved numerically. The numerical values obtained are assumed to be measurements. We start from a scalar time series  of N observations of the Rössler x variable with the

of N observations of the Rössler x variable with the  sampling rate that is the shortest time between two measurements. The method of delays is used to embed the time series S into a set of points of a

sampling rate that is the shortest time between two measurements. The method of delays is used to embed the time series S into a set of points of a  dimensional space

dimensional space  where T is the delay time given by

where T is the delay time given by ,

,  the embedding dimension and

the embedding dimension and  , the number of embedded points. The reconstructed state space must be topologically equivalent to the original one, the selection of optimal values for T and

, the number of embedded points. The reconstructed state space must be topologically equivalent to the original one, the selection of optimal values for T and  are very important and affect the quality of the reconstruction. Through the large number of publications dealing with this subject, there are two main approaches of selecting

are very important and affect the quality of the reconstruction. Through the large number of publications dealing with this subject, there are two main approaches of selecting  and T. The first approach consists in selecting

and T. The first approach consists in selecting  and T independently and is generally used in the case of sufficiently long noise free time series [7] [8] [9] [14] [15] . When time series are limited or contaminated by noise, the theorem of Takens is silent and the delay time T is observed to vary with the embedding dimension

and T independently and is generally used in the case of sufficiently long noise free time series [7] [8] [9] [14] [15] . When time series are limited or contaminated by noise, the theorem of Takens is silent and the delay time T is observed to vary with the embedding dimension . In this case, as an irrelevant partnership between T and

. In this case, as an irrelevant partnership between T and  could affect the equivalence between the reconstructed space and the original one, another approach, based on the delay time window,

could affect the equivalence between the reconstructed space and the original one, another approach, based on the delay time window,

This article is structured around three sections, this work, can be considered as the preliminary step to the time series forecasting methods development, the first section is devoted to the calculation of the maximum Lyapunov exponent and the Lyapunov dimension from time series obtained by integrating numerically the Rössler differential equations set. The second section is focused on the state space reconstruction parameters selection. The main idea is to subdivide the original time series S into p sub-series, each of them representing an embedded point in a

Three methods able to select the embedding dimension

This paper also constitutes a sort of set-up in order to become familiar with these different techniques before applying them to real experimental data.

2. Calculation of Lyapunov Exponents and Lyapunov Dimension for the Rössler Attractor

The dynamical system of interest in this first part consists of the following three coupled differential equations [4] [20] [21] [22]

where a, b and c have constant values. These equations have a chaotic attractor which is displayed in Figure 1 which was obtained from a simple numerical integrator.

The Rössler attractor is largely a product of the interaction between an attracting direction and a repelling one. The calculated trajectory starts close to a fixed point, the linear terms of the two first equations create oscillations in the variables x and y. These oscillations are amplified, which results into a spiraling-out motion. The motion in x and y is then coupled to the z variable ruled by the third equation, which contains the nonlinear term and which induces the reinjection back to the beginning of the spiraling-out motion. A very complex

Figure 1. Rössler attractor representation from the equations set. a = 0.2, b = 0.4 and c = 5.7.

dynamic arises.

When chaos takes place, one can observe a great sensitivity of the motion to small changes in initial conditions. Two closely neighboring trajectories diverge exponentially. Their rate of divergence is constant, and a plateau is obtained when determining the Lyapunov exponent numerically. When a = 0.2 and b = 0.4, chaos appears when c has a sufficiently high value. This is shown by calculating maximum Lyapunov exponents using Benettin’s method [3] [20] [21] [23] [24] for different trajectories considering different values of parameter c.

Figure 2 shows that chaos takes place when c is between 5 and 5.2.

Then, considering a = 0.2, b = 0.4 and c = 5.7, a positive maximum Lyapunov exponent for this trajectory is calculated by using Benettin’s method. Two trajectories with two very close initial conditions were considered and they were renormalized for every fixed time interval Δτ. The following value was found:

The transition from simple to strange attractor proceeds via a sequence of period-doubling bifurcations [20] .

Then, considering the parameters defining the Rossler attractor shown in Figure 1 (a = 0.2, b = 0.4 and c = 5.7), the Lyapunov exponents spectrum is calculated. The algorithm employed was proposed Wolf et al. [25] . The numerical results are shown in Figure 3.

The values of the three Lyapunov exponents are

as expected

The number of non-negative Lyapunov exponents, d = 2, allows us to identify the dimension of the attractor [26] . We are going to show that its fractal dimension is a little bit greater.

The Lyapunov dimension

where j is defined by the conditions

Figure 2. Influence of the c parameter on the maximum Lyapunov exponents for the trajectory. (a): c = 5.2,

Figure 3. (a) Lyapunov spectrum for the trajectory shown in Figure 1; (b) magnification of (a).

which means that the attractor is close to a plane surface. The fractal dimension gives a lower bound on the number of variables needed to model the dynamics of the attractor.

3. Time Delay Reconstruction of the State Space by Sampling a Coordinate of the Rössler Attractor

3.1. Formulation of the Problem

Let us move to a pseudo experimental approach. It is assumed that we only have a single sequence of measurements obtained at different times. We seek a hidden determinism in our experimental data. Here, the “experimental results” are given by a numerical integration of Equation (1). In this section, we just try the reconstruction method provided by the tool box CDA22 [1] .

It is assumed that only the x-components of the

where

Packard et al. [4] [6] have shown that starting from the time series (5), one may reconstruct the trajectory of the attractor in a

with

3.2. Considerations on the Minimum Embedding Dimension

The space reconstruction requires to select values of the reconstructed space dimension and the time delay. The embedding theorem [6] [9] [10] [28] tells us that the following sufficient but not necessary condition must be verified

where

that is

To verify the relevance of this condition, the reconstruction was achieved considering several values of

Figure 4 shows the curves

Figure 4. The correlation dimension versus the embedding dimension. The full line was obtained for

tained with

Figure 4 also shows that the results obtained for

It is known that

3.3. Cao’s Method for Determining the Embedding Dimension

The optimal embedding dimension has also been calculated by using Cao’s algorithm which is much less time-consuming [9] [14] . According to the IIIa paragraph notations and (7), Cao defines

where

and

with T =

where the meaning of

Figure 5 shows that

Figure 5.

Then, Cao’s algorithm has been applied on a much smaller data sequence of about 4000 values,

Cao’s method has been applied then to the 4000 values data-sequence with noise added. Figure 6 show results obtained when a white Gaussian noise with variance one is added to the 4000 values data-sequence.

In Figure 6, when n = 50 and n = 10,

Then, a white Gaussian noise with variance five was added. Figure 7 show that a high value of n is necessary to determine a minimum embedding dimension. The following values for

In this case

In summary, it was shown that for noise-free data of very long length, the reconstruction is valid for any time delay as far as the embedding dimension is high enough. When going to small number noisy data samples, the time delay used to determine the minimum embedding dimension cannot have any value.

Figure 6.

Figure 7.

3.4. Simultaneous Determination of the Embedding Dimension and Time Delay by Using the C-C Method

The Cao’s method [14] , used to determine the optimal embedding dimension

where

r is a search radius and H is the Heaviside function: H(a) = 0 if a < 0 and H(a)=1 if a ³0. N is still the size of the data set, n is the index lag,

The average of the statistical quantity given by Equation (14) is defined as

when

The locally optimal times may be either the zero crossing of

which measures the variations of

For data set with finite sample sizes N, appropriate choices for

and

As locally optimal times are either zero crossing of

which gives the delay time window

The first local minimum of

The minimum of

White Gaussian noises with different variances σ (σ = 1, σ = 5, σ = 10) has been added to the noise free original signal of 4000 data sequence and the C-C method has been applied to the time series

Figure 8. Graphic representations of

Figure 9.

Table 1. T and

noise free original signal,

The parameter α is linked to the signal to noise ratio SNR which can be defined as

then, the C-C method should be stable against the noise for values of α such as

In Table 1, we observe that for σ = 1, the C-C method is stable against the noise when

In summary, the C-C method is a relatively simple method easy to implement that can be used for relatively small data set to determine both the time delay T and the time delay window

3.5. An Optimization of the C-C Method

In their paper, W.D Cai et al. [8] pointed out some problems that limit to the C-C method. The first one is that there are local minimal points whose values are very close to the minimum of

Starting from the N values initial data set and according to (7), the number of the embedded points calculated from the delay time T in the

as each component

Kim et al. have shown in their paper [7] that, when using the BDS statistic on time series, the sample data size N should be appropriate relatively to the values of

The average of the statistical quantity given by Equation (14) is defined as follows:

The definitions of

If we define the mean orbital period P of a chaotic system as the mean period generated by the oscillations of the chaotic attractor in the phase space orbits, an optimal value for

Therefore, a new quantity

By looking for the minimum of

The C-C-1 method has been programmed in R language by using the same packages as with the C-C method. An organigram of the C-C-1 method is presented in Appendix 2 and results obtained the 4000-values data sequence with q = 19 are shown in Figure 10.

High frequencies oscillations occurring when applying the C-C method (red dashed line) have disappeared in the C-C-1 method (black solid line) (see Figure 10). In Figure 10, the

Figure 10.

Figure 11.

was n = 12 for the C-C method. n = 10 represents the optimal delay time T.

Figure 10 shows that the estimate of the optimal delay time T in the C-C-1 method (n = 10) is quite the same as with the C-C method (n = 12). The first local minimum of

An optimization of the C-C-1 method should be to define a criterion for the optimal selection of the q parameter value. Based on the results obtained from the C-C method, a criterion is suggested here to select optimally the q parameter value. We define first the quantity

where

timal choice of the q parameter value should coincide with the first value of n at which

Figure 12 shows the evolution of Q(n) as a function of n.

As the value of the q parameter should be chosen so that the time subseries

Figure 12. Graphic representation of Q as a function of n.

Table 2. T and

n is presented in Appendix 3.

The C-C-1 method has been applied to the time series

We observe that the C-C-1 method gives stable results for σ = 1, for σ = 5 since

In conclusion, the C-C-1 method is an improvement of the C-C method. The original time series is subdivided by setting a parameter q which is independent of the time delay T. Tests performed on this method show that it gives more reliable and stable estimates of the optimal delay time T and the optimal time delay window

4. Reconstruction Qualification

How can we measure the quality of a reconstruction? Time-delay embedding provides a diffeomorphic representation of the original state space. This means that the mapping between the original and the reconstructed state space is a smooth one. As the optimality of the reconstruction is based on minimizing the distortion of the original attractor when applying the reconstruction map [30] , an appropriate measure of the quality of a reconstruction would be to measure the smoothness of the transformation between the original and the reconstructed space [18] . Once such a transformation is achieved, a good evaluation of invariants such as the Lyapunov exponent and the fractal dimensions of the attractors is required.

In the case of a large size of noise-free data (about 32,000 values), Takens time-delay embedding ensures a topological equivalence between the original and reconstructed space and a way to assess this equivalence is to check whether the fractal dimensions of the attractors are preserved [9] [18] [31] . The maximum Lyapunov exponent was calculated using the CDA22 tool box, we found

Moreover, considering for

In the case of lower size of noise free data (about 4000 values), Takens time delay embedding does not ensure the optimality of the reconstruction and requires to measure the smoothness of the mapping with the embedding parameters values determined by using the C-C-1 method (

Let be

with

5. Conclusions

This paper provides an overview of methods for embedding parameters optimal selection applied to the Rössler strange attractor reconstruction through chaotic time series. Two main approaches are used whether times series are sufficiently long free noise data set [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] or finite and noisy data set [7] [8] [33] . In the first case the embedding parameters

The C-C method developed by Kim et al. [7] has been applied to finite data sequence of about 4000 values and the robustness of this method has been stu- died when the original data set is degraded white Gaussian noise with different

Figure 13. Similarity between the initial state space (a) and the reconstructed one (b).

variance σ and different strength α. Results are summarized in Table 1 and discussed. The C-C-1 method suggested by Cai et al. [8] improve some drawbacks of the C-C method and has been tested on the same time series of about 4000 values and show

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Electronic, Energetic and Process Laboratory of the Reunion Island University for having us as research fellows and thank Pr Chabriat its director for having offered their facilities. We also wish to thank Professor J.C. Diels of the University of New Mexico for valuable discussions.

Cite this paper

Delage, O. and Bourdier, A. (2017) Selection of Optimal Embedding Parameters Applied to Short and Noisy Time Series from Rössler System. Journal of Modern Physics, 8, 1607-1632. https://doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2017.89096

References

- 1. Sprott, J.C. (2003) Chaos and Time-Series Analysis. Oxford University Press.

- 2. Nayfey, A.H. and Balachandran, B. (1995) Applied Nonlinear Dynamics. Wiley Series in Nonlinear Science. https://doi.org/10.1002/9783527617548

- 3. Ott, E. (1993) Chaos in Dynamical Systems. University Press, Cambridge.

- 4. Packard, N.H., Crutchfield, J.P., Farmer, J.D. and Shaw, R.S. (1980) Physical Review Letters, 45, 712-716. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.45.712

- 5. Eckmann, J.P. and Ruelle, D. (1985) Reviews of Modern Physics, 57, 617-656. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.57.617

- 6. Takens, F. (1981) Dynamical Systems and Turbulence. In: Rand, D. and Young, L.S., Eds., Lecture Notes in Mathematics, Vol. 898, 366-381, Springer-Verlag, New York.

- 7. Kim, H.S., Eykholt, R. and Salas, J.D. (1999) Physica D, 127, 48-60.

- 8. Cai, W.D., Qin, Y.Q. and Yang, B.R. (2008) Kubernetika, 44, 557-570.

- 9. Krakovska, A., Mezeiova, K. and Budacova, H. (2015) Journal of Complex Systems, 2015, Article ID: 932750.

- 10. Abarbanel, H.D.I. and Kennel, M.B. (1993) Physical Review E, 47, 3057-3068. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.47.3057

- 11. Kennel, M.B., Brown, R. and Abarbanel, H.D.I. (1992) Physical Review A, 45, 3403-3411. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.45.3403

- 12. Brock, W.A., Hsieh, D.A. and LeBaron, B. (1991) Nonlinear Dynamics, Chaos, and Instability: Statistical Theory and Economic Evidence. MIT Press, Cambridge, London.

- 13. Brock, W.A., Dechert, W.D., Scheinkman, J.A. and LeBaron, B. (1996) European Economic Review, 15, 197-235. https://doi.org/10.1080/07474939608800353

- 14. Cao, L. (1997) Pysica D, 110, 43-50.

- 15. Abarbanel, H.D.I., Brown, R., Sidorowich, J.J. and Tsimring, L.S. (1993) Reviews of Modern Physics, 65, 1331-1392.

- 16. Rosenstein, M.T., Collins, J.J. and De Luca, C.J. (1994) Physica D, 73, 82-98.

- 17. Martinerie, J.M., Albano, A.M., Mees, A.I. and Rapp, P.E. (1992) Physical Review A, 45, 7058-7064. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.45.7058

- 18. Nichkawde, C. (2013) Physical Review E, 87, Article ID: 022905. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.87.022905

- 19. Pecora, L.M., Caroll, T.L. and Heagy, J.F. (1995) Physical Review E, 52, 3420-3439. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.52.3420

- 20. Lichtenberg, A.J. and Liebermann, M.A. (1983) Regular and Stochastic Motion. Springer-Verlag, New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-4257-2

- 21. Tabor, M. (1989) Chaos and Integrability in Nonlinear Dynamics. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

- 22. Rössler, O.E. (1976) Physics Letters A, 57, 397-398.

- 23. Benettin, G., Galgani, L. and Strelcyn, J.M. (1976) Physical Review A, 14, 2338-2345. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.14.2338

- 24. Bourdier, A. and Michel-Lours, L. (1994) Physical Review E, 49, 3353-3359. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.49.3353

- 25. Wolf, A., Swift, J.B., Swinney, H.L. and Vastano, J.A. (1985) Pysica D, 16, 285-317.

- 26. Froehling, H., Crutchfield, J.P., Farmer, D., Packard, N.H. and Shaw, R. (1981) Physica D, 3, 605-617.

- 27. Farmer, J.D., Ott, E. and Yorke, J.A. (1983) Physica D, 7, 153-180. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-21830-4_11

- 28. Sauer, T., Yorke, J.A. and Casdagli, M. (1991) Journal of Statistical Physics, 65, 579-616. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01053745

- 29. Grassberger, P. and Procaccia, I. (1983) Pysica D, 9, 189-208.

- 30. Uzal, L.C., Grinblat, G.L. and Verdes, P.F. (2011) Physical Review E, 84, Article ID: 016223. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.84.016223

- 31. Mangiarotti, S. (2014) Modélisation Globale et caractérisation Topologique de Dynamiques Environnementales, Mémoire d’Habilitation à Diriger des Recherches en Physique. présenté à l’Université de Toulouse, 3.

- 32. Letellier, C., Moroz, I.M. and Gilmore, R. (2008) Physical Review E, 78, Article ID: 026203. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.78.026203

- 33. Casdagli, M., Eubank, S., Farmer, J.D. and Gibson, J. (1991) Pysica D, 51, 52-98.

Appendix 1

The C-C method organigram

Appendix 2

The C-C-1 method organigram

Appendix 3

Organigram for obtaining Q[n]

Appendix 4

Smoothness mapping F factor calculation R script

Input data: Initial time series S: ts4xnew, T (time delay) = 10, m (embedding dimension) = 5

Output data:F: F factor

library(stats)

library(scatterplot3d)

library(nonlinearTseries)

library(tseriesChaos)

X0=2.4099243

X1=2.2247949

Y0=4.0068145

Y1=4.0693054

a=0.2

b=0.4

c=5.7

deltat=(Y1-Y0)/(X0+(a*Y0))

Z0=Y0+((X1-X0)/deltat)

rosor=rossler(a=0.2,b=0.4,w=5.7,start=c(X0,Y0,Z0),time=seq(1,79.82,by=deltat))

N=length(rosor$x)

m=5

T=10

NP=N-((m-1)*T)

rosrec2=buildTakens(ts4xnew,m,T)

MATOR<-matrix(data=0.0,nrow=NP,ncol=3)

Vecsum<-vector(mode="numeric",length = NP)

for(irow in 1:NP){

MATOR[irow,1]=rosor$x[irow]

MATOR[irow,2]=rosor$y[irow]

MATOR[irow,3]=rosor$z[irow]

}

for(i in 1:NP){

XI=c(MATOR[i,1],MATOR[i,2],MATOR[i,3])

YI=c(rosrec2[i,1],rosrec2[i,2],rosrec2[i,3],rosrec2[i,4],rosrec2[i,5])

nno=neighbourSearch(MATOR,i,0.7)

nnr=neighbourSearch(rosrec2,i,0.7)

VO<-nno[[2]]

VR=nnr[[2]]

Vinto=intersect(VO,VR)

INNO=Vinto[1]

XINNO= c(MATOR[INNO,1],MATOR[INNO,2],MATOR[INNO,3])

YINNO= c(rosrec2[INNO,1],rosrec2[INNO,2],rosrec2[INNO,3],rosrec2[INNO,4],rosrec2[INNO,5])

vecxinno=XI-XINNO

deno=max(vecxinno)

vecyinno=YI-YINNO

numo=max(vecyinno)

var1=numo/deno

Vintr=intersect(VR,VO)

INNR=Vintr[1]

XINNR= c(MATOR[INNR,1],MATOR[INNR,2],MATOR[INNR,3])

YINNR=c(rosrec2[INNR,1],rosrec2[INNR,2],rosrec2[INNR,3],rosrec2[INNR,4],rosrec2[INNR,5])

vecyinnr=YI-YINNR

vecxinnr=XI-XINNR

denr=max(vecyinnr)

numr=max(vecxinnr)

var2=numr/denr

var=abs(var1*var2)

Vecsum[i]=var

}

result=sum(Vecsum)/NP