Journal of Modern Physics

Vol.07 No.06(2016), Article ID:65024,9 pages

10.4236/jmp.2016.76052

Alignment of Quasar Polarizations on Large Scales Explained by Warped Cosmic Strings

Reinoud Jan Slagter1,2

1Asfyon, Astronomisch Fysisch Onderzoek Nederland, Bussum, The Netherlands

2Department of Physics, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 21 February 2016; accepted 22 March 2016; published 25 March 2016

ABSTRACT

The recently discovered alignment of quasar polarizations on very large scales could possibly be explained by considering cosmic strings on a warped five dimensional spacetime. Compact objects, such as cosmic strings, could have tremendous mass in the bulk, while their warped manifestations in the brane can be consistent with general relativity in 4D. The self-gravitating cosmic string induces gravitational wavelike disturbances which could have effects felt on the brane, i.e., the massive effective 4D modes (Kaluza-Klein modes) of the perturbative 5D graviton. This effect is amplified by the time dependent part of the warp factor. Due to this warp factor, disturbances don’t fade away during the expansion of the universe. From a nonlinear perturbation analysis it is found that the effective Einstein 4D equations on an axially symmetric spacetime, contain a “back- reaction” term on the righthand side caused by the projected 5D Weyl tensor and can act as a dark energy term. The propagation equations to first order for the metric components and scalar-gauge fields contain j-dependent terms, so the approximate wave solutions are no longer axially symmetric. The disturbances, amplified by the warp factor, can possess extremal values for fixed polar angles. This could explain the two preferred polarization vectors mod .

.

Keywords:

Quasar Polarization, Cosmic Strings, Warped Brane World Models, U(1) Scalar-Gauge Field, Multiple-Scale Analysis

1. Introduction

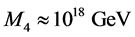

Physicists speculate that extra spatial dimensions could exist in addition to our ordinary 4-dimensional spacetime. The underlying theory is the string theory, an unified description of gauge interactions and gravity. String theory could provide an adequate description of quantum gravity and can be used to explain the several shortcomings of the Standard Model and modern cosmology, i.e., the unknown origin of dark energy and dark matter, the weakness of gravity ( hierarchy problem) and the incredibly fine-tuning of the cosmological constant. Moreover, the recently found evidence for the acceleration of our universe could be explained in these so-called super-string models without the need for a cosmological constant (self-acceleration). However, its weak point is, that it is extremely hard to make predictions which are testable at energies available in experiments because the theory will manifest itself at energies of the order of the fundamental Planck scale , dependent of the number of the extra dimensions. The observed 4-dimensional Planck scale is given by Newton’s constant and is

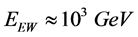

, dependent of the number of the extra dimensions. The observed 4-dimensional Planck scale is given by Newton’s constant and is . String theory also predicts the existence of sub-manifolds of the “bulk” spacetime, the so-called branes: it may be that our (3 + 1)-dimensional spacetime is such a 3-brane. All standard model fields resides on the brane, while gravity can propagate into the bulk. The fundamental scale in elementary particle physics, the electroweak scale, is of order

. String theory also predicts the existence of sub-manifolds of the “bulk” spacetime, the so-called branes: it may be that our (3 + 1)-dimensional spacetime is such a 3-brane. All standard model fields resides on the brane, while gravity can propagate into the bulk. The fundamental scale in elementary particle physics, the electroweak scale, is of order . In order to lower down the fundamental scale of super string theory to the electroweak scale, one conjectures that the 4-dimensional Planck scale is not fundamental, but only an effective scale which can become much larger than the

. In order to lower down the fundamental scale of super string theory to the electroweak scale, one conjectures that the 4-dimensional Planck scale is not fundamental, but only an effective scale which can become much larger than the  if the extra dimensions L

if the extra dimensions L

are much larger than  [1] . For

[1] . For , the fundamental Planck scale can be of the order of the

, the fundamental Planck scale can be of the order of the

electroweak scale. Within this brane world picture, at low energies, gravity is localized at the brane and general relativity is recovered, but at high energy gravity “leaks” into the bulk. Recently there is growing interest in the warped brane world model [2] , where there is one preferred extra dimension, with other extra dimensions treated as ignorable. The extra dimension is curved (or warped) rather than flat. This means that self-gravity of the brane is incorporated.

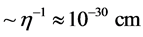

It is conjectured that one needs an inflaton field in the very early stages of our universe to solve the problems in the standard model of cosmology, i.e., the horizon and flatness problem. The inflationary cold dark matter model with a cosmological constant (LCDM) could be a good candidate if one abandons the cosmological constant problems. It can explain the fluctuations we observe in the cosmic microwave background (CMB). The inflaton field could be the well-known scalar-Higgs field. This field has lived up to its reputation. It originates from the theory of type II superconductivity, where vortex lines occur as topological defects in an abelian U(1) gauge model, which is coupled to a charged scalar field. It explains the famous Meissner effect (Ginzburg- Landau theory). Topological defects can occur when the field symmetries are broken. In cosmology, this happens when the universe cools down [3] . Topological defects, such as cosmic strings, monopoles and textures, can have cosmological implications. Apart from their possible astrophysical roles, topological defects are fascinating objects in their own right and can give rise to a rich variety of unusual phenomena. The U(1) vortex solution possesses mass, so it will couple to gravity. It came as a big surprise that there exists vortex-like solutions in general relativity. It is conjectured that any field theory which admits cosmic string solutions, a network of strings inevitable forms at some point during the early universe. However, it is doubtful if they will persist to the present time in the LCMD model. Evidence of these objects would give us information at very high energies in the early stages of the universe. It is believed that the grand unification (GUT) energy scale of symmetry breaking  is about

is about . The thickness of a cosmic string is

. The thickness of a cosmic string is  and the length could be unbounded long. The mass per unit length of a cosmic sting will be of the order of 1018 kg per cm, which is proportional to the square of the energy breaking scale. The thickness is still a point of discussion. By treating the cosmic string as an infinite thin mass distribution, one will encounter serious problems in general relativity. This infinite thin string model give rise to the “scaling solution”, i.e., a scale-invariant spectrum of density fluctuations, which in turn leads to a scale invariant distribution of galaxies and clusters. It was believed that cosmic strings could have served as seeds for the formation of galaxies. Cosmic strings can collide with each other and will intercommute to form loops. These loops will oscillate and loose energy via gravitational radiation and decay. There are already tight constraints on the gravitational wave signatures due to string loops via observations of the millisecond pulsar-timing data, the cosmic background radiation (CMB) by LISA and analysis of data of the LIGO-Virgo gravitational-wave detector. Its spectrum will depend on the string mass

and the length could be unbounded long. The mass per unit length of a cosmic sting will be of the order of 1018 kg per cm, which is proportional to the square of the energy breaking scale. The thickness is still a point of discussion. By treating the cosmic string as an infinite thin mass distribution, one will encounter serious problems in general relativity. This infinite thin string model give rise to the “scaling solution”, i.e., a scale-invariant spectrum of density fluctuations, which in turn leads to a scale invariant distribution of galaxies and clusters. It was believed that cosmic strings could have served as seeds for the formation of galaxies. Cosmic strings can collide with each other and will intercommute to form loops. These loops will oscillate and loose energy via gravitational radiation and decay. There are already tight constraints on the gravitational wave signatures due to string loops via observations of the millisecond pulsar-timing data, the cosmic background radiation (CMB) by LISA and analysis of data of the LIGO-Virgo gravitational-wave detector. Its spectrum will depend on the string mass , where

, where  is the mass per unit length. Recent observations from the COBE, Wamp and Planck satellites put the value of

is the mass per unit length. Recent observations from the COBE, Wamp and Planck satellites put the value of . It turns out that cosmic strings can not provide a satisfactory explanation for the magnitude of the initial density perturbations from which galaxies and clusters grew. The interest in cosmic strings faded away, mainly because of the inconsistencies with the power spectrum of the CMB. Moreover, they will produce a very special pattern of lensing effect, not found yet by observations. New interest in cosmic strings arises when it was realized that cosmic strings could be produced within the framework of string theory inspired cosmological models. Investigations on cosmic strings in warped brane world models show consistency with the observational bounds [4] [5] . The warp factor makes these strings consistent with the predicted mass per unit length on the brane, while brane fluctuations can be formed dynamically due to the modified energy- momentum tensor components of the scalar-gauge field. This effect is triggered by the time-dependent warp factor. The recently discovered “spooky” alignment of quasar polarization over a very large scale [6] could be well understood by the features of the cosmic strings in brane world models and could be the first evidence of the existence of these strings.

. It turns out that cosmic strings can not provide a satisfactory explanation for the magnitude of the initial density perturbations from which galaxies and clusters grew. The interest in cosmic strings faded away, mainly because of the inconsistencies with the power spectrum of the CMB. Moreover, they will produce a very special pattern of lensing effect, not found yet by observations. New interest in cosmic strings arises when it was realized that cosmic strings could be produced within the framework of string theory inspired cosmological models. Investigations on cosmic strings in warped brane world models show consistency with the observational bounds [4] [5] . The warp factor makes these strings consistent with the predicted mass per unit length on the brane, while brane fluctuations can be formed dynamically due to the modified energy- momentum tensor components of the scalar-gauge field. This effect is triggered by the time-dependent warp factor. The recently discovered “spooky” alignment of quasar polarization over a very large scale [6] could be well understood by the features of the cosmic strings in brane world models and could be the first evidence of the existence of these strings.

In Section 2 we will outline the warped 5-dimensional model. In Section 3 we apply the multiple-scale approximation in order to find an wavelike solution to first order of the Einstein and matter field equations.

2. The Warped 5D Model

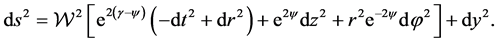

Let us consider the warped five-dimensional Friedmann-Lematre-Robertson-Walker (FLRW) model in cylin- drical polar coordinates

(1)

(1)

The function  is the warp factor and y the extra (bulk) dimension. Here

is the warp factor and y the extra (bulk) dimension. Here

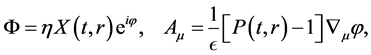

fields reside on the brane, while gravity can propagate into the bulk. We consider a scalar-gauge field on the brane in the form [7]

with

with

with

and

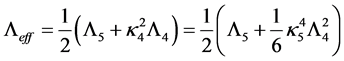

relation between the 4- and 5-dimensional Planck mass in the braneworld approach,

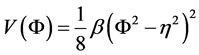

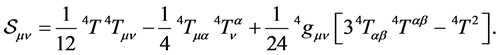

Equation (4) is the quadratic term in the energy-momentum tensor arising from the extrinsic curvature terms in the projected Einstein tensor

The second correction term

and is a part of the 5D Weyl tensor and carries information of the gravitational field outside the brane and is constrained by the motion of the matter on the brane, i.e., the Codazzi equation. The scalar-gauge field equation becomes [7]

with

From Equation (4) together with the matter field equations Equation (7), one obtains a set of partial differential equations, which can be solved numerically [5] . Because gravity can propagate in the bulk, the cosmic string can build up a huge mass per unit length (or angle deficit)

Besides the numerical solutions of the field equations, one should like to find an approximate wave solution where one can recognize the nonlinear features. In order to keep track of of the different orders of approximation, we will apply a multiple-scale analysis in the next section.

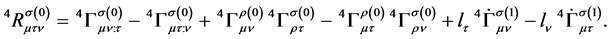

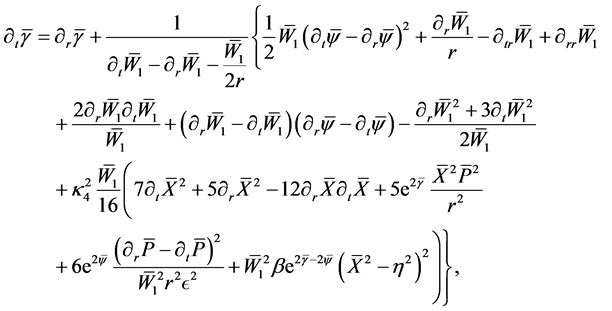

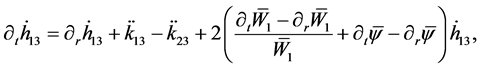

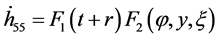

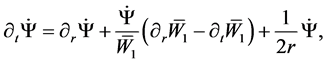

3. Nonlinear Wave Approximation

A linear approximation of wavelike solutions of the Einstein equations is not adequate in the case of high energy or strong curvature. There is a powerful approximation method to study nonlinear gravitational waves without any averaging scheme. The method is called a “two-timing” or “multiple-scale” method, because one considers

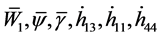

the relevant fields

Here

teristic dimension of the background. On warped spacetimes it could also be the ratio of the extra dimension y to the background dimension or even both. One is interested in an approximate solution of the metric and matter fields. If one substitute the series Equation (8) into the field equations, one obtains a formal series where now n runs from

order n of the field equations if

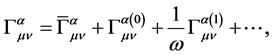

non-uniformity in a regular perturbation expansion, i.e., the appearance of secular terms. In general relativity, this will occur when high-frequency gravitational waves interact with the background metric or the curvature is strong due to the presence of compact objects. On our 5D spacetime, we expand

with

time being, only rapid variation in the direction of

with

with

where the colon represents the covariant derivative with respect to the

subsequently put equal zero the various powers of

for the fields

and the

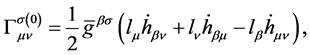

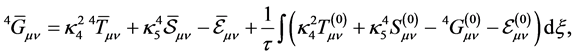

The contribution from the bulk space,

If we consider

which in other contexts is used as gauge conditions. It turns out that the contribution from the

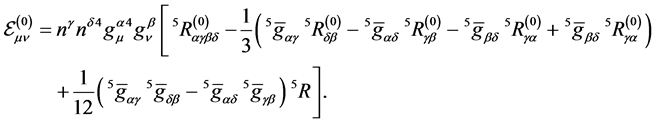

One also needs the Ricci tensor

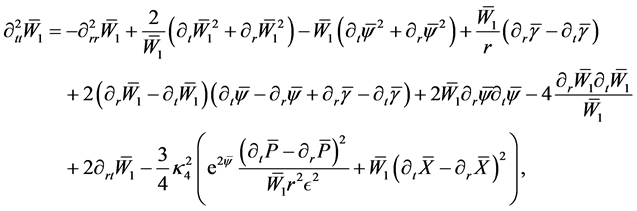

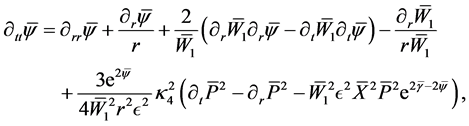

From the Einstein equations Equation (16), one can deduce a set of partial differential equations (PDE’s) when one imposes additional gauge conditions. As a simplified model, we take

where we took

to the

We notice that in our simplified case of radiative coordinates

It is manifest that to zero order there is an interaction between the high-frequency perturbations from the bulk, the matter fields on the brane and the evolution of

results in a solution

The equation for

For these matter field equations one needs the condition

This means that the

This angle-dependency could be an explanation of the recently found spooky alignment of the rotation axes of quasars over large distances in two perpendicular directions.

The next step is to investigate the higher order equations in

4. Conclusion

A nonlinear approximation of the field equations of the coupled Einstein-scalar-gauge field equations on a warped 5D spacetime is investigated. To zeroth order in the expansion parameter it is found that the evolution of the perturbations on the brane is triggered by the electric part of the 5D Weyl tensor and carries information of the gravitational field outside the brane. The warp factor in the nominator in front of the bulk contributions will cause a huge disturbance on the brane and could act as dark energy. It turns out that the first order disturbances are no longer axially symmetric. This means that wavelike disturbances in the energy-momentum tensor com- ponents can have preferred

Cite this paper

Reinoud JanSlagter,11, (2016) Alignment of Quasar Polarizations on Large Scales Explained by Warped Cosmic Strings. Journal of Modern Physics,07,501-509. doi: 10.4236/jmp.2016.76052

References

- 1. Arkani-Hamed, N., Dimopoulos, S. and Dvali, D. (1998) Physical Review Letters, B429, 263.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0370-2693(98)00466-3 - 2. Randall, L. and Sundrum, R. (1999) Physical Review Letters, 83, 3370.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.83.3370 - 3. Vilenkin, A. and Shellard, E.P.S. (1994) Cosmic Strings and Other Topological Defects. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- 4. Slagter, R.J. (2014) International Journal of Modern Physics D, 23, Article ID: 1450066.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1142/S0218271814500667 - 5. Slagter, R.J. and Pan, S. (2015) A New Fate of a Warped 5D FLRW Model with a U(1) Scalar Gauge Field. Found. of Phys., accepted and to appear.

http://120.52.73.77/arxiv.org/pdf/1501.02843.pdf - 6. Hutsemekers, D., Braibant, L., Pelgrims, V. and Sluse, D. (2014) Astronomy & Astrophysics, 572, A18.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201424631 - 7. Garfinkle, D. (1985) Physical Review D, 32, 1323.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.32.1323 - 8. Sasaki, M., Shiromizu, T. and Maeda, K. (2000) Physical Review D, 62, Article ID: 024008.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.62.024008 - 9. Maartens, R. (2007) Lecture Notes in Physics, 720, 323-332.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-71013-4_11 - 10. Choquet-Bruhat, Y. (1969) Communications in Mathematical Physics, 12, 16-35.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01646432 - 11. Choquet-Bruhat, Y. (1977) General Relativity and Gravitation, 8, 561-571.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00756307 - 12. Slagter, R.J. (1986) Astrophysical Journal, Part 1, 307, 20-29.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/164388 - 13. Slagter, R.J. (2016) Nonlinear Gravitational Waves as Dark Energy in Warped Spacetimes. In: Ruffini, R., Ed., Proceedings of the 14th Marcell Grossmann Meeting, to appear.

- 14. Stachel, J.J. (1968) Journal of Mathematical Physics, 7, 1321.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.1705036