Journal of Modern Physics

Vol.5 No.1(2014), Article ID:42257,10 pages DOI:10.4236/jmp.2014.51006

Generalization of Abelian Gauge Symmetry, Dark Matter and Cosmological Expansion

1Department of Applied Mathematics, State Social University of Russia, Moscow, Russia

2Department of Experimental Physics, Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia, Moscow, Russia

3Astro Space Centre of Lebedev Physics Institute, Moscow, Russia

4Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Autonoma del Estado de Mexico, Toluca, Mexico

Email: trn11@rambler.ru; maaguerog@uaemex.mx

Received November 20, 2013; revised December 15, 2013; accepted January 3, 2014

ABSTRACT

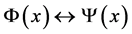

A commutative generalization of the  gauge symmetry group is proposed. The two-parametric family of two-connected abelian Lie groups is obtained. The necessity of existence of so-called imaginary charges and electromagnetic fields with negative energy density (dark photons) is derived. The possibilities when the overall Lagrangian represents a sum or difference of two identical Lagrangians for the visible and hidden sectors (i.e. copies of unbroken

gauge symmetry group is proposed. The two-parametric family of two-connected abelian Lie groups is obtained. The necessity of existence of so-called imaginary charges and electromagnetic fields with negative energy density (dark photons) is derived. The possibilities when the overall Lagrangian represents a sum or difference of two identical Lagrangians for the visible and hidden sectors (i.e. copies of unbroken ) are ruled out by the extended symmetry. The distinction between the two types of fields resides in the fact that for one of them current and electromagnetic kinetic terms in Lagrangians are identical in sign, whereas for another type these terms are opposite in sign. As a consequence, and in contrast to the common case, like imaginary charges attract and unlike charges repel. Some cosmological issues of the proposed hypothesis are discussed. Particles carrying imaginary charges are proposed as one of the components of dark matter. Such a matter would be imaginarily charged on a large scale for the reason that dark atoms carry non-compensated charges. It leads to important predictions for matter distribution, interaction and other physical properties being different from what is observed in dominant dark matter component in the standard model. These effects of imaginary charges depend on their density and could be distinguished in future observations. Dark electromagnetic fields can play crucial dynamical role in the very early universe as they may dominate in the past and violate weak energy condition which provides physical grounds for bouncing cosmological scenarios pouring a light on the problem of origin of the expanding matter flow.

) are ruled out by the extended symmetry. The distinction between the two types of fields resides in the fact that for one of them current and electromagnetic kinetic terms in Lagrangians are identical in sign, whereas for another type these terms are opposite in sign. As a consequence, and in contrast to the common case, like imaginary charges attract and unlike charges repel. Some cosmological issues of the proposed hypothesis are discussed. Particles carrying imaginary charges are proposed as one of the components of dark matter. Such a matter would be imaginarily charged on a large scale for the reason that dark atoms carry non-compensated charges. It leads to important predictions for matter distribution, interaction and other physical properties being different from what is observed in dominant dark matter component in the standard model. These effects of imaginary charges depend on their density and could be distinguished in future observations. Dark electromagnetic fields can play crucial dynamical role in the very early universe as they may dominate in the past and violate weak energy condition which provides physical grounds for bouncing cosmological scenarios pouring a light on the problem of origin of the expanding matter flow.

Keywords:Cosmology of Theories beyond the SM; Cosmic Singularity; Dark Energy Theory; Dark Matter Theory

1. Introduction

The idea of interactions (even long-range  interactions) in the dark sector is not new [1]. As mentioned in [2], an attractive non-gravitational force between DM concentrations is not only well-motivated theoretically, it may resolve some discomforts with conventional

interactions) in the dark sector is not new [1]. As mentioned in [2], an attractive non-gravitational force between DM concentrations is not only well-motivated theoretically, it may resolve some discomforts with conventional ![]() CDM. A new kind of photon, which couples to dark matter but not to ordinary matter, has been recently proposed by L. Ackerman et al. [3]. DM could be weakly coupled to long-range forces, which might be related to dark energy. One difficulty with the latter is that such forces are typically mediated by scalar fields, and it is hard to construct natural models in which the scalar field remains massless (to provide a long-range force) while interacting with the DM at an interesting strength. The authors point out that the dark photon comes from gauge symmetry, just like the ordinary photon, and its masslessness is therefore completely natural. The proposed Lagrangians for the dark sector are of the type

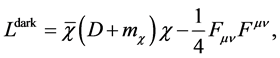

CDM. A new kind of photon, which couples to dark matter but not to ordinary matter, has been recently proposed by L. Ackerman et al. [3]. DM could be weakly coupled to long-range forces, which might be related to dark energy. One difficulty with the latter is that such forces are typically mediated by scalar fields, and it is hard to construct natural models in which the scalar field remains massless (to provide a long-range force) while interacting with the DM at an interesting strength. The authors point out that the dark photon comes from gauge symmetry, just like the ordinary photon, and its masslessness is therefore completely natural. The proposed Lagrangians for the dark sector are of the type

(1)

(1)

where  and

and  is the field-strength tensor for the dark photons. In essence, proposed here and in some analogous works are several exact copies of

is the field-strength tensor for the dark photons. In essence, proposed here and in some analogous works are several exact copies of . But, given the importance of symmetries in the SM, could we get an understanding as to where the additional

. But, given the importance of symmetries in the SM, could we get an understanding as to where the additional  comes from? This is our main motivation of the present work.

comes from? This is our main motivation of the present work.

In general, most SM extensions include hidden sectors, i.e. sectors which couple only very weakly, typically gravitationally, to the SM fields and these hidden sectors (if any) contain undoubtedly gauge groups as well. We suppose it is from a mechanism of extension of known groups. Because of this, simple copies of  are of course unlikely, since any true generalization is perceived to gain a more penetrating insight into the symmetry. It should be remembered that “More is different” [4]. The philosophy of symmetry implies that entities involved are at once similar and dissimilar to one another. Dissimilarity (even contrast) is of the same importance as similarity.

are of course unlikely, since any true generalization is perceived to gain a more penetrating insight into the symmetry. It should be remembered that “More is different” [4]. The philosophy of symmetry implies that entities involved are at once similar and dissimilar to one another. Dissimilarity (even contrast) is of the same importance as similarity.

While on the subject of extension of electromagnetism, one should comply with some obvious rules. Firstly, such a simple thing as electromagnetism must certainly come from an abelian gauge group. Secondly, this group must be a non-trivial extension of the common  (not merely a direct sum

(not merely a direct sum ). Thirdly, the new sector, inhabited by particles charged under the new symmetry, should represent a symmetrical image of the known sector, with some properties complementing each other.

). Thirdly, the new sector, inhabited by particles charged under the new symmetry, should represent a symmetrical image of the known sector, with some properties complementing each other.

Two decades ago Ya.P. Terletsky advanced the hypothesis about the existence of so-called imaginary charges (IC) and electromagnetic fields with negative energy density (“minus-fields”) [5]. The term “imaginary charge” is due to the formal substitution of imaginary values  for real values

for real values  into the Coulomb law. In that case like charges would attract and unlike charges would repel. It is precisely this property that represents the basic physical distinction of IC from common charges, while their representation as imaginary quantities is nothing more than a mathematical tool.

into the Coulomb law. In that case like charges would attract and unlike charges would repel. It is precisely this property that represents the basic physical distinction of IC from common charges, while their representation as imaginary quantities is nothing more than a mathematical tool.

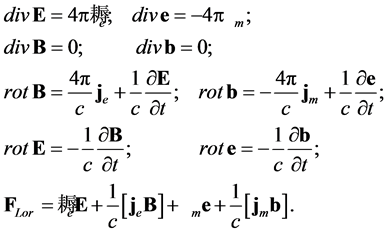

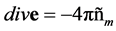

The phenomenological deduction of equations for IC is just based on such a substitution of imaginary charges and fields into the Maxwell equations and the Lorentz force law. One possibility for such equations is the following:

(2)

(2)

Here  are common and “minus” fields respectively and

are common and “minus” fields respectively and  represent their sources. The only peculiarity is the “wrong” sign in front of the sources

represent their sources. The only peculiarity is the “wrong” sign in front of the sources  and

and  in the equations for “minus” fields, meanwhile the Lorentz force law is unchanged. This causes profound alterations in the physics of IC. In particular, one can see from the Coulomb law

in the equations for “minus” fields, meanwhile the Lorentz force law is unchanged. This causes profound alterations in the physics of IC. In particular, one can see from the Coulomb law  and the electrostatic force

and the electrostatic force  that like charges would attract and unlike charges would repel. In a similar way equally directed currents would repel, in contrast to the common case.

that like charges would attract and unlike charges would repel. In a similar way equally directed currents would repel, in contrast to the common case.

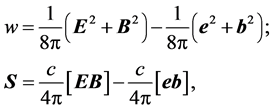

A standard deduction of Poynting’s theorem from (2) brings the following expressions for the energy density and the Poynting vector:

(3)

(3)

whence it follows that the energy density of minus-fields is negative. G.E. Marsh points out that “… the idea of negative energy states is still quite controversial and much confused in the literature. On the other hand, presently the behavior of the universe makes difficult to resist the idea that some negative energy matter (socalled dark energy) could contribute and repel the matter, creating the observed phenomena at large red shifts” [6]. At this point, there is no escape from citing A. Linde [7]: “This removes the old prejudice that, even though the overall change of sign of the Lagrangian (i.e. both of its kinetic and potential terms) does not change the solutions of the theory, one must say that the energy of all particles is positive. This prejudice was so strong, that many years ago physicists preferred to quantize particles with negative energy as antiparticles with positive energy, which caused the appearance of such meaningless concepts as negative probability. We wish to emphasize that there is no problem to perform a consistent quantization of theories which describe particles with negative energy. All difficulties appear only when there exist interacting species with both signs of energy”.

Note that the term “imaginary charges” has been used to designate different things. Firstly there exists a well-known technique of replacing conducting surfaces by “imaginary charges” in electrostatics (the method of images). Secondly there is a notion of sources at imaginary space-time, which are called imaginary sources in short [8]. Thirdly, speculations representing gravitation as electrostatics with an imaginary charge are sometimes encountered. Our hypothesis has nothing to do with these uses of the term.

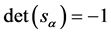

The aim of this article is to demonstrate the necessity of existence of IC and fields with negative energy density from first symmetry principles. The plan to be followed consists in finding a natural Abelian extension of . We take as the starting point the single idea of extension to matrices with determinant equal to -1 (however, for reasons of commutativity, axes reflections would not do here).

. We take as the starting point the single idea of extension to matrices with determinant equal to -1 (however, for reasons of commutativity, axes reflections would not do here).

It turns out that one way to accomplish this task is an extended understanding of the variational principle. Since equations of motion result from making the first variation of action equal to zero, the change of sign of a Lagrangian does not affect dynamical equations. It should be reminded in this connection that the variation principle would be more correctly said to be the principle of stationary (and not minimal) action and at real trajectories the action takes extreme rather than minimal values. Hence it is sufficient to require the invariance of Lagrangians up to change of sign.

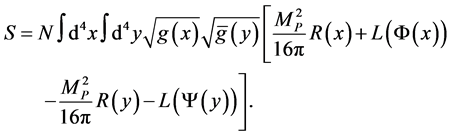

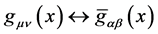

The double universe model proposed by A. Linde is of particular interest in this respect. This model describes two universes, ![]() and

and , with coordinates

, with coordinates  and

and , respectively and with metrics

, respectively and with metrics  and

and  , containing fields

, containing fields  and

and  with the action of the following type:

with the action of the following type:

(4)

(4)

A novel symmetry of the action is the symmetry under the transformation mixing the fields ,

,  and under the subsequent change of the overall sign,

and under the subsequent change of the overall sign,![]() . Linde calls this the antipodal symmetry, since it relates to each other the states with positive and negative energies.

. Linde calls this the antipodal symmetry, since it relates to each other the states with positive and negative energies.

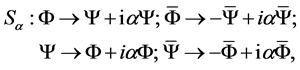

In Section 2 the non-commutative extension of  is constructed. In Section 3 some alternatives concerning the possibilities when the overall Lagrangian represents a sum or difference of two identical Lagrangians for the visible and hidden sectors, are discussed. In Section 4 a complex scalar field representation of our model is constructed. In Section 5 the possibility of mixing terms in Lagrangians describing interactions between common and imaginary charges, is discussed. Section 6 is devoted to a general consideration of the model, not mostly restricted to the infinitesimal case. In Section 7 some cosmological issues are discussed. In particular, we propose particles carrying imaginary charges as one of the components of dark matter.

is constructed. In Section 3 some alternatives concerning the possibilities when the overall Lagrangian represents a sum or difference of two identical Lagrangians for the visible and hidden sectors, are discussed. In Section 4 a complex scalar field representation of our model is constructed. In Section 5 the possibility of mixing terms in Lagrangians describing interactions between common and imaginary charges, is discussed. Section 6 is devoted to a general consideration of the model, not mostly restricted to the infinitesimal case. In Section 7 some cosmological issues are discussed. In particular, we propose particles carrying imaginary charges as one of the components of dark matter.

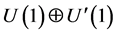

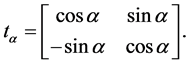

2. Extension of U(1)

The generalization is based on the following reasoning. The  group is isomorphic to the special orthogonal group

group is isomorphic to the special orthogonal group  , which represents the group of orthogonal

, which represents the group of orthogonal  matrices with unit determinant:

matrices with unit determinant:

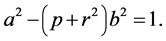

(5)

(5)

An extension to matrices with determinant equal to  may be performed by adding axes reflections. However, by this way one obtains the complete orthogonal group

may be performed by adding axes reflections. However, by this way one obtains the complete orthogonal group , which is non-commutative even in the case of two dimensions. This is inconsistent with our attempt to derive the existence of minus-fields analogically to electromagnetic ones, i.e. from a commutative group of lagrangian symmetries.

, which is non-commutative even in the case of two dimensions. This is inconsistent with our attempt to derive the existence of minus-fields analogically to electromagnetic ones, i.e. from a commutative group of lagrangian symmetries.

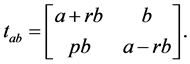

Let us note that matrices (5) are circulant ones, which is to say that they are of the form

(6)

(6)

with . For any fixed value of

. For any fixed value of![]() , non-degenerate matrices (6) form a commutative group. It may be symbolized as

, non-degenerate matrices (6) form a commutative group. It may be symbolized as  or

or , i.e.

, i.e. ![]() -circulant

-circulant  matrices with real or complex entries. In case that

matrices with real or complex entries. In case that , they are designated briefly as circulant matrices.

, they are designated briefly as circulant matrices.

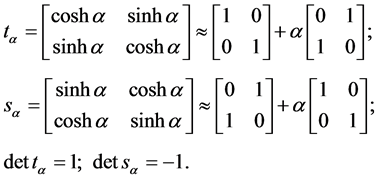

It is possible to construct a commutative group of circulant  matrices depending on one real parameter and with determinants equal to

matrices depending on one real parameter and with determinants equal to , i.e.

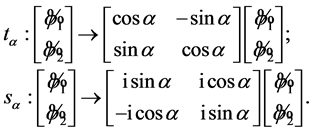

, i.e. . The group consists of elements of two types having the following general and infinitesimal representations:

. The group consists of elements of two types having the following general and infinitesimal representations:

(7)

(7)

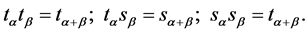

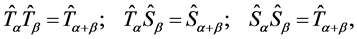

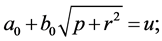

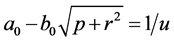

As may be seen from (7), the elements  and

and ![]() are different in that the unity and the generator switch places. The group multiplication table is of the form

are different in that the unity and the generator switch places. The group multiplication table is of the form

(8)

(8)

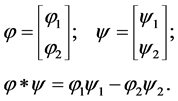

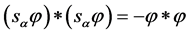

Let us consider the group representation space as doublets of real scalar fields with the scalar product defined using an indefinite metric:

(9)

(9)

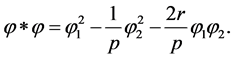

Then the quadratic form  proves to be invariant under transformations

proves to be invariant under transformations  and changes sign under transformations

and changes sign under transformations![]() :

:

(10)

(10)

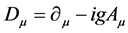

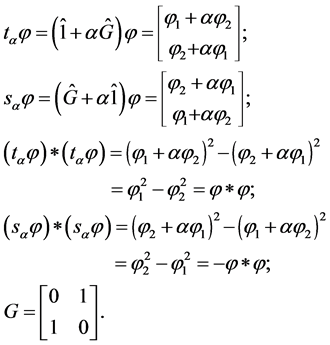

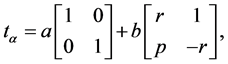

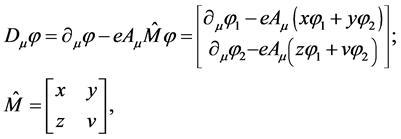

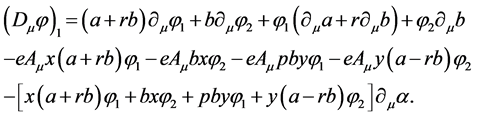

By analogy with the common case, let us define covariant derivatives as

(11)

(11)

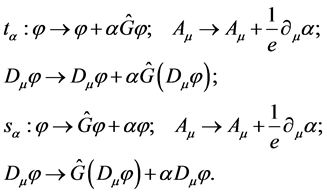

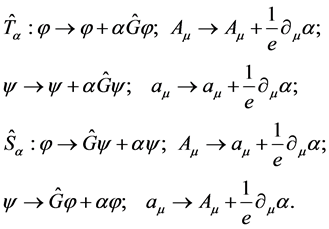

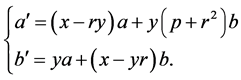

Then under simultaneous transformations of field variables and gradient transformations of potentials, covariant derivatives are transformed in the same way as fields:

(12)

(12)

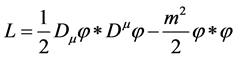

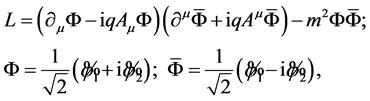

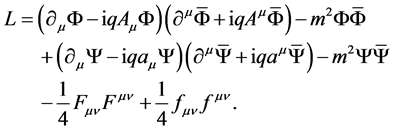

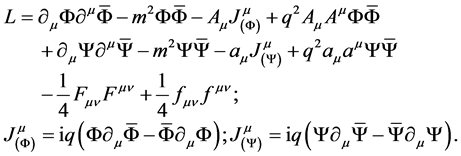

Consequently, the Lagrangian

(13)

(13)

is invariant under transformations  and changes sign under transformations

and changes sign under transformations![]() . Hence the invariance of dynamical equations under the extended Abelian group of transformations is achieved by the invariance of Lagrangians up to change of sign.

. Hence the invariance of dynamical equations under the extended Abelian group of transformations is achieved by the invariance of Lagrangians up to change of sign.

However the constructed symmetry breaks down on addition of the kinetic term describing free electromagnetic fields:

(14)

(14)

The tensor  does not change under transformations (12), so under

does not change under transformations (12), so under ![]() the first two terms of the Lagrangian (14) reverse sign, whereas the last term does not change. The overall Lagrangian (14) turns out to be non-invariant, even up to change of sign!

the first two terms of the Lagrangian (14) reverse sign, whereas the last term does not change. The overall Lagrangian (14) turns out to be non-invariant, even up to change of sign!

It is not possible to restore the symmetry without incorporation of new entities. Another field ![]() must exist in addition to the usual field

must exist in addition to the usual field![]() . The field

. The field ![]() interacts with its own gauge field

interacts with its own gauge field , but with the same values of the constants

, but with the same values of the constants ![]() and

and . However the kinetic terms of the fields

. However the kinetic terms of the fields  and

and  are opposite in sign:

are opposite in sign:

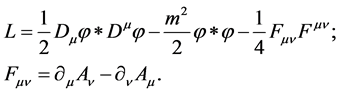

(15)

(15)

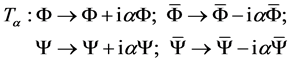

In order to bring about invariance of the Lagrangian (15) up to change of sign, transformations ![]() must be accompanied by mixing of the fields

must be accompanied by mixing of the fields ![]() and

and![]() . Let us denote such transformations by capital letters:

. Let us denote such transformations by capital letters:

(16)

(16)

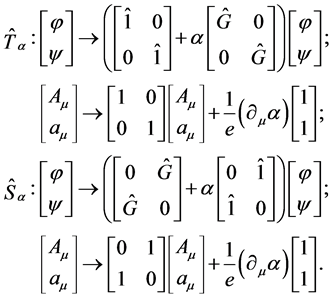

The representation of (16) in terms of matrices is of the form:

(17)

(17)

It is seen that the group multiplication table is the same as (8):

(18)

(18)

that is to say, we are dealing with a representation of the same group (four-dimensional at this time).

Each term of the Lagrangian (15) is invariant under transformations![]() . As for transformations

. As for transformations , the kinetic terms with covariant derivatives and the mass terms change sign and convert to one another, the kinetic terms of the gauge fields convert to one another without change of sign:

, the kinetic terms with covariant derivatives and the mass terms change sign and convert to one another, the kinetic terms of the gauge fields convert to one another without change of sign: , but their difference changes sign. By this means, the overall sign of the Lagrangian (15) changes.

, but their difference changes sign. By this means, the overall sign of the Lagrangian (15) changes.

3. Discussion of Alternatives

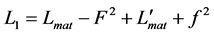

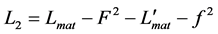

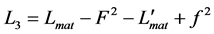

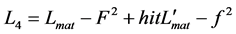

There is another possibility. The following Lagrangian may be written instead of (15):

(19)

(19)

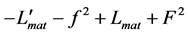

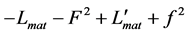

Whereas the Lagrangian (15) may be schematically presented as , the expression (19) is of the form

, the expression (19) is of the form . The Lagrangian (15a) is completely invariant under transformations

. The Lagrangian (15a) is completely invariant under transformations ![]() and

and , without change of sign. In this schematic notation, the Lagrangian in the model of A. Linde (4) may be written as a difference of two identical Lagrangians:

, without change of sign. In this schematic notation, the Lagrangian in the model of A. Linde (4) may be written as a difference of two identical Lagrangians: , and Lagrangians in models with hidden sectors representing copies of

, and Lagrangians in models with hidden sectors representing copies of  (for instance, L. Ackerman et al.) as a sum of two identical Lagrangians:

(for instance, L. Ackerman et al.) as a sum of two identical Lagrangians: .

.

As mentioned above, in order to bring about invariance of the Lagrangian (15) (i.e.  in the schematic notation) up to change of sign, transformations

in the schematic notation) up to change of sign, transformations  in (16) are accompanied by mixing of the fields

in (16) are accompanied by mixing of the fields ![]() and

and![]() .The question arises as to whether another choice might provide invariance of

.The question arises as to whether another choice might provide invariance of ![]() and/or

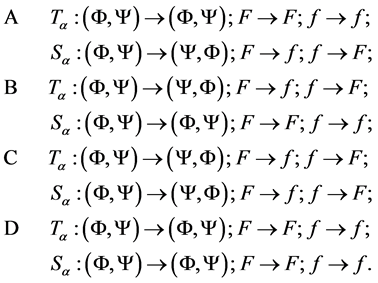

and/or![]() ? Let us denote possible variants as A, B, C, and D:

? Let us denote possible variants as A, B, C, and D:

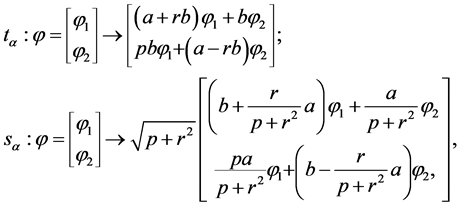

The variant A represents (16) where common transformations  are not accompanied by mixing of fields while “imaginary” transformations

are not accompanied by mixing of fields while “imaginary” transformations  mix fields. The variant B represents the reverse case where only

mix fields. The variant B represents the reverse case where only ![]() are accompanied by mixing of fields. In the variant C both

are accompanied by mixing of fields. In the variant C both ![]() and

and  mix fields. Finally, none of the transformations mix fields in the variant D. The point is that there are no other possibilities apart from A, B, C, and D, since any mixing of fields must be inevitably accompanied by mixing of potentials

mix fields. Finally, none of the transformations mix fields in the variant D. The point is that there are no other possibilities apart from A, B, C, and D, since any mixing of fields must be inevitably accompanied by mixing of potentials  and, consequently,

and, consequently,  (otherwise covariant derivatives would be non-invariant, even up to change of sign).

(otherwise covariant derivatives would be non-invariant, even up to change of sign).

Let us remind that “imaginary” transformations  reverse signs of material Lagrangians

reverse signs of material Lagrangians  and both

and both ![]() and

and  keep signs of field-strength tensors

keep signs of field-strength tensors . This game of signs leads to the conclusion that the only valid possibility is the variant A applied to

. This game of signs leads to the conclusion that the only valid possibility is the variant A applied to  or

or![]() . There is no other way in which a Lagrangian can be invariant, even up to change of sign. By way of example, let us examine what happens to the Lagrangian

. There is no other way in which a Lagrangian can be invariant, even up to change of sign. By way of example, let us examine what happens to the Lagrangian ![]() under the transformations. In case of A, it is invariant under

under the transformations. In case of A, it is invariant under ![]() and converts to

and converts to , which represents neither

, which represents neither  nor

nor , under

, under . Analogically, in cases of B and C it converts to

. Analogically, in cases of B and C it converts to  under

under![]() , while

, while  represents a problem once again. Finally, in case of D, it is invariant under

represents a problem once again. Finally, in case of D, it is invariant under ![]() and converts to

and converts to  under

under . The latter expression is neither

. The latter expression is neither  nor

nor .

.

So, the possibilities when the overall Lagrangian represents a sum  or difference

or difference  of two identical Lagrangians for the visible and hidden sectors are ruled out by the extended symmetry. The reason is that this group imposes more rigid restrictions on the structure of Lagrangian’s terms than the common

of two identical Lagrangians for the visible and hidden sectors are ruled out by the extended symmetry. The reason is that this group imposes more rigid restrictions on the structure of Lagrangian’s terms than the common . Indeed, now that we have a two-connected group, we need to ensure invariance (up or not to change of sign) under both types of transformations

. Indeed, now that we have a two-connected group, we need to ensure invariance (up or not to change of sign) under both types of transformations ![]() and

and .

.

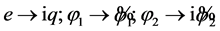

4. Complex Scalar Field Representation

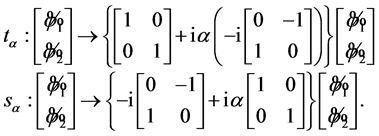

A more conventional representation is constructible. The substitution when  (imaginary charges!), transforms the Lagrangian (13) to

(imaginary charges!), transforms the Lagrangian (13) to

(20)

(20)

which represents a common Lagrangian for complex scalar fields![]() . Then the transformations (10) take the form (with

. Then the transformations (10) take the form (with  in place of

in place of ):

):

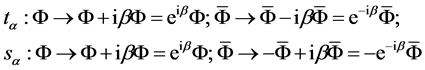

(21)

(21)

and in both cases

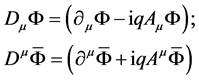

. It can be shown that in this case, too, covariant derivatives

. It can be shown that in this case, too, covariant derivatives

(22)

(22)

are transformed according to (21), that is, in the same manner as the fields  and consequently the Lagrangian (20) is invariant under transformations

and consequently the Lagrangian (20) is invariant under transformations  and changes sign under

and changes sign under![]() .

.

The transformations (21) in terms of real and imaginary parts of  look like (writing

look like (writing  for

for ):

):

(23)

(23)

Let us rewrite (23) in infinitesimal form separating out the imaginary unit, as is the convention in the standard form of gauge transformations

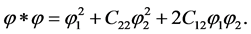

(24)

Here ![]() is the dimension of the gauge group (1 in this case),

is the dimension of the gauge group (1 in this case),  is the dimension of the representation (1 in this case),

is the dimension of the representation (1 in this case),  are group generators. The expressions (23) assume the form:

are group generators. The expressions (23) assume the form:

(25)

(25)

It is seen once again from (25) that the elements  and

and ![]() are different in that the unity and the twodimensional rotation generator

are different in that the unity and the twodimensional rotation generator  switch places. The multiplication table is of the form (8).

switch places. The multiplication table is of the form (8).

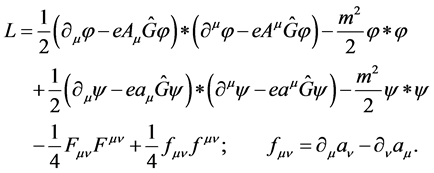

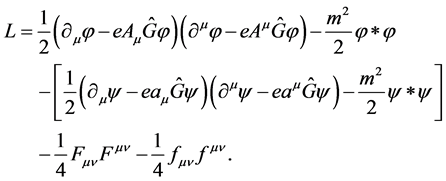

From the preceding, it may be seen that the analogue of the Lagrangian (15) looks like:

(26)

(26)

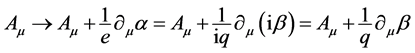

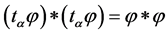

Equation (26) is invariant under the transformations

(27)

(27)

and changes sign under the transformations

(28)

(28)

whereas the potentials are transformed exactly as in (17), with substitution![]() . The transformations (27), (28) may be rewritten in a matrix form analogous to (17).

. The transformations (27), (28) may be rewritten in a matrix form analogous to (17).

The Lagrangian (26) may be represented in a standard form separating out currents:

(29)

Hence, the difference between the two types of fields resides in the fact that for one of them current and electromagnetic kinetic terms are identical in sign, whereas for another type these terms are opposite in sign. In the former case, varying with respect to field variables and currents, one obtains the conventional Maxwell equations and the Lorentz force law. Otherwise, the equations (2) with imaginary charges and negative energy density result. Let us notice that in case of the Lagrangian (19) the same equations are derivable, since there is no interaction between the two types of currents and the variation over them is performed independently. The physics does not depend on the overall sign of the Lagrangian (or part of it subject to variation) but on the relation between the signs of its terms.

For definiteness, we took ![]() to be a scalar, though everything may be rewritten in terms of fermions as well.

to be a scalar, though everything may be rewritten in terms of fermions as well.

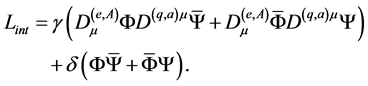

5. Possibility of Connectors

Let us discuss the possibility of mixing terms in Lagrangians describing interactions between common and imaginary charges, i.e. a connector sector linking hidden and visible sectors. It is very tempting to have such a connector, since it gives rise to new phenomenology and implications for dark matter detection possibilities and technological applications (perhaps including perpetuum mobile of the first kind!). However it is a rather delicate question, since such an interaction may lead to a breakdown ofthe vacuum due to negative energy fields. Theories of interacting fields in which some fields appear with each sign of kinetic term are generically unstable. The theory does not possess a vacuum; even classically the evolution will lead to disastrous exponentially growing excitations with compensating-sign energy contribution. Quantum mechanically it is not clear how to quantize the interacting theory; even in the absence of gravity, the usual approach by analytical continuation from Euclidean space does not make sense because there is no Euclidean partition function. This is why in most models the two copies of the standard model matter fields, corresponding to positive and negative energy, interact only weakly through gravity, i.e. any connector sector is missing (or is multiplied by extremely small constants). Note that even if there are no non-gravitational interactions between sectors with opposite-sign Lagrangians, mutual interactions with gravity may be already sufficient to ensure the instability of the most natural vacuum, and this possibility is firmly ruled out by some authors [9]. However, since currently there is still no complete and consistent quantum theory of gravity, much remains to be seen here.

As mentioned above, the extended gauge group imposes more rigid restrictions on the structure of Lagrangian’s terms than the common . Thus a most usual mixing term

. Thus a most usual mixing term  is invariant under the transformations (27) - (28) and so it may not be incorporated into the Lagrangian (26), as the latter must change sign under (28). However, this term may be included in the Lagrangian (19) which is invariant under all transformations. Most likely it is impossible to set up a quadratic term mixing

is invariant under the transformations (27) - (28) and so it may not be incorporated into the Lagrangian (26), as the latter must change sign under (28). However, this term may be included in the Lagrangian (19) which is invariant under all transformations. Most likely it is impossible to set up a quadratic term mixing  and

and  that would be invariant under (27) and would change sign under (28). It can also be seen that the mixing kinetic and Yukawa-like terms are invariant under

that would be invariant under (27) and would change sign under (28). It can also be seen that the mixing kinetic and Yukawa-like terms are invariant under ![]() and change sign under

and change sign under :

:

(30)

(30)

Note that the change of sign occurs in a non-trivial way, since mutually conjugated terms in (30) switch places under transformations .

.

6. The U(1) Extension: General Consideration

The above-described extension of the  group is limited to the two possible values of the parameter in circulant matrices (6):

group is limited to the two possible values of the parameter in circulant matrices (6):  . Besides, the presentation is mostly restricted to the infinitesimal case. In this section let us develop a more systematic approach. We start with the most general form of

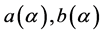

. Besides, the presentation is mostly restricted to the infinitesimal case. In this section let us develop a more systematic approach. We start with the most general form of  commutative matrices:

commutative matrices:

(31)

(31)

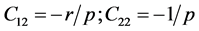

For any fixed values of ![]() and

and![]() , non-degenerate matrices (31) form a commutative group. We would like to construct an one-parametric group, so

, non-degenerate matrices (31) form a commutative group. We would like to construct an one-parametric group, so  and

and  are assumed to be functions of a single parameter

are assumed to be functions of a single parameter  depending on space-time coordinates:

depending on space-time coordinates:

. Hence,

. Hence,  will be denoted as

will be denoted as . The condition

. The condition  imposes the relation between

imposes the relation between  and

and :

:

(32)

(32)

In what follows, we assume . Let us consider a quadratic form in the linear space of doublets of real scalar fields:

. Let us consider a quadratic form in the linear space of doublets of real scalar fields:

(33)

(33)

It follows from the requirement of invariance of (33) under transformations :

: , that

, that  and the scalar product takes the form

and the scalar product takes the form

(34)

(34)

In order to construct matrices with determinant , let us arrange (31) in the form of a sum

, let us arrange (31) in the form of a sum

(35)

(35)

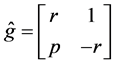

where the first matrix (unity) represents  with

with , and the second matrix

, and the second matrix

(36)

(36)

represents  with

with . The matrix

. The matrix  can be considered as a “generator”, even though the relation (35) is not infinitesimal. We will seek for matrices with determinant

can be considered as a “generator”, even though the relation (35) is not infinitesimal. We will seek for matrices with determinant  in the form

in the form , where

, where  is a constant. Requiring

is a constant. Requiring , one obtains

, one obtains

(37)

(37)

It can be easily verified (taking into account (32)) that the quadratic form (34) changes sign under transformations (37): .

.

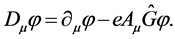

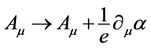

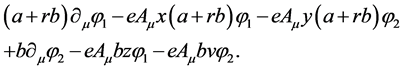

The next step consists in introducing covariant derivatives

(38)

(38)

where we introduce a completely arbitrary matrix . The fields are transformed as follows:

. The fields are transformed as follows:

(39)

while the gauge field is subject to the gradient transformation: . Inserting the components of fields, transformed under

. Inserting the components of fields, transformed under , from (39) to (38), one obtains the first transformed component of the covariant derivative:

, from (39) to (38), one obtains the first transformed component of the covariant derivative:

(40)

Covariant derivatives are transformed in the same way as fields, i.e. (40) must be equal to

(41)

(41)

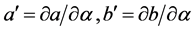

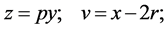

Equating (40) and (41), one obtains (denoting

):

):

(42)

(42)

(43)

(43)

It is notable that the consideration of the second component of the covariant derivative transformed under , as well as both components transformed under

, as well as both components transformed under![]() , leads to the same relations (42) - (43). In other words, (42) - (43) are quite sufficient to provide correct transformations of covariant derivatives (38).

, leads to the same relations (42) - (43). In other words, (42) - (43) are quite sufficient to provide correct transformations of covariant derivatives (38).

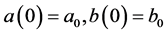

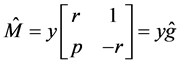

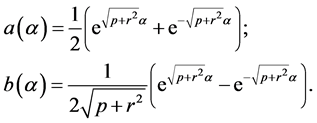

The exact solution of the system (43) with the initial conditions  is as follows

is as follows

(44)

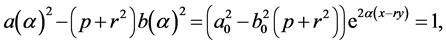

The determinant (32) must be equal to 1:

(45)

(45)

whence it follows that ![]() and

and .

.

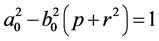

This condition will be satisfied if

. However, the multiplication rules (8) imply

. However, the multiplication rules (8) imply![]() . The matrix

. The matrix  takes the form

takes the form

(46)

(46)

and one may put  without loss of generality. Thus, finally, we obtain the expressions for

without loss of generality. Thus, finally, we obtain the expressions for  as follows:

as follows:

(47)

(47)

To summarize, the extended commutative gauge groups consist of matrices (31) and (37) with entries that depend on one real parameter and are given by (47). The family of these Lie groups is parameterized by two parameters:![]() . Compactness or non-compactness depends on the values of these constants. As seen from (32), a group will be compact if

. Compactness or non-compactness depends on the values of these constants. As seen from (32), a group will be compact if  and non-compact otherwise. The groups are two-connected. The Lagrangian (13) in which the scalar product and the covariant derivatives are now given by (34) and (38) respectively, is invariant under transformations

and non-compact otherwise. The groups are two-connected. The Lagrangian (13) in which the scalar product and the covariant derivatives are now given by (34) and (38) respectively, is invariant under transformations  and changes sign under transformations

and changes sign under transformations ![]() (accompanied by gradient transformations of

(accompanied by gradient transformations of ).

).

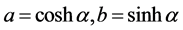

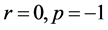

In case that , the expressions (47) take the form

, the expressions (47) take the form  and we come to the case (7) with covariant derivatives given by (11). In case of

and we come to the case (7) with covariant derivatives given by (11). In case of , the case (23) results.

, the case (23) results.

7. Cosmological Issues

Clearly the existence of IC and “minus” fields leads to important physical conclusions which could have interesting consequences for both, cosmological structure on all scales and dynamics of the very early universe, and pour a light on the key scientific problems facing the modern cosmology (e.g., [10]).

We propose particles carrying imaginary charges as one of the components of dark matter. J.L. Feng points out that “... it is still not at all difficult to invent new particles that satisfy all the constraints, and there are candidates motivated by minimality, particles motivated by possible experimental anomalies, etc.” [11]. Our candidate is motivated by the logic of the gauge group’s natural extension. Just as common electromagnetic fields exist in order to compensate the effect of local gauge transformations, so minus-fields are designed to compensate transformations under the extended group. If one estimates the coupling and mass scales of the visible and hidden sectors on the same order of magnitude then imaginary charges would interact (in its sector) like ordinary particles in the visible world, which is a strong effect in comparison to weakly interacting particles of the dominant dark matter in standard cosmology. For this reason the spatial distribution of IC-matter would differ essentially from baryonic and dominant dark matter components.

Let us assume that the IC-component comprises of atomic bound states. Then it will be imaginary charged on large scale because imaginary “protons” and “positrons” combine into atoms (like charges attract) that carry a non-compensated charge. Hence the ability of this matter for accumulation is enhanced while oppositely charged atoms are pushed out remotely elsewhere in the Universe (unlike charges repel). Thus we may expect fragmentation or clustering of the IC-matter in some compact objects or even in separate galaxies or groups of galaxies what increases the probability for the matter detection through gravitational deviations (from GR) on large scales. Considering the current accuracy of data not better than ![]() we can conclude that the proposed IC-component of dark matter should be subdominant with the density parameter

we can conclude that the proposed IC-component of dark matter should be subdominant with the density parameter  comparable to that of baryonic matter.

comparable to that of baryonic matter.

On smaller scales IC-matter could exist either in collapsed state (conceivably in galactic centers and other astrophysical objects) or in the form of gas clouds and balls of plasma where mutual coulomb attraction is compensated by gas pressure. Gravitational collapse of IC-balls at high red-shifts can stimulate the formation of primordial black holes providing natural seeds for a successive formation of massive black holes in the early Universe through the processes of merging and accretion of the standard matter. This effect could help solving the problem of super massive black holes observed in the centers of distant galaxies (e.g., [12]). Also, one might expect the existence of some exotic condensed states and phase transitions.

Consequently, there exist (dark) electromagnetic fields with negative energy density on cosmological scales (the reviving of the idea of Faradayan cosmology [13]). The current density of dark photons is negligible as they are redshifted away because of the cosmological expansion. However, minus-fields could play an important dynamical role in the past helping to solve the problem of cosmological singularity. Taking into account such properties of dark radiation as violation of the weak energy condition [14] and growth of the energy density modulus when extrapolating in the past, brings about the conclusion that such a matter in the early universe may crucially rebuild its evolution avoiding the singularity and providing sufficient conditions for a cosmological bounce at high energies.

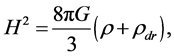

Let us consider this important effect in more detail. In the presence of dark radiation  in early universe the Friedmann equation takes the following form:

in early universe the Friedmann equation takes the following form:

(48)

(48)

where  and

and  are Hubble and scale factors respectively,

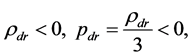

are Hubble and scale factors respectively,  is the energy density of standard matter. Assuming that dark photons interact with other matter only gravitationally and their density and pressure are negative:

is the energy density of standard matter. Assuming that dark photons interact with other matter only gravitationally and their density and pressure are negative:

(49)

(49)

we obtain from the energy conservation equation:

(50)

(50)

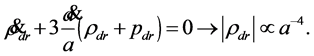

Therefore, if the trace of standard matter is positive  then the right-hand-side of equation (48) turns to zero at some moment in the past ensuring a bounce at this point. Below we demonstrate the bounce on the example of two simple cosmological models.

then the right-hand-side of equation (48) turns to zero at some moment in the past ensuring a bounce at this point. Below we demonstrate the bounce on the example of two simple cosmological models.

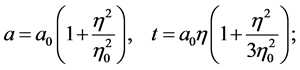

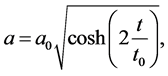

First, we consider a non-relativistic matter,  , where Equation (48) yields:

, where Equation (48) yields:

(51)

(51)

and

and  are positive constants,

are positive constants, . Another example is a constant density field,

. Another example is a constant density field,  (say, an inflaton at the beginning of slow-roll evolution):

(say, an inflaton at the beginning of slow-roll evolution):

(52)

(52)

where  is another pair of positive constants. In both cases for

is another pair of positive constants. In both cases for ,

,  , while at earlier (later) period of time the formulae describe cosmological contraction (expansion). At

, while at earlier (later) period of time the formulae describe cosmological contraction (expansion). At  the contribution of dark photons in total density becomes negligible. At the same time, usual radiation can play a dominant role there if they originate in the process of relaxation of standard matter, for instance, after decay of inflaton (see Equation (52)).

the contribution of dark photons in total density becomes negligible. At the same time, usual radiation can play a dominant role there if they originate in the process of relaxation of standard matter, for instance, after decay of inflaton (see Equation (52)).

Summarily, we can conclude that IC and dark photons could well be those missing elements of extended cosmological model which would naturally answer the key problems raised by observational cosmology and yet unsolved presently.

REFERENCES

- X. Calmet and S. K. Majee, Physics Letters B, Vol. 267, 2009, pp. 267-269. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2009.07.049

- G. R. Farrar and R. A. Rosen, Physical Review Letters, Vol. 98, 2007, Article ID: 171302. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.171302

- L. Ackerman, M. R. Buckley, S. M. Carroll and M. Kamionkowski, Physical Review D, 2009, Article ID: 023519. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.79.023519

- P. W. Anderson, Science, Vol. 177, 1972, pp. 393-396. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.177.4047.393

- J. P. Terletsky, Annales de la Fondation Louis de Broglie, Vol. 1, 1990.

- G. E. Marsh, “Negative Energies and Field Theory,” 2008. http://arxiv.org/abs/0809.1877

- A. Linde, Physics Letters B, Vol. 272, 1988, pp. 272-274. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(88)90770-8

- K. Hashimoto and J. E. Wang, “Imaginary Sources: Completeness Conjecture and Charges,” 2005. http://arxiv.org/abs/hep-th/0510217

- V. N. Lukash and E. V. Mikhheva, “Physical Cosmology,” Fizmatgiz, Moscow, 2010. (in Russian)

- J. L. Feng, Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Vol. 48, 2010, pp. 495-545. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-astro-082708-101659

- B. C. Kelly, M. Vestergaard, X. Fan, P. Hopkins, L. Hernquist and A. Siemiginowska, The Astrophysical Journal, Vol. 719, 2010, p. 1315.

- N. Kaloper and A. Padilla, Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics, Vol. 2009, 2009, p. 023. http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/1475-7516/2009/10/023

- G. F. R. Ellis, R. Maartens and M. A. H. MacCallum, “Relativistic Cosmology,” Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139014403

- S. M. Carroll, M. Hoffman and M. Trodden, Physical Review D, Vol. 68, 2003, Article ID: 013543. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.68.023509