Creative Education

Vol.09 No.10(2018), Article ID:87005,46 pages

10.4236/ce.2018.910115

The Education of History Teachers in Europe―A Comparative Study. First Results of the “Civic and History Education Study”

Alois Ecker1,2

1University of Graz, Graz, Austria

2University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

Copyright © 2018 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: August 2, 2018; Accepted: August 27, 2018; Published: August 30, 2018

ABSTRACT

The “Civic and History Education Study” is the first comprehensive study in Europe to describe and analyse the formation of school teachers of the historio-political subjects. Based on a systemic and organizational approach, between 2010 and 2013 more than 46 institutions of 33 countries in the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) have been investigated and compared on the existing full study programs in initial teacher education for school subjects “History”, “Civic/Citizenship Education”, “Politics”, “Social Studies” and “Cultural Studies”. The nature and quality of the education and training that teachers of these subjects receive seems crucial for reflecting the social and political developments of life in multicultural and diverse societies. History teachers and teachers of “Social Studies” or “Civic Education” are expected to contribute substantially to the formation of the socio-political identity of the future citizens of Europe. The pupils’ competences for democratic citizenship, intercultural dialogue, mutual understanding and tolerance are expected to be developed during secondary school education. The central question of the project-group therefore was: Are the teacher education programs conceptualized to provide the trainee teachers with the requested knowledge and skills for acting as these responsible educators of the future European citizens? This paper describes the structures of initial teacher education for the concerned subjects in the European countries: It gives information on the various types of teacher education institutions, the architecture of teacher training programs, the models of training, the length of studies, the relation between subject oriented and professional training, the forms of induction and the multifaceted forms of tutoring and mentoring. In the main part of the paper, crucial qualitative aspects in the formation of the historio-political competences of teacher trainees will be introduced and compared. An analysis of the aims, the theoretical basement, the content as well as the pedagogical/didactical concepts of curricula will be given, and relevant aspects of the formation of methodological and didactical competences of teacher trainees by academic and professional training will be compared and analyzed. Special emphasis will be given to the formation of their communicative and cooperative skills and the formation of media literacy.

Keywords:

Teacher Education, Initial Teacher Training, History Teachers, Historio-Political Education, Citizenship Education, Social Studies, Historical Consciousness, Historical Culture, Didactics of History

1. Introduction

In 2003 the first pilot study on “Structures and Standards of Initial Training for History Teachers in 13 member states of the Council of Europe” had been published (Ecker, 2003) . It was the first study on a European level for subject “History” to give an insight into the institutional framework, the basic models and the various organizational and didactical aspects of the initial education for history teachers.

Building on this first study, the research-network on Civic and History Education (=the CHE-network) has produced another regional study on the initial training for history teachers in South East Europe (Ecker, 2004) . A second general survey, including more than 20 countries of all parts of Europe, has been elaborated in the framework of an EU-Socrates program in the years 2003 to 2006. The electronic versions of these former studies are still available on the web-portal of the CHE-project1.

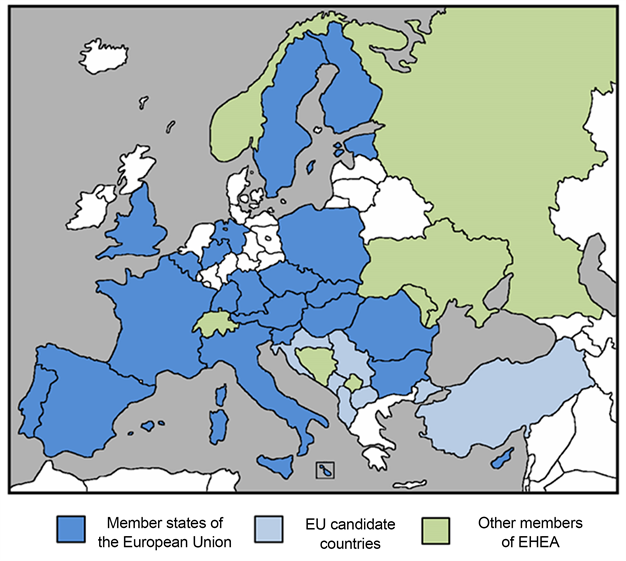

The actual study on teacher education for school subjects in the field of Civic and History Education, the CHE Study (CHE, 2012) , was undertaken in the years 2010 to 2013. The CHE-Study includes 33 countries of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA). It covers almost all the member states and candidate countries of the European Union, it includes the majority of countries of East and South East Europe2, other countries of the EHEA such as Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Kosovo, Moldova, Norway or Switzerland, and it includes the largest countries in the European Higher Education Area, i.e. the Russian Federation, Ukraine and Turkey (see Chart 1).

2. Research Strategy, Organization and Methodology of the CHE-Study

2.1. Research Strategy

The research strategy of the CHE-Study has been oriented on recent systemic

Chart 1. The 33 European countries as represented in the CHE-Study.

and organizational approaches to the educational system (Argyris & Schön, 1996; Ecker, 1997a, 1997b; Willke, 2004; Senge, 2006; Simon, 2009) . Teacher education in the systemic sense is understood as a self-referential social system which is constituted by specific “processes of communication” between all agents involved (Luhmann, 1984: pp. 191-241) . Having this theoretical approach in mind, the focus of interest in our research on teacher education was given to the organizational and communicative structures of teacher education, as well as to the normative regulation of such education, i.e. the teacher education programs, the curricula the legal framework and the governance of teacher education. Psychological perspectives on the individual learner/student or the individual teacher/teacher trainer have not been investigated in the course of this study.

With its central function of organizing the qualification and personal development of (subject) teachers, the teacher education system is neither a pure scientific system nor is it a pure educational system. The social system of teacher education can be regarded as an intersectoral system, situated between the world of science (university) and the world of education (school). While “university” represents the system of research and scientific production, “school” represents the system of education, qualification and allocation. To function adequately and produce sense, teacher education has to be organized and steered in its own rights and logics (Ecker, 2018: p. 7) . It requests communication processes on the level of institutional structures and organizational development, on the level of knowledge production and knowledge management, and on the level of qualification and personal development, e.g. the development of subject oriented, methodological, pedagogical and social competences of the trainee teachers (Ecker, 2018: p. 2) .

Consequently, when organizing research on (the quality of) teacher education of the CHE-subjects, it seemed favorable to the project group to observe all three levels of communications:

1) The institutional structures and the organizational development,

2) The qualification of teachers and the personal development,

3) The knowledge production and the knowledge management.

When developing the questionnaire for the CHE-Study, we therefore asked questions on all three levels: We investigated the central institutional structures and the forms of organization and cooperation between the institutions involved in teacher education programs, we had a look on the professional profiles of teachers and on the training of key-competences of the subject teachers under discussion, and we analyzed the content and the methodology as prescribed in the curricula.

2.1.1. The Institutional and Organizational Context: Aims of the CHE-Study in the Context of the European Educational Systems

When asking about teacher education in Europe, a researcher will quickly detect the plurality of concepts and structures of the educational system(s). Since the late 18th century, as a consequence of the nation building process in Europe, the educational systems in general, and the legal framework for teacher education in particular, are based upon national decisions and guidelines. This situation has not changed in the two decades of the 21st century: There are no consistent, consolidated standards in teacher education for the European countries in general.

The findings are relevant within the framework of the European Union, where there exist no binding regulations for the educational systems of the member states, but are equally relevant for those European countries, which are not members of the European Union, e.g. Albania, Croatia, Norway, the Russian Federation, Serbia, Switzerland, Turkey or Ukraine: The educational standards of these countries rest upon national structures and organization as well.

Related to the focus of interest of our study, there are neither common standards for teacher education as regards subjects such as “History”, “Social Studies”, “Civic Education” or similar subjects, nor are there guidelines or standardized instruments for the exchange of information or the adjustment of educational policies on teacher education of the CHE-subjects on a European level. A comparative study of the structures and standards of teacher education in History, Social Studies and Citizenship Education in Europe, therefore, seemed to be of high relevance.

Certainly, in a more general perspective, for example as a motto of the European Union, there is a broad consensus among politicians, businessmen and educators in Europe saying that the cultural identity of Europe forms “a unity which is based on its diversity”. This motto of the European Union could be interpreted in the sense of the plurality of national cultures being interwoven by transnational strategies and networks of cultural cooperation and dialogue (Trichet, 2009) . Consequently, although there is no consolidated legacy on (secondary school) education in Europe, ―and despite all political and ideological differences and traditions between East and West, left and right―, there are common ideas as concerns the goals of such education: The agreed cultural consensus―building the framework for all measures of cultural and educational work, being detectable in the general guidelines of school curricula and/or the study programs at universities all over Europe―refers to the values of democracy, human rights, the rule of law, freedom, equality, solidarity and tolerance.

In the field of history teaching, manifold examples can be given for such forms of cultural cooperation and the sharing of common values: There is a longstanding exchange of information between the European countries on the level of ministers of education as well as on the level of policy makers, teacher trainers and teachers. An important part of these discussions has been monitored by the biggest intergovernmental organization of Europe, the Council of Europe. Almost since its foundation in May 1949, more precisely since the declaration of the European Cultural Convention in 1954 (Council of Europe, 1954) , history teaching has been an important topic on the agenda of the Council of Europe (Council of Europe, 1994; Council of Europe, 1995) . After the decline of the communist regimes in Eastern Europe in the late 1980ies, the revision of textbooks, the reform of curricula and the education of history teachers had got renewed interest in the framework of the Council of Europe’s work on history teaching and on citizenship education. The new developments have been discussed in a series of symposia and conferences during the last three decades. As a result, several recommendations to the ministers of education, such as “Recommendation Rec (2001) 15 to member states on history teaching in twenty-first-century Europe” (Council of Europe CM, 2001) or the Council of Europe’s “Charter on Education for Democratic Citizenship and Human Rights Education” (Council of Europe CM, 2010) have been elaborated and are widely promoted among the 47 member states of the Council of Europe.

Parallel to this process, in the framework of the European Union, since the beginning of the 21st century, the European Commission, the European Council and the European Parliament have stressed the importance of teacher education. This led to a number of relevant communications and guidelines for teacher education in the European Union (European Commission, 2007; European Commission, 2009; European Commission, 2017) .

On the level of tertiary education, since more than two decades, there is a growing interest in comparing the different structures of the educational systems on a European level. A leading role in this process can be attributed to the ‘Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA) of the European Commission, including the European database on education, Eurydice (Eurydice, 2012; European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2017a) , as one of its programs. The inception of the Bologna-Process in 1999 lead to a more comparable, compatible and coherent system of higher education in Europe and targeted in the establishment of the European Higher Education Area (March 2010, Budapest-Vienna-Declaration) (Eurydice, 2018) 3.

With the establishment and the organization of the European Higher Education Area, the teacher education, being mainly an issue of tertiary education today (see below), has become a topic of European comparative research (Menter & Murray, 2011; Phillips & Schweisfurth, 2014: pp. 38, 55-56) . Already, as shown by the references above, it is a key topic of investigation and reflection within the frameworks of education policy makers of the European Union and of the Council of Europe. It plays a permanent role on the level of intergovernmental consultancy and of intergovernmental recommendations, and it has strong options to become a topic on the level of European guidelines and regulations.

2.1.2. Qualification of Teachers and Personal Development

Over the past two decades, recommendations of international educational institutions stressed the importance of competence-oriented education and training for subject teachers. Competence-oriented education should enable the future teachers to work adequately and efficiently in the situation of increasing diversity of pupils and students, and to handle teaching and learning flexible, e.g. up to the needs of a socially divers and multicultural learning group.

Subjects such as history and civic education are expected to play a significant role today in forming the socio-political identity of the future citizens of Europe. In public view teachers of these subjects are expected to develop pupils’ social and communicative competences for democratic citizenship, intercultural dialogue, mutual understanding and tolerance. The nature and quality of the education and training that teachers of these subjects receive, therefore, seems crucial.

Taken schools as key institutions to develop historical consciousness and historical culture of the young generation, ―and targeting values such as democratic interaction, intercultural dialogue and social responsibility as basic references of such education, ―the project group wanted to know, what kind of historical culture was supported by the actual teacher education programs in the different places and institutions all over Europe, and what concepts of historical consciousness and civic/citizenship education the future teachers were educated for?

The questionnaire about the architecture of the teacher education programs in the various training institutions therefore asked about the conception of the professional profile of the subject teachers (Ecker, 1999) , whether and how they were formulated in the general guidelines of a concrete curriculum. Furthermore, for the analysis of the aims, the content and the methodology in the various teacher education programs, the questions in this part focused on subject oriented competences and on key-competences of the historio-political education of the CHE-teachers. These competences have been formulated in the discourse of history didactics in the first decade of the 21st century (Pandel, 2006: pp. 24-52) , and, in parallel, were identified and written down by policy makers of the relevant educational networks in Europe, e.g. by the Council of Europe’s history education unit, in recommendation Rec CM (2001) 15 on History Teaching (Council of Europe, 2001) , and recommendation Rec CM (2010) 7 on Education for Democratic Citizenship and Human Rights Education (Council of Europe, 2010) .

2.1.3. Knowledge Management of the Subject(s): The Changing Role of School Subject “History” and “Civic Education” in the Era of “Accelerated Cultural Change”

The more recent debates on history teaching and learning have made explicit that democratic societies are in dire need of new forms of historical thinking and learning (Cajani & Ross, 2007; Stradling & Row, 2009; Davies, 2012) : Forms which are no longer exclusively legitimizing the political and/or cultural tradition of the nation state at hand; forms, which provide techniques and strategies for developing “historical learning” (Stearns, Seixas & Wineburg, 2000; Rüsen 2005) , “historical consciousness” (Seixas, 2004; Straub, 2005) and “historical thinking” (Seixas, 2017) ; forms which make the historical information comparable, analyzable and interpretable in transnational and global perspectives, and, by doing so, transgress the borders of national history and positivist approaches to the past (Taylor & Guyver, 2012; Berger, 2017) .

From this perspective, the school subject “history” is regarded today not only as a subject to give understanding and orientation as concerns the various productions of historical narratives, but more than that, as a school subject to give understanding and orientation in today’s societies, e.g. by supporting the development of competences for acting and reflecting adequately to the process of accelerated cultural change (Ecker, 1997a) . In this sense the subject “history teaching” has been described by scholars of history didactics to contribute to the “historical consciousness” (Stearns, Seixas & Wineburg, 2000; Seixas, 2004; Rüsen, 2005; Straub, 2005; Lukacs, 2009) and to “historical thinking” (Seixas, Morton, Colyer & Fornazzari, 2013; Seixas, 2017) on different levels:

1) the reflection of the individual person and his/her own self-development,

2) the communicative processes and the negotiations on historical narratives in the here and now of the history classroom or the university course, and on

3) the level of collective reflection of political, economic, social or cultural developments in public historical debates, performances and publications, i.e. the “historical culture(s)” of societies.

By such transnational, sociologically based historical analysis and comparison, the new concepts of history teaching aim at contributing to the development of a historical literacy which is interconnected to social, economic and political literacy, analytical and critical thinking as well as to intercultural understanding and social responsibility.

All international educational organizations agree widely on this new concept of history education and teaching, which is closely related to key-aspects of Citizenship Education, Human Rights Education (Stevick & Levinson, 2007; Stradling & Rowe, 2009; Council of Europe CM, 2010) , of transnational, intercultural and creative education (Giglio, 2015; McIntyre, Fulton & Paton, 2016; Paulus, van der Zee & Kenworthy, 2016; Wegener, Meier & Maslo, 2018; Peeren, Celikates, de Kloet & Poell, 2018; Saint-Laurent, Obradović & Carriere, 2018) .

2.2. Organization of the Project

The research in the CHE-project had been organized in the framework of a three years’ EU Life-Long-Learning project and co-financed by a second project supported by the Austrian ERSTE Foundation in the years 2010 to 2013. More than 46 institutions from 33 countries of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) have been investigated in-depth on the existing full study programs of initial teacher education for the school subjects “History”, “Civic/Citizenship Education”, “Politics”, “Social Studies” and “Cultural Studies”. The data compared in the overall research refer to study year 2009/10.

Both projects have been coordinated by the University of Vienna, Austria, Department for Didactics of History, Social Studies and Civic Education with the author as project-coordinator. The study could only be realized with the collaboration and support of a large number of dedicated colleagues, experts in history didactics and educational research all over Europe. The detailed list of partners and experts contributing to this study is published on the web-portal of the CHE-Study4. My sincere thanks go to all of them: for their energy, for their expertise, for their patience and for their accuracy in collecting and correcting the data in the individual countries.

The main European Association of Teacher Educators, Euroclio5, and the International Institute of Textbook Research, the Georg-Eckert-Institute, were involved in the CHE-study as project partners. Their knowledge about teacher education institutions in Europe and their longstanding experience helped us to create the research network and to conceptualize the structure of comparative research.

The Council of Europe’s History Education Unit was involved in the CHE-project as a counseling partner. This gave us the opportunity, in the phase of dissemination of draft results, to present and discuss the main results of the CHE-Study at the Annual Conference of The Steering Committee for Educational Policy and Practice (CDPPE)6 in February 2013. The results presented in this article have thus been discussed, reflected and committed in the following months at the level of educational policy by all the 47 member states of the Council of Europe. The findings of the CHE-Study will be subject of further discussion in the Council of Europe’s new project on “Educating for Diversity and Democracy: teaching history in contemporary Europe”.

2.3. Central Research Questions of the CHE-Study

Taken the changing role of subjects “History”, “Social Studies” and “Civic Education” as new challenges for teacher education, the central questions of this project have been formulated as follows:

1) Are the teacher education programs in the participating training institutions conceptualized to provide the trainee teachers of the relevant historio-political subjects with the necessary knowledge and skills for acting as responsible educators of the future European and global citizens?

2) What kind of historical culture was supported by the actual teacher education programs in the different places and institutions all over Europe, and what concepts of historical consciousness and of civic education the future teachers were educated for?

Having in mind the aims and the educational context as describe in chapter 2.1 above, the CHE-project group agreed to

1) compare the structures, standards and tenets of the full study programs in initial teacher education for those subjects, which are expected to develop the historical and socio-political identity of the future citizens of Europe, i.e. school subjects “History”, “Civic/Citizenship Education”, “Politics”, “Social Studies” and “Cultural Studies”7;

2) investigate the teacher training curricula in-depth, including the concepts, the goals, the content and the methodology of the teachers’ education, the forms of assessment, the practical training and the tutorial systems;

3) identify similarities and differences between the structures and the various programs of teacher education;

4) ask for changes in the organization of initial teacher education since the implementation of the Bologna-Process.

2.4. Methodology

The research of the CHE-Study was based on a threefold approach:

In the first phase of the underlying research a detailed questionnaire had been developed by the Vienna based research team. The questionnaire had then been answered by educational researchers of each partner institution. It covered various sets of questions regarding

1) the institutional structures of teacher education,

2) the models of teacher training,

3) the legal framework of full study programs,

4) the aims as written down in the curricula as well as through guidelines and conceptual papers or comments to the curricula,

5) the content of the curricula (including the content of subject oriented courses, subject didactic courses and courses of general didactics),

6) the “didactic concepts” (i.e. the pedagogy and the methodology) of the professional training,

7) the forms of assessment,

8) the forms of practical training,

9) the tutorial systems, and

10) the forms of induction, i.e. the introduction to the professional teaching at school.

In a second phase, the results of the individual investigation on 46 teacher education institutions in the 33 countries were collected by the Vienna based research team, who developed a draft version of the comparative study. The draft results were then discussed at two general expert meetings and further fine-tuned by additional investigation and cross-checking of data and results.

Parallel to this investigation against the standardized questionnaire, and parallel to the development of the comparative study, four thematic groups were working on crucial aspects of initial teacher education such as “the interdisciplinary relationship between history and citizenship”, “the professional education of the teacher trainees”, “the education and training of media literacy” and “the training for dealing with conflict resolution and conflict management”. Reports from the working groups will be published in the final version of the comparative study.

First results of the CHE-Study are now available on the web-portal of the project (CHE, 2012) , the full study is published by the Council of Europe.

Specifications of Comparison

To get a clearer focus of comparison (Engeli & Rothmayr Allison, 2014; Marschall, 2014) , this paper will mainly discuss results of the initial education of trainee teachers for subject “History”.

It should be underlined furthermore for this survey, that the focus of our investigation was on “full study programs” of initial teacher education. It would be worth to explore the broader field of post-graduate courses and special courses of continuous professional development (CPD) to conclude the picture. However, such questions would have exceeded the capacity of this project.

Another specification has to be mentioned as concerns the comparison of data on the national level: Being aware of the complexity of educational processes, the project group found no scientific value in identifying or defining “the best” teacher education program among the European countries. Thus, in clear contrast to other international comparative studies, e.g. the PISA-Studies, the project group had no interest in establishing a structure of “competition” between the educational systems of the different countries: The focus of interest of the CHE-Study is given to the quality and the functionality of teacher education programs (Menter & Murray, 2011; Sharpes, 2016) . The attention in comparison, therefore, was given to thematic aspects such as concepts, theoretical basement, content and methodology of teacher training courses. Taking into account the big variety of teacher education programs, even in the scope of one subject (see below), we produced comparative surveys on the level of countries only to show the basic organizational structures of teacher education programs. Otherwise, and for all qualitative questions, we produced thematic comparative surveys (e.g. Figure 2, Figures 8-16, Figures 19-21 , Figures 24-26) or surveys on the level of institutions (e.g. Figure 3, Figure 7, Figure 17, Figure 18, Figure 22, Figure 23).

In some European countries, such as Belgium, Germany or the UK, the legal framework of the educational system depends on the regional government or the Federal Land (Bundesland). Correspondingly, the teacher education structures may vary between the federal lands which makes it still more difficult to produce a central survey of the country. For these cases, we decided not to produce a (national) country survey, but to focus on the data of selected federal lands: For example for Belgium we have studied only teacher education programs of the Flemish community, for Germany we have studied the teacher training programs only of four of the 16 federal lands of Germany: Bavaria (DE-BY), Baden-Württemberg (DE-BW), Lower Saxony (DE-NI) and North Rhine-Westphalia (DE-NW), and for the UK we have studied only the teacher education programs of selected institutions in England and Wales.

On the institutional level, for all the study courses, the researchers of the individual study programs were asked, to give a general description of the architecture of the study program, including the aims, the professional profile and the theoretical basement of curriculum structures. For the classification of courses, we followed the general differentiation of most teacher education curricula, who discern between subject courses, subject didactic courses, courses of general didactics, and courses of practical training. In addition, to get a clearer picture of the goals, the content and the methodology of the individual courses, the researchers were asked to give detailed information on the content and the structure of courses in open text boxes.

Furthermore, when researchers wanted to point out a concrete problem of classification, they were asked to describe the case as “note” in an open text box. The research team working on the comparative structure had to decide then to either make an individual specification or to propose the case as a topic of discussion at the next expert meeting.

Final specification: When comparing thematic aspects, as prescribed in the respective curricula, we asked the researcher of an individual institution to indicate the extension of realization of such thematic aspects in the concerned courses. For example: When asking for conceptual aspects of “historical consciousness” in subject history courses, we offered a metric scale in the questionnaire to indicate whether such aspects in the conception of a concrete program were either “extremely important (in use in more than 75% of courses)”, “very important (in use in more than 50% of courses)”, “important (in use in between 30% and 50% of courses)”, “not important (in use in between 10% and 30% of courses”, “hardly used (in use in less than 10% of courses)” or “not used at all”. Similar, when asking for the concrete realization of a thematic topic or a methodological aspect in training courses, we asked, to which extent such topics/aspects were trained explicitly and to which extent. The metric scale, in such cases, was: “Extremely often trained (in more than 75% of courses)”, “very often trained (in more than 50% of courses)”, “trained in a significant number of courses (in between 30% and 50% of courses)”, “not so often trained (in between 10% and 30% of courses)”, “hardly trained (in less than 10% of courses”, and “not trained”.

This paper presents a first selection of results about the organization, the personal development and the knowledge management of initial teacher education programs with the emphasis given to the education of history teachers.

3. Results

3.1 The Organization of Initial Teacher Education of the CHE-Subjects in Comparison with General Trends of Teacher Education in Europe

1) The Demographic Turn in the teachers’ profession

When looking at the actual age distribution among secondary school teachers in Europe, we observe a relatively big number of older teachers. As can be seen from the figure below, around 20% of the teachers are going to retire within the next three to four years and, more significant, another 30% - 35% will retire within the following years. In sum, and this is a general trend for lower and upper secondary teachers in Europe, more than 50% of the teachers are going to retire within the next 7 to 10 years. We can even talk of a “demographic turn” as concerns the generation of teachers in secondary schools. The general situation of age distribution of the secondary school teachers in Europe, as compiled by Eurydice (2012: p. 124) has been checked for our sample in the course of project investigations and is also applicable to the secondary school teachers of the CHE-subjects (see Figure 1).

On the organizational level, the demographic turn in the teachers’ cohort is a challenge for educational planners, for teacher training institutions and for school administration as well.

But the substitution of more than a generation of teachers will not only represent a demographic change in the cohort of secondary school teachers, it will also mark a social challenge and a risk as concerns the culture of teaching and learning in the CHE-subjects.

Key questions to address include the following: Who will be the new teachers? What is their political, cultural and social background?

Figure 1. Distribution of teachers in secondary schools by age group, general (lower and upper) secondary education (ISCED 2 and 3), public and private sector combined, year 2009/10.

In addition, curriculum planners and teacher trainers of the CHE-subjects are encouraged to ask questions regarding the content of teacher training, like: What history will they teach? What values will they live by? What ideas will these new teachers have about teaching history and civic education to the pupils in their classrooms? What conceptions of teaching history/and or civic education should students experience in their training?

Teacher trainers may also ask questions regarding the necessary didactic and methodological skills of the next generation of history teachers: What didactic and methodological training will they need? What can be done by teacher training to make the new generation of history teachers enough self-confident and self-reflective to enable them to observe and organize the history classroom as a multi-perspective discourse?

2) The CHE-teacher: An academic profession―trained in a big variety of forms and concepts

Considering the institutional framework, in all the European countries since the 1980ies, a general shift could be observed in teacher education from the secondary to the tertiary sector of education. Initial teacher education of the CHE-teachers has been widely established at academic institutions such as universities or pedagogical universities. This is the case not only for upper secondary teachers, but also for nurseries, for teachers of primary and of lower secondary education.

This trend is reflected in Figure 2, which was produced with the actual study and lists all institutions of the 33 countries which were included in our general survey. A majority of trainee teachers of today study at universities, pedagogical universities or universities of applied sciences.

In addition, in a growing number of cases, there exist institutional links in form of contracts or partnerships between the universities as the leading organization and secondary schools, which offer opportunities for practical training and/or induction. These forms of cooperation between the universities and the partner schools have a strong impact on the quality of teacher education.

Figure 2. Number and type of teacher training institutions in the CHE-Study, year 2009/2010.

3) Organization of studies: Models of training

As concerns the models of training, the European databank on education, Eurydice, distinguishes between two main models of initial teacher education: the consecutive model and the concurrent model: “In the consecutive model, students who have undertaken tertiary education in a particular field, then move on to professional training in a separate phase. In the concurrent model, students are involved in specific teacher education right from the start of their studies, whereas in the consecutive model this occurs after their degree” (Eurydice 2009: p. 149) .

When comparing these models for the situation of history teacher education in the pilot study, we asserted that the concurrent model normally prevailed in institutions which prepare trainees for teaching at lower secondary school, while the consecutive model was dominant in institutions which prepare trainees for teaching at lower and upper secondary level. A brief look at the regional distribution of the two types of training showed a predominance of the consecutive model in Western and Southern European countries, while the concurrent model was more common in Central and Eastern European countries (Ecker, 2003: p. 33) . However, during the past decade, we noticed a bigger plurality of the two models to be established at different teacher training institutions even in one country (see Chart 2).

While in the idea of the consecutive and the concurrent model the study program had a clear local focus, more and more study programs are offered today in modularized form with an option to more mobility, to e.g. study at different universities in Europe, and to finish part of the teacher training studies, one, two, three modules at one place, and complete the other modules at another university. As we can show in the actual study of 2010, this trend continued. We got information about such modular models e.g. from the Flemish part of Belgium, the Czech Republic, Germany (BW and NI), Sweden or Ukraine. These models of teacher education were organized in the individual countries in a big variety of forms, and different models could be offered within a country or even within an institution, e.g. at different faculties.

Chart 2. Models of teacher education in Europe, CHE-Study, 2009/10.

4) Length of teacher education studies, Graduation

As concerns the length of studies, changes are visible mainly for primary and lower secondary teachers. Over the past decades, there is a trend for teacher education of primary and lower secondary education to adapt to the academic level. This trend goes hand in hand with the study programs for these levels to become longer. The implementation of the Bologna-process contributed to a certain extent to a harmonization in the length of studies but the changes were not that big.

Under the Bologna process teacher education is now organized in many countries at BA and MA levels. Today, trainee teachers for primary and lower secondary school level finish their university studies at BA-level with an average length of studies including the induction phase of 3 to 4 years, while those for (lower and) upper secondary level finish their university studies at MA-level with an average length of studies including the induction phase of 4 to 5 years. In some countries like Austria, Germany/BW or Switzerland, studies last even longer (see Figure 3).

The overall length of studies is equivalent for the concurrent model as well as for the consecutive model, although the focus of professional training is at different stages of the study program.

5) Percentage of professional training per certification for school level

Following the Eurydice survey (Eurydice, 2009: pp. 153-155) , we also asked for the minimum time devoted to professional training. The answers given to this question in the CHE study quoted an average of around 20% of the study time that

Figure 3. Length of teacher training studies for primary, lower and upper secondary teachers (ISCED 1, 2, 3), year 2009/10.

was given to professional training. Taken from another perspective this means that around 80% of the study time are given to academic/subject oriented training.

When comparing these figures between teachers of primary, of lower secondary and of upper secondary teachers, the following trend can be observed: On average, more time is devoted to professional and practical training at institutions, where trainee teachers are educated for primary and lower secondary schools, while there is less time given to professional training for trainee teachers of upper secondary schools.

6) The phase of induction

More emphasis was given within the past years to include and/or to add a phase of induction in the last part of initial teacher education. This phase of induction usually encompasses one or several of the following elements: orientation to the workplace, mentoring and guidance through the early months of the individual teaching practice, familiarization with the legal framework of the teacher’s job.

Concerning the forms of induction, again, the picture was relatively heterogeneous. The induction phase may either be integrated as a form of “practical training on the job” during BA-studies (Macedonia, Kosovo, Serbia) or MA-studies (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Czech Republic, France, Hungary, Portugal), or after graduation from MA-studies at university (Austria, Estonia, Germany, Hungary. Italy, Ukraine). The induction may be conducted by teacher training institutes (Estonia, Germany, Hungary, Italy and Ukraine)―sometimes even though the universities were the leading institution during BA/MA studies―and/or the induction phase takes place at partnership schools with the universities remaining in the leading role as scientifically conducting institution (Austria, Czech Republic, GE/BY, Croatia, Hungary, Montenegro, Slovenia, UK/EW, Ukraine). Mentor teachers frequently play a leading role during induction phase.

The picture that we have collected on the actual situation of induction in the CHE-subjects is shown in Figure 4.

The induction phase may last for a period up to 6 months (Czech Republic, Hungary), up to a year (Austria, Croatia, Macedonia, Portugal, Serbia, Slovenia, Turkey, United Kingdom/EW) up to 18 months (Germany/NI, Germany/BW, France) or 2 years (Germany/BY, Germany/NR).

7) Tutoring and Mentoring

Tutoring by a mentor teacher is common with almost all teacher educations forms and countries. As can be seen from Figure 5, to work with a mentor during practical training in schools is a familiar form of education and/or instruction in all the countries involved:

It might be more surprising that also relatively new forms of self-organization and self-reflection in the learning process, like portfolio tasks, are well established in more than half of our sample of the 33 countries. Portfolios as a comprehensive tool of organizing the learning process, e.g. as a form which is recommended or even described as obligatory in the study program, are established in Austria, Bulgaria, Switzerland, Finland, Moldova, Malta, Slovenia and UK/EW.

Growing attention is also given to forms of supervised work with a learning management system or an electronic learning platform. In such cases, not only the teacher trainers but also senior students play a certain role as mentors in the learning process. Forms of eLearning by a learning platform are well established

Figure 4. Forms and structures of induction to get a teaching permission in the CHE-subjects, study year 2009/10.

Figure 5. Institutionalized forms of tutoring and mentoring during initial teacher education in the CHE-subjects, study year 2009/10.

in some of the countries, such as Austria, Belgium-NL, Bulgaria, Switzerland, Germany (BW, NI), Finland, Norway, the Russian Federation and UK/W.

Forms of tutorial and/or mentoring are more established with teacher education in courses of subject didactics (methodology) and with practical training. They are less common with subject oriented courses, especially at university level.

Three forms of tutoring and mentoring, as described above, seem to be relatively common in teacher education at the European level: a) various types of mentorship in practical teacher training, b) the work with portfolio, and c) the supervision with the support of a learning platform.

Other forms of tutoring and mentoring may only be practiced in one or the other institution. This is the case with tutoring by peers in collaborative learning groups, a form which is known with teacher education in Austria, Bulgaria, DE/NI, Estonia, the Russian Federation, Slovenia, Ukraine and the UK/EW.

Monitoring systems as another form of supervision are established in Albania, Bulgaria, Estonia, Moldova, Malta, Slovenia and the UK/EW.

3.1.1. The Organization of full Study Programs of Initial Teacher Education in the CHE-Subjects in Europe

As described in the introduction, despite the formal harmonization in the course of the Bologna-Process there is a big variety in the organization of teacher education programs in the European countries. However, looking on the overall picture, we can identify some common characteristics and trends in the actual development and organization of teacher education. To get a clearer focus of comparison, this paper will mainly discuss results of the initial education of trainee teachers for subject history.

Starting from the late 1960ies and enforced in the 1980ies and the 1990ies, in some European countries, like in Austria, Hungary, the Netherlands or Norway, “History” as a school subject had been transformed into an integrative subject, (“History and Social studies”, “History and Civics”, “Social studies”) including not only the “classical” historical narratives (national history, world history) but also the topics of the Historical Social Sciences (social history, economic history) and/or the topics of Political Sciences (the history of political systems, of state systems, of systems of law, of jurisprudence) (Ecker, 2003: p. 54) . The conception of these new school subjects in the concerned countries was then partly reflected in the teacher training programs, in the form to dedicate a few courses within the “history teacher education”-curriculum to topics of “social studies” or of “civic education”.

From our previous studies of 1998/9 and 2003/4 we knew that in most European countries there were no separate full study programs for Civic Education in the individual European countries. Students had to study “History” or “History Teaching” to be certified as a teacher for “History” in (primary and/or) secondary schools. As a specification for primary schools, it is to note, that subject “History” in most European countries is not taught as a single subject but in an umbrella with topics of geography, social studies and life skills. Consequently there are no full study programs to be certified as a history teacher for primary schools in the European countries.

In most cases, with the certification for subject “History” the newly graduates also got the permission to teach school subjects related to “History”, such as “Civic education”, “Social Studies” or “Politics”. Certainly, already since the early 1990ies, there were post-graduate programs and comparable academic courses to acquire additional certifications in Civic education, Citizenship education and Political studies. But the basic training to become a teacher for subject “history” and subject Civic Education was by teacher education studies of “History (teaching)”.

Since we started our investigation on initial training of history teachers in 1998, a clear trend towards professionalization of teacher education was to be observed: While in 1998 teacher education studies in many cases were still part of a regular “History”-studies program and were rarely organized as full study programs, the latter was already the trend in 2003, when we organized the broader European survey on initial teacher training (ITT) for history teachers: Since about this time, at those institutions where teacher education was organized following the concurrent model (see below), trainee teachers had to decide at the beginning of their studies whether they wanted to become “history teachers” or whether they wanted to start studies to become a “historian”, a researcher, an archivist or a similar expert in historiography.

When conceptualizing investigation for this study, we expected the field of teacher education in the CHE subjects to expand towards “Civic education” or to similar studies in the field like “Social studies”, “Cultural studies” or “Politics” (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2017b) . However, this tendency was not confirmed for “full study programs” of teacher education: As shown in the country overview below, in most European countries the focus is still given to subject “History” as the major subject in teacher education: In the year 2010, to be certified as a teacher for the CHE-subjects, the picture as illustrated in Figure 6 was as follows:

1) In all 33 countries of our sample there existed full study programs for initial teacher education, which were dedicated either to the single subject “History (Teaching)” or to a combination, where subject “History” was the main subject of teacher education but had to be studied either in a fixed combination with a second subject or in a broader umbrella with other subjects like “Social studies” or “Civic education”.

2) In 20 of the 33 countries, full study programs for “History” (or a combination with “History” as the main subject) were the only full study programs to be certified as a teacher in the CHE-subjects: This was the case with Austria, Bosnia

Figure 6. Full study programs of teacher education with subject X as the major subject, study year 2009/10―European survey.

and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, France, Hungary, Italy, Malta, Montenegro, Poland8, Portugal, Romania, The Russian Federation, Serbia, Slovenia, Spain and Ukraine.

3) In the remaining 13 countries of our sample, beside the full study programs of “History”, there existed additional full study programs to be certified as a teacher in the CHE-studies: There were some countries, which offered stand-alone study programs in “Civic education” or “Citizenship education”, like Albania, Switzerland, Moldova, Kosovo, Slovakia, and the United Kingdom (E/W), some others, which offered stand-alone programs in “Social studies”, like Belgium-NL, the Czech Republic, Germany9, FYROM/Macedonia, Norway, Sweden, Turkey and the United Kingdom (E/W)10 and another two countries which offered full study programs in “Politics”, like Belgium-NL and Germany.

When regarding this sample from the institutional level, we can see that all the institutions involved in our research offered “History” as a major subject in their teacher training programs. The subject “History” was partly offered as a single subject (e.g. in England/UK), partly in a fixed combination with a second or third subject (such as Geography and/or Citizenship education, e.g. in France, Portugal, Spain), partly in a variety of combinations with a second and a third subject (e.g. in Austria, Belgium-NL, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Hungary, Norway, Slovenia, Sweden, Switzerland and many other countries).

3.1.2. Example: The Organizational Framework of Full Study Programs of Subject “History”

There is an on-going debate in teacher education since the 1980ies how to foster the professionalization of history teachers by teacher education. One group of teacher trainers seems to be convinced that teacher education has to start from academic subject training―this group is expected to be closer attached to those institutions which follow the consecutive model. The other group stresses the growing differences between the professional fields of historical research and of history teaching and therefore argue for a more profession-oriented and integrated teacher education as concerns the content/knowledge and methodology of history in the teacher education curriculum. This is the tendency at institutions following the concurrent and the modular model (see above).

When looking more in detail, the variety in the forms of teacher education in the CHE-subjects is much bigger on the European level, than the two models (consecutive-concurrent) or the dichotomy between subject oriented training and professional training might suggest.

Just when looking on the organizational forms in which subject “History” can be studied as illustrated in Figure 7, we discerned

Figure 7. Organizational forms of full study programs of teacher education for subject History in Europe, study year 2009/10.

1) full study programs with subject “history” being studied as a single subject,

2) full study programs with subject “history” in form of a major-minor subject,

3) full study programs with subject “history” in a fixed combination with one other subject (e.g. with geography) or in a fixed combination with two other subjects (civic education, social studies), or

4) full study programs with subject “history” in a variety of combinations with one subject (e.g. language, religious education, mathematics, sports education) or more than one subject.

Varieties on the level of content and methodology are of course still bigger than the organizational dimension of studies we are highlighting with this item. We will show some examples below.

Taking these results on the organizational structures of full study programs of subject “History” and comparing the results from the individual countries on the European level, the data imply that we may not be so sure of what it means to be educated as a “history teacher”: Even though all trainee teachers are formally educated as “history teachers”, this does not mean that they are trained 1) in similar structures, 2) towards similar or comparable goals, and 3) within a comparable framework of content and methodology.

These findings are equally confirmed when looking on the personal development of history teachers, as specified here on the example of the professional profiles of the history teachers:

What has been discussed about the differences in the organizational structures also holds for the Qualification of teachers―as illustrated in the following by the analysis of the professional profiles of subject teachers―and for the content of curricula.

3.2. The Qualification of Teachers and the Personal Development

3.2.1. Examples for Professional Profiles in the Education of History Teachers

When designing a curriculum for teacher education, curriculum planners in Europe today normally start from an ideal professional profile (Ecker, 1999; Cochran-Smith, Feiman-Nemser, McIntyre, & Demers, 2008: pp. 10-65) that should be attained by the students until the end of their studies. Over the past decade study programs for teacher education in the subject “history”, “civic education” and “social studies” have been designed following a competence-oriented concept: For the aims of the study program in general (and for individual modules and/or study courses in particular) the competences to be acquired by the students were elaborated and described in the curricula. Such competence-oriented descriptions of the study programs also exist for the curricula of the CHE-subjects (Popp, Sauer, Demantowsky, & Kenkmann, 2013) and consequently became object of our analysis and comparison.

By comparing the full study program of teacher education for subject “History” on the European level, and by taking the various sets of the envisaged students’ competences as indicators für the distinct conceptions of the ideal history teacher, we came to four different professional profiles of the future history teacher in Europe:

1) The history teacher as a variation of the general profession of a teacher.

2) The scientifically oriented history teacher.

3) The history teacher contributing to the historical culture of the local society.

4) The history teacher as mentor for critical research and analysis of the socio-political environment.

These four different approaches to conceptualize the education of the future history teachers may be found in variations in most of the curricula we have analyzed. We can take them as prototypes for the conceptions at the bottom of the teacher training curricula in the various institutions all over Europe (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2018) :

1) The subject (history) teacher as a variation of the general profession of a teacher

Recent debates on the teacher’s profile have put more emphasis on the general competences of the teacher as a reflective practitioner (Philipps, 2008) , the teacher who is able to steer a learning process and/or the teacher who acts as a professional also outside the classroom, in contact with colleagues, parents and superiors. In such profile, the subject specific profile is regarded to be a relatively small segment of a much broader general professional profile to be developed during teacher education studies.

An example of this profile is given in the 10 general aims for the “History” curriculum at VU Brussels (Belgium-NL): The teacher is expected to function as …

a) a facilitator of learning,

b) an educator,

c) a content expert,

d) an organizer,

e) an innovator and researcher,

f) a partner of parents or caretakers,

g) a member of school team,

h) a partner of external organizations,

i) a member of educational community, and

j) a cultural participant.

All aspects of this profile are of course relevant for a subject teacher. However, the subject specific components get less differentiation than in the three following profiles. The subject specific education and training tends consequently to be subordinated to the more general profile of the teacher as educator, as manager of the classroom activities and as social and cultural worker.

2) The scientifically trained (subject) history teacher

A second type of curricula proposes to educate the trainee history teachers following general academic as well as subject specific principles in leading them towards a scientifically based teaching competence. For example at the university of Tartu (Finland), the description of the professional profile starts from key-competences such as “skills of communication and interaction”, “skills of using ICT in working life”, “skills of being an expert and developer in working life” and suggests to educate these key-competences together with the more specific academic skills (such as “using scientific knowledge and methodologies”), but mainly focus on subject specific skills, which are regarded as being essential for the teaching of history. At the end of their studies, the trainee history teachers therefore should

a) be able to adopt and use broad and deep historical knowledge,

b) have a broad understanding of history as human culture and thinking,

c) have broad understanding of the development of historical thinking and historiography,

d) have broad knowledge of significant theories of historical science, characteristics of historiography, methods etc.,

e) have a deeper understanding of one or more epochs or special themes,

f) have deeper understanding of some methodological approaches relevant to research skills (constructing a study, research process, using information, scientific thinking, implementing, producing and communicating information),

g) be able to follow academic discussion, and

h) dispose on skills in written, oral and digital communication.

Furthermore, teachers educated in the sense of this profile should be able to develop, what is called “The world view of a historian”, i.e.

a) emphasis on values of classical humanism,

b) thinking about the social and ethical dimensions of history,

c) describing the past and present reality and its diversity in a way that can persist critical inquiry,

d) have a critical attitude to knowledge, beliefs and values.

In addition, the subject specific qualifications are required to be related to the pedagogy of teaching in the multicultural classroom, the understanding of pupil’s development and learning, theories and pedagogy of teaching, and, as the main aim, create a basis for the trainee teacher’s own professional development as an expert in teaching history.

In this second conception, the history teacher is attributed the task to present the historical narratives as coherent and integrative factors of human societies; subject history seems to be understood as a program that contributes to the universal culture of human societies.

3) The history teacher as an active developer of historical culture

Curricula at other institutions, like the Russian Academy of Teacher education, Moscow, promote aims in the curriculum, which are similar to profile 2 as far as they concern historical knowledge and methodological skills, but put more emphasis on the performance of the history teacher as an active participant of and as a developer of the historical culture at different levels of society, e.g. the

a) Activities within the scientific community, by e.g. organizing scientific conferences, writing and editing scientific publications,

b) Activities in the educational system, e.g. practical use of and basic knowledge of educational activities; analysis and interpretation of political, socio-cultural, economic and civilizing aspects of historical processes,

c) Activities in school and school administration, e.g. preparation and processing of evaluations, work with databases and information systems,

d) Activities in the local community, e.g. realization of historical, cultural and local history functions in cooperation with local cultural institutions like archives and museums,

e) Activities towards the more general dimensions of society, e.g. working out historical and socio-political aspects in cooperation with analytic centers, public and governmental organizations and with media.

In this third conception the history teacher is attributed an active role in the concrete social and cultural environment, where she/he is expected to work. The history teacher is understood as a person who shares responsibilities not only with the school system where she/he is teaching, but with the community and/or the society she/he is living in.

4) The history teacher as mentor for acquiring knowledge and methodology of socio-political and historical analysis and interpretation

The forth profile integrates aspects of historical literacy as well as literacy of social and political sciences aiming at educating teachers who are able to support the development of self-reflective and socially responsible young citizens. It puts the history teacher in the role of the mentor, who supports the pupils or students in acquiring knowledge and methodology of socio-political and historical analysis and interpretation. Such profile, as proposed e.g. by the University of Applied Sciences, Aarau (CH), promotes an integrative approach to historical learning with a strong emphasis on aspects of Citizenship Education. The main goals for initial teacher education in this curriculum are,

a) To bring up important contents and themes of the regional, national, European and extra-European history in different eras,

b) To acquire historical knowledge (political, economic, social, cultural, environmental and gender aspects),

c) To learn how to find and disclose (critical and appropriate) historical sources and materials, to initiate research on the contexts, to interpret the material and sources and therein identify the historical dimensions of the present,

d) To acquire knowledge on different ethical dimensions of subject history from different points of view such as politics, religions and human rights,

e) To acknowledge and respect the diversity in human existence,

f) To learn how to use basic strategies for participation in the society.

More than many other curricula, this forth type is based explicitly on sociological and educational theories and gives reference to concrete didactic models, so that the trainee teachers can get a sound scientific basement and reflection of their education11.

3.2.2. Examples for the Education and Training of Second-Order Concepts of Historical Thinking and Learning

1) The relevance of “historical consciousness” and “historical culture”

Within the last thirty years the understanding of the school subject “history” has changed quite substantially: Today, most theoretical discussions in history didactics converge in the idea that the main goal of the school subject “history” consists in the development of “historical literacy”, “historical thinking” (Seixas, Morton, Colyer & Fornazzari, 2013; Seixas, 2017) and “historical consciousness” (Seixas, 2004; Rüsen, 2005) of pupils and students.

In daily practice, this shift of paradigm in “history teaching”―from the positivist approach to the past (chronology, “facts and figures”) and it’s clotted forms in school teaching (“teaching to test”) to a sociological understanding of “history teaching”, including qualitative elements of self-reflection and self-organization in the conception of didactics of history (Ecker, 1997a, 1997b) , putting the critical and reflective citizen in the center of an education of “historical literacy”, ―is still under debate.

However, the results of the CHE-study show a relatively broad acceptance of the academic debate on “historical thinking”, “historical consciousness” and “historical culture”. From the majority of institutions we heard about a more or less positive trend towards the new conception of the subject “history”: Following their answers, the trainee teachers of subject “history” receive a relatively clear orientation for the development of “historical consciousness”, “historical thinking” and “historical culture”. When asking in the CHE-Study for these conceptual aspects in subject history courses, whether they were regarded as being “extremely important”, “very important”, “important” or “not so important”, approximately two third of the institutions reported that aspects of “historical consciousness” (Figure 8) were taught explicitly in subject history courses either “extremely often” (=in more than 75% of the courses), or “very often” (=in more than 50% of the courses) or at least “often” (=between 30% and 50% of the courses). We got similar answers for the aspect “historical culture” (Figure 9).

In comparison to the previous study, more emphasis was also given to the training of analytic skills, e.g. by the analysis and comparison of different historical narratives, by construction and de-construction of historical narratives, or by the analysis and comparison of narratives in history textbooks.

2) Concepts of history teaching for living in diverse societies: multicultural, linguistic and gender aspects

As pedagogues in history, we aim at educating historically well informed and trained citizens for today’s and tomorrow’s societies (Stevick & Levinson, 2007; Stradling & Rowe, 2009) . Among other skills, the development of analytic skills can contribute to reduce biased historical interpretation. A history teacher, who will be trained to discern as clearly as possible between evidence of historical sources and ideologically affected interpretations or other narrow, missionary and one-dimensional positions in historical narratives, might contribute to the education of a critical citizen (Cajani & Ross, 2007; Arthur & Cremin, 2012) .

These citizens are expected to be aware of their individual role and position in political and social life, but in addition, they are equally expected to contextualize their individual situation to the historical developments of society and culture in diverse and multicultural dimensions.

As regards such multicultural aspects in history teaching (Figure 10), the

Figure 8. Representation of the concept “historical consciousness” in subject “history” courses of full study programs for history teachers’ education, European survey, study year 2009/10.

Figure 9. Representation of the concept “historical culture” in subject “history” courses of full study programs for history teachers’ education, European survey, study year 2009/10.

Figure 10. The representation of “multicultural aspects” in full study programs of history teachers’ education, European survey, study year 2009/10.

curricula differ quite substantially. In general, despite the ongoing debate on the concept of multicultural history, the European survey is not very convincing for this concept. About 60% of the institutions report that multicultural aspects were either “hardly” taught (=less than 10% of the courses) or “not so often” taught (=between 10 and 30% of the courses) or ‚not at all’ taught in the teacher training courses. Thus, we have to assume, that multicultural approaches do not belong to the well established standards in the European teacher training curricula so far.

Aspects of civic education, such as the concept of “representative democracy”, the concept of the “rule of law” and other relevant concepts on political systems and civic institutions get more attention in the subject history curricula. As already attested in the European report of the ICCS-Study (Kerr, Sturman, Schulz & Burge, 2010) , the students’ civic knowledge is among the relatively well established standards in European secondary school education. The ICCS-report even asserts that “the European average on the ICCS international civic knowledge scale was higher than the average of all ICCS countries” ( Kerr, Sturman, Schulz & Burge, 2010: p. 48) . These findings from the ICCS-Study about the pupils’ civic knowledge also hold, in general, for the trainee students of history teachers’ education at universities and pedagogical universities.

However, we would not agree from the CHE-findings for the trainee teachers to be sufficiently educated to become active citizens or to dispose on sufficient competences and skills to live in diverse and multicultural societies (Psychogiopoulou, 2016) ―nor, to be trained to educate the next generation in this sense.

As can be seen from the next two tables, key-concepts for the understanding of today’s political and social systems like “cultural and/or linguistic diversity in society” (Figure 11) or “gender history” (Figure 12) still play a minor role in the history teachers’ training programs:

Even more surprising are the findings concerning the concept of “gender history”: This concept has been developed and established in European historical research already since the 1970ies. However, the survey on the actual teacher training curricula shows that “gender history” as a concept of historical analysis and reflection has not gained much space in the education of the European history teachers so far.

3.2.3. Examples for the Education and Training of the Teacher’s Skills: Subject Methodology, Didactic Skills, Social, Communicative, Reflective Skills, Training of Skills for Active Citizenship

Another set of questions went to the training of historical methods during subject history courses. .We asked among other, which of the following methods are trained explicitly and to which extent: Hermeneutics of history, Quantitative analysis of data, Working with statistics, Qualitative analysis of data, Discourse analysis, Oral History, Action research, Working in and with archives, Working in and with museums, Working with media sources (pictures, films). We will not refer to these findings in detail in this first overview, but we can conclude,

Figure 11. The representation of “cultural/linguistic diversity of societies” in full study programs of history teachers’ education, European survey, study year 2009/10.

Figure 12. The representation of “gender history” in full study programs of history teachers’ education, European survey, study year 2009/10.

that the skills and abilities described above get growing attention in various teacher training curricula. Hence, there is a tendency to put more awareness on the training of historical methods and to the development of the teacher trainee’s skills to apply historical methods adequately, also when working in the classroom.

A long set of questions referred to aspects of subject didactics. We ask for the quantitative significance in training courses of aspects such as “construction and re-construction of historical narratives”, “history-textbook analysis”, “analysis of school history curricula”, “use of historical research skills in teaching” et al.

As concerns the pedagogical aspects of teaching, we asked about the significance of “intercultural dialogue in history teaching”, “conflict resolution and conflict management”. For the methodological aspects, we asked about the significance of training for “planning and organizing history lessons”, “observing the teaching of history”, “analyzing the teaching process (e.g. by video)”, “teaching history through directive structure”, “interactive teaching (e.g. pupil-centred learning)”, “process-oriented forms of learning and teaching”, “organizing project-work in history teaching”, “use of media in history teaching”, or “use of information-technology in history teaching”.

These aspects will be discussed in detail in the full study, which is going to be published in autumn 2018. Just to highlight a general impression from the data survey: compared to the previous surveys of 2003/04 more emphasis seems to be given today to aspects of classroom management, interactive forms of steering the learning process, and process-oriented aspects of teaching and learning (Ecker, 1997a, 1997b) 12.

As far as subject didactics is understood in the narrow sense as the training of methodological skills to deal with historical information, a strong effort has been made during the last decade to bring such aspects into the curricula of teacher education of history teachers.

To give the example, the survey in Figure 13 indicates a relatively strong emphasis given to forms of interactive teaching in subject didactic courses:

However, as soon as we look beyond such framework and ask for the more complex competences of e.g. “bringing the historical information closer to the environment of today’s students”, or “thinking in transdisciplinary dimensions” (Figure 14) and/or “train the students to actively use the knowledge and skills acquired during university courses”, there is not much encouragement by the actual teacher training curricula to so.

1) Training in media literacy

Critical knowledge and adequate skills in dealing with media and different communication systems has become central to historical thinking and learning in today’s classroom. Historical media literacy includes: knowledge of production of media; skills to critically analyze images and films and/or the ability to contextualize sources and other historical information.

Although many training programs indicate to use media in their training courses (Figure 15), relatively few emphasis seems to be given on eLearning and new media, and very little training to the use of collaborative tools and Web 2.0. Very little emphasis seems also to be given to the ability to an active production of audiovisual products like CD-Rom, video, films and websites (Figure 16).

2) Training for co-operation and teamwork

Another example which shows some contradictions between the aims, given by the curricula and the possibilities offered by the concrete training structures can by exemplified by the key-competence for “co-operation and teamwork”:

Although most learning theories today agree on the importance of communication and face-to-face interaction in teaching and learning, the possibilities

Figure 13. The representation of “interactive teaching” in subject didactic courses―European survey.

Figure 14. The training for “interdisciplinary cooperation” in subject didactic courses―European survey.

Figure 15. The quantitative significance of training with “eLearning and new media in history teaching” in subject didactic courses―European survey.

Figure 16. The quantitative significance of training for “The production of audio-visual products like CD-ROM, video, films, websites” in subject didactic courses―European survey.

to organize or even to simulate the complexity of a learning process during teacher education courses remain insufficient. More than that, also the students’ communication and dialogue are not very much supported by the learning structures offered during teacher education studies (Spector, Merrill, Merrienboer, & Driscoll, 2008) .

The CHE-Study not only asked questions about the aims and the concrete content of curricula, but also about the forms of teaching and learning. When comparing the quantity of time, that was attributed during the entire period of the study program to e.g. “lecture” on the one side and “workshops or other forms of teamwork” on the other side, we noticed an average of about 50% of the whole study time that students had to follow in “lecture” courses (Figure 17), while an average of less than 10% was given to forms of teamwork and workshops (Figure 18).

The survey demands additional investigation, but the general picture is obvious: Forms of communication which require cooperation and teamwork in the learning process are not very much encouraged by the organization of teacher education programs. In many training programs the “lecture” remains the dominant mode of teaching during teacher education and training, while teamwork, workshop and other forms of cooperative learning get less emphasis. Consequently, there was also less emphasis given to the development of process-oriented methods and skills.

Similar tendencies can be observed for communication skills such as the training to provide oral and written feedback (Figure 19), or the training for learning to active listening to the other (Figure 20). For the majority of training programs both aspects have no prominent place in the teacher education curricula.

When we ask for the contribution of the teacher training curricula to aspects of citizenship education, like the ability to analyze conflicts, to take history as a field of learning not only about conflicts but also about conflict management and conflict resolution (Figure 21), there is also not much encouragement

Figure 17. Total time during study programs given to lecture and forms of teamwork (Figure 18 below) in comparison: Study programs of “History”, study year 2009/10―European survey.

Figure 18. Total time during study programs given to lecture (see Figure 17 above) and forms of teamwork in comparison: Study programs of “History”, study year 2009/10―European survey.