Creative Education

Vol.07 No.17(2016), Article ID:71807,16 pages

10.4236/ce.2016.717246

Steps to the Reopening of an Interdisciplinary Journal Club―Austrian Experiences

Margit Eidenberger, Sylvia Öhlinger

University of Applied Sciences for Health Professions Upper Austria, Steyr/Linz, Austria

Copyright © 2016 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: October 6, 2016; Accepted: November 4, 2016; Published: November 7, 2016

ABSTRACT

Journal Clubs are one of the methods for continuing professional development in defined working units and have proved to be an effective teaching tool. A Journal Club introduced in 2011 for the University of Applied Sciences for Health Professions Upper Austria had limited success and was discontinued after 18 months. Searching for improvements, an online survey addressing the needs and expectations of the university staff was conducted. Results showed that the majority of the respondents (98%) are interested in attending a JC in the future. The new JC should take place between 3 and 5 pm. The main reasons for not participating in the former JC were other professional obligations and no time for preparation. Critical evaluation of studies should be the main target for further capacity building realised in the future. It is planned to reopen the JC with the knowledge gained.

Keywords:

Journal Club, Evidence-Based Practice, Continuing Professional Development

1. Introduction

Journal clubs (JC) are a well-known and approved tool to establish and promote evidence-based practice (EBP) in defined working units within different health professions (Young, Rohwer, Volmink, & Clarke, 2014) . EBP has even gained higher significance for allied health professions with respect to statements about efficacy and adequacy in supplying health services (Aistleithner & Rappold, 2012) . For academic staff, JCs can be an opportunity to improve one’s critical appraisal skills (Alguire, 1998) . For medical personnel it is one method to bridge the gap between theory and practice (Goodfellow, 2004) and it is a possibility to realize EBP for quality management (Cave & Clandinin, 2007; Shojania & Grimshaw, 2005) . Furthermore, JCs provide and support vocational training (Afifi, Davis, Khan, Publicover, & Gee, 2006) . Within a group of peers the latest medical literature on a certain topic can be discussed (Chan et al., 2015) and the state-of-art advances for each speciality assessed (Gibbons, 2002) . After taking part in a JC, participants should be able to identify methodologically sound articles, appraise them critically and extract valid knowledge for clinical decision-making (Swift, 2004) . Additional objectives were defined by Lindquist et al. (1990) and included e.g. to fulfil requirements for continuing professional development and to maintain and improve professional knowledge and competence with influence on quality of care. Moreover, lecturers should transfer the technique of this evidence-based practice example and its demands to their courses for everyday practice. Nevertheless, during the process many obstacles may impede successful implementation and realization. One of the questions is how to gain and keep the interest of participants in the medium- and long-term.

At the University of Applied Sciences (UAS) for Health Professions Upper Austria, a JC was implemented by staff efforts in July 2011. Despite various approaches (e.g. kick-off presentations, invitation of an article’s author) interest was limited. Participation was voluntary and during working hours, the JC took place every three months. Articles were chosen by the organizers with emphasis on the different disciplines at the UAS (i.e. Biomedical Science, Dietetics, Midwifery, Occupational Therapy, Physiotherapy, Radiological Technology, Speech and Language Therapy as well as Master Programmes Management for Health Professions and University Didactics for Health Professions Education), to cover the professional interest of the lecturers. Because of lack of support, the JC was discontinued after 18 months.

The question remained of what had prevented the academic staff from participating in the JC provided and which factors would promote an attendance. To create the best possible starting point for the future, it was decided to undertake a survey amongst the employees of the UAS for Health Professions Upper Austria.

2. Method

An online survey to understand the needs and requirements of the university staff was conducted.

2.1. Participants and Sampling Frame

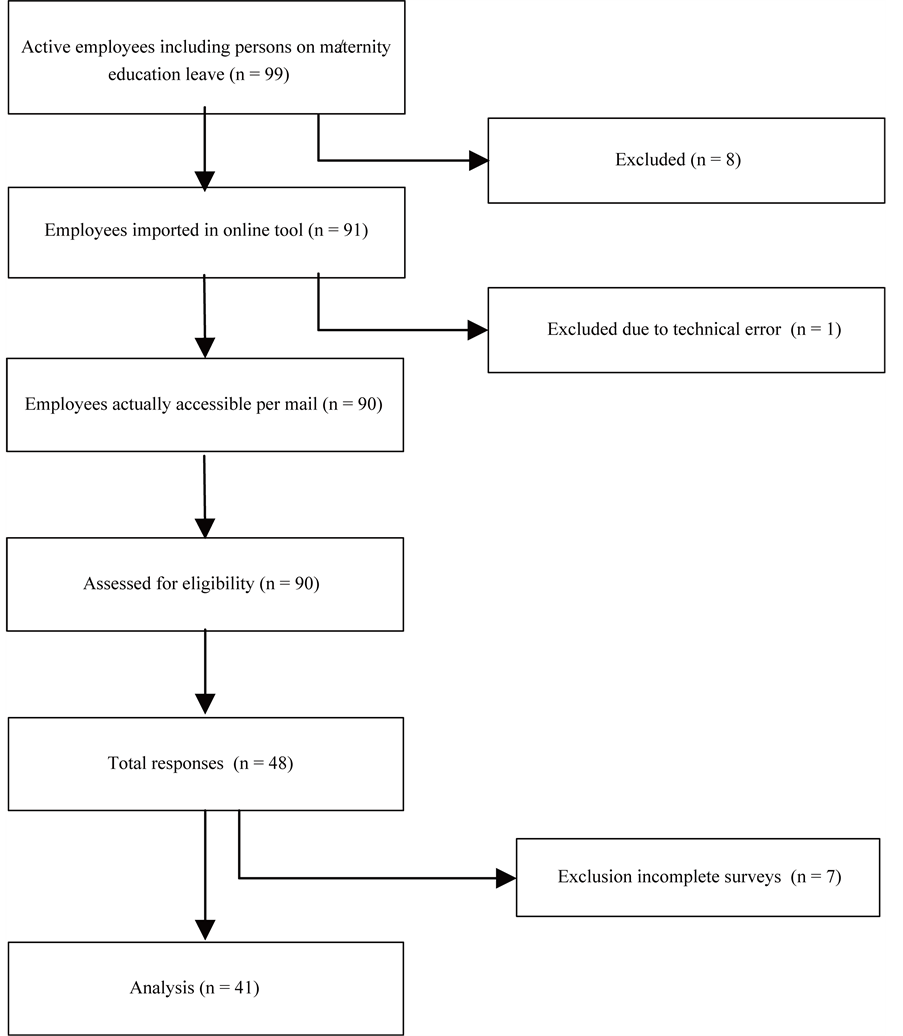

The UAS for Health Professions Upper Austria was founded in 2010 and is the youngest UAS in Austria. It is a small organisation, in sum there are 100 permanent employees (state January 2016), a lot of them (68%) are part-time. For the online survey the UAS’ for Health Professions Upper Austria permanent staff were eligible without any further inclusion and exclusion criteria. Teaching staff as well as other personnel were included because experience showed also interest of the administration employees in JCs. Part-time lecturers from outside were excluded because in a first step feasibility should be established. The sampling frame was the current employees list in January 2016, all of whom could be contacted by their official e-mail address. Persons on maternity leave were included, although it must be considered that they are not using their official address during this period. Various employees fill different positions and have therefore more than one e-mail-address: this was reduced to a single contact. Eight persons had to be excluded because of potential bias. These were members of the worker’s council or the management, who had insight into the questionnaire during development, as well as the research team. The participant’s flow chart can be seen in Figure 1. Participation was voluntary and consent was assumed when participants delivered their completed questionnaires. No incentives were offered.

Figure 1. Participant’s flow chart.

2.2. Questionnaire Development

The questionnaire (cp. Table 2) was based on an existing Dutch questionnaire (Dekkers, 2008) , which addressed the challenges facing physiotherapists. After translation the questionnaire was adapted for the special requirements of the UAS. The process of adaptation was literature-guided (Passmore, Dobbie, Parchman, & Tysinger, 2002) . Based on the current JC literature (Swift, 2004; Deenadayalan, Grimmer-Somers, Prior, & Kumar, 2008; Pitner, Fox, & Riess, 2013) various questions were added, others omitted, based on their relevance in the present context.

The questionnaire was revised in several stages. The first draft of the questionnaire was tested by conducting two expert interviews to screen for comprehension and completeness. Experts were defined as persons who have managed a successful JC in their institution, i.e. a hospital and a higher education institution, for at least two years. Based on the recorded and transcribed interviews (by an independent transcription service), the questionnaire was revised and supplemented. The second draft was tested (Williams, 2003; Kelley, Clark, Brown, & Sitzia, 2003) on three persons (i.e. physiotherapy, nursing, pharmacy) from other institutions (University of Applied Sciences FH Campus Wien, Clinical Centre Wels-Grieskirchen, Education for Medical Health Care and Nursing Linz). The feedback of these experts was used for further improvement of the questionnaire. The third draft was subsequently adapted meeting the management’s and worker’s council proposals to guarantee anonymity for the target population. To achieve this goal, certain demographic questions had to be removed.

2.3. Questionnaire

The questionnaire contained 19 questions, 18 questions per person because of one yes/no decision. These were grouped into four domains, covering the following aspects: previous participation (Q-1), supporting factors as well as obstacles for participation, organizational and personal expectations (Q2-14). Finally the participants were asked about their interest in acting as an organizer of a future JC (Q-15) and additional comments (Q-16). Questions 17 - 19 addressed participant’s demographic background, such as education and working environment. To maintain anonymity of the participants (Kelley, Clark, Brown, & Sitzia, 2003) it was not possible to collect more information in this domain (e.g. sex, affiliation to teaching/administrational staff) because of the small sample. The questionnaire contained an introduction to explain the study purpose, the expected duration and further information on the research team. The online questionnaire tool Lime Survey was used for carrying out the questionnaire, generating the link for online transmission, as well as gathering and conveying the data. Closed questions were provided with multiple options for most items including preformed answers plus an additional answer possibility for non-existing options (7 items), dichotomous for 5 items, a single option for 4 items and finally one open question for additional comments. It was decided to apply the Dillman method for web surveys to enhance the response rate (Dillmann, 2007) . This included first a pre-notice e-mail, a second e-mail with the link to the questionnaire and a third a reminder after one week. Technical function of the link was tested before submitting the questionnaires.

2.4. Data Analysis

Data was analysed using Lime Survey’s incorporated statistics as well as Office Excel statistics. Questions with preformed answers were summed up as a first step. For all items percentages and means were calculated. Moreover a single regression analysis with the independent (education, work hours, professional experience) and dependent variables (JC participation, JC expectations, JC organisation) was performed.

3. Results

Figure 1 shows the participant flow. Dillman’s method brought a substantial enhancement of the response rate, from less than 30% to 52%. 7 questionnaires had to be excluded because they were incomplete. 41 questionnaires could be included in the analysis, this corresponds to 45%. Table 1 shows the participants’ characteristics. To meet anonymity criteria these three questions were further classified as voluntary within the questionnaire, which explains several missing data in comparison with the return rate. 97% of respondents have at least a bachelor’s degree or higher.

In addition, 50% of the respondents have professional experience of 10 - 20 years, 75% work part-time. 26% did take part in the JCs previously offered at the UAS; 21% did take part in other JCs; 52% never took part in a JC (cp. Q-1).

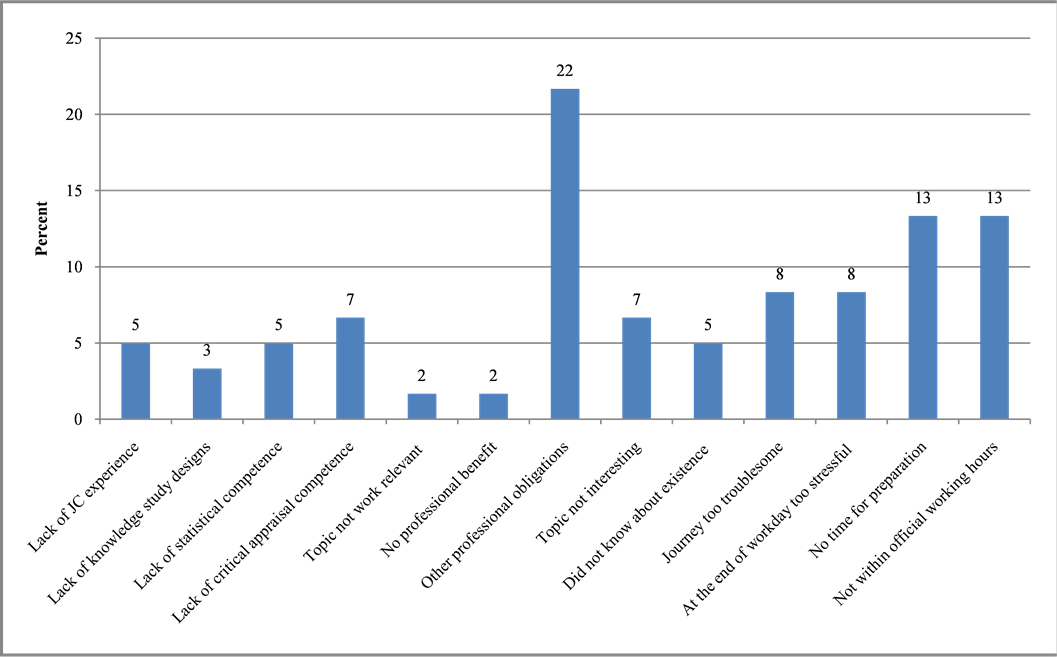

Figure 2 and Table 2 show the questionnaire results. Answers with zero percentages were omitted in Figure 2. Other professional education includes in this circumstance: elementary school, secondary school, grammar school, apprenticeship certificate or general qualification for university entrance.

Pearson’s Chi-squared tests were calculated setting the work experience and the full-time/part-time work hours as an independent variable. The analysis showed a significant correlation between the years of working experience and previous participation

Table 1. Participant’s characteristics (Q17 - 19).

Figure 2. Question 2: Reasons for not participating in the previous JC.

in a JC (p = 0.0448). Persons with more than 25 years work experience were more inclined not to participate. Respondents with work experience between 16 - 25 years represented the largest participating group.

Work experience also influenced the preferred timing for a future JC significantly (p = 0.0462). Persons with 16 to 25 years or more than 25 years practice in their individual fields of work want to set the timeframe for a future JC between 3 - 5 pm, whereas persons with less work experience (1 - 15 years) prefer 5 - 7 pm. Further analysis showed a positive trend towards a correlation between reasons for attendance or personal expected goals from the JC to years practised or work hours per week.

The third socio-economic data (highest degree) combined with question’s answers did not bring any results because of the limited number of the used subgroups.

4. Discussion

This study examined the needs and expectations of the UAS for Health Professions Upper Austria members of staff with regard to JCs generally and with regard to the first JC offered in 2011/12 in particular. In the following paragraphs selected results are presented. Based on these, steps for the development and implementation of a future JC at UAS for Health Professions are discussed.

Former post-secondary education for allied health professions and midwifery was

Table 2. Questions and corresponding answers.

transferred to higher education in Austria from 2006 to 2014 (Neuhold, 2015) , in different years depending on various federal states. For Allied Health Professions education in Austria, financial guarantees depend on the nine federal states, therefore, the implementation of the bachelor programmes is independently organized by the relevant UAS. This change was an important step, but quite delayed in Austria in comparison to other European countries. Austria was also relatively late regarding the signing and ratification of the Bologna Declaration in June, 1999 (European Higher Education Area, 2014) . Only then did the acquisition of scientific competences, in particular “EBP” become an independent and so-defined subject within the curricula. Different stake-holders, e. g. employers or insurance companies take an interest in evidence-based practice (Bennett & Bennett, 2000) , so every health professional is called on to work according to EBP principles.

4.1. Scientific Competences and Formal Academic Qualification

Our results emphasize the importance of appropriate academic skills of lecturers in study programmes for Health Professions at UAS. As Aistleithner and Rappold (2012) have noted, the teaching staff represents an important factor for the development of competencies of the students and must therefore have adequate competencies themselves.

The four following added reasons, reported by the respondents, were responsible for 20% of non-participation: lack of JC experience, lack of knowledge of study designs, lack of statistical competence, as well as a lack of critical appraisal competence (cp. Figure 2). A percentage of 52% of the staff never took part in the JC’s offered. This could be explained by the afore-mentioned reasons, but also by fluctuation of employees or by fear of embarking on something new. Lack of JC techniques (i.e. critical appraisal and statistical competence) would constitute substantial barriers. Similar reasons (lack of time, lack of statistical knowledge, lack of basic scientific understanding) were emphasised by Diermayr et al. (2015) .

These aspects can lead to work not according to literature-based evidence and shows a backlog demand for Austrian Allied Health Professions.

Our analyses showed that most participants (28%) want to augment their skills in Evidence-Based Practice by attending the JC. Providing skills or courses to become familiar with identifying suitable articles and appraisal skills are advisable (Cramer & Mahoney, 2001; Sidorov, 1995; Afifi, Davis, Khan, Publicover, & Gee, 2006) . If the personnel are not confident about their critical appraisal skills, they will avoid joining in (Esisi, 2007) . Enhancing competencies was accomplished at UAS in the meantime by various in-house lectures addressing targets like systematic literature research or critical appraisal of evidence and will be continued in the future. If there is support by the faculty, for example in the field of biostatistics, this can contribute to a successful JC (Afifi, Davis, Khan, Publicover, & Gee, 2006) . Vadaparampil et al. (2014) identified a further learning objective for JCs we consider as outstandingly important, namely “to increase critical thinking”. Critical thinking is a competence everyone should develop during an academic career. Scientific skills increase the higher the academic education accomplished. Because personnel other than lecturers were included, this would partly explain small academic numbers, as for example the majority of assistants do not have a university degree. An existing correlation could be assumed between years practised and inclination to take part in the JC. In our survey such a correlation could not be detected, whether this is due to small numbers of sub-groups or other reasons remains unknown. Offers in the field of scientific learning and research, e.g. JCs, should be compiled and considered as low-threshold activities to gather interest and attention (Kozeluh, Müller, Schütz, & Streicher, 2009) . For anonymity reasons the academic qualifications of the interviewed persons had to be cumulated in this analysis, so there was no exact comparison possible with other countries. Jette et al. showed in 2003 a percentage of 4% PhDs and 56% Master’s Degree for the USA. In a survey by the Austrian Ministry of Health Aistleithner and Rappold (2012) found a marginal percentage of PhD holders within the Allied Health Professions. The most recent numbers for Austria are 25% Master’s Degree (incorporating students at the given time) and 1% PhDs for physiotherapists, respectively (Diermayr et al. 2015) . Currently there is one person with a PhD in the discipline of midwifery in Austria. The overall objectives set out in the strategy of the UAS for Health Professions Upper Austria include an approximate level of 8% PhD for 2017. Until January 2016 there was a percentage of 5% PhDs and 68% Master’s Degree at the UAS.

4.2. Organizational Considerations and Framework Conditions

Implementing the new curriculum offered a substantial challenge for the teaching personnel in the UAS for Allied Health Professions and Midwifery. The staff had and currently has to qualify at Master’s level, is being supported financially and in terms of time by the UAS, and is engaged in part-time study. Only a few persons (6) took the possibility of educational leave and this was limited on average to seven months. These further educational programmes did not leave much time in the past for additional activities, however important they may have been considered, as shown in Figure 2.

The UAS for Health Professions Upper Austria has three locations within one federal state, with 61 (Linz), 10 (Wels) and 28 (Steyr) salaried personnel. The approximate journey time from Linz to Wels or Steyr is 30 - 60 minutes, depending on traffic. The first JCs were, with one exception (Steyr), always located in Linz. This may have affected the participation rate and is a problem that has to be overcome in the future.

As attendance was voluntary and the start-time comparatively late in the afternoon (5 pm) this may have been an obstacle, especially for part-time working female staff. Most of the personnel who responded are employed part-time (76%), which can be explained by gender, as 86% of the employees are women, many of them with household and child-caring obligations which could interfere with JCs held in the afternoon. Lecturers also work part-time because of other commitments, such as group counselling or private practice. This may have hindered participation as well. Nevertheless, a promising 98% of the staff wants to participate in future JCs, which should be offered every three months.

4.3. Barriers and Supporting Factors

The main reason (22%) for not taking part in previous JCs was “other professional obligations”, as has also been pointed out previously by Aiello-Laws (2010) , and this will remain a challenge. The next two most-chosen answers in this survey (“no time for preparation”, “not in my regular work hours”) were classified as substantial barriers. Better information for participants in advance that preparation (reading the paper chosen) would be favourable, but not obligatory, should be considered. Aiello-Laws et al. (2010) estimated that only 20% read the paper in advance and advocated five minutes scanning the selected article at the beginning of the JC meeting. Maybe reading the abstract would also be sufficient and a short resume could be given by the moderator in a structured way (Dadabhai & Lowther, n.d.) . Emphasis should here be lain on the clinical question (Khabbazi et al., 2013) which instigated the search at the beginning.

Supporting factors for a successful JC are known to be small groups, mandatory attendance and providing formal lessons for critical appraisal skills, as well as a social background such as food and beverages (Sidorov, 1995; Deenadayalan, Grimmer-So- mers, Prior, & Kumar, 2008) . Success also improves with suitable infrastructure (e.g. isolated timeframe and role distribution). In a recent study Lizarondo et al. (2012) found that searching for relevant articles undertaken by defined researchers, as well as providing appraisal summaries by specified facilitators, served to address the described barriers. Our survey showed that the prospective timeframe is a substantial concern of the employees. 44% of the respondents want to know in advance about the time necessary for preparation as well as for the JC itself (cp. Table 2, Q-7). According to Deena- dayalan et al. (2008) it is crucial to supply the staff with knowledge about goals and organizational structure beforehand and the conditions should be adhered to precise. 48% want to be informed about aims and framework. By contrast, only 6% want beverages to be offered, whilst it must be added that it is obligatory at the UAS to offer water and tea/coffee during meetings to enhance participant’s sense of well-being. Although mandatory attendance can enhance presence rates (Afifi, Davis, Khan, Publicover, & Gee, 2006) , it is preferred to keep the voluntary basis. Swift (2004) refers to its advantages and disadvantages and it was chosen to keep it voluntary because this is in accordance with management’s preferences and we hope to promote personal, not forced interest. The optimal group size is chosen to be eight participants (Harris et al., 2011) . This would be even easier if the JC is topic-related, as wished by 28% of respondents. The “regular work hours” as a non-participation reason (cp. Figure 2, Q-2) is contradicted by Q-10, because the most convenient timeframe chosen was between 3 - 5 pm, outside of most peoples’ regular hours. Interestingly, for these 39% whether the JC takes place during work hours seems not to be crucial. It should be noted that the desired timeframe is earlier than the previously-offered JCs.

4.4. Reasons for Participating

The main reason for participating (26%) for the respondents was the possibility for professional discourse. An atmosphere where it is possible to learn from each other would be created under the peer-assisted learning scheme (Topping, 2005) . Afifi et al. (2006) confirm this and lay emphasis on the fact that a JC is an opportunity for social interaction. This is very important in our situation, as keeping abreast of colleagues from other locations of the UAS is difficult.

The principles of adult learning are outlined by Swift (2004) , e.g. the use of problem-solving techniques; to vary teaching approaches to suit different learning styles; the use of active learner participation and to provide frequent constructive feedback. This would be the challenge for the future organisational team and the moderator (cp. Q-6) in meeting participant’s needs. “Joint discussions”, “creating a familiar atmosphere” and “adherence to general group rules” are the most urgent topics for these persons to consider.

4.5. Procedure/Enforcement

Despite the former JCs troubles, the UAS’ staff is very interested in this method. Cramer and Mahoney (2001) recommended further ongoing evaluation for transfer of predefined educational objectives, which was not done in the past, but will be revised. On the other hand, Serghi et al. (2015) suggested pre-session quizzes to ensure that the articles were generally read in advance of the JC. A similar approach was used by Afifi et al. (2006) , using “stimulus questions” at the beginning.

The travelling question could be overcome by using modern technology e.g. an E-Journal Club (Zarghi, Mazlom, & Rahban, 2012) . This was suggested by an additional comment by one of the survey’s participants and is also mentioned by Chan et al. (2015) or Phillips and Glasziou (2004) . Using Skype for example could offer a possibility to take part online without losing valuable time travelling.

After completing a JC, post-session evaluation and a final post-course evaluation are advocated by Serghi et al. (2015) , Cramer and Mahoney (2001) as well as Kleinpell (2002) . This, combined with the afore-mentioned pre-session quizzes could enhance attendance rates because participants would be more aware if pre-set goals were reached by themselves. A shared computer drive can be used for storage of discussed articles and a summary of journal club findings for those who were unable to participate but want to be informed.

Perhaps an official overview of how to moderate a group or use the “critical friend technique” (Balthasar, 2012) could be helpful for moderators. The use of a critical appraisal checklist can help with this also. Another possibility is the sharing of tasks: the group will be subdivided and assigned critical appraisal questions as recommended by Swift (2004) and Phillips and Glasziou (2004) . The participants should get a “take home message”, being able to answer three simple questions about the article (Sawhney, 2006) . The mentioned results give us the agenda for the next club meeting.

5. Limitations

This study has several limitations. First the small sample size can lead to bias. This is attenuated by the unexpected high response rate. Second, one person, who only took up a position with the worker’s council shortly before questionnaire distribution, was not excluded despite falling under our exclusion criteria. Third, for unexplainable technical reasons one person did not get the e-mail which was discovered at a later stage and weakens the results.

6. Conclusion

Journal clubs are recognised as an important source of knowledge by the University of Applied Sciences for Health Professions Upper Austrian staff. Methodological as well as organizational and social causes can contribute to a successful JC. Nearly 98% of the respondents declared that they wanted to participate in future JCs. The main changes identified as required for re-opening are as follows: collecting clinical questions, creating a participator-tailored framework, use of a critical appraisal checklist, evaluation of each single session and the whole course after completion of a study year.

It is planned to reopen the JC with the knowledge gained. There is a commitment of the heads of the various study programmes at the UAS for the reopening of the JC based on these results. In a next step, it is intended to develop a concept for a new JC by involving interested members of the staff. Staff-tailored offers and provision of additional technical support (video and audio transmitted conferences) should encourage attendance. Teaching staff should be freed from other obligations for the proposed JC timeframe. Transfer into every lecturer’s courses is first and foremost imaginable with topic-related and rotational discipline-centred groups, offered at different locations. The proposed future JC should take these aspects into account to ensure a successful continuation of professional development at the UAS.

Funding

Funding for extraordinary expenses (literature, software fees, transcription, translation assistance and statistical assistance) was granted by the UAS.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mrs. M. Ehrenmüller for assisting with the statistical analysis und Mr. Peter Orgill for proofreading the paper.

Cite this paper

Eidenberger, M., & Öhlinger, S. (2016). Steps to the Reopening of an Interdisciplinary Journal Club―Aus- trian Experiences. Creative Education, 7, 2613-2628. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2016.717246

References

- 1. Afifi, Y., Davis, J., Khan, K., Publicover, M., & Gee, H. (2006). The Journal Club: A Modern Model for Better Service and Training. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist, 8, 186-189.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1576/toag.8.3.186.27256 [Paper reference null] - 2. Aiello-Laws, L., Clark, J., Steele-Moses, S., Jardine, S., & McGee, L. (2010). Designing and Creating a Journal Club for Oncology Nurses. A How-To Guide. Pittsburgh: Oncology Nursing Society. [Paper reference null]

- 3. Aistleithner, R., & Rappold, E. (2012). Health Care 2020—Forschungsstrategie für ausgewählte Gesundheitsberufe. Wien: Gesundheit Österreich GmbH.

http://www.goeg.at/de/Bereich/Forschungsstrategie-ausgewaehlte-Gesundheitsberufe.html [Paper reference null] - 4. Alguire, P. (1998). A Review of Journal Clubs in Postgraduate Medical Education. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 13, 347-353.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00102.x [Paper reference null] - 5. Balthasar, A. (2012). Fremd und Selbstevaluation kombinieren: Der “Critical Friend Approachals” Option. Zeitschrift für Evaluation, 11, 173-198. [Paper reference null]

- 6. Bennett, S., & Bennett, J. W. (2000). The Process of Evidence-Based Practice in Occuational Therapy: Informing Clinical Decisions. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 47, 171-180.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/CH00068 [Paper reference null] - 7. Cave, M. T., & Clandinin, D. J. (2007). Revisiting the Journal Club. Medical Teacher, 29, 365-370.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01421590701477415 [Paper reference null] - 8. Chan, T. M., Thoma, B., Radecki, R., Topf, J., Woo, H. H., Kao, L.S., Cochrane, A., Hiremath, S., & Lin, M. (2015). Ten Steps for Setting up an Online Journal Club. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 35, 148-154.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/chp.21275 [Paper reference null] - 9. Cramer, J. S., & Mahoney, M. C. (2001). Introducing Evidence Based Medicine to the Journal Club, Using a Structured Pre and Post Test: A Cohort Study. BMC Medical Education, 1, 6.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-1-6 [Paper reference null] - 10. Dadabhai, S., & Lowther, S. (n.d.). Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

http://www.jhsph.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/welch-center-for-prevention-epidemiology-and-clinical-research/_pdf/Journal_Club_Aids/JrnlClub_Tips.pdf [Paper reference null] - 11. Deenadayalan, Y., Grimmer-Somers, K., Prior, M., & Kumar, S. (2008). How to Run an Effective Journal Club: A Systematic Review. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 14, 898-911.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01050.x [Paper reference null] - 12. Dekkers, H. (2008). Vragenlijst. (Unpublished) [Paper reference null]

- 13. Diermayr, G., Schachner, H., Eidenberger, M., Lohkamp, M., & Salbach, N. (2015). Evidence-Based Practice in Physical Therapy in Austria: Current State and Factors Associated with EBP Engagement. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 21, 1219-1234.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jep.12415 [Paper reference null] - 14. Dillmann, D. A. (2007). Mail and Internet Survey: The Tailored Design Method. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Paper reference null]

- 15. Esisi, M. (2007). Journal Clubs. BMJ Careers—Journal Clubs.

http://careers.bmj.com/careers/advice/view-article.html?id=2631 [Paper reference null] - 16. European Higher Education Area. (2014). Bologna Process—European Higher Education Area. European Higher Education Area.

http://www.eurashe.eu/library/modernising-phe/Bologna_1999_Bologna-Declaration.pdf [Paper reference null] - 17. Gibbons, A. J. (2002). Organizing a Successful Journal Club. BMJ, 325, 137-138.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.325.7371.S137a [Paper reference null] - 18. Goodfellow, L. M. (2004). Can a Journal Club Bridge the Gap between Research and Practice? Nurse Educator, 29, 107-110.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006223-200405000-00008 [Paper reference null] - 19. Harris, J., Kearley, K., Heneghan, C., Meats, E., Roberts, N., Perera, R., & Kearley-Shiers, K. (2011). Are Journal Clubs Effective in Supporting Evidence-Based Decision Making? A Systematic Review. BEME Guide No. 16. Medical Teacher, 33, 9-23.

http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2011.530321 [Paper reference null] - 20. Jette, D. U., Bacon, K., Batty, C., Carlson, M., Ferland, A., Hemingway, R. D., Hill, J. C., Ogilvie, L., & Volk, D. (2003). Evidence-Based Practice: Beliefs, Attitudes, Knowledge, and Behaviors of Physical Therapists. Physical Therapy, 83, 786-805. [Paper reference null]

- 21. Kelley, K., Clark, B., Brown, V., & Sitzia, J. (2003). Good Practice in the Conduct and Reporting of Survey Research. International Journal or Quality in Health Care, 15, 261-266.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzg031 [Paper reference null] - 22. Khabbazi, A., Hajialiloo, M., Kolahi, S., Nakhjovani, M., Noshad, H., & Saleh, P. (2013). A Comparison of Learning in Traditional and Evidence Based Journal Clubs. Research and Development in Medical Education, 2, 5-9. [Paper reference null]

- 23. Kleinpell, R. M. (2002). Rediscovering the Value of the Journal Club. American Journal of Critical Care, 11, 412-414. [Paper reference null]

- 24. Kozeluh, U., Müller, J., Schütz, O., & Streicher, B. (2009). Good Practice Elemente von dialogisch/diskursiven Verfahren und niederschwelligen Science Center Aktivitäten zur Unterstützung von Good Governance im Bereich Wissenschaft und Gesellschaft. Wien: Rat für Forschung und Technologieentwicklung. [Paper reference null]

- 25. Lindquist, R., Robert, R. C., & Treat, D. (1990). A Clinical Practice Journal Club: Bridging the Gap between Research and Practice. Focus on Critical Care, 17, 402-406. [Paper reference null]

- 26. Lizarondo, L. M., Kumar, S., & Grimmer-Somers, K. (2012). Exploring the Impact of a Structured Model of Journal Club in Allied Health—A Qualitative Study. Creative Education, 3, 1094-1100.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2012.326164 [Paper reference null] - 27. Neuhold, A. (2015). überführung in den FH-Sektor. Wien: MTD Forum. [Paper reference null]

- 28. Passmore, C., Dobbie, A. E., Parchman, M., & Tysinger, J. (2002). Guidelines for Constructing a Survey. Family Medicine, 34, 281-286. [Paper reference null]

- 29. Phillips, R., & Glasziou, P. (2004). What Makes Evidence-Based Journal Clubs Succeed? Evidence Based Medicine, 9, 36-37.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ebm.9.2.36 [Paper reference null] - 30. Pitner, N. D., Fox, C. A., & Riess, M. L. (2013). Implementing a Successful Journal Cub in an Anesthesiology Residency Program. F1000Research, 2, 15.

http://dx.doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.2-15.v1 [Paper reference null] - 31. Sawhney, R. (2006). How to Prepare an Outstanding Journal Club Presentation. The Hematologist: Ash News and Reports, 3. [Paper reference null]

- 32. Serghi, A., Goebert, D., Andrade, N., Hishinuma, E., Lunsford, R., & Matsuda, N. (2015). One Model of ResidencyJournal Clubs with Multifaceted Support. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 27, 329-340.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2015.1044658 [Paper reference null] - 33. Shojania, K. G., & Grimshaw, J. M. (2005). Evidence-Based Quality Improvement: The State of the Science. Health Affairs, 24, 138-150.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.138 [Paper reference null] - 34. Sidorov, J. (1995). How Are Internal Medicine Residency Journal Clubs Organized, and What Makes Them Successful? Archives of Internal Medicine, 155, 1193-1197.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1995.00430110111012 [Paper reference null] - 35. Swift, G. (2004). How to Make Journal Clubs Interesting. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 10, 67-72.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/apt.10.1.67 [Paper reference null] - 36. Topping, K. J. (2005). Trends in Peer Learning. Educational Psychology, 25, 631-645.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01443410500345172 [Paper reference null] - 37. Vadaparampil, S. T., Simmons, V., Lee, J.-H., Malo, T., Klasko, L., Rodriguez, M., Waddell, R., Gwede, C. K., & Meade, C. (2014). Journal Clubs: An Educational Approach to Advance Understanding among Community Partners and Academic Researchers about CBPR and Cancer Health Disparities. Journal of Cancer Education, 29, 122-128.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13187-013-0557-y [Paper reference null] - 38. Williams, A. (2003). How to Write and Analyse a Questionnaire. Journal of Orthodontics, 30, 245-252.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ortho/30.3.245 [Paper reference null] - 39. Young, T., Rohwer, A., Volmink, J., & Clarke, M. (2014). What Are the Effects of Teaching Evidence-Based Health Care (EBHC)? Overview of Systematic Reviews. PLoS ONE, 9, e86706.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0086706 [Paper reference null] - 40. Zarghi, N., Mazlom, S. R., & Rahban, M. (2012). Challenges of E-Journal Club: A Case Study. Creative Education, 3, 708-711.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2012.36105 [Paper reference null]