Food and Nutrition Sciences

Vol.4 No.2(2013), Article ID:27719,6 pages DOI:10.4236/fns.2013.42021

History of Vitamin A Supplementation Reduces Severity of Diarrhea in Young Children Admitted to Hospital with Diarrhea and Pneumonia

![]()

1Centre for Nutrition & Food Security (CNFS), International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Dhaka, Bangladesh; 2Clinical Services (CS), Dhaka, Bangladesh; 3Research Administration Services (RAS), Dhaka, Bangladesh; 4Centre for Communicable Diseases (CCD), Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Email: *chisti@icddrb.org

Received December 21st, 2012; revised January 21st, 2013; accepted January 30th, 2013

Keywords: Bangladesh; Diarrhea; Children; Lower Chest Wall In-Drawing; Pneumonia; Vitamin A Supplementation

ABSTRACT

Background: Although the role of vitamin A in childhood pneumonia in association with diarrhea is not fully proven, we did not find any published data demonstrating the impact of lack of vitamin A supplementation in under-five children who present with the co-morbidities of pneumonia and diarrhea. This study examined whether previous vitamin A supplementation was associated with reduced severity and duration of diarrhea and pneumonia for children presenting with both illnesses. Methods: All admitted children (n = 189) aged 0 - 59 months to the Special Care Ward of the Dhaka Hospital of icddr,b with diarrhea and radiological pneumonia from September-December 2007 were enrolled. We compared clinical features of the children who received (n = 96) and did not receive (n = 93) high potency capsule vitamin A supplementation during previous immunization according to EPI schedule. Results: In logistic regression analysis, after adjusting for potential confounders such as respiratory rate, lower chest wall in-drawing, severe wasting and systolic blood pressure, vitamin A non-supplemented children with pneumonia and diarrhea more often presented in their early infancy (95% CI 1.01 - 1.09), had duration of diarrhea for >4 days (95% CI 1.79 - 11.88), had clinical dehydration (95% CI 1.2 - 5.63), and more often required hospitalization for >7 days (95% CI 1.03 - 8.87). But, there was no significant difference in the clinical features of pneumonia, such as history of cough, respiratory rate, lower chest wall in-drawing, nasal flaring, head nodding, grunting respiration, cyanosis, and inability to drink between the groups. Conclusion: Lack of vitamin A supplementation in under-five children with radiological pneumonia and diarrhea is independently associated with young infancy, duration of diarrhea for >4 days, dehydration and hospitalization for >7 days which underscores the importance of routine supplementation of vitamin A in young infancy. However, lack of vitamin A supplementation did not influence any clinical signs of pneumonia.

1. Introduction

Pneumonia and diarrhea are the two leading causes of death and morbidity in under-five children in developing countries [1,2]. Among the estimated 7.6 million global deaths in under-five children in 2010, pneumonia and diarrhea accounted for 18% and 11% of the deaths respectively [3]. In many developing countries, these two are the common co-morbidities in under-five children with high morbidity and deaths [4,5]. Supplementation of capsule vitamin A has a proven role for the reduction of the incidence of diarrhea [6-8] but its role in childhood pneumonia in association with diarrhea is not fully proven [9]. Development of clinical features, especially the danger signs of pneumonia and consequences of diarrhea usually depends on disease severity. Vitamin A supplementation often reduces disease severity and deaths in malnourished children with diarrhea [7,8,10]. The overall benefits of vitamin A supplementation for the prevention of mortality and illness are well established [11]. However, we failed to identify any published literature demonstrating the impact of lack of vitamin A supplementation in under-five children who present with the co-morbidities of pneumonia and diarrhea. A large number of children attend the Dhaka Hospital of the International Centre for Diarrheal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b) with diarrhea and pneumonia each year, and they often present with dangers signs of pneumonia and complications of diarrhea. This study examines if vitamin A supplementation may be associated with benefits for children who become sick with such kind of illness.

2. Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

The study (icddr,b; grant no Gr-00233) was approved by the Ethical Review Committee (ERC) of International Centre for Diarrheal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr, b) and an informed verbal consent was obtained from parents or guardians of all participating children. Children whose caregivers did not give consent were not included in the study but still received standard hospital care. Originally this data has been obtained from a prospective hospital audit which was initially designed to defend the thesis in Masters of Medicine (MMed) of the primary author in the University of Melbourne (UOM), Melbourne, Australia. Although the clinical audit is routine for hospital care, and used to be done only with verbal consent from the parents or guardians of the patients following the hospital policy. Parents or guardians were assured about the non-disclosure of information collected from them, and were also informed about the use of data for analysis and using the results for improving patient care activities as well as publication without disclosing the name or identity of their children. A brief verbal consent form describing the above measures to the parent or guardian was used during the audit for documentation of the consent. ERC was quite satisfied with voluntary participation, the maintenance of the rights of the participants and confidential handling of personal information by the hospital audit committee and approved this consent procedure.

2.2. Patient Enrollment

A clinical audit was performed among those admitted to Special Care Ward (SCW) of the Dhaka Hospital of icddr,b between September and December 2007. Each year, this hospital provides care and treatment to over 120,000 patients of all ages. The majority of the patients come from a poor socio-economic backgrounds living in urban and peri-urban Dhaka, the capital city of Bangladesh. Being a specialized diarrhea treatment facility, essentially all patients attend with diarrhea with or without associated complications, and with or without other health problems. The majority of the patients are underfive children, and malnutrition and pneumonia are the most common co-morbidities among them. On arrival to the hospital triage nurses obtain brief medical history and make a quick assessment of the patients, focusing on the severity and complications of diarrhea and dehydration status but also look for associated health problems. Following this, patients are referred either to the emergency physician for re-assessment or are admitted to an appropriate ward of the hospital. Patients with severe illnesses, including those with abnormal mental status, severe and very severe pneumonia defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria [12], hypoxemia, cyanosis, suspected sepsis, and convulsions are admitted to the SCW for further assessment, closer observation, and monitoring with appropriate laboratory workups and management. After admission to the SCW, attending physicians re-evaluate the patients, commence required work ups, and prescribe a management plan.

2.3. Study Design

This analysis involved all diarrheal children of both sex, aged 0 to 59 months, who were admitted to the SCW with clinical and radiological evidence of pneumonia along with their diarrhea during September-December 2007. Comparison of the clinical features of pneumonia and diarrhea was made between the children under five who received and who did not receive high potency vitamin A supplementation [one capsule contains 200,000 iu; recommended doses: for children age >1 year: 1 capsule (8 drops), 6 months - 1 year: half capsule (4 drops), <6 months: 1/4th capsule (2 drops)] during neonatal period [13] or 6 months prior to admission which was earlier. Pneumonia was clinically diagnosed according to the (WHO) criteria [12] and confirmed by radiological evidence of consolidation or patchy opacities in the lungs. Diarrhea was defined as the passage of three or more abnormally loose or watery stool in the previous 24 hours. Relevant clinical information was collected by attending physicians soon after enrollment of the children into the study, after obtaining oral consents from the parents/ attendants. Care givers of the participating children were categorically asked by the attending physicians whether the patient received the supplementation of vitamin A capsule or not and all the care givers of participating children answered the question.

Standard hospital guidelines were followed in the clinical management of the study children, which included correction of dehydration using either Oral Rehydration Salts (ORS) solution (generally for children with some dehydration) or intravenous fluids (for those with severe dehydration and also for those who were unable to drink ORS in adequate amounts due to any reason); appropriate antimicrobial therapy; diets appropriate for age; and micronutrients, vitamins and minerals as and when indicated. Management of severe protein-energy malnutrition was done in accordance with the hospital’s protocolized guidelines [14,15].

2.4. Statistical Methods

We developed and pre-tested Case Report Forms (CRF) and finalized them for collection of relevant data from the source document (hospital records). All data were entered onto a personal computer and edited before analysis using SPSS for Windows (version 15.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago) and Epi Info (version 6.0, USD, Stone Mountain, GA). We compared differences in proportions by Chi-square test or Fisher exact test when indicated, and differences in means by Student’s t-test or MannWhitney test when indicated. A probability of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We assessed strength of association by estimating odds ratio (OR) and it’s 95% confidence intervals (CI), and used it both in univariate and logistic regression analyses. Socio-demographic and relevant clinical characteristics in association with diarrhea and pneumonia were analyzed and these included age, sex, socio-economic condition, duration of diarrhea, clinical dehydration, breast-feeding status, fever, cough, respiratory rate (counted for one full minute in a calm child), lower chest wall in-drawing (in-drawing of the bony structures of the lower chest wall during inspiration), head nodding, nasal flaring, cyanosis, grunting respiration, inability to drink, severe wasting (z score for weight for height <−3 of the median of the WHO anthropometry), hypoxemia (arterial oxygen saturation in air <90% which was measured by pulse oximetry) and systolic blood pressure. Initially, we performed univariate analyses of these characteristics to identify factors that were significantly associated with the lack of vitamin A supplementation and then performed logistic regression analysis using only factors that were significantly associated with the lack of vitamin A supplementation, after adjusting for potential confounders, to determine actual impact of the lack of vitamin A supplementation on clinical features of pneumonia and diarrhea.

3. Results

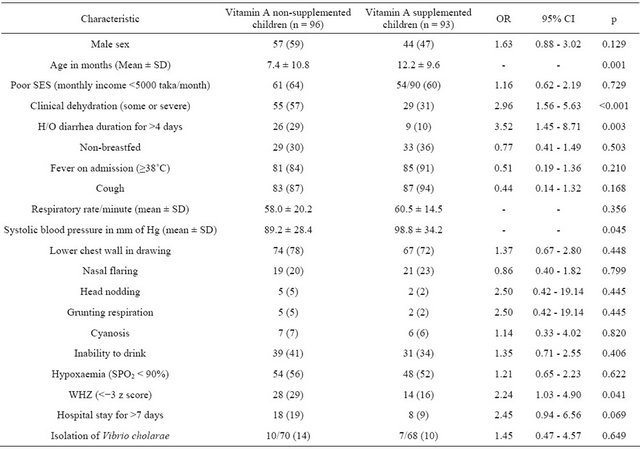

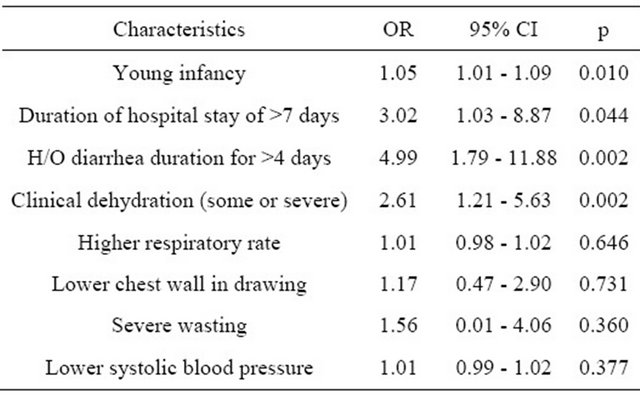

Out of 258 admitted children in the SCW, 189 children were enrolled in the study, and 96 of them did not receive the supplementation of vitamin A. Children who did not receive vitamin A supplementation had lower mean systolic blood pressure and were severely wasted on admission compared to those who received vitamin A supplementation (Table 1). Higher proportion of children who did not receive vitamin A supplementation had Vibrio cholerae cultured from their fecal specimens, but the difference was not significant (Table 1). Most importantly, there was no significant difference in clinical features of pneumonia such as cough, respiratory rate, lower chest wall in drawing, nasal flaring, head nodding, grunting respiration, cyanosis, and unable to drink among the groups (Table 1). Additionally, there was even distribution of male sex, poor socio-economic conditions, non-breast feeding, and hypoxemia in two groups (Table 1). In logistic regression, after adjusting for potential confounders such as respiratory rate, lower chest wall indrawing, severe wasting and systolic blood pressure, the probability of the young infancy, history of diarrhea duration for >4 days, presence of clinical dehydration, and the need for hospitalization for >7 days were significantly higher among those who did not receive vitamin A supplementation in the previous six months (Table 2).

4. Discussion

Vitamin A supplementation has been reported to reduce severity of childhood diarrhea and clinical dehydration in the following six months [16]. Our finding of higher frequency of dehydration and the probability of continuation of diarrhea beyond four days at home as well as the need for longer hospitalization are consistent with the report. Clinical dehydration in higher proportion of vitamin A non-supplemented children may be explained by the higher rate of isolation of V. cholerae among these children, although the rates of isolation of pathogens was not significantly different between the two groups [13]. Longer duration of diarrhea at home recorded during the hospital visit, is common in vitamin A non-supplemented children [13], which might have partly contributed to clinical dehydration in our children who did not receive vitamin A supplementation. Higher proportion of severe malnutrition among vitamin A non-supplemented children might explain the prolonged hospital stay. Our findings corroborates with findings of earlier studies that observed higher proportion of vitamin A non-supplemented children to have severe acute malnutrition [7,8], which is also important in explaining other observations in our study. Longer time is necessary for the rehydration of severely malnourished children with diarrhea than their healthier counterparts [15], and they often have severe co-infections [17] that might contribute to prolonged hospital stay. Significantly higher proportion of our vitamin A non-supplemented children had persistent hypotension even after correction of clinical dehydration and also in children with no clinical dehydration, which suggests their higher probability for severe sepsis or septic shock. The disease severity was higher in significantly higher proportion of non-supplemented children, which might have contributed to their prolonged hospital stay.

Although vitamin A supplementation is recommended up to neonatal age [18], the frequent observation of

Table 1. Comparison of clinical characteristics of under-five children with pneumonia and diarrhea who had and had not received vitamin A supplementation.

Figures represent n (%), unless specified. OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; SD: standard deviation; WHZ: weight for height z score; SpO2 = transcutaneously measured blood oxygen concentration.

Table 2. Results of logistic regression to explore factors independently associated with the lack of vitamin A supplementation in under-five children with radiologically proven pneumonia and diarrhea.

young infant in the vitamin A non-supplemented group might have confounded the whole observation mentioned above. Young infancy is a well known contributor to the severity and prolongation of acute diarrhea as well as prolongation of hospitalization [19]. However, the observation from our study indicates that the supplementation of vitamin A in young infants may also be prioritized.

We did not observe significant differences in the clinical features of pneumonia, such as cough, respiratory rate, lower chest wall in drawing, nasal flaring, head nodding, grunting respiration, cyanosis, and unable to drink between the groups of children who received vitamin A supplementation and who did not. Lower chest wall in-drawing, nasal flaring, head nodding, grunting respiration, cyanosis, and unable to drink are the danger signs of pneumonia in WHO algorithm for diagnosing pneumonia in under-five children [20]. In the line of observation of an earlier study, we anticipated differences in the frequency of danger signs of pneumonia [16]. Greater proportion of severely malnourished children in our non vitamin A supplemented group of children might have confounded our results. Poor inflammatory response in such children might have impeded an adequate increase in the respiratory rate [17]. Moreover, fast breathing and lower chest wall in-drawing, as the clinical signs of pneumonia, are very insensitive in severely malnourished children [2,21], which might have contributed to our observations. Additionally, a recent systematic review involving eleven randomized, controlled trials exploring prophylactic role and 9 randomized, controlled trials evaluating therapeutic role of vitamin A supplementation in childhood pneumonia, reported no prophylactic or therapeutic role [22] and another metaanalysis of results of five randomized, controlled trials in non-diarrheal children with non-measles pneumonia accounted no impact of vitamin A supplementation on the severity of pneumonia [23], and these findings are consistent with our observation.

Age has been revealed as a potential confounder in this study given the different age distributions in the two groups and this event is a major limitation of the study. Small sample size is another limitation of our study, which resulted in reduced power to detect significance.

5. Conclusion

Based on the findings, we may conclude that under-five children with radiological pneumonia and diarrhea, who did not receive vitamin A supplementation at neonatal period or 6 months prior to admission which was earlier, more frequently presented in their early infancy, more often had a history of diarrheal illness for more than 4 days and clinical dehydration, and they more frequently require hospitalization for more than 7 days. Results of our analyses also suggest that lack of high potency vitamin A supplementation in the previous six months does not have an impact on the clinical signs in children with radiologically-proven pneumonia. Finally, the overall results of our study accentuate the importance of vitamin A supplementation not only in children under five beyond young infancy but also in young infants and the supplementation may help to reduce the disease severity in children having the co-morbidity of diarrhea and pneumonia.

6. Acknowledgements

This research study was funded by the Dhaka Hospital of International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (ICDDR, B; grant No. Gr-00233) and its donors, which provide unrestricted support to ICDDR, B for its operations and research. Current donors providing unrestricted support include: Australian Agency for International Development, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, Canadian International Development Agency, Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, and the Department for International Development, United Kingdom. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. We would like to express our sincere thanks to all of our donors. We would like to express our sincere thanks and gratitude to all physicians including clinical fellows, nurses, members of feeding team, cleaners of SCW, and the care-givers of the study participants for their invaluable support and contribution during patient enrollment and data collection.

REFERENCES

- R. E. Black, S. Cousens, H. L. Johnson, J. E. Lawn, I. Rudan, D. G. Bassani, et al., “Global, Regional, and National Causes of Child Mortality in 2008: A Systematic Analysis,” Lancet, Vol. 375, No. 9730, 2010, pp. 1969- 1987. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60549-1

- M. J. Chisti, M. Tebruegge, S. La Vincente, S. M. Graham and T. Duke, “Pneumonia in Severely Malnourished Children in Developing Countries—Mortality Risk, Aetiology and Validity of WHO Clinical Signs: A Systematic Review,” Tropical Medicine & International Health, Vol. 14, No. 10, 2009, pp. 1173-1189.

- L. Liu, H. L. Johnson, S. Cousens, J. Perin, S. Scot, et al., “Global, Regional, and National Causes of Child Mortality: An Updated Systematic Analysis for 2010 with Time Trends since 2000,” Lancet, Vol. 379, No. 9832, 2012, pp. 2151-2161. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60560-1

- M. J. Chisti, T. Duke, C. F. Robertson, T. Ahmed, A. S. Faruque, P. K. Bardhan, et al., “Co-Morbidity: Exploring the Clinical Overlap between Pneumonia and Diarrhoea in a Hospital in Dhaka, Bangladesh,” Annals of Tropical Paediatrics, Vol. 31, No. 4, 2011, pp. 311-319. doi:10.1179/1465328111Y.0000000033

- M. J. Chisti, S. Huq, S. K. Das, M. A. Malek, T. Ahmed, A. S. Faruque, et al., “Predictors of Severe Illness in Children under Age Five with Concomitant Infection with Pneumonia and Diarrhea at a Large Hospital in Dhaka, Bangladesh,” Southeast Asian Journal of Tropiacl Medicine & Public Health, Vol. 39, No. 4, 2008, pp. 719-727.

- H. E. El Bushra, L. R. Ash, A. H. Coulson and C. G. Neumann, “Interrelationship between Diarrhea and Vitamin A Deficiency: Is Vitamin A Deficiency a Risk Factor for Diarrhea?” Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal, Vol. 11, No. 5, 1992, pp. 380-384. doi:10.1097/00006454-199205000-00008

- R. B. Grubesic and B. J. Selwyn, “Vitamin A Supplementation and Health Outcomes for Children in Nepal,” Journal of Nursing Scholarship Vol. 35, No. 1, 2003, pp. 15-20. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.2003.00015.x

- J. Haidar, D. Tsegaye, D. H. Mariam, H. N. Tibeb and N. M. Muroki, “Vitamin A Supplementation on Child Morbidity,” East African Medical Journal, Vol. 80, No. 1, 2003, pp. 17-21.

- S. Sattar, T. Ahmed, C. H. Rasul, D. Saha, M. A. Salam and M. I. Hossain, “Efficacy of a High-Dose in Addition to Daily Low-Dose Vitamin a in Children Suffering from Severe Acute Malnutrition with Other Illnesses,” PLoS One, Vol. 7, No. 3, 2012, Article ID: e33112. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0033112

- A. Sommer, I. Tarwotjo, E. Djunaedi, K. P. West Jr., A. A. Loeden, R. Tilden, et al., “Impact of Vitamin A Supplementation on Childhood Mortality. A Randomised Controlled Community Trial,” Lancet, Vol. 1, No. 8491, 1986, pp. 1169-1173.

- E. Mayo-Wilson, A. Mdad, K. Herzer, M. Y. Yakoob and Z. A. Bhutta, “Vitamin A Supplements for Preventing Mortality, Illness, and Blindness in Children Aged under 5: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” British Medical Journal, Vol. 343, 2011, Article ID: d5094. doi:10.1136/bmj.d5094

- World Health Organization, “Acute Respiratory Infections in Children: Case Management in Small Hospitals in Developing Countries. A Manual for Doctors and Other Senior Health Workers,” World Health Organization, Geneva, 1990.

- M. S. Hossain, M. A. Salam, G. H. Rabbani, I. Kabir, R. Biswas and D. Mahalanabis, “Tetracycline in the Treatment of Severe Cholera Due to Vibrio cholerae O139 Bengal,” Journal of Health Population & Nutrition, Vol. 20, No. 1, 2002, pp. 18-25.

- World Health Organization, “Management of Severe Malnutrition: A Manual for Physicians and Other Senior Health Workers,” World Health Organization, Geneva, 1999.

- T. Ahmed, M. Ali, M. M. Ullah, I. A. Choudhury, M. E. Haque, M. A. Salam, et al., “Mortality in Severely Malnourished Children with Diarrhoea and Use of a Standardised Management Protocol,” Lancet, Vol. 353, No. 9168, 1999, pp. 1919-1922. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07499-6

- C. Lie, C. Ying, E. L. Wang, T. Brun and C. Geissler, “Impact of Large-Dose Vitamin A Supplementation on Childhood Diarrhoea, Respiratory Disease and Growth,” European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Vol. 47, No. 2, 1993, pp. 88-96.

- G. Morgan, “What, If Any, Is the Effect of Malnutrition on Immunological Competence?” Lancet, Vol. 349, No. 9066, 1997, pp. 1693-1695. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(96)12038-9

- B. A. Haider and Z. A. Bhutta, “Neonatal Vitamin A Supplementation for the Prevention of Mortality and Morbidity in Term Neonates in Developing Countries,” Cochrane Database Systymetic Review, No. 10, 2011, Article ID: CD006980. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006980

- T. A. Strand, P. R. Sharma, H. K. Gjessing, M. Ulak, R. K. Chandyo, R. K. Adhikari, et al., “Risk Factors for Extended Duration of Acute Diarrhea in Young Children,” PLoS One, Vol. 7, No. 5, 2012, Article ID: e36436. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036436

- T. Puoane, D. Sanders, A. Ashworth, M. Chopra, S. Strasser and D. McCoy, “Improving the Hospital Management of Malnourished Children by Participatory Research,” International Journal Qualitative Health Care, Vol. 16, No. 1, 2004, pp. 31-40. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzh002

- M. J. Chisti, T. Ahmed, A. S. Faruque and M. A. Salam, “Clinical and Laboratory Features of Radiologic Pneumonia in Severely Malnourished Infants Attending an Urban Diarrhea Treatment Center in Bangladesh,” Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal, Vol. 29, No. 2, 2010, pp. 174-177. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e3181b9a4d5

- J. L. Mathew, “Vitamin A Supplementation for Prophylaxis or Therapy in Childhood Pneumonia: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials,” Indian Pediatrics, Vol. 47, No. 3, 2010, pp. 255-261. doi:10.1007/s13312-010-0042-1

- J. Ni, J. Wei and T. Wu, “Vitamin A for Non-Measles Pneumonia in Children,” Cochrane Database Systemetic Review, No. 3, 2005, Article ID: CD003700.

NOTES

*Corresponding author.