Open Journal of Soil Science

Vol.04 No.13(2014), Article ID:52456,6 pages

10.4236/ojss.2014.413048

Analytical Framework Model for Capacity Needs Assessment and Strategic Capacity Development within the Local Government Structure in Tanzania

John F. Kessy1, Abiud Kaswamila2

1Department of Forest Economics, Sokoine University of Agriculture, Morogoro, Tanzania

2Department of Geography, University of Dodoma, Dodoma, Tanzania

Email: jfkessy2012@gmail.com, abagore.kaswamila6@gmail.com

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 2 October 2014; revised 1 November 2014; accepted 15 November 2014

ABSTRACT

This is a methodological paper prepared by senior academicians, researchers and consultants from renowned universities in Tanzania. The paper provides insights as to how best development agents can approach the challenge of capacity needs assessment and development of capacity building programs in the context of the local government structure in Tanzania. The paper is of original nature and is based on author’s accumulated knowledge and practice in conducting capacity assessments and developing capacity building programs in Tanzania. The paper describes what can be considered to be best practices in conducting participatory capacity assessment through consultative processes which involves most of the key actors who would be engaged in implementing proposed interventions. The paper puts forward an analytical model for capacity assessment and program development in the Tanzanian context. The main features of the model can be summarized as participatory capacity assessment, strategic capacity building program development and complementarity through synergy building with like-minded stakeholders. The operational modality for utilizing the model in developing capacity building programs which among other components has monitoring and evaluation aspects is included. It is recommended that practitioners and development agents should test the model in their working environments to realize its potential benefits including program ownership by stakeholders.

Keywords:

Capacity assessment, local government structure, Tanzania

1. Introduction

Conservation and sustainable land management is a challenge to both developed and developing countries. However, the problem is more critical in developing countries where existing capacities in terms of human, financial and other resources to deal with the challenge are very limited. To address the situation, governments and development agencies have been implementing among others capacity building interventions. A review of literature indicates that there is a considerable body of work available on capacity development [1] -[3] though very little has been published on approaches to assessing capacity needs in the Tanzanian context. Several development partners have developed capacity assessment approaches. However, most of the documented approaches do lack specificity and may not adequately capture the uniqueness of administrative structures in various countries. For example UNDP has recommended some guidelines and approaches which may assist countries in dealing with the capacity assessment challenges [4] -[6] . The UNDP guidelines introduce a note of realism by suggesting that putting the concept into practice is not a simple process and that it requires some degree of flexibility. The guidelines further make a case by arguing that the assessment should be taken within the broader socio-economic environment, as well as evaluated for specific organizations and individuals in different countries. In other words, the assessments might be undertaken in different situations and needs to be re- designed from time to time to ensure ownership, sustainability and ultimate success by the users. This makes it necessary to develop country specific models like the one presented in this paper.

A range of tools and approaches have been proposed for assessing capacity at different levels taking into consideration the enabling environment, the organizational level and individual level [1] . However, these approaches in most cases are general. Identifying the most appropriate entry point for assessing capacity and in particular the methodological part of it is critical to the realization of successful outcomes. It has been proposed [7] that the assessment should deploy a multi-dimensional approach through which the scope includes institutional issues, leadership capacities, accountability and dialogue. In this context knowledge gap assessment becomes one element of the comprehensive assessment. Logically assessment should start with the big picture at the level of enabling environment and then proceed to the lower levels. In reality, there may be many reasons why this is not only impractical but also impossible. In view of these challenges, this article tries to develop a general model that can guide capacity building interventions for conservation and development projects in the context of local government in Tanzania. The model has been tested in Kilimanjaro and Manyara regions in Tanzania and has proved to work.

2. Structure of the local government in Tanzania and SLM interventions

There are two types of local authorities in Tanzania namely rural authorities normally referred to as district councils and urban authorities that include city, municipal and town councils. Hierarchically, a district council goes down through a ward, under which exists village governments and finally the 10-house cell system. Moreover, an urban council runs down through a municipality (if the top structure is a city) under which exists the ward, then the mtaa/street government and, finally, the 10-house cell system. There are no village government structures in urban authorities [8] -[10] . The local government is administratively divided into regions. The regions are divided into districts (urban and rural authorities), which are then sub-divided into divisions, wards and villages in case of rural authorities. Urban authorities consist of city councils, municipal councils and town councils, whereas included in the rural authorities are the district councils with township council and village council authorities. The district and urban councils have autonomy in their geographic area. The former coordinates activities of wards, divisions and villages. The village and townships councils have the responsibility for formulating plans for their areas [8] -[10] .

In both village and townships there are a number of democratic bodies at lower levels to debate and oversee the implementation of local development needs. In rural system, the hamlet, the smallest unit of a village, is composed of an elected chairperson who appoints a secretary and three further members all of whom serve on an advisory committee. In urban areas the street, is the smallest unit within the ward of an urban authority. Unlike the hamlets, the street committees have a fully elected membership comprising of a chairperson, six members and an executive officer. The basic functions of the local government are [8] -[10] maintenance of law, order and good governance; promotion of economic and social welfare of the people within their areas of jurisdiction; and ensuring effective and equitable delivery of qualitative and quantitative services to the people within their areas of jurisdiction.

The head of the paid service is the district executive director in the district authorities and the town/municipal/ city director in the urban authorities. Below the director there are a number of heads of department. The departments (for provision of extension services) include personnel and administration, planning and finance, engineering/works, education and culture, trade and economic affairs; health and social welfare, cooperative and agriculture development, environment, and natural resources [10] . From the analysis of the basic structure and functions of local government authorities in Tanzania, it is apparent that most development and conservation interventions in the country are housed within the local government structures. For sustainability reasons it is strongly encouraged that all development interventions should form an integral part of the local government structure through systematic mainstreaming of project interventions into routine activities in these structures. That is why the model presented in this paper puts much emphasis on integration of SLM interventions into existing structures.

The most important, intended links between the local government and the local communities are the villages in rural areas and urban street committees in urban areas, which are designed to mobilize community participation in local development and conservation issues. Priorities for local service delivery and development projects are brought to village and/or street committees for discussion before being forwarded to the Ward Development Committee (WDC). In the rural system proposals reach the WDC via the village council.

3. The Strategic Capacity Development Model (SCDM)

As stated earlier on, the presented analytical model in this paper was tested in two projects financed by UNDP and Farm Africa in Kilimanjaro and Manyara regions respectively and proved to work well in the Tanzanian context [11] [12] . The model tries to describe the best practices in conducting participatory capacity assessment through consultative processes which involves most of the key actors who would be engaged in implementing proposed interventions and strategic development of capacity building interventions. The model provides a roadmap which can assist planners, practitioners and development partners aiming to organize and facilitate capacity building interventions in SLM practices in Tanzania and beyond. The model has three main components all being processes. These include a participatory assessment phase, the strategic program development phase and operational phase. These phases are described in this chapter.

3.1. Participatory Assessment Phase

The algorithm to follow involves four main steps namely conducting participatory consultative process; discussion with key informants in the region, districts, division, ward and level; collection of bio-data of employees and deficiencies at different levels; and holding village/community level discussions. It is envisaged that after all these steps, capacity needs including staffing and training needs for example will be determined. As put forward in literature [2] while conducting capacity needs assessment there is a challenge of developing a process which is detailed enough to allow a logical regression through the assessment but also flexible enough to respond to the wide variations in local level demands. The participatory assessment phase takes care of these propositions.

The assessment involves organizing participatory consultative meetings with local government officials and other stakeholders to develop a common understanding of the current situation, capacity gaps and needs for capacity building. The officials could include project staff, regional administration, district technical teams, collaborating NGOs/CBOs, and community level stakeholders. The process should be guided by a pre-designed checklist of issues upon which capacity gaps shall be identified. The checklist among others should solicit information regarding each stakeholders understanding of their roles in implementation of SLM interventions, staffing levels and knowledge deficiencies, status of other required capacities for effective implementation of interventions and potential partners in capacity development. The consultative process has to involve both individual and roundtable focused group discussions aimed to establish the capacity building needs at various levels within the local government structure. The assessment should pay special attention to issues of sustaining SLM interventions beyond the existing project lifespan. The assessment of local government staff capacities involves collection of bio-data of employees and their deficiencies should be undertaken at the regional, district and ward offices within the local government structure. This shall be guided by a pre-designed form so as to capture the entire list of existing staff in the region and districts, their capacities and deficiencies. The bio-data form should include data such as name of the employee, present designation, salary scale, date birth, qualification, responsibility and training needs.

The assessment at village and/community level should capture community needs and perceptions in relation to capacity building needs. Village level discussions should be held before discussions with regional and district teams. This is meant to obtain villager’s opinions first. Such discussions could be organized by the development agencies and/or consultants in collaboration with district facilitating teams. In each district representative communities/villages should be selected taking into consideration a range of criteria that ensures representation of all categories of beneficiaries in the strict sense. The cross section of representatives is meant to ensure that even the marginalized segments of the society should be involved in proposing capacity building options for their respective areas.

3.2. Strategic program development phase

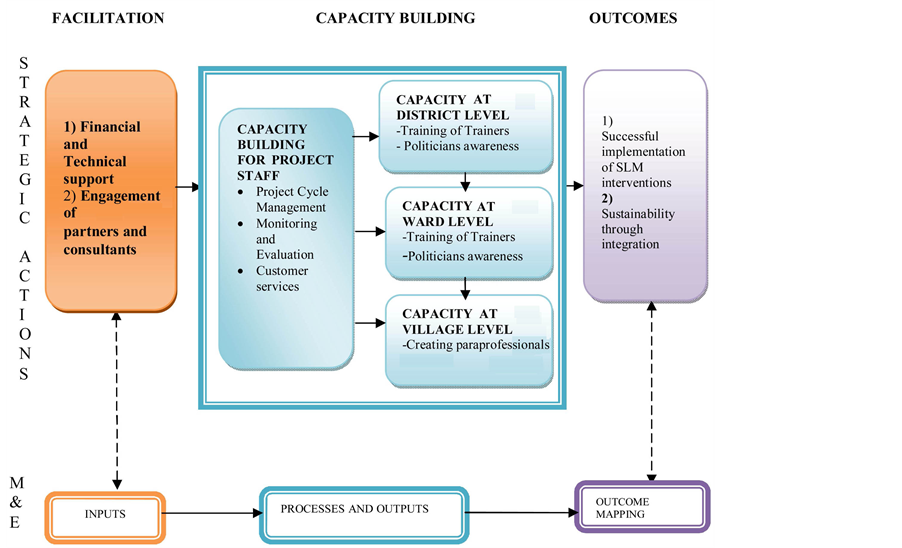

This phase is summarized in the conceptual framework model presented in this section. According to the elements presented in Figure 1, the model considers three main aspects in strategic capacity development program design. These include facilitation of capacity building, the capacity building activities and expected outcomes from the whole process. Additionally, the framework elaborates the contribution of the model to monitoring and evaluation of capacity building interventions.

According to this framework the design process assumes that facilitation of trainings and other capacity building interventions needs to be supported by the financiers of the project such district councils (DCs), municipal councils (MCs), donors and/or government institutions. The design further emphasizes that collaborating partners and service providers (e.g. consultants) need to be mobilized for the capacity building interventions as technical facilitators. Specific training activities involving project staff, district level stakeholders, ward and village level stakeholders shall form part of the strategic interventions for capacity building. It is anticipated that the capacity building for project staff shall be on cross-cutting issues which should improve their capacity to provide leadership and monitoring roles for the trainings that will be given to the other stakeholders. For both district and lower levels the strategy emphasize that the trainings should be designed for both technical officers (extension staff) to concentrate more on technical issues as well as politicians who are aimed for awareness of project results and political support. In these aspects the model takes into consideration suggestions in literature [7] that capacity development processes should be seen as collaborative learning processes linked to concrete pilot field level actions as well as evolving international policy instruments and market opportunities.

The model puts forward the anticipated outcomes from the capacity building processes. The major purpose of providing capacity building includes the realization of successful implementation of all planned interventions in the project document as well as instituting elements of sustainable implementation of introduced interventions in the respective districts. These are expected to be the major measurable outcomes of the capacity building interventions. The model draws the link between implementation of capacity building activities and project monitoring and evaluation as suggested by other scientists [7] [13] . It is envisaged that the facilitation process by different actors will use input. It is therefore expected that input indicators shall be used on the M&E section of the project to monitor and evaluate the efficiency and effectiveness of resource utilization by the project.

The model realize further that the planned capacity building activities for various actors shall involve a number of processes and yield some short term deliverables as outputs. The responsibility of the M&E section of the project in this aspect shall be to make use of process and output indicators to measure efficiency and effectiveness of the project in realizing tangible results from the processes. Of equal importance is the need for M&E section of the project to measure the magnitude at which the target population has benefited from the capacity building efforts. This can only be measured through outcome mapping as indicated in the conceptual framework of the model (figure 1).

3.3. Operational phase

The operational phase involves developing a capacity development program to bridge the identified gaps in terms of knowledge, skills and other capacities. The program should have both short term and long term capacity building interventions. In the process of developing the program, there developers need to translate the concepts and processed summarized the conceptual model (figure 1) into operational objectives and capacity building activities. In the text box bellow (figure 2) an example of the transformation of the conceptual model to operational objectives and activities is provided.

In cases where capacity building involves trainings, key considerations in the capacity building program

Figure 1. Conceptual framework of the strategic capacity development model (SCDM).

Figure 2. Strategic objectives and strategies derived from the model.

should include identification of thematic training areas, targeted trainees, duration and the proposed time of the year when it should be executed; and whether to start trainings at the beginning of the project implementation phase in order not to frustrate implementation of project activities. As suggested in literature [14] the capacity development program should aim to strike a balance between various key aspects such as technical analysis, institutional development, policy reviews/formation and conflict management.

The possibility of collaborating with other actors in pursuing SLM capacity building interventions need to be examined. The other actors in this context are like-minded organizations such as NGOs, FBOs, the private sector and other government departments whose activities complement SLM interventions in the area. Therefore, the assessment need to be done in every district based on thematic areas (e.g. irrigation, energy, agriculture etc.) and the findings summarized in a matrix which shows the identified partner, partners activities and areas where collaboration can be focused.

The operational phase should also examined additional capacities at all levels which have a bearing on implementation of SLM capacity building interventions. It is important to assess these capacities in order to inform the project management team and sponsors about factors other than capacity building which can affect performance. Among the factors which need to be examined include issues like availability of reliable transport, computers facilities and accessories, and various equipment.

4. Conclusions and recommendations

The paper has demonstrated that within the context of the local government structure in Tanzania it is possible to plan and execute capacity building interventions guided by a locally developed framework. The main features of the model can be summarized as participatory capacity assessment, strategic capacity building program development and complementarity during the implementation processes through synergy building with like- minded stakeholders.

The model is based on the philosophy of sustainability through integration into existing governance structures. As such the model largely depends on the existing local government staff within the established structures. Where capacities are low the model proposes capacity building for local government staff to be part of the package. This is because without the required capacities for example at the district and ward levels service delivery is likely to be ineffective.

The paper recommends that development agents, practitioners, local government authorities and other capacity builders should test the presented model in their local situations to generate more lessons of experience which are necessary in realizing the benefits of the model.

Acknowledgements

A word of appreciation goes to UNDP Tanzania Office and Farm Africa for giving us the opportunity to test the model in Kilimanjaro and Manyara Regions in Tanzania respectively. We are thankful to local government staff from the two regions for the cooperation which was rendered to the team during the assessments. The participation of community representatives in the assessments is also highly appreciated.

References

- Kay, M., Franks, T. and Tato, S. (2004) Capacity Needs Assessment Methodology and Processes. FAO.

- Stephen, P. and Triraganon, R. (2009) Strengthening Voices for Better Choices: A Capacity Needs Assessment Process. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

- UNDP (1997) Capacity Development. Technical Advisory Paper 2, Management, Development and Governance Division, UNDP, New York.

- Colville, J. (2008) Capacity Building Note. UNDP, USA.

- Wignaraja, K. (2009) Capacity Development: A UNDP Primer. UNDP, USA.

- UNDP (2007) Capacity Assessment Methodology. Users Guide. Capacity Development Group. Bureau for Development Policy, UNDP.

- Karen, E., Kahana, L. and Kajembe, G. (2012) REDD+ Capacity Needs Assessment in Tanzania: A Policy Brief. Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism and UN-REDD Program in Tanzania, Dar es Salaam.

- Njunwa, M. (2005) Local Government Structures for Strengthening Society Harmony in Tanzania: Some Lessons for Reflection. Proceedings of NAPSIPAG Annual Conference, Beijing, 5-7 December 2005.

- The Local Government System in Tanzania. http://www.tampere.fi/tiedostot/5nCY6QHaV/kuntajarjestelma_tansania_.pdf

- URT (1998) Policy Paper on Local Government Reform. Local Government Reform Program. Ministry of Regional Administration and Local Government. United Republic of Tanzania, Dar es Salaam.

- Kessy, J.F. (2013) Assessment of Training and Staffing Needs for Mainstreaming SLM Interventions in Kilimanjaro Region, Tanzania. Report Submitted to UNDP, Dar es Salaam.

- Kessy, J.F. and Kaswamila, A. (2013) Training Needs Assessment, Strategy and Program for Sustainable Nou Forest Ecosystem Management Project. Report Submitted to Farm Africa. Dar es Salaam and Manyara, Tanzania.

- Inna, B. (2009) Monitoring and Evaluation Capacity Building Needs Assessment. European Union and DMI Associates Consortium, Ukraine.

- Naya, S.P., Ojha, H. and Rana, S. (2010) Capacity Building Needs Assessment and Training Strategies for Grassroots REDD Stakeholders in Nepal. The Centre for People and Forests, Bangok.