Theoretical Economics Letters

Vol.4 No.1(2014), Article ID:42797,9 pages DOI:10.4236/tel.2014.41006

Transaction Cost, Specialization and Division of Labor —A General Equilibrium Analysis of Entrepreneurship under Globalization

Graduate School of Business, Nihon University, Tokyo, Japan

Email: li.ke@nihon-u.ac.jp

Copyright © 2014 Ke Li. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2014 are reserved for SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual property Ke Li. All Copyright © 2014 are guarded by law and by SCIRP as a guardian.

Received November 12, 2013; revised December 12, 2013; accepted December 19, 2013

KEYWORDS

Entrepreneurship; Division of Labor; Specialization; Transaction Cost; Globalization; Fixed Learning Cost

ABSTRACT

This paper develops a Walrasian general equilibrium model based on transaction cost and specialization to investigate the evolution and role of entrepreneurship in a competitive market under globalization. The implication of our model is straightforward that if the entrepreneurship in a competitive market under globalization is efficient, it will ensure the network and effects of division of labor can be fully exploited when the gains from the division of labor outweigh the costs of exchange between individuals of different specialization patterns with the different fixed learning costs. Hence, the entrepreneurship service in a competitive market under globalization can promote aggregate productivity by enlarging the scope for trading off network effects of the division of labor on aggregate productivity against transaction costs. To business practitioners, this model suggests that the entrepreneurship service is a key element of business viability during which a major transition took place in human activity. Besides, the improvement of the level of globalization and the general transaction efficiency coefficient will increase the level of division of labor and the per capita real income level of participants.

1. Introduction

Regarding the evolution and impact of entrepreneurship, there are many economists began recognizing the entrepreneur as early as 1700s, such as Richard Cantillon, Adam Smith, Jean-Baptiste Say, John Stuart Mill, and others [1]. Cantillon’s [2] remark on uncertainty has been widely interpreted as the first introduction of the term entrepreneurship into economic theory [3,4]. However, an analytically distinct role for the entrepreneur was first introduced by Say [5] who distinguished the revenue accruing to the activity of organizing production from which accruing to the ownership of capital. This insight was further developed by the marginal economists of the late 19th century whose recognition of the importance of the market function of combining together all the resources required for production, led them to think about the role of entrepreneur [6,7]. Unfortunately, subsequent research under the neoclassical economics, as the Walrasian general equilibrium model, was becoming its analytic core, ignored and eliminated the role of entrepreneurs from the analytical model of neoclassical theories, yet Walras himself recognized the existence of entrepreneurship as a distinct category.

Although entrepreneurship faded from neoclassical theory, it was central to the modern Austrian school and to the early Schumpeter [8,9], whose work on this issue. The focus of Austrian analysis has been the market process itself, the ways in which necessarily decentralized “tacit” knowledge about an environment that is continuously changing is socially mobilized via entrepreneurial activities. The essential functions of entrepreneurship for the Austrians, therefore, are to alter the existing framework of the means-ends nexus and to introduce novelty. The neoclassical approach, by contrast, takes the means-ends framework as given and deals only with optimization problems within given constraints. Therefore, in neoclassical theory, as Kirzner [10] rightly pointed out, “correct decision-making in this non-entrepreneurial sense, means correct calculation; faulty decision-making is equivalent to mistakes in arithmetic.” Moreover, Langlois [11] noted that, whereas the neoclassical focus is on “parametric uncertainty, a lack of complete knowledge ex ante about the values that specific variables within a given problem structure will take on ex post”. In this sense, the Austrian emphasis is on “structural uncertainty, a lack of complete knowledge on the part of the economic agent about the very structure of the economic problem that agent faces.” As a result, for the Austrian school, the essence of entrepreneurship lies to “in stepping outside existing cognitive frameworks” [11]. According to the Austrian school, the Misesian-Kirznerian entrepreneur use the notion of “human action” and is alert to previously unnoticed opportunities and acts as an arbitrageur; and the Schumpeterian entrepreneur changes the framework by innovating.

Kirzner used the Misesian notion of “human action” [12] to analyze the entrepreneurial role, which is “the human-action concept, unlike that of allocation and economizing, does not confine the decision-maker (or the economic analysis of his decisions) to a framework of given ends and means” [13,14]. The Kirznerian entrepreneur notices “profit opportunities that exist because of the initial ignorance of the original market participants and that have persisted because of their inability to learn from experience” [13,15]. Joseph A. Schumpeter [8] explicitly recognized and defined the role and activities that the entrepreneur contributed to the economic system. In the Theory of Business Enterprise, Schumpeter [9] stated that the entrepreneur is pecuniary, and in an institutional system of market economy the participants are all pecuniary, and being pecuniary means seeding payment of money or expecting money from efforts. Besides, Schumpeter [9] descried the entrepreneur as a creative innovator and an innovation is as the commercialization of innovation. If this is the case, then the entrepreneur are with the creative talents and not a product or result of particularly given institutional system [16]. However, the efforts, activities, and results of the entrepreneur in bringing about innovations will surface differently in each different institutional system.

Nowadays, the term “entrepreneurship” in economic theory is used almost exclusively to refer to the innovative or the market equilibrating activities that are performed by individuals or firms in conditions of uncertainty. Baumol [17] distinguishes between productive, unproductive and destructive entrepreneurship, defined in terms of whether the activity adds to, redistributes or subtracts from net output. However, it is possible to go beyond Baumol’s definition in terms of conventional measures of net output by introducing wider social considerations. A value system that emphasizes the importance for the quality of life of sustainability, viable local communities, social stability and considerations of equity may assess different types of entrepreneurial activity and innovation very differently from a value system emphasizing simply additions to net output [18]. As world economies evolve, the entrepreneur quickly surfaces to make changes in economic products and economic activities. These changes are not necessarily a result of a given institutional system but rather the newly allotted freedom given to the entrepreneur in order to bring about activities and goods that meet society’s wishes and needs [19]. Mondal defined these entrepreneurs as the path breakers in a country where there are significant obstacles to the development and marketing of new products [20]. More logically, these entrepreneurs would be driven, in a given institutional system, by the desire to creatively bring about new products, new production processes, new business patterns and new economic institutional systems to improve material well-being to the members of society “by endogenously with entrepreneurs who destroy static economic circular flow by introducing new combinations” [21].

Therefore, neither the neoclassical school nor the Austrian school discusses the question of how the entrepreneurial function is embedded in different types of economic structures or business patterns, at both micro and macro levels, thus leaving the relationship between economic structures and entrepreneurial success un-theorized. There is a large literature on entrepreneurship, yet it seldom addresses the relationship between economic structures or business patterns and entrepreneurship based on transaction cost, division of labor and specialization. More recently, Yang [22] theory appeared to provide a promising framework for revitalizing the concept of entrepreneurship by situating entrepreneurial activity and related economic structures or business patterns, and re-conceiving it as a collective social process.

According to Li et al. [23,24], “a competitive market under globalization” in this paper can be defined as the market and production resources can be fairly mobilized among countries and regions, and also the general market mechanism and rules are prevailing during the process. This paper attempts to analyze the relationship between entrepreneurial activity and type of economic structures or business patterns, with special emphasis given to the social network of division of labor, the level of specialization, and transaction efficiency. The aim of this paper is to clarify the relationship between entrepreneurship and different types of economic structures or business patterns of a competitive market under globalization. This paper proposes that entrepreneurship and transaction cost are fundamentally interrelated in the determination of the level of division of labor and specialization, and identifies the key mechanisms of their co-evolution. Specifically, we argue that the entrepreneurship would be driven, in a given institutional system, by the desire to creatively bring about new products, new production processes, new business patterns and new economic institutional systems to improve material well-being to the members of society. Furthermore, we argue that there are particular evolutionary mechanisms that shape economic structures over time. The radical transformations in the conduct of business and the fundamental restructuring of existing business pattern and operation are the different aspects of entrepreneurship. In this paper, it will investigate the evolution and impact of entrepreneurship on the market exchange and restructuring economic institutional systems.

2. The Framework of General Equilibrium Model of Transaction Cost, Specialization and Division of Labor with Entrepreneurship

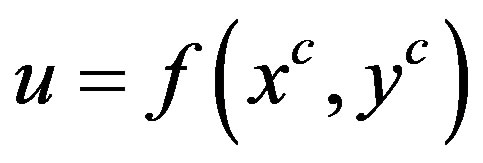

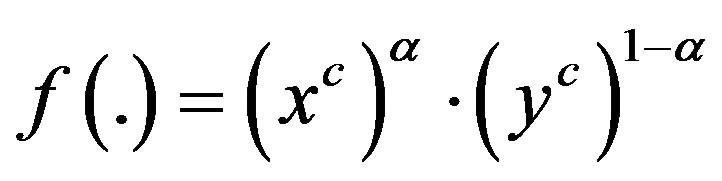

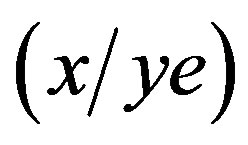

Following the infra-marginal analysis [22], we consider a large economy with a continuum of consumer-producers of mass M. This assumption implies that population size is very large, and it can avoid an integer problem of the numbers of different specialists, which may lead to non-existence of equilibrium with the division of labor. Each consumer-producer has identical, non-satiated, continuous, and rational preference represented by the following utility function:

, (1)

, (1)

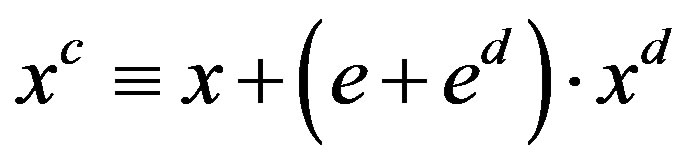

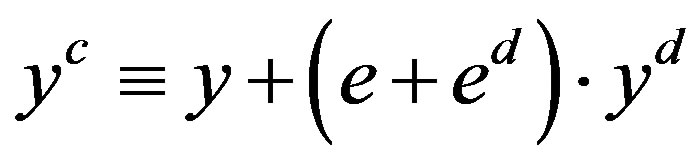

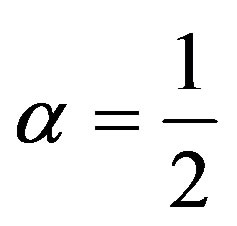

where  and

and  are the amounts of the two final goods that are consumed, x and y are the amounts of the two goods that are selfprovided, xd and yd are the amounts of the two goods that are purchased from the market. Moreover,

are the amounts of the two final goods that are consumed, x and y are the amounts of the two goods that are selfprovided, xd and yd are the amounts of the two goods that are purchased from the market. Moreover,  is assumed continuously increasing and quasi-concave, and for simplicity without losing generality, it is also assumed here that

is assumed continuously increasing and quasi-concave, and for simplicity without losing generality, it is also assumed here that  and for simplicity without losing generality we assume

and for simplicity without losing generality we assume . Besides,

. Besides,

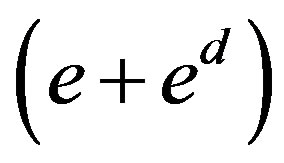

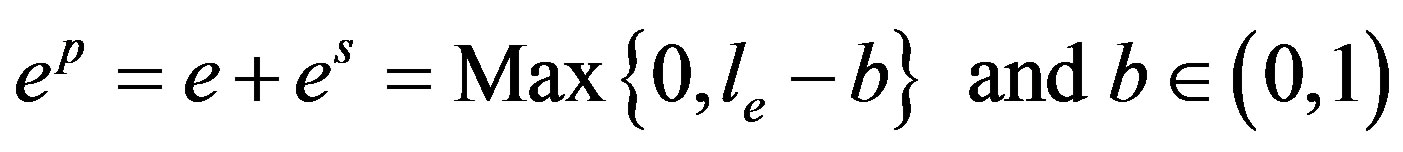

represents the level and efforts of entrepreneurship service which can come from self-provided management knowledge or skills, or by purchasing the entrepreneurship services from the market, like the consulting services or hiring the professional entrepreneur. The amount of entrepreneurship service is shown as,

represents the level and efforts of entrepreneurship service which can come from self-provided management knowledge or skills, or by purchasing the entrepreneurship services from the market, like the consulting services or hiring the professional entrepreneur. The amount of entrepreneurship service is shown as,

, (2)

, (2)

where ep is the total amount of the entrepreneurship services produced; es is the amount of the entrepreneurship services sold to the market; and b is the fixed learning cost of entrepreneurship services, and is related to the degree of economies of specialization.

Each consumer-producer’s production functions are:

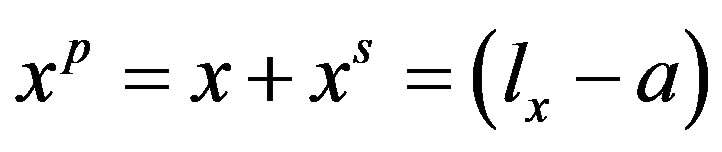

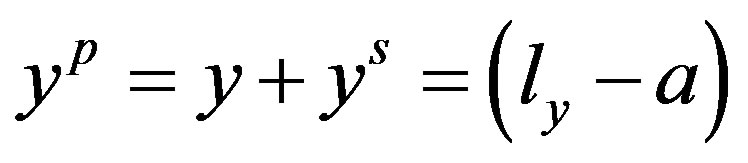

, (3)

, (3)

and

and .

.

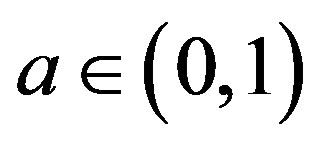

Here, xp and yp are the amounts of the two final goods produced, xs and ys are the amounts of the two final goods sold; a is the fixed learning and training costs in producing final goods, and is related to the degree of economies of specialization.

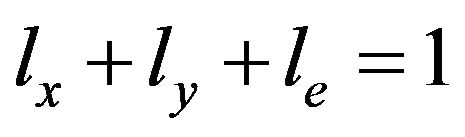

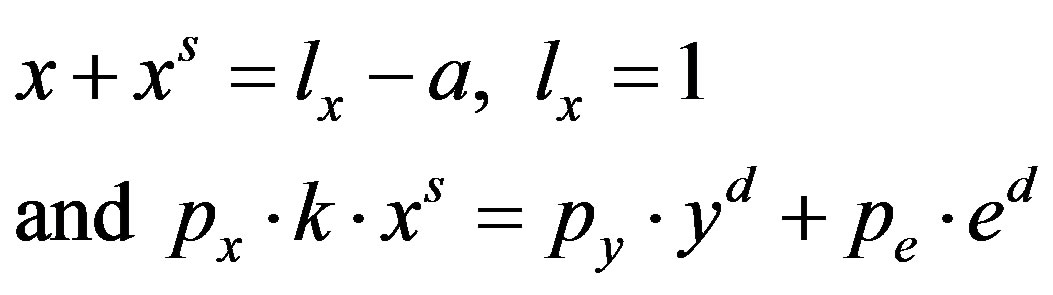

The endowment constraint for each individual is assumed to be endowed with one unit of working time, and is given as follows:

, (4)

, (4)

where lx, ly, and le are the amount of labor allocated to the production of these goods and services. This system of production implies that each individual’s labor productivity increases as she narrows down her range of production activities. As shown by Yang [22], the aggregate production schedule for three individuals discontinuously jumps from a low profile to a high profile as each person jumps from producing three goods to a production pattern in which at least one person produces only one good (specialization). The difference between the two aggregate production profiles is considered as positive network effects of division of labor on aggregate productivity. This network effect implies that each person’s decision of her level of specialization, or gains from specialization, depends on the number of participants in a large network of division of labor, while this number is determined by all individuals’ decisions in choosing their levels of specialization (so-called “the Young theorem”, see [25]). Since economies of specialization is individual specific (learning by doing must be achieved through individual specific practice and cannot be transferred between individuals), labor endowment constraint is specified for each individual, so that increasing returns are localized.

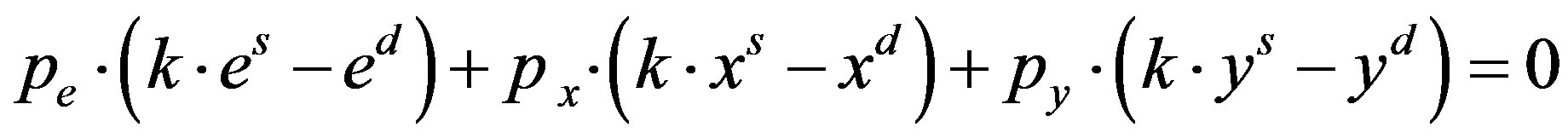

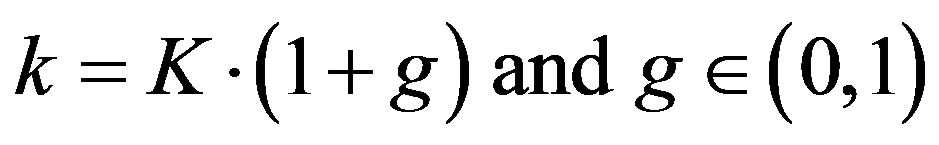

The budget constraint for an individual is,

. (5)

. (5)

. (6)

. (6)

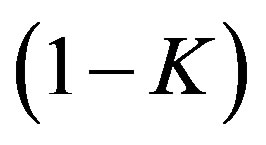

Here, px and py are the prices of good x and y; and pe is the price for purchasing entrepreneurship service. Besides, K is a general transaction efficiency coefficient, which represents the conditions governing transactions. K relates to transportation conditions and the general institutional environment that affects transaction efficiency. Fraction  of a good sold disappears in transit due to an iceberg transaction cost. Besides, we let g representing the level of Globalization, which can be evaluated by the mobility of commodity and resources, plus the standardization and generality of market mechanism and rules. Hence, k is the transaction efficiency coefficient with the concern of the level of Globalization.

of a good sold disappears in transit due to an iceberg transaction cost. Besides, we let g representing the level of Globalization, which can be evaluated by the mobility of commodity and resources, plus the standardization and generality of market mechanism and rules. Hence, k is the transaction efficiency coefficient with the concern of the level of Globalization.

Due to the continuum number of individuals and the assumption of localized increasing returns in this large economy, a Walrasian regime prevails in this model. The specification of the model generates a trade-off between economies of division of labor and transaction costs. The decision problem for an individual involves deciding on what and how much to produce for selfconsumption, to sell and to buy from the market. In other words, the individual chooses nine variables xi,  ,

,  , yi,

, yi,  ,

,  , ei,

, ei,  ,

, . Hence, there are 29 = 512 possible corner and interior solutions.

. Hence, there are 29 = 512 possible corner and interior solutions.

The set of candidates for each individual’s optimum decision includes many corner and interior solutions. In order to narrow down the list of the candidates, Yang [22] used the Kuhn-Tucker conditions to establish the following lemma:

LEMMA 1: Each individual sells at most one good, but does not buy and sell the same good, nor buys and self-provides the same good at the same time.

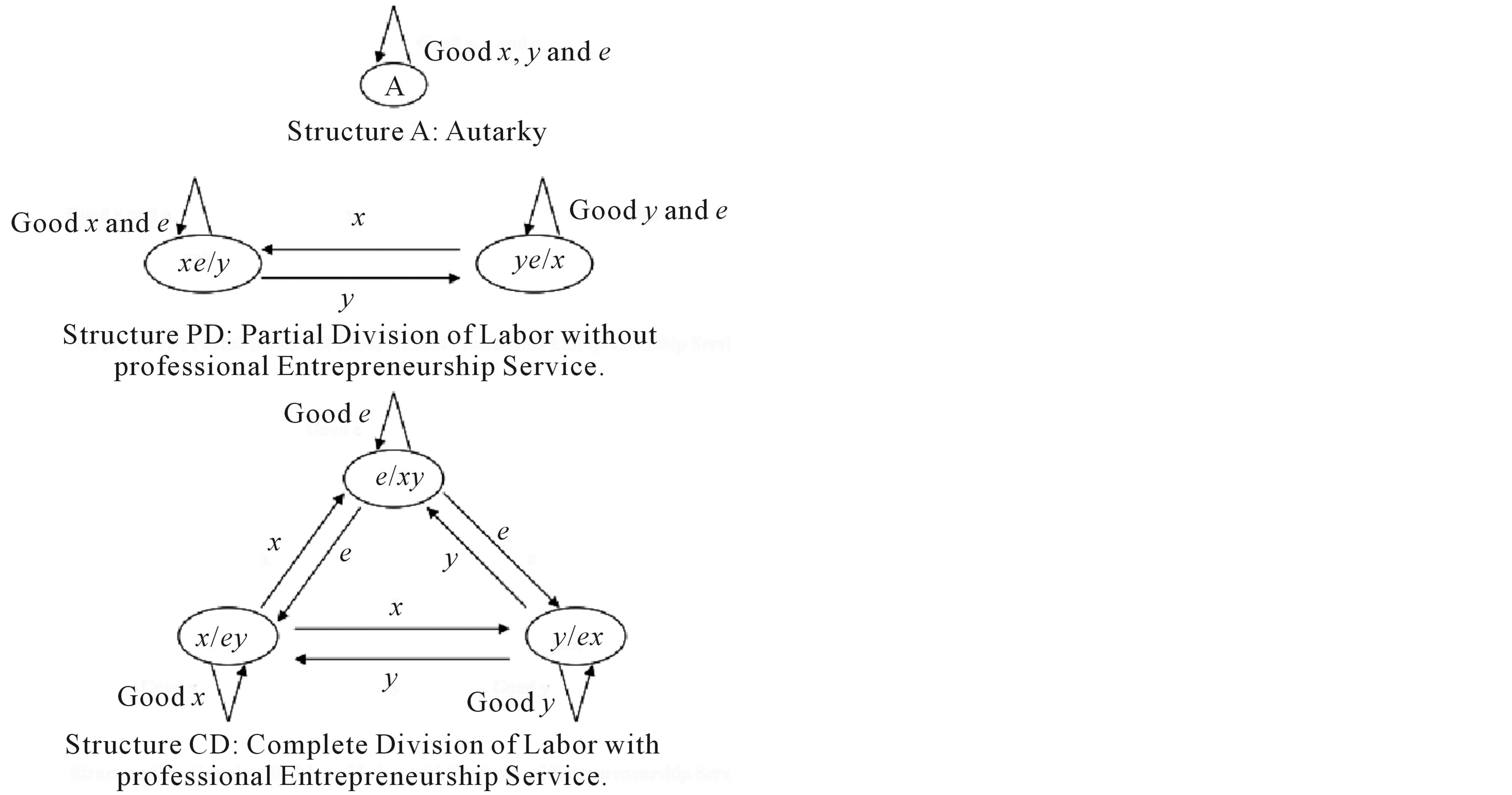

We define a “Configuration” as a combination of zero and positive variables which are compatible with Lemma 1. When labor trade and bundling are allowed, there are six configurations from which the individuals can choose. A combination of all individual’s configurations constitutes a “Market Structure” (or “Structure” for short). After examining all structures that might occur in equilibrium, there will be three types of structures: 1) Structure A: Autarky; 2) Structure PD: Partial Division of Labor with Professional Entrepreneurship Service; 3) Structure CD: Complete Division of Labor with Professional Entrepreneurship Service (see Figure 1).

According to Yang [22], a general equilibrium exists for a general class of the models of which the model in this paper is a special case under the assumptions that the

Figure 1. Configurations and market structures.

set of individuals is a continuum, preferences are strictly increasing and rational; and both local increasing returns and constant returns are allowed in production and transactions. A general equilibrium in this model is defined as a set of relative prices of goods and all individuals’ labor allocations and trade plans, such that, 1) Each individual maximizes her utility, that is, the consumption bundle generated by her labor allocation and trade plan maximizes her utility function for given prices; 2) All markets clear.

Since the optimum decision is always a corner solution and the interior solution is never optimal according to Lemma 1, we cannot use standard marginal analysis to solve for a general equilibrium. We adopt a three-step approach to solving for a general equilibrium [22]. The first step is to narrow down the set of candidates for the optimum decision and to identify configurations that have to be considered. We can identify structures from compatible combinations of configurations. In the second step, each individual’s utility maximization decision is solved for a given structure. The utility equalization condition between individuals choosing different configurations and the market clearing conditions are used to solve for the relative price of traded goods and numbers (measure) of individuals choosing different configurations. The relative price and numbers, and associated resource allocation are referred to as corner equilibrium for this structure. General equilibrium occurs in a structure where, given corner equilibrium relative prices in the structure, no individuals have an incentive to deviate from their chosen configurations in this structure. In the second step, we can substitute the corner equilibrium relative prices into the utility function for each constituent configuration in the given structure to compare the utility between this configuration and any alternative configurations. This comparison is called a total costbenefit analysis. The total cost-benefit analysis yields the conditions under which the utility in each constituent configuration of this structure is not smaller than any alternative configuration. With the existence theorem of general equilibrium proved by Yang [22], we can completely partition the parameter space into subspaces, within each of which the corner equilibrium in a structure is a general equilibrium. As parameter values shift between the subspaces, the general equilibrium will discontinuously jump between structures. The discontinuous jumps of structure and all endogenous variables are called infra-marginal comparative statics of general equilibrium. The three steps constitute an infra-marginal analysis.

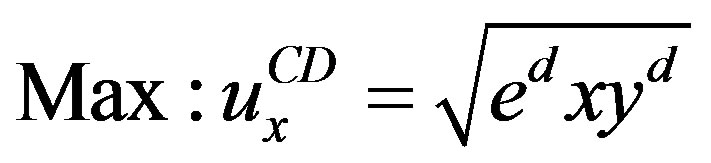

Next, for the purpose of simplicity we use one example to illustrate how marginal analysis can be conducted to solve for the corner solution in each configuration and for the corner equilibrium in each structure. The example is the corner equilibrium of structure CD which involves the division of the population among configurations ,

,  and

and .

.

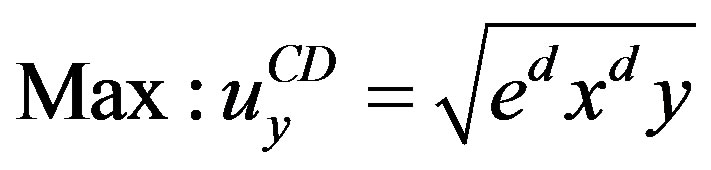

In Structure CD, the decision problem for an individual choosing configuration  is:

is:

, (7)

, (7)

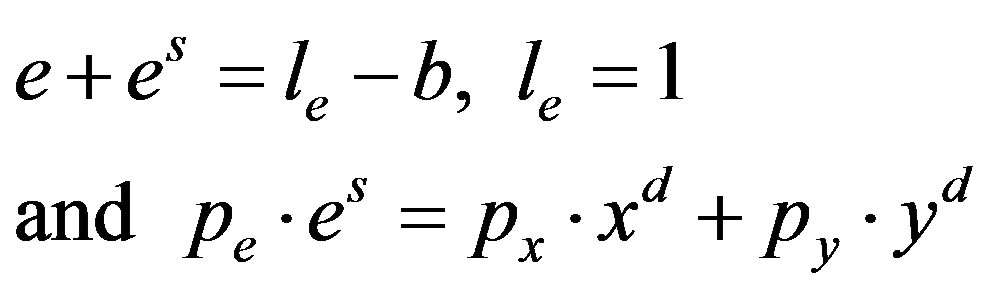

subject to the following constraints,

. (8)

. (8)

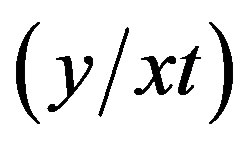

Similarly, the decision problem for an individual choosing configuration  is:

is:

, (9)

, (9)

which is subject to the following constraints,

. (10)

. (10)

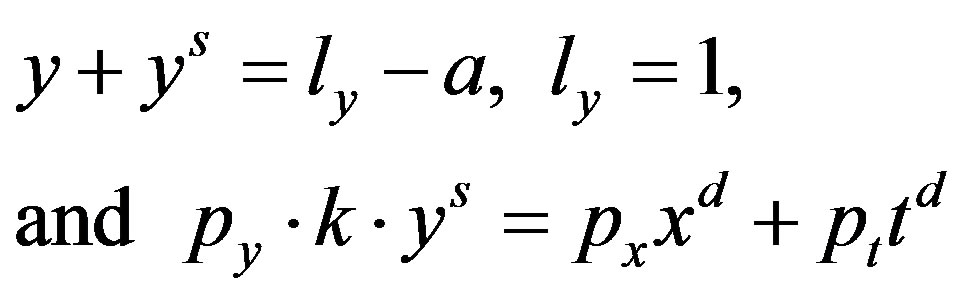

The professional individual who providing the entrepreneurship service is denoted by configuration , and has the following decision problem:

, and has the following decision problem:

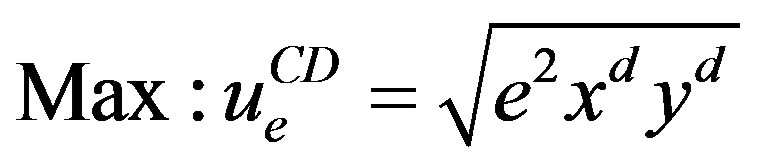

, (11)

, (11)

and is subject to the constraints:

. (12)

. (12)

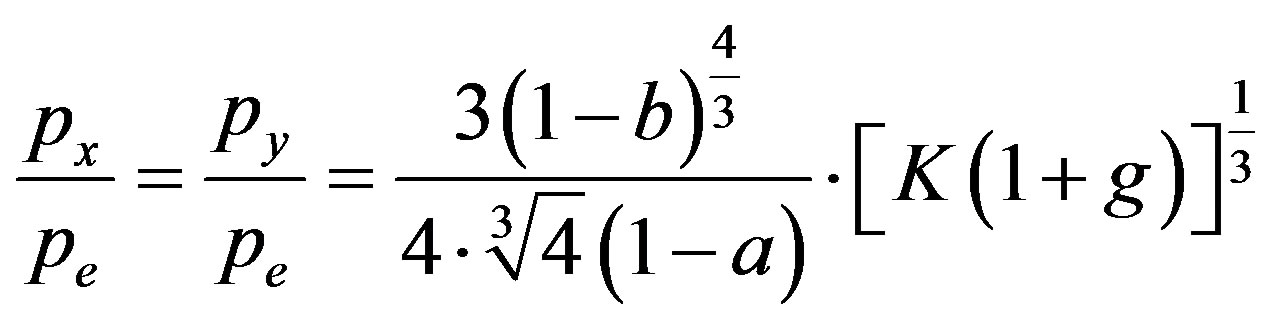

The two utility equalization conditions across three configurations yield the corner equilibrium relative prices of goods x, y over service t.

. (13)

. (13)

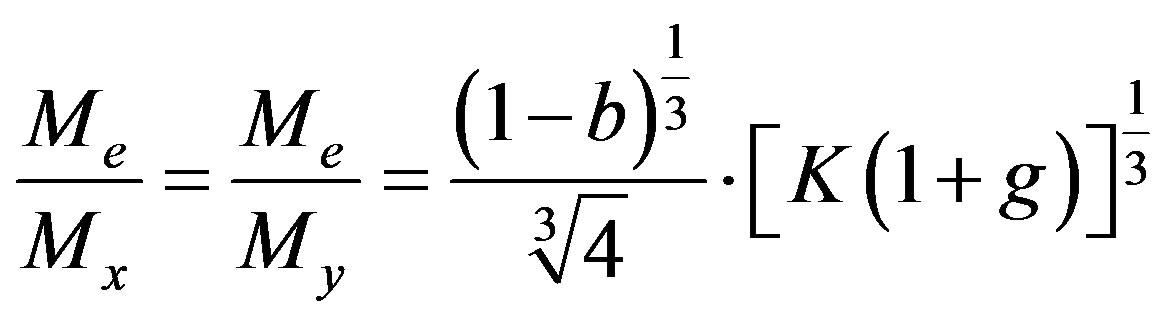

The two independent market clearing conditions for goods x and y, yield the corner equilibrium relative numbers of specialists producing goods x, y, and e,

, (14)

, (14)

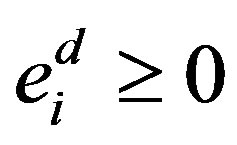

where Mx is the number of x specialist-employers choosing ; My is the number of specialist producers of good y choosing

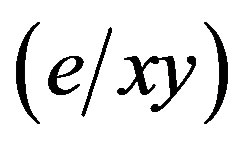

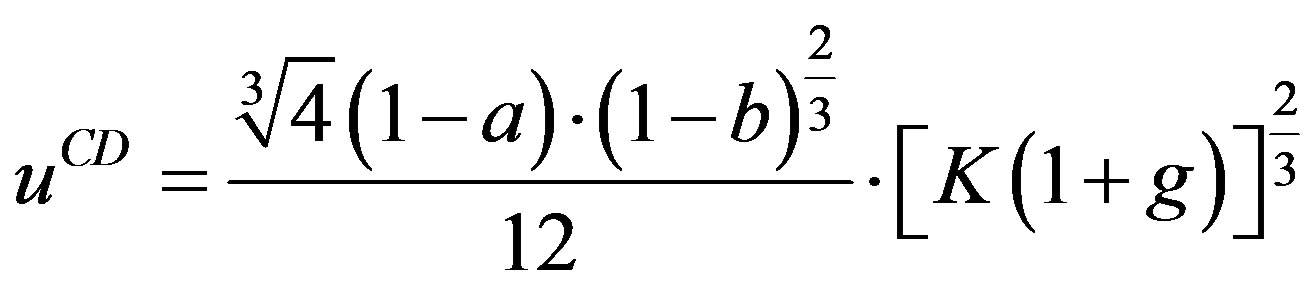

; My is the number of specialist producers of good y choosing ; and Me is the number of people who provide entrepreneurship service, which also can indicate of the scale of entrepreneurship service the market demanded. The relative numbers of specialists, together with population size identity Mx + My + Me = M, will yield the corner equilibrium numbers of different specialists. Plugging relative prices into an indirect utility function of any of three configurations yields the per capita real income in structure CD as:

; and Me is the number of people who provide entrepreneurship service, which also can indicate of the scale of entrepreneurship service the market demanded. The relative numbers of specialists, together with population size identity Mx + My + Me = M, will yield the corner equilibrium numbers of different specialists. Plugging relative prices into an indirect utility function of any of three configurations yields the per capita real income in structure CD as:

. (15)

. (15)

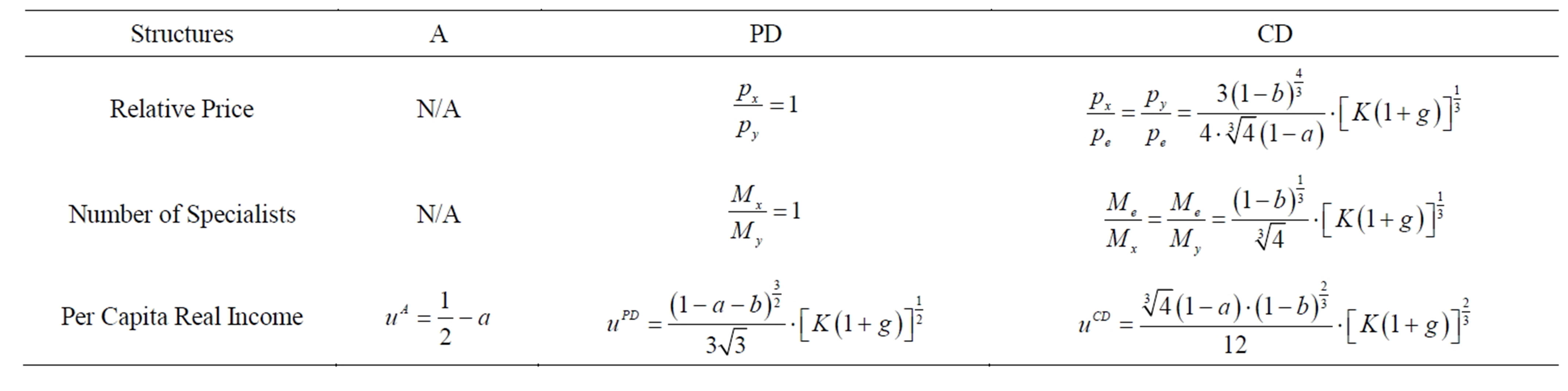

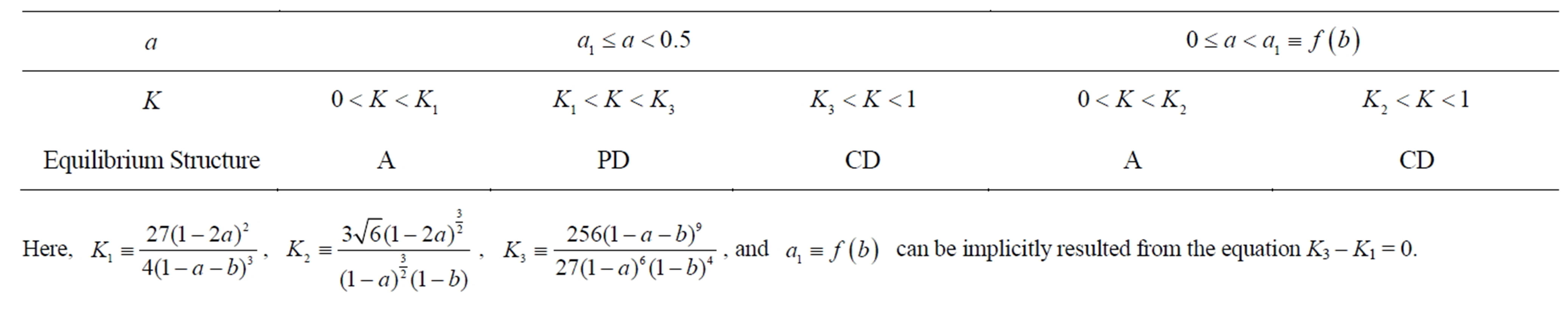

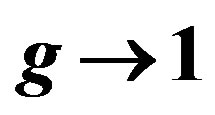

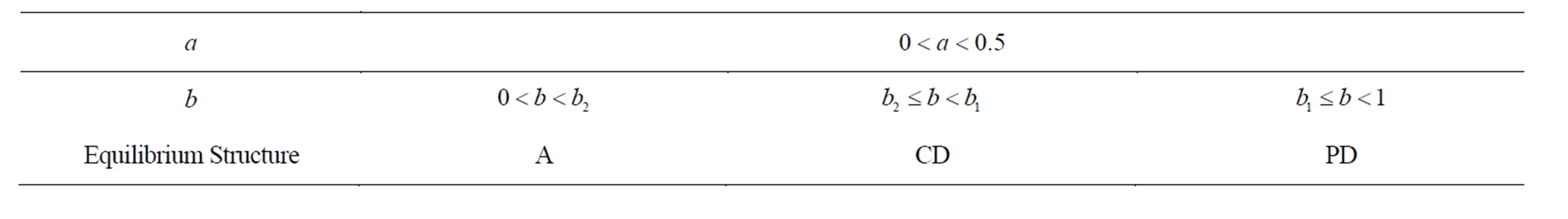

Following this above procedure, we can solve the corner equilibria for all three structures. Information about such solutions of corner equilibria from three economic structures is summarized in the following Table 1.

3. General Equilibrium and Its Infra-Marginal Comparative Statics Analysis

We now consider the third step of infra-marginal analysis. Based on the first two steps of the infra-marginal analysis, we will partition the parameter space into subspaces within each of which a particular structure occurs in equilibrium.

For any given structure, each individual can plug the corner equilibrium prices into her indirect utility functions for all configurations including those that are not in this structure. She has no incentive to deviate from a constituent configuration in this structure if this configuration generates a utility value that is not lower than in any alternative configurations under the corner equilibrium values of prices in this structure. Each individual can conduct such total cost-benefit analysis across configurations. Let indirect utility in each constituent configuration not be smaller than in any alternative configurations under the corner equilibrium prices in this structure. We can obtain a system of semi-inequalities that involves only parameters. This system of semi-inequalities defines

Table 1. The corner equilibria of three market structures.

a parameter subspace within which the corner equilibrium in this structure is the general equilibrium. This total cost-benefit analysis is very tedious and cumbersome. Fortunately, the Yao Theorem ([22], chapter 6) can be used to simplify this total cost-benefit analysis. It states that in an economy with a continuum of ex ante identical consumer-producers having rational and convex preferences and production functions displaying individual specific economies of specialization, a Walrasian general equilibrium exists and it is the Pareto optimum corner equilibrium. Here the Pareto optimum corner equilibrium is a corner equilibrium that generates the highest per capita real income. Since our model in this paper is a special case of the above mentioned general class of models, the individuals have no incentive to deviate from their chosen constituent configurations in a structure if and only if individuals’ corner equilibrium utility value in this structure is not lower than that in any other corner equilibria. With the Yao theorem, we can then compare corner equilibrium per capita real incomes across all structures, and the comparison partitions the four-dimension  parameter space into several subspaces, within each of which one corner equilibrium is the general equilibrium. As parameter values shift between different subspaces, the general equilibrium discontinuously jumps between corner equilibria. This is referred to as infra-marginal comparative statics of general equilibrium. The results are shown at Tables 2 and 3.

parameter space into several subspaces, within each of which one corner equilibrium is the general equilibrium. As parameter values shift between different subspaces, the general equilibrium discontinuously jumps between corner equilibria. This is referred to as infra-marginal comparative statics of general equilibrium. The results are shown at Tables 2 and 3.

Moreover, when , the equilibrium structure will always be Structure A: Autarky.

, the equilibrium structure will always be Structure A: Autarky.

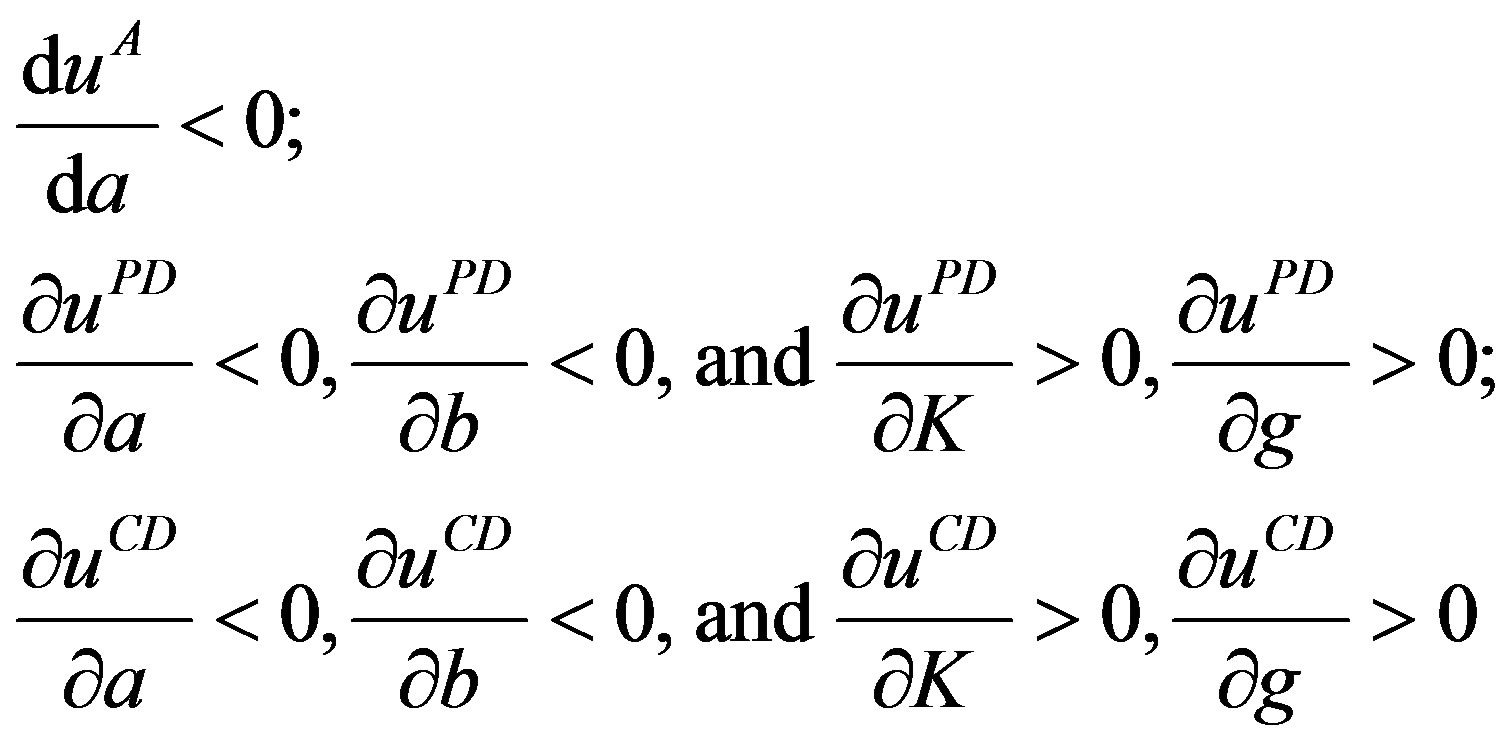

Next, let’s examine the change of per capita real income in response to changes in transaction efficiency, in fixed learning cost, and entrepreneurship service, which results in the following inequalities,

, (16)

, (16)

which imply that to improve the per capita real income level, we can either by increasing the transaction efficiency, or by reducing the fixed learning cost of the final goods or of the entrepreneurship service. Moreover, from Tables 2, 3, and the inequalities of (7), it also indicates that, if the transaction efficiency of entrepreneurship service from business pattern PD to the new one CD is improved, then the real income level will be increased when the transformation is completed. However, if the fixed learning cost of final goods and/or the fixed learning cost of entrepreneurship service are too high, then people will prefer self-provide the entrepreneurship service instead of purchasing from the market, and the social network of division of labor and the level of specialization will also retain at lower level. Besides, the improvement of the level of globalization and the general transaction efficiency coefficient will increase the level of division of labor and also the per capita real income level.

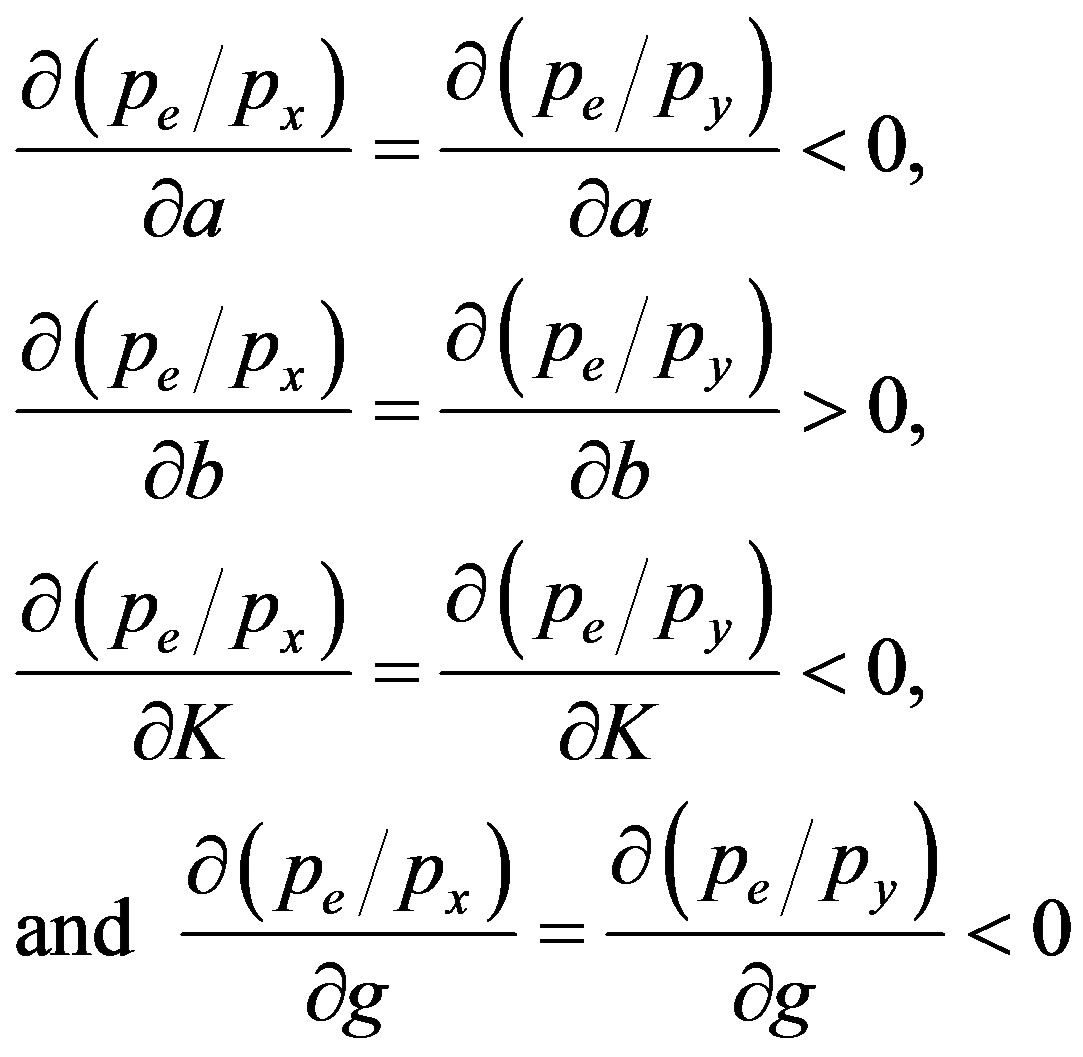

Similarly, if we examine the change of relative prices with the changes in transaction efficiency, in the fixed learning cost of final goods, and in the fixed learning cost of entrepreneurship service, there will be the following results,

Table 2. General equilibrium and its infra-marginal comparative statics when  and

and .

.

Table 3. General equilibrium and its infra-marginal comparative statics when  and

and .

.

. (17)

. (17)

These inequalities imply there are negative correlation between relative price  or

or  with the transaction efficiency and the fixed learning cost of final goods, while there is a positive correlation with the fixed learning cost of entrepreneurship service. Hence, if the transaction efficiency is improved and the fixed learning cost of entrepreneurship service is declining, then the price of entrepreneurship service can be cheaper.

with the transaction efficiency and the fixed learning cost of final goods, while there is a positive correlation with the fixed learning cost of entrepreneurship service. Hence, if the transaction efficiency is improved and the fixed learning cost of entrepreneurship service is declining, then the price of entrepreneurship service can be cheaper.

Following Yang [22], it can be shown that a general equilibrium in our model is always Pareto optimal as long as nobody can block free entry into any sector and nobody can manipulate relative prices and numbers of specialists. This first welfare theorem in our model with entrepreneurship and endogenous network size of division of labor implies that the very function of market is to coordinate impersonal networking decisions in restructuring existing business pattern, and to fully utilize network effects of division of labor on aggregate productivity, net of transaction costs. Entrepreneurship in a competitive market under globalization is an effective way to promote division of labor and productivity progress. The above analysis leads to the following proposition.

Propositions:

1) As transaction efficiency is improved, the equilibrium level of division of labor increases, thereby the real income level is also increased. Transaction efficiency has a negative correlation with the relative price of the entrepreneurship service in term of the final goods.

2) If the fixed learning cost of entrepreneurship service is getting lower, it will simultaneously improve the real income level, promote the level of division of labor and productivity progress, and offer the flexibility to charge cheaper price for the entrepreneurship service.

3) The fixed learning cost of final goods has a negative impact on per capita real income, and has a negative correlation with the relative price of the entrepreneurship service in term of the final goods.

4) The improvement of the level of globalization and the general transaction efficiency coefficient will increase the level of division of labor and also the per capita real income level.

The above propositions imply, as the fixed learning cost of entrepreneurship service declined, there will be more flexibility and space to charge cheaper price for this service, yet the real income level is still increasing. It further proves Schumpeter’s description, which regards the entrepreneur as a creative innovator and an innovation is as the commercialization of innovation. These entrepreneurs would be driven, in a given institutional system, by the desire to creatively bring about new products, new production processes, new business patterns and new economic institutional systems to increase the per capita real income. It also helps to explain the reason why along the commercialization and modernization of human society, there are substantially increasing amount of professional entrepreneurship service available for business world, and it has become more affordable for more business companies. Besides, Proposition 1 also indicates that with the improvement of transaction efficiency, the professional entrepreneurship service is more preferred and profitable, which is probably the reason why so many companies are presently enthusing about purchasing the professional entrepreneurship service from the consulting firms or by hiring the professional entrepreneur. Moreover, also with the improvement of transaction efficiency and commercialization, the professional entrepreneurship service will bring about new business patterns and new economic institutional systems to improve the well-being to the members of society. Besides, the improvement of the level of globalization and the general transaction efficiency coefficient will increase the level of division of labor and also the per capita real income level.

Since the general equilibrium in our model is always Pareto optimal, the policy implication of our model is straightforward. If the entrepreneurship in a competitive market under globalization is efficient, it will ensure that network effects of division of labor can be fully exploited when the gains from the division of labor outweigh the costs of exchange between individuals of different specialization patterns with the different fixed learning costs. Hence, the entrepreneurship service in a competitive market under globalization can promote aggregate productivity by enlarging the scope for trading off network effects of the division of labor on aggregate productivity against transaction costs.

4. Concluding Remarks

This paper develops a Walrasian general equilibrium model based on transaction cost and specialization to investigate the evolution and role of entrepreneurship in a competitive market under globalization. Since the general equilibrium in our model is always Pareto optimal as long as nobody can block free entry into any sector and nobody can manipulate relative prices and numbers of specialists. It further proves Schumpeter’s description [8,9], that the entrepreneurship service would be driven by the desire to creatively bring about new products, new production processes, new business patterns and new economic institutional systems to increase the per capita real income. It also explains the reason why along the commercialization and modernization of human society, there are substantially increasing amount of professional entrepreneurship service available for business world, and also becoming more affordable for more business companies. With the improvement of transaction efficiency, the professional entrepreneurship service is more preferred and profitable, and the professional entrepreneurship service will bring about new business patterns and new economic institutional systems to improve the well-being to the members of society. If the entrepreneurship in a competitive market under globalization is efficient, it will ensure that network effects of division of labor can be fully exploited when the gains from the division of labor outweigh the costs of exchange between individuals of different specialization patterns with the different fixed learning costs. Hence, the entrepreneurship service in a competitive market under globalization can promote aggregate productivity by enlarging the scope for trading off network effects of the division of labor on aggregate productivity against transaction costs.

To business practitioners, this model suggests that the entrepreneurship service is a key element of business viability during which a major transition took place in human activity. The improvement of the level of globalization and the general transaction efficiency coefficient will also increase the level of division of labor, as well as the per capita real income level and well beings among participants.

Acknowledgements

The author appreciates the helpful comments from Paul Milgrom, Eric Maskin, Aris Spanos, Xiaokai Yang, Yew-Kwang Ng, and the participants at the seminars on held at St. Joseph’s University, University of Pennsylvania, Nanjing University, University of Hawaii, and EastWest Center at Hawaii. The author is responsible for the remaining errors.

REFERENCES

- B. A. McDaniel, “Entrepreneurship and Innovation: An Economic Approach,” M. E. Sharpe, New York, 2002.

- R. Cantillon, “Essay on the Nature of Trade,” Macmillan, London, 1755, Reprinted in 1931.

- M. Casson, “Entrepreneur,” In: J. Eatwell, M. Milgate and P. Newman, Eds., The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, Macmillan, London, 1987, pp. 151-153.

- R. F. Hébert and A. N. Link, “The Entrepreneur: Mainstream Views and Radical Critiques,” 2nd Edition, Praeger, New York, 1988.

- J. B. Say, “A Treatise on Political Economy; or the Production, Distribution, and Consumption of Wealth,” 6th Edition), Augustus M. Kelley, New York, 1803, Reprinted in 1964.

- A. Marshall, “Principles of Economics,” 8th Edition, Macmillan, New York, 1920, Reprinted in 1949.

- C. Menger, “Principles of Economics,” Free Press, Illinois, 1871, Reprinted in 1950.

- J. A. Schumpeter, “The Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest, and the Business Cycle,” Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1911.

- J. A. Schumpeter, “The Theory of Business Enterprise,” Charles Scibner’s Sons, New York, 1912.

- I. M. Kirzner, “The Primacy of Entrepreneurial Discovery,” In: I. M. Kirzner, Eds., The Prime Mover of Progress (Reading 23), Institute of Economic Affairs, London, 1980, pp. 3-30.

- R. N. Langlois, “Risk and Uncertainty,” In: P. J. Boettke, Ed., The Elgar Companion to Austrian Economics, Edward Elgar, Aldershot, 1994, pp. 118-122. http://dx.doi.org/10.4337/9780857934680.00026

- L. V. Mises, “Human Action: A Treatise on Economics,” Yale University Press, New Haven, 1949.

- I. M. Kirzner, “Competition and Entrepreneurship,” University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1973.

- I. M. Kirzner, “Creativity and/or Alertness: A Reconsideration of the Schumpeterian entrepreneur,” Review of Austrian Economics, Vol. 11, No. 1-2, 1999, pp. 5-17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1007719905868

- I. M. Kirzner, “Entrepreneurship,” In: P. J. Boettke, Eds., The Elgar Companion to Austrian Economics, Edward Elgar, Aldershot, 1994, pp. 103-110. http://dx.doi.org/10.4337/9780857934680.00024

- B. A. McDaniel, “Institutional Destruction of Entrepreneurship through Capitalist Transformation,” Journal of Economic Issues, Vol. 37, No. 2, 2003, pp. 495-501.

- W. J. Baumol, “Entrepreneurship, Management and the Structure of Payoffs,” The MIT Press, Cambridge, 1993.

- P. Devine, “The Institutional Context of Entrepreneurial Activity,” In: F. Adaman and P. Devine, Eds., Economy and Society: Money, Capitalism and Transition, Black Rose Books, Montreal, 2002, pp. 440-454.

- W. A. Waters, “The Social Economics of Joseph A. Schumpeter,” Review of Social Economics, Vol. 52, No. 4, 1994, pp. 256-265. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/758523323

- W. I. Mondal, “Micro-Credit and Micro-Entrepreneurship,” Academic Press and Publications, Ltd., Dhaka, 2002.

- K. Thanawola, “Schumpeter’s Theory of Economic Development and Development Economics,” Review of Social Economy, Vol. 211, No. 4, 1994, pp. 361-362.

- X. K. Yang, “Economics: New Classical versus Neoclassical Frameworks,” Blackwell, Cambridge, 2001.

- K. Li and S. T. Yao, “A Mixed Nash-Walrasian Equilibrium Model with Endogenous Stealing and Endogenous Specialization,” Pacific Economic Review, Vol. 9, No. 4, 2004, pp. 347-356. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0106.2004.00254.x

- K. Li, C. N. Chu, D. F. Hung, C. C. Chang and S. L. Li, “Industrial Cluster, Network and Production Value-Chain: A New Framework for Industrial Development Based on Specialization and Division of Labour,” Pacific Economic Review, Vol. 5, No. 5, 2010, pp. 596-619. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0106.2010.00528.x

- A. Young, “Increasing Returns and Economic Progress,” The Economic Journal, Vol. 38, No. 152, 1928, pp. 527‑542. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2224097